Highlights

| • | Queensland fruit fly (QFly) hinders trade for Australian horticulture growers. | ||||

| • | Systems approaches and QFly area-wide management may support regulated trade. | ||||

| • | The Australian biosecurity paradigm often requires industry-driven approaches. | ||||

| • | A functional-structural analysis provides holistic insight in what hinders progress. | ||||

| • | Innovation platforms, local training and less transaction cost are recommended. | ||||

Abstract

In many countries the biosecurity system is under financial strain resulting in an on-going push for shared responsibility and greater industry self-reliance. This occurs in an increasing globalised, multi-level trade context. It raises the question of how the broader support system for local industries can be improved to help industries help themselves. This work relates to systems approaches as a phytosanitary measure in horticulture trade to address pest concerns. Specifically, it investigates how to create an enabling environment for local Australian horticulture industries to pursue systems approaches involving area-wide management (AWM) of Queensland Fruit Fly (QFly). A functional-structural analysis is applied to identify issues that prevent local industries pursuing systems approaches and to suggest ways forward. Primary data is derived from semi-structured interviews with representatives from three levels of government, industry bodies, consultancies and other key groups, complemented by a grower survey in three case study regions. Systems approaches involving AWM comprise a complex domain as it is situated across multiple levels from the local to the international; it involves various dimensions and many rationally-bounded actors. Key blocking mechanisms to local progress include a lack of clear change pathways for local industries; low connectivity between local industries and the innovation system; currently feasibility signals for systems approaches including AWM are weak; and systems approaches are problematic. Ways forward include supporting and initiating innovation platforms, offering domestic and international market access training; and minimising transaction costs to industry.

1 Introduction

Pests and diseases have challenged agriculture since humanity started cultivating food. Besides the impacts on productivity, in an increasingly globalised world many pests and diseases now also have significant implications for domestic and international market access for agricultural produce. Recent decades have witnessed an expansion of formal rules and measures at national and international levels to prevent pest and disease spread associated with trade (CitationMaye et al., 2012).

This article explores the promotion of a pest management approach, i.e. area-wide management (AWM). It asks, how can an enabling environment for industry-driven AWM be created in order to support domestic and international market access for Australian horticultural produce? In answering this question, this article generates insights into how the modern-day biosecurity paradigm configures local constraints and opportunities and shapes the possible means to addressing challenges.

Pests often represent complex problems, that is, they involve uncertainty and multiple facets; with actors and institutions situated across international, national, state, regional, and on-farm levels (CitationSchut et al., 2015). Attempts to strengthen Australian agriculture, including biosecurity, have traditionally relied on technology development and linear technology transfer approaches to farmers (CitationNettle et al., 2013). The great majority of plant protection literature is based on mono-disciplinary thinking and is technology-oriented (CitationSchut et al., 2014) with some exploring economic impacts (e.g. CitationYu, 2006). While these have brought tremendous advances, disappointment with outcomes, including a lack of on-ground adoption, is increasingly leading to calls to approach innovation from a holistic systems perspective (CitationSchut et al., 2014). This involves broadening the problem-solving arena to include social and institutional dimensions in order to create an enabling environment for progress to occur (Röling et al., 2012;CitationKlerkx et al., 2012Citation).

This paper contributes to filling this void by applying agricultural innovation systems (AIS) thinking that conceptualises innovation as co-evolving technological, social, organisational, and institutional change (CitationKlerkx et al., 2010). This paper presents a structural-functional analysis of the Australian innovation system for the management of the pest under consideration, i.e. Queensland fruit fly (Bactrocera tryoni (Froggatt)). The innovation system here is defined as the operating arrangements that set out how actors and institutions interact and exchange knowledge to develop and spread innovations (CitationBusse et al., 2015). This work argues that a well-functioning innovation system will create conditions that enable entrepreneurial activities to thrive (CitationHekkert et al., 2007, CitationKruger, 2017).

The paper is organised as follows. The remainder of Section 1 describes the QFly challenge in the modern biosecurity context. Section 2 introduces the structural-functional theoretical framework, while the research methods are outlined in Section 3. Section 4 describes the structural and functional components of the QFly management innovation system. Section 5 explores blocking mechanisms, and policy interventions are suggested in Section 6.

1.1 Background

The fruit fly family Tephritidae is one of the world’s most significant horticultural pests. The annual global cost is around US$ 2 billion, including impacts on production, harvesting, packing and marketing (CitationMalavasi, 2014). Eastern Australia is confronted by Queensland fruit fly, or QFly. The fly is of considerable concern to Australia’s international horticulture trading partners. Most of Australia's fruit and vegetable exports, worth approximately AUS$1048 million in 2014–15 (CitationAbares, 2015), are susceptible to varying degrees (CitationPlant Biosecurity CRC, 2015).

The challenge recently intensified following restrictions on two key pesticides, fenthion and dimethoate, traditionally used to control QFly at relatively low cost through a simple single-treatment approach (CitationDominiak and Ekman, 2013). A current key recommended strategy to local industries is the application of area-wide management (AWM) (CitationPHA, 2008; CitationPlant Biosecurity CRC, 2015). AWM involves total pest population management by coordinating control strategies across all key pest sources throughout a region (CitationHendrichs et al., 2007). This allows for the application of softer control techniques for QFly such as protein baits, orchard hygiene, male annihilation technique and sterile insect technique (SIT) (CitationJessup et al., 2007).

Another benefit of AWM is that it is seen as a good candidate to underpin systems approaches for trade (CitationPHA, 2008; CitationDominiak and Ekman, 2013). Systems approaches for trade comprise two or more independent pest treatments or measures throughout the supply-chain that collectively reduce pest risk to an acceptable level (CitationPHA, 2008; CitationJamieson et al., 2013). International trade rules set by the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) recognise such approaches as acceptable phytosanitary measures (CitationDominiak and Ekman, 2013).

This occurs against a national backdrop where Australia’s biosecurity governance during recent decades increasingly emphasise shared responsibility and partnerships between government, industry and the broader community. It includes a shift of biosecurity costs and responsibilities from the state to agricultural producers accompanied by cuts to public biosecurity funding (CitationHiggins et al., 2016). It implies that local industries are predominantly responsible for driving initiatives such as AWM and related systems approaches for market access.

The international context involves the WTO and the IPPC advocating free trade whilst promoting a science-based approach in a bid to minimise biosecurity risk (CitationMaye et al., 2012). For example, they oversee the production of globally agreed International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures (ISPMs) to underpin international trade, including several relating to systems approaches, AWM and fruit flies. Australian biosecurity policies and activities are increasingly aligned with international market logics (ibid.).

Hence, in the modern biosecurity paradigm the market dominates and processes of harmonisation and standardisation rooted in scientific expertise stand central (CitationHiggins et al., 2016; CitationMaye et al., 2012). Some call for more “alternative spaces of negotiation” that allows for more flexibility and negotiation (CitationHiggins et al., 2016; CitationEnticott, 2008).

Within the QFly context, these orderings brings about a complex multi-facetted, multi-level innovation system as is outlined in Box 1. There are multiple horticultural crops, geographical and climatic conditions, types and size of horticultural enterprises, and commodity groups differ in how well they are organised. Besides growers, many other actor groups are involved, including different levels of government, various groups within government departments, industry bodies, diverse public and private research providers and consultancy services.

Diverse actors have wide-ranging interests (CitationRöling et al., 2012) and are rationally-bounded, that is, their decision-making is limited by the information, resources and time available to them. Hence, multiple and sometimes contested logics exist amongst actors about how biosecurity and aspects thereof should be ordered (CitationHiggins et al., 2016).

Box 1 The key structural components of the trade-related QFly management arena.

Actors

International

| • | WTO and IPPC | ||||

Australian Government

| • | Department for Agriculture and Water Resources – responsible for international border biosecurity and trade, including conducting negotiations for overseas trade | ||||

National

| • | State and territory departments responsible for agriculture – oversee onshore biosecurity and domestic trade | ||||

| • | Plant Health Australia – coordinates government-industry partnerships | ||||

| • | Peak industry bodies – representative bodies for different horticulture commodity groups, including providing some support to QFly-affected industries to facilitate trade | ||||

| • | Horticulture Australia Innovation Limited (HIAL) – a research and development corporation and a key funder of QFly-related on-ground initiatives | ||||

Local industries

| • | Local pest/QFly management groups | ||||

| • | Local coordinator (sometimes) | ||||

| • | Growers | ||||

Consultants

| • | Crop consultants | ||||

| • | Market access consultants | ||||

Research providers

| • | State government departments | ||||

| • | SITplus – an almost $AUS 22 million initiative since 2014 that includes extensive research | ||||

| • | Centre for Fruit Fly Biosecurity Innovation – established in 2014 at Macquarie University and involves close cooperation with SITplus | ||||

| • | Plant Biosecurity Cooperative Research Centre | ||||

| • | Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation | ||||

| • | Universities | ||||

| • | Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences | ||||

| • | Private companies/institutes | ||||

Institutions (main ones only)

International

| • | Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (the ‘SPS Agreement’) – is applied by the WTO and IPPC to maintain plant health during international trade | ||||

| • | International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures (ISPMs) – to provide assurances that pest risks are addressed in trade deals | ||||

Domestic

| • | Nationally agreed principles and procedures to manage QFly surveillance, trapping, outbreaks and eradication from pest free areas (under review) | ||||

| • | Draft National Fruit Fly strategy (2008) and National Fruit Fly Strategy Implementation Action Plan (2010) – include strategies to progress AWM of QFly and related trade | ||||

| • | Interstate Certification Assurance (ICA) scheme – domestic trade protocols, many commodity-specific and relating to fruit fly, with some being region-specific | ||||

| • | the National Fruit Fly Research, Development and Extension Plan – released in 2015, including recommendations relating to AWM and trade | ||||

Infrastructure

Funding

| • | Growers | ||||

| • | HIAL – administers grower levies, which are co-funded by government | ||||

| • | State and territory governments | ||||

| • | Australian Government | ||||

| • | Universities | ||||

Knowledge

| • | Fruit fly body of knowledge – Repository of fruit fly related documents and publications | ||||

| • | Research providers listed above | ||||

Physical

| • | QFly trapping networks in pest free areas | ||||

| • | QFly management technologies | ||||

| • | SITplus’ SIT rearing facility | ||||

Interactions (main forums only)

| • | Plant Health Committee – a high-level interstate committee that provides strategic scientific and policy advice related to plant biosecurity to the Australian Government | ||||

| • | National Fruit Fly Council – government and industry committee that provides national leadership and coordination to manage fruit fly in Australia | ||||

| • | SITplus consortium | ||||

| • | Subcommittee on Domestic Quarantine and Market Access – an interstate committee that develops domestic market access conditions, including ICAs | ||||

| • | HIAL’s Trade Assessments Panel (TAP) – an advisory group supporting HIAL providing advice to the Australian Government about prioritising market access applications requiring protocols | ||||

2 Analytical framework

The key research question is how can an enabling environment for industry-driven fruit fly AWM be created in order to support domestic or international market access for Australian horticultural produce? This work is a corollary of earlier research about the social and institutional aspects of local industries pursuing industry-driven AWM, involving three case studies of where AWM has been implemented or is attempted. A key finding was that local industries need help to help themselves through an enabling and supportive institutional environment (CitationKruger, 2016).

2.1 AIS and functional-structural analysis

AIS thinking acknowledges that innovation requires more than techno-centric approaches (CitationKlerkx and Leeuwis, 2008; CitationKlerkx and Nettle, 2013). Innovation that leads to on-ground change tends to flow from improved distribution of existing knowledge by establishing interaction, collaboration and coordination between different actors representing diverse organisations and responsibilities. This leads to co-production of new knowledge and a shared trajectory that can bring about change (CitationKlerkx and Nettle, 2013). However, connections need to be actively constructed and interactions coordinated (CitationKilelu et al., 2013).

CitationHekkert et al. (2007) identified “functions of innovation systems” that represent processes essential to well-performing innovation. This study applies them to determine how the current QFly management innovation system assists and hinders local industries pursuing access to QFly-sensitive markets involving AWM. These functions are:

| • | F1. Entrepreneurial activities – the presence of actors turning new knowledge and networks into actions. Experimenting means more knowledge is produced about the innovation system’s functioning in different circumstances | ||||

| • | F2. Knowledge development – learning forms the core of innovation, including formal research and knowledge production elsewhere | ||||

| • | F3. Knowledge diffusion – comprising networks of multi-directional information flows involving “learning by interacting” and “learning by using” | ||||

| • | F4. Guidance of the search – the innovation process requires direction to optimise use of limited resources. It can cumulatively come from external influences (e.g. rules or benchmarks) and/or a shared vision between key actors | ||||

| • | F5. Market formation – products produced through new technologies compete with what buyers are used to, hence effort is required to secure buy-in | ||||

| • | F6. Mobilization of resources – including financial and human capital | ||||

| • | F7. Creation of legitimacy – the new technology needs to overcome opposition and resistance to change by becoming part of producers’ prevailing accepted practices | ||||

Innovation systems can also be conceptualised based on their structural components. Any weak structural component will compromise the innovation system’s functioning (CitationKebebe et al., 2015). These typically are (CitationWieczorek and Hekkert, 2012; CitationTurner et al., 2016):

| • | Actors – individuals, groups, organisations, businesses, committees and other parties across levels that fulfil certain roles or influence QFly-risk management | ||||

| • | Interactions – the dynamic exchanges between actors | ||||

| • | Institutions (rules) – including (i) hard – legislation, regulations and standards; and (ii) soft – such as norms, customs, ways of conduct and expectations | ||||

| • | Infrastructure – including (i) physical – such as existing technologies and products; (ii) knowledge – expertise, strategic information, research, development and extension; and (iii) financial – subsidies, grants, levy systems and other financial systems | ||||

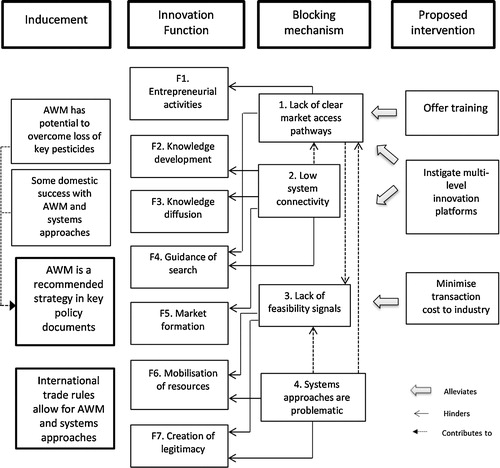

This study involves a combined functional-structural analysis (CitationTurner et al., 2016; CitationKebebe et al., 2015) to offer a holistic system analysis. The seven functions assist in identifying difficulties preventing progress, which are clustered to identify key blocking mechanisms. The blocking mechanisms assist in the identification of policy interventions (CitationTurner et al., 2016).

3 Methods

The research is based on an interpretivist theoretical approach that captured the experiences of actors active in the QFly management innovation system (CitationDenzin and Lincoln, 2000). It involved an inductive-deductive interplay between using and developing theory (CitationEisenhardt and Graebner, 2007). As such, it was during the data collection phase that the functional-structural analysis approach (CitationBergek et al., 2008; CitationWieczorek and Hekkert, 2012) was chosen as it represented a close fit for explaining emerging findings, in particular, it became clear that a combination of factors was slowing progress, rather than a lack of technologies and/or their adoption only.

3.1 Data collection

Thirty-three semi-structured interviews were carried-out during mid-2015. Interviewees were initially selected using purposive sampling by approaching actors in relevant roles in stakeholder organisations. This was followed by “snowball” sampling, for example, interviewees suggested other actors that would allow for exploring some themes in greater depth (CitationDenscombe, 2014). Interviewees included representatives from three levels of government, peak industry bodies, universities, industry consultants and local industries. Interview questions included enquiries about their current roles, how they currently supported local industries with QFly-affected market access, barriers faced in providing support and how they believed local industries can go about securing support. Interviews proceeded on average for an hour, were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim. This research focused on New South Wales (NSW) and Queensland, a corollary of the preceding case study research.

In late 2015 growers in the three case study regions were surveyed () and results are included to allow for methodological triangulation and increase the findings’ richness (CitationDenscombe, 2014). Local management groups or industry associations provided grower contact lists. Only growers interested in supplying to QFly-sensitive markets were asked market access-related questions. Most growers responded electronically via SurveyGizmo, with some returning hardcopies and others completing the survey with a researcher over the phone. Limited fieldwork resources meant only two of the five local government areas (LGAs) in the Riverina were surveyed. The local management group opted for Leeton and Carrathool. A key survey limitation is small population sizes. A review of available policy and scientific literature was performed, to allow for further method triangulation by providing information on context and to verify findings (CitationBowen, 2009).

Table 1 Grower survey.

3.2 Data analysis

Data was analysed in NVivo 10. Findings from the interviews and survey were allocated against the seven functions and the structural components of the structural-functional elements. More details are available in CitationKruger (2017). A document review assisted in filling in gaps in the structural analysis (see Box 1).

3.3 Limitations

This article reports on market access, whereas AWM for QFly suppression is dealt with in separate article using the same methodology (CitationKruger, 2017). This work presents a snapshot in time of the issues faced within the transitioning field of on-ground QFly management. Interviewees’ information might not always have been current in this fast-changing arena. Most recent information, such as meeting minutes of advisory groups, such as the National Fruit Fly Council, was not available to this research.

4 Results

This section outlines the functional-structural analysis. The structural analysis is outlined in Box 1; the functional analysis is described below and the structural-functional analysis is summarised in . Each function’s heading below (in bold) states its aspirational interpretation as a benchmark of what each function should achieve in this study’s context.

Table 4 Summary of the functional-structural analysis of creating an enabling environment for local industries to pursue AWM as part of a systems approach (SA).

F1: Entrepreneurial activities – Local industries are empowered to identify and adopt new opportunities. Opportunities are readily available.

Different forms of entrepreneurial activities were evident. Box 2 provides a prime example of private entrepreneurial, industry-wide activity in the Australian cherry industry. As found elsewhere in Australia’s techno-centric innovation context (CitationNettle et al., 2013), it represents an informal governance system stimulating innovation by engaging with grower target groups and other key actors thereby enabling “routes to change”. It reportedly enjoys high grower and government support. Some regions, such as Young-Harden, pursue local-specific opportunities, such as working towards a domestic trade window based on demonstrable low QFly-prevalence during most of the cherry harvest season. Some interviewees pointed out that local industries that are demonstrably proactive, well-organised and who show resolve are more likely to secure support than those less organised.

Key challenges include limited understanding among growers about market access rules. Interviewees spoke about achieving AWM being onerous, especially gaining wide-spread support from all risk contributors, including town residents and peri-urban landholders (CitationKruger, 2017). Someone mentioned that “you need a lot of ducks lined up” and that “before you can negotiate market access, you need the system…to be up, running, established and working repeatedly”. Accessing QFly-sensitive markets places considerable demands for infrastructure investment. For example, orchards, packing houses and storage facilities need to be certified as meeting the necessary requirements. Initiating and running systems approaches and AWM also require extensive data gathering to demonstrate adequate QFly control. Systems are needed to prevent infestation while fruit is being transported. “Back-up” systems, such as cold treatment, are required if the systems approach fails.

Box 2 Working towards better market access options for the Australian cherry industry.

Cherry Growers Australia (CGA) is driving a concerted effort to assist cherry growers to be “export ready”. It works closely with the industry’s lead research agency, the Tasmanian Institute of Agriculture (TIA) to support growers. A TIA researcher coordinates a project committee with representation from all state associations. The committee ensures local industry needs are linked with opportunities and requirements at higher levels, through a cyclical process of giving and receiving input and feedback from and to regions.

The TIA researcher also coordinates a national extension program that is closely linked to the cherry industry’s market access-related biosecurity management program (BMP). Trust-based relationships have been a priority throughout this work.

Consultants develop the BMP by drawing together different forms of knowledge. These include market access rules, varying needs of regions and market access arrangements developed elsewhere, while ensuring the program is aligned with market access systems being developed by state governments. They liaise closely with growers, different state and federal government officials and other relevant actors. The consultants provide a single point of contact for growers about market access issues and form an interface between growers and the Australian Department of Agriculture and Water Resources (DAWR). The consultants and researcher adjust their communication with local industries based on growers’ existing knowledge.

There were challenges resulting in transaction costs to industry. These include the consultants needing to spend much time and effort on obtaining historical trapping data from some state governments; getting key decision-makers from different government bodies together to liaise and make joint decisions; liaising with a wide range of actors; and prompting actors to find solutions to challenges the consultants had no control over. Government staff turnover complicated maintaining consistent relationships.

Progressing market access requires liaising with many actors, whether it is pursued by a local industry representative, an industry body or a consultant.

Having the right people in the same room at the same time seems to be one of those things that if you can pull that off and start getting the various experts or people who have experience in those fields—or I guess the level of authorization because it is their decision—all talking together, that is most helpful. [Consultant]

Some interviews posited that dealing with QFly could be strengthened through greater institutional harmonisation between states. For example, acceptance of domestic trade protocols as part of the Interstate Certification Assurance (ICA) scheme, across all states, will contribute to clearer and more consistent guidance at the local level.

F2: Knowledge development – Knowledge is developed that will equip local industries to harness new opportunities and maintain current markets.

As Box 1 illustrates large investments are made in research projects related to QFly. The National Fruit Fly RD&E plan identifies investment in systems approach-related research for market access as a priority, including both basic science and successful field examples that can be used as exemplars (CitationPlant Biosecurity CRC, 2015).

Key challenges that interviewees identified include information gaps, such as the development of verifiable protocols, including thresholds (e.g. numbers of QFly caught in trap) that would trigger growers to take corrective action. Several spoke about the difficulty of statistically proving how different QFly-control mechanisms combined in a systems approachFootnote1 will deliver a continued pest-free product (CitationJamieson et al., 2013).

F3: Knowledge diffusion – All existing information that could assist local industries to achieve and maintain domestic and international market access is readily available to them. Information from the regional level is readily reaching policy-makers.

Designing a workable systems approach requires holistic input, including combined on-farm, funding, regulatory, market and government perspectives. Some interviewees pointed out that market access protocols that are developed together with local industries are most likely to be used by growers, such as in Central Burnett (CitationLloyd et al., 2010) and the recent progress made by the cherry industry (Box 2).

Specially appointed state government officers supported local industries in their market access pursuits. While described as “thinly spread” across many regions, they played an important brokerage role in assisting some local industries to develop new trade protocol applications.

The Australian Government’s DAWR is the main holder of expertise about international market access, whereas state governments’ key focus traditionally has been domestic market access. Interviewees talked about the direct contact between state government staff working directly with growers and staff negotiating domestic market access. This assists two-way negotiation between trading partners to ensure protocols are practical to growers and supply chain members, and meet market needs. Such short communication loops are less prevalent for international market access proposals. Here proposals need to be considered by a specially appointed expert group under the auspices of HIAL that recommends to DAWR which proposals need to be pursued for negotiation. There can be a considerable lag between the last industry input and a protocol being negotiated. Several interviewees would like to see more opportunity for industry input close to or during international bilateral negotiations. Several export protocols are not utilised in part because growers regard them as impractical or uneconomical to implement. Some pointed out that changing approved protocols requires considerable time, cost and evidence-gathering that diverts resources from opening new markets.

Until recently, DAWR’s communication to growers about international market access was mainly via peak industry bodies and through information provided on the internet. Some DAWR interviewees mentioned that the need for strengthening direct communication with local industries, states government and consultants has been recognised. The horticultural industries are developing export strategies, with feedback from DAWR, including identifying key knowledge gaps and goals. DAWR has launched initiatives to build state governments’ knowledge of relevant international trade matters. Increasingly domestic trade is modelled on international trade arrangements. Over time successful domestic protocols then build evidence to support international market access applications using the same protocol.

The survey results suggest that growers have high hopes of AWM as part of a systems approach to underpin international trade. The survey asked export-oriented growers to rate to what extent they agree with the statement “An area of low pest prevalence (ALPP) is valuable in negotiating international market access as part of a systems approach.” An ALPP is a formal pest risk mitigation measure and is often underpinned by AWM. Across all respondents, 92 percent (55 out of 60 respondents) agreed, with 75 percent strongly agreeing and 17 percent somewhat agreeing. By contrast, interviewees operating closer to the trade negotiations arena are sceptical about current international acceptance of systems approaches and ALPPs for fruit fly host commodities (see F5: Market formation).

Key challenges include the difficulty of maintaining strong linkages between DAWR and local industries, including a lack of short communication loops during trade protocol negotiations. Several interviewees want DAWR to work closer with local industries to strengthen local understanding about international market access rules. Some suggested that effective communication between peak industry bodies and all growers cannot always be assumed. Relying on webpages involve challenges, e.g. DAWR lists export-related information on-line, but many growers need help understanding it and some information can only be obtained from trading partners. Governments’ interactions with growers are affected by government staff turnover, resulting in lost nuanced knowledge about their region’s QFly situation and trade opportunities.

Few actors understand the entire system, that is, from the perspectives of QFly entomology, the complexities of on-ground QFly management, developing export protocols and the associated research required, the trade negotiation processes and delivering a consistent product. Someone mentioned that “there are so many bits to it and there are not a lot of people who are knowledgeable about all those things”.

Some interviewees mentioned that actor groups speak “different languages”, for example, entomologists use different terminology than market access staff. Many entomologists and crop consultants have only “passing knowledge” of international plant protection rules. Some growers misinterpret what is feasible in the trade context leading to false expectations, for example, by believing that they can supply anywhere because they have consistently produced QFly-free produce.

National government committees might predominantly focus on meeting international trade obligations and other countries’ requirements.

They’ve [advisory body] got a lot of issues on high priority like area-wide management and systems approaches but I think there’s a lack of understanding of how difficult it actually is to establish some of these systems approaches. [State government official]

As found by CitationHiggins et al. (2016), some interviewees remarked that local industries do not feel listened to, despite persistent lobbying efforts by peak industry bodies. Others pointed to a lack of growers using their agri-political voices. Growers’ limited understanding of the international trade arena means that they can easily underestimate the amount of effort governments and industry bodies invest in securing and maintaining trade.

F4: Guidance of the search – A clear vision exists at the local and the higher QFly management innovation system levels that AWM and systems approaches are key ways forward and will enjoy commitment and support as long term goals.

As Box 1 illustrates, all key QFly-related strategic documentation include the promotion of AWM and systems approaches. Yet, they need strong technical and logistical support to operate (CitationHendrichs et al., 2007). State governments are key players in assisting local industries with systems approaches, with some success and a number of domestic trials underway. A strong theme amongst interviewees was that market access initiatives should start in the regions (“bottom-up”). This includes growers developing a shared vision and making their wishes known to government. Different groups, for example, the then National Fruit Fly Advisory Committee (predecessor of the National Fruit Fly Council) and Cherry Growers Australia (CGA), are developing a toolbox of QFly-management practices that growers can use as part of a systems approach. Local QFly management groups typically form to work with key actors to develop a shared vision and to lead the local industry to strengthened market access (CitationKruger, 2016). Growers’ trust in a management group’s ability to capitalise on market access opportunities is essential to achieve local support and cooperation. Trust here can be conceptualised as a function of the ability (“know how to” and “can do”) and the willingness (“want to”) of the management group to fulfil its functions (CitationGraham, 2014). The survey asked respondents to rate to what extent they agree or disagree with three statements about their local AWM management group based on these functions of trust. Overall trust levels were very high (). Trust rated least—albeit still high— for the management groups’ capability to improve market access. This suggests that respondents are confident that their management groups possess the necessary knowledge about market access and are motivated to work toward this goal, but there is hesitation about whether management groups have established effective interactions with the right government officers. Note that the study did not measure local management groups’ actual abilities to fulfil these functions.

Table 2 Growers’ trust in their management groups’ ability to assist them in overcoming QFly-related market access issues.

Key challenges include that clear guidance lacks on how to initiate AWM and systems approaches. When interviewees were asked how they think local industries can go about it, responses varied considerably. Some believed that local industries’ first point of call should be their local government, others thought state government and others growers’ peak industry body. Interviewees spoke about relevant ISPMs being vague, lacking the needed detail for clear direction; and limited examples of international systems approaches for fruit flies exist that local industries can draw upon. There is tension between the need for harmonised procedures that will satisfy markets and for AWM programs to be locally adapted.

You need a regional approach…but there needs to be sort of cohesion amongst the regions so that we don’t have wildly different schemes going be put forward for market access. [Australian Government representative]

Currently no nationally agreed management principles for ALPPs for fruit flies exist, although discussions with state and federal governments, industry and researchers are ongoing. Attaining a shared vision is challenged in local industries where there is high heterogeneity and/or fragmentation (CitationKruger, 2017).

F5: Market formation – Profitable markets are available to local industries based on workable systems approach protocols.

The ICA system was generally seen as a big success for domestic market access. Some were hopeful that AWM as part of a systems approach could assist in overcoming the need for costly post-harvest QFly treatments for international trade as is the case for some ICAs (CitationKruger, 2016).

Gaining or improving international market access can be difficult and lengthy processes. Interviewees spoke about countries having different phytosanitary requirements and occasionally some country requirements change. Several interviewees believed politics and protectionism, along with scientific evidence, influence market access decisions. A state government representative pointed out that “you always hope that putting the science forward is going to be enough” but that “there’s always an alternative viewpoint that someone can argue…to refute what you’re saying”.

Key challenges that interviewees identified include that most markets prefer simple single treatments such as the now restricted chemicals, or costly post-harvest treatments. Systems approaches are not well accepted in international trade (CitationJamieson et al., 2013). An industry body representative mentioned that “we do need to keep exploring [systems approaches] because the pest is not going to go away”.

Regional trade protocols involving in-field QFly management measures often require regular pest surveillance data based on monitoring a “trapping grid” across the region. Under international trade rules, government is currently recognised as the only independent monitor. Due to restricted state government funding, accepted third-party monitoring is being discussed. Several interviewees were concerned that the cost to industry to fund such a service could render trade arrangements uneconomical.

Another source of concern was that if Australia desires other countries to accept systems approaches without end-point treatments for Australian export horticulture, Australia needs to be open to accepting similar systems approaches to underpin horticultural imports. Acceding to this could cause a backlash from some Australian horticultural industries.

F6: Mobilization of resources – Resources are readily available to industries to develop and implement systems approaches and AWM.

Recent Australian Government funding opportunities, such as the Package Assisting Small Exporters, are opening opportunities for some local industries to pursue systems approach protocol development. However, a key theme was that a lack of investment from both government and industry hampers progress. Interviewees mentioned that clear signals that AWM and systems approaches make economic sense are fundamental for grower buy-in. This is especially true, given Australia’s reliance on market-driven approaches with minimal agriculture protection and support (CitationHiggins et al., 2016). Grower investment is further hindered when profitability is low and competing priorities exist for grower funding. Several funding opportunities are unfavourable for AWM (CitationKruger, 2017). Interviewees mentioned that some state government funding models fully allocate staff time to existing projects so that staff have little time to assist industries with developing new project ideas and funding proposals. Others said that the ongoing need to monitor and verify that a systems approach’s different components are working as intended, makes them expensive to run.

F7: Creation of legitimacy – The QFly management innovation system instils trust in growers that it can provide the needed support and that AWM and systems approaches are viable options.

The survey investigated the levels of trust that growers have towards state and federal governments (). Like others identified (e.g. CitationHiggins et al., 2016), trust in government lacks, except when recent close cooperation occurred, such as in Young Harden where the state department was assisting growers with a domestic systems approach trial. Direct interaction tends to foster mutual trust (CitationBusse et al., 2015). Overall, growers’ trust in state governments is higher than in the Australian Government, but it appears most compromised in growers’ views about governments’ willingness to support them.

Table 3 Percentage of growers who agree that government is supportive in overcoming QFly issues hindering market access.

Other key challenges include that policy-makers might lose legitimacy when they lack understanding of on-ground challenges. The lack of local-level understanding about the trade arena suggests that many growers do not appreciate the large investments government and industry bodies make to facilitate trade.

5 Discussion

The functional-structural analysis presents a snapshot in time. However, it demonstrates that considerable challenges exist—other than technological deficiencies—that prevent QFly AWM as part of a systems approach to become an established trade-supporting measure in Australian horticulture.

The problems identified were investigated for interconnected elements or clusters, representing blocking mechanisms (adjusted from CitationTurner et al., 2016) that hinder local industries from embracing AWM and systems approaches.

First, there is a lack of clear change pathways for local industries interested in pursuing AWM and systems approaches. Hence, the innovation system creates insufficient conditions for entrepreneurial activities to flourish (CitationHekkert et al., 2007; CitationKruger, 2017). Lacking capability is a common AIS weakness (CitationKlerkx et al., 2012). CitationKruger (2017) identified low local capability to achieve AWM for QFly suppression. Many growers also have limited understanding of international trade rules; nationally agreed procedures for ALPPs are still being developed, and relevant international standards are regarded as vague. While state governments and peak industry bodies make considerable contributions, capacity is limited to assist local industries with identifying and pursuing new trade pathways. Information is not easily accessible, for example, several growers find trade-related information provided on the internet hard to interpret for their situation.

Second, low system connectivity, or weak network failure (CitationKlerkx et al., 2012), means several local industries are weakly connected with the broader QFly management innovation system. This limits effective knowledge diffusion between local industries and the innovation system as well as amongst local industries, thereby preventing the holistic approach needed to progress innovation (CitationNederlof et al., 2011). This is evident from the different expectations across levels about the acceptance of ALPPs as part of systems approaches for international trade. Industry is seen as too removed from international trade negotiation process and this could cause impractical trade protocols. There is possible under-appreciation of the complexity of AWM and systems approaches at higher levels and an under-appreciation at the local level of the investments governments and industry bodies make to facilitate trade. Fragmentation between actor groups result in silo-ed knowledge and “languages”.

Third, a lack of feasibility signals challenges the demand for proposed solutions, that is, when it is not clear that they make economic sense and seem achievable (CitationBusse et al., 2015). When AWM is used as part of a systems approach, it requires considerable logistical systems to be put in place (see F1 under 4. Results). Concerns exists that the cost to industry involved in potential third-party monitoring of trapping grids may make them uneconomical to use. For industry representatives to deal with various actors at different levels in industry and government, and to initiate joint decision-making between key actors, come at considerable transaction costs.

Fourth, systems approaches are problematic, including the difficulty to statistically prove their effectivenessi, low market acceptance and potential industry back-lash if Australia needs to accept systems approaches for imports. Factors other than scientific evidence accompanying a market access application can influence negotiations. Addressing this issue falls outside the scope of this article. The lack of feasibility signals and systems approaches being problematic hinder entrepreneurial activity, resource mobilisation and the legitimacy of AWM and systems approaches.

More broadly, this work shows that the modern-day biosecurity push for harmonisation and categorisation is challenged by regional differences. Local industries can be easily left behind in the biosecurity journey if they are not well-connected to the broader innovation system.

5.1 Recommendations for policy intervention

The recommendations provided here are not an exhaustive list, but rather they begin a process to alleviate some of the key pressures on local industries. sketches the blocking mechanisms’ impact on the innovation functions and where the proposed policy interventions can alleviate these issues. Other relevant recommendations are also made by CitationKruger (2017), in particular the need for knowledge brokering and co-regulation to secure a sustainable funding stream for AWM.

5.1.1 Instigate and support interconnected innovation platforms

This can address the low system connectivity, improve co-production of knowledge and lead to clearer market access pathways for local industries. Innovation platforms refer to the deliberate creation of spaces where heterogeneous actors interact to undertake information-sharing, knowledge-development and implementation activities to solve a common problem. This enables co-evolving technical, social and institutional components in the innovation system (CitationKilelu et al., 2013).

Local QFly management groups represent innovation platforms where different knowledge systems meet, e.g. representatives from growers, packhouses, local government, crop consultants and state government (CitationKruger, 2016). Here they develop coordinated QFly initiatives suitable for the regional context in pursuit of strengthening trade. The grower survey suggests that growers’ trust in their local management group tends to be high.

Policy intervention is therefore required to ensure local management groups are well-connected with higher level bodies and research groups involving multi-directional information to and from local industries. Given the different roles of the Australian and state/territory governments, it suggests that there is a need for inter-connected platforms across different levels, such as at the local, state or national levels (CitationNederlof et al., 2011). The design of such intervention is best negotiated amongst key actors, such as local management group representatives, research groups, industry bodies and market access government staff. This is to meet their needs and expectations, ensure maximum buy-in, and to enable a good fit with existing structures. Effective intermediation between groups is vital to ensure effective coordination, information brokerage and resolving tensions (CitationKilelu et al., 2013). Well performing innovation platforms are likely to increase actors’ trust in the innovation system and strengthen the guidance in the search and legitimacy of AWM and systems approaches amongst local industries.

5.1.2 Offer training opportunities

Currently knowledge about market access is concentrated amongst a relatively few actors in government and industry bodies. This knowledge base can be broadened by offering training to people operating at the local level, such as management group members and crop consultants; and private consultants interested in assisting industries with pursuing trade to protocol countries. This will contribute to a bigger support network that can guide local industries on change pathways and can also strengthen the capability of local actors and others to participate in the co-production innovation process based on a more shared language (CitationBusse et al., 2015). Training opportunities could involve a joint initiative between the Australian Government, state governments and national coordinating bodies to ensure international and domestic market access is covered. A module on softer skills, such as negotiation, facilitation and conflict resolution, could further equip individuals with guiding local industries to improved market access.

5.1.3 Minimise transaction cost to industry

This can strengthen the feasibility signals of QFly AWM and industry’s ability to be more self-reliant by minimising the time and effort that industry representatives need to spend to gain cooperation and support from key actors. Examples include making it easier for industry to get the “right people” in one room or accessing past government QFly-trapping data. Other opportunities for improvement include further strengthening stakeholder coordination; minimising the effect of staff changes, fostering a client-oriented ethos and strengthen grower guidance, in particular by regularly updating nationally agreed fruit fly management principles and procedures to reflect advances in science.

6 Conclusion

This article explored how to create a more enabling environment for local horticulture industries to pursue AWM of QFly as part of a systems approach. It comprises a complex domain that is multi-levelled and multi-faceted, and where innovation co-production through effective negotiation processes is essential to develop trade-related systems that meet both the needs of growers and markets.

This work has demonstrated that a functional-structural analysis is a powerful tool to identify what else is required beyond technological advances to ensure investment in innovation translates into industry progress. Capacity-building and local industries well-connected with the broader innovation system stand the best chance to overcome the challenges of lacking clear change pathways, low system connectivity and lack of feasibility signals. The analysis illustrates that the transition towards shared responsibility requires a rethink of the innovation system to minimise transaction cost to industry, rather than the mere transfer of certain tasks from government to industry.

Prudent next research steps include stakeholder consultation to inform the design of innovation platforms and/or other ways to strengthen the interconnectedness of the QFly management innovation system, especially with the local level. This could be informed by a social network analysis that investigates how information currently flows formally and informally throughout the system and to understand the position of actors in the system (CitationKlerkx et al., 2012). Given the expectation that the private sector will deliver services traditionally provided by government, a deeper investigation is needed into the skills and support that private entities, such as consultants, need to effectively support local industries in their QFly-affected market access pursuits.

Disclosure statement

I, Heleen Kruger, receive no financial interest or other benefit arising from the direct applications of this research. This research has been conducted in partial fulfilment of a PhD.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the support of the Australian Government’s Cooperative Research Centres Program. I am grateful to all interviewees and survey participants for their participation. Many thanks to my supervisors for feedback and suggestions, including Prof Darren Halpin (Australian National University), Prof Rolf Gerritsen (Charles Darwin University) and Dr Susie Collins (Australian Government Department of Agriculture and Water Resources (DAWR)). I am most indebted to Dr Pat Barclay for her considered feedback. Thank you to Dr Craig Hull (DAWR) for constructive suggestions. My gratitude also goes to the two anonymous reviewers who provided valuable suggestions to strengthen this article.

Notes

1 Just before publication of this article, HIAL instigated a project that aims at quantifying the different steps in systems approaches.

References

- AbaresDepartment of Agriculture and Water ResourcesAgricultural Commodity Statistics 20152015Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and SciencesCanberra

- A.BergekS.JacobssonB.CarlssonS.LindmarkA.RickneAnalyzing the functional dynamics of technological innovation systems: a scheme of analysisRes. Policy372008407429

- G.A.BowenDocument analysis as a qualitative research methodQual. Res. J.920092740

- M.BusseW.SchwerdtnerR.SiebertA.DoernbergA.KuntoschB.KönigW.BokelmannAnalysis of animal monitoring technologies in Germany from an innovation system perspectiveAgric. Syst.13820155565

- M.DenscombeThe Good Research Guide: for Small-scale Social Research Projects2014Open University PressBerkshire, UK

- N.K.DenzinY.S.LincolnIntroduction: the discipline and practice of qualitative researchN.K.DenzinY.S.LincolnHandbook of Qualitative Research2nd ed.2000Sage PublicationsThousand Oaks, California, United States

- B.C.DominiakJ.H.EkmanThe rise and demise of control options for fruit fly in AustraliaCrop Prot.5120135767

- K.M.EisenhardtM.E.GraebnerTheory building from cases: opportunities and challengesAcad. Manage. J.5020072532

- G.EnticottThe spaces of biosecurity: prescribing and negotiating solutions to bovine tuberculosisEnviron. Plann. A40200815681582

- S.GrahamA new perspective on the trust power nexus from rural AustraliaJ. Rural Stud.3620148798

- M.P.HekkertR.A.SuursS.O.NegroS.KuhlmannR.E.SmitsFunctions of innovation systems: a new approach for analysing technological changeTechnol. Forecasting Soc. Change742007413432

- J.HendrichsP.KenmoreA.RobinsonM.VreysenArea-wide integrated pest management (AW-IPM): principles, practice and prospectsM.VreysenA.RobinsonJ.HendrichsP.KenmoreArea-wide Control of Insect Pests: from Research to Field Implementation2007SpringerNetherlands

- V.HigginsM.BryantM.Hernández-JoverC.McshaneL.RastHarmonising devolved responsibility for biosecurity governance: the challenge of competing institutional logicsEnviron. Plann. A48201611311151

- L.JamiesonH.DesilvaS.WornerD.RogersM.HillJ.WalkerS.ZydenbosA review of methods for assessing and managing market access and biosecurity risks using systems approachesN. Z. Plant Prot.66201319

- A.JessupB.DominiakB.WoodsC.DE LimaA.TomkinsC.SmallridgeArea-wide management of fruit flies in AustraliaArea-wide Control of Insect Pests2007Springer

- E.KebebeA.DuncanL.KlerkxI.DE BoerS.OostingUnderstanding socio-economic and policy constraints to dairy development in Ethiopia: a coupled functional-structural innovation systems analysisAgric. Syst.14120156978

- C.W.KileluL.KlerkxC.LeeuwisUnravelling the role of innovation platforms in supporting co-evolution of innovation: contributions and tensions in a smallholder dairy development programmeAgric. Syst.11820136577

- L.KlerkxC.LeeuwisMatching demand and supply in the agricultural knowledge infrastructure: experiences with innovation intermediariesFood Policy332008260276

- L.KlerkxR.NettleAchievements and challenges of innovation co-production support initiatives in the Australian and Dutch dairy sectors: a comparative studyFood Policy4020137489

- L.KlerkxN.AartsC.LeeuwisAdaptive management in agricultural innovation systems: the interactions between innovation networks and their environmentAgric. Syst.1032010390400

- L.KlerkxB.Van MierloC.LeeuwisEvolution of systems approaches to agricultural innovation: concepts, analysis and interventionsI.DarnhoferD.GibbonB.DedieuFarming Systems Research into the 21st Century: the New Dynamic2012Springerfgfg

- H.KrugerAdaptive co-management for collaborative commercial pest management: the case of industry-driven fruit fly area-wide managementInt. J. Pest Manage.2016112

- H.KrugerCreating an enabling environment for industry-driven pest suppression: the case of suppressing Queensland fruit fly through area-wide managementAgric. Syst.1562017139148

- A.LloydE.L.HamacekR.A.KopittkeT.PeekP.M.WyattC.J.NealeM.EelkemaH.GuArea-wide management of fruit flies (Diptera: tephritidae) in the Central Burnett district of Queensland, AustraliaCrop Prot.292010462469

- A.MalavasiIntroductory remarksT.ShellyN.EpskyE.B.JangJ.Reyes-floresR.VargasTrapping and the Detection, Control, and Regulation of Tephritid Fruit Flies – Lures, Area-wide Programs, and Trade Implications2014Springer

- D.MayeJ.DibdenV.HigginsC.PotterGoverning biosecurity in a neoliberal world: comparative perspectives from Australia and the United KingdomEnviron. Plann. A442012150168

- Agricutural innovation platformsS.NederlofM.WongtschowskiF.Van Der LeePutting Heads Together: Agricultural Innovation Platforms in Practice2011KIT Publishers, KIT, Development, Policy & PracticeAmsterdam, The Netherlands

- R.NettleP.BrightlingA.HopeHow programme teams progress agricultural innovation in the Australian dairy industryJ. Agric. Educ. Extension192013271290

- PHADraft national fruit fly strategyA Primary Industry Health Committee Commissioned Project2008Plant Health AustraliaCanberra

- Plant Biosecurity CRCNational Fruit Fly Research, Development and Extension Plan2015Plant Biosecurity Cooperative Research CentreBruce, ACT

- N.RölingD.HounkonnouD.KossouT.KuyperS.NederlofO.Sakyi-DawsonM.TraoréA.Van HuisDiagnosing the scope for innovation: linking smallholder practices and institutional context: introduction to the special issueNJAS–Wageningen J. Life Sci.60201216

- M.SchutJ.RodenburgL.KlerkxA.Van AstL.BastiaansSystems approaches to innovation in crop protection. a systematic literature reviewCrop Prot.56201498108

- M.SchutJ.RodenburgL.KlerkxL.C.HinnouJ.KayekeL.BastiaansParticipatory appraisal of institutional and political constraints and opportunities for innovation to address parasitic weeds in riceCrop Prot.742015158170

- J.A.TurnerL.KlerkxK.RijswijkT.WilliamsT.BarnardSystemic problems affecting co-innovation in the New Zealand agricultural innovation system: identification of blocking mechanisms and underlying institutional logicsNJAS–Wageningen J. Life Sci.76201699112

- A.J.WieczorekM.P.HekkertSystemic instruments for systemic innovation problems: a framework for policy makers and innovation scholarsSci. Public Policy3920127487

- R.YuThe economics of area-wide pest management2006Doctor of Philosophy in EconomicsUniversity of Hawaii