Highlights

| • | Institutional logics and bricolage used to analyse development partnerships. | ||||

| • | Partnership initiators integrate market logics as required by donors. | ||||

| • | Field level implementers balance markets logic with grassroots development logics. | ||||

| • | Newly introduced logics are mitigated by rigidity of existing local structures. | ||||

| • | Institutional diagnostics enables development actors to assess room for manoeuvre. | ||||

Abstract

Trade globalisation and climate change pose new challenges for food security in Africa. To unlock smallholder productivity, more understanding is needed of the institutional context and the role of development interventions, such as partnerships, in the food sector. This article proposes institutional logics as a theory and methodology for institutional diagnosis to gain insight into context-embedded negotiation and change processes created by project-based partnership interventions. We analyse the institutional logics of organisations active in the development of two value chains in Ghana to subsequently show how, in partnerships, these logics are negotiated in light of the objectives and interests of the intervention. The main findings are that donors, with their market and professionalisation logics, are quite influential, but many other development actors still adhere to principles of grassroots empowerment and social security. In the evolving partnership process, market logic remains strong, but coupled with institutional logics endorsing farmer empowerment and solidarity with the resource-poor. This is done in a process of bricolage in which field level implementers go against the dominant logic of project initiators: showing that newly introduced development logics are mitigated by an existing local structure fostering other development logics. The broader implication is that new development paradigms may need a considerable transition period to become mainstream. The concepts of institutional logics and bricolage as a diagnostic tool allow researchers to characterise the adherence to and blending of institutional logics by actors. This tool helps to understand the mobilisation strategy of the initiator and to follow the negotiation of logics that takes place amongst partners in partnerships. Detailed insights into the blending of potential partners’ logics, pathways of negotiation processes and the plausible outcomes enable development practitioners to strategically prepare and manage their collaborative interventions.

1 Introduction

Many Africans face food security challenges (CitationRosegrant and Cline, 2003; CitationSpiertz and Ewert, 2009; CitationGodfray et al., 2010); this implies that not everyone always has access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active healthy life (CitationMwaniki, 2006; CitationGarrity et al., 2010). The situation is worrying, as the potential to produce more food for an ever-growing African population is declining: current projections show that higher temperatures and lower rainfall trends combined with a doubling of the population will lead to a 43% increase in food insufficiency (CitationFunk and Brown, 2009; CitationSEI, 2005). New technologies as embodied in high yielding cultivars and good agronomic practices have not been sufficient to reduce food insecurity (CitationRöling, 2009). To make matters worse, food production in Africa is largely dependent on resource-poor smallholder farmers and ineffective value chains. These value chains are embedded in institutional contexts, some of which constrain farmers from capturing the full benefits of technological interventions (Röling, 2009;CitationNederlof et al., 2007; CitationStruik et al., 2014Citation). For example, farmers are not well organised and have little power. Research is supply-driven; public service delivery and input provision have collapsed as a result of structural adjustments policies; and local governments, traders and middlemen raise revenue from agricultural production to the detriment of farmers (CitationVan Huis et al., 2007). In such institutional contexts, farmers have small windows of opportunity (CitationNederlof et al., 2007).

Multi-actor partnerships are increasingly promoted to create innovation for smallholder farmer development and improve food security, and to ensure the co-evolution of technological and socio-institutional change (CitationBitzer et al., 2008; CitationKilelu et al., 2013). These multi-actor partnerships have been captured under different terminologies such as innovation configurations (CitationEngel, 1995), coalitions (CitationBiggs, 1990), cross-sector partnerships (CitationDentoni et al., 2016), innovation platforms (IPs) (CitationNederlof et al., 2007) and public–private partnerships (PPPs) (CitationSpielman et al., 2010). Although the potential of these types of partnerships for smallholder development in food value chains has been emphasised (CitationKlerkx and Leeuwis, 2009; CitationWorld Bank, 2007), and research has been done on how they promote institutional change in the development sector and food value chains (e.g. CitationBitzer et al., 2008; CitationKilelu et al., 2013; CitationManning and Roessler, 2014), little is known about the driving forces behind their organisation and how these evolve over time.

Various authors have highlighted the importance of understanding meaning-making and practice in multi-agency aid chains (CitationLewis et al., 2003; CitationMosse, 2004; CitationBebbington et al., 2007; CitationMorrison, 2010) to provide policymakers and development practitioners with management advice (CitationLewis et al., 2003; CitationMosse, 2004). So far, most studies have focused on the collaboration between donors and implementing NGOs, but little attention is given to new hybrid collaborations, such as multi-actor partnerships. Furthermore, studies on meaning-making in development collaborations tend to take ethnographic and discursive perspectives and focus on a specific level of interaction: international, national or local (CitationLewis and Mosse, 2006).

However, for multi-actor partnerships, it is not clear what institutional logics (e.g. norms, values, incentives, procedures) different partners adhere to and how they bring these to bear in the partnership, when negotiating the partnership objectives, activities and implementation (CitationLeeuwis, 2000), thus ultimately influencing the outcomes of the work done in the partnership. Sometimes, a partner in the partnership may find that the development objectives challenge its own logic, as the scope of change proposed may be systemic (CitationFuenfschilling and Truffer, 2014).

Thus, in line with the focus of this special issue (CitationSchouten et al., 2017), we apply a multilevel institutional logic perspective, as it explicitly pays attention to the influence of the institutional context on the negotiation of meaning and the legitimation of practices. We look at the differentiation, fragmentation and contradiction of institutional logics in multi-actor partnerships and unravel through the lens of institutional bricolage how the negotiation process that ensues from different institutional logics shapes interventions to create change in the food sector in Ghana. As diagnostic methodologies to explore pathways of institutional change are still lacking in the agricultural development literature (CitationSchouten et al., 2017), our perspective can provide detailed insights into the blending of development partners’ logics and negotiation process pathways. This can enable development practitioners to better prepare and manage the initiation and collaborative intervention of multi-actor partnerships.

The paper continues with a brief outline of the concepts of institutional logics and institutional bricolage. Then, we demonstrate the use of this analytical framework for the case of partnership-based interventions in the staple food sector of Ghana, focusing on soybean and cassava value chains. Finally, conclusions are drawn about the value of the institutional logics and bricolage perspective as a diagnostic tool to assess partnerships.

2 Conceptual framework

In this section, we outline the analytical lens used to analyse the context-embedded meaning-making in partnerships, regarding their development interventions in the food value chain. We briefly explain the theory of institutional logics linked to institutional fit (congruence of logics between actors and the proposed joint action) and bricolage (blending of logics).

Institutions integrate organisations and communities through universalistic rules, contracts and authority (CitationParsons, 1951), and these are thus what have been called ‘the rules of the game’ (CitationNorth, 1990). The institutional logics concept focuses on the content and meaning of institutions and shows that institutions regularise behaviour while at the same time enabling agency and change (CitationThornton and Ocasio, 1999). In line with CitationThornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury (2012: 2), we define institutional logics as ‘the socially constructed, historical patterns of cultural symbols and material practices, including assumptions, values, and beliefs, by which individuals and organisations provide meaning to their daily activity, organise time and space, and reproduce their lives and experiences.’

A key assumption is that institutional logics shape, and are shaped by, the behaviour of individual and organisation actors (CitationThornton and Ocasio, 2008) whose institutional logics in multi-actor partnerships differ, depending on where they are positioned in a societal sector, as each has a core set of institutions or even can be considered an institution (CitationFriendland and Alford, 1991; CitationThornton, 2004). In the African staple food sector, we could think of families, the market, the bureaucratic state, research and the development sector, in which certain logics guide, legitimise and constrain meaning-making and practices at individual, organisation and sector level. Within a sector, there may be single, multiple and/or hybrid institutional logics (CitationMars and Schau, 2017: 5). Single logics are those that come to dominate a particular sector, and in doing so bring uniformity and longevity to field-wide practices (CitationLounsbury, 2007). Examples are market logics and state logics that retain a sector-wide commitment. Multiple logics on the other hand are logics that co-exist, and in some cases compete, within a common sector, leading to practice variation and segmentation (CitationLounsbury, 2007; CitationPurdy and Gray, 2009). Blended or hybrid logics are those that emerge through the melding of elements from multiple logics (CitationRao et al., 2003; CitationMars and Lounsbury, 2009).

Differences in institutional logics may influence what has been named ‘institutional fit’, which is about the congruence of institutional logics adhered to by the different actors and the logic proposed for the joint action (CitationYoung, 2010; CitationSchouten et al., 2016). However, given that in partnerships actors with often different interests and backgrounds come together (CitationGlasbergen, 2007), such institutional fit is generally not a given and requires negotiation. Such a negotiation process can be seen through the lens of institutional bricolage, which is about consciously or unconsciously ‘piecing together’ new practices and institutions from different elements of existing institutions (CitationLevi-Strauss, 1966). Actors creatively combine practices and institutional logics from different societal actors. Emerging sets of ideas are not always a coherent whole, but are hooked on to older ideas, moulding them in such a way that they gain partners’ acceptance (CitationCarstensen, 2011). Bricolage processes are often linked to practical problems (i.e. the issue being addressed by the partnership at a particular juncture) and must somehow resonate with the logics of other actors to secure legitimacy and political support for the new proposed course of action (CitationDe Koning and Cleaver, 2012). Depending on their interests and power relations in the partnership, other actors will modify (alteration), accept (aggregation) or reject (formulation) the proposed practice and underlying logics (CitationCleaver, 2002; CitationCleaver and De Koning, 2015).

As a diagnostic tool for institutional analysis − one of the goals of this special issue (CitationSchouten et al., 2017) − looking at the presence or the absence of institutional fit can help to assess the likelihood of certain partners collaborating with each other; the required negotiation between them; and the resulting logic of the collaborative action. By analysing the process of bricolage between partners initiating, joining and implementing development interventions, researchers can track the influence that each of the partners and the farmer recipients exert in defining the actual practice and outcome. The above leads to a number of diagnostic questions:

| 1. | To what types of institutional logics do different partnership actors adhere and bring into partnerships? | ||||

| 2. | What direction and entry point for the development intervention do partnership actors propose and how does this link to their institutional logics? | ||||

| 3. | What is the institutional fit given the institutional logics of different actors involved in the partnership and the approach for the proposed development intervention? | ||||

| 4. | What type or types of bricolage occur in the different project phases (initiation, formulation and implementation of development interventions)? | ||||

3 Research method

3.1 Study design

Like CitationFuenfschilling and Truffer (2014), we opted for a qualitative approach to explore institutional logics. Qualitative research enabled us ‘to clarify the nature and interrelationship of the different contributory influences’ (CitationRitchie and Lewis, 2003: 216). Institutional change is a complex matter and very challenging to analyse; hence, a practical way is to apply a case study approach for in-depth and context-specific analysis (CitationYin, 2009). To understand the negotiation of development intervention logics in two different partnership arrangements in the Ghanaian food sector, we diagnosed the institutional logics of key actors and followed the process (CitationHall et al., 2014).

Two different kinds of partnership concepts that have become prevalent in Ghana as intervention approach were used as case studies (CitationKilelu et al., 2013): public–private partnerships (PPPs) and innovation platforms (IPs). PPPs are collaborative arrangements in which actors from two or more spheres (public, private, NGO) are involved in creating sustainable development. The actors collaborate on the basis of commitments that are formalised to a certain extent, with problem-solving tasks partially or exclusively accomplished by private partners (CitationGlasbergen, 2007). IPs are multi-actor configurations set up to undertake activities around identified agricultural innovation challenges and opportunities in the value chain, are often induced by research and can also be more informal (CitationKilelu et al., 2013), and their composition can change as issues to be solved change during the development intervention (CitationLamers et al., 2017).

3.2 Description of the case studies

1. The PPP soybean project Towards Sustainable Clusters in Agribusiness through Learning in Entrepreneurship (2SCALE) (2012–2017)

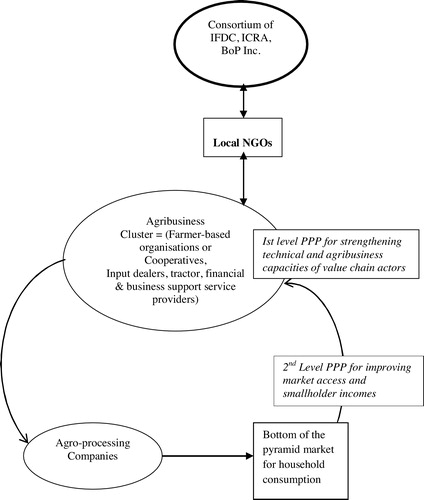

The 2SCALE soybean partnership was initiated by an international development organisation the International Fertiliser Development Centre (IFDC) in collaboration with the International Centre for development oriented Research in Agriculture (ICRA), an international capacity development organisation, and Base of Pyramid (BoP) Innovation Centre, an international local market initiative organisation. They formed a consortium that formulates new institutional arrangements (e.g. collective selling of soybeans through alternative market sources) and contracted selected local NGOs to implement these for soybean value chain transformations. The local NGOs implemented market access interventions. The project was funded by the Dutch government. The project used a PPP approach at two levels and aimed to strengthen smallholders’ capacity in soybeans production, processing and agribusiness, to improve their livelihoods and enhance food and nutrition security. shows the actors involved at the different levels of the partnership and their linkages.

The first PPP level was an agribusiness cluster, made up of small-scale enterprises (tractor services, input dealers), farmer-based organisations or cooperatives, financial service provider and business support service coach (officer from local NGO). The second PPP level was between an agribusiness cluster and private sector agri-processing companies (buyers of soybeans) and so-called bottom-of-the-pyramid consumer markets.

2. The IP cassava project Dissemination of New Agricultural Technologies in Africa (DONATA) (2011–2014).

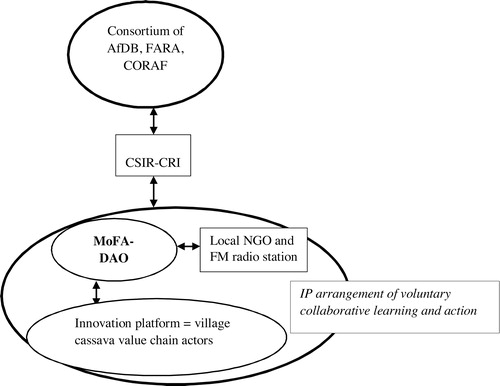

DONATA was an initiative of African Heads of State under the Promotion of Science and Technology for Agricultural Development programme in Africa. The project was funded by the African Development Bank (AfDB), managed by CORAF and FARA (research & development organisations), in collaboration with the Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA) and the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research-Crops Research Institute (CSIR-CRI). It used the IP approach and aimed to disseminate technologies and improved cassava varieties to increase productivity and enhance food security. Through a focal person from CSIR-CRI, the consortium was linked to the District Agricultural Office (DAO) of the MoFA (). At local level, the project operated through IPs as multi-actor configurations between local value chain actors (farmers, processors, local market buyers, transporters and input dealers). The MOFA-DAO served as the local implementing partner with responsibility for facilitating and organising training support for the IP.

3.3 Sampling

After a general inventory of partnerships in the food sector, 2SCALE in the northern region and DONATA in the Brong Ahafo region were purposively selected because of their high interest in addressing food security in Ghana. Our sample includes only the actors or organisations engaged in partnerships for development of food value chains. We focused on a selected sample of actors () involved in initiation, formulation of the partnership and enactment of their development objectives.

Table 1 Project actors sampled.

3.4 Data collection

Data were collected between January 2015 and August 2016, using multiple methods of desktop reviews, interviews and focus group discussions to triangulate the information gathered and enhance the validity and reliability of the study (CitationYin, 2009). We first studied the policy context of, and development actors in, the food sector in Ghana through extensive literature review to identify institutional logics and the blends of institutional logics of important development actors participating in the partnership. Project documents from the PPP (2SCALE) and the IP (DONATA) were also reviewed to identify the blend of institutional logics of the partnership initiators, the proposed project and the subsequent negotiation of logics that took place over time.

In addition, data were generated primarily through in-depth, semi-structured face-to-face interviews with the sampled actors (). The interviews, which lasted between 45 and 90 min, were intended to identify and describe the different actors’ values, norms and interests. To this end, an interview protocol using the conceptual constructs of institutional logics, bricolage and institutional fit was developed and used to guide the interviews. We were particularly interested in learning about how the actors made sense of the development intervention proposed for the two value chains under study. We also asked the actors to describe their own practices, norms, perspectives and values (as institutional logic elements) specific to the cassava or soybean value chain, their understanding of the new value chain arrangements introduced by the partnerships and their relationship to them.

Through the in-depth interviews with the key actors, we traced back the institutional logics, the institutional fit of logics between actors, and the bricolage practices during (a) the formulation and (b) the implementation of the partnership activities. Special attention was paid to the reasoning and discourse used at the interviews, as actors tend to strategically use pieces of discourse in change processes to convince others about the value of a certain institutional logic (CitationFuenfschilling and Truffer, 2014). For triangulation and more in-depth understanding of the process, variation in reasoning behaviour, institutional logics and bricolage practices, four different focus group discussions were held with female farmers, male farmers, cassava IP actors and cassava processors. This was coupled with participant observation during production activities on farmers’ fields, at local processing sites, and at IP and agribusiness cluster meetings.

All interviews and discussions were tape-recorded and fully transcribed for analysis. Initial findings of the research were presented at two different knowledge sharing workshops for validation by diverse actors from the MoFA, donor and development organisations, local NGOs, farmer-based organisations (FBOs), researchers and private sector companies.

3.5 Data analysis

To be able to characterise institutional logics of partnership actors and changes therein, we first identified the institutional logics in the staple food sector under study in which the cassava and soybean value chains were embedded. Like other studies on institutional logics, we used an inductive approach to carefully analyse actors’ discourse and behaviour. From this empirical data, ideal types of institutional logics were constructed. Ideal types are deliberate simplifications of a particular meaning scheme that can be used as yardsticks to compare and contrast meaning-making (CitationThornton and Ocasio, 2008; CitationFuenfschilling and Truffer, 2014). They enable the researcher to assess the level of adherence (prioritisation) to specific institutional logics and the modification in reasoning and practice that occurs.

4 Results

4.1 Staple food sector development and policy context

Literature research on the evolution of development policies and practices in the staple food sector in Ghana revealed a situation of multiple dominant development logics, their differentiation and contradictions. It showed the prominence or relative absence of different actors such as the national government, international and bilateral donors, NGOs, private actors, financial institutions and agricultural researchers. The government tends to prioritise policy and investment efforts in the agricultural exports sector as opposed to staple foods for domestic consumption (CitationSenadza and Laryea, 2012; CitationResnick, 2016). Little attention is given to agricultural diversification and the development of an agri-processing industry to promote trade (CitationKolavalli et al., 2012; CitationSenadza and Laryea, 2012). In the staple food sector, there are no pro-active policies and government coordination of projects, alignment with private actors or sustainable investment to build the capacity of FBOs at all levels (CitationSenadza and Laryea, 2012; CitationSEND-Ghana, 2015). Government provision of free handouts (fertilisers and seeds) impacts negatively on private sector and farmer business initiatives (CitationResnick, 2016). Bilateral donors consider social protection and food security logics, but increasingly embrace a market logic and focus on market development interventions. They reinforce their relationship with international companies from their home country and stimulate them to invest in agriculture to ensure sustainable sourcing (export crops). National private companies demonstrate more real concern for local development but often do not have the capacity to become involved. Financial institutions pursue market logics and perceive agriculture as a relative expensive and risky sector. NGOs that keep their focus on grassroots development, poverty alleviation or ecological sustainability increasingly depend on funding from private gifts or integrate market thinking to legitimise their activities and sustain their collaboration with donors. Meanwhile, some agricultural researchers acknowledge the limitation of the linear R&D approach and have become interested in multi-stakeholder IPs. This is because the institutional conditions of value chain actors limit the input investment and yield of promoted high-yielding hybrid crop varieties. However, most research and extension activities continue to focus on a general professionalisation of farming based on good agricultural practices through group training with field demonstrations.

To be able to characterise the blended institutional logics of organisations and change, we elaborated the ideal types of key institutional logics as presented in . These ideal type logics − state bureaucracy logic, market logic, grassroots empowerment logic, multi-stakeholder learning logic, professionalisation logic and social protection logic − were derived from the main discourse elements used by the actors in the documents and interviews (CitationFuenfschilling and Truffer, 2014).

Table 2 Multiple core institutional logics present in the food sector in Ghana and underlying elements (values/beliefs/assumptions/rules/material practices).

We used these ideal types to characterise the logics of the discourse and behaviour of the partnership actors and beneficiaries. The categorisation of farmer beneficiaries was also simplified and merely defined in a way consistent with the core logics and rationalisation of action. Data showed that resource-endowment, especially land property rights, was the main defining criteria of action paths.

4.2 The 2SCALE PPP in the soybean value chain

Pre-2SCALE: The fit of institutional logics and ensuing bricolage of the project initiators

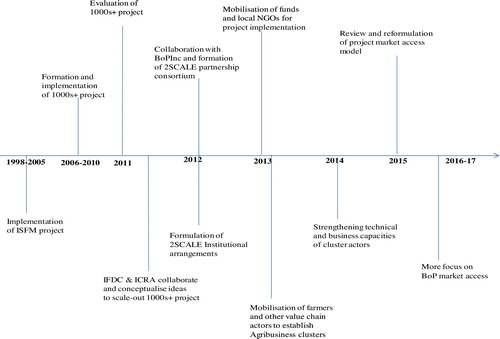

The 2SCALE soybean partnership project in Ghana is a follow-up of the From Thousands to Millions (1000s + ) project that IFDC and ICRA implemented between 2006 and 2010 under the Strategic Alliance for Agricultural Development in Africa (SAADA) programme.

IFDC is an organisation that promotes professionalisation of the agricultural sector in Africa. Around the year 2000, when the international development debate focused on institutional issues, IFDC realised that the improved production stimulated by their Integrated Soil Fertility Management (ISFM) Project (1998–2005) was offset by falling product prices. To create the market conditions needed to increase farm production, they started the 1000s+ project, prioritising market logic: ‘To induce smallholder development, it was necessary to take a Competitive Agricultural Systems and Enterprises (CASE) approach.’

IFDC engaged ICRA for the project training activities. There was no real fit of logics between these organisations. IFDC adhered to an agricultural professionalisation and free market logic while working with rural smallholders. ICRA prioritised multi-stakeholder learning, working with the free market logic but with a focus on food security (social protection logics) (see ). The difference in logic prioritisation could be explained by the different role played by the two organisations in development intervention. ICRA engagement in 1000s+ led IFDC to loosely couple the professionalisation logic (using expert knowledge) with the multi-stakeholder learning concept; this created more space to include grassroots and experiential knowledge. The IFDC director noted: ‘We felt first of all we should listen to the stakeholders in the field, and, secondly, to have a chance for sustainable development, local champions are needed for a micro-economics inclusive business model’ (project initiator).

Table 3 Institutional logics of IFDC, ICRA and joint enactment of 1000s+ project.

The partnership history () shows the different phases of activities that evolved from the 1000s+ project to the implementation of 2SCALE interventions.

Initiation of 2SCALE: The fit of institutional logics and subsequent bricolage amongst consortium partners in 2SCALE

When considering the next phase of the 1000s+ project, the project initiators, based in Accra, contacted the Dutch donor (DGIS) for funding. The Dutch agricultural economic research institute, LEI, was contracted for the 1000s+ project evaluation. It assessed the project in the light of the donor’s market logic and judged the relevance and effectiveness of the 1000s+ project as high, but its efficiency could be improved by scaling up the intervention. The difference in logics between the donor and the 1000s+ project was significant, but there was quite some fit of logics between IFDC and the donor, and funding would mean a considerable expansion of outreach in Africa. Despite the donor’s prioritisation of ‘Aid for Trade’, it seemed willing to fund a project in the local food sector; hence, IFDC/ICRA altered the 1000s+ logics to increase efficiency. They now prioritised free market logics and creatively coupled the idea of market clustering. The proposed 2SCALE (2012–2017) aimed to go ‘to scale, by increasing the number and the size of agribusiness clusters and enlarging the impact on food security by tripling the number of smallholder farmers involved’ ((CitationIFDC/2SCALE, 2012). For the soybean value chain in Ghana, this meant 2SCALE would work on FBO capacity building and the creation of contractual cluster arrangements between FBOs, traders, financial institutions and tractor service providers. Although the donor generally preferred a professionalisation logic, it allowed IFDC/ICRA to continue their FBO grassroots development logic, building FBOs’ capacities. They would have liked international companies to become involved, but this did not materialise as the latter had no interest in Ghana’s soybeans. Hence, both IFDC/ICRA and the Dutch donor altered their logics to legitimise collaboration in 2SCALE (see ).

Table 4 Institutional logics of the Dutch Donor, BoPInc and the proposed 2SCALE project.

Inspired by the book, The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid (CitationPrahalad, 2010), the ICRA director also invited BoPInc to join the project consortium. BoPInc is an independent foundation stimulating ‘commercially and socially viable business models, which include the people in the BoP as consumers, producers and entrepreneurs in the supply chain.’ BoPInc provides ‘design expertise, market insights and entrepreneurial guidance to develop solutions for BoP markets.’ It supports entrepreneurs and organisations through the innovation process, reducing complexity and risks. The director perceived a fit between the BoPInc logics and the 2SCALE cluster logic (market orientation, with consideration for BoP actors). The market and professionalisation logics of BoPInc resembled those of IFDC, but they focused on the marketing business domain (see ). BoPInc’s inclusion implied a stronger 2SCALE market and professionalisation perspective, but ensured more explicit coverage of the BoP producer and consumer needs. Aggregation of BoP ideas enabled 2SCALE to create a BoP soybean khebab niche market and better serve the social protection values (see ).

In the opinion of the IFDC 2SCALE soybean assistant cluster manager, the main value of the project was ‘to create agribusiness clusters and strengthen the provision of services and coaching for farmer organisations’/cooperatives’ capacity building.’ 2SCALE wanted to establish partnership contracts with the farmer cooperatives as private actors, but, as most of them did not yet have strong organisational and financial bases, the cluster managers contacted local NGOs engaged in farmers’ capacity-building activities. In northern Ghana, the soybean value chain was identified as viable for the cluster approach. The local faith-based NGO EPDRA and the empowerment NGO SEND − engaged in expert-based agricultural advice and cooperative capacity building − were invited to make proposals. These proposals were further elaborated in a design workshop where the NGOs met potential cluster partners such as credit institutions, input providers, soybean traders and processors. 2SCALE drew up contracts in line with the elaborated cluster action plans. The NGOs were happy to engage, as the proposed FBO capacity building fitted their agricultural and business professionalisation and cooperative development logics, and would provide substantial financial resources to sustain and expand their activities. The cluster market component would ensure conducive market environments for the FBO capacity building, so they readily aggregated this aspect. 2SCALE gave less priority to social protection than the two NGOs used to do, but this issue was not raised as important. Through workshops, trust was built that IFDC was sensitive to NGO concerns. This smoothed acceptance of a more market-oriented intervention approach ().

Table 5 Institutional logics of practice enacted by local NGOs, EPDRA and SEND. For the different types of farmers and members of the soybeans cooperatives, the 2SCALE cluster approach and FBO support primarily meant more access to credit, agricultural advice, tractor services and market opportunities.

The institutional logics of the training and cooperative arrangements implemented by the local NGOs fitted the logics of both the commercial and the semi-subsistence farmers, as, for both, soybean is a cash crop for which they apply a market rationality: one invests in land, labour and cash to buy inputs so as to obtain a cash revenue. However, given the variety in resource endowment and livelihood strategies, their use and appreciation of the support provided differed depending on their situation and group logic (). Farmers with more land and capital resources make more use of tractor services, and they highly valued the cluster marketing structure with the profitable prices negotiated by cooperative leaders. Several commercial farmers were elected as leaders and benefitted from agricultural, business management and financial training, which they were supposed to, and often did, share with other cooperative members. For a commercial farmer, ‘it is an opportunity to learn more on soybean production, build a strong force to access loans and negotiate good prices and deals with buyers, do collective marketing, access tractor and input services.’ A semi-subsistence farmer felt that ‘previously, there was no local market to sell in bulk. You produce 10 bags, but can only sell one. You spend the money, and then sell another the next week. Now we can sell in bulk to the cooperative and get all the money in about two weeks’ time’. For semi-subsistence farmers, the project primarily entailed more access to credit and secure input and output markets for cash crop production to satisfy bulk cash needs. The NGOs allowed members to use credit for non-soybean investment, when farmers felt that this would better serve urgent needs or their livelihood strategy. Although cooperative members were informed about best agricultural and business practices to achieve high soybean production and cash revenues, they could use cooperative services in a way deemed fit for their circumstances, as long as they honoured group credit payments. BoPInc identified a local BoP market for soybean khebab at schools in the vicinity. This enabled NGOs to train women in khebab preparation and create a new local outlet for a nutritious product.

Table 6 Institutional logics of practice enacted by farmer cooperative members.

In sum, this case shows that the partnership consisted of a strategic mobilisation and bricolage process. Potential partners assessed the fit of logics between their organisation’s vision and that of the initiating actor IFDC, but especially the proposed 2SCALE activities and funding. There was quite some bricolage in the mobilisation process. The 1000s+ project combined agricultural professionalisation with grassroots empowerment logics for market development. When the Dutch Donor became involved, the development means became the end: market creation was prioritised. Its influence was substantial. Apart from market logics, professionalisation of agriculture and business management became a key priority, but coupled with FBO empowerment. This 2SCALE logic fitted BoPInc as well as the daily activities of several NGOs in the northern region. They agreed to commit to the 2SCALE implementation. They aligned with the discourse of 2SCALE, while in practice allowing some flexibility for smallholders to use credit and other services as they saw fit. This primarily served the interests of commercialised farmers and to some extent also the semi-subsistence farmers.

4.3 The DONATA innovation platform in the cassava value chain

Initiation of DONATA: The institutional logics of research and development partners initiating the DONATA project

As agricultural productivity in West Africa was still relatively low as a result of the limited uptake of new technologies, the West and Central African Council for Agricultural Research and Development (CORAF/WECARD) and the Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa (FARA) decided to launch the DONATA project (2011–2014). Instead of the traditional top-down dissemination approach from research to farmers, they adopted the Integrated Agricultural Research for Development (IAR4D) approach: a multi-stakeholder process using an innovation platform as one of the key tools for participatory and collective action to facilitate livelihood and/or value chain development. The African Development Bank, aiming to improve the quality of Africa’s growth: inclusive growth, and the transition to green growth”, readily accepted to fund the initiative to accelerate the use of agricultural technologies by smallholders in the food sector. After successful negotiation of funding from the AfDB, CORAF/WECARD called upon the National Agricultural Research Systems (NARS) to join this initiative. In Ghana, CSIR-CRI was appointed to lead the DONATA project in collaboration with the MoFA in the cassava value chain to reduce poverty among smallholders and enhance food security.

So, initially, the research councils CORAF/WECARD and FARA proposed to combine the conventional professionalisation logic with a local multi-stakeholder learning logic to improve food security. The national research institute CSIR, still mainly executing a linear R&D logic, was stimulated to engage in multi-stakeholder learning and grassroots development logics. Some researchers acknowledge the value of multi-stakeholder learning and grassroots development logics but lack the resources to engage in such R&D processes. The funding enabled them to embrace these logics (aggregation).

The CSIR-CRI focal person contacted the DAO in the Wenchi municipality of Brong Ahafo region to implement this new development approach. The DAO used to work from an agricultural professionalisation logic but had a limited mandate and few resources to execute this (). However, on learning about the DONATA principles, the DAO director felt that the IP approach presented an opportunity for knowledge sharing and the adoption of technologies. The project funding allowed him to apply this more participatory approach. So there was a fit of logics in thinking (aggregation), but an alteration in practice. This new institutional arrangement could not, however, be sustained after the project, as the DAO did not have the funding or the mandate to institutionalise the IP approach: ‘IPs cannot be established without provision of critical resources like money to ensure the equipment and infrastructure needed. The IP model can only be successful with support from a project, NGO or the district assembly’ (Director, DAO). In the end, the state logic prevailed, and provision of a public service could not be continued.

Table 7 Institutional logics of practice enacted in the MoFA DAO and DONATA cassava project.

Implementation of DONATA: The fit of institutional logics and the bricolage of IP farmer members

At local level, the project operated through IPs, as informal arrangements between local value chain actors. Initially, the IP consisted only of about 30 farmers and (female) farmer processors. The DAO had oversight responsibility for coordinating, facilitating and implementing the IP’s daily activities. An NGO was subcontracted to provide training on agriculture and business management. With funding from the project, new cassava varieties were distributed, and farmers started to experiment with new agricultural practices, introduced by CSIR-CRI scientists. When agricultural production improved, transport, processing and market issues were discussed, and local authorities, transporters and traders were invited to join the IP. Transport arrangements were created and, with funding from the project, a collective cassava processing unit was built so that all farmers could easily process their cassava into gari.

The farmers accepted the IP approach, as groups usually received more support from development practitioners (refer to ). As poor migrants from the Northern provinces, they had hardly any land property rights, rented farm land and were eager to use any support to make ends meet. They welcomed the highly productive cassava varieties, selectively applied the agricultural advice fit for their farm situation, and engaged in dialogue with traders and transporters to tackle local market issues. The learning and grassroots development logics required time but served the prime needs of the cassava farmer-processors to achieve a decent livelihood. So, there was a complementarity of logics, and little bricolage. This changed when the DAO wanted to implement a fast version of the IP learning in other villages. Here, grassroots engagement was weak. Autochthon farmers were not interested, as they owned land and prioritised remunerative cashew production.

Table 8 Institutional logics of the practice enacted by farmer-processor IP members.

In sum, the DONATA case showed a fit of logics between CORAF/WECARD and some of the CSIR researchers. Some CSIR researchers as well as the DAO embraced the new multi-stakeholder learning logic, which was operationalised as a grassroots empowerment approach coupled with expert-based agricultural advice. In principle, grassroots empowerment logic is contradictory to top-down professionalisation logic. This tension was solved in a practical way: farmers used the grassroots empowerment logic to improve cassava transport and processing and selectively adopted the agricultural advice.

5 Comparative analysis

To provide insight in the institutional logics that different actors in the staple food sector adhere to; the likelihood that they initiate or join a partnership, and the plausible pathways of bricolage, we hereby present the findings and comparative analysis related to our research questions.

5.1 Type of institutional logics that partnership actors adhered to

5.1.1 Donors

Like many bilateral donors nowadays, the Dutch embassy adheres to a market logic and prioritised the promotion of business development and market structures above social protection, as Ghana is a middle-income country ‘with whom relations should transform from aid to trade’ (CitationMinistry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands, 2013: 40). Meanwhile the African Development Bank explicitly aimed “to improve the quality of Africa’s growth: inclusive growth, and the transition to green growth”, hence they accepted to fund a project aimed to improve growth in the staple food sector, essential for the rural poor (grassroots empowerment & social protection logics).

5.1.2 NGOs

As many faith-based and social justice NGOs, EPDRA and SEND prioritised the poverty alleviation/social protection logic and the grassroots empowerment logic. As a means to achieve this they embraced the agricultural professionalisation logic coupled with FBO organisation.

IFDC had another earmark. It was created to promote the professionalisation of agriculture, based on input-intensive good practices, gradually prioritising market logic to create conducive conditions for farmer development. Its project experience taught it that ‘it was essential to hook up with local leaders and business champions’ and opt for grassroots development logic (personal communication- project initiator).

BoPInc worked from the free market premise and therein specifically focused on BoP producers and BoP markets. Both organisations opted for professionalisation to ensure that the products produced meet the quality criteria of consumer markets, using state-of-the-art advisory tools and training.

5.1.3 Research

The majority of agricultural researchers still adhere to a top-down R&D driven professionalisation logic, but there is an increased acknowledgement of the need of a multi-stakeholder learning logic. In practice this logic is enacted as needs-based professionalisation coupled with grassroots empowerment.

5.1.4 Government

The Ghana government prioritises the commercial development of the agricultural export sector and was not very present in the staple food case studies. There were no linkages with the MoFA at national level. In the DONATA IP, CSIR-CRI took the lead and directly contacted the DAO. For the DAO, its mandate for public service covered agricultural professionalisation and participatory learning approaches, but the limitation of resources highly constrained the office’s functioning. 2SCALE’s PPP had not put an effort into linkages with government offices as ‘they worked slowly and had little to add’ (personal communication).

5.2 The fit and bricolage of logics in partnerships aimed at developing the staple food sector

The study demonstrated the importance of looking at partnership arrangements as context-embedded iterative mobilisation and negotiation processes in which actors continuously compare the fit of logics between themselves and the envisioned development intervention. As the vision evolves, new opportunities for fit arise or their alignment is negotiated through creative bricolage.

5.2.1 2SCALE

| • | Direction & Entry point IFDC/ICRA: In the 1000s+ project, IFDC/ICRA worked on a grassroots development approach to agriculture and agribusiness. However, when negotiation of the next project phase was due, they changed priorities. To align with the Dutch Donor’s market and efficiency logics, they introduced the cluster approach and more contractual PPP commitments (alteration). | ||||

| • | Institutional fit of partnership actors involved and subsequent bricolage: In the 2SCALE proposal free market logics were given a relatively higher priority in 2SCALE than in most partners’ organisational visions (see ). The initiators bricolaged with the different concepts to secure legitimacy amongst all the partners. They prioritised free market logic but kept the farmer organisation empowerment part and added the BoP market idea. In need of financial resources, NGOs joined in and started to prioritise the creation of market links, coupled with FBO empowerment (alteration). | ||||

| • | Fit of partnership logic with the local institutional field: In the end, 2SCALE fitted the logic and the interests of resource-endowed farmers. The clusters provided them with more formal, secure market relations, and they learned how to negotiate profitable market deals. Semi-subsistence farmers also benefitted, but to a limited extent as they could not afford to specialise in high-profit but risky undertakings. | ||||

Table 9 Blended logics of actors and negotiated re-prioritisation and bricolage of logics in the 2SCALE PPP within the soybean value chain.

5.2.2 DONATA

| • | Direction & entry point CORAF/CSIR:The DONATA IP project, initiated by African researchers, highlighted the need for multi-stakeholder learning to achieve a needs-based adoption of technologies (professionalisation) and grassroots empowerment. | ||||

| • | Institutional fit of partnership actors involved and subsequent bricolage: These formal project logics fitted the ideals and resource needs of the DAO, which embraced the logics (aggregation) for as long as resources allowed (Refer to ). | ||||

| • | Fit of partnership logic with the local institutional field: The explicit choice to focus on a critical national food value chain implied that the project was mainly attractive for more resource-poor farmers. Because of limited storage and processing capacity, food prices fluctuate and are not always profitable. Farmers who own sufficient land therefore prioritised cashew production and rejected project participation as it did not fit their interests. | ||||

Table 10 Blended logics of actors and negotiated re-prioritisation & bricolage of logics in the DONATA IP within cassava value chain.

In comparison we see that development actors either tend to prioritise a combination of market and professionalisation logics, or grassroots empowerment with social protection logics. The 2SCALE PPP involved more partners with a wider variety of logics than the DONATA IP. This forced them to loosely couple different, at times contradictory ideas and logics. As a result the 2SCALE partnership served several categories of smallholders. DONATA IP consisted of a collaboration between two actors, with quite similar logics. Though engaging with a wide variety of actors at local level, their IP logics and focus on a major staple food crop of Ghana led to a development intervention most fit for a specific target group: the most resource-poor. Hence, through the IP arrangement, Ghana researchers and government targeted the smallholder category that risked not to be catered for by PPP arrangements.

6 Discussion and conclusion: the value of the concepts of institutional logics and bricolage as a diagnostic tool for unravelling multi-actor partnerships

The concepts of institutional logics and institutional bricolage enable the researcher to better understand partnership-led change processes, as they make explicit the entry points of parties involved in the partnerships, in terms of what institutional logic they bring into the setting of a partnership, and how different institutional logics are thus mobilized when partnerships negotiate the direction of the development intervention in terms of goals and methods.

Doing such institutional diagnosis is important in contexts in which public, private and civic society interests come together in partnerships that often cross borders (CitationBitzer et al., 2008; CitationManning and Roessler, 2014; CitationHansen and Nygaard, 2013). Furthermore, various donors supporting partnership based approaches differ in terms of their development approach, and this requires coordination (CitationLawson, 2013). Donors also need to coordinate with domestic development actors (such as government − see CitationMockshell and Birner, 2015). These differences in entry points and development approaches calls for having clarity on the initial position in a partnership, as institutional fit between partners is not a given. However, a related critical question is whether institutional fit is desirable, or achievable, as it may give dominance to certain values and practices that may exclude certain groups (see also CitationRos-Tonen et al., 2015; CitationKilelu et al., 2017). Rather than total convergence, institutional fit may rather be seen as a degree of convergence that makes the partnership workable, while accommodating different institutional logics as we will argue below, in discussing the insights our study yielded in view of our diagnostic questions. We will also offer some broader theoretical and practical implications of our findings and the tool for institutional diagnostics used.

6.1 Key insights from diagnostic questions

As regards the diagnostic questions 1 and 2 of what types of institutional logics different partnership actors adhere to and bring into partnerships, and how this give direction to the development intervention, we found that:

| • | The international operating partnership-initiating NGO and Research Association both primarily aimed at professionalisation, but also adhered to market and grassroots development logics. | ||||

| • | Bilateral donors adhered to market logics, and obliged the partnership initiator to prioritise this logic in the formulation. The African donor AfDB is market oriented, but with specific segments that prioritise grassroots development logics. Hence they accepted the partnership professionalisation and grassroots empowerment logic as proposed by the Research Association. | ||||

| • | In their practice, local implementing actors adhered to professionalisation, grassroots development and social protection logic. As a result the 2SCALE implementing NGOs put more effort in the enactment of the market logic (creating market clusters) than before, but continued to pay attention to grassroots development and social protection logic. The local implementing DAO logics aligned with the logics proposed by DONATA, so here there was no change of direction. | ||||

In view of diagnostic question 3 on how these different logics influence institutional fit (question 3), we found that in negotiating institutional fit, some logics are prioritised and integrated, whereas others are downplayed or left out. This attests to the power of certain actors to initiate, constrain or change an intervention logic; in other words, the room of manoeuvre that different organisations or categories of farmers have in terms of shaping the partnership and the direction of the development intervention (or in bricolage terms, through alteration (partnership actors) and selective aggregation (farmers). Partnership initiators strategically mobilise partners and set the scene in which donors and implementers subsequently exert their influence. The study also shows the ambiguity of expressed visions and the loose coupling of sometimes contradictory logics (CitationCarstensen, 2011). As discussed above, in our case, many actors combined the professionalisation discourse, based on expert knowledge and international trade and consumer requirements, with the grassroots empowerment discourse.

Considering diagnostic question 4 on what type of bricolage took place during which partnership phase, we found that the creative and strategic bricolage of ideas takes place during mobilisation but also during implementation, mainly through alteration. In our case of Ghanaian staple food value chains, bricolage led to efforts to balance different logics. Although bilateral donors nowadays favour aid to establish trade with their own national companies, there are still a substantial number of multi- and bilateral donors involved in the development of the Ghanaian staple food sector, especially in the relatively poor north. Our study suggests that the increasingly promoted PPP arrangements funded by these donors nudge NGOs, farmer organisations and local businesses towards prioritising market logics and professionalisation. This gradual acceptance of globally and nationally legitimised discourses by organisations operating locally is a known phenomenon called ‘leakage of meaning’ (CitationCleaver and De Koning, 2015). However, what we also see is that development organisations still embrace the grassroots empowerment and social protection logics. In the staple food sector, characterised by smallholder production and a lack of formal market relations, regulatory framework and infrastructure, development NGOs tend to embrace the grassroots empowerment approach, combining market logic with social protection logic. More emphasis on the creation of market structures, contractual commitments enforced by donors, may help to create market structures and reduce uncertainties. However, to ensure fair margins and freedom of choice for smallholders, it remains essential to couple this market orientation with strong grassroots empowerment and the social protection logic. Development NGOs thus mobilised like-minded people so that their logics maintained their momentum and will still be considered in implementation. Field level officers from implementing NGOs created cluster market structures, but coupled with FBO capacity building and a concern for the uncertain situation with which resource-poor farmers have to cope.

6.2 Broader theoretical and practical implications of institutional diagnosis of partnership based development approaches

Beyond the specific case of the staple food sector in Ghana, the broader relevance of our analysis is that our analysis shows that despite the fact that powerful actors like donors nowadays increasingly opt for ‘from aid to trade’ discourses, in the actual implementation there is a balance between market as well as other logics such as grassroots development and social protection logics and that implementing actors in the partnership (such as NGOs) still have the room of manoeuvre to work along the logics they cherish. Hence, what can be observed is that while in the negotiation process within partnerships on objectives and approaches to development taken, the institutional logics are malleable and adapted through bricolage, to some extent they also maintain a certain purposeful or strategic rigidity. This rigidity is upheld to make sure that elements in a development process (e.g. grassroots empowerment, social protection) which may not be considered relevant anymore by some parties in a partnership, are still considered. Hence the transformation of institutional logics in development sectors may go slow as it encounters an established and to some extent rigid local structure. In other words, the change in thinking about development in donor countries, does not automatically lead to a change in logic of the local institutional field, despite the fact that donors (and their executive agencies) are quite powerful actors who put their issues in the agenda during the initiation and formulation of partnerships. The agency of donors exercised through the partnership, is only partly supported and also meets with ‘counter agency’ by local actors. These findings are in line with other literature highlighting the power of field workers to flexibly adapt project logics to local circumstances (CitationLipsky, 1980; CitationLewis and Mosse, 2006; CitationMorrison, 2010). In view of convergence and institutional fit within the partnership this may not be ideal (i.e. causing friction between partners), but as long as the partnership is workable, it may actually provide a better fit of the intervention done by the partnership within the local institutional field as it facilitates that the intervention is adapted to local circumstances.

A final practical reflection is on the utility of the concepts of institutional logics and bricolage: the use of this conceptual lens as a diagnostic tool enables researchers and development practitioners to characterise the institutional logics in the sector or realm in which the partnership operates, the blends of logics that actors adhere to, and the fit of logics between them and the envision partnership logics. This allows practitioners to strategise their actions: to decide with whom to align for an envisioned intervention in the food sector and what partnership logics they could propose or negotiate in discussions and manage during enactment. It provides development practitioners with a tool to gain insight into the context-defined possibilities (core logics in a specific sector; adherence to and blending of logics by different actors, and actor relationships), their room for manoeuvre and possible influence they can exert via strategic mobilisation of partners and negotiation of partnership interventions to realise their ideals. For policy makers, it can give them a reality check on the extent to which their development ideas are congruent with actual conditions on the ground, or whether these need adjustment, or a longer transition period (e.g., in moving from a grassroots empowerment to a full market logic).

A limitation of this paper and the institutional diagnosis methodology used is that it focused on the negotiation of logics at a higher level of abstraction. We did not highlight the everyday tactics in bricolage as expressed in the concept of institutional entrepreneurship (CitationBattilana et al., 2009): the strategic communication, social positions, and other resources that individuals mobilise ‘to make a difference’ in the course of negotiation and action. We rather showed the structuring role of ongoing bricolage. In that sense, the institutional logics lens gives a simplified diagnosis of ongoing change. For a more comprehensive picture, ethnographic research of the actual implementation process (CitationMosse, 2004) is recommended. Furthermore, with the presented diagnostic tool we can gain insight in the strategic mobilisation and bricolage of logics by partners in a partnership, but as it applies a case study approach, this methodology does not allow to get a comprehensive overview of the segmentation and differentiation of the logics in the development sector of staple food production and cannot monitor the transformation of a whole sector. Through document analysis it would be possible to monitor such change, for example by analysing discourses in policy papers and program proposals and monitoring and evaluation reports, but this again may not show the finer details of institutional bricolage processes. Here a trade-off seems to lie as regards the applicability of institutional diagnostics.

Acknowledgements

With recognition of the support of the Dutch NWO/WOTRO fund ‘Strategic actors for inclusive development’ and INCLUDE (the Knowledge platform on inclusive development policies). We acknowledge the actors of the soybean and cassava partnerships and three anonymous reviewers.

References

- J.BattilanaB.LecaE.BoxenbaumHow actors change institutions: towards a theory of Institutional EntrepreneurshipAcad. Manag. Ann.31200965107

- A.BebbingtonD.LewisS.BatterburyE.OlsonM.S.SiddiqiOf Texts and practices: empowerment and organisational cultures in World Bank-funded rural development ProgrammesJ. Dev. Stud.4342007597621

- S.D.BiggsA multiple source of innovation model of agricultural research and technology promotionWorld Dev.18199014811499

- V.BitzerM.FranckenP.GlasbergenIntersectoral partnerships for a sustainable coffee chain: really addressing sustainability or just picking (coffee) cherries?Global Environ. Change1822008271284

- M.B.CarstensenParadigm man versus the bricoleur: bricolage as an alternative vision on agency in ideational changeEur. Polit. Sci. Rev.312011147167

- F.CleaverJ.De KoningFurthering critical institutionalismInt. J. Commons912015118(URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-116918)

- F.CleaverReinventing institutions: bricolage and the social embeddedness of natural resource managementEur. J. Dev. Res.1422002113010.1080/714000425

- J.De KoningF.CleaverInstitutional bricolage in community forestry: an agenda for future researchB.ArtsForest-People Interfaces (277–290)2012Wageningen Academic PublishersWageningenThe Netherlands

- D.DentoniV.BitzerS.PascucciCross-sector partnerships and the co-creation of dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientationJ. Bus. Ethics135120163553

- P.G.H.EngelFacilitating Innovation: An Action-Oriented Approach and Participatory Methodology to Improve Innovative Social Practice in Agriculture PhD Thesis1995Wageningen University WageningenThe Netherlands

- R.FriendlandR.AlfordBringing society back in: symbols, practices, and institutional contradictionsW.W.PowellP.J.DimaggioThe New Institutionalism and Organisational Analysis1991The University of Chicago PressChicago263323

- L.FuenfschillingB.TrufferThe structuration of socio-technical regimes; Conceptual foundations from institutional theoryRes. Policy432014772791

- C.C.FunkM.E.BrownDeclining global per capita agricultural production and warming oceans threaten food securityFood Security12009271289

- D.P.GarrityF.K.AkinnifesiO.C.AjayiS.G.WeldesemayatJ.G.MowoA.KalinganireM.LarwanouJ.BayalaEvergreen agriculture: a robust approach to sustainable food security in AfricaFood Security232010197214

- P.GlasbergenSetting the scene: the partnership paradigm in the makingP.GlasbergenF.BiermannA.P.J.MolPartnerships, Governance and Sustainable Development; Reflections on Theory and Practice2007Edward ElgarCheltendam, UK125

- H.C.J.GodfrayJ.R.BeddingtonI.R.CruteL.HaddadD.LawrenceJ.F.MuirJ.PrettyS.RobinsonS.M.ThomasC.ToulminFood security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion peopleScience32759672010812818

- K.HallF.CleaverT.FranksF.MagangaCapturing critical institutionalism: a synthesis of key themes and debatesEur. J. Dev. Res.26120147186

- U.E.HansenI.NygaardTransnational linkages and sustainable transitions in emerging countries: exploring the role of donor interventions in niche developmentEnviron. Innov. Soc. Trans.82013119

- IFDC/2SCALE, 2012. Towards sustainable clusters in agribusiness through learning in entrepreneurship. A Public-Private Partnership Proposal. BoP Inc., Utrecht; the Netherlands; ICRA, Wageningen, the Netherlands; and IFDC, Muscle Shoals, Alabama, USA.

- C.W.KileluL.KlerkxC.LeeuwisUnravelling the role of innovation platforms in supporting co-evolution of innovation: contributions and tensions in a smallholder dairy development programmeAgric. Syst.11820136577

- C.KileluL.KlerkxA.OmoreI.BaltenweckC.LeeuwisJ.GithinjiValue chain upgrading and the inclusion of smallholders in markets: reflections on contributions of multi-stakeholder processes in dairy development in TanzaniaEur. J. Dev. Res.201712010.1057/s41287-016-0074-z

- L.KlerkxC.LeeuwisEstablishment and embedding of innovation brokers at different innovation system levels: insights from the Dutch agricultural sectorTechnol. For. Soc. Change762009849860

- S.KolavalliE.RobinsonX.DiaoV.AlpuretoR.FolledoM.SlavovaG.NgelezaF.AsanteEconomic transformation in Ghana: where will the path lead?J. Afr. Dev.14220124178

- D.LamersM.SchutL.KlerkxP.van AstenCompositional dynamics of multilevel innovation platforms in agricultural research for developmentSci. Public Policy201711410.1093/scipol/scx009Oxford University Press, Oxford

- M.L.LawsonForeign aid: international donor coordination of development assistance, foreign aid: analyses of efficiency, effectiveness and donor coordinationCRS Report for Congress, Prepared for Members and Committees of CongressWashington, DC(2013) 37–72.

- C.LeeuwisReconceptualizing participation for sustainable rural development: towards a negotiation approachDev. Change312000931959

- Claude.Levi-StraussThe Savage Mind1966University of Chicago PressChicago

- D.LewisD.MosseDevelopment Brokers and Translators: The Ethnography of Aid and Agencies2006Kumarian PressWest Hartford, CT

- D.LewisA.BebbingtonS.BatterburyA.ShahE.OlsonM.S.SiddiqiL.S.DuvalPractice: power and meaning: frameworks for studying organisational culture in multi-agency rural development projectsJ. Int. Dev.152003541557

- M.LipskyStreet-level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Service1980Russell SageNew York

- M.LounsburyA tale of two cities: competing logics and practice variation in the professionalizing of mutual fundsAcad. Manag. J.5022007289307

- S.ManningD.RoesslerThe formation of cross-sector development partnerships: how bridging agents shape project agendas and longer-term alliancesJ. Bus. Ethics1232014527547

- M.M.MarsM.LounsburyRaging against or with the private marketplace? Logic hybridity and eco-entrepreneurshipJ. Manag. Inquiry1812009413

- M.M.MarsH.J.SchauInstitutional entrepreneurship and the negotiation and blending of multiple logics in the Southern Arizona local food systemAgric. Hum. Values3422017407422

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the NetherlandsA World to Gain; A New Agenda for Aid, Trade and Investment2013Ministry of Foreign AffairsThe Hague, the Netherlands

- J.MockshellR.BirnerDonors and domestic policy makers: two worlds in agricultural policy-making?Food Policy552015114

- J.K.MorrisonFrom global paradigms to grounded policies: local socio-cognitive constructions of international development policies and implications for development managementPublic Admin. Dev.302010159174

- D.MosseIs good policy unimplementable? Reflections on the ethnography of Aid policy and practiceDev. Change3542004639671

- Mwaniki, A., 2006. Achieving food security in Africa: Challenges and issues. UN Office of the Special Advisor on Africa (OSAA) http://www.un.org/africa/osaa/reports/Achieving%20Food%20Security%20in%20Africa-Challenges%20and%20Issues.pdf (Last accessed on 10, August 2016).

- E.S.NederlofN.RölingA.Van HuisPathway for agricultural science impact in West Africa: lessons from the convergence of sciences programmeInt. J. Agric. Sustain.52007247264

- D.C.NorthInstitutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance1990Cambridge University PressLondon

- TalcottParsonsThe Social System1951Free PressNew York

- C.K.PrahaladThe Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid Eradicating Poverty Through Profits5th edition2010Pearson Education, Prentice HallUpper Saddle River, NJ

- J.M.PurdyB.GrayConflicting logics, mechanisms of diffusion, and multilevel dynamics in emerging institutional fieldsAcad. Manag. J.5222009355380

- N.RölingPathways for impact: scientists’ different perspectives on agricultural innovationInt. J. Agric. Sustain.720098394

- H.RaoP.MoninR.DurandInstitutional change in toque ville: nouvelle cuisine as an identity movement in french gastronomy 1Am. J. Sociol.10842003795843

- D.ResnickStrong Democracy Weak State: The Political Economy of Ghana’s Stalled Structural Transformation 1574 IFPRI Discussion Paper 15742016IFPRIWashington, DC

- J.RitchieJ.LewisGeneralising from Qualitative Research. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers2003Sage PublishingCalifornia263286

- M.A.F.Ros-TonenY.-P.B.Van LeynseeleA.LavenT.SunderlandLandscapes of social inclusion: inclusive value-chain collaboration through the lenses of food sovereignty and landscape governanceEur. J. Dev. Res.272015523540

- M.W.RosegrantS.A.ClineGlobal food security: challenges and policiesScience3025652200319171919

- SEI (Stockholm Environment Institute), 2005. Sustainable pathways to attain the millennium development goals—assessing the role of water, energy and sanitation. Research report prepared for the UN World Summit, 14 September, 2005, New York. Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI) Stockholm http://www.sei.se/mdg.htm.

- SEND-Ghana, 2015. Investing in Extension Services to achieve the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) Goals in Ghana. Downloaded 3 January 2016 from http://www.sendwestafrica.org/index.php/latest-news/item/39-investing-in-extension-services-to-achieve-the-comprehensive-africa-agriculture-development-programme-caadp-goals-in-ghana.

- G.SchoutenS.VellemaJ.V.WijkDiffusion of global sustainability standards: the institutional fit of the ASC-Shrimp standard in IndonesiaRevista de Administração de Empresas5642016411423

- G.SchoutenM.J.VinkS.VellemaInstitutional diagnostics for African food security: approaches, methods and implicationsNJAS–Wageningen J. Life Sci.2017(in this issue)

- B.SenadzaA.LaryeaManaging Aid for Trade and Development Results; Ghana Case Study Policy Dialogue on Aid for Trade Paper2012OECDParis, France

- D.J.SpielmanF.HartwichK.GrebmerPublic–private partnerships and developing-country agriculture: evidence from the international agricultural research systemPublic Admin. Dev.302010261276

- J.H.J.SpiertzF.EwertCrop production and resource use to meet the growing demand for food, feed and fuel: opportunities and constraintsNJAS–Wageningen J. Life Sci.5642009281300

- P.C.StruikL.KlerkxA.van HuisN.G.RölingInstitutional change towards sustainable agriculture in West AfricaInt. J. Agric. Sustain.1232014203213

- P.ThorntonW.OcasioInstitutional logics and the historical contingency of power in organizations: executive succession in the higher education publishing industry, 1958–1990Am. J. Sociol.10531999801843

- P.H.ThorntonW.OcasioInstitutional logicsR.GreenwoodC.OliverK.ShalinR.SuddabyOrganisational Institutionalism2008SageLondon99129

- P.H.ThorntonW.OcasioM.LounsburyThe Institutional Logics Perspective A New Approach to Culture, Structure, and Process2012Oxford University PressUnited Kingdom

- P.H.ThorntonMarkets from Culture: Institutional Logics and Organizational Decisions in Higher Education Publishing2004Stanford University PressStanford, CA

- A.Van HuisJ.JigginsD.KossouL.LeeuwisN.RölingO.Sakyi-DawsonP.C.StruikR.C.TossouCan convergence of agricultural sciences support innovation by resource-poor farmers in Africa? The cases of Benin and GhanaInt. J. Agric. Sustain.52–3200791108

- World BankAgriculture for Development: World Development Report 20082007World BankWashington, DC

- R.K.YinCase Study Research, Design and Methods4th edition2009SageNewbury Park, CA

- O.R.YoungInstitutional dynamics: resilience, vulnerability and adaptation in environmental and resource regimesGlobal Environ. Change20201037838510.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.10.001