Highlights

| • | Citizens’ valuations of agricultural biodiversity are poorly understood. | ||||

| • | We explore how valuations, attitudes, underlying and mediating factors are related. | ||||

| • | Students appreciate intrinsic and aesthetic values of agricultural biodiversity. | ||||

| • | Knowledge provision is needed to enhance the valuation of agricultural biodiversity. | ||||

Abstract

Citizens’ valuation of agrobiodiversity is important for retaining political interest in the subject, for legitimising agri-environment schemes and other conservation initiatives and for their own willingness to contribute to agrobiodiversity conservation. Still little is known about whether and how citizens value agrobiodiversity, how these valuations can be explained and what they imply for citizens’ preparedness to contribute to the enhancement of agrobiodiversity. We report on the findings of an exploratory survey aimed at uncovering the above mechanisms among a specific subgroup of Dutch citizens: students. We conclude that (a) students appreciate the intrinsic and aesthetic values of agrobiodiversity to some extent, but not its instrumental value; (b) valuations correlate with students’ fundamental values; (c) students’ attitudes correlate strongly to how they value agrobiodiversity. We recommend follow-up research among a more representative sample of Dutch citizens, with the aims to further test the mechanisms, assess valuations of agrobiodiversity by Dutch citizens in general and explore whether and how these valuations can be enhanced by the provision of information about the intrinsic and aesthetic values of agrobiodiversity.

1 Introduction

Agriculture, the largest land use worldwide, is associated with urgent ecological problems (CitationTanentzap et al., 2015; see CitationWorld Bank, 2019). Conversion of forests and other natural habitats into farming land, intensive farming styles but also land abandonment have contributed to ongoing biodiversity loss (e.g. CitationTscharntke et al., 2005; CitationBos et al., 2013; CitationSanderson et al., 2013; CitationTanentzap et al., 2015). Illustrative is the continuous decline in farmland birds and pollinators and other insects, in Europe and elsewhere (e.g. CitationOllerton et al., 2014; CitationHallmann et al., 2017; CitationEgli et al., 2018). The decline in biodiversity in agricultural landscapes (i.e. species richness and abundance; hereafter: ‘agrobiodiversity’) particularly puts Sustainable Development Goal 15 (life on land) at risk.

The decline in agrobiodiversity has attracted not only the interest from researchers from the natural sciences (e.g. CitationOllerton et al., 2014) but also from social scientists. Social scientific research focuses on the actors involved, particularly on farmers and their perceptions of the decline in agrobiodiversity and attitudes towards conservation. This research has provided valuable insights into the motivations of farmers to engage in conservation (CitationPerry-Hill and Prokopy, 2014; CitationRunhaar et al., 2017, Citation2018), social enablers of nature conservation by farmers (CitationRoep et al., 2003; CitationPretty, 2008; CitationWesterink et al., 2017) as well as a deeper understanding of the barriers to conservation (CitationRoesch-McNally et al., 2017). The role of governments and other actors that aim to promote nature conservation by farmers has been analysed in studies on the effectiveness of agri-environment schemes (CitationRunhaar et al., 2017) and in studies about the politics of integrating agrobiodiversity objectives into agricultural policies (e.g. CitationLowe et al., 2010). Thus far few social scientific studies on citizens’ perceptions of and attitudes towards agrobiodiversity have been conducted (CitationRunhaar, 2017). Yet these perceptions and attitudes matter for retaining political interest in the subject, for support for continued public funding for agri-environment schemes, for legitimising other public and private conservation initiatives, for the legitimacy of the agricultural sector and for estimating citizens’ own willingness to contribute to agrobiodiversity conservation, as voters, consumers, volunteers, activists etc. (CitationStilma et al., 2009; CitationPascucci et al., 2016; CitationRunhaar, 2017). In this paper we aim to get a better insight into this subject by uncovering the mechanisms between valuations of agrobiodiversity, underlying factors and the implications for the willingness of citizens to contribute to the enhancement of agrobiodiversity.

Focusing on a specific category of citizens, namely students in the Netherlands, this paper addresses the following research questions:

| 1 | How do students value agrobiodiversity and what factors account for these valuations? | ||||

| 2 | What is the willingness of students to contribute to the enhancement of agrobiodiversity, and how can this be explained? | ||||

Students are often used in research on environmental attitudes and behaviour (e.g. CitationRikhardsson and Holm, 2008; CitationOpdam et al., 2015; CitationPaço and Lavrador, 2017). Although students are not representative of Dutch citizens in general, they do represent young citizens (CitationRunhaar et al., 2019) and relatively easy to access. They are not representative of Dutch citizens in general, which is not problematic in view of the exploratory nature of our study but obviously does limit the generalisability of our findings in terms of how citizens value agrobiodiversity.

We build on and complement previous, related studies in three ways. One, the broad interpretation of valuations of agrobiodiversity. Some of the few other studies have focussed on very specific dimensions of citizens’ valuations of agrobiodiversity, such as the economic valuation of ecosystem services in agricultural landscapes by CitationBernués et al., 2014). In our study we include not only economic but also other (e.g. intrinsic) values of agrobiodiversity, which allows for a comparison of valuations. Two, we connect valuations to students’ (intended) behaviours, such as their willingness to pay a bit more for food that has been produced in a ‘nature-friendly’ way. And three, we explore explanations for students’ valuations and attitudes. With this approach we hope to provide a basis for follow-up research among a more representative group of (Dutch) citizens.

The remainder of the paper unfolds as follows. In section 2 we outline the materials and methods employed. In section 3 we present our results. A summary of our main conclusions and a reflection on the methodology and the results is described in section 4.

2 Methods

2.1 Theoretical framework

Attitudes can be understood as dispositions towards a particular object after evaluation (CitationAjzen, 2005). Literature on pro-environmental behaviour includes several models for conceptualising attitudes and their formation, including the value-belief-norm theory (CitationStern, 2000), or the Theory of Planned Behaviour (CitationAjzen and Fishbein, 1980). Most of these models are based on a ‘cognitive hierarchy’, suggesting that attitudes are informed by higher order cognitions, such as fundamental values and value orientations (CitationFulton et al., 1996). The models have been applied across different fields in environmental psychology, especially related to pro-environmental behaviours (see CitationSteg and Vlek, 2009 for an overview).

A specific body of literature has been developed on people’s attitudes towards conservation related issues, such as biodiversity (CitationJohansson and Henningsson, 2011), agrobiodiversity (CitationJunge et al., 2009) or wildlife conservation attitudes. Variables that have been taken into account include values, beliefs and personal norms (CitationJohansson et al., 2013), environmental knowledge (CitationKaltenborn et al., 2016), aesthetic appreciations of biodiversity (CitationQiu et al., 2013) and political and cultural positions (CitationSeippel et al., 2012).

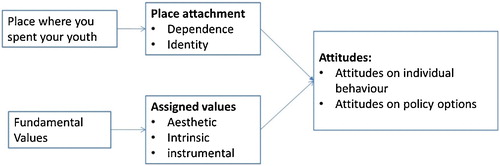

More recently, CitationIves and Kendal, 2013 used a conceptual model combining fundamental values and assigned values to understand attitudes towards peri-urban agricultural land. They argue that assigned values mediate between fundamental values and attitudes and thus need to be added to the ‘cognitive hierarchy’. Assigned values are the values that individuals assign to e.g. natural places such as agricultural landscapes and the services they provide, including the ethical consideration towards protecting such landscapes (CitationLockwood, 1999). In line with the cognitive hierarchy (CitationFulton et al., 1996), the relationship between relatively stable fundamental values and the highly volatile and context-dependent attitudes is not considered a direct relationship, but one that is mediated by assigned values (CitationSeymour et al., 2010). These three variables form the core of our theoretical framework.

We distinguish between three types of assigned values related to agrobiodiversity: intrinsic, aesthetic and instrumental values (CitationChan et al., 2016; CitationBrown, 1984; CitationRaymond et al., 2009). Intrinsic values are about the value of agrobiodiversity for its own sake, including the value of biodiversity (CitationBuijs, 2009). Aesthetic values relate to the assigned aesthetic quality of agrobiodiversity and the landscapes in which it is situated (CitationPlieninger et al., 2013). Instrumental values relate to the value of ‘functional’ agrobiodiversity, such as natural pest control, pollination and other ecosystem services (CitationWratten et al., 2012).

Fundamental values are defined as trans-situational goals and principles that guide human behaviour, which form the basis of pro-conservation attitudes (cf. CitationIves and Kendal, 2013; CitationStern and Dietz, 1994; CitationSteg and Vlek, 2009). Several typologies have been developed to identify the range of fundamental values people may adhere to. One of the most commonly used is the typology by CitationSchwartz (1992). Based on the two dimensions “openness to change versus conservatism” and “self-enhancement versus self-transcendence”, Schwartz distinguishes ten fundamental values, ranging from hedonism to conformity and from security to self-direction (CitationSchwartz (1992)). Previous studies suggest that particularly universalism is related to pro-conservation behaviour (CitationSchultz and Zelezny, 1999; CitationManfredo et al., 2017). Universalism relates to a general concern for the welfare of others in the society at large. It also includes topics such as “unity with nature”, “social justice” and “natural beauty” (CitationSchwartz, 1992).

Attitudes are dispositions towards to a particular object after evaluation; in our case agrobiodiversity (CitationAjzen and Fishbein, 1980). Attitudes can relate both to what people (potentially) do themselves (e.g. support farmers who combine farming with nature conservation by buying their food products) or to their (lack of) support for what others do (e.g. public policies aimed at greening agriculture; CitationLangers and Goossen, 2014).

In addition to the above variables, CitationRaymond et al. (2011) suggest that socio-psychological models for understanding conservation-relevant attitudes and behaviour should also take into consideration people’s emotional connections to places (see also CitationWilliams and Vaske, 2003). This concept of ‘place attachment’ is usually conceptualised as a combination of ‘place identity’ - the symbolic importance of a place as a repository for emotions and relationships that give meaning and purpose to life - and ‘place dependence’ - “the importance of a place in providing features and conditions that support specific goals or desired activity”, such as recreation in the countryside (CitationWilliams and Vaske, 2003: 831).

Finally, a relevant variable is the environment in which respondents had spent their youth (rural or in the city). We hypothesised that people born in the countryside have stronger attachments to agricultural landscapes and its biodiversity and recognise the instrumental values of agrobiodiversity more than people born in cities, who are at a larger distance from the countryside and probably have less affinity with farmers. summarises our conceptual model.

2.2 Data collection method

The data collection was based on an online survey that was conducted Fall 2017. We approached students from four universities and one university of applied sciences. We targeted students from a wide range of programmes, environmental and non-environmental, agricultural and other, in order to include a wide variety of fundamental values. We ended up with mix of students from different programmes and different educational levels (with a majority of university students); see Section 2.2.3. Invitations were sent to students via programme coordinators, programme administrators and teachers, via emails, announcements on Electronic Learning Environments and in general mailings.

2.2.1 Geographical delineation

Our research focuses on the Netherlands, where agrobiodiversity has declined substantially and more than elsewhere in Europe (CitationEEA, 2015). In the Netherlands a variety of public and private governance arrangements for nature conservation in agricultural landscapes is present (CitationRunhaar et al., 2017). This allows analysing students’ attitudes towards who they think is responsible for protecting and enhancing agrobiodiversity.

2.2.2 Survey set-up

Assigned values (i.e. intrinsic, aesthetic and instrumental values of agrobiodiversity) were measured on the basis of four items for each value (see Supplementary material S1). Explorative factor analyses per scale showed that all four items loaded on one single factor. However, reliability analyses showed that one of the items of instrumental values had to be removed in order to reach sufficient reliability. The reliability of the scales for intrinsic and aesthetic values were good (Cronbach’s alpha was α = .78 and .76, respectively) and moderate for the scale used to measure instrumental values (α = .64).

Attitudes were measured by means of items concerning one’s own behaviour (e.g. ‘I am prepared to pay a bit extra for food products that have been produced in ways that respect nature’) and items related to policy measures (e.g. ‘I think stricter preconditions should apply to nature conservation by farmers in return for the income support they receive’). The items were based as much as possible on existing scales. Explorative factor analyses per scale showed that for each scale, the five items loaded on one single factor. The reliability of the two scales were also good (‘attitude-own behaviour’: α = .86; ‘attitude-policy’: α = .88.). The score on the two subscales was calculated using the mean for all items of the subscale. For more details see Supplementary material S1.

Fundamental values were measured using the well-established CitationSchwartz scale, 1992 through presenting personal characteristics to respondents and asking them to indicate on a 7 point scale the extent to which they recognised themselves in the descriptions (varying from 1 = ‘doesn’t seem like me at all’ to 7 = ‘seems extremely like me’; see supplementary material S1).

Place attachment (consisting of the subscales ‘place identity’ and ‘place dependence’; see Section 2) was operationalised using items used by CitationWilliams and Vaske (2003). Again see Supplementary material S1. Explorative factor analyses showed that both four items loaded on one single factor. Reliability for both sub scales was good (place identity: α = .93; place dependence: α = .85). The score on the two subscales was calculated using the mean for all items of the subscale.

The environment in which respondents had spent their youth was measured by means of three items (in urban (cities of over 100,000 inhabitants), peri-urban areas (towns of over 10,000 inhabitants) or in rural areas (villages with less than 10.000 inhabitants)). For analysing mediating effects of this variable, it recoded into urban or peri-urban areas (1) and rural areas (2).

Because of our sample (students), the background variables of age and educational level showed little variance. We also checked for gender, which had no significant relationship with the most important independent variables (place where people spend their youth and fundamental values, except for security). Gender was therefore excluded from further analysis.

The survey was pilot pretested among 39 students of different courses from Wageningen University and Research. Based on the outcomes of reliability and factor analyses, some items were adjusted.

The eventual survey (online) was hosted by Qualtrics. Reminders were sent after about 1 week. After about 6 weeks, all participants received a short summary of the preliminary findings.

2.2.3 Response and representativeness

Through email, newsletters and announcements on Electronic Learning Environments, approximately a bit over 4,000 Dutch students from four different universities and one university of applied sciences were invited to participate (see Supplementary material document S2). In total, 342 students (248 from universities and 94 from a university of applied sciences) participated in the survey, resulting in a relatively low response rate of app. 9%. Although we targeted a wide variety of students from a diversity of programmes (environmental and non-environmental), whether the responding students represent the same diversity is not known to us.

We did not aim for a representative sample of Dutch citizens in general in view of the exploratory nature of our study (see Introduction). We nevertheless compared our sample with the Dutch population in general regarding some of the variables for which data were available (see Supplementary material document S3), showing how the student sample is different from the average Dutch citizen.

2.2.4 Analysis techniques

Correlation, multiple regression and ANOVA analyses were conducted in order to examine how the study variables related to each other. In the multiple regression analyses we used the stepwise procedure, with Pin = .05 and Pout = .10. All analyses were done with SPSS – version 22. In order to examine the mediating effects, we used the procedure as proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986): if an effect of an independent variable disappears (or diminishes) after the addition of another variable in the next step, a (partly) mediating role of that variable can be confirmed.

3 Results

3.1 Values assigned to agrobiodiversity and attitudes towards agrobiodiversity

shows students’ scores on the three assigned values and on attitudes related to their own behaviour and to policies. Intrinsic values of agrobiodiversity resonate most among students (average score 5.1 (the mean), meaning most students “agree a little bit” with statements about this assigned value), followed by aesthetic values (average score 4.9). Instrumental values are commonly not appreciated much. See Supplementary material document S4 for scores per item. When looking at the median instead of the mean, a similar picture arises (with slightly higher valuations). Students do not have outspoken attitudes towards agrobiodiversity conservation, either. They are willing to contribute to conservation to some extent, but seem rather indifferent towards policies aimed at promoting conservation by farmers by means of stricter requirements. Again the median shows a similar picture as the mean. Zooming in on the items by means of which we measured attitudes, a remarkable finding is that students do indicate to be willing to pay more for food that has been produced in ‘nature friendly’ ways (score 5.17 equalling “agree a little bit”). This is not completely consistent with their willingness to buy organic products however (see Supplementary material document S5).

Table 1 Students’ scores on assigned values and attitudes.

3.2 Factors affecting attitudes

Respondents’ attitudes strongly and significantly relate to place dependence and to assigned values (R2Adj = .361). When we look at respondents’ attitudes towards policy measures (see ), we conclude that policy attitudes are best explained by assigned values. Intrinsic and aesthetic values are positively related to attitudes. Although intrinsic values have the strongest single correlation with attitudes (model 1), aesthetic values have the strongest contribution to attitudes in the final regression model (model 4). Contrary to our theoretical framework, instrumental values relate negatively to attitudes on policy measure. This negative relationship is found both with students who grew up in the countryside as well as with students who grew up in the city. In addition to assigned values, also place dependence significantly relates to attitudes on policy measures, albeit in a negative manner. In other words, students who appreciate the intrinsic or aesthetic value of agrobiodiversity support policy measures that promote agrobiodiversity significantly more than students who appreciate instrumental values of agrobiodiversity and/or who value the countryside for leisure activities (i.e. place dependence).

Table 2 Multiple regression with attitudes on policy measures as dependent variable and assigned values and place attachments as independent variables.

Looking at attitudes related to students’ own behaviour, we see a very similar pattern, with an even higher explanatory power (R2Adj = .579). The only noticeable difference is that instrumental values do not contribute significantly to the understanding these of attitudes (see ).

Table 3 Multiple regression with attitudes towards students’ own behaviour as independent variable explained by assigned values and place attachments as dependent variables.

3.3 Factors affecting assigned values and place attachment

We hypothesised that assigned values can be explained through fundamental values, particularly the value of universalism. Multiple regression analysis shows that all three assigned values strongly relate to the value of universalism; intrinsic and aesthetic values positively, while instrumental value relates negatively with universalism (see Supplementary material S7-2). In addition, the value of security relates positively to instrumental value, and the value of self-direction relates positively to aesthetic value.

Place attachment in turn is related to the place where people were born. Students who grew in rural areas show a higher place identity and place dependence than students who grew up in peri-urban areas, who in turn show a higher place identity and dependence than people who grew up in urban areas. Tukey’s b shows that both place dependence and place identity significant differ between each subset. See Supplementary material S7-1.

As a final step, we tested whether assigned values and place attachment indeed mediate between our independent variables and attitudes. Mediational analyses using stepwise regression confirms that the relationship between the independent variables and dependent variables (attitudes) are indeed mediated by assigned values and place attachment: the influence of fundamental values on attitudes is mediated by assigned values, and the influence of the place where people grew up on attitudes is mediated by place attachment (most notable place dependence). (See Supplementary Material S7-1 and S6-2 for detailed analyses). Nevertheless, the direct relationship between the two independent variables and attitudes remains significant, although much weaker than the explanatory power of assigned values and place attachment on both types of attitudes. For example, the relationship between place where people grew up and attitudes towards policy diminishes from β=-.244 to β=-.144 when place dependence (β=-.220) is added to the equation (Supplementary Material S7-1). This confirms the hypothesis of our theoretical framework () on the mediating role of assigned values and place attachment in understanding students’ attitudes.

4 Discussion

4.1 Reflections on conceptual framework and results

With this study we aimed to uncover the mechanisms between valuations of agrobiodiversity and factors that affect these valuations, as well as how these valuations, whether or not mediated by other factors, influence people’s willingness to contribute to the enhancement of agrobiodiversity, either actively or passively (e.g. by supporting policies). Data provided by our student sample yielded some interesting results, that are not representative of the Dutch population in general in terms of how much citizens value agrobiodiversity. The data nevertheless provide some first insights into the above mechanisms that explain valuations and attitudes. We hypothesise that these mechanisms are representative for other groups of Dutch citizens.

The importance of assigned values to understand attitudes towards agrobiodiversity is clearly supported by the outcomes. The three types of values of agrobiodiversity that we identified in this paper – intrinsic, aesthetic and instrumental – all correlate to attitudes. As theoretically hypothesised, intrinsic and aesthetic values correlate strongly with attitudes towards policies that prescribe stricter conservation requirements to farmers. In addition, these assigned values mediate between fundamental values and attitudes. However, instrumental values, described as the functional benefits of agrobiodiversity for farmers and agricultural productivity, correlate negatively to these attitudes (). One possible explanation for this outcome contrary to our theory is that it is in farmers’ own interest to employ ‘functional’ agrobiodiversity and that they thus do not need to be stimulated to take care of such agrobiodiversity (either by public policies or by consumers). The fundamental value of universalism correlates negatively with instrumental values. Universalism refers to a general concern for the welfare of others, including nature (see Section 2). Apparently an anthropocentric approach to agrobiodiversity (i.e. instrumental) logically does not fit in this fundamental value.

In addition to assigned values, also place attachment correlates to attitudes, although much weaker than the assigned values. Moreover place attachment, and most notably place dependence had a negative relationship with attitudes. Students who grew up in the countryside feel more attached to the countryside and its farmers, and have lower support for policies that require farmers to contribute to nature conservation. A possible explanation is that this finding is related to closeness to farmers, but this requires further research.

4.2 Methodological limitations

There are several limitations to our study. First, because of the relatively low response rate, we cannot guarantee that our sample is representative of all Dutch students at institutes for higher education in terms of valuations of agrobiodiversity. Students who are not interested in agrobiodiversity are probably under-represented. We observe an over-representation of students who grew up in rural areas; we imagine these students are more interested in agrobiodiversity than students who grew up in (peri)urban settings. Second, the cross-sectional data did not allow us to draw firm conclusions regarding causal relationships. The mechanisms that we explored and that were discussed above therefore need further testing. Future studies could use measurements over time to detect causes and effects. Third, whereas most scales we used had a good reliability, the scale used for measuring instrumental values had a moderate reliability. Future research should include other items to measure this variable (e.g. insurance as an additional form of instrumental biodiversity; CitationFinger and Buchmann, 2015).

4.3 Practical implications

We conclude that among students who participated in our survey, there is a low to modest appreciation of agrobiodiversity, a low to modest support for stricter conservation requirements for farmers (e.g. coupled with the income support from the EU Common Agricultural Policy) and a low to modest willingness to contribute to the conservation of agrobiodiversity themselves, except for paying somewhat extra for nature-friendly food. These findings are problematic in terms of support for voluntary nature conservation by farmers and for public and private policies that promote nature conservation.

Institutes for higher education can contribute to students’ awareness of the need for more biodiverse agriculture by incorporating the subject in courses and curricula. They can create learning situations in which students can develop capabilities to think critically, ethically, and creatively about environmental issues and make informed decisions about how to cope with environmental problems (CitationWals et al., 2014). The strong correlation between aesthetic values and intrinsic values and attitudes suggests possibilities for attitude change towards increased support for agrobiodiversity, not only for institutes for higher education but also for governments and NGOs. Relating measures that farmers can implement to these values, and showing the results on the aesthetic quality and its contribution to biodiversity may increase students’ support for public and private policies that promote agrobiodiversity. The aesthetic dimension of biodiversity, especially through flowers, smells and sounds, is usually highly appreciated by people (CitationStilma et al., 2009). This opens up opportunities for a strategy of “Show, don’t tell”. A factor that was not taken into account however is the baseline information that students have about agrobiodiversity and their awareness of both the decline in agrobiodiversity and why this matters (cf. CitationRunhaar, 2017). Although a simple ‘knowledge deficit’ model is too a simplistic view on people’s attitudes on biodiversity conservation attitudes (CitationBuijs et al., 2008), knowledge and understanding of biodiversity has been shown to influence people’ views and attitudes towards biodiversity protection (CitationKaltenborn et al., 2016). Moreover, a recent survey commissioned by WWF Netherlands showed that 91% of the 1,005 respondents did not know that food production globally is the main cause of loss of biodiversity and that among young adults (18–24 years) 10% even stated not to know that our current food production system harms biodiversity (CitationWNF, 2018).

4.4 Conclusions

In this paper we addressed the following research questions:

| 1 | How do students value agrobiodiversity and what factors account for these valuations? | ||||

| 2 | What is the willingness of students to contribute to the enhancement of agrobiodiversity, and how can this be explained? | ||||

Regarding the first question, we found that students appreciate intrinsic and aesthetic values of agrobiodiversity to some extent. Instrumental values generally are not considered important. All three assigned values strongly relate to the value of universalism; intrinsic and aesthetic values positively, while instrumental value relates negatively with universalism ().

Regarding the second question, we found that students are willing to contribute to agrobiodiversity conservation to some extent, but seem rather indifferent towards policies aimed at promoting conservation by farmers by means of stricter requirements. Students however do indicate to be willing to pay more for food that has been produced in ‘nature friendly’ ways. Students’ attitudes strongly and significantly relate to place attachment and assigned values. Policy attitudes are best explained by assigned values. Intrinsic and aesthetic values are positively related to attitudes, instrumental values are negatively related to attitudes. Students who appreciate the intrinsic or aesthetic value of agrobiodiversity support policy measures that promote agrobiodiversity significantly more than students who appreciate instrumental values of agrobiodiversity. Looking at attitudes related to pro-nature behaviour, we see a very similar pattern.

We recommend follow-up research among a more representative sample of Dutch citizens, with the aim of both assessing valuations of agrobiodiversity by Dutch citizens in general and whether and how these valuations can be enhanced by the provision of information about the intrinsic and aesthetic values of agrobiodiversity. In view of the ongoing decline in agrobiodiversity, in the Netherlands and elsewhere, it is important that awareness and a sense of urgency is created, not only among farmers, representatives of the agri-food industry, governments and NGOs, but particularly also among citizens, who at present do not seem to be very actively involved in the societal debate about agrobiodiversity.

tjls_a_12128549_sm0001.docx

Download MS Word (62 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Machiel Bouwmans (HU University of Applied Sciences Utrecht) and Simon Vink and David Kleijn (Wageningen University and Research) for their input and feedback on the research design.

References

- I.AjzenAttitudes, Personality and Behaviour2005Open University PressMaidenhead

- I.AjzenM.FishbeinUnderstanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour1980Prentice-HallEnglewood Cliffs

- A.BernuésT.Rodríguez-OrtegaR.Ripoll-BoschF.AlfnesSocio-cultural and economic valuation of ecosystem services provided by Mediterranean mountain agroecosystemsPLoS One972014 e10247

- J.F.F.BosA.L.SmitJ.J.SchröderIs agricultural intensification in The Netherlands running up to its limits?Njas - Wageningen J. Life Sci.6620136573

- T.C.BrownThe concept of value in resource allocationLand Econ.601984231246

- A.E.BuijsLay people’s images of nature: frameworks of values, beliefs and value orientationsSoc. Nat. Resour.222009417432

- A.E.BuijsA.FischerD.RinkJ.C.YoungLooking beyond superficial knowledge gaps: understanding public representations of biodiversityInt. J. Biodivers. Sci. Manag.420086580

- K.M.A.ChanP.BalvaneraK.BenessaiahN.ChapmanS.DíazE.Goméz-BaggethunR.GouldWhy protect nature? Rethinking values and the environmentProc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.113201614621465

- EEAState of Nature in EU. Results From Reporting Under the Nature Directives 2007-2012. EEA Technical Report no2/20152015European Environment Agency.Luxembourg

- L.EgliC.MeyerC.ScherberH.KreftT.TscharntkeWinners and losers of national and global efforts to reconcile agricultural intensification and biodiversity conservationGlob. Chang. Biol.245201822122228

- R.FingerN.BuchmannAn ecological economic assessment of risk-reducing effects of species diversity in managed grasslandsEcol. Econ.11020158997

- D.C.FultonM.J.ManfredoJ.LipscombWildlife value orientations: a conceptual and measurement approachHum. Dimens. Wildl.119962447

- C.A.HallmannM.SorgE.JongejansH.SiepelN.HoflandH.SchwanW.StenmansA.MüllerH.SumserT.HörrenD.GoulsonH.de KroonMore than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areasPLoS One12102017 e0185809

- C.D.IvesD.KendalValues and attitudes of the urban public towards peri-urban agricultural landLand Use Policy3420138090

- M.JohanssonM.HenningssonSocial-psychological factors in public support for local biodiversity conservationSoc. Nat. Resour.242011717733

- M.JohanssonJ.RahmM.GyllinLandowners’ participation in biodiversity conservation examined through the Value-Belief-Norm TheoryLandsc. Res.382013295311

- X.JungeK.A.JacotA.BosshardP.Lindemann-MatthiesSwiss people’s attitudes towards field margins for biodiversity conservationJ. Nat. Conserv.172009150159

- B.P.KaltenbornV.GundersenE.StangeD.HagenK.SkogenPublic perceptions of biodiversity in Norway: From recognition to stewardship?Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr.7020165461

- F.LangersM.GoossenBeleving Van De Weidevogelproblematiek in Nederland (available from2014WageningenAlterrahttp://arxiv:/www.wur.nl/nl/Publicatie-details.htm?publicationId=publication-way-343439363732)

- M.LockwoodHumans valuing nature: synthesising insights from philosophy, psychology and economicsEnviron. Values81999381

- P.LoweP.FeindtH.VihinenIntroduction: greening the countryside? Changing frameworks of EU agricultural policyPublic Adm.8822010287295

- M.J.ManfredoJ.T.BruskotterT.L.TeelD.FultonS.H.SchwartzR.ArlinghausS.OishiA.K.UskulK.RedfordS.KitayamaL.SullivanWhy social values cannot be changed for the sake of conservationConserv. Biol.312017772780

- J.OllertonH.ErenlerM.EdwardsR.CrockettExtinctions of aculeate pollinators in Britain and the role of large-scale agricultural changesScience3466215201413601362

- P.OpdamI.ConinxA.DewulfFraming ecosystem services: Affecting behaviour of actors in collaborative landscape planning?Land Use Policy462015223231

- A.PaçoT.LavradorEnvironmental knowledge and attitudes and behaviours towards energy consumptionJ. Environ. Manage.1972017384392

- S.PascucciD.DentoniA.LombardiL.CembaloSharing values or sharing costs? Understanding consumer participation in alternative food networksNjas - Wageningen J. Life Sci.7820164760

- R.Perry-HillL.S.ProkopyComparing different types of rural landowners: implications for conservation practice adoptionJ. Soil Water Conserv.6932014266278

- T.PlieningerS.DijksE.Oteros-RozasC.BielingAssessing, mapping, and quantifying cultural ecosystem services at community levelLand Use Policy332013118129

- J.PrettyAgricultural sustainability: concepts, principles and evidencePhilos. Trans. Biol. Sci.36314912008447465

- L.QiuS.LindbergA.B.NielsenIs biodiversity attractive? On-site perception of recreational and biodiversity values in urban green spaceLandsc. Urban Plan.1192013136146

- C.M.RaymondB.A.BryanD.H.MacDonaldA.CastS.StrathearnA.GrandgirardT.KalivasMapping community values for natural capital and ecosystem servicesEcol. Econ.68200913011315

- C.M.RaymondG.BrownG.M.RobinsonThe influence of place attachment, and moral and normative concerns on the conservation of native vegetation: a test of two behavioural modelsJ. Environ. Psychol.312011323335

- P.RikhardssonC.HolmThe effect of environmental information on investment allocation decisions - an experimental studyBus. Strategy Environ.1762008 382-39

- D.RoepJ.D.Van der PloegJ.S.C.WiskerkeManaging technical-institutional design processes: some strategic lessons from environmental co-operatives in the NetherlandsNjas - Wageningen J. Life Sci.511–22003195217

- G.E.Roesch-McNallyA.D.BascheJ.G.ArbuckleJ.C.TyndallF.E.MiguezT.BowmanR.ClayThe trouble with cover crops: farmers’ experiences with overcoming barriers to adoptionRenew. Agric. Food Syst.2017 (published online)

- H.A.C.RunhaarGoverning the transformation towards’ nature-inclusive’ agriculture: insights from the NetherlandsInt. J. Agric. Sustain.1542017340349

- H.A.C.RunhaarMelmanThCPF.G.BoonstraJ.W.ErismanL.G.HorlingsG.R.de SnooTermeerCJAMM.J.WassenJ.WesterinkB.J.M.ArtsPromoting nature conservation by Dutch farmers: a governance perspectiveInt. J. Agric. Sustain.1532017264281

- H.RunhaarN.PolmanM.Dijkshoorn-DekkerSelf-initiated nature conservation by farmers: an analysis of Dutch farmingInt. J. Agric. Sustain.1662018486497

- H.RunhaarP.RunhaarM.BouwmansS.VinkA.BuijsD.KleijnThe power of argument. Enhancing citizen’s valuation of and attitude towards agricultural biodiversityInt. J. Agric. Sustain.201910.1080/14735903.2019.1619966 (published online)

- F.J.SandersonM.KucharzM.JobdaP.F.DonaldImpacts of agricultural intensification and abandonment on farmland birds in Poland following EU accessionAgric. Ecosyst. Environ.16820131624

- P.W.SchultzL.ZeleznyValues as predictors of environmental attitudes: evidence for consistency across 14 countriesJ. Environ. Psychol.191999255265

- S.H.SchwartzUniversals in the content and structure of values: theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countriesAdv. Exp. Soc. Psychol.251992165

- ØSeippelB.de MarchiP.A.GarnåsjordetI.AslakenPublic opinions on biological diversity in Norway: Politics, science, or culture?Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr.662012290299

- E.SeymourA.CurtisD.PannellC.AllanA.RobertsUnderstanding the role of assigned values in natural resource managementAustralas. J. Environ. Manag.172010142153

- L.StegC.VlekEncouraging pro-environmental behaviour: an integrative review and research agendaJ. Environ. Psychol.292009309317

- P.C.SternToward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behaviorJ. Soc. Issues562000407424

- P.C.SternT.DietzThe value basis of environmental concernJ. Soc. Issues5019946584

- E.S.C.StilmaA.B.SmitA.B.Geerling-EiffP.C.StruikB.VosmanH.KorevaarPerception of biodiversity in arable production systems in the NetherlandsNjas - Wageningen J. Life Sci.562009391404

- A.J.TanentzapA.LambS.WalkerA.FarmerResolving conflicts between agriculture and the natural environmentPLoS Biol.1392015 e1002242

- T.TscharntkeA.M.KleinA.KruessI.Steffan-DewenterC.ThiesLandscape perspectives on agricultural intensification and biodiversity–ecosystem service managementEcol. Lett.882005857874

- A.E.WalsM.BrodyJ.DillonR.B.StevensonConvergence between science and environmental educationScience34461842014583584

- J.WesterinkR.JongeneelN.PolmanK.PragerJ.FranksP.DuprazE.MettepenningenCollaborative governance arrangements to deliver spatially coordinated agri-environmental managementLand Use Policy692017176192

- D.R.WilliamsJ.J.VaskeThe measurement of place attachment: validity and generalizability of a psychometric approachFor. Sci.492003830840

- WNFVoedselproductie Grootste Oorzaak Natuurverlies, Maar Nederlander Realiseert Zich Dat Niet2018http://https://www.wnf.nl/nieuws/bericht/voedselproductie-grootste-oorzaak-natuurverlies-maar-nederlander-realiseert-zich-dat-niet.htm

- World Bank (n.d.), Agricultural land (% of land area), available from http://https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ag.lnd.agri.zs.

- S.D.WrattenM.GillespieA.DecourtyeE.MaderN.DesneuxPollinator habitat enhancement: benefits to other ecosystem servicesAgric. Ecosyst. Environ.1592012112122

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:http://https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2019.100303.