Abstract

Police departments in the United States have been increasingly involved in placing their sworn officers in off-duty jobs. Individual officers, commanders or union representatives in a number of police agencies earn commissions by brokering off-duty jobs for fellow officers, a practice the US Department of Jus tice characterized as an “artery of corruption” in the New Orleans Police Department. In response to actual or potential corruption by entrepreneurial officers and unions acting as employment brokers, many police agencies now directly place officers in off-duty jobs. Corruption has tainted agency-managed officer placements as well, leading to corruption charges against Pittsburgh's Police Chief and bringing into stark relief how departments generate business and account for commissions earned by placing fully uniformed officers in private employment via “police details”—as the practice is commonly called. This paper looks at “police details” in terms of the realized and potential types of corruption they engender, and the kinds of off-duty employment activities that pose integrity threats, both for the individuals involved and for their law enforcement agencies. The paper concludes by discussing public policy questions raised when police agencies and officers monetize taxpayer-funded training, symbols of office and equipment in order to command premium wages in off-duty employment.

1 Introduction

“Aorta of corruption” was the characterization the Civil Rights Division of the United States Department of Justice applied to the management of off-duty employment in the New Orleans Police Department (CitationDOJ, 2011, p. XVI). That conclusion rested upon a number of practices, none unique to New Orleans, which had corrosive impacts on police integrity, efficiency and effectiveness. The practices cited by the Justice Department included:

| • | Off-duty pay rates that could, and did, exceed on-duty pay rates. | ||||

| • | Off-duty work hours that could, and at times did, exceed on-duty work hours. | ||||

| • | Officers who made more money off-duty than they earned from the NOPD. | ||||

| • | Off-duty work that was “off-the-books,” implicating officers in tax evasion. | ||||

| • | Off-duty jobs being brokered by officers and commanders while on-duty. | ||||

| • | Officer-brokers securing high paying details for superiors. | ||||

| • | Off-duty security jobs where officers could, and did, outrank NOPD superiors. | ||||

All of which led the Department of Justice to conclude in 2011 that: “NOPD's detail system, as currently structured: (1) drastically undermines the quality of NOPD policing; (2) facilitates abuse and corruption by NOPD officers; (3) contributes to compromising officer fatigue; (4) contributes to inequitable policing by NOPD; and (5) acts as a financial drain on NOPD rather than fulfilling its potential as a source of revenue for the City and Department.” (CitationDOJ, 2011, p. XVI).

This paper will consider how police off-duty employment in the U.S. has been evolving in ways that have created opportunities for official corruption, self-dealing by officers and commanders, rent seeking by police departments and a shifting of police resources from public to private use.

2 Methods for securing and managing secondary employment

Police officers have long worked second jobs, an activity popularly identified as “moonlighting.” Police officers usually refer to their off-duty employment as “side jobs,” “details” or “second jobs.”Footnote1 Traditionally individual officers offered their labor to a variety of employers, most of whom placed a value on that labor that derived from the off-duty officer's ability to provide premium security services. A given employment transaction was completed when an officer freely exchanged his or her off-duty labor for acceptable remuneration from a willing employer.

In recent decades, factors underlying secondary police employment have been changing. Celebrities from the world of sports, entertainment and business have become more concerned about their safety and about the quality of security personnel they employ. Many jurisdictions, responding to fiscal constraints, have cut back on taxpayer funded police coverage for special events such as parades, sporting events and concerts, while the need for high quality security at these events has, if anything, been increasing. Laws have been passed in a number of jurisdictions requiring that sworn officers perform traffic control for road construction and repair, as well as locations such as construction sites and sports stadia that generate high volumes of traffic to and from public highways. Public authorities in the U.S. responsible for running seaports, airports and federally subsidized housing developments also generate demand for police coverage by off-duty officers, as is the case with the Louis Armstrong airport serving New Orleans, which straddles the jurisdiction of two county sheriff's offices, drawing upon off-duty officers from each agency to cover its security needs. As these service demands rise, low or slow-growing police salaries in many regions of the U.S. have made secondary employment more of an economic necessity for increasing numbers of officers.

All of these factors have fueled the growth of secondary police employment and increased off-duty wages paid officers, often beyond their regular hourly wages as public employees. When off-duty work pays a premium, usually for less demanding and at times more interesting security tasks, even more officers are induced to participate in the secondary employment market.

To handle the increased demand for off-duty officers, as well as the number of officers willing and eager to work off-duty, the ways officers are matched with employers have been evolving. Those methods now include:

Self-placement—Individual officers secure off-duty work directly from employers, the most basic method that has been popularized over the years as “moonlighting.”

Peer recruitment/placement—Particular officers broker and coordinate a number of off-duty jobs, which may include helping outside employers determine security needs, recruiting fellow officers for off-duty jobs, arranging off-duty work schedules, managing payrolls and often collecting fees for their placement services.

Union recruitment/placement—A union representing officers in an agency maintains job listings and matches officers with positions, usually according to a scheme that distributes available work equitably among interested officers.

Agency recruitment/placement—The police agency brokers and coordinates off-duty work by officers, fielding requests from employers, assigning officers and vehicles, managing off-duty payroll and collecting commissions for these services.

The four categories above represent the major approaches but these are not mutually exclusive. Officers who contract individually with employers must, in most agencies, report and receive approval for off-duty work and, in some agencies, must also return a percentage of their off-duty pay to the police agency for being permitted to work in uniform and/or with an official vehicle. Similarly, officers who broker off-duty placements for their peers or union officials who manage the distribution of off-duty work to member-officers will, to varying degrees, coordinate with agency administrators regarding off-duty/on-duty scheduling of personnel and equipment, pay rates for off-duty work and staffing levels required for different “details,” as these officially-sanctioned, off-duty assignments are most often called.

Though our review will focus on the four categories set forth above, it is with the recognition that police off-duty employment continues to evolve and hybridize, creating new opportunities for corrupt activity and distortion of public safety services. As CitationGraycar (2015) notes, corruption opportunities are not fixed but arise from the dynamic interplay of behaviors, organizational activities and governmental sectors. This could not be truer of the many varieties of paid police details nested at the intersection of public, private and non-profit sectors.

3 Self-placement in secondary employment

With self-placement, an officer seeking a second job identifies off-duty employment opportunities, considers the work and pay involved, and then agrees to exchange his/her labor for wages paid by a given employer. This exchange can take place entirely off the radar of the officer's department or may involve the officer notifying the department and obtaining approval.

The issues raised for police agencies by individual labor agreements include questions concerning the integrity of the employer, the types of establishments in which officers work off-duty and the conduct of the officer in his/her off-duty employment.

Departments will most likely scrutinize the off-duty employment of individual officers when incidents occur or questions arise about employers. In 2009, the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department revoked the work permits of 51 officers employed off-duty at a scrap yard chain that was under grand jury investigation regarding the receipt and sale of stolen property. Among the officers whose permission was revoked was a senior metals theft investigator who, as a supervisor at the scrap yard, scheduled the 50 other officers who worked there, including the investigator's direct superior, a captain (CitationRyckaert, Evans, Nichols, Gillers, & Alesia, 2009).

The Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department offers an instructive snapshot of independently contracted police off-duty jobs. In the prior year, 57% of all officers (874) had at least one permit for off-duty work at nearly 900 employers. Employers ranged from taverns, to housing complexes to security firms as well as an Eli Lilly heiress and the owner of the Indianapolis Colts professional football team. Record keeping by the department was poor and only a few, loosely-defined off-duty work venues were off-limits (CitationRyckaert et al., 2009). Officers thus could work almost anyplace, as most did pursuant to departmental permission and as yet others almost certainly did on their own.

This Indianapolis self-placement snapshot illustrates aspects of police off-duty work that can be found in police agencies across the U.S., regardless of the administrative model used to place officers.

| • | Many officers are involved—here more than half the force. | ||||

| • | Substantial business relationships bind officers to particular external employers—the scrap metal business employed 3.4% of Indianapolis police officers. | ||||

| • | Off-duty police officers are a preferred security option for businesses where anti-social and criminal behavior have elevated probability—in Indianapolis, as in the U.S. generally, thieves use scrap yards to convert stolen metals to cash. | ||||

| • | Administrative structures staffed by officers often emerge to manage the volume and variety of off-duty placements—as with the Indianapolis police investigator who scheduled fellow officers for scrap yard shifts. | ||||

| • | Off-duty assignment scheduling is source of power and organizational influence for whomever performs that role—the off-duty income of 50 Indianapolis officers, including his Captain, depended on scheduling decisions made by a rank and file investigator at his off-duty job. | ||||

3.1 Clashing values in free-lance secondary employment

Off-duty jobs taken by free-lancing officers can also produce situations that leave their departments scrambling to explain why officers are working jobs that seemingly contradict values generally espoused by law enforcement agencies.Footnote2 In the 1990s, the investigation that eventually blossomed into LAPD's “Rampart Scandal” got rolling when certain officers in Rampart Division in South Central Los Angeles were found to be working off-duty, without departmental permission, as security for Death Row Records (CitationSullivan, 2002, p. 39). One officer reportedly boasted to LAPD peers on that he was making $250 an hour from such engagements (CitationSullivan, 2002, p. 34). LAPD investigators found some of these officers were active in the pricey LA-Las Vegas social circuit of West Coast rap record moguls and talent even when they weren’t providing these individuals with personal security. The most notorious of these officers, who were indeed living a “gangsta” life, were convicted of major felonies, and one of them, in effusive and suspect testimony arising from a plea deal, accused numerous fellow Ramparts officers of crimes (CitationKirk & Boyer, 2001).

LAPD officers were not alone in free-lancing off-duty in the rap music industry. When rapper Christopher Wallace, aka Biggie Smalls, was gunned down in Los Angeles in 1997, he was “under the protection of off-duty…officers” from Inglewood, an incorporated city contiguous to Los Angeles. The six officers involved received “punishments ranging from suspension without pay to written reprimands” because, according to an Inglewood Police Department superior, “Our policy requires that officers need prior approval for off-duty work, and these officers did not do that.” (CitationVanderpool, 2001)

In April 2003, off-duty Inglewood Unified School District Police Officers—same LA County city, different police force—were serving as bodyguards for rapper Snoop Dogg when “gunmen fired on his motorcade, wounding one reserve school officer.” Two months later, “two Inglewood school officers were in (Snoop Dogg's) entourage when Los Angeles and federal police confiscated a cache of weapons from its vehicles” (CitationHayasaki, 2003). The two episodes led the department's chief to remark: “There are jobs, obviously, that a police officer shouldn’t take, for example, as an armed officer guarding a convicted felon” (CitationHayasaki, 2003).

This Snoop Dogg case illustrates role conflicts that can arise between an officer's official job and his/her secondary employment, and underscores the potential of a flipped relationship, where the officer's official role becomes secondary to off-duty job opportunities.

The off-duty police officers in the two incidents involving Snoop Dogg worked for a small, low-prestige force that paid relatively little, particularly for its $13.50 an hour part-time reserve officers, two of whom were providing security to the Snoop Dogg entourage during the weapons seizure (CitationHayasaki, 2003). In Los Angeles country, demand for private, armed security was high and police officers could command premium off-duty pay of “hundreds of dollars a day.” (CitationHayasaki, 2003) Thus an important value officers derived from working on this particular police force came from the peace officer status the job conferred, which in turn raised their value to off-duty employers such as Snoop Dogg. As a lawyer representing several officers observed, “A lot of these officers have security businesses on the side. That is one of the reasons they become reserve officers, because it allows them to carry a gun. It allows them to make money on the side, while also [protecting] the community.” (CitationHayasaki, 2003) Notwithstanding their commitment to serving the community, the department terminated eight reserve officers after these incidents, including some who had not reported to work for several months (CitationHayasaki, 2003).

Entertainment figures are not alone in contracting with off-duty police officers for personal security. This paper noted earlier how off-duty Indianapolis officers provided security for an heiress, as well as the owner of a professional football team. Star athletes—iconic and recognizable to legions of fans—also employ high-quality security personnel, including off-duty officers. In 2010 when a young woman accused Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback Ben Roethlisberger of sexually assaulting her in an Atlanta, Georgia nightspot — no charges were ever filed — two Pennsylvania law enforcement officers he employed were present, allegedly buying drinks for the group, which included the accuser, who was underage. One officer worked for a Pittsburgh suburb that had few rules limiting off-duty work but the other officer was a Pennsylvania State Trooper whose agency did have rules. Although the trooper had in 2005 secured permission to work for Roethlisberger as a “personal assistant,” witnesses in Atlanta described both officers as behaving like bodyguards. The trooper, supported by the state police union, fought the State Police attempts to bar him from further employment with Roethlisberger, though the decision was later upheld by an arbitrator. State police officials did not, however, emerge unscathed. The arbitrator took note that the trooper, channeling “perks” provided by Roethlisberger, had arranged luxury suite accommodations for his superiors at Steelers’ games (CitationAssociated Press, 2011c).

The cases above highlight factors corrosive to both esprit de corps and managerial control in police agencies. Incentives operating in the self-placement off-duty market turn perverse when:

| • | Off-duty work is more lucrative than an officer's regular job, which occurred in the Los Angeles cases. | ||||

| • | Second jobs carry perquisites that amplify salary differentials between off-duty and on-duty work, such as all-expense paid trips to Las Vegas from Los Angeles or from Pittsburgh to Atlanta. | ||||

| • | Second jobs produce surplus perquisites for officers to distribute—skybox seats for police agency officials at major sporting events can produce inattentiveness to repeated work schedule adjustments coinciding with the secondary employment of the officer providing the tickets. | ||||

| • | Employment as a police officer becomes simply a means to gain employment as a high-priced bodyguard. | ||||

4 Peer recruitment and placement

Peer recruitment and placement occurs when particular officers in a police department broker and coordinate a number of off-duty jobs. This model was seen earlier with respect to Indianapolis, except there an officer while working as a supervisor in a private firm arranged the work schedules of 50 Indianapolis officers the company employed. A more common arrangement across the U.S. finds officers on police department time recruiting and scheduling their peers for off-duty placements, some of which may involve external job sites where the coordinating officer has a supervisory position. These placement services for officers frequently operate with agency approval but scant official oversight, particularly in regions with low police pay and high demand for private security by off-duty officers. Thus, there arises an informal system matching officers with second jobs that serves all parties by having few off-limits positions, accounting limited to hours/locations worked, rapid placements, satisfied business customers and, when necessary, a measure of deniability for police executives. Police agencies in and around the New Orleans metropolitan area are prototypical in this regard.

In southeastern U.S. states the locus of local power lies substantially with the county sheriff or, in the particular case of New Orleans, where the city and county are co-terminus, with the mayor. County sheriffs serve as the chief tax collector and provider of the broad range of public safety services. The demands for those services frequently exceed the budgeted manpower and resource capabilities of the sheriff's office or other local police agency, and dealing with the excess demand via overtime work is cost-prohibitive. Thus, agencies encourage secondary markets, where private entities pay for the “overtime” labor of officers. To further reduce costs borne by the police agency, off-duty details are then accounted for and supervised by individual officers. Though the details need to be approved by the agency and the shifts documented, most operational management responsibility falls on individual “detail supervisors.”

In some cases a detail arrangement is initiated by an outside entity seeking extra police services (e.g., a mall) via contact with the local police agency that, upon approval of the arrangement, assigns an officerFootnote3 to administer the staffing. Conversely, entrepreneurial officers can negotiate arrangements for security coverage with outside employers. These ad hoc deals must also receive approval from the agency for the details to officially be recognized; however, then the individual officer who negotiated the arrangement is assigned to be the supervisor.

With peer recruitment and placement, the police agency becomes a clearinghouse for officer placements in off-duty employment. It approves various “details” but does not administer their operation day by day. The detail supervisor is responsible for staffing the details; thus, he/she recruits other officers and manages the paperwork documenting their work hours. The paperwork is critical as the basis for calculating the agency's returns for the wholesale purveyance of its officers, because most agencies take a ‘cut’ for each off-duty hour officers work. While secondary employers pay officers directly, the agency extracts a fee for each off-duty hour worked directly from the officers’ regular paychecks. For liability purposes, both external employers and officers working off-duty have a vested interest in “detail work” that is on-the-record, officially sanctioned and even “taxed.” Courts in Louisiana have consistently held that neither the private employers nor the agencies and officers have any special liability, as long as the officers were acting under the ‘color of law.’ Should anything go wrong on a detail, the liable party thus becomes the jurisdiction employing those officers to deliver tax-funded public safety services (Citation“Benelli v. New Orleans,” 1984; “Harris v. Pizza Hut of Louisiana, Inc.,” 1984; “Wright v. Skate Country, Inc.,” 1999).

The complex organizational arrangements and power relationships produced by off-duty details can be illustrated by the uniformed officers patrolling Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport, a transit point for millions of visitors to Louisiana each year. Every officer at the airport is working a “paid detail,” regardless of rank or uniform worn (the airport straddles two counties, Jefferson and St. Charles, drawing uniformed coverage from the Sheriff's Office in each). Anyone from a chief of detectives to a volunteer reserve officer might be among the more than a dozen officers patrolling the terminals each shift, four shifts a day, seven days a week. And supervisors might be of any rank, high or low. Officers are eager for airport “details” since the pay is higher and many shifts are available so officers can easily sign on if they need extra cash.

The officer who supervises details has extra work but enormous power. The supervising officer, de facto, becomes a broker, negotiating who gets what shifts and when. In the administration of “details,” this is where the power lies.

The power of the officer supervising details also creates an important complication. Rank in policing matters a great deal. Authority starts at the top, with Chiefs and Sheriffs, and goes down through deputy chiefs, commanders, colonels, majors, captains, all the way to the officer just ‘released’ from his probation period for solo patrol. A ‘ranking’ officer gives orders and subordinates are expected to carry them out.

This hierarchy becomes inverted where off-duty details are pervasive, as is the case in New Orleans where “virtually every officer works a detail, wants to work a detail or at some point will have to rely on an officer who works a detail” (CitationDOJ, 2011, p. XVI). Here the central node from which power radiates is the officer coordinating a major detail. The coordinating officer may principally work patrol or specialized squads on regular assignment but gains power and influence from his/her relationships with external employers and a network of peers and superiors eager for off-duty work. In New Orleans, but not elsewhere, the outsized influence of detail supervisors has been curbed pursuant to a consent decree entered into by the city with the Justice Department in 2012 that established an Office of Police Secondary Employment intended ultimately to manage all off-duty placements. However, individual cases and particular practices in the New Orleans Police Department through 2013 remain among the most highly documented illustrations of detail system abuse.

The power inherent in off-duty detail supervision impacts the hierarchy of power within the police agency. The officers supervising details stand astride income streams most members of the force are eager to draw upon. As the Department of Justice observed with respect to New Orleans, “Between August 2009 and July 2010, 69% of all officers … submitted a request to work at least one detail. This number includes 85% of all lieutenants and 75% of all captains.” While this demonstrates that ranking officers are eager to work details and collect the extra income, they are less interested in being detail supervisors given their other administrative responsibilities. Thus, low-ranking officers running details are more the rule than the exception which, in turn, means that, in the informal economy of police details, bosses look to subordinates for off-duty jobs and may even report to those subordinates at off-duty work sites.

The 2011 Department of Justice report judged that the New Orleans Police Department's detail system was compromising the effectiveness and credibility of police services in multiple ways. Though conditions in New Orleans prior to 2012 were quite pronounced—leading to federal court supervision and monitoring for both the police department and sheriff's office—many police forces in the southeastern region of the United States, and elsewhere, administer details similarly and are thus susceptible to, if not in the grip of, issues identified in New Orleans by the Justice Department. Those issues include (CitationDOJ, 2011):

| • | Deploying over two-thirds of uniformed personnel in off-duty employment. | ||||

| • | Acceptance of chronically fatigued officers on regular police patrols. | ||||

| • | Diverting resources from primary policing to the management of details. | ||||

| • | Contributing to inequitable policing. | ||||

| • | Fostering corruption and abuse. | ||||

The chronic fatigue cited by the Justice Department was a natural outgrowth of the high number of officers working details; as well as the number of officers working all 28 off-duty work hours permitted each week, a limit that since has been reduced to 24 with stricter enforcement—since under the old regime some officers ended up working more off-duty than regular hours.

The fatigue issue, however, remains. It is quite often (and quite naturally, since there are only so many hours in a day) the case that officers must go straight from their off-duty detail to their regular police duties, or vice versa. In fact, at the time of the Justice Department report, some New Orleans officers clocked off-duty hours on lunch breaks, worked both before and after regular tours (for instance, providing traffic control for shift changes at a plant from 7–9 AM and 4–6 PM) or worked extended shifts with built-in breaks to attend to off-duty work (providing school security services prior to the opening bell and after dismissal).

In addition to creatively dovetailing on-duty and off-duty work schedules, Department of Justice investigators heard accounts of NOPD officers showing up for roll call and then reporting to their detail instead their regular NOPD assignments, leaving in the middle of investigations so as not to be late for their details and repeatedly working details on the same days as sick leave was taken (CitationDOJ, 2011, pp. 70–71)

In New Orleans, many of these scheduling abuses, as well as officers supervising their commanders on off-duty jobs, have been curtailed as a result of the consent decree. However, the ability for on-duty hours to be arranged to serve officers’ off-duty employment continues to exist in police departments where liberal leave policies enshrined in agency rules and/or collective bargaining agreements allow officers to exchange shifts and otherwise manipulate work schedules. Furthermore, schedule manipulation is but a symptom of the increasing value officers in general are placing on detail work, which in turn can flip the commitment of police officers so that the demands of their off-duty jobs become primary, and their official duties secondary. What William Bratton, who led the Los Angeles Police Department and twice served as New York City Police Commissioner, said in 1998 still applies.

“The idea is that after my tour of duty, I’m going to be going to my private employment. So I don’t want to make an arrest in the last couple of hours. So to many cops, their real job is the paid detail. The policing? That's their pension job” (CitationJones & Wiseman, 2003).

Pension plus benefits, one might add. Health insurance, paid sick and other ancillary benefits provided by the officer's regular job effectively cover most risks arising from off-duty work and limits the compensation costs to off-duty employers to wages alone. Employment transactions between off-duty employers and police officers, whether or not mediated by the police agency, also derive value from tax-funded elements such as the officer's training and his/her uniform, badge and equipment, including the police cruiser(s) integral to many off-duty details. The value of these public investments appears in the officer's off-duty paycheck; in the agency's commission or rebate and in the premium security services provided private employers.

4.1 Diversion of policing resources

Off-duty employment is clearly a significant portion of the time police officers collectively spend in uniform providing protective services. The NOPD's own analysis of details worked from December 2010 to April 2011 showed 31,000 shifts worked by 1100 officers and doesn’t capture off-duty work that is “off the books” or otherwise unreported (CitationNOPD, 2011). The Department of Justice report found that NOPD record-keeping for details made it impossible to determine if officers had exceeded the 28 off-duty work hours then permitted but did gather anecdotal evidence of officers “too tired to perform their duties on the street and in the courtroom” (CitationDOJ, 2011, p. 72). A public safety/private security ratio approaching 1:1 poses a public policy question of a high order: For whom do the police work?

Proponents of details assert they are a force multiplier. The view of many police chiefs and most police union officials is that officers detailed to escort a celebrity, guard a commercial establishment or control crowds at a sporting event can respond to critical incidents that require a police response. The visibility of uniformed officers in off-duty roles is also seen as having a deterrent effect. These claims have face validity and, indeed, officers will leave off-duty details to deal with observed criminal activity and any “officer needs assistance” call. However, the general deterrent effect of officers providing security services also depends on how large those officers loom in the eyes of potential miscreants. Thus, an officer outside a nightclub is likely a stronger deterrent than an officer working a movie set or sporting event.

The aggregate picture, however, is somewhat at odds with force multiplier notions. On a given tour, especially during periods when demand from private or other employers is high, more police officers may be employed by off-duty details than are on official patrol. A large police district in a mostly residential area may be covered by three or four single-officer patrols while miles away in the city's entertainment district dozens of officers are working off-duty details. As a matter of basic logistics, officers working details in the entertainment district are unavailable to assist in all but the most critical incidents their on-duty colleagues might encounter in the distant neighborhood.

The power of “details” to degrade delivery of official policing goes beyond logistics and critical incidents. Officers in general value detail work as both a personal and collective matter, which is why schedules are manipulated to facilitate details. Similarly, on-duty officers, sometimes with official sanction, may handle routine service calls in minimalist fashion to avoid backlogs that, combined with some critical incident, will likely to pull fellow officers from off-duty details. If avoiding this requires telling some citizens to file their report at the police district tomorrow, so be it.

4.2 Equity effects of the detail system

A municipal police agency, responding to a middle-class neighborhood's concern about an uptick in crime, asserts that conditions elsewhere in the city are more pressing, making an increase in regular patrols out of the question. However, the neighborhood community association is also advised that off-duty officers are available for patrol in full uniform, driving police cruisers, at a rate of $50 an hour. This raises the obvious question, expressed to one of the authors by a resident: “Why is Officer Jones, whose police salary our taxes help pay, unavailable to patrol our neighborhood during her regular tour but, when it ends, she is available to patrol our neighborhood for $50 an hour?” Footnote4

This real-life scenario from New Orleans underscores how details are transforming protective services provided by sworn police officers. Decisions about how to deploy officers relative to the citywide or countywide distribution of crimes and calls for service begin to factor in ability to pay—a notion at the confluence of providing public safety as a public good and selling safety services as a commodity.

The detail system commodifies police services. Off-duty employers pay varying wages, with some employers bidding higher than others and also because the police may charge more for certain services. In New Orleans presently, under the reformed system administered by the Office of Police Secondary Employment, sergeants, lieutenants and captains earn higher wages than officers, everyone gets a $17 an hour premium on holidays and ‘days of high demand’ and “super users” who employ officers for more than 100 hours per pay period get a discounted rate. This new system continues some differential pricing from the old regime, such as rank differentials in off-duty pay, but dispenses with others that were highlighted by passage below from the Department of Justice's 2011 report.

With poor documentation, no restrictions on officers soliciting work, and officers being allowed to negotiate their own compensation, it is easy for officers to extort businesses or individuals. We heard, for example, of many instances in which officers insisted on exorbitant sums of money, often in cash, for motor escorts. We learned of one instance in which officers told a business owner that if the business owner did not hire certain officers at a particular rate, the business would not receive any police protection from NOPD. The business owner reportedly was told, “You f*** with me and you will never see a police car again.” When the business owner tried to speak to a supervisory officer about the issue, the supervisory officer told the business owner that there was nothing the supervisory officer would or could do about the threat. Because of the perceived need for the additional security, the business owner relented and hired the officers he was told to hire at the rates demanded. (CitationDOJ, 2011, p. 72)

Differential pricing for off-duty police services set the stage for predicating the delivery of police services to certain communities on the ability to pay. An upscale neighborhood or gated community enunciating a need for more police services became a sales target for paid police services provided by off-duty officers. No need for the extortionate hard sell documented in the Justice Department report, just an advisory to the community that, while no regular patrols were forthcoming, officers who could provide equivalent protection were available for rent.

The Justice Department concluded that the NOPD detail system as it was operating before 2011 inequitably distorted the delivery of police services. According to the CitationDepartment of Justice's Civil Rights Division (2011, p. 73), “the breadth and prevalence of the detail system has essentially privatized officer overtime at NOPD, resulting in officers working details in the areas of town with the least crime, while an insufficient number of officers are working in the areas of New Orleans with the greatest crime prevention needs. Those with means in New Orleans are essentially able to buy additional protection, while those without such means are unable to pay for the services and extra protection needed to make up for insufficient or ineffective policing.”

New Orleans is not unique. Any department where many officers work off-duty in uniform will skew police in public view toward commercial and institutional establishments, with a number of officers patrolling business districts on regular tour while others work at individual businesses as secondary employment. Many financial institutions employ police details to deter crime but also out of concern for terrorism and protest. Terrorism fears result in off-duty details of officers at institutions that are nearly crime-free, such as the New York Stock Exchange (CitationProtecting Our Financial Infrastructure, (Testimony of Robert Britz, President of the New York Stock Exchange), 2004). Protests against financial sector employers place off-duty officers in a bind regarding the role of the police in a free society. Confrontational protests pit officers against individuals claiming their rights to assemble, petition and speak freely, which occurred in Dallas when a protester orating from atop a planter on Bank of America property was pushed from his perch by an officer working off-duty for the bank. The Dallas Police Department suspended the officer without pay for a day and also barred him from off-duty work for two-months (CitationAssociated Press, 2011a). The debarment from off-duty work likely carried a far more significant financial penalty than the suspension.

4.3 The corruption of police services

The New Orleans Police Department's approach to police details produced a series of scandals, ranging from corrupt practices to profiteering that, while not illegal, violated departmental policies and fueled the image of the department as a place where “anything goes.”

Red Light Cameras in New Orleans: This technological breakthrough has been adopted by many jurisdictions to raise traffic enforcement productivity substantially above what officers on patrol can achieve. In Louisiana, sworn officers must attest to the photo evidence, just as an officer on patrol signs off on a ticket for running a red light. The New Orleans Police Chief, however, declared in 2010 that on-duty officers could not be spared to review red light camera evidence. The answer? A detail staffed by off-duty officers, coordinated by the then-commander of the 8th District of the New Orleans Police Department, who “formed a Limited Liability Company called Anytime Solutions through which he managed the aforementioned detail … in violation of NOPD policy” (CitationOffice of Police Secondary Employment City of New Orleans, 2015; Quatrevaux, 2013).

The Incorporated Detail: A 2012 ruling by the New Orleans Civil Service Commission upheld the three-day suspension of a Captain, who had formerly led the Homicide Division, and a Lieutenant, each of whom had formed corporations to handle administrative and liability issues regarding details they separately coordinated. The details were major operations, each with annual revenues approaching one million dollars, so the private employers, including the Marriot Corporation, wanted the indemnification and accountability assurances that came with dealing with corporate counterparties, in this case the Captain and the Lieutenant (CitationCivil Service Commission City of New Orleans, 2012). When the Captain appealed the Civil Service Commissions findings and penalties, which included a six-month debarment from detail work, the Louisiana Court of Appeal found that incorporated police officials operating officer placement services for a fee had a “real and substantial relationship to the efficient operation of the department” and upheld the Civil Service Commission's sanctions against the Captain (Citation“Waguespack v. Dept. of Police,” 2013).

Payroll Fraud: In November 2013 federal prosecutors obtained indictments against two New Orleans narcotics officers for payroll fraud that entailed charging the NOPD and an off-duty detail employer, the federally subsidized senior housing development known as Guste Homes, for the same hours worked (CitationDall, 2013). The officers pled guilty in February 2014 (CitationLinderman, 2014).

The charges spotlighted practices in the Guste Houses paid detail that, despite the New Orleans provenance, are emblematic of the service delivery distortions, integrity threats and managerial disarray that can afflict police agencies with ad hoc paid detail systems. The detail cost the public housing complex at least $432,000 in 2010. Several officers, including two sergeants, indicated on reporting forms that the detail was coordinated by the police officer who served as the police department's liaison to the complex during his regular shift and also worked there off-duty most nights. Though the officer denied, through his attorney, any supervisory role, his ubiquitous presence at Guste led most residents to view him as in charge—this for an officer who had both saved his own job and escaped prosecution for payroll fraud several years earlier by entering a diversion program after admitting to working off-duty for a major drug store during hours he was getting paid by the NOPD.

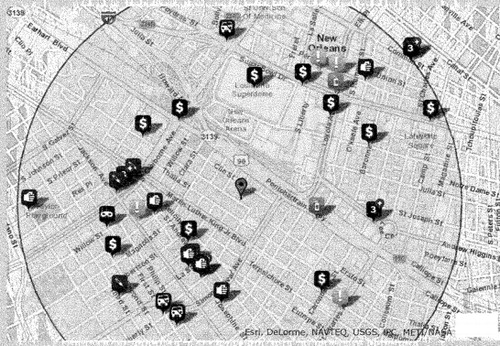

The map above, from November 2013, shows crimes then occurring around the Guste Homes—the center point on the map. Crime was staying away, which is also what elderly residents and staff saw. As one former maintenance supervisor remarked, “There's no trouble over there at all. Never. Never. They (the detail officers) never handle anything going on over there” (CitationPerlstein, 2013) ( )

Illustration 1 Crime At Guste Homes (CitationThe Omega Group, 2013).

The ad hoc, peer managed secondary employment system was one reason the New Orleans Police Department was subject to external monitoring under federal court supervision. The consent decree addressed most of the problematic elements discussed so far in this paper but also mandated one overarching, structural change: the establishment of an Office of Police Secondary Employment outside the police department to manage all off-duty work by officers. Thus, the thriving enterprise of police secondary employment was institutionalized by judicial fiat in New Orleans. In many other U.S. jurisdictions, however, police departments and/or police unions had already moved to centralize the management of police secondary employment.

5 Institutionalizing off-duty placements

The changes forced on the New Orleans Police Department have occurred organically in police departments across the U.S. Police department management of off-duty employment is driven by managerial and financial factors that police chiefs and jurisdictional executives find compelling. These include:

| • | Minimizing negative publicity arising from “moonlighting cop” stories. We referred earlier to Indianapolis off-duty officers working at junkyards implicated in trafficking stolen goods. Given the breadth of police off-duty employment, such occurrences are inevitable and headline-worthy, as attested by the Chicago officer allegedly “lube-wrestling” while providing security at a gay nightclub (CitationMain, 2012), the Houston officer working after-hours as rapper “Lucille Baller” (CitationAssociated Press, 2012) or the Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania officer working an off-duty detail outside a bar who was photographed having his badge licked by a young woman (CitationWadell, 2013). | ||||

| • | Avoiding employee grievances over loose or non-existent rules concerning outside employment. New Orleans officers who had incorporated to better run lucrative placement operations spent years fighting departmental sanctions at the Civil Service Commission and in the courts, contending that they had violated no rules (Citation“Waguespack v. Dept. of Police,” 2013). | ||||

| • | Reducing complaints about favoritism and inequity. Ad hoc placement systems that are opaque and tied to particular officer networks arouse suspicions that are allayed by transparent departmental placements with fixed wages and rotating opportunities among interested officers. | ||||

| • | Clarifying the legal status of officers employed off-duty. In most states officers working off-duty are within the scope of their public employment when subduing, detaining or arresting individuals. Lawsuits still may succeed in showing excessive force and inappropriate exercise of authority by off-duty officers, or failures to respond to crimes, at the behest of commercial employers. Thus, for police chiefs, municipal attorneys and their insurers, agency management of off-duty details is a way of better controlling and legitimizing officer behavior in such situations (CitationBreads, 2012). | ||||

| • | Generating income. Cash-strapped agencies and jurisdictions seek out additional revenue sources. Commissions and fees from officer placements can be substantial. A single “incorporated” detail coordinator in New Orleans was taking a 10% fee from nearly one million dollars in annual revenue. In many larger police agencies, a 10% fee, which is standard in many departmentally managed off-duty programs, can bring in millions. | ||||

Factors that fuel corruption and resource diversion in self-placement and peer-placement persist when agencies take over the assignment of officers to secondary employment. Police agency executives have a financial interest in growing the detail business. Organizational harmony may be better served by satisfying officers’ demands for off-duty work, despite any resultant on-duty fatigue. Aggressive marketing of detail services may produce rent seeking as police executives, often in league with union representatives, lobby for laws or promulgate regulations that freeze out competitors in the security services market. Finally, the substantial monies involved, often processed through new or unsettled administrative arrangements, can induce illegal behavior by police executives, as was the case in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

The Pittsburgh police chief pled guilty in 2013 to federal conspiracy and other charges involving the diversion of “$70,628 in public funds paid to the bureau by private entities for the services of off-duty police.” (CitationLord, Navratil, & Silver, 2013) The source of the diverted funds was the $3.85 paid by private employers for every off-duty hour worked by officers. The agency's personnel office deposited these funds, at the chief's direction, in a Greater Pittsburgh Police Federal Credit Union account that could be drawn upon with debit cards held by the chief and his associates. The chief was subsequently sentenced to 18 months in prison and ordered to pay restitution (CitationLord, 2014). Separate from that case, a report commissioned by the city criticized the chief for his involvement in Diverse Public Safety Consultants LLC, a security consulting firm he helped form and, along with other members of the force, worked for while serving as chief (CitationLord et al., 2013).

Pittsburgh's new police chief sought to clean up the off-duty employment program with several reforms including barring off-duty officers from working in sex-themed establishments. One of those establishments, Blush Gentlemen's Club, sued the city, cheered on by the police officers’ union, which announced its own grievance to keep cops employed by clubs like Blush (CitationMoye, 2013). Blush prevailed in federal court and was due reimbursement for $25,000 in legal fees, while the union leveraged the contretemps into negotiations with the city over off-duty employment generally (CitationBauder, 2013).

Unions representing police officers across the U.S. naturally have strong interest in maximizing members’ returns from off-duty employment. In Pittsburgh, another union grievance unsuccessfully sought parity between on-duty officers and off-duty officers, who were making 50% more when policing the same major events (Citation“City of Pittsburgh v. Fraternal Order of Police Fort Pitt Lodge No. 1,” 2014). The collective bargaining agreement in Taunton, Massachusetts, a state where most off-duty employment is agency-managed, spends 6 of 50 pages on the assignment of officers to details (CitationCity of Taunton, 2014). In Washington state, the Seattle Police Officers Guild spun-off to a private firm the job of assigning officers to details on the grounds that “the volume of business became too much.” (CitationSeattle Security, Inc., 2015) However, the directorates of both the union and the private firm remain interlocked, with the President, Vice-President and Secretary/Treasurer of Seattle Security also serving as directors of the Seattle Police Officers Guild as 2015 began (CitationSeattle Police Officers Guild, 2015; Seattle Security, 2015).

Beyond the occasional public official who may disgrace him or herself by embezzling proceeds from agency and/or union-directed police off-duty employment, institutionalizing secondary employment as an official agency function, whether or not further codified by collective bargaining, raises critical public policy issues to which we will now turn in concluding this paper.

6 Institutionalized rent-seeking

This paper has progressed from officers individually securing off-duty work, to ad hoc systems where officers coordinate off-duty placements for peers and, finally, to institutionally-managed secondary employment where agencies, and sometimes unions, run the growing business of private security provided by uniformed officers.

Even as the ways officers obtain off-duty employment moves from individual to more corporate forms, a strong commonality of interest continues among all the parties involved on the police side of the employment equation. More off-duty work at higher salaries is a compelling proposition to individual officers seeking premium off-duty wages, precinct entrepreneurs profiting from off-duty placements, union officials parceling out bonus assignments and police officials calculating the commissions earned from “details.”

The consequence is that police departments, along with police unions, are strongly motivated toward rent seeking behavior in order to capture a larger share of the overall market for security and safety services.

As CitationHenderson (2008) puts it: “People are said to seek rents when they try to obtain benefits for themselves through the political arena. They typically do so by getting a subsidy for a good they produce or for being in a particular class of people, by getting a tariff on a good they produce, or by getting a special regulation that hampers their competitors” (see also: CitationKreuger, 1974; Lockard & Tullock, 2001; Tullock, 1993).

Police departments seek rents by working in the political arena to craft regulations that hamper, and even eliminate, competing security and safety services. This is accomplished through local laws mandating that police officers be used for certain activities, such as traffic control at road projects. Thus, in towns with such laws, both the asphalt firm filling potholes and the arborist trimming branches must employ a uniformed officer to flag pedestrians and vehicles around the activity.

Massachusetts is one of many states whose laws enable local police agencies to corner the market, and even create markets, for protective services. In Taunton, south of Boston, the collective bargaining agreement specifies that officers “shall be assigned to extra paid details … where required by ordinance or statute. In addition, the Chief of Police or his designee shall require that one or more police officers be assigned on an extra paid detail whenever there is work being performed on or near a public street or sidewalk which may obstruct either the flow of traffic or the view of either motorists or pedestrians, block the path of pedestrians or create a hazard to motorists and/or pedestrians” (CitationCity of Taunton, 2014).

Such requirements in local laws and regulations throughout Massachusetts have made private flaggers an endangered species (CitationFord, 2011), even though state law allows them on state projects. The law, however, allowed localities to keep and add prohibitions, which could be energetically enforced, as a civilian flagger at a Boston construction site learned. She was first threatened with arrest, and then watched her bosses meet with the lieutenant who first spotted her, plus “the district captain … two superintendents … (and) … at least three union representatives” (CitationCramer, 2010). The next day she hauled materials around the site as a detail officer stood traffic watch.

Rent-seeking police departments may even structure rules allowing them to create markets for off-duty details where none may have existed. In Taunton, the collective bargaining agreement provides that,

… whenever there are persistent reports of problems at cafes, clubs, pubs, taverns or similar establishments or at restaurants or eating establishments, including so-called “fast food” establishments operating without police officers on extra paid details, either the Chief or the Association may submit written notification of such persistent problems to the Licensing Commission. The Licensing Commission shall then hold a hearing within thirty (30) days … on the question of whether and under what circumstances one or more police officers shall be required to be present on an extra paid detail at any such establishment as a condition of maintaining its license. (CitationCity of Taunton, 2014).

And, finally, as for state highway projects that might be using civilian flaggers, the Taunton agreement called for an “Extra Paid Detail Officer” if the agency's detail hiring supervisor and the union head determined that protection at a state project needed to be augmented.

In Taunton, as in many cities in Massachusetts and elsewhere, the market for off-duty officers is being ring-fenced against competitors and expanded almost at will, with the contract giving even retired officers a place in the queue should more jobs be generated than active officers can handle. Police secondary employment, in this most highly organized form, may well transform policing from a public service to a fee-seeking business, a transformation whose ramifications have been little considered as the growth of details has proceeded apace largely under the radar.

7 Conclusion

A United States Appeals court ruling in April 2015 upheld the reform of police details in New Orleans and, as the ruling relates to this paper, underscored key reasons for moving away from an unregulated system of off-duty placements. The plaintiffs were two New Orleans police officers who were among the last coordinators of one-off police details for weddings, block parties and similar events. Recurring hourly details had already been taken over by the new Office of Police Secondary Employment and the ad hoc details were next up, which would end the long-standing system of powerful officer-coordinators. Another party to the suit was the Fraternal Order of Police of New Orleans, which happened to be led by one of the officer plaintiffs, who thus was advancing both his own interests as a detail coordinator and the collective interests of his member officers relative to off duty employment.

The court issued a ringing rejection of the plaintiffs’ claims in an opinion by Judge Edith Brown Clement (Citation“Powers v. United States,” 2015). She wrote that “a significant and legitimate public purpose” had been served by dismantling and replacing the New Orleans Police Department's detail system. This public interest outweighed plaintiffs’ claims that their rights to freely contract had been abridged and that the Office of Police Secondary Employment Office constituted governmental entry into a private market. The three judge panel thus came down on the side of a system of officer off-duty placement that,

| • | Made officers’ public agency service primary | ||||

| • | Directed proceeds from off-duty officer placements to the public purse | ||||

| • | Operated transparently and equitably in distributing work opportunities | ||||

| • | Centralized disparate systems riddled with self-dealing and conflict of interest. | ||||

The New Orleans detail system—that “aorta of corruption”—has very much been the canary in the coalmine. Corrupt and institutionalized placement practices had left the New Orleans Police Department teetering ethically, which the U.S. Department of Justice investigation could neither miss nor ignore. The result was thoroughgoing reform under federal court supervision. As this paper has made plain, however, New Orleans may be case zero but police agencies across the U.S. are also afflicted. For these agencies, the principles bulleted above provide a framework for reform.

The rise of the paid detail in all its forms has profound implications for policing and deserves more research. Understanding more about this phenomenon's potential for corruption and the distortion of policing is critical.

Notes

* This paper owes a special debt to students in the Master of Public Administration Program at John College of Criminal Justice who examined police details in different regions of the U.S. for a class assignment. Several students then joined Dr. O’Hara on a panel entitled “Collaboration, Communion or Coercion: The Case of Police Details” at the 2014 Northeast Conference on Public Administration. So special thanks to Michael Bensimon, Theresa Middleton, Bieu Tran, Julia Von Ferber and Natalie Wenzler, who were panelists, and also to Jason Brazie, Alex Lomvardias, and Juan Nolasco.

1 Hereafter these terms will all refer to “secondary employment”.

2 This very notion is embedded with an inherent paradox concerning the need for agencies to oversee their own governance and the weak incentives to effectively do so in this matter. For related discussions see CitationFritzen (2005) and CitationPeters (2014).

3 “Officer” is a general term; in this regard an “officer” can be anyone from a deputy chief to a entry level officer.

4 This scenario is drawn from a conversation one of the authors had with two New Orleans residents whose community faced exactly this situation.

References

- Associated Press . Suspension: Officer Pushed Occupy Dallas Protester. 2011. http://www.kbtx.com/home/headlines/Suspension_Officer_Pushed_Occupy_Dallas_Proteste_135733808.html (accessed 03.11.13).

- Associated Press . Trooper Ed Joyner loses appeal. ESPN NFL. 2011 May 26. http://sports.espn.go.com/nfl/news/story?id=6587817 (accessed 01.11.13).

- Associated Press . Dallas cop caught moonlighting as gangsta rapper ‘Lucille Baller’. 2012. http://thegrio.com/2012/11/29/dallas-cop-caught-moonlighting-as-gangsta-rapper-lucille-baller/ (accessed 03.11.13).

- B. Bauder . Blush strip club's plea for return of off-duty Pittsburgh officers goes to federal court. Pittsburgh Post Gazette. 2013. http://triblive.com/news/adminpage/3745724-74/blush-club-kamin-axzz3OgWO6by4 (accessed 09.01.15).

- Benelli v. New Orleans, 478 So. 2d 137 (La.App. 4 Cir. 1984)..

- J.F. Breads . Is The Devil in Paid Police Details?. 2012; 12–13. http://www.policechiefmagazine.org/magazine/index.cfm?fuseaction=display_arch&article_id=2640&issue_id=42012 (accessed 12.01.15).

- City of Pittsburgh v. Fraternal Order of Police Fort Pitt Lodge No. 1, No. SA13-01109 (Allegheny County Court of Common Pleas 2014)..

- City of Taunton . Collective Bargaining Agreement between the City of Taunton and the Taunton Police Patrolmen's Association. 2014. http://www.taunton-ma.gov/pages/tauntonma_mayor/S022F0120-04925A9F.6/COTMA Contract.pdf (accessed 09.01.15).

- Civil Service Commission City of New Orleans . Joseph Waguespack VS, Department of Police, Docket Number 7904. 2012

- M. Cramer . Police Turn Up Heat on Civilian Flaggers. Boston Globe. 2010 April 22. http://www.boston.com/news/local/massachusetts/articles/2010/04/22/police_turn_up_heat_on_civilian_flaggers/ (accessed 12.01.15).

- T. Dall . FBI arrests two NOPD officers for alleged payroll theft and wire fraud. 2013. http://www.wwltv.com/story/news/2014/09/04/14626552/ (accessed 09.01.15).

- DOJ . Investigation of the New Orleans Police Department. 2011; United States Department of Justice [DOJ] Civil Rights Division.

- B. Ford . Use of civilian flaggers on road projects is not exactly booming business. South Coast Today. 2015 September 25. http://www.southcoasttoday.com/article/20110925/News/109250326 (accessed 12.01.15).

- S. Fritzen . Beyond “political will”: How institutional context shapes the implementation of anti-corruption policies. Policy and Society. 2005; 24.

- A. Graycar . Corruption: classification and analysis. Policy and Society. 34(2): 2015

- Harris v. Pizza Hut of Louisiana, Inc., 445 So. 2d 756 (La.App. 4 Cir. 1984)..

- E. Hayasaki . Curbs urged on off-duty police jobs. Los Angeles Times. 2003 August 26. http://articles.latimes.com/2003/aug/26/local/me-inglewood26 (accessed 30.12.14).

- D.R. Henderson . Rent Seeking. The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. 2008. http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/RentSeeking.html (accessed 29.12.14).

- A. Jones , R. Wiseman . Ethics alert: Police detectives with a conflict of interest. Los Angeles Times. 2003 December 7. http://www.lacp.org/Articles-Expert-OurOpinion/031206-EthicsAlert-AJ.html (accessed 02.01.15).

- M. Kirk , P.J. Boyer . LAPD blues. 2001; PBS: Frontline

- A.O. Kreuger . The political economy of the rent-seeking society. American Economic Review. 64 1974; 291–303.

- J. Linderman . Two New Orleans police officers plead guilty in theft, fraud conspiracy. The Times Picayune. 2014 February 13. http://www.nola.com/crime/index.ssf/2014/02/two_nopd_officers_plead_guilty.html (accessed 09.01.15).

- A.A. Lockard , G. Tullock . Efficient rent-seeking: Chronicle of an intellectual quagmire. 2001; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston

- R. Lord . Former Pittsburgh chief Harper gets 18-month prison sentence. Pittsburgh Post Gazette. 2014 February 26. http://www.post-gazette.com/local/city/2014/02/25/Former-Pittsburgh-police-chief-Nathan-Harper-sentenced/stories/201402250123 (accessed 09.01.15).

- R. Lord , L. Navratil , J.D. Silver . Pittsburgh's ex-chief pleads guilty in federal court. Pittsburgh Post Gazette. 2013 October 19. http://www.post-gazette.com/city/2013/10/19/Pittsburgh-s-ex-chief-pleads-guilty-in-federal-court/stories/201310190157 (accessed 09.01.15).

- F. Main . Chicago cop fired for ‘lube wrestling’ and moonlighting as bouncer. Chicago Sun-Times. 2012 November 19. http://www.suntimes.com/news/16494907-418/chicago-cop-fired-for-lube-wrestling-and-moonlighting-as-bouncer.html (accessed 09.01.15).

- D. Moye . Blush strip club sues for right to hire off-duty officers. The Huffington Post. 2013 April 2. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/04/02/blush-strip-club-sues-for-right-to-hire-cops_n_2999602.html (accessed 09.01.15).

- NOPD . Reforming paid details. 2011; New Orleans Police Department [NOPD]: New Orleans

- Office of Police Secondary Employment City of New Orleans (2015). http://www.nola.gov/opse/ (accessed 04.01.15)..

- M. Perlstein . Tower of trouble: Main cop in housing complex has troubling history. 2013. http://www.wwltv.com/videos/news/local/investigations/mike-perlstein/2014/09/04/14631154/ (accessed 09.01.15).

- B.G. Peters . Is governance for everybody?. Policy and Society. 2014; 33.

- Powers v. United States, 14-30444 (5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals 2015)..

- Protecting Our Financial Infrastructure, (Testimony of Robert Britz, President of the New York Stock Exchange), U.S. House of Representatives, 108th Congress Sess. (2004)..

- E.R. Quatrevaux . Report of Inquiry into the Selection of New Orleans Police Officer Edwin Hosli to Coordinate the Red Light Camera Detail. 2013; Office of Inspector General: City of New Orleans

- V. Ryckaert , T. Evans , M. Nichols , H. Gillers , M. Alesia . Star review finds IMPD officers’ part-time gigs are poorly monitored. Indianapolis Star. 2009 June 28. http://archive.indystar.com/article/20090628/NEWS14/906280402/Star-review-finds-IMPD-officers-part-time-gigs-poorly-monitored (accessed 09.01.15).

- Seattle Police Officers Guild . SPOG Board of Directors. 2015. http://www.seattlepoliceguild.org/?zone=/unionactive/view_page.cfm&page=Board20of20Directors (accessed 12.01.15).

- Seattle Security . Website: Seattle Security Inc. 2015. http://www.seattlesfinestpstc.com/index.html (accessed 12.01.15).

- R. Sullivan . LAbyrinth: a detective investigates the murders of Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G., the implication of Death Row Records’ Suge Knight, and the origins of the Los Angeles Police scandal. 1st ed., 2002; Atlantic Monthly Press: New York

- The Omega Group . Crime at Guste Homes. 2013. http://www.crimemapping.com (accessed 10.11.13).

- G. Tullock . Rent seeking. 1993; Aldershot/E. Elgar: Hants, England/Brookfield, VT, USA

- T. Vanderpool . Does it pay for police officers to moonlight?. Christian Science Monitor. 2001 January 9. http://www.csmonitor.com/2001/0109/p4s1.html (accessed 10.12.14).

- B. Wadell . Police investigate racy photos of woman posing with moonlighting cop. WNEP—The News Station. 2013 May 13. http://wnep.com/2013/05/08/police-investigate-racy-photos-of-woman-posing-with-moonlighting-cop/ (accessed 20.12.14).

- Waguespack v. Dept. of Police, 119 So. 3d 976 (La.App. 4 Cir. 2013)..

- Wright v. Skate Country, Inc., 734 So. 2d 874 (La.App. 4 Cir. 1999)..