Abstract

Performance measurement is most often considered as the apolitical application of the use of information, collected and used to demonstrate effectiveness against a set of criteria. In reality, many complexities are hidden behind this seemingly rational and technical enterprise. This paper establishes a conceptual framework for the collection of articles in this volume. It examines the politics of performance measurement — who decides what should be measured, how, and why — and its consequences. It analyses why performance measurement is important, outlines its explicit and implicit purposes and the fundamental assumptions underpinning it, and describes its problems, paradoxes and consequences. A chain of performance measurement is then proposed and two contrasting versions of it (one rational-technical and one realistic-political) are presented. This social structural and political institutional approach to performance measurement highlights dynamics, interactivity and power. In doing so, it discloses the politics and consequences of performance measurement.

1 Introduction

If information is power, then performance measurement is surely tightly linked to the creation and use of power. And, given humans’ lack of ability to accurately predict the outcomes of social interventions, performance measurement must result in unintended consequences. It is surprising, then, that so much scholarship on performance measurement is directed at topics other than its politics and its consequences. This article argues for a greater focus on these neglected but important topics, and suggests a conceptual move to a ‘chain of performance measurement’, as a way of progressing research on the topic.

Performance in the public sector is an issue that is both perennial and critical. Since the 1970s interest in measuring performance has increased, alongside concerns about public sector expenditure and the advent of New Public Management (NPM). Performance measurement is high on the agenda of governments in many nations, as they seek to demonstrate that the organisations and individuals that they fund and manage, even at one or more steps removed, are doing what they are mandated to do. It is often represented in rationalist terms, as something instituted to ensure that publicly funded services are properly evaluated against a set of desired goals. It is perhaps not surprising then that many of the questions directed at performance measurement are centred on how best to measure performance (a technical issue) and how best to use it to meet organisational goals (a management issue).

A typical list of the problems related to performance measurement and the (at least implied) solutions to these are shown in . Rather than focus on these ‘usual suspects’ of performance measurement, this paper highlights its political dimensions and its consequences for individuals and for institutions. It argues that a new approach is needed to understand performance measurement, which explicitly recognises its political aspects (who decides?) and its consequences (who wins and loses?). The paper presents a framework that contrasts two alternative views — one rational and one realistic — as a series of links in a chain of performance measurement. The claim is that this chain provides some much needed analytical purchase for grasping the dynamics of performance measurement which are often overlooked.

Table 1 Problems and solutions of performance measurement.

Most of the literature on performance measurement lacks adequate conceptualization, little of it recognises the complexity of it within a public sector context, and even less provides an informed critique of it (CitationJackson, 2011). Some have focused less on the technical concerns and more on how performance measurement can be used as a mechanism of political discipline (e.g. CitationMoynihan, 2008; Radin, 2006). However, positive views of why it is needed or how it should be done prevail. This introduction and the other papers in this volume instead begin from a different set of questions: Why and when are performance measures developed and promoted? Why are performance measures distorted or resisted? Who initiates, uses, and challenges them? Who wins and who loses when they are published? (CitationJohnsen, 2005). In a similar vein, CitationPollitt (1987) claims that a more pertinent question than whether performance measurement works, is what is it for? In listing 10 possible purposes, he then moves on to the more political question of who is it for?

Such questions are about the location and use of power — put bluntly, an examination of who controls the creation and application of performance measurement systems. Issues of interests and power take the conversation into the realm of institutional theory, which opens up topics such as whether performance measurement is used as a tool to cement hierarchy, or as an instrument of self-examination for individuals and organisations, or a device for maintaining (centralised) control while decentralising responsibility (CitationCarter, Klein, & Day, 1992). To this can be added considerations of the structures of public bureaucracies and their own struggle for survival amidst a set of unique conditions that connect politicians, interest groups and bureaucrats (see: CitationMoe, 1990a). These questions of power extend to an investigation of the consequences of performance measures for the institutions and organisations that create and implement them, and for the organisations, programmes and individuals that are measured by them: Who benefits from their introduction? Who has a voice in their structure and content? Who is the most effected by the consequences — both intended and unintended, and desirable and undesirable?

Performance measurement is conceived of here as a social structure which arises from the interaction of institutional rules and individual responses to these rules. In other words, it is not simply about a simple production model, but about institutions, individuals and their interactions. This social structure is elaborated as a chain of performance measurement — a set of interactions that have a set of outputs and consequences, which generate a set of corrections in line with unanticipated and undesirable effects. Examining the social structure of performance measurement through this chain, places its politics and consequences at front and centre.

This paper attempts to redress the balance of the managerial and technical focus that has often dominated this topic, by beginning with an examination of why performance measurement has come to be so important for governments and public organisations. It then outlines its explicit and implicit purposes and the fundamental assumptions underpinning the performance movement, including the importance of rationality. The problems, paradoxes and consequences of performance measurement are described, and then two contrasting versions of a chain of performance measurement (one rational-technical and one realistic-political) are presented. The paper concludes by claiming that this heuristic device can be used to disclose performance measurement's inherently political nature and uncover its numerous consequences. The papers contributed to this volume are then briefly introduced.

2 Why performance measurement?

Why has performance measurement apparently become more important for governments and public sector organisations? The escalation of performance measurement in the public sector beginning in the 1970s, is often associated with economic decline, increased international competition and a new set of objectives related to cutting budgets and increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of public bureaucracies. A crucial focus of New Public Management or NPM (as the resulting changes came to be called) was a shift to regarding efficiency as the most important goal in the public sector. Beginning in the 1980s, NPM came to be seen as the solution to the budgetary challenges facing all sectors in many different countries (developed and developing), and at all levels of government. With its basis in both scientific management ideas and transaction cost economics, NPM was meant to be a politically neutral, rational means for governing.

CitationHood's (1991) classic statement of NPM, describes it as containing a number of doctrinal components, including hands on professional management, explicit standards and measures of performance, and greater emphasis on output controls. Performance measurement was (and is) a central plank of NPM reforms, with its focus on planning, targets, outputs and a tighter oversight and control of the achievements of public sector organisations. NPM supported a new belief that previous problems could be avoided if there was more measurement and more management.

While the notion of measuring the performance of the public sector was certainly around before NPM, its advent narrowed the focus of performance to a consideration of results, with less consideration for how these are achieved (CitationVan Dooren, Bouckaert, & Halligan, 2010). NPM's focus on frugality and concerns about waste, money and time, outputs and tight control, potentially diminishes the attention paid to other values such as honesty and security, for example (CitationHood, 1991). In general, scholars argue that performance measurement in the public sector was not completely new, but it did increase markedly with the emphasis on public management reform in many countries (CitationPollitt & Bouckaert, 2011): As a result, it is now more extensive, more intensive, and more external in its focus.

From a different perspective, CitationRadin (2006) argues that performance measurement has become so ubiquitous, because of citizens’ unwillingness to accept without question that institutions are performing as they should. Citizens are concerned about the expenditure of public sector funds and sceptical about how limited resources are allocated, worried by programme decisions that they do not agree with, and the unresponsiveness or lack of adaptability of organisations to their concerns. A growing interest in client and citizen engagement in public services, including in regard to the accountability of these services (CitationDamgaard & Lewis, 2014) adds to why citizens’ interest in performance measurement has grown.

In reviewing the performance movement over the 20th century, CitationVan Dooren et al. (2010) argue that its political nature has not changed dramatically over time, even though there might be a different impetus behind each ‘wave’. Others have claimed that performance measures became increasingly fashionable because, in theory, they provide the opportunity for government to retain firm control over departments by using a hands-off strategy (CitationCarter, 1989). A comparative study of several European countries, found that Finland, the Netherlands, Sweden and the UK (United Kingdom) were all doing more performance measurement (CitationPollitt, 2006), and that these measures were most often used by managers, not by politicians, and not by people further down the hierarchy.

NPM has been equated with both an acceleration of performance measurement, and a re-conception of it in terms of efficiency, economy and effectiveness rather than less easily measurable aspects of performance. This in itself is a clear sign of a power struggle between the managerial elite and the professional elite, with the former trying to redefine priorities (CitationBrignall & Modell, 2000). Viewing performance measurement as a mechanism of control may be at odds with the widespread view that it is merely about increasing economic efficiency (CitationSmith, 1995), but that is the starting point here.

3 Explicit and implicit purposes

On paper, the explicit purpose behind performance measurement is to improve performance. Beyond that deceptively simple starting point, there are many different reasons why it might be done. It may be for the purposes of evaluation, to discover if a programme is doing what it is supposed to do. It might be used in order to control the performance of those working in a programme or service of interest. It might also be simply a means of controlling the budget for a particular area, or determining how much money is being spent to achieve some desired output. It might even be a means of driving centrally determined goals and priorities. Sometimes performance measurement is undertaken in order to eliminate a programme, sometimes it is used to support a new direction, and sometimes it is about maximising returns on taxes and accountability to the public (CitationRadin, 2006). Amongst the many different reasons why public managers measure performance, CitationBehn (2003) has listed eight — to evaluate, control, budget, motivate, promote, celebrate, learn, and improve. Regardless of which of these is seen to be the central purpose, the issue of control (political and managerial) of public sector organisations is lurking in the background.

As scholars of politics know, the important questions are about who gets what, when, and how (CitationLaswell, 1936). Since performance measurement is a means for managing work, it provides the potential for some actors to enhance their power. The choice of ‘what is to be done’ comes before any administrative action, so it is pertinent to ask: Who decides what is to be done? More specifically, who decides that performance should be measured? It follows that a subtext of the performance movement is a concern about control (CitationRadin, 2006), and this can be seen in both western democracies and countries such as China: Performance measurement is used as a mechanism of political discipline by superordinate governments to change the behaviour of lower-level governments in the US, the UK, and the EU (CitationBertelli & John, 2010). A 1995 promulgation in China forced local level officials to concentrate their efforts on the central goals of the Party (CitationGao, 2009). Jie Gao contrasts this with the concerns of western democracies, which have instead focused on goals related to customer-orientation, efficiency, and effectiveness.

However, it should be remembered that public sector managers in western democracies rarely have much freedom to choose their own performance measures (CitationBehn, 2003). Performance measurement in China clearly demonstrates that the users of performance measurement accrue significant political benefits (CitationGao, 2009). But this is by no means confined to non-Western states — although it might be far more subtle and contested in Western democracies. The ‘targets and terror’ approach taken in England to improve the performance of the National Health Service, for example (CitationBevan & Hood, 2006), represent a similar, if more flexible and forgiving, approach to centrally driven target setting.

Some purposes of performance measurement have received much more political and organisational support than others — most notably, NPM schemes which emphasise economy and efficiency (CitationPollitt, 1987). This can be at the expense of achieving other objectives such as effectiveness, professional development and collegiality. CitationPollitt (1987) identifies the specifically political purposes and consequences surrounding performance measurement. His review of the politics of purposes behind measurement, demonstrates that the implementation of such schemes become more overtly political the more they are compulsory, the more they are focused on individuals, and the more that they are based on extrinsic incentives.

The institutional approach to the topic of performance measurement by CitationBrignall and Modell (2000) highlights the intensely political nature of decision-making in public sector organisations, and shows the need to go beyond the assumptions underpinning much of the literature on performance measurement. Their analysis demonstrates the different interests and values represented by funding bodies, professional service providers, and purchasers of public services. The significant questions about performance measurement are not technical but political, such as who decides on the measures and how they are linked to an organization's structure and functioning. Multiple stakeholders inside and outside compete to set performance measures that will advance their own interests (CitationKanter & Summers, 1987). Despite the explicit purpose of improvement, it is clear that the implicit purpose is control and that this is contested.

A parallel to this can be found in research on the politics of bureaucratic structure more generally. Political institutions are the structural means by which those in power pursue their interests, at the expense of others (CitationMoe, 1990b). Hence public bureaucracies, whether the performance measurement criteria are externally or internally devised, are institutions of coercion and redistribution: The structural choices made in their creation are implicitly linked to the need of governments to control them, while providing them with some autonomy. If these organisations are also the creators of (their own or others) performance measures, their control is explicitly observable in the decisions they make about which data to collect.

Some claim that performance measurement has become an end in itself, its main purpose being to generate measures (CitationSchick, 2001). It might be the case that performance measurement is symbolic only, undertaken as a goal in itself to indicate policy and organisational rationality. However, the mere existence of performance measures will have an impact on how people approach their work, assuming they are aware of them, and that they are seen to be taken seriously by those at the top of the hierarchy. This is an important point, because it leads to the conclusion that control is sometimes exercised by the simple act of establishment of such measures, regardless of whether and how they are used to manage organisations from above or from within.

4 Fundamental assumptions

“…operations research, linear programming, and statistical decision making, all…foster the idea that if progress towards goals can be measured, efforts and resources can be more rationally managed” (CitationRidgway, 1956: 240).

The influence of rationality on theories of policy-making is widespread, leading to mechanistic views of it as a straightforward search for the optimal solution to societal problems (e.g. CitationEaston, 1965). Affairs should be conducted through the solving of problems, as engineers do, by applying the appropriate techniques.

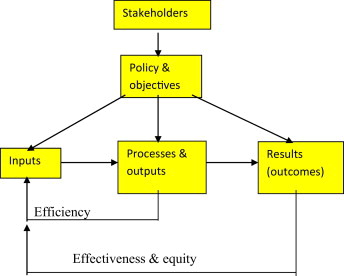

The influential literatures behind performance measurement — principal/agent separation, and the public choice school — have buttressed the rise of measurement as a necessary means for ensuring that technical and allocative inefficiencies are minimised (CitationJackson, 2011). When deciding upon what constitutes performance, and how it should be measured, a basic production model is generally used. This follows an engineering approach where inputs are transformed into outputs. Using this as a foundation, a performance model can be represented quite simply, flowing from inputs, through processes and outputs, to outcomes (see ). To make this model more aligned with the concerns of the public sector, rather than the production of some commodity, a set of directions from stakeholders flowing into policy making and objective setting, can be added.

Fig. 1 A simple performance model (from: CitationJohnsen, 2005).

The three boxes from inputs to results, shown in this fairly typical performance model, are utilised in calculating the measures of performance shown — efficiency (the ratio of processes and outputs to inputs), effectiveness (outcomes to inputs), and equity (distribution of outcomes across different individuals and groups in relation to inputs). Such models, of course, ignore such things as the uncertainty of policy and objectives, and the often widely differing stakeholder views.

This model demonstrates that performance measurement is tied to the notion of rationality with efficiency as a centrally important concept. A rational view of the policy process severely underestimates the messiness of its reality, and this is also the case for measuring performance. It relies on a clear understanding of the policy objectives of a programme; otherwise the measurement is not meaningful. Yet this is rarely the situation. The assumption of clear goals is at odds with the reality that public sector goals are, in fact, ambiguous, multiple, complex and frequently conflicting with each other (CitationJackson, 2011). Multiple stakeholders all have their own definition of performance which reflects their own interests. Uncertainty and ambiguity are well known in political science yet the impact of these on performance measurement in terms of unforeseeable consequences is not well developed (CitationJohnsen, 2005).

The performance movement is also founded on a series of rarely articulated and naïve assumptions about information and its use. These include that the information needed to assess performance is already available and it is neutral and value free, that it is clear what is being measured because the goals are clear, that simple cause–effect relationships of interventions can be defined, that baseline information is available, and that activities can actually be measured and quantified (CitationRadin, 2006).

Behind a rational view of performance measurement is a view of organisations as impersonal instruments guided by managers, rather than as temporary alliances of separate groups, each interpreting the organization's purpose differently (CitationKanter & Summers, 1987). In reality, organisations are complex entities with many goals that can be inconsistent, contradictory or incoherent, and it is often unclear at what level or with respect to what units the attainment of goals should be measured. Further, political bureaucracies face specific constraints in this regard — governments want their organisations to be effective and controllable, but neither of these is entirely achievable because these organisations exercise public authority and face political uncertainty (CitationMoe, 1990b).

The assumptions about information and rationality listed above are unrealistic: Politics, organisations and interests cannot be removed from performance measurement. Information is not value-free and there are limits to what information can be found and used. Most importantly, information is a resource that is intertwined with ideologies and interests that will seek to use it towards their own ends (CitationWeiss, 1983). As is very clear in relation to evidence based policy, ‘evidence’ is not a sufficient condition for winning a policy argument — and it is impossible to understand policy-making if it is assumed to be a non-political process (CitationLewis, 2003). To see performance measurement as somehow standing outside politics, is unrealistic. In reality, it matters a great deal who wants the information, and what their agendas are. The whole process is framed by those with power enough to structure what is seen to be in scope and what is not (CitationLukes, 2005).

Institutional theory adds the (typically absent or downplayed) interests and power of different stakeholders to an organisational analysis of performance measurement (CitationBrignall & Modell, 2000). These authors argue that institutional constraints such as dependence on a particular constituency, coexist with intentional choices and might produce organisational paradoxes. De-coupling is a means for dealing with conflicting institutional pressures, and in regard to performance measurement, it implies that inspection, evaluation and control activities are minimised, rather than integrated and linked to strategic objectives (CitationMeyer & Rowan, 1977). Alternatively, relatively crude controls de-coupled from the operating environment might allow for different stakeholder demands to be met (CitationAbernethy & Chua, 1996).

A final important assumption related to performance measurement is that it is possible to actually measure the outputs or outcomes of interest. A performance indicator is an estimate of something which cannot be measured directly, so good indicators are unbiased (or not very biased) estimates. In other words, performance measurement assumes that the indicators used do actually represent, at least with some degree of validity, the result of interest (CitationBevan & Hood, 2006). This is rather a large assumption in practice. It is simply noted as an addendum to this discussion, ahead of a consideration of performance measurement's various problems, paradoxes and consequences in the next section.

5 Problems, paradoxes and consequences

In a recent review by CitationLowe (2013), he notes that studies that report on the many problems with performance measurement are manifold, yet these problems are generally treated as technical obstacles of either measurement or management that can be overcome. The idea that they cannot be solved because they are intrinsic to performance measurement itself is rarely raised. Lowe argues that a focus on outcomes distorts the priorities and practices of those tasked with delivering interventions and (paradoxically) produces worse outcomes for those who are meant to benefit from them.

As early as the mid-1950s, the dysfunctional consequences of performance measurement were described (CitationRidgway, 1956). These include that single measures motivate individuals to behave in ways that are wasteful and detrimental to the goals espoused, while multiple measures lead to trade-offs between criteria and objectives that may be contradictory, and composite measures can cause tension, role and value conflicts. Ridgway concludes that quantitative performance measures (single, multiple or composite) have undesirable consequences for overall organisational performance.

Measurement is assumed to change behaviour, and there will be some gaming in any system (CitationBevan & Hood, 2006). While ‘gaming’ suggests consciously bad behaviour, this is not always the case. It may be a very deliberate choice, but it may simply be a means for meeting the required targets in difficult circumstances. Some of the things that induce gaming are easy to observe, if the emphasis is on understanding how people react to targets, as CitationBevan and Hood (2006) have done. These include the ratchet effect (a disincentive to perform above the set target for fear it will be raised), the threshold effect (those already exceeding the target have no incentive to keep over performing), output distortion (people only do what is measured, even if something else is more effective). The topic of gaming leads into the whole topic of individuals’ behaviour in the face of measurement.

As soon as performance measures are put into place, people begin to change what they do. If individuals are aware that the data collected will actually be used in some way that affects their work, particularly in controlling how they work, then they will surely react. People understand (or at least think that they understand) what the measures are, and realise they have to try to meet them. Whether the measures are consciously integrated or not, and whether individuals agree with them or not, makes little difference. Everyone will be measured against the standards, regardless of their personal knowledge and acceptance of the measures. It does hot help of course that rewards are often provided for behaviour that is not what was desired (such as rewarding individual effort and hitting set and visible targets when what is actually hoped for is teamwork and creativity) (CitationKerr, 1995).

As many have observed, apparently rational and evidence-based projects can produce paradoxes and unintended effects (CitationHood, Margetts, & 6, 2010). Three paradoxes of performance — ambiguous rhetoric turned into formal processes, unmeasurable outcomes, and criticism of officials and professionals while relying on them to deliver — are identified by CitationRadin (2006) as contributing to the complexity of performance measurement.

Performance measurement has been shown to have numerous unintended consequences that negatively influence performance and there are several aspects to this. First, there has been an explosion of measures and organisations that do the measuring, so many resources are now being expended on this and one consequence of this has been an increase in bureaucratization (CitationVan Thiel & Leeuw, 2002). Second, no matter how well intentioned measurement is, it will inevitably have unintended consequences. CitationSmith (1995) described eight unintended and undesirable consequences of publishing performance data in the public sector. These are tunnel vision (focusing on measures to the exclusion of other important aspects), suboptimization (pursuit of local objectives at the expense of organisational objectives), myopia (pursuit of short term targets at the expense of long term objectives), measure fixation (an emphasis on measures rather than the underlying objective), misrepresentation (manipulation of data), misinterpretation (the data is interpreted incorrectly), gaming (manipulation of behaviour) and ossification (rigid measures inhibit innovation).

It is evident that when a performance measurement system is put into place, some of the resulting consequences will be things that were expected to happen, but many of them will not. The unintended (and undesirable) consequences of measurement include such things as cheating, bribery, and ‘teaching to the test’, over and under reporting in order to look good, incentives to not disclose problems, creaming off the easy to achieve targets (and neglect of the hard cases), an inflation of quantity and a lowering of quality, and a raft of false economies (CitationGrizzle, 2002). Empirical examinations of public policy cases show that there is no such thing as a single law of unintended consequences (CitationHood et al., 2010), despite the existence of a common aspiration of more effective control of social outcomes.

In summary, performance measurement is likely to have a series of unintended consequences in addition to the intended consequence of securing control (CitationSmith, 1995). The problems generated by it are intrinsic to it. They are caused by the application of simplistic measures and systems that fail to recognise the complexity and the dynamic reality of organisations and the individuals working within them, who will react to measures in a variety of ways. There are many reasons why performance measurement may not be successful, including human behaviour, the nature of government agencies as institutions, and the assumption that studying the past is a good way to navigate the future (CitationHalchmi, 2005). Some unintended side effects are no doubt unavoidable in any administrative reform, because of the limits of human knowledge and the high dynamic complexity of human organisations as well as the inherent difficulties of experimentation in social institutions (CitationHood & Peters, 2004).

6 The chain of performance measurement

The performance movement envisages the managerial process as a series of steps from identifying organisational objectives to developing indicators to reflect these objectives, to targets set in line with the indicators, to action chosen in order to achieve the targets, to monitoring of the targets and if there is divergence, the setting of new targets and different actions (CitationSmith, 1995). Such a view is clearly mechanical and unlike the actual situation in organisations populated by networks of intelligent humans who can anticipate the actions of the controllers and take action to frustrate the controllers’ wishes. Starting by envisioning it a set of links in the chain of performance measurement has merit: The chain begins with context (social, economic, and political) and then explicates a series of links that reflect a managerial cybernetics approach (CitationBeer, 1966) — from policy and strategy setting, to deciding on criteria to measure what is valued, to communication of measurement rules, to the understandings of what is being measured and why, to responses based on those understandings — and ends with what is actually produced and the consequences of this.

However, what is needed in addition to this is a counterpoint treatment of the topic that reaches beyond rationality. One useful addition to a focus on organisational performance (which prioritises efficiency through targets, indicators and measures) and technological performance (enhancing effectiveness through the use of technological advances), is cultural performance. This refers to the constitution of meaning and affirmation of values, which is achieved through enactments of social traditions (CitationMcKenzie, 2001).

Considering the meanings and interactions of performance, leads to contemplation of the insights that can be gleaned from the psychological literature on the impact of accountability on individual thought, feeling and action. This highlights the fact that “each party to the accountability relationship learns to anticipate the reactions of the other” (CitationLerner & Tetlock, 1999: 256). Accountability can then be seen in terms of manipulations and their effects on individuals who expect their performance will be assessed and evaluated, and that they might have to explain their performance. The requirement to account for actions shapes what is going on inside individuals’ heads, and sets up value and meaning systems.

To focus on individuals and the meanings they derive from specific interactions related to performance is not to deny rationality: People gather information on “what activities are rewarded, and then seek to do (or at least pretend to do) those things, often to the virtual exclusion of activities not rewarded.” (CitationKerr, 1995: 7). Even where performance measures are put in place purely for information purposes, they are likely to be interpreted as definitions of which aspects of the job are important, and so they have important consequences for motivation and behaviour (CitationRidgway, 1956). But the impact of performance measurement frameworks on individuals relates to both their own (rational) interpretations of what this means for their work, and their (value and meaning based) reactions to these requirements.

Measures, once introduced, take on a life of their own. Even if measures are not specifically linked to targets, rewards and punishment, they are communicated, discussed and are likely to effect behaviour to some extent — both positively and negatively. People and organisations respond in line with the signals they receive about what is measured, in both desirable and undesirable directions, and no doubt more immediately and more intensively if the incentives are very strong. The array of subversive effects resulting from measurement was touched on briefly earlier in this paper.

Here the main point is to consider performance measurement systems as social structures of interaction between individuals and institutions. To begin, three scholars provide helpful insights for performance measurement, although none of them specifically wrote about it. They were each concerned with social problems, and they are discussed in turn: Robert Merton (unanticipated consequences), Charles Tilly (the invisible elbow), and Gary Fine (the chaining of social problems).

The concerns of Robert Merton started to figure in academic writing about public management reforms in the late 1990s, on the ironies of social intervention and paradoxes and surprises related to reform (CitationHood & Peters, 2004). As Hood and Peters noted, Merton's analysis of the unintended consequences of human action, along with studies of the discontinuities and trend reversals coming from the study of complex systems, have begun to contribute to accounts of paradox and surprise in institutional interventions. CitationSieber (1981) developed the Mertonian approach by identifying a range of mechanisms that can unintendedly produce the opposite of the effect desired by their architect. Recent NPM scholarship has started to produce neo-Mertonian or neo-Sieberian analyses of the process of institutional reform (CitationHood & Peters, 2004), and this provides the inspiration for establishing a chain of performance measurement.

CitationMerton (1936) delineated how purposive actions fail to produce what they are expected to. The consequences of action result from an interplay of the action and the situation. Purposive action involves motives and choice, but not always clear aims (and not necessarily rationality of aims). There are clearly problems, then, of causality and knowing what the purpose is. There are also limitations to what can be anticipated to result from actions, because of the bounded rationality of humans.

Four causes of unanticipated consequences were described by Merton: Ignorance of facts, error in the appraisal of facts, interests blinding people to risks, and self-fulfilling prophecies. Wrong appraisals of a situation are common, as are wrong predictions, the selection of wrong actions, and the faulty execution of a chosen action. Humans rely on habits (what worked before), and neglect important elements of the problem. There is a tendency to satisfy immediate interests and neglect other longer term consequences, and of course, choices are not disinterested, but based on a specific set of values. Activities set off processes that have far reaching changes (which are not limited to the specific area intended), and predictions themselves can become a new element in the situation, changing the set of things that have impact (CitationMerton, 1936).

Moving on from unanticipated consequences to incessant error correction, it is useful to remember that people instantaneously recognise the effects of what they are doing, and they constantly adjust to the situation as it unfolds, in the face of things that were not expected to happen. CitationTilly (1996) describes how all actions lead to some recognition of more problems, which those confronted with them deal with through a series of improvised adjustments. He suggests that Merton told only half the story — making the case for why purposive action regularly generates unanticipated consequences, but not going on to suggest that this action produces social structure. Tilly does just this, arguing that the consequences of all social interaction pass through powerful systematic constraints, which are created by the impact of cultures and relationships. There is, then, a great need for the examination of errors, their consequences, and their rectification — what he refers to as incessant error correction (or the invisible elbow).

CitationFine (2006) similarly notes a kind of path dependency of social problems, where consequences lead to more problems and new solutions being put into place. This generates a chain of social problems, and sets the term for later problems and constrains the options based on earlier decisions. The consequences of action result from an interplay of the action and the situation. And in line with Tilly, he notes the constant need to adjust and correct small mistakes, which are all based on the accumulation of what has happened before (culture) and social relations and interactions.

The unanticipated consequences of purposive action, the constant error correcting that occurs as events play out, and the chaining of social problems which generates a social system of opportunities and constraints, form the basis of the chain of performance measurement. To understand its politics and its consequences, it helps to see performance measurement as a set of interactions between individuals and institutions which yield a set of consequences, leads to a set of corrections of the unanticipated and undesirable effects, and generates a social structure of performance measurement.

The chain of performance measurement is as follows: Within the extant social, economic, and political context, ‘the measurers’ (governments and organisations) set policy and strategy, make decisions about what is valued, create measurement criteria that attempt to capture what is valued, and make a set of system rules that attempt to measure what is valued. These are then communicated to ‘the measured’ (organisations and individuals), who come to understandings of what is being measured and why, from a variety of sources. These understandings are made up of beliefs, perceptions and knowledge of the performance measurement system. ‘The measured’ then respond to the signals received based on those understandings. Both the measurers and the measured (governments, organisations, individuals) then contribute to outputs, based on their understandings, and their actions have a series of consequences.

The social structural view of the links in this chain provided up to this point, can be bolstered by a connection here to political institutional concerns. The institutional perspective of CitationMoe (1990a, 1990b) suggests that public bureaucracies will shape the incentives and opportunities of individual actors at each link in the chain, through the formal structures and rules and the available resources. At least some of these organisations are responsible for deciding upon measures for their own and other organisations (once political or other actors have decreed that measurement will be undertaken — and even here they will likely have had input) and all of them are responsible for implementing them internally. So there is clearly scope for measurement to be directed towards an organization's own political purposes — shoring up support, keeping important constituents happy, avoiding intrusion, using measures that are not too resource or time intensive, and so on, as well as the practice of de-coupling the measures or using them purely for ceremonial purposes while the organisation carries on with its own agenda.

Actors are able to game any element of the chain of performance measurement — from attempts to make the structures of political bureaucracies more accommodating to particular views and interests, and influencing policy and strategy, right through to how the consequences (desirable and undesirable) are dealt with. As CitationMoe (1990a: 144) argued: “Like groups and politicians, bureaucrats cannot afford to concern themselves solely with technical matters. They must take action to reduce their political uncertainty”. This is a useful reminder the organisations involved in constructing and implementing measurement are not (only) rational instruments.

presents two contrasting versions of this chain — one that is aligned with the rationalist approach that underpins the very notion of performance measurement, and suggests an ideal-type rational bureaucracy. The other incorporates the preceding discussion of its more political purposes, and suggests a political bureaucracy. These are shown as a dichotomy but in reality they represent two ends of a spectrum of more or less rational or political positions. Some cases might fit more wholly under the first alternative — for example in simple situations with clear criteria and measures. Many more are likely to have aspects that are political, for example, a clear statement of policy can easily lead to a huge range of understandings about what the rules should be and what should be counted. The value of the two versions is that it takes the discussion beyond what is often glossed over, into a more sophisticated set of concerns about who is making the decisions, on what basis, using what structures, and why. Importantly, examining each of the links in this chain also focuses attention on the many steps being taken by both the measurers and the measured, and the fact that performance measurement relies on individuals interacting within these steps.

Table 2 Two alternative versions of the chain of performance measurement.

7 Conclusions and contributions

To understand the politics and consequences of performance measurement, there is a need to understand and examine all the links in both versions of the performance measurement chain outlined in this paper. If the whole chain is considered, it is possible to better analyse why performance is being measured, how and by whom, what is seen to be of value, what is being gained and what is being lost, and who is benefitting and losing from this.

The dominant managerial and technical approaches to performance measurement deny its politics and its distributional consequences. Yet these are clearly embedded within performance measurement which ultimately is a form of directing the behaviour of organisations and individuals towards desired ends. Using the chain and its two alternative versions as a heuristic should help uncover power, purposes, and to what extent rationality is holding sway in policy setting and measure making. If nothing else, considering the links in the chain provides a reminder that performance measurement works through social and political rather than mechanical channels and hence has winners and losers and is extremely consequential. The contributed papers to this volume build on this framework in different ways using examples from a variety of national contexts. Collectively, they represent a compelling set of conceptual and empirical advances on this important topic.

Peter Triantafillou's contribution explores the responses of Danish universities to a national audit that criticised them for the low number of hours of teaching that students were receiving. His paper demonstrates how a few simple indicators were used to gain traction with policy makers and how the universities themselves then took on more monitoring and assessment (self-governance) as a consequence.

Steven Putansu's paper examines some of the US government's cross-cutting priority goals, directed at complex policy issues — climate change, cybersecurity and STEM education. He concludes that there is substantial adherence to a rational-scientific approach, but there is also potential for directed collaboration to engender a more realistic-political approach to performance measurement, and allow it to become more critical, iterative and reflective.

Jie Gao's study of target setting in China describes how centrally determined targets in that nation cascade down through local governments to individual townships. A blend of political purpose and rationality is apparent in the targets. Progress is achieved, but the consequences of failure to meet the targets are harsh and have led to substantial gaming. She concludes that performance measurement can only do so much towards reforming China.

Yijia Jing, Yangyang Cui and Danyao Li develop a regime-centred framework to understand the political nature of performance measurement, and then apply this to the adoption and functioning of performance measurement in China. They argue that it has played a major role in state building and governance in China's reform era, and also point to its potentially empowering effects, while emphasising the importance of national political context.

Paul Henman and Alison Gable focus on street-level professionals and how performance measurement is changing the role and conduct of professionals. They examine Australia's educational performance measurement in schools and point to a range of problems in regard to its goals, and its measures, and how it is used to govern the conduct of teachers. They conclude that performance measurement recasts professional discretion in subtle ways.

Finally, Peter Woelert makes a conceptual contribution based on the logic of escalation of performance measurement — where strong reliance on quantified measures leads to measurement becoming more technical, costly and politically controlled. He applies this to the higher education system in Australia, and argues that multiple changes to its research assessment system have not resulted in the promised outcome of less government control.

Acknowledgements

This research is being supported by an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship. The Melbourne School of Government generously provided funding for a one day workshop on this topic. Thanks to all the workshop participants for the interesting discussions, and to the journal's anonymous reviewers for their useful comments.

References

- M.A. Abernethy , W.F. Chua . A field study of control systems ‘redesign’: The impact of institutional processes on strategic choice. Contemporary Accounting Research. 13 1996; 569–606.

- S. Beer . Decision and control: The meaning of operational research and management cybernetics. 1966; Wiley: Chichester

- R. Behn . Why measure performance? Different purposes require different measures. Public Administration Review. 63(5): 2003; 586–606.

- A.M. Bertelli , P. John . Performance measurement as a political discipline mechanism. University of Southern California Law School, Law and Economics Working Paper Series No. 112. 2010; Berkeley Electronic Press. http://law.bepress.com/usclwps-lewps/art112 .

- G. Bevan , C. Hood . What's measured is what matters: Targets and gaming in the English public health care system. Public Administration. 84(3): 2006; 517–538.

- S. Brignall , S. Modell . An institutional perspective on performance measurement and management in the ‘new public sector’. Management Accounting Review. 11 2000; 281–306.

- N. Carter . Performance indicators: ‘Backseat driving’ or ‘hands off’ control?. Policy and Politics. 17(2): 1989; 131–138.

- N. Carter , R. Klein , P. Day . How organisations measure success: The use of performance indicators in government. 1992; Routledge: London and New York

- B. Damgaard , J.M. Lewis . Accountability and citizen participation. M. Bovens , R. Goodin , T. Schillemans . Oxford handbook of public accountability. 2014; Oxford University Press: Oxford 258–272.

- D. Easton . A systems analysis of political life. 1965; Wiley: New York

- G.A. Fine . The chaining of social problems: Solutions and unintended consequences in the age of betrayal. Social Problems. 53(1): 2006; 3–17.

- J. Gao . Governing by goals and numbers: A case study in the use of performance measurement to build state capacity in China. Public Administration and Development. 29 2009; 21–31.

- G.A. Grizzle . Performance measurement and dysfunction: The dark side of quantifying work. Public Performance & Management Review. 25(4): 2002; 363–369.

- A. Halchmi . Performance measurement: Test the water before you dive in. International Review of Administrative Sciences. 71(2): 2005; 255–266.

- C. Hood . A public management for all seasons. Public Administration. 69(1): 1991; 3–19.

- C. Hood , H. Margetts , P. 6 . The drive to modernize. A world of surprises?. H. Margetts , P. 6 , C. Hood . Paradoxes of modernization. Unintended consequences of public policy reform. 2010; Oxford University Press: Oxford 3–16.

- C. Hood , G. Peters . The middle aging of New Public Management: Into the age of paradox. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 14(3): 2004; 267–282.

- P.M. Jackson . Governance by numbers: What have we learned over the past 30 years?. Public Money & Management. 31(1): 2011; 13–26.

- Å. Johnsen . What does 25 years of experience tell us about the state of performance measurement in public policy and management?. Public Money and Management. 25(1): 2005; 9–17.

- R.M. Kanter , D.V. Summers . “Doing well while doing good”: Dilemmas of performance measurement in non-profit organizations and the need for a multiple-constituency approach. W.W. Powell . The non-profit sector: A research handbook. 1987; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT 98–110.

- S. Kerr . An academy classic: On the folly of rewarding A, while hoping for B. Academy of Management Executive. 9(1): 1995; 7–14. first published in 1975.

- H. Laswell . Politics: Who gets what, when, how. 1936; McGraw-Hill: New York

- J.S. Lerner , P.E. Tetlock . Accounting for the effects of accountability. Psychological Bulletin. 125(2): 1999; 255–275.

- J.M. Lewis . Evidence based policy: A technocratic wish in a political world. V. Lin , B. Gibson . Evidence-based health policy: Problems and possibilities. 2003; Oxford University Press: Melbourne 250–259.

- T. Lowe . New development: The paradox of outcomes — the more we measure, the less we understand. Public Money and Management. 33(3): 2013; 213–216.

- S. Lukes . Power. A radical view. 2nd ed., 2005; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke

- J. McKenzie . Perform or else: From discipline to performance. 2001; Routledge: London

- R.K. Merton . The unanticipated consequences of purposive social action. American Sociological Review. 1 1936; 894–904.

- J.W. Meyer , B. Rowan . Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology. 83 1977; 340–363.

- T.M. Moe . The politics of structural choice: Toward a theory of public bureaucracy. O. Williamson . Organization theory: From Chester Barnard to the present and beyond. 1990; Oxford University Press: New York 116–153.

- T.M. Moe . Political institutions: The neglected side of the story. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization. 6(Special Issue): 1990; 213–253.

- D.P. Moynihan . The dynamics of performance measurement. 2008; Georgetown: Washington, DC

- C. Pollitt . The politics of performance assessment: Lessons for higher education?. Studies in Higher Education. 12(1): 1987; 87–98.

- C. Pollitt . Performance management in practice: A comparative study of executive agencies. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 16(1): 2006; 25–44.

- C. Pollitt , G. Bouckaert . Public management reform. 3rd ed., 2011; Oxford University Press: Oxford

- B.A. Radin . Challenging the performance movement: Accountability, complexity and democratic values. 2006; Georgetown University Press: Washington

- V.F. Ridgway . Dysfunctional consequences of performance measurements. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1(2): 1956; 240–247.

- A. Schick . Getting performance measures to measure up. D.W. Forsythe . Quicker, better, cheaper: Managing performance in American Government. 2001; Rockefeller Institute Press: Albany, NY

- S. Sieber . Fatal remedies. 1981; Plenum: New York

- P. Smith . On the unintended consequences of publishing performance data in the public sector. International Journal of Public Administration. 18(2–3): 1995; 277–310.

- C. Tilly . Invisible elbow. Sociological Forum. 11(4): 1996; 589–601.

- W. Van Dooren , G. Bouckaert , J. Halligan . Performance management in the public sector. 2010; Routledge: Oxon

- S. Van Thiel , F.L. Leeuw . The performance paradox in the public sector. Public Performance and Management Review. 25(3): 2002; 267–281.

- C.H. Weiss . Ideology, interests and information: The basis of policy positions. D. Callahan , B. Jennings . Ethics, the social sciences, and policy analysis. 1983; Plenum Press: New York