Abstract

Perceptions of the pervasive and persistent failures of governments in many issue areas over the past several decades have led many commentators and policy makers to turn to non-governmental forms of governance in their efforts to address public problems. During the 1980s and 1990s, market-based governance techniques were the preferred alternate form to government hierarchy but this preference has tilted towards network governance in recent years. Support for these shifts from hierarchical to non-hierarchical governance modes centre on the argument that traditional government-based arrangements are unsuited for addressing contemporary problems, many of which have a cross-sectoral or multi-actor dimension which is difficult for hierarchies to handle. Many proponents claim that recent ‘network governance’ or ‘collaborative governance’ arrangements combine the best of both governmental and market-based alternatives by bringing together key public and private actors in a policy sector in a constructive and inexpensive way. This claim is no more than an article of faith, however, as there is little empirical evidence supporting it. Indeed both logic and evidence suggests that networks too suffer from failures, though the sources of these failure may be different from other modes. The challenge for policymakers is to understand the origin and nature of the ways in which different modes of governance fail so that appropriate policy responses may be devised. This article proposes a model of such failures and a two-order framework for understanding them which helps explain which mode is best, and worst, suited to which circumstance.

1 Introduction: understanding governance failures

Governance reforms have been at the centre of policy discussions in both developed and developing countries since the 1980s. Many of the ensuing reforms have featured waves of administrative re-structuring, privatizations, de-regulation and decentralization and similar efforts, followed by varying degrees of reversals as the failures of those reforms became apparent (CitationRamesh & Howlett, 2006; Ramesh, Araral, & Wu, 2010).

Many of these reforms can be characterized as efforts to shift an existing governance mode to another mode involving a less direct role for government (CitationTreib, Bahr, & Falkner, 2007). Initially, the sentiment behind many such reform efforts favoured transitions from direct provision or regulation by the government to allocation by markets or by private actors operating under minimal regulation in non-state market-driven efforts (CitationCashore, 2002; Cutler et al., 2000). In more recent years, the tilt has shifted towards transitions from hierarchical, private and market forms of governance to more network-centred governance modes (CitationLange et al., 2013; Lowndes & Skelcher, 1998; Weber, Driessen, & Runhaar, 2011).

The underlying sentiment of the debate and actual measures taken in the initial set of reforms was typically “anything but the government” (CitationChristensen & Lægreid, 2008). Much discussion on the subject, for example, suggested that shifts from hierarchical to non-hierarchical governance were both unavoidable and desirable for addressing complex multi-actor problems which more traditional government-based arrangements found difficult to ‘steer’ (CitationLange et al., 2013; Weber et al., 2011). Many proponents of alternative governance modes claimed other kinds of relationships involved in activities such as ‘network governance’ or ‘collaborative governance’ combined the best of both governmental and market-based arrangements by bringing together key public and private actors in a policy sector in a constructive and inexpensive way (CitationRhodes, 1997). This claim was no more than an article of faith, however, and there is little evidence supporting and much contradicting this thesis (see CitationAdger & Jordan, 2009; Howlett, Rayner, & Tollefson, 2009; Hysing, 2009; Kjær, 2004; Van Kersbergen & Van Waarden, 2004). Network governance techniques could just as easily compound the ill-effects of governments and market forms rather than improve upon them. Further, because power is by design diffused in network governance arrangements, such arrangements can be much harder than traditional hierarchical forms to reform or dismantle when problems arise.

This is a subject area requiring further examination as more recent efforts at reform in many countries and sectors, for example, have sought to correct or reverse excesses in ‘de-governmentalization’ from this earlier period, often introducing hybrid elements into existing governance modes (CitationRamesh & Fritzen, 2009; Ramesh & Howlett, 2006; Ramesh et al., 2010). Many key sectors from health to education and others now have either returned to older modes or feature ‘hybrid’ forms of governance containing elements of hierarchical approaches — regulation, bureaucratic oversight and service delivery — as well as either or both market and network-based hierarchical and non-hierarchical approaches — such as markets, voluntary organizations, and increasingly co-production (CitationBrandsen & Pestoff, 2006; Pestoff, 2006, 2012; Pestoff, Osborne, & Brandsen, 2006).

Which of these modes of governance best fits a given circumstance and which is likely to function effectively, however, remain under-examined. In order to shed light on the critical issues of appropriateness and significance of different governance arrangements, in this article we revisit the concept of governance, and derive a model of basic governance types. We then propose a model and a framework for understanding governance modes which highlights the role played in mode effectiveness by problem contexts, capacity and design issues. The framework suggests that two orders of failure linked to these issues affect governance arrangements and applies it to each principle mode of governance. The framework helps explain which mode is best suited to which circumstance and why.

2 Revisting the concept of government failures: understanding governance modes in theory and practice

Governing is what governments do: controlling the allocation of resources among social actors; providing a set of rules and operating a set of institutions setting out ‘who gets what, where, when, and how’ in society; and managing the symbolic resources that are the basis of legitimacy (CitationLasswell, 1958). In its broadest sense public, “governance” describes the mode of government coordination of societal actors exercised by state actors in their efforts to solve familiar problems of collective action inherent to government and governing (Citationde Bruijn & ten Heuvelhof, 1995; Klijn & Koppenjan, 2000; Kooiman, 1993, 2000; Majone, 1997; Rhodes, 1997). That is, ‘governance’ is about establishing, promoting and supporting a specific type of relationship between governmental and non-governmental actors in the governing process.

Governance thus involves the establishment of a basic set of relationships between governments and their citizens. Early models of governance types such as that developed by Pierre (2000), for example, distinguished between only two such modes — state-centric “old governance” and society-centric “new governance”. Similarly, many economists also compared and contrasted only two types: “market” and ‘hierarchical” or legal relationships (CitationWilliamson, 1975). In modern capitalist societies, however, ‘governance’ is a three-way relationship and involves managing relations with both businesses and civil society organizations involved in the creation of public value and the delivery of goods and services to citizens (CitationHall & Soskice, 2001; Steurer, 2013).

Even with just these three basic sets of actors and relationships, however, governance arrangements can take many shapes (CitationTreib et al., 2007). In addition to the ‘market’ and ‘legal’ modes discussed earlier, other significant modes have been proposed by authors such as CitationPeters (1996), CitationConsidine and Lewis (1999), CitationNewmann (2001), Kooiman (2003) and CitationCashore (2002). These include types such as community-based ‘network’ governance and pure ‘private’ governance with little or no state involvement.

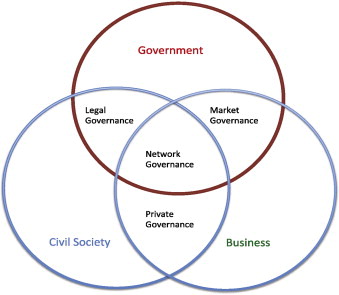

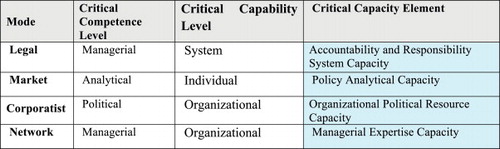

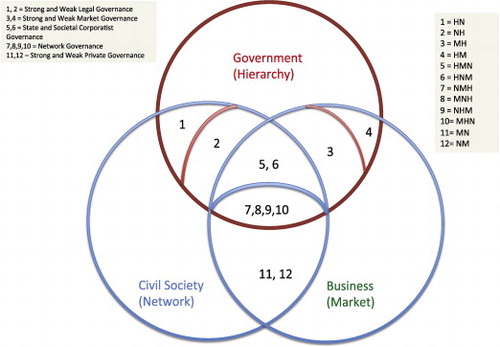

As CitationSteurer (2013) suggested, in illuminating the universe of possible governance modes, the three basic sets of governance actors can be portrayed as a Venn diagram: that is, as an overlapping series of sets which produce a governance mode in their overlapping compartments (see Fig. 1 ). Three of these modes are ‘public’ and one ‘private’.

Source: Modified from CitationSteurer (2013).

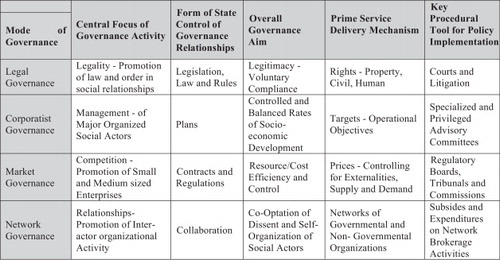

While these four general types — legal, market, network and private — exist, different combination of relationships of superiority and dominance of specific actors within each governance sphere occur and can colour or alter what kinds of activities occur within a mode. Thus, for example, a mode can combine hierarchical and network relationships in which one or the other dominates — in weak or strong versions of legal governance — and this same distinction extends to each of the other two basic bilateral modes as well. An even more complex set of relationships exists within network modes which have a trilateral nature to begin with. In such modes, various kinds of three-sided relationships exist in which two — “corporatist” — modes combine networks and markets within a general hierarchical framework, while four others exhibit prominence of network or market (CitationConsidine & Lewis, 1999). In practice this form of governance is often found in situations in which a ‘middle’ or intermediate strata of large associations — from churches to business and labour organizations — interact with governments and dominate policy-making processes (CitationCawson, 1978; Von Beyme, 1983). This variety of different modes or sub-modes is depicted in Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2 Additional forms of ideal type modes of governance accounting for dominant and subordinate partners.

Source: Ramesh and Howlett (2014).

Each of these dozen sub-types has its own distinct features which have implications for public policy and governance outputs and outcomes. However, not all are equally relevant when discussing ‘public’ governance and some of the variations exist more as logical constructs than empirical realities. As CitationCashore (2002) noted, for example, pure non-governmental governance arrangements (types 11 and 12 in Fig. 2) such as those found in certification and private standard setting schemes are not in the public realm and need not necessarily concern governments or those studying ‘public’ policy-making (see also CitationCutler, Haufler, & Porter, 1999). Thus we can often eliminate from most discussions of public policy alternatives those types of purely private or non-governmental governance that have no government partner or relationship. Notwithstanding this, however, those in government designing systems of governance, and scholars of public policy more generally can nevertheless enhance their ability to contribute to improved governance in the public domain through drawing careful lessons from the workings of more private forms of governance. Indeed, the whole literature on comparative institutional analysis emerges from this insight (see, e.g., CitationMintrom, 2012, Chapter 12).

Second, as CitationCapano (2011) has argued, the government remains a major actor in most actually existing public governance arrangements. Government is a central player in all public modes, either potentially or actually, though the nature and level of its involvement varies considerably by sub-type. That is, government has the inescapable task of defining what governance is, or can be, and may choose to allow a higher degree of freedom to other policy actors with regard to the goals to be pursued and the means to be employed, but can always retract that authority (CitationCapano, 2011; Meuleman, 2010). Thus what may appear to be purely bilateral government-business or government-civil society relationships (types 2 and 3 in Fig. 2) live ‘under the shadow of hierarchy’ (CitationHeritier & Lehmkuhl, 2008) in the sense that government authority remains paramount in those governance modes. Hence the nuances pertaining to, for example, the possibility of sub-types in which market and network actors could exercise leadership in bilateral legal and market regimes can also often be disregarded.

The ability of government to exercise its authority or steer governance relationships, however, is lower when trilateral rather than bilateral arrangements are involved. In these contexts governments may be dominated by both market and network actors. This occurs in six instances (types 5–10) set out in Fig. 2. These can thus be divided into four ‘network’ types (types 7–10 in Fig. 2) in which hierarchical forms of control are subordinated to one or more of the other two, and two other corporatist forms (Types 5 and 6) in which hierarchical coordination principles remain dominant. Adding this ‘corporatist’ type to the basic three public forms identified in Fig. 1 leaves four types or modes of governance as basic public modes existing alongside private modes.

Considine (2001) offers a useful framework for describing the principle elements and differences between these basic types which takes into account their overall governance aims and the primary service delivery and policy tool preferences which flow from their central focus of activity and form of state or non-state steering relationships (see Fig. 3 ). This association of governance types with policy tools and steering mechanisms is useful for discerning the manner in which each governance type is likely to succeed or fail in it appointed tasks.

Source: Modified from Considine (2001).

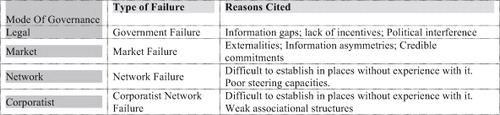

Examples of the types of failures most commonly identified in the literature as associated with each type of public governance mode identified above are summarized in Fig. 4 . An extensive literature exists on each of these subjects, dealing with situations in which governments fail to adopt efficient solutions to problems — “government failures” (LeGrand, 1991; CitationWolf, 1979); to those in which markets fail to produce such outcomes — “market failures” (CitationWeimer & Vining, 2011; Wolf, 1987); and where networks are weak and may be difficult to establish, be they corporatist or otherwise in nature — “network failures” (CitationGiest & Howlett, 2013; Lehmbruch & Schmitter, 1979; Salamon, 1987; Von Tunzelmann, 2010). This is only a start, however, in understanding and analysing governance failures, due to lack of clarity about the linkage of particular rationales for failure to specific governance modes. In the following section we propose a two-order model of governance failure which brings order and clarity to the subject.

Source: CitationWu and Ramesh (2014).

3 Two orders of governance failure

The objective of governance is government steering or directing key actors to perform desired tasks in pursuit of collective goals. The performance of any of the public governance modes set out in Fig. 4 — that is, discounting the purely private forms outlined in Fig. 1 — is affected by a government's ability to exercise its role and provide the level of co-ordination that each particular governance mode requires. Even under the most “horizontal” or “plurilateral” arrangements involved in very loose network or market-based modes (CitationZielonka, 2007), governance relationships still need to be ‘steered’ towards common goals and the rules of private exchanges need to be defined and enforced. Thus, as we have seen, in all four public modes of governance the role of the government may vary and change, but remains a core element rather than something existing in opposition to, or outside of, it.

Constraints on a government's ability or capacity to steer or shape governance relationships are thus a critical determinant of the propensity of any mode of governance to fail (CitationWu & Ramesh, 2014) and these competence or capability constraints exist at two different levels or ‘orders’ of governance relationships. These relate to the ‘first order’ failures linked to the problem contexts with which governance relationships are expected to cope; and ‘second order’ failures linked to government capacity issues. Each of these constraints is examined in turn below.

3.1 First order governance design failures: the mismatch of problem context and governance mode

First order governance failures relate to steering or operational failures which are caused by fundamental mismatches between the governance mode in place and the nature of the problem it is expected to address. This is the most often explored type of governance failure (e.g. CitationWu & Ramesh, 2014) in which a governance mode proves operationally incapable of addressing a specific kind of problem given the specific attributes of that problem and what it would take to overcome it.

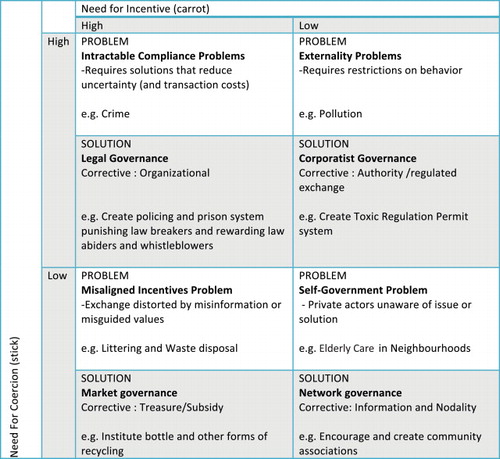

In this case, the “problem” of governance is the level of difficulty a government faces in securing compliance with its wishes and the availability of tools for securing compliance (CitationWeaver, 2014). Some compliance problems can be corrected or handled within the specific kinds of governance relationships found in an existing mode, providing a virtuous match between governance mode and problem context. Hence for example, if a compliance problem is one linked to incorrect incentives, then an existing market governance mode should be able to deal effectively with such an issue. However if the main problem is uncertainty and risk, then more predictable and certain traditional legal governance mechanisms are better suited than market ones. Similarly if a problem is amenable to voluntary regulation or co-production, then a network governance mechanism should suffice to deal with it if that option is available in practice. However, in the presence of externalities and other collection action problems that preclude private or network solutions, more corporatist or government-centric forms of governance would be more effective and appropriate. These basic problem-solution contexts and their appropriate governance mode are set out in Fig. 5 below.

Hence a very distinct and real possibility in every policy-making context is that an existing governance regime may be inappropriate or ineffective in dealing with a specific problem type. The mismatch of problem and governance mode generates governance design failures either where poor diagnoses of problems exist and/or when a misaligned mode of governance exists even when a problem is diagnosed correctly. The challenge for policy analysts and policy makers in the case of these first order governance failures is to correctly identify the specific characteristics of the problem and ensure the mechanisms to address them are congruent with the existing governance mode or, if not, to change the mode (CitationHowlett & Rayner, 2013).

3.2 Second order governance capacity failures: the mismatch of governance mode and governance capacity

A second level of governance failures occurs when the choice of governance mode is correct but the need for action re-structuring aspects of existing governance relationships within that mode is not matched by the governmental capacity necessary for its accomplishment. That is, in a situation where the governance system in place is fundamentally correct and aligned with the nature of the governance problem but the competences and capabilities of the government may be inadequate to design and implement a policy solution.

The term “governance capacity” here refers to the resources and skills a government requires to steer a governance mode so as to make sound policy choices and implement them effectively. Governance capacity is at heart a function of administrative and political resources that affect the ability of governments in their relationships with other governance actors: analytical ones which allow policy alternatives to be effectively generated and investigated; managerial ones which allow state resources to be effectively brought to bear on policy issues; and political ones which allow policy-makers and managers the room to manouevre and the support required to develop and implement their ideas, programmes and plans (CitationFukuyama, 2013; Gleeson, Legge, & O’Neill, 2009; Gleeson, Legge, O’Neill, & Pfeffer, 2011 Citation; Rotberg, 2014; Tiernan & Wanna, 2006; Wu, Ramesh, Howlett, & Fritzen, 2010).

At the extreme, for example, “hollowing out” a government through budget cuts, layoffs and contracting out weakens its ability to employ a “command and control” approach to policy-making and, as a result, undermines the ability of any legal or market form of governance dependent on such instruments to function effectively (CitationOsborne, 2006). Similarly, the default reform often adopted by governments seeking to improve upon hierarchical governance in recent years, as we have seen, was to turn to a market or network mode of governance. In contrast to networks, which may take some time to create if they do not already exist, the adoption of market governance arrangements in theory is relatively easy, in at least their simplest form, because all the government has to do is reduce its involvement in the provision of the goods and services in question with the expectation the market will arise to fill the void.

In all likelihood, however, the resulting market will be both inefficient and inequitable due to the kinds of market failures that characterize many sectors and activities and prevent markets from functioning efficiently or effectively (Weimer and Vining 2009). To function effectively, markets require tough but sensible regulations that are diligently implemented, conditions that are difficult for many governments to meet due to a lack of analytical, managerial, and/or political competences or capabilities. Without adequate capacity to regulate a sector, government may turn to subsidizing users and/or providers which may be politically expedient but is vulnerable to cost increases and other factors that can undermine a program's long-term viability (CitationWu & Ramesh, 2014).

In such circumstances, hierarchical governance need not be as dysfunctional as stylized descriptions by proponents of market and network governance may suggest and, in fact, may be superior to those alternatives (CitationHill & Lynn, 2005; Peters, 2004). A health care system characterized by government provision and financing supplemented by capped payment, for example, is an effective means of delivering services such as health care at affordable cost (Li et al., 2007) but it too requires the government capacity to do so. Similarly, network governance may perform well where dealing with sensitive issues such as aspects of health or educational policy and service delivery like child and parental care where trust and understanding is paramount (Pestoff et al., 2012). But it requires pre-existing networks and associations that can be steered. In many instances, civil society organizations may not be sufficiently organized or resourced to be able to offer effective network forms of governance (CitationVon Tunzelmann, 2010).

While all kinds of skills and resources are necessary for effective governance, different governance arrangements require different sets of competences and capabilities in order to succeed. Shortcomings in one or a few of these may sometimes be offset by strengths in others but no government can expect to be capable if lagging along many dimensions (CitationTiernan & Wanna, 2006). Moreover specific modes of governance will fail if they have ‘critical capacity’ gaps; that is, are missing capacity in key areas which define activities within a mode of governance.

Networks will fail, for example, when governments encounter capacity problems at the organizational level such as a lack of societal leadership, poor associational structures and weak state steering capacities which make adoption of network governance modes problematic. As CitationKeast, Mandell, and Brown (2006) note, at the level of competences, networks raise severe managerial challenges: “Networks often lack the accountability mechanisms available to the state, they are difficult to steer or control, they are difficult to get agreements on outcomes and actions to be taken, and they can be difficult to understand and determine who is in charge”. A recurrent problem faced by efforts to utilize network governance, for example, is that the routines, trust, and reciprocity which characterize successful network management (cf CitationKlijn & Koppenjan, 2012) take a long time to emerge. Such relationships cannot simply be established by fiat as in the case with hierarchy or emerge spontaneously in response to forces of demand and supply, as in markets.

Legal systems of governance similarly also required high level of managerial skills in order to avoid diminishing returns with compliance or growing non-compliance with government rules and regulations (CitationMay, 2005). Thus for example, while there have been advances in identifying the key traits of effective managers, little is known about how to train managers to be effective leaders and this is especially crucial in hierarchical modes of governance featuring direct government direction and control. Shortfalls in system level capabilities are also pervasive in this mode of governance as recruiting and retaining leaders is difficult for the public sector (CitationBritish Cabinet Office, 2001). The cumbersome accountability mechanisms in place in the public sector promote risk aversion, whereas risk-taking is an essential trait of leaders. The culture of blame for failures is another factor that stymies leadership in the public sector (CitationHood, 2010). Unclear division of responsibilities between elected and appointed officials also makes it difficult for the latter to exercise leadership.

For corporatist modes, the importance of efficient administrative structures and processes and the vital importance of coordination therein, cannot be overstated. Inspired by conceptions of chain of command in the military, corporatist regimes stress hierarchy, discipline, due process, and clear lines of accountability. Unlike markets where prices seamlessly perform coordination functions, this must be actively promoted in corporatist forms of government and combined with political skills in understanding stakeholder needs and positions (CitationBerger, 1981; Lehmbruch & Schmitter, 1982). At the level of capabilities, corporatist modes of governance require a great deal of coherence and coordination to function effectively due to horizontal divisions and numerous hierarchical layers found in their bureaucratic structures (CitationLehmbruch & Schmitter, 1982; Wilensky & Turner, 1987).

As for market governance, as already mentioned above, technical knowledge is a critical competence required for success. Analytical skills at the level of individual analysts and policy workers are key here and the policy analytical capacity of government needs to be especially high to deal with complex quantitative economic and financial issues involved in regulating and steering a sector and preventing crises (CitationHowlett, 2009; Rayner, McNutt, & Wellstead, 2013). Effective information systems within agencies are critical for correcting information asymmetry problems so that markets can function efficiently.

Each of these gaps highlights the need for adequate capacity in these critical areas if a governance system is to achieve its potential. The ‘critical’ capacity element in each mode is set out in Fig. 6 below.

4 Conclusion: diagnosing governance failures and improving governance performance

Practical experience and ideological predilections have shaped the substance of much existing literature on governance, ranging from preferences for democracy, popular participation and consensus to concerns about budget deficits and public sector inefficiencies. These have generally criticized hierarchy-based systems and driven preferences for the increased or enhanced use of network and market forms of governance (CitationMeuleman, 2009).

Lost in the pursuit of these ideologically preferred alternatives, however, is the understanding of whether or not a preferred governance mode can actually address a particular sector's problems. Instead of analysing and understanding the specifics of the sector in question, the protagonists often simply extrapolate from idealized conceptions of how non-hierarchical modes of governance might work in theory and then apply them across sectors regardless of the nature of the problem to which they are being applied on a government's capacity to address it. Such first order governance failures are common, but as little investigated and poorly understood as second order capacity ones.

The notion of ‘governance failures’ is a useful way to describe the situations which occur when the essential requisites of a governance mode are not met or when a mode is fundamentally misaligned with the problem with which it is supposed to deal. The term joins the policy studies lexicon along with concepts such as ‘government failures’, ‘market failures’ and the “network failures” (CitationLe Grand, 1991; Provan & Kenis, 2008; Von Tunzelmann, 2010; Weimer & Vining, 2011; Weiner & Alexander, 1998; CitationWolf, 1987; Uribe, 2012). Although the failures of network and corporatist modes have not been as well explored as market and government failures, the existing literature on all four is unsatisfactory. The two-order model of failures set out here attempts to bring come clarity and illumination to this subject.

Given that all governance modes are vulnerable to specific kinds of failures due to their inherent vulnerabilities in different problem contexts, when governments reform or try to shift from one mode to the other modes, they need to understand both the nature of the problem they are trying to address, the skills and resources they have at their disposal to address it, and the innate features of the different governances modes and the capabilities and competences each requires in order to operate at a high level of performance. If factors such as problem contexts and critical capacity deficits are not taken into account, then any short-term gain enjoyed by politicians pandering to contemporary political preferences is likely to be offset later when the consequences of governance failures and poor institutional designs become apparent (CitationHood, 2010; Weaver 1986), as is currently the core in many sectors and countries.

References

- W.N. Adger , A.J. Jordan . Governing sustainability. 2009; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge

- S. Berger . Organizing interests in Western Europe: Pluralism, corporatism and the transformation of politics. 1981; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge

- T. Brandsen , V. Pestoff . Co-Production, the third sector and the delivery of public services. Public Management Review. 8 2006; 493–501.

- British Cabinet Office . Strengthening leadership in the public sector. 2001 http://www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/media/cabinetoffice/strategy/assets/piu20leadership.pdf

- G. Capano . Government continues to do its job. A comparative study of governance shifts in the higher education sector. Public Administration. 89 2011; 1622–1642.

- B. Cashore . Legitimacy and the privatization of environmental governance: How non-state market-driven (NSMD) governance systems gain rule-making authority. Governance. 15(4): 2002; 503–529.

- A. Cawson . Pluralism, corporatism and the role of the state. Government and Opposition. 13(2): 1978; 178–198.

- T. Christensen , P. Lægreid . NPM and beyond—structure, culture and demography. International Review of Administrative Sciences. 74(1): 2008; 7–23.

- M. Considine , J. Lewis . Governance at ground level: The frontline bureaucrat in the age of markets and networks. Public Administration Review. 59 1999. 467-460.

- A.C. Cutler , V. Haufler , T. Porter . The contours and significance of private authority in international affairs. A.C. Cutler , V. Haufler , T. Porter . Private authority and international affairs. 1999; State University of New York: Albany 333–376.

- J.A. de Bruijn , E.F. ten Heuvelhof . Policy networks and governance. D.L. Weimer . Institutional design. 1995; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston 161–179.

- F. Fukuyama . What is governance?. Governance. 2013

- S. Giest , M. Howlett . Understanding the pre-conditions of commons governance: The role of network management. Environmental Science & Policy. 2013 10.1016/j.envsci.2013.07.010.

- D.H. Gleeson , D.G. Legge , D. O’Neill . Evaluating health policy capacity: Learning from international and Australian experience. Australia and New Zealand Health Policy. 6(1): 2009

- D. Gleeson , D. Legge , D. O’Neill , M. Pfeffer . Negotiating tensions in developing organizational policy capacity: Comparative lessons to be drawn. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice. 13(3): 2011; 237–263.

- P.A. Hall , D. Soskice . Varieties of capitalism: The institutional foundations of comparative advantage. 2001; Oxford University Press: Oxford

- A. Heritier , D. Lehmkuhl . Introduction: The shadow of hierarchy and new modes of governance. Journal of Public Policy. 28(1): 2008; 1–17.

- C.J. Hill , L.E. Lynn . Is hierarchical governance in decline? Evidence from empirical research. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 15 2005; 173–195.

- C. Hood . The blame game: Spin, bureaucracy, and self-preservation in government. 2010; Princeton University Press: Princeton

- M. Howlett , J. Rayner , C. Tollefson . From government to governance in forest planning? Lesson from the case of the British Columbia great bear rainforest initiative. Forest Policy and Economics. 11 2009; 383–391.

- M. Howlett , J. Rayner . Patching vs packaging in policy formulation: Assessing policy portfolio design. Politics and Governance. 1(2): 2013; 170–182. 10.12924/pag2013.01020170.

- M. Howlett . Governance modes, policy regimes and operational plans: A multi-level nested model of policy instrument choice and policy design. Policy Sciences. 42(1): 2009; 73–89.

- E. Hysing . From government to governance? A comparison of environmental governing in Swedish forestry and transport. Governance. 22 2009; 547–672.

- R. Keast , M. Mandell , K. Brown . Mixing state, market and network governance modes: The role of government in “Crowded” policy domains. International Journal of Organization Theory and Behavior. 9(1): 2006; 27–50.

- A.M. Kjær . Governance. 2004; Polity Press: Cambridge

- E.H. Klijn , J.F.M. Koppenjan . Public management and policy Networks: Foundations of a network approach to governance. Public Management. 2 2000; 135–158.

- E.-H. Klijn , J. Koppenjan . Governance network theory: Past, present and future. Policy & Politics. 40(4): 2012; 587–606.

- J. Kooiman . Governance and governability: Using complexity, dynamics and diversity. J. Kooiman . Modern governance. 1993; Sage: London 35–50.

- J. Kooiman . Societal governance: Levels, models, and orders of social-political interaction. J. Pierre . Debating governance. 2000; Oxford University Press: Oxford 138–166.

- P. Lange . Governing towards sustainability—Conceptualizing modes of governance. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning. 2013

- H. Lasswell . Politics: Who gets what, when, how. 1958; Meridian: New York

- J. Le Grand . The theory of government failure. British Journal of Political Science. 21(4): 1991; 423–442.

- G. Lehmbruch , P. Schmitter . Patterns of corporatist policy-making. 1982; Sage: London

- G. Lehmbruch , P. Schmitter . Trends towards corporatist intermediation. 1979; Sage: London

- V. Lowndes , C. Skelcher . The dynamics of multi-organizational partnerships: An analysis of changing modes of governance. Public Administration. 76 1998; 313–333.

- G. Majone . From the positive to the regulatory state: Causes and consequences of changes in the mode of governance. Journal of Public Policy. 17 1997; 139–167.

- P.J. May . Regulation and compliance motivations: Examining different approaches. Public Administration Review. 65(1): 2005; 31–44.

- L. Meuleman . ‘Metagoverning governance styles: Increasing the metagovernors’ toolbox. Paper presented at the panel ‘Metagoverning interactive governance and policymaking’, ECPR general conference. Potsdam, 10–12 September 2009 2009

- L. Meuleman . Public Management and the Metagovernance of Hierarchies, Networks and Markets: The Feasibility of Designing and Managing Governance Style Combinations. 2010; Physica-Verlag HD.

- M. Mintrom . “Comparative institutional analysis.” Chapter 12 in contemporary policy analysis. 2012; Oxford University Press: New York

- J. Newmann . Modernising governance: New labour policy and society. 2001; Sage: London/Newbury Park, CA

- S.P. Osborne . The new public governance?. Public Management Review. 8(3): 2006; 377–387.

- B.G. Peters . Governing: Four emerging models. 1996; University Press of Kansas: Lawrence, KS

- B.G. Peters . The search for coordination and coherence in public policy: Return to the center?. 2004

- V. Pestoff . Citizens and co-production of welfare services. Public Management Review. 8 2006; 503–519.

- V.A. Pestoff , T. Brandsen , B. Verschuere . New public governance, the third sector and co-production. 2012; Routledge: New York

- V. Pestoff , S.P. Osborne , T. Brandsen . Patterns of co-production in public services. Public Management Review. 8 2006; 591–595.

- K.G. Provan , P. Kenis . Modes of network governance: Structure, management, and effectiveness. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 18(2): 2008; 229–252.

- M. Ramesh , M. Howlett . Deregulation and its discontents: Rewriting the rules in Asia. 2006; Edward Elgar: Aldershot

- M. Ramesh , S. Fritzen . Transforming Asian governance: Rethinking assumptions, challenging practices. 2009; Routledge: London/New York

- M. Ramesh , E. Araral , X. Wu . Reasserting the public in public services. 2010; Routledge.

- J. Rayner , K. McNutt , A. Wellstead . Dispersed capacity and weak coordination: The challenge of climate change adaptation in Canada's forest policy sector. Review of Policy Research. 30(1): 2013; 66–90.

- R.A.W. Rhodes . Understanding governance: Policy networks, governance, reflexivity and accountability. 1997; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK

- R.I. Rotberg . Good governance means performance and results. Governance. 2014 10.1111/gove.12084.

- L.M. Salamon . Of market failure, voluntary failure, and third-party government: Toward a theory of government-nonprofit relations in the modern welfare state. Journal of Voluntary Action Research. 16(1/2): 1987; 29–49.

- R. Steurer . Disentangling governance: A synoptic view of regulation by government, business and civil society. Policy Sciences. 46(4): 2013; 387–410.

- A. Tiernan , J. Wanna . Competence, capacity, capability: Towards conceptual clarity in the discourse of declining policy skills. Presented at the Govnet international conference. Australian National University 2006; ANU: Canberra

- O. Treib , H. Bahr , G. Falkner . Modes of governance: Towards a conceptual clarification. Journal of European Public Policy. 14 2007; 1–20.

- C.A. Uribe . The Dark Side of social capital re-examined from a policy analysis perspective: Networks of Trust and corruption. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice. 2012 10.1080/13876988.2012.741441.

- K. Van Kersbergen , F. Van Waarden . Governance as a bridge between disciplines: Cross-disciplinary inspiration regarding shifts in governance and problems of governability, accountability and legitimacy. European Journal of Political Research. 43 2004; 143–171.

- K. Von Beyme . Neo-corporatism: A new nut in an old shell?. International Political Science Review. 4(2): 1983; 173–196.

- N. Von Tunzelmann . Technology and technology policy in the postwar UK: Market failure or network failure?. Revue d’économie industrielle, Numéro. 129–130 2010; 237–258.

- R.K. Weaver . Compliance regimes and barriers to behavioral change. Governance. 27(2): 2014; 243–265. 10.1111/gove.12032.

- M. Weber , P.P.J. Driessen , H.A.C. Runhaar . Environmental noise policy in the Netherlands: Drivers of and barriers to shifts from government to governance. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning. 13 2011; 119–137.

- D.L. Weimer , A. Vining . Policy analysis: Concepts and practice. 5th ed., 2011; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ

- H.L. Wilensky , L. Turner . Democratic corporatism and policy linkages: The interdependence of industrial, labor-market, incomes, and social policies in eight countries. 1987; Institute of International Studies: Berkeley

- O.E. Williamson . Markets and hierarchies. 1975; Free Press: New York

- C. Wolf Jr. . Markets and non-market failures: Comparison and assessment. Journal of Public Policy. 7(1): 1987; 43–70.

- C. Wolf Jr. . A theory of nonmarket failure: Framework for implementation analysis. The Journal of Law and Economics. 22(1): 1979; 107–139.

- X. Wu , M. Ramesh , M. Howlett , S. Fritzen . The public policy primer: Managing public policy. 2010; Routledge: London

- X. Wu , M. Ramesh . Market imperfections, government imperfections, and policy mixes: Policy innovations in Singapore. Policy Sciences. 2014; 1–16.

- J. Zielonka . Plurilateral governance in the enlarged European Union. Journal of Common Market Studies. 45(1): 2007; 187–209.