Highlights

| • | A diagnostic tool to better trace and understand ripple effects from one institutional field to another is presented. | ||||

| • | Analyses ways in which new market rules can have an effect, beyond the activity of buying and selling. | ||||

| • | Gender blind changes in market rules may trigger unanticipated ripples on household rules. | ||||

| • | More research is needed to gain insights in the longer term consequences and pathways of ripple effects on agency and across institutional fields. | ||||

| • | Rule-guided market policy may expand opportunities for agents to transform constraining rules across institutional fields. | ||||

Abstract

The introduction of new rules in an institutional field provides agents with a new set of opportunities and constraints on which they can leverage to change the rules in other institutional fields. Inspired by Elinor Ostrom, we term this causality a ripple effect, born out of the initial institutional changes. In this article we enquired in what ways women farmers could transfer genderblind changes in the market to the household. We developed a diagnostic tool to capture this propagation of effects and tested our framework with a study of the Agricultural Commodity Exchange for Africa (ACE) in Malawi. We found that the introduction of ACE has produced weak but positive effects for women, some of which rippled the changes in the rules to improve their household situation. Some women see in trading with ACE an opportunity to retain freedom and avoid a constraining married position in the household.

1 Introduction

Institutions guide human behaviour and cluster in institutional fields that indicate the appropriate course of action in different situations. Most research on institutional fields studies them one by one, in isolation from each other, when in fact the number of institutions, their interconnectedness and their force are far greater than generally recognised by policy-makers, as CitationOstrom argued (2005). The social life of agents occurs across different institutional fields and in each one of them institutions have the double role of constraining and enabling agents’ action. An agent can find significant room for manoeuvre in one institutional field and a rather constraining environment in another institutional field. As institutions evolve, changes of rules enable or restrain a new collection of actions in an institutional field, and we reason that these changes can affect the agent’s repertoire of institutional opportunities and constraints in other institutional fields. In other words, agents can leverage on new sets of opportunities and constraints across institutional fields and their agency may be enhanced or further limited.

Table A1 Details of women farmers in sample.

Elinor Ostrom introduced the notion that changes in one institutional field “ripple” on other institutional fields CitationOstrom (2005: 58). Our motivation is to study these ripple effects, which we define as the propagation of rule changes in one institutional field on to another institutional field via the actions of agents. With this approach on institutional fields, we wondered if women could leverage on changes in the institutional field of the market to affect the gendered rules in the institutional field of the household. In principle, gender- blind policies and programmes are not designed to affect the gender rules and benefit women specifically. There is also a certain assumption in the feminist literature that changes in market institutions rarely contribute to the advancement of women’s positions in society, as highlighted by CitationScott et al. (2012). Some empirical studies on intra-household gender dynamics in Africa have already underlined the capacity of women to adapt their household strategies to benefit from market economic activities and “operate outside the constraints imposed by customary patriarchy” (Scott et al., 2012: 564).

We decided to adopt a pragmatist feminist perspective (CitationWhipps and Lake 2016, CitationScott et al., 2012, CitationMcKenna 2001, CitationSeigfried 1996) that postulates, for instance, that human action is creative, human beings have situated freedom, and action is adaptation fitted to the problematics of specific situations. We were inspired by CitationScott et al. (2012: 564) in highlighting that pragmatic feminism allows for the possibility that gender-blind market institutions may contain mechanisms that “can be harnessed for feminist purposes”. Diagnosing them correctly, as CitationRodrik (2010a, b)Citation reminds us, is far more challenging. We aimed at contributing a tool to better understand in what ways ripple effects occur.

2 Methodology

Our research was motivated by enquiring in what ways genderblind changes in the market institutional field enabled women to affect their situations in the household institutional field, if at all. This enquiry required to delve deeply into the daily lives of women that engage in both institutional fields, i.e. market and household. We hence chose to do a case study of the introduction of genderblind rules in a market where women trade, if possible with similar businesses. We were inspired by CitationMcCall’s suggestion (2005: 35) that case studies represent the most effective way of empirically researching the complexity of the way that the intersection of institutional fields on specific agents affects their everyday lives. We found suitable conditions for such a study with women farmers in rural Malawi, because we have a long research presence and would have the access that the study demanded. We selected the introduction of the Agricultural Commodity Exchange for Africa (ACE) in Malawi and focused on small holder farmers that produce maize, groundnuts, and pigeon peas in the central regions of the country. In 2013 ACE introduced a warehouse receipt system with access to finance and storage, a market information system and capacity building for farmers, and claims to have improved the choices of farmers. ACE documents make no mention of gender and do not address women farmers at all, despite the fact that the vast majority of farmers in Malawi, as in the rest of Sub-Saharan Africa, are women (CitationDoss, 2011, Citation2014). We hence concluded that it was a genderblind institutional reform in which gender considerations were basically ignored.

Our research had multiple objectives and dimensions, and in this particular paper we aim at understanding ripple effects and not to evaluate the impact of ACE on women. Hence, we designed a framework to gain insight into what different institutions “do” and “prescribe” from the experiences and stories of farmers. We focused only on women farmers and how they navigate the rules in the market and the households; we do not analyze the situations of men farmers. We designed the study for a small sample of women farmers who would share their personal life story for our research, used ACE services regularly and for at least three years, and wanted to improve their income. Our sampling needed to cover different household situations, so we asked ACE staff to identify for us twelve female smallholders that have been using ACE services since 2013. The sample included four married, four single and four divorced or widowed women. The data collection methods employed in the field were qualitative and involved semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions, retrieval of documents and marketing materials and news articles. Our fieldwork took place between February and May 2016. We also interviewed 9 ACE staff members, a local researcher and four experts. In addition, we did one focus group discussion with three female farmers. Interestingly, ACE struggled to identify young not-yet-married women in their client base, which could indicate a combination of different things such as few young women consider farming and trading commodities, Malawian women marry young, or ACE is inaccessible for young single women. To ensure spatial representation of the participants we selected participants in both semi-urban and rural areas of the central region of the country.Footnote1 The database is too limited to generalize our findings, but it has allowed us to proof our diagnostic tool to identify a ripple effect.

In the next section we set out our theoretical position and in section four we build a framework to diagnose ripple effects across institutional fields. In section five we discuss the situation of women in Malawi and in section six we scrutinise in what ways the introduction of ACE as a gender blind policy rippled to the benefit of women, if at all. We further discuss the potentials and limits of the framework to identify ripple effects and conclude with reflections on areas for future research.

3 Gender, institutions and ripple effects

Our study focuses on the actions of social actors, which are regulated by institutions in institutional fields. We follow Hodgson’s definition of institutions as embedded “systems of established and prevalent social rules that structure social interaction” (CitationHodgson 2006: 2), so institutions create stable expectations on the behaviour of others. In this definition, rules are “socially transmitted and customary normative injunction or immanently normative disposition that in circumstances X, do Y” (CitationHodgson 2006: 3). The introduction of a commodity exchange modifies the actions of buying and selling in the market in a pre-existing landscape of rules of exchange. The new institutions set rules of the type that in X do Y’ and in comparison to the previous set of rules, they create a disposition to modify behaviour at the time of trading.

As explained by CitationWacquant (1998), agents do not face undifferentiated social spaces but distinct spheres of life endowed with specific rules, regularities, and forms of authority. Authors address these clusters of institutions as fields (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992, CitationFligstein and McAdam 2011a, bCitation), domains (CitationLaumann and Knoke, 1987) or networks (CitationPowell et al., 2005). While they have different meanings, these terms generally address “meso-level social orders” where actors interact with knowledge of the rules, the relations and the purposes of the field (Fligstein and McAdam, 2011: 3). Each field has characteristics in terms of boundaries, origins and transformation.

Fligstein and McAdam (2011) describe the various fields as a set of Russian dolls, one inside the other, whereby changes in one institutional field can destabilise the rules in other fields. CitationOstrom (2005: 58) introduced the notion that changes in one institutional field “ripple” on others, so we will refer to these as ripple effects. We take the framework developed by CitationPolski and Ostrom’s (1999: 39) to analyse types of rules-in-use to capture how these prescriptions cluster to form an institutional field, and to follow how the introduction of new rules on market exchange has affected or not women’s lives in the household.

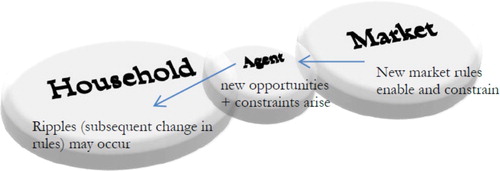

Several authors have referred to the complexity and interconnections among institutions and the context and field in which they emerge and operate (CitationOstrom, 2005; CitationSindzingre, 2006; CitationAndersson and Agrawal, 2011; CitationFligstein and McAdam, 2011a, bCitation). CitationPolski and Ostrom (1999) identified seven types of rules in any institutional field. The position rules affect participants (individuals or groups) when they perform a certain role. Participants are included or excluded from that position by boundary rules, while authority or choice rules prescribe what is possible and acceptable for the position. The action arena is further shaped by information rules that state what is known and communicated, and by aggregation rules which are the mechanisms to control a situation. Costs and benefits are regulated by payoff rules, and the likely outcomes depend on scope rules. These rules form together an institutional field, such as a market. represents any institutional field, such as a market in which “a farmer” occupies the position that, according to the position rules, can exchange goods via ACE.

Institutional fields centre on agents whose actions are informed by institutions and whose agency depends on. CitationHodgson (2003) argues that institutions act as hidden persuaders and both enable and restrain behaviour, so institutional change in one field may affect the agents’ sets of opportunities and constraints in the other fields where the agent is active. In the household, decision making and welfare distribution signal that households do not actually function in isolation but are affected by the “hidden enablers” in other fields. CitationSmajgl and Larson (2007: 15) contend that research often isolates the different fields of a social order despite the need to study them “as a part of the institutional layer it is embodied in, as well as part of the economic, ecological, social layers it might impact on or be impacted by”.

The concept of ripple effect captures subsequent and unintended changes in the rules that were not directly expected within the initial field of institutional change. We hence conceive a dynamic web of institutional fields in which changes in rules in one field can ripple out and create a pathway of change within and across other fields, so institutional fields are interconnected like Russian dolls, using the metaphor of CitationFligstein and McAdam (2011a, b)Citation. A married female farmer, for example, may occupy simultaneously the positions of wife and rural producer in the corresponding two institutional fields of household and market, so she manages a complex household and an agricultural business and can leverage opportunities in one on to her actions in the other field. CitationOstrom (2007: 35) describes the combinations and transfers of opportunities and constraints from one field to the other as “using rules to cope”. We will now design a diagnostic tool to identify these ripple effects.

4 A framework to diagnose institutional ripple effects

We first need to conceptualise further what ripple effects are. The concept refers to the propagation of an institutional change in one field to institutions in the same or another institutional field. Within social psychology, CitationMaddux and Yuki (2006) refer to ripple effects as the distal consequences of events. CitationSmajgl and Larson (2007) argue that ripple effects can change the effectiveness of existing institutions as well as the newly introduced institutions. We define ripple effects as the unintended or spontaneous dissemination of change in rules one institutional field upon rules in another institutional field, with consequences that can be either positive or negative because they are not susceptible to controlled planning. The pathway of the ripple and its long term outcome are uncertain; it may be stopped, diverted, reversed, slowed down or spurred. Hence, a ripple does not equal “a pathway of development” in the sense of positive change, such as gender equality or livelihoods.

Based on CitationSmajgl and Larson (2007: 15), in we attempt to depict the ripple effects from the changes of the rules governing the market institutional field to those of the household institutional field. Changes in one field can have effects on another field if the agents perceive the first rule change equips them to advance their agency in a second field or, as CitationOstrom (2007: 35) expressed it, “using rules to cope”. For example, women may see in the arrival of a new market institution an opportunity to stretch the boundaries of the gender rules that limit them in the household field.

We built the following framework () to identify ripple effects from one field upon the rules in another field, considering both the enabling and constraining effects of institutions. Our tool also draws from the multi-strand mapping framework developed by CitationParken (2010) that seeks to operationalise and capture intersectionality in policy development. However, our diagnostic tool places the analysis at the meso-level of institutional fields and not at the individuals’ level, as Parken et al. do, hence facilitating an analysis across institutional fields instead of capturing only different individual positions within one field. We used this tool in section four to capture ripple effects from the institutional fields of the market to the household.

Table 1 Diagnostic tool to identify ripple effects from one institutional field to another.

5 Our case: women in Malawi and the introduction of ACE

The Agricultural Commodity Exchange (ACE) operates in Malawi, one of the poorest countries in Sub-Saharan Africa.Footnote2 With a majority of livelihoods depending on agriculture, the population is highly vulnerable to the effects of natural disasters such as annual dry spells and flooding. Malawi’s economy is mainly informal and driven by rain-fed small scale subsistence farming and tobacco exports. Large parts of Malawi continue to suffer from food insecurity on an annual basis, particularly during the lean season due to high food prices and insufficient crop production (CitationCarr, 2004; CitationPeters, 2006; CitationChirwa, 2009). Most of smallholder farmers in Malawi focus on producing food staples such as maize and rice for own consumption and the sector remains unprofitable, characterized by a low uptake of improved farm inputs, weak links to markets, high transport costs, few farmer organizations, poor quality control and lack of information on markets and prices (CitationChirwa and Matita, 2012). The 2016 El Niño induced dry conditions and due to poor agricultural performance in combination with high food prices, it is estimated that the number of food insecure people by the end of 2016 and in 2017 increased to 6.5 million, up from the estimate of 2.84 million people in the previous year (CitationFAO Malawi Country Brief, 2016).

With the aim of stabilising food systems, a number of agricultural commodity exchanges and market information systems similar to ACE have been established in Sub-Saharan African countries, such as Malawi, Kenya, Uganda, Zambia, Nigeria, Ghana, Tanzania, South Africa and Ethiopia (CitationSitko and Jayne, 2012; CitationDemise et al., 2016; CitationGabre-Madhin and Goggin, 2005). Commodity exchanges are markets “in which multiple buyers and sellers trade commodity-linked contracts on the basis of rules and procedures laid down by the exchange” (UNCTAD, 2009:19). These markets are expected to “empower farmers”, “stimulate market transparency”, “reduce transaction uncertainty” and “support price discovery” (CitationUNDP, 2014; CitationUNCTAD, 2009; CitationRashid et al., 2010). Their establishment has often received international funding with the objectives of improving what, why and when farmers produce, consume and sell their crops in their pursuit of a livelihood (CitationUNDP, 2014; CitationUNCTAD, 2009; CitationRashid et al., 2010). Commodity exchanges are so prominent that they have been the object of multiple academic and policy evaluation studies.

Women in Malawi contribute considerably to the produce of the food and make up 50% of the agricultural labour force (CitationDoss, 2011; CitationPalacios-Lopez et al., 2015). Yet, they manage plots that are reportedly on average 20–30% less productive than those of men (CitationAli et al., 2016). It is well documented that women face more difficulty compared to men in accessing resources, productivity enhancing inputs and engagement with market systems (CitationBenería, 2007, 2015; CitationKaaria and Ashby, 2001; CitationNjuki et al., 2011; CitationEdriss and Kamvani, 2003). The main driver of the gender gap in agriculture is that women are assigned to domestic and care responsibilities which affect their productivity and access to farm inputs (CitationAli et al., 2016; CitationChirwa and Matita, 2012). Men commercialize more often than women because they have greater access and ownership of assets such as land and capital.

In Malawi gendered rules are used to organise “all forms of repetitive and structured interactions” in families, communities, organisations and markets across social, cultural, political and economic arenas” (CitationMinton and Knottnerus, 2008). Whereas under Malawi law, men and women are equal and have equal ownership and rights to property, gendered rules play out against women in the family and unequal access and control over resources are perpetuated as a result of gender beliefs about roles and responsibilities and customary law of both matrilineal and patrilineal systems (ILO, 2011). Tradition expects women to engage in certain types of activities and be obedient and submissive to the husband. She is expected to devote her time to managing the home and not to managing a business. “Such beliefs reinforce negative attitudes towards women in business and discourage women from starting or growing a business or opting instead for the traditional income generating activities that keep them at home such as raising chickens and goats, and small scale baking” (ILO, 2011). Rules define a division of labour in and out of the household, so “men gather firewood to sell and the women should gather firewood for the home” (Minton and Knottnerus, 2008: 201). Most women do not speak or write English −the main business language in Malawi- because there is hardly an incentive to enrol in secondary education where English is taught (CitationMinton and Knottnerus, 2008; CitationHanmer and Klugman, 2016).

As a result of a Western based development project, ACE was established in July 2004 “to bring more order to the market place” with a grant from USAID through the National Smallholder Farmers’ Association of Malawi (NASFAM).Footnote3 ACE is a “live exchange trading platform” that links farmers to markets in an attempt to support farmers in making better decisions of when to buy and sell commodities. ACE became operational in October 2006 and has since then facilitated the trade of over 300,000 metric ton of commodities, valued at US$ 109,000,000 (CitationACE, 2017). Nowadays, ACE is shifting from being an institution solely supported by public grants and subsidies, into an equity-based alliance, where also private actors can invest in. In order to empower smallholder farmers and stabilize commodity trade, ACE created a trading platform that guarantees payment through banks and has integrated warehousing receipt systems, quality standards with financing, training and ICT based mechanisms to disseminate real-time market information to buyers and sellers.Footnote4 ACE developed tailor-made software that can upload and share real time market information using laptops, mobile phones and radio. In 2012 the tailor made and newly developed web based software became fully operational.

ACE has market information points and about 50,000 farmers registered in the market information system and 43 warehouses throughout the country where farmers can store their commodities and access finance. The warehouses are mostly being used by buyers. ACE intends to “break down the barriers that prevent farmers from adopting structured trade” and empower smallholder farmers in negotiating better prices for their crops by providing them with timely and reliable market information, both pre- and post-harvest. Individually or in a group, farmers place their commodities into the ACE warehouse and after weighing and a quality assessment, receive a receipt together with a 70% loan that represents today’s worth value in the market. The loan intends to solve farmers’ immediate need for cash and give them “leverage to wait for a better price”. ACE warehouse stocks commodities from individuals and groups of farmers and uses its website and network to find buyers by offering large quantities of commodities. When a buyer is found, ACE informs the farmers about the price through radio, telephone and SMS. If the farmer decides to sell and the transaction goes through, they get another payment, for the total value minus the 70% loan, interest and storage fees.

ACE addressed “the farmer” as an ungendered position, so everyone who produces agricultural commodities could register. In relation to Ostrom’s types of rules (), ACE emphasis in on changing information and aggregation rules, so that every trader has access to more transparent information and could wait for a better price, thereby allowing sellers to get a higher profit and increasing control over their business. The payoff rules with ACE include warehousing fees, pre-payments with an interest and the goal of getting a higher price. In the next section we analyse these changes for men and women.

6 ACE new rules and women farmers

We will now analyse how the creation of a commodity exchange in the institutional field of the market has rippled on the household rules and affected, or not, the lives of women farmers. To guide our interviews, we operationalised the seven clusters of rules in Ostrom’s framework into corresponding groups of questions that would guide our interviews () and we report in detail on our data in annex 1.

Table 2 From framework to data collection.

We first corroborated the link between the two institutional fields (step 4 in our diagnostic tool) in order to understand in what ways the introduction of ACE changes the opportunities and constraints of women in their households. Women in Malawi are responsible for food security, and we found that the introduction of ACE has affected the way women farmers balance the needs of their households. A divorced woman described how she takes into account ACE when she manages her decisions on food and surpluses: “I first take out what we need for our own food. I then decide if I go to a local vendor or if I have enough and want to go with ACE. If I can wait a bit extra for the cash, I go with ACE. I go to the warehouse and then I wait for ACE to call me and hear about the price. I have three options. I loose, I play even or I profit. I calculate the invested labour and fertilizer and how much I need for family food, school fees and emergency money. If I reach a break-even point, I decide if I can wait just a little bit more. It is difficult because I need the cash for my family, I cannot afford to gamble on our livelihood. If I make profit, I can do a little bit extra”.

We then proceeded to explore the position rules that apply on women farmers in the market and household fields. For women farmers, we found that trading with ACE represents an accomplishment and improves her social status. ACE provides valuable feelings of recognition and affirmation of being “a business woman”, signalling female farmers as providers of income and valuable social and economic agents in their households. One woman told us: “ACE helps me to make informed business decisions which are atypical for a woman”. Moreover, the majority of the women received training with ACE that they would not have been able to access otherwise. Nine of the twelve women interviewed learnt to keep books and do some financial planning or budgeting. Women appreciated that ACE increases their business competencies and provides support with the roll-out of their business plans and offer trainings on agricultural technologies and business skills. We considered this change fit our definition of ripple effects: ACE improved the position of women farmers in the market, and that translated into a revamped position also in the household.

We then focused on the authority or choice rules that command actors and limit their autonomy in a position. Norms associated with patriarchy and especially the household rules restrict women's mobility and participation in public life, limiting their involvement in markets. ACE field officers explained to us that women have limited mobility to sell their produce. “It is seen as very inappropriate for women to travel to a market further away and having to stay there overnight. It will make her suspicious and she will be perceived as a cheating wife or worse, a prostitute. So she cannot sell her goods at another market”. We understood this as a rule in the household institutional field that restricts women’s actions in the market institutional field and restraints her actions as a business woman. ACE trades electronically, which introduced a new opportunity for women to achieve a better selling price without travelling. While ACE engages male and female farmers equally, men always accessed the benefits of travelling longer distances. We understood this change as positive for women but consistent with the existent household rules, so we did not consider it a ripple effect on the rules regarding women’s mobility.

ACE was primarily designed as a price discovery mechanism, so it redefined the information rules that guide decision-making about buying and selling. This institutional change has been appreciated by female farmers who often found themselves in a weaker position to bargain prices, weights and quality with the local middlemen. When asking women why they decided to trade with ACE and how it has affected their lives, they described an array of old and new constraints and opportunities. “ACE finds the market faster” or “before ACE, I didn’t know another market existed” were frequent heard phrases. Especially not experiencing the stress of having to find a buyer with insufficient information or deal with local corrupt vendors was mentioned repeatedly: “Before, I would only offer my commodities to the vendors here in my village, immediately after harvesting, but these ones kuba (steal). They tamper with the weighing scale”. Most women refer to ACE as trust-worthy “partner” and supporter: “I believe in ACE and have a long-term commitment with ACE”. The transformed information rules have also generated a positive effect for women in the field of the market, but they have not affected the household rules. We followed a similar reasoning as with the choice rules and did not characterise it a ripple effect.

Aggregation rules indicate who controls resources and these are most problematic for women in the market as well as in the household. In the market field, ACE aggregation rules centre on software to “facilitate up-to-date information so that farmers can make better decisions”. But we learnt from ACE staff that “85% of the producers are women but they do not register to get the information. Their husbands do. Women sometimes register but use their husband’s phone number, which they may sell when times are tough”. There are other reasons why women do not use or do not have access to the technology, like not owning a phone or the inability to read and write English text messages or no network. Except for one woman who went to secondary school, the women in our sample are low educated and English illiterate. So a minority of women actually have direct access to the market information facilitated by ACE technology.

In the institutional field of the household, we found quite a mix of situations. In terms of aggregation rules, control over resources remains largely in the hands of men. Wives are expected to contribute to the market-activities of their husbands by providing emotional, physical and financial support. One woman described to us: “My husband is just selling and buying. He is not a very good businessman. I am better at it. Sometimes he feels down, so I comfort him and give him advice on how to improve, but he rarely listens.” To keep his business going, he often requests his wife to give him the cash she earns with her farm. When we asked whether and how he also supports her she replied: “No, never. Not in the house, nor in my businesses. It makes me feel heartbroken. My husband is pulling me down”. Another married woman described: “In 2015, I used the loan I received from ACE to buy fertilizer. My husband kept on asking me to give him the cash, but I couldn’t. I had reinvested the money. One morning I found that he had stolen three bags of the fertilizer stored in the house and sold them. When I confronted him, he got so angry at me, because a woman is not supposed to disrespect her husband”. Her husband beat her up and the community advised her to be less vocal. In a household in which the husband has multiple wives, he allocates the cash from the ACE warehouse receipt to buy seeds and fertilizer for his other wife’s farm. Nevertheless, two other married women described a more mixed situation. Since the introduction of ACE, the husbands allow them to collect the warehouse receipts, which is a small opportunity that does not automatically imply further control over the cash they earn. A woman explained: “We decide together how to use the money from the receipt because we also work the farm together”.

The distribution of costs and benefits is regulated by payoff rules. In the market institutional field, ACE receives fees for its services so it generated extra costs but on the side of benefits ACE made farming slightly more profitable. Farmers benefit from new resources, skills, and expanded networks. Two married women think that the small extra profit in the market institutional field has allowed them to bargain a better situation in the household institutional field since the introduction of ACE. We considered that this slight change rippled from the market institutional field. However, other two women experienced no difference; they described to us an enormous domestic workload that they need to attend to next to managing the farm. Farming is the main source of income in their households, but in many cases they complement it with “business from the veranda” which means selling second-hand clothes and home-made food and drinks nearby the house.

We included in our framework a differentiation of the various positions among women, which has allowed us to find an effect that is not well-captured in Ostrom’s seven types of rules. That is, the introduction of ACE in the market institutional field enabled some women to control what position they occupy in the household field and to decide whether they want to be a married woman at all. The unmarried and single women underlined that ACE has been invaluable to their efforts to remain unmarried while retaining their children in single-headed households. For them a bit more profit represents an opportunity to secure and build-up the capital that they need to retain their household position instead of having to remarry. Depending on their health, the unmarried women indicated that they were free to decide on the strategy of the business, how to spend their time, on what activity, and how to allocate the resources that follow market-activity. One of the widows expressed to us: “If my husband were alive today I would not be a successful farmer because I would not be allowed to be a leader and make money”.

summarises the rules introduced by ACE in the market field that have affected women’s lives and allowed them to affect the rules in the household institutional field. The new choice rules and information rules in the market field increased their choices, hence granting them opportunities in the market field that men already had. However, the rules in the household were not changed, so we did not characterise these as ripple effects upon the household institutional field. We found ripple effects upon the household rules that were generally weak but nevertheless represented an improvement for some women farmers, particularly in terms of the position rules and payoff rules.

Table 3 In what ways has ACE affected rules in the households?

Our data suggested that the introduction of ACE has had weak but positive ripple effects for women in three ways: retaining freedom by avoiding an unfavourable married position in the household, promoting small improvements in the household rules and increasing benefits in the market institutional field without any ripple effect on household rules. The introduction of ACE allowed the interviewed women to adopt the position as “business woman”, which became important as a source of recognition and agency in the pursuit of more freedom and improved well-being. Some women in our sample, especially the unmarried ones, strategically stretch the household rules that define what is legitimate and appropriate for “a woman” and retain their position in single-headed households. ACE institutions have enabled them to strategize and ease the constraints to market engagement that come with “being a wife”. For unmarried women, ACE provides a conceivable opportunity to build-up capital on their own and to expand their business to delay or dodge marriage for themselves or for their daughters, because education enables girls and young women to “keep busy”.

None of the widowed and divorced women considered that remarrying was an option, even though they indicated that “not having enough hands” or “someone to share or do the work with” made life hard for them. They invariably expressed that remarrying means a risk of “not being free” in the sense of transferring control over the business and its revenue to the new husband. One divorced woman suggested: “There’s is no such thing as freedom in a marriage. I do not want to remarry because men steal your life”. Moreover, Chewa culture prescribes that Chewa men do not have to care for the children of another man, including that if he does not want her to pay for the education of her children from another marriage, she cannot do it. Another divorced woman explained: “I divorced because I wanted to break the cycle of poverty by someone (husband) stealing your life. My business now secures the livelihood of my family and children and ensures that they finish a good education”. The divorced and widowed women with children that we interviewed were not willing to take that risk, and that is where ACE facilitates their plans, by providing mechanisms to control the position they adopt in the household institutional field.

We also found mixed evidence that married women use the slightly increased profits and the improved status gained with ACE to affect the rule sin the household institutional field and bargain with their husbands. This was the case of two of the married women, in which the couple discussed and agreed on sharing work and income, a way of doing things such as working the farm together, sharing domestic tasks and decision-making. These are examples of the ways in which ACE introduced changes in the market field that undermined, however marginally, the gender institutions in the household field.

While we could not extend the analysis to other women farmers in Malawi, we found evidence that some women farmers recognise ACE as a mechanism that provides them with new opportunities to stretch the constraining household rules and facilitates access to advantages that men already had. Our dataset is too limited to make such claims and the methodology was not designed to assess impact, but is seems that the effects of ACE went beyond the planned genderblind market price discovery gathering mechanism. And, that more gender aware interventions of ACE that take into account the constraining rules for farmers at home, in farm groups and the market, may yield better outcomes for women farmers.

7 Discussion and conclusions

We aimed at contributing a tool to better understand in what ways ripple effects occur. We first conceptualised ripple effects and second developed a diagnostic tool to better trace, understand and follow them. We contributed a tool that unveils intricate interconnections among institutional fields and how these enable and constrain agents’ actions, following the ideas of scholars such as CitationOstrom (1990, Citation2007), CitationHodgson (2003, Citation2006), CitationFligstein and McAdam (2011a, b)Citation, CitationBourdieu and Wacquant (1992), CitationSmajgl and Larson (2007) and others. Our tool allows for an empirical analysis of the ways in which changes in one institutional field may trigger unanticipated ripples in rules in another institutional field.

Our tool was not designed to evaluate the impact of market innovations on women. Rather, it was designed to reveal the interwoven interactions and decisions in the daily lives of agents, across the different fields of the household, community and the market. This unveils processes that other studies miss because they focus on understanding effects of market innovations for a specific social group, such as women, and in one institutional field, e.g. the market. In such studies, agents’ interwoven actions in and from one to other institutional fields are assumed to be non-existent and ripple effects subsequently remain obscured and are overlooked.

We tested our tool in practice and focused on how the introduction of a gender blind new market institution in Malawi affected agents’ decisions and interactions across two institutional fields: the market and the household. We demonstrated that the tool can surface agents’ actions across different interwoven institutional fields and hence, analyse ways in which new market rules can have an effect beyond the activity of buying and selling. Applying the tool indicated that agents’ buying and selling actions in the market are dependent on the agency and control they have in other institutional fields, particularly in the household and in terms of marital status. Applying the tool also suggested that unintended changes in household rules may have occurred upon changes in market rules, demonstrating that the tool can detect subsequent transmission mechanisms. In our case that mechanism was via agents, whereby new market rules provide them with new opportunities to stretch the rules in other institutional fields. While ACE did not mean to affect gender rules in the household and basically ignored gender differences among farmers altogether, our findings suggest that women farmers may recognize in ACE and in markets an opportunity to stretch the constraints that come with ‘being a wife’.

Our conceptualisation of the ripple effects from one institutional field upon another shows that it requires us to think more about how new market institutions can be used to influence rules in other fields. Furthermore, our findings contradict the bias of much feminist literature that indicate that genderblind market reforms rarely if ever serve a feminist project. The here presented tool allows for a more nuanced empirical analysis beyond the conviction that gender-blind market reforms cannot benefit women. It assumes that entrepreneurship is more than an economic activity, because it can also serve to stretch gender norms in the household institutional field, as hinted by CitationCalas et al. (2009). We also stand with CitationScott et al. (2012) and their argument for more comparable research to understand the transmission mechanisms between institutional fields.

Our study shows that there are many ways to reach a solution and that understanding ripple effects from the market institutional field to the household is critical. Especially at a time where the transformation of gender inequalities in household rules are the subject of a myriad of policies with the aim to empower women and achieve social justice. Such policy solutions of creating more egalitarian rules in households have perhaps rendered limited results because some of these rules are extremely resistant to change. From a policy perspective, we are inspired by the notion that our tool suggests that changing gender inequalities in household rules, can be obtained with less effort and by changing rules in the market that are likely to produce ripple effects. This way shifting the policy focus from targeting women famers within households, or the so called gender-neutral farmer in the market, to rule-guided market policies that aim to expand opportunities for agents across institutional fields and equip agents with new resources that allow for rippling constraining gender rules at home, in the community and the market.

Our method proved to be limited in capturing pace, direction, scale and diversions of the ripple effects in the longer run. Further research should focus on other institutional fields, in which Ostrom’s framework can be used to identify the various types of rules and differentiate positions occupied by agents. A comparative analysis is needed to gain insight in the longer term consequences of rules on agency and subsequent effects on rules in other institutional fields. Understanding the scale, scope and pathways of ripple effects requires further research whereby longitudinal, mixed method approaches and integrated evaluations seem best suitable.

Acknowledgements

We thank our research assistants Tanja Hendriks from African Studies Centre, Aubrey Chaguzika from LUANAR University and Lifa Kainja Hallow for their valuable insights, contributions and translations during the data collection process. We thank the Centre for Frugal Innovation in Africa (CFIA) for their financial support during the field work phase. We thank the editors of this special issue and the blind reviewers for their valuable comments and feedback during the writing process. We particularly would like to express our gratitude to all the women and men smallholders that participated in this study for dedicating their time, welcoming us into their homes and share thoughts, feelings and experiences. We especially thank ACE staff for their openness and all the information that was shared and their logistical assistance during the field work.

Notes

1 The data we present here comes from a larger research project on the effects of inclusive innovations on the lives and businesses of women entrepreneurs in Malawi that included a round of data collection by one of the authors between February and May 2016 and February and March 2017.

2 It was ranked 171 st out of 187 on the 2011 UNDP Human Development Index and 45th out of 79 on the 2012 Global Hunger Index. Over 40 percent of the country’s 14 million people live on less than US$1 per day and 67 per cent of those below the poverty line are women (CitationUNDP, 2014).

3 NASFAM is a farmer based organization spearheading the commercialization of smallholder farming.

4 In 2010 funding from The Competitiveness and Trade Expansion (COMPETE) program of USAID enabled ACE to make a restart and set-up the Warehouse Receipt System, a market information system to enable real-time commodity price discovery. At the same time The World Food Program (WFP) created an initial demand by procuring maize through ACE which generated a much needed pull in the market.

References

- ACE, Our Past, Present and Future. Presentation for development partners, February 2017.

- D.AliD.BowenK.DeiningerM.DuponchelInvestigating the gender gap in agricultural productivity: evidence from UgandaWorld Dev.872016152170

- K.AnderssonA.AgrawalInequalities, institutions, and forest commonsGlobal Environ. Change2132011866875

- L.BeneríaGender and the social construction of marketsFeminist Economics of Trade2007RoutledgeLondon and New York1332

- P.BourdieuL.WacquantInvitation to a Reflexive Sociology1992University off Chicago PressChicago

- M.B.CalasL.SmircichK.A.BourneExtending the boundaries: reframing entrepreneurship as social change through feminist perspectivesAcad. Manage. Rev.3432009552569

- S.CarrA brief review of the history of Malawian smallholder agriculture over the past fifty yearsSoc. Malawi J.57220041220

- E.ChirwaThe 2007–2008 food price swing: Impact and policies in MalawiCommodities and Trade Technical Paper 12 (2009) FAO.

- E.W.ChirwaM.MatitaFrom Subsistence to Smallholder Commercial Farming in Malawi: A Case of NASFAM Commercialisation Initiatives2012

- T.DemiseV.NatanelovW.VerbekeM.D’HaeseEmpirical investigation into spatial integration without direct trade: comparative analysis before and after the establishment of the ethiopian commodity exchangeJ. Devel. Studies2016119

- C.DossThe Role of Women in Agriculture. ESA Working Paper No. 11-02; March 20112011Agricultural Development Economics Division, The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations(www.fao.org/economic/esa)

- C.DossIf women hold up half the sky, how much of the world’s food do they produce?Gender in Agriculture2014SpringerNetherlands6988

- A.K.EdrissE.KamvaniSocio-economic constraints women face when running micro-enterprises: a comparative case study in Southern MalawiEastern Africa J. Rural Devel.19120034151

- FAOCountry Brief Malawi2016(http://www.fao.org/giews/countrybrief/country.jsp?code=MWI)

- N.FligsteinD.McAdamToward a general theory of strategic action fieldsSociol. Theory2912011126

- N.FligsteinD.McAdamA Theory of Fields2011Oxford University Press

- E.Z.Gabre-MadhinI.GogginDoes Ethiopia Need a Commodity Exchange? An Integrated Approach to Market Development2005Addis Ababa : Ethiopian Development Research Institute(Working Paper Series, 4)

- L.HanmerJ.KlugmanExploring women's agency and empowerment in developing countries: where do we stand?Feminist Econ.2212016237263

- G.HodgsonThe hidden persuaders: institutions and individuals in economic theoryCamb. J. Econ.272003159175

- G.HodgsonWhat are institutions?J. Econ. Issues4012006125

- S.K.KaariaJ.A.AshbyAn Approach To Technological Innovation That Benefits Rural Women: The Resource-To-Consumption System. Working Document No. 132001PRGA ProgramCali, Colombia

- E.O.LaumannD.KnokeThe Organizational State: Social Choice in National Policy Domains1987University of Wisconsin pressMadison

- W.W.MadduxM.YukiThe ripple effect: cultural differences in perceptions of the consequences of eventsPers. Soc. Psychol. Bull.3252006669683

- L.McCallThe complexity of intersectionalitySigns: J. Women Cult. Soc.30200517711802

- E.McKennaThe Task of Utopia: A Pragmatist and Feminist Perspective2001Lanham, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers

- C.A.MintonJ.D.KnottnerusRitualized duties: the social construction of gender inequality in MalawiInt. Rev. Modern Sociol.2008181210

- J.NjukiS.KaariaA.ChamunorwaW.ChiuriLinking smallholder farmers to markets, gender and intra-household dynamics: does the choice of commodity matter?Eur. J. Devel. Res.2332011426443

- E.OstromGoverning the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action1990Cambridge University PressNew York

- E.OstromUnderstanding Institutional Diversity2005Princeton University PressPrinceton

- E.OstromMultiple Institutions for multiple outcomesA.SmajglS.LarsonSustainable Resource Use: Institutional Dynamics and Economics2007EarthscanLondon2350

- A.Palacios-LopezL.ChristiaensenT.KilicHow Much of the Labor in African Agriculture Is Provided by Women?. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (7282)2015

- A.ParkenA multi-strand approach to promoting equalities and human rights in policy makingPolicy Politics38120107999

- P.E.PetersRural income and poverty in a time of radical change in MalawiJ. Devel. Studies4222006322345

- M.PolskiE.OstromAn Institutional Framework for Policy Analysis and Design1999(Available at: https://mason.gmu.edu/?mpolski/documents/PolskiOstromIAD.pdf)

- W.W.PowellD.R.WhiteK.W.KoputJ.Owen-SmithNetwork dynamics and field evolution: the growth of interorganizational collaboration in the life sciencesAm. J. Sociol.1104200511321205

- S.RashidA.Winter-NelsonP.GarciaPurpose and Potential for Commodity Exchanges in African Economies2010International Food Policy Research Institute

- D.RodrikDiagnostics before prescriptionJ. Econ. Perspect.24320103344

- D.RodrikDiagnostics before prescriptionJ. Econ. Perspect.24320103344

- L.ScottC.DolanM.Johnstone-LouisK.SugdenM.WuEnterprise and inequality: a study of avon in South AfricaEntrepreneur. Theory and Practice3632012543568

- C.H.SeigfriedPragmatism and Feminism: Reweaving the Social Fabric1996University of Chicago PressChicago

- A.SindzingreThe relevance of the concepts of formality and informality: a theoretical appraisalB.Guha-KhasnobisR.KanburE.OstromLinking the Formal and Informal Economy: Concepts and Policies2006Oxford University Press, UNU-WIDER Studies in Development Economics and EGDIOxford

- N.J.SitkoT.S.JayneWhy are African commodity exchanges languishing? A case study of the Zambian Agricultural Commodity ExchangeFood Policy3732012275282

- A.SmajglS.LarsonInstitutional dynamics and natural resource managementA.SmajglS.LarsonSustainable Resource Use: Institutional Dynamics and Economics2007EarthscanLondon319

- UNCTADReport on the UNCTAD Study Group on Emerging Commodity Exchanges: Development Impacts of Commodity Futures Exchanges in Emerging Markets. Geneva, Switzerland2009(http://unctad.org/en/Docs/ditccom20089_en.pdf)

- UNDP2014 Millennium Development Goal Report For Malawi2014(http://www.undp.org/content/dam/malawi/docs/general/Malawi_MDG_Report_2014. pdf)

- L.WacquantPierre bourdieuR.StonesKey Contemporary Thinkers1998Macmillan Education UKLondon and New York215229

- J.WhippsD.LakePragmatist feminismE.N.ZaltaThe Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy2016

Appendix A

see