Highlights

| • | Niche experiments tend to focus on niche-internal learning processes. | ||||

| • | Innovation projects cannot respond to a changing societal context without learning. | ||||

| • | Social learning about a project's environment should be expressly organised. | ||||

| • | Learning between niche experiment and outside world is essential for transitions. | ||||

| • | Senge's Field of Change offers an innovative approach to learning in transitions. | ||||

Abstract

According to transition science, system innovation requires experimentation and social learning to explore the potential of innovations for sustainable development. However, the transition science literature does not elaborate much on the learning processes involved. Senge's Field of Change provides a more detailed approach to the role of learning and action in innovation. We linked the Field of Change to transition management literature in order to explore social learning in an agricultural innovation experiment in the Netherlands called the ‘New Mixed Farm’. Our findings show that the project partners focussed primarily on the level of action and did not learn about (the values prevalent in) their environment. Our analysis suggests that social learning about a project's environment should be organised specifically to avert the risk of a project ignoring its environment. Furthermore, the relevance of social learning in relation to societal context is shown: an innovation experiment that does not or cannot learn about its environment is unable to respond to mounting societal pressures and therefore prone to failure. Finally, the results show that the Field of Change can be related to transition theory in order to provide a more detailed approach to learning in system innovation.

Abbreviations:

1 Introduction

Innovation and learning are often seen as two sides of the same coin [Citation1]. This is particularly true for system innovation, which is not about improving a current system (doing things better), but structurally changing it (doing better things) [Citation2,Citation3]. System innovation requires experimentation and learning to explore the potential for sustainable development of new technologies, new ways of doing things and new product-market combinations. System innovation is not a process that can be managed or organised, but it does seem possible to contribute to the conditions that favour change. Many scholars in the field of system innovation have therefore argued that working towards system innovation requires different forms of both learning and action [e.g.,Citation1-Citation4].

Traditionally, innovation was often regarded as a linear process of research, development, communication and implementation [Citation5]. This conceptualisation has been especially successful when applied to innovation for system optimisation. However, it does not do much justice to the more complex social and societal processes such as learning that form an integral part of innovation processes [Citation6,Citation7]. These processes are especially important for system innovation, which involves transformation rather than optimisation of a system. The linear model of innovation therefore is not well fit to the study of system innovation. The field of transitions [Citation8] focuses specifically on system innovation. In this view, the organisation of innovation experiments can teach us about preferable pathways to the future [Citation2,Citation9,Citation10].

What should be learnt in these innovation experiments? A successful innovation experiment presumes a social learning process, in which multiple societal parties (e.g., business, NGO's, science, government) use their knowledge and resources to foster the innovation and its potential for structural societal change: the multiple parties use their differences to each others’ benefit [Citation11]. Scientifically, theories on social learning are especially well-known in the field of natural resources management [e.g.,Citation12-Citation14]. Leading theorists in the field of transitions also emphasise the importance of (social) learning processes to foster change [e.g.,Citation8,Citation9]. However, these theoretical contributions do not elaborate much on learning processes, and empirical data about social learning in the context of system innovation is rather scarce. More important, however, is that the literature on social learning pays scant attention to the learning occurring on the communicative interface between innovation experiment and the outside world, mostly focussing instead on specific project groups who enter a well-defined trajectory of social learning [Citation15]. However, social learning for innovation requires a broad and dynamic network where participants are often included in the innovation coalition on a temporary basis [Citation16,Citation17]. Innovation processes that aim at making changes at the systemic level are particularly political, where communication with the outside world is very important [Citation18]. In such a dynamic environment, innovation processes often have to deal with conflicting narratives and discourses that come out of different value systems [Citation19,Citation20]. In this paper we therefore focus on internal learning processes in an innovative niche and how these processes relate to the outside world:

| 1. | How does social learning occur between a niche experiment and its environment? | ||||

| 2. | How can we foster social learning in the context of a niche experiment? | ||||

We answer these questions by analysing an innovation experiment for sustainable agriculture called the “New Mixed Farm” (NMF). The NMF applies principles from industrial ecology to agriculture [Citation21,Citation22]. It is an example of an ‘agro-park’: it combines a pig-farm, a chicken farm, a mushroom grower and a greenhouse cucumber grower [Citation23,Citation24]. The experiment promises intensive animal husbandry but without many of its environmental disadvantages. At the same time, however, intensive animal husbandry is a topic of hot public debate [Citation25] and that makes the communication with the outside world especially relevant for this type of innovation project.

This paper begins with a review of social learning in the context of societal transitions in Section 2. Subsequently we introduce our case in more detail, as well as the means we have used to gather and analyse our data in Section 3. Section 4 presents an analysis of the social learning process in the New Mixed Farm project. The paper ends with implications for social learning theory and the practical relevance for innovation processes.

1.1 Analytical framework: Social learning for socio-technical transitions

Transition scientists study long-term processes of profound societal transformation that “involve mutually coherent changes in practices and structures [. These transitions,] because of their multilayeredness and inevitable entrenchment in society and culture at large, are very complex and comprehensive phenomena” [Citation26,p. 3]. Formulated slightly differently, transitions can be defined as fundamental changes in society's structure, culture and practices [Citation2]. This means that triggering a transition is an inherently political process that tries to influence all these elements.

“Managing” a transition involves iterative cycles of (1) problem structuring, establishing the transition arena; (2) developing sustainability visions and transition pathways; (3) initiating and executing niche experiments and (4) evaluating, monitoring and learning [paraphrased from 2, p. 198, also see 27, p. 172]. These steps are known as the transition management cycle [Citation2,Citation27]. The complexity involved makes it very difficult to manage or steer transitions. As a consequence, experimentation and learning are important aspects of transitions [Citation2,Citation28].

Niche experiments are used to develop innovations that have the potential to trigger a transition. Fraught with uncertainty, niche experiments only have a limited view of what's ahead, and a high level of uncertainty about the outcomes of decisions along the way. Therefore, conducting one is much like going on an expedition: you know where you want to end up, but you don’t know what you’re up against on the way there. Steering is mostly limited to preparing as well as you can and to learning along the way, drawing lessons from past experiences in order to make better decisions for further action [29–31Citation[29]Citation[30]Citation[31]]. So, how can niche experiments draw these lessons? What learning does it take to conduct a niche experiment?

1.2 Social learning for transitions

The concept of learning, as used in transition science, begins with the assumption that learning occurs and knowledge can be created through conversations and interactions between stakeholders. The scholarly concept of “social learning” [e.g. 11-13] applies to this type of process–new ideas are not necessarily the work of one brilliant individual. Instead, many new ideas come from applying existing ideas in a new social context, or by the recombination of existing ideas [Citation32], which stimulates creativity and innovation. Here, we define social learning as a process in which people align, share and discuss their ideas together, with the outcome that they develop new shared mental models, form new relationships, and develop the capacity to take collective action and manage their environment [cf. 11,Citation33,Citation34]. Shared visions thus become an important driver for the process of transitions [Citation35]. It is important to note that, in our conception, social learning is a naturally occurring process. It can benefit from active facilitation, but this is not a necessary condition for social learning to occur. On the other hand, bringing diverse people together is not a guarantee for social learning, because diversity may well be a source of conflict instead of mutual benefit [Citation14].

Innovation projects are always set in a specific societal environment. Some niches are spatially rather localised, meaning that the regional environment can be vital for the project's success. Other niches concern entire production chains which may reach beyond the national level. So, the external environment can vary considerably from project to project. The internals of the project are more clearly delimited by the shared aims to which the project members work. Regarding the communication between the innovation project and its environment, Wals, Van der Hoeven and Blanken [Citation36] use the metaphor of a jazz ensemble to describe social learning that occurs within a project, connected with the social learning that takes place between the project and the audience. In a similar vein, Senge distinguishes between external learning processes in terms of changing societal discourses and internal learning processes [Citation1]. Value orientations play an important role in these learning processes [e.g.,Citation13,Citation14]. Van Eeten [Citation37] has shown that a strong conflict between value orientations can result in a stalemate in which parties cease to listen, and only learn to strengthen their own arguments. The metaphorical jazz ensemble can play all it likes, the audience have collectively plugged their ears. On the other hand, there needs to be at least some innovation or novelty to interest an audience at all [Citationcf. 38]. This suggests that it is especially relevant to recognise different value orientations, and to integrate them into a process design [Citation39,Citation40]. If we accept the interconnectedness of actors and their activities in a societal context (e.g. in food systems), then the underlying value systems of societal actors become relevant for (the process design of) an innovation experiment.

To sum up, theories on social learning distinguish between the learning within a project (the metaphorical jazz ensemble) and society-wide learning (in the metaphorical audience). Especially for the latter, it is important to take into account different value orientations to create an effective learning process. However, this does not yet tell us what the social learning should be about, or how we should facilitate it.

We adopt Peter Senge's Field of Change [Citation1] to connect the concept of social learning to transitions literature, and to be able to more closely consider the relationship between the niches and their audience. His approach offers a framework for experiments for system innovation, while also including specific notions about learning.

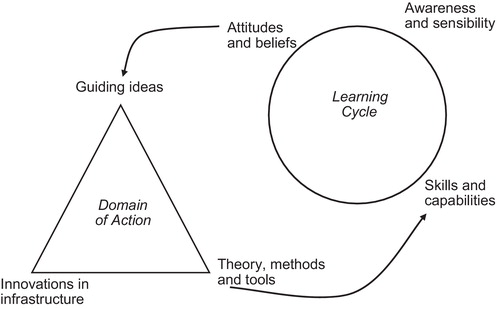

According to Senge et al. [Citation1] (see ) innovation involves a cyclical process that consists of a Learning Cycle and a Domain of Action. The domain of action consists of a guiding vision, adequate tools and methods and an innovative infrastructure in which new innovations can take place that lead to a transition of the system. The guiding vision concerns those ideas that are the core of an innovation. The theory, tools and methods are necessary to implement the guiding vision. The innovations in infrastructure are those innovations that the innovation depends on, but are not under direct control of the innovators. The Learning Cycle includes the attitudes and beliefs within the project, the skills and capabilities of the project members, and awareness of, and sensibilities for external developments and actors. Especially awareness and sensibilities direct one's attention to different societal value orientations, although value orientations are not explicitly included in the learning cycle.

1.3 A Field of Change perspective on niche experiments

Application of the Field of Change perspective to niche experiments illuminates how various actors collaborate within a sociotechnical niche to develop the transition potential of an innovation, such as a new technology / social practice, and how it might be able to yield some kind of revenue. In the case of sustainable development, such a proposition concerns an increased sustainability performance compared to business-as-usual, which can be operationalised by its effect on people, planet and profit-criteria [“triple bottom line”; 3,Citation41,Citation42]. In other words, how the new technology / social practice yields value for society at large (people), for the environment (planet) and for the entrepreneur (profit). In the case of the New Mixed Farm: closing nutrient loops, improved disease control, in-house slaughtering, and on-site energy production are all propositions aimed at increasing people and planet values at the same profit, as compared to business-as-usual in intensive animal husbandry. Here we regard the transition potential of a niche experiment as a guiding idea in the Field of Change sense.

The process of developing a niche experiment requires specific tools, methods and theories. In the case of the New Mixed Farm, one might think of the technology needed to generate energy from biogas, or the legal knowledge about how to acquire building permits for a slaughterhouse. Various innovations in infrastructure are needed during the process of conducting an innovation experiment. In the case of the New Mixed Farm: getting permits to build a new facility, designing all farm buildings and the infrastructure in-between, establishing contact with other entrepreneurs in the same neighbourhood, building an energy network, etc.. These are aspects of innovation infrastructure in the sense of the Field of Change.

When compared to the theory of transition management, Senge's Field of Change offers a more detailed perspective on the interplay between learning and action. Moreover, it offers some starting points for studying the relations between a niche experiment and its environment. In the domain of action, innovations of infrastructure play an important role for the niche experiment while being mostly under control by the outside environment. In that sense, changes in infrastructure constitute a direct link between a niche experiment and its environment. In the learning cycle, awareness and sensibilities have an “object” outside the niche experiment–they always concern an awareness of, or sensibility for someone or something outside the project, such as value orientations in society and how they relate to the goals and activities of the project. Awareness and sensibilities can therefore also be seen as a direct link between niche experiment and environment.

The Field of Change yields two insights about social learning in innovation experiments. First, the domain of action highlights in broad terms what the learning process should be about. Second, the learning cycle highlights various aspects of the social learning process. For these reasons, the Field of Change appears to be a good starting point for studying social learning in the context of innovation experiments. We therefore applied the field of change to the New Mixed Farm case. The main research questions were:

| 1. | How does social learning occur between a niche experiment and its environment? | ||||

| 2. | How can we foster social learning in the context of a niche experiment? | ||||

2 Material and Methods

Document analysis and interviews were used as a basis for information about the case, the New Mixed Farm innovation experiment.

2.1 Case selection

The New Mixed Farm project was subsidised by TransForum, a Dutch innovation platform that aimed to trigger transitions toward sustainable agricultural development through experiments with promising agricultural innovations [Citation3,43; www.transforum.nl]. TransForum was active from 2005 to 2010. TransForum's portfolio sported a wide range of projects, including about 35 innovation experiments and about 25 scientific projects. TransForum received Dutch government funding under the BSIK (Knowledge Infrastructure Investment Subsidies Decree) scheme to develop innovations for sustainable development and to find ways to improve the Dutch agricultural knowledge infrastructure. The BSIK scheme used matched funding, which means that private partners had to match government funding. TransForum projects received just short of 50 percent of funding from the government.

The New Mixed Farm was selected for its specific project history. It had become one of TransForum's most controversial projects because of rising tensions between the project, its local environment and national public debates about large-scale intensive farming. The project was a clear example of the importance of learning beyond the project boundaries for the chances of success of an innovation experiment.

2.2 Data

We used project documentation insofar as it was available at TransForum to study the social learning within the project. A total of 16 official project documents were used in the analysis. To study the external communication of the project with its social environment and especially the role of different value orientations of the main actors involved, we conducted eight semi-structured interviews with a total of ten persons. Interviewees included one of the farmers wanting to start the New Mixed Farm, a member of the steering group supporting the New Mixed Farm, a scientist involved in the development stages of the initiative, the local alderman and a civil servant of the municipality Grubbenvorst, a provincial administrator of the province of Limburg, a member of the TransForum project team, a civil servant from the Ministry of Agriculture, and two members of the local action group “Behoud de Parel” (in English: “Save the Pearl”, in reference to the local village of Grubbenvorst) who opposed the establishment of the New Mixed Farm in their neighbourhood. The interviewees thus included some of the most important actors with knowledge of the historical developments of the initiative. Furthermore, they had given voice to the conflicting arguments and values on intensive husbandry that clashed in this particular case.

The semi-structured interviews were conducted by the same two interviewers using a list of topics for discussion focussing on the role of attitudes, beliefs, awareness, sensibilities and value orientations of the interviewees and of other actors involved with the New Mixed Farm. Topics discussed included: 1) the respondent's own background and personal involvement in the project, 2) the identification of the different stakeholders and the role they played in the development of the initiative, and 3) the different discourses and value systems of these stakeholders. Finally the existing barriers for the implementation and their preferred solution of the existing gridlock were discussed [Citation44].

2.3 Analysis

We use the Field of Change as an analytical framework. To that end, we adapted it by defining the following coding categories:

| • | Guiding Ideas: The leading ideas that inspired the set-up of the project. Guiding ideas can be abstract, but in practice they also can be quite concrete. Some guiding ideas may not be explicitly available to the project partners. | ||||

| • | Innovation in Infrastructure: The changes in infrastructure necessary for the development of the innovation. Infrastructure was used in a very broad sense to include aspects of law, knowledge, logistics, energy and other resources. | ||||

| • | Theory, Methods and Tools: The insights and methods, etc. that are used to bring about the innovation. | ||||

| • | Attitudes and Beliefs: Attitudes and beliefs reflect our general inclinations towards a certain topic or theme, our convictions. There is some overlap between theory and beliefs. We chose to distinguish between general and abstract insights that were held to be important for the project (coded theory) and personal beliefs and convictions that were not necessarily held to be true (coded beliefs). | ||||

| • | Awareness and Sensibilities: Every innovation experiment takes place in a wider societal context. Awareness and sensibilities concern knowing the context and its sensitivities, and how they relate to the innovation experiment. | ||||

| • | Skills and Capabilities: What a person or actor or a group is able to do. | ||||

The codes were applied using an open coding [Citation45] strategy in a phenomenographical sense [Citation46,Citation47]. This means that, for every document, all conceptually different aspects of the project were coded, for each of the categories guiding ideas, innovations in infrastructure, theory-methods-and-tools, attitudes and beliefs, awareness and sensibilities and skills and capabilities. This resulted in a list of qualitatively different descriptions of the aspect of the innovation project. The first author applied the codes to each available project document. The third author then verified the analysis. The analysts discussed and resolved all differences in opinion about the analysis.

The interview data was mainly used to add to the interpretation of the analysis by including the value orientation of actors around the NMF initiative (the audience, as it were). Furthermore, the interview data was used to corroborate the document analysis, by applying the same coding categories. The interview analysis did surface additional codes for the analysis.

Learning was assumed to be reflected in changes in the domain of action and/or the learning cycle. Structural changes in either were taken as evidence that the project entered a new phase, and as an indication that learning might have occurred. Small additions that were in line with the rest of the project were not taken as evidence for a new phase.

2.4 Case context

In this paper, we analysed an innovation experiment for sustainable agriculture called the ‘New Mixed Farm’ and its troubles in establishing its innovative concept in a ‘designated agricultural development area’, or ADA, near a small town in the Netherlands.

The initial idea for the NMF was inspired by thinking in industrial ecology and industrial symbiosis [Citation21,Citation22]. Four entrepreneurs: a pig-farmer, a chicken farmer, a mushroom grower and a greenhouse cucumber grower, decided to try and integrate their production processes, saving energy and re-using the waste of their respective production processes as input for the others’ production processes. The initiative promises intensive agricultural production but without its many environmental disadvantages. However to make the project financially rewarding the scale of the projects means a significant enlargement of the amount of animals to be held within one location. The initial plans included the accommodation of 3,700 sows, 9,700 pigs, 19,700 hogs, 1.2 Million chicks and 74,000 chickens.

After a particularly bad epidemic of classic swine fever in the mid-1990s the Dutch government designed an ambitious new policy aimed at restructuring both the intensive animal breeding sector and the countryside for synergetic effects on social, environmental and economic criteria. The ‘Reconstruction Act’ was decentralised and left to the provincial authorities and municipalities to implement. The reconstruction includes three area types. The extensification areas are located near valuable or fragile nature conservation areas. These areas can no longer host intensive animal breeding and existing farms need to relocate. The second zone is an area where nature and intensive piggeries are ‘weaved together’, and where they can co-exist. However, the piggeries’ size is maximized and no additional pigs are allowed to be produced. In order for the agricultural sector to maintain its future perspective, the third type of zone is established and this is the agricultural development area, (ADA; in Dutch: Landbouw Ontwikkelings Gebied). The ADAs also serves as a destination for the farms relocated from the extensification areas.

Grubbenvorst is a small town (4790 inhabitants in 2007) located in the South of the Netherlands in the province of Limburg. This town historically has had a strong agricultural sector and an intensive animal breeding population. According to a local government official, 40% of the local employment depends on agribusiness and that was one of the reasons to develop an ADA in the municipality of Grubbenvorst. The location ‘Witveldweg’ was chosen as the future site of the ADA and even though it is intended first and foremost for the (re)location of local intensive animal husbandry, it also has left open from the start the possibility of the location of new businesses under the requirement that the new business is operating both innovatively and sustainably–a perfect location, therefore, for the New Mixed Farm initiative.

3 Results

We distinguished three different phases in the project based on the analysis of the project documents and the interviews. For each phase, first the historical developments of the project are described. Then the Field of Change is applied, after which we reflect on the social learning process.

3.1 Phase 1–2004-2006–Starting up

Our analysis begins with the year 2004, when the NMF applied for TransForum funding. At that time, the NMF consisted of a pig-farm, a chicken farm, a mushroom producer and a greenhouse cucumber grower. This combination of enterprises offered various options for environmental value creation. The opportunities identified included producing mushroom compost from manure, electricity production from biogas, and production of warmth and CO2 for the greenhouse grower.

summarises the project's Field of Change for the first phase. The project partners were aware of both local and broader societal sensitivities about intensive agriculture, and intensive animal husbandry in particular. They were aware that intensive agriculture was suffering from a bad image. Their attitude towards these sensitivities was positive: the project members regarded them as valid and thought that they should be addressed. They were convinced that the sustainability element (closed greenhouse concept, better animal wellbeing) was so strong that it should overrule other concerns. From their point of view, the NMF in the form at its inception was a valid answer to societal concerns about intensive agriculture. As a consequence, they expected the NMF to meet with widespread societal approval.

Table 1 The New Mixed Farm according to the Field of Change 2004-2006.

The theory, methods and tools were predominantly technical in nature and the planned innovations in infrastructure were all geared to the physical and legal realisation of the project. In this phase, a lot of the learning processes within the project were directed at technicalities. Emerging questions concerned issues like how to vent stables, how to prevent stench, and what material to use for stable floors.

Although the partners believed that they could meet opposition from local actors, they did not have any ideas or means to address or meet such opposition. This can be seen as a misfit between the project's awareness and beliefs on the one hand, and its capabilities regarding communication on the other: one would expect communication to be an important learning goal for the project members. In other words, the learning process was very much oriented at the ‘inside’ of the project: the domain of action, and not so much at the world outside.

3.2 Small changes in 2004

The project underwent various changes before actually taking off. The biggest was that the greenhouse farmer left the project out of fear of becoming tainted with the negative image of industrial farming. A tomato grower temporarily took his place, but left soon after. The remaining project members then decided not to have one specific greenhouse farmer in the project, but to make use of the proximity of a nearby greenhouse cluster, which could also be supplied with CO2 and heat.

Another change in the project was increased modularisation. The initial plan entailed direct exchange of residual flows between the businesses involved. This was changed to the inclusion of a separate facility for biorefinery to produce biogas, CO2, heat and energy. This change was a direct reaction to the departure of the greenhouse growers. One entrepreneur leaving the project could not be allowed to endanger the project as a whole. Additionally, the entrepreneurs found out that pumping manure between different legal entities was not legally allowed. This means that the functions for the exchange of residual flows needed to be taken care of by a separate entity, and not by all the partners together. Therefore, the plan now included a separate biorefinery.

Analysis-wise, these changes were not interpreted as a new phase in the NMF project, because they did not co-occur with structural changes to the guiding ideas, the infrastructure or the theory, methods and tools. In fact, it is interesting to see that when the greenhouse farmers left, the remaining partners did not change their attitudes and beliefs regarding the image of the NMF and how they too might become tainted by the existing negative image of the intensive animal husbandry sector. They only concluded that a modular set-up was more important than they thought. Nonetheless, the move toward increased modularisation can be seen as a clear learning result, stemming from the experience of how the departure of a project member might harm project continuity.

3.3 Phase 2–2006-2009–Communication and the shock of societal opposition

At the beginning of phase 2, the partners were busy buying land and applying for permits with the local government, meaning that the project finally got under way. Furthermore, the project set-up had changed again, now also the mushroom farmer had left the project, because of financial problems. After that, the project included three partners, who each had their own company. Two partners were farmers, and the third partner was a technical company that would build the biorefinery. The idea was that the other partners would buy the biorefinery later. Part of the legal process involved an Environmental Impact Assessment.

The second phase of the project was marked by the addition of a monitoring mechanism: an individual from outside the project was added solely to monitor the learning process and progress of the project. The project monitor, by then, had become standard procedure for TransForum innovation experiments, to improve and speed up social learning. The monitor did so by offering reflections on on-going events and by holding reflection meetings to gather and document the learning results within the project. This was a clear change to the project's Capabilities. The monitor helped the project partners to increase their awareness of the societal context but no changes occurred in the project itself ().

Table 2 The New Mixed Farm according to the Field of Change phase 2006-2009.

3.4 Societal opposition

Until 2006, the project partners had not communicated with the neighbours, despite their expectations of local opposition. Although they had developed a communication plan, it had not yet been carried out. Also, they had hired a communication firm for communication with the neighbours. However, the firm turned out not to fit well with the project partners, and in the end the firm was dropped. The main progress in the project seemed to be related to overcoming internal problems regarding the biorefinery and its ownership, and to a lesser extent to the interaction with the government about permits. This is indicative of the predominantly technical orientation of the entrepreneurs and their relative blind spot for (non–technical) value orientations in society.

Meanwhile, the project did meet societal opposition, triggered by the legal procedure of establishing an agricultural development area (ADA) with legal designation for intensive agricultural activities. It had become known that the initiative of the NMF was to be realised within the ADA, nearby the highway A73 in an area characterised by an open landscape. Contrary to the partners’ expectations, the initiative became associated with the negative connotations of intensive livestock agriculture. The belief that the NMF would meet societal approval turned out to be demonstrably false.

Communication about the NMF finally took place over the course of 2006 and 2007. The project members started sending out a news letter and organised information meetings. Furthermore, the project was closely followed by a regional newspaper and received a lot of attention from political opponents, especially from the Socialist Party and the affiliated action group “Behoud the Parel”. Opposing players also organised information evenings to communicate about NMF. For the NMF project members, the focus of these meetings was to hear expert opinions of opponents and proponents of the NMF, and to try to address local concerns of neighbours.

The interview data show that the NMF initiative became the focus of a national debate about very large-scale farms. A coalition of a local action group and national environmental organisations fundamentally questioned the added sustainability value of the NMF. This came as a surprise for the entrepreneurs. This was not a discussion about technological advantages of the NMF but rather a fundamental clash of value systems: the entrepreneurs’ conviction that upscaling was necessary for more sustainable agriculture, versus the opponents’ questioning whether large-scale agriculture could be sustainable at all.

From a learning perspective, it is striking that, by this time, still no change in attitudes and beliefs occurred. Although society clearly had a negative image of the NMF by then, the project members were unable to align their attitudes and beliefs with this development. Instead, they felt misunderstood and under-appreciated. Misunderstood, because in their eyes, the public clearly did not understand that the NMF was very different from traditional intensive animal husbandry and that it offered sustainability advantages. It was beyond the entrepreneurs’ understanding how anyone could be against that. The entrepreneurs felt under-appreciated, because they sincerely believed that their project would address many if not all of the public's concerns about intensive animal husbandry. This lack of learning is even more surprising considering that, by this time, an external project monitor is already facilitating learning processes within the project.

Incidentally, it does seem particularly jarring that, according to the interview data, several new intensive animal farms were realised during this period, in the vicinity of the NMF location. This was done within the legal possibilities of the physical planning system, but without any sustainability advantages. These new farms decreased the quality of the relatively open landscape and contributed to the upscaling of intensive agriculture, but received none of the opposition that the NMF was confronted with.

3.5 Phase 3–2009-2011–Polarisation and survival

Confronted with the public opposition, the entrepreneurs decided to stop communicating with local actors and societal opponents from 2009 onwards. They judged that the legal procedures (e.g., environmental impact assessment, building permits) were not helped with an ongoing controversy. The confrontation with different value orientations had cost energy and did not contribute to the project ().

Table 3 The New Mixed Farm according to the Field of Change phase 2009-2011.

3.6 In closing

From the interview data, it is clear that local authorities were just as surprised as the project members by the public reaction to the NMF initiative. In an attempt to overcome the public scepticism, they asked for an independent sustainability scan, which indicated that the NMF had a better sustainability performance than standard agricultural practice of the same scale. Furthermore, the local authority formulated specific conditions for how NMF should fit the existing landscape, which was a first for Dutch agriculture. However, these actions did not sway the opponents. Their concerns were not so much oriented at the specific technological features of the NMF, but rather concerned the underlying values. The interview data showed that national opposition derived mainly from being opposed to the idea of large-scale farms and the implied necessity of exporting and/or producing meat for the global scale. The interview data suggest that local actors mainly reacted to an accumulation of activities in the region (Floriade 2012, trade port development, a sand excavation project), which generated a landscape impact that made Grubbenvorst villagers feel threatened in their identity and not taken seriously by government levels.

Despite all the opposition the project endured, it has not been called off. Indeed, at the time of this writing the project members have acquired permits to start building. It is not yet clear whether there will be a New Mixed Farm in the end. The project members appear to be overwhelmed by project internals, which require so much attention that there is still little learning directed at the outside world. As a result, the project's chances of survival are to an important extent at the mercy of government officials.

4 Discussion

The main research questions were: 1) how does social learning occur between a niche experiment and its environment, and 2) how can we foster social learning in the context of a niche experiment? With regard to the first question, the analysis shows that the project partners focussed primarily on technical and legal issues. Specifically, the analysis suggests that the complexities associated with conducting innovation experiments can overwhelm the project members, which results in a lack of attention to learning and to communicating with neighbours and other stakeholders. Furthermore, the project history, in particular the mounting societal opposition to the project in phase two, shows the relevance of the learning cycle and of awareness and sensibility especially: if an innovation project is unable to learn about its environment, it cannot respond to a changing societal context. In answer to the first research question, these observations show that it is important that project members not only focus their learning efforts inward, on realisation of the domain of action, but also outward, on the “audience”, to increase their awareness of and sensibilities for their societal environment. It also shows that, at least in the case of the New Mixed Farm, such a learning process did not occur by itself. The case evidence thus shows that social learning processes in innovation projects are elusive and that project members are easily distracted from issues in their project's environment. For innovation projects in the context of societal transitions, our results suggest that social learning processes should be expressly organised to mitigate the risk of an innovation project that does not learn about its environment.

There may be some reasons to qualify this conclusion. The conflict that emerged between the NMF initiative and its local and national opponents took shape as a “dialogue of the deaf” [Citation37]: the opponents in such a dialogue are very much concentrated on strengthening their own positions while not paying attention to the other's position. In the case of the NMF, the entrepreneurs have gone great lengths to explain the sustainability gains of the NMF, while the opponents concentrated on issues of public health, landscape and natural resources. Applying the Field of Change framework we found that the domain of action is relatively stable. This is not expected in an environment with opposing value belief systems. Although an interface was organised, this was not able to break through the technical orientation of the entrepreneurs and the supporting knowledge environment. When confronted with the negative reactions, the entrepreneurs shifted their attitude towards polarisation and survival. Their main goal in the third phase was simply to obtain the necessary permits. In other words, both the project members and the opponents learned a lot, but they did not learn from each other. Rather than the metaphor of a jazz ensemble and an audience, this situation brings up the metaphorical image (and sound) of two jazz ensembles playing in the same room, without any audience.

The specific qualifier that needs to be made is that it is unclear whether a renewed focus on learning from the outside world can help a project escape from a “dialogue of the deaf.” The proper way, with social learning, would be to arrive at either a consensus, or at least an agreement to disagree, and a solution. However, in this specific case the underlying values were so different and so strong that even consensus about a solution (as opposed to consensus about the underlying values) may have never been possible at all. If, in a specific practice situation, one is convinced that social learning among opponents is possible, then it should be part of the project right from the start, especially when related debates occur in society at large [Citationcf. 35]. If one is not so convinced, then the question is whether it is wiser to focus on winning a political or legal battle instead of trying to socially learn one's way out of a deadlock.

With regard to the second research question, of how we can foster social learning, the addition of the project monitor was a notable change to the project in terms of learning capabilities. The analysis does not suggest that the addition of the monitor to the NMF project has improved the project's learning capabilities. This may be due to the rather late time at which the monitor was added. Also, the project monitor might have had more impact with a more specific task, such as helping the project members engage in understanding different societal value positions. Nevertheless, the addition of the project monitor certainly is in line with the conclusion that some aspects of social learning may need to be specifically organised to prevent that an innovation project only focuses on internal matters. This may also have been an important reason for TransForum to add the project monitor at that time.

Given the role of the project monitor, the conclusion appears to be warranted that organisational and process designs do offer opportunities to foster social learning. However, they are no guarantee for success. As the saying goes, you can lead a horse to water but you cannot make it drink. The results regarding the dialogue of the deaf that steadily evolved do offer some further starting points for process design of an innovation experiment. The New Mixed Farm case gives a strong indication of the importance of relating to existing societal value orientations, their relation to the innovation experiment, and their development over time. The use of the project monitor in TransForum was mainly oriented at the niche experiment itself, as a kind of organisational design. However, the monitor also offers the possibility to implement some process design to strengthen the interface with other stakeholders and other value orientations. While indeed the actual developments in the New Mixed Farm do not suggest a structural effect of the project monitor, they do suggest that learning capabilities are important. Furthermore, the fact that the project monitor became an accepted project aspect to the initiators of the niche experiment itself suggests that a project monitor at least is a feasible, if not necessarily effective, way of organisationally influencing the learning capabilities of a niche experiment.

With regard to the theoretical framework, it seems from the analysis that some relations can be drawn between transitions theory and the Field of Change. Most elements in the Field of Change (i.e., guiding ideas, theories methods and tools, attitudes and beliefs, and capabilities) appear to be (mainly) under the control of the innovation experiment. They can be seen as part of the “experimenting” step in the transition management cycle. However, innovations in infrastructure are mostly beyond the control of the innovation experiment. Furthermore, the project's awareness and sensibilities appear to be oriented at societal concerns and perspectives and how they relate to the innovation experiment. It would seem that awareness and sensibilities (in the learning cycle), and that innovations in infrastructures (in the domain of action) are at the interface between the niche project and its societal environment.

Scholarly articles about social learning have rarely included learning effects beyond the project level [Citation15]. The case of the New Mixed Farm clearly demonstrates that one project can result in learning at multiple levels. However, in this specific case there was no learning between different levels, rather, two opposing learning processes occurred at different societal levels. The findings presented here suggest that social learning research can be enriched with the notion that social learning should always include the awareness and sensibilities of those beyond the project level. If not, then the project proceeds blinded to the outside world, with markedly less chance of success.

5 Conclusions

The findings from the current case study show that, without support, social learning processes may be focussed on internal project matters only, neglecting learning about the project's environment. This lowers the project's chance of success. Therefore, social learning about a project's environment should be specifically organised in order to avert this risk. Furthermore, the case study has shown that transition theory can be related to Senge's Field of Change. This suggests an interesting option for future research, that is, to study more niche experiments and compare the conclusions to the findings from the New Mixed Farm experiment. Indeed, several past TransForum projects may be interesting for a multiple case study, as well as more current initiatives toward system innovation. Transition theory still is a rather young field internationally. We hope that this article will contribute to furthering the international debate about transitions and learning.

Acknowledgment

We would like to express our gratitude to Henk C. van Latesteijn. Our discussions with him about the case were an important inspiration for this article.

References

- P.SengeA.KleinerC.RobertsR.RossB.SmithThe Fith Discipline Fieldbook. Strategies and tools for building a learning organization1994DoubledayNew York

- D.LoorbachJ.RotmansManaging transitions for sustainable developmentX.OlshoornA.WieczorekUnderstanding Industrial Transformation: Views from Different Disciplines2006Springer187206

- A.VeldkampA.C.V.AltvorstR.EwegE.JacobsenA.V.KleefH.V.LatesteijnS.MagerH.MommaasP.J.A.M.SmeetsL.SpaansJ.C.M.V.TrijpTriggering transitions towards sustainable development of the Dutch agricultural sector: TransForum's approachAgron. for Sustain. Dev.2920098796

- F.HermansM.StuiverP.J.BeersK.KokThe distribution of roles and functions for upscaling and outscaling innovations in agricultural innovation systemsAgric. Syst.1152013117128

- E.M.RogersDiffusion of Innovations5th edition ed.2003Free PressNew York

- C.LeeuwisA.W.Van den BanCommunication for Rural Innovation: Rethinking Agricultural Extension2004Blackwell ScienceOxford

- IAASTDInternational assessment of agricultural knowledge, science and technology for development: global report2009Island PressWashinton D.C

- J.RotmansR.KempM.B.A.Van AsseltMore evolution than revolution: transition management in public policyForesight320011531

- A. Rip, R. Kemp, Technological change, in: S. Rayner, E.L. Malone (Eds.) Human Choice and Climate Change, 1998, pp. 327-399.

- J.SchotR.HoogmaB.ElzenStrategies for shifting technological systems: the case of the automobile industryFutur.26199410601076

- A.E.J.WalsSocial learning towards a sustainable world2007Wageningen Academic PublishersWageningen, The Netherlands

- R.IsonN.RölingD.WatsonChallenges to science and society in the sustainable management and use of water: investigating the role of social learningEnviron. Sci. & Pol.102007499511

- C.Pahl-WostlThe importance of social learning in restoring the multifunctionality of rivers and floodplainsEcol. and Soc.112006

- C.LeeuwisR.PyburnWheelbarrows full of frogs; Social learning in rural resource management2002Koninklijke Van Gorcum BVAssen

- M.S.ReedA.C.EvelyG.N.R.CundillI.FazeyJ.GlassA.LaingJ.NewigB.ParrishC.PrellC.RaymondL.C.StringerWhat is social learningEcol. and Soc.2010

- A.H.Van de VenThe innovation journey1999Oxford University PressNew York

- F.HermansD.van ApeldoornM.StuiverK.KokNiches and networks: Explaining network evolution through niche formation processesRes. Pol.422013613623

- L.KlerkxN.AartsC.LeeuwisAdaptive Management in agricultural innovation systems: The interactions between innovation networks and their environmentAgric. Syst.1032010

- C.LeeuwisN.AartsRethinking Communication in Innovation Processes: Creating Space for Change in Complex SystemsJ. of Agric. Educ. and Ext.1720112136

- F.HermansK.KokP.J.BeersT.VeldkampAssessing Sustainability Perspectives in Rural Innovation Projects Using Q-MethodologySociologia Ruralis5220127091

- R.U.AyresIndustrial MetabolismJ.H.AusubelH.E.SladovichTechnology and Environment1989National Academy PressWashington, D.C2349

- J.R.EhrenfeldIndustrial Ecology: A framework for product and process designJ. of Clean. Prod.519978795

- P.J.A.M.SmeetsExpeditie Agroparken: Ontwerpend onderzoek naar metropolitane landbouw en duurzame ontwikkeling2009in, Wageningen University, Research CentreWageningen

- J.HinssenH.SmuldersVan dingen beter doen naar betere dingen doen; vergelijkende analyse agroparken in Nederland2011in, Telos, TSC, TransForum en ERACTilburg

- C.J.A.M.TermeerG.BreemanM.Van LieshoutW.PotWhy more knowledge could thwart democracy: configurations and fixations in the Dutch mega-stables debateR.J.’t VeldKnowledge Democracy – Consequences for Science, Politics and Media2010SpringerHeidelberg99112

- J.GrinJ.RotmansJ.SchotTransitions to Sustainable Development; New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change2010RoutledgeOxford, UK

- D.LoorbachTransition Management for Sustainable Development: A Prescriptive, Complexity-Based Governance FrameworkGov.: An Int. J. of Pol., Adm., and Institutions232010161183

- R.RavenS.Van den BoschR.WeteringsTransitions and strategic niche management: towards a competence kit for practitionersInt. J. of Technol. Manag.5120105774

- U.BeckA.GiddensS.LashReflexive modernization; politics, tradition and aesthetics in the modern social order1996Stanford University PressStanford USA

- J.-P.VossB.BornemannThe Politics of Reflexive Governance: Challenges for Designing Adaptive Management and Transition ManagementEcol. and Soc.162011

- J.-P.VossD.BauknechtR.KempReflexive governance for sustainable development2006Edward Elgar PublishingCheltenham, UK; Northampton, USA

- R.S.BurtBrokerage and closure; an introduction to social capital2005Oxford University PressOxford, UK

- L.C.StringerA.J.DougillE.FraserK.HubreckC.PrellM.S.ReedUnpacking “Participation” in the Adaptive Management of Social-ecological Systems: a Critical ReviewEcol. and Soc.112006

- D.ArmitageM.MarschkeR.PlummerAdaptive co-management and the paradox of learningGlob. Environ. Chang.1820088698

- P.J.BeersA.VeldkampF.HermansD.van ApeldoornJ.M.VervoortK.KokFuture sustainability and imagesFutures422010723732

- A.E.J.WalsN.Van der HoevenH.BlankenThe acoustics of social learning2009Wageningen Academic PublishersWageningen, The Netherlands

- M.Van EetenDialogues of the deaf: defining new agendas for environmental deadlocks, in: Department of Technology1999Delft University of Technology, PublisherEburon, Delft183pp. XIII

- B.NooteboomW.Van HaverbekeG.DuystersV.GilsingA.Van den OordOptimal cognitive distance and absorptive capacityRes. Pol.36200710161034

- A.R.EdwardsThe sustainability revolution: portrait of a paradigm shift2006New Society PublishersGabriola Island, Canada

- C.O.ScharmerTheory U: Leading from the future as it emerges, the social technology of presencing2009Berrett-Koehler PublishersSan Francisco

- H.C.Van LatesteijnK.AndewegThe need for a new agro innovation systemH.C.Van LatesteijnK.AndewegThe TransForum Model: Transforming agro innovation toward sustainable development2011SpringerDordrecht

- J.ElkingtonCannibals with forks: the triple bottom line of 21st century business1998New Society PublishersGabriola Island, Canada

- A.FischerP.J.BeersH.C.Van LatesteijnK.AndewegE.JacobsenH.MommaasJ.C.M.Van TrijpTransForum system innovation towards sustainable food. A reviewAgron. for Sustain. Dev.322012595608

- J.P.P.HinssenI.HorlingsF.HermansBotsende beelden; over innoveren bij maatschappelijke tegenwind - een vertooganalyse over het nieuw gemengd bedrijf2010in, TelosTilburg

- A.L.StraussQualitative analysis for social scientists1987Cambridge University PressCambridge, UK

- F.MartonPhenomenography - describing conceptions of the world around usInstr. Sci.101981177200

- F.MartonPhenomenography - A research approach to investigating different understandings of realityJ. of Thought: An Interdiscip. Q.2119862849