Abstract

Plant hormones play vital roles in the ability of plants to acclimatize to varying environments by mediating growth, development and nutrient allocation. The present investigation was undertaken to have some information about interactive effects of seawater salinity and some plant growth regulators (gibberellic acid, indole acetic acid or abscisic acid) on leaf area, pigment and chloroplast ultrastructure as well as saccharides and protein content of wheat flag leaf. In the majority of cases, seawater at 10 or 25% increased pigment content, particularly carotenoids. On the other hand seawater reduced leaf lamina area, Hill activity and sucrose as well as polysaccharides and protein. The interactive effect of seawater and growth regulators accelerated the production of Chl a, Chl b and carotenoids by increasing the values of these pigment. Furthermore, grain pretreatment with gibberellic acid, indole acetic acid or abscisic acid induced marked increase in leaf lamina area, Hill activity and sucrose as well as polysaccharides and protein. Irrigation of wheat plants by seawater at 10 or 25% caused dramatic changes in chloroplast ultrastructure of flag leaf. These changes include disorganized membrane system, disruption of bounding membrane, reduction in the size and number of starch grains and an increase in plastoglobuli. The presoaking of wheat grains in GA3, IAA or ABA resulted in an increase of plant tolerance against the adverse effect of seawater particularly at 10%. This resistance was estimated by the presence of normal chloroplast.

1 Introduction

Plants' behavioral response to salinity is complex, and different mechanisms are adopted by plants when they encounter salinity. However, plant species have different degrees of sensitivity or tolerance to salinity [Citation1,Citation2]. Irrigation of wheat plants by seawater at 25% caused marked decrease in leaf area, pigment content, Hill activity and photosynthetic efficiency of wheat flag leaf at ear emergence [Citation3].

Flag leaves have, for a long time, been considered as an important source to be supplied to the ears of rice [Citation4] and wheat [Citation2]. Pigment content which could be regarded as a criterion for photosynthetic activities were markedly affected by salt stress in the maize plants [Citation5], in wheat [Citation2], in broad bean [Citation6] and in sorghum [Citation7]. On the other hand, salinity decreased pigment in spinach [Citation8], in black gram [Citation9] and in wheat [Citation10].

Plant hormones play vital roles in the ability of plants to acclimatize to varying environments by mediating growth, development and nutrient allocation. Hormones move through specific pathways to regulatory sites where they respond to stress at low concentration. All biological activities are directly or indirectly affected by phytohormones [Citation11]. Gibberellic acid and indolyl-3-acetic acid increased pigment content of salinized plants (i.e. in grasses [Citation12], in kidney bean [Citation13], in broad bean [Citation6]). Furthermore, the interaction between salinity and phytohormones increased the number of chloroplasts per mesophyll cell of wheat flag leaf [Citation12].

Plant growth regulator, kinetin, is known to modulate the key physiological processes under abiotic stresses in different crops [Citation14]. Phytohormones have been reported to be involved in stress responses and adaptation [Citation15,Citation16], mainly abscisic acid (ABA), ethylene and salicylic acid (SA). However, much less is known about the role of cytokinins, gibberellins and auxins, traditionally not related to stress responses except for some few examples. One of the principal topics studied in plant responses to abiotic stress, especially drought and salinity, is ABA accumulation. The biosynthesis and redistribution of this hormone is one of the fastest plant responses to abiotic stresses, causing stomatal closure to reduce water loss via transpiration and eventually limiting cellular growth [Citation16].

Only few studies have been devoted to the influence of water stress in the plant cell organelles. Ionic additives such as NaCl and KCl caused a significant swelling of thylakoid membranes in chloroplast of Kandelia candel [Citation17]. The most outstanding feature observed were the presence of a distinctive ultrastructure organization.

The most outstanding features observed were the presence of turgid cells with enlarged amyloplasts and mitochondria [Citation18]. In cotton, salinity induces shrinkage, lamellae swelling of chloroplasts and condensed mitochondria, with oxalate crystals occurring in the vacuole [Citation19]. Furthermore, Aldesuquy et al. [Citation2] irrigated wheat plants by seawater at 25% which caused marked decrease in leaf area, pigment content, Hill activity and photosynthetic efficiency of wheat flag leaf at ear emergence. Grain priming with kinetin, spermine or their interaction alleviated the adverse effect of seawater stress by stimulating leaf area expansion, pigment production as well as photosynthetic activity. From transmission electron microscopy micrographs, a continuous “end-to-end” distribution of regular (oval or elliptical) chloroplasts around the cell's periphery was observed in flag leaf mesophyll cells of control wheat plants. Conversely for seawater-stressed plants, the irregular spherical chloroplasts appeared “bulbous” and discrete; the cells also displayed extensive but thin peripheral cytoplasmic regions devoid of chloroplasts. Grain presoaking in 0.1 mM kinetin caused the chloroplast of stressed wheat plants to be more regular, with organized membrane system, large starch grains and projections in the form of tails. Furthermore, ultrastructure analysis cleared that grain priming with spermine, either alone or in combination with kinetin, caused the chloroplast in flag leaf mesophyll cells of stressed wheat plants to be more regular in shape with more starch grains. The changes in pigment content and photosynthetic activity of flag leaf appeared to depend mainly on chloroplast ultrastructure and its numbers, showing a positive correlation between chloroplast number and pigment content.

It is an urgent task of plant biologists to explore suitable mechanisms of developing salt tolerant crop plants that can produce sufficient yield under adverse condition. The present investigation was undertaken to have some information about interactive effects of seawater salinity and some plant growth regulators (gibberellic acid, indole acetic acid or abscisic acid) on the pigment and chloroplast ultrastructure of wheat flag leaf.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant material and growth conditions

For soaking experiment, a homogenous sample of wheat grains (Sakha 69) was selected. The grains were surface sterilized by soaking in 0.01 M HgCI2 solution for 3 minutes and washed thoroughly with distilled water. The sterilized grains were divided into 4 sets. Grains of the 1st set were soaked in distilled water, while the grains of 2nd, 3rd, and 4th sets were soaked in gibberellic acid (GA3) at 50 mg/L, indol-3-yl-acetic acid (IAA) at 5 mg/L and abscisic acid (ABA) at 1 mg/L, respectively for about 12 hours. The selection of the applied doses as well as the time of presoaking was based on preliminary experiments carried out in our laboratory for studying the effect of the provided growth regulators on the growth of different treated wheat plants by seawater [Citation6].

After soaking, all grains were thoroughly washed with distilled water and then sowed (15 grains per pot) in earthenware pots (30 cm in diameter) filled with 5 kg soil (sand, clay 2/1 v/v). The plants were subjected to natural day/night conditions (mean minimum/maximum air temperature and relative humidity were 15/25 °C and 35/45%; respectively) at mid-day during the experimental period. The plants in all sets were irrigated to field capacity by tap water. After two weeks, only five uniform seedlings were left in each pot. The plants of each set were divided into three groups (no irrigation with seawater, 10 % irrigation with seawater and 25% irrigation with seawater). The standard seawater contained [kg m−3]: Cl–, 21.6; Na+, 11.1; SO4−2, 2.85; K+, 0.49; P3–, 16.6; salinity was 38.5 g kg−1; pH = 8.1 and electric conductivity (EC), 47 mmhos cm. After thinning and before heading, the plants received 35 Nm−2 as ammonium nitrate and 35 Pm−2 as super phosphate. At heading stage (84 days from sowing), flag leaf of wheat plants were used for estimation of pigment as well as electron microscopical examination.

Leaf lamina area was calculated according to the equation followed by Quarrie and Jones [Citation20]. Saccharides were determined as method adopted by Riazi et al. [Citation21]. Protein content was estimated according Bradford [Citation22].

2.2 Estimation of pigment and Hill reaction activity

The plant photosynthetic pigment (chlorophyll a, b and carotenoids) were determined according to Metzner et al. [Citation23], while Hill activity assay was carried out as described by Arnon [Citation24].

2.3 Electron microscopy

This method was the same as Baka [Citation25]. At heading stage (84 days from sowing), flag leaf of wheat plants were used in the present study. Normal green leaves of untreated plants were selected, together with those treated with seawater or seawater and growth regulating substances. Tissues from between the veins were cut under a fixative containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer at room temperatures and then washed three times in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer at pH 7.0. The segments were left in the same fixative for 24 hours at room temperature and then washed three times in 0.1 M buffer over one hour. After washing, the segments were post fixed in 1% osmium trioxide in the same buffer, dehydrated in graded series of ethanol and embedded in Araldite. Ultra thin sections were cut using JUN-5 Ultra microtome, stained by 2% aqueous uranyl acetate followed by lead citrate [Citation26]. The ultra thin sections were examined and photographed by JUN-5G electron microscope.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Statistical measurements were performed in triplicates and the means are reported. A test for significant differences (one way ANOVA) between means at p ≤ 0.05 was performed using least significant difference (LSD) test [Citation27].

3 Results

3.1 Changes in leaf area, pigment, Hill activity, saccharides and protein

Seawater at 10 or 25% caused marked increase (p ≤ 0 .01) in leaf area and carotenoids content of wheat flag leaf after complete emergence of spikes. On the other hand, Chl a content appeared to be non-significantly affected by seawater treatments. Seawater at 25% induced marked depletion (p ≤ 0.01) in Chl a content as well as Hill activity wheat flag leaf (). Furthermore, irrigation of wheat plants by seawater caused marked reduction (p ≤ 0 .01) in sucrose, polysaccharides and protein content of wheat plants ( and ).

Table 1 Effect of grain presoaking in GA3, IAA or ABA on leaf area (cm2/leaf), sucrose, polysaccharides and proteins content in flag leaf (g kg−1 DM) of wheat plants irrigated by seawater.

Table 2 Effect of grain presoaking in GA3, IAA or ABA on the pigment content (mg g−1f.wt) and Hill reaction activity [mmol (DCPIP) Kg−1(chl) s−1] in flag leaf of wheat plants irrigated by seawater.

The interaction effect of seawater and GA3, IAA or ABA significantly accelerated the expansion of flag leaf area and formation of Chl a, Chl b and carotenoids (p ≤ 0.01) in flag leaf. Furthermore, these hormones induced additional increases in pigment contents particularly Chl a and Chl b of seawater-treated plants and Hill reaction activity ( and ). Grain pretreatment with gibberellic acid, indole acetic acid or abscisic acid induced marked increase (p ≤ 0.01) in sucrose and polysaccharides as well as protein.

3.2 Changes in chloroplast ultra-structure

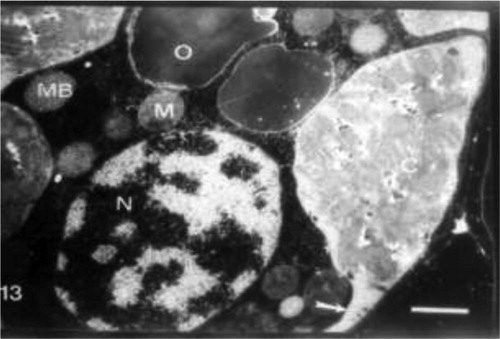

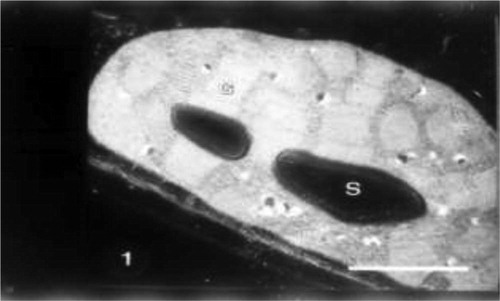

Electron microscopical examination revealed that the chloroplast from mesophyll cells of untreated plant show well developed membrane structure with very dense stacks of grana, intergranal lamellae and chloroplast-bounding membrane with starch grains and few plastoglobuli (Fig. 1).

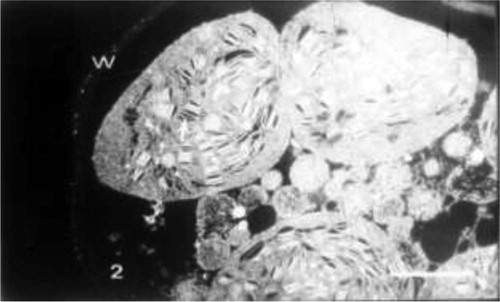

Leaves from plants treated with 10% seawater showed more or less spherical chloroplasts with disorganized membrane system and disruption of bounding membrane (Fig. 2). Also, at this concentration, the cytoplasm was more vacuolated, with the protoplasm including different organelles moved apart from the cell wall and the tonoplast being distorted (Fig. 2).

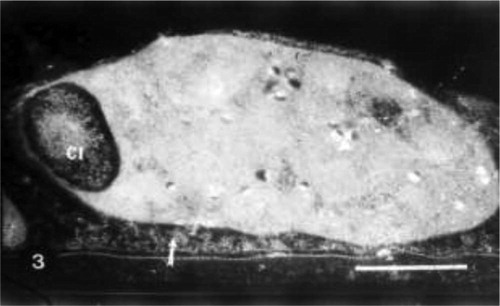

Irrigation of wheat plants with seawater at 25% revealed the appearance of irregularly shaped chloroplasts. An invagination of cytoplasmic inclusions inside chloroplasts was observed. Disorganized membrane system inside the chloroplasts was also noticed (Fig. 3).

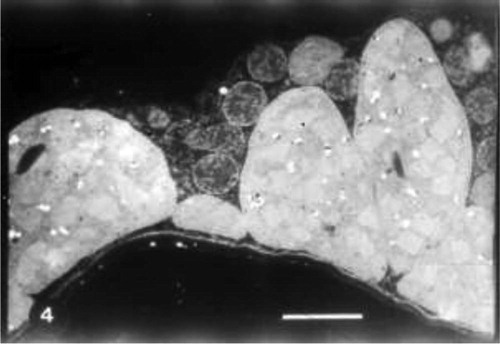

Grain presoaking in GA3 caused an increase in grana of chloroplasts of untreated wheat plants (Fig. 4). An increase in plastoglobuli was also observed. In some cases divided chloroplasts were noticed (Fig. 5). Grain presoaking in GA3 and irrigation of wheat plants with low concentration of seawater (10%) induced the appearance of projections from chloroplasts, the presence of starch grains and the reduction in the number of plastoglobuli. No changes in the lamellar system of chloroplasts were detected (Fig. 6). The interactive effect of high concentration of seawater (25%) and GA3 caused disorganization in lamellar system of chloroplast and the appearance of cytoplasmic inclusions (Fig. 7).

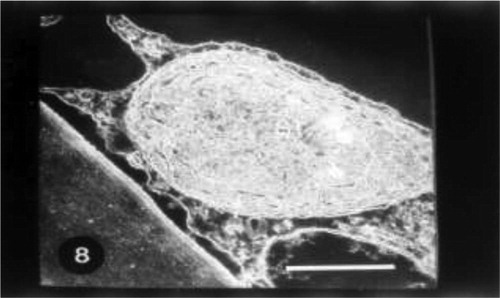

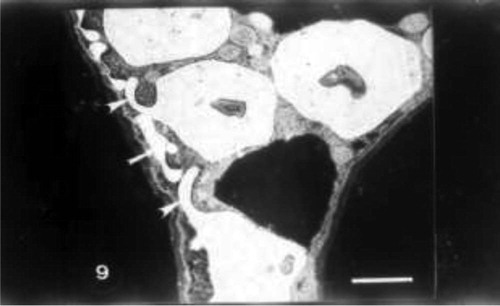

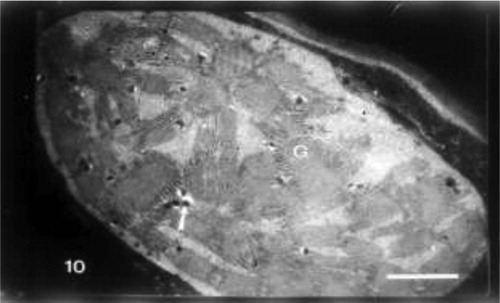

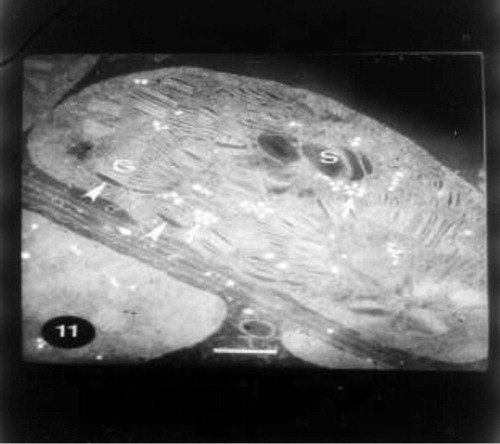

Grain pretreatment with IAA induced normal chloroplast with organized lamellar system in control untreated wheat plants (Fig. 8). The regeneration of chloroplasts was the most remarkable feature at this treatment (Fig. 9). Regenerated chloroplast was characterized by undifferentiated lamellae and large central storm free of lamellae (Fig. 9). Grain priming with IAA and irrigation of wheat plants with seawater (10%) led to an increase of projections of chloroplasts which appeared as tails. In some positions, these tails were completely separated from mature chloroplasts which may be due to the plane of sectioning. In this treatment chloroplast was characterized by spherical shape, the absence of plastoglobuli and the presence of starch grains (Fig. 10). Indole acetic acid pretreatment caused an increase in grana and plastoglobuli and the presence of starch grains in seawater-treated plants particularly with 25% (Fig. 11).

Abscisic acid pretreatment resulted in a plant characterized by a large chloroplast containing large amounts of grana that nearly filled most of the stroma. Starch grains, few plastoglobuli and organized chloroplast envelope were also detected in control plants (Fig. 12). Grain presoaking in ABA and irrigation of wheat plants with 10% seawater led to no remarkable changes in the chloroplasts. The increase in grana number, the presence of starch grains, the occurrence of few plastoglobuli and organized bounding membrane were observed (Fig. 13). The interactive effect of abscisic acid and seawater at 25% revealed the presence of high percentage of plastoglobuli, increased grana number and presence of chloroplast tails (Fig. 13).

4 Discussion

The reduction of cell expansion of flag leaf area due to seawater salinity may result from the decrease in cell wall extensibility [Citation3]. The marked decrease in leaf area in response to seawater irrigation was mitigated when the grains were soaked in GA3, IAA and ABA. Plant growth hormones may be involved directly in leaf expansion and development [Citation28].

The simulative effect of seawater on pigments content of wheat flag leaf particularly the carotenoids might be due the fact that salinity led to an increase in the number of chloroplast mesophyll cells. These results are in accordance with the results of Chavan and Karadge [Citation29] on wheat [Citation12], on Vicia faba [Citation6] and on wheat [Citation30]. The meditative effect of GA3, IAA or ABA on pigment formation as well as Hill activity in flag leaf of wheat plants irrigated by seawater may explain the fact that these hormones may retard the senescence of flag leaf and this advantage will keep it green for a prolonged time. These effects became clear particularly through the effect of these provided hormones on ultrastructure of chloroplast of flag leaf. Furthermore, these hormones may increase plastid biogenesis within flag leaf [Citation3].

The observed decline in sucrose and polysaccharides as well as protein of flag leaf of wheat plants irrigated with seawater may probably be due to their export to developing grains within the emerged spikes. Furthermore, the additional increase in pigment and Hill activity inconsistent with the exogenous application of hormones may be the reason of massive increase in saccharides and protein [Citation3].

Chloroplast showed disorganized lamellar system such as regular stacking of grana and intergranal lamellae. These results are in agreement with those obtained by Gunning and steer [Citation31] who proposed that greater stacking of grana may confer an advantage by providing a suitable environment for energy transfer (photosystem I and photosystem II). Kaplan and Arntzen [Citation32] also suggested that stacking has resulted in improved control of light harvesting and photochemical operations.

The greater stacking grana induced by hormonal treatment particularly GA3 may explain the accumulation of carotenoid in wheat flag leaf of seawater treated plants. These results are in agreement with those obtained by Weir and Benson [Citation33] who suggested that the accumulation of carotenoid as a result of stacking may protect chlorophyll from bleaching by light at high intensities.

Chloroplasts seem to be the organelles more sensitive to stress. Our study revealed that seawater salinity induced disruption of membrane system of chloroplast and high vacuolated cytoplasm. These results fit well the observations of Blumenthal-Goldschmidt and Poljakoff-Mayber [Citation34] who found that salinity caused swelling of chloroplasts and mitochondria and extensive vacuolization with distortion of tonoplast in Atriplex. Furthermore, Gausman et al. [Citation19] reported that salinity induces shrinkage, lamellae swelling and condensed mitochondria in cotton plants. Hawing and Chen [Citation17] added that ionic additives such as NaCI and KCI caused significant swelling of thylakoid membranes in chloroplasts of Kandelia candel. Furthermore, Aldesuquy [Citation30] found that irrigation of wheat plants with 25% seawater induced dramatic changes in chloroplasts and oleosomes particularly after 21 days post-anthesis. They revealed that there were slight differences between two wheat cultivars in response to seawater at 10% and 14 days post-anthesis in terms of chloroplast ultrastructure. The most obvious changes were observed with the treatment with 25% seawater at 21 days post-anthesis. Moreover, disorganized membrane system was identified with swollen thylakoids and many plastoglobuli were recognized in the chloroplasts in comparison to control plants.

The present investigation revealed that seawater at 25% caused a decrease in granal system. This might cause a decrease in photosystem II activity as demonstrated by Groff et al. [Citation35]. The alleviation of adverse effect of seawater (particularly at 10%) by GA3 or IAA induced more improvement to wheat plants by inducing a high rate of assimilate export out of the leaf throughout the increasing number of starch grains in chloroplast of saline-treated plants. These results were in accordance with those obtained by Gunning and Steer [Citation31].

Gibberellic acid caused a division in chloroplast of seawater-treated or untreated wheat plants. This effect might cause plastid biogenesis [Citation12]. The mechanisms by which gibberellic acid (GA) priming could induce salt tolerance in plants are not yet clear [Citation13].

Abscisic acid which accelerates leaf senescence [Citation36] resulted in large chloroplast containing large amount of grana nearly filled most of the stroma. Furthermore, ABA increased the number of grana and plastoglobuli as well as induced organized bounding membrane in seawater-treated plants. In connection with these results Hurng et al. [Citation37] found that abscisic acid resulted in unstacking of thylakoid membranes, increase in the number and size of plastoglobuli, decrease of chloroplast size and rupture of chloroplast envelopes. Further, they added that the shape of chloroplast in the presence of ABA changed from elliptical to spherical. Shah et al. [Citation11] reported that abscisic acid acts as a mediator in plant responses to many stresses, including salt stress.

5 Conclusions

It is not questionable that grain priming in plant hormones may retard the senescence of flag leaf and this advantage will keep it green for a prolonged time. Furthermore, these effects became clear particularly through the effect of these provided hormones on leaf lamina area, pigment, Hill activity, saccharides and protein as well as ultra-structure of chloroplast of flag leaf. Hence, chloroplast showed disorganized lamellar system such as regular stacking of grana and interregnal lamellae. Finally, presoaking of wheat grains in GA3, IAA or ABA resulted in an increase of wheat plants tolerance against the adverse effect of seawater particularly at 10%. This resistance was estimated by dramatic increase in pigment production throughout the presence of normal and healthy chloroplasts.

Acknowledgement

The author sincerely thanks Prof. Zakaia Baka for technical support in preparing electron microscopic samples.

References

- M.JamilK.J.LeeJ.M.KimH.S.KimE.S.RhaSalinity reduced growth PS2photochemistry and chlorophyll content in radishSci. Agric642007111118

- H.S.AldesuquyZ.A.BakaB.M.MickkyRole of kinetin and spermine in the reversal of seawater stress-induced alteration in growth vigor, water relations, membrane characteristics and nucleic acids of wheat plantsPhyton542014251274

- H.S.AldesuquyZ.A.BakaB.M.MickkyKinetin and spermine mediated induction of salt tolerance in wheat plants: leaf area, photosynthesis and chloroplast ultrastructure of flag leaf at ear emergenceEgypt J Basic & Appl Sci20147787

- RaoC.N.K.S.MurtySource and relationship in riceSci Cult421976555559

- B.A.El- DeepThe effect of plant hormones and salinity of some physiological activities of some plants [M.Sc. Thesis]; Assiut, Egypt: Assiut University1984

- H.S.AldesuquyA.M.GaberEffect of growth regulators on Vicia faba plants irrigated by seawater. Leaf area, pigment content and photosynthetic activityBiol Plant351993519527

- S.A.Abo-HamedSalinity–calcium interactions on praline content, chlorophyll, stomata resistance and water content of sorghum plantsJ Environ Sci819944560

- S.P.RobinsonW.JohnS.DowntonJ.A.MillhousePhotosynthesis and ion content of leaves and isolated chloroplast of salt-stressed spinachPlant Physiol731983238242

- M.AshrafThe effect of NaCI on water relations, chlorophyll, protein and proline contents of two cultivars of black gram (Vigna mungo L.)Plant Soil1191989205210

- A.T.MankariosH.S.AldesuquyH.A.AwadEffect of some antitranspirant on growth, metabolism and productivity of saline-treated wheat plants. I. Shoot growth, leaf expansion and photosynthetic pigmentJ Environ Sci1019957587

- F.ShahN.LixiaoC.YutiaoChaoW.X.DongliangS.Shahet alCrop plant hormones and environmental stressSustain Agric Rev152015371400

- H.S.AldesuquyGrowth and pigment content of wheat as influenced by the combined effects of salinity and growth regulatorsBiol Plant341992275283

- M.A.ShaddadM.M.HeikalInteractive effect of GA3 and salinity on kidney beanBull Fac Sci Assiut UnivII19836581

- M.LalarukhA.ArslanM.AzeemM.HussainM.AkbarA.Yasinet alGrowth stage-based response of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) to kinetin under water-deficit environment: pigments and gas exchange attributesActa Agric Scand B Soil Plant Sci642014501510

- J.ShaterianaD.WatereraH.D.JongK.K.TaninoaDifferential stress responses to NaCl salt application in early- and late-maturing diploid potato (Solanum sp.) clonesEnviron Exp Bot542005202212

- Z.PelegE.BlumwaldHormone balance and abiotic stress tolerance in crop plantsCurr Opin Plant Biol142011290295

- Y.H.HwangChenS.C.Effect of toxicity and additives to the fixative on ultrastructure of mesophyllous cells in Kandelia candel (L.) druce (Rhizophoraceae)Bot Bull Acad Sinica3819972128

- G.E.MunozP.W.BarlowB.PlalmaEffect of seawater on roots of Prosopis alba (Leguminosae) seedlingsPhyton (Buenos Aires)5919965563

- H.W.GausmanP.S.BaurM.P.PorterfC.CardenasEffects of salt treatment of cotton plants (Gossypium hirsutum L.) on leaf mesophyll cell microstructureAgron J641992133136

- S.A.QuarrieH.G.JonesGenotype variation in leaf water potential, stomatal conductance and abscisic acid concentration in spring wheat subjected to artificial drought stressAnn Bot441979323332

- A.RiaziK.MatsudaA.ArslanWater stress induced changes in concentrations of proline and other solutes in growing regions of young barley leavesJ Exp Bot36198517161725

- M.M.BradfordA rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein dye-bindingAnal Biochem721976248251

- H.MetznerH.RauH.SengerUntersuchungen zur Synchronisierbarkeit Einzelner Pigment- Mangel- Mutanten von ChlorellaPlanta651965186194

- D.I.ArnonCopper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts: polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgarisPlant Physiol241949115

- Z.A.M.BakaResponses of plant tissues to infection by rust fungi: fine structure, cytochemistry and autoradiography [Ph.D. Thesis]; England: University of Sheffield1987

- E.S.ReynodllsThe use of lead citrate at a high pH as an electron-opaque stain in electron microscopyJ Cell Biol171963208212

- G.W.SnedecorW.G.CochranStatistical method6th ed1976Oxford and IBH Publishing Co.New Delhi

- H.HerzogRelation of source and sink during grain filling period in wheat and some aspects of its regulationPhysiol Plant561982155160

- P.ChavanB.A.KaradgeInfluence of salinity on mineral nutrition of peanut (Arachis hypogea)Plant Soil541980512

- H.S.AldesuquyImpact of seawater salinity on ultrastructure of chloroplasts and oleosomes in relation to fat metabolism in flag leaf of two wheat cultivars during grain-fillingPlant Growth Regul2015 in press

- B.E.S.GunningM.W.SteerUltrastructure and the biology of plant cells1975Edward ArnoldLondon

- S.KaplanC.J.ArntzenPhotosynthetic membrane structure and functionGovinjeePhotosynthesisEnergy conversion by plant bacteriavol. l1982Academic PressNew York65151

- T.E.WeierA.A.BensonThe molecular organization of chloroplast membranesAm J Bot541967389402

- S.Blumental-GoldschmidtA.Poljakoff-MayberEffect of substrate salinity on growth and on submicroscopic structure of leaf cells of Atriplex helium's LAust J Bot161968469478

- C.P.L.GrofM.JohnstonF.BrownellEffects of sodium nutrition on the ultrastructure of chloroplasts of C4 plantsPlant Physiol891989539543

- Z.A.M.BakaH.S.AldesuquyChanges in ultra structure and hormones of the fully senescent leaf of Senecio aegyptiusBeitr Biol Pflanzen661991271281

- W.P.HurngLinT.L.RenS.S.ChenJ.C.ChenY.R.C.H.KaoSenescence of rice leaves. XIX. Ultra structure changes of chloroplastsBot Bull Acad Sinica2919887579