Abstract

This article explores the nature of ownership in a reform of the multi-donor-funded agricultural advisory service in Uganda. We argue that although there was a long process of programme formulation in which all stakeholders were heard, ownership was not as encompassing as it first appeared. In essence, the agricultural reform programme represented market-oriented values that were not echoed in large parts of the Ugandan polity. The eventual reversal of policy, back to government-provided extension, and to a large programme of heavily subsidised input supply, testifies to that. In addition, key stakeholders, notably local politicians and officials in the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry, and Fisheries (MAAIF), were shut out from the original programme and this threatened its viability. If a genuine analysis of the economic and political context had been carried out, the donors might have anticipated this. Instead, they were revealed as ill-equipped to counteract the politicisation and re-claiming of ownership by the Ugandan government.

1 Introduction

In 2001, heavily supported by donors,Footnote1 Uganda embarked on a radical reform of its agricultural advisory (extension) services. The National Agricultural Advisory Services (or NAADS) was drafted as a paradigm-changing policy-shift, a radical move away from a traditional, top-down government-led extension service to a privatised, demand-led one in which farmers were supposed to define their own requirements for advice, and it was launched by President Museveni as a part of the broader Plan for Modernisation of Agriculture (PMA) prior to the 2001 elections. However, although the reform was always conceived as an ambitious, long-term programme that might take 25 years to succeed, it has been suspended twice, drastically re-moulded, and finally turned on its head, to re-emerge as a government extension service once again.

Values, political interests, and elections all played a role in reversing NAADS. The purpose of this paper is to explore the nature of ownership and its various impacts on the evolution and implementation of policy reform, drawing on events around NAADS at a time when the technocratic argument in Uganda has been in retreat. We seek to understand why an avowedly home-grown programme stalled during the implementation phase.

The concept of ownership was agreed by donors and recipient countries in the Paris Declaration to imply that “partner countries take effective leadership over their development policies… through broad consultative processes” (CitationOECD, 2008: 3). We argue that ownership of NAADS was never as deep or as encompassing as it appeared on the surface, for at least four reasons. First, the role of the donors was more complex than just supporting a home-grown reform, indeed, among many stakeholders, the programme came to be perceived as donor-driven; second, a number of stakeholders, most notably officials from the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industries and Fisheries (MAAIF) and local politicians, felt marginalised in respect of NAADS implementation; third, the design of the NAADS programme followed a basically liberal approach to reform, but pro-interventionist forces within the Ugandan polity continued to prevail; fourth, the political processes in Uganda and the electoral cycles complicated the nature of ownership of NAADS. We argue that, despite their rhetoric, donors were not equipped to react flexibly to the complex and, at times, unpredictable domestic political processes that influence policy implementation. This is true in the case of the reversal of NAADS but is probably also the case more generally.

The paper starts by discussing the concepts of ownership and reform-implementation. It continues with an account of the origins and design processes of NAADS, going on to cover the reactions of the donors over three phases of programme implementation. Finally, the implications of our analysis are discussed.

2 Ownership, values and implementation processes

The apparent consensus among the international development community, and between recipient and donor countries, in favour of poverty reduction, partnership and country ownership of the Poverty Reduction Strategies was expressed for the first time in the Millennium Development Goals (CitationMaxwell, 2003). In 2005, this consensus was elaborated and written down in the Paris Declaration (CitationOECD, 2008). The concept of ownership was a key feature in this new consensus (CitationFaust, 2010; Lazarus, 2008; Maxwell, 2003). The underlying idea was that a country’s poverty reduction strategy would be the outcome of a participatory process which would include all the various stakeholders in the recipient country and that, as a result of this process, it would reflect the predominant priorities in the country. Ownership was deemed to be critical to successful sector- and cross-sectoral programmes such as Uganda’s PMA.

But what does ownership actually mean? There is no agreement in the literature but it is becoming clear that the assumptions behind the Paris Declaration, especially the supposition that the concept was straightforward, are overly optimistic, even naive. Ideally, ownership would seem to mean that governments should agree on, decide on and implement the policies they prefer, on the basis of domestic political and administrative processes. However, because the ideal case, complete agreement, was not viewed as feasible, the donors argued that “a critical mass of support for national policy” (CitationLazarus, 2008: 1206) should be pursued and would be sufficient. In other words, there was a recognition that ownership could not mean that all state and society actors supported a policy, but at least it would necessitate that a certain consensus among actors with a stake in the policy had been established. Others took a more sceptical position. CitationBrautigam (2000: 31–33) argues that, in practice, the term is currently used more to denote “the extent to which there is a coincidence of interest and ideas between aid agencies and the political leadership, regarding the design and implementation of certain programmes and policies favoured by the aid agencies”. If the term ‘ownership’ then comes to represent the degree of agreement between donors and the recipient government, rather than the extent to which the programme is really home-grown, the prospects for sustainable implementation of the programme must surely be less certain.

In this section, we briefly address two key elements of ownership: (i) ownership through process or content; (ii) ownership throughout the implementation phase.

| (i) | Ownership through process or content: the role of values and ideas | ||||

In the aid industry, the discourse on ownership is often kept at a general level, the term usually being applied to the national processes around reaching agreement on a poverty reduction strategy.

This suggests the focus is on process rather than on content and the assumption has been that an inclusive process will result in ownership. However, a number of observers have suggested that there might be some essential values in regards to ‘development’, among African politicians and bureaucrats that are at odds with the dominant values among aid agencies. With the term ‘values’, we refer to the normative dimension of public policy (cf. Swinbank and Daugbjerg, introductory article to this issue) where it has become clear that African officials and policy-makers are often less pro-market than the donors. CitationMkandawire and Olukoshi (1995), for example, were among the first African observers to argue that the structural adjustment programmes rested on a wrong diagnosis of Africa’s problems, and that to blame failure on a lack of ownership might be missing the point if it were genuinely believed that the adjustment measures were not the right ones. CitationMkandawire and Soludo (1999: 76) criticised the 1990s public sector downsizing programmes for often reflecting more of “an ideological bias against big government than any mere rationalisation of an inefficient and bloated bureaucracy” (CitationMkandawire and Soludo, 1999: 77).

This value conflict seems to be quite deeply ingrained. Among African politicians it is rare to find misgivings as to the virtues of government intervention. President Museveni’s argument to an OAU summit in 1990 is typical: “deliberate government intervention is needed to ensure overall sectoral and enterprise planning. It is an error if we simply leave the emergence of new industries to so-called market forces. There is a need for proper planning” (CitationMuseveni, 1992: 238). Although Museveni later embraced the liberalisation programmes, his ideological roots, and those of many others in the African elites, are to be found elsewhere than in the liberal camp. In an analysis of agricultural liberalisation in Tanzania, Brian CitationCooksey (2003: 67) argues that the dominant narrative on liberalisation there “fails to recognise the powerful anti-liberalisation forces within Tanzanian society”. He shows how the liberalisation of Tanzanian export agriculture failed to take place to the extent claimed by the Tanzanian government and donor agencies. Similarly, CitationTherkildsen (2011) describes how the Tanzanian government abandoned a donor commended policy initiative on agricultural marketing and input supply to replace it with a more pro-interventionist policy. CitationJoughin and Kjær (2010) observe how in the Ugandan Ministry of Agriculture there is still, despite years of donor-funded programmes aimed at reducing government intervention, a widespread perception that agricultural development is something that can be “done” from the top down. The point is that, although ownership of a programme is often claimed, actual ownership may only be partial and, if the term comes to mean only the extent to which donor-driven programmes are adopted, then a subsequent lack of commitment may only mean that all was not what it seemed and, indeed, that there might just be a basic disagreement around the programme (CitationBotchwey et al., 1998: 24). In other words, even when there has been a process of listening to various stakeholders, there may simply be a value-based disagreement with the content of the programme, a disagreement that may be hard to express in formal hearing processes.

| (ii) | Ownership throughout the implementation phase | ||||

‘Ownership’ must surely imply not only a rhetorical commitment from the political elite but also a commitment to, and a record of, effective programme implementation. Significantly, it would also seem to imply that, over and above the sustained commitment of the political elite, there must also be a certain loyalty and back-up from the implementing bureaucracy. This process of implementation is rarely straight forward. CitationFaust (2010) argues that the new poverty agenda, with its assumptions about donor-recipient relations, “assumes excessively over-simplified processes of policy-coordination and reform”. The agenda, in his view “ignores the political, iterative, and experimental character of governance” in recipient countries that are at the same time going through a political liberalisation process, and he argues that such domestic political processes leave “little room for encompassing ownership with regard to far-reaching policy-reforms”. Indeed, in a complex political process, policy-implementation may be hampered by political interference even after the policy decision has been taken in government (CitationThomas & Grindle, 1990). In fact, rather than being merely a technical affair that can be left to neutral implementers, sustained implementation often requires a series of political decisions rather than just one initial policy choice.

Elections constitute an increasingly important element in the political process, one that influences reform in many unpredictable ways. Elections have an effect because political leaders who seek to remain in power will want to implement policies that are both immediately visible and attractive to large groups of citizens in the short term (CitationKjær & Therkildsen, 2012). Hence elections may drive policy shifts in directions that were not initially considered or intended. CitationFaust (2010: 517) points to the fact that democratisation in neo-patrimonial countries gives rise to an institutional insecurity that promotes incentives for policy-makers to revert to populist means, thereby rendering policy-making more volatile. In addition, the way implementation arrangements are set up effects the process of implementation because it can create reluctance among some members of the bureaucracy to cooperate in programme-implementation. Traditional ministries may be bypassed if governments and donors agree to set up parallel agencies (CitationBirdsall, 2004) and, because of this, policies may be altered or indeed reversed during implementation. Whether donors know how to navigate amid such complex processes is questionable. As CitationFaust (2010: 517) argues, “donor strategies that build ambitious co-ordination plans upon simplistic notions of encompassing ownership are often ill-prepared, when confronted with the reality of policy processes”. In fact, if a programme turns out to be politically costly, real ownership may prove to be more fragile than expected and sustained implementation may not materialise. As CitationBooth (2011) puts it, it is real policy that counts, not nominal policy.

“Real” policy is rarely identical to what would be “ideal” policy in the eyes of technocrats and/or donors. However, there will often be a higher degree of ownership to real policy and, therefore, it should be more sustainable in terms of implementation. As argued by CitationWhitfield (2009: 5), ownership of a policy does not necessarily imply that a policy is “the best” policy in a given situation. Neither does it imply that the decision has come about through a democratic decision-making process. In fact, the decision may even have resulted from patronage, weak policy-analysis and/or corruption. The defining feature of ownership is, however, in Whitfield’s view (CitationWhitfield, 2009: 4), that recipient governments are able to secure control over implemented policy-outcomes.

The Ugandan NAADS programme is a good case through which to explore the issues of ownership and implementation, because it demonstrates a pattern that is often seen in recipient countries in Africa. Uganda has a generally acceptable reform record: there have been high economic growth rates and there is macro-economic stability and a capable Ministry of Finance. As in several other African countries, however, there are also governance problems and cases of stalled reform, particularly with regard to public sector reform and decentralisation (CitationTripp, 2010). In Uganda, it has become increasingly expensive for President Museveni to stay in power, a phenomenon, Joel CitationBarkan (2011) has termed “inflationary patronage”, and this has affected public budgeting significantly. In order to win elections, large amounts of patronage were distributed preceding the 2011 elections. Donors are concerned about these authoritarian tendencies but, although there have been some cuts in general budget support (GBS); because the economic indicators are acceptable and poverty is still being reduced, they have nonetheless continued with their broad GBS- and sector-budget support approach. This fits with the general picture of donor responses to African political developments. By looking at the project level, in this case at the Ugandan NAADS reform, we can therefore explore what CitationYin (1989) might call a typical case, one from which we can learn more about the causal dynamics and processes that take place.

In what follows, we now examine the nature of ownership around the NAADS project. Then, we proceed through the three phases of its implementation and explore how “real policy” changed during implementation, and how the donors navigated amid the complex implementation processes. We go on to discuss possible explanations and implications. In these examinations, we draw upon a close reading of NAADS evaluations and reports, as well as on the debate on NAADS as it appeared in the Ugandan newspapers. We also make use of interviews with some of the implementing officers, politicians, and donor staff involved in drafting the plans. Finally, we draw on one author’s personal experience as Advisor in MAAIF.

3 The NAADS programme

3.1 Initial drafting and “ownership”

From its inception, the NAADS project focused on fundamentally reforming agricultural extension services, turning the traditional Ugandan service from a top-down Training and Visit system to a privatised and demand-led advice system. The project was clearly highly ambitious. The use of the private sector to provide services (rather than government officers) was always a radical move although the technocrats in the Task Force that formulated the project appeared to believe it would work.

The origins of NAADS can be traced back to the economic liberalisation of the late 1980s and the related reorientation of the public sector, although the most important driver for what would become the NAADS approach was the negative experience of NAADS’ predecessor, the World Bank-funded Agricultural Extension Project (AEP). The Implementation Completion Report of AEP was highly critical of the top-down approach that characterised the programme and indicated that the project seemed to ignore almost entirely the importance of empowering farmers and creating a sense of ownership among beneficiaries. From this analysis emerged the idea of developing a new project based around the delivery of extension (and research) services through a mix of private and public arrangements and not through a public body. This was an idea which fitted well within the emerging paradigm of the time, the policy framework that was the Poverty Eradication Action Plan (PEAP) and its sectoral counterpart, the Plan for Modernisation of Agriculture (PMA) (CitationGoU, 2000).Footnote2

In the late 1990s, a core group of technocrats in the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (MoFPED) established a Task Force and began the design of the new project which was to be decentralised, with services mainly contracted out and sustainability sought through cost-recovery and cost-sharing. As described by CitationNahdy (2002), later Executive Director of NAADS: “the criteria used for the selection of the task force members reflected the width and depth of stakeholder interest and covered all key representation from these interest groups.” Ownership would be achieved because “NAADS has had very wide acceptance at home at all levels. The team consulted very widely, both internally and externally during every design stage, which greatly helped in reaching a common goal and consensus …. Those consulted included policy makers, decentralised governments, NGOs, farmers, service providers, private sector, the developmental partners and several other relevant institutions…. The programme also had the right timeframe (18 months) to complete the task and sufficient budget support, which allowed for intensive and extensive consultation and consensus building.”

However, in spite of the fact that so many stakeholders had been consulted, the question remains as to whether there was true, encompassing ownership of NAADS or whether Nahdy’s account of events simply reflects a desire for NAADS to be broadly owned. This was before the time of sector political economy analysis so no such analysis was carried out.

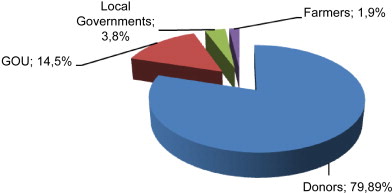

The influence of donors is unavoidable. At appraisal, the projected cost of the first phase of the NAADS programme was US$ 107.9 million. At the end of the 2006/07 financial year, seven different donors (see above) had contributed the bulk (nearly 80 per cent) of the resources, with the GoU and farmers contributing the remaining 20 per cent (see Fig. 1 ). Local governments and farmers contributed some 4 and 2 per cent, respectively.

Source: Benin (2009).

This was therefore widely perceived as a donor-driven projectFootnote3 and it was embedded in a context where the entire PEAP framework was viewed by many as too donor-driven.Footnote4 When asked about ownership of NAADS, a Ugandan MAAIF official argued that the programme was not only supported, but also “initiated and spearheaded by the donors” (personal communication, March 2011).

Some bureaucrats and extension officers seemed to be of the opinion that privatising agricultural advice would do no good, believing instead in strengthening existing structures. However, at the time, in the prevailing mood, they kept their own counsel. This might have been because they were excluded from the Task Force and because none of them had been recruited to staff the implementing agency, the NAADS Secretariat. MAAIF was to a large extent by-passed by the way the implementation of NAADS and PMA was designed. Both programmes had secretariats in Kampala, located about 40 km from the mother ministry, and the NAADS Secretariat interacted directly with NAADS officers at the local government level without going through MAAIF. Staff of the NAADS Secretariat were largely recruited from the National Agricultural Research Organisation (NARO), another semi-autonomous agency under MAAIF. The Directorate of Agricultural Extension in MAAIF was abolished, and none of its employees were recruited for NAADS (Interview, Official at MAAIF, March, 2011). According to one official from MAAIF, “the resistance from MAAIF technocrats was underestimated by the proponents of reform. The MAAIF officials had great influence over the local levels, the majority of whom did not subscribe to NAADS. In addition, the NAADS group approach also excluded some farmers who were important elites. Those excluded elites protested alongside with the local politicians” (Interview, Official at MAAIF, March, 2011). At the same time, local government structures were also circumvented by NAADS as the local level NAADS officers did not report to the MAAIF Production Officer in the districts and, as one interviewee noted: “the NAADS coordinator became bigger and more important than the Production Officer”. Yet the latter was senior in rank.

There was no role for local politicians in NAADS and this also proved problematic for implementation. In interviews, several local politicians at the sub-county level expressed their dissatisfaction with the way the original NAADS was drafted and their exclusion from the programme. A local politician (and chairman of the local council), for example, argued that “at first NAADS was not so good… we were not involved, and we went to NAADS meetings without being invited and with no allowance. We had to force ourselves upon them. Now with the new NAADS we have been included in the planning”.Footnote5

If the donors foresaw that the loss of power of government officers, and specifically those of MAAIF, would be a sore point for the life of the project, they did nothing to allay the problem. They did not see that, from the outset, the ownership of NAADS was not as encompassing, or deep, as it then appeared.

3.2 Phase I: 2001–2008: initial success and growing concerns

3.2.1 Early evaluations

The first phase of implementation saw a significant roll-out of the NAADS programme to 79 districts (CitationBenin et al., 2007). Later, in the NAADS Impact Evaluation (CitationBenin, 2009), IFPRI researchers found “clear positive impacts on the adoption of improved technologies, productivity and per capita incomes.” Their study used data from two rounds of household and farmer group surveys conducted in 2004 and 2007 and a variety of evaluation methods. They also found that, between 2004 and 2007, NAADS was associated with “an average of 42–53 per cent greater increase in the per capita agricultural income of the programme’s direct participants compared to their non-participant counterparts”.Footnote6 It is clear from these studies that NAADS had some early gains and it was a common opinion at the time, that it was the successes in the first few districts, that led to more political attention and political pressure to roll-out the programme faster. A rapid roll-out, it was perhaps judged, could help win votes. However, a rapid roll-out also put pressure on the implementing agencies and, it seems, might have overstretched their capacity.Footnote7

In any case, this first phase also showed the first signs of changes in the programme. Interestingly, buried away in the long text of the Performance Evaluation, are two other observations:

| • | “There has been a noticeable attempt by politicians to influence farmers to adopt enterprises identified in the zonal planning process, in some cases, contrary to farmers’ wishes, which has been unhelpful.” | ||||

| • | “The recent growing unease expressed by GoU as regards involving the private sector (rather than Local Government extension staff) is creating a sense of some uncertainty on the programme’s future direction.” (CitationGoU, 2007: 6) | ||||

These two observations indicate that local politicians were desirous to influence the NAADS process and they support CitationThomas and Grindles’ (1990) argument that if important stakeholders are not able to influence a policy decision, they are likely to try to influence implementation. In the case of NAADS, the argument is reinforced by the fact that, as the 2006 elections were approaching, the first presidential intervention in the NAADS programme appeared. The Integrated Farmer Support Component (IFSC) which, at its core, provided farmer forums with publicly funded inputs such as seeds, was added to the programme. This publicly subsidised input support contradicted the market-led philosophy behind the original NAADS but was considered to be a popular and therefore, vote-winning initiative.

3.2.2 Donor reactions

The Evaluations are curiously mute as to the donors’ view of events in the NAADS narrative and the Aide Memoires of the various supervision missions are faultlessly diplomatic on the issues that would later loom large.Footnote8 However, it is possible to deduce from, for example, the Aide Memoire of the June 2008 multi-donor Joint Identification Mission that all was not well and that the donors felt unease that the impact of NAADS was not more obvious. The real growth in agricultural output was apparently declining, from 7.9 per cent in 2000/01 to 0.7 per cent in 2007/08 (CitationUBOS, 2007, 2008), while the country’s average calorie intake per person per day had only improved from 1,494 in 1992 to 1,971 in 2005, still below the World Health Organisation recommended figure of 2,300. The number of people who were food insecure had actually increased from 12 million in 1992 to 17.7 million in 2007.Footnote9 The donors also report disquiet that the ‘overall vision of NAADS, which has proven to achieve results for farmers’ was being compromised. In particular, from their perspective, they were frustrated at the government’s reneging on the private sector basis of the NAADS strategy and its insistence on adjusting ‘modalities of service delivery to utilise public sector extension staff within NAADS … and support the use of demonstration, model and nucleus farmers.’

In summary, there was a general sense of foreboding, shared by all the donors, around what seemed to be growing interventionism in the agricultural sector. Hindsight shows that these anxieties were justified but, at the time, especially given that NAADS was always conceived as a 25-year programme and that the two evaluations had been so positive, the donors saw no reason, in the round, and certainly in public, to be other than generally satisfied. So, in late 2007, with its good record to date and the end of Phase 1 approaching (December 2008), it was time to prepare for a second phase of NAADS.

3.3 Towards Phase II

3.3.1 The first suspension

The second phase of NAADS was intended to integrate and strengthen the combined efforts of the research agency, NARO, and NAADS. Accordingly, the first phase of NAADS was extended by a year to give time to prepare the documentation for a new and bigger project, to be called the Agricultural Technology and Advisory Services (ATAS) project, proposed start date 1st July 2009.

Then, in late 2007, without warning, a directive from President Museveni suddenly suspended the NAADS programme. All activities, and even salaries, were put on hold. The reasons for the suspension were never made entirely clear but the President’s dissatisfaction was widely reported in the press. It seemed he had not been shown the Evaluation Reports. This is perhaps an illustration of how, as CitationBooth’s SPA study (2003) puts it, it is so difficult to “transform technocratic ‘ownership’ into political ‘ownership’ at the highest level”.

There then followed seven months of ‘negotiations’ with the donors, during which State House’s refusal to bide by the various agreements became ever more apparent. The Government’s position was based on a new vision for the country – Prosperity for All (PFA) – a strategy first outlined in the National Resistance Movement (NRM) manifesto of 2006. This promised that everyone in the country would prosper and that government would use substantial public expenditures on rural programmes to that end. In the rural areas, lower level governments were tasked with selecting, through committees of which the local NRM chairman must be a member, six model farmers per parish to receive benefits and serve as demonstration farms for the rest of the community (CitationNRM, 2006: 81).

When it first appeared, the donors had assumed PFA was largely political rhetoric. However, as the suspension dragged on, and even though Government spokesmen and NAADS staff still talked the language of the original NAADS, it was apparent that PFA was becoming the main driver of agricultural policy. The PFA Unit in State House was organizing Presidential Tours around the country where President Museveni would visit model farmers and give them tangible benefits such as pick-up trucks or cash (Monitor, September 10, 2008). This was directly contrary to the basic message of NAADS (that farmers need to find productive activities that are profitable) but Government seemed not to be concerned. There was real unhappiness among the many existing NAADS groupsFootnote10 and the donors were muttering private threats as to the possibility of a suspension of funding but Government persevered with its plans regardless.

Eventually, in May 2008, after at least two private, Ambassador-level meetings with the President, NAADS was reinstated but at the cost (to the donors at least) of a new Memorandum of Understanding that conceded that the ‘emerging cadre of private sector service providers’ would be side-lined in favour of taking on the former district extension officers as NAADS employees. This clearly invalidated the whole private sector, service provider-basis of NAADS and, from now on, the programme would be referred to by its adherents, as the “new NAADS”.

PFA was now ascendant. While some commentators saw the transformation of NAADS as a “political gimmick to win votes in the 2011 elections” (New Vision, July 30, 2008), Moses Byaruhanga, Presidential Adviser on Political Affairs, wrote (Monitor, November 10, 2008) that ‘on top of what government is doing with NAADS such as selecting six homesteads from each parish and giving them inputs, government should subsidise tractors for farmers.’ The ambitions here go far beyond the original market-oriented philosophy of NAADS: even if the body of old NAADS was still moving, it was surely dead. In its place was a process that favoured political interventions and especially those of the local NRM chairmen who are important in terms of their support and ability to mobilise voters. The change-over also privileges a basic value system which favours government intervention (especially subsidizing inputs and tractors).

3.3.2 Donor reactions

The reaction of the donors was one of private alarm but public inaction. Probably this latter was a function of the inability of the different agencies to reach agreement on what to do. DFID, BSF and the Irish had already announced their withdrawal from the second phase leaving the other, smaller, grant-providing donors, like Danida and the EU, to try to reach a common position with the bigger, loan-providing agencies, especially the World Bank.

At any rate, once NAADS was ‘reinstated’, formulation of the new programme, ATAS, began again, albeit now some months behind schedule and within an atmosphere of growing distrust. On the surface, at least, the process continued as if nothing had happened even though the donors were quite clear that “the suspension has had an adverse impact on programme activities and disbursements … it is critical that the overall vision of NAADS, which has proven to achieve results for farmers, remains central to its implementation.” (Identification Mission for ATAS, June 2008).

For nearly a year, formulation continued through more large, multi-donor Stock-taking, Identification and Pre-appraisal missions,Footnote11 in an increasingly intemperate mood. Then, in February 2009, a public meeting was convened, chaired by State House, with ten Ministers, including the Minister of Agriculture, in attendance, and five hundred representatives of the district leadership. The press and the donors were barred from the meeting and the message was unequivocal: the President’s recent directives were to be followed by district officials, to the letter and with immediate effect and without the legally required consultation with the donors. Essentially, as one internal observer wrote: “the programme would be refocused to align it with Prosperity for All … the bulk of NAADS resources (about 80 per cent) would be utilised to turn their (model) farms into farmer training/demonstration centres.”Footnote12 The directive was given by the Minister for the Presidency that all districts should go back and make sure they adjusted the number of model farmers in each district to six per parish. The previous method of farmer selection in the NAADS guidelines should not be followed.

Forced to react, on March 1st 2009, the World Bank Country Director for East Africa wrote on behalf of the NAADS donors, to the Minister of MAAIF to say “in view of the Government’s deviation from agreed implementation modalities, we wish to inform you that the donors are considering suspension of disbursement in accordance with the terms and conditions of their respective financing agreements.”Footnote13 But the government had had plenty of time to anticipate this and moved smoothly to head off the crisis by quickly announcing that the existing ‘old NAADS model’ could continue after all. Donor funds could be used for the ‘old NAADS’ while, in parallel, GoU would find an additional USh34 billion (USD17 million) of ‘own money’ to ‘support model farmers to commercialise’ – i.e. the 6-farmer model ‘new NAADS’.

The donors, apparently reassured that NAADS was still a viable operation, resumed Phase II formulation once more, ignoring the growing evidence of governance disarray. They also had to ignore the evidence in front of their own eyes: in October 2009, a joint formulation mission held discussions with various district leaderships and, in Mbale, found “frustration and disappointment at the imposition of the 6 farmers model and the severe negative impact on farmer groups this has had. With no funds being allocated to the ‘normal NAADS’ operations, these groups have stopped functioning and are severely discouraged.” There were many reported cases in which NAADS was used to ensure political support from important movement cadres within the party and the army.

Deadlines for completion of the documentation came and went several times, the frustrated donors, even threatening again, in December 2009, that ‘this deadline cannot be postponed, and a failure to meet it would most probably mean losing the funds.’ But the deadline was postponed once more such that, by February 26th 2010, the process had degenerated to the point where the donors response to the Minister of Finance’s annual Budget Speech included an uncharacteristically undiplomatic reference by the World Bank Country Director to ‘billions of shillings lost in the NAADS scam’.

Yet, only two months later, in April 2010, a final formulation mission for the (now re-named) Agricultural Technology and Agribusiness Advisory Services Programme (ATAAS) was able to write ‘The IDA Financing Agreement and all conditions precedent to its effectiveness or to the right of the Recipient to make withdrawals under the IDA Financing Agreement … have been fulfilled’. From here it was an easy stroll to the finalisation of the ATAAS Project Appraisal Document in May 2010 (CitationWorld Bank, 2010). The programme was to be huge: the total project cost is US$ 665.5 million to be disbursed over the five-year period from July 2010 to June 2015, with commitments from donors of US$ 161 million. The GoU would finance the major share of project costs, allocating about US$ 497 million over the five-year project period. The ratio of government’s contribution to DP contribution had been turned on its head since Phase 1, with government now committed to pay 75 per cent of the total cost (compared to 15 per cent in Phase 1), arguably a reflection of State House’s more pressing sense of ownership of a different kind of project.

3.3.3 The second suspension

By June 2010 then, it seemed, from the financiers’ perspective, that the hard part was done and, despite the unease of at least some of them as to the various compromises made, the new ATAAS was finally set to get underway, its design much closer to the minimum acceptable level of technical blueprint than expected. The last formal hurdle was the Implementation Guidelines still being prepared by NAADS staff. Then, suddenly, on July 8th 2010, President Museveni announced NAADS was suspended again, for a second time. ‘NAADS has failed to benefit the grassroots’ he was reported to have said, before urging farmers ‘to take elections seriously, … electing bad leaders can take the country back into chaos’. (Monitor, 9/7/2010).

The impotence of the donors to influence ‘real’ policy was apparent. Much policy dialogue had been endured but it was now clear that this had had no impact on real policy at all. They were now forced to stand by and wait, once more, for elucidation. This would take five more months but eventually NAADS was duly re-instated again (New Vision, 7/12/10), more or less by another Presidential Decree. The long awaited Guidelines were then finally published, 27 months late. If the donors had hoped the Guidelines would ease the way to a smooth implementation process they were to be disappointed.

While thorough and clear, the Guidelines document is completely at odds with the ATAAS Project Appraisal Document. It is almost as if written without reference to, or even knowledge of the appraisal, which is possible but curious, considering the two processes were going on at the same time. For example, it provided for government supplied planting material and allowed a large role for local politicians and party chairmen in deciding who should benefit from government support. In all, it reflected much more interventionist, top-down values than did the ATAAS Project Appraisal Document and inevitably, the donors were very unhappy. They were also exasperated at their complete exclusion from the preparation process and by the end of 2011 there was something like stasis. The donors said privately that they would not accept the Guidelines while GoU’s position was that it would not accept the appraisal document as it was, despite playing a full part in its preparation only months before.

Since then, the President (New Vision, January 16, 2011) ratcheted up the pressure another notch. Speaking at a rally, he said no decision should be taken by NAADS unless every adult in the village agrees on it. He was insistent that “the new rules of NAADS are that all adults must be called for a meeting where what is to be done is discussed and agreed on. He added that he would not hesitate to sack any of the NAADS coordinators found guilty of irregular dealings.” The president’s accusations of incompetence and corruption against local NAADS coordinators are seen as a way of avoiding being blamed for the lack of results of NAADS immediately before election times.Footnote14

In December 2011, advertisements for the positions of the NAADS senior management had been posted in the Uganda press and the Executive Director and his dedicated team had, despite their “… very wide acceptance at home at all levels…” and their consulting “…very widely, both internally and externally during every design stage, which greatly helped in reaching a common goal and consensus …” (see above) lost their jobs.

The NAADS Secretariat had been technically compromised, starved of funds and undoubtedly seriously damaged. Meanwhile, the ‘new NAADS’ was diverging ever further from the original concept. The Performance Evaluation (CitationITAD, 2008) had already flagged the ‘credit’-providing Integrated Support to Farmer Groups Component of the project as problematic. It was a surprise therefore that, in 2009, one World Bank staffer should estimate to one author that 80 per cent of all the NAADS budget was now accounted for by the Integrated Support to Farmers’ Groups component and that it was essentially being distributed as handouts, with all the dependency issues that entailedFootnote15: basically a political pay-off in terms of support for the ruling elite.

Throughout this long narrative, donors were continually frustrated by GoU’s refusal to make any meaningful compromises. There were, of course, plenty of emollient policy-related words from GoU but to repeat CitationBooth (2011), it is ‘real policy that counts, not nominal policy. Policy is what policy does’. Publically the donors remained more or less diplomatic and made no official comment (although all the smaller ones, i.e. all but the World Bank, IFAD and also the African Development Bank, had withdrawn or declined to support ATAAS until they received further reassurances). While no money had yet been released for the new ATAAS, the donors, and particularly the World Bank, stood accused of standing by as a very carefully planned public extension programme was compromised then dismantled before their eyes. The reality was that the donors colluded in this situation, ignoring the disturbing evidence from their own Joint Review Reports, over two to three years. Explicit in all of these reports was a ‘must-keep-the-show-on-the-road’ view of the process that arguably had to supersede technical reservations as to the sustainability of the long-term results.

4 Discussion and implications

As of spring 2012, the situation with NAADS was a mess. A well-intended project with significant potential for improving agricultural productivity and reducing rural poverty had been subverted and undermined. Policy makers, decentralised governments, NGOs, farmers, service providers, the private sector, the development partners, and several other relevant institutions had all been consulted and the programme was regarded as “widely accepted at home”, to use the words of the NAADS Director. Why was it then gradually dismantled?

We have argued that ownership may not have been as encompassing as it first appeared. The NAADS programme represented market-oriented values that were apparently not echoed in large parts of the Ugandan polity. The reversal of policy, back to government-provided extension, and to a large programme of heavily subsidised input supply (with the benefit reaped disproportionality by the better-off users of inputs), testifies to that. In addition, ownership was concentrated with the NAADS Secretariat, the Ministry of Finance, and initially also with the President. Key stakeholders, notably local politicians and MAAIF, were shut out from the original programme and this threatened its viability.

Also, unquestionably, the political processes of implementation significantly affected the character of ownership. As the costs of staying in power increased, public policies were also increasingly affected by political concerns (CitationBarkan, 2011; Mwenda & Tangri, 2005). NAADS became gradually politicised and this affected implementation especially as the February 2011 elections drew closer. Donors were not able to navigate in this process of politicisation. Our narrative thus confirms CitationFaust’s (2010) observation that donors tend to ignore the “political, iterative, and experimental character of governance” in countries that are liberalizing politically. One could argue that, in the case of NAADS, ownership of the programme has been reclaimed in the process, as it has moved away from what the donors and some technocrats see as desirable, towards a programme, the new ATAAS, that is more in line with what an influential section of Ugandan stakeholders wish for. It is now, of course, much more politically feasible, even if it may not improve living conditions for the originally intended beneficiaries, the poor farmers. Improved ownership is mirrored in the fact that the major part of the funding for the new programme comes from the Ugandan government. If ownership means, as CitationWhitfield (2009) argues, the extent to which recipient governments are able to secure control over the implementation of policy outcomes, then certainly there is more ownership now than when the first NAADS programme was decided. This is true, ironically (and significantly), even though there was an Act of Parliament approving the original NAADS programme.

The donors have little capacity to deal with this other than a collective, behind closed doors, shaking of heads. They can, on occasion, delay funding or threaten suspension, and some donors may, with time, move funds into less contentious areas, but they certainly lack the capacity to try to rescue a project like NAADS. Challenges like those posed by the hijacking of NAADS were why DFID-UK originally embarked on the Drivers of Change analyses, and, among others, Swedish SIDA on its power analyses and OECD DAC on its governance assessments. Also, an increasing number of sector political-economy analyses have been carried out (CitationDuncan & Williams, 2012). If a genuine analysis of the economic and political context had been undertaken, donors might have concluded that these politicians, local government staff and MAAIF officers, smarting from their exclusion from NAADS formulation, would likely try to influence its implementation. However, although recognized as important among donors, the insights gained from such political economic analyses are still very difficult to put into practice (CitationHout, 2012). If gaining more knowledge on the political economy processes tends to suggest donors should abandon problematic programmes, they might feel they would be better without the knowledge. In a Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP) monitoring study from Latin America, CitationDijkstra (2005) tracks the various contortions the donors undertook to maintain the fiction that PRSP processes had been undertaken “according to the rules”, so that it would not be necessary to suspend programmes. This involved turning a blind eye to some questionable aspects of country politics.

There are many reasons why abandoning a programme is difficult. One may be impatience to effect disbursement, as noted by CitationBirdsall (2004). She argues that such impatience can “preclude attention to the fundamental institutional problems, such as political patronage…” (CitationBirdsall, 2004: 5). She also notes that this impatience is often combined with an unwillingness to exit from programmes where the aid is not helping. More importantly, the sheer number of donors and their different interests make coordination difficult. Generally, the multi-lateral World Bank would tend to accept more deviations from a policy than the bilateral donors and hence be more reluctant than others to deal with the politics in their partner countries (CitationHout, 2012: 407). Donors therefore might not agree on how to act upon the insights gained from political economy analysis. This would certainly be the case in our NAADS narrative, even if PEA analysis had been carried out. CitationBerg (2000) and CitationDuncan and Williams (2012) also explain the tendency to “overestimate local commitment and capacity” with a continuous pressure to spend. Especially for favoured countries, like Uganda, donors may feel they have little option but to stay the course and try to make the best of the situation, even when the implementation of their own best-laid plans is veering off course. If donors really want to be serious in emphasizing ownership, however, they would be best advised to either accept policy-decisions even when they do not agree with them, and even when they result from patronage; or to carry out a context sensitive political economy analysis and develop tools to act upon the insights from such analyses.

Notes

1 When we refer to donors we mean, unless otherwise indicated, the multi- and bilateral organisations funding the original NAADS programme. They were the World Bank, the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), the European Union, the Department for International Development (DFID-UK), Danish International Development Assistance (Danida) the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the Belgian Survival Fund (BSF), the Netherlands and Irish Aid (CitationITAD, 2008).

2 The PMA was a major initiative introduced during the 2001 election, publicly backed by the President and based on seven main public expenditure intervention areas.

3 Which was the case with all the projects in the sector: less than 20 per cent of the entire MAAIF budget is capital spending (CitationGoU/EPRC, 2009) and of that, all of it is under a handful of donor-funded projects.

4 CitationOxford Policy Management (2008); Oxford Policy Management (2005); Personal interview with Ogenga-Latigo, head of opposition in parliament, 2009.

5 Local Council 3 Chairman from Bubaare sub-county, Mbarara, interviewed in May, 2009.

6 See also CitationGoU (2007) and CitationGoU/EPRC (2009) for positive assessments of the first NAADS period.

7 Personal interview, researcher on agricultural programmes in Uganda, March, 2011.

8 Unless otherwise indicated, this section draws heavily on the Aide Memoires from CitationJoint Identification Mission (2008), CitationJoint Development Partner Implementation Review Mission (2009), CitationJoint Development Partner Preparation Mission (2009), CitationJoint Development Partner Pre-Appraisal Mission (2009), CitationJoint Development Partner Mission (2010), and CitationJoint Development Partner Appraisal Mission (2010), all multi-donor missions with each funding agency represented.

9 There is uncertainty as to the accuracy and interpretation of agricultural data in Uganda. The last published agricultural census in Uganda was in 1965. Another census was carried out in 1990/91 but the results proved contentious and were never published. At the time of writing, full scale livestock and agricultural censuses have been in “an advanced stage” for nearly three years and the results are still eagerly anticipated. For more on the serious problems with agricultural data, see CitationZorya, Kshirsagar, and Gautam (2010).

10 In early 2008, an independent researcher described to one author a near riot in Tororo District where farmers were very unhappy to hear that their group activity work and budget had been replaced by the six-farmer model.

11 But no Political Economy Analysis (PEA) studies.

12 Internal World Bank memo by meeting participant.

13 Private letter from the Country Director to the Minister.

14 Personal communication with political scientist at Makerere University, September, 2011.

15 The Permanent Secretary of the Office of the Prime Minister was photographed in the Monitor ‘handing over eight tractors to farmers from northern Uganda’ (31/10/08) while, on 10/9/08, the paper had reported a ‘gift bonanza’ in Kanungu district when the President ‘dished out’ pick up trucks to four different farmers, tea seedlings and cash to others.

References

- Barkan, J. (2011, June). Uganda: Assessing risks to stability. A CSIS report..

- S. Benin . Agricultural growth and investment options for poverty reduction in Uganda. 2007; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington

- S. Benin . Impacts of and returns to public investment in agricultural extension: The case of the NAADS programme in Uganda. 2009; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington IFPRI Research Report.

- E. Berg . Why aren’t aid organizations better learners?. 2000; EGDI Group: Stockholm

- Birdsall, N. (2004). Seven Deadly sins: Reflections on Donor Failings. Working Paper Number 50. Washington: Center for Global Development..

- D. Booth . Are PRSPs making a difference. The African Experience. Development Policy Review. 29(1): 2003; 131–159.

- D. Booth . Aid institutions and governance, what have we learned?. Development Policy Review. 29(S1): 2011; 5–16.

- K. Botchwey . External evaluation of the ESAF. Report by a group of independent experts. 1998; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC

- Brautigam, D. (2000). Aid Dependence and Governance, EGDI paper, 2000:1. Stockholm: Almqvist og Wiksell International..

- B. Cooksey . Marketing reform? The rise and fall of agricultural liberalisation in Tanzania. Development Policy Review. 21 2003; 67–91.

- G. Dijkstra . The PRSP approach and the illusion of improved aid effectiveness: Lessons from Bolivia, Honduras and Nicaragua. Development Policy Review. 23(4): 2005; 443–464.

- A. Duncan , G. Williams . Making development assistance more effective through using political-economy analysis: What has been done and what have we learned?. Development Policy Review. 30(2): 2012; 133–148.

- J. Faust . Policy experiments, democratic ownership and development assistance. Development Policy Review. 28(5): 2010; 515–534.

- GoU . Plan for modernization of agriculture. 2000; Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries: Entebbe

- GoU . Uganda: Agriculture sector public expenditure review, Phases 1 and 2. 2007; Oxford Policy Management: Kampala

- GoU/EPRC . Uganda: Agriculture sector public expenditure review, Phase 3. Draft. 2009; Makerere University: Kampala

- W. Hout . The anti-politics of development: Donor agencies and the political economy of governance. Third World Quarterly. 33(3): 2012; 405–422.

- ITAD . NAADS Performance Evaluation. 2008; ITAD: Brighton, UK

- Joint Development Partner Implementation Review Mission, ARTP II and NAADS, Aide Memoire, June 9–19, 2009..

- Joint Development Partner Preparation Mission, Agriculture Sector Support, Aide Memoire, September 29–October 8, 2009..

- Joint Development Partner Pre-Appraisal Mission, Aide Memoire, Agricultural Technology and Advisory Services Project, December 7–18, 2009..

- Joint Development Partner Mission for the Technical Assessment of the Proposed Agricultural Technology and Agribusiness Advisory Services. Aide Memoire, March 9–19, 2010..

- Joint Development Partner Appraisal Mission for the Proposed Agricultural Technology and Agribusiness Advisory Services (ATAAS), Aide Memoire, April 16–23, 2010..

- Joint Identification Mission of the Agricultural Technology and Advisory Services Programme (ATAS), Aide Memoire, June 9–20, 2008..

- J. Joughin , A.M. Kjær . The politics of agricultural policy reform: The case of Uganda. Forum for Development Studies. 37(1): 2010; 61–79.

- A.M. Kjær , O. Therkildsen . Elections and landmark policies in Uganda and Tanzania. Democratization. i-first 2012; 1–23.

- J. Lazarus . Participation in Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers: Reviewing the past, assessing the present and predicting the future. Third World Quarterly. 29(6): 2008; 1205–1221.

- S. Maxwell . Heaven or Hubris: Reflections on the New ‘New Poverty Agenda’. Development Policy Review. 21(1): 2003; 5–25.

- T. Mkandawire , A. Olukoshi . Between liberalisation and oppression. The politics of structural adjustment in Africa. 1995; Codesria Book Series: Dakar

- T. Mkandawire , C.C. Soludo . Our continent, our future. 1999; Codesria, Africa World Press, Inc: Dakar

- Y. Museveni . What is Africa’s Problem?. 1992; NRM Publications: Kampala

- A.M. Mwenda , R. Tangri . Patronage politics, donor reforms, and regime consolidation in Uganda. African Affairs. 104/416 2005; 449–467.

- S. Nahdy . Decentralisation of services in Uganda: The formation of National Agricultural Advisory Services (NAADS). 2002; Kawanda Agricultural Research Institute: Kampala At http://www.ilri.org/InfoServ/Webpub/fulldocs/South_South/Theme5_4.htm .

- NRM . Prosperity for all, transformation and peace. National resistance movement election manifesto. 2006; NRM: Kampala

- OECD . The Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness and the Accra Agenda for Action. 2008; OECD: Paris

- Oxford Policy Management . The evaluation of the plan for the modernisation of agriculture. 2005; Oxford Policy Management: Oxford

- Oxford Policy Management . The Evaluation of Uganda’s Poverty Eradication Action Plan (PEAP). 2008; Oxford Policy Management: Oxford

- O. Therkildsen . Pushing for agricultural transformation. Irrigated rice in Tanzania. Presentation at the EPP workshop in Dar es Salaam. January 18–21, 2011 2011

- J. Thomas , M.S. Grindle . After the decision: Implementing policy reforms in developing countries. World Development. 18(8): 1990; 1163–1181.

- A.M. Tripp . Museveni’s Uganda. Paradoxes of Power in a Hybrid Regime. 2010; Lynne Rienner: Boulder

- Ugandan Bureau of Statistics . The 2005/06 Uganda National Household Survey (UNHS). 2007; Government Printer: Kampala

- UBOS. (2008). The Uganda Demographic and Health Survey, 2006..

- L. Whitfield . The politics of aid: African strategies for dealing with donors. 2009; Oxford University Press: Oxford

- World Bank. (2010). Project Appraisal Document, Agricultural Technology and Agribusiness Advisory Services Project, May 26, 2010..

- R.K. Yin . Case Study Research. Design and Methods. 1989; Sage: Newbury Park

- S. Zorya , V. Kshirsagar , M. Gautam . Agriculture for inclusive growth in Uganda. 2010; AFTAR, Sustainable Development Network: Africa Region Draft.