Abstract

Background

This study compared haemodynamics of continuous Wiley Spinal® anaesthesia with continuous epidural anaesthesia in elderly patients undergoing transurethral resection of prostate (TURP).

Methods

After Institutional Review Board approval, thirty elderly male patients undergoing TURP classified as ASA physical status II or III were assigned into either the following: Continuous Epidural Anaesthesia group (Group CEA) receiving fentanyl 50 μg with plain bupivacaine 0.5% in 5 ml boluses or Wiley Spinal® Anaesthesia group (Group WSA) receiving fentanyl 5 μg with plain bupivacaine 0.5% given as 0.5 ml boluses until reaching sensory level of T10. Sensory and motor block onset and recovery, haemodynamics, time to first analgesia and adverse events were documented.

Results

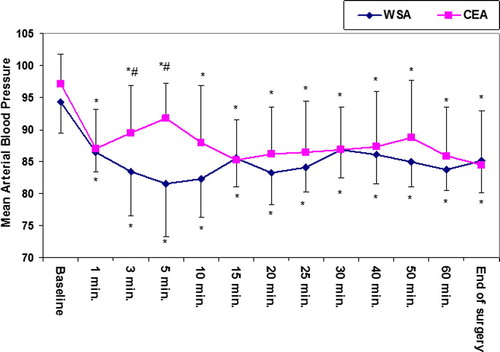

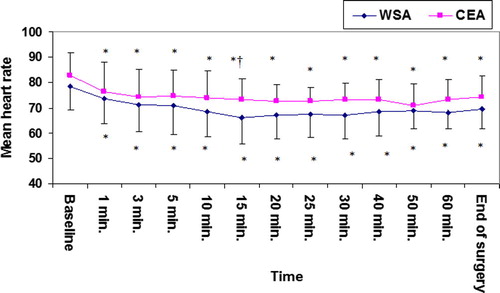

On reviewing WSA and CEA groups, onset of T10 sensory block [2 (1–8) vs. 5 (3–20) min], and motor block [9 (2–25) vs. 12 (5–40) min], with sensory recovery [161.7 ± 28.3 vs. 253.3 ± 52.7 min] and motor block duration [100.0 ± 27.4 vs. 130.7 ± 19.5 min] respectively (P < 0.05) being shorter in Group WSA. Haemodynamics revealed significant reduction in mean arterial pressure after three and five minutes of injection of local anaesthetic and heart rate after fifteen minutes in Group WSA when compared with Group CEA (P < 0.05). Time to first analgesia and adverse events were non-significant.

Conclusion

In elderly patients undergoing TURP, continuous Wiley Spinal® anaesthesia showed nearly comparable haemodynamics as continuous epidural anaesthesia with minimal adverse effects. This technique also provided good anaesthetic profile as well as fast sensory and motor block onset and recovery.

1 Introduction

Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) has always been the treatment of choice for elderly patients with senile prostatic enlargement causing bladder outlet obstruction [Citation1]. Under anaesthesia, the decrease in their cardiovascular reserve predisposes them to severe haemodynamic instability [Citation2]. The mortality rate can reach up to 1% while the perioperative morbidity lies between 18% and 26% [Citation3], 1–8% of which in the form of TURP syndrome [Citation4]. Early diagnosis of complications such as TURP syndrome and bladder perforation is quite difficult under general anaesthesia [Citation1], thus making neuraxial block the technique of choice for such procedure.

Continuous epidural anaesthesia offers flexibility to extend, intensify, and maintain the block as well as ensure postoperative analgesia [Citation5]. The choice of subarachnoid single dose injection provides a potent blockade of fast onset while its extension and duration as well as its haemodynamic impact are difficult to predict [Citation6]. Continuous spinal anaesthesia (CSA) offers the advantage of fractionating the dose of local anaesthetic to reach an adequate level of the block with minimal haemodynamic disturbances [Citation7]. However, CSA is not without disadvantages; a high percentage of postdural puncture headache (PDPH) with a risk of infection, haemorrhage and nerve trauma [Citation8]. The development of small gauge catheters has significantly reduced the incidence of these complications [Citation8,Citation9]. Several cases of cauda equina have been reported with CSA when using 28-gauge (micro) catheters caudally directed and 5% hyperbaric lidocaine as the local anaesthetic of choice [Citation10]. Accordingly, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) banned the utilization of catheters smaller than 24-gauge [Citation11] and recommended that hyperbaric anaesthetic solution to be diluted before injection [Citation12].

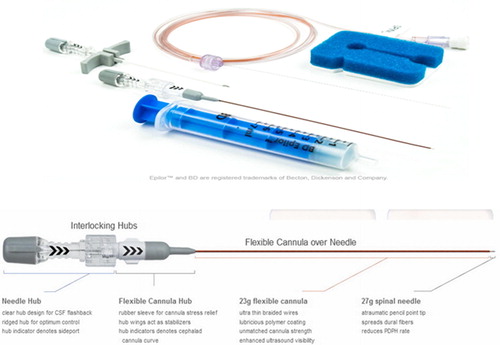

Recently, the Wiley Spinal® catheter (Epimed; Johnstown, NY) has been introduced into clinical practice. It has been innovated as a flexible cannula over needle for intrathecal access where the dural hole is equal to the catheter size in an attempt to reduce the incidence of PDPH () [Citation13].

We hypothesized that the use of Wiley Spinal® catheter would offer haemodynamic stability with few side effects when compared with continuous epidural anaesthesia in patients undergoing TURP. Thus, the objective of this randomized prospective study was to evaluate the efficacy of the continuous spinal anaesthesia using the Wiley Spinal® catheter as compared with the standard continuous epidural anaesthesia in elderly patients undergoing TURP. The primary outcome of this study is the mean arterial blood pressure between both techniques. Secondary outcomes include characteristics of sensory block, motor block, time to first analgesic injection as well as early and late neurological complications.

2 Materials and methods

Ethical Committee approval as well as written informed consents were obtained from all patients. The study was registered in a public trial register (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov) under the identification number: NCT01845389 on 04/26/2013. Thirty elderly male patients (above 60 years) scheduled for TURP under neuraxial block classified as ASA physical status II or III were assigned in this study. Those suffering from neurological diseases, severe cardiopulmonary disorders, coagulopathy, previous back surgery, infection at the injection site, body mass index (BMI) superior to 35 kg/m2, hypersensitivity to amide local anaesthetics and patients’ refusal to participate were excluded.

Randomly, patients were assigned to one of two equal groups of fifteen patients each using a computer-generated random number table: Continuous Epidural Anaesthesia Group (Group CEA) and Wiley Spinal® Anaesthesia Group (Group WSA). In the operating room, standard monitors (five-lead ECG, pulse oximeter and non-invasive blood pressure) were attached to the patient. Preload of 3–4 ml/kg 0.9% NaCl was given slowly over 30 min. Intraoperative fluid administration was kept to minimum and guided by the haemodynamic status of the patient as well as the serum Na level. Supplemental oxygen was given via a nasal cannula at a rate of 3 L/min throughout the procedure.

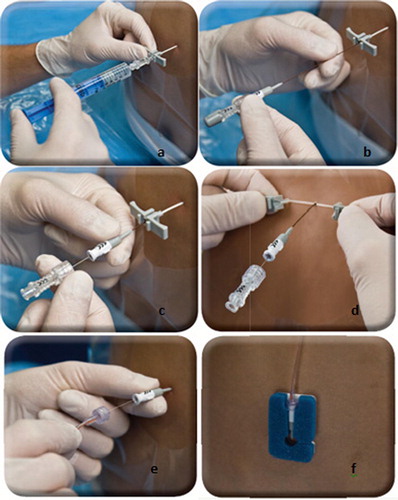

In the sitting position, 3 ml of 2% lignocaine were infiltrated at L3-4 inter-vertebral space. In Group CEA, epidural anaesthesia was administered via a 20-gauge epidural catheter threaded cephalad through an 18 gauge needle identified by the loss of resistance method to air. Boluses of 50 μg of fentanyl with plain bupivacaine 0.5% in 5 ml were given 6 minute-increments injected (as sensory level checked every 2 min) till reaching the target sensory level (T10). In Group WSA, Wiley Spinal kit was used as follows: an18-gauge Tuohy peel-away epidural sheath was introduced into the epidural space by using loss of resistance technique to air (a). Epidural introducer was removed leaving epidural sheath to be a pathway for Wiley Spinal catheter. A flexible, convenience curve 27-gauge atraumatic pencil point tip spinal needle was introduced through the epidural sheath (b). After CSF flow was confirmed, a 23-gauge flexible cannula was threaded over the spinal needle (c). Peel-away epidural sheath was removed and flexible cannula was continually advanced over the spinal needle into the intrathecal space cephalad (d). Wik-Wire™ was then attached to the Wiley cannula using a tightly secure luer-lock connection (e). The proximal cap of this extension set was removed and passive filling with CSF confirmed and the kit is fixed to the patient’s back (f). Boluses of 5 μg of fentanyl with plain bupivacaine 0.5% in 0.5 ml were given 6 minute-increments injected intrathecally till reaching the target sensory level (T10) () [Citation13].

The dead space of tubing and catheter was 1.2 ml and 0.8 ml in CEA and CSA kits respectively. These volumes were taken into consideration when initial bolus of local anaesthetic solution was administered.

For both groups, the end point of injections is reaching a sensory level of T10 identified by a pinprick test. Motor block was determined using Modified Bromage Scale; Grade 0: no weakness, Grade 1: unable to rise extended leg; but move knees and feet, Grade 2: unable to rise extended leg nor to flex knee but able to move feet, and Grade 3: unable to move any joint in legs (complete block) [Citation14].

Motor and sensory blocks were detected for the first 15 min every 2 min and then every 10 min till the end of operation then every 30 min until resolution of the block. After two-segment regression occurs, 5 ml or 0.5 ml of additional isobaric bupivacaine 0.5% was administered in group CEA and group WSA, respectively. Blood pressure, heart rate as well as oxygen saturation were noted before administering anaesthesia, immediately after placing the catheter, every one minute for the first 10 min then every 5 min till end of operation. Any drop of MAP beyond 20% from the baseline was managed with intravenous boluses of 5 mg ephedrine hydrochloride, repeated every 3 min while a heart rate falling below 55 beat/min was corrected using 0.5 mg intravenous atropine.

Characteristics of motor and sensory block, total dose of bupivacaine needed to stabilize the desired block level at T10 and to prolong it as well as the time needed to first analgesic requirement were noted in both groups. Failure of regional anaesthesia (unilateral or patchy block) cases were excluded from the study and substituted by other patients. Failed cases received single dose spinal anaesthesia (SDSA) as a backup plan. Intra- and postoperative side effects such as pruritus, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, itching, visual disturbances, PDPH and symptoms suggestive of neurological damage (back pain, numbness, paraesthesia, and bowel dysfunction) were documented during the first 24 h, at 7 days and with a follow-up call after 1 month interval. The incidence of hypotension, bradycardia or depression of respiration (respiratory rate below 10 breath per minute or oxygen saturation falling below 90%) was documented. Postoperative analgesia was determined on 0–10 visual analogue scale (VAS) (0: no pain at all, 10: maximum imaginable pain) every hour up to 10 h. When VAS score exceeds three, 5 ml or 0.5 ml of plain bupivacaine 0.5% was administered in group CEA and group WSA, respectively. The catheter was then removed after 24 h.

3 Statistical analysis

Sample size was calculated based on a previous study [Citation15], according to the MAP changes after continuous spinal and epidural injection of local anaesthetic as the primary goal is considered (standardized Δ was 1.3 between the two groups). At an α level of 0.05 and power of 90%, 15 patients per group were needed to determine this difference. Results are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD), median (minimum-maximum) or number (%) whenever it is appropriate. In normally distributed data, comparison between different variables in both groups was done using unpaired t test and comparison to baseline within the group was done using repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test with corrected P value = 0.487. If data are not distributed normally, comparison between different variables in both groups was performed using Mann Whitney U test and comparison to baseline within the group was done using Friedman ANOVA followed by Wilcoxon Signed Ranks test as a post hoc test. Categorical data were compared using Chi-square test. If P value was ⩽0.05, the data were considered significant. SPSS computer program, version 16 windows (IBM, USA) was used in statistical analysis.

4 Results

The two groups showed no difference as regards age, weight, height, BMI, ASA class, and the time of the operation (). Compared to CEA, group WSA had significantly faster onset and recovery of motor and sensory block (). Failure rate was 2 cases in each group (1.3%, P = 1.00).

Table 1 Demographic data and operative time.

Table 2 Characteristics of neuraxial Anaesthesia.

Total intraoperative bupivacaine dose was lower significantly in group WSA as compared to group CEA (11.7 ± 2.4 vs. 83.3 ± 29.4 mg; P < 0.001). In group WSA, haemodynamic data showed significant decrease in MAP at 3 and 5 min and heart rate at 15 min after end point of local anaesthetic injection when compared to group CEA (P < 0.05); otherwise, they were comparable intra-operatively. However, all the measurements were within the clinically accepted ranges ( and ). The patients who required postoperative analgesia were comparable in groups WSA and CEA (4 and 6, respectively, P = 0.439) and likewise, the time to first analgesic requirement was 323 ± 138 and 330 ± 80 min respectively, P = 0.610. Also, the frequency of adverse events was comparable ().

Table 3 Postoperative complications.

5 Discussion

This study compared continuous spinal anaesthesia using Wiley Spinal catheter and continuous epidural anaesthesia in elderly patients undergoing TURP. The study revealed that both techniques resulted in an almost similar haemodynamic profile. Wiley Spinal anaesthesia showed a faster onset as well as recovery of both motor and sensory blocks with less anaesthetic dose as compared to continuous epidural anaesthesia.

Reisli et al. [Citation16] compared haemodynamic effects of CSA versus continuous epidural anaesthesia (CEA) with prilocaine in TURP patients. They reported a significant drop in MAP in the epidural group which may be related to the use of different anaesthetic agents. However, their results were similar to ours in the context that CSA showed rapid onset and recovery of motor and sensory block.

An important drive using CSA compared to the routine SDSA is controlling the anaesthetic dose through continuous titration and achieving haemodynamic stability among elderly and high-risk surgical patients [Citation15,Citation17,Citation18]. In old age and high ASA risk class, inappropriate anaesthetic dose, hypovolemia and hypoxia have been shown to be the most common reasons for cardiac arrest [Citation19]. Even low doses may result in higher anaesthetic levels especially in geriatric patients with cardiovascular and respiratory problems [Citation20].

Baydilek et al. [Citation21] compared the efficacy of CSA versus SDSA using levobupivacaine in patients undergoing TURP. CSA provided better haemodynamic stability compared to SDSA. The target anaesthesia level was achieved in CSA group by using lower anaesthetic dose resulting in faster recovery times.

Jayousi [Citation22] compared SDSA versus epidural anaesthesia for TURP patients using isobaric bupivacaine and IV propofol as an adjuvant and reported stable haemodynamic parameters in the SDSA group but with more consumption of propofol in the epidural group.

Even when compared with combined spinal epidural block, CSA provided better cardiovascular stability with a smaller anaesthetic dose [Citation23]. This has been demonstrated by several studies showing greater haemodynamic stability with less respiratory complications with CSA technique [Citation17,Citation24].

A common side effect of CSA is the high occurrence of PDPH [Citation25,Citation26]. Using smaller needles and microcatheters were suggested to reduce this adverse effect [Citation8] as temporary sealing of the dural hole by the microcatheter can reduce the risk of a PDPH especially when the spinal catheter is removed 24 h postoperatively [Citation27]. Radke and Radke [Citation28] showed that the application of the stylet into the spinal needle prior to the drawback of the cerebral spinal fluid out of the space can reduce the rate of PDPH. A retrospective analysis compared CSA with a 28-gauge microcatheter after puncture of the dura with a 22-gauge Quincke or Sprotte needle showed no difference regarding the incidence of PDPH [Citation29].

Therefore, we described our experience using Wiley Spinal® catheter (Epimed; Johnstown, NY) which is designed to create immediate dural seal for minimizing PDPH. In the current series, we recorded no cases of PDPH nor long-term neurological complications over one month after the procedure. In contrast to our results, Tao et al. [Citation30] reported an incidence of 2.6% of PDPH in young parturients who received CSA using Wiley Spinal catheter and were managed successfully with single epidural blood patch.

Month et al. [Citation31] described their experience with this device for both labor analgesia and surgical anaesthesia during Caesarean deliveries. Similar to our results, analgesia was rapid in onset, easy titration without reported cases of PDPH despite the young age group. They attributed some of the failure cases in their study to obesity suggesting the need for a longer cannula with longer accompanying Tuohy needle. However, in our study, we encountered some failures due to technical difficulties from the lack of experience with this new technique. They also reported inability to maintain an adequate level of anaesthesia for Caesarean section delivery suggesting catheter tip malposition in pregnant women. Transient paraesthesia was faced in their study up to 42% of patients but this incidence was lower in our study to reach 13%. This difference is probably related to the different types of patients in the two studies. Recently, Mackenzie et al. [Citation32] reported 2 cases of PDPH as well as 3 cases of paraesthesia in a small series of 5 pregnant females undergoing caesarian section under continuous anaesthesia using the Wiley Spinal kit. Although such incidence is very high, yet the small sample size puts limitations in interpreting such results.

6 Conclusion

Thus, this study concludes that in elderly patients scheduled for TURP, continuous spinal anaesthesia with Wiley Spinal® catheter showed nearly comparable haemodynamics with continuous epidural anaesthesia. It provides a good anaesthetic profile using smaller anaesthetic dose with rapid onset and recovery of motor and sensory blockade. Although side effects were minimal yet the small sample size is not reliable concerning neurological complications. Thus we recommend a multi-center study covering a larger population to rule out these complications when using this new technique.

Conflict of interest

This study has been supported by Epimed through the supply of Wiley Spinal kits without any financial gain.

Notes

Peer review under responsibility of Egyptian Society of Anesthesiologists.

References

- S.OzmenA.KoşarS.SoyupekA.ArmağanM.B.HoşcanC.AydinThe selection of the regional anaesthesia in the transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) operationInt. Urol. Nephrol.352003507512

- J.A.HanleyA.Lippman-HandIf nothing goes wrong, is everything all right? Interpreting zero numeratorsJAMA249198317431745

- V.MalhotraTransurethral resection of the prostateAnesthesiol Clin N Am182000883897

- R.G.HahnFluid absorption in endoscopic surgeryBr. J. Anaesth.962006820

- M.J.CousinsB.T.VeeringEpidural neural blockadeM.J.CousinsP.O.BridenbaughNeural blockade in clinical anaesthesia and management of pain3rd ed.1998Lippincott-RavenPhiladelphia243322

- J.BowringN.FraserS.VauseA.E.HeazellIs regional anaesthesia better than general anaesthesia for caesarean section?J. Obstet. Gynaecol.262006433434

- J.A.De AndrésE.FebréJ.BellverR.BolinchesContinuous spinal anaesthesia versus single dosing. A comparative studyEur J Anaesthesiol121995135140

- R.J.HurleyD.H.LambertContinuous spinal anaesthesia with a microcatheter technique: preliminary experienceAnesth. Analg.70199097102

- B.T.StandlS.EckertA.M.SchulteJ.EschMicrocatheter continuous spinal anaesthesia in the post-operative period: a prospective study of its effectiveness and complicationsEur J Anaesthesiol121995273279

- M.L.RiglerK.DrasnerT.C.KrejcieS.J.YelichF.T.ScholnickJ.DeFontesCauda equina syndrome after continuous spinal anaesthesiaAnesth Analg721991275281

- J.S.BensonU.S. Food and Drug Administration safety alert: cauda equina syndrome associated with use of small-bore catheters in continuous spinal anaesthesiaAANA J601992223233

- H.RenckNeurological complications of central nerve blocks F-D-C Reports—“Pink Sheet”. 5% hyperbaric xylocaine lebeling for spinal anaesthesia should recommend 1-to-1 drug dilution to reduce neurotoxicity riskActa Anaesthesiol Scand391995859868

- The Wiley Spinal® (Epimed; Johnstown, NY) Brochure catheter (flexible cannula over needle). 141 Sal Landrio Dr., Crossroads Business Park Johnstown, NY 12095800.866.3342. <http://www.wileyspinal.com>.

- P.R.BromageA comparison of the hydrochloride and carbon dioxide salts of lidocaine and prilocaine in epidural analgesiaActa Anaesthesiol Scand Suppl1619655569

- W.KlimschaA.ChiariP.KrafftO.PlattnerR.TaslimiN.MayerHaemodynamic and analgesic effects of clonidine added repetitively to continuous epidural and spinal blocksAnesth Analg801995322327

- R.ReisliJ.CelikS.TuncerA.YosunkayaS.OtelciogluAnaesthetic and haemodynamic effects of continuous spinal versus continuous epidural anaesthesia with prilocaineEur J Anaesthesiol2020032630

- J.F.Favarel-GarriguesF.SztarkM.E.PetitjeanM.ThicoïpeP.LassiéP.DabadieHaemodynamic effects of spinal anaesthesia in the elderly: single dose versus titration through a catheterAnesth Analg821996312316

- D.MichaloudisA.PetrouP.BakosA.ChatzimichaliK.KafkalakiA.PapaioannouContinuous spinal anaesthesia/analgesia for the perioperative management of high-risk patientsEur J Anaesthesiol172000239247

- P.BibouletP.AubasJ.DubourdieuJ.RubenovitchX.CapdevilaF.d’AthisFatal and non fatal cardiac arrests related to anaesthesiaCan J Anaesth482001326332

- P.BibouletJ.DeschadtP.AubasA.VacherP.H.ChauvetContinuous spinal anaesthesia: does low-dose plain or hyperbaric bupivacaine allow the performance of hip surgery in the elderly?RegAnesth181993170175

- Y.BaydilekB.S.YurtluV.HanciH.AyoğluR.D.OkyayG.E.KayhanThe comparison of levobupivacaine in continuous or single dose spinal anaesthesia for transurethral resection of prostate surgeryBraz J Anesthesiol6420148997

- N.A.JayousiSpinal versus epidural anaesthesia for transurethral resection of the prostateSaudi Med J21200010711073

- L.E.ImbelloniM.A.GouveiaJ.A.CordeiroContinuous spinal anaesthesia versus combined spinal epidural block for major orthopedic surgery: prospective randomized studySao Paulo Med J1272009711

- M.MöllmannS.CordD.HolstAuf derLandwehr U. Continuous spinal anaesthesia or continuous epidural anaesthesia for post-operative pain control after hip replacement?Eur J Anaesthesiol161999454461

- N.LiuA.MontefioreN.KermarecA.RaussF.BonnetProlonged placement of spinal catheters does not prevent postdural puncture headacheReg Anesth181993110113

- P.J.PeytonComplications of continuous spinal anaesthesiaAnaesth Intensive Care201992417425

- T.StandlS.EckertA.M.SchulteJ.EschMicrocatheter continuous spinal anaesthesia in the post-operative period: a prospective study of its effectiveness and complicationsEur J Anaesthesiol121995273279

- K.RadkeO.C.RadkePost-dural puncture headacheAnaesthesist622013149161

- E.A.LuxA.AlthausIs there a difference in postdural puncture headache after continuous spinal anaesthesia with 28G microcatheters compared with punctures with 22G Quincke or Sprotte spinal needles?Local Reg Anesth720146367

- W.TaoE.N.GrantM.G.CraigD.D.McIntireK.J.LevenoContinuous spinal analgesia for labor and delivery: an observational study with a 23-gauge spinal catheterAnesth Analg121201512901294

- R.C.MonthE.J.BairdV.A.ArkooshA novel device for intrathecal labor analgesia: a case series2011Society for Obstetric Anaesthesia and Perinatology Annual meetingHenderson, NV22

- C.P.McKenzieB.CarvalhoE.T.RileyThe Wiley Spinal catheter-over-needle system for continuous spinal anesthesia: a case series of 5 cesarean deliveries complicated by paresthesias and headachesReg Anesth Pain Med4132016405410