Abstract

The last decades of the 20th century witnessed a profound experiment to increase the role of markets in local government service delivery. However, that experiment has failed to deliver adequately on efficiency, equity or voice criteria. This has led to reversals. But this reverse privatization process is not a return to the direct public monopoly delivery model of old. Instead it heralds the emergence of a new balanced position which combines use of markets, deliberation and planning to reach decisions which may be both efficient and more socially optimal.

1 Introduction

Experimentation with contracting out (privatization) of local government services grew over the 1980s and 1990s, but we have begun to see reversals in that trend. Compulsory competitive tendering has been abolished in the UK and Australia; New Zealand elected a prime minister focused on rebuilding internal government service delivery capacity; and US local government managers began to bring previously contracted services back in house in a process of reverse privatization. This reassertion of the public role is not the direct government monopoly of the past. Instead we see local governments using markets, but playing a market structuring role in building competition, managing monopoly and reducing transactions costs of contracting. But market management is not the only role of government. Managers also see the importance of engaging citizens in the public service delivery process. This paper describes both theoretically and empirically how this new approach to governmental reform balances the efficiency benefits of market-type engagement with the technical benefits of planning and the civic benefits of public engagement.

There has been a shift in understanding of the role of the state in public service delivery over the last few decades. The old public administration emphasized direct government delivery, hierarchical control, and a separation of politics and management to ensure due process for citizens and limit outside influence among public employees. This system was criticized as too slow and inflexible by proponents of the New Public Management who argued market-type management approaches could be effectively applied to the public sector (CitationHood, 1991; CitationOsborne & Gaebler, 1992). New Public Management emphasized speed and flexibility and touted the advantages of markets for both greater private sector engagement and consumer voice for citizens (CitationSavas, 1987). Market solutions suffer from high transactions costs and this has led to a new emphasis on network governance based on relational contracting and trust (CitationGoldsmith & Eggers, 2004; CitationBrown, Potoski, & van Slyke, 2007). However, the close relationships between contractors and government in network governance undermine democratic accountability. The lack of control and accountability in contracting networks has led others to emphasize citizens are more than consumers and government more than a contract manager (CitationdeLeon & Denhardt, 2000; CitationDenhardt & Denhardt, 2003; CitationSclar, 2000; Starr, 1987).

One of the intellectual foundations for market approaches to public goods is public choice theory (CitationTiebout, 1956). However, the public choice reliance on aggregated individual preferences in a market-type system can lead to public value failures because it allows no space for a deliberative social process of public participation (CitationBozeman, 2002). Problems with preference misalignment cause the aggregation of individual preferences to diverge from the collective social preference (CitationLowery, 1998). However, democratic approaches to aggregate individual preferences through voting may not be socially optimal or stable either according to social choice theory (CitationSager, 2002a). What is missing in both these approaches is a space for deliberation to identify collective needs and common solutions. Recent work in communicative planning and deliberative democracy shows that through deliberation individuals shift preferences toward more collective goals and thus arrive at a more socially optimal choice (CitationFrug, 1999; Lowery, 2000; Sager, 2002b). When combined with markets and voting, deliberation may be both democratic and efficient.

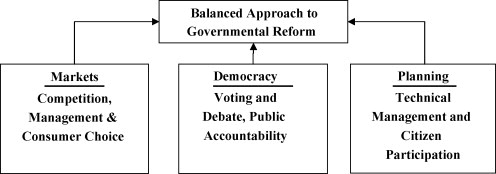

In this chapter, I argue there is a rebalancing of government reform that capitalizes on the efficiency of markets, the technical expertise of planning, and the social choice of democracy without the problems of accountability and decision cycling that occur under any of these strands alone. This paper explores the theoretical basis for the emergence of such a balanced position, and provides evidence this is occurring in local government practice. Public managers have moved beyond the dichotomy of markets or planning, and instead embrace a mixed position which complements the advantages of markets with the benefits of public engagement. This balance between deliberation and markets recognizes citizens are more than consumers, and government is more than a market manager. Government creates the space for collective deliberation to occur and through this process a sense of the social is built. See Fig. 1.

2 Shifts in theory

2.1 Understanding the difference between market and government

The New Public Management revolution in local government promotes market-based management techniques to increase efficiency and citizen choice, but it fails to consider the subtle and important ways in which markets and government differ. Markets are based on the principle of utility maximization. Adam Smith articulated the notion of an invisible hand whereby producers and consumers in a market (motivated by individual utility maximization) would create competitive price pressure, promote innovation and ensure service quality thus securing socially optimal production. The key to this happy result was competition. But many services are natural monopolies, and thus do not benefit from the invisible hand of Adam Smith’s competitive market. Competition erodes, and with it the guarantee of this market-based socially optimal result.

Key to the challenge of using markets for public goods is recognition of what creates a public good in the first place. Public goods, by definition, arise from market failure as self-interested individuals undersupply critical social goods or free ride on common resources. Congestion, pollution, and public health are all examples of market failed public goods which require some collective intervention to address. Typically this intervention is in the form of government regulation or production. With increased urbanization, externalities become more pronounced (congestion, public health impacts, etc.), more services experience market failures, and citizen demand for public provision increases. This has led to the expansion of local government service delivery over time into new arenas of service delivery – e.g. garbage collection, water distribution, environmental management, infrastructure provision and human services.

However, market delivery mechanisms still may be possible for some of these goods. The potential of voluntary bargaining to address externalities, first articulated by Ronald Coase in his article on the Problem of Social Cost (1960), rests on the notion of a bargaining framework where individuals with full information and clear property rights pay producers of positive (negative) externalities to increase (reduce) them in a voluntary scheme. When the link between the supplier and the consumer is close, such payment schemes are easier to arrange. When larger numbers of actors are involved, these voluntary solutions tend to break down and government organization of production is preferred (CitationCoase, 1960; Webster, 1998).

Recent scholarship suggests that in dense urban settings, the possibilities of voluntary solutions may be larger than once thought. For example in squatter settlements where government is unwilling or unable to extend basic services, individuals come together to provide services – urban transportation, water delivery – that might traditionally be provided by government (CitationGilbert, 1998). That people have voluntarily organized to meet collective needs attests to the power and potential behind voluntary market solutions. In arguing for the ‘spontaneous order’ created by markets, CitationWebster and Lai (2003) suggest government delivery may hamper such private solutions through regulation and intervention that raises costs and restricts access, especially for the poor. This has been one of the rationales behind the promotion of market-delivered services for the poor (CitationGraham, 1998).

While these market approaches show promise, they still require a significant government role. Where these market solutions are most pronounced (e.g. squatter settlements); property rights of consumers are least secure. This tilts the bargaining power toward the private producers of public goods and can lead to problems in price and quality due to inadequate government oversight. It also promotes an economic conception of citizenship where rights to basic services – even those critical to life such as water – are based on ability to pay. In developing countries, where market based schemes for water delivery have been promoted by foreign donors, we have seen large increases in consumer prices which have led to civic protest, most notably the water riots in Cochabamba, Bolivia (CitationKohl, 2004). These market solutions promote a version of citizen choice and empowerment based on market-based bargaining, that has been challenged as a veil to reduce citizenship rights to basic services (CitationMiraftab, 2004). Even in developed countries, such as Canada, privatization has been challenged as an assault on both citizenship and democracy (CitationCUPE, 2001).

There is something more fundamental and than cost and service quality in the public goods equation. Citizens expect involvement, voice and control over government decisions. Deliberation is the key to democracy. But anonymous and spontaneous markets do not create a space for deliberation. The individual can choose to buy or not, but deliberation on the nature of the choice is not typically part of a market. Markets, as aggregations of individuals, do not become social spaces for deliberation unless market governance is designed that way. Recall that the efficiency benefit of Adam Smith’s invisible hand was that it did not require deliberation. But as market solutions have been applied to public service delivery, problems with preference alignment have been found (CitationLowery, 1998). When individual preferences are substituted for public preferences (e.g. a private provider’s preference for profit vs. the public interest in access and service quality), we have failure of public goods again. Consumers may substitute individual preferences for public objectives when they shop as individuals in a privatized market for public goods. This has been found in voucher schemes for education, child care and job training where socially suboptimal choices are made by individual consumers who, due to lack of information or time, choose convenience over quality and thus undermine the intended societal educational benefits (CitationHipp & Warner, 2007; CitationLowery, 1998; CitationMeyers & Jordan, 2006).

Recent research has shown that through deliberation, citizens shift their individual preferences more toward collective well being (CitationLowery, 2000; Sager, 2002b). Creating the space for such democratic deliberation is a key function of government. CitationFrug (1999) has argued that such community building is the ultimate public good. Citizens in a democratic society must develop the capacity to engage difference, see common problems and craft socially optimal solutions. In planning, this has led to a new subfield of communicative planning which emphasizes how power imbalances can be altered through a deliberative process which allows more citizen voice and participation (CitationForester, 1999; Healey, 1996). In public administration attention is shifting back to a focus on citizenship, participation and public value. The role of government is not simply to steer a market process; it also must serve citizens (CitationDenhardt & Denhardt, 2003, 2000). Governments must have the capacity to help citizens come together to identify problems and to debate choices (CitationNalbandian, 1999, 2005). Citizen engagement is more than the consumer orientation and competition advocated by New Public Management (CitationOsborne & Gaebler, 1992). Citizens need more than the exit option of markets; they need the opportunity to stay, exercise voice, and invest in their community (CitationFrug, 1999). Participation in local decision-making is seen as the foundation for a democratic society. Learning to solve collective problems, to engage the heterogeneous diversity found in the urban landscape, and to practice deliberation – these are the foundations for a democratic society.

2.2 Recognizing the civic within the market

In order to use markets for public goods, more attention must be given to the civic foundations of markets and the potential for deliberation within them. The social construction of markets challenges the anonymity of the invisible hand, and shows the importance of trust and embeddedness in creating the social norms that permit markets to function (CitationGranovetter, 1985; North, 1990). This line of research has been especially important in the transition literature on Eastern Europe and China. Market emergence requires a state role in creating the legal framework necessary to support market functioning (bonding, insurance and property rights). It also requires attention to social networks and changing social norms (CitationNee, 2000). Market entrepreneurship requires contestation and competition. Neither was encouraged under state socialism, and so building the norms for contestation and competition is part of the sociological foundation both for civic engagement and market emergence (CitationWarner & Daugherty, 2004).

Some have argued that democracy and market economies are mutually reinforcing (CitationPrzeworski, 1991), and indeed this was the philosophy behind most international donor investment in Eastern Europe after the transition. However, inadequate social foundations for market functioning led to corruption and concentration of privatized assets into the hands of a few, understood as gangster capitalism or “the great stealing” in much of the region, especially Russia (CitationHolstrom & Smith, 2000).

Markets naturally concentrate power. A laissez faire market does not naturally emerge. Absent state regulations to ensure more competitive market functioning, and social norms and networks to ensure broader bargaining power, concentration is an expected result. Even mathematical models of market systems show that wealth concentrates, and competition disappears as the models play out over time (CitationHayes, 2002). This is especially common in many publicly provided services which are natural monopolies, or tend toward monopoly – water, waste collection, electricity, etc.

CitationLowery (1998) has warned that public service contracting markets are at best, quasi markets of one buyer (government) and a few sellers. Thus these markets fail to create competition. This may be why local governments show more stability in their use of contracting for public goods if they focus on managing monopoly. CitationWarner and Bel (2008), in their comparative study of water distribution and solid waste disposal contracting in the US and Spain, found Spanish local governments had both higher levels of contracting and more stable contracts than in the US. They attributed these differences to the Spanish focus on managing monopoly through mixed public/private firms which enjoy the benefits of natural monopoly (economies of scale) and private sector management, but retain public values and accountability. In the US, by contrast, local governments focus on promoting competition between government and private firms. This resulted in less contracting over all and much higher rates of reversals.

Lack of competition is not the only failure. Market-based solutions also create preference alignment problems as individuals substitute private preferences (convenience) for public preference (quality) (CitationHipp and Warner, 2007). Markets also can lead to preference errors on the part of purchasers due to information asymmetries and transactions costs (CitationLowery, 1998). Some of these market failures can be addressed through investments in the social foundation – public education, regulatory standards or anti-trust laws. The important challenge is to understand the social foundations of markets. The late 20th century was an experiment to see how far we could push the boundaries of market into state provision of market-failed public goods. However, if we want to use markets for public goods, then we must understand what is needed for those markets to work.

Market solutions for public goods promoted in both developing countries and Eastern Europe failed to give sufficient attention to the failures of quasi markets outlined above or the important social foundations of markets which help ensure their smooth functioning. CitationPolanyi (1944) argued that human interaction is based on more than market exchange. Reciprocity and redistribution are key. When markets subordinate other aspects of human life, there will be a counter movement to moderate them. This may help explain the strong anti-privatization movement in water in Bolivia and South Africa. It also may explain the growth in reverse privatization we are seeing in the US and the shifts away from competitive tendering among the early privatizers: the UK, Australia and New Zealand.

Privatization requires government capacity to manage markets and citizen/consumer capacity to effectively engage them. Privatization is not a reduction in the role of the state as some pro-privatization theorists argue (CitationSavas, 1987), but rather a shift in state role (CitationSchamis, 2002) toward managing new tools (CitationSalamon, 2002) including a more direct market management role. The structuring of contracts, regulation of price and quality, as well as direct action as a supplier or purchaser in the market are all tools governments have used to engage markets more effectively in public service delivery. Privatization does not allow government to contract out and walk away, instead government must remain actively engaged as a market player directly providing services and contracting out in a dynamic process to ensure competition, efficiency, service quality and broader public objectives (CitationHefetz & Warner, 2004, 2007; CitationWarner & Hebdon, 2001; CitationWarner & Hefetz, 2008).

2.3 The promise and failure of market approaches

One of the purported advantages of market approaches to government was that they would give the consumer citizen more choice and voice in government service delivery. CitationTiebout (1956) showed that, especially at the local government level, a public market of competing local governments gave mobile residents choice in the tax/service mix of their communities, and provided competitive pressure for local governments to remain efficient. At a time of rapid suburbanization and geographic mobility in the post-WWII US, a public choice model based on mobility seemed reasonable. Later studies of such Tiebout sorting have challenged the assumption that decisions are based primarily on efficiency considerations. Sorting by race and class has had a major impact on the landscape of fiscal and service inequality in metropolitan areas (CitationFrug, 1999; Lowery, 2000; Troutt, 2000; CitationWarner & Pratt, 2005).

A strong sense of localism has led to the notion that public services are private, club goods, available only to residents within a particular jurisdiction (CitationFrug, 1999). This narrowing of the public view has undermined efforts to cooperate at the regional scale. While such localism may promote democracy and choice, the need for planning at the metropolitan regional scale suggests the region may be the appropriate scale for a local focus today (CitationBriffault, 2000). The challenge is how to create the appropriate forum for a regional democratic conversation (CitationFrug, 2002). Both technocratic planning “things regionalism” and private market approaches “privatization” have been shown to exacerbate inequality and narrow voice to growth coalition elites (CitationBollens, 1997; CitationLogan & Molotch, 1987; CitationWarner, 2006b; CitationWarner & Hefetz, 2002, 2003, 2008). We need a “people regionalism” that incorporates both the technical and the market but subjects it to social debate.

One of the promises of privatization is that it would give consumer citizens even more voice than voting (which is infrequent), or changing communities (which requires the means to move). By privatizing government services, citizen consumers would enjoy market choice and could shop for services on a more regular basis than they can vote or move between communities. However, empirical analysis of US contracting behavior shows that attention to citizen voice is lower among municipalities that privatize more (CitationWarner & Hefetz, 2002). Because privatization is typically a contract between government as purchaser and one or a small group of suppliers, the citizen consumer does not see a choice of providers.

Similarly, market approaches could allow governments to obtain economies of scale at the regional level. Privatization and inter-municipal cooperation are popular local government reforms. However, neither promotes intra-regional equity. Privatization is favored by richer suburbs over rural or core urban communities (CitationKodrzycki, 1994; CitationWarner, 2006a; CitationWarner & Hefetz, 2003, 2008), and inter-municipal cooperation, because it is voluntary, does not lead governments to choose to cooperate with their less well off neighbors (CitationWarner, 2006b).

Efficiency gains, another promise of the market model, have been fleeting. US research shows that only with monitoring did local governments experience efficiency gains under privatization (CitationWarner & Hefetz, 2002). Meta analyses of privatization and cost studies show inconsistent results, but the majority of studies do not show cost savings under privatization (CitationBoyne, 1998; Hirsch, 1995; Hodge, 2000; CitationBel & Warner, 2008a). Some have attributed this lack of efficiency gains to the high transactions costs of contracting (CitationHefetz & Warner, 2004; CitationSclar, 2000). Contract specification and monitoring have turned out to be more challenging and costly than first thought (CitationPack, 1989; Prager, 1994). While some of these costs can be controlled through a more careful market management role, transactions costs is not a sufficient framework for understanding the challenges of contracting (CitationBel & Warner, 2008b; CitationHefetz & Warner, 2007).

2.4 Combining deliberation and markets

We have seen above that markets do not ensure equity, voice or efficiency. Markets are a tool that can be used in public service delivery but they must be managed carefully to achieve the desired goals. Local government must have the capacity to structure markets and engage citizens in a deliberative process.

While the experiment with market reforms has been proceeding in public administration, in the field of planning renewed interest has been focused on deliberation and communication. Building from Habermasian dialogue, a field of communicative planning has arisen which focuses on the process of public participation and communication in planning decisions (CitationForester, 1999; Healey, 1996). Communicative planning sees a special role for the planner in clarifying options and challenging misinformation (CitationForester, 1989; Healey, 1997; Innes, 1995). While some critique communicative planning theory for being too focused on consensus and failing to adequately address power differences – especially the naïve assumption that the planner can be abstracted from his/her structural position in a nexus of power and professional expertise (CitationMcGuirk, 2001), others argue that planners can facilitate an advocacy planning process that challenges existing power structures and gives more voice to the poor (CitationKrumholz & Clavel, 1994; CitationReardon, 1999).

Although market-based reform efforts have fuelled negative views of government among citizens and the media; local government managers show increasing interest in serving public values (CitationAllmendinger, Tewdwr-Jones, & Morphet, 2003; CitationMoore, 1995). Public opinion research in the US has found that citizens typically equate government with self-serving politicians or unresponsive bureaucracy, leading to a negative view (CitationBresette & Kinsey, 2006). But when the dialogue is reframed in terms of government creating the public structures that promote economic efficiency and security, then citizen views become more positive. The challenge is to rebuild the capacity of government to lead; and of citizens to participate in a collective deliberative process. Local government has a progressive potential exhibited by leadership at the municipal scale to promote innovation (CitationClavel, 1986). CitationNalbandian (1999, 2005) has articulated government capacity as the capacity to bring a community together to solve problems in a way that does not rend the social fabric, so they can come together again to solve the next problem. Based on the exciting innovations in Puerto Alegre, Brazil, city leaders around the world are experimenting with new models of citizen engagement – citizen budgets, citizen visioning, and encouraging neighbourhood control over service delivery (CitationAbers, 1998; CitationOsborne & Plastrick, 1997; CitationPotapchuck, Crocker, & Schechter, 1998; CitationGaventa, 2004).

In this regard, the planner’s role is similar to the local government manager’s role, though the planner is primarily focused on process and the government manager on direct service delivery. How to incorporate this need for deliberation in the context of a more market-based system of government service delivery is the challenge.

Public choice theory incorrectly assumed that consumer choice in a competitive market could address public goods problems. Likewise, democratic alternatives, such as majority voting, have been shown to lead to unstable decision cycles and manipulation. Social choice theory has documented the impossibility of solutions which are both efficient, democratic and serve the public interest. Cycle free decisions involve some form of expert sovereignty (CitationSager, 2001, 2002b).Footnote1 So neither voting nor consumer choice alone can yield a stable, democratic and socially optimal solution. CitationSager (2002b) suggests that deliberation can be used as a supplement in an iterative process that circumvents these problems. “Deliberation brackets preferences and voting brackets the giving of reasons, but shifting between these decision-making modes can bring both types of information into play… which helps to explain why decision cycles do not occur as frequently in practice as predicted by social choice theory.” (CitationSager, 2002b, p. 376) Through deliberation individuals can see the need to shift toward more socially beneficial decisions (CitationFrug, 1999; Lowery, 2000). This is the promise of a deliberative and democratic planning process. However, deliberation alone, can lead to the same kind of impossibility problems as voting (CitationSager, 2002b). So the challenge is to use a process that combines planning, markets, voting and deliberation.

3 Shifts in practice

The first section of this chapter documented a shift in theory from an emphasis on market approaches, to a more balanced concern with democracy and planning. I argue that local government, in its practice, is moving beyond the either/or dichotomy of planning or markets, and embracing a more balanced mixed position. Three brief examples will suffice.

New Zealand and the United Kingdom were early and radical innovators promoting extensive privatization through compulsory competitive tendering. In New Zealand, we are seeing a shift back with the new 2002 local government law which recognizes the need to rebuild government capacity to both manage markets and build the local foundation for democracy. Local government is seen as the forum where a balance between economic development, environmental and civic interests can be crafted. In the United Kingdom we have seen a shift away from Compulsory Competitive Tendering toward a ‘best value’ regime which includes a broader range of objectives than just efficiency. While terms such as ‘contestability’ and ‘scrutiny’ emphasize competition and accountability, there is also emphasis on citizen engagement. In the US, privatization was never compulsory, but support for market-based government is strong. However contracting out peaked in 1997 and reverse contracting is now larger than new contracting out. Concerns with reductions in service quality and lack of cost savings drove this shift. In each of these cases market approaches are not jettisoned; rather use of market is balanced by recognition of the need for a government management role – both to structure the market and to ensure a deliberative space for citizens.

3.1 New Zealand

New Zealand was an early leader in implementing market-based approaches to government. They tested the notion of enterprise units – focused on meeting goals and using a private sector management approach which promoted competition, outsourcing, privatization and a customer service orientation. Many services were sold off or privatized. New Zealand’s approach to reform served as an exemplar for other countries, especially the United States (CitationOsborne & Plastrick, 1997). At the local level private companies emerged to manage roads, which are one of the largest budget areas for local government. New Zealand local government managers became experts in contract management. Contracting networks were viewed as more flexible than direct government and considered the wave of the future. As they moved from market management to partnerships, they recognized that partnerships need management and accountability.

However, the results of privatization were only partly satisfactory. Regulation alone was not enough; an accountability framework was needed, along with professional local government management. In the late 1990s New Zealand made a course correction and reasserted a government role. The election of Prime Minister, Helen Clark, in 1999, reflected in part a desire to rebuild government capacity.

Certainly a not inconsiderable part of my government’s time has been spent in rebuilding public sector capacity to deliver the results the public demands…. The public sector reform which went on in the 1980s and 1990s was aimed at making government agencies more efficient, but it was undoubtedly also aimed at ensuring that there was less government. Our reforms have banked the efficiency gains, but have looked to build effectiveness as well….a high performance and highly skilled public sector is required. (CitationClark, 2005)

In 2002, a new local government law was passed (CitationLocal Government New Zealand, 2003). This law recognized that local government must balance competing objectives: economic development, social wellbeing, environmental management and civic engagement. This process is too complex for a simple market mechanism. The law recognized that citizens are more than market-based service customers. Local government must give more attention to the importance of a democratic base and citizen consultation.

New Zealand is ahead of the US in many respects. It has undertaken more privatization and outsourcing at the local level. Its performance management systems are more sophisticated, and it has an explicit audit and accountability framework. It undertook a significant amalgamation of local government in 1989 which created a structural framework for regionalism based on more sensible urban and ecological boundaries (e.g. regionalism that encompasses a watershed, or links city and suburb). Although a clearer framework for local government has been laid out, there are still problems creating effective regional collaboration and crafting the balance between environmental, social, economic and cultural objectives, especially in areas with development pressures. Consultation is not without its problems. A deliberative process can lead to more social choices, but too much consultation can lead to “governance exhaustion.” However, the notion of a more balanced position involving markets, democracy and planning has been articulated. Local government leaders are attempting to balance deliberative process with the efficiency of markets.

3.2 United Kingdom

The United Kingdom was another early innovator in privatization. With Margaret Thatcher, emphasis on competition and breaking the monopoly of government power was paramount. Competitive tendering was made compulsory from 1988 to 1998. But results suggest the program was not that successful in breaking the monopoly of local government control as a large percentage of contracts were won by local government teams (CitationSzymanski & Wilkins, 1993). Nor was the program successful in saving money, as most cost savings eroded over time (CitationSzymanski, 1996). With the election of Tony Blair in 1997, a shift back toward a more balanced position began. The “best value” framework was implemented in 1999 in recognition that local government needed to balance more objectives than simple cost efficiency. Greater attention was given to accountability and citizen engagement (CitationMartin, 2002). Best value gave attention to speed, service quality and citizen voice in the service delivery process. Although the national government was keenly interested in promoting local government innovation and viewed contestability as a core reform, it also recognized the need to engage local government managers as partners, not rivals, in the reform process (CitationEntwistle & Martin, 2005). Local government managers’ reluctance to externalize services reflected a public service ethos, the need for control and market management, and the need to retain core competencies within the public sector (CitationEntwistle, 2005).

3.3 United States

In the United States public discourse at the national level regarding local service delivery was not as pronounced as in New Zealand or the United Kingdom. Local government reform is controlled at the state level and this leads to great diversity and more local government independence.

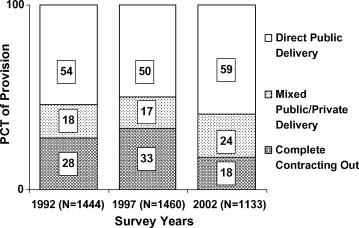

However, support for privatization was strong in the US. In 1982 the professional association of city managers, the International City/County Management Association commenced a Survey of Alternative Service Delivery to measure the level of privatization. That survey has been repeated every five years since. This permits tracking trends over time, something not possible in other countries. Although trends were relatively flat, there was increasing experimentation with privatization after 1992. But contracting out peaked in 1997, and in 2002 (the latest data available) we see a return to public delivery and a dramatic increase in mixed public and private delivery (CitationWarner & Hefetz, 2008). See Fig. 2. As contracting out has fallen, mixed public/private delivery has grown. This mixed delivery occurs when governments both provide a service directly and contract out a portion. This creates competition between public and private providers, maintains government capacity and internal knowledge about the process of service delivery, and ensures continued citizen involvement in the service delivery process (CitationWarner & Hefetz, 2008). Regression models for 1992, 1997 and 2002 show a priority for market management concerns, but emergence of a balanced concern with market management and citizen voice in 2002. The challenges of local government service delivery are about more than efficiency. Local government leaders and citizens alike recognize the need to balance multiple objectives: service quality, citizen participation and economic efficiency. This explains the emergence of a mixed market position.

Fig. 2 Trends in local government service delivery, 1992–2002. Percent of provision averaged across all responding governments. Provision is percent of total number of services provided on average. Provision rates: 66%, 61%, 53% for 1992, 1997, 2002, respectively. Author analysis based on data from the International City/County Management Association, profile of alternative service delivery approaches, US Municipalities, 1992, 1997, 2002, Washington, DC. Reprinted from CitationWarner and Hefetz (2008).

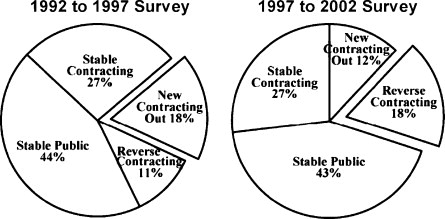

Reverse privatization also grew dramatically over the decade from 12% of all service delivery in the 1992–1997 period, to 18% of all service delivery from 1997 to 2002 (CitationHefetz & Warner, 2007). See Fig. 3. ICMA added a question to its 2002 survey asking why managers brought previously contracted work back in house and the primary reasons where problems with service quality, lack of cost savings, internal process improvement, and citizen support for bringing the work back in house (CitationWarner & Hefetz, 2004). A similar survey fielded in Canada the following year, found exactly the same rank order of reasons for reverse privatization (CitationHebdon & Jalette, 2008).

Fig. 3 Dynamics of local government service delivery, 1992–2002. Author analysis based on data from the International City/County Management Association, profile of alternative service delivery approaches, survey data 1992, 1997, 2002, Washington, DC. Reprinted from CitationHefetz and Warner (2007).

Statistical analyses of this shift over the decade 1992–2002 (CitationHefetz & Warner, 2007) show the increase in reverse contracting is only partially explained by transactions costs (asset specificity, monitoring). What is more important are place characteristics and citizen voice. Reverse contracting is part of a market management approach, but also is a response to increased attention to citizen voice. These results confirm the existence of a new balanced model of local government reform which gives attention to both markets and citizen voice.

4 Conclusion

The last decades of the 20th century witnessed a profound experiment to increase the role of markets in local government service delivery. However, that experiment has failed to deliver adequately on efficiency, equity or voice criteria. This has led to reversals. But this reverse privatization process is not a return to the direct public monopoly delivery model of old. Instead it heralds the emergence of a new balanced position which combines use of markets, democracy and planning to reach decisions which may be both efficient and more socially optimal.

Local governments play a key role in community problem solving and this is the fundamental public good. To do so, they must move beyond market models of government and promote deliberation and public participation. The New Public Management reforms focused on competition and entrepreneurialism. But competition is ephemeral in public service markets and provides a poor foundation for equity. Entrepreneurship encourages secrecy and risk taking that may be inappropriate for critical public services (CitationdeLeon & Denhardt, 2000; CitationKelly, 1998). Government is meant to be a stabilizing force, designed to reduce risk and ensure security. It is structured around principles of openness and stewardship where participation and representation are the foundation, not competition.

The privatization experience of the late 20th century has taught us that markets require governance. Managing markets for public services is both challenging and costly. These market networks limit traditional government mechanisms to ensure public control, accountability, representation and balance of interests. Using markets alone can lead to economic conceptions of citizenship (e.g. citizen rights defined by ability to pay, limited sense of public space, little collective sharing of externalities). Recognizing the democratic deficit in these arrangements has led to greater emphasis on public planning and democratic engagement. We see this in the reverse privatization trends and the emergence of a more balanced position that combines market approaches with participation and planning. At the beginning of the 21st century, this balanced approach is the new reform.

Notes

1 Research on social choice argues the impossibility of decision processes that are both manipulation-free and democratic (the Gibbard–Satterthwaite theorem), the impossibility of combining individual liberty and respect for unanimous preference rankings (Sen theorem), and the impossibility of amalgamating individual preference rankings in a way that is both consistent and democratic (Arrow theorem). For more detail on these theorems see: Arrow, K. J. (1963). Social choice and individual values. New York: John Wiley; Gibbard, A. (1973). Manipulation of voting schemes: a general result. Econometrica, 41, 587–601; Satterthwaite, M. A. (1975), Strategy-proofness and Arrow’s conditions: existence and correspondence theorems for voting procedures and social welfare functions. Journal of Economic Theory, 10, 187–217; Sen, A. (1970), The impossibility of a Paretian liberal. Journal of Political Economy, 78, 152–157.

References

- R. Abers . From Clientelism to cooperation: Local government, participatory policy, and civic organizing in Porto Alegre, Brazil. Politics and Society. 26(4): 1998; 511–537.

- P. Allmendinger , M. Tewdwr-Jones , J. Morphet . Public scrutiny, standards and the planning system: Assessing professional values within a modernized local government. Public Administration. 81(4): 2003; 761–780.

- Bel, Germà, & Warner, M. E. (2008a). Does privatization of solid waste and water services reduce costs? A review of empirical studies. Resources, Conservation & Recycling, in press..

- Germà Bel , M.E. Warner . Challenging issues in local privatization. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy. 26(1): 2008; 104–109.

- Scott Bollens . Concentrated poverty and metropolitan equity strategies. Stanford Law and Policy Review. 8(2): 1997; 11–23.

- G.A. Boyne . The determinants of variations in local service contracting—garbage in, garbage out?. Urban Affairs Review. 34(1): 1998; 150–163.

- B. Bozeman . Public-value failure: When efficient markets may not do. Public Administration Review. 62(2): 2002; 145–161.

- Bresette, P., & Kinsey, M. (2006). Public structures: A constructive model for government. Public Briefing No. 6., A network for ideas and action, New York, NY: Dēmos. http://demos.org/talkaboutgov/toolkit/docs/publicStructures_es.pdf..

- R. Briffault . Localism and regionalism. Buffalo Law Review. 48(1): 2000; 1–30.

- T. Brown , M. Potoski , D. van Slyke . Trust and contract completeness in the public sector. Local Government Studies. 33(4): 2007; 607–623.

- Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE). (2001). Dollars and Democracy: Canadians Pay the Price of Privatization Annual Report on Privatization, Ottawa, Canada: CUPE. http://www.cupe.ca/issues/privatization/arp/default.asp..

- Clark, H. (2005). Patterson oration: Helen Clark – Full transcript May 6, 2004. Australian and New Zealand School of Government. ANZSOG, Carlton, Victoria Australia http://www.anzsog.edu.au/images/docs/news/Patterson_Oration.pdf..

- P. Clavel . The progressive city: Planning and participation, 1969–1984. 1986; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ

- R.H. Coase . The Problem of Social Cost. Journal of Law and Economics. 3 1960; 1–44.

- L. deLeon , R.B. Denhardt . The political theory of reinvention. Public Administration Review. 60(2): 2000; 89–97.

- J.V. Denhardt , R.B. Denhardt . The new public service: Serving, not steering. 2003; M.E. Sharpe: Armonk, NY

- R.B. Denhardt , J.V. Denhardt . The new public management: Serving rather than steering. Public Administration Review. 60(6): 2000; 549–559.

- T. Entwistle . Why are local authorities reluctant to externalise and do they have good reason?. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy. 23(2): 2005; 191–206.

- T. Entwistle , S. Martin . From competition to collaboration in public service delivery: A new agenda for research. Public Administration. 83(1): 2005; 233–242.

- J. Forester . Planning in the public domain. 1989; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA

- J. Forester . The deliberative practitioner: Encouraging participatory planning processes. 1999; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA

- G.E. Frug . City making: Building communities without building walls. 1999; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ

- G.R. Frug . Beyond regional government. Harvard Law Review. 117(7): 2002; 1766–1836.

- J. Gaventa . Towards participatory governance: Assessing the transformative possibilities. S. Hickey , G. Mohan . Participation: From Tyranny to Transformation?. 2004; Zed Books: London

- A. Gilbert . The Latin American City. 1998; Latin America Bureau: New York, NY

- S. Goldsmith , W. Eggers . Governing by Network: The New Shape of the Public Sector. 2004; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC

- C. Graham . Private markets for public goods. 1998; The Brooking Institution Press: Washington, DC

- M. Granovetter . Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology. 34(2): 1985; 481–510.

- B. Hayes . Follow the money. American Scientist. 90 2002; 400–405.

- P. Healey . The communicative turn in planning theory and its implications for spatial strategy formations. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design. 23(2): 1996; 217–234.

- P. Healey . Collaborative planning: Shaping places in fragmented societies. 1997; UBC Press: Vancouver

- R. Hebdon , P. Jalette . The restructuring of municipal services: A Canada – United States comparison. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy. 26(1): 2008; 144–158.

- A. Hefetz , M.E. Warner . Privatization and its reverse: Explaining the dynamics of the government contracting process. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 14(2): 2004; 171–190.

- A. Hefetz , M.E. Warner . Beyond the market vs. planning dichotomy: Understanding privatisation and its reverse in US cities. Local Government Studies. 33(4): 2007; 555–572.

- M. Hipp , M. Warner . Market forces for the unemployed? Training vouchers in Germany and the U.S. Social Policy and Administration. 42(1): 2007; 77–101.

- W.Z. Hirsch . Contracting out by urban governments—a review. Urban Affairs Review. 30(3): 1995; 458–472.

- G.A. Hodge . Privatization: An international review of performance. 2000; Westview Press: Boulder, Colo

- N. Holstrom , R. Smith . The necessity of gangster capitalism: Primitive accumulation in Russia and China. Monthly Review. February 2000; 1–15.

- Hood, C. (1991). A public management for all seasons? Public Administration, 69, Spring, 3–19..

- J. Innes . Planning theory’s emerging paradigm: Communicative action and interactive practice. Journal of Planning Education and Research. 14 1995; 183–191.

- R.M. Kelly . An inclusive democratic polity, representative bureaucracies, and the new public management. Public Administration Review. 58(8): 1998; 201–208.

- Y.K. Kodrzycki . Privatization of local public services: Lessons for New England. New England Economic Review. 1994; 31–46.

- B. Kohl . Privatization Bolivian style: A cautionary tale. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 28(4): 2004; 893–908.

- N. Krumholz , P. Clavel . Reinventing cities: Equity planners tell their stories. 1994; Temple University Press: Philadelphia

- Local Government New Zealand . The Local Government Act of 2002: An overview. 2003; LGNZ: Wellington, NZ

- J.R. Logan , H.L. Molotch . Urban fortunes: The political economy of place. 1987; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA

- D. Lowery . Consumer overeignty and quasi-market failure. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 8(2): 1998; 137–172.

- D. Lowery . A transactions costs model of metropolitan governance: Allocation versus redistribution in urban America. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 10(1): 2000; 49–78.

- S. Martin . The modernization of UK local government: Markets, managers monitors and mixed fortunes. Public Management Review. 4(3): 2002; 291–307.

- P.M. McGuirk . Situating communicative planning theory: Context, power, and knowledge. Environment and Planning A. 33(2): 2001; 195–217.

- F. Miraftab . Neoliberalism and casualization of public sector services: The case of waste collection services in Cape Town, South Africa. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 28(4): 2004; 874–892.

- M. Meyers , L. Jordan . Choice and accommodation in parental child care decisions. Community Development: The Journal of the Community Development Society. 37(2): 2006; 53–70.

- M.H. Moore . Creating public value: Strategic management in government. 1995; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MS

- J. Nalbandian . Facilitating community, enabling democracy: New roles for local government managers. Public Administration Review. 59(3): 1999; 187–197.

- J. Nalbandian . Professionals and the conflicting forces of administrative modernization and civic engagement. American Review of Public Administration. 35(4): 2005; 311–326.

- V. Nee . The role of the state in making a market economy. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics. 156 2000; 64–68.

- D. North . Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. 1990; Cambridge Univ. Press: New York

- D.E. Osborne , T. Gaebler . Reinventing government: How the entrepreneurial spirit is transforming the public sector. 1992; Addison–Wesley: Reading, MA

- D.E. Osborne , P. Plastrick . Banishing bureaucracy. 1997; Addison–Wesley: Reading, MA

- J.R. Pack . Privatization and cost reduction. Policy Sciences. 11(2): 1989; 1–25.

- K. Polanyi . The great transformation. 1944; Beacon Press: Boston

- W. Potapchuck , J. Crocker , W. Schechter . The transformative power of governance. 1998; Program for Community Problem Solving: Washington, DC

- J. Prager . Contracting out government services: Lessons from the private sector. Public Administration Review. 54(2): 1994; 176–184.

- A. Przeworski . Democracy and the market: Political and economic reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America. 1991; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge

- K.M. Reardon . Promoting community development through empowerment planning in East St. Louis, Illinois. W.D. Keating , N. Krumholz . America’s poorest urban neighborhoods: Urban policy and planning. 1999; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oak, CA 124–139.

- T. Sager . Positive theory of planning: The social choice approach. Environment and Planning A. 33(4): 2001; 629–647.

- T. Sager . Democratic planning and social choice dilemmas: Prelude to institutional planning theory. 2002; Ashgate: Aldershot, Hampshire, England; Burlington, VT

- T. Sager . Deliberative planning and decision making: An impossibility result. Journal of Planning Education and Research. 21(4): 2002; 367–378.

- L. Salamon . The new governance and the tools of public action: An introduction. The tools of government: A guide to the new governance. 2002; Oxford University Press: Oxford, New York pp. 1–47.

- E.S. Savas . Privatization: The key to better government. 1987; Chatham House Publishers: Chatham, NJ

- H.E. Schamis . Re-forming the state: The politics of privatization in Latin America and Europe. 2002; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI

- E. Sclar . You don’t always get what you pay for: The economics of privatization. 2000; Cornell University Press: Ithaca

- P. Starr . The limits of privatization. 1987; Economic Policy Institute: Washington, DC

- S. Szymanski . The Impact of compulsory competitive tendering on refuse collection services. Fiscal Studies. 17(3): 1996; 1–19.

- S. Szymanski , S. Wilkins . Cheap rubbish? Competitive tendering and contracting out in refuse collection. Fiscal Studies. 14(3): 1993; 109–130.

- C.M. Tiebout . A pure theory of local expenditures. Journal of Political Economy. 64(5): 1956; 416–424.

- D.D. Troutt . Ghettoes made easy: The metamarket/antimarket dichotomy and the legal challenges of inner-city economic development. Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review. 35(2): 2000; 427–507.

- M.E. Warner . Market-based governance and the challenge for rural governments: U.S. trends. Social Policy and Administration: An International Journal of Policy and Research. 40(6): 2006; 612–631.

- Warner, M. E. (2006b). Inter-municipal cooperation in the U.S: A regional governance solution? Urban Public Economics Review/Revista de Economia Pública Urbana, 7, 132–151. http://government.cce.cornell.edu/doc/pdf/UPER6artWARNER.pdf..

- M.E. Warner , G. Bel . Competition or monopoly? Comparing US and Spanish privatization. Public Administration: An International Quarterly. 86(3): 2008; 723–725.

- M.E. Warner , C.W. Daugherty . Promoting the ‘civic’ in entrepreneurship: The case of rural Slovakia. Journal of the Community Development Society. 35(1): 2004; 117–134.

- M.E. Warner , R. Hebdon . Local government restructuring: Privatization and its alternatives. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 20(2): 2001; 315–336.

- M.E. Warner , A. Hefetz . Applying market solutions to public services: An assessment of efficiency, equity and voice. Urban Affairs Review. 38(1): 2002; 70–89.

- M.E. Warner , A. Hefetz . Rural–urban differences in privatization: Limits to the competitive state. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy. 21(5): 2003; 703–718.

- M.E. Warner , A. Hefetz . Pragmatism over politics: Alternative service delivery in local government, 1992–2002. The Municipal Yearbook 2004. 2004; International City County Management Association: Washington, DC pp. 8–16.

- M.E. Warner , A. Hefetz . Managing markets for public service: The role of mixed public/private delivery of city services. Public Administration Review. 68(1): 2008; 150–161.

- M.E. Warner , J.E. Pratt . Spatial diversity in local government revenue effort under decentralization: A neural network approach. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy. 23(5): 2005; 657–677.

- C.J. Webster . Public choice, Pigouvian and Coasian planning theory. Urban Studies. 35(1): 1998; 53–75.

- C.J. Webster , L.W.C. Lai . Property rights, planning and markets: Managing spontaneous cities. 2003; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK; Northhampton, MA