Abstract

This paper assesses why participation in markets for small ruminants is relatively low in northern Ghana by analysing the technical and institutional constraints to innovation in smallholder small ruminant production and marketing in Lawra and Nadowli Districts. The results show that the limitations experienced by smallholders, i.e., water shortages during the dry season, high mortality and theft of livestock, persist because of institutional constraints. These include structural limitations related to availability of arable lands, weak support systems for animal production and health services delivery, community values that are skewed towards crop production more than animal husbandry, ineffective traditional and formal structures for justice delivery, and gaps in the interaction between communities and district and national level organizations such as the Ministry of Food and Agriculture, district assemblies, rural banks, and non-governmental organizations as well as traders and butchers. Confronted with such constraints, the strategies that most smallholders have adopted to be resilient entail diversified sources of livelihood, low input use in small ruminant production, and maintaining the herd as a capital stock and insurance. Only a few smallholders (i.e., ‘positive deviants’) engage in market or demand-driven production or exhibit successful strategies in small ruminant husbandry. It is argued in this paper that for the majority of smallholders, market production, which requires high levels of external inputs or intensification of resource use, is not a viable option. The main implications of the study are (1) that other institutional constraints than market access constraints should be addressed, (2) that commercial livestock production should not be idealized as the best or only option (as is being done in many contemporary interventions that aim at incorporating smallholders into commodity value chains), and (3) that different types of small ruminant system innovation pathways should be explored by making use of local positive deviants.

1 Introduction

Worldwide, livestock production systems are undergoing rapid changes in response to population growth, urbanization and increasing incomes. Developing countries are projected to account for 85% of the growth in demand for meat products between 1995 and 2020 [Citation1]. The increasing demand for animal products is expected to improve the incomes and livelihood of smallholders who account for the bulk of production in developing countries. However, most of the increases in livestock production are taking place outside the smallholder sector [Citation1,Citation2]. This is also the case for the production of small ruminants such as goats, because most smallholders have a low market participation that will not easily increase since they invest very little in their management and suffer from high transaction costs [Citation3,Citation4]. High demand for livestock products and low direct market participation by smallholders also describes well the situation in northern Ghana. As elsewhere [Citation2,Citation3,Citation5], several interventions with a focus on smallholder small ruminant commercialization have been made to improve Ghanaian small ruminant production systems and markets, such as the National Livestock Services Project (1993–1999) and the Livestock Development Project (2003–2009). However, these have not changed the small ruminant production and marketing systems in any significant way [Citation6].

Recent studies of agricultural innovation indicate that innovation is not just about adopting new technologies. New technical practices also call for alternative ways of organizing, for example, markets, labour, land tenure and the distribution of benefits [Citation7,Citation8]. Different parts of production systems and of the institutional environment in which they are embedded (e.g., the value chain, the market, the policy environment) thus need to evolve simultaneously in order to enable innovation, and this requires interactions amongst multiple actors [Citation9,Citation10,Citation11]. The realization that many actors and their activities matter for innovation is the essence of innovation systems thinking. An innovation system can be defined as the set of all individual and organizational actors that are relevant to innovation in a particular sector or issue, their interactions and governing institutions [Citation12]. Institutions in this perspective are defined as the rules, standards or principles that co-ordinate interactions [Citation13].

The concept of innovation systems presupposes that they stimulate innovative developments but often they work imperfectly. For example, there may be deficient collaboration amongst actors for innovation to occur, due to differences in focus and incentives [Citation14]. Furthermore, innovation systems might only support innovations that merely sustain dominant practices, instead of enabling radically different pathways of development [Citation15,Citation16]. Hence, innovation systems often do not work as a coherent system in support of innovation, and present ‘innovation system failures’. Klein Woolthuis et al. [Citation17] have reviewed the commonly occurring types of innovation system failure and on a basis of the typology have designed a framework for structured analysis of constraints in innovation processes. This framework can be applied to reveal why a certain desired innovation goal is not achieved [Citation18]. The various constraints in the innovation system failure framework [Citation17] are structured according to their nature: physical (e.g., roads, farming infrastructure, technical devices), knowledge (e.g., extension) and service (e.g., banking) infrastructure; hard institutions (by which is meant the formal rules and regulations that perpetuate an existing regime, or the lack of them, hampering innovation because the actors are unsure how legislation will affect their innovation); soft institutions (by which is meant the implicit, unwritten rules, or ‘the way business is done’, which influences for instance the mind-set for innovation or the propensity to collaborate for innovation). The former also relates to failures concerning interactions amongst actors, expressed by too strong networks (sets of powerful actors that maintain the system status quo in a way that is not conducive to innovation) and weak networks (lack of linkages with actors who can provide new insights, insufficient trust for social learning). The framework also encompasses indicators of the actors’ capabilities for innovating (e.g., education level, time available) [Citation17].

The direct linkage between the technical and institutional dimensions of livestock production systems and the need to address such issues simultaneously has become increasingly recognized in the livestock innovation literature that applies an innovation systems perspective [Citation1,Citation3,Citation9]. Beyond yielding information about constraints to innovation in small ruminant production in northern Ghana, the present paper aims to contribute to the livestock innovation systems literature. It deepens innovation system analysis by applying a comprehensive and systematic framework based on a categorization of so-called innovation system failures [Citation17] to analyse and categorize the coupled technical and institutional constraints.

The overall purpose is to assess why participation in the market for small ruminants is relatively low in northern Ghana, by means of a broad diagnostic study of the institutional and technical constraints to innovation of small ruminant livestock production systems in Lawra and Nadowli Districts.

2 Methodology

2.1 Selection of the domain

A preliminary exploratory study in the Upper West Region in northern Ghana identified a number of strategies that smallholders employ in response to food insecurity [Citation19]. At a workshop held in Elmina, Ghana in June 2009, an expert discussion (involving three university lecturers, one PhD student, one representative of a farmer organization, and two representatives of NGOs) about livestock interventions identified small ruminant keeping as an essential strategy for coping with food insecurity in the three northern regions in Ghana [Citation4,Citation6,Citation20]. A follow-up scoping study showed that a number of development organizations have ongoing livestock production interventions in all the districts in Upper West Region—a further indication of the perceived importance of and opportunities in livestock keeping [Citation21]. The results of the exploratory and scoping studies and the expert discussion were used to select small ruminant production and marketing as an entry point for intervention under the Convergence of Sciences – Strengthening Innovation Systems (CoS–SIS) Programme in northern Ghana.

2.2 Characteristics of the domain, problem description, and research questions

Small ruminants (i.e., sheep and goats) are a significant source of livelihood and food security in northern Ghana where almost all smallholders combine crop production with small ruminant husbandry. Ghana produces only 30% of the national small ruminant meat demand. Northern Ghana accounts for 70% of the local production. The remainder is met by imports from neighbouring countries to the north, i.e., Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger [Citation6]. The vegetation of Northern Ghana is mostly Guinea Savannah grassland that is conducive to livestock grazing. However, the potential of livestock for revenue generation, maintenance of soil fertility, and contribution to household food security in Northern Ghana is often not realised because of a number of persistent constraints. This study's initially sought simply to furnish a descriptive understanding of the constraints so that the potential could be realized. The study was guided by two principal questions:

| 1. | What are the prevailing practices of small ruminant production and marketing in crop–livestock smallholder households in Upper West Region of Ghana? | ||||

| 2. | What are the farm level and higher level (e.g., value chain, policy environment, market) constraints of a technical, infrastructural, institutional, interactional, and capability related nature that hinder small ruminant innovation, with particular reference to improved production and market participation by smallholders? | ||||

2.3 Study design, population, sampling procedure and data gathering methods

An explorative and interpretivist qualitative case study design [Citation22] was employed. This design is suited to uncovering the meaning that people assign to their experiences. The population of this study is smallholder crop–livestock farmers in Upper West Region of Ghana who experience household food insecurity between one and five months in the year [Citation20]. Purposive sampling [Citation23,Citation24] was used first to select the Upper West Region (UWR) out of the three northern regions and to select Lawra and Nadowli Districts out of eight districts in UWR, based on the fact that household food insecurity was shown in the exploratory and scoping studies [Citation19,Citation21] to be high in these areas.

Interviews with staff of the Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA) in Lawra and Nadowli and with other technical experts at two workshops organized in Wa, the regional capital, showed that there are three principal categories of communities in the two selected districts [Citation21]. In order to capture this diversity, purposive sampling [Citation23] was then used to select from the three categories of communities:

| 1. | Communities where smallholders are oriented to trading in livestock: of these, Kumasal (1 km from Babile market) in Lawra District and Tangasie in Nadowli District were selected. | ||||

| 2. | Communities inclined to livestock production: of these, Tabiasi and Dakyiae in Nadowli District were selected (Tabiase was omitted due to time constraints). | ||||

| 3. | Communities oriented towards livestock production and that also have been beneficiaries of recent interventions in the sector. The two selected communities are Oribili and Tankyara near Nandom (in Lawra District), both of which participated in the Small Ruminant Improvement Project implemented by the Animal Research Institute (ARI) from 2003 to 2009. | ||||

Systematic sampling [Citation23] was employed to select 53 compound houses in the five communities (see for number of households interviewed per community). In most of the cases the respondent was the male head or landlord of the compound house. Two female landlords and four other females were interviewed in the absence of the male heads. Snowball sampling [Citation23] also was employed to identify and interview other individual and organizational actors in the supply chain. These actors included traders, butchers, and food sellers (i.e., ‘chop bar operators’) at the two main local markets, i.e., Babile and Tangasie and in the two largest cities in Ghana, i.e., Accra and Kumasi. Other actors were the staff of MoFA in the two districts and at national headquarters, rural banks, district assemblies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and police officers in the two districts.

Table 5 Comparison of households in five communities by type of sale of small ruminants in 2009. Source: Ref. [Citation31] and field interviews 2010.

The interview schedule included the practices of the diverse actors in the small ruminant supply chain, constraints experienced by the actors, and who or what influenced their activities. In addition to the interviews, a review of archival documents (see [Citation4,Citation6,Citation25–Citation27]) and participant observation also were employed. Finally, a farmer group in each of the five communities was invited to rank the identified constraints.

After obtaining a broad view of the limitations in small ruminant production systems in the five communities, the researchers subsequently focused on two of the communities for further institutional analysis. The criteria used in selecting the two communities were participation (Orbili in Lawra District) and non-participation (Tangasie in Nadowli District) in the ARI project and practical considerations such as the distance from Babile (i.e., the residence of the researchers) to the communities. The respondents to the initial interviews indicated that the members of the two communities hardly interacted and therefore that the ARI intervention was not likely to have a spill-over effect.

In order to examine the reasons behind the farmers’ prioritized constraints at Oribili and Tangasie, one-day multi-stakeholder workshops [Citation28] were organized in Lawra and Nadowli Districts, respectively. The participants included farmers, traders and butchers, staff of MoFA, district assembly, NGOs, rural banks, and the police service. The participants were divided into groups during the workshop, based on the first three priority constraints identified by farmers in the respective community (). The Research Associate, whose role in the CoS–SIS Programme is in part the facilitation of multi-stakeholder processes, guided the groups to examine the reasons for the persistence of the limitations, using the socio-technical root system analysis tool [Citation29]. In using the root system analysis, each group was assigned a prioritized constraint identified during the community-based interviews. The groups discussed prevailing practices that contributed to the problem and the reasons why these practices persist. The output of each group's discussion was drawn on a flip chart (). The groups presented in turn their analysis at a plenary session. The limitations identified were converted to a table conceived as an innovation systems failure matrix ().

Table 6 Ranking of constraints in the small ruminant system in five communities in Lawra and Nadowli Districts. Source: focus group meetings, 2010, and institutional analysis workshop at Lawra in 2011.

Table 7 Techno-institutional system analysis of the small ruminant production and marketing system in two communities in Lawra and Nadowli Districts, 2009. Source: Stakeholder workshops, Lawra and Nadowli, 2011.

The data in this study were analysed by the researchers manually, using thematic analysis [Citation30]. All the field notes were read and the pages numbered. Each page was coded manually using the question ‘what concept is this data an instance of’ so that any assertions to be made could be grounded in the data [Citation22]. Concepts were identified and short notes or memos were written for each concept on a piece of paper using the data from the corresponding page. All the pieces of papers that had similar conceptual headings were pulled together under a higher order term or theme, which was discovered by means of the similarity between the concepts. Memos or narrative summaries were then written on the higher order concepts, using the notes under the concepts to illustrate the themes. To provide readers with a vicarious experience of this process and in line with the interpretivist philosophy adopted in this paper, the narrative summary provided in this paper is populated with direct quotations that illustrate the documented meaning and perspectives of the actors in this study [Citation22]. Under the analysis and discussion section, the various themes are related to each other as well as to the findings and the conceptual framework.

3 Results

The results are organised under seven themes: (1) the crop–livestock farming systems; (2) reasons for keeping small ruminants; (3) tethering practices; (4) free-range management practices; (5) the market off-take of small ruminants; (6) the constraints experienced by smallholders in small ruminant production; and, (7) the institutional underpinnings of the constraints.

3.1 Overview of crop–livestock farming systems

The population, households and their sizes in the five communities studied are described in .

Table 1 Population, households (hh) and average household size in five selected communities. Source: Ref. [Citation31].

All the inhabitants in our sample have diverse sources of livelihood; for instance, all eleven households interviewed at Tangasie in March 2011 engage both in crop production (during the main season from May to November) and livestock keeping. Six out of the eleven engage in dry season gardening (from December to April); and six out of the eleven also conduct small-scale trading activities (such as buying and selling livestock, selling provisions laid out on tables at weekly markets). Similarly, at Orbili, all nine households interviewed undertake both crop and livestock production; six out of the nine engage in dry season gardening; and five out of the nine engage in trading activities (in this paper most of the concrete examples are drawn from these two communities, where detailed follow-up interviews were conducted).

Various kinds of crops and animals are raised, as shown for Tangasie and Orbili in and . The farming systems characteristically combine mixed cropping and mixed farming. The most common farming systems are the millet/sorghum based farming system, groundnut based farming system, cowpea based farming system, and maize based farming system. In terms of farm structure there are two kinds of farms: compound farms (farms built around the main residence), and bush farms (farms distant from the main residence). The distance from the place of residence to the bush farms typically is about 5 km. Farm sizes range from 0.4 ha to 1.6 ha. Uncropped or marginal lands near the residences are where animals are tethered for grazing during the rainy season.

Table 2 Percentage of households cultivating various crops at Tangasie and Orbili during the 2010 cropping season.

Table 3 Percentage of households keeping various livestock at Tangasie and Orbili in March 2011.

The smallholders in the five communities studied keep several kinds of livestock and poultry, namely, sheep and goats (i.e., small ruminants), pigs, cattle, donkeys, guinea fowls, chickens and turkeys. The average herd or flock sizes for the five major kinds of animals and birds were found to be: small ruminants 20.2; chickens 14.9; pigs 5.3; guinea fowls 4.8; and cattle 1.9. The percentage of households keeping various livestock and poultry at Tangasie and Orbili is shown in .

Six out of the seven smallholders interviewed in one of the communities, Dakyiae, preferred to raise small ruminants to other livestock because small ruminants do not require much investment but are prolific and can be relied on in times of need. One farmer captured the sentiment of his fellows when he said: The goat is easy to keep. It does not require much labour. For instance, you don’t buy grass or leaves; the animals can fend for themselves. An animal production officer in MoFA Tamale explained this preference in these terms: Farmers don’t want to put in any money. At best they give only water. At the end of it, they can get something and still feel comfortable. They don’t invest in it because they pay more attention to crops. It appears that one of the main attractions of small ruminants is their low input requirement.

Most of the farmers keep local West African Dwarf sheep and goats, which are hardy, disease resistant and prolific. The average herd size of small ruminants per household for each of the five communities in 2009 is shown in .

Table 4 Average herd size of small ruminants per household in 2009 in five communities in Lawra and Nadowli Districts. Source: Field interviews 2010.

The average herd size per compound house, for northern Ghana as a whole, ranges from eight to twelve small ruminants [Citation25]. Herd sizes of approximately 44 and 22 were observed at Oribili and Tankyara, respectively. These are the two communities that were beneficiaries of the ARI project interventions from 2003 to 2009. The District Directorate of MoFA has reported that small ruminant numbers doubled under the ARI intervention: from 453 at Oribili and 476 at Tankyara in 2005 to 1076 and 972, respectively, in 2008 [Citation26].

3.2 Reasons for keeping small ruminants

Small ruminants are kept for multiple purposes, including stock of capital, insurance, and for meat to celebrate religious festivals. However, the principal purpose is that smallholders rely on their herd during ‘critical times’. Our respondents recognize three critical periods. First, the occurrence of household food shortages. A farmer at Kumasal said: When I run short of food, I sell [a goat] and use it [the money]. A lecturer in animal production explained that farmers keep small ruminants to fill the food security gap when the household runs short of food. They fill a gap rather than [being kept] as a business. An orientation such that we are going to go beyond this purpose, that is not there. Second, the period related to the cost of farm labour and other inputs. A farmer at Kumasal conceded: I can’t farm without having goats. I can sell one to prepare pito (locally brewed alcohol) for the labour gang. A trader at Babile Market observed: Farmers do sell at this time (June–August) for money for ploughing, seeds and fertilizer. When they harvest and they have food, they don’t have any problem again. So they are compelled to keep the animals for the next season. Unforeseen circumstances, such as a drought or a funeral, constitute the third type of crisis that prompts farmers to rely on small ruminants. As a farmer at Orbili said: During farming when there is drought, we sell [small ruminants] to get income. A farmer at Dakyiae summed the reasons succinctly, as follows: The main purpose of keeping small ruminants is that they are a source of income in hardship.

3.3 Tethering during the rainy season

Two distinct husbandry practices are used: tethering, and leaving the sheep and goats to range freely. These are associated with the seasons: tethering in the rainy season, from May to October, and free-range management in the dry season, from November to April. During the cropping season, which begins in May, small ruminants are tethered, i.e., tied with ropes to a stake placed on uncultivated fields or communal lands, where they graze the sparse vegetation during the day, in order to prevent the animals from grazing on the growing crops. Around noon, most smallholders provide water to the tethered animals. In the evenings the animals are brought back into the house compound or penned for the night. This routine is repeated throughout the cropping season. The main labour input in small ruminant keeping relates to the tethering and watering tasks; these tasks are carried out mainly by women and children.

One of the consequences of tethering is that animals lose weight and become emaciated due to the restricted movement and feeding. Little or no breeding occurs for the duration of the tethering period. The animals that do fall pregnant record high rates of abortion and post-partum kid mortality. The wet conditions suit the growth of pathogens and this is the time when the disease incidence of small ruminants is high. Only a few farmers have adopted alternative strategies to mitigate the negative effects of tethering. Two strategies were observed. One is the provision of supplementary feeding of cultivated leguminous fodder crops. For example, one farmer at Orbili nine years ago had planted half an acre of Stylosanthes hamata, a perennial leguminous fodder crop, and he and his neighbours tethered their animals in this field. Another farmer, at Tangasie, had planted Leucaena leucocephala as live fence around his backyard garden and he cut this for his flock. The second strategy we observed is shepherding if the flock size is large (i.e., over 80 sheep), a task carried out by the elderly household members. Two men, each over 60 years, were observed shepherding their sheep at Orbili. The men explained that the children had to go to school and that the young men – who were endowed with more strength – had to work at the farm and thus the responsibility for herd management was shifted to the relatively weaker elderly men.

3.4 Free-range management during the dry season

The tethering period ends after the harvesting of the field crops in October. During the dry season the animals are released to roam on their own. Most smallholders also do not ensure that their animals are housed in the evenings. Uncontrolled breeding occurs during the free-range period. However, crossbreeds of the local West African Dwarf Sheep (or Djallonke) and the long-legged Sahelian type were maintained in one out of the five communities (i.e., Tankyara). These crossbreeds are the visible outcome of a small ruminant improvement initiative in the Upper West Region that formed part of a project supported by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) from 1996 to 2004 [Citation27]. The six breeding stations in the country formerly focused on the introduction of exotics but during 1992–1993 their breeding policy changed to the improvement of native breeds in order to meet concerns about the loss of valuable genetic traits in the local breeds.

In four out of the five communities bush burning is a common practice even though it leads to loss of biomass for feeding small ruminants during the dry season [Citation4].

Tankyara, where there is a still functioning co-operative (that was started in 1976) is the only community where the farmers have succeeded in implementing measures to prevent bush burning, for which they have won a national award. Tankyara is also the only community where the farmers practise storage of farm by-products such as groundnut vines for supplementary feeding of small ruminants during the dry season. They store the vines on wooden planks under the shade of trees. They also gather, dry and store the fruits of Faidherbia albida trees (known in the local language as Goozie), which is adapted to dry conditions, and use these also as fodder. When queried about these practices, which are unique to Tanyara, the farmers responded that the training by and encouragement from the co-operative society accounted for the difference between their practices and those of others.

In the other four communities most of the smallholders did not make any serious provision for supplementary feeding. The only form of supplementary feeding observed at Tangasie for instance was the leaves that some farmers occasionally cut from Ficus gnaphalocarpa, a tree sometimes planted to provide shade or as a wind break near houses. The general perception amongst our respondents in these four communities was that the food supply for the small ruminants in the dry season was not a problem. A farmer from Dakyiae typified this viewpoint when he observed: Even in the dry season, at that time goats improve, better than during this time [the cropping season] when they become lean because of tethering. It is common knowledge amongst the smallholders and traders alike that small ruminants gain weight during the dry season in northern Ghana.

A few of the smallholders provided water during the dry season for their animals. The animals return to the house in the evenings where they drink and then lie around the compound house during night-time. These farmers employed the provision of water as a strategy that enabled them to monitor herd numbers during the dry season. As one smallholder explained: We provide water so that when one [animal] is not there we will know. Many of those who did not provide water complained about the loss of animals, which went to the river or a dam site to drink and then got stolen or preyed upon by stray dogs.

3.5 Market-related off-take

Most smallholders in the study communities sold their animals directly at the main markets without going via middlemen. The market centres were close-by and could be reached by most of the farmers by bicycle or motor vehicles. The smallholders claimed that they received competitive prices at the market because of their direct access to the traders. The average market-related off-take across the five communities was low: 10.5%. compares the households in the five communities in terms of the pattern of off-take of small ruminants in 2009.

Two motivations for selling small ruminants were recorded. The first was distress sales that occur mostly in the lean season, i.e., June–August after the planting of new fields but before harvest. Distress sales flood the market and consequently the prices are low. As a farmer observed despondently: Everybody is selling so the price is low. Some even have to return with their animals to the house because they are not sold at Babile market. A butcher concurred, saying When supply is high in the market, demand is low and the bargaining price starts low. Hence traders pay a low price. The remuneration was used primarily to buy food. The second motivation was demand-driven sales, i.e., the household sold animals in order to take advantage of high market demand on occasions such as Christmas, Easter or the Ramadan festival. The proceeds from demand-driven sales were used for purchasing zinc roofing sheets or cement for house construction, or to cover the expenses incurred during the festivities. The type of sale thus had two dimensions: the period of sale and the utilization of the income from the sale. From it can be seen that households that engaged in distress sales in all the five communities in 2009 were twice the number of those making demand-driven sales.

However, also reveals that there were two communities where demand-driven sales were relatively high: Dakyiae and Tankyara. In Dakyiae more households were able to produce enough food as a result of an input credit scheme for one acre of maize, provided by ADRA, an NGO. In Tankyara, the co-operative society buys food during the harvesting period from its members and resells this to anyone in the community when needed, with only a modest price mark-up and so the community members are not compelled to sell animals under distress. In the other three communities, on the other hand, about half of the households interviewed had been compelled to sell animals to buy food. For instance, at Oribili in 2009, five out of the ten households interviewed bought food and in 2010, four out of the nine households interviewed bought food (compared with the one out of the eleven household heads interviewed at Tankyara who reported that he had bought food in 2010).

3.6 Technical and labour organizational limitations

The limitations experienced in small ruminant production that subsequently were ranked by farmer groups in each of the five communities, are shown in .

The first ranked in three out of the five communities was water shortages during the dry season. The two communities that chose livestock mortality as the first limitation were located near dams that had been constructed in the 1990s through an IFAD-funded project. The limitation ranked second by respondents in three out of the five communities was high mortality. A subsequent interview in two of these communities (Oribili and Tangasie, i.e., an ARI community and non-ARI community, respectively) confirmed that mortality rates were high in 2010: 63% amongst kids (less than 1 year); 59% amongst lambs (less than 1 year); 47% amongst goats (over 1 year); and 12% amongst sheep (over 1 year). In these communities only a few farmers (i.e., 3 at Oribili and 6 at Tangasie) recorded less than 10% mortality, probably as a result of their special feeding and health care interventions. These rates can be contrasted to the 0.88% and 1.98% for lamb and adult mortality, respectively, that were recorded at the MoFA's Ejura Sheep Breeding Station in the same year. The limitation ranked third is livestock theft. Livestock theft is prevalent especially at Tangasie. Only one farmer, whose house was located on the outskirts of Tangasie town, had succeeded in employing a number of trained dogs to prevent the stealing of his animals.

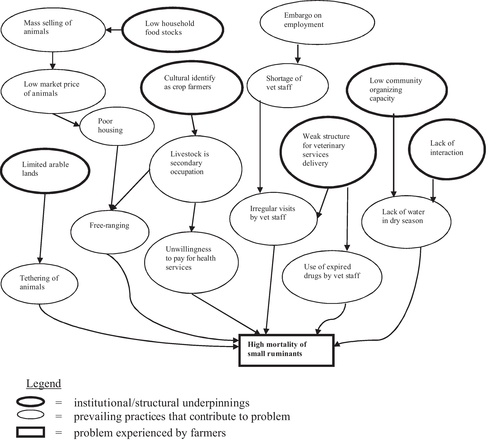

An analysis of the institutional reasons behind the by farmers prioritized constraints is given in and . The institutional underpinnings mainly relate to contextual factors at the local level, or conditions in the higher level institutional regime, that have hindered a transition towards niche developments of a more profitable small ruminant livestock system. provides a summary of the causal analysis of the three top-ranked limitations that was undertaken by sub-groups of stakeholders at the workshops in Lawra and Nadowli Districts.

is a synthesis of the causal analysis output of the two sub-groups that worked on the high mortality of small ruminants at the Lawra and Nadowli workshops. It was selected for presentation in this papers because it reveals all the three types of structural and institutional underpinnings that were identified in the causal analysis exercise: (1) a structural limitation in the availability of arable lands; (2) weak support systems for animal production and health services delivery; and (3) communities’ values, that are skewed towards crop production more than animal husbandry.

The first two were made visible for the first time when the farmers who often crossed the border to Burkina Faso to engage in family and business transactions contrasted in our interviews their own animal production system with that in Burkina Faso (which shares a border with Ghana). One farmer summarized the differences as follows: Land is available in Burkina Faso. They always locate a large place for livestock grazing. We can’t do that – we need a place to farm. Theft is here in Ghana. There people don’t steal. In Burkina Faso, the government has constructed dams that make the place wet and suitable for the growth of grasses at all times.

Another farmer observed that there is more land in Burkina Faso than here. There somebody will rent a place out for rearing animals; here it is not like that. There is much stealing of animals in the dry season here. In the dry season our only source of water is a bore hole.

The issue of limited arable land was a structural constraint that arose partly from the high population density, which for Ghana as a whole was 101.6 persons per square kilometre, compared with 59.4 in Burkina Faso [Citation32]. Control of livestock theft was related to the effectiveness of the state police. In Ghana the general perception was that there was an undue delay in administering justice when theft cases were reported to the police. For instance, in early 2010, 12 cattle were stolen from a farmer at Tangasie and loaded onto a truck, but in the process of transportation the lorry broke down and the driver was arrested. At the time of writing this paper (August 2011), the theft case was still pending at the police station. The traditional authorities also appeared incapable of addressing livestock theft, due to kinship relations. The Regent (or substitute chief) at Tangasie narrated his personal experience as follows: Recently, some of the [five] goats that were stolen were mine. When some inhabitants apprehended the thieves, I took back my [two] animals and left the boys [the two thieves] on their own. Now that I am a Regent if I take any action [against the boys] they [the community] will blame me. I have said that anybody who catches a thief should not bring the case to me. In every community there is a taboo. Where the taboo system does not work, that is when you have a theft problem……. It was Balu's cattle that were stolen, and every month he goes to the police to complain (Tangasie, 12.04.201).

The Burkina Faso police appeared to be more responsive in addressing the social problem of theft. For instance, in early May 2011, livestock traders from the Lawra District were attacked by armed robbers when the traders were attending a weekly market in Burkina Faso. Since then the Burkina Faso authorities have deployed the police to patrol the roads on their side of the border during market days but no similar action has been taken in Ghana.

There also is weak support for animal production and health services delivery in Ghana. As an informant at Tankyara said: We don’t get veterinary people to come and vaccinate. At present there are about three veterinary personnel in the whole district. They are not monitored to ensure that they deliver animal health services. A farmer at Kumasal observed: No regular vaccination is done since the retirement of the last veterinary officer, Mr. Sampa. Now no one comes here. When there were many veterinary officers here, our animals don’t die. Comments such as these were repeated during the institutional analysis workshop. The participants’ analysis indicated that since the decentralization of MoFA services in 1998, the control of resources for the delivery of animal production and health services has been shifted from the district animal production and veterinary officers to the district director. The consequences include a reduction in the supervision of veterinary field staff and a lowering in the coverage and quality of their services to smallholder farming communities.

Routine vaccination against Peste Des Petits Ruminants (PPRs) that could contribute to the control of small ruminant mortality is hampered by the ineffective organization of the veterinary services. For example, during the 2011 cropping season (June–August) when the animals were tethered and therefore most farmers could assemble their small ruminants for vaccination, there was no vaccine available for PPR in Ghana. The stock of PPR vaccines expired in June 2011 and apparently no provision was made by the Veterinary Services Directorate of MoFA for restocking. Recently, a national newspaper, the Daily Graphic of 19 August 2011 [Citation33], reported that imported PPR vaccines, worth thousands of euros, had expired in August 2008 and 2009 and the MoFA was summoned to explain the circumstances to a Parliamentary Commission. Meanwhile, the farmers interviewed in this study indicated that the over 50% mortality rate amongst their small ruminants in 2009 and 2010 resulted from pneumonia and diarrhoea (i.e., symptoms indicative of the fact that PPR vaccination had not been carried out). Recently, three out of the six experimental goats purchased at Tangasie market in August 2011 for an on-farm experiment in this study died within three weeks of acquisition, from pneumonia according to the post-mortem report of the principal veterinary officer for the area.

The third institutional underpinning of the constraints experienced by farmers in the small ruminant production system relates to community values and norms. The interviews indicated that all the farmers in all five communities valued crop production more than animal husbandry. For example, a farmer at Dakyiae kept two bullocks for ploughing and 28 small ruminants (eight sheep and 20 goats). He said that every year he spent money on treatment of only the cattle to prevent illness and ensure that they work hard. However, he did not spend money on the health of the small ruminants. Another farmer at Kumasal concurred with this view, saying that Many people don’t pay to treat animals. They think that government subsidy should cater for animal treatment. They also reason that humans get sick and go to hospital, so why should animals not go to hospital. Another informant related the low value his community placed on small ruminants (compared with crop production) to the difference in livestock production systems between Ghana and Burkina Faso. He observed that The difference between Ghana and Burkina Faso is cultural – this is our way of life – crop farming is our main occupation whereas livestock is an auxiliary activity. Many of the farmers interviewed repeated the phrase that In Burkina Faso, livestock is their main activity.

The high value placed on crop production compared with animal husbandry is reflected also in the low adoption of fodder technologies. From 2003 to 2009 ARI promoted the cultivation of Cajanus cajan as fodder banks in two of the communities (i.e., Orbili and Tankyara) as part of a small ruminant improvement project. In the first year of the Cajanus experiment the project ploughed the fields and provided Cajanus seeds to selected farmers. The majority of the beneficiary farmers did not plant the seeds; and out of those who planted the seeds, many failed to harvest the fodder [Citation26]. On the other hand, a number of farmers belonging to the Wala ethnic group (who trace their origin to the Fulanis in Mali who are noted for cattle herding) have adopted Cajanus fodder bank cultivation under a project co-ordinated by MoFA during the same period.

4 Discussion

4.1 The interrelationship between technical and institutional constraints: going beyond optimizing markets

Our analysis indicates that constraints related to technical, infrastructural, institutional, interactional, and capability factors are strongly co-related and serve to lock-in the current small ruminant production system in Ghana to existing practices. Our analysis suggests in addition that there is a clear relationship between the constraints experienced by small ruminant producers at the local organizational and institutional conditions and the higher-level ones. Such a relationship has been reported also in other areas [Citation3,Citation9]. However, Udo et al. [Citation2], van Rooyen and Homann-Kee Tui [Citation3], and Kocho et al. [Citation5] highlight the need to change the higher level constraints in the sphere of market access before local level innovation can occur. By applying the innovation systems failure framework our study was able to highlight that simultaneous investments are needed in related sectors, such as in improving the organization of water management, re-organizing veterinary service delivery, and improving law enforcement.

In our study the prioritized local level constraints were water shortages, high livestock mortality and theft. The corresponding institutional limitations include the weak interaction between community and district and national level organizations for water provision, the weak organizational structure for animal health delivery, and weak traditional and formal delivery of justice. A number of social mechanisms or processes link the local constraints to the higher-level institutional settings. For example, with regard to water shortages during the dry season, community members have failed to organize contributions to provide their own water supply, or made demands as a collective interest on the district assembly and other politicians. In the case of animal health services delivery, the few farmers who could afford to pay for the services still were not getting any service because of inadequacies in the veterinary technical service and because they did not have the clout to advocate or lobby the central government to lift the ban on employment of new veterinary field staff. On the other hand, the available veterinary technical officers lamented that most farmers appear unwilling to pay for services rendered. With regard to livestock theft, the smallholder farmers who become victims have to make repeated visits to the police station yet justice is not delivered.

We argue on the basis of our findings and analysis that what needs to change is the existing pattern of interaction, in the broadest sense. Numerous small-ruminant system optimization studies similarly suggest changes in relationships [Citation3,Citation5,Citation9] at regime level in order to relax lower level constraints but in recent years they have tended to focus one-sidedly on market relationships. Our study indicates a need for a more systemic change.

4.2 Understanding the rationale that holds small ruminant production systems below the optimum

In the prevailing high-risk environment and the numerous constraints identified in this study, most smallholders seek to achieve a livelihood from multiple sources and by means of low input-sufficient volume small ruminant production in order to meet their needs whenever the occasion demands. Only a few individuals in four out of the five communities (i.e., Orbili, Kumalsa, Tangasie, Dakyiae), and the co-operative members in Tankyara community, had developed successful strategies for improved small ruminant husbandry that enabled them to take advantage of the periods of high market demand. For the majority of the smallholders higher input, market-oriented is not seen as a viable option.

Consequently, the investment of smallholders’ resources in terms of capital and labour is skewed towards crop production rather than livestock rearing. Yet crop production is apparently co-dependent on the income from small ruminants. This finding is consistent with an earlier observation made by the Animal Research Institute of Ghana that smallholders in the Lawra area are guided by the principle of minimum investment in livestock but optimum investment in crop production [Citation4]. The minimum investment principle is also consistent with the numerous studies that indicate that the production decisions of farmers in semi-arid Sub-Saharan Africa are strongly based on risk avoidance rather than maximization of returns [Citation3,Citation34,Citation35]. The keeping of large numbers of livestock is an insurance against climatic risks and uncertainties. In the study area the average numbers of small ruminants kept by one person is small but this totals to a higher number at community levels. The skewed investment in crop production as against animal husbandry also is related to the communities’ own perceptions of their identity as crop farmers. The relationship between self-image and livelihood strategies has been found also elsewhere [Citation36].

A strategy of risk avoidance rather than return maximization, when coupled to a normative rule that values crop production above animal husbandry, poses a challenge to those desirous of stimulating market-driven production of small ruminants in the study communities. It also brings into question the contemporary push towards market integration of smallholders into value chains, seemingly irrespective of socio-cultural and other contextual factors [Citation3,Citation37]. Recent research indicates that there almost always exist several viable pathways for developing a farming system, even under homogeneous conditions [Citation38,Citation39].

4.3 Capitalizing upon diversity and ‘positive deviants’

The assertion that there is a low probability that market production of small ruminants might emerge spontaneously is consistent with innovation systems studies that indicate that niche developments by smallholders and other actors are unlikely unless there are changes in the institutional arrangements in the broader environment in which smallholders and their production systems are embedded [Citation3,Citation9,Citation16]. On the other hand, our study suggests that local actors in these conditions indeed may produce novelties, such as the practice of supplementary feeding and non-burning of bush at Tankyara, the Leucaena used as live fencing by a farmer at Tangasie, the half an acre of Stylosanthes pasture introduced by a farmer at Oribili, the low small ruminant mortality achieved by a few farmers at Oribili and Tangasie, as well as the demand-driven sales of small ruminants by a few of the households at Tankyara and Dakyiae. Tankyara stands out in a number of ways in this list of novelties. The adoption of supplementary feeding by the co-operative members indicates that the principle of minimum investment in livestock can be relaxed. The community itself attributes this to the organizing role of their co-operative society. However, they also acknowledge that they continue to experience water shortages and high livestock mortality at levels comparable with the other communities. The participants in the stakeholder workshop indicated that the institutional reasons underlying the persistence of such constraints are positioned at levels higher than the community level. To summarize, the Tankyara case illustrates that there is a role for community-level social arrangements in addressing certain institutional constraints but also indicates that institutional limitations inter-acting at multiple levels of social organization can lock the small ruminant system into low performance.

There are two important implications to be derived from our observation of farmers who act as positive deviants [Citation10] and who innovate ‘below the radar’ [Citation40]. One implication is that the study of how positive deviants succeed in introducing change and of the strategies they employ to change relationships in their environment in favour of the realization of their innovative practices, could be the basis of interventions that might prove effective for many other farmers. Understanding how they durably embed their novelties in social arrangements (following [Citation11] and [Citation14]) to overcome the institutional constraints to which also the other farmers are exposed, might open up new starting points for development. The other implication is that intervention strategies need to go beyond the farm level. A number of recent studies make the case for innovation platforms (called ‘innovation and concertation groups’ or CIGs in the COS–SIS programme) to foster the emergence of novelties and associated changes in mainstream practices so as to open up niches for transformational change [Citation3,Citation9], and to relax constraints embedded in institutional regimes [Citation16,Citation35]. The relevance of our findings to the innovation platform concept is that CIG stakeholders should allow for diversity in development pathways (following [Citation41]), and not be too strongly influenced by a pre-analytic preference for market-based solutions and technology packages delivered by research organizations.

4.4 Reflections on the methodology

The main research question posed in this study focused on the institutions that hinder innovation and the market participation of smallholder small ruminant producers. In the course of writing the paper it became evident that an equally important question relates to what the smallholders themselves might do to address the constraints and the implications their problem-solving strategies might have for interventions by development organizations and services. In retrospect, an asset-based approach like a positive deviants enquiry [Citation42] might have offered additional insight.

Another issue is that one of the six communities initially selected for the study was not included because of time constraints. However, this is unlikely to have affected the results because the explorative and interpretivist case study design [Citation22] seeks to understand the diversity of the perspectives of the actors rather than to generalize the results of a statistical study to a broader population.

An additional source of bias is that only six out of the 53 farmers interviewed in the five communities were women. Tradition demands that the household head or the landlord receives visitors and communicates their mission and deliberations to the rest of the household and the assets of wives and children belong to the household head or landlord. When our male respondents were asked about who the real owners of the sheep and goats were, many seemed to think the question was irrelevant or they became irritated. The exploration of small ruminant production in future research would need to include more women respondents and should entail study of the gendered nature of the social organization of small ruminant ownership.

5 Conclusions

This study shows that crop production is co-dependent on small ruminant production and marketing. The main constraints experienced by the smallholders are water shortages during the dry season, high ruminant mortality rates, and the theft of small ruminants. The constraints persist because of institutional and structural factors interacting at a range of levels and they block further developments of the majority of the smallholders. The study indicates that in the harsh conditions in which they live the smallholders seek resilience through diversifying their sources of livelihood, by low-input investment in small ruminant production, and by keeping their animals as a capital stock and insurance. However, a few positive deviants have developed novel practices that enable them to overcome some of the constraints and to engage in market-oriented production of small ruminants. These novelties could provide the basis for diverse development pathways that open up a range of possibilities beyond purely market-led or purely technology-led change.

Acknowledgements

The research presented here was conducted within the Convergence of Sciences – Strengthening Innovation Systems Programme (CoS–SIS) funded by the Directorate General of International Co-operation (DGIS) of the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs. We wish to thank Niels Röling and Arnold van Huis for co-ordinating the CoS–SIS Programme. The comments by the other researchers in the food security domain namely Cees Leeuwis, Ben Ahunu, M. Karbo, and Kofi Debrah are gratefully acknowledged.

References

- FAO Responding to the “livestock revolution” Livestock Policy Brief 01, Livestock Information Sector Analysis and Policy Branch, Animal Production and Health Division 2005 FAO Rome

- H.M.J. Udo H.A. Aklilu L.T. Phong I.G.S. Budisatria B.R. Patil T. Samdup B.O. Bebe Impact of intensification of different types of livestock production in smallholder crop–livestock systems Livestock Science 139 2011 22 29

- A. van Rooyen S. Homann-Kee Tui Promoting goat markets and technology development in semi-arid Zimbabwe for food security and income growth Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems 11 2009 1 5

- Animal Research Institute Livestock systems diagnostic survey: Lawra District, Upper West Region, Ghana Technical Report 1999 Animal Research Institute (C.S.I.R.) Accra

- T. Kocho G. Abebe A. Tegegne B. Gebremedhin Marketing value-chain of smallholder sheep and goats in crop–livestock mixed farming system of Alaba, Southern Ethiopia Small Ruminant Research 96 2011 101 105

- APD VSD LPIU GTZ-MoAP V.S.D.V. Animal Production Directorate (APD) Livestock Planning Information Unit (LPIU) Statistical Research Information Directorate (SRID) Market Oriented Agricultural Programme (GTZ-MoAP) Review of MoFA's Activities in Support of Livestock Development in Ghana 2009 Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA) Accra

- E.N.A. Dormon A. van Huis C. Leeuwis D. Obeng-Ofori O. Sakyi-Dawson Causes of low productivity of cocoa in Ghana: farmers’ perspectives and insights from research and the socio-political establishment NJAS – Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 52 2004 237 259

- S. Adjei-Nsiah C. Leeuwis K.E. Giller O. Sakyi-Dawson J. Cobbina T.W. Kuyper M. Abekoe W. van der Werf Land tenure and differential soil fertility management practices among native and migrant farmers in Wenchi, Ghana: implications for interdisciplinary action research NJAS – Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 52 2004 331 348

- A. Hall R.V. Sulaiman P. Bezkorowajnyj Reframing Technical Change: Livestock Fodder Scarcity Revisited as Innovation Capacity Scarcity 2007 ILRI, UNU-MERIT, ICRISAT, IITA and SLP-CGIAR

- F.W. Geels J. Schot Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways Research Policy 36 2007 399 417

- C.M.O. Ochieng Development through positive deviance and its implications for economic policy making and public administration in Africa: the case of Kenyan Agricultural Development, 1930–2005 World Development 35 2007 454 479

- P. Anandajayasekeram, B. Gebremedhin, Integrating innovation systems perspective and value chain analysis in agricultural research for development: implications and challenges, in: Working Paper No. 16, Improving Productivity and Market Success of Ethiopian Farmers Project (IPMS), International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2009.

- D.C. North Understanding the Process of Economic Change 2005 Princeton University Press Princeton

- L. Klerkx A. Hall C. Leeuwis Strengthening agricultural innovation capacity: are innovation brokers the answer? International Journal of Agricultural Resources, Governance and Ecology 8 2009 409 438

- S.C. Hung R. Whittington Agency in national innovation systems: Institutional entrepreneurship and the professionalization of Taiwanese IT Research Policy 40 2011 526 538

- L. Klerkx N. Aarts C. Leeuwis Adaptive management in agricultural innovation systems: the interactions between innovation networks and their environment Agricultural Systems 103 2010 390 400

- R. Klein Woolthuis M. Lankhuizen V. Gilsing A system failure framework for innovation policy design Technovation 25 2005 609 619

- B. van Mierlo M. Arkesteijn C. Leeuwis Enhancing the reflexivity of system innovation projects with system analyses American Journal of Evaluation 31 2010 143 161

- E. Dormon K.A. Debrah S. Adjei-Nsiah O. Sakyi-Dawson Opportunities for enhancing food security in Ghana: a case study of the Nadowli and Sisssala West Districts of the Upper West Region of Ghana Convergence of Sciences Project 2010 Wageningen University

- W. Quaye Food security situation in northern Ghana, coping strategies and related constraints African Journal of Agricultural Research 3 2008 334 342

- K. Amankwah Summary of findings from scoping study on food security domain in Northern Ghana Convergence of Sciences – Strengthening Innovation Systems (CoS–SIS) Project 2009 Wageningen University Wageningen, The Netherlands

- F. Erickson Qualitative methods in research on teaching M. Wittrock Handbook of Research on Teaching 1986 Macmillan New York 119 161

- D. Silverman Doing Qualitative Research: A Practical Handbook 2000 Sage Thousand Oaks, CA

- R.K. Yin Case Study Research: Design and Methods 2003 Sage Publications London

- P.B. Atengdem A.B. Dery Development of transitions of farming systems in Northern Ghana: a historical perspective Northern Ghana LEISA Working Group (NGLWG) 1997 ACDEP Tamale, Ghana

- O.A. Ojingo Presentation of Reports on the CIDA/CSIR/ARI/MOFA Small Ruminant Farmer Groups, Lawra district, November 2008 2008 MoFA, District Directorate of Agriculture Lawra

- UWADEP Upper West Agricultural Development Project (UWADEP): Mid-term Review Report 2000 Regional Directorate, Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA) Wa, Ghana

- P.R. Gildemacher W. Kaguongo O. Ortiz A. Tesfaye G. Woldegiorgis W.W. Wagoire R. Kakuhenzire P.M. Kinyae M. Nyongesa P.C. Struik C. Leeuwis Improving potato production in Kenya, Uganda and Ethiopia: a system diagnosis Potato Research 52 2009 173 205

- C. Leeuwis Lecture Notes: Innovation Management and Cross-disciplinary Design (COM 21306) 2009 Sub-department Communication Science, Wageningen University Wageningen

- G.W. Ryan H.R. Bernard Techniques to identify themes Field Methods 15 2003 85 109

- Statistical Service, 2000 Population & Housing Census of Ghana, The Gazetteer Vol. II, III, IV, Accra, Ghana, 2005.

- Worldatlas, Countries of the world, 2010.

- E. Adu-Gyamerah M. Donkor PAC Orders MoFA to Probe the Whereabouts of Animal Vaccines 2011 Daily Graphic Communications Group Ltd. Accra, Ghana

- J.P. Hella N.S. Mdoe G. van Huylenbroeck L. D’Haese P. Chilonda Characterization of smallholders’ livestock production and marketing strategies in semi-arid areas of Tanzania Outlook on Agriculture 30 2001 267 274

- P. Kristjanson R.S. Reid N. Dickson W.C. Clark D. Rommey R. Puskur S. Macmillan D. Grace Linking international agricultural research knowledge with action for sustainable development Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 9 2009 5047 5052

- T.A. Crane C. Roncoli G. Hoogenboom Adaptation to climate change and climate variability: the importance of understanding agriculture as performance NJAS – Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 57 2011 179 185

- J. Dixon A. Gulliver D. Gibbon Farming Systems and Poverty: Improving Livelihoods in a Changing World 2001 FAO/World Bank Rome/Washington, DC

- C. Leeuwis Communication for Rural Innovation: Rethinking Agricultural Extension 2004 Blackwell Oxford

- J.D. van der Ploeg Labour, Markets and Agricultural Production 1990 Westview Press Boulder

- R. Kaplinsky Schumacher meets schumpeter: appropriate technology below the radar Research Policy 40 2011 193 203

- S. Brooks M. Loevinsohn Shaping agricultural innovation systems responsive to food insecurity and climate change Natural Resources Forum 35 2011 185 200

- K.A. Dearden L.N. Quan M. Do D.R. Marsh D.G. Schroeder H. Pachon T.T. Lang What influeces health behavior? Learning from caregivers of young children in Viet Nam Food and Nutrition Bulletin 23 2002 117 127