Abstract

In recent years, scholars and policymakers have become interested in the idea of a smart mix of voluntary and regulatory measures in private governance. If public and private actors are to share the work load of governing the commons, this presupposes that both sides can agree on this compromise formula — but can they? So far, we have limited knowledge of firms and business associations’ regulatory preferences in this realm. As a ground-clearing exercise my article aims to help fill this gap and expose some of the underappreciated fault and conflict lines within private governance. Its thrust is that existing literature is excessively optimistic about business's willingness to support regulation. The article surveys the EU's non-financial disclosure Directive and half a dozen other attempts to regulate CSR or non-financial disclosure across the world, and finds that public authorities’ more ambitious attempts at regulation met with vigorous business opposition. Even after the financial crisis, most business associations and firms reject a smart mix in favor of voluntarism and soft law without hard sanctions.

1 Introduction

Does private regulation “supplement and support government regulation”? (CitationO’Rourke, 2003: 3). In recent years, a growing number of scholars and practitioners have come to answer in the affirmative. Popularized by John Ruggie, Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations, the idea of a smart mix of voluntary and regulatory measures has emerged as a compromise formula between advocates of voluntary, private, market-based regulation one hand and hard law on the other. According to this reasoning, private market-based regulation can be a viable business strategy and a source of comparative advantage and social improvement in niche markets, but if it is to have a more consistent and widespread impact, some regulation is needed. A smart mix implies that private governance and hard law regulation are complementary or at the very least compatible. The suggestion seems to be that a smart mix combines the best of both worlds: the flexibility, dynamism, innovativeness, reflexivity and adaptability of voluntary market-based solutions and the authoritativeness, scope, and binding force of legal regulation.

Bolstered by these attractive characteristics and the perception that neo-liberal voluntarism contributed to the global financial crisis, the smart mix has inspired many policy initiatives and organizations. Perhaps it has become the new received wisdom in the field. To cite one example, the Group of Friends of Paragraph 47 explicitly advocates a “Smart Mix.” The group was formed at the 2012 UN Conference on Sustainable Development in Rio de Janeiro to promote corporate sustainability reporting through various means including regulation and a smart mix of soft and hard law. It currently comprises ten governments who receive support from the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and a number of other organizations.

This article is concerned with the political viability of smart mix arrangements. I argue that scholars have made a serious error by assuming that because a smart mix is needed, business organizations will agree to it in practice. As we will see in the pages below, this is a non sequitur — it does not follow empirically or theoretically. The bottom line is that business organizations want to keep private governance private and that in most cases, public authorities have to overcome business opposition to establish these arrangements.

This article is organized as follows. Section 2 provides some basic theoretical considerations and an overview of the historical background to the current conjuncture. Section 3 discusses the EU's new non-financial reporting Directive and the ways in which it was changed as a result of business opposition. Section 4 provides an overview of the way in which business organizations have responded to various CSR and non-financial reporting mandates in Mauritius, India, Indonesia, the United States, South Africa and the United Kingdom. These cases will help us to assess the relationship between business responses and regulatory stringency. The rationale for this case selection is discussed in greater detail below. Section 5 concludes the article by underlining the conflictual interactions and divergent interests between public authorities and business organizations in the private governance arena.

2 Historical background and theoretical considerations

Activists and scholars have long advocated binding legal regulations for corporate conduct. In 1973, the United Nations Center on Transnational Corporations began its work on a legally binding code of conduct for transnational corporations. While these attempts failed and the UNCTC was eventually disbanded, many have continued to push for regulatory elements in private governance. David Vogel stresses that CSR must “include efforts to raise compliance standards” (CitationVogel, 2005: 171). Geoffrey Chandler calls the idea that “regulation is unnecessary and voluntarism [is] enough” a “myth”:

The whole of corporate history shows unequivocally that protection of the interests of stakeholders other than shareholders has not come from voluntary corporate initiative, but from extended pressure followed by legislation. This has been true of labour conditions, of protection of the environment and, today, observance of human rights. The market economy survives today because it is not a ‘free’ market,’ but one bounded by moral parameters enforced by law (CitationChandler, 2006: 66).

In a similar vein, Craig Murphy finds “little evidence to suggest that private governance can ever substitute for public regulation” (Citation2009: 134). The global financial crisis provided a powerful boost to these re-regulatory efforts as it shattered faith in markets’ self-regulation and purely voluntary private regulation schemes and gave way to a growing consensus on mixed public-private regimes with an integral hard law component (more generally see, e.g., CitationTosun, Wetzel, & Zapryanova, 2014).

It is not clear who coined the term ‘smart mix,’ and it does not really matter for the purposes of this analysis. In the context of private governance, this term grew increasingly popular in the 2000s, and high profile figures including John Gerard Ruggie and institutions including the European Commission have referred to it in recent years. Unlike highly prescriptive ‘command and control’ regulation which specifies in detail what companies/managers must do and how they must do it, a smart mix leaves ample scope for entrepreneurial and managerial discretion and voluntary action. In this respect, a smart mix has much in common with “responsive law,” which is characterized by “openness” and “perceives social pressures as sources of knowledge and opportunities for self-correction” (CitationNonet & Selznick, 1978: 77). One current example of the smart mix is the EU's new non-financial reporting Directive, discussed in detail below, which states that companies must report on their social and sustainability activities and performance but does not specify in detail what sustainability programs must be in place or how reports must be written.

John Ruggie, one of the most prominent proponents of this approach, states that “achieving significant progress” in global governance “would require moving beyond the mandatory vs. voluntary dichotomy to devise a smart mix of reinforcing policy measures” (CitationRuggie, 2013: xxiii). Ruggie states that his influential UN Guiding principles on business and human rights “are intended to generate a new regulatory dynamic under which public and private governance systems — corporate as well as civil — each come to add distinct value, compensate for one another's weaknesses, and play mutually reinforcing roles — out of which a more comprehensive and effective global regime can evolve” (CitationRuggie, 2013). Similarly, in his authoritative study on promoting labor standards, Richard Locke argues:

Government regulation is required because only the state has the authority to enforce labor regulation and promote/protect citizenship rights … public and private regulatory efforts need to work with and build off one another …. Private compliance efforts, capacity-building initiatives, and even innovative state enforcement strategies … are necessary and important components to this strategy but none alone is sufficient to tackle this complex set of issues (CitationLocke, 2013: 177)

Like the above scholars, Frederick W. Mayer believes that while private governance is here to stay,

Private governance, alone, appears insufficient to meet the demand of society …. Private governance, whether based on a pure business case or induced by pressures from civil society, was always at best a partial solution … at the end of the day, societal demands for governance are hard to sustain unless institutionalized in government policy (CitationMayer, 2014: 345; 357)

While the idea of a smart mix to co-govern common goods has become mainstream (see CitationTosun, Koos and Shore, 2016), realizing it by leveraging private governance for public purposes remains difficult in practice because of the contested and conflictual relationship between the public and private sector. If the latter's power is not “countervailed by other forces in society,” the result could be “public-private governance that largely reflects corporate interests” (CitationMayer, 2014: 357; 358). To understand the dynamics of these interactions, and the public sector's prospects for success, we need to focus on the following question: how does business respond to public authorities’ regulatory efforts?

It is important to clarify what this article does and does not do. It does not set out to specify the conditions under which smart mixes succeed or fail. Instead, it is intended as a ground-clearing exercise that focuses on one of the foundational assumptions of the smart mix and the private governance literature — the willingness of business organizations to agree on this compromise formula. Business associations are capital's political face: their positions are particularly influential in policymaking, and many but the largest companies outsource there lobbying activities to these organizations. Few people would seriously doubt the political power of business in today's globalized, neo-liberal world. But so far we have limited knowledge of firms and business's regulatory preferences. There is much at stake in this as the positions taken by business can facilitate or impede efforts to establish a smart mix. If business is supportive, the prospects for a robust smart mix will be good. But business opposition may pose a serious obstacle to these efforts. Even if business resistance does not completely derail attempts to establish a smart mix, it could significantly weaken the resulting frameworks. If business resistance persists, these arrangements could prove unsustainable. Only if there is real business buy-in will smart mixes of voluntary and complementary regulation be viable in the long run. If this reasoning is correct, the positions of business are worthy of careful empirical analysis in and of themselves. But rather than undertake this analysis, many scholars have simply assumed business's willingness to participate in these frameworks, or extrapolated from a small number of cases in which a small number of firms with high economic, social, and governance (ESG) performance have spoken out in favor of regulation.

As I will show in the pages below, this is problematic. The thrust of my article is that existing literature is excessively optimistic about business's willingness to support regulation. Even after the financial crisis and in countries with dynamic economies and high levels of social deprivation, most business associations and firms reject a smart mix in favor of voluntarism and soft law. While a comprehensive theorization of the role of employers in private governance and standard setting is beyond the scope of this article, for the purposes of orientation it is useful to distinguish between two different roles or ideal types: one cooperative, the other adversarial.

On one hand, we have the popular image of the private sector cooperating with public authorities raise regulatory standards and share the work load of governing the commons. Though by no means universal, this is the conventional wisdom, the predominant view among scholars and practitioners in the private governance arena. On the other hand, the relationship between public authorities and the private sector may be conflictual rather than cooperative. Firms and business associations may block public authorities’ attempts to raise regulatory standards, and private governance may be a substitute rather than a complement for regulation, as some scholars (for example CitationOrly, 2004) have argued. In this alternative view, capitalists are unruly, restless, and subversive (CitationStreeck, 2009). Even if they are unable to prevent public authorities from implementing regulations, they will strive to weaken them as much as possible. When it comes to the politics of regulation, the empirical evidence in this article provides strong support for the second (unruly predator) interpretation and very little support for the first (cooperative member of civil society) interpretation.

This point can be put in a slightly different way. To date, much of the literature on the governance of common goods has failed to “take capitalism [and capitalists] seriously” (CitationStreeck, 2011). The literature frequently views private governance as inhabiting the world of what Wolfgang Streeck calls “Durkheimian” institutions. These institutions circumscribe markets by “limit[ing] or regulat[ing] the egoistic pursuit of material interests” and by creating obligations toward society (CitationStreeck, 2011: 153). However, the evidence in this article suggests that business support for these institutions is limited. Most business representatives reject Durkheimian in favor of voluntaristic “Williamsonian” institutions (CitationStreeck, 2011: 153–154).

This article aims to expose some of the underappreciated fault and conflict lines within private governance. It is concerned with private governance arrangements with a mandatory or hard law component. I call these Regulated Private Governance (RPG) arrangements. By contrast, I call private governance arrangements without such a legal component Voluntary Private Governance (VPG). These are ideal types, which are not always easy to distinguish in reality. For example, the UK Corporate Governance Code is legally binding, yet its soft law quality and extensive reliance on the comply or explain principle gives it a voluntaristic quality in practice. In any case, the important point is that business is much more amenable to VPG than to RPG regimes.

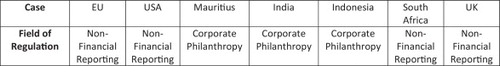

The core of this article is an analysis of the EU's non-financial disclosure Directive, but I also survey a number of other cases of private governance with a hard law regulatory component. summarizes these cases as well as the field of regulation.

These cases are heterogeneous and the term ‘smart mix’ is not used in all of them. But they share the underlying idea of using legal mandates to support, boost and amplify the scope and effectiveness of private governance. While four cases (the EU, South Africa, the USA and the UK) are concerned with public authorities’ attempts to mandate non-financial reporting, three others (Mauritius, India and Indonesia) are closer to what we might call corporate philanthropy — mandating donations to local community groups. Section 3 on the EU uses process tracing while Section 4 adds a comparative account of six country cases. In each case, I am concerned with the responses of the major business and industry associations to public authorities’ CSR and non-financial reporting mandates. While I have sought to analyze each of these cases in Section 4 with due diligence, there may well be trade-offs between breadth and depth. In my view, these trade-offs are acceptable since these countries are what one might call ‘shadow cases.’ It is striking that in spite of myriad differences, these cases share much in common: the major business and industry organizations opposed more stringent regulations in the majority of cases and were only pliant in two cases (South Africa and the UK) where regulations were less stringent. This approach approximates John Stuart Mill's most different systems design: these cases have little in common except business opposition to regulation.

3 The EU's non-financial reporting Directive

The EU's new accounting Directive 2014/95/EU will require approximately six thousand companies across the EU to report on their social, environmental and human rights impacts and the risks their activities pose for third parties. While companies will retain a considerable amount of freedom and flexibility concerning how they report, they will no longer have discretion over whether to report or not when this Directive enters into force in 2017. According to many observers, the EU's move to make non-financial reporting mandatory for large companies and groups represents a meaningful step toward greater corporate accountability. The shift from a voluntarist laissez-faire approach to CSR to mandatory non-financial reporting began in the late-2000s and was caused by a confluence of factors including the failure of voluntary approach to non-financial disclosure in the 2003 EU Accounts Modernization Directive to achieve significant progress in corporate accountability, the global financial crisis, global policy developments in the area of CSR, and advocacy by institutional investors. In this article, I am concerned with business's reactions to this proposal rather than with a detailed analysis of the role of different actors in the negotiations.

From the very start, this Directive has been motivated by the idea of a smart mix. In its communication “A renewed EU strategy 2011–14 for Corporate Social Responsibility,” the European Commission made clear that

The development of CSR should be led by enterprises themselves. Public authorities should play a supporting role through a smart mix of voluntary policy measures and, where necessary, complementary regulation, for example to promote transparency, create market incentives for responsible business conduct, and ensure corporate accountability (CitationEuropean Commission, 2011: 7)

This communication unleashed a flurry of interest group activity. BusinessEurope — the EU's leading business lobby organization representing national business and employers’ organizations in more than thirty European countries — made the following remarks:

EU policy should not interfere with companies seeking flexibility to develop an approach to CSR according to the specific needs of their stakeholders and their individual circumstances …. The strategy highlights the role of public authorities as creating market incentives for responsible business conduct not only through voluntary policy measures but also through complementary regulation. We believe that this more interventionist approach is not the right way forward, as CSR has an added value when it stems from a real belief at company level of its benefits for business performance. This added value cannot be created by public authorities (CitationBusinessEurope, 2012: 1; 4)

The opposition of the German delegation was particularly forceful. German business and political representatives fought tooth and nail to prevent the Commission from moving forward with disclosure requirements. This stance appears somewhat puzzling given that that leading German firms engage very substantively with CSR (see CitationFavotto, Kollman, and Bernhagen, 2016). This pressure was felt by insiders in the Commission, and as a result, according to a staff member close to the file, there was a “20–30 per cent chance that the proposal might get delayed, or canceled altogether” (CitationKinderman, 2013: 714). But in the end, the Directive did see the light of day. In it, the Commission set out

a requirement for certain large companies to disclose relevant non-financial and diversity information, ensuring a level playing field across the EU. Nevertheless, it takes a flexible and non-intrusive approach. Companies may use existing national or international reporting frameworks and will retain their margin of manoeuvre to define the content of their policies, and flexibility to disclose information in a useful and relevant way. When companies consider that some policy areas are not relevant for them, they will be allowed to explain why this is the case, rather than being forced to produce a policy (CitationEuropean Commission, 2013: 2)

If the domain of EU CSR has long been governed by “reflexive law,” which Buhmann defines as “a form of public (procedural) law for regulation which achieves substantive results through co- and self-regulation by societal actors” (CitationBuhmann, 2011b: 60), this also appears to be the case for the EU's non-financial reporting Directive. Although the Directive marks an important transition from neo-liberal voluntarism toward a more regulatory approach (CitationKinderman, 2013), the legislation contains many flexible elements, and introducing hard law into the equation might arguably help address the power disparities between different stakeholders which had previously plagued EU CSR (CitationBuhmann, 2011a).

How did business react? In the lead-up to the announcement of the actual proposal, business representatives may have feared that the Commission would introduce a highly prescriptive text which would impose significant administrative burdens and reduce businesses’ flexibility. Given that the proposal does not mandate particular policies or the achievement of specific sustainability or accountability benchmarks and contains extensive “comply or explain” provisions, one might expect business organizations to take a moderate or perhaps even a supportive stance. Not so — even this soft and flexible legal mandate has been significantly weakened as a result of vigorous business opposition. In its detailed response to the Commission's proposal, BusinessEurope stressed that “CSR as a whole must be voluntary and business-driven” and that “The proposal creates red-tape for business” (CitationBusinessEurope, 2013: 1) while making a number of specific recommendations to weaken the proposal and restrict its scope as much as possible. The response of EuroChambres — which represents local and regional Chambers of Commerce across the EU — was very similar:

Under the current legal framework, businesses can freely decide if and to what extent to disclose non-financial information to the public or to their shareholders and stakeholders, following a balanced evaluation of consequent positive outcomes in terms of market share, image and accountability. EUROCHAMBRES firmly believes that this approach should be maintained. Companies are best placed to decide whether to voluntarily commit beyond the pure legal requirements when it comes to the disclosure of non-financial information. Obliging businesses to disclose non-financial information would impinge on business efficiency and competitiveness and jeopardise the capacity to innovate (CitationEurochambres, 2013: 2)

Given the lowest-common-denominator positions often taken by large organizations with a diverse membership, BusinessEurope and Eurochambres’ opposition may not be surprising. No less relevant is the question of support. Perhaps leading companies and sustainable business organizations have supported the Directive?

A prominent EU-level responsible business organization — CSR Europe — and socially responsible investors — Eurosif and Aviva Investors — and the GRI — a non-financial reporting framework — have expressed support, though CSR Europe did not do so publicly. As the world's leading framework for non-financial reporting, the Global Reporting Initiative has an obvious ideal and organizational interest in having thousands of new companies preparing non-financial reports. CSR Europe — the leading EU-level CSR organization with an expertise in responsible business practice — also seeks to advance this agenda, and they too could benefit by delivering cutting-edge expertise on practice and implementation. Yet it seems that some of CSR Europe's member companies or national partner organizations were uncomfortable with this agenda, which prevented CSR Europe from making a public pronouncement. Socially responsible investor organizations have provided support: both the European Sustainable Investment Forum (Eurosif), the EU's leading sustainable investment association, and London-based Aviva Investors, one of the world's largest insurance companies, have played an important supportive role in the negotiations. But only two large companies have publicly expressed public support: Unilever and Ikea.Footnote1 To put this in perspective, according to the EU's measurement criteria, there are approximately 42,000 large companies in the EU. While a handful of progressive small business leaders and CSR officials supported the idea, in the larger scheme of things, this group is miniscule. Interestingly, even many leading sustainable businesses — companies with high ESG performance which one would think have a vested interest in upward regulatory harmonization — were opposed, indifferent, or unwilling to break ranks with industry lobby groups.

But does any of this really matter? Sadly, for proponents of a smart mix, it does. On February 26, 2014, representatives of the Hellenic Council presidency, the European Parliament and the European Commission reached a compromise in the Trialogue negotiations. On April 15, 2014, an overwhelming majority of members of the European Parliament supported the proposal and on September 29, 2014, the Council of the EU officially adopted the Directive. While the Directive was not killed, it was weakened significantly. In a press release from April 15, 2014, Jerôme Chaplier, Coordinator of the civil society organization European Coalition for Corporate Justice (ECCJ), remarked that “This is an important step forward. The reform recognizes that the environmental and human rights impacts of companies are of key concern for society as a whole. It will empower people to access information on how they might be affected by business operations, and enable shareholders to hold the management accountable for negative impact …. However, we regret that the original proposal has been weakened so much” (CitationECCJ, 2014). The Directive “Falls Short of Responsible Investors’ Expectations” was the heading of an April 15 Eurosif press release. Eurosif's Director François Passant stated that “Eurosif is disappointed that the text of the legislation was significantly weakened during the course of the trialogue negotiations” (CitationEurosif, 2014: 1).

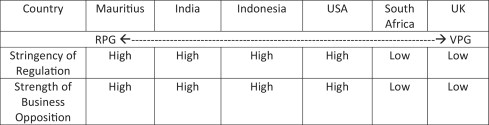

The scope of the requirements was reduced significantly. Initially, the Directive was to apply to all companies with over 500 employees that had a certain annual turnover or balance sheet total, a total of approximately 18,000 firms across the EU. This would have represented a significant increase in comparison with the approximately 2500 companies reporting today. The final version will apply only to public interest entities of over 500 employees such as publicly listed companies and financial institutions. Non-listed companies will be largely excluded by the requirements. This means that the Directive will apply to only approximately 6000 or 1/3 as many companies as the Commission's original proposal. Since firms’ participation in NFR continues to increase at a rate of approximately 8–9% per year even in the absence of legal mandates, I estimate that the Directive will only increase firms’ non-financial reporting by approximately 75% by 2017 as compared to a more than five-fold increase with the original proposal. While the Commission's original proposal would have included approximately 42% or a sizeable chunk of the 42,000 large companies in the EU, the final Directive will only apply to approximately 14% of these companies. shows the figures for business as usual, the Commission's initial proposal, and the final (actual) EU Directive as a proportion of the EU's approximately 42,000 large companies.

Fig. 2 The scope of the EU non-financial reporting Directive compared with business as usual as a proportion of large companies in the EU.

Source: Author.

The proposal has also been modified in other respects: several articles have been softened by more flexible wording. And whereas the original proposal stipulated that the non-financial information should be included in the company's annual report, the revised proposal states that this information can be provided separately from the annual management report and up to six months after its publication. We are a long way from integrated reporting! The revised proposal also includes a safe harbor clause, which allows member states to omit the reporting of information in particular cases when doing so would be “seriously prejudicial to the commercial position of the undertaking.” It is inconceivable that the Directive would have been weakened so much without vigorous opposition. But given that this Directive was approved perhaps this business opposition is a thing of the past?

Events at the EU's 2015 Multi-Stakeholder Forum on Corporate Social Responsibility suggest that this is not the case. On February 3, 2015, Pierre Delsaux, Deputy Director, DG Grow (formerly DG Enterprise), European Commission, kicked off the event by stressing that the Commission did not endorse a “heavy-handed, mandatory, or prescriptive approach” to CSR. Richard Howitt, the European Parliament's leading CSR advocate, stated that “We’ve ended a destructive argument about definition and about the old false dichotomy between voluntary or mandatory approaches. Instead we’ve built a consensus that a ‘smart mix’ between the two provides the only constructive basis for action.” In the words of DG Grow's Johanna Drake, “we advocate a non-prescriptive approach consisting of a smart mix and if necessary complementary regulation.” Given the effort these Commission officials made to appease business, it is quite striking that the business representatives in attendance did not buy it. Arnaldo Abruzzini, the EuroChambres representative, stated that “having a voluntary approach is the opinion of our members.” BusinessEurope's Deputy Director General Thérèse de Liedekerke went even further. She said that “doing beyond the voluntary approach would stifle innovation … and kill the very notion of CSR in the long run.”

The picture that emerges from this section is one of business opposition to regulation: the coalition of organizations that supported a voluntary, rather than a regulated approach to CSR, and whose “ideas about CSR resonated strongly” (CitationFairbrass, 2011: 962) in the period leading up to the financial crisis, does not want to budge one bit. There were some companies, responsible business organizations and socially responsible investors that supported the Directive. Most employers’ associations did not, with two notable exceptions. MEDEF, France's largest employers’ association, actually supported the Directive. The explanation seems to be that France already has far-reaching domestic non-financial reporting regulations. While it appears that French business associations initially opposed these domestic non-financial reporting regulations, once they were in place they pressed for an international harmonization of rules. The Danish Employers’ and Industry Associations DA and DI were also supportive, although they favored a more flexible light-touch approach in line with Denmark's domestic non-financial reporting requirements. The section below surveys the cases of Mauritius, India, Indonesia, the United States, the United Kingdom, and South Africa. These cases will help us to assess whether there is significant cross-national variation in the positions and responses of business representatives.

4 Business positions concerning private governance regulations in Mauritius, India, Indonesia, the United States, the United Kingdom, and South Africa

This section broadens the scope of the analysis by examining industry responses to private governance regulations in a variety of countries in Africa, Asia, North America, and Europe. Although the treatment of each of these cases is less detailed than the aforementioned EU case, this broad brush survey will help us to assess whether the relationship between public authorities and the private sector is cooperative or conflictual. We begin in Mauritius, where in 2009 the government introduced a mandate stipulating that companies are “to pay 2% of their book profit towards programmes that contribute to the social and environmental development of the country.”Footnote2 The Mauritius Employers Federation stated that it was strongly opposed to this legislation: “The Government's approach to CSR differs from the generally accepted voluntary definition of CSR” and that it had “taken strong position on the matter … CSR is voluntary and cannot be governed by legislation” (CitationMauritius Employers Federation, 2011: 4). This position is consistent with the stance of other employers in this article who reject attempts to co-regulate CSR. However, there is also evidence that “the private sector has taken on board the initiative of the government quite well” (CitationPillay, 2015: 253). If this is true, it leads to the question of what led Mauritian employers to temper or moderate their opposition to the mandatory 2% clause. And it turns out that as the CSR clause was introduced the corporate tax rate was cut from 25% to 15%. It thus appears that mandatory CSR was part of a package deal, a quid-pro-quo for business-friendly reforms — not unlike the situation in the UK in the 1980s, where voluntary CSR engagement was rolled out as a quid-pro-quo for neo-liberal reforms (CitationKinderman, 2012; see also CitationKoos, 2012). Thus in Mauritius CSR “has become firmly entrenched as a development strategy within a broadly neoliberal worldview” (CitationPillay, 2015: 262).

In India in 2013 the Ministry of Corporate Affairs of the governing Congress Party published the Companies Act 2013 which replaces the 1956 Companies Act as the legal framework regulating corporate activities in India. As in the EU, the CSR component of this legislation was an explicit reaction to the failure of voluntary CSR to deliver, in this case contribute to solving the country's massive social and developmental problems. Section 135 of the Bill requires the country's largest listed companies (as defined by size and profitability) to spend 2% of net profit on CSR-related activities. The government had reportedly encouraged companies to make a voluntary commitment, with little effect. It is important to stress that the legislation is not part of an anti-business move on the part of Indian public authorities. Indeed, the 2013 Companies Act can be seen as an integral part of the pro-business shift in India's public policy over recent decades (CitationKohli, 2012). Van Zile suggests that this mandate can be seen as an attempt to legitimate this pro-business shift and disarm its critics:

The Finance Committee, perhaps realizing the popular backlash that might result from such an unabashedly pro-business bill, inserted several new clauses to make the bill slightly more pro-development. The proposal mandating two percent CSR spending was among these clauses (CitationVan Zile, 2012: 293).

The idea of a mandate was first mentioned in 2009 drafts of the Companies Bill. In 2011, India's Minister of Corporate Affairs described section 135 of India's new Companies Act as “the first time and historically it may be the first time in the world” that a country considered mandating expenditures for the public good, rather than simply taxing companies or leaving them to their own devices” (CitationVan Zile, 2012: 294). How did Indian business organizations react? Perhaps India's problems of dire poverty, illiteracy and lack of adequate sanitation have helped convince leading sections of India's business class to endorse this developmental initiative?

Not so. The Indian business community has been unwavering in its resistance to section 135. Beginning in 2009, Indian business representatives such as the Confederation of Indian Industry have sought to replace a legal mandate with voluntary arrangements. When they were unsuccessful, they launched a new attempt to repeal these obligations when the pro-business Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) party led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi came to power in 2014. The minister responsible reported that “The ministry has issued the rules but still the questions on the mandatory CSR provision keep pouring in” (CitationSrivastava, 2014). When the BJP refused to repeal these regulations, Indian business sought to gain tax breaks for the required spending and lengthen the list of activities that would qualify as CSR in order to make the regulations easier to comply with. While India Inc's attempts to dispose of the CSR Mandate in the 2013 Companies Act have been unsuccessful, Indian business representatives were able to restrict the scope or threshold of the law so that it will apply to approximately 8000 or well under 1% of the country's more than one million active companies. Furthermore, they have been able to ensure that noncompliance will not be penalized, as Sambit Saha reports:

‘The board of the companies will only have to report how much they spent on CSR and explain why they couldn’t meet the commitment. The government will not ask them to amplify on that explanation,’ Bhaskar Chatterjee, CEO of the Indian Institute on Corporate Affairs and a former bureaucrat who was instrumental in drafting the CSR guidelines, had said in Mumbai last November (CitationSaha, 2014)

Though cursory, this discussion of suggests that business resistance to corporate mandates is not restricted to advanced industrial countries. Not only industry associations, leading figures in India's business class such as J. J. Irani of the Tata Group also spoke out publicly in opposition to the CSR mandate. One additional detail deserves mention: there are indications that some Indian state officials wish to use this mandate to appropriate corporate CSR assets to fund their own programs (anonymous, personal communication, October 24, 2014). This detail, like the above discussion, underlines the conflictual rather than collaborative relationship between public and private actors. Partnerships, at least functional ones, look different. Next I discuss Indonesia.

In 2007, Indonesia introduced mandatory Corporate Social Responsibility requirements for companies involved in natural resource extraction. According to CitationAndrew Rosser and Donni Edwin (2010), the rise of radical redistributive populist politics as well as predatory elements in the Indonesian state contributed to this initiative. Once the proposal was in parliament, business representatives sought to defeat it:

30 business organizations …. And several business industry associations released a joint statement demanding that the national parliament withdraw mandatory requirements for CSR contained in the draft law and instead provide positive incentives for companies to carry out CSR such as tax concessions …. The statement argued that mandatory requirements for CSR would damage the competitiveness of the Indonesian economy, a loosely veiled threat on the part of these capitalists to relocate their investment resources to other sites if they did not get their way (CitationRosser & Edwin, 2010: 14)

Political representatives responded by “accommodated these demands” and proposing that “CSR funds be treated as an expense (biaya) rather than a deduction from company profits” (CitationRosser & Edwin, 2010: 14).

Employers’ attempts to replace the mandate with voluntarism were unsuccessful. Yet despite these setbacks and even after the parliament had passed the law, “representatives of the dominant sections of capital refused to accept” it (CitationRosser & Edwin, 2010: 16). After unsuccessfully appealing to the constitutional court to have the law declared unconstitutional, “leading business figures moved to defeat Article 74 at the implementing regulation stage (CitationRosser & Edwin, 2010: 16) — and they were able to do so until 2012, when five years after the law was first proposed in the Indonesian parliament, the Indonesian government finally implemented article 74.

As in India, Article 74 of the 2007 Companies Law establishes a formal legal mandate. CSR is compulsory, not voluntary. Unlike the Indian case, noncompliance can be associated with sanctions and penalties. But there is no minimum requirement set in terms of level of expenditure or restrictions in terms of the nature of activities that count as CSR. However, the law leaves it up to company Boards of Commissioners or Annual General Meetings of shareholders to determine what they do in relation to CSR (what activities they fund, how much they spend, etc.) and allows them to record ‘realised’ CSR expenditures as a cost (biaya). This means that CSR-related expenditures are a tax-deductible expense rather than a distribution from profits. So, as Andrew Rosser points out, “while companies can’t do nothing, they don’t have to do much to meet the requirements of the regulation. It is basically up to the Board of Commissioners of AGM to decide what they are prepared to do” (personal communication, October 22, 2014). One additional detail provides an interesting comparison with the Indian case. As Maria Radyati, one of Indonesia's leading CSR experts, remarks: “irresponsible” local governments, NGOs, even community members seek to appropriate companies’ CSR budgets and get companies to “outsource” their CSR to them, sometimes for “fake” programs (personal communication, November 27, 2014). Given the danger that a legal CSR mandate will feed public predation, Radyati maintains that CSR should better be left voluntary (personal communication, November 27, 2014). Next, we survey cases in which governments establish a reporting or disclosure requirement.

We begin with Section 1502 of the U.S. Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, requires certain companies to disclose their use of conflict minerals. “Congress enacted Section 1502 of the Act because of concerns that the exploitation and trade of conflict minerals by armed groups is helping to finance conflict in the DRC [Democratic Republic of the Congo] region and is contributing to an emergency humanitarian crisis.” The law stipulates that “a company that uses any of the designated minerals is required to conduct a reasonable ‘country of origin’ inquiry that must be performed in good faith and be reasonably designed to determine whether any of its minerals originated in the covered countries.”Footnote3 While the law does not place an embargo on minerals from the DRC, it does establish a requirement for disclosure and supply chain due diligence. How have business and industry groups responded?

With “overwhelming opposition” (CitationSarfaty, 2013: 113). In October of 2012, the National Association of Manufacturers, the Chamber of Commerce and the Business Roundtable filed a lawsuit against the Securities and Exchange Commission, asking the SEC to modify or nullify Section 1502. These business organizations cited a number of concerns, including “the financial cost of compliance, which SEC has estimated to be at least $1 billion in initial compliance costs, and $200–$400 million in ongoing compliance costs” (CitationSarfaty, 2013: 111). Some companies with established CSR reputations and supply chain management systems expressed support of Section 1502 and opposed the aforementioned attempts to overturn the legislation (CitationSarfaty, 2013: 113), but the fierce opposition of business in the United States in response to this legislation seems very much in line with business organizations in other countries surveyed in this article. As it turns out, a federal district court handed the SEC a complete victory. For advocates of Section 1502, it is fortunate that the SEC was on solid legal ground, for this allowed Section 1502 to be maintained in the face of vigorous business opposition. We now move on to South Africa, which differs in important respects from the aforementioned cases.

South Africa's King Codes stand out as one of the world's leading inclusive stakeholder-oriented corporate governance frameworks — frameworks which integrate economic, social, and environmental concerns. These codes were issued in 1994 (King I), 2002 (King II), and 2009 (King III), and compliance is mandatory for firms listed on the Johannesburg stock exchange. King II explicitly refers to “align[ing] as nearly as possible the interests of individuals, corporations and society” as well as a triple bottom line approach to accounting. In addition, King II has been referred to as “world class” for its integration of the “four primary pillars of fairness, accountability, responsibility and transparency” (quoted in CitationWest, 2006: 437; 436). King III advocates integrated reporting, which the EU fell considerably short of in its non-financial reporting Directive. Yet unlike the cases of the EU or India or Indonesia, the South African business community has provided little if any resistance to these initiatives. How can we explain this stance? According to Stefan Andreasson,

representatives of businesses and business organisations were quite content with the developments in the King Reports in that they held out hope for a ‘best practice’ being developed in South Africa and that therefore South African businesses, operating in a region about which they felt there are many negative misperceptions, would benefit in terms of attention for positive developments in terms of CSR and a regulatory environment more generally. These kinds of sentiments are of course hard to quantify or measure, but certainly placing South Africa ‘on the map’ in this sense was generally seen as a positive development. [In addition] ‘soft’ and principles-based codes meant businesses felt that they could accommodate them in various not so costly ways (Stefan Andreasson, personal communication, October 20, 2014)

While it is possible that the legacy of Apartheid and the deep inequalities and social divisions it has fostered have instilled a developmentalist stance in South African business, the last point mentioned by Andreasson is particularly important. The King Code is based on an extremely broad and flexible “comply or explain” model: a company can comply by not complying provided they provide a reason or explanation for their noncompliance. This makes it easy for companies to comply. This, I think, is the key reason why South African business advocacy groups have been able to live with these regulations.

Before proceeding to the conclusion, I will briefly discuss the case of the UK, where — it has been claimed — the government “has adopted mandate policies for CSR” through its Companies Act (CitationKnudsen, Moon, & Slager, 2015: 90). As in the South African case and in stark contrast to the EU and India and Indonesia, the British business community has provided very little in the way of resistance to these regulations. In my view, the key explanation is that the UK Companies Act does not challenge core capitalist prerogatives such as shareholder-value. The aforementioned use of the term mandate is potentially misleading given that the UK corporate governance framework is extremely flexible and that it does not challenge shareholder-value. As one scholar has noted:

The Companies Act of 2006 mandates that directors ‘have regard’ for the environmental and social impact of their business operations and disclose economic, social and governance (ESG) risks. CSR has made its way into company law. Yet this culmination of the development of CSR does not appear to challenge the primacy of shareholder-value. Stakeholder interests will be incorporated only to the extent that they are compatible with the prerogatives of ‘enlightened’ shareholders (CitationKinderman, 2012: 50)

summarizes the cases analyzed in Section 4 of this article.Footnote4

The stance of organized business appears to be a function of the stringency of regulation. Where regulation and mandates are stringent, business resistance will be fierce. Where regulation and mandates are flexiblized to the point of being almost voluntary, business will be more supportive. Business organizations support lax and oppose stringent binding arrangements. The next section concludes the article.

5 Conclusion

Conflict and systematic ambiguity about private governance is at the core of this article. When scholars and policymakers talk about private governance, they usually mean a system of governance in which private actors facilitate public goals on public terms — a system that is not really private. By contrast, when business organizations talk about private governance, they mean a system in which public and private actors jointly facilitate goals on private terms — a system that is not really public. Existing scholarship tends to over-state the convergence of public and private actors’ interests.

This article suggests that there is a gap between the way scholars imagine business behavior in private governance and actual business behavior. According to the conventional wisdom, private governance extends regulation to realms where states are weak or dysfunctional, and private governance instruments “tend to supplement rather than supplant traditional public policy regulation” (CitationGulbrandsen, 2004: 77). Jessica Green suggests that it is “useful to conceptualize power as positive sum … public and private authority are not zero-sum”” (CitationGreen, 2014: 164; 163). CitationMaria Gjølberg's (2011) survey of Nordic CSR leaders suggests that these firms favor increased social and environmental regulation.

It's time for a reality check. These scholars imagine a convergence between public and private actors’ interests or business adherence to the spirit, not just the letter of the law. Yet what unifies the diverse cases surveyed in this article is business opposition to regulation. Business lobby groups seek to kill these mandates, or if that is not possible, weaken them as much as they can — even in the EU, which may observers agree is home to the most socially balanced and sustainable capitalist models in the world.Footnote5 Socially responsible fund managers are the only business actors that provided strong support for the EU's non-financial reporting Directive. While my surveys of the non-EU cases are more superficial, I do not have the impression that there is significant cross-national variation in business positions. On the contrary: the argument about business opposition to ‘smart mix’ regulation may be generalizable. The cases of France and Denmark may be exceptions to this rule, and there is some evidence that business opposition was less extreme in Mauritius — but that may be due to the major corporate tax cut which was implemented in conjunction with the CSR mandate there. In cases such as the United Kingdom and South Africa, where there was little in the way of business resistance, the reporting requirements have not imposed substantial burdens on business actors, or they have received concessions in other areas as a quid-pro-quo for these requirements. Given this evidence, the metaphor of a partnership, often used to describe public-private interactions in private governance, is misleading when it comes to RPG. The relationship is too conflictual to qualify as anything but a dysfunctional relationship. This rhetoric may be useful as a sales pitch or an advocacy tool for activists or policymakers, but it does not pass muster as a description of the way the world actually works.

None of this implies naïveté about the benefits of command-and-control regulation.

As Peter Spiro points out, “those inclined to legalized models tend to romanticize the efficacy and state-based regulation, which also suffers from serious flaws” (CitationSpiro, 2013: 1116). And it is true that regulation by itself is far from a silver bullet for the world's myriad governance problems. But as advocates of a smart mix stress, regulation can help, and we should not be too quick to discredit “[t]he solutions of the past, which relied on mandatory participation, public management, and an explicit social contract….” As the historian Avner Offer has persuasively argued in another context, these regulatory solutions “have done a reasonably good job in their time, and have a good deal to teach us still” (CitationOffer, 2006: 372). If state regulation is sometimes a necessary and integral part of such ‘smart mix,’ business resistance poses a serious problem. As Virginia Haufler points out, pressure from civil society or the threat of government intervention are necessary for industry self-regulation: “Without some such countervailing power, effective self-regulation is unlikely” (CitationHaufler, 2001: 113). The analysis in this article suggests that most business organizations do not want governments to regulate or threaten to regulate.

I have said relatively little about why business organizations oppose regulation. In addition to the danger of public predation, Stringham provides some possible answers: he disputes the benefits of public regulation and suggests that it is in fact a hindrance, rather than a help for private governance: “Rather than augmenting private governance, government is often the primary obstacle …. How well private governance solves problems depends on how free it is from government interference …. Overprovision of rules and creeping legalism make the smooth functioning of private governance more and more difficult” (CitationStringham, 2015: 204–205). While new disclosure requirements can provide valuable information and help mitigate certain business risks, they can also be too excessive and costly, and in a rigorously competitive, globalized world, such costs are a liability: “each provider of private governance must compare the marginal benefits and marginal costs of new rules and then adopt only those whose marginal benefits exceeds marginal costs” (CitationStringham, 2015: 196). The main goal of this article is not to intervene directly in debates between advocates of CSR mandates — who believe that the benefits of regulation outweigh their costs — and detractors of public regulation, who claim the opposite. Instead, I have sought to show what happens when public authorities try to implement mandatory or smart mix regulation.

Some observers may wonder whether business business's resistance to regulation is really such a big deal. After all, to cite one example, many welfare state programs have become well-established and effective in spite of employer resistance. In my view there is an important difference between these two examples. In the case of the welfare state, the state is the primary actor. Employer mobilization poses an initial and potentially serious obstacle, but if it is overcome it may cease to pose a critical threat. As welfare state programs gain popular legitimacy, it becomes increasingly difficult to retrench them. But in private governance and in capitalism, firms, business associations and other non-state entities are the central actors. To be politically sustainable and effective, business must support these frameworks. But in many prominent cases, they do not. Here employer resistance poses a much more serious obstacle.

The good news is that once domestic legislation is in place, companies and industry organizations push for a level playing field. If advocates of a smart mix can succeed in implementing domestic regulations, as has happened in France or Denmark, business resistance will decline, business will gradually come to accept regulation, and the likelihood that robust RPG regimes can be established and sustained will increase. Public regulation can be complementary to private regulation (CitationVerbruggen, 2013); and domestic legal frameworks play an important role for private governance arrangements with a hard law component. The bad news is that companies and industry organizations try to prevent, repeal or weaken domestic regulations in the first place, and they often succeed at that endeavor. In addition, even where public authorities have succeeded in implementing domestic legal frameworks, business associations seem more concerned with avoiding administrative costs and replicating domestic regulations at the supranational than with establishing new, truly innovative private governance regimes that are effective for addressing the momentous challenges facing society and business in the contemporary age. If co-governance were truly a source of social innovation and competitive advantage for business, this would be different.

Recent decades have seen the spread of neo-liberal economic policies involving the deep deregulation and privatization of economic life as well as the proliferation of soft law instruments in private governance. If co-governance is truly a countermovement to global neo-liberalism which can establish more socially balanced and sustainable outcomes, firms and business associations — as powerful actors in the private governance arena — must be willing to take a stand and support sensible regulation. Since they are not, we should recognize the idea of a “smart mix” for what it is — wishful thinking. As Streeck reminds us, “That something is needed does not mean that it will be delivered” (CitationStreeck, 2009: 267). The fact that business support is needed does not mean that it will be forthcoming. Business's default position remains opposition to regulation. Scholars and practitioners ignore this at their peril.

Notes

* An earlier version of this paper was presented at the workshop ‘The Causes and Consequences of Private Governance: The Changing Roles of State and Private Actors’ held on 6/7 November 2014 at the Mannheim Centre for European Social Research (MZES). I gratefully acknowledge funding for this event by the COST Action IS1309 ‘Innovations in Climate Governance: Sources, Patterns and Effects’ (INOGOV), MZES, and the Lorenz von Stein Foundation. In addition to the participants of the workshop I would like to thank Jale Tosun, Sebastian Koos, Jennifer Shore, and the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on earlier versions of this article. The usual disclaimers apply.

1 Both Unilever and Ikea are known as frontrunners in responsible business, and both companies have received numerous prizes for their CSR engagement. Perhaps this increased their willingness to sign a letter expressing support for the Directive which civil society campaigners associated with the European Coalition for Corporate Justice had initiated.

2 http://www.csr.mu/.

3 http://www.sec.gov/News/Article/Detail/Article/1365171562058.

4 Because the positions of different countries in relation to the EU NFR Directive varied significantly, and because the text of the proposal as well as the positions of some countries changed significantly over time, I have chosen not to include the EU NFR Directive in this figure.

5 Of course it is logically possible that businesses could pursue high road strategies in practice while weakening regulations as much as possible, but I consider this to be unlikely for a number of reasons.

References

- K. Buhmann . Reflexive regulation of CSR: A case study of public-policy interests in EU public-private regulation of CSR. International and Comparative Corporate Law Journal. 8(2): 2011; 38–76.

- K. Buhmann . Integrating human rights in emerging regulation of Corporate Social Responsibility: The EU case. International Journal of Law in Context. 7(2): 2011; 139–179.

- EU strategy 2011–2014 for corporate social responsibility. Position paper. 9th January. 2012

- BusinessEurope . Disclosure of non-financial information. Position paper. July 5. Brussels. 2013

- Sir G. Chandler . CSR — The way ahead or a Cul de sac?. J. Henningfeld , M. Pohl , N. Tolhurst . The ICCA handbook of corporate social responsibility. 2006; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester 61–68.

- Eurochambres . European Commission's proposal for a Directive on disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large companies and groups COM(2013)207. Position Paper. Brussels. October. 2013

- European Coalition for Corporate Justice . Press release — European parliament votes for rules on corporate accountability and business transparency. April 14. Brussels. 2014

- European Commission . Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. A renewed EU strategy 2011–14 for Corporate Social Responsibility. COM 2011(681) final. October 25. 2011

- European Commission . Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Council Directives 78/660/EEC and 83/349/EEC as regards disclosure of nonfinancial and diversity information by certain large companies and groups. April 16. Strasburg. 2013

- Eurosif . Newly approved European legislation on non-financial information disclosure sends strong signals to companies, but falls short of responsible investors’ expectations. Press Release, April 15. Brussels. 2014

- J. Fairbrass . Exploring corporate social responsibility policy in the European Union: A discursive institutionalist analysis. Journal of Common Market Studies. 49(5): 2011; 949–970.

- A. Favotto , K. Kollman , P. Bernhagen . Engaging firms: The global organisational field for corporate social responsibility and national varieties of capitalism. Policy and Society. 35(1 Co-governance of Common Goods): 2016; 13–27.

- M. Gjølberg . Explaining regulatory preferences: CSR, soft law, or hard law? Insights from a survey of Nordic pioneers in CSR. Business and Politics. 13(2): 2011

- J.F. Green . Rethinking private authority: Agents and entrepreneurs in global environmental governance. 2014; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ

- L.H. Gulbrandsen . Overlapping public and private governance: Can forest certification fill the gaps in the global forest regime?. Global Environmental Politics. 4(May (2)): 2004; 75–99.

- V. Haufler . A public role for the private sector: Industry self-regulation in a global economy. 2001; Carnegie Endowment for International Peace: Washington, DC

- D. Kinderman . ‘Free us up so we can be responsible!’ The co-evolution of Corporate Social Responsibility and neo-liberalism in the UK, 1977–2010. Socio-Economic Review. 10(1 Co-governance of Common Goods): 2012; 29–57.

- D. Kinderman . Corporate social responsibility in the EU, 1993–2013: Institutional ambiguity, economic crises, business legitimacy and bureaucratic politics. Journal of Common Market Studies. 51(July (4)): 2013; 701–720.

- J.S. Knudsen , J. Moon , R. Slager . Government policies for corporate social responsibility in Europe: A comparative analysis of institutionalization. Policy & Politics. 43(1 Co-governance of Common Goods): 2015; 81–99.

- A. Kohli . Poverty amid plenty in the New India. 2012; Princeton University Press: Princeton

- S. Koos . The institutional embeddedness of social responsibility: A multilevel analysis of smaller firms’ civic engagement in Western Europe. Socio-Economic Review. 10(1 Co-governance of Common Goods): 2012; 135–162.

- R.M. Locke . The promise and limitations of private power. 2013; Cambridge University Press: New York

- Mauritius Employers Federation . Survey report on the practical implementation of CSR under the new legislation. Ebene CyberCity. 2011

- F.W. Mayer . Leveraging private governance for public purpose: Business, civil society and the state in labour regulation. A. Payne , N. Phillips . Handbook of the international political economy of governance. 2014; 344–360.

- C.N. Murphy . Privatizing environmental governance. Book review essay. Global Environmental Politics. 9(August (3)): 2009; 134–138.

- P. Nonet , Philip Selznick . Law and society in transition: Toward responsive law. 1978; Harper/Colophon: New York

- D. O’Rourke . Outsourcing regulation: Analyzing nongovernmental systems of labor standards and monitoring. Policy Studies Journal. 31(1 Co-governance of Common Goods): 2003; 1–29.

- A. Offer . The challenge of affluence: Self-control and well-being in the United States and Britain since 1950. 2006; Oxford University Press: Oxford

- L. Orly . Renew deal: The fall of regulation and the rise of governance in contemporary legal thought Minnesota law review. Vol. 89 2004, November; 262–390.

- R. Pillay . The changing nature of corporate social responsibility: CSR and development in context — The case of Mauritius. 2015; Routledge: Abingdon

- A. Rosser , D. Edwin . The politics of corporate social responsibility in Indonesia. Pacific Review. 23(1 Co-governance of Common Goods): 2010; 1–22.

- J.G. Ruggie . Just business, multinational corporations and human rights. 2013; W. W. Norton: New York

- S. Saha . Tax break eludes CSR spend. Telegraph India. 2014, July

- P.J. Spiro . Constraining global corporate power. Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law. 46 2013; 1101–1118.

- G. Sarfaty . Human rights meets securities regulation. Virginia Journal of International Law. 54 2013; 97–126.

- S. Srivastava . Corporate affairs ministry flags CSR review for new minister. Indian Express. 2014, May

- W. Streeck . Re-forming capitalism: Institutional change in the German political economy. 2009; Oxford University Press: Oxford

- W. Streeck . Taking capitalism seriously: Towards an institutionalist approach to contemporary political economy. Socio-Economic Review. 9(1 Co-governance of Common Goods): 2011; 137–167.

- E.P. Stringham . Private governance: Creating order in economic and social life. 2015; Oxford University Press: New York

- J. Tosun , S. Koos , J. Shore . Co-governing common goods: Interaction patterns of private and public actors. Policy and Society. 35(1 Co-governance of Common Goods): 2016; 1–12.

- J. Tosun , A. Wetzel , G. Zapryanova . The EU in crisis: Advancing the debate. Journal of European Integration. 36(3): 2014; 195–211.

- C. Van Zile . India's mandatory corporate social responsibility proposal: Creative capitalism meets creative regulation in the global market. Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal. 13(2): 2012; 269–303.

- P. Verbruggen . Gorillas in the closet? Public and private actors in the enforcement of transnational private regulation. Regulation & Governance. 7 2013; 512–532.

- D. Vogel . The market for virtue: The potential and limits of corporate social responsibility. 2005; The Brookings Institution Press: Washington, D.C.

- A. West . Theorising South Africa's corporate governance. Journal of Business Ethics. 68 2006; 433–448.