Abstract

The incorporation of women and their associations into international markets and value chains is proposed increasingly as a development pathway in Sub-Saharan Africa. The underlying assumption is that exclusion of individual women from groups specialized in supplying a single international niche market is the main obstacle to their development. Intervention under this assumption focuses on linking women groups to international business and development organizations (NGOs). To validate this pre-analytical choice, we conducted a case study of a community-level co-operative of women in Mali (COPROKAZAN, Zantiébougou) that collects shea kernels from producers and processes them into butter and then trades the shea butter for the export market. The choices made in this co-operative are exemplary for other women Malian co-operatives involved in the production of shea butter. The strategic direction taken by the co-operative results from developmental interventions that encourage exclusive reliance on the links between the women co-operatives and niche markets in the international cosmetics industry. The case study shifted attention to the capacity of the women co-operatives to link their handling of fluctuations in supply to opportunities in a range of markets. We found that this in turn also opened new opportunities to a growing number of non-members. We then applied concepts drawn from the research literature on shea in West Africa, market fragmentation, competition, and path dependency to reframe our research focus, to examine how the co-operative in fact navigated this more complex development pathway through co-ordination at group and sector level. The study concludes that a focus on the provision and use of working capital, a strategic priority identified within the studied co-operative, opens new perspectives on what types of institutional arrangements enable the inclusion of a larger number of women in the sourcing of kernels.

1 Introduction

Approximately 80% of the Malian population lives in rural areas. Rainfall-dependent agriculture and livestock husbandry are the main sources of income for people working under these risk-prone agro-ecological conditions. Government and development organizations have explored ways to diversify rural incomes: the shea tree (Vitellaria paradoxa), a native wild species, has been identified as offering strong potential for income diversification. The collection, processing and commercialization of shea nuts are almost exclusively under the control of women [Citation1]. The shea sector in Mali falls under the responsibility of the Ministry for Women's Promotion. However, very few successful attempts to domesticate the tree have been reported. A more promising strategy appears to be selective enrichment in cultivated fields, where tree densities can be 3–5 times higher than in fallows, in combination with selection for trees with desirable traits in the fruits and nuts, leading to the purposeful creation of parklands dominated by the shea tree [Citation2].

The fruits of the shea tree contain an edible pulp that can be used as a snack, especially during the hungry period, the period at the beginning of the rainy season when food reserves run low and cereal crops have just been sown. However, its main product is the nut. After shelling the nut, the kernel can be processed to provide a fat known as shea butter or beurre de karité. Shea butter is an important ingredient of local diets and serves household needs as a vegetable fat, for example in combination with millet as a frying medium or added to porridge, and for moisturizers and soap [Citation3]. There is a huge domestic market for shea butter, and more than 90% of it is consumed domestically and traded in local markets. Mali's share of international trade is less than 10% [Citation4], selling into markets that range from regional trade networks operating throughout West Africa to specialized export trade routes to Europe and North America. For instance, the European chocolate industry, in particular after the European Union allowed various vegetable fats to be used as cocoa butter equivalent, exerts a strong demand for shea kernels on local markets, operating through extensive agent networks [Citation5]. The actors in this value chain are well co-ordinated, dominated by a few monopolies, and to a large extent under male control [Citation6]. The international cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries provide niche markets for ‘improved’ shea butter of low acidity. International demand is increasing and in response the organization of trade is being stimulated by numerous international development organizations. In a number of cases, market organization along the value chain has been linked to Fair Trade labels [Citation7]. However, this market remains strongly fragmented, a point that is explored in more detail later in this paper.

Mali is the world's second largest producer of shea fruits after Nigeria [Citation3]. It is estimated that there are around 20 million shea trees in Mali. The annual production of shea kernels is about 100,000 metric tons, representing only 50% of the country's production potential [Citation8]. Shea nut is one of the commodity chains that are receiving priority from government, donor agencies and development organizations, including national and especially international non-government agencies (NGOs). The gathering of the shea nuts alone is estimated to contribute 8.5% to agricultural production [Citation8]. Currently, over 500,000 people are estimated to work in Mali's shea sector, most of whom are rural women who collect, process and sell kernels and butter. The ripening of shea fruits occurs during the labour-intensive rainy season, so women usually store the nuts for processing at a later date when their labour-time is less constrained. However, inadequate storage facilities reduce the quality of the shea butter.

The Malian support strategy (by the government and development organizations) to the shea sub-sector has a strong focus on building rural women organizational capacity to process higher volumes of good quality shea kernels and butter for high-value export markets. In practice this strategy neglects the development of domestic consumption and local high-value export markets [Citation6]. Currently, the domestic and international chains are not connected [Citation3]. The Malian strategy resembles those of other West African countries [Citation9,Citation10] in that it favours the formation of direct linkages between women groups and niche cosmetics markets by investing in upgrading the groups’ capacities to comply with supply contracts and quality control assurance in these markets. The emphasis on global niche markets, driven by externally conceptualized and project-based interventions, creates path dependencies and risks marginalizing low-income women whose livelihoods are partly dependent on the collection of shea nuts. It also fails to build on the skills and networks embedded in local trade [Citation11].

This paper focuses on co-related institutional issues in the development of markets for shea nut, and in the development of capacity, at various levels, to meet the emergent market demand. It is based on a diagnostic study that zooms in on how shea nut co-operatives, mostly with women members, navigate in this situation, evidenced in the choices they have made over time. It first presents the co-operative COPROKAZAN (La Cooperative des Productrices de Beurre de Karité de Zantiébougou) as a case study, in order to reveal its strategic choices with respect to shea nut collection and processing as well as the linkages maintained with supporting agencies. Three comparable cases are examined of similar co-operatives engaged in the making of improved butter for external markets. Next, we briefly report on the relation among COPROKAZAN, support organizations, and the still underdeveloped sector-based umbrella organization or inter-profession known as SIDO [Citation12]. In the discussion section we build on middle-range theorizing about development strategies deployed in the West African shea sector in order to refine our original diagnosis and underlying assumption. We reconsider this assumption and conceptualize the experimental strategy chosen by COPROKAZAN, namely, accessing working capital (fond de roulement) from external institutes in order to scale up its operations, as an endeavor to create more space and influence in the co-operative's navigation of opportunity in the face of supply fluctuations. Our study suggests that capacity of the co-operative to tailor problem solving to its relationships with its members and non-members in the locality is connected to the development of co-ordination at higher levels. We conclude that previous choices made in shea nut development policy and practice, particularly the emphasis on single market export-oriented arrangements, may constrain such capacity development.

2 Research location and methods

Data collection took place throughout 2010 and 2011, mainly at Zantiébougou in the Bougouni prefecture, 187 km from Bamako, and also from Sikasso, on the road (RN7) that connects the two cities and where the co-operative COPROKAZAN is located. Recently, the RN7 has been much improved, increasing opportunities for trade. The constituency of Zantiébougou encompasses 42 villages and covers 1500 km2. According to the 1998 census, the population totals 31,316 inhabitants of whom 51% are female. The population is composed mainly of Bambara and Peulh ethnic groups. Agriculture, animal husbandry and woodland exploitation are the major economic activities. Agriculture revolves around cereal crops, grown for subsistence, and cotton, grown as the main cash crop. Shea nut is the main source of income for women [Citation13].

COPROKAZAN was selected because it is the first community-based organization of women that received external support. It has pioneered joint learning and action for adding value and trading shea products and has become relatively independent of the supporting organizations. The co-operative features very prominently in the national and international media. The number of Google hits for this co-operative is higher (3000; accessed December, 2011) than for the three other co-operatives treated in this study (less than 600 hits each). COPROKAZAN has also played a major role in the revival of the inter-organizational network (SIDO): COPROKAZAN's president was chosen as the first president of SIDO.

Three comparable community-based organizations, COOPROKASI (at Siby, 35 km from Bamako), Siyiriwa and ULPK (both in Dioila, 160 km from Bamako) were selected purposefully in order to compare and contrast the ways in which access to support and the negotiated relationships with support agencies were arranged.

Data from the support agencies in the five villages (20 in total) were collected through 25 group meetings focusing on the shea nut value chain, involving women shea nut collectors and processors as well as representatives of the support agencies, 28 key informant interviews with co-operative members, professionals working in the sector, and traders, direct observation, and the gathering of secondary data from project documents, reports and literature. The interviews were semi-structured, guided by checklists in order to cover the same issues with each respondent. The interviews focused on the respondent's experience with and perceptions of the organization of shea butter making and trade activities. Interviews were conducted also with seven former members of the co-operatives who had chosen to leave the organization. In addition, over a four-month period, all meetings within the co-operatives and between the co-operatives and support agencies, as well as visits by women groups from shea producing areas not covered by the study, were attended and monitored.

3 Results

3.1 COPROKAZAN Zantiébougou – organizational history and strategic choices

The organizational history of COPORKAZAN started in one village, Falaba, in 1991. This village was the home of the former president of a national NGO, AMPJ (Association Malienne Pour la Promotion des Jeunes). She set up AMPJ between 1991 and 1993 when she began to organize women in her home village into groups. From 1994 to 1995, AMPJ helped to strengthen the technical capacity of the women to make improved shea butter, because the pre-treatment of the shea nuts and processing practices affect smell and colour. In March 1995, a team of women from a newly created village group and AMPJ representatives visited a shea project in Burkina Faso, supported by SNV (a Netherlands development organization) in order to learn more about the recommended practices for improving the quality of shea butter [Citation14]. In 1995, the women group in Falaba started joint trading of shea butter. AMPJ played a role in modifying the terms of trade of the shea products sold by the group. In our interviews, the informants referred to ‘lopsided terms of trade’ to indicate that the benefits went to the traders rather than to the women who bear the burden of collecting and processing the nuts. One key informant blamed the traders for opportunistic behavior, manifest in their unwillingness to remunerate the women according to quality of the butter. It was the traders who set the prices for undifferentiated shea kernels and butter that the women sold at weekly village markets. This respondent recalled that the price in 1992 was 80 FCFA (€ 0.12) per kg of butter, when butter was sold in Bamako and other cities at 250 FCFA (€ 0.38) per kg.

AMPJ subsequently provided the women in Falaba with a storehouse, a mill and working capital amounting to 300,000 FCFA (€ 458.02). The latter was used to purchase butter from women members of the village group at 125 FCFA (€ 0.19) per kg during the harvest season, instead of them selling the butter to traders at a lower price. The group then stored the butter to sell it at a higher price (250 FCFA [€ 0.38] per kg) later in the season during the period of low supply.

The change in the terms of trade released funds at community level and the group was able to make a substantial contribution to the building of a maternity hospital in their village. They also bought a donkey-driven cart and opened an account at a bank with an initial deposit of 500,000 FCFA (€ 763.36). In 1996, these events encouraged women groups from a neighbouring village (Sirakoro) also to link to AMPJ and they obtained a working capital of 200,000 FCFA (€ 305.34) to replicate the measures taken in Falaba. The network subsequently expanded to four other villages in 1998 and to a total of 15 in 1999. In 2000 the village-based women groups federated into an apex organization UGFZ (l’ Union des Groupements Féminins de Zantiébougou). In this expansion phase all married women in the 15 villages automatically became members of UGFZ. This open membership policy made it difficult to find a way to allocate fairly the working capital for purchasing the members’ butter.

AMPJ then succeeded in obtaining financial support from the US-based African Development Fund, which funded further equipment purchase, the development of logistical infrastructure and additional working capital of 5 million FCFA (€ 7633.59). The working capital was distributed in portions of 300,000 FCFA (€ 458.02) in each of the 15 villages for purchasing butter from the members. However, quality control proved difficult to ensure, according to the key informants. The open membership policy did not give rise to a procedure for giving feedback on quality issues to the individual butter processors. Consequently, the butter traded to Bamako was repeatedly returned for lack of consistency in smell and colour.

In 2004, AMPJ sought assistance from a volunteer working for a Canadian organization (CCI – Canadian Crossroads International), who was specialized in organizational development, to diagnose how the activities of UGFZ might be improved. The key problem that came to light was related to the way in which women could become members of UGFZ without conditions or qualification. The diagnosis also showed that most of the women felt alienated from the apex organization UGFZ. This feeling was linked by the women and the volunteer to the information asymmetry between the central unit of UGFZ and the groups at village level. The diagnoses further indicated that the village-level groups considered the central level to be privileged as far as the benefits of UGFZ membership were concerned.

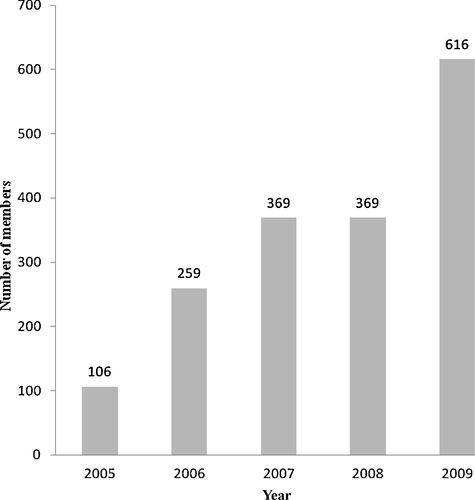

The proposed solution was to modify the organizational structure and transform UGFZ into a co-operative. The co-operative became known as COPROKAZAN, which was registered in 2005. COPROKAZAN demanded that new members pay 1000 FCFA (€ 1.53) as an entry fee and 1800 FCFA (€ 2.75) as an annual contribution to the working capital of the co-operative. The co-operative started with an elected steering committee of seven members, an elected oversight committee of three members, and a general assembly of 106 members. In 2009, it had 616 members, including 8 men, located in 32 villages in the constituency.

One of the first choices COPROKAZAN made was to concentrate the processing of shea nuts at a centralized unit in the vicinity of the co-operative. This generated full-time and part-time jobs for 140 women. Additionally, 6 men were involved in the milling and the physical tasks of loading and unloading the collected kernels. Later on, the co-operative added decentralized processing units located in the villages to its operational structure, thus reducing the costs of the gatherers of the nuts of accessing the processing facilities and thereby allowing more women to earn income. The management of the co-operative also began to realize that it needed to find a way to aggregate enough volume to influence the terms of trade. The management thus opted to scale up the reach of the co-operative to all 42 villages in the constituency of Zantiébougou. This decision had knock-on effects: entry restrictions were imposed on applicants from the already associated villages, and unrestricted entry was allowed for applicants from new villages, so as to spread membership opportunity throughout the constituency. As a member of the steering committee related: As we aim to affect the market of shea products, we do not intend to divide the territory of our constituency by concentrating only in some villages and then leaving the rest of territory to traders. Another steering committee member further explained: Shea productivity fluctuates from year to year but also from one territory to the other. Covering the entire constituency is then perceived as a risk management strategy.

The choices made by the co-operative's management indicate that ensuring sufficient volume was an important element in its strategy to affect the terms of trade by expanding the spatial coverage of its sourcing practices. Initially, the co-operative employed a clerk with a professional history in sourcing cotton, to take in shea kernels during the weekly markets. The kernels then were stored in the villages until needed for processing. The decentralized storage, according to our informants, impacted negatively on quality. Consequently, the co-operative decided to centralize the sourcing of kernels and to appoint a co-operative official to control the quality of the kernels at the point of delivery. The clerk was made responsible for weighing and record-keeping at the co-operative building. He subsequently found it difficult to explain the shift to a centralized intake of kernels and related this shift in practice to a lack of trust in him on the part of the management.

In order to secure a continuous supply of good quality kernels the co-operative decided to guarantee that it would purchase kernels that met the standard at a price higher than the price offered by traders. The differential price and the predictability of the price proved attractive also to non-members and encouraged them to meet the quality standard of the co-operative. Although a non-member could sell to the co-operative only by using the membership identity card of a member, the use of the members’ identity cards was encouraged by the members, because it increased their own bonuses at the end of the buying season. Non-members are reported to have supplied 60% of the collected kernels of the co-operative. Our respondents confirmed that the ability to use the co-operative's working capital in support of this price strategy was a vital asset.

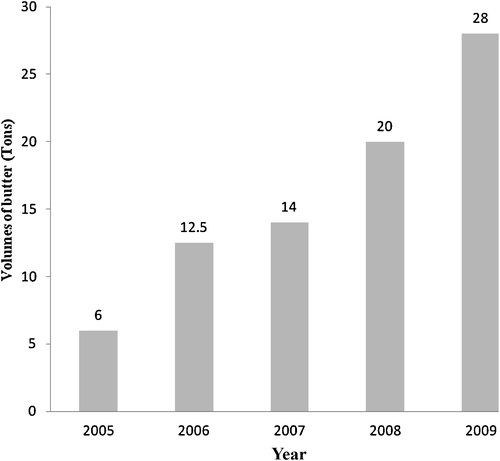

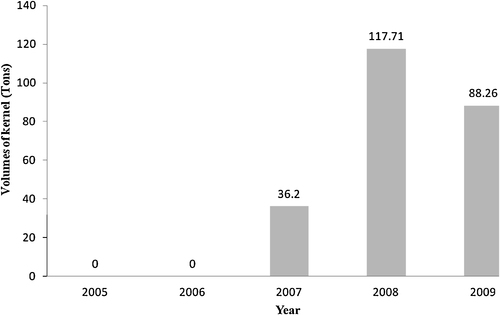

Quantitative data support our respondents’ historical narratives. Membership in the period 2005–2009 rose steadily, except that in 2008 no new members were admitted (). The trend in the supply of kernels shows a more erratic pattern (). Kernel supply strongly increased in 2008 (when no new members were admitted, but non-members’ sales for the first time were allowed through members), and declined in 2009 (when membership strongly increased). Butter production steadily increased over the period 2005–2009 ().

Our informants explained these trends in terms of the co-operative's decision to concentrate on butter production to meet the demand of foreign buyers. The co-operative collected from its members some of the kernels on credit and also allowed the members to pay the annual contribution to the capital of the co-operative in kind (i.e., in kernels). suggest that the volume of collected kernels depends less on the size of the membership as such and more on the inter-play between price, access to processing facilities, and quality. The buying practices of the co-operative in turn were strongly related to the availability of working capital. In 2009 the co-operative encountered cash flow problems and had difficulty in purchasing kernels from non-members because there was insufficient cash available.

3.2 The strategic choices made by three other shea co-operatives

ULPK in Dioila chose to limit the stocking of butter on its own account and to act as broker between the women groups in as large a number of villages as possible and buyers of the shea butter. ULPK collected information on the quantity of butter available at co-operatives in the various villages and then arranged a supply contract with a trader before buying from the co-operatives and selling the butter on to the trader. This kept the price to the women below the premium paid by COPROKAZAN and also resulted in prices that fluctuated from contract to contract. ULPK retained 5% of the total amount of each contract as remuneration for its efforts and to sustain its activities.

The co-operative Siyiriwa (also in Dioila) chose to purchase kernels from its members but to delay processing until a buyer was found for the butter. This meant that the co-operative used most of its working capital to buy the kernels and had received no new revenue until it processed and sold butter in the market. It strongly relied on project funds for financing personnel and operational costs, largely channeled through a public support project funded by UNIDO and implemented by the Ministry for Women's Promotion.

The co-operative in Siby concentrated on the production of soaps and skin care products sold to tourists and into niche export markets. The shea co-operative was initiated by the support of an NGO that initially was involved in supporting women groups producing vegetables and mango fruits. We observed a number of tensions in the relationship between the central units involved in the value-adding activities and in sourcing butter, and the women groups linked to the shea enterprise. The distribution of income between the central units and the women groups, together constituted as a network, according to our respondents lacked transparency. Some of the funds received by the co-operative were allocated to and kept by the central units, which created suspicion at other levels.

The various choices made by the four co-operatives included in our study are summarized in , as these choices relate to the way the co-operatives source, process and trade kernels.

Table 1 Comparison of COPROKAZAN with other three community level organizations. Source: Interviews with steering committees of the four organizations and with representatives of the support agencies.

The co-operatives use a combination of members and non-members for sourcing kernels in sufficient quantities, a finding that is consistent with results reported in other studies that indicate that a majority of the women involved in shea nut collection or processing do not belong to formalized organizations [Citation4]. However, the co-operatives made different choices about what to source, either kernels or butter. The study of COPROKAZAN suggests that the purchase of kernels is more relevant to non-members’ interests and that butter requires more intense management (and hence requires stricter rules regarding membership) in order to ensure quality. The choice to focus on processing activities also takes into consideration the generation of employment. The making of butter generates full-time employment for an exclusive group and part-time employment for a larger group of women, sometimes at a central unit and sometimes in decentralized processing units located in the villages. However, exclusive access to paid labour generates tension. Recognition of the interests of non-employed women appears to be a delicate issue for the co-operatives.

4 Analysis and discussion

4.1 The direction taken in policy and practice in the Malian shea sector

The choices made regarding sourcing, processing and trading of shea kernels and butter by the co-operatives indicate that the co-operatives are trying to balance the aggregation of quantity and securing a level of quality sufficient to negotiate good remuneration in the market. In addition to this strategic balancing of quantity and quality, the co-operatives are balancing the advantages of centralization and decentralization of processing and sourcing.

The choices made on these matters from the start have been inter-twined with the guidance and kinds of support offered by the support agencies. The first women group in Zantiébougou was formed by AMPJ, whose president originated from Zantiébougou. AMPJ subsequently played a brokerage role between the co-operative and the support agencies ().

Table 2 Linkages of COPROKAZAN to support agencies. Source: Interviews with key informant and website of the co-operative (http://www.coprokazan.org/partenaires.htm).

The time line of support projects suggests that NGOs and support projects tend to cluster around already existing successful community organizations and in specific geographical areas. The support agencies in the shea sector also tend to exchange personnel and take over each other's activities. Our key informants in Zantiébougou for instance pointed to a regular exchange of staff between AMPJ and the government-supported Projet d’Appui au Filières Agricoles (PAFA). The US-based African Development Fund started to support the co-operatives in 1999. Canadian partners then began to provide similar support in projects linking the co-operatives to Canadian markets by sending volunteers to assist in organizational development of the value chain. Irrespective of the agency, the orientation of their support remained the development of the value chain to meet the international niche market for shea products. At the same time, the support organizations made an effort to associate their work with other successful organizations. Overall the effect has been to create a path dependency that locks the women groups and co-operatives into effort to gain access to export markets. It was argued by some of our informants that this orientation helps the support agencies to establish and maintain their mandates and legitimacy in their home countries. At the same time it tends to exclude the women and co-operatives from building the capacity and markets of the domestic value chain.

In order to analyse this point further we made an inventory of 25 development interventions in the shea sector, in the regions Bamako, Kayes, Koulikoro, Sikasso, Segou and Mopti on the basis of the list of actors maintained by FNK (Fédération Nationale du Karité) and Projet karité. Our analysis showed that the majority of the interventions combined investments in processing equipment with building organizational capacity to access international markets as the main way to generate income for members. One worked on the provision of micro-credit; another supported the groups in the making of business plans. Some linked the groups specifically to Fair Trade certification and other trade schemes. PAFA for instance provided Fair Trade certification to a selection of organizations as well as enabled the participation of selected groups in trade shows. Our analysis suggests that the dominant underlying assumption is that provision of improved techniques and resources and the facilitation of international market access positively impacts the incomes and livelihoods of co-operative members. We suggest that because the size of the international niche market is still small (and vulnerable to economic crises in these markets), and there is competition among the support agencies for visibility in the development of the shea sector, such path dependency on international trade is risky [Citation7].

One of the main thrusts of the interventions has been to reduce the fragmentation in the shea nut value chain. The CFC (Common Funds for Commodities)–ProKarité project has taken responsibility for implementing a series of co-ordination measures. The project selected as its partners a number of women groups in the areas where the main NGOs were active: Zantiébougou, Dioila, Siby Kolondiéba, and San. A primary objective of the project was to establish regional and international consensus on issues of shea product quality as the basis for enhanced traceability along the supply chain. In addition, the concept of Points Filière Karité (PFK – focal points in the shea nut value chain) was introduced, representing the first attempt at co-ordination among the various actors in the value chain. The PFK were designed to serve as focal points for buyers of quality products and as infrastructural facilities through which shea products of higher quality could find better market opportunities, both nationally and internationally. The initiatives taken by the CFC–ProKarité represent a slow convergence among the diverse interests in building more effective linkages among stakeholders along the value chain [Citation15]. The project ended in 2006 but was followed-up by the creation in 2007 of an inter-organizational network, SIDO, supported by funds left over from the CFC–ProKarité project. SIDO was given by the network members an explicit mandate to enhance connectivity and co-ordination among the actors in the shea sector. Lobbying and advocacy were also included in its mandate, primarily to increase the visibility and labelling of shea products from Mali. Our interviews with key informants in the SIDO network nonetheless indicate that multiple conflicts of interest and obstructions to its operation remain.

The current president of one of the initial PFKs, namely, the co-operative in Zantiébougou, was recently elected president of SIDO. Respondents suggest that her election was related to the influential position of the deceased originator of AMPJ and founder of the co-operative in Zantiébougou, who was also an influential member of the administrative council of the CFC–ProKarité project. Her election to this position tends to confirm that co-ordination efforts remain anchored in community-based organizations that constitute the core of the established development pathway of the shea sector. The fact that this in turn tends to lock decision-making in the hands of a relatively small group of women may hamper further development of concerted action and decision-making.

4.2 Questioning the dominant underlying assumption and consequent strategic choices

The research for this paper started from the assumption that the exclusion of women from co-operatives serving a remunerative international niche market was the major development problem in the Malian shea sector. The case study of the co-operative in Zantiébougou brings into question the pre-analytical assumption. The study shows how the co-operative navigates in its given market and institutional environment. We use the metaphor of navigation because the co-operative is shown to be making capacitated, constrained, collective, and contested choices but does not choose the choices open to them [Citation16]. The choices open to them have been made by the support agencies and they frame the pathway by which the effects of the co-operative are accomplished. The metaphor also allows us to consider the inclusion of women into markets or value chains as a continuous process rather than as an on-off effect [Citation17,Citation18]. Our discussion here links choice making, improvisation and problem solving at local level to the constrained choices resulting from linkages with the rules and routines imposed by the support agencies [Citation19].

The choice to focus on women groups supplying an international niche market has led to a development strategy based on the replication of micro-pilots under the stimulus of the support agencies. The institutional changes induced by this strategy have been detailed in our results and reveal that the problems of fragmentation and competition have been caused – or at least exacerbated – by the strategy. We propose here to shift attention to processes and choices that have surfaced in our study that could enable co-operatives to navigate in and manage contingencies related to the market and the material conditions of their performance and that could achieve a level of co-ordination at national or sector level. In this perspective there is potential for a wider portfolio of choices to be supported and tailored to specific situations and capacities of co-operatives. In particular, we built on (1) the priority given by COPROKAZAN to accessing working capital by linking to an interested finance institute; this created ‘space to navigate’ by ensuring a continuous replenishment of the stock of working capital; and (2), the embryonic co-ordination processes triggered by ProKarité and the inter-organizational network SIDO.

The first issue, of market choice, has been discussed in the literature on the development of the shea sector in West Africa. Already in 1999, Fold and Reenberg [Citation6] noted the neglect of local shea trade. The local market demands shea nuts and butter the whole year round and this pattern of demand would seem to offer some attractive features if income generation is the goal. However, the terms of trade are not considered favuorable, neither by development practitioners, nor by the women members of the co-operative. A major reason is that the temporal variation in supply results in low prices during the harvest season. Poor storage facilities during the times when supply is relatively low (and thus higher prices are likely) resulted in produce of poor quality that was rejected by the market in Bamako. Initially, the options of improving storage, and guaranteeing a consistent supply of butter year-round, did feature in the support agencies’ interventions. However, the increase in the mutual ties between the co-operatives and development organizations led to a gradual shift in their focus, away from the domestic market and towards building an exclusive relationship with buyers in an international niche market in cosmetics or in Fair Trade [Citation5] that appreciated the specific qualities of shea butter and controlled the added value.

Quality improvement has been achieved but the size of the international markets the co-operatives can serve remains limited. In terms of traded volume, the market choice has meant that the co-operatives make little impact on alternative market channels that could absorb much larger volumes, i.e., their efforts have created a specialized value chain that is isolated from the independent agent networks maintained by local traders in the villages. The only export market for kernels that demands substantially larger volumes, the European chocolate industry [Citation5], is controlled by a few dominant players who are largely beyond the span of influence of the co-operatives. Shackleton et al. [Citation11] have observed a comparable trend in non-timber forest products in that the portfolio of development interventions for non-timber forest products emphasizes participation in global value chains on the underlying assumption that the greatest potential to impact poor people's livelihoods is found in these global chains. They characterize the linkage with the export market as driven by externally imposed, project-based interventions and contrast such development strategies with a more pragmatic approach building on local markets that evolve autonomously with little external support, and that utilize domestic actors’ long-standing skills and knowledge in production, processing and trading to meet local, domestic and regional demand for the products offered. In his discussion of export-oriented enterprise development for non-timber forest products, Cunningham [Citation20] emphasizes the importance of organizational structures that source across a wide geographic area and arrange reliability of supply. In terms of development strategies this translates into strategic partnerships that seek to level the playing field in terms of who controls the value-added profits along the value chain. In the case of the shea co-operatives this observation raises the question whether the choice for (and the resulting dependence on) a single market channel allows them to exploit their capacity to ensure a reliable supply of butter and kernels at sufficient scale, and to control the profits.

We do not want to argue in favour of a specific type of market channel. Our discussion intends to show the narrowness of the strategic choices pursued by the co-operatives. We further note that the choice for a niche market constrains the capacity of the co-operatives to diversify and act flexibly in a dynamic market environment. They are now in a position that makes it difficult for them to combine their exclusive linkage to their niche markets with a capacity to negotiate the terms of trade in other markets or to tailor the seasonality of supply to year-round demand. We suggest that this position has been defined and consolidated largely by the support agencies. The co-operatives in our study furthermore have become quite dependent on resources provided by the support agencies.

The processes that have steered the choices made in the network of supporting agencies originate in the initial configuration of relationships among the women groups, co-operatives, NGOs and public agencies in Zantiébougou. Because each support agency tended to build its own identity with and through actors in specific areas or co-operatives, the sector for a long time remained fragmented. Kilby [Citation21] explicitly relates the observed fragmentation to the proliferation of donors and NGOs, each seeking to support small projects with specific groups. A sort of ‘pack mentality’ among these agencies can be seen in the tendency of each to copy what others are doing. Koch et al. [Citation22] point to the related tendency of NGOs to cluster in the same areas where other NGOs are operating; this is clearly evident in the areas where the four co-operatives in our study are located. We further hypothesize that a competitive funding environment encourages NGOs to adopt intervention strategies that create in their home countries visibility for their work, and to initiate projects where the level of attribution is high, such as by working directly with the women groups involved in making improved shea butter [Citation23,Citation24]. Sydow [Citation25] similarly has suggested that the types of solutions that dominate project-led interventions lead to rigid routines that restrict alternative or complementary actions by women groups or sector-based organizations.

It has been argued that an unintended consequence of the emphasis on small projects for which skilled bureaucrats and managers are recruited is that the quality of co-ordination in a sector declines [Citation26]. This in turn may serve to sustain organizational fragmentation among local organizations and amongst actors along a value chain [Citation7]. SIDO's weaknesses and lack of decisive impact can be explained by this phenomenon. Edwards and Hulme [Citation27] report discussions among development practitioners to reveal the difficulty that NGOs experience in interacting with actors and organizations at higher-than-local levels (at least in a developing country). Although in the case of shea exclusive relationships have been created with some of the base organizations and international companies such as The Body Shop or L’Occitane, Edwards’ and Hulme's [Citation27] observation generally still stands. Our analysis and discussion suggests that neither Atack's [Citation28] view that NGOs and the state are complementary agents of development, nor Edwards and Hulme's view that the scale effects of localized interventions are dependent on co-operation with the state, sufficiently describe the processes and relationships we have observed in the Malian shea sector.

Another unintended consequence of NGO proliferation and organizational fragmentation has been examined by Platteau and Gaspart [Citation29], who argue that the dependency of NGOs on community-based organizations makes their interventions vulnerable to capture by local elites. We have shown that the choice of NGOs in the Malian shea sector to focus on a niche market was highly dependent on the performance of those with the capacity to adopt the technical measures needed to meet the quality requirements in the international value chain. We have noted in our case study also that the co-operative in Zantiébougou was started by a member of the local elite who had been employed in the NGO community based in Bamako. Subsequently a small and selective group of community members ruled the choice making processes in the co-operative and employment at the co-operative was open only to a few. This evidence is not strong enough to demonstrate elite capture, although a differentiation between members and non-members is clearly visible. Moreover, the interventions made by the support agencies linked to the co-operatives have depended on a small number of individuals within the larger development community. The pattern of their relationships appears to have discouraged the exploration of other forms of public regulation of the playing field at the level of the shea communities, the value chain, and the sector.

5 Conclusions

This paper critically investigated the assumption that the exclusion of women from processing and trading opportunities related to international niche markets is the key development problem in the Malian shea sector. The international niche market option is projected as a viable alternative to domestic and other international market channels, where the terms of exchange do not favour women groups’ participation. Our analysis and discussion have led to a reframing of the original assumption, to suggest that the capacity of women groups to navigate in a dynamic market environment and to make locality relevant choices is constrained by path dependencies on prior strategic choices and measures that have been determined in large part by the support agencies, and by their growing dependence on externally provided resources. Our diagnosis shifts attention to the processes relating the micro-level performance of women groups to meso-level co-ordination. We conclude that initiatives intended to influence the terms of exchange, and to secure improved performance by the sector as a whole, are not scale neutral. Furthermore, we conclude that the navigation of choice by the women groups in the situation described, and their capacity to influence the terms of exchange, have strong material and spatial dimensions that are constituted in working capital and the management of stocks and supply fluctuations. In further research we propose to examine COPROKAZAN's choices as a natural experiment in order to further unravel the relation between group performance constituted in their material conditions and processes of co-ordination in the enabling environment.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the steering committees of the women organizations as well as the representatives of the support agencies involved in this study. We are grateful to the heads of the study villages and to the women in these communities for participating in the focus group meetings and interviews. We gratefully acknowledge all resource persons who facilitated the fieldwork and participated in formal or informal discussions. Our sincere thanks are also due to both anonymous reviewers for their critical reading of an earlier version of this paper.

References

- J. Carney M. Elias Revealing gendered landscapes: indigenous female knowledge and agroforestry of African shea Canadian Journal of African Studies 40 2006 235 267

- APROMA Etude de la filière karité du Burkina Faso: Volume 1. Rapport principal. Contrat no. 01/DEL/94 1995 Association des Produits À Marché Bamako

- E. Derks F. Lusby Mali shea kernel value chain case study, microREPORT #50 ACDI/VOCA (Accelerated Microenterprise Advancement Project Business Development Services Knowledge and Practice Task Order)Washington, DC(2006)

- F. Lusby E. Derks Shea kernels from Mali: a value chain case study Small Enterprise Development 17 2006 36 46

- D. Greig Shea butter: connecting rural burkinabè women to international markets through fair trade Development in Practice 16 2006 465 475

- N. Fold A. Reenberg In the shadow of the ‘chocolate war’: local marketing of shea nut products around Tenkodogo, Burkina Faso Geografisk Tidsskrift/Danish Journal of Geography 2 1999 113 123

- M. François N. Niculescu Z. Badini M. Diarra Le beurre de karité au Burkina Fasso: entre marché domestique et filières d’exportation Cahiers Agricultures 18 2009 369 375

- Ministère-du-Développment-Rural Shéma Directeur du Secteur du Développement Rural (SDDR) 2001 Ministère du Développment Rural – Cellule de Planification et de Statistique Bamako

- Z. Badini M. Kaboré J.v.d. Mheen-Sluijer S. Vellema Historique de la filière karité au Burkina Faso et des services offerts par les partenaires techniques et financiers aux acteurs, VC4PD Research Paper #11 2011 Wageningen University and Research Centre Wageningen

- Z. Badini M. Kaboré J.v.d. Mheen-Sluijer S. Vellema Le marché du karité et ses évolutions: quel positionnement pour le REKAF, VC4PD Research Paper #12 2011 Wageningen University and Research Centre Wageningen

- S. Shackleton P. Shanley O. Ndoye Invisible but viable: recognising local markets for non-timber forest products International Forestry Review 9 2007 697 712

- A.W. Shepherd J.-J. Cadilhon E. Gálvez Commodity associations: a tool for supply chain development? Agricultural Management, Marketing and Finance Occasional Paper 24FAO, Rome(2009)

- CSA/PROMISAN, Plan de securite alimentaire commune rurale de Zantiébougou, Commissariat à la Sécurité Alimentaire (CSA)/Projet de Mobilisation des Initiatives en matière de Sécurité Alimentaire au Mali (PROMISAM), Bamako, 1995.

- AMPJ, Expérience de l’AMPJ dans le renforcement des capacités techniques et d’organisation des femmes de Zantiébougou, Atelier international sur le traitement, la valorisation et le commerce du karité en Afrique, Dakar, 2002.

- ICRAF, Consultative regional workshop on shea product quality and product certification system design (6–8 October 2004), World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), with support from the Common Fund for Commodities (CFC) and the Netherlands Government under Project CFC/FIGOOF/23, Improving Product Quality and Market Access for Shea Butter Originating from Sub-Saharan Africa Bamako, 2004.

- R. Pawson N. Tilley Realistic Evaluation 1997 Sage London

- A.H.J. Helmsing S. Vellema Governance inclusion and embedding: raising the issues A.H.J. Helmsing S. Vellema Value Chains, Social Inclusion and Economic Development: Contrasting Theories and Realities 2011 Routledge London, New York 1 19

- O. Hospes J. Clancy Unpacking the discourse on social inclusion in value chains A.H.J. Helmsing S. Vellema Value Chains, Inclusion and Endogenous Development Contrasting Theories and Realities 2011 Taylor & Francis Group Routledge, Milton Park, Abingdon

- K. Jansen S. Vellema What is technography? NJAS – Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 57 2011 169 177

- A.B. Cunningham Non-timber products and markets: lessons for export-oriented enterprise development from Africa S. Shackleton C. Shackleton P. Shanley Non-timber Forest Products in the Global Context 2011 Springer Verlag Berlin, Heidelberg 83 106

- C. Kilby What determines the size of aid projects? World Development 39 2011 1981 1994

- D.J. Koch A. Dreher P. Nunnenkamp R. Thiele Keeping a low profile: what determines the allocation of aid by non-governmental organizations? World Development 37 2009 902 918

- R. Burger T. Owens Promoting transparency in the NGO sector: examining the availability and reliability of self-reported data World Development 38 2010 1263 1277

- M. Elias Practicing geography: reflections on an uncommon encounter between research and practice Research and Practice in Social Sciences 1 2006 156 167

- J. Sydow Path dependencies in project-based organizing: evidence from television production in Germany Journal of Media Business Studies 6 2009 123 139

- S. Knack A. Rahman Donor fragmentation and bureaucratic quality in aid recipients Journal of Development Economics 83 2007 176 197

- M. Edwards D. Hulme Scaling up NGO impact on development: learning from experience Development in Practice 2 1992 77 91

- I. Atack Four criteria of development NGO legitimacy World Development 27 1999 855 864

- J.-P. Platteau F. Gaspart The risk of resource misappropriation in community-driven development World Development 31 2003 1687 1703