Abstract

Corruption studies have suggested that corrupt politicians may win public support by providing substantial economic benefits to their citizens and that if a government works effectively to promote economic development, people may forgive its corruption problems. Thus, there is a positive relationship between citizens’ tolerance for political corruption and the economic benefits they receive from the government. Does economic well-being shape people's perceptions of corruption and the government's anti-corruption performance? If so, how and to what extent? To address the questions, this study draws on empirical data from a nationwide survey conducted in China in 2011. China makes an ideal case for the study because, although its unprecedented economic growth significantly improved people's living standards, the country has continued to suffer from rampant corruption. China's case illustrates the intricate relationships between the rise of economic status—perceived or actual—and attitudes toward the government's anti-corruption efforts among citizens.

1 Introduction

The relationship between people's economic status and their assessment of governmental policy performance is intricate and controversial. Scholars are puzzled by the fact that, in some countries, politicians win public support despite being corrupt (CitationRundquist, Strom, & Peters, 1977). For example, CitationChoi and Woo (2010) analyzed data from 115 developing countries and found that political corruption was not an important factor in determining electoral outcomes, and corrupt incumbents could retain political power if the economy progressed under their regime and citizens were greatly satisfied by the considerable improvement in their living standards. In another study, they further confirmed that national economic conditions could dilute the negative effect of political corruption (CitationChoi & Woo, 2012).

Based on a survey in Greece, CitationKonstantinidis and Xezonakis (2013) demonstrate that Greek voters would forgive corrupt politicians if these politicians could provide substantial collective benefits. Similarly, CitationManzetti and Wilson (2007) report that tangible economic benefits seem more important than having corrupt leaders punished among people living in countries with weak governmental institutions and strong patron-client relationships. This is particularly true in authoritarian systems where regimes and rulers are fused, and political legitimacy does not rest upon free elections but on certain unique characteristics and capabilities of political leaders (CitationChen, 1997). Economic success and subsequent improvement in people's living standards contribute to performance-based legitimacy (CitationYang & Zhao, 2014).

The studies above emphasize the importance of people's economic status in determining their assessment of and support for the government. They also suggest that as a result of significant improvement in economic well-being, people may be more likely to support their incumbent government even if it is corrupt. However, these studies often rely on aggregated macro variables, such as a country's economic development and corruption at national levels. They leave some questions unaddressed: Does economic well-being shape people's perceptions of corruption and the government's anti-corruption performance at the individual level? If so, how and to what extent?

This study attempts to answer the questions by examining how people's economic status affects their judgment of the government's performance in anti-corruption enforcement. We argue that while the level of corruption is an important indicator of a government's performance, people may see anti-corruption efforts equally, if not more, important in their evaluation of the government. To many, since corruption is unavoidable and threatens all societies, the extent to which a government fights corruption and succeeds in doing so matters more than the actual or perceived level of corruption. Citizens are likely to support a government and even credit its rulership with “legitimacy” if they are satisfied with the government's anti-corruption performance. Furthermore, we assume that when people's living standards improve significantly in a corruption-ridden setting, it is still possible that they will attribute the change to effective corruption control and thereby develop a more favorable attitude toward the government. In this study, we test these assumptions by examining the relationship between people's economic well-being and their perceptions of government performance in the area of corruption control.

We draw on empirical findings from China, which offers a typical case featured by both rapid economic growth and pervasive corruption (CitationLarsson, 2006; Wedeman, 2012). During the past three decades, China made unprecedented economic achievements, with an average annual growth rate of 9.7% from 1978 through 2010.Footnote1 Accelerating economic growth has benefited millions of people, significantly raising their living standards and, at the same time, enhancing the ruling power of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

However, corruption has continued to proliferate in the country, threatening future economic development and damaging public confidence in the government's governing capacity (CitationGong & Zhou, 2014; Li, Gong, & Xiao, 2015). In the annual Corruption Perception Index (CPI) calculated by Transparency International, China often ranks between 70th and 80th, lagging far behind some other East Asian countries and regions.Footnote2 Rampant corruption has led to intense crackdowns on corruption by the Chinese government. According to official statistics, in 2013 alone, anti-corruption agencies in China received 1.95 million corruption reports, a 49.2% increase from last year, and processed more than 172,000 cases. In addition, more than 180,000 government officials received disciplinary penalties.Footnote3 This indicates not only rampant corruption in the government but also the leadership's political will and effort to combat it. China thus offers an interesting case to see how the general public assesses the government's performance when they are caught in between dramatically improved livelihood and rampantly spreading corruption.

Based on a nationwide survey conducted in China in 2011, we carefully examine the role of both objective and subjective economic well-being of citizens in shaping their perceptions of the government's anti-corruption performance. To ensure the robustness of the results, we distinguish objective and subjective economic well-being of the respondents using various indicators. Our findings indicate that objective economic status, measured by individual income, family income, and family finances, has no significant influence on citizens’ perceptions of anti-corruption performance. In contrast, people who feel better off based on retrospective and prospective self-assessments and perceived social status in relative terms are more satisfied with the anti-corruption performance of the government.

The rest of our article is organized as follows. In the following section, we discuss theories about the economic well-being of citizens and its relationship with people's perceptions of anti-corruption performance, and we delineate our hypotheses. The third section describes the data sources and how we measure the key variables. We then use ordered logit models to compare the impacts of the objective and subjective economic well-being on people's perceptions of the government's anti-corruption performance and discuss our findings. The final section offers concluding remarks.

2 Theoretical perspectives and key hypotheses

Corruption measurement has attracted increased scholarly attention in the past decade (CitationSampford, Shacklock, Connors, & Galtung, 2006). Comparative corruption studies use cross-national datasets such as the CPIFootnote4 and World Governance Indicators (WGI)Footnote5 to explore the impact of economic, political, and cultural factors on perceptions of corruption (CitationAdes & Di Tella, 1999; Fishman & Gatti, 2002; Montinola & Jackman, 2002; Treisman, 2007). A growing number of researchers have also studied how to improve the validity of perception measurements. Some demonstrate the gap between perceived corruption and actual corruption (CitationArnold, 2012; Seligson, 2006). For example, CitationOlken (2009) compares the perceptions of corruption of villagers with an objective measure of corruption in a road-building project in Indonesia and found significant differences. Still, most scholars accept the importance of perceptions as “a good proxy for experiences” (CitationRazafindrakoto & Roubaud, 2010:1057) in corruption studies.

We concur with the necessity of exploring people's perceptions of corruption. Nevertheless, instead of simply demonstrating that people hold different perceptions, we focus on what accounts for the variation in their perceptions, especially the impact of individuals’ economic well-being on their attitudes toward the government's anti-corruption enforcement.

Specifically, we explore the possible linkage between individuals’ economic well-being and their perceptions of the government's anti-corruption performance. The CitationOECD (2013) defines economic well-being as the state of a person's material living conditions. We further distinguish two dimensions of individuals’ economic well-being: objective and subjective. The objective dimension reflects a person's income and wealth based on objective and tangible measurements or measured in terms of money, whereas subjective economic well-being denotes people's perception of their economic status in relation to others in society.

Some might argue that there is little difference between objective and subjective economic well-being, since people's subjective judgment of their well-being depends on their objective economic status. However, perceived economic well-being can differ from actual well-being because the former is more of a result from comparison with others in society, and it depends on what frame of reference, or evaluative criteria, the person opts to use. This separation is in line with previous research. For example, CitationBecher and Donnelly (2013) find that objective economic performance could only influence political behavior through individuals’ retrospective evaluation of the economy. Drawing on a survey dataset from China, CitationLü (2014) shows that objective and subjective economic changes influence an individual's sense of social inequality in different ways. Thus, in this study we treat subjective economic well-being and objective well-being as separate variables that have different effects on people's perceptions of government performance.Footnote6

In theory, individuals’ objective economic status may influence their evaluation of anti-corruption performance through two mechanisms: their experience with corruption and possible gain or loss from corruption. In a country where corruption and social inequality prevail, the rich may have more opportunities to form close ties with political elites and therefore benefit from a corrupt regime. Wealth accumulation may be aligned with hidden power-money deals, benefiting from corrupt exchanges with powerful elites (CitationChong & Gradstein, 2007; You & Khagram, 2005). Based on an empirical study in Peru and Uganda, CitationHunt and Laszlo (2012) show that the wealthier engage in bribery of public officials more frequently than the poor.

In transitional China, political ties, government-business clientelism, and guanxi are essential conditions for wealth accumulation of the new rich (CitationPei, 2006; Sun, 2004). CitationKo and Weng (2012) report that corruption in China's reform period often involves private-public collusion. More alarming is the loss of state funds due to corruption. Some recent cases reveal that corruption has become an important way of reallocating wealth, as both “big tigers” (i.e., higher level officials) and “small flies” (i.e., lower level ones) use various means to encroach on public assets. Liu Tienan, the former chief of the National Energy Administration, for example, was found to have pocketed ¥35.58 million while carrying out his duties from 2002 to 2012.Footnote7 Another official at a much lower lever, Wei Pengyuan, who served as a deputy division head of the National Development and Reform Commission, embezzled more than ¥200 million through corrupt activities. Footnote8

In contrast, the poor are more vulnerable to and are often victimized by corrupt officials (CitationKaufmann, Montoriol, & Recanatini, 2008). Compared to the rich, they are more likely to see corruption as prevalent and are less likely to be satisfied with the government's anti-corruption effort and performance. However, if their economic status improves significantly, and they consequently suffer less from corruption, they are also more likely to attribute the change to the government's anti-corruption effort. Empirical data gathered by CitationZhu, Lu, and Shi (2013) reveals that, in China, people who hold a more positive view of their current economic improvement and are more satisfied with income distribution tend to see less corruption in local governments. The government gains so-called “eudaemonic legitimacy,” a mode of legitimacy based on the justification of the regime's rulership by its successful performance and effective provision of economic benefits to its citizens and by the exchange of material goods for public support (CitationChen, 1997).

Based on this line of reasoning, we hypothesize:

H1

A higher level of objective economic well-being causes people to be more satisfied with the government's anti-corruption performance.

With regard to subjective well-being, studies on citizens’ political attitudes show that their assessment of the government's behavior and performance sometimes rests on instrumental or practical considerations (CitationLipset & Schneider, 1987; Norris, 1999; Rose, Mishler, & Munro, 2011), which are related to one's evaluation of economic benefits delivered or to be delivered by the regime. In particular, subjective economic well-being is associated with people's trust in the government and with people's assessment of government performance in relation to their normative expectations of how government should perform (CitationHetherington & Husser, 2012; Levi & Stoker, 2000). Cross-national empirical studies have confirmed that citizen's economic evaluation is a salient source of regime support. CitationPrzeworski, Alvarez, Cheibub, and Limongi (1996), for instance, found that people's economic perception strongly helped new democracies to endure for a much longer period of time. CitationTorcal (2014) reports that in Spain and Portugal, citizens’ negative assessment of economic well-being during the 2008 economic recession significantly eroded their trust and support for the government. Such trust and support may concern different areas of a government's performance including corruption and anti-corruption enforcement. Thus, citizens with lower levels of political trust are more likely to radically condemn the misuse of power by government officials (CitationWroe, Allen, & Birch, 2013).

Furthermore, some studies have also found that a higher level of subjective economic well-being could lead citizens to condone government corruption. An experiment in Brazil suggests that people who perceive a better-off economic status are more tolerant of government corruption, whereas those who think that they are at the bottom of society tend to hold a more critical attitude toward corruption (CitationWinters & Weitz-Shapiro, 2013). Similarly, drawing on a combined data set from Asia, Latin America, and Africa, CitationLi, Tang, and Huhe (2014) find that the self-evaluation of economic well-being is a robust factor that mitigates citizen's perception of government corruption. In China today, to maintain rapid economic growth has become critically important. It is not only a necessary condition for the government to retain its performance-based legitimacy, but also a great expectation of the general public. Having suffered from poor living conditions and poverty for decades under the former centrally planned economy, the Chinese people are keen to see the country getting modernized and they support, in particular, those government officials who are capable of promoting economic development in their localities. For these reasons, the economic performance of local governments often becomes the most important criterion for selecting local officials. Some local people even think that a little bit of corruption is acceptable as long as local government officials can bring economic benefits to them. They can tolerate corrupt officials who are capable of promoting the economy but not mediocre leaders who are honest yet accomplish nothing.Footnote9

All this indicates the importance of people's perceptions about their economic well-being. In this study we develop a nuanced perspective on subjective economic well-being. While objective economic well-being concerns people's economic environment or living standard per se, subjective economic well-being reflects how they evaluate it. Better objective economic conditions do not necessary generate a higher self-economic evaluation, as CitationBecher and Donnelly (2013: 968) suggest: “there is little comparative evidence on whether economic performance actually shapes evaluations, leaving open the possibility that subjective evaluations are not or only weakly related to the objective economy.” This is because people tend to assess their economic well-being in relative terms. For example, they may look back at their economic situation several years ago to determine whether they are better off or not today. They may also assess their current economic well-being by its potential to generate more wealth in future. Finally, people may evaluate their socio-economic status by comparing it to others in society, which leads to a sense of relative deprivation (CitationGurr, 1970) or relative satisfaction. Thus we hypothesize that there is a positive relationship between subjective economic well-being and people's satisfaction with the anti-corruption performance of a government and specifically:

H2a

A higher level of retrospective assessment of economic well-being makes people more satisfied with the government's anti-corruption performance.

H2b

A higher level of prospective assessment of economic well-being makes people more satisfied with the government's anti-corruption performance.

H2c

A higher level of perceived better off economic status in comparison with others makes people more satisfied with the government's anti-corruption performance.

3 Data and measurements

3.1 Data

To test these hypotheses, we draw on the Chinese Social Survey (CSS), conducted by the Institute of Sociology of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) in 2011.Footnote10 The CSS collects data on public perceptions of social and economic transitions in China through longitudinal surveys of people's views on various social issues. The CSS in 2011 (hereafter CSS2011) was carried out in 25 provinces and municipalities, covering 472 rural villages and urban residents’ committees.Footnote11

It used multistage cluster sampling to select households first and then drew individuals from the sampled households using a Kish grid to ensure representativeness within households. In the Kish grid method, all qualified members in the selected households had an equal opportunity for being selected for interview. This helps avoid selection bias caused by the fact that some household members such as homemakers tend to be available more often. The survey obtained 7255 valid questionnaires in total. In general, the CSS2011 is one of the most up-to-date and reliable surveys with broad nationwide coverage of public attitudes in China.

3.2 Measuring satisfaction with anti-corruption enforcement

The CSS2011 measures public satisfaction with governmental performance in various areas. Since the focus of our study is to explain the variation in citizens’ satisfaction levels with local governments’ anti-corruption efforts, we select one question therein to gauge the dependent variable: “Do you think the performance of the local government in your area is good or bad in upholding integrity and fighting corruption?” Answers are recorded as an ordinal variable on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (very bad) to 4 (very good).

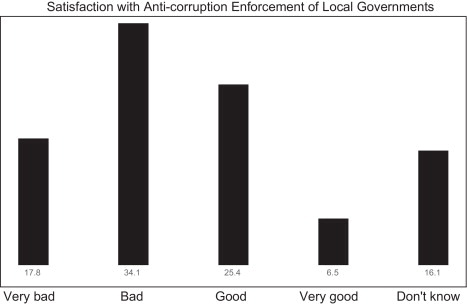

shows the frequency distribution of the levels of public satisfaction with local governments’ anti-corruption enforcement. As it indicates, the Chinese public was generally very unsatisfied with local governments’ anti-corruption performance in 2011. More than half (51.9%) of respondents gave negative answers to the question, rating it as “very bad” or “bad,” while only 31.9% said “good” or “very good.”

Fig. 1 “Do you think the performance of the local government in your area is good or bad in upholding integrity and fighting corruption?”

Source: Chinese Social Survey 2011 (CSS2011).

This survey result is generally consistent with those of international surveys on China's anti-corruption performance. For example, in the Worldwide Governance Indicators provided by the World Bank, China only got −0.6 point on a scale from −2.5 to 2.5 in terms of “Control of Corruption” in 2011.Footnote12 Scholars tend to believe that the exposure of grand corruption scandals may significantly influence public perceptions of corruption (CitationCostas-Perez, Solé-Ollé, & Sorribas-Navarro, 2012; Reed, 1999). Whereas this holds true in general, the CSS2011 was not affected by such external political factors. No grand corruption scandal was reported in China in 2011, and it was relatively a clean and quiet political year.

3.3 Measuring objective and subjective economic well-being

Although it is difficult to accurately measure a person's economic status, the CSS2011 allows us to do it in a relatively reliable fashion because it used several methods to cross-check respondents’ economic status. Based on the CSS2011 dataset, we use two groups of indicators to measure respondents’ economic well-being. One is to measure their economic status using fixed criteria in a more objective way, which we refer to as “objective economic status.” The other variable, “subjective economic well-being,” gathers information on respondents’ own feeling of their economic conditions.

Specifically, we use three different survey questions to gauge people's objective economic status. The first is respondents’ overall annual income in 2010. This includes the individual's total income from salaries, pensions, subsistence allowances, welfare benefits, and investment earnings. The second question asks about the respondent's total family income in 2010 in the same way as individual income. Because people's economic status is determined not only by income but also by assets, the CSS2011 includes questions on respondents’ family finances, including: (a) bank savings; (b) securities, futures, and the like (calculated by purchase prices); and (c) family movables, including valuable jewelry, collections, furniture, household appliances, household vehicles, IT products, sports equipment, kitchenware, sanitary ware, and so on (calculated by purchase prices). We add together the values of the three parts to get the information on the respondent's family finances.

Third, the CSS2011 includes a question on people's immovable property, asking how many apartments they own. As a matter of fact, the ownership situation of housing property in China is rather complex. People might have purchased apartments at a very low cost or simply no cost subsidized by their work-units or sponsored by their parents. A person might actually own several apartments but have them registered under relatives’ names. For these reasons, the question on housing property may not accurately reflect a person's real economic status. Therefore, we do not include it in our analysis.

We use three questions in the CSS2011 to measure individuals’ subjective economic well-being. The first is a retrospective question: “In comparison with five years ago, what change has taken place in your living standards?” The options are significantly decline, slightly decline, no change, slightly improve, and significantly improve, which are coded from 1 to 5. The second question is prospective: “What changes do you think will take place in your living standards in next five years?” Again, there are five options: significantly decline, slightly decline, no change, slightly improve, and significantly improve. The third question asks specifically about the perception of their economic status: “Which socio-economic stratum do you think you belong to in your locality?” The respondent may choose one from the following answers: bottom, lower middle, middle, upper middle, and top, labeled from 1 to 5.

3.4 Control variables

Our study includes control variables on several widely recognized demographic factors that can affect people's evaluation of anti-corruption enforcement: gender, age, education, and residence status. Gender is coded as male = 1 and female = 0. Age is a continuous variable coded from 17 to 101 years old. The original dataset classifies education into 9 levels ranging from no schooling to post-graduate education. We consolidate and recode them into three categories: those with no school and primary education = 1; secondary education = 2; and tertiary or above = 3. In terms of residence status, respondents from registered urban households = 1, while those who do not have registered urban status = 0.

In addition, we control for party membership, a political variable that may have a crucial impact on people's attitudes toward social and political issues. This is because, under China's current Party-state political structure, CCP members enjoy better social and political status and are likely to develop favorable views toward government policies. In the original data, party membership includes three categories: members of the ruling party (the CCP), members of small, non-ruling parties, and people without party affiliation. We code CCP members as 1 and all those without CCP membership as 0. This is because, under the one-party system, members of non-ruling parties do not play any strong decision-making role.

Previous studies on public perceptions of anti-corruption also point to the importance of media exposure (CitationGoel, Nelson, & Naretta, 2012; Zhu et al., 2013). CitationArnold (2012) points out that the accuracy of perceptions of corruption is associated with how much political information people have. Using China as a case, CitationZhu et al. (2013) find that official media controlled by the government reduces the corruption level perceived by the general public, whereas news through the grapevine has the opposite effect. In our study, we take into account individuals’ Internet use by asking the question: “Through which communication channel do you learn about important events in society?” We code “Internet” as 1 and other options as 0.

As a result of the dramatic rise of new social communication technologies and a burgeoning civil society, China has witnessed strong competition between traditional media and new media. Many corruption scandals have been exposed via the Internet, and it appears that official control over the Internet might not be as strong as that over traditional media. Therefore, it is likely that people who have more access to social media may receive negative information on corruption more frequently and thus become less satisfied with the government's anti-corruption performance.

Apart from these aforementioned variables, certain political views should be controlled for as well. People may have very different opinions, for example, about the role of the government in society. Some may prefer to have a government active in maintaining social order and regulating different aspects of social life, while others may like a small government, following the Lockean doctrine of “that government is best that governs least” (CitationStevens, Bishin, & Barr, 2006). In this study, we coin a term—“the sense of political authority”—to gauge in the aggregate how people perceive the role of the government in the areas that can affect their livelihood, using the questions that ask them whether they would agree with the following statements: (a) people should move out if the government needs to remove their houses for construction;Footnote13 (b) people should obey the government, just as subordinates obey superiors; (c) democracy means that the government makes decisions for its people; and (d) the government takes upon state affairs while there is no need for the public to have their hands in. The more respondents agree with these statements, the stronger their sense of political authority.

Performing a factor analysis on these four questions, we find a reliable common factor that can be extracted with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.71, which is higher than the critical value 0.7.Footnote14 We use the predicted factor score as the variable to measure the sense of political authority. Theoretically, people with a stronger sense of authority should be more satisfied with the government's anti-corruption performance (CitationSolt, 2012; Stevens et al., 2006). provides the descriptive statistics.

Table 1 Statistical description of relevant variables.

4 Findings and discussion

Because the dependent variable is ordinal ranging from 1 to 4, we use an ordered logistic model to examine the relationship between citizens’ economic well-being in both objective and subjective dimensions and their perception of anti-corruption performance.Footnote15 This survey asks respondents about their opinions on the performance of their local governments, and their views might be affected by unobservable variables, such as local politics, economies, and culture. Thus we introduce a province-based fixed effect in all regression specifications to control the potential impact of local contexts, thereby obtaining the net coefficients of independent variables. reports the regression results.

Table 2 Economic well-being and satisfaction with anti-corruption performance.

Notes: 1. The dependent variable in all the models is the satisfaction with local governments’ anti-corruption enforcement.

2. All are ordered logit models.

3. All models use weighted data, and the provincial fixed effects controlled for. The estimates of dummies variables for provincial fixed effects are omitted in this table.

As the baseline, Model 1 only introduces control variables. Gender, age, party membership, and the sense of political authority all have a significant impact on the respondents’ assessment of the government's anti-corruption performance, while education, residence status, and the use of the Internet appear to be non-significant. In Models 2, 3, and 4, we introduce three measures of objective economic status: individual income in 2010, household income in 2010, and the estimated value of household properties.Footnote16 With the variables in Model 1 controlled for, the coefficients between economic status measured by the three objective variables and their perception of anti-corruption performance are not significant.

This indicates that objective economic well-being has limited influence over how a person evaluates the government's anti-corruption performance. In contrast to the theory discussed before that improved economic conditions might lead people to forgive government corruption and increase their corruption tolerance levels, we find from Models 2, 3, and 4 weak association between people's objective economic well-being and their assessment of the government's anti-corruption performance.

Although the magnitude of the relationship is not strong enough to confirm any correlation, the results show a negative relationship between the two variables. That is, people with higher economic status tend to be less satisfied with the government's anti-corruption performance. It remains debatable whether better-off people tend to be less satisfied with the government's performance in controlling corruption and, if so, what explains it. If this is true, it might have something to do with their higher expectations but lower satisfaction with the protection provided by the government for their economic interests. It is conceivable that they would very much need the government to do more to help maintain an orderly and stable social environment so that unlawful activities such as corruption will not infringe upon their economic well-being. In other words, strong economic interests as manifested in personal wealth might lead people to develop more political demands on the government such as corruption control. This requires further testing and discussion beyond this study.

This study measures subjective economic well-being with three variables: retrospective assessment of respondents’ living conditions over the past five years, prospective evaluation of their well-being in the next five years, and self-assessment of their economic status compared to other people in society. We introduce these subjective economic well-being indicators to the benchmark model and present the results in Models 5, 6, and 7.

After controlling for all other variables, the coefficients of these subjective measures are highly significant. In other words, respondents show greater satisfaction with the government's anti-corruption performance when they perceive their current economic well-being to be better off now than five years ago, when they believe that their economic situation will be even better in the next five years, or when they consider themselves as part of the better-off group compared to others in society. These findings are consistent with our hypotheses that citizens would have higher satisfaction with anti-corruption performance if they believe they are economically better off. Our findings confirm that people's economic status can affect their perceptions and attitudes toward corruption and anti-corruption efforts of the government. Nevertheless, our research indicates precisely that the causal pathway lies less with their objective economic status than with their subjective well-being.

Because it may be argued that people's subjective economic well-being strongly correlates with their actual economic situation, we have carefully tested the validity of the separation of the two in our sample. presents the bivariate pairwise correlations matrix of the objective and subjective economic well-being. As it shows, the measures of objective economic situations (i.e., personal income, family income, and household property) have weak correlations with retrospective and prospective subjective evaluations of economic well-being—no coefficient even reaches the level of 0.1.

Table 3 Bivariate pairwise correlations between objective and subjective economic well-being.

The last row in shows a weak correlation between objective economic status and perceived social status. However, the fact that the highest coefficient is 0.32 indicates that the relationship is weak. It is safe to say that the objective and subjective indicators have distinct functions in measuring individuals’ economic status. Therefore, they can have independent effects on people's assessment of the government's anti-corruption performance.

Apart from the findings about the original hypotheses, this study also yields some other intriguing results about control variables. We find that gender has a significant and consistent impact on people's assessment of anti-corruption performance. Male respondents appear to be less satisfied with the government's anti-corruption work. This is in line with some scholarly analysis of China's situation where, due to labor allocation between men and women in the family, women tend to take care of the family affairs, while men interact more frequently with the government (CitationCui, Tao, Warner, & Yang, 2014). The situation may be different in other countries (CitationDollar, Fisman, & Gatti, 2001; Frank, Lambsdorff, & Boehm, 2011; Swamy, Knack, Lee, & Azfar, 2001), but a detailed discussion of the issue is beyond this study because gender is a control variable in our analysis.

Party affiliation has a significant and expected impact; that is, CCP members tend to be more satisfied with the government's anti-corruption performance than non-CCP members as shown by our regression results. Similarly, people's sense of authority exerts a significant and robust impact on people's perception of anti-corruption performance. Consistent with our assumption, people who have a stronger sense of authority are more satisfied with the government's anti-corruption work.

The variables of education and residence status are not significant in any of the regression models, indicating their very marginal impact, if any, after we control for independent variables. Nevertheless, the direction of education coefficients comes out as expected; namely, respondents with more education are less satisfied with the government's anti-corruption performance, possibly because they tend to have a more critical attitude. Surprisingly, the use of the Internet as the major channel of information turns out to have no impact on people's perception of anti-corruption efforts in our models. This unexpected outcome may be caused by the wording of the question in the CSS2011: “Through which communication channel do you learn about important events in society?” This question may find out the channels through which citizens learn about important social events, but cannot provide accurate information on the frequency and extent to which they depend on the Internet.

5 Conclusion

Citizens’ assessment of the anti-corruption performance of government is an important issue and has attracted worldwide scholarly attention. Based on a national survey conducted in China in 2011, this study offers some mixed evidence on the conventional wisdom that economic well-being mitigates negative views of anti-corruption performance. We distinguish the objective dimension and subjective dimension of individuals’ economic well-being and test the possible causal pathways by which these two kinds of economic well-being might affect people's satisfaction with the government's anti-corruption enforcement. Our findings show that in contrast to the conventional wisdom, objective economic well-being has no significant impact on people's assessment of anti-corruption performance. However, there is a substantial and significant positive relationship between respondents’ subjective economic well-being and their assessment of the government's performance in controlling corruption. This association fits with our hypothesis; that is, people who have a stronger sense of subjective economic well-being tend to place more trust in the government, which in turn elevates their perception of anti-corruption performance.

Our study makes two theoretical contributions. First, the findings suggest that subjective economic well-being is more important than objective economic status in shaping citizens’ perceptions the government's anti-corruption performance. This leads to a more nuanced picture of how people's economic well-being can influence their views toward the government. Second, we find that people's economic well-being is a dynamic concept, which should be measured by changes in their economic status, rather than in absolute terms. More specifically, our study finds that citizens’ assessments of the government's anti-corruption effort are more sensitive to improvements in their economic well-being, especially the extent to which they see themselves as better off compared to others in society.

This research also has practical implications for China and potentially other countries. Policy makers should be aware of the intricate and complex linkage between people's economic well-being and their satisfaction with the government's anti-corruption efforts. In recent years, the Chinese government has intensified its crackdown on both grand corruption and petty corruption through top-down anti-corruption campaigns. However, having political will to fight corruption is far from being enough (CitationFritzen, 2005). Since no government can succeed in its effort to curb corruption without public support, leaders with strong political will to fight corruption must pay attention to whether their anti-corruption drive meets people's expectation and enhances people's satisfaction with the government's performance.

Notes

* This research presents the initial results of a project supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (NSSFC, Grant No. 11CZZ015). This work is supported by grants from the Research Grants Council in Hong Kong (CityU 11402814), City University of Hong Kong (7004097), and The National Social Science Fund of China (No. 13&ZD011).

1 This figure was calculated by the authors based on the annual GDP growth during this period. The data were collected from the official website of National Statistics Bureau (http://www.stats.gov.cn/).

2 For more details, see http://www.transparency.org (accessed 10.12.14). According to the 2013 CPI, Singapore was ranked 5th, Hong Kong 15th, Japan 18th, Taiwan 36th, and Korea 46th.

3 Source: Annual Report of Disciplinary Inspection Committees in 2013. For more information, see: http://fanfu.people.com.cn/n/2014/0110/c64371-24076711.html (accessed 27.01.15).

4 For more details, see http://cpi.transparency.org/cpi2013/in_detail/.

5 See the following website for more details: http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.aspx#home.

6 Our findings and discussion later provide further support for this argument. We find that there is very weak association between objective and subjective measures in our data set.

7 For detailed information, see http://www.chinanews.com/fz/2014/12-10/6862378.shtml (accessed 27.04.15).

8 http://china.caixin.com/2014-05-20/100679394.html (accessed 26.04.15).

9 http://news.sina.com.cn/zl/zatan/2014-11-05/11542576.shtml (accessed 29.04.15).

10 For details, refer to: http://www.sociology2010.cass.cn/news/708523.htm.

11 Urban residents’ committees, also known as community residents’ committees (shequ jumin weiyuanhui), are responsible for administering local socio-economic and political affairs in urban neighborhoods.

12 This figure is obtained from the website of World Bank: http://databank.worldbank.org/data/views/reports/tableview.aspx (accessed 20.01.15).

13 The accelerated urbanization and rapid development of the housing industry in China in recent decades have led to massive land expropriation and housing demolition. This has caused public grievances and even popular resistance.

14 Cronbach's alpha is a coefficient of internal consistency. It is commonly used as an estimate of the reliability of a psychometric test for a sample of examinees. For more information, see CitationCronbach (1951).

15 The ordered logit model is a regression model for ordinal dependent variables. For more details, see CitationLong and Freese (2003). We also ran OLS regressions and found consistent results.

16 Because the distribution of these original values is skewed, we used their natural logarithm in all regression models.

References

- A. Ades , R. Di Tella . Rents, competition and corruption. The American Economic Review. 89(4): 1999; 982–993.

- J.R. Arnold . Political awareness, corruption perceptions and democratic accountability in Latin America. Acta Politica. 47(1): 2012; 67–90.

- M. Becher , M. Donnelly . Economic performance, individual evaluations, and the vote: Investigating the causal mechanism. The Journal of Politics. 75(4): 2013; 968–979.

- F. Chen . The dilemma of eudaemonic legitimacy in Post-Mao China. Polity. XXIX(3): 1997; 421–439.

- A. Chong , M. Gradstein . Inequality and institutions. Review of Economics and Statistics. 89 2007; 454–465.

- E. Choi , J. Woo . Political corruption, economic performance, and electoral outcomes: A cross-national analysis. Contemporary Politics. 16(3): 2010; 249–262.

- E. Choi , J. Woo . Political corruption, economy, and citizens’ evaluation of democracy in South Korea. Contemporary Politics. 18(4): 2012; 451–466.

- E. Costas-Perez , A. Solé-Ollé , P. Sorribas-Navarro . Corruption scandals, voter information, and accountability. European Journal of Political Economy. 28 2012; 469–484.

- L.J. Cronbach . Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 16(3): 1951; 297–334.

- E. Cui , R. Tao , T. Warner , D. Yang . How do land takings affect political trust in rural China?. Political analysis. 2014 10.1111/1467-9248.12151.

- D. Dollar , S. Fisman , R. Gatti . Are women really the ‘fairer’ sex? Corruption and women in government. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 46 2001; 423–429.

- R. Fishman , R. Gatti . Decentralization and corruption: Evidence across Countries. Journal of Public Economics. 83(3): 2002; 325–345.

- B. Frank , J.G. Lambsdorff , F. Boehm . Gender and corruption: Lessons from laboratory corruption experiments. European Journal of Development Research. 23(1): 2011; 59–71.

- C. Fritzen . Beyond “political will”: How institutional context shapes the implementation of anti-corruption policies. Policy & Society. 24(3): 2005; 79–96.

- R.K. Goel , M.A. Nelson , M.A. Naretta . The Internet as an indicator of corruption awareness. European Journal of Political Economy. 28 2012; 64–75.

- T. Gong , N. Zhou . Corruption and marketization: Formal and informal rules in Chinese public procurement. Regulation & Governance. 2014 10.1111/rego.12054.

- T.R. Gurr . Why men rebel. 1970; Princeton University Press: Princeton

- M.J. Hetherington , J.A. Husser . How trust matters: The changing political relevance of political trust. American Journal of Political Science. 56(2): 2012; 312–325.

- J. Hunt , S. Laszlo . Is bribery really regressive? Bribery's costs, benefits and mechanism. World Development. 40 2012; 355–372.

- D. Kaufmann , J. Montoriol , F. Recanatini . How does bribery affect public service delivery? Micro-evidence from service users and public officials in Peru. 2008; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 4492: Washington, D.C

- K. Ko , C. Weng . Structural changes in Chinese corruption. The China Quarterly. 211 2012; 718–740.

- I. Konstantinidis , G. Xezonakis . Sources of tolerance towards corrupted politicians in Greece: The role of trade offs and individual benefits. Crime, Law and Social Change. 60 2013; 549–563.

- T. Larsson . Reform, corruption, and growth: Why corruption is more devastating in Russia than in China. Communist and Post-Communist Studies. 39 2006; 265–281.

- M. Levi , L. Stoker . Political trust and trustworthiness. Annual Review of Political Science. 3 2000; 475–507.

- H. Li , T. Gong , H. Xiao . The perception of anti-corruption efficacy in China: An empirical analysis. Social Indicators Research. 2015 10.1007/s11205-015-0859-z.

- H. Li , M. Tang , N. Huhe . Does democratization colour citizen's ideas: The role of democracy as the contextual condition of corruption perceptions. 2014; Working Paper, presented at: Comparative Politics: Global Perspective and Chinese Issues, Center For Comparative Political Development Studies, Fudan University: Shanghai, China

- S.M. Lipset , W. Schneider . The confidence gap: Business, labor, and government in the public mind. 1987; Free Press: New York

- J.S. Long , J. Freese . Regression models for categorical dependent variables using stata. 2003; Stata Press: United States of America

- X. Lü . Does changing economic well-being shape resentment about inequality in China?. Studies in Comparative International Development. 49(3): 2014; 300–320.

- L. Manzetti , C.J. Wilson . Why do corrupt governments maintain public support?. Comparative Political Studies. 40(8): 2007; 949–970.

- G. Montinola , R. Jackman . Sources of corruption: a cross-country study?. British Journal of Political Science. 32 2002; 147–170.

- P. Norris . Introduction: The growth of critical citizens?. P. Norris . Critical citizens: Global support for democratic government. 1999; Oxford University Press: Oxford and New York 1–17.

- OECD . Economic well-being. 2013. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/statistics/OECD-ICW-Framework-Chapter2.pdf (accessed 26.01.15).

- B.A. Olken . Corruption perceptions vs. corruption reality. Journal of Public Economics. 93 2009; 950–964.

- M. Pei . China's trapped transition: The limits of developmental autocracy. 2006; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Mass

- A. Przeworski , M. Alvarez , J.A. Cheibub , F. Limongi . What makes democracies endure?. Journal of Democracy. 7(1): 1996; 39–55.

- M. Razafindrakoto , F. Roubaud . Expert opinion surveys and household surveys in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Development. 8 2010; 1057–1069.

- S.R. Reed . Publishing corruption: The response of the Japanese electorate to scandals. O. Feldman . Political psychology in Japan: Behind the nails which sometimes stick out (and get hammered down). 1999; Nova Science: Commack, NY

- R. Rose , W. Mishler , N. Munro . Popular support for an undemocratic regime: The changing views of Russians. 2011; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge and New York

- B.S. Rundquist , G.S. Strom , J.G. Peters . Corrupt politicians and their electoral support: Some experimental observations. American Political Science Review. 71 1977; 954–963.

- C. Sampford , A. Shacklock , C. Connors , F. Galtung . Measuring corruption. 2006; Ashgate Publishing Group.

- M.A. Seligson . The measurement and impact of corruption victimization: Survey evidence from Latin America. World Development. 34(2): 2006; 381–404.

- D. Stevens , B.G. Bishin , R.R. Barr . Authoritarian attitudes, democracy, and policy preferences among Latin American Elites. American Journal of Political Science. 50(3): 2006; 606–620.

- F. Solt . The social origins of authoritarianism. Political Research Quarterly. 65(4): 2012; 703–713.

- Y. Sun . Corruption and markets in contemporary China. 2004; Cornell University Press.

- A. Swamy , S. Knack , Y. Lee , O. Azfar . Gender and corruption. Journal of Development Economics. 64 2001; 25–55.

- M. Torcal . The decline of political trust in Spain and Portugal: Economic performance or political responsiveness. American Behavioral Scientist. 58 2014; 1542–1567.

- D. Treisman . What have we learned about the causes of corruption from ten years of cross-national empirical research?. Annual Review of Political Science. 10 2007; 211–244.

- A. Wedeman . Double paradox: Rapid growth and rising corruption in China. 2012; Cornell University Press.

- M.S. Winters , R. Weitz-Shapiro . Lacking information or condoning corruption? When will voters support corrupt politicians?. Comparative Politics. 4 2013; 418–436.

- A. Wroe , N. Allen , S. Birch . The role of political trust in conditioning perceptions of corruption. European Political Science Review. 5 2013; 275–295.

- H. Yang , D. Zhao . Performance legitimacy, state autonomy and China's economic miracle. Journal of Contemporary China. 2014 10.1080/10670564.2014.918403.

- J.S. You , S. Khagram . A comparative study of inequality and corruption. American Sociological Review. 70 2005; 136–157.

- J. Zhu , J. Lu , T. Shi . When grapevine news meets mass media: Different information sources and popular perceptions of government corruption in Mainland China. Comparative Political Studies. 46(8): 2013; 920–946.