Abstract

Anti-corruption advocates worldwide deride “toothless” anti-corruption agencies and demand agencies “with teeth,” meaning strong law enforcement powers. However, there are drawbacks to such powers. This paper draws from the documented experiences of dozens of anti-corruption agencies worldwide to show that law enforcement powers are not determinative of agency effectiveness, nor are they always helpful. Rather, both “guard dog” agencies, which use law-enforcement powers to address crimes of corruption directly, and “watchdog” agencies, which merely uncover and report corruption issues, face unique challenges and constraints. An anti-corruption agency's powers may influence its strategic response to its operating environment, but ultimately are less critical to corruption reduction than other factors such as independence, political will, and the reliability of partner institutions.

1 Introduction

“Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission ‘Toothless’ Bulldog.” Nyoni, Mthandazo. Newsday, 4 March 2014.

“Victoria's Anti-corruption Watchdog Doesn’t Have Enough Teeth, Says Expert.” Alcorn, Gay. The Guardian, 18 September 2014.

“NAB Has Become a Toothless Body: Transparency.” Khan, Amraiz. The Nation, 9 October, 2014.

The three recent headlines reproduced above come from Zimbabwe, Australia, and Pakistan, respectively. Similar headlines have appeared in newspapers worldwide. Good governance activists everywhere deride “toothless” anti-corruption agencies and demand watchdogs “with real teeth.” But what are those teeth? And how important are they?

In common usage, an ACA with “teeth” is one with strong investigative powers, such as the ability to execute search warrants, use force, and arrest suspects. Intuitively, strong powers should make an anti-corruption agency (ACA) more effective. However, law enforcement powers are not always advantageous. In many contexts, “toothless” ACAs may be more resilient, robust, and cost-effective. This study draws from the documented experiences of dozens of ACAs worldwide, across a range of contexts, to elucidate the strengths, drawbacks, and optimal conditions for ACAs possessing strong law enforcement powers, and for those that lack them.

First, it's worth starting with the wisdom of professional dog breeders, who domesticated canine watchdogs long before governments created their namesake institutions. Traditionally, there are two distinct types of protective canines: guard dogs and watchdogs (CitationAnderson, 2011). Both use their superhuman senses to detect threats. They differ, however, in their response to danger. Watchdogs—like terriers or foxhounds—raise alarm through loud barks. They might give chase to intruders to track them, but they will flee or hide rather than fight. In contrast, guard dogs—like Rottweilers or pit bulls—pursue and engage threats, prepared to fight to the death.

Guard dogs are bigger, more tenacious, and more aggressive than watchdogs (CitationAnderson, 2011). Without question, they are more powerful. However, watchdog breeds are more popular. Their intelligence, sociability, and small size make them easier to manage. In contrast, guard dogs can be erratic and hard to handle without careful training. Homeowners must carefully consider their needs, resources, and home environment when selecting the right breed for their security.

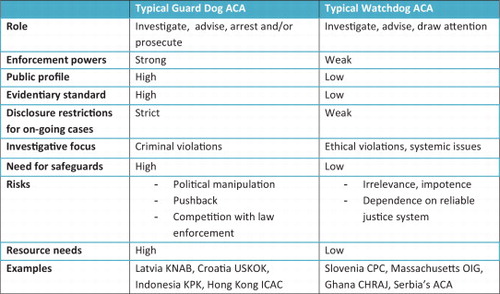

Similarly, anti-corruption authorities can be divided into “watchdog” and “guard dog” agencies, based on the strength of their investigative powers (i.e. “teeth.”) Guard dog ACAs, like Hong Kong's Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) and New York City's Department of Investigation, are law enforcement agencies with strong investigative powers. Some, like Indonesia's Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi (KPK), and Croatia's Ured za suzbijanje korupcije i organiziranog kriminaliteta (USKOK), even have prosecutorial powers. In contrast, Watchdog ACAs rely on more limited powers: collecting witness testimony, subpoenaing documents, holding public hearings, and issuing reports. Examples include Slovenia's Commission for the Prevention of Corruption (CPC), Ghana's Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice (CHRAJ), and the Office of the Inspector General of the U.S. state of Massachusetts.

Guard dog ACAs are certainly bigger, more powerful, and more threatening than watchdog agencies. But they also require more resources, face higher expectations, and are bound by more legal restrictions than watchdogs. Just as a homeowner should carefully weigh risk factors before adopting a Rottweiler, a government should make sure it has the resources, controls, and institutional support necessary before creating a guard dog ACA.

Both guard dog ACAs and watchdog ACAs can be either be docile and impotent or assertive and effective. Strong powers do not determine whether an ACA can effectively expose corruption and promote systemic reforms. A government seeking to strengthen ACA performance should consider other factors.

2 The purpose and powers of anti-corruption agencies

Anti-corruption agencies are specialized state bodies mandated to address corruption, the abuse of public office for private gain. They typically address a range of issues related to public integrity: criminal acts such as bribery, ethical violations such as conflicts of interest, and problems of systemic corruption such as regulatory capture or abuse-prone procurement processes (CitationOECD, 2013). Whatever their jurisdiction, ACAs are oversight agencies that use their powers to expose and address undue influence over state power by private interests.

ACAs proliferated worldwide in the 1990s and early 2000s, inspired by the achievements of pioneering offices like New York City's Department of Investigation (established 1873), Singapore's Corruption Practices Investigation Bureau (established 1952), and Hong Kong's ICAC (established 1974). The global anti-corruption movement that rose in the wake of the Cold War enshrined ACAs as key institutions of public integrity oversight. In the early 21st Century, most countries worldwide established or strengthened ACAs, often under international pressure.Footnote1 Advocates promoted ACAs through treaties like the 2005 United Nations Convention Against Corruption, multilateral bodies like the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and global advocacy groups like Transparency International (CitationDe Sousa, 2010).

Overall, ACAs worldwide have fallen short of high expectations. Many have been incapacitated by resource shortages, internal scandals, poor management, political co-optation, and public distrust (CitationHeilbrunn, 2004; Meagher, 2004; De Sousa, 2010). Few have achieved demonstrable results, as measured by high levels of polled public trust, high levels of case clearances or conviction rates in investigated cases, the closure of high-profile cases, or other benchmarks (CitationQuah, 2009). Generally, ACAs face a bleak paradox: those ACAs that defy the odds to become effective and independent oversight bodies become overwhelmed by fatal pushback from the powerbrokers who profit from existing corruption networks (CitationKuris, 2014). Anti-corruption experts disappointed by ACAs’ perennial underperformance have increasingly shifted attention to other approaches, such as economic and institutional reforms, local-level transparency measures, and investments into essential state functions (CitationGraycar, 2015; Hough, 2013; Kpundeh, 2004; Recanatini, 2011).

Although many ACAs have followed similar trajectories to disappointing outcomes, they have not converged in form and function. States that adopted ACAs often tailored their mandates, structures, and powers to fit local context and political interests. Once established, ACAs evolved further, through formal legal changes as well as strategic adaptations to opportunities and constraints (CitationKuris, 2014).

The CitationOECD (2013) has sorted ACAs into three basic categories: Multi-purpose Anti-Corruption Agencies, Law Enforcement Type Agencies, and Corruption Prevention Institutions. Multi-purpose ACAs, often modelled on Hong Kong's ICAC, combine investigative (sometimes prosecutorial), preventive, and/or educational functions. Law enforcement type ACAs are specialized police or prosecutorial bodies, often with extra powers and resources, mirroring elite units dedicated to other internal security challenges like organized crime, terrorism, or espionage. The category of corruption prevention institutions encompasses commissions and councils that monitor issues of public ethics and promote reforms, but lack strong investigative powers. Recent anti-corruption scholarship has tended to adopt those three categories (CitationRecanatini, 2011). However, it is worth noting that individual ACAs might defy easy categorization or evolve from one category to another. For example, Croatia consciously established USKOK as a multi-purpose ACA modelled on Hong Kong's ICAC, but the prosecutors who led and supervised it chose (evidently wisely) to run it as a specialized prosecutorial body and defer their preventive and educational responsibilities to other state institutions (CitationKuris, 2013a).

A fundamental distinction can be drawn within the OECD typology between ACAs with the powers of law enforcement (multi-purpose and law enforcement agencies) and those that lack such powers (corruption prevention institutions). Often, the latter agencies are dismissed as “toothless” for their lack of investigative powers. For example, corruption prevention institutions in South Korea and Slovenia have been dismissed as toothless (CitationKuris, 2013b; Quah, 2010). Critics argue that such agencies lack the means to pursue corruption effectively, whether or not they have the will to do so. Because “toothless” has colloquial connotations of timidity and weakness, the characterization implies that ACAs are ineffective without law enforcement powers.

Conventional wisdom holds that law enforcement agencies with strong teeth have greater freedom to operate and greater chance of success (CitationMeagher, 2004). They sit at the apex of the John Braithwaite's “enforcement pyramid” (CitationGraycar & Prenzler, 2013). This perception of pre-eminence has contributed to what one study calls the “carpet-bombing” of the multi-purpose Hong Kong model across the developing world, under Western pressure (CitationDoig, Watt, & Williams, 2005).

Despite their powers, many ACAs with law enforcement powers are ineffective, especially in countries rife with entrenched corruption and impunity. Some such ACAs have promising starts but collapse quickly under political pressure, as in Kenya (CitationKpundeh, 2004). Others are mere façades, created to satisfy domestic or foreign pressure but deprived of the resources and political will required to actually operate effectively, as in Sierra Leone and Malawi (CitationKpundeh, 2004). Others are ineffective because their work is undermined by unreliable partners in the police, judiciary, or government, as in Lithuania (CitationKuris, 2012d). Many studies have illuminated the daunting obstacles that thwart ACAs with strong teeth from achieving results (CitationDoig, Watt, & Williams, 2007; De Sousa, 2010).

In contrast, there are solely preventive institutions that are quite effective. Slovenia's CPC, relying solely on its powers of subpoena, issued damning reports that exposed entrenched corruption among the political and economic elites of a country perceived as relatively free of graft (CitationKuris, 2013b). The commission's findings sparked a nationwide protest movement that toppled the government, forced major government and opposition leaders to resign, and prompted major reforms. Temporary state commissions in the United States, such as the Commission on Government Integrity in the New York State in the early 1980s and the Ward Commission in Massachusetts in the late 1970s, uncovered expansive networks of graft that provoked public outcry and led to new laws and major institutional reforms in corruption-prone sectors like construction and public procurement (CitationSalkin & Kansler, 2011).

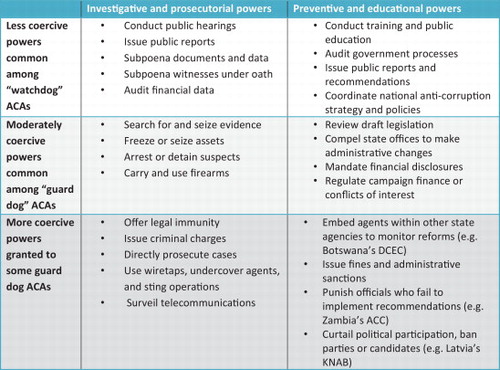

Rather than judge ACAs based on their teeth, it is more helpful to divide ACAs like their canine counterparts, between “guard dog ACAs” with strong law enforcement powers and “watchdog ACAs” that lack them. The distinction is more of a continuum than a clear division. Each ACA is endowed with a distinct toolbox of powers to carry out its investigative and/or preventive functions, framed by its mandate, institutional position, and legal context. Nevertheless, such powers fall along a rough spectrum from relatively unobtrusive tools common among watchdog ACAs, such as issuing subpoenas and conducting hearings, to potent legal powers common among guard dog ACAs such as arresting suspects, seizing evidence, and freezing assets (see ). Furthermore, some guard dog ACAs possess special powers not granted to typical law enforcement agencies, such as the ability to conduct sting operations and telecommunications surveillance or to prosecute cases directly.

3 The perks and problems of being a guard dog

Fundamentally, guard dogs ACAs are more powerful than watchdog ACAs because they possess both the watchdog ACA's investigative toolbox as well as more coercive instruments. Guard dog ACAs may act on behalf of the state to deprive suspects of liberty, property, and privacy. They may keep suspects in prison, bankrupt them through heavy fines, and strip them of their office, pension, and state privileges and entitlements. Their agents might even carry weapons and exercise force.

In principle, guard dog ACAs could operate like watchdog ACAs and reserve their police powers only for extraordinary situations. Some inspectors general within federal departments of the United States government—for example, the National Science Foundation, the Peace Corps, and Amtrak (the national railroad)—are vested with strong but rarely used law enforcement powers that include the bearing of firearms, the power to execute search warrants, and the power to make arrest (CitationGinsberg, 2014). In practice, personnel of those offices tend to partner with other law enforcement agencies when necessary, rather than bust into science labs and rail yards, guns blazing.

Generally, however, guard dog ACAs face many incentives to bare their teeth. ACA leaders have limited resources to allocate, and will naturally tend to prioritize criminal cases likely to lead to convictions, in order to demonstrate clear achievements and validate their grant of coercive powers. Domestic and international constituencies also expect to see such powers used. The law enforcement officers hired to staff guard dog ACAs are trained and conditioned to see corruption issues through the lens of criminal investigation. Even for multi-purpose ACAs with strong preventive powers, investigations and prosecutions (or the lack thereof) overshadow preventive and educational efforts, as in Latvia's Korupcijas novč ršanas un apkarošanas birojs (KNAB) and Botswana's Directorate for Corruption and Economic Crime (DCEC) (CitationKuris, 2012c, 2012d). It seems fair to assume that typical guard dog ACAs routinely pursue the criminal investigations they are empowered to undertake.

Some guard dog ACAs have used their powers effectively to help uproot corruption. New York City's Department of Investigation (DOI) has launched countless successful investigations since its creation in 1873; its recent investigation into the “Citytime” scandal uncovered a half-billion dollar fraud that led to several convictions and the recovery of nearly all lost (CitationPeters, 2014). Hong Kong's ICAC and Singapore's Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB) played key roles in transforming both cities from notoriously corruption-ridden to cities known for professional law enforcement and honest delivery of government services (de Speville, 14). The Independent Commission Against Corruption of New South Wales, Australia, exposed issues of police corruption and organized crime in the Sydney area and served as a model for similar commissions nationwide (CitationPrenzler, 2011).

However, guard dog ACAs have several shortcomings compared to watchdog ACAs, which the remainder of this section will examine in turn. In sum: (1) guard dog ACAs require substantial investments of attention and resources; (2) guard dog ACAs face unrealistically high expectations; (3) guard dog ACAs require tighter controls, which constrain their investigations and communications; (4) guard dog ACAs’ investigations are coloured by the precepts of criminal law; (5) guard dog ACAs face greater risks of political subversion or pushback; and, (6) guard dog ACAs face tensions with other government bodies, especially law enforcement partners.

Guard dog ACAs are high-maintenance. Investigations, especially those of a sophisticated crime like corruption, require investments of time, resources, and skilled staff. Those guilty of high-stakes corruption have every incentive to use their substantial resources to conceal their crimes and to hire expert legal counsel to defend themselves. Disrupting high-level corruption networks is a laborious task. Sometimes it even requires advanced technology, such as the computer forensics unit of Indonesia's KPK (CitationKuris, 2012a). Guard dog ACAs typically pay their agents relatively high salaries, because of their powers, personal risks, susceptibility to corruption, and strict ethical rules such as prohibitions on secondary employment (Citationde Speville, 2010).

To handle their caseload, guard dog ACAs tend to have large staffs. Hong Kong's ICAC has more than a thousand staffers and a sizeable budget, despite operating in a small, compact jurisdiction where the rule of law is relatively strong (CitationQuah, 2009). Singapore's CPIB and New York City's DOI have hundreds of staffers each. As staff size increases, human resource needs rise exponentially. Indonesia's KPK, with a staff of more than 800, has had to devote substantial resources to recruiting, training, and internal discipline to avoid internal scandals that could easily undercut morale and torpedo the commission's credibility (CitationBolongaita, 2010). In contrast, Slovenia's CPC, with an intimate staff of 30, could afford to take an ad hoc approach to human resources (CitationKuris, 2013b).

In many ACAs, resource constraints are compounded by a lack of budgetary independence and flexibility (CitationKpundeh, 2004). For example, Indonesia's KPK lacks its own office space, for which legislators repeatedly refused to approve funding (CitationKuris, 2012a).

Many countries cannot realistically afford to fund guard dog ACAs on their own. They require foreign assistance, which can be unreliable and hard to coordinate (CitationKpundeh, 2004). Donor programs in Uganda and Sierra Leone specifically aimed at building capacity for high-level investigations proved ineffective (CitationDoig et al., 2007). A review of intensive donor efforts to boost investigative and prosecutor capacity in Malawi found many serious impediments, from lack of forensic analytic capabilities to retention of prosecutorial staff (CitationHechler & Parkes, 2010). The more resources an ACA requires, the faster the cycle of donor fatigue sets in (CitationDoig et al., 2005).

Because of their size and perceived power, guard dog ACAs consume not only resources, but also attention. They tend to crowd out other anti-corruption efforts. CitationKpundeh (2004) argues: “[T]hey might even have a negative impact because they detract from the need for systemic reforms.”

Reformers, citizens, and international supporters often have unrealistic expectations for quick results from the guard dog ACAs they have invested with powers and resources. Taufiequrachman Ruki, the first chairman of Indonesia's KPK, said: “The hardest thing was to meet public expectations [that were] increasing every day. When I caught a governor, they said, ‘You have never caught a general.’ When I caught a general, they said, ‘You never caught a minister.’ When I caught a minister: ‘What about the president?”’ (CitationKuris, 2012a). Leaders of guard dog ACAs in Mauritius and Botswana voiced similar frustrations (CitationKuris, 2013c, 2013d). Managing constituent expectations can be one of the hardest challenges a guard dog ACA faces (Citationde Speville, 2010).

One reason that guard dog ACAs struggle to meet expectations is that they operate within a legal process deliberately constructed to make criminal investigations painstaking and inconspicuous. In liberal states, coercive state powers are bound by duties, restrictions, and oversight mechanisms, in order to protect civil rights and liberties. Depending upon the legal context in which they operate, guard dog ACAs may need to seek warrants before executing searches and arrests. Their surveillance may be subject to judicial audits and recordkeeping requirements. Their communications may be restricted by obligations to protect suspects’ privacy. They may need to make regular reports to the public or to executive, legislative, or judicial overseers. Because criminal investigations carry high stakes for those they target, the agencies who conduct them face tight constraints.

Liberal criminal justice systems guarantee defendants due process. Defendant rights and avenues of appeal can make the road to conviction long and tortuous, especially in the inflexibly formalized legal systems common among postcolonial and postcommunist states. Long legal processes replete with quirks and loopholes can produce frustrating outcomes that demoralize an ACA and erode its political and popular support. Guard dog ACAs in Botswana and Lithuania won public acclaim for arresting and charging several high-profile defendants, but lost credibility when such cases became tied up in court or resulted in unfavourable judgments based on legal technicalities (CitationKuris, 2012d, 2013d). Whether or not such judgments were sound, they contributed to public cynicism and impressions of a rigged justice system.

Perhaps the public might be more forgiving of guard dog ACAs if they saw the painstaking—sometimes heroic—work of their agents and the mountains of evidence they uncover. However, most legal systems place tight restrictions on how investigators and prosecutors can communicate throughout the legal process, to protect defendant privacy and the impartiality of the trial. Generally, suspects face no such restrictions. High-profile suspects often comment freely while ACAs stay tight-lipped through the years-long process of investigation, prosecution, and appeal. Mauritius's Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) investigated and prosecuted several high-level public officials who publicly denounced the cases as politically motivated. The ICAC struggled to address those accusations within the bounds of the law. Anil Kumar Ujoodha, the senior magistrate who led the commission, complained: “Our law is very strict [in its restrictions on] giving out any information that we encountered during the course of our investigation. It's very difficult to deal with this in some cases, because people tend to hear only one side of the story. They don’t tend to hear ICAC's side.” (CitationKuris, 2013c). Thus, even ICAC's courtroom victories failed to impress the public.

Criminal convictions have a high threshold. Prosecutors must meet a high evidentiary standard of criminal culpability, such as “proof beyond a reasonable doubt.” This rigorous burden of proof may deter guard dog ACAs from pursuing riskier cases and bias them towards cases with tangible evidence or cooperative witnesses, clear legal precedent, and allegations of crimes with easily demonstrable elements. Like the proverbial man searching for dropped car keys under a streetlamp because that's where the light is, guard dog ACAs tend to gravitate towards the most provable cases, regardless of their import. Indonesia's KPK has won a near-perfect conviction record by focusing on simple crimes like bribery for which agents could collect irrefutable evidence through telecommunications surveillance and sting operations (CitationKuris, 2012a). As important as such convictions have been, the KPK has arguably shied away from pursuing more sophisticated and higher-stakes forms of fraud.

Likewise, criminal convictions require the commission of criminal acts by identifiable culprits. Courts can only convict persons, not systems or cultures or public bodies. The orientation towards individual criminal acts and actors may cause an ACA to miss the forest for the trees, or bias it towards cases with clear wrongdoing and identifiable wrongdoers. Goran Klemenčč, a constitutional law professor and former director of Slovenia's CPC, said: “Corruption is rarely a cause; it is usually a consequence of the problems in the system. Criminal law is by its definition something that addresses the consequences, not the cause.” (CitationKuris, 2013b).

Besides logistical and legal hurdles, guard dog ACAs face two important political risks: politicization and pushback. Because guard dog ACAs are strong, governments may be tempted to pressure them to act as attack dogs against opposition politicians. ACAs in Bangladesh and Poland, among others, suffered from accusations of subservience to the interests of ruling parties (CitationHough, 2013). On the other hand, if a guard dog ACA resists political pressure, the government may respond by stripping its powers, removing its leadership, challenging it in court, reducing its funding, or curtailing its independence. Even (perhaps especially) institutions widely regarded as independent and professional are susceptible to such pushback. For example, Argentina's Anti-Corruption Office achieved successful prosecutions and high public trust before the government restructured the office to reduce its strength and independence (CitationMeagher, 2004).

Whether or not they target government leaders, criminal investigations of powerful targets are almost certain to produce pushback, ranging from passive resistance to active retaliation. Seeing their personal liberties, livelihoods, and reputations under threat, targeted individuals have great incentive to hit back with every available legal and extra-legal asset that they and their allies can draw upon (CitationKuris, 2014). Pushback can sap an ACA's morale, undermine its political support, tie up its resources, preoccupy (and personally threaten) its leadership, and tarnish its public image. Leaders of guard dog ACAs have been assassinated in Afghanistan, forced into exile from Nigeria, physically threatened in Latvia, and framed by the police in Indonesia.

On the other hand, guard dog ACAs without proper mechanisms of control and accountability may abuse their coercive powers, undermine democratic norms, and lose legitimacy. The public may fear a guard dog ACAs with concentrated power (CitationDe Sousa, 2010). For example, Malaysia's anti-corruption commission achieved an impressive record of investigative success, but at a steep cost. A 2011 royal commission found procedural lapses that led to the death of a suspect under custody, as well as a subsequent cover-up by the agency (CitationReport of the Royal Commission of Enquiry, 2011).

Finally, guard dog ACAs may also face difficulties interacting with other state bodies. Unless they work with complementary specialized law enforcement partners (such as Indonesia's anti-corruption court or Croatia's anti-corruption police bureau), guard dog ACAs must still work with other justice sector institutions that may act as veto points. Guard dog ACAs may have unclear jurisdictional boundaries, provoking a turf war or “battle of the badges” with other law enforcement agencies (CitationSalkin & Kansler, 2011). Other justice-sector partners may see guard dogs as competitors and may be resentful of the attention, resources, and privileges that such specialized forces receive. To resolve such problems, guard dog ACAs require clearly defined roles and relationships of trust with partner agencies.

The creation of guard dog ACAs may undercut public confidence in the professionalism of peer agencies. According to Drago Kos, the founding commissioner of Slovenia's CPC, Slovenian leaders decided against giving the commission police powers to avoid disturbing the balance of power within the existing justice sector or signalling distrust in existing institutions. He explained, “Giving law enforcement powers to the anti-corruption agency means you are taking something that is traditionally the domain of the police, and for that you have to have damned good reasons (CitationKuris, 2013b).”

Guard dog ACAs may also face difficulties interacting with partners outside the justice system. There is an inherent tension between the advisory roles that such agencies exercise when they coach partner agencies on ethical behaviour and corruption risk reduction and the adversarial role they play when they police the same agencies for violations. Public officers trying to implement preventive recommendations may worry that disclosing corruption risks to guard dog ACAs may invite unwanted scrutiny and open up a criminal investigation.

Despite the above catalogue of concerns, guard dog ACAs are not foreordained to fail. There are several examples of effective guard dog ACAs, even among new democracies. For example, Indonesia's KPK secured the conviction of many high-level politicians, spurred preventive reforms across government, achieved high public approval ratings, and survived a series of politically-motivated threats to both the institution and its leadership (CitationSchütte, 2012; Kuris, 2012a, 2012b). Latvia's KNAB exposed networks of corruption that galvanized a popular movement against local “oligarchs” that transformed the political landscape and ushered in substantial reforms (CitationKuris, 2012c). Croatia's USKOK successful prosecuted a former prime minister as well as dozens of other high-level leaders, played a leading role in quelling doubts about corruption that had stalled Croatia's accession to the European Union, and ultimately became one of the nascent democracy's most trusted institutions (CitationKuris, 2013a).

As demonstrated in the case studies referenced above, Indonesia, Latvia, and Croatia did not escape the shortcomings inherent to guard dog ACAs, but rather anticipated and managed them. The KPK, KNAB, and USKOK were provided ample budgets and skilled staff, supplemented by targeted foreign assistance. Those three agencies managed public expectations by demonstrating early wins and building collaborative relationships with media and civil society. They had highly-trained investigators and prosecutors who were able to navigate legal hurdles, and they depended upon the cooperation of independent and respected judges (such as those of Indonesia's specialized anti-corruption court). They worked hard to demonstrate their independence and project transparency and accountability, avoiding or overcoming pushback and political subversion by attracting overwhelming public and international support. They tried to target their investigations to expose systemic corruption risks, often in coordination with preventive and educational efforts. And they built partnerships with other justice-sector agencies and government offices.

Yet, two out of three of those agencies (KPK and KNAB) still struggle against political pushback and internal strife in their second decade of operation. Guard dog ACAs, even those that are effective, require constant vigilance and attention from strong leaders and partners to avoid backsliding.

4 How do watchdog ACAs compare?

Watchdog ACAs generally have many of the investigative and preventive functions as guard dog ACAs, but they lack law enforcement powers (see for a comparison). When they detect evidence of wrongdoing, they can’t arrest the culprits, conduct a search, or freeze assets. They can’t place wiretaps or conduct sting operations. They can only report their findings, to the government and to the public. In other words, watchdog ACAs are all bark and no bite. In the US state based Offices of Inspectors General monitor governmental programs and operations and provide their findings to legislative or executive decision makers and/or the public (CitationKempf, 2014, 2015).

Because of their limited powers, watchdogs cannot prove criminal violations and secure high-level criminal convictions. They rely on police and prosecutors, who may be unreliable partners. This makes it harder to demonstrate value to the public. Kos, commissioner of Slovenia's CPC, recalled: “When I had my first press conference in the commission, the first question I got was, ‘OK, so how many people will you arrest?’ And I explained why we were not here to arrest people. When I left [in 2010], the first question I got in the press conference was, ‘OK, so how many people have you arrested?’ I said, ‘What are you doing? I’ve spent six years chairing the commission trying to tell you that we are not the police, we are not the prosecutor service (CitationKuris, 2013b).”’

In some ways, however, watchdog ACAs benefit from their position outside the legal system. Their investigations are not bound by the legal constraints of criminal investigation: high evidentiary standards, strong due process requirements, and tight disclosure rules. Instead watchdog ACAs can act like investigative journalists with subpoena and audit powers, formal relationships with other public offices, and the prestige and media platform of government offices.

Unfettered by the rigours of criminal investigation, watchdog ACAs can respond quickly to emerging concerns and issue findings without waiting for determinations of individual culpability. They can expose systemic problems, ethical wrongdoing, and implications of corruption without fitting each violation to the elements of a specific criminal code. By focusing on systemic issues, watchdogs can address important but overlooked preventive issues like procurement reform (CitationPope & Vogl, 2000). Unlike guard dog ACAs, the reports of watchdog ACAs are not necessarily interpreted through the lens of criminal justice. Their reports can focus on ethical lapses and systemic weaknesses, rather than the presence or absence of grounds for criminal charges.

Watchdog ACAs may find it easier than guard dog ACAs to work on proactive corruption prevention, for two reasons. First, without as strong of an investigative focus, watchdog ACAs can devote more resources and attention to prevention. Second, unlike guard dog ACAs, they need not juggle adversarial and advisory roles when working with partners in government. If a watchdog ACA works with a government office, it can document on-going corruption risks and issue recommendations for their redress without an obligation to bring criminal charges. With less to fear from admitting wrongdoing, government offices can cooperate more freely.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, watchdog ACAs are more politically viable. Their non-criminal investigations are less personally threatening to adversaries and thus less likely to provoke pushback. As less powerful agencies, watchdog ACAs are less likely to be hijacked for political purposes, and less dangerous if they are manipulated. With lower expectations and smaller budgets, watchdog ACAs are less politically controversial and less likely to be shut down or to suffer donor disillusionment. Watchdog ACAs are less prone to turf wars with pre-existing law enforcement agencies.

Without enforcement powers, what can watchdog ACAs bring to the table? Watchdog ACAs share the same goal as guard dog ACAs: achieving reform to address on-going corruption and reduce risks of future corruption. Whereas a guard dog ACA pursues that goal through the tools of criminal justice, a watchdog ACA uses tools of illumination. CitationDaniel Feldman and David Eichenthal (2013) describe the success of independent watchdogs as “depend[ing] on their ability to apply the disinfectant of sunlight to the problems identified and to use a combination of political and communication strategies to achieve reform (p. 35).”

Many watchdog ACAs can expose corruption issues through public hearings. Ghana's CHRAJ used public hearings and reports to shame office holders linked to corruption. CHRAJ's findings forced the first resignation of a minister for corruption in Ghana's history and affected decisions by donor agencies about the allocation and administration of aid (CitationIyer, 2011).

Among some Commonwealth countries there is a tradition of commissions of enquiry or royal commissions, led by senior or retired judges and charged with making determinations of fact regarding specific cases or issues. Such commissions can resemble issue-specific watchdog ACAs with strong investigative tools but few police powers (although some can grant immunity from prosecution). Many commissions have had powerful impact on corruption. The “Fitzgerald Inquiry” that exposed revelations of police corruption in Queensland, Australia in the late 1980s prompted high-level prosecutions, political changes on a national scale, and profound reforms of police oversight (CitationPrenzler, 2011).

Watchdog ACAs can also issue non-binding opinions that expose problems and spur reforms. Slovenia's CPC exposed sophisticated high-level corruption networks by issuing advisory opinions about fact patterns taken from real-life cases. The commission anonymised the facts in each case to avoid ascribing criminal guilt to specific individuals and thereby violating libel laws. The CPC framed its advisory opinions as hypothetical situations and they carried no legal weight. Nevertheless, the advisory informed citizens drew connections between the advisory opinions and unethical behaviour by office-holders. The advisory opinions led to an increase in corruption awareness in a country previously perceived as relatively free of graft (CitationKuris, 2013b).

After the 2008 European Economic Crisis, the CPC issued powerful reports that exposed high-level corruption. Goran Klemenčič, the CPC director, used those reports to call for the resignation of the prime minister, opposition leader, and other high-level leaders. Unlike a guard dog ACA, the CPC could comment freely on its findings and their implications, since they had no legal force. The reports helped motivate a nationwide protest movement that toppled the government and prompted major reforms. Like the CPC, media-savvy watchdogs can attract media attention through high-impact reports.

An emerging area for watchdog ACA disclosure is to use subpoena and audit powers to open government records to the public, to empower non-governmental watchdogs and private citizens to detect corruption on their own. The Recovery Accountability and Transparency Board that the U.S. created to oversee the $800 billion economic stimulus plan of 2009 created an innovative portal to allow citizens to track the disbursal of public funds.Footnote2 The CPC launched an online interface called Supervizor that made all government spending in Slovenia easily searchable.Footnote3 The Campaign Finance Board of New York City created a searchable database of political donors and campaign expenditures.Footnote4

Ultimately, watchdog ACAs have a range of powers to expose corruption and spur reform, even without the fearsome teeth of a guard dog ACA. Much like guard dog ACAs, watchdogs are dependent upon partners in government and the justice sector to act upon their findings. More so than guard dog ACAs, watchdogs also depend upon the media, civil society, and the public at large. Because it can merely bark, a watchdog requires back-up.

5 Conclusion

The diverse experiences of guard dog and watchdog ACAs reveal many lessons for jurisdictions seeking to establish or reform ACAs, for ACAs seeking optimal strategies to survive and achieve results, and for the global anti-corruption movement seeking to boost reform efforts worldwide.

A jurisdiction weighing the creation of a guard dog or watchdog ACA must carefully and forthrightly consider its corruption problems and legal environment. Guard dog ACAs require substantial resources and attention. They address problems through the prism of law enforcement, with intent to trigger reform by “cleaning house” or deterring wrongdoing, and thus are not necessarily well suited to patterns of unethical behaviour or systemic corruption risks. Guard dog ACAs require legal systems capable of handling high-level corruption cases, in the absence of complementary specialized courts. In the right environment, a guard dog ACA can achieve substantial and lasting results. However, they must be made accountable and invulnerable to political subversion and pushback, fortified by strong internal controls and external sources of material and political support.

In contrast, watchdog ACAs are more manageable, versatile, viable, and adaptable to a range of conditions. However, they require partners inside and outside of government to act upon their findings. Without police powers, they face difficulties attracting public support. To achieve results, a watchdog ACA must deploy resources to research and communications, build strong partnerships, and respond strategically to specific corruption problems.

Because neither guard dog ACAs nor watchdog ACAs are inherently superior, actors in the global anti-corruption movement should reconsider their demands for agencies with stronger teeth. There may be better ways to make ACAs more effective: tightening internal protocols and procedures, securing fiscal and administrative autonomy, ensuring more open and independent leadership appointment and removal processes, establishing oversight mechanisms to better ensure independence, and building support coalitions capable of defending ACAs from political threats. Furthermore, ACAs only play a role in a broader anti-corruption system with many partners that require support, from judiciaries to audit bodies. Ultimately, neither watchdogs nor guard dogs can defend a home on their own.

Notes

1 The United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime keeps an updated list of anti-corruption authorities at http://www.track.unodc.org/ACAuthorities/Pages/home.aspx. Accessed 16.02.15.

2 URL: http://www.recovery.gov/arra/Pages/default.aspxa. Accessed 16.02.15.

3 URL: http://supervizor.kpk-rs.si/ (Slovene). Accessed 16.02.15.

4 URL: http://www.nyccfb.info/searchabledb/. Accessed 16.02.15.

References

- B. Anderson . Guard dog vs. watchdog. 2011 http://www.bradanderson.org/blog/2011/07/guard-dog-vs-watchdog/ Accessed 16.02.15.

- E. Bolongaita . An exception to the rule? Why Indonesia's anti-corruption commission succeeds where others don’t—A comparison with the Philippines’ Ombudsman. 2010. U4.

- A. Doig , D. Watt , R. Williams . Why do developing country anti-corruption commissions fail to deal with corruption? Understanding the three dilemmas of organizational development, performance expectation, and donor and government cycles. Public Administration and Development. 27 2007; 251–259.

- A. Doig , D. Watt , R. Williams . Measuring ‘success’ in five African anti-corruption commissions. 2005. U4.

- D. Feldman , D. Eichenthal . The art of the watchdog. 2013; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY

- W. Ginsberg . Offices of inspectors general and law enforcement authority: In brief. Congressional Research Service. 2014 http://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc462481/ Accessed 16.02.15.

- A. Graycar . Corruption: Classification and analysis. Policy and Society. 34 2015; 2.

- A. Graycar , T. Prenzler . Understanding and preventing corruption. 2013; Palgrave Macmillan.

- H. Hechler , B. Parkes . Annual review of DFID/RNE Malawi's Anticorruption Bureau Support Programme. 2010; Norad Collected Reviews.

- J. Heilbrunn . Anti-corruption commissions: Panacea or real medicine to fight corruption?. 2004; World Bank Institute.

- D. Hough . Corruption anti-corruption, and governance. 2013; Palgrave Macmillan.

- D. Iyer . Earning a reputation for independence: Ghana's Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice, 1993–2003. 2011; Innovations for Successful Societies, Princeton University. http://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/publications/earning-reputation-independence-ghanas-commission-human-rights-and-administrative Accessed 16.02.15.

- R. Kempf . Accountability remade: The diffusion and reinvention of offices of Inspectors General. (unpublished thesis) 2014; University of Kansas School of Public Affairs and Administration.

- R. Kempf . Crafting accountability policy: Designing offices of Inspector General. Policy and Society. 34 2015; 2.

- S. Kpundeh . Process interventions versus structural reforms: Institutionalizing anticorruption reforms in Africa. Building State Capacity in Africa: New Approaches, Emerging Lessons. 2004; 257–282.

- G. Kuris . ‘Inviting a tiger into your home’: Indonesia creates an anti-corruption commission with teeth: 2002–2007. 2012; Innovations for Successful Societies, Princeton University. http://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/publications/inviting-tiger-your-home-indonesia-creates-anti-corruption-commission-teeth-2002-2007 Accessed 16.02.15.

- G. Kuris . Holding the high ground with public support: Indonesia's anti-corruption commission digs in, 2007–2011. 2012; Innovations for Successful Societies, Princeton University. http://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/publications/holding-high-ground-public-support-indonesias-anti-corruption-commission-digs-2007-2011 Accessed 16.02.15.

- G. Kuris . Surmounting state capture: Latvia's anti-corruption agency spurs reforms, 2002–2011. 2012; Innovations for Successful Societies, Princeton University. http://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/publications/surmounting-state-capture-latvias-anti-corruption-agency-spurs-reforms-2002-2011 Accessed 16.02.15.

- G. Kuris . Balancing responsibilities: Evolution of Lithuania's anti-corruption agency, 1997–2007. Innovations for Successful Societies, Princeton University. 2012 http://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/publications/balancing-responsibilities-evolution-lithuanias-anti-corruption-agency-1997-2007 Accessed 16.02.15.

- G. Kuris . Cleaning house: Croatia mops up high-level corruption, 2005–2012. 2013; Innovations for Successful Societies, Princeton University. http://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/publications/cleaning-house-croatia-mops-high-level-corruption-2005-2012 Accessed 16.02.15.

- G. Kuris . Toothless but forceful: Slovenia's anti-corruption watchdog exposes systemic graft, 2004–2013. 2013; Innovations for Successful Societies, Princeton University. http://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/publications/toothless-forceful-slovenias-anti-corruption-watchdog-exposes-systemic-graft-2004-2013 Accessed 16.02.15.

- G. Kuris . From a rocky start to regional leadership: Mauritius's anti-corruption agency, 2006–2012. 2013; Innovations for Successful Societies, Princeton University. http://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/publications/rocky-start-regional-leadership-mauritiuss-anti-corruption-agency-2006-2012 Accessed 16.02.15.

- G. Kuris . Managing corruption risks: Botswana builds an anti-graft agency, 1994–2012. 2013; Innovations for Successful Societies, Princeton University. http://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/publications/managing-corruption-risks-botswana-builds-anti-graft-agency-1994-2012 Accessed 16.02.15.

- G. Kuris . From underdogs to watchdogs: How anti-corruption agencies can hold off potent adversaries. 2014; Innovations for Successful Societies, Princeton University. http://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/publications/underdogs-watchdogs-how-anti-corruption-agencies-can-hold-potent-adversaries Accessed 16.02.15.

- P. Meagher . Anti-corruption agencies: Rhetoric versus reality. Journal of Policy Reform. 8 2004; 69–103.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development . Specialised anti-corruption institutions: Review of models. 2nd ed., 2013. http://www.oecd.org/corruption/acn/specialisedanti-corruptioninstitutions-reviewofmodels.htm Accessed 16.02.15.

- M. Peters . The department of investigation's citytime investigation: Lessons learned & recommendations to improve New York City's management of large information technology contracts. 2014; New York City Department of Investigation. http://www.nyc.gov/html/doi/downloads/pdf/2014/July-2014/pr13citytime_72514.pdf

- J. Pope , F. Vogl . Making anticorruption agencies more effective. Finance & Development. 37(June): 2000; 2. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2000/06/pope.htm

- T. Prenzler . The evolution of police oversight in Australia. Policing and Society: An International Journal of Research and Policy. 21 2011; 3.

- J. Quah . Benchmarking for excellence: A comparative analysis of seven Asian anti-corruption agencies. The Asia Pacific Journal of Public Administration. 31(2): 2009, December

- J. Quah . Defying institutional failure: Learning from the experiences of anti-corruption agencies in four Asian countries. Crime Law and Social Change. 53 2010; 23–54.

- F. Recanatini . Anti-corruption authorities: An effective tool to curb corruption?. S. Rose-Ackerman , T. Søreide . International handbook on the economics of corruption, Volume Two. 2011; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, England

- Report of the Royal Commission of Enquiry into the Death of Teoh Beng Hock. 2011, June 22; Presented to Seri Paduka Baginda Yang Di-Pertuan Agong, Malaysia.

- P. Salkin , Z. Kansler . Ensuring public trust at the municipal level: Inspectors general enter the mix. Albany Law Review. 75 2011; 1.

- S. Schütte . Against the odds: Anti-corruption reform in Indonesia. Public Administration and Development. 32 2012; 38–48.

- L. De Sousa . Anti-corruption agencies: Between empowerment and irrelevance. Crime, Law and Social Change. 53.1 2010; 5–22.

- B. de Speville . Overcoming corruption: The essentials. 2010; De Speville & Associates: Surrey, England