abstract

The spread of quality assurance (QA) regimes in higher education has been an explosive phenomenon over the last 25 years. By one estimate, for example, half of all the countries in the world have adopted QA systems or QA regulatory agencies to oversee their higher education sector. Typically, this phenomenon is explained as a process of policy diffusion, the advent of marketization, the spread of neoliberalism, massification and, concomitantly, the emergence of a ‘global market’ for higher education, prompting governments to respond by validating standards, quality, and introducing certification and compliance regimes. In this paper I question the utility of these explanatory frameworks, specifically looking at the case of Hong Kong in order to explore the role coercive institutional isomorphism plays in policy adoption and the implications of this for regulatory performativity.

1 Introduction

The changing nature of public administration over the last three decades has been variously depicted as a shift from government to governance. Theorists as diverse as CitationJessop (2002), CitationHarvey (1990, 2005), CitationBeck (1999), CitationHood (2004), CitationHood and Scott (1996), CitationMajone (1997), CitationLevi-Faur (2005, 2011, 2013), CitationSandel (2012), and CitationLodge (2008) — among others, have all reflected on the underlying forces prompting this transition as well as the institutional forms it has assumed. Harvey and Jessop, for example, see this transition as a functional outcome of late capitalism and the movement to post-fordist regimes of accumulation, requiring fundamental transitions in the organization of the state and its fiscal and managerial practices in order to accommodate capital. Hood, Majone, Lodge and Levi-Faur chronicle the demise of the Keynesian state prompted by concerns about governmental efficiency, changing ideational attitudes about the expanse of the state relative to markets, and new approaches to public management where the incorporation of market practices has reinvented government through regulation. For Sandel and Beck the dominant institutional forms of the post-Keynesian state emerge in the instrumental application of market forces to an ever widening set of economic, political, and social domains and the transition to market societies (see also CitationBrenner, Peck, & Theodore, 2010a, 2010b; Polanyi, 1957).

While epistemologically diverse all these approaches situate governance in the increasingly ubiquitous ‘regulatory state’ (CitationLevi-Faur, 2013) — a moniker that captures three elements. First, a political or ideological moment that defines the distribution of power, the allocation of authority, and proscribes the discourse of management within the domain. Second, the specification of an institutional architecture and processes of technocratic administration situated in ‘evidenced based’ decision making and stakeholder engagement. Third, the specification of the meta-environment for regulatory performativity, including rules and systems of jurisprudence for the allocation of costs, risks and rewards, and the meta-normative principles that define accountability, performance, measurement, legitimacy and transparency (CitationBlack, 2000, 2007, 2008).

Collectively, these two grammars (the epistemological and technical) comprise the now dominant and expansive literatures that address governance by regulation. In this paper I utilise these two grammars as quasi hypotheses in an attempt to explain and understand the emergence of a regulatory regime for quality assurance (QA) in the higher education sector in Hong Kong, and the technical performativity of the regime in terms of its efficiency and impact on quality assurance outcomes. The basic tenet of the paper is that Hong Kong is an outlier in terms of epistemological grammars explaining the emergence of a regulatory regime for QA in higher education and is better understood in the context of institutional isomorphism — specifically ‘coercive’ institutional isomorphism following CitationDiMaggio and Powell (1983). Further, the regulatory regime for QA in higher education in Hong Kong is atypical compared to its international counterparts. While it reflects international regulatory norms associated with institutional agentification these compete with parallel authority structures embodied in powerful and highly hierarchical ‘command and control’ administrative traditions but which are situated amid a grammar of ‘regulation inside of government’ following Hood's (CitationHood, James, Jones, Scott, & Travers, 1999), CitationLodge and Wegrich's (2012, pp. 120–136) typology. The result, I argue, is a bifurcated regulatory regime that limits regulatory effectiveness and sector outcomes.

The article is organized into three parts. The first addresses three epistemological grammars of regulatory capitalism. I contrast these now dominant epistemological grammars with institutionalist perspectives, specifically coercive institutional isomorphism, as a potentially superior means for understanding the adoption of a QA regulatory regime in the Hong Kong context. In Section 2 I trace the evolution and configuration of the regulatory regime for QA in higher education in Hong Kong, the nature of its adoption and implementation, and outline its institutional features and the articulation of regulatory practices. In Section 3 I turn to the issue of regulatory performativity and offer some concluding observations on sector outcomes, regulatory performance and the role of coercive institutional isomorphism in the regulatory landscape of the higher education sector in Hong Kong.

2 The global diffusion of regulatory capitalism: explaining the ‘great convergence’

The ‘global diffusion of regulatory capitalism’ is commonly depicted across three now dominant explanatory frameworks. I characterise these as (1) policy transfer, (2) neo-liberalism and marketization, and (3) globalization. Each represents broad typologies that are by no means exclusive but are used as heuristic typologies to order an otherwise vast literature on the rise of regulatory systems of governance and attempts to explain institutional transplantation and convergence.

2.1 Policy transfer

One of the most dominant trends in recent policy literatures has been a focus on policy convergence (CitationBennett, 1991; Drezner, 2005), policy diffusion (CitationDobbin, Simmons, & Garrett, 2007; Elkins & Simmons, 2005; Gilardi, 2010), and policy networks (CitationBlanco, Lowndes, & Pratchett, 2011; Cao, 2012; Grossmann, 2013; King, 2010), all broadly referring to policy transfer — ‘a process in which knowledge about policies, administrative arrangements, institutions etc. in one time and/or place is used in the development of policies, administrative arrangements and institutions in another time and/or place’ (CitationDolowitz & Marsh, 1996, p. 344). This literature invokes two common explanations for policy transfer. First, a neo-functional sociological argument that sees the convergence of modern societies around similar systems of socio-economic organization as a fiat of the stages of economic growth and culminating in modernization, industrialization, urbanization and the transition toward post-industrial knowledge societies (see CitationBell, 1999; Galbraith, 1972; Rostow, 1971). These processes create analogous socio-economic, policy and administrative challenges: the requirements for efficiency and optimality (in terms of administrative organization, resource allocation, planning and economic growth), and institutional capacities (technocratic managerialism, oversight and accountability in the delivery of public goods and services) (CitationBennett, 1991, pp. 215–216). Convergence, in this sense, is functionally driven, since industrialization, modernization or urbanization in one place or time is more or less similar to those in other places and times, producing similar policy responses, administrative, governance and organizational outcomes (CitationStarke, Obinger, & Castles, 2008).

Related approaches also arise from organizational theory and Weberian conceptions of bureaucratization and rationalization in which bureaucracy as an organizational form produces increasing levels of organizational homogeneity in terms of ‘structure, culture, and output’ (CitationDiMaggio & Powell, 1983, p. 147). The functional attributes sustaining modernization, in other words, have a ‘levelling impact,’ where the logic of economism, the power of technology and the techno-scientific management of social and economic issues produce convergent tendencies in ‘social structures … and public policies’ (CitationAshley, 1983; Bennett, 1991, p. 216). As Levi-Faur notes, ‘regulatory capitalism is a technological as much as a political order’ and reflects as much the adoption of regulatory and institutional technologies (such as agentification) as it does a conscious embrace of a system of political organization Citation(2005, pp. 21–22).

A second, less functionalist stream of theorizing stresses policy transfer as diffusion, analytically de-coupling processes of diffusion from policy outcomes and thus any inference of functionality or determinism. Unlike convergence approaches, policy diffusion is not an ‘outcome but the flagship term for a large class of mechanisms and processes associated with a likely outcome’ (CitationElkins & Simmons, 2005, p. 36). Policy diffusion can thus be thought of as both cause and effect: ‘any pattern of successive adoptions of a policy’ (as quoted in CitationElkins & Simmons, 2005, pp. 36–38) but where the process of diffusion changes the probability of certain policies being adopted. As Stang and Soule note, ‘the adoption of a trait or practice in a population alters the probability of adoption for remaining non-adopters’ (as quoted in CitationElkins & Simmons, 2005, pp. 37–38) whether through processes of agenda setting, norm diffusion, or relational circumstances where a state moves to adopt a certain policy prompting other states to follow. Whatever the cause or mechanism of diffusion, the point is that diffusion is characterized as a reflexive process and assumes no destination or end point, prescriptive organizational form or policy design — it is, for the most part, happenstance and results from the series of individual decisions to adopt certain policies and practices for reasons specific to each policy actor but in a universe where the decisions of policy actors impact the subsequent choices and decisions of other policy actors — what Elkins and Simmons define as ‘uncoordinated interdependence’ Citation(2005, p. 38).

This non-functional, non-determinist approach to policy diffusion captures a now dominant theoretical approach in the policy transfer literature. Indeed, it has given rise to a cottage academic industry with scholars mapping and categorizing the multifarious mechanisms of diffusion. By one count, for example, upwards of ‘thirty distinct species of diffusion’ were identified, ranging from cascading norm diffusion (CitationCarroll & Jarvis, 2013; Jakobi, 2012) policy learning (CitationMeseguer, 2005; Meseguer & Gilardi, 2009), policy networks and knowledge communities, (CitationCao, 2010, 2012), relational and conditional diffusion processes associated with geography and space (CitationObinger, Schmitt, & Starke, 2013), to policy thresholds and tipping points (CitationVormedal, 2012) — among others. But as Shipan and Volden conclude, while over a 1,000 research articles addressing policy diffusion have appeared in the last 50 years, the ‘key findings and lessons’ remain opaque if not inconclusive’ Citation(2012, p. 788). Indeed, even the most elemental hypothesis of policy transfer through learning has produced a literature which Gilardi observes ‘has fallen short of providing compelling support for learning hypotheses’ Citation(2010, pp. 650–651). Rather, ‘[t]here is agreement that competition, learning, and social emulation are the main drivers of diffusion, but empirical evidence usually is ambiguous and unable to discriminate convincingly among these different explanations’ (CitationGilardi, 2010, p. 650).

The question thus remains: ‘policies diffuse, but why?’ (CitationGilardi, 2010, p. 650). More fundamentally, if the process of diffusion does not necessarily result in policy convergence but rather a tapestry of different policy, institutional and organizational outcomes, to what degree is the process of diffusion even significant? As Berger and Dore note, convergence might be more readily assumed than an encroaching reality Citation(1996). Rather than policy diffusion producing convergent outcomes, national variation in the political economy of organizational, policy and institutional forms continues to be an enduring reality, or what Hall and Soskice observed to be a kind of convergent diversity amid varieties of capitalism Citation(2001; see also CitationLevi-Faur, 2006).

2.2 Neo-liberalism and marketization

Another common explanatory framework attempting to delineate those forces causing convergence derives from critical political economy literatures. These identify changing capitalist modes of production and accumulation — specifically, the transformation from fordist to post-fordist (or flexible) regimes of accumulation — as instrumental drivers forcing states to respond in broadly ubiquitous policy terms to increased competition for capital (CitationHarvey, 1990). In the post-war era, for example, the Keynesian state enjoyed relative insularity from highly mobile capital by controlling market access through mercantilist trade and investment practices (protectionist measures that included tariffs, quotas, closed investment regimes, or capital account measures limiting convertibility and profit repatriation). In effect, this allowed the state to strike bargains or a social contract with labour and capital; orchestrating labour compliance and productivity increases to support returns on capital, commitments from capital on investment to support employment, innovation and economic growth, in exchange for state commitments for social protection arrangements, modest wealth and income redistribution through progressive taxation, and tax breaks on new investment (CitationHarvey, 2005; Majone, 1997).

In the last several decades, however, this model has been increasingly eroded. The emergence of new markets and the spread of capitalism (most notably in Asia and Latin America), the embedding of an increasingly globalized liberal trade regime facilitating capital mobility and transnational investment has transformed the international political economy, deepening interstate competition for capital, industry and jobs (CitationGrieco & Ikenberry, 2003; Ruggie, 1982).

States have thus been forced to respond in similar policy terms in order to attract capital, investment and sustain economic growth and employment. Policy measures including capital account liberalization to facilitate inward foreign investment and profit repatriation, liberalization of investment regimes including the cutting or eradication of tariffs, quotas and other non tariff barriers, combined with the emplacement of regulatory regimes to support private sector participation — including government guarantees and the establishment of independent regulatory agencies to reduce political risk to capital — have become standard policy norms promulgated unilaterally by states, bilaterally through trade and investment agreements, and multilaterally through regional economic unions (North American Free Trade Association, Association of Southeast Asian Nations, Latin American Free Trade Association, European Union) (CitationCammack, 2012; Carroll, 2014; Jarvis, 2012).

At the same time, as interstate competition for capital has intensified governments have engaged in competitive tax policies. Corporate tax rates have been reduced and taxes on profits rolled back in an attempt to encourage capital formation and new investment. The result, however, has been a reduction in the fiscal capacity of states, eroding the ability to sustain welfare expenditures or the direct provision of public goods, services and state ownership of industry and assets (CitationBeck, 1999; Harvey, 2005; Jarvis, 2007; Mishra, 1999, p. 9). Waves of privatization, the divestiture of state assets and deregulation — in which government monopolies (telecommunications, banking, public utilities, roads and transportation) have been systematically dismantled — have thus reconfigured the state and its reach, effectively dislodging it from control of the commanding heights of the economy (see CitationBrenner et al., 2010b; Peck, Theodore, & Brenner, 2012; Yergin & Stanislaw, 2002).

On another level, of course, this transformation has also been part of a larger political project associated with the global spread of neoliberalism — a project focused on dismantling the Keynesian state — indeed downsizing government generally. The adoption of ideological agendas that favour markets over government and the use of market mechanisms as preferred instruments in the delivery of public goods and services have radically altered the operation of government and government linked entities. This can be observed in what CitationHood et al. (1999) note as the emergence of ‘regulation inside of government,’ where the adoption of managerial practices relating to service levels, quality assurance and the audit of public expenditures is designed to align government with the practices of private organizations (CitationLodge & Wegrich, 2012, pp. 121–122). As Deem and Brehony observe:

[The] characteristics of ‘new managerialism’ in [public] organizations include: the erasure of bureaucratic rule-following procedures; emphasising the primacy of management above all other activities; monitoring employee performance (and encouraging self-monitoring too); the attainment of financial and other targets; devising means of publicly auditing quality of service delivery and the development of quasi-markets for services (CitationDeem & Brehony, 2005, p. 220).

This shift represents a transition from public administration to public management in which performance accountability is used to emplace metrics of valuation and promote the marketization of government activities; including, the development of performance indicators, benchmarking, rankings, and, most importantly, the use of ‘activity-based costing’ (ABC) accounting principles designed to assign to each activity a specific cost, identify the resource consumption of each actor or unit within an organization, and calculate the imputation of overheads (fixed costs such as infrastructure) to reflect the ‘true’ cost of service provision. Government activity is thus broken down into transactional inputs and outputs, costed in terms of ABC accounting principles and measured against performance metrics in order to assess ‘efficiency,’ ‘loss’ and ‘value-for-money’ in the production of government services. Most fundamentally of all, this allows the extension of precepts of efficiency and resource optimality through an econometric costing of government service delivery, including the opportunity costs of government providing certain services versus others or holding fixed assets (real-estate, a catering division, or a human resource office, for example) — effectively allowing comparisons about cost efficiencies between different service delivery models (contracting out, government service provision, privatization) (CitationDeem & Brehony, 2005, p. 220).

The ubiquity of the regulatory state and neo-liberalism thus reflect interlinked processes: the fiscal austerity of the post-fordist state in which government has been forced to be ‘leaner and meaner’ as it competes to better manage fiscal expenditures, reduce the tax burden on capital and remain internationally competitive as a destination for investment and production, and the ideological adoption of regulatory instruments designed to marketize previously co-opted government spaces, replacing systems of bureaucratic administration with institutional arrangements that enable their penetration by private capital and thus the creation of market-for-profit activity (CitationLeys, 2001). Convergence in policy is thus the outgrowth of enduring if not unstoppable global forces associated with the spread of capitalist relations of production.

2.3 Globalization and internationalization

A third typology extending the convergence thesis is situated around a body of literature that invokes globalization or internationalization. The notion that national borders, economies, if not cultures are ‘dissolving’ and becoming more porous is typically identified as a process of deepening interdependence. As a result of technological advances in communications and transportation technologies, most notably the advent of mass containerised shipping and air travel, interdependence across economic, political and social domains has deepened or as Roland Robertson notes has resulted in the ‘compression of the world and the intensification of the consciousness of the world as a whole’ (CitationRobertson, 1992, p. 2). For globalization theorists, these technological developments have permitted the obliteration of space and geography, enabling the disaggregation of production systems, the advent of global value chains and the emergence of global markets for items as diverse as food and horticultural products, to motor vehicles, air-conditioners, luxury goods, or medical and educational services. More obviously, with the ever increasing levels of human mobility, crossing borders to purchase goods and services changes fundamentally market thresholds and thus the ability of governments to manage national economic domains — perhaps even dissolving economic sovereignty. The notion of national market thresholds for Prada, Gucci, Glenfiddich, a university degree or a hip replacement, for globalization theorists is an historical anachronism and no longer captures the global domain in which music, cultural products, or countless other categories of economic activity now operate. Globalization thus represents a transformative zeitgeist that levels national diversity, producing increasing interdependencies that tend to be self-reinforcing (CitationHeld, 1999).

These theoretical approaches are not uncontested of course. Weiss insists that the ‘neoliberal state is a fiction,’ and that the state is not ‘out of business’ but still ‘occupied as ever in efforts to govern the market and influence economic outcomes’ Citation(2012, pp. 27–28). CitationHirst and Thompson (1999) add nuance to the globalization thesis, insisting that the spread of capitalist relations of production, deepening international trade and investment linkages and the explosive growth in multinational economic activity points to a particular international economic order imaged on US led liberalism but does not constitute hybridization or support convergent, integrationist theses championed by scholars such as Robertson (CitationDrezner, 2001; Hirst & Thompson, 1999, pp. 13–16). Still others reject the more exotic images of globalization as a convergent ‘global village’ or ‘one world’ but see important global trends associated with issue based interdependencies (cross border crime, global climate change, energy security, refugees, human rights, food security, student mobility, etc.) which foster the emergence of network or polycentric based governance modalities. As Stephen Ball notes, this is not a thesis about globalization and the ‘hollowing out of the state’ but ‘rather it is a new modality of state power, agency, and social action and indeed a new form of state’ (CitationBall, 2010, p. 14).

2.4 Coercive institutional isomorphism

These three epistemological frameworks each offer expansive explanations of the global diffusion of regulatory modalities of governance and the tendency toward policy and institutional convergence. Indeed, they represent a mass academic exercise that, over the last 30 years or so, has produced innovative, voluminous and now dominant epistemological traditions across the social sciences. But to what extent are these traditions operative within specific institutional contexts? How do these grammars reconfigure power and institutional politics in a way that facilitates policy transfer, institutional adaptation and transition? While, for example, the conduits or transmission mechanisms that transport ideas, values, economic forces and norms are readily identified almost absent in these grammars is any discussion of how these are instantiated into institutions, how vested interests are set aside and how localized institutional resistance is overcome? Indeed, these grammars mostly assume apolitical isomorphic processes premised on rational actor assumptions and perfectly aligned actor interests. Institutional and policy actors are assumed to be wholly responsive to international or external factors, receptive to change and harbour no vested interests in terms of current administrative and managerial practices or institutional preferences. Policy learning, emulation, the adoption of best practices, international benchmarks, and adaptation to external economic competition and ideational perspectives are all assumed to cascade down and automatically morph into localized institutional contexts and become operative norms.

Such assumptions, of course, are highly problematic. They negate the politics of institutional isomorphism. As DiMaggio and Powell observe, such a view ‘does not present a fully adequate picture of the modern world of organizations.’ Organizations do not exist in apolitical contexts; they ‘compete not just for resources and customers, but for political power and institutional legitimacy, for social as well as economic fitness.’ Institutional isomorphism, in other words, is only useful as an analytical concept if it captures the ‘politics and ceremony that pervade much modern organizational life’ Citation(1983, p. 150).

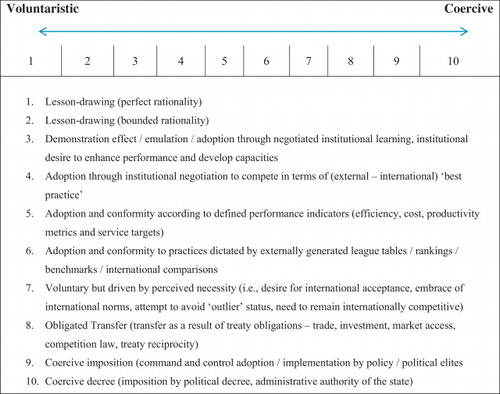

Institutional isomorphism might thus be better conceptualized on a voluntaristic — coercive continuum (see Fig. 1 ), where coercive isomorphism reflects both the ‘formal and informal pressures exerted on organizations by other organizations upon which they are dependent’ (CitationDiMaggio & Powell, 1983, p. 150). These pressures can assume various forms; force, persuasion, consultation, signalling, co-option of policy elites and organization leaders, resource allocation, organization intervention and restructuring, resource incentives, or government mandate and the legal exercise of administrative state power. Policy transfer, learning and any resultant isomorphism has thus to be appreciated in the context of institutions operating as places of vested interests, as sites of politics and contestation, and where organizational interests and intra-organizational competition for resources and power play a fundamental role in mediating the processes and outcomes of isomorphism.

Source: Adapted from CitationDolowitz and Marsh (2000).

In the following section I reflect on these frameworks and their utility in the case of isomorphic processes associated with the emergence and operation of the regime for quality assurance in the Hong Kong higher education sector and the implications for regulatory performativity.

3 Explaining the emergence of a regulatory regime for quality assurance in the higher education sector in Hong Kong

Over the last 25 years the emergence and spread of quality assurance (QA) regulatory regimes in higher education has been explosive. Led most notably by developments in the United Kingdom with the publication of the 1991 White Paper, Higher Education: A New Framework which brought tertiary institutions under a single regulatory framework, quality assurance regimes have subsequently emerged in numerous justifications (Portugal, Germany, Poland, Spain, France, the UAE, Australia, New Zealand, Romania, Denmark, Sweden, Norway — among others) and been promulgated in regional bodies such as the European Union (see CitationCapano, 2014; Gornitzka & Stensaker, 2014). By one estimate, for example, nearly half the countries in the world now have quality assurance systems or QA regulatory bodies for higher education (CitationMartin, 2007).

The explosive growth in QA regulatory regimes is typically explained in relation to the epistemological frameworks outlined previously. Specifically, changing fiscal capacities among states have witnessed reduced funding for the sector, forcing sector participants to diversify their revenue streams, move to user pay models and adopt institutional practices focused on revenue and cost management (CitationFrank, Kurth, & Mironowicz, 2012). Marketization is thus most often invoked as a rationale for introducing QA regimes as governments seek to balance service quality in the face of institutional competition for fee paying students and concerns about deteriorating entry standards, student-teacher ratios, grade inflation and the rise of ‘degree factories’ (CitationDouglass, 2012; Levy, 2010, 2012).

Similarly, the shift to flexible regimes of economic activity requiring the cultivation of mass higher order skills to sustain growth in knowledge based economies, has prompted rapid expansion of the sector requiring governments to focus on the management of quality amid ‘massification’ (CitationBall, 2010). Other common explanations note the global trend toward liberalization and the entry of private operators into the sector, effectively lowing entry barriers and requiring governments to set in place mechanisms for institutional accreditation, licensing and the assurance of operator standards. Heightened student mobility, the emergence of a ‘global market for higher education’ and interstate competition to attract students are also commonly identified as reasons for the adoption of QA regimes, in part to benchmark against other competitor states and in part to protect the reputational standing of the domestic sector.

The emergence of QA regimes is thus commonly explained as a by-product of these concerns as government and sector participants attempt to demonstrate quality and standards as a means of protecting the industry, securing institutional reputations, and validating the worth of for fee programmes to ensure student demand and sustainability of the sector in the face of increasing student mobility and global competition. In a sense, as Lewis and Smith note, the emergence of QA regimes might be understood in the context of three political moments: ‘… the fact is that (1) the environment for higher education is changing and (2) competition for both students and funds will continue to increase, at a time when (3) we are going to have to accomplish more with less’ (CitationLewis & Smith, 1994, p. x). The politics of fiscal austerity, in other words, provide both the ideational rationale forcing the adoption of QA regimes and the managerial response in terms of new governance in the sector (competition and liberalization).

3.1 Repositioning higher education in Hong Kong

In the Hong Kong context, these explanatory narratives perhaps fail to capture the causalities and mechanisms responsible for institutional isomorphism. Marketization, competition, fiscal austerity, the globalization of higher education, or a ‘downsizing’ of the state have historically been alien concepts in the Hong Kong higher education sector. For much of its history, the sector has been privileged, elite and niche, amply funded and insulated from international trends and competition.Footnote1 In the 1970s, for example, only 2% of a graduating high school cohort gained entrance to higher education with the government restricting growth in the sector to 3% per annum (CitationMok, 2000, p. 156). Indeed, as late at 1990 less than 9% of high school graduates were admitted to university in Hong Kong, with the government (through the CitationUniversity Grants Commission — UGC) tightly controlling university places (CitationTam, 1999, p. 217). Any notion of ‘massification’ would thus misrepresent the Hong Kong higher education context, which even today admits only 20% of a graduating cohort into a UGC funded university place — one of the lowest in the developed world (CitationUGC, 2013).Footnote2 Indeed, the supply of available (funded) places is vastly outpaced by demand, which in 2013 saw 13,000 students meet admission requirements but miss out on a university place (CitationJarvis, 2014).

Historically, an elite and highly truncated university system reflected the structure of Hong Kong's economy that rested overwhelming on small and medium sized trading businesses, low value-adding manufacturing, marine services, logistics and financial services (CitationJarvis, 2011). It also reflected the sentiment of a colonial administration committed to Laissez-faire, with minimal government involvement in the economy or welfare arrangements. Further, a generally affluent middle class typically schooled their children offshore, reflecting the status associated with a British or Western university education. In the late 1980s, for example, there were as many students studying overseas (35,000) as were enrolled in Hong Kong higher education institutions (CitationShiev, 1992).

By the late 1980s a series of factors prompted a re-examination of the policy stance of government toward the higher education sector. Two dominant issues confronted the Hong Kong government. First, liberalization in mainland China with Deng Xiaoping's 1979 reform policy of ‘opening up’ and which established a special economic zone (SEZ) immediately to the north of Hong Kong, radically transformed Hong Kong's economy. Hong Kong's textile and footwear industry, low and medium value manufacturing and the legion of enterprises that operated to support these, moved north to Shenzhen, essentially wiping out the manufacturing sector in Hong Kong and a large swath of employment opportunities.Footnote3 Second, the impending handover of Hong Kong back to China (1997) represented enormous challenges across a wide spectrum of issues ranging from economic integration, political administration and governance, issues of autonomy, self-determination, freedom of expression, and more broadly how to position Hong Kong economically in order to retain its utility to China and its competitive position internationally. By the late 1980s, these challenges were manifesting in a broader economic policy of repositioning Hong Kong as both the world's window into China and China's window to the world and as a regional hub for professional services — an enduring macro-policy theme that continues to this day (see CitationMok & Cheung, 2011).

In 1989 the government announced the first of several subsequent measures to re-position Hong Kong and respond to the structural changes within its economy.Footnote4 One of these included expansion of higher education with a target of dramatically increasing the cohort of 17–20 year olds who enter university from an average of 6% in the 1980s to 18% in the1990s (CitationUGC, 1993, 1996b, Appendix L). Massive resource increases were thus anticipated as the Hong Kong government attempted to transition the economy into services and knowledge based activities, enhance the skill set of the workforce and stem the tide of skill drain — as many young Hong Kong graduates began emigrating due to the political uncertainties of the impending handover (CitationMok, 2000, p. 156; Citation2005; Tam, 1999, p. 217). Resource allocations, in particular, increased dramatically, with expenditure on the sector hitting HKD$14 billion in 1996, or about 35% of the entire budget spend on education, in part reflecting the establishment of several new universities (CitationTam, 1999, p. 221; CitationUGC, 1996a).Footnote5

Today, after nearly 25 years of investment the sector has expanded to 8 publically funded higher education institutions supporting 95,000 students, a full time professoriate of 4,719, admitting 17,000 first year students and 3,300 senior year entry students annually (via sub-degree programmes) (CitationUGC, 2013).Footnote6 While by international standards the size of the sector remains small and the percentage of graduating high school students admitted to a UGC funded university place lags behind comparable high income economies, the transformation of the higher education landscape from an elite to more broadly based university sector has been both rapid and impressive.

3.2 Governance of the Hong Kong higher education sector: innovation, intervention and coercion

In line with the expansion of higher education, the institutional and oversight structures responsible for governance of the sector have also evolved but in a manner that has tended to reinforce existing institutional powers. Historically, for example, the University Grants Committee (established in 1965) has been the primary institution responsible for advising on funding and the academic development of higher education in Hong Kong. Indeed, its role has been all-powerful, both in terms of expenditure recommendations to the Chief Executive but also in terms of quality assurance and planning for the sector, sector composition, institutional specialization and focus, determination of the number of UGC funded student places, allocation of postgraduate student places, setting quotas for self-funded places, grants for capital works programmes, along with a broad sweep of other roles that impact the activities and practices of universities in Hong Kong. While universities operate as ‘autonomous entities,’ in reality they are accountable to the UGC, report directly to the UGC, and are periodically reviewed by the UGC.Footnote7 These reviews include ‘management reviews (MR), teaching and learning quality process reviews’ (TLQPRs), and various ‘peer reviews’ as well as the UGC ‘providing incentives to institutions with a view to ensuring and enhancing teaching and learning quality, as well as students’ language proficiency’ (CitationUGC).

While this institutional legacy remains, since the late 1980s governance and oversight in the sector has become progressively more intrusive. Institutions and mechanisms associated with quality assurance, for example, have evolved from a reliance on the Council for National Academic Awards (CNAA) in the United Kingdom, which was periodically engaged by the UGC to advise on the academic quality of degree programmes, to the establishment of the Hong Kong Council for Academic Accreditation (HKCAA) in 1990 (subsequently the Hong Kong Council for Accreditation of Academic and Vocational Qualifications [CitationHKCAAVQ] in 2007) (CitationUGC, 2010, pp. 112–113.). An independent statutory body, the HKCAAVQ provides advice on academic standards of degree programmes in higher education institutions in Hong Kong, quality assurance and assessment services and has statutory authority as the accreditation agency of higher education institutions (HKCAAVQ).

Other oversight bodies were also created, including the Joint Quality Review Committee (CitationJQRC), an independent corporate quality assurance committee established in August 2006 by the Heads of Universities Committee of the eight UGC funded higher education institutions. Operating under the aegis of the UGC, JQRC's primary function is to ‘provide for the peer review of the quality assurance processes of the self-financed sub-degree programmes’ operated by UGC funded institutions (JQRC). Further, the establishment of the Quality Assurance Council (again under the auspices of the UGC) in 2007, ‘to advise the UGC on quality assurance matters in the higher education sector in Hong Kong,’ was charged with undertaking periodic ‘quality audits of UGC funded institutions’ (CitationQAC, n.d., pp. 4–5), providing a formal body within the UGC responsible exclusively for quality assurance and enhancement. These developments were also coupled with the implementation in 2008 of a ‘Qualifications Framework’ (QF) designed to ‘define clearly the standards of different qualifications, ensure their quality and indicate the articulation ladders between different levels of qualifications.’ The idea behind the establishment of a Hong Kong wide QF was to facilitate the emergence of an equivalence principle, whereby programmes of study, modules and the academic skills attained would be broadly commensurate across institutions, facilitating student mobility by ‘helping individuals to pursue their own goals according to their own roadmaps’ (CitationUGC, 2010, pp. 116–117).

Complementing the introduction of a QF was the announcement of the Credit Accumulation and Transfer System (CATS), the technical apparatus designed to facilitate cross programme/institutional student mobility by standardising the metrics for the accumulation of academic/programme credit and thus facilitating credit transfer through institutional reciprocity — although this has failed to become fully operational (CitationUGC, 2010, p. 117).Footnote8 This was complemented with the launch in May 2008 of the CitationQualifications Register (QR) maintained by the HKCAAVQ. The QR contains a register of quality assured qualifications, programmes and their operators, providing transparent information to the public in order to enhance consumer knowledge (QR).

Finally, in addition to these bodies and activities the UGC has also launched research quality assurance initiatives, commencing in 1991 with the establishment of the CitationResearch Grants Council (RGC), which oversees the operation of competitive grants schemes and serves as an advisory body to government (under the aegis of the UGC) on matters relating to ‘academic research, including the identification of priority areas’ and research quality (RGC). Similarly, the implementation by the UGC of a periodic research assessment exercise (RAE) commencing in 1993, and repeated in 1996, 1999 and 2014 is designed to measure the research output and quality of all UGC funded institutions, allowing for comparison and the allocation of supplementary funds (CitationMok, 2005, p. 285).

3.3 State-led coercive institutional isomorphism

Since the commencement of reform and expansion of the higher education sector in 1989, governance trends in the sector have been increasingly (and deliberately) intrusive. As Mok and Cheung note, ‘the UGC has introduced various forms of internal and external reviews on teaching, research and governance, using instruments and criteria most often borrowed from the West’ in terms of RAEs, TLGPRs, disclosure and reporting practices, accountability mechanisms and performance based metrics to help institutions and the UGC asses performance and outcomes across a spate of areas (CitationMok & Cheung, 2011, p. 234). As Mok and Chueng further note, these mechanisms have been ‘imposed’ through command and control policy instruments announced by the UGC and aligned with government policy to ‘internationalize’ the university sector. They reflect attempts by the UGC to ‘induce (or coerce) higher education institutions to become more globally competitive,’ often using quality assurance as a umbrella policy that requires higher education institutions to adopt managerial practices, research and teaching benchmarks aligned with performance metrics broadly reflecting international norms favoured by the UGC (CitationMok & Cheung, 2011, p. 234).

A dominant feature in the evolution of the sector has thus been the increasing degree of centralization as opposed to liberalization, corporatization or the devolution of budget sustainability and management to higher education institutions themselves — as has been the trend in places such as the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States. Rather, reform efforts in the sector have concentrated institutional and administrative authority, consolidating the position of the UGC and enabling it to more forcefully set the rules, agendas and performance modalities that govern the sector. Of course, the UGC has no formal authority over sector participants. As the UGC itself notes, it has ‘neither statutory nor executive powers’ and operates in an environment where higher education institutions are autonomous, each with their own ordinance and governing council, and ‘have substantial freedom in the control of curricula and academic standards, the selection of staff and students, initiation and acceptance of research, and the internal allocation of resources’ (UGC). Rather, the UGC's authority is relational and derives from two continuing factors.

First, unlike international counterparts, Hong Kong's higher education sector continues to be predominately state funded through the allocation of UGC funded places to each institution, the provision of block grants and capital works grants, along with a series of other grants for knowledge transfer activities, travel and enrichment grants for students, teaching enhancement grants and state funding (through the RGC) for research. While there has been marketization in the sector, this has been confined to a ‘side business’ model in universities, with UGC institutions supplementing their income through fee paying sub-degree programmes and coursework masters programmes — but even here with the UGC stipulating the number of places in sub-degree and masters programmes.Footnote9 Higher education institutions in Hong Kong thus remain overwhelmingly reliant on state funding managed via the UGC, fostering a dependent relationship. Further, despite the emergence of private universities in Hong Kong, these too are subject to control, constitute a relatively minor sector compared to the eight UGC funded higher education institutions, and offer no reputational or price competition to established operators. As a result, the governance monopoly the UGC enjoys has been entrenched, allowing it to agenda set, incentivize and allocate resources in ways that steer the sector.

Second, the UGC has been able to secure increasing levels of institutional compliance through the introduction of various managerial instruments that adopt the precepts of merit based competition (competitive based research grant allocations, supplementary grants based on RAE performance) and neo-liberal managerial practices (performance based indicators and outcomes driven metrics), and the adoption of ‘regulation inside of government’ regimes with institutions having to demonstrate value for money and efficiency in service delivery in the expenditure of public finances. Large scale performative exercises that focus on institutional audits (conducted by the QAC), research audits (RAEs conducted by the UGC) and teaching and learning quality process review audits (conducted by the UGC), as well as financial reporting (to the UGC), act as powerful devices that define incentives and performance metrics, steer the allocation of institutional resources, and reframe institutional preferences in terms of research, hiring practices, programme offerings and teaching. Indeed, aligning financial resources with audit outcomes, as with the RAE, for example, operates as an especially powerful signalling device that changes institutional and individual behaviours.

The language and practices of neo-liberalism, audit cultures and the emplacement of regulatory regimes to assure quality, in Hong Kong have thus been used as an instrument to enhance oversight and steer the higher education sector. The UGC itself tacitly acknowledges its role in this process, noting:

The UGC … takes a proactive role in strategic planning and policy development to advise and steer the higher education sector in satisfying the diverse needs of stakeholders. To fulfil this role, the UGC ensures that at system level, appropriate tools, mechanisms and incentives are in places to assist institutions to perform at an internationally competitive level in their respective roles (UGC).

Epistemological frameworks that explain the adoption of neo-liberal managerial cultures as an outcome of globalization, marketization, or an ideological embrace of the market, in the Hong Kong context fail to understand recent institutional developments and how quality assurance regimes have been used as part of a broader policy framework by the state to promote and build the sector and position Hong Kong internationally. As Mok and Cheung note, the education industry has assumed new importance in Hong Kong and been identified as ‘one of the six new economic pillars that will help diversify’ Hong Kong's economy — which, historically, has been dominated by financial services Citation(2011, p. 232). Far from liberalization of the sector the state has in fact taken a much more interventionist, lead role, aligning higher education with key state-led development strategies designed to leverage off increasing local and regional demand for graduates with higher order skill-sets.

Equally, policy transfer literatures or notions of convergence around largely similar institutional forms or policy frameworks, also fail to capture developments in Hong Kong which are atypical in comparison to international trends. Indeed, to the extent that the notion of policy transfer captures the utilization of specific policy instruments (performance based indicators, audits and reporting cultures, quality assurance regimes, accountability and transparency norms), the policy ends to which these have been applied speak to a greater, more intensive and intrusive role of the state in the sector as opposed to a reconfiguration of the relationship between the state and higher education institutions in Hong Kong. In his analysis of the impact of new public management (NPM) agendas on Asian countries, for example, Cheung made a telling observation:

‘Administrative reforms in Asian countries … seek to empower rather than denigrate the bureaucracy. NPM-like reforms have been adopted not to erode bureaucratic power, but instead to cement or reinvent it as a modernizing and developmental bureaucracy, so as to enhance the state's capacity in economic development…’ Citation(2011, p. 134).

While public sector reform in the West has been a process of ‘repositioning public governance’ which has impacted the role, scope and functions of the state, ‘in Hong Kong there has been, on the reverse, a steady shift towards a pro-state regime, in contrast to the laissez-faire state in the heyday of colonial rule’ (CitationCheung, 2010, p. 79). Cheung describes this as an outgrowth of post-colonial sentiment fuelling rising expectations and demands for greater government involvement in social and economic development, a ‘population eager to find a new sense of identity and future for the SAR,’ and a government grappling with structural transitions in the economy and otherwise forced to take a more interventionist role. As Cheung concludes:

Caught at a cross roads of transition, between legacies of small government and non-interventionism on the one hand, and new exogenous and endogenous needs for expansion and interventions on the other, the government faces the paradox of having both to reassert the ‘public’ and the role of the state in economic and social management, and to emphasize the use of more market-orientated means to achieve its public goals Citation(2010, pp. 79–80).

4 Regulatory performativity, sector outcomes and policy convergence

Cheung's observations suggest a more complex set of policy dynamics at play in the Hong Kong higher education context than might first appear to be the case. It explains atypical policy characteristics associated with increasing centralization, intrusive and assertive oversight and ‘steering’ practices existing side-by-side attempts to emplace greater competition, managerial and accountability practices typically associated with governance innovations that devolve power to operators and independent regulatory agencies.

The track record of this ‘soft developmentalism’ in which the state has attempted to use coercive regulatory means to elicit desired sector outcomes is mixed however. Indeed, the politics of regulatory coercion otherwise designed to reposition the sector in line with the economic vision articulated by the Hong Kong government, imposes costs and induces behaviours often at odds with this goal. The bureaucratic encroachment into the operating environments of higher education institutions, for example, where reporting, disclosure and accountability mechanisms reach into virtually every academic and managerial activity (teaching plans for each cohort of the student population, reporting on learning outcomes at the programme level, activities statements by academic staff, annual reflective exercises listing innovations or changes to modules, programmes and teaching practices, teaching and research performance outcomes, and ongoing reporting of metrics attainment against a vast set of performance indicators and benchmarks — among others), download enormous compliance costs both to the institution and individual. To what extent this represents best international practice, or contributes to an environment conducive to academic excellence and building innovative, creative, dynamic and self-sustaining institutions, is as yet unproven, however. Indeed, there is evidence to suggest that it may well be counterproductive. Comparative studies by CitationCoates, Dobson, Goedegebuure, and Meek (2010), for example, exploring negative attitudes toward university management and the perceived impact on academic labour practices showed Hong Kong ranked second worst only behind the United Kingdom out of 18 countries (see also CitationFredman & Doughney, 2012; Teelken, 2012).

Similarly, coercive regulatory practices administrated through recurrent programme audits and external assessments, quality assurance audits, as well as on-going institutional reviews, keeps sector participants in a constant state of metric/assessment fetishism. The result is a tendency toward compliance in terms of data collection and reporting but where the regulatory impact on behaviours and sector outcomes is less clear. Indeed, institutions and individuals in the sector often display what CitationBraithwaite (2008, pp. 140–152) defines as ‘regulatory ritualism:’ reports are produced, assessments performed, performance indicators reported, but in a manner that is disconnected from the culture, practices and the behaviours of individuals and institutions. Performance as presentation, in other words, becomes an internalized institutional priority, with institutions devoting considerable resources to preparations for review and audit, including mock ‘dress rehearsals,’ coaching staff on presentation styles and statements, screening academics and students to meet with auditors, as well as the preparation of documentation to meet audit and annual reporting requirements.

The regulatory efficiency of such practices in terms of steering the sector toward key goals associated with internationalization, league table performance, research impact and, penultimately, the sector contributing to Hong Kong's economy as a ‘regional education hub,’ is yet to be demonstrated. After two decades of reform efforts, for example, the sector remains insulated; still predominately state funded and displays a low level of internationalization, while the most recent league tables indicate Hong Kong universities all falling in the rankings (UGC; CitationZhao, 2014). While it would be incorrect to ascribe these outcomes exclusively to a specific mode of regulation, clearly sector performance is a reflection of the quality of governance. But here to, the sector displays an inefficient regulatory design. The proliferation of regulatory organs (QAC, JQRC) under the UGC in addition to the activities performed by the UGC itself, have created multiple bodies engaged in quality assurance, multiplied compliance requirements, and introduced obstacles to the effective coordination of regulatory activities. Further, the quality assurance regime has been bifurcated between the UGC, QAC and JQRC on the one hand, and the HKCAAVQ on the other, with the qualifications framework, the framework metric for academic standards, operated under the purview of the HKCAAVQ — not the UGC. In the most recent review of the sector by the UGC, for example, these regulatory anomalies were surfaced as a potential impediment to quality assurance and regulatory effectiveness in the sector:

The current division of responsibilities among the various quality assurance bodies is largely the result of evolution. In the past decade, the rapid expansion of the post-secondary education sector in terms of size and diversity called for new initiatives, and new quality assurance bodies were established to address new concerns. While these initiatives served Hong Kong well in the past, it is now appropriate to re-think whether a unified quality assurance body for the entire post-secondary sector would make it easier to develop a clear and coherent framework for quality assurance and enhancement, and give the Qualifications Framework a more coherent background (CitationUGC, 2010, p. 114).Footnote10

5 Conclusion

The analysis in this paper points to the need to reconsider the dominant epistemological frameworks used to explain what has otherwise been characterised as the ‘global diffusion of regulatory capitalism’ (CitationLevi-Faur, 2005). These have suggested largely ubiquitous processes, and political and economic logics, that are broadly impacting governments around the world equally — and conspiring to produce similar policy responses, public sector reform efforts and similar state-market re-configurations. Clearly, however, the explanatory power of policy transfer literatures, notions of neo-liberalism, marketization or globalization are challenged in the case of Hong Kong — and one suspects in a greater part of developing Asia too. As Linda Weiss notes, this alludes to a paradox in the way theorists have polarized images of the ‘developmental’ and ‘neo-liberal’ state as antithetical entities when, in fact, they may exist coextensively, with the state utilizing marketization strategies or neo-liberal managerialism as part of a state dominated tool kit to coerce and shape reform and manage economic development (CitationWeiss, 2012). Further, it also highlights the continuing salience of CitationDiMaggio and Powell's (1983) typology of coercive institutional isomorphism, theorists who long ago recognized the importance of political context, administrative authority and institutional power in shaping and defining pathways of change and inducing organizational compliance.

But while DiMaggio and Powell's typology remains an important, if not seminal, contribution to understanding institutional isomorphism, it fails to theorise the relationship between pathways of change and the efficiency or effectiveness of outcomes. As the case study presented in this paper demonstrates, coercive state-led developmentalism is not always destined to success and can sometimes generate forms of regulatory or even organizational performativity that ‘comply’ without meaningful compliance. As ever, the specific nature of institutional engagement with authority and the manifestation of this in terms of sector outcomes makes for a much more complex set of dynamics than a simple reading of Hong Kong's political economy as a site of ‘soft’ state-led developmentalism would suggest.

Notes

* The author would like to thank Billy Wong and Willis Yim of the Hong Kong Institute of Education for their research assistance in the preparation of this article.

1 Similar observations have also been made in the context of Singapore, a city-state often compared to Hong Kong given the similarity in size, history and their competitive rivalry (see, for example, CitationYat Wai Lo, 2014).

2 This shortfall in supply, of course, reflects university admission and funding policy and not demand. For most of its recent past, Hong Kong has been one of the main suppliers of fee paying students seeking university admission in the United Kingdom. In 2011–2012, for example, 11,335 Hong Kong students enrolled in British Universities, with Hong Kong ranking 6th among non-EU economies as a source of students — after mainland China, India, Nigeria, the US and Malaysia, all of which have considerably larger populations. Add in enrolments in Australian, Canadian, the US and European universities and Hong Kong exports a large proportion of its high school cohort overseas due to the lack of placement options in local universities (CitationJarvis, 2014).

3 As a rough proxy of the scale of this transformation, it is worth noting the rapid population gains in Shenzhen as industry, manufacturing and related sectors moved across the border from Hong Kong, accelerating Shenzhen's position as a powerhouse in China's export driven growth. When the Special Economic Zone was announced in December, 1979, Shenzhen's population stood at a mere 314,000. By the end of the 1980s, the population had more than tripped, tipping 1.2 million, reaching 4.5 million in 1995, 7 million in 2000, and 10.4 million by 2011. Source: Shenzhen Municipal Statistic Bureau. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

4 The announcement was prompted by the findings and recommendations of the Education Commission's Report No. 3 (ECR 3) (see CitationUGC, 1993, Higher Education After 1995 (Chapter 4).

5 The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) was established in 1991, City University of Hong Kong, the Hong Kong Polytechnic University and the Hong Kong Baptist University were all conferred university title in 1994, followed by Lingnan University in 1999 (CitationUGC, 2013).

6 The 8 publically (UGC) funded higher education institutions are: City University of Hong Kong; Hong Kong Baptist University; Lingnan University; The Hong Kong Polytechnic University; The Chinese University of Hong Kong; The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, The Hong Kong Institute of Education; the University of Hong Kong.

7 The University Grants Committee (UGC) is appointed by the Chief Executive of Hong Kong as opposed to the Secretary of Education, Education Bureau. It is a non-statutory body and thus enjoys considerable independence from the government of Hong Kong, Special Administrative Region, China (UGC).

8 It is worth noting that the CAT system, despite its introduction in 2008, has been only partially implemented, in part due to the potential of UGC money following students as they traverse between institutions. Higher education institutions have clearly feared this possibility and the financial losses that could ensue, and have sought to discourage cross institutional student mobility through creating programme requirements that limit student options (CitationUGC, 2010, pp. 116–117; 120–122).

9 The UGC has been able to control the extent to which UGC funded higher education institutions offer fee paying programmes by requiring them to report, and avoid, what is termed ‘cross-subsidisation;’ that is, in terms of ABC accounting principles the UGC require that the use of UGC provided facilities (buildings, labs, teaching rooms, lecture halls, libraries and student facilities) be costed into the fee structure of ‘self-funded’ programmes so that public monies are not used to subsidize fee based programmes. The UGC has also used quotas to limit the ratio of self-funded students relative to UGC funded students within UGC funded institutions. Enterprising higher education institutions (including the University of Hong Kong and the Hong Kong Institute of Education — among others), however, have sort to side step this restriction by acquiring their own off campus teaching facilities. For example, the University of Hong Kong operates its ‘Space’ campus while the Hong Kong Institute of Education operates the ‘Tseung Kwan O’ off campus study centre.

10 Similar sentiments were expressed in interviews conducted with officials in the HKCAAVQ.

References

- R.K. Ashley . Three modes of economism. International Studies Quarterly. 27 1983; 463–496.

- S.J. Ball . Global education, heterarchies, and hybrid organizations. K.H. Mok . The search for new governance in higher education in Asia. 2010; Palgrave Macmillan: New York 13–28.

- U. Beck . World risk society. 1999; Polity Press: Malden, MA

- D. Bell . The coming of post-industrial society: A venture in social forecasting. 1999; Basic Books: New York

- C.J. Bennett . What is policy convergence and what causes it?. British Journal of Political Science. 21(2): 1991; 215–233.

- S. Berger , R.P. Dore . National diversity and global capitalism. 1996; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, New York

- J. Black . Proceduralizing regulation: Part I. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies. 2000; 597.

- J. Black . The decentred regulatory state?. 2007; Centre for the Study of Regulated Industries, The University of Bath: United Kingdom

- J. Black . Constructing and contesting legitimacy and accountability in polycentric regulatory regimes. Regulation and Governance. 2 2008; 137–164.

- I. Blanco , V. Lowndes , L. Pratchett . Policy networks and governance networks: Towards greater conceptual clarity. Political Studies Review. 9 2011; 297–308.

- J. Braithwait . Regulatory capitalism: How it works, ideas for making it work better. 2008; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK

- N. Brenner , J. Peck , N. Theodore . After neoliberalization?. Globalizations. 7 2010; 327–345.

- N. Brenner , J. Peck , N. Theodore . Variegated neoliberalization: Geographies, modalities, pathways. Global Networks. 10 2010; 182–222.

- P. Cammack . Risk, social protection and the world market. Journal of Contemporary Asia. 42 2012; 359–377.

- X. Cao . Networks as channels of policy diffusion: Explaining worldwide changes in capital taxation, 1998–2006. International Studies Quarterly. 54 2010; 823–854.

- X. Cao . Global networks and domestic policy convergence: A network explanation of policy changes. World Politics. 64 2012; 375–425.

- G. Capano . The re-regulation of the Italian university system through quality assurance: A mechanistic perspective. Policy and Society. 33(3): 2014; 199–213.

- T. Carroll . ‘Access to Finance’ and the death of development in the Asia-Pacific. Journal of Contemporary Asia. 2014 10.1080/00472336.2014.907927.

- T. Carroll , D.S.L. Jarvis . Market building in Asia: Standards setting, policy diffusion, and the globalization of market norms. Journal of Asian Public Policy. 6 2013; 117–128.

- A.B.L. Cheung . Repoisitioning the State and the public sector reform agenda: The case of Hong Kong. M. Ramesh , E. Araral Jr. , X. Wu . Reasserting the public in public services: New public management reforms. 2010; Routledge: Oxon, England/New York, USA 79–100.

- A.B.L. Cheung . NPM in Asian countries. T. Christensen , P. Laegreid . The Ashgate companion to new public management. 2011; Ashgate: Surrey, England/Burlington, VT, USA 131–146.

- H. Coates , I.R. Dobson , L. Goedegebuure , L. Meek . Across the great divide: What do Australian academics think of university leadership? Advice from the CAP survey. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management. 32 2010; 379–387.

- R. Deem , K.J. Brehony . Management as ideology: The case of ‘new managerialism’ in higher education. Oxford Review of Education. 31 2005; 217–235.

- P.J. DiMaggio , W.W. Powell . The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review. 48 1983; 147–160.

- F. Dobbin , B. Simmons , G. Garrett . The global diffusion of public policies: Social construction, coercion, competition, or learning?. Annual Review of Sociology. 33 2007; 449–472.

- D. Dolowitz , D. Marsh . Who learns what from whom: A review of the policy transfer literature. Political Studies. 44 1996; 343–357.

- D.P. Dolowitz , D. Marsh . Learning from abroad: The role of policy transfer in contemporary policy making. Governance. 13(1): 2000; 5–23.

- J.A. Douglass . The rise of the for-profit sector in US higher education and the Brazilian effect. European Journal of Education. 47 2012; 242–259.

- D. Drezner . Globalization and policy convergence. International Studies Review. 3 2001; 53–78.

- D. Drezner . Globalization, harmonization, and competition: The different pathways to policy convergence. Journal of European Public Policy. 12 2005; 841–859.

- Z. Elkins , B. Simmons . On waves, clusters, and diffusion: A conceptual framework. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 598 2005; 33–51.

- A. Frank , D. Kurth , I. Mironowicz . Accreditation and quality assurance for professional degree programmes: Comparing approaches in three European countries. Quality in Higher Education. 18 2012; 75–95.

- N. Fredman , J. Doughney . Academic dissatisfaction, managerial change and neo-liberalism. Higher Education. 64 2012; 41–58.

- J.K. Galbraith . The new industrial state. 2nd ed., 1972; Deutsch: London

- F. Gilardi . Who learns from what in policy diffusion processes?. American Journal of Political Science. 54 2010; 650–666.

- Å. Gornitzka , B. Stensaker . The dynamics of European regulatory regimes in higher education — Challenged prerogatives and evolutionary change. Policy and Society. 33(3): 2014; 177–188.

- J.M. Grieco , G.J. Ikenberry . State power and world markets: The international political economy. 2003; W. W. Norton: New York, London

- M. Grossmann . The variable politics of the policy process: Issue-area differences and comparative networks. Journal of Politics. 75 2013; 65–79.

- P.A. Hall , D. Soskice . Varieties of capitalism: The institutional foundations of comparative advantage. 2001; Oxford University Press: Oxford

- D. Harvey . The condition of postmodernity: An enquiry into the origins of cultural change. 1990; Blackwell: Oxford, England/Cambridge, MA

- D. Harvey . A brief history of neoliberalism. 2005; Oxford University Press: Oxford/New York

- D. Held . Global transformations: Politics, economics and culture. 1999; Polity Press: Oxford

- P.Q. Hirst , G. Thompson . Globalization in question: The international economy and the possibilities of governance. 2nd ed., 1999; Polity Press: Cambridge

- HKCAAVQ. Hong Kong Council for Accreditation of Acadmeic & Vocational Qualifications. URL http://www.hkcaavq.edu.hk/en/about-us/about-hkcaavq Accessed 15.05.14..

- C. Hood . Controlling modern government: Variety, commonality and change. 2004; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham

- C. Hood , O. James , G. Jones , C. Scott , T. Travers . Regulation inside government: Waste-watchers, quality police, and sleazebusters. 1999; Oxford University Press: Oxford

- C. Hood , C. Scott . Bureaucratic regulation and new public management in the United Kingdom: Mirror-image developments?. Journal of Law and Society. 23 1996; 321–345.

- A.P. Jakobi . International organisations and policy diffusion: The global norm of lifelong learning. Journal of International Relations and Development. 15 2012; 31–64.

- D.S.L. Jarvis . Risk, globalisation and the state: A critical appraisal of Ulrich Beck and the World Risk Society Thesis. Global Society: Journal of Interdisciplinary International Relations. 21 2007; 23–46.

- D.S.L. Jarvis . Race for the money: International financial centres in Asia. Journal of International Relations & Development. 14 2011; 60–95.

- D.S.L. Jarvis . Foreign direct investment and investment liberalisation in Asia: Assessing ASEAN's initiatives. Australian Journal of International Affairs. 66 2012; 223–264.

- D.S.L. Jarvis . Hong Kong must invest in its people or fall behind. 2014; South China Morning Post: Hong Kong (SAR), China A13. (Print edition). URL http://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/article/1510881/cash-rich-universities-singapore-south-korea-eclipsing-hong-kong Accessed 02.05.14.

- B. Jessop . The future of the capitalist state. 2002; Polity Press: Cambridge, MA

- JQRC. Joint Quality Review Committee. URL http://www.jqrc.edu.hk/index.files/AbtJQRC.htm Accessed 14.05.14..

- R. King . Policy internationalization, national variety and governance: Global models and network power in higher education states. Higher Education. 60 2010; 583–594.

- D. Levi-Faur . The global diffusion of regulatory capitalism. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 598 2005; 12–32.

- D. Levi-Faur . Varieties of regulatory capitalism: Getting the most out of the comparative method. Governance. 19 2006; 367–382.

- D. Levi-Faur . From big government to big governance?. Jerusalem Papers in Regulation & Governance. 2011. Working Paper 35, July. URL http://regulation.huji.ac.il/papers/jp35.pdf. Accessed 17.07.2014.

- D. Levi-Faur . The odyssey of the regulatory state: From a ‘thin’ monomorphic concept to a ‘thick’ and polymorphic concept. Law & Policy. 35 2013; 29–50.

- D.C. Levy . The global growth of private higher education. ASHE Higher Education Report. 36 2010; 121–133.

- D.C. Levy . How important is private higher education in Europe? A regional analysis in global context. European Journal of Education. 47 2012; 178–197.

- R.G. Lewis , D.H. Smith . Total quality in higher education. 1994; St. Lucie Press: Delray Beach, FL

- C. Leys . Market-driven politics: Neoliberal democracy and the public interest. 2001; Verso: London

- M. Lodge . Regulation, the regulatory state and European politics. West European Politics. 31 2008; 280–301.

- M. Lodge , K. Wegrich . Managing regulation: Regulatory analysis, politics and policy. 2012; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, England

- G. Majone . From the positive to the regulatory state: Causes and consequences of changes in the mode of governance. Journal of Public Policy. 17 1997; 139–167.

- M. Martin . Cross-border higher education: Regulation, quality assurance and impact. Vol. 1 2007; International Institute for Educational Planning, UNESCO: Paris

- C. Meseguer . Policy learning, policy diffusion, and the making of a new order. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 598 2005; 67–82.

- C. Meseguer , F. Gilardi . What is new in the study of policy diffusion?. Review of International Political Economy. 16 2009; 527–543.

- R. Mishra . Globalization and the welfare state. 1999; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham

- K.H. Mok . Impact of globalization: A study of quality assurance systems of higher education in Hong Kong and Singapore. Comparative Education Review. 44 2000; 148–174.

- K.H. Mok . The quest for world class university: Quality assurance and international benchmarking in Hong Kong. Quality Assurance in Education: An International Perspective. 13 2005; 277–304.

- K.H. Mok , A.B.L. Cheung . Global aspirations and strategising for world-class status: New form of politics in higher education governance in Hong Kong. Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management. 33 2011; 231–251.

- H. Obinger , C. Schmitt , P. Starke . Policy diffusion and policy transfer in comparative welfare state research. Social Policy & Administration. 47 2013; 111–129.

- J. Peck , N. Theodore , N. Brenner . Neoliberalism resurgent? Market rule after the great recession. South Atlantic Quarterly. 111 2012; 265–288.

- K. Polanyi . The great transformation. 1st Beacon paperback ed., 1957; Beacon Press: Boston

- QAC. (n.d.). Audit manual: Second audit cycle. Quality Assurance Council, University Grants Committee. URL http://www.ugc.edu.hk/eng/doc/qac/manual/auditmanual2.pdf Accessed 05.05.14..

- QR. Qualifications register (QR). Hong Kong Council for Accreditation of Academic and Vocational Qualifications (HKCAAVQ). URL http://www.hkqr.gov.hk/HKQR/commonMaint.do?go_target=welcome Accessed 12.05.14..

- RGC. Research Grants Council (Hong Kong). URL http://www.ugc.edu.hk/eng/rgc/about/about.htm Accessed 14.05.14..

- R. Robertson . Globalization: Social theory and global culture. 1992; Sage: London

- W.W. Rostow . The stages of economic growth: A non-communist manifesto. 2nd ed., 1971; Cambridge University Press: London

- J.G. Ruggie . International regimes, transactions, and change: Embedded liberalism in the postwar economic order. International Organization. 36(2): 1982; 379–415.

- M.J. Sandel . What money can’t buy: The moral limits of markets. 2012; Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York

- G. Shiev . Educational expansions and the labour force. G.A. Postiglione . Education and society in Hong Kong: Towards one country and two systems. 1992; Hong Kong University Press: Hong Kong 201–234.

- C.R. Shipan , C. Volden . Policy diffusion: Seven lessons for scholars and practitioners. Public Administration Review. 72 2012; 788–796.

- P. Starke , H. Obinger , F.G. Castles . Convergence towards where: In what ways, if any, are welfare states becoming more similar?. Journal of European Public Policy. 15 2008; 975–1000.

- M. Tam . Quality assurance policies in higher education in Hong Kong. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management. 21 1999; 215–226.

- C. Teelken . Compliance or pragmatism: How do academics deal with managerialism in higher education? A comparative study in three countries. Studies in Higher Education. 37 2012; 271–290.

- UGC . Higher education 1991–2001 — An interim report. 1993; University Grants Committee. URL http://www.ugc.edu.hk/eng/ugc/publication/report/interim/interim.htm Accessed 12.05.14.

- UGC . Higher education in Hong Kong — A report by the University Grants Committee. 1996. URL http://www.ugc.edu.hk/eng/ugc/publication/report/hervw/ugcreport.htm Accessed 09.05.14.

- UGC . UGC quadrennial report 1991–1995. 1996; University Grants Committee. URL http://www.ugc.edu.hk/eng/ugc/publication/report/quad_rpt/quad_rpt.htm Accessed 04.05.14.

- UGC . Aspirations for the higher education system in Hong Kong: Report of the University Grants Committee. 2010. URL http://www.ugc.edu.hk/eng/ugc/publication/report/her2010/her2010.htm Accessed 16.05.14.

- UGC . UGC annual report 2012–2013. 2013. URL http://www.ugc.edu.hk/eng/doc/ugc/publication/report/AnnualRpt1213/full.pdf Accessed 14.05.14.

- UGC. Mission Statement of the University Grants Committee. URL http://www.ugc.edu.hk/eng/ugc/about/overview/mission.htm Accessed 15.05.14..

- UGC. University Grants Committee Activities. URL http://www.ugc.edu.hk/eng/ugc/activity/activity.htm Accessed 14.05.14..

- I. Vormedal . States and markets in global environmental governance: The role of tipping points in international regime formation. European Journal of International Relations. 18 2012; 251–275.

- L. Weiss . The myth of the neoliberal state. C. Kyung-Sup , B. Fine , L. Weiss . Developmental politics in transition: The neoliberal era and beyond. 1st ed., 2012; Palgrave Macillan: New York 27–42.