Abstract

The aqueous extract of Avicenna marina (AM) has been suggested to be useful in the treatment of various diseases. In this study, the protective effect of oral administration of Avicenna marina extract against oxidative gastric mucosal injury induced by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), indomethacin in rats was investigated. The aqueous extract of Avicenna marina was given by oral gavages (125 mg /kg) three times at 12 h intervals before administering indomethacin (20 mg/kg). The level of prostaglandin (PGE2) and pH gradient were markedly decreased following indomethacin treatment, with increase in acid volume. In addition, tumor necrosis factor (TNFα), transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and the lipid peroxidation products malondialdehyde (MDA) were significantly increased 6 h after oral administration of indomethacin in rats gastric mucosa indicating acute inflammatory injury. Pretreatment with AM abolished indomethacin induced elevation of TNF-α, TGF-β1 and MAD levels. In indomethacin-treated rats, the superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) activities as well as reduced glutathione (GSH) content were significantly diminished in gastric mucosa. However, pre-administration with AM maintains the level of these parameters near to the control value. Thus, these results indicate the effective anti-peroxidative and preventive actions of AM against indomethacin-induced gastric mucosal damage.

Abbreviations:

- AM

- Avicenna marina

- PMN

- Polymorphonuclear granules

- CAT

- Catalase

- PGE2

- Prostaglandin

- GSH

- Reduced glutathione

- ROS

- Reactive oxygen species

- Indometh

- Indomethacin

- SOD

- Superoxide dismutase

- LPO

- Lipid peroxidation

- TGF-β1

- Transforming growth factor β1

- MDA

- Malondialdehyde

- TNF-α

- Tumor necrosis factor α

- NSAIDs

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

1 Introduction

Harmful effects of toxic factors such as alcohol, bile salts, and hydrochloric acids are prevented by biological structures within the stomach. This high resistance to injuries relies on a number of physiological responses evoked by the mucosal lining against potentially harmful luminal agents, as well as the ability of rapidly repairing the mucosal damage after it occurs [Citation1]. On the other hand, these protective mechanisms might be overcome by injurious factors and a gastric mucosal lesion may develop. Most of the deleterious effects on gastric mucosa are caused by nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which are considered one of the largely used pharmaceutical agents worldwide [Citation2]. NSAIDs produce both helpful and antagonistic impacts fundamentally by hindering cyclooxygenase (COX) and subsequently diminishing the production of thromboxanes and prostaglandins, which are the mediators that signal inflammation and pain as well as mediating the physiological functions [Citation3].

Indomethacin, which is a part of the NSAIDs family, activates polymorphonuclear granules and induce gastrointestinal damage in both animals and humans [Citation4,Citation5]. These kinds of pathologies are usually primarily due to damage of the mucosal cell membranes. Previously, reports have shown that the inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis is not the only mechanism responsible for gastric damage induced by indomethacin [Citation6]. Also, indomethacin might act like a pro-oxidant catalytic and also initiate LPO by producing ROS, thereby interfering with the endogenous antioxidant systems of any mucosal cells [Citation7].

Avicenna marina is a mangrove plant known as gray mangrove tree belonging to the family of Avicenniaceae [Citation8,Citation9]. Phytochemical screening of Avicenna marina aqueous leaf extract revealed the presence of alkaloids, flavonoids, carbohydrates, glycosides, tannins, triterpenoids, and steroids [Citation10,Citation11]. It has been found to possess major therapeutic activity such as antibacterial, anti-helminthic [Citation12], antimicrobial [Citation13], antiviral [Citation14], antihuman immunodeficiency virus, anti-inflammatory, and antitumor activity [Citation15]. Mangrove extracts can be a possible source of mosquito larvicides. Mangrove plants are also reported for their antioxidant, anti-dyslipidemia, antidiarrheal, anti-filarial, anti-ulcer effect, cardiotonic properties, and antidiabetic effects [Citation16]. Mangrove leaf extracts are nontoxic to humans and are environmentally friendly as they are less pollutant [Citation17]. This study focused on the antiulcer activity of Avicenna marina aqueous leaf extract against indomethacin induced gastric ulceration. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first studies that reported the antiulcer effect of AM leaves extract.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Experimental animals

Healthy male Albino Wister rats of about 175 ± 5 g were used throughout the study. The animals were acclimated to laboratory conditions of 20–22 °C with a 12-h light/dark cycle for two weeks before experimentation. All rats were fed with a standard pellet diet and water ad libitum. Care and use of animals were conducted under supervision of the animal Care Committee of Mansoura University, Egypt.

2.2 Cold percolation extraction method

Avicenna marina leaves were collected from (Makadi village, Hurghada region, Egypt) in August 2014. After drying the leaves, they were pulverized into fine powder using sterilized mortar and pestle. 200 g of crushed material was taken into 500 ml of ethanol, kept on a rotary shaker at 120 rpm for 24 h. After shaking, it was filtered through layers of muslin cloth, centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 20 min (Sigma, Laborzentifugen 2K15). Resultant extracts were evaporated and concentrated to dryness using the rotary evaporator at 45 °C. The powder was dissolved in sterilized water and stored at 4 °C [Citation18].

2.3 Experimental design

The animals were deprived of food for 36 hours before the experiment but had free access to water. Then NSAIDs, indomethacin was used as the ulcerogenic agent by a single dose of 20 mg/kg of body weight [Citation19]. Rats were divided into 4 groups, each of 8 animals. The first group did not receive any treatment and served as a control. The second group, animals were orally administered with aqueous extract of Avicenna marina with a dose of 125 mg/kg body weight thrice in 12 hours interval [Citation20].The third group, animals received a single dose of indomethacin orally as 20 mg/kg of body weight. The fourth group, animals were orally administered with aqueous extract of Avicenna marina with a dose 125 mg/kg body weight thrice in 12 hours intervals; after one hour of last administration of AM, animals received a single dose of indomethacin orally as 20 mg/kg of body weight. After 6 hours of NSAID administration, the animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. The animals were dissected and the stomach was taken out, the stomach was opened along the greater curvature and washed by saline solution. Then, the stomachs were photographed and the mucosa was exposed for evaluation.

2.4 Biochemical analysis

Biochemical parameters, including malondialdehyde (MDA), reduced glutathione (GSH), superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT), were assayed using biodiagnostic kits, Dokki, Giza, Egypt. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) level was estimated using an ELISA Kit (Diagnostic Products Corp., Los Angeles, CA, USA). Transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) level was estimated by flow cytometric analysis. The prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) level was quantified with an immune-enzymatic dosage kit from R&D Systems (USA).

2.5 Animal handling

The stomachs were removed and the gastric contents were collected and drained into a graduated centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 2000 x g for 15 min using Centurion Scientific Ltd centrifuge. The supernatant volume and pH were recorded with digital pH meter (intelligent meter YK-2001 pH).

2.6 Histopathological study

For histopathological examination, part of the gastric tissue was removed and was fixed in 10% formalin. After complete fixation, thin sections were prepared from tissues. Xylol and Hematoxylin-Eosin was used for clearing and staining, respectively. The slides were examined by microscope.

2.7 Statistical analysis

All results obtained from the study were evaluated by one-way ANOVA test, and post-comparison was carried out with Tukey-test. The values were expressed as means ± SE and values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant [Citation21].

3 Results

3.1 Morphological investigation

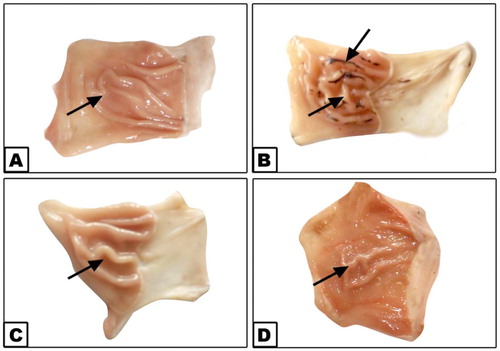

Fig. 1(A–D) showed the antiulcer activity of AM. (A) Stomachs of controlled rats showing normal mucosa. (B) Stomachs of rats showing mucosa with hemorrhagic erosion when treated with indomethacin (20 mg/kg). (C) Stomachs of rats that received AM (125 mg/kg) showing normal mucosa. (D) AM and indomethacin treated group showing nearly normal mucosa.

3.2 Biochemical investigation

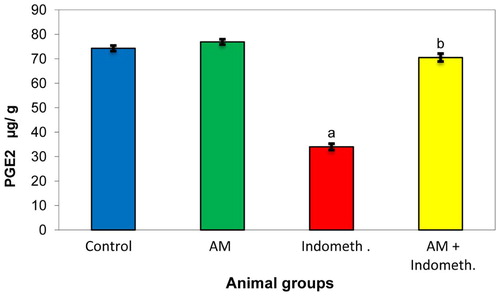

In this study, the oral administration of AM alone did not induce any obvious changes in the most biochemical parameters compared with the control group. Conversely, significant increases were demonstrated in the GSH level and CAT activity in the gastric mucosa. However, the result showed a significant decrease in prostaglandin (PGE2) level and pH gradient accompanied with increase in acid volume in gastric mucosa in indomethacin treated rats. Meanwhile, pretreatment with AM recorded a suppression in these values as shown in Fig. 2 and .

Table 1 Effect of Avicenna marina extract (125 mg/kg) on the values of PH and acid volume in the stomach in different animal groups.

Administration of indomethacin produced a significant increase in MAD content, an index of lipid peroxidation, in gastric mucosa. This was accompanied by marked inhibition of SOD and CAT activities in gastric mucosa in indomethacin treated rats. Oral administration of indomethacin also led to a significant decrease in GSH content (). The pretreatment by AM prevented the increase of MDA levels and the decrease in cellular antioxidants indicated by the activities of SOD and CAT and GSH concentration in the gastric tissue ().

Table 2 Effect of Avicenna marina extract (125 mg/kg) on the levels of lipid peroxidation product MDA (nmol/mg wet tissue), superoxide dismutase (SOD, u/g wet tissue), catalase (CAT, u/g wet tissue), and glutathione (GSH, mg/g wet tissue) in the stomach of different animal groups.

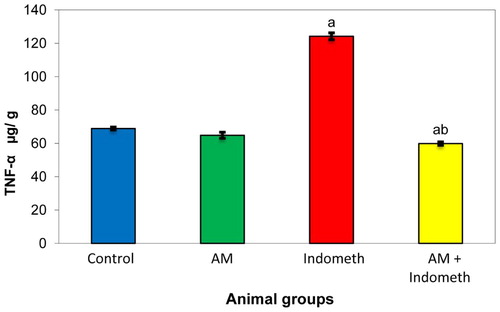

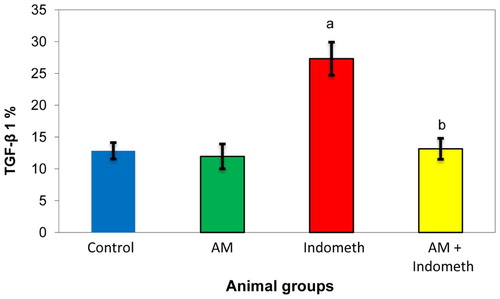

As shown in Figs. 3 and 4, the indomethacin treated rats had significantly higher levels of TNF-α and TGF-β1 compared to the controlled value. The oral pretreatment with plant extract of Avicenna marina normalized the increase in the levels of these markers.

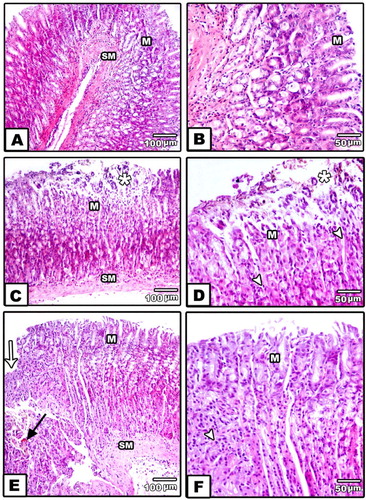

3.3 Histopathological investigation

Fig 5. (A–F) Photomicrograph of stomach of rats H.E. staining.

(A,B) Control group stomach showing normal gastric mucosa and sub-mucosa. Also normal acid producing cells were seen (HE, A, 100x and B, 400x).

(C–F) Indomethacin treated stomachs showing necrosis of superficial layer of gastric mucosa (Star) (HE, C,D 100x).

Stomach showing necrosis and desquamation of superficial layer of gastric mucosa (HE, E,F, 400x).

M, mucosa; SM, submucosa; MP, Muscularis propria; white arrow showing base of ulcer, black arrow showing fibrosis, arrow head showing leukocyte infiltration.

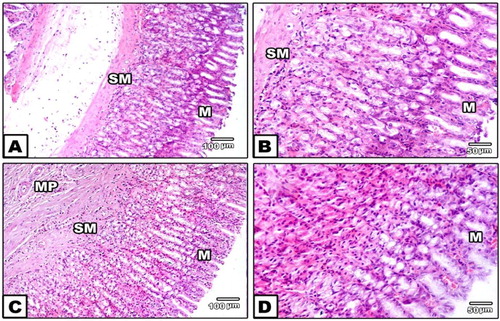

Fig 6. (A–D) Stomach of AM group showing normal gastric mucosa and submucosa (HE, A, 100x and B, 400x).

(C,D) Stomach of AM and indomethacin group, no ulcers were seen. Normal lining epithelium of gastric mucosa with mild congestion (HE, C, 100x and D, 400x).

4 Discussion

NSAIDs are believed to be the most common causative factor in gastric mucosal injury [Citation22]. On the other hand, the gastric mucosal defense mechanisms include several protective factors which allow the mucosa to resist frequent exposure to damaging factors [Citation1,Citation23]. One of the most important gastric mucosal defense mechanisms is prostaglandin. The gastric mucosa represents a source of continuous prostaglandin production, such as PGE2 and PGI2, which are regarded as crucial factors for the maintenance of mucosal integrity and protection against injurious factors [Citation24]. Prostaglandins can stimulate almost all of the mucosal defense mechanisms such as stimulating mucous and bicarbonate production, increasing mucosal blood flow, accelerating epithelial restitution and also mucosal healing in addition to reducing acid output [Citation25]. Also, prostaglandins are known to inhibit mast cells activation as well as leukocytes and platelets adhesion to the vascular endothelium [Citation26].

In the present study, the results recorded a significant decrease in the level of PGE2 [Fig. 2] and pH gradient with increment in acid volume in indomethacin treated rats compared to the corresponding controls []. These findings may be due to indomethacin which produces anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting cyclooxygenase enzymes which by turn suppresses the formation of prostaglandins and thromboxane from arachidonic acid [Citation27,Citation28]. Moreover, prostaglandins reduce the activation of neutrophils and the local release of reactive oxygen species (ROS). In addition, the endothelium of mucosal microcirculation produces prostacyclin which will be highly relevant in ensuring the tonic inhibition of neutrophil adhesion [Citation29,Citation30]. Therefore, indomethacin can shift the mucosal balance toward the recruitment and endothelial adhesion of circulating neutrophils by the inhibition of prostaglandin biosynthesis [Citation28,Citation31]. Neutrophils also clog the microvasculature causing a local drop in mucosal blood flow and a marked release of tissue damaging factors, like proteolytic enzymes and leukotrienes, which increase the vascular tone, exacerbate tissue ischemia, stimulate ROS production, and eventually promote the destruction of the intestinal matrix, leading to a severe degree of tissue necrosis, particularly in the presence of a low luminal pH [Citation32,Citation33]. Just as anticipated above, cyclooxygenase-dependent inhibition connected with bicarbonate secretion contributes also to the gastric mucosal injury elicited from NSAIDs [Citation34].

The obtained gastric mucosal injury in indomethacin treated rats as shown in Fig. 1, may be due to the role of oxygen radicals, LPO and lowered antioxidants levels, this goes in accordance with Naito et al. [Citation35], who suggested that LPO mediated by oxygen radicals plays an important role in the mechanism of ulcer aggravation induced by indomethacin. The lipid peroxidation product, MDA, is more cytotoxic to cells and affects the membrane structure and function [Citation36]. In the present study, indomethacin produced a significant rise in MDA concentration, accompanied by severe ulceration. In concomitant with increased LPO products, there was an inhibition in SOD and CAT activities as well as GSH content in indomethacin treated rats compared to the corresponding controls (). The decline in SOD, CAT activities and GSH level in the gastric mucosa of rats treated with indomethacin may lead to an increase in LPO and hence may render the gastric mucosa more susceptible to injury by indomethacin. Thus, the inhibition of antioxidants leads to the accumulation of ROS [Citation19,Citation37]. This study proved that the level of GSH and CAT activity significantly increased in the AM treated group, and this may be due to its initiating effect on GSH and CAT synthesis.

Moreover, our results recorded a significant increase in tumor necrosis factor, alpha (TNF-α) in indomethacin treated rats as shown in Fig. 3. This result is in agreement with Whittle (2002) [Citation28], who recorded that, oxidative damage associated with indomethacin treatment caused dramatic enhancement in gastric epithelial cell apoptosis triggered by increased expression of TNF-α. Also, the increase in mucosal blood flow is mediated by NO release, and there is experimental evidence demonstrating that NO protects the gastric mucosa against injury induced by indomethacin [Citation38].

Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) is usually a multifunctional cytokine. It regulates cell growth, differentiation, and extracellular matrix production [Citation39]. Also, TGF-β1 is considered as a good inflammatory marker of the cells [Citation40]. In the present study, TGF-β1 was significantly elevated in indomethacin treated rats when compared with the corresponding controls (Fig. 4). These results are usually attributed to the gastric injury relevant to indomethacin administration. Moreover, the integrity of gastric epithelium is actually maintained via a continuous process of cell renewal ensured by mucosal progenitor cells [Citation41]. These cells are submitted to a continuous, well harmonized, and controlled growth, which ensures the replacement of damaged or aged cells on the epithelial surface. The cell turnover process is controlled by growth factors [Citation42]. In particular, a marked expression of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGF-R) has been detected in gastric progenitor cells. This receptor is activated via mitogenic growth factors, such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β1) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) [Citation43]. Also, PGE2 and gastrin are able to transactivate the EGF-R as well as promote the activation connected with mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, with consistent stimulation associated with cell proliferation [Citation44].

Unrefined extracts from some therapeutic tannin-rich plants are generally utilized worldwide to treat gastric ulcer [Citation45]. Tannins are known to exist in mangrove species, which comprises fundamentally of dense tannins or proanthocyanidins [Citation46].

Pretreatment with the AM reflected a tendency to increase PGE2 production in spite of indomethacin-induced depletion. These results may be attributed to the polyphenolic compounds found in AM [Citation47]. Phenols stimulate PGE formation based on their action as co-substrates for the peroxidase reaction [Citation48]. Hence, the leaf extract of AM has the protective effect on the stomach against NSAIDs induced gastric ulcer, and this may be attributed to polyphenolic compounds [Citation49].

In the present study, the gastroprotective properties of AM leaf extract may be attributed to the presence of several compounds. As, in a previous study of the author [Citation10], the phytochemical screening of AM leaves extract revealed that the presence of phenolic-flavonoids; alkaloids; terpenoides; steroides; cardiac glycosides; tannins; flavonoids and saponines. The major active components of the AM are polyphenols, represented majorly by polymeric tannins (80%), hydrolysable tannins (20%) and catechin, chlorogenic, gallic and elagic acids as well as gallotannins, elagitannins, and condensed tannins. These substances which are portrayed by their polyphenolic nature have indicated cytoprotective properties [Citation48] and have been related to antiulcerogenic action in different plants [Citation49,Citation50]. On the other hand, tannins may counteract ulcer advancement because of their protein precipitating and vasoconstricting effects [Citation49]. Their astringent action can help precipitating microproteins on the ulcer site, thereby forming an impervious layer over the lining, which hinders gut secretions and protects the underlying mucosa from toxins and other irritants [Citation51,Citation52].

The results on histopathological investigation of the gastric mucosa of rats indicated that the pretreatment with AM absolutely inhibited the indomethacin-induced congestion, hemorrhage, inflammations, erosions, and ulceration.

In conclusion, it appears that AM has an antiulcerogenic effect that will protect the gastric mucosa from damage induced by indomethacin. This protective action may be due to the inhibition of basal gastric acid secretion and stimulation of mucus secretion. Also, the antiulcer effect of AM may be attributed to the presence of flavonoids in the aqueous extract, although the involvement of other chemical compounds in the plant cannot be ruled out. The data obtained so far do not indicate, however, which specific mechanism(s) is (are) responsible for the anti-secretory, antiulcer, and cytoprotective activities. Further studies are required to isolate the antiulcer compounds and to elucidate their mechanism of action.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express her gratitude to Prof. Dr. Amoura Abo El Naga, Professor of Embryology–Zoology Department, Faculty of Science, Mansoura University, for her advice and assistance with the histopathological examination of the sections.

References

- L.LaineK.TakeuchiA.TarnawskiGastric mucosal defense and cytoprotection: bench to bedsideGastroenterology135120084160

- A.H.RingimReview evidence-based insights on non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugsJ Pharm Cosmet Sci322015813

- J.C.LeslieUse of NSAIDs in treating patients with arthritisArthritis Res Ther1532013

- Y.NaitoT.YoshikawaN.YoshidaM.KondoRole of oxygen radical and lipid peroxidation in indomethacin-induced gastric mucosal injuryDig Dis Sci43199830S34S

- V.SagarR.N.AhamedGastric mucosal cellular changes induced by indomethacin (NSAID) in male albino ratsIndian J Exp Biol371999365369

- T.YoshikawaY.NaitoA.KishiT.TomiiT.KanekoS.Iinumaet alRole of active oxygen, lipid peroxidation, and antioxidants in the pathogenesis of gastric mucosal injury induced by indomethacin in ratsGut341993732737

- Y.NaitoT.YoshikawaK.MatsuyamaN.YagiM.AraiY.Nakamuraet alNeutrophils, lipid peroxidation, and nitric oxide in gastric reperfusion injury in ratsFree Radic Biol Med241998494502

- P.RevathiT.J.SenthinathP.ThirumalaikolundusubramanianN.PrabhuMedicinal properties of mangrove plants – an overviewInt J Bio212201315971600

- ZhuF.ChenX.YuanY.HuangM.SunH.XiangW.The chemical investigations of the mangrove plant Avicennia marina and its endophytesOpen Nat Prod J220092432

- F.I.MouafiM.Abdel-AzizSA.A.BashirA.A.FyiadPhytochemical analysis and antimicrobial activity of mangrove leaves (Avicenna marina and Rhizophorastylosa) against some pathogensWorld Appl Sci J2942014547554

- S.A.MaheraS.M.SaifullahV.U.AhmadF.V.MohammadK.AmbreenSteroids and triterpenoids from grey mangrove Avicennia marinaPak J Bot432201114172011

- S.RavikumarM.GnanadesiganP.SuganthiA.RamalakshmiAntibacterial potential of chosen mangrove plants against isolated urinary tract-infectious bacterial pathogensInt J Med Sci220109499

- S.GurudeebanK.SatyavaniT.RamanathanT.BalasubramanianAntidiabetic effect of a black mangrove species Aegiceras corniculatumin alloxan induced diabetic ratJ Adv Pharm Technol Res320125256

- K.ZandiM.T.AherzadehR.YaghoubiS.TajbakhshZ.RastianM.Fouladvandet alAntiviral activity of Avicennia marina against herpes simplex virus type 1 and vaccine strain of poliovirusJ Med Plants Res32009771775

- K.T.Mani Senthil KumarB.GorainD.K.RoyZothanpuiaS.K.SamantaM.Palet alAnti-inflammatory activity of Acanthus ilicifoliusJ Ethnopharmacol1202008712

- K.T.Senthil KumarZ.PuiaS.K.SamantaR.BarikA.DuttaB.Gorainet alThe gastroprotective role of Acanthus ilicifolius – a study to unravel the underlying mechanism of anti-ulcer activitySci Pharm802012701717

- E.OpraR.WokochaEfficacy of some plant extracts on the in vitro and in vivo control of Xanthomonas campestris Pv. VesicatoriaAgric J32008163170

- J.ParekhS.ChandaIn vitro antimicrobial activity of Trapanatans L. fruit rind extracted in different solventsAfr J Biotechnol62007766770

- A.I.OthmanM.A.El-MissiryM.A.AmerThe protective action of melatonin on indomethacin-induced gastric and testicular oxidative stress in ratsRedox Rep63200115

- P.ThirunavukkarasuL.RamkumarT.RamanathanAnti-ulcer activity of Excoecaria agellocha bark on NSAID-induced gastric ulcer in albino ratsGlob J Pharmacol332009123126

- G.W.SnedecorW.G.CochranStatistical methods7th ed1989The State University Press AmericanIowa

- J.WallaceRecent advances in gastric ulcer therapeuticsCurr Opin Pharmacol562005573577

- B.KayP.PaolaNew Insights into the use of currently available non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugsJ Pain Res82015105118

- F.HalterA.S.TarnawskiA.SchmassmannB.M.PeskarCyclooxygenase-2 implications on maintenance of gastric mucosal integrity and ulcer healing: controversial issues and perspectivesGut4932001443453

- T.BrzozowskiP.C.KonturekS.J.KonturekI.BrzozowskaT.PawlikRole of prostaglandins in gastroprotection and gastric adaptationJ Physiol Pharmacol565020053355

- J.WallaceCOX-2: a pivotal enzyme in mucosal protection and resolution of inflammationSci World J62006577588

- J.S.VijayaK.M.SasiEvidence based update on NSAIDs: overviewInt J Pharm Rev Res442015235242

- B.J.WhittleGastrointestinal effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugsFundam Clin Pharmacol1732002301313

- C.ScarpignatoR.H.HuntNonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug-related injury to the gastrointestinal tract: clinical picture, pathogenesis, and preventionGastroenterol Clin North Am3932010433464

- P.OlsenK.PoulsonA.TherkelsenE.NexoEffect of sialoadenectomy and synthetic human urogastrone on healing chronic gastric ulcer in ratsGut27198614431449

- F.M.De-FariaA.C.A.AlmeidaA.L.FerreiraR.J.DunderC.TakayamaM.S.da Silvaet alMechanism of action underlying the gastric antiulcer activity of the Rhizophora mangle LJ Ethnopharmacol1392012234243

- A.AllenG.FlemströmGastroduodenal mucus bicarbonate barrier: protection against acid and pepsinAm J Physiol Cell Physiol28812005C119

- M.D.JimènezM.J.MartínC.Alarcón de la LastraL.BruseghiniA.EsterasJ.M.Herreríaset alRole of L-arginine in ibuprofen-induced oxidative stress and neutrophil infiltration in gastric mucosaFree Radic Res3892004903911

- C.MusumbaD.M.PritchardM.PirmohamedReview article: cellular and molecular mechanisms of NSAID-induced peptic ulcerAliment Pharmacol Ther3062009517531

- Y.NaitoT.YoshikawaK.MatsuyamaS.NishimuraN.YagiM.KondoEffects of free radical scavengers on indomethacin-induced aggravation of gastric ulcer in ratsDig Dis Sci40199520192021

- K.TakeuchiK.UeshimaY.HironakaY.FujiokaJ.MatsumotoS.OkabeOxygen free radicals and lipid peroxidation in the pathogenesis of gastric mucosal lesions induced by indomethacin in rats. Relation to gastric hypermotilityDigestion491991175184

- M.ItoY.SuzukiM.IshiharaY.SuzukiAnti-ulcer effects of antioxidants: effect of probucolEur J Pharmacol3541998

- S.FiorucciE.DistruttiG.CirinoJ.L.WallaceThe emerging roles of hydrogen sulfide in the gastrointestinal tract and liverGastroenterology13112006259271

- L.A.EissaS.A.HabibM.M.Abdel LatifInhibitory effect of the partially purified protein from Raphnussativus roots and low-molecular-weight heparin on Ehrlich ascites carcinoma bearing miceEJBAS1220148896

- C.LindholmM.Quiding-JärbrinkH.LönrothA.HamletA.SvennerholmLocal cytokine response in Helicobacter pylori-infected subjectsInfect Immun66199859645971

- S.ChiouT.TanigawaT.AkahoshiB.AbdelkarimM.K.JonesA.S.TarnawskiSurvivin: a novel target for indomethacin-induced gastric injuryGastroenterology128120056373

- S.MilaniA.CalabròRole of growth factors and their receptors in gastric ulcer healingMicrosc Res Tech5352001360371

- T.NguyenChaiJ.LiA.T.AkahoshiT.TanigawaA.S.TarnawskiNovel roles of local IGF-1 activation in rat gastric ulcer healing: promotes actin polymerization, cell proliferation, reepithelialization and induces COX-2 in a PI3K-dependent mannerAm J Pathol1704200712191228

- R.PaiB.SoreghanI.L.SzaboM.PavelkaD.BaatarA.S.TarnawskiProstaglandin E2 transactivates EGF receptor: a novel mechanism for promoting colon cancer growth and gastrointestinal hypertrophyNat Med832002289293

- T.OkudaSystematics and health effects of chemically distinct tannins in medicinal plantsPhytochemistry66200520122031

- A.A.RahimE.RoccaJ.SteinmetzM.J.KassimM.S.IbrahimH.OsmanAntioxidant activities of mangrove Rhizophoraapiculata bark extractsFood Chem1072008200207

- B.BerenguerL.M.SanchezA.QuileaM.Lopez-BarreiroO.De HaroJ.Galvezet alProtective and antioxidant effects of Rhizophora mangle L. against NSAID-induced gastric ulcersJ Ethnopharmacol77200613

- J.AlankoA.RiuttaP.HolmI.MuchaH.VapataloT.Metsa-KetelaModulation of arachidonic acid metabolism by phenols: relation to their structure and antioxidant/prooxidant propertiesFree Radic Biol Med261999193201

- L.M.S.PereraD.RuedasB.C.GomezGastric antiulcer effects of Rhizophora mangle LJ Ethnopharmacol77200113

- A.J.Al-RehaileyT.A.Al-HowirinyM.O.Al-SohaibaniS.RafatullahGastroprotective effects of ‘Amla’ Emblica officinalis on in vivo test models in ratsPhytomedicine92002515522

- E.GonzalesI.IglesiasE.CarreteroA.VillarGastric cytoprotection of Bolivian medicinal plantsJ Ethnopharmacol702000329333

- M.KonigE.ScholzR.HartmannW.LehmannH.RimplerEllagitannins and complex tannins from Quercuspetraea barkJ Nat Prod57199314111415