Abstract

Offices of Inspectors General (OIGs) promise increased accountability from governmental actors. OIGs do so by monitoring governmental programs and operations and providing their findings to legislative or executive decision makers and/or the public. These offices have enjoyed a particular popularity in the United States in the last 40 years; however a close examination of these OIGs demonstrates that, particularly on the state and local levels, there is vast variation in their designs. Using both original qualitative and quantitative data this paper examines the extent to which OIGs on the state and local levels vary from an archetypal OIG. The paper demonstrates that while design variations occur as the new institution is adopted in new places, sometimes deviations from the archetype are attributable to an intentional effort, based on a recognition of and reaction to the potential power of an OIG structured according to a theoretically ideal model, to restrict the office in ways that have the potential to undercut effectiveness.

In the United States, government accountability has become a constant concern, or even an “obsession” (CitationDubnick & O’Brien, 2011) of elected officials, citizens and public managers alike (CitationDubnick & Frederickson, 2011a). Offices of Inspector General (OIGs) have emerged as one solution many policymakers have gravitated toward in order to address this concern. This bureaucratic unit, originally established in a military context, has spread across the country and through federal, state, and local levels of government. While virtually none existed in a civilian context before 1976, now two-thirds of the 50 states and many localities have these offices.

Given this explosion in numbers of OIGs, one might assume that policymakers are committed to increased government accountability. Yet a close examination of these OIGs, particularly on the subnational level, demonstrates a wide variation in how they are organized, what authority they have, and which activities they pursue. This variation demonstrates policymakers’ ambivalence to issues of accountability, as data collected by the author show that design components deemed essential for an archetypal OIG are often altered. In some cases, there appears to be a deliberate debilitation of the structure of new OIGs, which reveals that policymakers may be of two minds about the OIG concept and accountability in general.

1 Materials and methods

This study employs a mixed methods approach, using both quantitative and qualitative data to inform the conclusions. The preliminary step was to identify existing state and local OIGs, as this data had not yet been compiled by any source. The OIGs were identified through a series of database and internet searches, including Lexis Nexis (looking for any state statute or regulation that mentioned an IG), state websites (such Kansas.gov), Google and Bing (searching for the name of the state and the term “inspector general” in the same document), and the membership lists of the National Association of State Auditors, Comptrollers, and Treasurers, and of the Association of Inspectors General (AIG).Footnote1

A search for OIGs yielded a total of 159 of these units, including 109 (69%) at the state level, 47 (29%) OIGs at the local level, and three (2%) multijurisdictional OIGs. From each of these OIG, data was collected through a combination of an on-line survey, using Qualtrics electronic survey software, follow-up telephone interviews, and a review of OIG websites. In the online survey, a number of questions about the offices’ formation, activities, and evolution were asked.Footnote2 A total of 59 OIGs responded to the survey, for an overall 37% response rate, comprising 42 (71% of 59) responses from state-level OIGs (including the OIG for Washington, DC), 16 (27% of 59) responses from local-level OIGs, and one (2% of 59) multijurisdictional OIG. The survey data was supplemented with website reviews and telephone calls to the OIGs that had not responded to the survey; however, not all of the information addressed via the survey was collected, but rather, just basic facts about these OIGs, such as the date of their creation and their key design features, were captured. This resulted in basic information for 91 OIGs, which, when combined with the 55 full survey respondents, yielded data from 150 OIGs, or 94% of the total, including 103 (69% of 150) state OIGs (including the Washington, DC, OIG), 44 (29% of 150) local OIGs, and three (2% of 150) multijurisdictional OIGs.

Additionally, semi-structured interviews, both in person and by phone, were conducted of 35 IGs, two deputy IGs, and one general counsel to an agency subject to OIG oversight. These interviews were conducted in eight states: Colorado, Florida, Illinois, Indiana, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Virginia. States were selected to maximize variation on key variables of: (1) corruption, measured by the average annual number of federal public corruption convictions from the state from 2002 to 2011; (2) size of government, measured by state and local FTE per 1000 of state population for the year 2010 from the CitationUS Census's Census of Governments (2010a, 2010b); and (3) political culture, measured by the Ranney index of partisan dominance in each state's governing institutions (CitationRanney, 1976). The data obtained from each interview was augmented with a review of the following: the OIG's website, any statutory provisions and legislative history, and a review of related news articles, collected from the America's News database, the New York Times, and the Chicago Tribune. These documents along with the transcripts of the interviews were coded in Atlas.ti, a qualitative analysis software.

1.1 What is an office of inspector general?

In order to understand what an OIG is and its role in government accountability, it is important to understand government accountability itself. Accountability, as the term will be used in this research, is “a relationship between an actor and a forum, in which the actor has an obligation to explain and to justify his or her conduct, the forum can pose questions and pass judgment, and the actor may face consequences.” (CitationBovens, 2007). In the governmental context, the actor is a government official, and the forum is an entity, or entities, with authority to direct the actor or otherwise impose consequences, such as a chief executive, a legislative body, a court, or the public.

An OIG is a bureaucratic unit dedicated to helping hold governmental actors accountable by providing unbiased information about the governmental actor's conduct to the relevant forum. OIGs typically are set up to oversee a particular government agency or, sometimes, multiple agencies within a designated jurisdiction. Commonly, OIGs are independent of the agencies they are charged with overseeing, so that their oversight is not influenced by the agency being overseen. (As we shall see, state and local OIGs vary considerably in this degree of independence.) An OIG provides accountability by monitoring the agency or agencies under its jurisdiction and producing reports about agency programs and operations, identifying problems, and making recommendations for fixing these problems (CitationLight, 1993). An OIG's jurisdiction usually extends beyond monitoring the actions of public employees to include the actions of public contractors and beneficiaries of public programs. Monitoring and reporting come in the form of audits and/or investigations. Often audits and investigations are initiated in response to complaints about the agency or agencies that the OIG oversees, but most OIGs also investigate or audit issues that are deemed problematic according to their discretion. Although OIGs commonly have broad powers of investigation and audit, they typically have no authority to prosecute criminal behavior or to require changes in the agency being overseen.

It should be emphasized that the role of the OIG, while not insignificant, is limited to collecting and analyzing information, whether through audits or other investigations, and then reporting the information to the forum. It is the role of the broader forum or forums—whether this be the chief executive officer of the agency in question, the mayor, the legislature, the governor, and/or the public, to decide what to do with this information: whether to demand change, issue a sanction, or impose some other consequence. If changes are to occur in response to problems identified by the OIG, others—the governor, legislature, mayor, or other official—must order them. As is discussed below, the nature of OIG's role is key to understanding the OIG archetypal model, which is an office theoretically best suited to play this role.

Since the creation of the first modern civilian OIG on the federal level in 1976, OIGs have been established across the United States and throughout all levels of government. Today, there are 73 OIGs in the federal government, in both the executive and legislative branches. Further, 31 states have established at least one OIG in an agency or for the state as a whole. Many large cities, such as Newark, New Orleans, Chicago and Albuquerque, and counties, including Miami-Dade County, Florida; Cuyahoga County, Ohio; and Montgomery County, Maryland, have also followed suit. OIGs can also be found in school districts and sheriff's offices. Although, as will be demonstrated, these OIGs are not identical in design, each of these jurisdictions has purposely established an office headed by an individual with the title of “Inspector General,” giving it a mission to pursue government accountability by collecting information about the actions of government employees or the use of governmental funds.

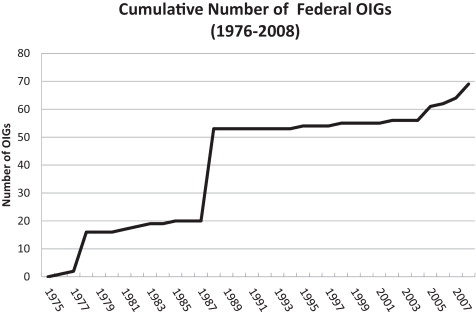

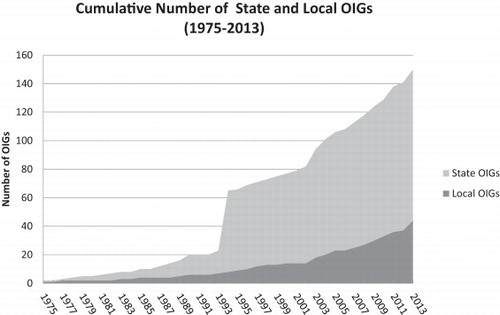

Figs. 1 and 2 show the growth in the number of civilian OIGs at the federal and subnational levels. The spike in the number of federal OIGs in the middle of is attributable to the 1988 amendments to the Federal Inspector General Act of 1978, which created a large number of OIGs in independent, regulatory bodies. A similar spike in the number of state OIGs in is a result of the passage of the CitationFlorida Inspector General Act of 1994, which placed an OIG in every state agency.

1.2 Literature review

Despite the widespread adoption of OIGs on all levels of government, to date there is very little scholarship on OIGs. With the exception of a focused study on corruption in New York City (CitationAnechiarico & Jacobs, 1996) and an article addressing the role of independence in OIG effectiveness (CitationSegal, 2010), discussed further below, the leading scholarship that exists focuses solely on federal OIGs and the implications of the passage of the federal IG Act of 1978, as amended (CitationApaza, 2011; Light, 1993; Newcomer, 1994, 1998). Although these studies, particularly Light's, provide insight into the federal OIG prototype, which provides a foundation for the OIG archetype, described more fully below, none of these studies examines the spread of the OIG concept to the subnational level, nor do they address the changes in design that are found in these OIGs.

CitationSegal (2010) presents the first foray into a comparative study of subnational OIGs in the United States. Similar to the present study, Segal's study examined varying structural independence among 10 state and local OIGs; however, unlike the present study, her research focused on the extent to which this independence impacts OIG effectiveness. This study, in contrast, focuses more narrowly on the creation and evolution of institutions and the extent to which subnational OIGs adhere to, or vary from, an archetype and why these variations have emerged. The issue of how OIG variations in structure impact the effectiveness of OIGs is beyond the scope of this article.

Putting aside issues surrounding the policy-making process related to when and under what conditions specific policies are adopted (see, e.g., CitationKingdon & Thurber, 1984), the significant increase in the numbers of OIGs suggests a widespread commitment to increased accountability. The attractiveness of the OIG idea can be understood as an instance of what scholars call the “institutionalization” of a common model or archetype. The theory of neo-institutionalism helps explain this phenomenon. This body of theory, also known as “new institutionalism” (CitationMarch & Olsen, 1989), developed out of sociological organizational studies. It was built on an earlier body of scholarship, or “institutionalism,” that examined individual organizations’ development of and response to institutions, which were defined as “cognitive, normative, and regulative structures and activities that provide stability and meaning to social behavior” (CitationScott, 1995, p. 33). Earlier institutionalists examined institutions in the form of a single organization and its immediate environment. These scholars treated institutions as an efficient reaction to the task at hand and to threats from the environment.

Neo-institutionalism shares with the older institutionalism an understanding of institutions as “cognitive, normative, and regulative structures” (CitationScott, 1995, p. 33) but looks beyond a single organization to help to explain why many organizations in similar fields develop common structures and ways of doing things. The core idea is that individual organizations respond not only to local conditions but also to broader field-level ideas and norms. CitationMarch and Olsen (1995) call these norms “logics of appropriateness.” In their description, logics of appropriateness guide individuals and organizations in how to do things, not by maximizing utility, but by acting in the right or “appropriate” way. These logics become institutionalized in rules and organizational structures. Studies informed by this theory also observe that in responding to broader ideas and norms, individual organizations are often acting in ways that are inefficient or unresponsive to local conditions (CitationDiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Edelman et al., 1999; Scott, 1987, 1995). Thus, institutions often “reflect the myths of their institutional environments instead of the demands of their work activities” (CitationMeyer & Rowan, 1977, p. 341).

The spread of OIGs can be explained to a large extent by neo-institutional theory. The initial impetus for creation of the first OIGs seems to have been to address a perceived practical need. CitationLight (1993) explained that Congressional motivation for the passage of the IG Act of 1978 was to address perceived deficiencies in auditing and investigations units coupled with a growing demand for information about federal agencies associated with the expansion of Congressional committees and Congressional staff that was occurring at the same time (CitationLight, 1993). Yet, over time, the OIG has come to be less a response to a clear immediate need than a widely accepted and legitimate way to address the perceived need for greater accountability. As OIGs have spread a recognized archetype has emerged, which is described in detail below.

Despite the emergence of an OIG archetype, the data collected demonstrate that deviations from the archetype have also emerged. One literature that explores variations in policy design is in policy diffusion literature, a learning-focused theory of policy diffusion (CitationMoynihan, 2008; Shipan & Volden, 2012; Volden, 2006), which suggests that jurisdictions learn from each other's experiences, and this learning leads to progressive improvements in policies over time as they spread from place to place. Thus, policies do not remain static as they spread from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, but rather change incrementally as policies are improved over time.

Yet, theories of policy diffusion do not help explain changes in policy that are not progressive in nature and cannot be attributable to learning. In those cases, diffusion scholars have developed the concept of policy reinvention. Reinvention, or as CitationKarch (2007) prefers “customization,” is a term developed by policy diffusion scholars to address policy variations in policies adopted across jurisdictions that did not seem to be explained by neo-institutionalism or learning. These policy changes may appear to be ad hoc, but reinvention suggests that state-specific or locally specific concerns or conditions produce systematic variations (CitationRogers, 2003). Local conditions such as a state's political, economic and social characteristics or interstate competition (CitationBerry & Berry, 1990), liability threats (CitationEpp, 2009), and pressure from interest groups or other organized constituencies (CitationDaley & Garand, 2005; Jun & Weare, 2011) have been found to influence variations in similar policies. If the policy is motivated by political considerations, then the shape of the policy is likely to reflect the interests of those in political power (CitationJun & Weare, 2011). Together these theories of policy diffusion and reinvention help explain why the design of OIGs varies.

1.3 The OIG archetype

Before we can understand deviations from a model, we must understand the model. Since Congress’ creation of the first civilian OIG in the Department of Health, Education and WelfareFootnote3 followed by the passage of the Inspector General Act of 1978, which established 12 OIGs in large federal agencies level, a common model of the structure and powers of an office of inspector general has developed. This common model is codified in two publications of the Association of Inspectors General (AIG): Principles and Standards for Offices of Inspector General (CitationAIG, 2004), also known as the “Green Book,” and Model Legislation for the Establishment of Offices of Inspector General (2002). These documents expand upon the federal prototype and the well-known Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards (also known as GAGAS or the “yellow book,” drafted by the CitationUnited States Government Accountability Office (2011), strengthening the characteristics that exemplify what has become a shared understanding of an OIG that is theoretically best positioned to contribute to the accountability process.

The OIG archetype has four key elements identified by OIG practitioners as essential. These are: (1) the legal form of the OIG's establishment; (2) the complementary duties of audits and investigations; (3) the authority granted the OIG to perform its duties; and (4) the independence granted to the OIG. Each of these elements is discussed separately below.

The first key characteristic of this model is its establishment of OIGs by statute. This legal form is important because it provides an OIG a base of authority and ensures that it cannot be easily restructured, reformed or repealed. The second characteristic is that its duties encompass both auditing and investigations. Auditing with an eye toward improving performance is a proactive, or pre-factum, approach to oversight, and investigating compliance with rules and regulations is a reactive, or post-factum, approach to oversight (CitationDubnick & Frederickson, 2011b; Light, 1993). Both approaches are necessary, as CitationDubnick and Frederickson (2011b) assert: to “break or qualify the link between the two [post-factum and pre-factum dimensions of accountability] … is something that is accountability in name only” (p. 8).

The third characteristic is that the archetypal OIG is granted several types of authority that assist it in performing its role as monitor, collecting necessary information, following the facts where they lead, and then reporting findings and recommendations to others in the accountability process. Authority may include: full and unrestricted access to agency records and the records of those involved with the agency under its jurisdiction; the ability to keep items confidential to the extent required by the law; the authority to subpoena witnesses, administer oaths or affirmations, take testimony, and compel the production of such records as may be relevant; and law enforcement authority (CitationAIG, 2002, §§9, 12; AIG, 2004). Law enforcement authority generally includes authorization to carry a firearm on duty; seek and execute warrants for arrest, search and seizure; and make arrests without a warrant when either witnessing a crime or having reasonable grounds to believe a felony has been committed (see, e.g., IG Act of 1978, as amended, §6).

The fourth and most important characteristic of an archetypal OIG, is independence for an OIG from the agency it oversees. This is crucial because it allows the OIG to provide the most objective, reliable information it can without external influence, which is the essence of the OIG role. The AIG's model legislation describes several ways to protect an OIG's independence in several ways. For example, certain hiring and firing protections are afforded the IG. The model legislation provides for appointment by either the governor with advice and consent of the senate, or appointment by a government official with a position equal to or higher than an agency head over whom the OIG has jurisdiction (CitationAIG, 2002, §4). The IG holds a term of office of five years, during which time the IG may only be removed for cause (CitationAIG, 2002, §6). Further, the model legislation provides that the IG is selected based on professional qualifications and without regard to political affiliations; and the IG may not have previously served as a manager within the agency for at least five years before appointment (CitationAIG, 2002, §4).

Another method used to protect the OIG's independence relates to its budget. The model legislation suggests: “The Office of Inspector General will be funded from the General Fund of the Agency and will receive no less than (X percent) of the General Funds annual appropriation each year” (CitationAIG, 2002, §7). This method of funding aims to ensure that the OIG will receive a guaranteed level of funding each year, which will be directly proportional to the funds allocated for the agency within the OIG's jurisdiction. This funding scheme also removes the OIG budget from the annual political budgetary process and prevents any retaliation against it for work that is not politically pleasing. As to pursuing its mission within the appropriated budget, the IG is granted full authority to manage the OIG without interference. This authority includes structuring the office, hiring and firing employees, and pursuing any audit or investigation without interference.

Lastly, to ensure that an OIG has a forum, or multiple forums, to review and act on the OIG's work, which is necessary for a government actor to be ultimately held to account for their actions, the model legislation states:

The Inspector General will report the findings of the Office's work to the head of the investigated/audited agency, to the appropriate elected and appointed leadership and to the public. The Inspector General shall also report criminal investigative matters to the appropriate law enforcement agencies”. (CitationAIG, 2002, §10)

If any serious or flagrant issues are uncovered, the IG reports this immediately to the agency head, who is required in turn to report the issue to appropriate representatives of the executive and legislative branches, with any comments that the agency head wants to add (CitationAIG, 2002, §10). Finally, the IG issues an annual report to the public that describes its activities over the previous year to the agency head and any interested oversight bodies (CitationAssociation of Inspectors General, 2002, §10).

1.4 Following the model—and deviating from it

Some designers of state and local OIGs closely follow the recommended archetype. This illustrates its influence. Many other designers, however, deviate from the recommended model in significant ways. Ironically, this, too, illustrates the model's influence, as these variations are deliberate. In fact, some designers who choose to deviate do so in order to undercut the OIG's position in the accountability process in specific, well-planned ways. This last type of deviation from the archetype occurs in states that have both high and low levels of corruption and states that have both Democratic and Republican control of state government.

Of the 159 OIGs surveyed, 68% were established formally through statute or ordinance, whereas the remaining 32% were established by a discretionary act. Put another way, while two-thirds of these OIGs are designed in keeping with the statutory element of the archetype, a full one-third of state and local OIGs lack a basis for legal existence and can be eliminated at any time at the discretion of a policy leader. These patterns vary between state-level OIGs and local or multi-jurisdictional OIGs. While three-fourths of state level OIGs have been created in statute, only a little more than half (52%) of local and multi-jurisdictional OIGs were established by statute, a difference that is statistically significant (p ≤ 0.01).

How often are state and local OIGs designed to perform both audits and investigations, as advised by the archetype? As shown in , 67% follow the archetype mode l of performing both audits and investigations, while 30% performed only investigations. The minority of OIGs, 3%, perform only audits. Local and multi-jurisdictional OIGs appear to conform to the archetype and perform both investigations and audits more often than state OIGs, although the difference is not statistically significant (p ≤ 0.01%).

Table 1 Activities pursued by OIGs.

How much does the design of state and local OIGs follow the archetype regarding specific authority to carry out the OIG mission? 72% of the responding OIGs report that they have subpoena power or other authority to compel cooperation. Although the extent of this authority is not specified, i.e., who is required to cooperate with the OIG and whether the OIG has authority to compel both record and testimony, these OIGs generally seem to have formal authority to gather the information they need to perform their oversight duties. Nonetheless, nearly 28% of OIGs lack any authority to compel disclosure of information. On this matter, the difference between state and local/multi-jurisdictional OIGs is statistically significant (p ≤ 0.01). Specifically, 76% of state level OIGs while only 62% local and multi-jurisdictional OIGs have some authority to compel cooperation with their work.

Finally, there is large variation in OIGs’ levels of structural and functional independence. For example, when asked about the extent of their authority to audit or investigate issues of their choosing without interference a majority of survey respondents noted that they have full authority to audit or investigate without interference from the agency or agencies they oversee. Yet 14% (of an n of 51) lack this independence, as is shown in below. Data showed that local and multi-jurisdictional OIGs had this slightly higher aspect to their independence than state OIGs, although this difference was not statistically significant (p ≤ 0.01).

Table 2 Survey question: how broad is your OIG's authority to determine what to investigate or audit?

OIGs also vary in the extent to which they have budgetary independence from the agency that is overseen. Less than half (44%), of OIGs of 149 survey respondents reported they have budgetary independence from the entities they oversee. Budgetary independence is much greater in local and multi-jurisdictional OIGs than state OIGs: 62% of local and multi-jurisdictional respondents report some type of budgetary independence, while only 35% of state-level OIGs report the same, a difference that is statistically significant (p ≤ 0.01).

When it comes to the appointment of the IG, the archetype recommends an appointment process that is not under the discretionary control of the agency being overseen in order to protect independence. The survey showed just over half of the OIGs have hiring protections. Out of 155 respondents, 53% reported some type of hiring protection, such as those mentioned above, while the remaining 47% lacked any such protections. In this aspect, local and multijurisdictional OIGs (74%) have more independence than state level OIGs (43%), a difference that is again statistically significant (p ≤ 0.01).

To understand the adherence to and deviation from the archetype across state and local OIGs on this important issue of independence, a simple additive index was created, based on three characteristics of independence: statutory creation, budgetary independence, and hiring protections for the IG. Admittedly, this is a simplistic view of independence, reduced to a dichotomous view of only three indicators of independence; however, the index does provide an overview of OIG structural variation. This independence index ranges from zero to three. If an OIG reported having all three protections, they rank a 3, but if it has none of these protections, it ranks a 0. shows that nearly the majority of state-level OIGs, almost 50%, have only one of these protections available. Only a little more than 25% have all three indicators of independence. Although there are fewer local OIGs, the data show that they are generally more independent, with nearly 50% having all three indicators of independence. The local OIG independence is not surprising as the government structure is less complex. Many of the local IGs are appointed by a city or county council and get their budget from that source rather than from the mayor or the city manager, which provides them with two points on this index.

Table 3 Comparing OIG independence on three measures.

Although they should not be construed as a measure of OIG effectiveness but rather as an artifact of OIG design, together the survey data reveal considerable deviation from the archetypal OIG. These OIGs vary in specific ways that are deemed important in creating an OIG that is best positioned to pursue its mission of monitoring.

1.5 What is the source of these variations?

The data collected for this project do not support a conclusion that jurisdictions are learning from each other and incrementally improving on the common model, as policy diffusion theory would suggest. Responses to my survey and interviewees suggest that some state policy makers may have learned from the example of other states—but others report that other states had no influence. shows that while about half of all the respondents to the survey reported that the adoption of an OIG in their jurisdiction was influenced by adoption of OIGs in other jurisdictions, about half reported that the establishment of an OIG in other jurisdictions had no influence on the creation of their OIG. A higher percentage of respondents from local and multi-jurisdictional OIGs (64%) reported they were not influenced at all by other jurisdictions compared to state OIGs (46%), although the difference is not statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05).

Table 4 Survey question: how much did the establishment of an OIG in another jurisdiction influence the establishment of your OIG?

Theories of reinvention or customization (CitationKarch, 2007), which suggests that policy-makers adjust common models in response to local conditions, help explain some of the variations in OIG design. One example is the OIG for the Minnesota Department of Human Services. This OIG does not have any of the key characteristics of the OIG archetype. It lacks a statutory basis; the staff perform investigations only, not audits; the office has no official authority to pursue its mission; and it lacks all of the elements of independence recommended by the AIG. In addition, the OIG has no oversight over government employees; rather it monitors contractors and licensees of the Department. Nevertheless, this OIG has been quite effective in improving accountability and performance of the programs the agency administers, despite its structural deviation from the archetype.

Qualitative data show that these deviations were derived from benign intent to shape the OIG to meet local needs, as opposed to a deliberate debilitation. Soon after being appointed to the position of Department Commissioner by the new incoming governor Mark Dayton, Lucinda Jesson announced a plan to increase accountability, fraud prevention, and recovery through the creation of an OIG (CitationMinnesota Department of Human Services, 2011). The Department's press release noted that the Commissioner had been influenced by the federal OIGs and other state OIGs in the area of human services (CitationMinnesota Department of Human Services, 2011). That said, Commissioner Jesson created an OIG that looks very little like any federal OIGs; however, her design choices reflected pragmatic adaptations to existing Minnesota governing structures and policies (CitationFeatherly, 2011). The decision to establish the office by means of her discretion rather than pursing an executive order or statute resulted from an interest to move quickly after her appointment to consolidate the agency's existing fraud investigators who were located in individual program units across the agency (CitationFeatherly, 2011).

The decision to craft the OIG's jurisdiction to include contractors, licensees, and beneficiaries but not Department employees, was an effort to avoid turf battles (confidential personal communication, 2013). At the time the OIG was created, the Department already had an internal compliance unit, tasked with compliance activities of employees throughout the agency, and an internal audit office, which examined and evaluated the Department's fiscal and program management (CitationMinnesota Department of Human Services, n.d.). Thus the OIG was crafted to provide a different focus than already existed.

Another example of localized needs shaping the design of an OIG is found in the OIG for the Illinois Department of Human Services. This OIG, which is one of many in the state of Illinois, has many characteristics of the archetypal OIG. It is created in statute; has subpoena powers for documents and testimony; has access to any facility, agency or employee within its jurisdiction; has an IG appointed by the Governor for a term of four years; and a line item appropriation from the Illinois General Assembly (Illinois Department of Human Services Act, 2013). Still, this Illinois OIG differs from the archetype in one key way: it has a very narrow statutory mission, to investigate allegations of abuse, neglect, or financial exploitation of adult individuals receiving services in state facilities or agencies licensed by the Department (Illinois Department of Human Services Act, 2013). It also investigates any deaths of individuals in these facilities (Illinois Department of Human Services Act, 2013). The statute that creates the OIG specifically states the OIG has no oversight over the routine programmatic, licensing, and certification operations of the Department (Illinois Department of Human Services Act, 2013).

This unique jurisdiction was created to address a very particular concern of the Illinois General Assembly, that older citizens were being exploited and the Department was not effectively addressing the issue with its internal investigations unit (CitationIllinois Department of Human Services Office of the Inspector General, n.d.). A task force report prepared for the Department exposed poor conditions in the state's 21 institutions including “patients … starved, beaten, sexually assaulted, locked in bathrooms, tied to toilets and had alcohol poured into open wounds” (CitationBriggs, 1986). The Department's Director responded to the report by creating an internal OIG (CitationLawrence, 1987). Advocacy groups complained about this action stating: “Instead of addressing the underlying problem of abuse, all they are doing is reorganizing within the department” (CitationGerber, 1987), and “Throwing more millions of dollars at the large institutions or tightening up on procedures is not the answer” (CitationGerber, 1987). These groups lobbied for an independent OIG, whose work would be open for public review (CitationIllinois Department of Human Services Office of the Inspector General, n.d.). As a result, the General Assembly created the OIG in 1987 to investigate suspected abuse or neglect (CitationIllinois Department of Human Services Office of the Inspector General, n.d.). In sum, this OIG's narrow jurisdiction seems to be directly the result of the specific problem to which it was addressed.

In contrast to these examples, other instances of deviation from the archetype OIG are based on a desire to undermine its effectiveness. In these cases, concerns about the potential power of an archetypal OIG result in design characteristics that lessen the potential ability of the OIG to do its job. These design choices aimed at undercutting the independence, authority, and/or jurisdiction of OIGs are made in both states with high and low levels of corruption (as measured by conviction rates) and in states with Republican and Democratic control as well as states with divided party control. Simple evidence of the foregoing point is the absence of any clear correlation at the state level between my index of OIG independence and my measures of corruption and party control.Footnote4 Four examples of policy makers rejecting the archetype in favor of a weaker OIG are the Massachusetts OIG, the Legislative OIG for the city of Chicago, Florida's system of executive OIGs, and the CitationColorado Department of Corrections.

In Massachusetts, a state OIG was adopted by the state legislature, the General Court, in the wake of a major public construction scandal (CitationMassachusetts Special Commission, 1980). Although the General Court designed its OIG in a manner that closely mirrors the archetype, it exempted itself and its documents from the subpoena powers of the OIG, against the direct recommendation of the Special Commission that had investigated the scandal and proposed the creation of an OIG in the first place. Indeed, the Commission had implicated the legislature and its campaign fundraising practices as contributing to the scandal (CitationMassachusetts Special Commission, 1980).

The Commission criticized this decision as well as the General Court's decision to statutorily prevent the OIG from making referrals to federal prosecutors upon finding evidence of the violation of a federal crime (CitationMassachusetts Special Commission, 1980). Under these provisions, if the OIG collected relevant information regarding a violation of federal law, it would be unable to provide it to the precise entity that could hold individuals accountable for their actions. Ultimately, this issue was addressed by the legislature the year following the issuance of the Commission's final report (CitationMassachusetts Office of Inspector General Act, 2013, §10), but the exemption of the General Court from OIG oversight has never been changed (CitationMassachusetts Office of Inspector General Act, 2013, §9).

In Chicago, Mayor Richard M. Daley proposed the creation of the city's OIG to replace the existing Office of Municipal Investigations, a unit that lacked an independent director, subpoena power (CitationMerriner & Rotenberk, 1989) and authority to investigate contractors and city council members (“Chicago is Ready for Reform,” 1989). When the city council considered the proposal, it agreed to all of these elements but balked at giving the OIG jurisdiction over the council (“Council Fears Inspector General's Bite,” 1989; CitationKaplan, 1989). Aldermen stated that they were concerned the office's power could be abused for political purposes (CitationKaplan, 1989).

In Chicago, however, unlike Massachusetts, this objection by the council was met with a public outcry that demanded more independent oversight over the aldermen and their staff. At that point, the council begrudgingly created what is known as the Office of the Legislative Inspector General (CitationBogert, 2010; Chicago, Illinois, Legislative Inspector General city ordinance, 2013). This new office, which clearly has a mission of oversight, is required to follow very restrictive investigatory procedures, which were carefully designed by the city council (CitationBogert, 2010; Chicago, Illinois, Legislative Inspector General city ordinance, 2013; “Thanks, Alderman,” 2010). Thus, although this OIG has several characteristics that would be considered as consistent with the archetypal model, such as the hiring and firing protections recommended in the Association of Inspectors General's model legislation, the IG may not investigate unless upon a sworn complaint (CitationChicago, Illinois, Legislative Inspector General city ordinance, 2013). The problem with this requirement is that many potential complainants may not be willing to come forward if they cannot make an anonymous complaint against powerful aldermen. Additionally, the OIG must get approval from the Board of Ethics (BOE) to pursue a full-blown investigation, who must find reasonable cause in the complaint), and criminal investigations are prohibited (CitationChicago, Illinois, Legislative Inspector General city ordinance, 2013). The Chicago Legislative OIG provides a good example of an OIG that was designed very narrowly by those subject to its oversight with the goal of reducing its ability to pursue its mission.

Third, the state of Florida passed a law that places an OIG in every state agency created the most extensive OIG oversight system outside of the federal government (CitationFlorida Inspector General Act of 1994, as amended 2013). This law was passed on the urging of then-governor Lawton Chiles, a former US senator who was familiar with the federal OIG system and wanted to implement it in Florida (CitationClift, 2014). Yet the Florida OIGs were designed to have considerably less independence than the federal OIGs. Specifically, Florida OIGs lack the budgetary independence and appointment protections that the federal OIGs have, and their reports do not go to anyone besides the agency head. An IG who was present in the legislature's chamber when it passed the Florida IG Act was asked why these changes occurred, the IG stated: “It just didn’t work out. It wasn’t something they could get sponsored, you know? They [the legislature] already had something [the Office of the Auditor General]—someone they thought was looking after them” (confidential personal communication, 2013). As a result the Florida OIGs lack significant independence from the entities they oversee, because the political actors were concerned about the policy implications of these new offices and reduced their power in the design phase.Footnote5

A final example of designing an OIG in a way that limits its independence is found in the Colorado Department of Corrections OIG. The Colorado legislature designed its key OIG much like the Florida OIGs by withdrawing key elements of independence. Although the Colorado OIG was created in statute in 1999 (CitationColorado Revised Statutes 16-2.5-134), other than this statutory foundation it has little independence from the agency head. It functions more like an internal affairs unit in a police department (confidential personal communication). This OIG carries out investigations of criminal acts by employees, inmates, and co-conspirators, performs background checks and random drug testing, manages sexual offender registration, and coordinates the agency's compliance with the federal Prison Rape Elimination Act (Colorado Department of Corrections, n.d.).

When testifying in favor of the bill that created the OIG, the Deputy Director of the Department asserted that the OIG would be an independent voice in various Department functions (CitationColorado Senate Judiciary Committee, April 5, 1999). For example, the OIG's participation in hiring staff by completing background checks was useful to make sure human resource staff were not hiring friends and family. Yet when he was asked directly by a Senator whether the internal unit contemplated in the bill could truly be independent, the Deputy Director answered by saying that there is always a question about whether any agency can police itself, but in this case, if it is seems to be working, then it ought not be questioned (CitationColorado Senate Judiciary Committee, April 5, 1999). In fact, this OIG never has been independent from the executive director (confidential personal communication, 2013). The IG answers to the executive director and performs the duties assigned to it in statute and by the executive director. The OIG is, however, independent from other units in the Department, which allows it to provide oversight of other units’ compliance with professional standards and policy violations without interference from those units (confidential personal communication, 2013).

In sum, states and localities commonly design new OIGs in ways that withdraw key forms of independence and authority from these agencies. Sometimes these withdrawals seem benign in light of the expectations of the archetypal model, but sometimes these withdrawals of independence or authority, or both, seem to be deliberate, strategic efforts to limit or control the power of an OIG. Neither the benign nor the deliberate variations seem related to partisan control of the state (or partisan competition) or to the level of corruption.

2 Conclusion

As more and more OIGs have been adopted across the country, one might assume that this provides evidence of a strong commitment to increased government accountability in cities and states; however, when comparing these new OIGs with a detailed OIG archetype created by OIG practitioners, it becomes clear that many OIGs lack necessary attributes that help an OIG to best perform its role, theoretically speaking, in the accountability process. Although there is evidence that institutional variations arise due to local needs and conditions, some government officials would like to maintain a check on it rather than grant it fundamental independence and broad investigative powers. These concerns arise from the fact that OIGs have the potential to produce information that governmental actors may prefer not to be made public. This fear is justified because, without a receptive audience to the information OIGs’ work within the agency they oversee, their only real power is to produce such egregious or alarming information about an actor's conduct that the forum simply cannot ignore it. Put another way, without cooperation, the OIG's primary tool to ensure government accountability from a recalcitrant agency is to shame or embarrass the agency. Realistically, shame and embarrassment could lead directly to reductions in funding for the programs exhibiting problems, but this would depend on another actor, specifically a body with budget appropriation powers, taking those steps. Nevertheless, being able to publicize information that is potentially embarrassing is a powerful tool, and in many instances shocking information demands action to correct the problem. For example, if an OIG can produce comprehensive and reliable information that someone has committed a significant fraud against the jurisdiction, a prosecutor will be more likely to charge the individual with a crime, or a supervisor will be more likely to take an administrative action, or a legislator may reduce funding. This potential to embarrass and shame is precisely why OIGs are so threatening to those they oversee.

As a consequence, while the idea of an OIG has great popularity and appeal, and this motivates adopting such a body in some form, many policymakers tweak or radically revise the design, and the end result is often an office that does not match up with the archetype. Some reasons for these changes are undoubtedly benign. Sometimes a jurisdiction's particular conditions and needs shape the OIG in unique ways. In other cases, policy makers withdraw from the OIG key elements of the archetypal OIG's authority or independence. As a result, one cannot conclude that the increasing numbers of OIGs mean that government accountability is also increasing. Policymakers pursuing accountability must be aware that OIGs may be vulnerable to debilitation when it is designed, and practitioners must be aware that there may be many design characteristics that will need to managed or altered if the OIG's role can be fully achieved.

Notes

1 It should be noted that although each office included in the data set uses the term “inspector general” in some way, not all offices are officially titled Office of Inspector General. For example, in the data set, there is an Office of Inspector General Services and an Office of Legislative Inspector General. For the purposes of this paper, each of these offices is referred to as an OIG and the head of the office as an IG.

2 The survey was pretested by two former IGs, but not cognitively pretested (CitationWillis, 2004), and as such, survey questions may be open to looser interpretation than is ideal.

3 Congress divided HEW into the Departments of Education and of Health and Human Services in 1979.

4 X2(1, N = 30) = 0.26; p = 0.35. (For states with more than one OIG, the index scores for all OIGs was summed and divided by the number of OIGs to produce a state average OIG independence score.)

5 A post-script to the story of the design of the Florida OIG Act illustrates the significance of these earlier efforts to debilitate Florida OIGs: there have been ongoing efforts to overcome these limitations. This year, the legislature passed legislation that increased the independence of the OIGs in terms of the hiring and firing of IGs and proving the IGs authority to hire and remove their own staff without agency interference (CitationFlorida House of Representatives, 2014).

References

- F. Anechiarico , J.B. Jacobs . The pursuit of absolute integrity: How corruption control makes government ineffective. 1996; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL

- C.R. Apaza . Integrity and accountability in government: Homeland security and the inspector general. 2011; Ashgate: Surrey, UK

- Association of Inspectors General . Model legislation for the establishment of offices of inspector general. 2002. Retrieved from http://inspectorsgeneral.org/files/2011/01/IG-Model-Legislation.pdf .

- Association of Inspectors General . Principles and standards for offices of inspector general. Philadelphia, PA. 2004. Retrieved from http://inspectorsgeneral.org/files/2014/01/greenbook_may2004revision.pdf .

- F.S. Berry , W.D. Berry . State lottery adoptions as policy innovations: An event history analysis. The American Political Science Review. 84(2): 1990; 395–415.

- N. Bogert . Chicago's new inspector general a “watch kitten”?. 2010; Examiner.com. Retrieved from http://www.examiner.com/article/chicago-s-new-inspector-general-a-watch-kitten .

- M. Bovens . Analysing and assessing accountability: A conceptual framework. European Law Journal. 13(4): 2007; 447–468.

- M. Briggs . Mental patient abuse probe set—Report alleges sex attacks, beatings. 1986; Chicago Sun-Times.

- Chicago, Illinois . Legislative inspector general city ordinance. 2013. [chapter 2-55].

- B. Clift . Capture the synergy. 2014; Florida Department of Transportation Office of Inspector General Examiner. Retrieved from http://fdotoig.wordpress.com/2014/03/03/capture-the-synergy/ .

- Colorado Department of Corrections. (n.d.). Office of the inspector general. Retrieved from http://www.doc.state.co.us/office-inspector-general..

- Colorado Revised Statutes (CSR) 16-2.5-134, 2013..

- Colorado Senate Judiciary Committee . Hearing on HB 1317, concerning the clarification of the responsibilities of investigative positions within the Department of Corrections. 1999

- D.M. Daley , J.C. Garand . Horizontal diffusion, vertical diffusion, and internal pressure in state environmental policymaking, 1989–1998. American Politics Research. 33(5): 2005; 615–644.

- P.J. DiMaggio , W.W. Powell . The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review. 48(2): 1983; 147–160.

- M.J. Dubnick , H.G. Frederickson . Introduction: The promises of accountability research. M.J. Dubnick , H.G. Frederickson . Accountable governance: Problems and promises. 2011; M. E. Sharp: Armonk, NY xiii–xxxii.

- M.J. Dubnick , H.G. Frederickson . Public accountability: Performance measurement, the extended state and the search for trust. 2011; Kettering Foundation: Dayton, OH

- M.J. Dubnick , J. O’Brien . Rethinking the obsession: Accountability and the financial crisis. M.J. Dubnick , H.G. Frederickson . Accountable governance: Problems and promises. 2011; M. E. Sharp: Armonk, NY 282–301.

- L.B. Edelman , C. Uggen , H.S. Erlanger . The endogeneity of legal regulation: Grievance procedures as rational myth. American Journal of Sociology. 105(2): 1999; 406–454.

- C.R. Epp . Making rights real: Activists, bureaucrats and the creation of the legalistic state. 2009; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL

- K. Featherly . New DHS Inspector General Kerber aims to root out fraud, client abuse in Minnesota. The Legal Ledger. 2011. Retrieved from http://politicsinminnesota.com/2011/11/new-dhs-inspector-general-kerber-aims-to-root-out-fraud-client-abuse/ .

- Florida Inspector General Act of 1994 . Florida Statutes § 20.055. 2013

- Florida House of Representatives Final Bill Analysis, HB 1385. (2014). Retrieved from http://www.myfloridahouse.gov/Sections/Documents/loaddoc.aspx?FileName=h1385z.GVOPS.DOCX&DocumentType=Analysis&BillNumber=1385&Session=2014..

- T. Gerber . Mental home abuse probe set—State study cites faulty reporting. 1987; Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved from http://infoweb.newsbank.com.www2.lib.ku.edu:2048/resources/doc/nb/news/0EB36D8245E36F90?p=NewsBank .

- Illinois Department of Human Services Office of Inspector General. (n.d.). History of OIG. Retrieved from http://www.dhs.state.il.us/page.aspx?item=29412..

- K.N. Jun , C. Weare . Institutional motivations in the adoption of innovations: The case of e-government. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 21(3): 2011; 495–519.

- J. Kaplan . Daley inspector denied a key power. Chicago Tribune. 1989, September 13

- A. Karch . Democratic laboratories: Policy diffusion among the American states. 2007; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI

- J.W. Kingdon , J.A. Thurber . Agendas, alternatives and public policies. Vol. 45 1984; Little, Brown: Boston, MA

- M. Lawrence . State acts on patient abuse—Mental health crackdown today. 1987; Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved from http://infoweb.newsbank.com.www2.lib.ku.edu:2048/resources/doc/nb/news/0EB36D820CDF2796?p=NewsBank .

- P.C. Light . Monitoring government: Inspectors general and the search for accountability. 1993; The Brookings Institution: Washington, DC

- J.G. March , J.P. Olsen . Rediscovering institutions: The organizational basis of politics. 1989; New Press: New York, NY

- J.G. March , J.P. Olsen . Democratic governance. 1995; The Free Press: New York, NY

- Massachusetts Office of the Inspector General Act of 1980 . Ann. Laws Mass., GL. 2013. [chapter 12A].

- Massachusetts Special Commission concerning State and County buildings . Final report to the Massachusetts General Court (“Massachusetts Special Commission Report”). 1980

- J. Merriner , L. Rotenberk . Daley asks anti-corruption office. Chicago Sun-Times. 1989, January 31. Retrieved from http://infoweb.newsbank.com.www2.lib.ku.edu:2048/resources/doc/nb/news/0EB36E34C3F785D3?p=NewsBank .

- J.W. Meyer , B. Rowan . Institutional organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology. 83(2): 1977; 340–363.

- Minnesota Department of Human Services . DHS announces creation of the Office of Inspector General. 2011. Retrieved from http://www.dhs.state.mn.us/main/idcplg?IdcService=GET_DYNAMIC_CONVERSION&dID=119547 .

- Minnesota Department of Human Services. (n.d.). Organization/management. Retrieved from http://www.dhs.state.mn.us/main/idcplg?IdcService=GET_DYNAMIC_CONVERSION&RevisionSelectionMethod=LatestReleased&dDocName=id_000261..

- D.P. Moynihan . Learning under uncertainty: Networks in crisis management. Public Administration Review. 68(2): 2008; 350–365.

- K.E. Newcomer . Opportunities and incentives for improving program quality: Auditing and evaluating. Public Administration Review. 54(2): 1994; 147–154.

- K.E. Newcomer . The changing nature of accountability: The role of the inspector general in federal agencies. Public Administration Review. 58(2): 1998; 129–136.

- A. Ranney . Parties in state politics. H. Jacob , K. Vines . Policies in the American states. 3rd ed., 1976; Little, Brown & Co.: Boston

- E.M. Rogers . Diffusion of innovations. 5th ed., 2003; Free Press: Glencoe, IL

- W.R. Scott . The adolescence of theory. Administrative Science Quarterly. 32(4): 1987; 493–511.

- W.R. Scott . Institutions and organizations: Toward a theoretical synthesis. 1995; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA

- L. Segal . Independence from political influence—A shaky shield: A study of ten inspectors general. Public Integrity. 12(4): 2010; 297–314.

- C.R. Shipan , C. Volden . Policy diffusion: Seven lessons for scholars and practitioners. Public Administration Review. 72(6): 2012; 788–796.

- Thanks Aldermen . Chicago Tribune (Editorial). 2010. Retrieved from http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2010-04-13/opinion/ct-edit-inspector-20100413_1_aldermen-michael-shakman-inspector .

- United States Census . 2010 Annual survey of public employment and payroll. 2010. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov//govs/apes/historical_data_2010.html .

- United States Census . 2010 Census summary file 1, table P1 total population. 2010. Retrieved from Retrieved from factfinder2.census.gov.

- United States Government Accountability Office . Generally accepted government auditing standards, 2011 Revision. GAO-12-331G. 2011

- C. Volden . States as policy laboratories: Emulating success in the Children's Health Insurance Program. American Journal of Political Science. 50(2): 2006; 294–312.

- Gordon B. Willis . Cognitive interviewing: A tool for improving questionnaire design. 2004; Sage Publications.