Abstract

Agricultural extension in sub-Saharan Africa has often been criticised for its focus on linear knowledge transfer, and limited attention to systemic approaches to service delivery. Currently, the region is experiencing a new-ICT revolution and there are high expectations of new-ICTs to enhance interaction and information exchange in extension service delivery. Using an innovation systems perspective, we distinguish the roles demand-articulation, matching demand and supply, and innovation process management for innovation-intermediaries. The study explores literature on how new-ICT may support these roles, with specific interest in the possibilities of environmental monitoring and new forms of organisation enabled by enhanced connectivity. In order to contribute to the understanding of this area, the paper reports on a comparative study of two new-ICT platforms embedded in Ghanaian public and private extension organisations respectively. We assess the roles that these platforms (aim to) support, and document achievements and constraints based on interviews with extension staff and farmers. The findings indicate that while both platforms aim to support innovation-intermediation roles the focus areas and level of detail differ due to diverging organisational rationales to service delivery. In addition, we see that new-ICTs' potential to support innovation-intermediation roles is far from realised. This is not due to (new) ICTs lacking the capacity to link people in new ways and make information accessible, but due to the wider social, organisational and institutional factors that define the realisation of their potential. Therefore, more conventional modes of interaction around production advice and also credit provision continue to be dominant and better adapted to the situation. However, beyond the two platforms that were developed specifically by and for the extension organisations, there were indications that more informal and self-organised new-ICT initiatives can transform and enhance interaction patterns in innovations systems to achieve collective goals through standard virtual platforms such as WhatsApp and Telegram.

1 Introduction

Despite agriculture's potential to contribute to the growth of sub-Saharan African economies (CitationAker, 2011), agricultural production in the region remains less than optimal (CitationAker, 2011; CitationMcIntrye et al., 2009). Factors explaining low levels of productivity include not only rainfall variability and environmental degradation, but also a range of socio-political and institutional conditions (CitationPretty et al., 2011; CitationMcIntrye et al., 2009), including limitations in agricultural extension service delivery mechanisms (CitationSwanson and Rajalahti, 2010; CitationDavis, 2008; CitationLeeuwis, 2004). Agricultural extension has often been criticised for its focus on linear knowledge transfer and limited attention to systemic approaches to service delivery (CitationLeeuwis and Aarts, 2011; CitationDaane, 2010) that would include broader innovation-intermediation roles such as process facilitation and knowledge brokering (CitationSwanson and Rajalahti, 2010; CitationHowells, 2006).

Specifically, classical extension has been criticised for its poor capacity to engage multiple interdependent actors (farmers, credit and input providers, buyers, researchers, and development organisations) in joint problem-solving, and in improving farmers’ access to broader information relating to market and credit linkages (CitationKlerkx et al., 2012; CitationKilelu et al., 2011). Further, extension has been associated with limitations in synthesising agronomists, extension agents and farmers’ knowledge, and locality-specific information (socio-economic and bio-physical data), to embed appropriate technologies in farm management (CitationKarpouzoglou et al., 2016; CitationLambrecht et al., 2015; CitationLeeuwis, 2010). The above critique and need for new organisational arrangements in extension is amplified by the increasing complexity of the challenges that agriculture is facing due to climate change, and new demands and standards arising in value chains (CitationMcIntrye et al., 2009; CitationKlerkx and Leeuwis, 2009).

Over the years funding for public extension in many underdeveloped sub-Saharan African countries has been limited (CitationPretty et al., 2011; CitationBennett, 1996). This has led to inefficiencies in extension service delivery, and a response to this has been the emergence of private extension to supplement government efforts (CitationSwanson and Rajalahti, 2010; CitationDavis, 2008). However, despite the emergence of pluralistic extension systems challenges in agricultural innovation systems have remained. For both public and private extension organisations, it remains difficult to facilitate the appropriate interaction among stakeholders to address technical and institutional challenges in farming, reach vast numbers of farmers, and contribute to capacity building at scale (CitationSwanson and Rajalahti, 2010; CitationMcIntrye et al., 2009).

Alongside the emergence of pluralistic extension systems in sub-Saharan Africa, the region is experiencing a new-ICT revolution driven by increasing access to mobile devices. New-ICT specifically refers to online-mobile based messaging applications (e.g., WhatsApp), Short Message Service (SMS) mobile push and pull services, and mobile data collection and digital storage applications (e.g., open data kit) that enable the exchange of textual, audio, video and pictorial information between two or more actors (CitationBarber et al., 2016; CitationBell, 2015). The emergence of these applications presents new opportunities for information sharing and alternative forms of connectivity (CitationVan et al., 2017; CitationWitteveen et al., 2017; CitationDanes et al., 2014; CitationKarpouzoglou et al., 2016; CitationVan Vliet et al., 2014; CitationBennett and Segerberg, 2012). In development practice this era, coined Information Communication Technology for Development (ICT4D) 2.0, is characterised by new-ICTs with social transformational capacity that positions users as information co-producers rather than consumers and enables online networks (CitationLie and Servaes, 2015; CitationHeeks, 2009; CitationUnwin, 2009). In this context there are high expectations of new-ICTs to enhance interaction and information exchange in extension service delivery and other forms of innovation-intermediation. Possibilities include enabling virtual communities for stakeholders to engage in learning and joint problem solving, facilitating virtual connectivity to improve farmers’ linkages to services, and the collection of timely and locality-specific information to localise generic scientific knowledge and improve the response to emergent issues (CitationWright et al., 2016; CitationAker, 2011; CitationMcCole et al., 2014; CitationAmadu and McNamara, 2014; CitationSwanson and Rajalahti, 2010; CitationDavis, 2008). However, little is known about how new-ICTs are used in practice to address challenges in agricultural innovation systems.

This paper studies two new-ICT platforms in Ghana embedded in a public and private extension organisation respectively, whereby the term ‘platform’ refers to the base upon which multiple applications are developed and integrated. The paper analyses the innovation-intermediation roles both platforms aim to support, reports on user experiences and actual platform usage, and documents the interplay between (new) ICT use and the broader innovation systems landscape. In doing so the paper aims to identify constraints and opportunities related to these platforms facilitating innovation-intermediation, and draws lessons for further research and new-ICT platform development.

2 Conceptual framework

Our research on new-ICT platforms is founded on literature that connects to the functioning of agricultural innovation systems, i.e. the network of organisations and enterprises that are relevant to developing, exchanging, and utilising knowledge, technology and innovation in the sector, including the institutions and policies that affect the interactions among these actors and the eventual outcomes (CitationSchut et al., 2014; CitationKlerkx and Gildemacher, 2012; Klerks et al., 2009; CitationHowells, 2006).

2.1 Innovation intermediation

Over the last decade climate change and soil degradation effects, in interaction with human factors and societal development, have dis-oriented traditional farming systems and made farming more complicated (CitationSchut et al., 2014; CitationMcIntrye et al., 2009). This has placed a higher demand on agricultural stakeholders to adapt and respond to simultaneous challenges and multiple goals for the sector to remain viable and sustainable (CitationSwanson and Rajalahti, 2010; CitationLeeuwis, 2010; CitationKlerkx and Leeuwis, 2009). This situation has placed added pressure on extension organisations to engage in systemic approaches that link them effectively to broader dynamics and innovation support services (CitationKlerkx et al., 2012; CitationLeeuwis and Aarts, 2011; CitationDaane, 2010).

CitationKlerkx et al. (2012) have argued that extension organisations may usefully engage in a broader set of innovation-intermediation roles to enhance the innovation systems performance. Innovation-intermediation relates to three roles described in below.

Table 1 Roles of Innovation Intermediaries.

The roles are 1) demand-articulation: engaging sector stakeholders to identify their (tacit and expressed) needs (technical, funding or policy), and facilitating the participatory assessment of constraints in meeting their needs and surfacing of interdependencies (Klerkx and Gildemacher, 2012: 2) matching demand and supply: establishing sector contacts (scanning, scoping and filtering actors), identifying potential partnerships that match demand and supply or harness resource complementarity, and developing mutually beneficial relationships (CitationHowells, 2006); and 3) innovation process management: creating a discussion and negotiation space for actors to jointly mitigate constraints. This includes maintaining relationships (fostering continuous information flows, trust building and conflict resolution) among stakeholders to cushion mutual benefits (e.g., in credit and markets), and on-going facilitation of knowledge sharing (graduating from learning, knowledge integration to knowledge co-creation) for continuous innovation (CitationHakanson et al., 2011; CitationLeeuwis, 2010).

2.2 New-ICT potential for innovation intermediation

While many public and private organisations in Africa are working towards operationalising systemic extension approaches, their capacity to perform and enhance the intermediation functions mentioned above (CitationSwanson and Rajalahti, 2010) remains a challenge (CitationBell, 2015; CitationMcIntrye et al., 2009).

As mentioned in the introduction, it has been argued that new-ICTs can act as a bridging mechanism (CitationProulx and Heaton, 2011; CitationStone, 2011) and enhance innovation-intermediation roles. In the sphere of ‘demand-articulation’ they may facilitate interaction between demand and supply-side stakeholders in various locations on virtual platforms, to engage them in sharing viewpoints, experiences and knowledge relevant to clarifying needs and constraints.

Additionally, new-ICTs offer opportunities for the creation of timely monitoring systems that support the detection of emerging issues in the field, enabling extension organisations or value chain actors to respond to issues promptly (CitationMcCole et al., 2014). The development of such systems involves engaging local agents (e.g., farmers) in collecting data on their on-going activities and challenges, through mobile applications. These data are linked to databases with interfaces that present data in an accessible manner (CitationMcCole et al., 2014; CitationBuytaert et al., 2014).

This decentralised monitoring of farming activities and data crowdsourcing resonates with forms of citizen science (CitationCieslik et al., 2017) where information of societal stakeholders may be used to set agendas for innovation and problem-solving. Citizen science is the involvement of ordinary people in scientific knowledge production through engagement in data collection and (or), data analysis (CitationStevens et al., 2014), therefore facilitating the collection of more observations over a wider geography and expanding possibilities for scientific investigation (CitationCieslik et al., 2017; CitationVan Vliet et al., 2014).

Such decentralised collection of locality-specific information (e.g., soil fertility data) may also support tailoring of advice and other forms of service delivery (CitationLeeuwis, 2004), and therefore support ‘matching demand and supply’ functions. Also in this area, new-ICTs are expected to enhance farmers’ and agents’ access to various information. SMS mobile applications may for example support immediate access to market information, weather data, production advice, and information related to financial services (CitationBarber et al., 2016; CitationQiang et al., 2012).

In relation to ‘innovation process management’, the expectations are that new-ICTs (e.g., virtual platforms) may help facilitate continuous interaction, learning and coordination in support of joint problem solving and co-creation of innovation (CitationKarpouzoglou et al., 2016; CitationMateria et al., 2015). Moreover, new networking possibilities may support alternative modes of coordination and performance in extension (CitationAmadu and McNamara, 2014) or farming communities. More specifically, Cieslik et al. (this issue) (CitationCieslik et al., 2017), have argued that new-ICT may enable the emergence of new forms of organisation in response to environmental challenges or other problems that require collective action. Bennett and Segerberg have introduced the term ‘connective action’ to refer to this new form of organisation that is informal and inclusive, and driven by personal motivations to engage with others in the pursuit of change (for instance the Arab Spring). It involves the “articulation of agendas and viewpoints, sharing and shifting of ‘memes’, information, images and propositions for action, enabled especially by social media such as Twitter and Facebook. Such media offer[ing] room for personal expression and connection […] through peer-to-peer mobilisation through one’s own network,” (Buytaert et al., 2014, p.9). Bennet and Segerberg describe ‘connective action’ as a more loose or self-organised form of organisation that contrasts with traditional forms or collective action in which formal organisational management and coordination play an important role (CitationCieslik et al., 2017; CitationBennett and Segerberg, 2012). It is interesting to explore whether and how such new forms of organisation affect coordination in innovation systems.

2.3 Mutual shaping of technology and society

It must be noted that the high expectations associated with new-ICTs reflect a (media) technology centred perspective in that it is assumed that technology and media capabilities determine the way new-ICTs are used in society (CitationLeeuwis, 1993). Such perspectives ignore the role of the social context in shaping technology use, including the significance of human abilities, preferences and motivations (CitationToyama, 2011; CitationMarchewka and Kostiwa, 2007), socio-political influences (e.g., actors with interests in maintaining the status quo) and the wider institutional environment (e.g., policies, incentive systems, funding arrangements, prevailing communication cultures, etc.) (CitationCieslik et al., 2017; CitationLeeuwis, 2013; CitationIpe, 2003). While such factors can indeed influence whether or not and how new-ICTs are used, the use of new media technologies is also likely to influence society in intended and unintended ways. In relation to this anticipated ‘mutual shaping’ it is naive to expect that new-ICT use will yield only positive and expected outcomes (CitationCieslik et al., 2017; CitationStilgoe et al., 2013). New forms of extension service delivery and innovation-intermediation may also foster new forms of exclusion or amplify existing inequalities, for example those related to illiteracy (CitationMateria et al., 2015; CitationToyama, 2011; CitationPerez et al., 2010). Similarly, technology use may take forms that deviate from the intentions of designers or implementing organisations (CitationStilgoe et al., 2013). In all, it is simplistic to assume that new-ICTs will resolve challenges in innovation systems (CitationLie and Servaes, 2015) on their own. Therefore, we look at the new-ICT revolution as a development that may potentially transform extension service delivery and broader forms of innovation-intermediation, but at the same time recognise that there may be social and institutional dynamics that deviate from this. Paying attention to the ways in which the use of (ICT) technology may shape and co-evolve with societal developments and vice versa (CitationWilliams and Edge, 1996; CitationScarbrough, 1992) is likely to provide a more realistic perspective on the contribution of new-ICTs to enhanced innovation-intermediation.

Against this conceptual background, this article investigates experiences with two new-ICT platforms in Ghana. In relation to these cases, we seek to answer the following research questions:

| 1) | What intermediary roles do public and private new-ICT platforms (aim to) support? | ||||

| 2) | What are the experiences of direct users with new-ICT supported innovation-intermediation? Are there indications that innovation-intermediation is enhanced? | ||||

| 3) | What is the role of decentralised information collection and new forms of connective action in the two cases? | ||||

| 4) | What is the interplay between (new) ICT supported innovation-intermediation and the broader extension and agricultural innovation systems landscape, including institutional set-ups? | ||||

3 Material and methods

The limitations associated with classical extension have also been reported in relation to Ghana’s pluralistic agricultural advisory system (CitationSigman, 2015; CitationDAES, 2011). Therefore, public and private providers are working towards operationalising more systemic extension mechanisms, including experimentation with innovation platforms and value chain approaches (CitationVan-Paassen et al., 2013; CitationDAES, 2011). The pluralistic extension system in Ghana in combination with the country’s growth as West Africa’s ICT hub (CitationMcNamara et al., 2014) presented opportunities for research on ICT-based innovation-intermediation.

We conducted a comparative case study analysis of two new-ICT platforms, E-extension and SmartEx, embedded in public and private extension organisations respectively. The approach served to facilitate analytical generalisation based on gaining contextual and qualitative insight (CitationYin, 2009) on the prospects and limitations of new-ICTs in facilitating broader innovation-intermediation roles. Hence, the platforms were selected on the basis of being introduced in organisations operationalising towards a more systemic extension approach. The organisations involved were the Wenchi District Food and Agricultural Department (DFAD) under the Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MOFA), and emerging out-grower businesses in Techiman District affiliated to the Achieving Impact at Scale through ICT-enabled Extension Services (AIS) Project led by Grameen Foundation (GF).

The research site was located in the Brong-Ahafo Region as it represented an area in which both E-extension and SmartEx were implemented. After consideration of five districts, Wenchi was chosen as the field research site based on the criterion of having a large farming community and that several Grameen agents were working in close proximity (i.e. within a 15 km radius) to the DFAD office, the base of Agricultural Extension Agents (AEAs). Additional criteria were that the mobile devices that accommodated platform use were still functional and had been in use for over a year, and that two operational agents per case were willing to participate. However, the research later extended into neighbouring Techiman District, as the two Grameen agents selected in Wenchi District exited the AIS Project. Whilst this presented a logistical challenge, this change did not compromise the basic research design which focused on the new-ICT platforms as the units of analysis’ and two organisations engaged in intermediation roles as the research context.

In order to understand new-ICTs’ (potential) role in supporting innovation-intermediation roles, we first reviewed the content and functionality of both platforms. Additionally, we conducted in-depth interviews with key informants from both organisations to determine: 1) innovation-intermediation roles they engaged in; and 2) mechanisms of facilitating these roles, including how the platforms were applied and intertwined with other methods and strategies of service delivery. In doing so, we simultaneously gained insight into the role division between the new-ICT platforms and conventional communication media (e.g., radio and field visits), and also with other new-ICT applications (e.g., WhatsApp). Data from these interviews were triangulated with that of in-depth interviews and observations of agents from both organisations to determine the roles fulfilled, and obtain user experiences, including challenges and opportunities for the platforms’ improvement. Farmers associated with these agents, were also interviewed to gain insight into how they accessed and appreciated agricultural advisory services. Additionally, experts of agricultural disciplines and ICT4D practitioners were interviewed to establish constraints and opportunities for (new) ICT in systemic extension service delivery. Data from farmers, experts of agricultural disciplines and ICT4D practitioners were collected to provide broader observations on intermediation and (new) ICT use in extension service delivery. Data were collected from the sample presented in below.

Table 2 Method and Sample.

Data analysis involved interview transcripts and field notes being uploaded onto Atlas.ti (qualitative analysis software) in which they were read and relevant text were coded. Thematic labels (major codes) that were applied to data collected from extension organisation staff included: ‘service provided’ and ‘service delivery method’, ‘platform use’ and ‘platform value’, and ‘challenges in service delivery’. Labels that were applied to data from all research subjects, including experts, were: ‘advantages’ and ‘limitations’ of (new) ICT use in extension service delivery. Labels that were applied to farmer data specifically were: ‘sources’ and ‘value’ of agricultural services. After coding, for each organisation, text with similar themes were exported into ‘primary document tables’ in excel, and then text with similar sub-codes under different themes were grouped manually. In order to describe the extent to which a sub-code was repeated, the number of times it occurred (enumerator) was divided by the number of respondents within a particular ‘category’ such as ‘agents’ (‘denominator’) and expressed as a factor of 10 to facilitate these descriptions: 7 of 10 and above – ‘most’; 4 to 6 of 10 – ‘almost half’; 1 to 3 of 10 – ‘few’; below 1 of 10 - ‘very few’. Further interrelations between themes were noted, and explanatory factors related to certain findings (as presented by respondents) were identified. These were linked to exemplary quotes that were pulled up from the transcripts and the primary researcher’s observations.

4 Results

4.1 Case 1: service delivery experiences with E-extension platform

The MOFA – Directorate of Agricultural Extension Services (DAES) works within a policy framework that supports service delivery transcending technology provision to respond to broader challenges in the agricultural innovation system (CitationMcNamara et al., 2014). As part of improving extension service delivery in these lines, MOFA launched the E-agriculture Programme in 2014. Under the programme AEAs across Ghana were trained to use the E-extension platform on smartphones.

According to the official job description of AEAs their primary objective is to advise farmers (and other agricultural value chain actors) and demonstrate appropriate technologies. Furthermore, their responsibilities include socio-economic and bio-physical profiling of operational areas, diagnosing and advising on solutions to farming problems – including problems related to farm management, inputs, credit and market access (CitationMOFA, 2001). In addition, they are required to conduct on-farmer-adaptive technology field trials and collect relevant data for researchers’ analysis. The next section describes E-extension’s functions in relation to the areas of service delivery outlined above.

4.1.1 Description of functions E-extension

The E-extension platform had three major functions (summarised in below). Firstly the collection of Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) location data, alongside crop-specific production data of farmers under a tab labelled ‘farmer’. Data collected through this tab was assumed to be useful for planning and intervention prioritisation. It also enabled the provision of unique randomly generated identification codes (ID) for farmers to facilitate the efficient management of the national input subsidy programme. The concept was that selected private input suppliers could run this ID through an online database to check if farmers had already received subsidised inputs for which they were eligible, therefore, preventing the double provision of subsidies to one farmer. Under the ‘farmer’ tab was another function of the platform, ‘field visit report’, which made provision for the digitisation of AEAs’ monitoring reports.

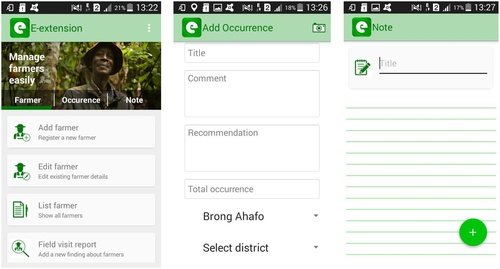

Fig. 1 E-extension farmer tab; E-extension occurrence capture; E-extension note capture (left to right).

Farmer tab: to facilitate farmar registration 1) add farmer: upload farmers' picture; document sex, family, size, mobile number, crop(s) produced,GNSS location and district name; 2) list farmer: to retrieve farmers' records; and 3) field visit report: digitise farmer monitoring.

Occurrence tab: to report pest or diseae occurrence 1) label occurence and location (GNSS and district name), upload picture, document preliminary diagnosis and recommended prescription and report the acreage affected; and 2) occurrence finding: to retrieve records of occurrences.

Note tab: to enable AEAs report any matter of the interest or concern.

The third function, ‘occurrence’, enabled MOFA head-quarters (HQ) to source timely information on the extent and location of events such as (new) pest infestations and drought occurrences. This was deemed useful for developing an early warning system to enable prompt and coordinated responses to emerging issues in the field. This and the other information collected through the platform was stored in a database with a dashboard. The dashboard was meant to enable HQ and DFAD management track agents’ activities and farmers’ situations.

In addition to the functions above, the smartphones served to connect AEAs to a website (http://www.e-agriculture.gov.gh), vis-a-vis a service providers repository with links to research and finance institutions, input suppliers and commodity buyers, farmer based organisations and transporters. The website aimed to reduce the time and mobility required by AEAs to vet and establish relationships with sector actors for the purposes of connecting relevant actors to each other.

4.1.2 User experiences

The platform’s general value was associated with the development of a farmer database and, therefore, its main use was considered farmer registration. Of all the staff affiliated to MOFA interviewed, most associated the platform’s value with this function through statements such as “We need to register farmers, because we lack farmer data in-country.” The DFAD staff (management and AEAs) not only recognised this value, but most also considered that HQ’s main motivation for developing the platform was to assign farmers unique IDs to prevent fraud in input subsidies provision.

However, despite the anticipation that E-extension would improve the process of subsidy provision, there were a number of challenges in achieving this. Firstly, all AEAs interviewed stated that limited funds to conduct field visits hampered data collection to populate the database. Secondly, almost half mentioned that they lacked internet bundles to send data to HQ, whilst a few DFAD staff stated AEAs lacked the capacity to use the platform to collect or send data. Additionally, the District Director pointed at technical hick-ups in the communication between local devices and the central database as a factor that hindered E-extension to improve input distribution. The overall success of using the farmer registration data to coordinate input subsidy provision in 2016 was limited, so that DFAD staff continued to use existing (desktop-based) farmer data available at the district office.

In relation to another use of the farmer data, almost half of the district staff interviewed expressed an interest in accessing such data to improve interventions planning. According to HQ this information was not availed, because the Wenchi District Local Government (financially responsible for the DFAD operations based on decentralisation policy) was unable to provide a laptop and internet facilities for DFAD staff to access the database.

With regard to the ‘occurrence’ function, it was established through interviews with AEAs that few occurrences and also monitoring reports were being sent to HQ. Few AEAs expressed that they occasionally sent data on occurrences through E-extension. One said, “Sometimes I use E-extension to send reports on peculiar things, for instance when armyworm broke out, but not to submit monitoring reports.” Another AEA suggested that receiving feedback on or prescriptions for problems reported on would motivate AEAs to use the function. Apart from the lack of feedback from HQ, the other factors contributing to the functions’ low usage included funding limitations, which also hampered crop monitoring and follow-ups on occurrence reports received by AEAs via mobile phones. The other contributing factor related to the district management’s concern that occurrences were reported directly to HQ before the extent of the infestation and actual pest was verified. The Director said this on reporting procedures: “[…] with E-extension we [DFAD] only register farmers,’’ and “[…] before we report a pest outbreak the threshold should have been passed, and if it has not, there is no need to raise alarm.”

In relation to the MOFA website, no AEA stated that they frequented it to access contact information of value chain actors and other stakeholders to match demand and supply for services and other opportunities. However, almost half stated that they accessed the internet over their mobile phones to retrieve agricultural information, suggesting that they were not unable to visit the MOFA site to retrieve information. In relation to not visiting the website one agent said, “I do not visit the website, the contacts on that site are not local. We make contacts on the ground, assess them and when we are satisfied, we link them to farmers”. This statement reflected that AEAs preferred to link farmers to contacts they had vetted and built relationships with at a local level. Another factor that could have contributed to the limited reference to and content on the website, such as the ‘agro-marketing’ tab being empty, was the service delivery focus of AEAs. No AEA expressed that their major duties included credit or market linkage and only a few said that they engaged in input linkages.

4.1.3 Broader observations regarding intermediation and (new) ICT use

Alongside E-extension, alternative service delivery facilitating mechanisms were identified for certain activities most DFAD staff stated they engaged in. These mechanisms related to stakeholder engagement, needs identification and information brokerage, joint problem diagnosis and solving, and production advice provision. These activities were facilitated face-to-face: specifically through engagement meetings with specific value chain actors (e.g., farmers or input suppliers) as the need arose, monthly review and brainstorming meetings for district staff, and group training or demonstrations respectively. Furthermore, in interviews with the DFAD Director it was established that the Wenchi DFAD had been the first and only office to pilot a cassava value chain innovation platform in Ghana from 2011 to 2017, and MOFA was recommending its wider adoption. The reasons put forward for expanding the platforms to other areas and value chains were explained by the Director: “Before we started the platform each actor would come to us with their problems and we would try to solve them individually. […] we know the problems producers face relate to other actors, so now we put all the actors on one platform […] to solve problems with each other directly.”

Apart from the face-to-face methods of facilitating service delivery, informal WhatsApp groups emerged from DFAD staff as another new-ICT application being used in the office. According to some respondents under the DFAD it was easy for non-tech-savvy staff to engage through the applications, specifically attach pictures. An internal WhatsApp group was used to share general and work-related information. The Director said, “The group was created to share ideas, alert others of diseases or pests noticed and to send information about pending meetings.” Whilst an agent commented that “the office group is informal and people share what they want, even jokes”. Additionally, individual staff were members of informal value chain based WhatsApp groups. Such groups served to maintain contact, and facilitate easy connectivity, sharing and discussion between value chain actors and support organisations after relationships were established through meetings.

Plantwise was observed as another new-ICT platform that AEAs used. Two AEAs under the DFAD used it as part of a nationwide project led by CABI (a research institution). The projects aim was to reduce crop losses by establishing plant clinics for farmers to access plant health advice. The clinics involved farmers bringing plant samples for “plant doctors” (AEAs) in their locality to diagnose. To support the clinics, the AEAs used three Plantwise functions on a tablet. The ‘Plantwise Factsheet’ containing pest and disease management advice and a Telegram (instant messaging) group of 192 AEAs across Ghana, agronomists and researchers. Furthermore, AEAs also recorded, through a digitised “prescription form” (‘Plantwise Data Collector’), farmers’ biodata and plant health problem diagnosis’ and prescriptions. AEAs were motivated to use the ‘Plantwise Factsheet’ as it connected them to current technical information, one AEA said, “Plantwise is current, this morning they sent us information on the armyworm's life cycle. The information we need now to advise farmers on when [the stage] treatment is effective.” According to AEAs, the factsheet was also useful as it facilitated learning: “Sometimes you hear of a disease you have no idea of and through fact sheet you come across it and learn about it, and then you can teach farmers about it.” The Telegram group was also valued for facilitating learning, an AEA said, “At the beginning of the season many of us were mistaking armyworm for stembora. The specialists were following our discussions on Telegram and then posted something on differentiating between the two.” Additionally, Telegram was found useful by AEAs for providing current sectoral news, for examples: “The latest chemicals […] banned chemicals […] current happenings […] like the other crops armyworm is attacking.” The factors mentioned above that motivated AEAs to use Plantwise, directly related to areas of improvement they suggested for E-extension.

In relation to production advice provision, a major focus of service delivery mentioned by all DFAD staff, all DFAD staff and farmers cited group training and demonstrations as the main teaching methods applied. Additionally, most AEAs expressed that they both received farmers’ reports on challenges (e.g., pest infestations) and responded to these challenges over the phone. AEAs probably used mobile phones in this manner due to a lack of operational funds, in relation to this an AEA said, “Those farmers that call me I give them advice over the phone, for some farmers I sacrifice and go and see them.”

Alongside mobile phones, most AEAs also mentioned radio as a method of production advice provision. AEAs were required to participate in radio programmes on local radio stations as part of their official duties under the DFAD office. However, according to Farm Radio staff, despite farmers appreciating radio as a source of production advice they considered it limited in facilitating learning-by-seeing that was critical in building their confidence to engage in practices.

Aside from using radio in service delivery, few AEAs reported that they used a separate GNSS application from that on E-extension, for measuring field sizes. Such geo-data were used to prevent or resolve conflicts over field measurements between farmers and ploughing service providers. These conflicts often arose from farmers using imprecise measures for field size and providing these measurements to plough operators to quote a price pre-works. At times this resulted in disputes over field size and price when operators came on site. The use of the GNSS application typically involved AEAs walking around the perimeter of a field and pinning its coordinates with the application, and then giving a precise and acceptable field size estimate to both parties.

Lastly, it was also observed that farmers’ use of available weather SMS push services was limited due to literacy and the timeliness of these services. One farmer said, “Most farmers are illiterate, so if you want to go about such things [providing SMS weather data] it becomes difficult for them.” Additionally, another farmer commented that although the weather information sent via SMS was more accurate, the conventional radio forecasts were more timely. This was because at times the SMS data only reached farmers in the afternoon, which was too late for them to decide whether to go into the field or not considering they preferred to go into the field in the morning.

4.2 Case 2: service delivery experiences with SmartEx platform

Grameen Foundation is an international development organisation rooted in business-oriented approaches to poverty reduction. Between 2014 and 2017 Grameen in Ghana partnered with ACDI/VOCA, another development organisation, to build the capacity of maize traders to evolve into out-grower business owners and enhance systemic extension service delivery. The partnership aimed to apply new-ICTs in improving traders’ management of farmers (suppliers), and their control over crop supply and quality through better monitoring, and technical and credit support coordination.

For the project, traders identified tech-savvy individuals for Grameen and ACDI/VOCA to train as agents. These individuals were trained on basic agronomic principles and SmartEX. Once trained the individuals (agents), using SmartEx via tablets, were required to identify farmers’ needs, conduct demonstrations and train farmers on improved technologies, and develop seasonal farm management plans with farmers to facilitate crop monitoring. They were also required to liaise and negotiate with service providers to meet farmers' needs, the emphasis being on improving farmers’ access to inputs. During the marketing period, they were required to purchase produce for traders and simultaneously receive payments (as produce) for input loans and other services (such as ploughing) they organised for farmers, and coordinate produce sales to end-market buyers. SmartEx was designed to support the agents in coordinating service delivery as described above.

4.2.1 Description of functions SmartEx

One of the AIS project assumptions was that agents required less agronomic training and networking skills than classical extension agents to engage in service delivery. This assumption was based on AIS project agents having easier access to information through SmartEx. SmartEx’s homepage consisted of six tabs labelled ‘Farmers’, ‘Meetings’, ‘Suppliers’, ‘Markets’, ‘Technical Assistance’ and ‘Farmer Search’ (summarised in below). The first two tabs facilitated data collection. The ‘Farmers’ tab enabled the collection of farmer biodata and other data to automatically profile farmers, including the collection of baseline data on farmers’ production practices and credit activities. Under this tab, agents could also create farm management plans and digitised weekly reports, including the reporting of emerging field issues (e.g., pest infestations). Similarly, the ‘Meetings’ tab allowed for the creation of digital reports of group training and farm(er) monitoring visits. In summary, the first two tabs aimed to facilitate farmer enrolment and needs assessment to support farm monitoring and agents’ timely response to emerging field issues. An important rationale underlying the collection of this information was also that it would be used by traders and/or other input providers to assess which farmers could be provided credit (in the form of inputs) with minimal risk, and help convince their designated financial organisations to provide them with sufficient working capital to operate.

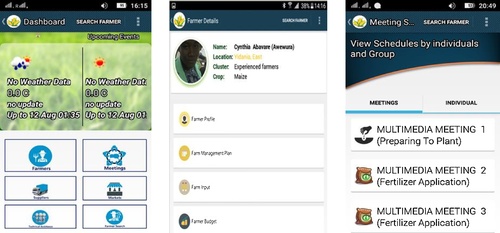

Fig. 2 (Left to right) SmartEx homepage; SmartEx farmer records summary; SmartEx meetings data capture.

Farmer tab: function to 1) facilitate the collection of farmer registration data and farmer profiling (as experienced; moderately experienced; farmers on the rise; and moving from subsistence); 2) collect baseline date on farmers production practices by crop and farming enterprise credit activities, and update it seasonally; 3) to document and update seasonal farm management and credit plans; and 4) to digitise agents weekly plans and weekly reports.

Meetings tab: function to record out comes of 1) farmer group meetings by crop at pre-planting, first and second fertiliser application, and harvest or post-harvest; and 2) individual farmer visits planned according to the production activities to facilitate registration, farm planning, fleid measurement, crop assesments and fertiliser application.

Suppliers tab: contact details of a range of agricultural input suppliers, financial instructions, tractor service provided and transpoters arranged by region.

Market tab: contacts details of agro-processors, aggregators and traders by region.

Technical Assistance tab: repository of various crop mangement guides, and videos on production, pest and disease control, processing and marketing.

Farmer Search tab: search function to enable agents retrieve farmer records by crops, community (location), profile or name.

The second two tabs ‘Suppliers’ and ‘Markets’ were meant to facilitate easy access to service providers contacts (with whom Grameen had established collaborative relationships), enabling agents to link farmers to services and facilitate value chain linkages. The SmartEx database, under the ‘Technical Assistance’ tab, stored a variety of crop management guides on good agricultural practices (GAPs) and teaching videos, for agents to easily access information relevant for advising farmers. The ‘farmer search’ tab was designed to give agents access to analysed monitoring data, to quickly understand a farmer’s background, establish their needs and track their performance.

Alongside the above functions the tablets were internet-enabled to support wider access to agricultural information and weather services for agents. -subsequently farmers, and SmartEx also had a dashboard meant for traders and Grameen Staff that could track agents’ field activities in real-time. The next section provides insight on agents’ actual use of the SmartEx platform.

4.2.2 User experiences

In relation to farmer registration and profiling through the ‘Farmer’ tab, most agents engaged in this activity and considered this SmartEx’s main function. All traders saw this as the major role of agents in their businesses, as one trader stated, “The work of agents is to use the tablets to monitor farmers’ activities, keep records on farmers and profile them.” Despite all the traders interviewed recognising the value of the data collected under the ‘Meeting’ tab in tracking and monitoring farmers’ progress, few agents collected these data or engaged in monitoring consistently. Similarly, few agents sent weekly reports through SmartEx, hence emerging issues on the ground were not actively reported to Grameen. Additionally, few agents used the platform to develop farmer management plans. Most respondents associated with Grameen stated limited transportation (funds) as a constraint to visiting the field for data collection. Furthermore, agents indicated they had no contractual obligations to traders and were not remunerated by them, which contributed to their de-motivation to collect data. It was observed, during the research period (5 months), that 3 agents (out of 15) dropped out of the project citing remuneration as a contributing factor. Meanwhile, despite these challenges, from the perspective of Grameen staff the project could be seen as working towards testing new business models for agricultural services provided by traders, where it was expected that SmartEx and agents’ use would eventually lead to risk reduction for traders and other input providers, and thus improve their financial position, enabling them to remunerate agents for their services.

While the ‘Suppliers’ and ‘Markets’ tabs meant to facilitate easy access to service providers contacts for agents to engage in value chain linkages, few agents used the platform to identify input dealers and financial institutions to improve farmers’ access to inputs, and it was observed that market actors repository was empty. A probable explanation for the empty repository was that traders had already established linkages with farmers and end-buyers prior to the project. Whilst the general limited use of the function could be related to the role defined for agents in traders’ businesses. As already mentioned most agents and traders identified agents’ role as a data collector and record keeper. In this situation traders, who had limited access to SmartEx and mainly engaged agents on the criterion of tech-savviness, continued to rely on their personal networks to provide loans to farmers. These networks included both organisations from which traders had accessed loans over the years, and those they had engaged with through ACDI/VOCA more recently. Developing these personal networks with financiers involved a series of meetings in which traders vouched for farmers or convinced financiers of their capacity to be guarantors for farmer loans. However, one trader said he sometimes used farmer records from SmartEx to negotiate farmer credit arrangements with financial institutions, but in general the use of farmer records and plans for these purposes was not widespread.

With regard to production advice provision, despite almost half of the agents expressing involvement in this, only a few stated that they referred to the SmartEx crop management guides. Interviews suggest that traders and not agents as assumed by the project had closer contact with farmers on issues of production and other advice. In relation to this almost half of the agents alluded to farmers with challenges often calling traders for advice, and this seemingly limited agents’ incentives to refer to the training material.

4.2.3 Broader observations regarding intermediation and (new) ICT use

It was observed that traders, in collaboration with ACDI/VOCA, also linked farmers to other new-ICT platforms providing production advice, specifically ESOKO a direct-to-farmer SMS agricultural information service. Of the few farmers interviewed using ESOKO, few alluded to actively accessing production advice from ESOKO. Those that did said that they received valuable timely weather-based guidance on when to engage in farming activities (e.g., fertiliser application), but stated that interaction with an expert was still required for them to grasp the advice. In relation to this, most farmers considered AEAs their main production advice provider. The following statement reflected farmers’ views on the comparative advantages of sourcing production advice from ESOKO and experts (AEAs): “ESOKO only sends us information, whilst the “agric people” [AEAs] come directly to the field to assist us when we are not clear. Then again, the goodness of the ESOKO information is that it is readily available unlike agents that are not always able to come into the field.”

Further, very few farmers accessed SMS market information through ESOKO or radio. Farmers appreciated having access to commodity prices in wider markets. However, access to this information did not translate into improving their negotiation position with traders, whom they were often tied to by supply and credit agreements. It rather enabled them to ascertain whether their designated trader was offering a fair price. However, interviews with traders suggested that ESOKO’s market information service was more valuable to them in scanning markets, price setting and negotiations, as they had higher mobility than farmers and access to larger volumes of produce. Most traders interviewed valued the SMS service in this manner. Furthermore, they were wary of farmers being privy to price information, an agent said, “It [ESOKO] helps me know commodity prices at different markets. So I know the best prices to sell my produce at a profit,” and he continued, “It is even spoiling our [agents’] negotiations with farmers. Now farmers know the prices and want to sell their produce at the ESOKO price.”

Additionally, very few farmers interviewed accessed ESOKO weather data, the majority accessed forecasts via radio. One of the few farmers accessing the SMS based weather data valued the service in this manner: “Getting the information from the phone is good, as it is always with me and the information they give is correct more times than the one on the radio.” He further alluded to illiteracy being the major factor deterring other farmers from engaging with the SMS service. In addition an ICT4D practitioner indicated that illiteracy was also a barrier for farmers to access other types of agricultural information, stating “Any information that is channeled via phone and involves readable text excludes farmers. There is more promise in using voice recording, radio and actual interaction to engage farmers.”

Grameen also established a WhatsApp group for agents to report technical challenges of operating SmartEx to Grameen staff. One agent revealed that the group was also being used to report on other field challenges, including pest infestations, and explained why through this statement: “All the Grameen managers, facilitators and agents are on the group […], and they help find solutions. […]I found when I reported problems through WhatsApp I got a more immediate response than when I reported through SmartEx [weekly reporting].’’ The WhatsApp group also enabled the sharing of ideas and experiences with more immediacy than the quarterly review and sharing meetings that ACDI/VOCA organised for agents and traders to discuss progress and field experiences.

5 Analysis and discussion

This section analyses the results in relation to the research questions posed about the role of new-ICTs in supporting innovation-intermediation. Subsequently, we discuss the implications of these findings for the further development of new-ICT platforms and future research.

5.1 Intermediary roles supported by new-ICT platforms and user experiences

In terms of the intermediary role supported by E-extension and SmartEx, we see some similarities and differences (see , below for an overview).

Table 3 Comparative Summary of Intermediation Roles that E-extension and SmartEx aim to support.

Both platforms were embedded in organisations with the intention of achieving more systematic forms of extension service delivery, and therefore attention for the platforms to support a variety of innovation-intermediation roles was observed. A common feature of both platforms is that there was emphasis on database development and the collection of farmer registration data (names, locations, farm size, crops grown, and in the case of SmartEx also farm development plans etc.) as a basis for enhancing service delivery and innovation-intermediation.

Furthermore, both platforms included a service providers repository to facilitate value chain linkages, and enabled the digitising of agents’ monitoring activities to track agents and identify emerging issues on the ground with immediacy. Below, we analyse in more detail how these features link to other platform characteristics and the three types of innovation-intermediation distinguished in and : demand-articulation, matching demand and supply, and innovation process management.

Demand-articulation - For both platforms, farmer registration and database development were meant to support demand-articulation, but for different purposes and with different levels of interaction and detail. In the case of E-extension, registration and database development involved the collection of basic farmer information (location, crops grown, farm size) and reporting on emerging issues (e.g., pests and diseases). This information served in part to rationalise and control the delivery of input-subsidies, but also inform extension organisations of farmers’ knowledge demands. However, the degree of interaction between ‘supply and demand’ in E-extension was limited, and thus the registration data was not oriented towards the in-depth articulation of specific demands, but rather to general categories that were helpful for planning and prioritising extension activities and targeting production advice provision to groups (e.g., maize growers). In practice, however, potential advantages of this modality for demand-articulation were not realised, as implementation was complicated by a range of technical, resource and capacity constraints, resulting in few farmers being registered through this system. Therefore, AEAs continued to rely on pre-existing farmer registration data for planning, and on conventional demand-articulation modes during field visits, group meetings and –more recently- face-to-face innovation platforms and mobile phone conversations.

For SmartEx the interaction was designed to be more intensive and detailed, and mostly oriented towards the articulation of individual demands for services (input provision, ploughing, processing, transport, etc.), tied to credit provision (in kind) by traders. To this end farmers registration through SmartEx automatically facilitated farmer profiling, placing them into categories (experienced, moderately experienced, farmers on the rise, and moving from subsistence) that described their farming level, capacity and priorities for service delivery. SmartEx further supported the collection of baseline data on farmers’ production practices and credit activities, alongside seasonal farm management plans to aid agents in the identification of farmers’ financial, equipment and input requirements based on their intended farming practices and area of cultivation. In all, demand-articulation in SmartEx was meant to be more intensive, continuous and individual than in E-extension, and less oriented to articulating knowledge demands. However, in the case of SmartEx, we also see that this potential was not realised. Insufficient incentives existed for agents to actively engage in the articulation of individual demands for services, still pointing to resource constraints and additionally unconducive remuneration relations between traders and the newly established agents. In the situation, traders mainly relied on pre-existing information and relationships rather than on information collected through SmartEx.

While both platforms paid attention to articulation of farmer demands, it is interesting that the needs and demands of service providers themselves played a prominent role in how the platforms operationalised demand-articulation. The effective and efficient working of MOFA and its extension services was the centre of attention for E-extension, while the needs of traders and other credit providers played an important role on SmartEx. At a more abstract level, SmartEx served to test a new business model for commercial service delivery, as envisaged by Grameen, based on the notion that the collection of information about farmers could reduce risks in lending for credit providers, as they would be in a better position to judge farmers’ trustworthiness. At the same time, provision of credit (in kind) would allow farmers to access a range of services. It was assumed that addressing demands of extension organisations, traders and credit providers would indirectly serve the interests and needs of farmers. Considering it is inherent to innovation systems that demands and interests of different stakeholders play a role in service delivery, this assumption is a reminder that it is important to contemplate about how a good balance between different demands driving the design of new-ICT platforms may be negotiated (CitationAlexiou and Zamenopoulos, 2008),

Matching demand and supply – Both platforms included modalities to facilitate the matching of demand with appropriate services. To support matching, both platforms provided contact details of types of service providers. However, in both cases this information appeared to be of limited use. In E-extension local contacts were largely absent in the system, and AEAs preferred to connect farmers to their own local and personally vetted contacts. In the case of SmartEx more local contacts were provided, but the results also indicate that existing ties and personal networks dominated matchmaking. Additionally, the SmartEx platform included the introduction of a new professional – the tech-savvy agent - whose tasks included facilitating commercial matchmaking. Although potentially useful from the Grameen perspective, the remuneration of this new professional remained problematic.

SmartEx also included general reference materials on GAPs (in text and pictures) for agents to use in response to farmer profiles and queries. This information had a generic nature and would have to be tailored to farmers’ needs by agents. For SmartEx the potential for tailored production advice provision was greater than in E-extension due to the more refined demand-articulation process, but agents did not intensively use these opportunities as production advice provision received relatively little attention in practice. As observed, the agents selected had limited agricultural know-how, and their role was mainly defined as data collectors and record keepers as opposed to production advice providers. In addition, there were problems with internet connectivity in the field, the pace at which the repository was updated was slow, and traders fostered linkages to DFAD or NGOs who offered similar information through conventional media. Overall, there was no indication that agents used the repository frequently.

Innovation Process Management – Both platforms aimed to foster new forms of coordination among stakeholders. E-extension aimed to enhance coordination especially with providers of subsidised inputs through the farm registration system, and SmartEx was geared towards introducing new coordination arrangements among a range of service providers, with agents and traders as linking pins. We already indicated that both coordination mechanisms faced problems in implementation.

Both platforms also offered learning opportunities in broader networks in the form of monitoring systems through which AEAs or agents could solicit feedback from others on specific problems or emerging issues (e.g., pest occurrences). However, in both cases these monitoring systems were not intensively used as AEAs and agents experienced that responses were slow or not forthcoming. Perhaps more importantly, we observe that they found more suitable new-ICT applications for networking, relationship maintenance and joint learning in the form of informal WhatsApp groups and the Plantwise Telegram group. These discussion platforms were easier to use, did connect expertise and experience from a diverse membership (e.g., AEAs, researchers, experts, managers, service providers), and frequently yielded immediate responses.

Neither E-extension nor Smart-Ex had functions geared towards conflict resolution. However, we observe that some AEAs effectively used geo-data and GNSS applications to assist in settling and preventing disputes between ploughing service providers and farmers over field measurements.

Finally, it must be noted that – even though both platforms paid attention to enhancing coordination and organisational feedback - it cannot be said that the two new-ICT platforms were geared deliberately towards facilitation of multi-stakeholder interactions towards socio-technical innovation to replace e.g., face-to-face innovation platforms or complement virtual knowledge sharing platforms as was the case in the study of Material et al. in the Italian agricultural knowledge system. Thus, in this case, innovation process management remains much more piecemeal and ad-hoc than might be feasible based on the organisational goals for the platforms.

5.2 The role of decentralised information collection and connective action

Both platforms intended to make extensive use of decentralised information collection about farmers and their farms, and to a lesser extent about (extension) agent performance. However, the purposes and features of this data collection diverged from the idea of using environmental monitoring and citizen science in support of collective problem solving and innovation (see Cieslik et al., this issue). In contrast to this, data collection was not connected to any scientific ambition, did not involve farmers (or others) sending in their own contextual information (as in many citizen science projects), and was neither accompanied by a facilitated process of exchange and social learning to address collective problems (e.g., combating emerging plant diseases). Instead, it involved data collection by professionals and modes of one-way communication that were intended mainly for fostering new forms of coordination (as described above) and the enhancement of organisational efficiency and effectiveness in delivering services. In relation to this, decentralised information collection focused mainly on characteristics and practices of humans (farmers and agents), with only limited attention to monitoring the kinds of agro-ecological processes implied by the notion of ‘environmental monitoring’ (Cieslik et al., this issue).

As explained, the enhanced forms of organisation and coordination strived for had yet to materialise. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note in the context of this special issue (see Cieslik et al, this issue) that both projects did seek to capitalise on improved new-ICT connectivity and use decentralised information collection and monitoring in an effort to change (inter)organisational patterns. This was also true for the Plantwise Telegram group, and the various informal WhatsApp groups that emerged around both the Government extension service and Grameen project. In these groups, enhanced connectivity did involve the sharing of personalised information (experiences, ideas, viewpoints, images, etc.) through enhancing interaction of multiple actors virtually in an effort to achieve collective organisational purposes, more specifically related to managing issues of uncertainty such as the new threat of the armyworm pest. Thus, there are indications of new forms of organisation emerging that resemble what Bennet and Segerberg have labelled as ‘organisationally enabled connective action’ (see also Cieslik et al., this issue), as the WhatsApp and Telegram platforms were organisationally embedded and supported, but still facilitated sharing of personal action frames, information and knowledge with limited organisational moderation. Our interviews and observations suggest that these relatively simple applications (running on standard smartphone and software packages such as WhatsApp) where among the new-ICTs that (extension) agents were more inclined to use.

5.3 The interplay of new-ICT use with the agricultural innovation system

We observed that new-ICT supported innovation-intermediation was affected by various processes and conditions in the broader social and institutional context.

Clearly, poor literacy and smartphone penetration among farmers (as associated with poverty) shaped the way in which E-extension and SmartEx were designed, namely with AEAs and agents (rather than farmers) targeted as direct users. As we observe, the uptake of direct-to-farmer SMS services too was widely affected by poor literacy.

Moreover, a number of institutional conditions constrained the use of both platforms. We observe that resource constraints in both the public and private setting affected AEAs’ and agents’ use of the platforms. We also find – especially in the case of E-extension that supportive organisational arrangements and capacities for technical problem solving, responding to monitoring reports and ensuring regular renewal and updating of information were lacking. Thus, the available new technology and envisioned use were not complemented with appropriate organisational innovations (e.g., novel organisational arrangements and incentive systems) (CitationLeeuwis, 2013).

Additionally, we observe in SmartEx’s case that pre-existing networks and institutional arrangements around trade and credit provision were strong. Existing dependencies between traders and farmers made it difficult for the latter to capitalise on improved market information, except to ascertain that their designated trader offered fair prices. Moreover, it was not easy for the newly introduced agents to establish and position themselves and be valued (also financially) by traders, which raises concern for the sustainability of Grameen’s intended business model for service delivery.

In relation to sustainability, it is also relevant to note that new-ICT projects in Ghana tend to be donor-funded, with more support garnered to platforms with commercialisation plans. Both E-extension and SmartEx were donor-funded, as was Plantwise. Coordination between the projects was not self-evident, which is reflected in the fact that there was duplication in the three platforms’ functions (e.g., farmer registration systems, databases of service providers and technical repositories). The prevailing innovation system landscape enabled these parallel initiatives. It is common knowledge that the often temporary nature of donor funding may influence the attitude with which stakeholders engage with initiatives, whereby a certain degree of opportunism may undermine the possibility of interventions becoming sustainable (CitationLambrecht and Ragasa, 2016; CitationMoyo, 2009). To be clear, there was no compelling evidence that this is the case for E-extension or SmartEx. However, the fact that sustainability is a relevant concern for such platforms is evidenced by a World Bank review of 92 ICT4Ag applications in developing countries, which demonstrated that only 20 percent of commercial and 11 percent of non-commercial applications reach the sustainability stage of business development (CitationQiang et al., 2012).

5.4 Discussion: implications for further design, development and research

In this discussion section we first present a comparative summary of platform functions and user experiences in the form of a table (see ). In this table we summarise and associate the main findings for both platforms to the appropriate innovation-intermediaries roles. This table then serves as a basis for discussing three themes that merit further reflection, action and research in connection with the future design of new-ICT platforms for agricultural extension. We have grouped these themes in three categories: 1) the need to embed new-ICT in prevailing media landscapes, 2) fostering coordination and arrangements for sustainability, and 3) enhancing user orientation and understanding of user initiatives.

Table 4 Comparative Summary of Platform Functions and User Experiences.

Embedding new-ICT platforms in prevailing media landscapes – The summary presented in suggests that both E-extension and SmartEx face numerous problems in facilitating innovation-intermediation roles. Thus, there is a big gap between the expectation that ICT-supported interaction, exchange, networking and monitoring would enhance the innovation system performance, and the reality on the ground in the Brong-Ahafo Region. Arguably, we see an opposite influence whereby dominant features of the existing innovation system make it difficult to capitalise upon the potential of new-ICT platforms. Nevertheless, there are indications that standard social media platforms such as WhatsApp and Telegram are utilised to enhance particularly innovation process management. These platforms that are more geared towards multi-actor engagement are used in, for example, organising effective responses to pests and diseases. However, further research is needed to analyse such dynamics, and assess whether this indeed involves (organisationally enabled) connective action (see Cieslik et al., this issue).

Our findings also imply that conventional media still play an important role in a variety of innovation-intermediation processes, and that they have qualities that continue to provide added value in the current context. This is in line with, for instance, CitationDuncombe’s assertion that face-to-face interaction remains critical for both demand-articulation and the matching of such demands with an appropriate supply, in view of the importance of local ties and the dynamics of trust building. Further, similar conclusions about the continued importance of interpersonal methods and conventional mass media in contexts of ICT-based service delivery, are arrived at by other authors (CitationHansen et al., 2014; CitationHeeks, 2008; CitationChapman and Slaymaker, 2002). These conclusions include that classical extension agents remain relevant in production advice tailoring based on their familiarity with farmers and farmers’ areas of operation, and also farmers’ preference for face-to-face interaction in learning (CitationCTA, 2016). In all, we see that efforts to (re)design new-ICT platforms for innovation-intermediation should take into account that such platforms cannot be looked at in isolation. In relation to this CitationMateria et al. (2015) and CitationSulaiman et al. assert that (new) ICT interactions support, complement or spur real-life interactions to facilitate innovation processes. Therefore, designers should think carefully about the whether or not (new) ICT options are likely to provide added value vis-a-vis existing communication patterns, and explore what combination of media may – in a given context - be helpful in providing specific services.

Coordination and arrangements for sustainability – A point of contemplation is whether the existence of several new-ICT platforms with areas of duplication, overlap and under-utilised complementarities is a problem, or to be regarded as an inherent feature of pluralistic extension systems. From an evolutionary innovation perspective, one could argue that it is beneficial to have multiple initiatives, because competition helps initiatives to improve quickly, and ensure that ‘the best’ initiative survives (CitationGeels, 2011). However, it is questionable whether this model of thinking applies fully to such a resource constrained environment. From an innovation systems perspective, one would also say that there is considerable scope for enhancing complementarity and coherence, and that there is promise in fostering relationships of resource sharing between public and private extension organisation and potentially research institutions. This could help to meet (content and technical) development and maintenance costs of the platforms, and take advantage of the strengths of public organisations (e.g., collective demand-articulation, production advice provision, registration) and private parties (e.g., credit provision, value chain linkages). Such collaboration may also make it easier to develop a sustainable public-private model for service delivery, in which conducive organisational arrangements for operations, technical support and substantive maintenance are connected to financial flows. Such considerations are already prominent in the Grameen project, but clearly the envisaged model is not yet working optimally. Therefore, action and research might be oriented towards increasing our understanding of the conditions under which traders, credit providers or farmers might be willing to remunerate agents for ICT-enhanced data collection. Alternatively, it may explore and design altogether different models that stakeholders find promising.

Enhancing user-orientation and understanding of user initiatives – User experiences reported in this article suggest that many components of E-extension and SmartEx are not yet functioning as intended by the designers. To improve the usability of these systems, there is certainly scope for soliciting additional feedback, and incorporating this in the re-design of components of the platforms. Incorporating user feedback into design is suggested as broader experience with (new) ICT system development shows that structural involvement of users in the design process can help to discover and accommodate appropriate information and communication needs (CitationStilgoe et al., 2013; CitationStewart and Hyysalo, 2008). At the same time, building on existing initiatives as opposed to ‘starting from scratch’ can also enhance the usability of (new) ICT systems (Hanson et al., 2014; CitationHeeks, 2009; CitationChapman and Slaymaker, 2002). Therefore, instead of studying how service providers use externally introduced new-ICT platforms, it may be especially informative to analyse (new) ICT initiatives that service providers themselves take to support their work. In this case we have observed that there are self-organised WhatsApp groups transforming interaction patterns in innovation systems, and that mobile phones are used widely in the interaction between farmers and service providers. A content and/or network analysis of interactions taking place through WhatsApp groups or mobile phones may, for example, reveal in more detail what kinds of needs service providers and their clients have. At the same time, it can offer insight into new forms of organisation and collective action that are feasible and useful in innovation systems. In relation to this, it is important to note that farmers are not yet widely connected to (or through) such virtual platforms, even though they are a source of relevant information. Thus, it is interesting to explore ways of enabling farmers to connect and share with other agricultural actors, considering that extension (agents) have limited mobility to provide services or collect information that serves farmers’ interests.

6 Conclusions

There are high expectations regarding the role that new-ICT platforms may play in enhancing the performance of agricultural extension and other forms of innovation-intermediation in the face of complex challenges. In line with the idea of ‘Environmental Virtual Observatories for Connective Action’ (EVOCA, see Cieslik et al., this issue), new-ICT supported decentralised information collection and monitoring as well as connectivity-based modes of organising were expected to play a significant role in this. The study shows that both public and private sector parties use new-ICT platforms to augment extension service delivery and facilitate broader forms of innovation-intermediation. While both platforms aim to support demand-articulation, matching demand and supply, and innovation process management, the level of detail and underlying organisational purposes differ markedly. The public platform appears mainly oriented towards enhancing organisational efficiency in production advice provision, and the private platform is geared towards testing a new business model for delivery of a range of commercial services. However, our exploration of user experiences suggests that both platforms face serious constraints, and that new-ICTs’ potential to support innovation-intermediation is far from realised. This is not because new-ICTs have no capacity to link people in new ways and make information accessible, but due to the wider social, organisational and institutional factors that define the realisation of new-ICTs’ potential. These include resource constraints and absence of supportive organisational arrangements that allow new-ICT platforms to operate smoothly. Another important institutional constraint is that newly introduced business models have not successfully complemented or competed with pre-existing networks and arrangements around trade and credit provision. In light of all this, more conventional modes of interaction around production advice provision and communication remain dominant and better adapted to the situation.