Abstract

The paper presents results of an online survey among academics on the existing conceptions of civil society as related to the EU. The study reveals that there exist two independent conceptions of civil society, one of which sees civil society as composed of civil society organisations articulating and representing the interests of a constituency, the other locates civil society in the sphere of social interaction. These different conceptions as well as preferences for specific definitions of civil society impact on the classification of general interest groups, trade unions, professional organisations and business interest associations as CSO. As it is only the first, encompassing conception of civil society which is easily incorporated in a governance approach and well in line with the principles of representative democracy conception of civil society as promulgated by the European Commission while scholars lining up with the social sphere approach have difficulties to see EU associations as part of Europe's civil society, the conclusion is that the distinction between the two conceptions of civil society should be brought out more clearly.

1 Introduction

‘Civil society’ is a buzzword in the EU and a vast array of organisations claim to represent Europe's civil society. Nevertheless, academics and practitioners find it difficult to agree which associations rightly belong to this category. In order to map the existing conceptions of civil society as related to the EU, we conducted an online survey among colleagues from academia who have published on civil society. We choose from the literature four different definitions and asked which definition comes closest to each survey participant's understanding of civil society. Furthermore, survey participants were given a list of EU-level associations and were asked to tell us which they consider to represent civil society. The list is a sample taken from more than 300 associations which participated in “online consultations with civil society” organised by the General Directorate (GD) Health and Consumer Protection in past years. We first asked to identify the civil society organisations (CSO) before we asked for an assessment of the definitions because we wanted to obtain a reaction not filtered by theoretical reflections.

From the 160 academics who were invited by email, 100 participated in the survey. The online survey took place between 15th January and 15th February 2008.

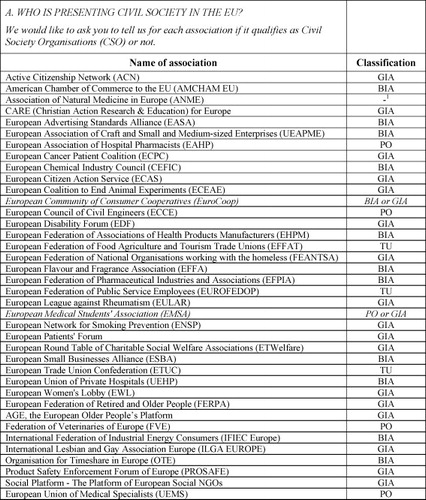

1.1 Which associations qualify as civil society organisation (CSO)?

The online-survey listed 38 EU-level associations (see Fig. 1) and we asked survey participants to tell us for each association “if it qualifies as civil society organisation or not”. For our list we started with a random selection of 60 associations out of the above mentioned 300 associations which responded to the Commission's invitation to consult with “civil society”. All these associations claim in one way or another to represent civil society. In spite of the fact that consultations mostly concern specific policy issues und thus mainly attract associations with corresponding thematic orientations, the array of interests and the types of organisations in our sample correspond to the usual mix. Associations range from narrow specific to broader encompassing interests and from advocacy groups to member based umbrella organisations. In a second step we checked whether or not the name of the association gave a clear indication as to the constituency and the purpose it was representing. Ambivalent cases as well as all associations representing public actors (such as municipalities or regions) were deleted from the original list. All remaining associations fulfil the criteria of being voluntary, not-for-profit, organised at EU level and representing non-state actors. Furthermore, we made sure that the list includes different kinds of associations in terms of purpose and constituency. The reason is that conceptions of civil society differ with respect to the inclusion or exclusion of self-interested actors.

Some authors include associations representing the economic and/or social interests of their members (such as business, professionals or employees) but would make a differentiation with respect to constituency; trade unions and also professional associations are more often regarded as belonging to the family of civil society organisations than associations of trade or industry. Other authors would exclude all but those associations which represent “general interests”. An interest qualifies as a “general interest” when it is in the pursuit of a public good (such as social stability, environmental sustainability) or a universal value (such as human rights).

For our analysis (not for the survey itself) we classified the 38 associations with respect to purpose and constituency and came up with four types of associations:

| • | Business interest associations (BIA). | ||||

| • | Trade unions (TU). | ||||

| • | Professional organisations (PO). | ||||

| • | General interest groups (GIA). | ||||

From the literature we can deduce that GIA are in the main considered as qualifying for CSO, whereas considerable dissent exists with regard to producer interests (BIA). Similarly, trade unions (TU) and professional organisations (PO) are often not considered to be part of civil society. This differentiation is largely confirmed by our survey data.

1.2 General interest associations (GIA)

The survey participants with only few exceptions classified GIA as CSO.Footnote1 On average the associations which we had defined as GIA qualify as CSO for 84.53 percent of the survey participants (for the following see ). And those survey participants, who do not classify a listed GIA as CSO rather leave it open because the GIA is unknown to them (do not know: 12.00 percent) than exclude it from the group of CSO (3.47 percent).

Table 1 Classification of associations as civil society organisations (CSO) in %.

1.3 Trade unions (TU) and professional organisations (PO)

The situation with trade unions and professional organisations is quite different (see ). The “survey community” is split with regard to whether trade unions and professional organisations can be considered as CSO, although trade unions clearly have a larger community of supporters than professional organisations, whose status is unclear to a fifth (see below) of the survey participants. 56.33 percent of the survey participants say that the listed trade unions qualify as CSO, and even fewer respondents, namely 47.75 percent, include professional organisations into this category. An equal number of respondents exclude PO and TU from their list of CSO (TU: 29.00 percent; PO: 31.50 percent), while there is a marked differences concerning the undecided (TU: 14.67 percent; PO 20.75 percent).

1.4 Business interest associations (BIA)

BIA have the lowest support for qualifying as CSO (see ). On average, BIA are only included by 41.20 percent of the survey-participants. More than a third of the survey participants state that the listed BIA do not qualify as CSO (35.70 percent) and the rest is undecided with regard to the status of BIA (23.10 percent).

2 Civil society: conceptions and preferred views

2.1 Conceptions of civil society

Civil society is a widely used concept that carries many and often even contradictory connotations. The image of civil society varies with context and normative theoretical orientation. Whereas EU institutions put civil society and “organised civil society” in the context of EU governance, political theorists rather see it from the perspective of normative theories of democracy. Proponents of liberal democracy put emphasis on the principle of equal and effective representation and thus would call for a pluralist and encompassing composition of civil society. Advocates of deliberative democracy like Habermas consider civil society as a key component in a discursive process of democratic will-formation and place civil society associations in relation to the emergence of a public sphere. In a sociological approach civil society is of interest as a self-constituting separate sphere that serves the differentiation and self-government of society. Although the concept of civil society is mostly associated with positive values, some authors take the concept even a step further and propagate a distinct communitarian understanding of civil society which incarnates such values as solidarity and the active engagement for the public good.

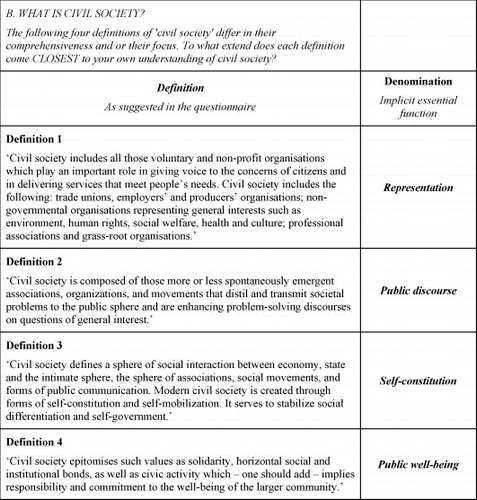

Our online survey suggested four different definitions that were taken from the literature and represent distinct theoretical approaches (Fig. 2). On purpose we did not give any references to authors and schools of thought. We only attracted the respondents’ attention to the difference in comprehensiveness and focus of the definitions and asked the survey participants to indicate on a scale from one to seven to what extend the respective definition comes close to their own understanding of civil society.Footnote2

2.2 Definitions

Definition 1 clearly reflects a governance approach and makes full sense in a concept of representative democracy where, for the sake of efficient and legitimate policy-making, political pluralism is an asset. It is an all-inclusive approach that has been suggested by the European Commission in the White Paper on European GovernanceFootnote3 and also by the European CitationEconomic and Social Committee (1999, p. 30). In order to find a short and to the point phrase for the individual definitions we distilled the main function attributed to civil society. In our judgement ‘representation’ is at the core of this definition.

Definition 2 is taken from the writings of Jürgen HabermasFootnote4 and relates civil society to the concept of deliberative democracy. Civil society provides the societal infrastructure for the well functioning of the public sphere which is at the heart of a reason based democracy. Deliberations in the public sphere raise and re-interpret societal concerns, bring up new themes and issues for governance and generate good reasons for appropriate decision-making. Habermas conceptualizes the public sphere as a “communication structure rooted in the lifeworld through the associational network of civil society” (CitationHabermas, 1996, p. 359). Implicitly, this distinguishes civil society organisations from interest groups which lobby in favour of the material interests of their own members. Accordingly, ‘public discourse’ characterises quite well the essential function of civil society in this concept.

Definition 3 is a slightly abbreviated and edited quote from CitationCohen and Arato (1992) who suggested it as a working definition to start with. By distinguishing civil society from political society and attributing the latter a mediating role between civil society and state the authors put civil society at distance from the sphere of politics. They concede civil society a political role but in their view it is “inevitably diffuse and inefficient”. Rather, civil society represents one dimension of the sociological world: “(…) civil society refers to the structures of socialisation, association, and organised forms of communication of the lifeworld to the extent that these are institutionalized or are in the process of being institutionalized” (CitationCohen & Arato, 1992, p. x). The abbreviated quote certainly does not do justice to the complex approach developed by Cohen and Andrew but for the sake of distinguishing it from Habermas we choose to emphasise the closeness to the lifeworld and the “self-creative dimension”. ‘Self-constitution’ represents the feature we wanted to convey with this definition.

Definition 4 reflects a communitarian approach to civil society in the tradition of CitationBarber (1984) and CitationTaylor (1985) though we quote two authors who are inspired by the Polish sociologist Andrzej Sicinski.Footnote5 The communitarian position underscores the significance of active citizenship, civic virtues and the commitment to the community of citizens as a necessary societal condition for democracy. It is a value laden concept associating civil society with a commitment to social coherence built on solidarity and reciprocity. In this concept associations are rather an arena for civic participation than agents of representation. To put it in a nutshell: the essential function attributed to civil society is to serve the ‘public well-being’.

2.3 Conceptual preferences

Considering the different connotations of civil society we were interested to see whether the research community indeed is divided on the concept of civil society and/or whether there exists a clear ranking of various conceptions. The responses to the four definitions do not give a clear-cut picture, but from the figures we may conclude that in general civil society is more closely related to the sphere of society than to the sphere of politics. When comparing the average ratings, we find that respondents prefer the “self-constitution” definition to the other definitions (see ).

Table 2 The four definitions of civil society: descriptive statistics.

Furthermore, we were interested if the survey participants might see the four definitions as describing complementary components of a broader image of civil society or if they draw a distinguishing line between different understandings of civil society. The statistical analysis suggests a distinction between the “representation” definition on the one hand and the other three definitions of civil society on the other hand (see ).

Table 3 Correlations between the various definitions of civil society.

When examining the correlation between the agreement scores (see ) it becomes evident that there are two conceptions of civil society, which are not mutually exclusive but complementary, as it is also confirmed by factor analysis (see ).

Table 4 Principal component analysis of civil society definitions.

One conception is captured by the “representation” definition which puts emphasize on giving voice and on delivering services by CSO. This conception fits well with a “governance approach” to civil society. The other conception is reflecting a “social sphere approach”. This is the common denominator of the three other definitions which bring the element of social interaction to the fore and see it in a functional relation to society—be it by distilling and transmitting societal problems to the public sphere (‘public discourse’ definition), be it by stabilizing societal differentiation and self-government (‘self-constitution’ definition), or by promoting value based civic activities in the interest of the larger community (‘public well-being’ definition).

3 Conceptions of civil society and the qualification of an association as CSO

When examining the relationship between the conceptual understanding of civil society and the qualification of different types of associations as CSO we gain a deeper insight with respect to the meaning of both. Again we see that there is a dividing line between the representative image and the other conceptions of civil society and we see distinct patterns in the evaluation of different kinds of EU associations.

The agreement scores for the four definitions were correlated with the evaluation whether a certain organisation qualifies a CSO or not (see ). A positive correlation coefficient indicates that stronger agreement with a definition increases the probability that the respondent will classify the organisation as CSO (and vice versa). Significant correlations are put in bold.

Table 5 Correlations between civil society definitions and associations qualifying as civil society organisations.

When we compare the correlations referring to the four civil society definitions we find some characteristic features regarding the relationship between the definition supported and the associations classified as CSO. Respondents who strongly agree with the representative understanding of civil society (definition 1) quite obviously do not have difficulties to qualify most of the listed associations as civil society organisations. This is in striking contrast with the correlation results of the other definitions. In general, survey participants who agree more strongly with any of the other definitions less often categorise a particular association as CSO. This tendency is most pronounced among those scholars who associate civil society with values of solidarity and civic activities promoting the well-being of the larger community (‘public well-being’ definition). In the majority of cases the respondents reject the idea that the listed association might qualify as CSO; all correlations are negative and most of them are statistically significant. The respondents not only exclude business associations, professional associations and trade unions but also general interest associations, though in the latter case the exclusion is not always statistically significant. Whenever respondents agree more strongly with an understanding of civil society in the tradition of Habermas (‘public discourse’ definition), especially TU and some BIA as well as PO are not classified as CSO. Even though the remaining correlations regarding BIA, PO and TU are statistically not significant it is worthwhile noting that they all correlate negatively with this particular definition. Finally, the assessment of associations acting in the general interest by supporters of the ‘public discourse’ definition is on the whole random and insignificant; the correlation can be positive or negative but in only one case it is statistically significant. The notion of civil society as a sphere of social interaction relating to the self-constitution and self-government of society (‘self-constitution’ definition) is also difficult to reconcile with the world of EU associations. This definition of civil society is particular in so far as it does not produce any significant correlations with the respondents’ assessment of the listed associations. The classification of associations as CSO is random, so obviously respondents supporting the ‘self-constitution’ definition do not have a common concept of what a civil society organisation is.

3.1 The two images of civil society

The correlations listed in underscore that civil society is a contested concept and that the self-ascription of EU associations to represent civil society does not at all meet the unanimous support of scholars working on the subject. Only in a very distinct understanding of civil society do EU associations qualify as CSO, which is expressed in the ‘representation’ definition. Not by chance it is a conception propagated by the EU institutions in the context of the new governance approach. With the publication of the White Paper on European Governance the Commission established openness and participation as core principles of “good European governance” drawing on the contemporary governance debate in the social sciences.Footnote6 Governance builds on the cooperation of public and private actors and calls for the inclusion of “stakeholders” for more efficient and effective policy-making. Hence, in the following years the Commission developed a strategy for the wider involvement of “civil society” both in consultations on EU policies and in the debate on the future of Europe. The pledge to invite all those organisations which play an important role in giving voice to the concerns of citizens pays tribute to the idea of pluralism and the democratic ideal of representation. In this respect the civil society conception in the ‘representation’ definition is distinct from the others: it is all-encompassing and it incorporates the principle of representation.

The correlations support the basic philosophy of the EU concept of civil society. Only those respondents who strongly agree with this definition have no difficulties to qualify all different kinds of associations in our sample as ‘civil society organisations’ – no negative correlations – neither statistical significant nor insignificant – exist. In contrast to all other definitions, this conception correlates positively with all listed EU associations though not always at a statistically significant level. It is worth noting that the statistically significant positive correlations refer to all associations irrespective of the interest and purpose they pursue. Most notably this holds true for all associations which we have identified as representing business interests, trade unions and professional organisations. The assessment of associations which we categorised as representing general interests is less uniform; in only less than half of the cases it is statistically significant that they will be rated as CSO.

The three other definitions put forward in the survey quite obviously correspond to a quite different and for many scholars the only appropriate conception of civil society. As one of our colleagues told us quite bluntly:

“I think the premise behind the questionnaire is wrong: no organisation ‘represents’ civil society, civil society is a space of participation, not representation.” Marlies Glasius, LSE.

In this conception civil society is not a “partner in good governance” and an “input provider for better legislation” but the manifestation of active citizenship and as such “source and promoter of democracy” in defence of political rights (CitationEdler-Wollstein & Kohler-Koch, 2008, p. 200). From a deliberative democracy perspective as expressed in the ‘public discourse’ definition the benchmark for civil society organisations is the openness to general interests, the dedication to take up societal problems and to transmit them into the public discourse. In this perspective it is plausible to expect that only those associations which we qualified as GIA might be evaluated positively. The correlation analysis proves us right in so far as scholars opting for this definition draw a clear line between those associations which are market related and represent the economic or social interests of their members (BIA; PO and TU) and associations expressing general interests. The high support of the ‘public discourse’ definition results in an explicit exclusion of business interests, trade unions and professional organisations from the group of CSO, though not always statistically significant, whereas the majority (yet not all) of GIA correlate positively. It is noteworthy that only in the case of the Social Platform we find a statistically significant positive correlation with the ‘public discourse’ definition.

Definition 4 which attributes civil society post-material values and a commitment to the general well-being is even more distant from the governance concept of civil society. This is well expressed in the correlations which are all negative though not always statistically significant. The message is quite clear: the more pronounced the agreement with the ‘public well-being’ definition, the greater is the tendency not to classify EU associations as CSO. Even though no EU association is seen as being part of civil society, it is noteworthy that the dividing line between associations representing economic and social interests of their members on the one side and general interests on the other shows up. The higher the consent of a respondent with the ‘public well-being’ definition the more likely it is that she or he classifies the first category of associations as not being CSO. With only two exceptionsFootnote7 we find a statistical significant negative correlation between the communitarian conception of civil society and associations representing business, professions and trade unions. With regard to general interest associations the exclusion is less marked; only five out of 18 GIA correlate statistically significant negative with the ‘public well-being’ definition. The correlations with the ‘self-constitution’ definition convey the same tendency but are difficult to interpret since no correlation is statistically significant.

All things considered, the correlations demonstrate that there are two distinct conceptions of civil society and that EU associations only fit in a governance approach to civil society. The correlations also provide evidence that scholars assess different associations differently.

3.2 A differentiated view on EU associations

The indiscriminate qualification of all kinds of EU associations as CSO is unique and it only happens in the correlations with the ‘representation’ definition. Whenever respondents strongly agree with any of the other definitions they are more likely to make a distinction between associations we have categorized as GIA and associations representing the economic and/or social interests of their members. Whereas in the first approach all BIA, TU and PO are classified (statistically significant) as CSO, not a single economic and/or social interest association has been attributed the CSO status in any of the other approaches. The assessment is predominantly negative though not always statistically significant. Respondents who strongly support the communitarian conception are most coherent in excluding both business and professional association, and also trade unions from the list of CSO. It is not surprising that the exclusion of associations such as the American Chamber of Commerce to the EU (AMCHAM EU), the European Chemical Industry Council (CEFIC) or the European Union of Private Hospitals (UEHP) is statistically significant when correlated with the ‘public discourse’ definition and the ‘public well-being’ definition. Correlations are still negative but not statistically significant with regard to business and professional associations such as the European Association of Craft and Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (UEAPME) or the Federation of Veterinaries of Europe (FVE). It is up to speculation if market power and/or the image of pure profit orientation make a difference.

The assessment of the EU trade union associations is quite obviously not in line with the self-perception of the unions. The statement “(t)he CitationETUC's objective is an EU with a strong social dimension that safeguards the well-being of all its citizens”Footnote8 underscores that the European Trade Union Confederation is not only aiming to defend the interests of its members but is also dedicated to work to the benefit of the larger community. Nevertheless, scholars who strongly agree with the ‘public discourse’ definition and the ‘public well-being’ definition are most likely to say that the EU trade union associations do not qualify as CSO; a result that is statistically significant for all TU listed.

The picture is far more complex with regard to general interest associations. Even in the governance approach, which in principle includes all kinds of associations, it is equally likely in the majority of cases that respondents may or may not count a GIA as CSO. Only a minority of those associations which we have defined as GIA have been qualified as CSO at a statistically significant level. Among the respondents who feel more comfortable with the definition of civil society as composed of associations transmitting societal problems to the public sphere (definition 2) the correlation is statistically significant only in the case of the Platform of European Social NGOs. There is an overall tendency to attribute GIA the status of CSO but it is statistically not significant and with some GIA – such as the European Federation of Retired and Older People (FERPA) which has a trade union background and is member of ETUC – there even is a certain probability that they are excluded from the list of CSO.

We can discern certain patterns in the differential treatment of GIA. The majority of those GIA for which agreement with the first definition matters in terms of being statistically significant are market related or welfare oriented. Either the purpose is the regulation of markets as it is the case for the Product Safety Enforcement Forum of Europe (PROSAFE) or they have a mixed membership such as the European League against Rheumatism (EULAR), ranging from scientific societies, national organisations of people with arthritis/rheumatism, to health professionals and finally to 31 pharmaceutical companies. The other listed GIA touch on health and welfare such as the European Round Table of Charitable Social Welfare Associations (ETWelfare) and the Social Platform. Yet another characteristic feature shows up when we compare the general interest associations which qualify significantly as CSO with those that do not. To the first group belong all those associations that are predominantly membership based and can claim to be representative of a large constituency. Consequently the European Federation of Retired and Older People (FERPA) is definitely considered to qualify as CSO whereas its counterpart AGE, the European Older People's Platform is not. FERPA is an umbrella organisation of national pensioners associations which are representing a large number of regional and local groups with a broad individual membership. AGE on the other hand started off with the support of the Commission to bring in both stakeholder interests and expert knowledge represented by charities and care services such as Help the Aged UK or the Age Concern England. It is equally striking that neither advocacy groups such as the European Coalition to End Animal Experiments (ECEAE) nor associations representing the interests of disadvantaged minorities such as the European Federation of National Organisations working with the homeless (FEANTSA) or groups with specific interests such as the International Lesbian and Gay Association Europe (ILGA Europe) or the different patients groups pass the threshold of a significant positive correlation. When a survey participant more strongly agrees with the first definition, she or he will be equally likely to include or exclude the European Women's Lobby (EWL). It is worth mentioning that the same holds true for the Active Citizenship Network (ACN) and the Citation European Citizen Action Service (ECAS). Though the main objective of ACN and ECAS is to give voice to the concerns of citizens, both associations lack a core attribute that would qualify them as CSO: representativeness. CitationActive Citizenship Network (ACN) is a European network of citizens’ organisations promoted by the Italian NGO Cittadinanzattiva; it is based on partnership rather than membership being engaged in projects with variable participants and most projects are co-financed by public funds coming mainly from the European Commission.Footnote9 ECAS is engaged in pushing for transparency and democratic participation in EU governance and proclaims to empower civil society with the European Union. It is not a citizen based organisation but a service provider offering NGOs “supplementing information about EU contacts and funds with training on how to write applications, build partnerships and networks (…)”.Footnote10 Since ACN and ECAS do not meet the requirements of representative interest organisations they do not qualify as CSO in the eyes of those respondents who strongly agree with the governance approach to civil society. Equally, they do not find the support of those scholars who prefer the communitarian approach. The latter are critical of all those associations that proclaim to act in the general interest but have no roots in society and are not active at the grass roots level. Accordingly, ECAS is definitely excluded from the family of CSO when correlated with definition 4.

4 Summary

Based on the four definitions of civil society, two independent underlying conceptions of civil society emerge. The first conception sees civil society as composed of civil society organisations articulating and representing the interests of a constituency and is articulated in definition 1. It is an encompassing conception of civil society including all different kinds of associations in terms of membership and purpose. The interests they represent may be economic or social; they may only take up the concerns of their members or work in the interest of a wider constituency. But it is decisive for a European association to qualify as CSO that it is representative; it has to be membership based and has to embrace a large constituency. Advocacy groups, even when they are acting in the best interest of civil society and are promoting citizens’ rights, do not qualify as CSO. Thus, it is an understanding of civil society which is easily incorporated in a governance approach and well in line with the principles of representative democracy.

The second conception of civil society is expressed in the three other definitions offered in the survey. Albeit slightly different, the deliberative democracy definition, the self-constitution definition, and the communitarian definition represent an understanding that locates civil society in the sphere of social interaction. This conception is difficult to reconcile with a governance approach and, consequently, does not see civil society organisations in their functional relation to the decision-making bodies of the EU. From this perspective the yardstick for qualifying an association as CSO is not the representativeness of the individual organisation but its engagement in civic activities.

Accordingly, the attitude towards a definition impacts on the classification of an organisation as CSO. Scholars agreeing strongly with the first conception accept a plurality of groups as CSO including business interests, trade unions, and professional interests. None of these qualify as CSO in the second conception of civil society. The most interesting case is the classification of those organisations which we have defined as general interest associations. In view of the first conception several associations are deficient in terms of representativeness and therefore their rating is ambivalent. When correlated with the three other definitions, general interest associations fare far better than the economic and social interest groups which are mostly excluded from qualifying as CSO. But with the single exception of the Social Platform none of them made the grade of a civil society organisation when related to any of the three other definitions. Without doubt the communitarian conception of civil society is most rigorous since it is excluding from civil society not just groups aiming at realising economic or social advantages for their membership but is also not accepting that any of the “rights and value based” organisations – as they are classified in the mission statement of the European Citation Civil Society Contact Group Footnote11 – might be eligible as CSO. Since the choice of EU associations listed was limited, it might be premature to draw general conclusions. But it is quite evident that scholars lining up with the social sphere approach have difficulties to see EU associations as part of Europe's civil society.

Hence, the conclusion of this small survey is that the image of civil society as propagated by EU institutions only fits with a very distinct conception of civil society. Consequently, the role attributed to EU associations is a contested issue. When any voluntary, not-for-profit and non-state association active at EU level is labelled “civil society organisation” it will provoke opposition. The expectation that EU groups may benefit from the positive connotations of civil society will not materialise when the classification as CSO is indiscriminate. In order to avoid misunderstandings or, even worse, suspicions as to the democratic intentions of the EU institutions the distinction between the two conceptions of civil society should be brought out more clearly.

Notes

1 As the classification of the European Community of Consumer Cooperatives (EuroCoop) and of the European Medical Students’ Association (EMSA) turned out to be unclear, these two associations are not included in our statistical analysis.

2 For our statistical analysis the original scale from 1 (fully agree) to 7 (do not agree at all) was inversed.

3 The exact wording is as follows: “Civil society plays an important role in giving voice to the concerns of citizens and delivering services that meet people's needs.” The footnote gives a more detailed account: “Civil society includes the following: trade unions and employers’ organisations (social partners); nongovernmental organisations; professional associations; charities; grass-roots organisations; organisations that involve citizens in local and municipal life with a particular contribution from churches and religious communities.” (CitationCommission of the European Communities, 2001, p. 14).

4 The quote from Habermas reads as follows: ‘Civil society is composed of those more or less spontaneously emergent associations, organizations, and movements that, attuned to how societal problems resonate in the private life spheres, distill and transmit such reactions in amplified form to the public sphere. The core of civil society comprises a network of associations that institutionalizes problem-solving discourses on questions of general interest inside the framework of organized public spheres. These ‘discursive designs’ have an egalitarian, open form of organizations that mirrors essential features of the kind of communication around which they crystallize and to which they lend continuity and performance’ (CitationHabermas, 1996, p. 367).

5 The quote is from Dariusz Gawin and Piotr Glinski: “(…) following the Polish sociologist Andrzej Sicinski, we content that civil society epitomises such values as openness (as Popper understood it), horizontal social and institutional bonds, as well as civic activity which – one should add – implies responsibility, solidarity and commitment to the well-being of the larger community.” (CitationGawin & Glinski, 2006, p. 8).

6 The Commission's Governance homepage refers to CitationRhodes (1996, p. 652).

7 The exception are the European Association of Craft and Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (UEAPME) and the Federation of Veterinaries of Europe (FVE).

8 European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC). About us. Retrieved July 15, 2008 from http://www.etuc.org/r/5.

9 See Active Citizenship Network (ATC). About us. Retrieved July 19, 2008 from http://www.activecitizenship.net.

10 European Citizen Action Service (ECAS). About ECAS, Civil Society. Retrieved July 20, 2008 from http://www.ecas-citizens.eu.

11 Civil Society Contact Group. About us, Presentation. Retrieved July 20, 2008 from http://www.act4europe.org.

References

- Active Citizenship Network (ATC). About us. Retrieved July 19, 2008, from http://www.activecitizenship.net/content/view/35/53/, accessed February 20, 2009..

- B.R. Barber . Strong democracy: Participatory politics for a new age. 1984; University of California Press: Berkeley

- Civil Society Contact Group. About us, Presentation. Retrieved July 20, 2008, from http://www.act4europe.org./code/en/default.asp, accessed February 20, 2009..

- L.J. Cohen , A. Arato . Civil society and political theory. 1992; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA

- Commission of the European Communities (2001). European Governance. A White Paper. Brussels: COM (2001) 428 final..

- Economic and Social Committee (1999). The role and contribution of civil society organisations in the building of Europe. Brussels: OJ C329..

- S. Edler-Wollstein , B. Kohler-Koch . It's about participation, stupid. Is it?—Civil society concepts in comparative perspective. B. Jobert , B. Kohler-Koch . Changing images of civil society. From protest to governance. 2008; Routledge: London, New York 195–214.

- European Citizen Action Service (ECAS). About ECAS, Civil Society. Retrieved July 20, 2008 from http://www.ecas-citizens.eu/content/category/7/915/144/, accessed February 20, 2009..

- European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC). About us. Retrieved July 15, 2008 from http://www.etuc.org/r/5, accessed February 20, 2009..

- D. Gawin , P. Glinski . Introduction. D. Gawin , P. Glinski . Civil society in the making. 2006; IFIS Publishers: Warsaw 7–15.

- J. Habermas . Between facts and norms. Contributions to a discourse theory of law and democracy. 1996; Polity Press: Cambridge

- R.A.W. Rhodes . The new governance: Governing without government. Political Studies. 44(4): 1996; 652–667.

- C. Taylor . Alternative futures: Legitimacy, identity, and alienation in late twentieth century Canada. A. Cairns , C. Williams . Constitutionalism, citizenship, and society in Canada. 1985; University of Toronto Press: Toronto