?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Highlights

| • | Identification and assessment of farm success in urbanized areas. | ||||

| • | Web survey among farm managers in the Ruhr Metropolis (Germany). | ||||

| • | Farms applying various adjustment strategies are more successful. | ||||

| • | Tourism services and direct marketing are most successful. | ||||

| • | Farm location is the key determinant for promising city-adjustments strategies. | ||||

Abstract

Economic viability of urban and peri-urban agriculture (UPA) is the key requirement for additional social, environmental, and landscape functions within urban and peri-urban areas. However the rapid progress of urbanization drives the loss of farmlands to industrial, residential and other urban uses, and the decline of farms and population working in agriculture. Hence, the literature highlights the need to popularize new ideas and strategies of preserving and developing farms in urbanized areas.The main aim of this research is both to identify and assess determinants of success of farms located in urban and peri-urban areas. The key question that has arisen is: how do different adjustment strategies, locations and farm resources affect the success of farms? For this purpose a web survey was conducted among 199 professional urban and peri-urban farms in the Ruhr Metropolis (Germany). It is an old-industrialized polycentric urban agglomeration where agriculture has a comparably high level of significance in current land use. Analyses were conducted taking a resource-based view and using the classification tree method. The data indicate that farms which use various adjustment strategies are more successful. Elements of successful strategies, are include tourism services (mainly horse-riding) and direct marketing. Results further indicate that the effectiveness of those strategies (farm success) is mainly dependent upon a farms locations. Distance from the customer seem to be of utmost importance, because by minimizing transport costs, customers choose entities that have the most convenient location for them. By assessing farm success from a long-term perspective, it was noted that positive prospects of development apply mainly to full-time farmers who use appropriate adjustment strategies. In contrast, farms, which do not use any elements of strategies relating to customers from urban areas, seem to achieve success chiefly from having a relatively large surface area of farmland.

1 Introduction

The concept of urban and peri-urban agriculture (UPA) is not new as is sometimes claimed (CitationVickery, 2014). In fact, the history of UA is as long as that of cities (CitationVickery, 2014; CitationBrinkley, 2012). Nowadays, crops and livestock are produced in urban and peri-urban areas all over the world (CitationBrinkley, 2012; CitationMougeot, 2006; CitationPölling, 2016). In the literature, the practice of urban farming is associated more with developing countries (CitationLovell, 2010; CitationMougeot, 2000; CitationVan Veenhuizen and Danso, 2007). Nevertheless, since the 1970s, UPA has also received more attention in many cities of the Global North, including the USA, Canada, Australia, Japan, Germany, Great Britain and the Netherlands (CitationMok et al., 2014; CitationZasada, 2011; CitationHol et al., 2014; CitationHuang and Drescher, 2015; CitationAngus et al., 2009). In these countries, UPA is often depicted as a solution to the global challenges posed by urban population growth, environmental degradation and climate change (CitationSpecht et al., 2016). UPA and especially the development of multifunctional farms have become an inherent part of the sustainable development of cities (CitationZasada, 2011; CitationMougeot, 2006; CitationSmit and Nasr, 1992). Hence, scientists, planners and city managers show great interest in the maintenance and reintroduction of multifunctional farms in urban and peri-urban areas (CitationSpecht et al., 2016; CitationLovell, 2010; CitationZasada, 2011; CitationPölling et al., 2016). On the other hand, the rapid progress of urbanization has been reported to drive the continuous loss of farmlands to industrial and residential uses, and the decline of farms and population working in agriculture (CitationWästfelt and Zhang, 2016; CitationHennig et al., 2015; CitationAubry et al., 2012). Moreover, the description of UPA as an entrepreneurial activity applied in and around cities of the Global North has largely been neglected, especially in Europe (CitationSpecht et al., 2016). In 2007, the FAO stressed a ‘lack of sufficient [economic] data’ and emphasized ‘the limited number of studies with sound economic analysis’ of UA (CitationVan Veenhuizen and Danso, 2007). In recent years, research has been conducted i.a. on shortening food supply chains (CitationAubry et al., 2013) and farm adaptation at the rural-urban interface (CitationInwood and Sharp, 2012; CitationRecasens et al., 2016). Nonetheless, relatively little is still known about success factors, the economic situation of farm businesses, and farm succession in the context of intra-metropolitan areas. Even though scholars present case studies and associated 'best practices', unfortunately it has neither been verified nor evaluated which activities or which methods of organization and management of urban and peri-urban farms lead to economic development and success.

The analyses performed for this study employ a resource-based view, which is specifically aimed at explaining factors in both the development and success of family enterprises, including farms. The main aim of this analysis is to identify and evaluate the success factors for farms located in urban and peri-urban areas. The key research question is: how do different adjustment strategies, tangible and intangible resources affect the success of farms? The research was conducted on the basis of data from 199 commercial urban and peri-urban farms in the Ruhr Metropolis (Germany). This region is an old-industrialized polycentric agglomeration where agriculture has a comparably high level of significance in current land use.

2 Theoretical background: farm success and its determinants

2.1 Measurement and operationalization of the concept of farm success

Use of the conceptual metaphor of 'farm success' requires putting forward a way in which it is to be understood. Success can thus be said to be a concept that is constructed socially, both in a social and economic environment. Moreover, it can be evaluated from the point of view of a particular entity, sector or the economy as a whole (CitationRantamäki-Lahtinen, 2009). Scholars define farm success from various angles (CitationReij and Smaling, 2008; CitationShepherd, 2014; CitationDuffy and Nanhou, 2002). This concept is widely used by practitioners in the field of economics to indicate various types of positively assessed achievements. Success is often understood as: financial or economic success. Financial indicators such as turnover, profitability, performance or return on investment are often used to measure economic success (CitationRantamäki-Lahtinen, 2009; CitationMäkinen, 2013; CitationGloy et al., 2002). Success is also usually identified with the growth in and development of a farm. It can manifest itself as an increase in: employment, production, price of wealth, share in the market, etc. (CitationReij and Smaling, 2008; CitationBigsten and Gebreeyesus, 2007; CitationDautzenberg and Petersen, 2005). Having limited data at their disposal, individual authors most often decide to measure success using only one variable (e.g. profit, income, etc.), but scholars like e.g. CitationDautzenberg and Petersen (2005) and also CitationLumpkin and Dess (1996) argue for the comprehensive measurement of success. However using various economic and financial measures (one variable or composite variable) to evaluate the success of a farm or enterprise does not make it possible to assess success holistically (CitationUrbanowska-Sojkin, 2013). Success can be understood as the extent to which the goals set by the participants themselves have been achieved (CitationRantamäki-Lahtinen, 2009). However, these aims do not always refer to financial elements only. Moreover, the authors further argue that alternative measures of enterprise performance may compete depending on the type and size of these enterprises. For example, privately-owned small companies (also farms) may be driven by goals such as mere survival or subjective goals such as ‘being one’s own boss’; while larger companies may be driven by profit-related motives (CitationGaroma, 2012; CitationBarbieri and Mahoney, 2009). CitationNanhou (2001) claims that analyses based purely on an assumption of profit maximization are not valid for farming. It should be emphasized that a farm often has two interconnected dimensions: the farm and the farmer’s family living on the farm. Profit-making is one element of the farm’s utility function. Other elements may involve job and family satisfaction, power, social prestige, or a desire for a quiet life (CitationHansson et al., 2013; CitationRantamäki-Lahtinen, 2009). Identification of an appropriate definition and measure of business success is especially important in the study of family businesses (CitationHienerth and Kessler, 2006; CitationReij, Smaling 2008).

According to the expected utility theory, while making a decision about allocation of production factors, an entrepreneur or a farmer takes both financial and non-financial aims into account (CitationBertoni and Cavicchioli, 2016). Thus, while conducting research into small enterprises, including farms, it should be clear that the manager needs to be focused for his/her opinion on this matter (CitationBerner et al., 2012). CitationAbban (2009) takes the view that success is better understood if defined from the personal view of the owner of the business. This argument is based on the fact that some entrepreneurs define success as self-fulfilment. Such a method of measurement is above all used in microeconomic analyses where success is measured for a particular entity (CitationRantamäki-Lahtinen, 2009). Most authors agree that one of the elements that show the success of a farm is its duration, and finally its succession. Thus, having a successor is something that provides information to a partial extent about the good financial conditions of the farm and its development perspectives (CitationKerbler, 2012). Numerous scholars have documented a relationship between the existence of a farm successor and farm revenue, as well as innovation and expansion, while farmers without a successor are more likely to reduce the activity of their enterprise and merge their enterprises (CitationBertoni and Cavicchioli, 2016; CitationInwood and Sharp, 2012; CitationSuess-Reyes and Fuetsch, 2016; CitationMeert et al., 2005).

Based on the aforementioned discussion, success is understood, for the purposes of this analysis, as a farmer’s achievement that is subjectively and positively self-assessed by the farmer, with particular focus on the evaluation of one's own business situation, perspectives for succession and farm development prospects.

2.2 Factors of farm success in urban and peri-urban agriculture

Research concerning the success factors of various enterprises has a long history (CitationDautzenberg and Petersen, 2005). It is generally agreed upon by both scholars and practitioners alike that determinants and the cause of enterprise's success are of both an internal and external nature (CitationMeraner et al., 2015). The forces of success are seen in an internal potential derived not only from resources and their configuration, but also from macro and micro determinants (CitationGursoy and Swanger, 2007; CitationReij and Smaling, 2008; CitationHansson, 2007). According to different schools of economics thought, the source of success is seen in disparate factors. The theory of Industrial Organization (IO) and its most important paradigm: Structure-Conduct-Performance, on the basis of which the later output of M.E. Porter was constructed, made a considerable contribution to current competitive strategies (CitationBarney, 2001). After the fascination with Porter's concept, which puts the emphasis on the competitive surroundings of an enterprise, in the 1990s, the Resource-Based View (RBV) grew in popularity (CitationForsman, 2004). Nowadays, the RBV framework is one of the dominant paradigms in management and research into family businesses (CitationSuess-Reyes and Fuetsch, 2016; CitationRantamäki-Lahtinen, 2009). The RBV combines two different approaches: a management perspective and an economics perspective. It can provide explanations for sustained differences in performance (also success) among enterprises (CitationRantamäki-Lahtinen, 2009) at resource level and firm level. At the resource level, in contrast to Porter's theory, the relation between strategy and resources, and resources and results is seen as inverted. It is claimed that resources are valuable in themselves and as a result they have an influence on the choice of strategy. In other words, strategy is defined based on the unique resources and the capability of an enterprise (CitationŚwiatowiec-Szczepańska, 2012). Many studies concerning factors in the success or even development of farms have been conducted using the resource theory (CitationRantamäki-Lahtinen, 2009; CitationHansson, 2007; CitationWalley et al., 2011; CitationAbdalla, 2012). Scholars have analyzed the meaning of various resources (financial and non-financial), as well as the organization of plant and animal production, production intensity, connection with the market, description of the farmer's family, and the strategies used. While researching socioeconomic aspects of UPA in Sudan, CitationAbdalla (2012) creates a model explaining farm income with the use of such factors as: available resources (land, labour, capital, water), socioeconomic factors (family size, education, age, farm size) and input-output markets (availability, prices and distance). He highlights that these factors affect farmers' decisions/choices with regard to cropping pattern, sales channels, etc. and that, in the end, they affect farm outcome. Analyzing dairy farms in Sweden, CitationHansson (2007) notes that the major factors influencing the choice of development strategies and therefore farm performance are the external and operational environment (geographic location), the internal environment (considerations such as farm layout, quality of the buildings and machinery, specialization) and the micro-social environment (knowledge, support from the family, personal problems of the farmer, etc.). CitationBertoni and Cavicchioli (2016) note in their study on peri-urban farms, that both external factors (labour market, advancement of urbanization processes) and internal factors (such as the characteristics of the farm, farmer and farm household) play a determining role in successful succession. The authors analyze inter alia land resources (greenhouse farming), labour resources, the age and sex of farm managers, and their profession, as well as location factors such as "location in the hills" and "population density".

Numerous studies conducted according to the principles of RBV devote attention to the significance of management and the strategies used to achieve success. CitationBarbieri et al. (2008) and also CitationInwood and Sharp (2012) highlight that farms which can adapt more to urban conditions, namely those which use client-oriented strategies, have better chances for survival and development. Similarly, CitationWästfelt and Zhang (2016) see the main factor for revitalizing UPA in adjustment strategies such as specialization, niche production, multifunctionality in decision-making, food chain management, quality of food and embeddedness of food. They also stress the crucial role of a farm’s location. Research carried out by Cost Action Urban Agriculture Europe also points that the factor of key importance to the development of a farm in urban and peri-urban areas is to be found in adjustment strategies, including the use of appropriate business models. CitationLohrberg et al. (2015) and CitationPölling et al. (2016) identify three main business models: 'specialization’, ‘differentiation’, and ‘diversification’. In the case of the first model, that is specialization through seeking competitive advantage, and the resulting success is achieved by focusing on products characterized by high added value, high transportation costs, freshness and high perishability (CitationPölling et al., 2016; CitationSroka et al., 2016). In the differentiation model, success is achieved by uniqueness in a particular region or business. Adjustment activities are concerned not only with offering products that are thoroughly selected and adjusted to consumers' needs, but also with shortening distribution channels (CitationPölling et al., 2016; CitationVan der Schans et al., 2012). These can, for instance, be products with a certificate of quality or niche products. Diversification is one of the best described business models in the literature. It is noticed that provision of various services especially tourism (recreation, gastronomy, holidays), social services (education, therapy, health, caretaking), and additional public and private services (maintenance, logging, winter road clearance) may form the basis for the development of farm in the context of UPA. Scholars also claim that one of the success factors may be found in introduction of innovation, offering experience, and also the reclaiming of common spaces (CitationLohrberg et al., 2015). In practice, enterprises rarely follow just one business model, but often combine elements of different strategies. Finding combinations that provide synergy is exactly what constitutes a well-run UPA initiative (CitationLohrberg et al., 2015).

2.3 Conceptual framework

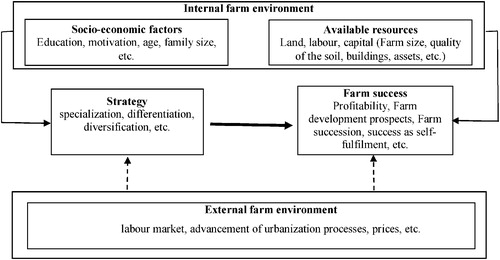

The theoretical and empirical literature reviewed in the preceding sections allows us to develop the conceptual framework. shows a hypothesized relationship between farm environment and farm success. As highlighted in Chapter 2.2, success of farms depends on both internal and external factors. Socioeconomic factors, including farmer’s characteristics (education, motivation, age), available resources (farm size, work resources etc.), are main internal determinant factors in agricultural activity. Moreover, success is affected by farm external environment, including labour market, advancement of urbanization processes, politics, social environment, etc.

According to RBV theory, success is affected by farm strategy, and the strategy depends on possessed resources and opportunities emerging in the external environment. The presented model is path dependent: farm success is affected by farm strategy. Strategy, in turn, is affected by the farm’s external and internal environment (CitationHansson, 2007). Internal farm environment affects success also directly, because the socio economic factors and availability of resources affect the optimal use of resources (CitationRantamäki-Lahtinen, 2009). However, in this approach, of key importance is the strategy, which enables optimal combination of resources and development chances that emerge in the external farm environment (CitationHansson, 2007; CitationVerhees et al., 2018). External farm environment is the same for all the farms (in a particular region/country), therefore it will only affect the success of farms indirectly (CitationBadini et al., 2018). Furthermore, external success factors are less controllable than internal success factors (CitationMarais et al., 2017).

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Data collection

Primary data was mainly used for the purposes of this analysis. A web survey was carried out in 2016 among farmers in the Ruhr MetropolisFootnote1 . Before launching the web survey, iterative pre-tests with 17 participants (mostly farmers) were conducted. Farmers in the Ruhr Metropolis were requested to participate in the survey by sending emails to the farm managers. A list of 2446 email addresses of Ruhr Metropolis farms from the regional Chamber of Agriculture was used to spread the word about the web survey. The first announcement email was sent out by the Chamber of Agriculture beginning of March 2016, followed by an email reminder about two weeks later. There were 199 questionnaires filled out constituting a response rate of 8.1%. The relatively small response rate and small sample size is a limitation of this study. However the use of small sample sizes is not uncommon among studies that utilize surveys to examine factors influencing farmers’ adjustment strategies. For example, CitationBarbieri and Mahoney (2009); CitationBarbieri (2010) and CitationBertoni and Cavicchioli (2016) used observations obtained from samples of 216, 250, and 143 farms, respectively. Moreover, a similar response rate was also obtained in studies by, among others, CitationZapata et al. (2013) - 8.9% for an email survey, and CitationVassalos and Lim (2016) – 3.3%. A potential explanation for the low response rate is that farmers are reluctant in providing personal and business information online due to possible data protection risks, and they are not accustomed to online surveys (CitationVassalos and Lim, 2016). Some scholars also argue that a low response rate does not mean that conclusions cannot be generalized to the entire population. CitationNulty (2008), based on a study by CitationDillman (2000), points out that the minimum response rate in the case of large samples (>2000) can be less than 20%. Even assuming ‘stringent conditions’ (3% sampling error and 95% confidence level), with population of 2000 people, the minimum response rate can be around 20%. CitationFosnacht et al. (2017) note that population estimates derived from a simulated sample with a low response rate are frequently very similar to those based on actual high response rates. Also CitationZapata et al. (2013), citing several recent empirical studies analyzing the links between low response rates and low survey accuracy, suggest a very weak or nonexistent relation between the two. On the other hand, there are views in the literature that a response rate ensuring representativeness of studies should be at least 60%, or even 80% (CitationFincham, 2008).

Our results have to be seen in light of the named response rate, survey mode effect, and coverage error. Emails, by which only three quarters of the target population could be reached, exclude one quarter of Ruhr Metropolis farm managers from survey participation. Thus, the survey is not fully representative of the whole population of farms in Ruhr Metropolis. However, coverage error and the survey mode effect of favoring farm managers who are familiar with the internet are accepted by the authors due to the lack of viable data collection alternatives. Web survey dataset builds a representative sample for the population of Ruhr Metropolis farms with regard to full-time farming, cropland-grassland ratio and share of horticultural farms (). The surveyed farms have around 25% larger area than the average in Ruhr Metropolis, and more often offer horse services. Yet, organic farms and direct marketing farms participated in the web survey respectively twice and four times as often as the total population. Our research therefore covers slightly better farms (the majority declares success) and more often than the average in the Ruhr Metropolis uses different city adjustments strategies.

Table 1 Comparison of basic agricultural data: Web survey 2016 vs. Agricultural Census 2010 and 2016 in Ruhr Metropolis.

Different types of data were collected using the survey tool. Firstly, the survey asks for general information about the farm (full-time, part-time; conventional, organic; farm size; land lease; crops, livestock). This section enabled collection of data on available resources, cropping patterns, but also applied farm strategy/adjustments: high-value and high-quality production, etc. (CitationHansson, 2007; CitationAbdalla, 2012, CitationBertoni and Cavicchioli, 2016). Due to the fact that it is very difficult to quantify and assess the location factor of a particular farm based on official statistics data (CitationBertoni and Cavicchioli, 2016; CitationWästfelt and Zhang, 2016), the survey relied on farmers’ subjective assessments. Farm managers are asked to assess, on bar scales ranging from 0 to 100 (1 point intervals), the subjectively perceived difference between rural and urban farming (0: no difference; 100: very large differences), as well as their farm’s spatial context (0: very rural, 100: very urban). In addition, this second thematic block is used to collect data on the urban advantages and disadvantages of farming. The third block addresses the application of agricultural extension services; the fourth focuses on services; the fifth on processing and (direct) marketing of products. The questions asked in the survey allowed the surveyed farms’ adjustment strategies to be presented. Similar analyses were conducted, among others, by CitationBarbieri et al. (2008); CitationInwood and Sharp (2012) and also CitationWästfelt and Zhang (2016). The sixth thematic block addresses the farm manager’s self-assessment of the farm’s current business situation (bar scale from 0: very bad; 100: very good farm business situation), as well as of future (farming and service) business development strategies along with upcoming decisions on farm succession. Based on them, level of success of the farm was determined. In accordance with the recommendations provided in the literature (CitationRantamäki-Lahtinen, 2009; CitationInwood and Sharp, 2012; CitationBertoni and Cavicchioli, 2016; CitationSuess-Reyes and Fuetsch, 2016), non-financial success measures were used in the study. In the case of family businesses, and farms in particular, success is better understood if defined from the personal view of the owner of the business (CitationAbban, 2009). This approach also eliminates potential problems with farmers’ understanding and proper calculation of such categories as farm income, value of assets, etc. Finally, the socioeconomic data of the farm manager (age, education etc.) and the farm business were also collected. Almost all items were formulated as closed questions in order to make the web survey tool easy to use.

3.2 Data analysis: classification trees

Classification and Regression Trees (CARTs) as one of the most suitable Classification Tree (CT) methods were applied to assess the success factors of farms. This method has been used by other scholars to measure performance of enterprises (CitationDelen et al., 2013), and also to assess the rating of SMEs (CitationCampanella, 2014), the success of services in e-commerce (CitationLee et al., 2007) and the socio-economic determinants of urban households keeping livestock (CitationThys et al., 2005). It has also been used in a study of why sub-alpine grasslands revert to forest (CitationGellrich et al., 2008).

CARTs have a number of advantages over other models (and over the very popular regression models inter alia). Their structure is non-parametric, small trees are readily interpretable, there is no global sensitivity to outliers, and they are able to handle non-linear relationships well (CitationMahjoobi and Etemad-Shahidi, 2008; CitationDębska and Guzowska-Świder, 2011). Therefore, there is no implicit assumption that the underlying relationships between the predictor variables and the dependent variable are linear, follow some specific non-linear link function, or that they are even monotonic in nature. For example, some continuous outcome variable of interest could be positively related to a variable “Income” if the income is less than some certain amount, but negatively related if it is more than that amount (i.e., the tree could reveal multiple splits based on the same variable “Income”, revealing such a non-monotonic relationship between the variables) (CitationHill and Lewicki, 2006). Further advantages are seen in the fact that regression and classifications trees are suitable for a larger number of variables, thus avoiding the necessity of a strong pre-selection of the variables before modelling. The problem of collinear variables is automatically handled by the stepwise procedure of the approach. Hence, CTs select and combine the most relevant factors in a well-defined model structure (CitationRouha-Mülleder et al., 2009). The module is used to assign cases or objects to qualitative variable classes based on the evaluation of explanatory variables (attributes or characteristics, called predictors) (CitationDębska and Guzowska-Świder, 2011).

CART is a binary decision tree algorithm capable of processing continuous or categorical predictor or target variables. It works recursively: data is partitioned into two subsets to make the records in each subset more homogeneous than in the previous subset; the two subsets are then split again until the homogeneity criterion or some other stopping criteria is satisfied (CitationBreiman et al., 1984; CitationDelen et al., 2013). The same predictor field may be used many times in the tree, and the more often it appears in tree divisions, the more importance is given to the description of this dependent variable (CitationFerraro et al., 2009). The classification process starts at the root node (which encompasses the entire dataset) and ends at the terminal nodes. A developed CT encodes a set of decision rules in form of “if…, then …” (CitationDacko et al., 2016), which are analogous to the decisions made by farmers while managing their holdings (CitationGellrich et al., 2008). In choosing the best splitter, the program seeks to maximize the average “purity’’ of the two child nodes (CitationSpeybroeck et al., 2004). The traditional recursive partitioning approaches of CART use empirical entropy-based measures, such as the Gini gain or the information gain, as split selection criteria (CitationStrobl et al., 2007). The Gini node measure is defined by the equation:where p(j|t) = p(j, t)/p(t) and p(j, t) = π (j)Nj(t)/Nj

p(j|t) is the estimated probability that an observation belongs to group j given that it is in node t, p(j, t) is the estimated probability that an observation is in group j and at node t, p(t) is the estimated probability that an observation is at node t, p(t) = N(t)/N, π (j) is the prior probability for group j, Nj(t) is the number of group j members at node t, and Nj is the size of group j (CitationDębska and Guzowska-Świder, 2011).

The cross-validation was applied to assess the optimal model complexity and minimize the risk of overfitting (CitationRonowicz et al., 2015). V-fold Cross-Validation (CV) involves the determination of a number of random sub-samples (in this case 10), which are extracted from the learning sample. Trees of certain size are calculated V = 10 times, where, successively, one of the sub-samples is omitted in the calculation and used as the test sample in the cross-validation. Accordingly, each sub-sample is used V - 1 = 9 times in the learning sample and once as a test sample (CitationDacko et al., 2016). Furthermore, to avoid undesired model complexity, in our work the minimum size of each node which was divided into child nodes was defined as 5 cases. It means that any split of a node containing less than 5 cases was not accepted.

Classification tree models aim to pinpoint logical rules that explain diversity of a particular phenomenon (in this case: farm success). It is also important to check whether the constructed model possesses predictive capability. The quality of models used in binary data (two-groups) is often measured by using an AUC “Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve’’ based on an independent dataset (CitationDelen et al., 2013). AUC values close to 0.5 indicate low similarity between the observed and predicted values, whereas values close to 1.0 indicate high similarities between the observed and predicted values. According to CitationGellrich et al. (2008), the accuracy of the ROC-AUC test is: 0.9–1 = excellent, 0.8–0.9 = good and 0.7–0.8 = fair.

In our work, all calculations were performed with the use of STATISTICA 12 software (StatSoft, Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA).

3.3 Definition of research variables

The selection of variables is a key issue since the chosen variables basically decide on the quality of the analyses. Farm success can be understood in many alternative ways, hence this research presents success via three separate variables (three models will be constructed). In the first model, success is estimated by farmers who assessed their business situation on scales of 0–100 (0-very bad, 100-very good). Since classification trees require the use of a qualitative variable, this variable has been transformed into a dummy variable. Farms, for which the business situation was rated higher than on average (above 58 points), were considered to have achieved a high degree of success. Whereas farmers who estimated their business situation under 58 points () were considered to have a low level of success. The question about self-assessment of a farm’s situation was answered by 157 farmers, hence the analyses encompassed the same number of farms.

Table 2 Description of dependent variables.

Plans for farm development in the future are also seen as a measure of success (success indicator 2). Among the farms surveyed, 83 farmers declared development of an agricultural activity and/or accompanying services, while 62 are planning limitations of production, exit from agriculture or a change in production profile. In the third model, success is equated with having a successor. Farms that achieved success were entities in which farm managers confirmed that they have a declared successor or in which succession is likely assured. 81 farmers answered that question positively, whereas the lack of successors was noted on 66 farms. Allowing the use of three different variables in the research facilitates the analysis of success on various levels. The self- assessment of business situation (success indicator 1) by a farmer not only makes it possible to see the specific character of a family farm (hence not merely in terms of its financial aims), but it also reflects the current farm situation and may be dependent on a temporary changes in the market, weather, etc. For this reason, two other variables have been included; they show the chances of farm development over a longer-term perspective (strategic one). In the second example, success is depicted as a positive prospect of farm development (success indicator 2). Having a declared successor (success indicator 3) is depicted in the literature as the basic measure of success (see Section 2.2). The relevance of measuring success in this way at three different levels is also shown by the relatively low correlation (Spearman's rank correlation coefficient of under 0.5) between these variables.

The assessment of determinants of farm success requires the identification of independent variables. Since this research is of a statistical nature and concerns farms located in one agglomeration, the analysis of external factors has been abandoned. It should be noted that these factors are very similar for all the analyzed farms. The Resource-Based View (RBV) approach has been used in the research. The RBV combines two different approaches: a management perspective and an economics perspective. The economic potential of farms (their success) is dependent upon accurately selected farm resources, their configuration and capability of being used. Independent variables have been selected on the basis of the literature (described in Section 2.2) and they concern farm resources, farmer characteristics, farm location and adjustment strategies (). Both quantitative and qualitative variables have been analyzed in this approach.

Table 3 Description of independent variables.

The analysis encompassed 199 farms, but it is necessary to mention that some farmers did not answer all the questions, hence the number varied in different stages of the analysis (in particular models). The farms surveyed have about 51.7 ha of AL on average, with the largest farm having 330 ha, while the smallest one had 1.6 ha. On average more than half of farmers declare that they work in, and earn a living mainly from their farms. Over 80% of the farms analyzed show various elements of activities involved in adjustment to urban conditions that have become part of diversification, differentiation and specialization strategies. They employ short supply chains, offer a wide variety of services in the area of tourism (horse-riding, gastronomy, accommodation, etc.) and they also try to favour their own production, e.g., via certificates.

4 Results

4.1 Farm success: current farm business situation

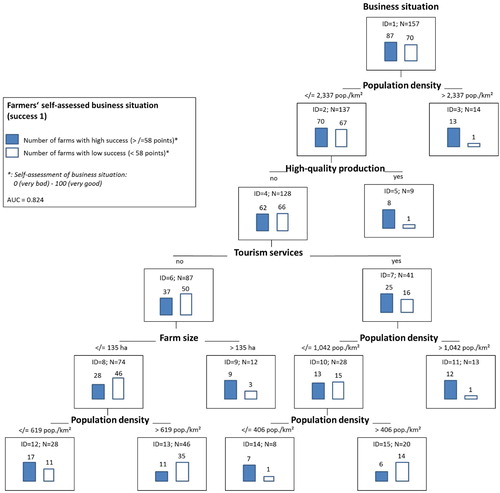

Farm success is a multidimensional and subjective concept. Farmers’ assessment of their farm business situation is used in the first stage of analysis. In order to evaluate how specific characteristics of farm resources, as well as various features of farmers, especially location and elements of the strategies used, have an influence on farm success, two groups of entities are distinguished: 87 farms with high success and 70 with low success. The modelling results are depicted in . The analysis of the tree structure shows that its first and most important division (on branches marked by node ID 1 and ID 2) is according to population density in a municipality. In the subset of 14 farms, which are located in very densely populated areas (municipalities with a population density > 2337 people per km2), high success is declared by 13 farmers. Twelve of them are multifunctional farms, well-adjusted to urban conditions, effectively supplementing their incomes with the provision of various services (tourism and/or social services) and/or using short distribution channels. In municipalities with lower population densities, the ratio of farms with high and low success is relatively even (70 - high success, 67 - low success). In municipalities below the high threshold of population density (<2337 people per km2), a positive influence on success is ascribed to: high-quality production (production based on organic methods) and the provision of tourism services. In the first example (node ID 5), out of nine farms that focus on organic production, eight are seen as entities achieving high success. In the second case, among farms located in municipalities with population density under 2337 people per km2 and without high-quality production, 25 out of 41 farms, which provide tourism services, declared a high level of success. High success is achieved mainly by farmers who provide tourism services in municipalities with a population density above 1042 people per km2 (node ID 11), where twelve out of 13 farms declared high success, and also by farmers located in municipalities with population densities under 406 people per km2 (node ID 14).

Fig. 2 Classification tree explaining self-assessment of farm business situation (success 1).

As a result of lack of data, it may sometimes be the case that the sum of objects in child notes is not equivalent to the number of objects in a split node.

By analyzing other divisions of the classification tree, it should be pointed out that the success of farms, which are located in municipalities with population densities under 2337 people per km2 and offer neither high-quality production nor tourism services, is dependent upon the farm size (node ID 6). Taking entities larger than 135 ha into account, a considerable amount of them achieves success. The research also highlights that, in the case of farms smaller than 135 ha that do not take advantage of an asset of urban location (do not provide tourism services, rarely use short distribution channels etc.), their location in a zone of urban-rural transition (in this case: above 619 people per km2) has an influence on the lower assessment of their business situation (node ID 13). Thus, it would appear that in densely populated municipalities where various adjustment elements are not implemented, the achievement of success seems to be less likely, except for farms with higher land endowment.

4.2 Farm success: plans concerning development

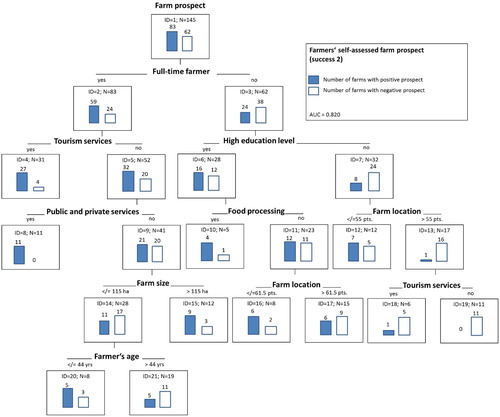

Evaluating farm success from both a medium and long-term perspective, farmers were asked about their plans concerning the development of (or investment in) agricultural and non-agricultural activity (broadening activities, e.g. tourism services) in the future (). Eighty-three out of 145 farmers, who answered the questions, assessed the perspectives for development as positive. The variable, on which farmers' intentions diversified most, is the farmer's involvement in working on a farm. Full-time farmers showed an interest in farm development more often than non-full-time farmers (node ID 2).

Fig. 3 Classification tree explaining positive prospects of farm development (success 2). As a result of lack of data, it may sometimes be the case that the sum of objects in child notes is not equivalent to the number of objects in a split node.

As a result of lack of data, it may sometimes be the case that the sum of objects in child notes is not equivalent to the number of objects in a split node.

The probability of achieving success increased with the use of adjustment strategies, such as tourism services, public and private services, by farmers. Twenty-seven out of 31 farmers, who work and earn their living mainly from a farm and provide tourism services, have plans for farm development (node ID 4). Even if they do not offer tourism services, but instead provide public and private services (node ID 8), they (that is, 11 farmers) declare positive prospects of development. In case of other farmers, who earn their living from working on a farm but do not provide tourism or public and private services, the proportions between managers assessing development positively and negatively are balanced (node ID 9).

The result of the research indicate that – for full-time farmers without tourism, private and public services – the assessment of positive farm prospects are dependent upon farm size. Farmers managing a larger acreage (above 115 ha) develop their farms (node ID 15) more frequently (9 out of 12 farmers) than smaller competitors. Among smaller farms, it is the entities managed by relatively young farmers (node ID 20) that have the higher chances of development. Analyzing a group of farmers, who work and earn their living mainly from non-agriculture (part-time farmers), 38 out of 62 of them assess development perspectives as negative (node ID 3). When farmers have lower level of education and their farms are located in a more urbanized zone (farm location above 52 points), 16 out of 17 farmers declare an unwillingness with regard to development (ID 13). On the other hand, a high level of education combined with food processing (node ID 10) results in higher probabilities of success. Scrutiny of the division of the classification tree also indicates that in Model 2 success/failure is determined by a combination of farm location and adjustment strategies. In the case of part-time farmers, location in a more urbanized area and a lack of adjustment strategies (tourism services (node ID 13) and food processing (node ID 17)) strongly indicate farmers’ unwillingness to develop the farm viable for the future.

4.3 Farm success: prosperous succession

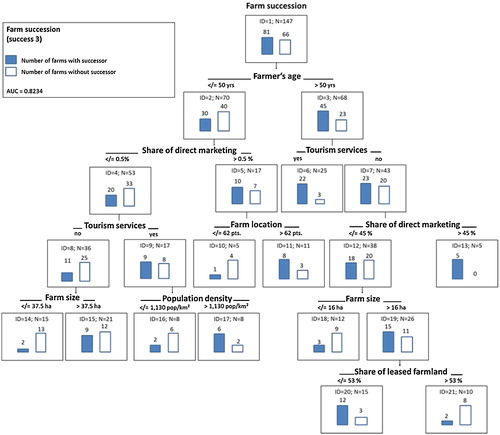

The success of farms is often equated with a prosperous succession or a high probability of its occurrence. Among 147 farmers, who assessed their succession chances, 81 state that they have or are likely to have a successor (). The variable which has the strongest influence on succession perspectives is the age of farm managers. Farmers who are somewhat older (over 50 years of age) agreed more frequently that they could pass their farm on to a successor. Their case shows that it is farmers who provide tourism services that have the best chances for success, because 22/25 farmers declare that they have a successor in this case (node ID 6). The percentage of products sold via direct marketing (node ID 13) also has a positive influence on chances for succession. The remaining farmers (over 50 years of age), who do not provide tourism services and sell less than 45% of their products directly to customers, declare a lack of successor more often (20 farmers without successor out of a total 38). Larger acreage of land turns out to be a factor that multiplies the chance for succession. In entities which possess more than 16 ha and have mostly their own land (ID 20), 12/15 farmers have a successor. The chances for a successful succession are strongly limited in smaller farms (node ID 18) and also in farms using mainly leased land (node ID 21).

Fig. 4 Classification tree explaining farm succession (success 3).

As a result of lack of data, it may sometimes be the case that the sum of objects in child notes is not equivalent to the number of objects in a split node.

It may be harder than expected to assess the prospects of succession of younger farmers, because their children are mostly young and hence this fact may have a negative influence on the chances of succession. Analyzing the results obtained, it should be emphasized that, in a similar way to older farmers, the perspectives of succession are differentiated according to the percentage of products sold through short distribution channels. In farms, where more than 0.5% of products are sold directly to customers, 10 out of 17 farmers declare having a successor (node ID 5). In this case, the factor that strengthens chances for succession is location in an urban area (node ID 11). Moreover, the location of farms in such areas enables better use of short distribution channels, and thus is favourable to farm development. Analysis of the tree structure also shows that farmers who are over 50 years of age and take no advantage of short distribution channels (<0.5% - hardly ever use short supply chains), but provide tourism services, declare that they have a successor (node ID 9) more often than other farmers. Additionally, being located in more urbanized municipalities (population density of over 1130 people per km²) also has a positive influence on chances for succession (node ID 17). Younger farmers (under 50 years of age), who neither introduce city-adjusted short supply food strategies nor provide tourism services on their farms, for the most part do not have a declared successor (25/36 farmers). In their case, farm size seems to be the factor with a positive influence on the chances of passing the farm on to a successor (node ID 8). For farms larger than 37.5 ha (node ID 15), nine out of 21 farmers state that they have a successor, while for smaller entities only 2/15 farmers do (node ID 14).

The results of the research conducted with the use of classification trees (–) indicate that particular variables describe farm success very well. One of the measures that enable the quality of prediction to be assessed is an analysis of the ROC curve, which describes the probability of the correct object classification (in this case: which farms achieve success and which do not). In the case of all three models, the value of the Area Under the ROC Curve exceeds 0.8 which is considered to be a good result. It means that the independent variables used for building the tree represent the most important factors influencing farm success.

5 Discussion

The main purpose of this paper has been to provide empirical evidence of the impact of factors related to farm resources, the location of production and, above all, adjustment strategies that have an influence on success in highly-urbanized areas. The study has been motivated by the rapidly changing status of urban and peri-urban farms in Europe, where many farms are going out of business and agricultural land is being changed into land for non-agricultural activities in business or housing or other areas. Though it is very often highlighted in the literature that the adjustment strategies of a farm, including specialization, diversification and differentiation play a crucial role in the development and economic success of farms, scholars usually discuss the matter from a theoretical perspective or present results of research based on case studies (CitationLohrberg et al., 2015). In this analysis, the thesis about the decisive role of adjustment strategies in both the development and success of farms has been analysed empirically, and the research encompassed 199 farms conducting agricultural activities in the largest agglomeration in Germany, the Ruhr Metropolis.

Farm success was measured by the use of three separate variables, but in each model, the decisions made by farm managers about the operating strategies applied, the size of farms and also their location seem to be of crucial significance. While there is indication to also explain farm success, the other variables are somewhat less significant. The classification tree method indicates that the applied strategies are of utmost importance to farm success. These strategies appear in all models and their use increases the probability of achieving success.

In the Ruhr Metropolis, differentiated and diversified farm adjustments seem to constitute the most suitable business paths in terms of business situation, development perspectives and succession (CitationPölling et al., 2017). Results indicate that the provision of tourism services, especially horse-riding, constitutes the most successful strategy. About 70% of entities in our sample which provide these services declare success (it applies to all three measures of success). It is very often indicated by scholars as being particularly well-suited to implementation in peri-urban areas (CitationZasada et al., 2013; CitationOpitz et al., 2016; CitationPölling et al., 2016). The second element of strategy, which is identified in divisions of classification trees, is the percentage of sales through short distribution channels. About 60% of farms, which sell more than 20% of their production outside long value chains, achieve high success, 67% declare that they have a successor, and over 75% state that they have positive chances for development in our data. These results are higher compared to those farms which do not concentrate on direct sale because on average (for the three measures of success) only 53% of these farms achieve success. Also, in the literature, it is stated that shortening distribution channels is a strategy that is especially appropriate to UPA(CitationPölling et al., 2016; CitationVan der Schans and Wiskerke, 2012; CitationSharp and Smith, 2004). One strategy, which is quite rarely used by the farms surveyed, but raises the probability of achieving high success considerably, is high-quality production. Eight out of nine farms that conduct organic production, which is a part of differentiation and niche production, declare success in our sample. It can be concluded that farms in peri-urban and urban areas are also suggested to be in an advantageous position to operate in innovative and niche ways that offer an alternative to larger entities in mainstream farming (CitationZasada, 2011; CitationInwood and Sharp, 2012; CitationWästfelt and Zhang, 2016). Variables which present elements of strategy, but do not appear in any models are high-value production and share of high-value production. This is rather the result of the low importance of this type of farming in the farms surveyed. CitationPölling et al. (2016) state that in the Ruhr Metropolis the low-cost strategy according to which producers concentrate on vegetable farming does indeed play an important role, but it is not particularly suitable for implementation in highly-urbanized areas.

Findings indicate that the use of strategies oriented towards urban customers increases the probability of success, but their effectiveness is also dependent upon other factors. The research explicitly noted that one of the most crucial variables in explaining farm success is the location of a farm (this variable is evident in all models). On the one hand, this variable can be seen as an impetus for development and success, but on the other hand, it can hamper development considerably. Success is achieved by farms which both adjusted their offer (city-adjusted business strategies) to local conditions and take advantage of their location (CitationZasada, 2011; CitationLohrberg et al., 2015; CitationWästfelt and Zhang, 2016). The results for the first model () show that 13 out of 14 farms located in municipalities with population density over 2337 people per km2 achieve success. These are multifunctional entities which supplement their incomes effectively by providing various services and by using short distribution channels. The same model also indicates that when a farm provides tourism services (horses, gastronomy, recreation, etc.) and is located in municipalities with a population density of over 1042 people per km2, twelve out of 14 farms achieve success. A similar connection is indicated in model number 3 (): farms, which provide tourism services, and are located in municipalities with a relatively higher population density, show higher probabilities of a favourable succession than farms in less-urbanized areas. The data in our research also highlighted that urban locations limit the possibility for success considerably when farm managers do not use adequate city-adjustment strategies. The results for model 1 indicate that farms, which neither conduct high-quality production nor provide tourism services and at the same time farm size is below 135 ha, achieve low success (38/46 farms) in municipalities with certain population density (over 619 people per km2). Applying the same premises to entities with population densities under 619 inhabitants per km2, it can be noted that 18 out of 28 farms achieve high success. The analysis of model 2 indicates similar results (). Highly-educated part-time farmers, who do not use food processing, see negative prospects of farm development (9 out of 15 farmers) when the farm location is described as rather urban (above 61 points, where 100 points = very urban character of an area, and 0 points = very rural). Again, applying the same premises, but on condition that a farm is located in an area that is peri-urban or rather rural (under 61 points), six out of eight farmers declare positive prospects of development.

In trying to explain the significance of farm location in the context of a farm’s development and achievement of success, reference should be made to the mechanism of bid-rent theory, which was first noticed by Citationvon Thünen (1826) and then modified by CitationAlonso (1964). Alonso's bid-rent theory explained the relationship between land prices and land use as follows: in a competitive land market, land-users seek to maximize their utility, being land rented by the bidder offering the highest bid, i.e. the potential land-user able to derive the highest rent from land. Therefore, land is expected to be used for the purpose which brings the highest utility, taking into account the relative benefits of alternative land uses (CitationDiogo et al., 2015). CitationSinclair (1967) has also noted that high land value driven by urbanization has a negative impact on maintaining agricultural land in urban and peri-urban areas. It should be noted that considerable competition is evident in areas with high population density, and activities which bring high bid rent, supplant those which are less profitable from cities, including agriculture, which usually generates a low rent. Not only does this phenomenon result in a decrease in the number of farms in highly urbanized areas (CitationPiorr et al., 2011), but it also creates farms that are innovative and achieve success. High competition causes that, in agriculture, only entities that are the strongest and most well-adjusted to local conditions maintain and/or prosper (CitationSroka, 2015). Agricultural producers will choose to develop their agricultural activity under conditions that bring higher benefits than alternative activities. Therefore, in highly populated zones, for the most part only farms that are multifunctional and well-adjusted to cities have survived. A similar conclusion has been drawn inter alia by CitationPölling et al. (2016); CitationWästfelt and Zhang (2016); CitationLovell (2010), and also CitationSroka (2015). In a highly urbanized area, where there is little possibility of increase in size and production intensity, appropriate strategies play the most important part (CitationInwood and Sharp, 2012; CitationSpecht et al., 2014). Closeness to market is of high significance especially for farms offering tourism services ( and ) and direct sale (), because it enables customers to have easier and immediate contact with a farm (CitationAubry and Kebir, 2013). In this case, the closer a farm is located to highly urbanized areas, the higher the probability of achieving success is. This relation is also noted by CitationWästfelt and Zhang (2016), who – similarly to us – state that the distance from market that is described by von Thünen currently has a slightly different meaning. Nowadays, the expediency of the prevalence of farms in highly urbanized areas is not dependent upon low costs of transport of products to cities, but it is seen in the availability of farms for customers, who are ready to visit the farm. In highly urbanized countries, both the origin of a product and the reliance on a particular producer play the most important role for customers (CitationWästfelt and Zhang, 2016). We think that the broadly defined concept of transport costs should come under close scrutiny from the point of view of customers, their time and spatial access to farms.

The results of the analysis also indicate that one important factor in a farm’s success is a farm’s size. This applies mainly to those entities which do not use adjustment strategies ( and ), but rely first and foremost on the economies of scale effect (CitationGarcía-Arias et al., 2015; CitationBertoni and Cavicchioli, 2016). This concept coincides not only with the research carried out for farms located in rural areas, but also with common trends in agriculture (CitationInwood and Sharp, 2012). This strategy is adequate for farms located in less densely populated areas of urban-rural transition (CitationPölling et al., 2016).

The last issue that should be highlighted is the difference between success factors depending on the way success has been defined. In the first case, success was evaluated on the basis of the present business situation, and the two other variables concerning the future of farms in terms of having a successor () and positive prospects of development (). In the first model, such success factors were predominant: elements of farm strategy, location and farm size, and in the next model, apart from strategies, the variable concerning involvement in terms of working time (full-time farmer) appeared to be one of the key factors in development. It turns out that, viewed over a long-term perspective, this variable will play an important role in maintenance and development of agricultural activity (CitationVergara et al., 2004). It should be noted that in our research, only 33% of part-time farmers declare positive prospects of development, while over 70% do not use any adjustment strategies. For part-time farmers, the vast possibilities of finding a job out of agriculture will make them more inclined to leave the sector of agriculture (CitationWästfelt and Zhang, 2016; CitationPölling, 2016; CitationHeimlich and Barnard, 1992) unless a farmer is able to obtain a relatively high income from agriculture. It might be possible by using adequate strategies (in our case, first and foremost, tourism services). Part-time farmers who do not generate high enough market incomes to be successful might still fulfil important functions with respect to the provision of public goods like landscape, biodiversity and air quality.

In this analysis, the high education level of farmers has also been pinpointed as having a positive influence on development perspectives, a conclusion which is also confirmed by research done by other scholars (CitationChaplin et al., 2004; CitationMishra et al., 2010). However, in the literature, there is still a lack of a consensus in terms of influence of the level of farmers' education on development perspectives and farm succession. CitationBertoni and Cavicchioli (2016) claim, for instance, that high level of education of farmers does not favour farm development because their well-educated children might not be interested in inheriting the farm. When assessing success in terms of farm succession, the age of farmers () turned out to be the most important variable. Older farmers more frequently have successors, and at the same time, based on this model, the perspectives of succession are mainly dependent upon the strategies used, which has also been confirmed by CitationMcNamara and Weiss (2005).

According to our research, it is farm managers of small farms that do not provide tourism services or use short distribution channels that will have the lowest chances of success. CitationInwood and Sharp (2012) have also emphasized the fact that managers who possess a successor more often use development strategies.

6 Conclusion

We analyzed the determinants of farm success in a sample of German farms located in a wider metropolitan area. As well as investigating the effects of various factors (according to the resource-based view) included traditionally in research on farm success, we also incorporated variables designed to capture the influence exerted by surrounding conditions such as farm location and farm city-adjustments. The main research problem concerned: how do different adjustment strategies, tangible and intangible resources, affect the success of farms? Data from the web survey conducted among farm managers in the German Ruhr Metropolis indicate that farms which use various adjustment strategies are more successful. Compared to their counterpart, city-adjusted farms claim a better economic farm situation, predict more positive farm prospects and (are likely to) assure farm succession in our sample. In all models, the use of adequate strategies (city adjustments) contributed to the higher success of farms. However, particular strategies were characterized by different degrees of effectiveness in terms of various conditions, including mainly the farm’s location.

Our data from Ruhr Metropolis farmers indicate, that success is a consequence of synergies of variables, especially the farm’s location and the types of strategies used. We have also noted that the farm’s location in densely populated areas may be seen as either an advantage of, or a threat to development. It becomes an asset when adequate strategies, including mainly tourism services and different forms of direct sale, are used. Key significance is given to distance from the market and the broadly defined transport costs that customers have to pay when travelling to a farm. A farm location, which is convenient for a customer, results in more frequent sales of products and services which in turn strengthens relations with, and trust in producers. On the other hand, when a farm is located farther from customers, the described elements of strategy give worse results in our sample.

When assessing farm success from a long-term perspective, it was indicated that considerable importance should be given to the time that the farmer commits to working in agriculture. Full-time farmers plan development of their farms and investments more frequently than other farmers. Positive prospects of development were declared mainly by farmers who provide tourism and other (public and private) services, and also by managers of larger farms. From the perspective of having a successor, farm success is achieved by older farmers (over 50 years of age) who claim to have successors. In this case, the implementation of various elements of adjustment strategies also increased the probability of success. It was also noted that on farms, which do not introduce any strategies of city adjustment, succession is more likely to occur when cultivating larger areas.

When analysing these findings, it should be borne in mind that our results have to be seen in light of the relative low response rate and coverage error. The results were not fully representative of the farm population of Ruhr Metropolis, hence they should be treated as exploratory research. Nonetheless, they contribute to knowledge creation, and have a practical value. Learning from good practices are relevant to leverage city-adjustments of farms to maintain their profitability and simultaneously to provide positive externalities for society and environment.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participating farm managers for their valuable contributions to this survey, which was conducted in close cooperation with Manuela Meraner and Prof. Dr. Robert Finger from Agricultural Economics and Policy, ETH Zürich. Additionally, we express our thanks to the Chamber of Agriculture for North Rhine-Westphalia, which sent out the emails to the farm managers.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. However, scientific internship of Wojciech Sroka, PhD, supported by the National Science Centre, Poland under project no 2016/21/D/HS4/00264, contributed to the development of this paper.

Notes

1 Ruhr Metropolis (Metropole Ruhr) is a polycentric urban area in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. Is the largest German urban agglomeration – both in terms of size and population. More than five million people live in an area of around 4,400 square kilometers (Pölling et al., 2016).

References

- J.R.AbbanGhanaian Graduates in Enterprise PhD. Thesis2009The Hague: International Institute of Social Studieshttp://repub.eur.nl/pub/32653

- I.F.AbdallaSocioeconomic aspects of urban and peri-urban agriculture: A diagnostic study in Khartoum, Sudan2012Kassel University Press GmbH. ISBN print 978-3-86219-268-7

- W.AlonsoLocation and Land Use1964Harvard University PressCambridge, USA

- A.AngusP.J.BurgessJ.MorrisJ.LingardAgriculture and land use: demand for and supply of agricultural commodities, characteristics of the farming and food industries, and implications for land use in the UKLand Use Policy262009230242

- D.AubryL.KebirShortening food supply chains: a means for maintaining agriculture close to urban areas? The case of the French metropolitan area of ParisFood Policy4120138589

- C.AubryJ.RamamonjisoaM.H.DabatJ.RakotoarisoaJ.RakotondraibeL.RabeharisoaUrban agriculture and land use in cities: an approach with the multi-functionality and sustainability concepts in the case of Antananarivo (Madagascar)Land Use Policy2922012429439

- O.S.BadiniR.HajjarR.KozakCritical success factors for small and medium forest enterprises: a reviewFor. Policy Econ.9420183545

- C.BarbieriAn importance-performance analysis of the motivations behind agritourism and other farm enterprise developments in CanadaJ. Rural Community Dev.51/22010120

- C.BarbieriE.MahoneyWhy is diversification an attractive farm adjustment strategy? Insights from Texas farmers and ranchersJ. Rural Stud.25120095866

- C.BarbieriE.MahoneyL.ButlerUnderstanding the nature and extent of farm and ranch diversification in North AmericaRural Sociol.7322008205229

- J.B.BarneyResource-based theories of competitive advantage: a ten-year retrospective on the resource-based viewJ. Manage.2762001643650

- E.BernerG.GomezP.KnorringaHelping a large number of people become a little less poor: the logic of survival entrepreneursEur. J. Dev. Res.2432012382396

- D.BertoniD.CavicchioliFarm succession, occupational choice and farm adaptation at the rural-urban interface: the case of Italian horticultural farmsLand Use Policy572016739748

- A.BigstenM.GebreeyesusThe small, the young and the productive: determinants of manufacturing firm growth in EthiopiaEcon. Dev. Cult. Change5542007813838

- L.BreimanJ.H.FriedmanR.A.OlshenC.J.StoneClassification and Regression Trees1984Wadsworth & BrooksMonterey, CA

- C.BrinkleyEvaluating the benefits of peri-urban agricultureJ. Plan. Lit.2732012259269

- F.CampanellaAssess the rating of SMEs by using classification and regression trees (CART) with qualitative variablesQ. Rev. Econ. Finance420141632

- H.ChaplinS.DavidovaM.GortonAgricultural adjustment and the diversification of farm households and corporate farms in Central EuropeJ. Rural Stud.20120046177

- M.DackoT.ZającA.SynowiecA.OleksyA.Klimek-KopyraB.KuligNew approach to determine biological and environmental factors influencing mass of a single pea (Pisum sativum L.) seed in Silesia region in Poland using a CART modelEur. J. Agron.7420162937

- K.DautzenbergV.PetersenErfolgsfaktoren in landwirtschaftlichen Unternehmen. Success factors in agricultural enterprisesGerman Journal of Agricultural Economics542005331340

- B.DębskaB.Guzowska-ŚwiderDecision trees in selection of featured determined food qualityAnal. Chim. Acta70512011261271

- D.DelenC.KuzeyA.UyarMeasuring firm performance using financial ratios: a decision tree approachExpert Syst. Appl.4010201339703983

- D.A.DillmanMail and Internet Surveys: the Tailored Design Method2000WileyBrisbane

- V.DiogoE.KoomenT.KuhlmanAn economic theory-based explanatory model of agricultural land-use patterns: the Netherlands as a case studyAgric. Syst.1392015116

- M.DuffyV.NanhouFactors of Success of small farms and the relationship between financial Success and perceived SuccessStaff General Research Papers With Number 103492002Iowa State University, Dept. of EconomicsAmes USA

- D.O.FerraroD.E.RiveroC.M.GhersaAn analysis of the factors that influence sugarcane yield in Northern Argentina using classification and regression treesField Crops Res.11222009149157

- J.E.FinchamResponse rates and responsiveness for surveys, standards, and the JournalAm. J. Pharm. Educ.722200843

- S.ForsmanHow do small rural food-processing firms compete? A resource-based approach to competitive strategiesAgric. Food Sci.1320041130

- K.FosnachtS.SarrafE.HoweL.K.PeckHow important are high response rates for college surveys?Rev. High. Ed.4022017245265

- A.I.García-AriasI.Vázquez-GonzálezF.Sineiro-GarcíaM.Pérez-FraFarm diversification strategies in northwestern Spain: factors affecting transitional pathwaysLand Use Policy492015413425

- B.F.GaromaDeterminants of Microenterprise Success in the Urban Informal Sector of Addis Ababa: A Multidimensional Analysis Retrieved from2012International Institute of Social Studies of Erasmus Universityhttp://repub.eur.nl/pub/37927/

- M.GellrichP.BaurB.H.RobinsonP.BebiCombining classification tree analyses with interviews to study why sub-alpine grasslands sometimes revert to forest: a case study from the Swiss AlpsAgric. Syst.9612008124138

- B.A.GloyJ.HydeE.L.LaDueDairy farm management and long-term farm financial performanceAgric. Resour. Econ. Rev.3122002233

- D.GursoyN.SwangerPerformance-enhancing internal strategic factors and competencies: impacts on financial successInt. J. Hosp. Manag.2612007213227

- H.HanssonStrategy factors as drivers and restraints on dairy farm performance: evidence from SwedenAgric. Syst.9432007726737

- H.HanssonR.FergusonC.OlofssonL.Rantamäki-LahtinenFarmers’ motives for diversifying their farm business - the influence of familyJ. Rural Stud.322013240250

- R.E.HeimlichC.H.BarnardAgricultural adaptation to urbanization: farm types in northeast metropolitan areasNortheastern Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics21119925060

- E.I.HennigC.SchwickT.SoukupE.OrlitováF.KienastJ.A.JaegerMulti-scale analysis of urban sprawl in Europe: towards a European de-sprawling strategyLand Use Policy492015483498

- C.HienerthA.KesslerMeasuring success in family businesses: the concept of configurational fitFam. Bus. Rev.1922006115134

- T.HillP.LewickiStatistics: Methods and Applications: a Comprehensive Reference for Science, Industry, and Data Mining2006StatSoft.Oklahoma

- A.HolO.MubinA.GinigeProposed business model for SME farmers in peri-urban Sydney region, e-Business (ICE-B) . Proposed business model for SME farmers in peri-urban Sydney region, in: e-Business (ICE-B), 2014 11th International Conference on 137-144). IEEE.2014 11th International Conference on 137-144) IEEE(2014)

- D.HuangM.DrescherUrban crops and livestock: the experiences, challenges, and opportunities of planning for urban agriculture in two Canadian provincesLand Use Policy432015114

- S.M.InwoodJ.S.SharpFarm persistence and adaptation at the rural–urban interface: succession and farm adjustmentJ. Rural Stud.2812012107117

- IT.NRWAgricultural Census Data 2010 and 20162016 (Accessed 12 December 2018)http://https://www.landesdatenbank.nrw.de/ldbnrw/online

- B.KerblerFactors affecting farm succession: the case of SloveniaAgricultural Economics (Czech)5862012285298

- S.LeeS.LeeY.ParkA prediction model for success of services in e-commerce using decision tree: E-customer’s attitude towards online serviceExpert Syst. Appl.3332007572581

- F.LohrbergL.LickaL.ScazzosiA.TimpeUrban agriculture europeJOVIS Verlag GmbH, Berlin.2015

- S.T.LovellMultifunctional urban agriculture for sustainable land use planning in the United StatesSustainability20102201024992522

- G.LumpkinG.DessClarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performanceAcad. Manag. Rev.211996135172

- J.MahjoobiA.Etemad-ShahidiAn alternative approach for prediction of significant wave height based on classification and regression treesAppl. Ocean Res.302008172177

- H.MäkinenFarmers’ managerial thinking and management process effectiveness as factors of financial success on Finnish dairy farmsAgric. Food Sci.2242013452465

- M.MaraisE.du PlessisM.SaaymanA review on critical success factors in tourismJ. Hosp. Tour. Manag.312017112

- K.T.McNamaraCh.WeissFarm household income and on-and off-farm diversificationJ. Agric. Appl. Econ.3720053748

- H.MeertG.Van HuylenbroeckT.VernimmenM.BourgeoisE.Van HeckeFarm household survival strategies and diversification on marginal farmsJ. Rural Stud.21120058197

- M.MeranerW.HeijmanT.KuhlmanR.FingerDeterminants of farm diversification in the NetherlandsLand Use Policy422015767780

- A.K.MishraH.S.El-OstaS.ShaikSuccession decisions in US family farm businessesJ. Agr. Res. Econ.2010133152

- H.F.MokV.G.WilliamsonJ.R.GroveK.BurryS.F.BarkerA.J.HamiltonStrawberry fields forever? Urban agriculture in developed countries: a reviewAgron. Sustain. Dev.34120142143

- L.J.A.MougeotUrban Agriculture: Definition, Presence, Potentials and Risks, and Policy Challenges. Cities Feeding People Series Report 312000International Development Research CentreOttawa, Canada

- L.J.A.MougeotGrowing better cities: urban agriculture for sustainable developmentInternational Development Research Centre. Ottawa, Canada.2006

- V.Y.NanhouFactors of Success of Small Farms and the Relationship Between Financial Success and Perceived Success Retrospective Theses and Dissertations2001http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/17190

- D.D.NultyThe adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: what can be done?Assess. Eval. High. Educ.3332008301314

- I.OpitzR.BergesA.PiorrT.KrikserContributing to food security in urban areas: differences between urban agriculture and peri-urban agriculture in the Global NorthAgric. Human Values3322016341358

- A.PiorrJ.RavetzI.TosicsPeri-urbanisation in Europe: Towards European Policies to Sustain Urban-rural Futures. Forest & Landscape2011University of Copenhagen

- B.PöllingComparison of farm structures, success factors, obstacles, clients’ expectations and policy wishes of urban farming’s main business models in North Rhine-WestphaliaGermany. Sustainability85201644610.3390/su8050446

- B.PöllingM.MergenthalerW.LorlebergProfessional urban agriculture and its characteristic business models in Metropolis RuhrGermany. Land Use Policy582016366379

- B.PöllingW.SrokaM.MergenthalerSuccess of urban farming’s city-adjustments and business models – findings from a survey among farmers in Ruhr MetropolisGermany.692017372385 Land Use Policy

- L.Rantamäki-LahtinenThe success of the diversified farm - Resource-based viewAgric. Food Sci.18Suppl. 120091134 PhD dissertation

- X.RecasensO.AlfrancaL.MaldonadoThe adaptation of urban farms to cities: the case of the Alella wine region within the Barcelona Metropolitan RegionLand Use Policy562016158168

- C.P.ReijE.M.A.SmalingAnalyzing successes in agriculture and land management in Sub-Saharan Africa: Is macro-level gloom obscuring positive micro-level change?Land Use Policy2532008410420

- J.RonowiczM.ThommesP.KleinebuddeJ.KrysińskiA data mining approach to optimize pellets manufacturing process based on a decision tree algorithmEur. J. Pharm. Sci.7320154448

- C.Rouha-MüllederC.IbenE.WagnerG.LaahaJ.TroxlerS.WaiblingerRelative importance of factors influencing the prevalence of lameness in Austrian cubicle loose-housed dairy cowsPrev. Vet. Med.9212009123133

- J.S.SharpM.B.SmithFarm operator adjustments and neighboring at the rural-urban interfaceJ. Sustain. Agric.2342004111131

- M.ShepherdContributing Factors to the Success of Small-Scale Diversified Farms in the Mountain West2014Utah State University Doctoral dissertation

- R.SinclairVon Thünen and urban sprawlAnn. Assoc. Am. Geogr.57119677287

- J.SmitJ.NasrUrban agriculture for sustainable cities: using wastes and idle land and water bodies as resourcesEnviron. Urban.421992141152

- K.SpechtR.SiebertI.HartmannU.B.FreisingerM.SawickaA.WernerA.DierichUrban agriculture of the future: an overview of sustainability aspects of food production in and on buildingsAgric. Human Values31120143351

- K.SpechtT.WeithK.SwobodaSocially acceptable urban agriculture businessesAgron. Sustain. Dev.36201610.1007/s13593-016-0355-0

- N.SpeybroeckD.BerkvensA.Mfoukou-NtsakalaM.AertsN.HensG.Van HuylenbroeckE.ThysClassification trees versus multinomial models in the analysis of urban farming systems in Central AfricaAgric. Syst.8022004133149