Abstract

With the increasing influence of New Public Management, such narratives as payments for ecosystem services and ecological networks are gaining global popularity in natural resource management. Promoted by transnational actors, these narratives have been introduced in Vietnam and have inspired a number of projects. The ensuing politics of multi-level governance triggered conflict and cooperation in adversarial policy process and deserve greater attention from environmental policy scholars. In this paper we advance a framework to analyze such processes from an agency perspective and contend that policy actors engage in three types of strategies in their policy work: (1) scale-based strategies of seeking support across governance scales; (2) meaning-based strategies of linking narratives to other concepts and discourses; and (3) context- based strategies of engaging with the policy context at multiple sites of governance. We illustrate these strategies with examples from the Ba Be and Na Hang protected areas in Vietnam.

1 Introduction

The process whereby global policy narratives penetrate the national and local levels is both ubiquitous and complex. A number of scholars within diverse social sciences disciplines have attempted to study this process, such as the schools of policy transfer (e.g. CitationStone, 2004), policy translation (CitationMukhtarov, 2012; Stone, 2012), and institutional transplantation (e.g. CitationDe Jong, Lalenis, & Virginie, 2002). While each of these schools contributes to understanding the phenomenon from its particular angle, the conceptual and empirical work still continues to develop. The complexities of such policy narrative “travel” stem from the dynamics of knowledge typified in abstract models which play out in situated contexts of a country where this knowledge is applied. While much has been discussed in terms of the determinants and theories of such process, relatively little attention has been paid to the role of individual and collective actors in developing and disseminating conservation narratives across governance scales. This paper addresses this issue by proposing a conceptual model for studying and analysing the role of individual and group actors in the process of translating global policy narratives to national and local contexts. We propose an agency-based framework and illustrate this with the narratives of ecological networks and payments for ecosystem services (PES) in the Ba Be and Na Hang protected areas (PAs) in Northern Vietnam.

We understand global conservation narratives as discourses which can be defined as “ensemble[s] of ideas, concepts and categories through which meaning is given to social and physical phenomena, and which [are] reproduced through an identifiable set of practices” (CitationHajer, 1995: 44). Among others, prominent global narratives in biodiversity conservation include fortress conservation, community co-management, ecological networks, and PES (CitationCampbell, 2002).

Global conservation narratives do not emerge or fade away of their own accord. Instead, transnational actors routinely propagate them at the international arena (CitationRomero & Andrade, 2004), whilst “local actors contest, re-configure and re-appropriate global ideas to suit their own situations” (CitationBücher & Whande, 2007: 25). While it is well known that panaceas do not exist in the field of environmental conservation (CitationIngram & Lejano, 2009), global conservation narratives by their very nature promote generic solutions and are presented as applicable to a variety of contexts. Conservation narratives can be seen as “nirvana concepts”, a term coined by CitationMolle (2008: 132) to refer to concepts “that embody an ideal image of what the world should tend to”. The danger of “nirvana concepts” is in the uncritical appeal they present to scholars and policy makers. The lack of positive impacts on the ground in terms of implementation of “nirvana concepts” from the water policy arena, such as Integrated Water Resources Management or Water User Associations, convincingly demonstrate the dangers hidden in the appeal of such generic concepts (CitationMolle, 2008). In this paper, we discuss the fate of two global conservation narratives: ecological networks and PES. The ecological networks narrative is rooted in understanding PAs as islands of rich biodiversity connected in ecological networks. Sometimes referred to as “landscape ecology”, this narrative advocates the creation of interlinked hubs with highly rich biodiversity. CitationJongman (1995:171) describes this approach as follows: “(e)cological corridors facilitate exchange between nature areas. They can consist of whole landscapes, large stepping stones such as wetlands, natural elements in agricultural landscapes such as wooded banks, small forests, streams and ditches and artificial pass-ways”. The World Summit on Sustainable Development in 2002 called for “the promotion of national and regional ecological networks and corridors” in order to significantly reduce the rate of biodiversity loss (CitationBennett, 2004).

The second narrative, PES, falls under so-called “neoliberal approaches to conservation”, which have gained prominence since the 1990s and encompass such instruments as environmental taxes, eco-tourism and biodiversity offsetting, among many others (CitationBücher & Whande, 2007). In its ideal form, PES represents “voluntary transaction[s] where a well-defined environmental service (ES) is traded between the provider of the service and the buyer, given that the provider secures ES provision conditionally” (CitationWunder, 2005). In practice, however, PES schemes can take a variety of shapes and forms. Among other uses, PES has been promoted as a solution to reduce environmental degradation and greenhouse gas emissions in the context of climate change, while simultaneously benefitting local populations, for instance through the United Nations programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD).

There is rich literature associated with the emergence of global conservation narratives and the roles of various actors in this process (e.g. CitationAgrawal, 2001; Bücher & Whande, 2007; Ostrom, 1990; Seixtas & Davy, 2008). Scholars have looked at the role of transnational policy entrepreneurs in constructing and promoting global discourses (CitationConca, 2006; Hajer, 1995; Mukhtarov, 2009) and national level policy entrepreneurs working primarily at the national level (CitationBrouwer & Biermann, 2011; Huitema & Meijerink, 2009, 2010). However, as CitationStone (2008: 34) remarks: “while there is a burgeoning literature on policy entrepreneurs, it tends to focus on the roles of such individuals at local and national levels of governance.” Little is known about the role of individual and collective actors in translating global narratives to particular national and local contexts, and the extent to which transnational policy actors exercise influence on national policy and practice.

To fill these gaps, this study pays explicit attention to the role of transnational policy actors in translating global conservation narratives into the policy context of Vietnam. Transnational policy actors operate at distinct levels. First, by integrating experiences from around the world, they produce generic storylines and normative guidelines for better biodiversity policies at national and sub-national levels. Second, transnational actor networks engage in active promotion of global narratives in individual countries in close interaction with national and local level actors through development assistance projects, trainings and conferences (CitationLendvai & Stubbs, 2009; Mukhtarov, 2009; Walt, Lush, & Ogden, 2004).

Informed by this literature, as well as the work on transnational change agents and their strategies (CitationBetsill & Bulkeley, 2004; Brouwer & Biermann, 2011; Huitema & Meijerink, 2009, 2010; Mukhtarov & Gerlak, 2013), we derive three sets of strategies which transnational policy actors may use in promoting global narratives in individual countries. We illustrate our framework with examples of PES and ecological networks from Vietnam. In paying attention to the individual and collective actors we take an agency-based approach. While recognizing the importance of the institutional environment and political economic structures in policy development and implementation, we assume that policy actors have a certain degree of freedom to shape institutions and decide on policy issues. Therefore, we focus on actors rather than the context and structures.

The transfer of technologies, infrastructure and political and economic instruments is always based on ideas, discourses and ideologies as well as particular interests and motivations. For the study of technology transfer and policy translation, the examination of underlying narratives and actors is therefore indispensable. By theorizing on agency to studying the translation of conservation narratives to the national context, we also contribute to the discussion of technology and infrastructure transfer presented in other articles of this special issue.

Section two of this paper elaborates on the theoretical framework for this study which consists of multi-level governance and an agency approach of policy entrepreneurs. Section three introduces the background of conservation policy in Vietnam, the research sites of Ba Be and Na Hang and the methods of research. Section four is devoted to the analysis of actors and strategies, and section five summarizes and concludes the paper.

2 Multi-level governance and agency in conservation policy

2.1 Multi-level governance

The concept of multi-level governance emerged from European studies (see CitationJordan, Huitema, van Asselt, Rayner, & Berkhout, 2010) and initially served to investigate how “supranational, national, regional, and local governments are enmeshed in territorially overarching policy networks” (CitationMarks, 1993: 402–3). The multi-level dimension refers to the existence of several levels of policy in addition to the national, whereas governance refers to the importance of non-state actors and policy networks vis-à-vis the state (CitationBache & Flinders, 2004: 3). The term governance is attractive to scholars due to its ability to “cover the whole range of institutions and relationships involved in the process of governing” (CitationPierre & Peters, 2000: 1). Governance in this sense concerns “the ways and means in which the divergent preferences of citizens are translated into effective policy choices, about how the plurality of societal interests are transformed into unitary action and the compliance of social actors is achieved” (CitationKohler-Koch, 1999: 14). The shift from the omnipotent state to the multiplicity of actors is the most profound feature of governance, providing greater space for iterative negotiations among the actors (CitationHajer & Versteeg, 2005). Thus, multi-level governance can essentially be seen as the process of negotiation among actors; as such, a study of agency in this process is indispensable for understanding it. The next section introduces the concept of agency and the debates around it.

2.2 An agency-perspective in multi-level governance

Agency is the ability to exercise authority and influence policy change (CitationDharwadkar, George, & Brandes, 2000; Eisenhardt, 1989; Eisner, Worsham, & Ringquist, 1996; Pattberg & Stripple, 2008). The agency approach does not ignore or downplay the importance of governance architecture and institutional environment; however, it asserts that there is value in studying individual and collective policy actors and their actions to shape and transcend the institutional environment within which they operate. According to CitationStripple and Pattberg (2010), the concept of agency is intrinsically linked to the concept of policy change as actors become change agents only if they are able to influence the course of policy events. Although there is a growing interest in multi-level governance in the nature management domain, surprisingly little research has been conducted on agency. The literature on protected areas (PA) management is mainly focussed on institutional prescriptions (CitationArmitage, 2008 Footnote1; CitationBarrett, Lee, & McPeak, 2005; Hayes, 2006; Ostrom, 1990) and dominated by the common property theory (CitationBerkes, 2002; Ostrom, 1990), political ecology (CitationArmitage, 2008; Lebel, Daniel, Badenoch, Garden, & Imamura, 2008), and social-ecological systems and resilience research (CitationFolke, Hahn, Olsson, & Norberg, 2005; Treves, Holland, & Brandon, 2005). These approaches privilege structures and institutions over an explicit focus on individuals and their actions.

The agency approach emphasises the role of individuals and groups that seek policy change. They may be called “change agents”, “policy advocates”, “boundary spanners”, “visionary leaders”, “norm entrepreneurs”, or “message entrepreneurs” (CitationBrouwer & Biermann, 2011; Huitema & Meijerink, 2009, 2010)–subtle differences tell them apart. We follow CitationKingdon (1995) and more recent scholarship on such agents (e.g. CitationHuitema & Meijerink, 2010; Mukhtarov & Gerlak, 2013) in referring to these individuals as policy entrepreneurs. Policy entrepreneurs instigate, implement and at times resist policy change proposals.

2.3 The policy entrepreneurs and strategies framework

The literature on policy entrepreneurs offers various strategies that policy actors may use in order to pursue policy change proposals. CitationHuitema and Meijerink (2010) suggest a framework in which policy entrepreneurs may engage with five strategies: coalition building, networking, venue shopping, idea generation and using windows of opportunity. In their paper, CitationBrouwer and Biermann (2011) categorized strategies into attention seeking, linking, relation management and arena strategies. Building on this literature, and drawing from the discourse perspective, we suggest three groups of strategies that translational policy entrepreneurs may use in promoting global narratives in national or sub-national contexts. These strategies are: (1) scale-based strategies, which emphasize the importance to target narratives at multiple venues across scales of governance, construct problems and solutions as pertinent to a certain geographical scale, and engage in networking and coalition-building that span scales of governance; (2) meaning-based strategies, which underline the importance of developing ideas and linking them to narratives and dominant ideas in a policy setting in the quest for legitimacy, as well as presenting them in a politically palatable way; and (3) context-based strategies, which imply the necessity to understand the context in which narratives are advanced and may involve enrolling some actors in coalitions while excluding others, as well as keeping alert to opportunities to advance policy initiatives at a particular time and place. presents these three groups of strategies.

Table 1 Strategies of transnational policy entrepreneurs to advance narratives in individual countries.

By drawing attention to scale, we borrow from CitationNeumann (2009: 399) who encourages examination of the “scalar practices of social actors” rather than choosing scale as an analytical category. Consequently, local is the scale of governance, but may also provide the context for policy entrepreneurs. We recognize the interconnectedness of scale and context, but suggest that in our conception, not all that is local is necessarily part of the context for policy entrepreneurs, while the policy context of biodiversity conservation is not exclusively local and may include national actors or a certain history of interaction between actors at multiple scales. The next section introduces the conservation policy background of Vietnam as well as information on the case study areas and sets the background to the discussion of actors and strategies in the political process around the narratives.

3 Biodiversity conservation in Vietnam: background, research sites and methods

3.1 Conservation policy background and narratives in Vietnam

The political culture in Vietnam is not only shaped by the communist ideology, but also older cultural orientations and inclinations (CitationMongabay, 2013 based on Library of Congress). Over the last 20 years, starting with the introduction of economic liberalization policy of Doi Moi in 1986, the country has undergone a gradual reform, transitioning from an inward-looking planned economy towards a globalized market economy (CitationWorld Bank, 2012). Reforms have also touched upon the issues of land management and conservation with decentralization of decision-making from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD) to the provincial government and specially created protected area management boards (CitationSikor, 2007). At the moment, the socialist party is clearly embedded in the society; however, it does experiment, compromise and develop consensus among its members to arrive at decisions (CitationBeresford, 2008). Furthermore, the decision-making culture of Vietnam is more complex than some models of monolithic party control would suggest (CitationWells-Dang, 2010). Under the conditions of opening political space, the redefinition of state–society relations is essential for understanding the dynamics of plural and intertwined political spaces in Vietnam (CitationWells-Dang, 2010).

Since the late 1990s, transnational actors have implemented a number of conservation projects in northern Vietnam in order to introduce PES and ecological networks models (CitationBouma, Joy, Lan, Ramirez, & Steyn, 2013; McElwee, 2012; UNDP, 2004). Vietnam has signed and ratified several international treaties, such as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), and has developed a programme for growing the number of PAs to 126 across the country (CitationCBD, 2012). The 2008 biodiversity law, which was the watershed law in environmental legislation of Vietnam, established the legal foundation for PAs and nature conservation zones, divided into national parks, nature reserves, species and habitat conservation areas and landscape conservation areas (CitationThe National Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, 2008). Since then, a number of decrees have mentioned or legalized the narratives with which we are concerned in this paper.

Vietnam is one of the first Southeast Asian countries to engage with PES, manifested in designated legislation and policy guidance (CitationDecree 99/2010/ND-CP of the Government, 2010). Transnational policy entrepreneurs such as the World Bank, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Global Environmental Facility (GEF), German Development Assistance (GIZ), United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the International Union for Conservation of Nature, and others support PES in Vietnam and see this policy instrument as a way to finance protected area management (CitationMcElwee, 2012). The International Fund for Agriculture Development (IFAD) originally introduced PES in Vietnam through the representative office of RUPES (CitationThe & Ngoc, 2008). Two pilot PES schemes have been implemented in the provinces Lam Dong and Son La since 2008 with numerous new projects launched in the recent years (CitationJanssen, 2011). Among others, Na Hang Nature Reserve and Ba Be National Park in Northern Vietnam are considered by the government and transnational policy entrepreneurs as possible sites for further PES projects. PES has already been introduced in Bac Kan through the Rewarding Upland Poor for Environmental Services (RUPES) project (CitationGuignier & Rieu-Clarke, 2012; Janssen, 2011).

The landscape ecology approach and the possibility of establishing corridors between protected areas are reflected in the new biodiversity law (CitationThe National Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, 2008). The project implemented by Flora and Fauna International in Pu Luong-Cuc Phuong limestone landscape conservation project provided the precedent of the inter-provincial ecological network. Here, we explore how the idea of integration of Ba Be and Na Hang into a single nature conservation complex has emerged and the role that transnational actors played in this process. The UNDP-GEF funded project on Protected Areas and Resource Conservation (PARC) and the later developments with regard to Ba Be's application for the UNECSO World Heritage Site (WHS) status provide the frame within which this narrative is discussed.

3.2 Policy actors involved in conservation policy in Vietnam

A number of actors are prominent in the conservation policy of Vietnam. We follow CitationSeixtas and Davy (2008) in categorizing these policy entrepreneurs in four major groups: (i) local communities; (ii) government agencies; (iii) transnational actors (i.e. international organizations, NGOs and donors); and (iv) regional and national level civil society organizations (e.g. indigenous organizations and national NGOs). lists the main policy actors in the case areas in Vietnam.

Table 2 Policy Entrepreneurs in Vietnam.

3.3 Methods and research sites

This case study relies on a variety of data sources. First, to investigate the activities of transnational policy entrepreneurs in Vietnam, in 2010 and 2011 the authors interviewed a number of stakeholders involved in conservation policy, such as at the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MoNRE), MARD, the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (MCST), as well as transnational actors including (project) representatives of GIZ, UNDP/GEF, Forest Trends and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (CitationIUCN). Additionally, a number of national NGOs (e.g. CitationPan Nature), independent experts and officials from provincial and commune (village) level organizations have been interviewed, as well as farmers and their organizations.

In total, we conducted 64 qualitative interviews (Janssen and Mukhtarov) in two separate periods from September to November 2010 and May to June 2011, and analyzed the results. Our interview topics covered, among others, the origins of proposals for policy change, the involvement of transnational policy actors, and the means for involvement of local communities in the conservation initiatives. Furthermore, we asked direct questions about internationally funded projects in the area of Ba Be and Na Hang. In addition to the interviews, we collected and analyzed secondary sources. The very nature of this research requires in-depth qualitative analyses as these best capture the discourses and narratives which we study.

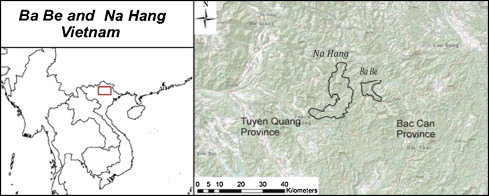

illustrates the maps of Ba Be and Na Hang; the location of the PAs within Vietnam is indicated in the figure on the left-hand side. Ba Be National Park, created in 1992, is situated in North East Vietnam and covers a total area of 44,750 ha. Ba Be National Park was recognized as ASEAN Heritage Park in 2004 and CitationRamsar site in 2011.Footnote2 The application of Ba Be National Park to become a World Heritage Site was rejected by IUCN in 2007 on the ground of insufficient authenticity of the landscape (CitationIUCN, 2007). Shifting cultivation, livestock grazing and over-exploitation of forest products are specifically threatening biodiversity conservation in the park. Na Nang is an adjacent nature reserve, which with 40,000 ha is much larger than Ba Be lake, and with rich biodiversity, including a “flag” species of snub-nosed monkey.

Source: Institute for Environmental Studies, VU University Amsterdam.

4 Discussion of actors and strategies in the politics of conservation narratives in Vietnam

4.1 Scale-based strategies

The UNDP, GEF and IUCN are the key actors who promoted ecological networks within the PARC project. Since the inception of the project in 1996, the managing director, Mr. Fernando Potess, has prioritized securing a broad base of supporters for the project. Having networked widely and across scale, Mr. Potess established links with government agencies, such as MARD and MoNRE, their provincial departments, as well as International NGOs such as IUCN. The project had four components: conservation management, resource use planning and forestry, community development, and conservation awareness and ecotourism (CitationUNDP, 2004).

It resulted in the establishment of the management board for Ba Be and Na Hang, as well as numerous pilot projects introducing agroforestry, community-based resource planning and the basic PA infrastructure investment. One of the main achievements of the project was the expansion of the protected area network. Through biodiversity surveys and hotspot analysis, PARC's landscape ecology approach led to the proposition to expand the protected area network in the conservation complex. This recommendation is based on the need to provide greater protection for the key species of conservation concern, to reduce forest fragmentation and to compensate for some of the habitat loss resulting from the Na Hang dam on the Gam River constructed near the park for hydropower purposes. Mr. Potess from the PARC project worked with provincial and district Forest Protection Departments to establish two new protected areas contiguous with Na Hang Nature Reserve (CitationUNDP, 2004: 5).

These two areas are the South Xuan Lac Species and Habitat Conservation Area and the proposed François’ Langur “Tu Cang” Species and Habitat Conservation Area. In addition, the PARC project proposed the merging of Ba Be and Na Hang into a single nature conservation unit administered by one management board (Potess, 2010, pers. comm.). This proposal is based on a local problem construction — ecosystem fragmentation is discursively constructed as the key problem in the area. Consequently, ecological networks are supposed to provide connectivity between areas within Ba Be and Na Hang. Furthermore, PARC suggested integrating the two PAs into one “Ba Be National Park — Na Hang Nature Reserve Conservation Complex” (CitationPARC Project, 2006). From an ecological point of view, PARC argued, the two protected areas share the same type of karst/limestone ecosystem and have similar biodiversity.

Predictably, the network of four protected areas, including Na Hang and Ba Be, did not find much support with the provincial government's representatives. The traditional authority of the Bac Kan province over Ba Be and of the Tuyen Quanq province over Na Hang meant that any consideration of integration was met with reluctance and fear of losing “the turf”. The proposal of the PARC project was therefore shelved and did not make it to the political agenda of the government. The UNDP and GEF have utilized scale-based strategies of coalition-building in order to align with IUCN as well as the Departments of Tourism in the two provinces, which see the potential for joint eco-tourism in the case of integration of the two areas (CitationGoV, 2009). However, two major barriers prevented this proposal from formal consideration, let alone implementation. First of all, there is a well-documented divide between MoNRE and MARD (CitationMolle, 2011). MoNRE, created by the Government Decree No. 91, has been granted the responsibility to “exercise the state function of management over the land, water resources, minerals, environment, meteorology, hydro geography, measuring and mapping at the national level” (GoV, 2002). While the responsibilities over the environmental protection and biodiversity lie with MoNRE, responsibility for forests belongs to MARD, which creates institutional confusion in the management of protected areas (CitationMolle, 2011). Additionally, competition between the Provincial People's Committees (PPCs) in Bac Kan and Tuyen Quanq provinces, where Ba Be and Na Hang are located, make the future administration of the joint protected area difficult. These barriers are also often found in other countries and areas and represent major challenges to ecosystem-based administration and management. The new GIZ project in the region, as well as the starting UNDP project on governance of protected areas, may provide new opportunities for the proponents of ecological networks to push the idea onto the political agenda using coalition-building (CitationGuignier & Rieu-Clarke, 2012).

In the case of PES, transnational policy entrepreneurs worked as a coalition which included actors such as GIZ,Footnote3 RCFEE,Footnote4 MARD, MoNRE, and government officials like the former Deputy Prime Minister Nguyen Sinh Hung. Decree No.99/2010/ND-CP on the policy for payment for forest environmental services (FPES) was put into effect on January 1, 2011 (CitationPan Nature, 2011). According to that legislation, the Vietnamese organizations and individuals benefiting from forest environmental services, such as maintenance of water sources for hydropower plants, water resources for production and living activities of the society, and eco-tourism, have to pay forest owners. The revenues go to the Vietnam Forest Protection and Development Fund or through the provincial Forest Protection and Development Funds (CitationPan Nature, 2011).

Coalition building with the local level has been difficult because communities have limited legal personality to enter into agreements according to the 2005 civil code (CitationVu Thu Hanh, Moore, & Emerton, 2013). Local communities, the potential service sellers, were not involved in the design and implementation of the PES scheme. Moreover, state departments as well as actors at the provincial and the commune level (one level lower from the provincial) including individual households, lack awareness about the PES scheme. In the interviews, they made it clear that they would only participate if it were profitable for them. This indicates the limited effort and success in getting a broad range of support for the PES schemes outside of the transnational actors-national government coalition (CitationMcElwee, 2012).

4.2 Meaning-based strategies

Transnational policy entrepreneurs (UNDP, GEF and IUCN) framed the major biodiversity loss issues in Ba Be and Na Hang as originating from ecosystem fragmentation due to the lack of corridors enabling the movement of animals between similar types of ecosystems, e.g. parts of tropical forests. This discourse offered the opportunity of framing the solution as ecological networks, in line with the initial landscape ecology approach of the project.

When introducing PES into the Vietnamese context, and more specifically to Ba Be and Na Hang, insufficient attention was paid to different understandings of the concept and to what it would take to enact PES in the post-communist context of Vietnam.

Two major components of the PES scheme in Vietnam are different from PES’ theoretical underpinnings. First, in the interpretation by the Vietnamese government, PES is considered a mandatory instrument to raise additional finances, whereas in the literature on PES it is viewed as a voluntary mechanism (CitationJanssen, 2011). Interestingly, the GIZ representative argued that the involvement of the government of Vietnam in the implementation of PES is favourable as the culture of top-down decision-making requires state orders for actors to enact any legislation (GIZ 2011, pers. comm.). Another issue is the level of payment, which is not determined by the market but prescribed by the government. Decree 99 stipulates the amount a service buyer has to pay to service providers. The minimum level of payments according to Decree 99 is 20 VND*kWh. This level of payment is formed through a forest valuation study in the pilot sites Lam Dong. According to our interviews with representatives of MARD and the Na Hang hydropower plant, no company will voluntarily pay more than this minimum amount. According our interview with a RCFEE representative (2011, pers. comm.), this minimum amount is too small and the government is unlikely to increase it in the view of possible resistance from the private sector.

A respondent from the hydropower plant stated in an interview that the company is waiting for guidelines to implement PES which must come from MARD. Therefore, PES schemes in the Na Hang Nature Reserve will not be in place until the guidelines are available (Na Hang power plant 2011, pers. comm.). Our observations on PES in Na Hang correspond to those made by CitationMcElwee (2012: 419). According to her, “the market-oriented aspect of PES has been downplayed in Vietnam in favour of a continued strong role for the central and local governments, both as buyers and as sellers […] but also in forming even the most basic parameters for the PES market”.

The potential ecosystem buyers, on the other hand, are two companies: the Na Hang Hydropower company and the Centre of Rural Water Supply and Sanitation and Environment (CRWSSE). A CRWSSE representative (2011, pers. comm.) stated that the company had not been informed about the scheme at all and “is only interested in joining PES schemes if the government pays them money to cooperate”. Clearly, they view PES as yet another government order. This means that PES has taken a very different shape in Vietnam than in theory and the meaning of it has been modified despite the preservation of the label.

4.3 Context-based strategies

The knowledge of the context, the right timing for targeting change and relational sensitivities are factors which actors seeking political change cannot afford to ignore. While the manager of the PARC project has engaged in networking and coalition-building, it has been more challenging to garner support for the idea of ecological networks in Ba Be and Na Hang. Such proposals for ecosystem based management meet resistance all over the world from conventional bureaucracies which operate according to administrative units, and the fate of the proposal is not explained fully due to inappropriate strategies used by policy entrepreneurs. Furthermore, the short-term duration of the PARC project has limited its possibilities of securing broad support to this idea. However, the limited power of the PARC management to cultivate change has been boosted by smart cooperation with IUCN, which made use of the window of opportunity to advance the idea of ecological networks a few years later. When Ba Be applied for the UNESCO World Heritage Site conservation status, IUCN, which operated the assessment, recommended that the proposals of the PARC project should be reconsidered:

IUCN considers that the nominated property does not meet this criterion [on biodiversity and threatened species]. IUCN acknowledges, however, that a future nomination of a much larger area that includes the full range of biodiversity value of the Ba Be/Na Hang Conservation Complex might have greater potential to meet this criterion […] Such an approach should draw upon the recommendations of the Creating Protected Areas for Resource Conservation Using Landscape Ecology (PARC) Project which advocate for a Ba Be National Park - Na Hang Nature Reserve Conservation Complex (CitationIUCN, 2007: p41).

With the PES narrative, the transnational policy entrepreneurs who advanced the instrument of PES in Vietnam, i.e. RCFEE, GIZ, and IFAD, did not anticipate that the top-down administrative system could modify the PES instrument to such an extent that it did not even resemble the very idea of PES any more. The centralized approach to PES in this particular governance-context has resulted in little awareness and support of the scheme by potential buyers in Na Hang and Ba Be, the Na Hang Hydropower plant and the Centre of Rural Water Supply and Sanitation and Environment (CRWSSE), who appear to lack understanding of the rationale behind PES (CitationJanssen, 2011). Our interviews as well as writings of other scholars on the subject demonstrate that PES has been transformed in Vietnam beyond recognition (CitationMcElwee, 2010, 2012). below presents the types of policy entrepreneurs and strategies that they used in promoting PES and ecological networks in Vietnam.

Table 3 Strategies and narratives in conservation policy in Vietnam.

5 Conclusions

In this study we explored two issues. First, we discussed the performance and appropriateness of global conservation narratives in specific conditions of Vietnam. Second, we discussed the types of policy entrepreneurs and strategies they used in the process of introducing global conservation narratives to Vietnam. Three findings emerge from this study.

Firstly, it is clear from our analysis that the most influential type of policy entrepreneurs in our particular case is transnational actors. Having entered into a coalition with national government agencies, these actors excelled in meaning-based and scale-based strategies, and to a lesser extent, in context-based strategies. The accountability of the coalition of transnational policy entrepreneurs and the national government may raise questions, and neither international nor Vietnamese civil society organizations provide sufficient scrutiny to their work. Other actors, such as civil society actors or local communities, had little opportunity to engage with any of the strategies at all. By framing PES as a financially beneficial technocratic instrument, transnational policy entrepreneurs have been successful in advocating the idea to the national government. By the framing of ecological networks approach in technical terms of landscape ecology, the PARC project management has been less successful than in the case of PES, although the process of negotiation is not completely finished.

Secondly, in spite of the disproportionate power of transnational policy entrepreneurs to utilize strategies, the coalition of transnational actors and the government of Vietnam failed to account adequately for the context in choosing and promoting conservation narratives to Vietnam. Neither the proposal for ecological networks, nor for PES reflected the specificities of the Vietnamese political system, socio-economic development and cultural heritage (see also CitationMcElwee, 2012). This may be linked to the lack of involvement of local communities in decision-making as this could have laid ground for better knowledge of the context. Local communities, the keepers of indigenous knowledge, have had no say in the development of both policy instruments, ironically intended to improve their lives. This exclusive and patronizing attitude has also been observed by other scholars working in Vietnam and is the major issue to solve if conservation efforts are to become more effective (CitationMcElwee, 2010, 2012; Zingerli, 2005).

Thirdly, we observed that while contextual relevance is important, it is also beyond the power of actors to account for it fully. The contingency of how context will influence actions and policy change proposals is such that incrementalism advocated by CitationLindblom (1959) and adaptive governance scholars more recently (e.g. CitationHuitema et al., 2009) needs consideration. While greater involvement of local communities in feasibility studies, deliberation and implementation of policy instruments would certainly help in reconciling the conservation narratives and problems on the ground, expecting that such strategic considerations will eliminate contingency and lead to change exactly as planned is unrealistic. The fact that PES has been modified to fit the reality of Vietnam is a testimony to inevitable transformation of policy instruments to reflect new environments (CitationFreeman, 2009; Mukhtarov, 2012).

Naturally, this study has limitations. Our data is limited to Ba Be and Na Hang protected areas, and some of the findings may not be generalizable to Vietnam as a whole. Moreover, while having attempted to interview stakeholders from as wide a range as possible, we have not had exposure to civil society actors and local communities in Vietnam to the extent we desired. However, despite the challenges of conducting field research in Vietnam, the number and diversity of interviews, observations and the extent of academic and policy literature reviewed allow us to advance our propositions with confidence.

Acknowledgements

Hans de Moel of the Institute of Environmental Studies, VU Amsterdam has been very helpful in drawing Fig. 1. Funding for this paper came from FP7 program ENV.2007.2.1.4.3 Biodiversity values, sustainable use and livelihoods, LiveDiverse Project 211392. We would like to thank Ian van der Vlugt for editorial assistance and four anonymous reviewers for useful suggestions on earlier drafts of this paper.

Notes

1 For example CitationArmitage (2008) suggested the following institutional prescriptions for natural resources management: multi-layered institutions, accountability, interactivity, leadership, knowledge pluralism, learning, trust and networks.

2 The Ramsar Convention recognized Ba Be on February 2, 2011, as a wetland of international importance (CitationRamsar, 2012).

3 GIZ (German Agency for International Cooperation) is an important leader in the development of PES. The organization helped the government with technical assistance in the pilot projects and is still an important actor in guiding current PES schemes. Through the workshops GIZ organizes, which are open to different institutions, GIZ can influence the government into a certain direction. GIZ uses these workshops to convince their network into moving into this direction (CitationJanssen, 2011).

4 The Research Centre for Forest Ecology and Environment (RCFEE) has been favouring PES for many years. Through meetings with the government, RCFEE has been trying to convince the government to consider PES as a policy instrument to solve the environmental problems in the country. This research institute plays an important role in the realization of the pilot PES projects in the country, and is currently involved in other PES projects in Vietnam (CitationJanssen, 2011).

References

- A. Agrawal . Common property institutions and sustainable governance of resources. World Development. 29(10): 2001; 1649–1672.

- D. Armitage . Governance and the commons in a multi-level world. International Journal of the Commons. 2(1): 2008; 7–32.

- J. Bache , M. Flinders . Multi-level governance. 2004; Oxford University Press: Oxford, New York

- C. Barrett , D. Lee , J. McPeak . Institutional arrangements for rural poverty reduction and resource conservation. World Development. 33(2): 2005; 193–197.

- G. Bennett . Integrating biodiversity conservation and sustainable use: Lessons learned from ecological networks. 2004; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK

- M. Beresford . Doi Moi in review: The challenges of building market socialism in Vietnam. Journal of Contemporary Asia. 38(2): 2008; 221–243.

- F. Berkes . Cross-scale institutional linkages: Perspectives from the bottom up. E. Ostrom , T. Dietz , N. Dolšak , P.C. Stern , S. Stonich , E. Weber . The drama of the commons. 2002; National Academy Press: Washington, DC 293–321.

- M.M. Betsill , H. Bulkeley . Transnational networks and global environmental governance: The cities for climate protection program. International Studies Quarterly. 48(2): 2004; 471–493.

- J.A. Bouma , K.J. Joy , M. Steyn . Poverty, livelihoods and the conservation of nature in biodiversity hotspots around the world. P.J.H. van Beukering , E. Papyrakis , J. Bouma , R. Brouwer . Nature's wealth: the economics of ecosystem services and poverty. 2013; Cambridge University Press: New York 74–106.

- S. Brouwer , F. Biermann . Towards adaptive management: Examining the Strategies of policy entrepreneurs in Dutch water management. Ecology and Society. 16(4): 2011; 5–18.

- B. Bücher , W. Whande . Whims of the winds of time? Emerging trends in biodiversity conservation and protected area management. Conservation and Society. 5(1): 2007; 22–43.

- L.M. Campbell . Conservation narratives in Costa Rica: Conflict and co-existence. Development and Change. 33 2002; 29–56.

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) . Country profiles: Viet Nam — Main details (online). 2012. Available from: http://www.cbd.int/countries/profile/?country=vn Accessed 13.05.13.

- K. Conca . Governing water: Contentious transnational politics and global institution building. 2006; MIT Press: Cambridge, Massachussetts

- M. De Jong , K. Lalenis , M. Virginie . The theory and practice of institutional transplantation: Experiences with the transfer of policy institutions. 2002; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht

- R. Dharwadkar , G. George , P. Brandes . Privatization in emerging economies: An agency theory perspective. Academy of Management Review. 25 2000; 650–669.

- K.M. Eisenhardt . Agency theory: An assessment and review. Academy of Management Review. 14 1989; 57–74.

- M.A. Eisner , J. Worsham , E. Ringquist . Crossing the organizational void: The limits of agency theory in the analysis of regulatory control. Governance: An International Journal of Policy and Administration. 9 1996; 407–428.

- C. Folke , T. Hahn , P. Olsson , J. Norberg . Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 30 2005; 441–473.

- R. Freeman . What is ‘translation’?. Evidence & Policy. 5(4): 2009; 429–447.

- Government of Vietnam (GoV) United Nations Development Program, & Global Environmental Fund . Removing barriers hindering protected area management effectiveness in Viet Nam (PIMS 3965). 2009. UNDP Project Document. At: http://www.undp.org.vn/digitalAssets/27/27368_Protected_Area_Prodoc110124x.pdf (10.04.12).

- A. Guignier , A. Rieu-Clarke . Country report Vietnam. Payment for environmental services. IUCN-Academy of Environmental Law e-Journal. 1 2012; 251–259.

- M.A. Hajer . The politics of environmental discourse: Ecological modernization and the policy process. 1995; Oxford University Press: Oxford

- M. Hajer , W. Versteeg . A decade of discourse analysis of environmental politics: Achievements, challenges, perspectives. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning. 7(3): 2005; 175–184.

- T. Hayes . Parks, people, and forest protection: An institutional assessment of the effectiveness of protected areas. World Development. 34(12): 2006; 2064–2075.

- D. Huitema , S. Meijerink . Water policy entrepreneurs. A research companion to water transitions around the globe. 2009; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham

- D. Huitema , S. Meijerink . Realizing water transitions: The role of policy entrepreneurs in water policy change. Ecology and Society. 15(2): 2010; 26–35.

- D. Huitema , E. Mostert , W. Egas , S. Moellenkamp , C. Pahl-Wostl , R. Yalcin . Adaptive water governance: Assessing the institutional prescriptions of adaptive (co-) management from a governance perspective and defining a research agenda. Ecology and Society. 14(1): 2009; 26–44.

- H. Ingram , R. Lejano . Transitions: Transcending multiple ways of knowing water resources in the United States. D. Huitema , S. Meijerink . Water policy entrepreneurs. A research companion to water transitions around the globe. 2009; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham 61–78.

- International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) . World Heritage Nomination — IUCN Technical Evaluation. 2006; Ba Be National Park ID No.1249.

- International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) . IUCN Evaluation of Nominations of Natural and Mixed Properties to the World Heritage List. 2007; Christchurch: New Zealand

- S.A. Janssen . Payments for ecosystem services: A research on the opportunities and constraints for implementation in the Na Hang Nature Reserve in Vietnam. 2011; LiveDiverse, MSc thesis Environment and Resource Management: VU Amsterdam

- R.H.G. Jongman . Nature conservation planning in Europe: Developing ecological networks. Landscape and Urban Planning. 32(3): 1995; 169–183.

- A.J. Jordan , D. Huitema , H. van Asselt , T. Rayner , F. Berkhout . Climate change policy in the European Union: Confronting the dilemmas of mitigation and adaptation. 2010; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge

- J.W. Kingdon . Agendas, alternatives and public policies. 1995; Harper Collins: New York

- B. Kohler-Koch . The evolution and transformation of European Governance. B. Kohler-Koch , R. Eising . The transformation of Governance in the European Union. 1999; Routledge: London 14–35.

- L. Lebel , R. Daniel , N. Badenoch , P. Garden , M. Imamura . A multi-level perspective on conserving with communities: Experiences from upper tributary watersheds in montane mainland Southeast Asia. International Journal of the Commons. 2(1): 2008; 127–154.

- N. Lendvai , P. Stubbs . Assemblages, Translation, and Intermediaries in South-East Europe. S. Hodgson , Z. Irving . Policy reconsidered: Meaning, politics and practices. 2009; Bristol Policy Press: Bristol

- C. Lindblom . The Science of muddling through. Public Administration Review. 19(2): 1959; 79–88.

- G. Marks . Structural policy and multi-level governance in the EC. A. Cafruny , G. Rosenthal . The State of the European Community: The Maastricht Debate and Beyond. 1993; Lynne Rienner: Boulder 391–411.

- P.D. McElwee . Resource use among rural agricultural households near protected areas in Vietnam: The social costs of conservation and implications for enforcement. Environmental Management. 45(1): 2010; 113–131.

- P.D. McElwee . Payments for environmental services as neoliberal market-based forest conservation in Vietnam: Panacea or problem?. Geoforum. 43(3): 2012; 412–426.

- F. Molle . Nirvana concepts, narratives and policy models: Insights from the Water Sector. Water Alternatives. 1(1): 2008; 23–40.

- F. Molle . Implementing integrated river basin management in the Red River Basin, Vietnam: A solution looking for a problem?. Water Policy. 13 2011; 518–534.

- Mongabay . Vietnam — Government. 2013. Available at: http://www.mongabay.com/reference/country_studies/vietnam/GOVERNMENT.html Accessed 13.05.13.

- F. Mukhtarov . The hegemony of integrated water resources management: A study of policy translation in England, Turkey and Kazakhstan. 2009; Doctoral thesis, Department of Environmental Sciences and Policy, Central European University: Budapest

- F. Mukhtarov . Rethinking the travel of ideas: Policy translation in the water sector. Policy and Politics. 2012. Available from: http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/tpp/pap/pre-prints/15799 Accessed 13.05.13.

- F. Mukhtarov , A. Gerlak . River basin organizations in the global water discourse: An exploration of agency and strategy. Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations. 19(2): 2013; 307–326.

- R.P. Neumann . Political ecology: Theorizing scale. Progress in Human Geography. 33(3): 2009; 398–406.

- E. Ostrom . Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. 1990; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge

- Pan Nature . Policy brief. 2011. Quarter 1, issue 2, online. Available from: http://www.nature.org.vn/en/ Accessed 13.05.13.

- PARC Project . Policy Brief: Building Viet Nam's National Protected Areas System — policy and institutional innovations required for progress, Creating Protected Areas for Resource Conservation using Landscape Ecology. 2006; (PARC) Project VIE/95/G31&031, Government of Viet Nam FPD)/UNOPS/UNDP/IUCN: Ha Noi

- P. Pattberg , J. Stripple . Beyond the public and private divide: Remapping transnational climate governance in the 21st century. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics. 8 2008; 367–388.

- J. Pierre , B. Peters . Governance, Politics and the State. 2000; Macmillan: Basingstoke

- Ramsar . The Annotated Ramsar List: Viet Nam. 2012. Available from: http://www.ramsar.org/cda/en/ramsar-pubs-annolist-annotated-ramsar-15775/main/ramsar/1-30-168%5E15775_4000_0 Accessed 13.05.13.

- C. Romero , G.I. Andrade . International conservation organizations and the fate of local tropical forest conservation initiatives. Conservation Biology. 18(2): 2004; 578–580.

- C.S. Seixtas , B. Davy . Self-organization in integrated conservation and development initiatives. International Journal of the Commons. 2(1): 2008; 99–125.

- T. Sikor . Land reform and the State in Vietnam's Northwestern Mountains. J. Connell , E. Waddell . Environment, development and change in rural Asia-Pacific: Between local and global. 2007; Routledge: London 91–107.

- Socialist Republic of Vietnam . Decree on the Policy for Payment for Forest Environmental Services. 2010; Decree 99/2010/ND-CP: Ha Noi, September 24, 2010

- D. Stone . Transfer agents and the global networks in the “transnationalization” of policy. Journal of European Public Policy. 11(3): 2004; 545–566.

- D. Stone . Global Public Policy, Transnational Policy Communities and their Networks. Policy Studies Journal. 36 2008; 19–38.

- D. Stone . Transfer and translation of policy. Policy Studies. 33(6): 2012; 483–499.

- J. Stripple , P. Pattberg . Agency in global climate governance: Setting the stage. F. Biermann , P. Pattberg , F. Zelli . Global climate governance beyond 2012: Architecture, agency and adaptation. 2010; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge 137–145.

- B.D. The , H.B. Ngoc . Payments for environmental services in Vietnam: An empirical experiment in sustainable forest management. ASEAN Economic Bulletin. 25(1): 2008; 48–59.

- The National Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, Legislature XII, 4th session. Biodiversity Law. Law No. 20/2008/QH12..

- L. Treves , B. Holland , K. Brandon . The role of protected areas in conserving biodiversity and sustaining local livelihoods. Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 30 2005; 219–252.

- United Nations Development Program (UNDP) . Project of the Government of the Republic of Vietnam: Creating Protected Areas for Resource Conservation using Landscape Ecology (PARC): Report of the Final Evaluation Mission. VIE/95/G31. 2004. Available from: http://www.undp.org.vn/digitalAssets/9/9419_PARC.pdf Accessed 13.05.13.

- Vu Thu Hanh . P. Moore , L. Emerton . Review of Laws and Policies Related to Payment for Ecosystem Services in Viet Nam. 2013. IUCN. Available from: http://cmsdata.iucn.org/downloads/080310_pes_vn_legal_review_only_legal_sections_final.pdf Accessed 13.05.13.

- G. Walt , L. Lush , J. Ogden . International organizations in transfer of infectious diseases: Iterative loops of adoption. Adaptation, and Marketing Governance. 17 2004; 189–210.

- A. Wells-Dang . Political space in Vietnam: A View from the “rice-roots”. The Pacific Review. 23(1): 2010; 93–112.

- World Bank . Vietnam Overview. 2012. Available from: http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/vietnam/overview Accessed 13.05.13.

- S. Wunder . Payments for environmental services: Some nuts and bolts. CIFOR Occasional Paper No. 42. 2005. Available from: http://www.mtnforum.org/sites/default/files/pub/4613.pdf Accessed 20.04.12.

- C. Zingerli . Colliding Understandings of Biodiversity Conservation in Vietnam: Global Claims. National Interests, and Local Struggles. Society & Natural Resources. 18(8): 2005; 733–747.