Abstract

Although heifers can have better conception rates than cows, they are still subject to poor estrus detection and economic losses from reduced reproductive efficiency. Tail paint has been successful in identifying estrus, but behaviors such a licking or rubbing have been believed to remove the paint and lead to false-positives. To investigate tail paint utilization and potential relationships among behaviors, eighteen Holstein heifers were randomly assigned to one of three treatments: a control tail chalk (CON), tail chalk with proprietary ingredient (CHALK+); and a spray formulation (SPRAY). Experimental design was a replicated 3 × 3 Latin square. Visual observations were performed in 30 min segments every 2 h from 6 AM to 6 PM. Ovaries were examined via ultrasound imaging on d 0, 7, and 9 of each period. The presence of follicles or a corpus luteum (CL) was recorded with their respective sizes. Heifers receiving SPRAY had a lower number of licks received per day and less tail paint removed regardless of day or follicle size when compared with CON or CHALK+. Rump lick received, chin rest received, anogenital sniff received, mount received, and both initiated and received behaviors for attempt to mount occurred more in heifers with large follicles regardless of day. Producers looking for heifers to breed should focus on those receiving rump lick, chin resting, anogenital sniff, mount, and attempt to mount. The use and combination of these estrus detection tools can improve reproductive efficiency in dairy operations.

1 Introduction

Similar to dairy cows, heifers experience reproductive challenges that contribute to economic losses due to delay of pregnancy resulting from poor estrus detection. It has been estimated that the US dairy industry loses approximately $300 million yearly to erroneous diagnosis and failure to detect estrus [Citation1]. Although heifers usually have better conception rates than cows, with a mean rate of 57% in 2005 [Citation2], failure in estrus detection and consequently breeding those animals, may lead to poor reproductive efficiency.

The use of tail paint as an estrus detection aid dates back to Victorian and New Zealand dairy farms in the late 1970’s [Citation3]. The paint strip method detects cows that are in estrus by indicating those which have been mounted, resulting in the tail paint being rubbed off. Using this estrus detection aid and visual observation, New Zealand herds had an AI rate > 90% [Citation3]. Estrus detection efficiencies using a tail paint method have been reported to be >94% in heifers [Citation4] and tail paint has been reported to have a higher sensitivity than heat mount detectors and activity monitors [Citation5]. Tail paint has also been compared to other detection techniques such as visual observation and radiotelemetry, with no differences in efficiency or accuracy between the techniques [Citation6–Citation7]. One limitation of the tail paint system is the possibility of false-positives, when cows are detected by the tail paint to be in estrus but are not [Citation8]. Tail paint has been shown to result in 5% false positives [Citation3] which causes producers to doubt its efficacy for detecting estrus. Previous studies have involved enamel paint, tail chalk, and a combination of tail paint plus raddle marking [Citation3,Citation4,Citation8]; however, few studies have compared multiple tail paint formulations. Therefore, this study did not try to analyze if tail paint is an adequate detection aid as has been frequently proven in literature, but instead aimed to compare different types of tail paint with behaviors typically used to detect estrus and those that may cause false-positives.

Behavioral studies have mainly focused on lactating dairy cow behavior, and most of the studies focusing on estrus behaviors in dairy heifers were done over two decades ago [Citation9–Citation11]. Traditionally, standing estrus has been defined as the period in which a cow makes no effort to escape when being mounted [Citation12]. Thus, standing for mounting has been the primary sign of true estrus, but has been reported in very low frequencies in literature and can be easily overlooked [Citation11,Citation13]. In addition, it has been reported that some cycling animals have “silent heats” in which mounting behavior is not performed [Citation14]. Therefore, observing other signs associated with estrus have generated higher estrus detection rates [Citation15]. To aid the understanding of behaviors in dairy cattle, classifications have been made such as: estrus interactions, those which are associated with standing estrus in literature; antagonistic interactions, those that are aggressive or threatening to others; and social interactions, those that occur when an animal shows interest in another without any threatening, aggressive, or submission postures [Citation11]. Social interactions (such as licking or rubbing behaviors) may lead to the removal of tail paint and consequently result in false-positives for estrus detection. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to compare the behaviors associated with 3 different types of tail paint formulations in Holstein heifers with an emphasis on social behaviors and the removal of tail paint.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Animals and housing

The University of Illinois Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all following experimental procedures. Eighteen (n = 18) Holstein heifers were balanced according to their age (13.7 ± 1.2 mo), BW 394 ± 32 kg, and BCS 3.43 ± 0.1, on a scale of 1 = emaciated to 5 = obese) and housed in free stalls with sand bedding and headlocks at the University of Illinois Dairy Cattle Research Unit (Champaign-Urbana, Illinois). All heifers received the same total-mixed ration fed once daily (∼1200 h) to fulfill the requirements outlined by the 2001 National Research Council [Citation16]. The experimental period was 6 wk.

2.2 Experimental design and treatments

The experiment was performed using a 3 × 3 replicated Latin square design with 3 animals per square and 6 total squares for 3 periods of 14 d each. The heifers were randomly assigned to one of 3 treatments in each period: control (CON), a commercially available chalk formulation; a chalk formulation with an added proprietary ingredient designed to discourage licking (CHALK+); or a commercially available formulation with the same ingredients as CON but with a spray paint consistency (SPRAY). All treatments were orange in color (All Weather PaintStick, LA-CO Industries, Elk Grove, IL). Treatments were refreshed once a day before feeding time. Old treatments were completely removed at the end of each period prior to application of the new treatment. Treatments were evaluated once per day before re-application to score the degree of tail paint removal (TPR). If no paint was removed from the previous day, the score was 0; if less than half was removed, the score was 1; and a score of 2 was given if more than half or all was removed ().

2.3 Estrus synchronization and follicle size

An Ovsynch protocol was used starting on d 0 of each period (d 0: GnRH: 2 mL of Factrel, Zoetis, Florham, NJ); d 7: PGF2a: 5 mL of Lutalyse, (Pfizer Animal Health, New York City, NY); d 9: GnRH to stimulate periods of high and low interactions. The protocol was not used for timed AI, but as an attempt to stimulate groups of heifers for increased estrus behaviors. A protocol was used with a second shot of GnRH to increase the proportion of heifers showing estrus in d 10 [Citation17–Citation21]. All injections were given intra-muscularly in the rear leg. Ovaries were examined via ultrasound imaging using the Ibex Pro portable ultrasound (E.I. Medical Imaging, Loveland, CO) with L6.2 transducer (8-5 MHz 66-mm linear array, 12 cm scan depth) on d 0, 7, and 9 of each period. The transducer was inserted into the rectum and placed over the broad ligament and uterine horns to examine the ovaries. Both the right and the left ovaries were examined and images were captured to determine if structures were present. The presence of follicles or corpus luteum (CL) was recorded and Image J (U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) was used to measure follicle size. All follicles were measured using an image with a known length of millimeter, measuring the pixels of the known length, and calibrating the scale from pixels to millimeter. Hormone injections and ultrasound were done prior to daily feeding.

2.4 Behavior observation

Each day, behavior was observed for 30-min every 2 h from 6 AM to 6 PM, for a total of 7 time-points per day. A total of 13 behaviors were observed, adapted from Sveberg et al. [Citation13]. The following behaviors were not observed during this trial: avoid, threat, chase away, flehmen, bellow, follow, lean head, side mount, and head mount. Notes were taken to identify which heifer was the initiator or the receiver, with the exception of play rub, where the initiator and receiver could not be clearly distinguished. Definitions of all behaviors can be seen in . In attempt to give a more clear definition, we modified the following behaviors from Sveberg et al. [Citation13]: winner, the initiator wins in an antagonistic interaction over a resource (such as feed or water) or an interaction in which the behavior cannot be defined, and the receiver (the loser) moves away or changes position. In addition, we included the following behavior and definition to fit the objectives of the study: paint lick (the initiator consistently licks the tail paint of the receiver). Videos were watched retrospectively by one person to verify the observations and record any missed behaviors. The behaviors were recorded as counts of occurrences.

Table 1 Definitions of all behaviors observed in the study.

2.5 Statistical analyses

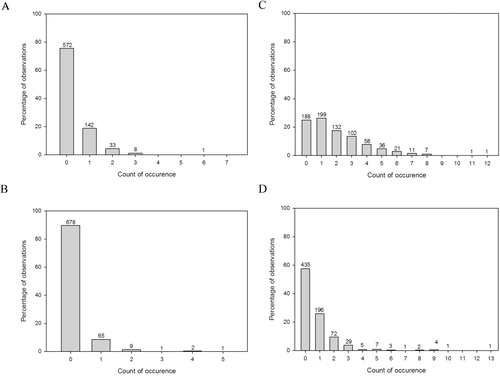

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (v9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Behavior counts were summed for each 30-min time-point with 7 variables per day and TPR had just one variable per day: the score for the degree of product removal. For all analyses, the experimental unit was heifer. The frequencies of traits for all observation time-points in 3 periods were analyzed using PROC FREQ and graphs for 4 behaviors related directly to identifying how heifers respond to the tail paint treatments were generated (). The following behaviors were considered related to the treatments: paint lick, social lick, rump lick, and anogenital sniff. Paint lick was selected because it directly related to licking behavior and TPR. The other behaviors were selected because they may have been mistaken for paint lick or could have demonstrated heifers showing interest in the treatments. In addition, the frequency graphs shown were only for the received behaviors because the treatments on the receiving heifer were affected.

Behaviors were analyzed with a Poisson distribution in PROC GLIMMIX. The model contained heifer as a random effect and the fixed effects of period, treatment (when applicable), and week. Least squares means were calculated for tail paint treatments of related behaviors and a Tukey’s adjustment was used for controlling multiple comparisons error rate. The incidence rate ratio was also determined for the aforementioned behaviors. The incident rate ratio represents the change in the first treatment when compared to the second treatment in terms of a percentage increase or decrease; with the percentage determined by the amount the rate ratio was above or below 1. The PROC MEANS procedure was used to estimate the mean frequency per week of the behaviors and TPR, averaged by all observation time-points in each week. Least squares means were also calculated for traits by comparing the 2 wk of each period. Heifers were expected to come into estrus during the second week from the synchronization protocol; therefore, d 0–6 was considered a time of low activity and d 7–13 was considered a time of high activity.

The measurements for all follicles were ranked in order from smallest to largest in size. This list was then broken into terciles to determine cut-off values for a small, medium, or large follicle. Once the cut-off value for a large follicle was determined, groups for small and medium follicles were combined and analysis was done on just two levels of follicle size. Since estrus was expected in the second week, the follicular data from d 7 and d 9 was compared to the behaviors and TPR. The counts of occurrences for each behavior on d 6, 7, and 8 were summed together and compared to the follicular data from d 7. For the follicular data on d 9, the behavior counts for d 9, 10, and 11 were summed together. The summations of behavior counts were done in order to better detect a difference in estimates. Follicular data and standing activity were analyzed using the PROC MIXED procedure with heifer as a random effect and the fixed effects of period, follicle size, treatment (when applicable) and day of ultrasound. Day of ultrasound was analyzed as a repeated measure. Statistical significance was declared as P values ≤ 0.05, and tendency declared for P values >0.05 and ≤0.10.

3 Results

Social lick and anogenital sniff were the most frequently observed behaviors when compared with paint lick and rump lick (). Approximately 25% of all observations resulted in heifers never receiving a social lick, whereas we observed heifers never receiving paint lick or rump lick 76% and 90% of the time, respectively. Anogenital sniff occurred the most at any one time with up to 13 observations in a 30-min period. However, social lick was the only behavior where heifers received at least one count for more than 50% of all observations. Although paint licking is reported on dairy farms, the behavior is very rare compared to other types of licking. Heifers received more than one paint lick less than 2% of all observations.

Least squares means of treatments for TPR and related behaviors are in . Paint lick received, anogenital sniff received, and TPR had treatment differences (P < 0.001, P = 0.04, and P < 0.001, respectively). SPRAY had a lower treatment mean for TPR and paint lick received (1.80 and 1.18, respectively) than either CON (6.78 and 2.50) or CHALK+ (5.65 and 2.33). However, SPRAY received more anogenital sniffs than CON, and CHALK+ was not different from either CON or SPRAY.

Table 2 Least squares means and associated standard errors of the mean (SEM) for the degree of tail paint removal (TPR) and behaviors related to the tail paint treatments for 18 dairy heifers.

The Poisson regression model for the related traits with significant treatment differences is shown in . The CON treatment was 272% more likely to be removed compared with SPRAY (P < 0.001). A tendency was observed for CON to be removed 20% more than CHALK+ (P = 0.06), and SPRAY was 68% less likely to be removed than CHALK+ (P < 0.001). No difference was detected (P = 0.63) in paint lick received between the two chalk formulations (CON and TRTA), with CON being slightly (7%) more likely to be licked than CHALK+. In addition, CON was 112% more likely to be licked than SPRAY (P < 0.001) and SPRAY was 49% less likely to be licked than CHALK+ (P < 0.001).The opposite was observed for anogenital sniff. The CON treatment was 27% less likely to receive an anogenital sniff than SPRAY (P = 0.01).

Table 3 Incident ratio from Poisson regression for traits with treatment differences by comparison of tail paint treatments for 18 dairy heifers.

Analysis of expected low activity and high activity is reported in and . Tail paint removal was greater in periods of expected low activity (P < 0.01). A difference in week was also observed for both initiated and received behaviors for: paint lick (P = 0.05), social lick (P = 0.01), rump lick (P = 0.05), body butt (P < 0.01), chin rest (P < 0.01), and mount (P < 0.01). Of these, the behaviors that may be more related to social interactions (paint lick, social lick, and rump lick) were observed more frequently in wk 1 when heifers were expected to exhibit low activity. Conversely, the estrus and antagonistic behaviors (body butt, chin rest, and mount) were more frequently observed in wk 2 when heifers were expected to come into estrus and have higher activity.

Table 4 Least squares means of initiated behaviors by comparison of expected low activity in wk 1 and high activity in wk 2.

Table 5 Least squares means of received behaviors and tail paint removed (TPR) by comparison of expected low activity in wk 1 and high activity in wk 2.

Using follicular measurements, a large follicle was determined to be 12.4 mm or greater and was only recorded in the absence of a CL ( and ). On d 7, there were 10 heifers with a large follicle in the first period, 7 in the second period, and 6 in the third period. On d 9, there were 5 heifers with a large follicle in the first period, 9 in the second period, and 10 in the third period. We observed differences in follicle size for rump lick received (P < 0.01), chin rest received (P < 0.01), anogenital sniff received (P = 0.02), mount received (P < 0.01), and both initiated and received behaviors for attempt to mount (P = 0.03 and P < 0.01, respectively). A tendency was observed for differences in mount initiated (P = 0.08) and both winner initiated and winner received (P = 0.07). For all traits with a significant difference in follicle size, the behaviors occurred more often on d 7 and on d 9 when there was a large follicle, compared with heifers without a large follicle.

Table 6 Estimates of initiated behaviors by follicle size for 18 dairy heifers on day 7 and day 9 of 3 periods, as determined by ovarian ultrasound.

Table 7 Estimates of received behaviors and tail paint removed (TPR) by follicle size for 18 dairy heifers on day 7 and day 9 of 3 periods, as determined by ovarian ultrasound.

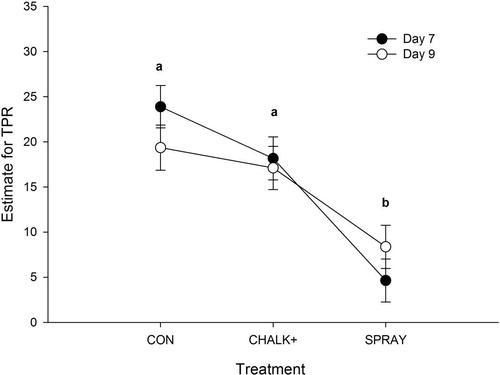

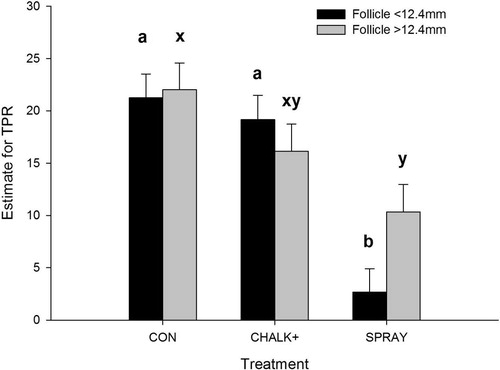

The degree of TPR was greater (P < 0.01) for wk 1 compared to wk 2 () and no difference (P = 0.48) between heifers with large follicles or heifers without large follicles (). Because this was opposite of what we expected, and show results to further investigate these findings. shows an interaction between treatment and day of ultrasound. Heifers had more TPR for CON versus SPRAY on d 7 and d 9 (P < 0.02). Heifers had more TPR for CHALK+ versus SPRAY on d 7 (P < 0.001) and a tendency on d 9 (P < 0.08). illustrates an interaction between treatment and follicle size. The treatment by follicle size interaction had a tendency (P = 0.09) and there was a treatment effect (P < 0.001) as expected. Heifers with small follicles receiving CON and CHALK+ had much less TPR than those receiving SPRAY (P < 0.001) and heifers with large follicles receiving CON had much more TPR than those receiving SPRAY (P < 0.02).

4 Discussion

Producers have concerns that heifers may lick the tail paint and yield false positives. We observed a low frequency of tail paint being licked by heifers when compared with the other licking behaviors. It is possible that licking seen on commercial dairy farms may be primarily from social licking rather than heifers licking the tail paint or may be mistaken for anogenital sniffing, a more frequent behavior.

Heifers with the SPRAY treatment received more anogenital sniffs. This could indicate that heifers show interest in that particular tail paint treatment compared with the others. However, heifers with SPRAY received fewer paint licks and had lower TPR compared with CON and CHALK+, indicating that SPRAY is a good tail paint to use for fewer false-positives when determining heat. This may be from the different consistency of the SPRAY treatment (spray paint) versus the chalk formulations of CON and CHALK+. No differences were found in paint lick or anogenital sniff received between CON and CHALK+. The experimental ingredient in CHALK+ did not seem to deter the interest of the heifers compared with CON since there was no difference in licks or sniffs, however CHALK+ tended to be removed less and may yield less false positives than CON.

During wk 1, when we expected activity to be low, there was more product removed (greater TPR). This is opposite of what we expected: greater TPR with increased mounting in wk 2, since we expected more heifers in estrus during wk 2 and mounting should cause product removal. These results may be from the differences in treatments. Treatments CON and CHALK+ were removed more than SPRAY regardless of the follicle size or day, with the exception of heifers with large follicles receiving CHALK+ ( and ). This could also have been from the increase in social behaviors during wk 1 or from heifers with large follicles that were not noticed since ultrasound was only performed on the first day for wk 1. Unlike CON and CHALK+, heifers receiving SPRAY had greater TPR at times of increased activity and estrus behaviors and with increased number of large follicles, validating that SPRAY is more effective at detecting estrus than the other formulations.

Antagonistic and estrus behaviors that occurred more during high activity in wk 2 include body butt, chin rest, and mount. Both initiated and received behaviors were increased and this was expected since heifers should have been in estrus during wk 2. This agrees with previous studies that showed higher incidence of antagonistic behaviors in cows during times of estrus [Citation12,Citation13]. Of the social behaviors, all three licking behaviors (social, paint, and rump) were increased in wk 1. The decrease in social licking during wk 2 disagrees with results from Sveberg et al. that showed higher incidence of social licking during times of estrus [Citation13], likely due to the use of cows in the Sveberg trial compared to more curious and active heifers in the present study.

Results from this study have shown a higher incidence for received estrus behaviors (chin rest, anogenital sniff, mount, and attempt to mount) in heifers with large follicles versus heifers without large follicles on both d 7 and d 9 ( and ). Mounting is still considered the gold standard for estrus detection; however, it can easily be missed from lack of observation times, short duration of the behavior, or because some animals just do not show signs of mounting when in estrus [Citation12,Citation13]. Van Vliet and Van Eerdenburg reported that just 37% of estruses were accompanied by standing mounts [Citation22], and Kerbrat and Disenhaus noted that mounting only represented 8% of all estrus behaviors [Citation11]. Producers should look to the other antagonistic and estrus behaviors to determine breeding prospects. However, caution should be taken if only chin resting and anogenital sniffing received is observed since these behaviors can be performed in nonestrous stages and are less predictive than mounting [Citation13,Citation21]. Rump lick received also had a higher incidence in heifers with a large follicle and may be combined with the received antagonistic behaviors to identify estrus.

Looking to the initiated behaviors, both mount and attempt to mount had higher incidences in heifers with large follicles. This agrees with previous research that heifers in estrus attempt more mounts than in other estrous stages, followed by pro-estrus heifers attempting more mounts than non-estrus heifers [Citation10]. Furthermore, Hurnik et al. reported that 79% of all attempted mounts were performed by animals in estrus and that 90% of mounted animals were in estrus [Citation12]. We can reason that if mounting is observed in heifers, both the initiator and receiver may be in estrus or close to estrus. Unlike previous studies with cows, our results did not indicate differences for heifers with or without large follicles for head butt or chase up received [Citation12,Citation13].

5 Conclusions

Dairy operations that have problems with tail paint removal and false-positives may benefit from changing to a tail paint product with a different consistency, such as a spray formulation. Producers observing behaviors for estrus detection can focus on heifers receiving rump lick, chin resting, anogenital sniff, mount, and attempt to mount. Likewise, heifers that initiate mounts, attempt to mount, or push and nudge other heifers should also be considered for breeding and may be in estrus or pre-estrus.

Competing interests

There are no conflicts of interest.

Notes

Peer review under responsibility of Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Cairo University.

References

- P.L.SengerThe estrus detection problem: new concepts, technologies, and possibilitiesJ Dairy Sci77199427452753

- M.T.KuhnJ.L.HutchisonG.R.WiggansCharacterization of Holstein heifer fertility in the United StatesJ Dairy Sci89200649074920

- K.L.MacmillanR.J.CurnowTail painting – a simple form of oestrus detection in New Zealand dairy herdsNew Zeal J Exp Agric51977357361

- K.L.MacmillanV.K.TaufaD.R.BarnesA.M.DayR.HenryDetecting estrus in synchronized heifers using tailpaint and an aerosol raddleTheriogenology30198810991113

- J.CavalieriV.E.EaglesM.RyanK.L.MacmillanComparison of four methods for detection of oestrous in dairy cows with resynchronized oestrous cyclesAust Vet J812003422425

- M.A.PalmerG.OlmosL.A.BoyleJ.F.MeeEstrus detection and estrus characteristics in housed and pastured Holstein-Friesian cowsTheriogenology742010255264

- C.KamphuisB.DelaRueC.R.BurkeJ.JagoField evaluation of 2 collar-mounted activity meters for detecting cows in estrus on a large pasture-grazed dairy farmJ Dairy Sci95201230453056

- J.A.PenningtonC.J.CallahanUse of mount detectors plus chalk as an estrous detection aid for dairy cattleJ Dairy Sci691986248252

- R.J.EsslemontR.G.GlencrossM.J.BryantG.S.PopeA quantitative study of pre-ovulatory behaviour in cattle (British Fresian heifers)Appl Anim Ethol61980117

- S.D.HelmerJ.H.BrittMounting behavior as affected by stage of estrous cycle in Holstein heifersJ Dairy Sci68198512901296

- S.KerbratC.DisenhausA proposition for an updated behavioural characterization of the oestrus period in dairy cowsAppl Anim Behav Sci872004223238

- J.F.HurnikG.J.KingH.A.RobertsonEstrous and related behavior in postpartum Holstein cowsAppl Anim Ethol219755568

- G.SvebergA.O.RefsdalH.W.ErhardE.KommisrudM.AldrinI.F.TveteBehavior of lactating Holstein-Friesian cows during spontaneous cycles of estrusJ Dairy Sci94201112891301

- R.H.FooteEstrus detection and estrus detection aidsJ Dairy Sci581975248256

- F.J.C.M.Van EerdenburgH.S.H.LoefflerJ.H.Van VlietDetection of oestrus in dairy cows: a new approach of an old problemVet Quart1819965254

- National Research CouncilNutrient requirements of dairy cattle7th revised ed.2001National Academy PressWashington, DCp.381

- B.-A.TenhagenS.KuchenbuchW.HeuwieserTiming of ovulation and fertility of heifers after synchronization of oestrus with GnRH and prostaglandin F2alphaReprod Domest Anim4020056267

- O.DemiralM.ÜnM.AbayT.BekyürekA.ÖztürkThe effectiveness of cosynch protocol in dairy heifers and multiparous cowsTurk J Vet Anim Sci302006213217

- S.El-ZarkounyConception rates for standing estrus and fixed-time insemination in dairy heifers synchronized with GnRH and PGF2αTurk J Vet Anim Sci342010243248

- F.S.LimaH.AyresM.G.FavoretoR.S.BisinottoL.F.GrecoE.S.RibeiroEffects of gonadotropin-releasing hormone at initiation of the 5-d times artificial insemination (AI) program and timing of induction of ovulation relative to AI on ovarian dynamics and fertility of dairy heifersJ Dairy Sci94201149975004

- J.S.StevensonSynchronization and artificial insemination strategies in dairy herdsVet Clin N Am-Food A322016349364

- J.H.Van VlietF.J.C.M.Van EerdenburgSexual activities and oestrus detection in lactating Holstein cowsAppl Anim Behav Sci5019965769