Abstract

The nemopterid Dielocroce chobauti (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae) was surveyed for two successive years in two different ecosystems. Ecological and morphological analyses were conducted to collect more information regarding this insect. Both male and female population fluctuations were discussed. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) micrographs were generated to describe the D. chobauti mouthparts. This report describes the first record of this insect in the Almadina region.

1 Introduction

The Nemopteridae family includes approximately 150 species worldwide, of which seven have been recorded in Europe [Citation1] and eight in Turkey [Citation2–Citation5]. Sole et al. [Citation6] studied the molecular phylogeny of the South African Nemopteridae genera, and a new species of the Nemopteridae family was recently reported in Chile [Citation7]. Most of these insects are plant-feeding, although some are predators [Citation8,Citation9]. Both groups are considered beneficial for maintaining a healthy ecosystem: plant-feeding nemopterids primarily aid with pollination, whereas predatory nemopterids participate in biological control.

A few studies have focused on the Nemopteridae family. Nemopteridae wings provide these insects an impressive appearance, especially for adults. Because of adaptations in their hindwings, Nemopteridae are commonly referred to as spoon-winged, tail-winged, lacewinged or thread-winged. These species are taxonomically categorized in the order Neuroptera. Sole et al. [Citation6] investigated the phylogeny and biogeography of South African spoon-winged Nemopteridae and reported the first molecular phylogeny for South African Nemopterinae.

Members of the Nemopteridae family exhibit chewing mouthparts with well-developed biting mandibles that are adapted to feeding on nectar and pollen [Citation9–Citation14]. The maxillae are the primary organs mediating food uptake in Nemoptera sinuata (Nemopteridae), which has adapted to feed on pollen and nectar [Citation9]. Several authors have indicated adult lacewing insects are mostly predators with biting mouthparts that undergo a complete metamorphosis during their life cycle [Citation15,Citation16].

Approximately 23 species belonging to different neuropteran families have been documented in Iran with two belonging to Nemopteridae. The neuropteran fauna has been studied in various regions in Iran [Citation17–Citation22]. Dielocroce baudii, Dielocroce maxima and Dielocroce vartianae also belong to the Nemopteridae, and D. baudii was first observed on the Asian continent in 2005 [Citation5]. Satar and Ozbay [Citation3] identified Dielocroce ephemera in Turkey. An investigation by Popov [Citation10] suggested that the Nemopteridae family included approximately 90 taxa.

However, Dielocroce chobauti, which belongs to this family, has not been ecologically or morphologically assessed. To address this lack of information on D. chobauti, the present study evaluated the ecology and morphology of this insect in two different environments.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Ecological analyses

2.1.1 Study sites

Insects were collected from sites with two different environments within the Madina region of Saudi Arabia. The samples were collected and sent to the British Natural History Museum for identification, and they were identified as D. chobauti (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae). The survey was performed for two different ecosystems located ca. 100 km west of Madina, KSA. It only rains a few times per year in either location. Both sites, which are described below, exhibit desert climates and relative humidities of approximately 25%.

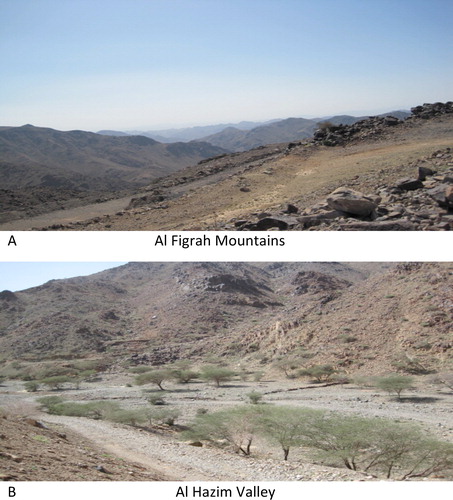

2.1.1.1 Al Figrah Mountains

The first site is located in the Al Figrah Mountains, approximately 1800 m above sea level (A). This mountainous region is cold in the winter (5 °C) but hot in the summer (30 °C). The vegetation primarily consists of small, diverse trees, including short juniper trees.

2.1.1.2 Al Hazim Valley

Al Hazim is a deep valley 1300 m above sea level (B). The vegetation in Al Hazim predominantly consists of large acacia trees and only includes flowering plants certain times of the year. The temperature ranges from 15 °C to 45 °C.

2.2 Sampling

The surveys were performed from January to December for two successive years (2009–2010), and samples were collected three times per month. Adults were collected at night when gathered around light emitted by self-charging, transportable electric bulbs, and some samples were collected by hand as the animals rested. The captured samples were identified as male or female.

2.3 Morphological analyses

Dissected adult heads (fresh samples) were prepared and analyzed using a JEOL_Superscan SS-550 scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Japan. Digital photos were processed using Adobe Photoshop. All photographs were obtained using a digital camera (Nikon Coolpix P510, 16.1 megapixels, Japan). The digital photos were captured using a graph-paper background to determine the image sizes.

The obtained data were statistically analyzed via an ANOVA, and the standard error for the mean was recorded.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Ecological analyses

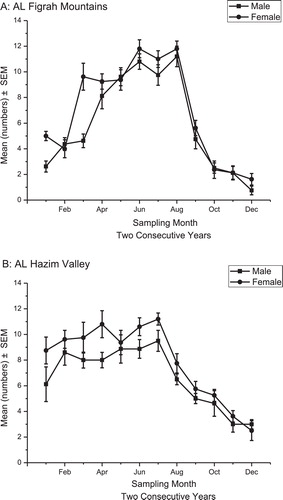

A indicates females slightly outnumbered males in the Al Figrah Mountains; however, the difference was not significant. The population in the Al Hazim Valley region also fluctuated; however, a significant difference between the female and male populations was detected. Due to the different temperatures for the investigated environments, the numbers of insects in the Al Figrah Mountains was greatest in September and then sharply decreased in October, whereas the greatest number of insects in the Al Hazim Valley were recorded at the end of July that same year before they decreased gradually. In general, we concluded the Al Figrah Mountains contained more specimens for both males and females than the Al Hazim Valley (B).

Fig. 2 The population fluctuation of male and female of D. chobauti in (A) Al Figrah Mountains and (B) Al Hazim Valley.

Environmental conditions can limit many living organisms. Organisms might adapt differently to the altitude differences between the two study environments. For example, in winter, the population was significantly larger in the Al Hazim Valley than the Al Figrah Mountains. However, no significant population density differences were observed between the two regions in either the spring or summer. In the fall, the insect population in the Al Figrah Mountains decreased sharply relative to the Al Hazim Valley. The altitude differences between these sites likely resulted in severe temperature variations and other related climatic conditions that directly affected the prevalence or disappearance of certain insect species.

This is the first survey for D. chobauti in its local environment in Saudi Arabia. All Dielocroce species exhibit nocturnal activity and can therefore be collected using a light source [Citation23]. Satar [Citation5] first identified D. baudii as a new Anatolian fauna in mountainous environments, and that characterization supports the present results. D. chobauti has not been previously documented in the regions examined in this study. Thus, this study is the first record for this species as noted above. Similarly, El-Hamouly and Fadl [Citation24] indicated D. chobauti is represented in Egyptian fauna and distributed locally throughout this region (Suez Road, Sina, Wadi Digla, Sadi Guffan, Sadiy Raib and upper and lower Egypt). Mansell and Erasmus [Citation25] found climate change in South Africa contributed to redistributing some neuropteran families, such as Nemopteridae, which potentially caused some to become endemic in this area. The nemopterid fauna in Iran contains several species (D. maxima and D. vartianae) [Citation22] similar to those investigated in this study, particularly regarding climatic conditions. Satar [Citation5] identified varying numbers of male and female D. baudii in different areas of Turkey, which agrees with the findings of this study.

3.2 Morphological analyses

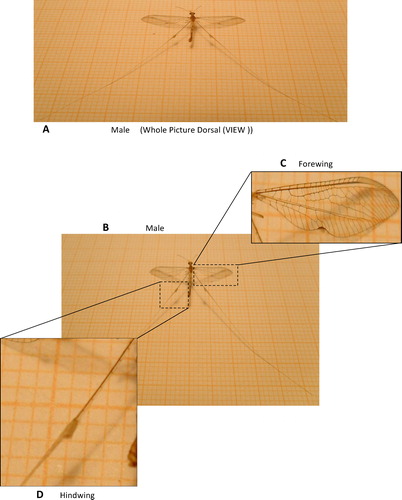

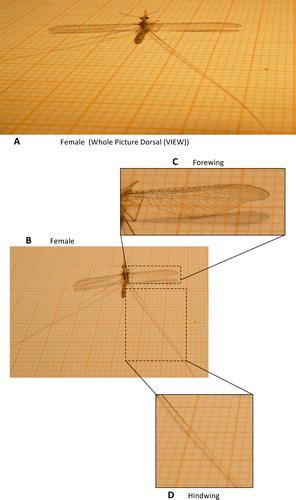

Morphological analyses of this insect indicated differences between the male and female wings. However, the forewings were membranous for both the examined males and females. The observed differences are shown clearly in and and included venation in the male forewings, which differs from that in the female wings, and the presence of a dark-colored notch at the anal margin for male wings. The hindwings were modified in both males and females. They both appear thread-like, with a swollen spot on the proximal region of the male wings (D). The hindwings of these insects is approximately three times the length of their forewings. Most nemopterids are referred to as spoon-winged or thread-winged based on their hindwing adaptations, which are easily recognizable [Citation9]. These adaptations likely play a significant role in mimicry to avoid natural enemies and aid in predation [Citation26–Citation28].

3.3 Mouthpart morphology

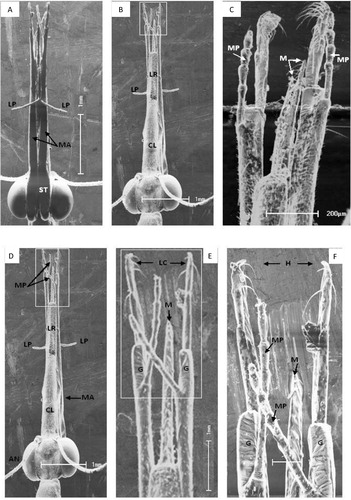

The D. chobauti head harbors mouthparts that consist of an elongated rostrum formed by the clypeus, labrum, mandibles, maxillae and labium. The mouthparts assume an orthognathous position. Male and female mouthparts appear similar. The labrum is connected to the clypeus and exhibits a convex shape on its outer surface extending forward to cover the other mouthparts during rest. Additionally, the labrum may help bring food into the oral cavity. The labrum is twice as long as the clypeus and is narrower in its distal region (B and C).

Fig. 5 (A–F) Head and mouthparts of Dielocroce chobauti (SEM micrographs). (A) Head in ventral view, MA – maxillae (arrows), LP – labial palp, ST – stipes; (B) head in dorsal view, CL – clypeus, LP – labial palp, LR – lubrum and ; (C) M – mandibles (arrows), MP – maxillary palp (arrow). (D) Dorsal view, AN – antenna, CL – clypeus, MA – maxilla (arrow), from lateral side; (E) magnification of epical part of (D), G – galea, LC – lacinia, and (F) high magnification of apical part of (E), and H – hooks (arrows) in the inner apical point of lacinia.

The mandibles (M) are paired, sclerotized, located on opposite sides of the labrum (ventral to the labrum) and resemble tweezers (C). Their proximal widths first increase before gradually decrease until forming a fine, sharp tip in their distal regions; retrorse teeth are visible at high magnifications (F). The inner surface of these mandibles is grooved and likely work together to function as a lumen. This structure may regulate the insect feeding mode, which behaves as a predator that sucks body fluids from its prey.

The maxillae contain the cardo, which is adjacent to the head (A; arrow) on the ventral sid, and the stipes, which are the longest part of the maxillae (A, D, E and F). The distal maxillae consist of maxillary palps containing four segments that join the external upper edge of the galea. The galea reside in the lower part of the distal, apical region of the maxillae and exhibit long, thin hairs that may function as sensors along with the laciniae, which appear to be longer than the galea. The laciniae exhibited hooks (teeth) (E and F). These hook-like structures may help capture insect prey to support this predatory insect.

The labium is located between the two maxillae, as observed from the ventral view (A); however, it appears shorter than the other insect mouthparts. The labium contains the prementum and legula and a pair of four-segmented labial palps. The legula extends forward and ends in an extremely sharp distal tip.

This study performed a morphological analysis of D. chobauti mouthparts, which indicated these insects are sucking predators (carnivorous). Additional surveys and follow-up analyses indicated these insects did not appear during the day (they were nocturnal). Moreover, the environments did not contain a continuous supply of flowering plants and were rather desert like. All of these observations support the feeding preference of this insect as carnivorous and not herbivorous. Our results differ from the findings of Krenn et al. [Citation9], who described the Nemoptera sinuate (Nemopteridae) mouthparts as being adapted for pollen and nectar uptake, which indicating a functional role for feeding on flora. These findings differ from previous studies [Citation17,Citation26,Citation29] that described the mouthparts of certain Nemopteridae genera that feed on flowers. The results for this study agree with those of Sliva and Grunewald [Citation30], who indicated the laciniae of Lutzomyia migonei (Diptera) serves to feed on other insect hosts, and these mouthparts appear suitable for hooking into soft skin. Sharma et al. [Citation8] reported that the Neuroptera order contains numerous predaceous insects that feed on soft-bodied insects, including pests. Therefore, this order warrants further study. In conclusion, the described insect warrants additional study to clarify its feeding and habitat characteristics and preferences and distribution range.

Acknowledgments

I am deeply grateful to my colleague Dr. Reda Ibrahim for reviewing this manuscript. I also thank the British Natural History Museum for the sample identification.

Notes

Peer review under responsibility of Taibah University.

References

- H.AspockH.HolzelU.AspockKommentieter catalog der Neuroptera (Insecta: Raphidioptera, Megaloptera, Neuroptera) der WestpalaarktisDenisia22001606

- A.SatarC.OzbayEggs, first instar larvae and distribution of the neuroptrerids Lertha extensa and L. shappardi (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae) in southeastern TurkeyZool. Middle East3220049196

- A.SatarC.OzbayRemarks on Neuroptera of southeastern TurkeyEntomol. Fenn.152004219224

- A.SatarS.CanbultC.OzbayRedescription and rediscovery of Dielocroce ephemera (Gerstaecker 1894) in TurkeyZool. Middle East312004107110

- A.SatarDielocroce baudii (Griffini, 1895), a new Nemoptid for Anatollia (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae)Acta Entomol. Slov.13120056569

- C.SoleC.ScholtzJ.BallM.MansellPhylogeny and biogeography of south African spoon-winged lacewings (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae: Nemopterinae)Mol. Phylogenet. Evol.662013360368

- R.MillerL.StangeA new species of Stenorrhachus McLachlan Chile (neuropteran: Nemopteridae) with biological notesInsecta Mundi20122533

- R.SharmaS.TalmaleP.KulkarniFirst record of a nemopterid (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae) from MaharashtraZoos Print J.1652001487493

- H.KrennB.Gereben-KrennB.SteinwenderA.PopovFlower visiting neuropteran: mouthparts and feeding behaviour of Nemoptera sinuate (Nemopteridae)Eur. J. Entomol.1052008267277

- A.PopovUber die praimaginalen stadien palaarktischer verterterder ordnung neuropteran und versuch einer neuen systematischen gruppierung der familien mit rucksicht auf ihre morphologischen und okologischen besonderheitenBull. Inst. Zool. Mus.73197379101

- A.PopovAutecology and biology of Nemoptera sinuata Olivier (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae)Acta Zool. Acad. Sci. Hung.4822002293299

- T.NewPlanipennia lacewingsM.FischerHandbook of ZoologyArthropoda: Insecta. Part 30vol. IV1989Walter de GruyterBerlin, New York132

- U.AspockH.ApockOrdnung Neuroptea (Planipennia), NetzflugerH.DatheLehrbuch der Speziellen Zoologie. Band I: Wirbellose Tiere 5. Teil: Insecta2003Spektrum Akademischer VerlagHeidelberg, Berlin564584

- J.VillenaveD.ThierryA.MamunT.LodeE.Rat-MorrisThe pollens consumed by common green lacewings Chrysoperla spp. (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) in cabbage crop environment in western FranceEur. J. Entomol.1022005547552

- D.GrimaldiM.EngelEvolution of the Insects2005Cambridge University PressNew York755

- J.JepsonV.MakarkinR.CoramLacewings (Insecta: Neuroptera) from the lower cretaceous Purbeck Limestone group of southern EnglandCretac. Res.3420123147

- H.HolzelZur Kentnisse der Myrmeeoniden des Iran (Planipennia: Myrmeleonidae)Stutt. Beitr. Zur. Naturk.18119683103

- H.HolzelRedeskription von chrysopa andesi Navas und beschreibung Zweir Neuerarten aus Vorderasiens (Planipennia: Chrysopidae)Z. Arbeitsg. Osterr. Entomol.331981113121

- H.HolzelDie nemopteriden (Fadenhafte) ArabiensNeue Folge Nr.1381999129146

- A.MirmoayediNeuroptera of IranActa Zool. Fenn.2091998163165

- A.MirmoayediV.ZakharenkoA.KrivokhatskyA.YassayieFon Setchatokrilikh (Insecta:Neuroptera) Neuroptera) Nationalnogo Parka Golestane Provinci Kermanshakh (Iran)Izveestia Kharkovskogo Entomologiechesogo Obshestva219995356

- A.MirmoayediNew records of Neuroptera from IranActa Zool. Hug.4822002197201

- R.DoboszL.AbrahamContribution to the knowledge of the Turkish tail-wings (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae)Nat. Som.152009113126

- H.El-HamoulyH.FadlCheck of order neuropteran in Egypt, with a key to familiesAfr. J. Biol. Sci.71201185104

- M.MansellB.ErasmusSouth Africa biomes and the evolution of palparini (Insecta:Neuroptera: Myrmeleontidae)Acta Zool. Hung.4822002175184

- M.PickerB.LeonJ.LondtThe hypertrophied hindwings of Palmipenna aeoleoptera Picker, 1987 (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae) reduce attack by robber flies by increasing apparent body sizeAnim. Behav.421991821825

- B.LeonM.PickerFunction of the hind wings of Palmipenna aeoleoptera Picker (Insecta: Neuroptera: Nemopteridae)M.W.MansellH.AspockAdvances in Neuropterology. Proceeding of the Third International Symposium on Neuropterology, South Africa, 198819908994

- B.LeonM.PickerBehavioural thermoregulation in Palmipenna aeoleoptera Picker (neuropteran): do the hypertrophied hindwings play a role?J. Insect Behav.31990381394

- M.MansellThe Crocinae of southern Africa (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae)J. Entomol. Soc. S. Afr.431980341365

- O.SilvaJ.GrunewaldComparative study of the mouthparts of males and females of Lutzomyia migonei (Diptera: Psychodidae) by scanning electron microscopyJ. Med. Entomol.372000748753