This thematic edition of Policy & Society contains a set of seven articles about transport infrastructure policy in the People’s Republic of China. Though they all revolve around this central topic, they cover different facets, such as the influence of Confucian values on decision-making, its impact on macro-economic development and regional distribution, power relations within Public Private Partnerships, organizational and contractual relations in subway construction, the duration of decision-making processes and the viability of developing Transit Oriented Development in Chinese cities. This first contribution will sketch a general overview of two driving forces behind China’s motorization process (economic growth and urbanization), what the impact has been on the expansion of the transport networks and hubs and what social and policy problems Chinese authorities currently have to tackle as a consequence of these developments. It ends with a small prospectus of the other six contributions to this volume.

1 Twin driving forces of transport development in China

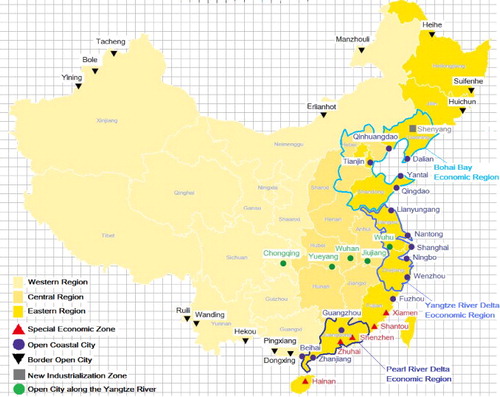

1.1 Economic growth

As it has transformed from a centrally planned economy to a market economy since the late 1970s with the “opening-up” policies brought forward by Deng Xiaoping, China has experienced rapid economic growth of almost 10% per annum on average (CitationNational Bureau of Statistics of China, 2009; OECD, 2010). Over the past three decades, China has regarded economic growth as a national priority to improve human welfare and eradicate poverty, while GDP as a primary economic growth indicator has been extensively used to assess the success of national or regional economic policies (CitationWen & Chen, 2008). National GDP increased from 455 to 39,798 billion RMB between 1980 and 2010. In the same period, per capita income rose from 463 to 29,940 RMB. Given the impressive growth performance, three globalized regional economies, those of the Pearl River Delta, the Yangtze River Delta and the Bohai Rim Bay Area, have continued to outperform all other regions in China (Fig. 1 ). These three regions, which together account for only 1.6% of China’s total land area, have contributed 12.3%, 27.4% and 26.3% respectively to China’s national GDP in recent years on average (CitationTuan, Ng et al., 2009).

Capital investment (including domestic investment and foreign direct investment), international trade and capital accumulation are three key determinants for China’s rapid economic growth (CitationTuan et al., 2009; Whalley & Xin, 2010). China’s institutional reforms have fundamentally transformed the economic system through introducing decentralization and privatization: the transfer of economic-decision power from the central government to local authorities and the permission of (foreign) private investment in public infrastructures, which provides significant incentive for local authorities to build and expand the fixed assets of their localities with widening financial sources. This has resulted in large scale fixed-asset investment over the past three decades. According to the official statistics, fixed-asset investment relative to GDP rose from 20.0% in 1980 to 69.9% in 2010. On the other hand, the opening-up development strategy, together with preferential policies for foreign investors and outward-looking industries, has vigorously promoted China’s absorption of foreign direct investment (FDI) and international trade. Since the restriction on FDI inflows into China was removed in 1979 and a new foreign investment law was enacted in 1984, China has received a large amount of FDI flows and become the largest FDI recipient among developing countries. Usually, the FDI inflows are realized by establishing foreign invested enterprises (FIEs) in China, which are often joint ventures between foreign companies and Chinese enterprises. These FIEs account for about 20–40% of China’s GDP in recent years and without them China’s overall GDP growth rate could have been around 3.4% points lower (CitationWhalley & Xin, 2010). Furthermore, international trade has produced a continuously growing trade surplus since 1978.

1.2 Urban expansion

China’s remarkable economic growth has been concomitant with an almost equally rapid growth in urban expansion (CitationDeng, Huang et al., 2008; Ho & Lin, 2004; Lichtenberg & Ding, 2009; Lin, 2001, 2007; Zhou & Ma, 2000). Urban expansion, on the one hand, refers to the situation of spreading spatially outwards from the city to its outskirts, and on the other hand, it refers to the process of in situ urbanization of rural areas, i.e. the gradual abandonment of agriculture as a way of life in favor of work in rural industries (CitationFriedmann, 2005; Yusuf & Saich, 2008). On a national scale, China’s urban land area increased by 817,000 ha in the period of 1990–2000 and sprawled even faster in the period of 2001–2005 by 849,400 ha (CitationHan, 2010; Lin & Ho, 2005). And the most significant expansion often occurred in coastal city-regions (e.g. Liaoning, Shandong, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, etc.), especially in those large cities whose urban centers are surrounded by secondary cities and rural townships (CitationDeng & Huang, 2004; Wei & Zhao, 2009). On a local scale, individual cities have been adding huge amounts of suburban land to their already urbanized areas. For instance, large cities such as Beijing and Guangzhou experienced growth in urban land use of 30–50% in the past 15 years (CitationHan, 2010; Wu, Li et al., 2006; Yu & Ng, 2007). City agglomerations including the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region and the Pearl River Delta region expanded more than 70% in the 1990s (CitationLi & Yeh, 2004; Tan, Li et al., 2005). In addition, small cities expanded even more rapidly than the large ones. In the Beijing–Tianjin–Tangshan region the urban area of small cities increased by 80% in the same decade (CitationTan et al., 2005).

One widely discussed reason leading to the urban expansion in China is the growth of the urban population (CitationLiu, Zhan et al., 2005; Tan et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2006). From 1978 to 2010, China’s urban population increased from about 172 million to 666 million and the level of urbanization rose from 18% to 49.7% (CitationHan, 2010). Because of the growing difference in living standards between urban and rural areas, the pressure of urbanization is bound to increase further in the future. Urban expansion is therefore taking place in order to accommodate this population growth. Similarly, the economic growth and changes in the industrial structure naturally extend urban activities to the peripheral areas, and make rural areas industrialized. In addition, the rapid urban expansion is also a result of local government’s policy for economic development. New projects such as industrial parks in the urban fringe areas reflect the intention of the local government to promote regional economic growth by constructing infrastructures and setting up ancillary facilities to improve the competitive edge of the locality and attract outside investors (CitationDeng & Huang, 2004; Wu, Xu et al., 2007).

Such urban expansion necessitates changes in land use in Chinese cities (CitationLichtenberg & Ding, 2009; Lin, 2002; Wei & Zhao, 2009; Yang & Gakenheimer, 2007). While expanding outward, cities do not simply replicate their old fabrics in the new areas: fundamental structural transformation takes place. Traditionally, the pre-reform urban settlement in China included state and collectively owned enterprises that contained their own housing and commercial facilities along with their production activities. With the advent of the land and housing reforms introduced in early 1980s, the urban fabric has been altered in many different ways. Most evidently, many state-owned enterprises have moved their production activities to new suburbs while leaving the employees still living in the same localities to enjoy various urban amenities. And in most cases, new enterprises no longer stick to the traditional model of mixing workplace and residence. Housing supply has been subjected to the market mechanism. In addition, the centers of Chinese cities, formerly occupied by working class families, are transferred to business offices, retail stores and the governmental sector constituting Central Business Districts (CBDs). And households seek suburban locations with lower densities, less traffic and noise, and larger, more modern housing. Furthermore, when urban expansion is limited by urban boundaries set by the Chinese central government, Chinese cities start to develop anchor-institutions and satellite communities as new development zones which are connected with inter-regional railways or expressways. Additionally, the evolution of land use in large Chinese cities is towards a multi-centered city layout in order to avoid high traffic density in the urban core.

China’s staggering developments in terms of economic growth and urban expansion have far-reaching impact on and pose challenges for its transport sector. This mainly refers to the ever growing traffic demand from individual users and the business sector, requiring constant network construction and expansion and involves almost countless amounts of land and funding. In the next section, we present the state-of-the-art knowledge on transport infrastructure development under these twin forces.

2 Transport infrastructure development in China

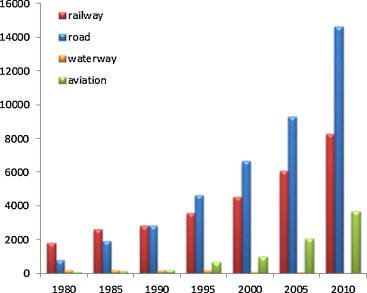

2.1 Traffic flows and private car ownership

Fig. 2 shows that almost all the transport modes have experienced rapid growth in passenger traffic demand from 1980 to 2010 after China’s economic reforms. The traffic flows concentrated on railways and roads, while the trend of road transport has exceeded rail since 1995. In addition, the volume of passengers who traveled by air in recent years is also increasing, given that more Chinese can now afford air travel with higher personal incomes, and under its economic boom an increasing number of foreign tourists and business travelers come to the country. In contrast, less and less people travel by ship because of the relatively low accessibility of inland waterways and long travel times. Therefore, over the past 30 years a tremendous transition took place among the transport modes in terms of their market shares. As we can see in , the share of railway transport for passengers has fallen by 29%, while the share of roads has increased roughly by 23%. In the same period, the share of air transport for passengers increased from 2% to 13.8%, and the share of waterway transport declined from 6% to 0.2%.

Table 1 Transitions of market shares of different transport modes (1980–2010).

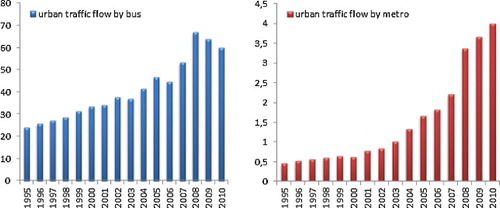

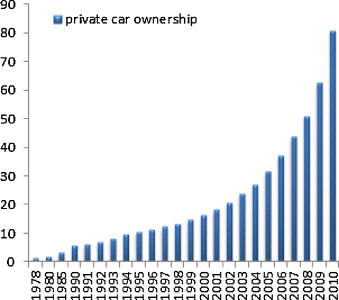

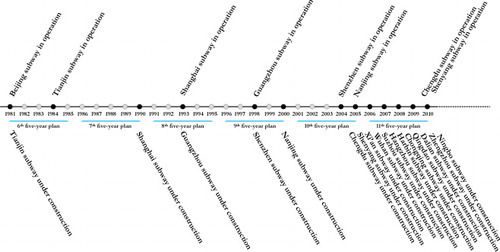

Apart from the long-distance inter-city transport, Fig. 3 shows that the numbers of passengers traveling with the urban bus system and urban metro system also experienced steady growth in the past decade. Passenger numbers travelling by bus increased from 24.6 billion people in 1995 to about 60 billion in 2010, while in the same period passengers using the metro system for trips grew from 0.45 to around 4 billion. Since 2000 urban subways and light rail received massive investments and the total metro length in the whole country reached 1469 km in late 2011. The growth rate of passenger flows by metro exceeded that of buses. However, the increase in the traffic flows by bus and metro does not imply that public transit enjoys a higher modal split relative to private vehicles. Rising per capita income among citizens in China and removing the restrictions imposed by the Chinese government on private car ownership have already led to a highly problematic level of motorization. During 1985–2010 the private car ownership in China increased from 284,900 to 86,060,000 (Fig. 4 ). As a result, mobility depending on automobiles in large Chinese cities accounts for more than 60% compared with the mobility by public transit.

2.2 Investments

shows the status of investment in transport infrastructures in China from 2001 to 2009, and we can see that the scale of the investment shows a massive increase from 243.2 billion RMB in 2001 to 2327.1 billion RMB in 2009. Grouped by mode, a majority of the investment was spent on road and railway constructions while only a small part was invested on urban, air and waterway transport. If grouped by different sources of financing, total investment from the fiscal budget of the central government ranged from 18.3% to 30.4%, and the remaining part came from local governments that may use their local fiscal budget, obtain loans from banks or otherwise attract private capital. When differentiating the investment by ownership, we can see that more than 90% of the investment was from public sources, only around 4–6% was private and a very tiny part from collective sources.

Table 2 Investments in transport infrastructures (2001–2009).

3 Passenger transport modes and their plans

3.1 Roads

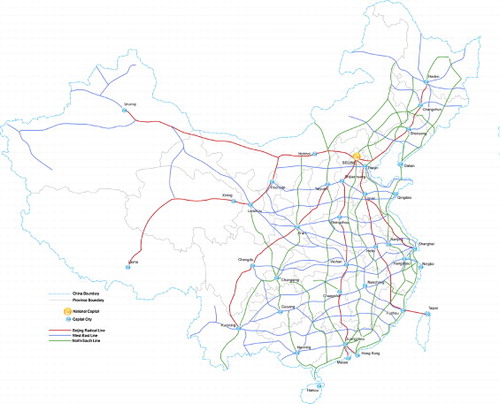

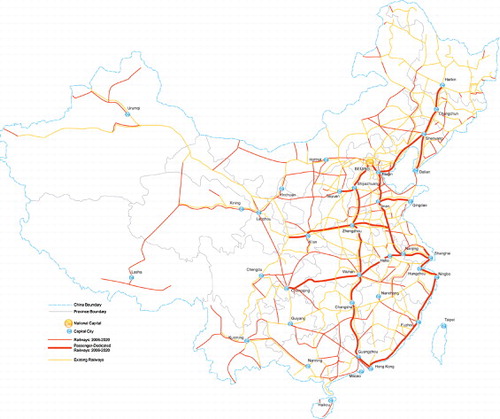

Since the mid-1980s, China has invested massively in road infrastructure. The resulting expansion of the road network, has contributed greatly to, and has also been strongly stimulated by, China’s continuing economic development and the reduction of rural poverty (CitationFan & Chan-Kang, 2008). By the end of 2009, the total length of the road network was about 3,860,800 km, of which 65,100 km are expressways, compared with a figure of 1,698,000 km in total and 19,437 km for expressways in 2001. However, relative to the breadth and length of China’s geographical area and its large population size, its road network still ranks among the sparsest in the world in terms of density and coverage. Focusing only on expressways, the fast construction and expansion originated from the first approved “National Trunk Road System Plan” in the late 1990s. The plan was originally designed for a 35,000-km network including 5 north-south expressways and 7 east-west expressways. And the estimated cost was 1200 billion RMB. By the end of 2004, 97% of the planned projects, roughly 34,288 km, were completed. However, driven by the continuously rising traffic demand for roads, the Chinese central government expanded the existing plan into a “7918 Expressway Network Plan” in late 2004, to build 7 Beijing radials, 9 north-south expressways and 18 east-west expressways, totaling 85,000 km (Fig. 5 ). The completion date is scheduled in 2020 and the total estimated cost is 2 trillion RMB. Currently, more than 60,300 km have been completed.

3.2 Railways

Railways are essential to China’s economic development and social cohesion, and railway transport is still the most commonly used and dominant mode for the movement of both passengers and freight in large volumes and at long distances. The length of railways in operation has increased from some 49,900 km in 1980 to about 85,500 km in 2009. This expansion of the railway network speeded up in recent years because of the approval of the “Mid- and Long-term Railway Network Plan” in 2004 (Fig. 6 ). Projects in the plan are expected to be completed in 2020 when the total length of railways in operation would reach roughly 100,000 km. In addition to network expansion, the main goals of this plan are to construct 12,000 km high-speed passenger rails as well as to upgrade 50% of the existing lines to double-tracked and electrified lines. Until the end of 2010, China has built around 8000 km high-speed lines that are equipped with new controlling and signaling systems, and with the help of foreign technology China has developed high-speed trains with a maximum operating speed of 486 km/h. Further, in this plan 16,000-km new lines are planned in Western China.

3.3 Airports

The global air transport has been undergoing waves of change in the last 30 years as a result of deregulation, liberalization and commercialization. Over the same period, air transport in China has also been undergoing significant transformation following the “opening-up” policies since 1980. In 1980, passengers and freight handled at the country’s airports were only 3.43 million passengers and 0.089 million tons, while the figure in 2009 has risen to 230.52 million and 4.5 million, respectively. Such rapid growth in air traffic volumes of passengers and freight have been partially a result of the increase in citizen income, leading to an increase in affordability of air passenger transport, and the trend toward globalization, in the context of which China has become a major manufacturing center. There has been growing demand for air cargo services as well. China’s airport infrastructure has markedly improved. Between 1990 and 2009, the Chinese governments at all levels jointly invested 300.35 billion RMB in constructing and upgrading airports. By 2009 China has built 158 civil airports with a density of 1.53 per 100,000 square kilometers. There are 31 international airports, of which 26 have runways of at least 1800 m and a capability of handling B747 aircraft of 52–60 m wingspan for takeoff, as well as more than 121 airports that could accommodate B737s. All municipalities, provincial capitals and autonomous regions, coastal and major tourist cities have modern airports. In addition, some border areas, minority regions and areas with poor ground transport infrastructures also have airports.

3.4 Urban (rapid) bus and rail transit

Urban transit systems play an increasingly important role in meeting citizens’ transport needs within urban areas as cities grow in China. And among the strategies being pursued to head off rising traffic congestion and worsening environmental conditions huge investments in urban rail systems in Chinese metropolises have been vital. Compared to 1980 when urban rail lines could rarely be found in Chinese cities, the total length of urban rail systems in 2009 had reached 999 km (Fig. 7 ). And bus transit lines have also been extended from 5979 km in 1995 to 208,250 km in 2009. In addition, the urban trips by Chinese citizens have also increased from some 3.7 billion in 1995 to around 70 billion in 2009. Such an increase in urban traffic demand justifies high-capacity urban rail investments. Urban rail systems are currently found in 8 mainland Chinese cities. Plans call for extending and upgrading existing rail systems and building new ones in 15 other Chinese cities. Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) systems are also being built or expanded in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Shenyang, Chengdu, Xi’an and Kunming. The cities of Tianjin and Dalian also operate streetcars on city center streets.

3.5 Problems in the transport sector in China

Going along with the twin developments of economic growth and urban expansion, China has experienced rapid transport infrastructure development in recent years. Such development, in terms of network expansion, undeniably has positive implications for spatial accessibility at both the regional and the local levels. This has been demonstrated by various researchers. CitationLi and Shum (2001) examined the 7918 expressway projects and their impact on the accessibility of individual provinces, and similarly CitationJin and Wang (2004) and CitationWang, Jin et al. (2009) analyzed the accessibility impact of the development of the mid- and long-term railway network. CitationLuo, Xu et al. (2004) studied the impact of high-speed railways on the accessibility landscape on the Shanghai–Nanjing corridor. CitationZhang and Lu (2006) adopted a more comprehensive view by taking into account both rail and road transport in the evaluation of regional accessibility in the Yangtze River Delta. However, while the huge plans are being carried out, a major concern of the transport sector has emerged. Since most of the transport projects are concentrated in central and eastern regions in China, people question whether new transport infrastructure will bring forth more equal regional accessibility or induce more uneven development (CitationHou & Li, 2011). Statistics have shown that large regional variations exist in the density and quality of road infrastructure in China, for instance. The western region is poorly served by roads compared to the central and coastal regions. In 2002, there were only 166 and 66 km of roads for every 103 km2 of land in southwest and northwest of China, respectively, compared to more than 460 km per 103 km2 of land in eastern and central regions. Among all provinces, Tibet and Qinghai are particularly poor in roads, with a density of only 33 km per 103 km2 of land. In addition, road quality is also the worst in the western region: high-grade roads like expressways, 1st and 2nd class roads account for less than 6% of the road network (CitationFan & Chan-Kang, 2008). Regarding the railways, especially for the passenger dedicated lines, most research findings have indicated that their construction will increase the imbalances between major cities and their hinterlands (CitationGutiérrez, González et al., 1996; Murayama, 1994). For example, after the introduction of Beijing–Shanghai high-speed rail, cities connected to this system immediately gained location advantages, while cities non-connected to this line were marginalized (CitationJiang, Xu et al., 2010).

Apart from the inequality problem in China’s transport infrastructure development, another main problem resolves around the motorization issue and the negative externalities that go with it in urban areas. While cities expand, most of them are experiencing changes in transport patterns, which includes in particular the growth of long-distance trips, the upward trend of motorized mobility and the dramatic increase in urban traffic demand (CitationGakenheimer, 1999; Kenworthy, 1995; Khisty, 1993; Zhao, 2010). The growth of private car ownership in China, which has provided greater opportunities for people to select their housing, places of work, business, entertainment and other activities, has led to the progressive dispersal of cities and to excessive motorized travel volumes, which generate substantial negative impact on the urban environment. Severe congestion problems in Chinese cities especially in large ones can be evidenced by very low average automobile speed and high percentages of driving time idly spent and accelerations and decelerations (CitationHook & Replogle, 1996; Kutzbach, 2009; Yan & Crookes, 2010). In the context of climate change, the increase in motorized mobility, including those of expressway and air transport, not only in China but also in other developing countries, causes serious environmental problems. According to the data available, the annual growth rate in CO2 emissions by the transport sector in developing countries is projected at 3.4% (CitationIEA, 2006; Zhao, 2010). In China’s motorization age, the transport sector’s use of petroleum increased from 24.6% in 2001 to 29.8% in 2005 of total use, and it is estimated to reach 47% in 2030 (CitationHan & Hayashi, 2008; Wang, Cai et al., 2007; Yan & Crookes, 2009; Yan & Crookes, 2010; Zhao, 2010). This situation is more apparent in large Chinese cities (CitationChan & Yao, 2008). Taking Beijing as an example, the number of private cars in Beijing had approached 4 million in 2009 and will still increase at an annual rate of 15% in the coming years. Within 2000–2005, trips by private cars increased by 6.6% while trips by public transport only increased by 3.3%. The transport sector in Beijing accounted for 15% of total urban energy consumption and air pollution due to road transport was 23% of total air pollution, close behind the pollution from industrial production (CitationHuang, 2009). In addition to the negative environmental impact, the auto-dependent travel also leads to higher numbers of traffic accidents. The statistics show that in 2007 the death toll as a consequence of road traffic was at 81,649 people, approximately ten times that in countries like Germany, Australia, Japan and France. And in the same year the “million vehicle mortality” of China was 5.1, 6 times higher than in developed countries (CitationJiang & Han, 2009).

3.6 An overview of the contributions in this issue

As the short tour d’horizon in the previous sections points out, many impressive developments have taken place in the previous three decades when it comes to transport infrastructure development, but many challenges still lie ahead in terms of regional and income distribution issues, persistent congestion, environmental and safety hazards and the professional policy-making and management approaches deployed to deal with these issues. In the remaining six contributions to this issue, recent research on transport infrastructure management in China will be provided and its outcomes described.

In the next and second article, Martin de Jong will take the reader into the subject of Confucian values and their modern day impact on decision-making on transport infrastructures in China. What are Confucian values, what are their advantages and disadvantages and to what extent can they be credited and/or blamed for specific features of infrastructure development in the world’s most populous nation? This analysis amounts to lessons for Western observers and policy-makers who occasionally tend to overrate the pros of their own system, but also to Chinese analysts and public officials for whom Confucianism might very well have a purifying influence.

In the third contribution, Nannan Yu, Martin de Jong, Servaas Storm and Jianing Mi dive a bit deeper into available statistics on infrastructure investments in China and make an attempt to demonstrate their impact on economic development at large. They find that the economic impact of transport infrastructure investments is positive but (across time and after reaching certain threshold values) decreasingly so, especially in the more developed East of China. They also come across issues of regional distribution within that large country and conclude that it was a good choice for the various governments to focus increasingly on investments in the interior of the country, but that the macro-economic benefits of focusing on the central parts may very well be more substantial than those pushing forward the West.

The fourth paper, written by Cheng Chen and Michael Hubbard, takes us to the topic of Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) as applied to road construction and management in China. It examines the power relations between the government, the private sector and citizens/users, which underlie the risk allocation process in PPPs for infrastructure. It argues that the institutional environment and resource dependency determine power relations, and hence risk allocation. The approach is applied to analyze risk allocation in a PPP toll road in Zhejiang province, China, where it is shown how the party with more power (in this case, the local government) was able to shift costs to the weaker parties, the users and the private sector.

Hangzhou is the geographical site for the empirical case study conducted in the fifth contribution. Although it is normally known as a tourist city and pearl by the West Lake, now it is the sad background for a subway construction accident with a great many casualties. Yongchi Ma, Martin de Jong, Joop Koppenjan, Bao Xi and Rui Mu give a chronological account of the events leading to the collapse of an oversized subway tunnel. After providing the empirical evidence, they then analyze the case in terms of indirect organizational and contractual root causes which made the occurrence of the more direct physical incidents far more likely. Although they do not use the term power exertion, it is obvious that here too, large powerful clients and main contractors tend to take their political and financial gain upstream, while delegating risks and problems to smaller subcontractors downstream.

The sixth article is also on the construction of a subway, but this time on the policy-making and duration of the preparation and approval process of the Harbin subway. Martijn Groenleer, Tingting Jiang, Martin de Jong and Hans de Bruijn take the tenets of policy network theory as known in the international literature as a point of departure and demonstrate that the success stories as to fast decision-making in China are not always corroborated by the facts, such as here where the decision making process eventually took several decades to complete and actual construction of the first line has begun only quite recently. They also show that in spite of the fact that the Chinese political and administrative systems evidence significant institutional differences with those in Western countries, proponents of a given project seeking recognition by authorities have to go through very similar hoops before definitive approval is granted.

Contribution seven plays out in yet another Chinese city of millions, Dalian this time. Rui Mu, Martin de Jong, Bin Yu and Zhongzhen Yang indicate how Dalian has long been known as one of China’s greenest cities, due in not a small share to its quite favorable modal split: many people use its high quality public transport. But growing motorization has had a negative impact on this situation and they consider a number of options to reverse the downward trend, the main one being integration among the terminals, routes and timetables of the several public transport providers. A mathematical model is thus built to test the effectiveness of reducing fragmentation in improving transit service. And the results show that the modal split after system integration is going to tilt more strongly towards transit, while as to service quality levels users cannot expect much improvement.

References

- C.K. Chan X. Yao Air pollution in mega cities in China Atmospheric Environment 42 1 2008 1 42

- F.F. Deng Y. Huang Uneven land reform and urban sprawl in China: The case of Beijing Progress in Planning 61 3 2004 211 236

- X. Deng J. Huang S. Rozelle E. Uchida Growth, population and industrialization, and urban land expansion of China Journal of Urban Economics 63 1 2008 96 115

- S. Fan C. Chan-Kang Regional road development, rural and urban poverty: Evidence from China Transport Policy 15 5 2008 305 314

- J. Friedmann China’s urban transition 2005 University of Minnesota Press London

- R. Gakenheimer Urban mobility in the developing world Transportation Research A 33 7 1999 671 689

- J. Gutiérrez R. Gonzalez G. Gomez The European high-speed train network: Predicted effects on accessibility patterns Journal of Transport Geography 4 4 1996 227 238

- J. Han Y. Hayashi Assessment of private car stock and its environment impacts in China from 2000 to 2020 Transportation Research D 13 7 2008 471 478

- S.S. Han Urban expansion in contemporary China: What can we learn from a small town? Land Use Policy 27 3 2010 780

- S.P.S. Ho G.C.S. Lin Converting land to nonagricultural use in China’s Coastal Provinces: Evidence from Jiangsu Modern China 30 81 2004 81 112

- W. Hook M. Replogle Motorization and non-moterized transport in Asia: Transport system evolution in China, Japan and Indonesia Land Use Policy 13 1 1996 69 84

- Q.S. Hou S.-M. Li Transport infrastructure development and changing spatial accessibility in the Greater Pearl River Delta, China, 1990–2020 Journal of Transport Geography 19 6 2011 1350 1360

- J. Huang Beijing will levy emissions fee for motorized vehicles 2009 Beijing Youth Daily Beijing

- IEA Road from Kyoto: Current CO2 and transport policies in the IEA 2006 International Energy Agency Paris

- H. Jiang J. Xu Y. Qi The influence of Beijing–Shanghai high-speed railways on land accessibility of regional center cities Acta Geographica Sinica 65 10 2010 1287 1298

- Y. Jiang S. Han Transit-oriented development: The concept and its practice in China 2009 China Communications Press Beijing

- F. Jin J. Wang Railway network expansion and spatial accessibility analysis in China: 1906–2000 Acta Geographica Sinica 59 2 2004 293 302

- J. Kenworthy Automobile dependence in Bangkok: An international comparison with implications for planning policies World Transport Policy and Practice 3 1 1995 31 41

- C.J. Khisty Transportation in developing countries: Obvious problems, possible solutions. Transportation Research Record 1993 Transportation Research Board Washington, DC

- M.J. Kutzbach Motorization in developing countries: Causes, consequences, and effectiveness of policy options Journal of Urban Economics 65 2 2009 154 166

- S.-M. Li Y.-M. Shum Impacts of the National Trunk Highway System on accessibility in China Journal of Transport Geography 9 1 2001 39 48

- X. Li A.G.-O. Yeh Analyzing spatial restructuring of land use patterns in a fast growing region using remote sensing and GIS Landscape and Urban Planning 69 4 2004 335 354

- E. Lichtenberg C. Ding Local officials as land developers: Urban spatial expansion in China Journal of Urban Economics 66 1 2009 57 64

- G.C.S Lin Metropolitan development in a transitional socialist economy: Spatial restructuring in the Pearl River Delta, China Urban Studies 38 3 2001 383 406

- G.C.S. Lin The growth and structural change of Chinese cities: A contexual and geographic analysis Cities 19 5 2002 299 316

- G.C.S Lin Chinese urbanism in question: State, society, and the reproduction of urban spaces Urban Geography 28 1 2007 7 29

- G.C.S. Lin S.P.S. Ho The state, land system, and land development processes in contemporary China Annals of the Association of American Geographers 95 2 2005 411 436

- J. Liu J. Zhan X. Deng Spatio-temporal patterns and driving forces of urban land expansion in China during the economic reform era Ambio 34 6 2005 450 455

- P. Luo Y. Xu N. Zhang Study on the impacts of regional accessibility of high speed rail: A case study of Nanjing to Shanghhai region Economic Geography 24 3 2004 407 411

- Y. Murayama The impact of railways on accessibility in the Japanese urban system Journal of Transport Geography 2 2 1994 87 100

- National Bureau of Statistics of China China statistical yearbook 2009 China Statistics Press Beijing

- OECD Economic survey of China 2010 OECD Paris

- X. Tan X. Li H. Xie C. Lu Urban land expansion and arable land loss in China – a case study of Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region Land Use Policy 22 3 2005 187 196

- C. Tuan L.F.Y. Ng B. Zhao China’s post-economic reform growth: The role of FDI and productivity progress Journal of Asian Economies 20 3 2009 280 293

- C. Wang W. Cai X. Lu J. Chen CO2 mitigation scenarios in China’s road transport sector Energy Conversation and Management 48 7 2007 2110 2118

- J. Wang F. Jin H. Mo F. Wang Spatiotemporal evolution of China’s railway network in the 20th century: An accessibility approach Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 43 8 2009 765 778

- Y. Wei M. Zhao Urban spill over vs. local urban sprawl: Entangling land-use regulations in the urban growth of China’s megacities Land Use Policy 26 4 2009 1031 1045

- Z. Wen J. Chen A cost–benefit analysis for the economic growth in China Ecological Economics 65 2 2008 356 366

- J. Whalley X. Xin China’s FDI and non-FDI economies and the sustainability of future high Chinese growth China Economic Review 21 1 2010 123 135

- F. Wu J. Xu A.G.-O. Yeb Urban development in post-reform China: State, market, and space 2007 Routledge London

- Q. Wu H. Li R. Wang J. Paulussen Y. He M. Wang Monitoring and predicting land use change in Beijing using remote sensing and GIS Landscape and Urban Planning 78 4 2006 322 333

- X. Yan R.J. Crookes Reduction potentials of energy demand and GHG emissions in China’s road transport sector Energy Policy 37 2 2009 658 668

- X. Yan R. Crookes Energy demand and emissions from road transportation vehicles in China Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 36 6 2010 651 676

- J. Yang R. Gakenheimer Assessing the transportation consequences of land use transformation in urban China Habitat International 31 3–4 2007 345 353

- X.J. Yu C.N. Ng Spatial and temporal dynamics of urban sprawl along two urban–rural transects: A case study of Guangzhou, China Landscape and Urban Planning 79 1 2007 96 109

- S. Yusuf T. Saich China urbanizes. Consequences, strategies, and policies 2008 The World Bank Washington DC

- L. Zhang Y. Lu Assessment on regional accessibility based on land transportation network: A case study of the Yangtze River Delta Acta Geographica Sinica 61 12 2006 1235 1246

- P. Zhao Sustainable urban expansion and transportation in a growing megacity: Consequences of urban sprawl for mobility on the urban fringe of Beijing Habitat International 34 2 2010 236 243

- Y. Zhou L.J.C. Ma Economic restructuring and suburbanization in China Urban Geography 21 3 2000 205 236