Highlights

| • | The OIS concept can be used to analyse multi-actor co-innovation partnerships. | ||||

| • | Co-innovation partnerships in agriculture and forestry occur in many forms. | ||||

| • | Often based on existing networks, they mobilise complementary forms of knowledge. | ||||

| • | ‘Outreach’ practices to foster dialogue with a ‘larger periphery’ are commonly used. | ||||

| • | The ‘enabling environment’ affects the performance of the co-innovation partnership. | ||||

Abstract

Innovation rests not only on discovery but also on cooperation and interactive learning. In agriculture, forestry and related sectors, multi-actor partnerships for ‘co-innovation’ occur in many forms, from international projects to informal ‘actor configurations’. Common attributes are that they include actors with ‘complementary forms of knowledge’ who collaborate in an innovation process, engage with a ‘larger periphery’ of stakeholders in the Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation System (AKIS) and are shaped by institutions. Using desk research and interviews, we reviewed, according to the Organisational Innovation Systems framework, the performance of 200 co-innovation partnerships from across Europe, selected for their involvement of various actors ‘all along the process’. Many of the reviewed partnerships were composed of actors that had previously worked together and most interviewees believed that no relevant actors had been excluded. In almost all cases, project targets and objectives were co-designed to a great or some extent, and the mechanisms applied to foster knowledge sharing between partners were considered to be very effective. Great importance was attached to communication beyond the partnership, not simply for dissemination but also for dialogue, and most interviewees evaluated the communication/outreach performance of their partnership very highly. Most partnerships received external funding, most did not use innovation brokers during the proposal writing process and two thirds had access to information they needed. We discuss the implications of these findings and question whether the AKIS concept as currently interpreted by many policy makers can adequately account for the regional differences encountered by co-innovation partnerships across Europe.

1 Introduction

The Horizon 2020 (H2020) funded multi-actor project LIAISON (Better Rural Innovation: Linking Actors, Instruments and Policies through Networks) is working to understand the co-innovation concept from the point of view of various actors and stakeholders represented at different levels of the process. The focus is on multi-actor co-innovation activities involving farmers and foresters (and not in actions that support innovation transfer or training in innovation and/or those that do not include practitioners in the innovation process). Hence, process and experience of the co-innovation partnership are of more interest to LIAISON than the results of these activities. The outputs of the project are expected to make a significant and meaningful contribution to optimising co-innovation approaches and the delivery of European Union (EU) policies to speed up innovation in agriculture, forestry and related sectors.

In this paper, we present the results of a review of 200 co-innovation partnerships from across Europe. The purpose of the research was to identify the factors that contribute most to the ‘success’ of the innovation process, and not the partnership activities more generally or the innovations that arise from them. Co-innovation, as defined by CitationChesbrough and Bogers (2014), involves two (or more) partners that purposively manage mutual knowledge flows across their organisational boundaries through joint invention and commercialisation activities. It can be delivered according to several different models which engage actors in dynamic multi-stakeholder innovation systems or in iterative learning for change processes (CitationIngram et al., 2020). Thus, the reviewed examples included ‘projects’ (i.e. single, non-divisible interventions with a fixed time schedules and dedicated budgets, as defined by CitationO’Neill et al., 2012) and non-project activities (i.e. other ‘actor configurations’ listed by CitationKnierim et al., 2015, such as networks, platforms, clusters, alliances or partnerships).

The innovation system construct has been developed to capture and understand the relationships between producers, users, governments and institutions (CitationVan Lancker et al., 2016). Well-documented developments in innovation systems thinking (CitationRivera et al., 2006; CitationKlerkx et al., 2012) have led to the recognition that, alongside the traditional process of ‘knowledge transfer’ (with research as the source of knowledge, extension and education as knowledge and information channels, and farmers as passive recipients of knowledge), innovation can be ‘co-produced’ through interactions between actors with complementary forms of knowledge. In this process, problems are identified and potential solutions co-created through a collective learning process involving knowledge sharing (CitationNederlof et al., 2011; CitationDogliotti et al., 2014).

In modern innovation theory, therefore, innovation rests not only on discovery but also on cooperation and interactive learning between actors (such as farmers, researchers and intermediaries) (CitationLundvall, 2016). Innovations are iteratively enacted through networks of social relations, rather than through singular events by isolated individuals or organisations (CitationCoenen and Díaz López, 2010). But learning need not necessarily imply discovery of new technical or scientific principles and can equally be based on activities which recombine or adapt existing knowledge (CitationSmith, 2000). Linked with this acceptance that many innovations occur without formal scientific knowledge is the wider recognition of the role of tacit (as opposed to formal, codified or explicit) knowledge and expertise in innovation (CitationLowe et al., 2019). In line with this, the term ‘knowledge sharing’, which implies multilateral flows of knowledge, has tended to replace ‘knowledge transfer’, a term associated with the ‘linear’ model of communication (often from researchers to practitioners) (CitationSutherland et al., 2017).

Co-innovation can be analysed at several levels (CitationVan Lancker et al., 2016). At the macro (sectoral) level, the Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation System (AKIS) concept is now widely used in European policy discourse (CitationFaure et al., 2019). Models of the AKIS normally depict the actors who use and produce knowledge and innovation for agriculture and interrelated fields, the ways in which they are organised and the knowledge flows between them. By convention, ‘practitioners’, such as farmers and foresters, are placed at the centre of the model (e.g. CitationEU SCAR, 2013, p.18). The AKIS can be likened to a ‘space’ in which numerous and diverse multi-actor partnerships operate (CitationFieldsend et al., forthcoming). However, although the AKIS concept goes some way to specifying the conditions necessary for co-innovation, it does not address the innovation process itself.

In lieu of the AKIS, many international organisations have adopted the Agricultural Innovation System (AIS) concept for macro-level analysis of co-innovation (CitationSulaiman, 2015). The AIS can be defined as a network of organisations, enterprises, and individuals focused on bringing new products, new processes, and new forms of organisation into economic use, together with the institutions and policies that affect the way different agents interact, share, access, exchange and use knowledge (CitationLeeuwis and van der Ban, 2004).

Several methodological tools have been used at the micro level to analyse partnership working and co-innovation (CitationWielinga and Geerling-Eiff, 2009). Network Analysis is a model that enables the network’s involvement in a specific initiative to be understood and its position to be explored. The Innovation Spiral is widely used to examine how an idea develops into an innovation. The innovation process can be examined according to the Circle of Coherence model, which focuses on connections (interaction) in the network. Such tools typically focus on one innovation project phase or innovation management concept. By contrast, the Organisational Innovation System (OIS) approach brings together important insights from the innovation systems, open innovation and other related fields into a single guiding concept (CitationVan Lancker et al., 2016). OIS are defined as “innovation network[s] of diverse actors, collaborating with a focal innovating organization in an innovation process, to generate, develop and commercialize a new concept, shaped by institutions” (ibid., p.42). The authors argue that this framework for analysis can be used to study and compare OIS, potentially leading to valuable insights to increase innovation efficiency and efficacy of innovation organisations. In turn, improved innovation performance at the organisational level will have a direct positive effect on the performance of related higher system levels.

An OIS has four main structural components. The diverse actors of the OIS are those groups or individuals who have a stake in the innovation process. CitationLamprinopoulou et al. (2014) defined four broad categories of actors in the AKIS: research, direct demand/enterprise, indirect demand and intermediary. Co-innovation is an evolutionary and non-linear learning process, which requires intense communication and collaboration between different actors in order to take into account its multi-dimensional aspects. CitationVan Lancker et al. (2016) argue that the innovation process within the OIS has three main phases, the innovative idea, which is developed into an invention, which in turn is followed by commercialisation. CitationBogers (2011) suggest that the innovation network consists of two layers. The first is a smaller, ‘core group’ of actors with whom the organisation works in close collaboration, sharing knowledge openly. The second layer consists of a ‘larger periphery’ of diverse stakeholders that are less involved, though they participate in the innovation process, with whom not all information is shared. These stakeholders help create legitimacy and support for the innovation (CitationTurner et al., 2016). Finally, the institutions that regulate the co-innovation partnership are the legal (e.g. regulation and law) and customarily institutions (e.g. culture and values) that together constitute the ‘rules of the game’ or the ‘codes of conduct’ (CitationKlein Woolthuis et al., 2005). There is a clear distinction between institutions and organisations: the former correspond to rules and the latter are players (ibid.).

We used the OIS concept to analyse the results of our review of 200 co-innovation partnerships, with the ‘multi-actor partnership’ placed at the core of an OIS. Frequently, especially but not only in the case of ‘projects’, a partnership includes a coordinator (organisation) which is analogous to the ‘focal innovating organisation’ of the OIS as defined by CitationVan Lancker et al. (2016). In line with CitationBogers (2011), we distinguished between a ‘core group’ of actors that formed the partnership and a ‘larger periphery’ of (engaged) stakeholders. Most of the reviewed partnerships were clearly ‘multi-actor’, in that constituent actors had different ‘labels’ sensu CitationLamprinopoulou et al. (2014), such as farmer, researcher or advisor. These included examples of knowledge sharing between the (mainly private sector) actors in the value chain, including input suppliers and food processors, since this is where much of the on-farm technology or food retail innovation takes place (CitationSwinnen and Kuijpers, 2019). But we also assessed some peer-to-peer networks of farmers and foresters since knowledge sharing between farmers (CitationKilpatrick and Johns, 2007; CitationOreszczyn et al., 2010) and foresters (CitationHamunen et al., 2015) themselves can also foster co-innovation. Indeed, CitationKoutsouris et al. (2017) noted that farmers tend to be most influenced by proof of successful farming methods by their peers, and it should be recalled that the critical criterion for a genuine co-innovation partnership is in fact the inclusion of ‘complementary forms of knowledge’.

The novelty of our work lies in the fact that we applied a common OIS-derived assessment methodology to a substantial number of co-innovation partnerships in agriculture, forestry and related sectors from across Europe. Notwithstanding the diversity of our reviewed examples, in all instances the innovation process included “specific actions on communication, knowledge exchange and the involvement of various actors all along the project” (EIP-AGRI, 2013, p.4, our emphasis). In other words, actors within or outside the partnership with ‘complementary forms of knowledge’ participated in the ‘idea development’, ‘invention’ and ‘commercialisation’ (dissemination) phases of the innovation process.

2 Methodology

Our unit of selection was the ‘multi-actor co-innovation partnership’, each of which is considered to be an OIS. We applied five ‘key tests’ when shortlisting examples for review: (a) direct relevance of the topic of the co-innovation activity to agriculture, forestry or related sectors; (b) demonstration of a multi-actor partnership; (c) a substantial involvement of practitioners in the innovation process ‘all along the project’, preferably as part of the consortium or partnership; (d) a clear intention to innovate; and (e) the quality of the activity description. The latter ‘test’ was to assess whether the activity was likely to be ‘insightful’ in terms of yielding useful information. These ‘key tests’ were formulated on the basis of earlier, conceptual work of the LIAISON project.

The 200 examples for review were derived primarily from two sources.

Firstly, 1357 candidate projects were identified from a compiled database of several thousand such examples drawn from official EU databases (). Every consulted database was uniquely structured and, of necessity, different key words were used to shortlist projects from each (CitationFieldsend et al., 2019). To achieve consistency to the extent possible, most of this work was undertaken by just two people. Under close supervision, the 17 LIAISON partners were then asked to nominate candidate non-EU funded activities. These took various forms, from complex government-funded projects through to ad hoc initiatives, and operate(d) at the European, national, regional and/or local levels.

Table 1 European Union databases from which the projects for review were sourced.

Secondly, recognising that the above approach would not adequately sample ‘actor configurations’ beyond ‘projects’, a second source was an EU-wide Rural Innovation Contest (EURIC) held by the LIAISON project which was aimed at identifying less formal examples of co-innovation. Between 15 January and 15 March 2019, co-innovation partnerships could submit an entry to the LIAISON website, emphasising what was particularly ‘inspirational’ about their co-innovation activity. In order to maximise the impact of the EURIC, the call for entries was widely publicised by the consortium partners through many channels, including the farming, rural, policy and local media, within EU Member States and several neighbouring countries. The EURIC attracted 175 eligible entries which are described on the LIAISON website.Footnote1 These were dubbed ‘under the radar’ activities as many of them were not included in published databases and/or not known to EU and/or national policy makers.

A purposive stratified sampling frame was applied to finalise the shortlist of 200 examples for review. This was to ensure a diversity of multi-actor co-innovation activities in the sample. The selection reflected the importance of the EIP-AGRI in the current EU policy framework, but also included activities supported by other relevant EU policy instruments (such as Interreg, LEADER and LIFE). We sought to maximise geographical diversity (including Norway and Switzerland) among the selected non-EU wide projects and to ensure an adequate representation of non-project activities such as those sourced through the EURIC. In the event, 87 projects funded in the frame of EIP-AGRI, 74 other projects and 39 non-project activities were shortlisted (). Although around three quarters of the sample were agriculture related, five per cent concerned forestry and just over 20 per cent dealt with related topics.

Table 2 Overview of the 200 reviewed co-innovation partnerships.

Each of the 17 LIAISON partners reviewed around 12 partnerships in the period May-July 2019. Each review consisted of three phases. Firstly, desk research using published information (such as project websites) was carried out and the results subsequently checked with the interviewees. Secondly, a ‘one telephone call’ semi-structured interview of about 1.5 h duration was carried out with a key informant. Of the interviewees, 128 described themselves as being ‘coordinator’, ‘project leader’ or in a comparable role, a further 21 occupied evidently senior positions such as ‘managing director’ and the remaining 51 were ‘project partners’ or similar. Among them, 82 were female, 115 were male and three were not defined. Many of these interviews were in fact conducted face-to-face, although other formats such as Skype were used in some instances. The interview concluded with a short self-evaluation by the interviewee of the overall performance of the co-innovation activity. Thirdly, a post-interview reflection by the LIAISON partner was intended to get some first insights into the factors they thought were keys to the success of the activity or causes of failure or were barriers to efficient implementation. This methodology ensured that a large amount of data was gathered very efficiently from 200 co-innovation partnerships.

In order to minimise any effects of interviewer bias on our results, each LIAISON partner was allocated a range of partnership types. Data consistency was aided by a detailed, illustrated ‘how to’ guide for interviewers and a standard data gathering template. In line with the OIS concept, the interview was structured to explore how the partnership was formed (the ‘diverse actors’), cooperation within it (the ‘innovation process’), communication with stakeholders outside the partnership, including but not only dissemination (the innovation network), and the roles of the institutions. When feasible, multiple choice answers were provided for a question (such as, for example, ‘Country of residence of the coordinator’). In other instances, text was the only appropriate format for gathering the required insights, for example for questions concerning ‘attitudes’ and ‘group dynamics’. To facilitate subsequent analysis, strict maximum character counts for each question were built into the template, thereby forcing interviewers to be disciplined in the way they summarised the information. The focus was on the real experiences of projects and partnerships rather than what they “might” (but probably will not) do at some point in the future. The data gathering template was tested in practice before being finalised and shared with the LIAISON partners.

Most prospective interviewees were pleased to take part in the research, although in some instances the preferred contacts could not be reached or declined to be interviewed. Since the research was to be conducted by LIAISON colleagues from 15 countries, the methodology was designed to maximise consistency of the results. Nonetheless, the cultural and organisational backgrounds of the survey participants may have influenced the way certain concepts (especially specialist technical terms and jargon) were translated and interpreted, and interviewers occasionally found it challenging to summarise the interviewees’ answers within the designated word limits.

The results were collated into a single spreadsheet for analysis. One person was then responsible for analysing both the quantitative and qualitative data pertaining to each of the four main structural components of the OIS. Those responsible for collating and analysing the data referred to the interviewers for clarifications whenever necessary.

We present quantitative and qualitative data, including quotes from interviewees where these illustrate the points being made. To ensure confidentiality, no projects are referred to by name but only occasionally by their general description, for example “an OG from Germany”. Any quotes from interviewees are not attributed to individuals.

3 Results

Our results describe the four main structural components of an OIS, i.e. the diverse actors, the innovation process, the innovation network and the institutions.

3.1 The diverse actors

Here we explore how the ‘core group’ of actors came together to form the partnership, the allocation of roles and whether any relevant actors were excluded. Between them, the 200 reviewed examples involved an extremely broad range of actors including farmers, foresters and their representative organisations, advisors, other supply chain actors, other businesses (such as IT companies), public bodies, researchers and academics.

Existing and often informal networks were an important factor in actor recruitment in many, if not most, partnerships. In an H2020 Research and Innovation Action (RIA), “Most partners had already worked together, and some others were then incorporated with concrete expertise required”. However, selection of partners sometimes happened in an almost casual way. In an Italian private sector funded project, for example, “Partners were not selected. Indeed, they got involved in the project in a casual way”.

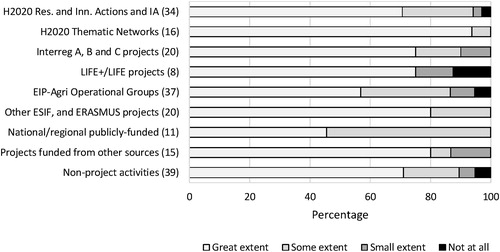

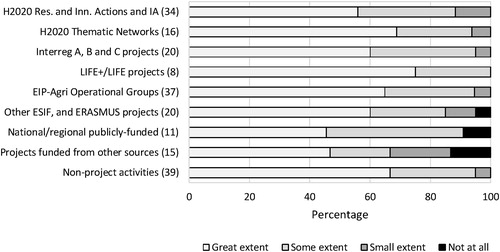

Among the interviewees, 153 said that their partnerships had connections to other projects or initiatives, while 47 did not (). Many interviewees stated that the current activity was developed from an earlier one and that in this respect there was a link to the previous collaboration. Many H2020 projects had links to other H2020 projects. One H2020 Thematic Network (TN) interviewee said that: “80 per cent of the partners are also partners in another H2020 project”. Naturally, most partnerships had connections to other activities on similar themes. For instance, an informant from a project about climate change and soil management said that there were links to “All kinds of projects according to climate change, soil management”. In contrast to international EU projects (i.e. H2020, Interreg and LIFE), 14 of the 37 Operational Groups (OGs) appear to have no links with other partnerships.

Fig. 1 Percentage of partnerships with a link to other projects or initiatives, by type.

Note: in all Figures, the numbers of each partnership type are shown in parentheses.

Source: own data.

While existing networks were one of the central factors for the recruitment of partners, relevant skills of the potential participant were also frequently cited as a key selection factor when assembling a partnership. An interviewee from an Austrian OG stated: “Research partners bring in theoretical background. Farmers bring practical knowledge”. On other occasions, partners were selected based on common interests and common challenges shared by a variety of people and organisations. A popular way to find partners with shared interests, skills or problems was to contact NGOs and organisations representing the interests of certain groups, such as farmers’ unions or associations. Once partners had been selected, the most common factor determining the allocation of roles was skills. In the case of a Belgian OG: “The research institutes had to make a literature study, they also prepared and elaborated the survey”.

Interviewees were asked whether, with the benefit of hindsight, any relevant actors had been left out of the partnership. Across the 200 partnerships, 113 interviewees felt that no relevant actors had been omitted, while 87 thought that some relevant partners probably had been. There were no notable differences between partnership types (). A common reason given for thinking that more partners should have been involved was that informants would have wanted and needed additional specific knowledge or skills from potential partners that were not involved. The problem is that the need for this generally seems to have become apparent only after the project had been running for some time.

Fig. 2 Interviewees’ perceptions of whether, with hindsight, any relevant actors were excluded from the partnership, by type.

Source: own data.

Some comments were made about the fact that there is always a risk that some relevant actors might be excluded, particularly within the frame of H2020. One interviewee from a H2020 RIA stated: “There’s always risk of excluding potential actors, particularly within the competitive H2020 tender process”. Another said: “Some of our potential partners already were involved with other teams working on a project’s development for the same H2020 call for proposals”. Another factor restricting the number of participants was budget issues: “Budget for the project meant that the number of partners that could be funded was restricted. This restricted the geographical spread” according to an interviewee from an H2020 TN. Another observation was that it could be difficult for new partnerships to engage with existing networks.

3.2 The innovation process

The innovation process primarily entails optimising the sharing and exploitation of the diverse resources (for example, knowledge, skills, knowhow, equipment, infrastructure and finance) of the multi-actor partnership. It involves reaching agreement on targets and objectives (a practice linked to elucidating the innovative idea which may have originated from the funding agency) and applying mechanisms to foster resource sharing (while developing the idea into an invention and eventual commercialisation or other desired outcome).

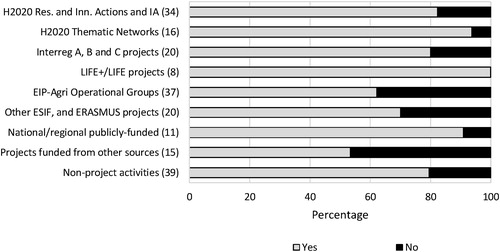

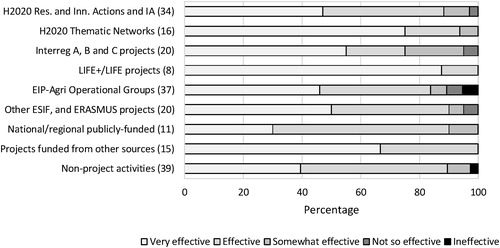

Some or all partners were involved in setting and defining the targets and objectives to a great or some extent in around 90 per cent of the reviewed partnerships (). Only projects funded from ‘other sources’ recorded substantially lower average levels of partner involvement. Interviewees confirmed that in many instances all/most partners had sat together during the preparation phase to discuss and agree on the targets and objectives. It might be expected that the extent to which all partners were involved would be strongly influenced by the size of the consortium but high levels of participation were recorded even among H2020 RIAs, many of which had 20 or more partners in the consortium.

Fig. 3 Extent to which some or all partners were involved in setting and defining the project targets and objectives, by type.

Source: own data.

Interviewees sometimes reported that, regardless of the overall level of partner involvement, a core group had the most influence in setting the targets and objectives at the very start of the process. However, in other instances, some partners had a strong influence at the start of the process, and others at a later stage. Furthermore, the partners contributed to the formulation of the targets and objectives in different ways, for example in a Spanish RDP-funded project: “Each partner built its own objectives according to its experience (sub-objectives). These sub-objectives were then gathered into one overall objective”.

There were sometimes also geographical dimensions to power in the partnership. For example, in one Interreg project in which not all the partners could take part in the decision making, according to the interviewee: “There was no proportionate adequacy on the part of all partners on the basis of competence-based experience or capacity”. Their interpretation was that: “There is no way to expect a country like Bosnia and Herzegovina to react in a way like Germany, for example”. In other words, in this project Eastern European partners were somehow in a ‘wait and see’ position with Western Europeans in terms of decision making.

Interviewees were asked which mechanisms fostered knowledge sharing between the partners. Foremost among these is the creation of bonds and common interests among the partners. The leader of the partnership should be open-minded, experienced and motivated. Bright, friendly, emotionally intelligent, hard-working and collaborative task leaders can enhance the innovation process. Partners need to contribute professionally (competencies, skills, expertise, scientific excellence and/or experience) and personally (trustfulness, right attitudes, motivation, commitment, passion and resilience). A good organisational set-up and a clear division of roles, tasks and responsibilities within the partnership are desirable.

Concerning the practicalities of knowledge sharing, Skype meetings and email exchanges were mentioned by almost all interviewees, in addition to the use of web pages, intranet and other electronic communications. A WhatsApp group was described by one interviewee as very useful and efficient. These activities were usually combined with regular or semi-regular physical meetings. Focus groups and various interactive meetings and arrangements were common. However, some partnerships operated completely ‘virtually’Footnote2, as indicated in the following quotes: “Skype (all meetings are virtual) – each country works somehow independently” and “Little collaboration and coordination among partners (only email)”. But the most enthusiastic feedback from interviewees was related to study tours (including abroad) and cases/projects, and in-field meetings that have proven important for good collaboration, interaction and sharing, reflecting the value of physical meetings.

When asked about the effectiveness of these mechanisms, 101 of the interviewees considered them to be ‘very effective’ and a further 74 to be ‘effective’ (). This positive assessment was reflected across all types of partnership. According to the interviewees, the fact that for many collaborations, many partners already knew each other has clearly eased the processes. There seem to be no evident differences in this respect in terms of partnership type. Many interviewees reported successful collaboration between academia and private businesses. Occasional difficulties arising between these types of actors were attributed to issues such as conflicting values (finding ‘ideal’ solutions against those that yield a profit) and intellectual property rights.

Fig. 4 Effectiveness of the mechanisms applied to stimulate information and knowledge exchange within the partnership, by type.

Source: own data.

One interviewee from a H2020 TN summarised how the consortium succeeded in a truly multi-actor cooperation: “Getting the right balance of multi-actors involved. Removing barriers of geography and language. Good facilitation. A fundamental understanding of what the multi-actor, the bottom-up approach is. It is allowing things to emerge rather than preconceiving or dictating, and watch it play out in order to get the interaction going. But it is not closing down conversations, it is building confidence. It is getting away from pretending it is multi-actor and pretending it is co-innovation, and pretending it is bottom-up, when it is not really. It is living the process”. Other interviewees gave similar assessments.

3.3 The innovation network

Communication between the actors in the partnership (‘core group’) and the engaged stakeholders in the wider AKIS (‘larger periphery’) can further optimise the innovation process. We assessed the importance attributed to this practice by the reviewed partnerships, the extent to which such communication between the ‘core group’ and ‘larger periphery’ occurred and through what means, and the (potential) success as assessed by the interviewees.

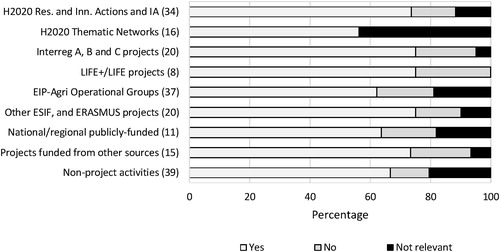

Most of the 200 interviewees believed that communication beyond the partnership is of great importance (). This view was especially strong among H2020 TNs but only marginally less so among most other project types, as well as non-project activities. Only 57 per cent of OG interviewees considered communication beyond the consortium to be important ‘to a great extent’, while for 14 per cent it was important ‘to a small extent’ or ‘not at all’.

Clearly, communication is integrated into the way of working of almost all reviewed partnerships, but the high incidence of dialogue ‘all along the process’ as opposed to dissemination (via, for example, one-day conferences or workshops) quickly became apparent during the desk study phase of our research. For example, more than 20 reviewed H2020 projects set up ‘practice-led innovation networks’, ‘farmer innovation groups’ or similar structures to foster co-innovation between the ‘core group’ and the ‘larger periphery’. This was again an especially notable feature of TNs, but examples of all other types of reviewed projects adopted ‘outreach’ practices, including ‘farmer (discussion) groups’, ‘clusters’, ‘co-creation sessions’, ‘commonage groups’, ‘joint action teams’, ‘pilot innovation environments’ and ‘ambassadors for innovation and technology’. There were also instances of partnerships launching calls for innovation proposals that were open to other multi-actor partnerships. According to our desk study results, such activities were comparatively rare among OGs, reflecting the data presented in , while for non-project activities (such as networks) that did not involve formal consortia it was sometimes difficult to identify a dividing line between the ‘core group’ and the ‘larger periphery’.

Many interviewees agreed that the involvement of external stakeholders from the beginning of the innovation process is essential. They must believe in the product, for example, in order to use and/or legitimise it and this can be achieved by involving them more in its development. Later these external stakeholders can facilitate market and supply chain formation. Communication can be improved by moving meetings from the meeting room to the demonstration field. In a donor-funded project: “The most powerful instruments were individual meetings (scientists-farmer) in the fields and the workshops where all concerned parties, not only project partners were invited. The information published on the website was also important to inform farmers who are not from the region but can learn from the experience of the project”. On the other hand, at certain stages of a co-innovation activity there is not necessarily anything to share. In other words, any requirement for continuous external communication was seen by some interviewees as not always resources well spent.

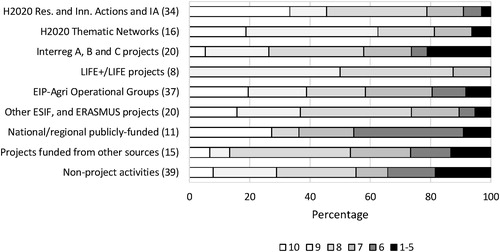

Interviewees were asked to evaluate the (potential) success of their co-innovation activity in terms of communication/outreach on a 1–10 Likert scale. The mean score for the 200 reviewed examples was 7.8 (). Reflecting the data presented in and our desk study results, several types of project were judged by the interviewees to be very successful in this respect including H2020 RIAs and TNs, LIFE/LIFE + projects and other ESIF-funded projects, where the shares of projects receiving a score of 8, 9 or 10 were 79, 88 and 74 per cent respectively. By contrast, the communication/outreach performance of OGs was variable. Although only seven OGs scored 6 or lower, very similar numbers of OGs received scores of 7, 8, 9 or 10 and, overall, only 58 per cent of OGs scored 8 or more for communication/outreach performance. Similar results were recorded for Interreg projects, non-project activities and projects funded from ‘other sources’ (58, 55 and 53 per cent respectively scoring 8 or more). At only 36 per cent for this parameter, the communication/outreach performance of projects funded from national and/or regional public funds was judged by the interviewees to be relatively poor.

3.4 The institutions

The co-innovation partnership operates according to a set of ‘legal’ and ‘customarily’ institutions. The way a partnership manages these institutions can influence the success of the innovation process.

All but a few of the reviewed partnerships received external funding. Funding programmes act as a ‘hard’ institution (a ‘rule of the game’) and frequently use the project as a form of governance. Many of our interviewees said that their co-innovation activity was formalised through a consortium agreement and work plan. For H2020 projects, there are specific rules to be followed. An interviewee from a RIA pointed out that they had learned from previous H2020 experiences: “The project followed the collective experience with included previous H2020 projects and therefore tried to be as specific as possible in the work package and task descriptions”. Such rules are not confined to H2020, of course, and an interviewee from a donor-funded project stated that: “The funding body required us to have formal contracts”. In many projects, the work was formalised in project proposals or project plans. There were however instances in smaller projects where formal arrangements were not seen to be important and not needed. For instance: “Since the partnership was very small with very distinctive roles, no formal agreements were deemed necessary to minimise administrative burden” in the case of one Belgian RDP-funded project. An interviewee from a LIFE project stated that: “There were no contracts. The cooperation between partners was established by email and with the companies by asking for services”.

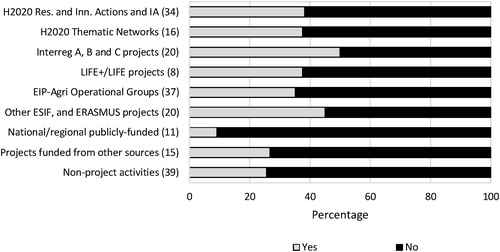

Many co-innovation partnerships are therefore regulated to some extent by externally-imposed rules, compliance with which can influence the ‘success’ of the innovation process. Interviewees were asked whether the partnership called upon any external information or assistance (and, if yes, from whom), for example on financing rules. Two thirds of the interviewees stated that they had access to information they needed to bring their activity to a successful conclusion (), although 32 considered this question to be ‘not relevant’. Some interviewees reported they had difficulties accessing information regarding various aspects, for example, ecologically certified farms in the case of a Polish RDP-funded project, but no substantial differences in responses were noted between partnership types.

Fig. 7 Interviewees’ perceptions of whether the right information was available to the partnership to bring their co-innovation activity to a successful conclusion, by type.

Source: own data.

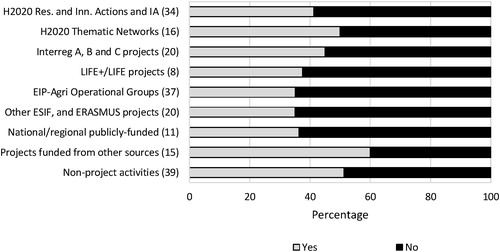

Some funding programmes, such as the EIP-AGRI, encourage the use of innovation brokers (CitationEIP-AGRI, 2013). Across the 200 reviewed partnerships, 69 involved innovation brokers or other forms of help in the proposal writing process and 131 did not (). Over 60 per cent of H2020 projects did not use an innovation broker and 91 per cent of nationally and regionally funded projects did not do so either. For those who answered ‘yes’, this very often meant consultants and advisors helping with the writing process or clarifying rules, or people with specific skills related to technical parts of the proposal writing. Sometimes it meant internal help from office administration or peer review from colleagues. Of those answering ‘no’ there were few explanations as to why, although one interviewee answered that it would have been too expensive to hire someone.

Fig. 8 Use of an innovation broker by the partnership during the proposal writing process, by type.

Source: own data.

We did not specifically request information on the use of external facilitators during the innovation process, but one interviewee from an Austrian OG reported that their facilitator was new in the position and provided little help, while representatives from two other OGs stated that an experienced process facilitator would have been useful.

According to the interviewees, three issues relating to partner cooperation are of particular importance, trust and level of competition between partners and intellectual property. In a French OG, “The cooperation is very good because: 1. specific, common strong objective: to elucidate what interferes with X quality both during production and processing, 2. common objective over time: all the stakeholders know each other since the 1990s since reviving the traditional production of X in the region was a common objective, 3. no competition between actors”. An interviewee from an Interreg project observed that: “Cooperation is sometimes rather difficult because some research partners are very ‘protective’ of their technological knowledge. So only ‘general’ information is being shared with intellectual property rights being an issue within the project partnership. This lack of openness leaves some (more entrepreneurship oriented) partners a bit hungry”. As trust between the partners develops over time, competition may be reduced. For example, in a Dutch OG, “In the beginning, there was a lack of trust between partners, but after different meetings and discussions the cooperation was very good”.

4 Discussion

Using a common methodology, we have reviewed a range of multi-actor co-innovation activities in agriculture, forestry and related sectors with respect to the main structural components of the OIS, namely the diverse actors, the innovation process, the innovation network and the institutions. While many of these activities were projects funded by the EU in the frame of EIP-AGRI (H2020 projects and OGs), our database included examples of projects funded by several other EU and non-EU programmes, and a variety of non-project approaches, including formal and informal partnerships, and even activities with no external funding.

Unlike other methodological tools, the OIS provides a framework for relating the issues of most relevance to multi-actor co-innovation in a holistic, comprehensive way. CitationVan Lancker et al. (2016) defined the ‘innovating organisation’ in the OIS as a legal entity, but we have shown that diverse forms of multi-actor co-innovation partnerships can also be the core of an OIS. By demonstrating that the OIS concept can be used to analyse multi-actor co-innovation in agriculture, forestry and related sectors, our results represent a further development of the ‘micro level’ within the innovation systems perspective.

Co-innovation requires the inclusion of ‘complementary forms of knowledge’ in the multi-actor partnership. Although such partnerships can in theory be formed in any way, our results show that the process of actor selection can be strongly influenced by previous cooperation experience (). The consortia of many reviewed projects included a core group of partners that had previously worked together in earlier projects and has over time formed a well-established (international) network of known and trusted organisations. By implication, certain groups of actors who are not embedded in the relevant networks are at risk of being consistently excluded based upon incompatible behaviour, mindsets or attitudes, personal preferences, or when realisation of exclusion only comes with hindsight.

Among large, EU-funded projects, in particular, there are powerful reasons why actors follow such an approach. Competition for funding is fierce and the consortium needs to feel confident that the partners will be able to carry out the work on time to the required standard and within budget. Actors without the necessary capacities will not be invited to join the partnership. This approach does, however, appear to have negative consequences in terms of participation of new actors in such projects. For example, the level of inclusion in H2020 of organisations from the newer EU Member States is very low in terms of total number of applications, success rates and EU financial contribution (CitationEuropean Commission, 2017a). As well as having less experience of preparing such proposals and thus a ‘track record’ of success that can be noted by proposal evaluators, these organisations are less well embedded in international networks. The fact that organisations from the 11 post-socialist EU Member States secured just 4.6 per cent of the total H2020 EU contribution in the period 2014–2016 (CitationEuropean Commission, 2017a) has worrying implications for the European Research Area.

Furthermore, even within the core groups of our reviewed partnerships there were instances where some partners felt that they were not fully contributing to the programme of work (). While some of the issues of power within partnerships are of a personal character, others probably also reflect socio-economic and socio-cultural differences and tensions, such as a lack of value attached to ‘tacit’ forms of knowledge or ideas from post-socialist EU Member States. This lack of value may be reinforced by a tendency to place trust in partners with the most project experience. Both actor exclusion and marginalisation can result in ‘group think’ and inertia in sub-optimal co-innovation partnerships.

Some initiatives that attempt to redress this imbalance in participation are already in place. For example, BioEast, the Central Eastern European Initiative for Knowledge-based Agriculture, Aquaculture and Forestry in the Bioeconomy (CitationJuhász, 2016) is attempting to raise the priorities given to topics particularly affecting Central and Eastern Europe (such the impact of climate change on continental climates and rural social cohesion in transition economies) in the European research and policy agendas. This is a more thoughtful approach than a simple requirement to achieve geographical balance in the partnership, which can lead to actors being recruited solely for that purpose. At a more operational level, there may be merit in stipulating that a share of the budget in a project proposal is reserved for suitable actors that are new to that funding programme. Such measures can promote interlinking of innovation expertise and project results that would not otherwise occur through the current practice of the same consortia undertaking several projects.

Administrative demands associated with the ‘projectification’ of innovation support can also lead to the consistent exclusion of some groups (CitationArora-Jonsson, 2017). Frequently, a project consortium can be amended only in certain, defined circumstances. Yet, our reviewed co-innovation partnerships included several examples where, with hindsight, relevant actors were excluded from the partnership (). Sometimes this was due to funding limitations, but greater flexibility in funding programme rules may beneficially allow actors from beyond the established networks to join co-innovation partnerships (either as full partners as subcontractors) part-way through the project.

The co-innovation partnership may be a legal entity or be regulated by a formal agreement, but may equally be an informal association with no fixed timescale. When the partnership is formal, it is normally not difficult to distinguish the ‘core group’ of actors from the ‘larger periphery’ of engaged stakeholders. With some less formal partnerships, it was less easy to make such a distinction but in practice participation with an innovation network is not always a binary choice: there is a spectrum of possible collaborative arrangements between two extremes (CitationHuizingh, 2011). It may also be dynamic in time, depending on the stage of the innovation process (CitationVan Lancker et al., 2016). Since the innovation process is a non-linear and iterative learning process with intense communication and collaboration between different actors and stakeholders, imposing artificial divisions would be unhelpful.

The dynamics of the innovation process are worthy of further study. While we did not assess the extent of interaction or the intensity of the collaboration, our data suggest that optimal sharing and exploitation of the diverse resources in the partnership (including knowledge) depend on the smart combination of the creation of bonds and common interests with the practicalities of knowledge sharing. Communication and collaboration between diverse actors such as farmers and researchers often involves challenges, such as reaching agreement on the research agenda (CitationFAO, 2014). Farmers may not know what is expected of them in a research setting and may not be able to communicate clearly the tools, processes or products they require. On the other hand, researchers often lack capacities to communicate their research ideas in lay terms. The level of professionalism in running our reviewed partnerships is/was nevertheless generally high. Most interviewees expressed satisfaction in terms of communication and information exchange within their partnerships ().

The widespread use by the reviewed partnerships of ‘outreach’ practices to foster dialogue between the ‘core group’ and the ‘larger periphery’ ‘all along the process’ ( and ) is an important finding of our research. The benefits of doing so are clear: such practices not only support the co-innovation process through the dissemination and embedding of innovations, but the feedback obtained by the partnership through them can strengthen the quality and relevance of their activities. But engagement with the ‘larger periphery’ was one area in which we detected differences in the performances of various types of partnerships. H2020 TNs (whose primary role is to gather ‘best practice’ on a particular topic which, if done properly, depends very much on communication beyond the core group) are among the leading exponents of stakeholder engagement ‘all along the project’. By contrast, there is a suggestion that several OGs are reluctant to do so, perhaps reflecting a tension between the desirability of securing funding for the co-innovation activity and the associated obligation to disseminate the results. The RDP framework gives less space/imposes less obligation to make connections with other projects. OGs are only required to disseminate their results (in the form of ‘practice abstracts’), which can be done without cooperating with other projects.

Innovation brokers, who can be defined as “persons or organisations that, from a relatively impartial third-party position, purposefully catalyse innovation through bringing together actors and facilitating their interaction” (CitationWorld Bank, 2012, p.221), were used by fewer than 50 per cent of the reviewed partnerships (). The use of an innovation broker depends on many parameters, for example who funds the programme/project, who is the coordinator and her/his network(s). Nonetheless, many partnerships have chosen not to use them. This may reflect the important role of established networks in partnership formation and a high level of (project) experience within them. But, even among the reviewed OGs, which may involve new partnerships, the use of innovation brokers was equally low.

CitationWalshok et al. (2014) asserted that the different levels of the innovation systems construct are interconnected and interdependent. Our results show that co-innovation partnerships do not operate independently of the institutions, and these institutions constrain behaviour and regulate interaction between primary actors (CitationCoenen and Díaz López, 2010). For example, many funding organisations, including the EU, use the ‘project’ as a preferred form of governance and policy implementation (CitationSjoblom and Godenhjelm, 2009) and the co-innovation partnership must comply with the accompanying set of ‘hard’ ‘rules’. ‘Success’ in co-innovation is therefore more likely if the policies, strategies and programmes are correctly formulated to ease compliance with the institutions, and if administrative support for this purpose is available to, and used by, co-innovation partnerships (). The EU’s guidelines for the evaluation of innovation in RDPs (CitationEuropean Commission, 2017b) recognise this fact, and identify ‘building the enabling environment for innovation’ as one of three ‘pathways’Footnote3 by which RDP measures/sub-measures can support innovation.

Yet, models of the AKIS (e.g. CitationEU SCAR, 2013) frequently do not include the enabling environment, in contrast to the AIS concept that is widely accepted among international organisations, including the World Bank, FAO and the Global Forum for Rural Advisory Services (CitationSulaiman, 2015). At the macro level of the AIS, the enabling environment encompasses factors that influence innovation positively but are controlled by policy domains other than agricultural innovation policy (CitationWorld Bank, 2012). They include (a) innovation policy and corresponding governance structures to strengthen the framework for agricultural innovation policies; (b) regulatory frameworks that stimulate agricultural innovation directly (such as intellectual property rights) or indirectly (standards that stimulate trade) or steer innovation towards certain preferred outcomes (safer food, biosafety, standards); and (c) accompanying agricultural investments in rural credit, infrastructure and markets that have synergistic effects with other instruments such as innovation funds. This issue is of practical relevance to our analysis because, across the EU, regional differences exist in these aspects of the enabling environment and in the availability of support to co-innovation partnerships to comply with the rules they impose (Citationvon Münchhausen et al., 2019).

Similarly, our interviewees stressed the importance of actors having the ‘right attitudes’ towards cooperation with partners. Actors’ attitudes are shaped by the ‘soft’ aspects of the enabling environment in a locality, such as prevailing behaviours and mindsets (CitationWorld Bank, 2012). While relevant to all types of actor (including researchers), they can particularly influence the willingness of practitioners to join multi-actor partnerships. Again, Citationvon Münchhausen et al. (2019) reported the existence of regional differences across Europe but noted that it would be simplistic to assume that there is an East-West divide. Cultural issues hampering the engagement in co-innovation projects were identified for the Mediterranean areas as well. Given the clear influence of the enabling environment on co-innovation partnership performance, therefore, it may be that, at the start of a new (2021–2027) programming period, now is the time for the EU to align itself with international practice and apply the AIS concept when developing programmes to foster co-innovation in agriculture, forestry and related sectors through support to multi-actor partnerships.

5 Conclusions

We conclude that optimisation of co-innovation in agriculture, forestry and related sectors cannot be achieved solely by focusing on improving the way the AKIS is structured, i.e. the so-called ‘macro level’. It is equally important to identify factors that support the effective functioning of co-innovation partnerships, i.e. the ‘micro level’. To achieve this, we applied the structural elements of the OIS concept to analyse the results of semi-structured interviews with 200 ‘multi-actor co-innovation partnerships’ in Europe. Our results show that the OIS concept can be extended to structure the analysis of inter-organisational and even international multi-actor partnerships. Although partnerships can in theory be formed in any way, the process of actor selection is strongly influenced by previous cooperation experience, implying that certain groups of actors can consistently be excluded. Yet, the ‘success’ of the innovation process depends primarily on the adequate inclusion of complementary forms of knowledge in the core partnership and/or through dialogue with the ‘larger periphery’. If this practice of exclusion continues, it could jeopardise both the success of individual multi-actor partnerships and the overall EIP-AGRI policy objective of ‘speeding up’ innovation. Furthermore, since the internationally recognised AIS concept is more consistent with the OIS idea than is the AKIS concept as currently interpreted by many policy makers, owing to its recognition of the important role of institutions and the enabling environment, it may prove to be a more appropriate basis for the development of future co-innovation programmes.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

tjls_a_12128593_sm0001.zip

Download Zip (669 B)Acknowledgements

This work was conducted within the LIAISON project. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement No. 773418. The opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the EU. We thank all partners in the LIAISON consortium, especially Dr. Eirik Magnus Fuglestad and Dr. Katrina Rønningen of the Institute for Rural and Regional Research, Trondheim, for their contributions to this research.

Notes

2 As a postscript, with the cancellation of a planned ‘physical’ General Assembly meeting because of the COVID-19 crisis, the LIAISON consortium held a very successful ‘virtual’ meeting with around 50 participants via Zoom on 11−13 May 2020.

3 The others are ‘identify and nurture potential innovative ideas’ and ‘build capacity to innovate’.

References

- S.Arora-JonssonThe realm of freedom in new rural governance: micropolitics of democracy in SwedenGeoforum792017586910.1016/j.geoforum.2016.12.010

- M.BogersThe open innovation paradox: knowledge sharing and protection in R&D collaborationsEuropean Journal of Innovation Management14120119311710.1108/14601061111104715

- H.ChesbroughM.BogersExplicating open innovation: clarifying an emerging paradigm for understanding innovationH.ChesbroughW.VanhaverbekeJ.WestNew Frontiers in Open Innovation2014Oxford University PressOxford328

- L.CoenenF.J.Díaz LópezComparing systems approaches to innovation and technological change for sustainable and competitive economies: an explorative study into conceptual commonalities, differences and complementaritiesJ. Cleaner Prod.1820101149116010.1016/j.jclepro.2010.04.003

- S.DogliottiM.GarcíaS.PeluffoJ.DiesteA.PedemonteG.BacigalupeM.ScarlatoF.AlliaumeJ.AlvarezM.ChiappeCo-innovation of family farm systems: a systems approach to sustainable agricultureAgric. Syst.1262014768610.1016/j.agsy.2013.02.009

- EIP-AGRIStrategic Implementation Plan European Innovation Partnership “Agricultural Productivity and Sustainability” Adopted by the High Level Steering Board on 11 July 2013Available online at http://https://ec.europa.eu/eip/agriculture/sites/agri-eip/files/strategic-implementation-plan_en_0.pdf (accessed 30 March 2020)2013

- EU SCARAgricultural Knowledge and Innovation Systems Towards 20202013European CommissionBrussel

- European CommissionHorizon 2020 In Full Swing – Three Years On – Key Facts and Figures 2014-2016Available online at https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/sites/horizon2020/files/h2020_threeyearson_a4_horizontal_2018_web.pdf (accessed 11 September 2019)2017

- European CommissionGuidelines. Evaluation of Innovation in Rural Development Programmes 2014-20202017European CommissionBrusselAvailable online at https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/evaluation/publications/evaluation-innovation-rural-development-programmes-2014-2020_en (accessed 14 May 2020)

- FAOThe State of Food and Agriculture: Innovation in Family Farming2014FAORoma

- G.FaureA.KnierimA.KoutsourisH.T.NdahS.AudouinE.ZarokostaE.WielingaB.TriompheS.MathéL.TempleK.HeanueHow to strengthen innovation support services in agriculture with regard to multi-stakeholder approachesJournal of Innovation Economics & Management28201914516910.3917/jie.028.0145

- A.FieldsendE.CroninK.Rønningen‘Light-Touch’ Review Database. Deliverable 3.1 of the EU H2020 Project LIAISON2019

- Fieldsend, A.F, Cronin, E., Varga, E., Biró, Sz. and Rogge, E. (Forthcoming): ‘Sharing the space’ in the Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation System: multi-actor innovation partnerships in Europe. Submitted to Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension.

- K.HamunenM.AppelstrandT.HujalaM.KurttilaN.SriskandarajahL.VilkristeL.WestbergJ.TikkanenDefining peer-to-peer learning – from an old ‘art of practice’ to a new mode of forest owner extensionThe Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension214201529330710.1080/1389224X.2014.939199

- E.HuizinghOpen innovation: state of the art and future perspectivesTechnovation3120112910.1016/j.technovation.2010.10.002

- J.IngramP.GaskellJ.MillsJ.DwyerHow do we enact co-innovation with stakeholders in agricultural research projects? Managing the complex interplay between contextual and facilitation processesJournal of Rural Studies782020657710.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.06.003

- A.JuhászBioEast: the Central Eastern European initiative for knowledge-based agriculture, aquaculture and forestry in the bioeconomyStud. Agric. Econ.11822016viix

- S.KilpatrickS.JohnsHow farmers learn: different approaches to changeJ. Agric. Educ. Ext.94200715116410.1080/13892240385300231

- R.Klein WoolthuisM.LankhuizenV.GilsingA system failure for innovation policy designTechnovation25200560961910.1016/j.technovation.2003.11.002

- L.KlerkxB.van MierloC.LeeuwisEvolution of systems approaches to agricultural innovation: concepts, analysis and interventionsI.DarnhoferD.GibbonB.DedieuFarming Systems Research into the 21st Century: The New Dynamic2012SpringerNetherlands457483

- A.KnierimA.KoutsourisS.MathéT.H.NdahL.TempleB.TriompheE.WielingaSupport to Innovation Processes: a Theoretical Point of Departure2015Deliverable 1.1 of the EU H2020 project AgriSpin

- A.KoutsourisE.PapaH.ChiswellH.CooremanL.DebruyneJ.IngramF.MarchandThe Analytical Framework: Demonstration Farms as Multi-Purpose Structures, Providing Multi-Functional Processes to Enhance Peer-to-Peer Learning in the Context of Innovation for Sustainable Agriculture2017Deliverable of the EU H2020 project AgriDemo-F2F

- C.LamprinopoulouA.RenwickL.KlerkxF.HermansD.RoepApplication of an integrated systemic framework for analysing agricultural innovation systems and informing innovation policies: comparing the Dutch and Scottish agrifood sectorsAgric. Syst.1292014405410.1016/j.agsy.2014.05.001

- C.LeeuwisA.van der BanCommunication for Rural Innovation: Rethinking Agricultural Extension2004Blackwell ScienceOxford10.1002/9780470995235

- P.LoweJ.PhillipsonA.ProctorM.GkartziosExpertise in rural development: a conceptual and empirical analysisWorld Dev.1162019283710.1016/j.worlddev.2018.12.005

- B.-Å.LundvallNational systems of innovation: towards a theory of innovation and interactive learningB.-Å.LundvallThe Learning Economy and the Economics of Hope2016Anthem PressLondon85106

- E.S.NederlofM.WongtschowskiF.Van Der LeePutting Heads Together: Agricultural Innovation Platforms in Practice. Bulletin 3962011KIT publishersAmsterdam

- E.O’NeillU.GraebenerG.KuperusK.LawrenceResources for Implementing the WWF Project & Programme Standards2012Woking: WWF UK

- S.OreszczynA.LaneS.CarrThe role of networks of practice and webs of influencers on farmers’ engagement with and learning about agricultural innovationsJournal of Rural Studies264201040441710.1016/j.jrurstud.2010.03.003

- W.M.RiveraG.AlexJ.HansonR.BirnerEnabling agriculture: the evolution and promise of agricultural knowledge frameworksProceedings of the 22nd Annual Conference of the AIAEEClearwater Beach FL, USA(2006) 580–591.

- S.SjoblomS.GodenhjelmProject proliferation and governance—implications for environmental managementJournal of Environmental Policy & Planning11200916918510.1080/15239080903033762

- K.SmithInnovation indicators and the knowledge economy: concepts, results and policy challengesPaper for the EC Conference on Innovation and Enterprise Creation: Statistics and IndicatorsSophia Antipolis, France(2000) 23-24 November 2000

- R.SulaimanAgricultural Innovation Systems2015GFRASLindau, Switzerland

- L.-A.SutherlandL.MadureiraV.DirimanovaM.BoguszJ.KaniaK.VinohradnikR.CreaneyD.DuckettT.KoehnenA.KnierimNew knowledge networks of small-scale farmers in Europe’s peripheryLand Use Policy63201742843910.1016/j.landusepol.2017.01.028

- J.SwinnenR.KuijpersValue chain innovations for technology transfer in developing and emerging economies: conceptual issues, typology, and policy implicationsFood Policy83201929830910.1016/j.foodpol.2017.07.013

- J.A.TurnerJ.KlerkxK.RijswijkT.WilliamsT.Barnardsystemic problems affecting co-innovation in the New Zealand agricultural innovation system: identification of blocking mechanisms and underlying institutional logicsNJAS - Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences7620169911210.1016/j.njas.2015.12.001

- J.Van LanckerK.MondelaersE.WautersG.Van HuylenbroeckThe organizational innovation system: a systemic framework for radical innovation at the organizational levelTechnovation52-532016405610.1016/j.technovation.2015.11.008

- S.von MünchhausenSzBiróA.FieldsendA.M.HäringS.MayrK.RønningenIdentification of key challenges and information needs of those enabling and implementing interactive innovation projects within the EIP-AgriPaper Presented at the 24th European Seminar on Extension (and) Education. 18-21 June 2019Acireale, Italy(2019)

- M.WalshokJ.ShapiroN.OwensTransnational innovation networks aren’t all created equal: towards a classification systemThe Journal of Technology Transfer39201434535710.1007/s10961-012-9293-4

- E.WielingaF.G.E.Geerling-EiffNetworks with Free ActorsK.J.PoppeC.TermeerM.SlingerlandTransitions Towards Sustainable Agriculture and Food Chains in Peri-Urban Areas2009Wageningen Academic PublishersWageningen113137

- World BankAgricultural Innovation Systems: An Investment Sourcebook2012World BankWashington DC

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:http://https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2020.100335.