?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

A number of studies based on stated behaviour suggest that consumption of organic food is part of a life style that involves healthy eating habits that go beyond shifting to organic varieties of the individual food products. However, so far no studies based on observed behaviour have addressed the relationship between organic purchases and diet composition. The aim of the present paper is to fill this gab using purchase data for a large sample of Danish households. Using a Tobit regression analysis, the diets of households with higher organic consumption were found to include more vegetables and fruits but less fat/confectionary and meat which is in accordance with the official Danish Dietary Recommendations. Moreover, higher organic budget shares were found among well-educated consumers in urban areas and clearly linked to a belief that organic products are healthier. No statistical relations were found between consumption of organic food and perceptions that organic production is more animal or environmentally friendly.

1 Introduction

Stated preference studies suggest that organic consumption is an integrated part of a life style that involves a healthier diet. The aim of the paper is to investigate whether observed purchase data can be used to support and potentially shed new light on these findings. We have been inspired by the difficulties that earlier studies have encountered in establishing a clear health benefit of consuming organic food as opposed to non-organic food when using product-by-product comparisons. Instead, we suggest an approach that takes differences in the composition of diets into account (a diet–by-diet comparison). More specifically, we use adherence with the official Danish Dietary Recommendations as an approximation of a healthy diet and the size of the organic budget shares as an approximation of organic consumption. In these settings, we use a large data set covering almost 1,400 Danes’ food purchases to investigate whether there is a positive correlation between following the official Danish Dietary Recommendations and the size of the organic budget shares. A more detailed account of the background is provided in Section 2. The data and econometric models are presented in section 3, results are described in section 4 and subsequently discussed and concluded upon in section 5.

2 Background

The consumption of organic food in Denmark had a boom in the nineties when a major supermarket chain began to use an organic image as a marketing strategy and increased the supply and visibility of organic products. Today, a wide variety of organic products is available in most Danish supermarkets and discount stores at relatively low price premiums. Despite the introduction of the mandatory EU organic label in 2010, almost all organic products processed, packed or labelled under the control of the Danish authorities also carry the voluntary national label. With an organic consumption corresponding to around 8% of total food expenditures in 2013, Denmark is one of the countries with the highest organic demand per capita [Citation1].

There is a considerable literature on consumer perceptions of organic food and of factors that affect organic food consumption. It is repeatedly found that higher levels of urbanization, income, and education have a positive effect on organic consumption. Furthermore, women typically purchase organic more often than men, while the relationship between age and the propensity to consume organic products is more complex [2–6Citation[2] Citation[3] Citation[4] Citation[5] Citation[6]].

In Aertens et al. [Citation7], it is concluded that self-seeking interests are more important than socio-demographic characteristics when trying to understand the motives behind organic consumption. Aertens et al. [Citation7] apply an integrated framework that involves the theory of planned behaviour [Citation8] as well as Schwarts's value theory [Citation9]. Thereby, they include the importance of attitudes, norms, and perceived behavioural control as factors affecting purchase intentions and possibly actual purchases as well as the importance of universal values as drivers of behaviour. They find that health, which is related to the universal value security, is the strongest argument for purchasing organic food. People might associate organic products with enhanced health for a variety of reasons. Saba and Messina [Citation10] find that people link increased health with absence of pesticides while Lee et al. [Citation11] emphasise the importance of a firm belief of higher nutritional values in organic products. Despite the importance of health motives as a driver of organic consumption, it seems to be difficult to scientifically prove unambiguously that organic products are healthier than their non-organic counterparts [12–14Citation[12] Citation[13] Citation[14]]. Only, few studies stand out and find specific organic products to be more nutritious than their non-organic counterpart [Citation15,Citation16]. Next to health considerations, other private good attributes as the belief that organic food is fresher or better tasting than conventionally grown food have been found to significantly increase intensions to buy organic food [Citation7,Citation17].

Although private good attributes often are the most important drivers for many organic consumers, values are indeed also attached to public good attributes as environmentally and animal friendly production [4,6,7,18–22Citation[4] Citation[6] Citation[7] Citation[18] Citation[19] Citation[20] Citation[21] Citation[22]].

Existing studies on organic consumption using observed purchase data have focused on the explanatory power of socio-demographic characteristics and motives relating to perception of organic products. We find it fair to conclude that these factors only partly are able to explain demand for organic food. Instead, we suggest using observed purchase data to pursue findings from interview studies or stated preferences suggesting that preferences for organic food are positively correlated with a healthy living. Indeed, studies based on stated behaviour find that organic consumption interact with other life style choices concerning diet composition. Pelletier et al. [Citation23] thus reveal a relation between a positive perception of organic food and stated intake of fruit and vegetables among students in the US. In a qualitative study Lund and Jensen [Citation24] found that Danish consumers with high organic demand were more focused on a healthy diet. Their finding is supported by a survey of Danish consumers’ stated purchases from 2010 which reports that the 25% of consumers with the lowest organic consumption consumed around twice as much meat as the 25% of consumers with the highest organic consumptionFootnote 1 .

Empirical research indicates some discrepancy between stated behaviour and observed behaviour [Citation25]. However, to the authors’ knowledge no studies based on observed behaviour have been carried out to document the relation between healthy eating habits and organic consumption. Consequently, we test whether these findings based on consumers’ stated preferences behaviour can be supported by an analysis using actual purchase data from a large panel of Danish consumers supplemented with data on attitudes and perception about food. This unique combination of data opens the possibility to include several important groups of food products which constitute a large part of the diet and control for variables essential for dietary choices. The official Danish Dietary Recommendations encourage a high intake of vegetables and fruit and discourage sugar and fat, particularly saturated fat from meat and dairy products [Citation26]. In line with these recommendations, we investigate whether increasing budget shares of organic foods can be linked to food categories with particular importance for the nutritional quality of consumers’ diet. Four product groups are selected (fruit, vegetables, meat, and fat/confectionary) as they represent food for which there are relatively clear guidelines communicated to the population.

3 Method

3.1 Data description

The analysis is based on data from GfK Consumertracking Scandinavia. Actual behaviour of Danish consumers is observed through purchase data for the period 2003-2007. The data consist of registrations of purchases of daily commodities made by a panel of around 1,400 Danish households. This data set includes daily registrations of purchases of a large variety of food types and cover approximately 80% of the total household grocery budget, while missing reports, restaurant meals, lunches in canteens, etc. account for the remaining 20% [Citation27]. All purchases for the households are reported on a weekly basis by the main diary keeper in each household. The data provide multiple information concerning the products including price, quantity, store name, etc. Due to the scope of the present study we exclude products corresponding to a value of 18.5% of all reported purchases as no information concerning organic or non-organic production is providedFootnote 2 . Background socio-demographic characteristics are collected once a year. An important feature of the data is that a comprehensive questionnaire concerning attitudes and perception of food was answered by the panel members in 2007 (for more details see Andersen [Citation28]). This makes it possible to analyse the relation between behaviour, household characteristics, and attitudes towards food.

Obvious risks of using purchase data to investigate organic consumption include that some products might mistakenly be categorized as organic (or vice versa) just as food purchased is not necessarily identical to food eaten. However, in Denmark almost all certified organic food is clearly labelled or purchased in organic specialty stores. The vast majority of the consumers recognize the organic label and many have a very positive perception of it. In particular, Janssen and Hamm [Citation29] compare consumers’ perceptions of organic logos in seven European countries and the results emphasize that the level of awareness and trust to the national logo is particularly high among Danes. Registration errors are therefore not considered to be a serious problem in the purchase data. Another potential bias in using purchase data to assess consumption behaviour is linked to food waste. Indeed, there is increasing awareness of food waste in primary production, in the retail sector, amongst households, canteens, etc. Studies have estimated that 20% of food budgets end up in garbage bins [Citation30,Citation31]. There is no indication that organic consumers are more likely to throw food away than other consumer groups. On the contrary, it has been suggested that promoting organic consumption might be a way of reducing food waste. Due to the organic price premiums, the purchase of organic food could be a more conscious choice which is likely to induce consumers to reduce wasteFootnote 3 . At the same time, organic food products often have a shorter durability than the conventional versions which may pose a challenge for initiatives to reduce waste of organic food. Despite the importance of reducing food waste, the topic is not pursued in the present study. In the remaining part of the paper, the terms purchase and consumption are used interchangeably in the analysis of purchase data.

3.2 Model description

The overall aim of the model is to explore to what extent organic consumption and dietary decisions are linked. In practice, we investigate to what extent organic budget shares depend on the expenditures of individual categories of food, attitudes towards food and socio-demographic variables. Thereby, the model builds on existing knowledge in terms of the importance of attitudes for explaining organic consumption, see Aertens et al. [Citation7] and Li et al. [Citation32]. In addition, by including dietary decisions, the model is able to capture possible effect on organic consumption of the healthiness of food purchases.

Due to differences in price premiums across individual products within each of the four food groups, our dietary results are formulated in monetary terms and cannot be directly converted to physical quantities. As a measure of the households’ organic consumption we use the organic budget shares which are defined as shares of the food budget spent on organic versions. The organic budget share is the dependent variable denoted, y

1it

(i = 1,…,1,375 represents households and t = 1,…,5 represents year). Four groups of explanatory variables are included. The first group of variables captures the healthiness of a household's food purchases as measured by budget shares of food that represent healthy as well as non-healthy food choices. More specifically, a vector represents budget shares for vegetables (frozen and fresh vegetables), fruit (fresh fruit), meat (liver pâté, sausages, sliced meat, meat - except poultry), and fat/confectionary (butter, margarine, sugar, ice cream, cakes, marzipan/nougat, crisps). In order to capture the effects of the overall choice of diet, not limited to organic purchases, these budget shares include organic as well as non-organic versions. Also total food expenditures of a household, denoted x

exp,it

are included in order to adjust for increased organic budgets shares of people who generally spend more money on food. Secondly, attitudes are represented by a vector (

), which consists of the main shopper's attitude towards a number of potential characteristics of organic production that may affect organic purchases. More specifically, attitudes towards the following statements, shown in full length in , were included, 1) organic food contains more vitamins than non-organic food, 2) organic food is of poorer quality, 3) organic food contains less pesticides and medicine residues, 4) organic production is more environmentally friendly, 5) organic production is associated with better animal welfare. Also, the main shopper's attitude towards the following two potentially health related statements that were expressed as important health concerns in the questionnaire are included, 6) it is important that my food does not contain any artificial ingredients, and 7) it is important that my food has a low fat content. The third group of explanatory variables, socio-demographic characteristics,

, includes urbanisation, social class, number of children and adults in the household, age and gender of the main shopper. Fourthly, a continuous variable representing time, τ, accounts for a linear trend over time that might affect organic budget shares. Finally, random variables are included to capture non-observable variations in the data.

Household beliefs and attitudes (N = 1,375).

There is a concentration of organic budget shares at the value zero as 6.7% of households choose never to buy organic food. Furthermore, estimated organic budget shares should be non-negative. Consequently, a conventional regression method like OLS is considered problematic. Instead, a Tobit regression, that can handle such corner solutions and restricted values, is chosen [Citation33,Citation34]. The Tobit model is a hybrid between a probit model which is often used to model the discrete choice of buying organic or not and a regression model estimating the amount of organic food bought. In order to take account of the panel structure in the data, a random effects Tobit regression is used. The model can be written as follows:(1)

(1)

The observable organic budget share, y

1it

, equals the latent variable, , when the latent variable is strictly positive. The error term υ

1i

is only allowed to vary between households and thereby captures the household specific random effects while the error term ɛ

1it

varies between observations. Both error terms are assumed to be uncorrelated with the observed explanatory variables. The estimations were performed in STATA 11.

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive statistics

The analysis is based on a balanced panel of the 1,375 households who reported food purchases at least once a year during the period from 2003-2007 and who answered the questionnaire in 2007. The mean organic budget share for the households is 4.8% (s. d. 8.4) and ranges from a minimum of 0% to a maximum of 92%. Detailed descriptions of purchases concerning diet as well as variables elicited routinely in the panel are provided in .

Table 1 Descriptive statistics of the panel and their food purchases (N = 1,375).

The table shows that consumption of organic and non-organic vegetables, fruits, meat, and fat/confectionary on average represents almost half of the products included in the analysis. This suggests that these products are important indicators for the diet of the households. The organic price premiums vary from approximately 15% for organic milk, 30% - 40% for cheese, vegetables, and fruit, to around 50% for organic meat, and 60% for bread coffee, fat, and eggsFootnote 4 . The households’ beliefs and attitudes towards food which were elicited in the 2007 questionnaire are shown in . The distributions of the five attitudinal statements concerning organic food give us the impression that consumers in general have rather high expectations of the virtues of organically produced products. More than 40% believe that organic products are nutritionally superior to conventional products and of better quality. An even larger share, approximately 70% of the consumers state that organic products contain less chemical residues or that the products are better for animals and the environment.

4.2 Estimation results

The estimated relationship between organic budget shares and diet composition is presented in . The first column of estimates in shows the marginal effects of the explanatory variables on the latent variable. The second column of estimates shows the marginal effects of the explanatory variables on the observed dependent variable which accounts for the fact that changes in the explanatory variables affect both the conditional mean of organic purchases as well as the probability of making a purchase.

Table 3 Estimation results (s. e.).

The F-test (not shown in ) indicates that, taken jointly, the coefficients are significant (P < 0.0001). Also, the individual random effects are significant and contribute with 82% of total variance. The estimations confirm that increasing vegetables or fruit budgets increase a household's organic budget share. In particular, the estimations suggest a strong positive relation between purchases of vegetables and organic food. Conversely, increasing budget shares for meat and fat/confectionary reduce a household's organic budget share. No significant relation between total food expenditures and organic demand is found.

In order to illustrate the relation between diet composition and organic purchases the households are divided into four user groups. We follow the approach applied in Denver et al. [Citation35] and divide the households into five groups based on their organic budget share in 2007.

shows that 7% of the households spend more than 20% of the food budget on organic versions. However, the average organic budget share of consumers in this group is 35.5%. Only 6% did not purchase any organic food in 2007.

Table 4 Distribution of five user groups according to organic purchases.

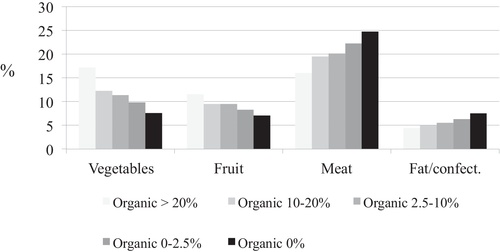

The relations between consumption of the four products groups and organic purchases are shown in . Indeed supports that households with a high organic consumption eat more vegetables and fruits but less meat and fat/confectionary. Noteworthy, it indicates that the group of consumers with the highest organic budget share spend a large share of the food budget on vegetables - around twice as much as consumers who do not buy any organic food.

While observed budget shares for the four groups of products indicate that organic consumers are relatively conscious about keeping a low intake of unhealthy products, consumers who state that they prefer low-fat products tend to purchase less organic food (). As expected, we find a relatively large positive correlation between consumers, who express that it is important that food do not contain artificial substances, and the organic budget share. indicates that consumers who believe that organic food is healthier or of better quality purchase more organic food. All three statements regarding private good attributes have an effect on the organic budget share of the same magnitude. Remarkably, the organic budget share is uncorrelated with acknowledgement of the two public good attributes concerning environmentally or animal friendly production.

An evaluation of the importance of socio-demographic characteristics suggest that the results support existing knowledge and indicate a higher organic consumption among single adult households, higher social classes and households living in Copenhagen or other urbanised areas. The organic budget share increases with the number of children, while the number of adults or gender of the main shopper seems to have no significant effect on the organic budget share. The positive trend variable indicates that the organic budget shares have increased during the period.

5 Discussion and conclusion

By applying a diet-by-diet comparison, we found statistical evidence for a relation between choice of diet and the consumption of organic food. The study indicates that households who eat more vegetables and fruit, but less meat and fat/confectionary are more likely to have a higher consumption of organic food. The consumption of vegetables is found to have a stronger impact than fruit on organic budget share. The explanation may be related to earlier findings that consumers choosing to eat organic food tend to be more interested in cooking and therefore more likely to spend time preparing vegetables. Overall, our study supports earlier findings from stated preference studies – but also adds new details to the understanding of organic consumption.

A desire to avoid unwanted substances in food in order to improve health has repeatedly been stated as a main reason for buying organic food. Moreover, almost half of the respondents in the survey believe that organic food contains more minerals and vitamins than conventional products. Despite these signs of trust in the health virtues of organic food, it has been difficult to prove that organic varieties are healthier in a product-by-product comparison. In line with Wier et al. [Citation36], we find no significant relation between stated perception of animals’ welfare and environmental benefits in organic production and purchases of organic food. Our finding of a clear link between the purchase of organic food and adherence to the Dietary Recommendations suggests that health as a driver of organic consumption not only involves a desire to avoid unwanted substances, but also a desire to pursue a diet in accordance with the Dietary Recommendations. This indicates that organic consumption may be an integrated part of a life style where multiple aspects of health are involved.

It should be noted though, that all types of meat are not equally bad and all types of vegetables and fruits are not equally good. For example, there are substantial differences in fat contents depending on the specific cuts of meat just as meat also contains important nutrients. Similarly, there are differences between vegetables and fruits with respect to content of dietary fibers and vitamins. Such details are not taken into consideration in this study as it is based on rather rough dietary guidelines encouraging a high consumption of vegetables and fruits and a low consumption of saturated fat from meat.

Our findings of a healthier diet among organic consumers might partly be driven by the unbalanced availability of different categories of organic food. The supply of vegetarian organic products is relatively high compared to the supply of organic meat and organic fat/confectionary. Consequently, substitution towards more fruits and vegetables might be driven by the limited availability among consumers who prefer to substitute within the available organic products, see Denver and Christensen [Citation37]. Thereby, households with high preferences for organic food can be induced to pursue a diet in accordance with the Dietary Recommendations. Such ‘forced’ substitutions are likely to be less common in the future as the supply of organic varieties is increasing over time.

Due to organic price premiums, one would expect households who purchase organic food to have higher food expenditures. Budgetary considerations may therefore induce a household with high preferences for organic products to substitute organic meat or highly processed foods, which are relatively expensive, with vegetables or other unprocessed, basic products with lower prices and/or lower price premiums. The estimation suggests that total costs of reported purchases do not significantly effect on the organic budget share. This is a very noteworthy result which requires further analyses to be confirmed. In this context it is interesting that canteens that have shifted to a more organic menu are seen to switch to a diet which is composed of less meat and more unprocessed seasonal vegetables [Citation38]. For canteens, the literature clearly indicates that the change in diet is mainly driven by budget considerations. It is less clear whether organic consumers eat healthy due to budgetary or health concerns. These insights are valuable inputs for our understanding of health related consumption decisions, for promotion of healthier life styles, and in marketing of organic produce.

Brandt et al. [Citation16] use a meta-analysis to conclude that there are more nutrients in organic fruit and vegetables to such an extent that switching from conventional to organic varieties, without changing the consumption patterns, could result in an estimated average increase in life expectancy of 17 days for women and 25 days for men. While this improvement seems relatively modest, the dietary differences between organic and non-organic consumers may induce much larger consequences on physical health and life expectancy.

Even though the relation between total dietary fat intake and organic consumption is not assessed in this study the results indicate that organic consumers may have a lower fat intake. An interesting twist in the relation between organic consumption and consumption of low-fat products was found. The study suggests that while organic consumers have a lower intake of fat and confectionary, low-fat products are perceived as more important by people with lower organic consumption. A possible explanation is that organic consumers do not care about or even dislike low-fat products. An alternative explanation could simply lie in the limited availability of low-fat organic products, e.g. low-fat cheese or low-fat minced meat. This would force consumers with strong preferences for low-fat products to choose a conventional low-fat version instead of the organic full-fat version. In this case, increasing the availability of organic low-fat product could potentially attract a new segment of consumers. Further research is needed to accept or reject these hypotheses.

A limitation of the study is that it is based on budget shares rather than on physical quantities. Hence, it only provides an indication of the tendency to follow the diet recommendations. As the price premiums of organic vegetables are relatively low compared to price premiums of meat, the relation between a household's organic consumption and its dietary composition based on budget shares cannot be directly transferred to quantities. More detailed estimations of the degree to which the recommendations are met by consumers with different organic consumption therefore need to include physical quantities rather than budget shares. However, for a detailed assessment of dietary patterns we recommend that additional data are collected concerning the share of the purchases which is, due to e.g. missing shopping reports, not included in the data. This shortcoming of the data set will be more important when evaluation of the diet against the Dietary Recommendations is carried out.

Another shortcoming of the data set is that it is not completely up to date. The average organic budget shares in Denmark have increased from 5.5% in 2007 to 8% in 2014 [Citation1]. The average diet among Danes in 2003-2008 and 2011-2013 are compared in Pedersen et al. [Citation39]. They conclude that the intake of vegetables with low dietary fiber content and fish has increased whereas there has been an increase in the consumption of red meat and fat and a decrease in the intake of potatoes, vegetables with higher dietary fiber content and fruits. They also conclude that the average Danish diet still is too fat, too sweet, and with too low a dietary fiber content. How these developments have affected the relation between healthy eating habits and organic consumption is an interesting question.

According to [Citation27] the panel is representative according to the geographical distribution of the households as well with respect to age. Contrary to this, households with children and low income households are overrepresented. In addition, members of the panel may be different from other consumers in other ways. It is thus likely that the involvement in the panel have made them more conscious about their food purchases. Furthermore, they may in general be more structured and disciplined than others which may also apply to their food habits. These considerations have to be weighed against the benefits of being able to observe the same households over a longer period of time but should be kept in mind if the results are extended to the total population.

Hopefully our paper will inspire future work into identifying motivations as to why organic households have different diets than non-organic households and how these choices are linked to different perceptions of healthiness.

Notes

1 FDB Analysis http://fdb.dk/nyhed/%25C3%25B8kologiske-forbrugere-belaster-klimaet-mindre [accessed on June 11 2012]

2 The fact that information about production method is not provided does not mean that no organic alternatives are available.

3 http://www.altinget.dk/artikel/oekologi-kan-minimere-madspild [accessed on November 24 2013].

4 Own calculations based GfK-data for 2006.

References

- Organic Denmark (2014). Organic market note. June 2014. Organic Denmark. In Danish.

- A.C. Bellows B. Onyango A. Diamond W.K. Hallman Understanding Consumer Interest in Organics: Production Values vs. Purchasing Behavior Journal of Agricultural & Food Industrial Organization 6 2008Article 2

- A. Gracia T. de Magistris The demand for organic foods in the South of Italy: A discrete choice model Food Policy 33 5 2008 386 396

- A. Jonas J. Roosen Demand for Milk Labels in Germany: Organic Milk, Conventional Brands, and Retail Labels Agribusiness 24 2 2008 192 206

- S. Monier, D. Hassan, V. Michèle, M. Simioni, Organic food consumption Patterns, Journal of Agricultural & Food Industrial Organization 7: article 12, Special issue: Quality Promotion through Eco-labeling, (2009).

- B. Roitner-Schobesberger I. Darnhofer S. Somsook C.R. Vogl Consumer perceptions of organic foods in Bangkok, Thailand Food Policy 33 2 2008 112 121

- J. Aertens W. Verbeke K. Mondelaers G. Van Huylenbroeck Personal determinants of organic food consumption: a review British Food Journal 111 10 2009 1140 1167

- I. Ajzen The Theory of Planned Behavior Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50 2 1991 179 211

- S.H. Schwartz Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 25 1 1992 1 65

- A. Saba F. Messina Attitudes towards organic foods and risk/benefit perception associated with pesticides Food Quality and Preference 14 2003 637 645

- W.-c.J. Lee M. Shimizu K.M. Kniffin B. Wansink You taste what you see: Do organic labels bias taste perceptions? Food Quality and Preference 29 1 2013 33 39

- M.K. Magnusson A. Arvola U.K. Hursti L. Aaberg P.O. Sjödén Choice of organic foods is related to perceived consequences for human health and to environmentally friendly behavior Appetite 40 2 2003 109 117

- M. Huber E. Rembiałkowska D. Średnicka S. Bügel L.P.L. van de Vijver Organic food and impact on human health: Assessing the status quo and prospects of research NJAS - Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 58 3–4 2011 103 109

- L. Guéguen G. Pascal Organic food, Encyclopedia of Human Nutrition Third Edition 2013 413 417

- A. Vallverdú-Queralt A. Medina-Remón I. Casals-Ribes R.M. Lamuela-Raventos Is there any difference between the phenolic content of organic and conventional tomato juices? Food Chemistry 130 1 2012 222 227

- K. Brandt C. Leifert R. Sanderson J. Seal Agroecosystem Management and Nutritional Quality of Plant Foods: The Case of Organic Fruits and Vegetables Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 30 1–2 2011 177 197

- M. Wier K.O. Jensen L.M. Andersen K. Millock The character of demand in mature organic food markets: Great Britain and Denmark compared Food Policy 33 5 2008 406 421

- A.M. Aldanondo-Ochoa C. Almansa-Sáez The private provision of public environment: Consumer preferences for organic production systems Land Use Policy 26 3 2009 669 682

- R. Griffith, L. Nesheim, Household willingness to pay for organic products, Discussion Paper No. 6905, Centre of Economic Policy Research, 2008. Available online: http://www.cepr.org/pubs/dps/DP6905.asp.

- C. Fotopoulos A. Krystallis M. Ness Wine produced by organic grapes in Greece: using means – end chains analysis to reveal organic buyers’ purchasing motives in comparison to the non-buyers Food Quality and Preference 14 7 2003 549 566

- S. Padel C. Foster Exploring the gap between attitudes and behaviour British Food Journal 107 8 2005 606 625

- H.J.N. Schifferstein P.A.M.O. Ophuist Health-related determinants of organic food consumption in the Netherlands Food quality and preference 9 3 1998 119 133

- J.E. Pelletier M.N. Laska D. Neumark-Sztainer M. Story Positive Attitudes toward Organic, Local, and Sustainable Foods Are Associated with Higher Dietary Quality among Young Adults Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 113 1 2013 127 132

- T.B. Lund, K.O. Jensen, Consumption of Organic Foods from a Life History Perspective: An Explorative Study among Danish Consumers, Country Report Denmark, Department of Human Nutrition, University of Copenhagen, Denmark, 2008.

- M.J. Carrington B.A. Neville G.J. Whitwell Lost in translation: Exploring the ethical consumer intention-behavior gap Journal of Business Research 67 1 2014 2759 2767

- A. Astrup, N.L. Andersen, S. Stender, E. Trolle, Kostrådene 2005, Publikation nr. 36, Ernæringsrådet og Danmark Fødevareforskning, 2005.

- S. Smed, En sociodemografisk analyse af den danske fødevareefterspørgsel, Fødevareøkonomisk Institut, København, Rapport nr. 146, 2002.

- L.M. Andersen, Documentation of CONCEPTS questionnaires, Institute of Food and Resource Economics University of Copenhagen (2009), Available online: http://orgprints.org/15741/1/15741.pdf [accessed on July 15 2013].

- M. Janssen U. Hamm Product labelling in the market for organic food: Consumer preferences and willingness-to-pay for different organic certification logos Food Quality and Preference 25 1 2012 9 22

- J. Gustavsson, C. Cederberg, U. Sonesson, R.V. Otterdijk, A. Meybeck, Global food losses and food waste – extent causes and prevention (2011) http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/ags/publications/GFL_web.pdf [accessed on July 7 2011].

- J.D. Jensen, Economic assessment of food waste in Denmark [Vurdering af det økonomiske omfang af madspild i Danmark], Commissioned report 2011/6, Institute of Food and Resource Economics, University of Copenhagen, 2011.

- J. Li L. Zepeda B.W. Gould The Demand for Organic Food in the U.S.: An Empirical Assessment Journal of Food Distribution Research 38 3 2007 54 69

- J. Tobin Estimation of relationships for limited dependent variables Econometrica 26 1 1958 24 36

- J.M. Wooldridge Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data 2002 The MITT Press

- S. Denver T. Christensen J.D. Jensen K.O. Jensen The Stability and Instability of Organic Expenditures in Denmark, Great Britain, and Italy Journal of International Food and Agribusiness Marketing 24 1 2012 47 65

- M. Wier L.M. Andersen K. Millock Information provision, consumer perceptions and values: The case of organic foods S. Krarup C. Russell Environment, information and consumer behavior 2005 Edward Elgar Cheltenham, UK 161 178

- S. Denver T. Christensen Consumers’ grouping of organic and conventional food products - implications for the marketing of organics Journal of Food Products Marketing 20 2014 408 428

- Canteen, 2010. Spis efter årstiderne, Kantinen, nr. 3, Kantineledernes Landsklub, 2010. Available online: http://kantinen.dk/Files/Filer/Kantinen0310.pdf [accessed on June 22 2012].

- A.N. Pedersen, T. Christensen, J. Matthiessen, V.K. Knudsen, M. Rosenlund-Sørensen, A. Biltoft-Jensen, H.-J. Hinsch, K.H. Ygil, K. Kørup, E. Saxholt, E. Trolle, A.B. Søndergaard, S. Fagt. Dietary habits in Denmark 2011-2013. Main results. DTU Fødevareinstituttet Afdeling for Ernæring, Lyngby, Denmark, 2015.