Abstract

This article examines banking structural reforms introduced in the European Union (EU), placed in an international context. The concept of ‘regulatory cascading’ is put forward to investigate how European policy-makers tackle complex multi-faceted problems, such as that of banks which are ‘too big to fail’. The article shows that partial solutions to the problem introduced in other areas of banking regulation, coupled with strategic activism at the domestic level by key EU member states have constrained the opportunities to design a coherent EU framework regulating bank structures. In response to the Commission's proposal for harmonised European banking structural reforms, the Council has stressed in its position two approaches that closely correspond to the measures adopted in France and Germany, on the one hand, and the UK, on the other hand.

1 Introduction

The 2008 crisis revealed that financial globalisation and de-regulation, especially in states with large financial centres such as the United States (US) and United Kingdom (UK), threatened financial stability (CitationGermain, 2012). The long-term viability of the global financial system depends not only on launching innovative products but also on introducing robust risk management practices. Hence, scholars, policy-makers, and stakeholders have called for more rigorous financial sector oversight (CitationFerran, Moloney, Hill, & Coffee, 2012; Moloney, 2011; Vickers et al., 2011; Wymeersch, 2012).

In the European Union (EU), policy-makers engaged in protracted negotiations to further centralise authority in banking supervision and harmonise regulatory practices across the member states. They conferred greater monitoring and rule-making powers to the three European financial sector agencies, adopted stricter capital adequacy requirements in line with the Basel III international standards, and moved forward with establishing a European Banking Union (EBU) (CitationFerran et al., 2012; Howarth & Quaglia, 2016a Citation; Lastra, 2003; Masciandaro & Eijffinger, 2011 Citation; Moloney, 2011; Quaglia, 2010; Spendzharova, 2014).

At the same time, regulators, financial industry firms, and stakeholders have struggled to keep abreast of the rapid sequence of policy and institutional reforms adopted at the European and international level. The most recent rounds of EU banking sector reforms coincided with the launch of the new ‘Better Regulation’ programme, designed to ‘ensure that European Union (EU) laws and policies are prepared, implemented, and reviewed in an open and transparent manner, informed by the best available evidence, and responsive to stakeholder input’ (CitationEuropean Commission, 2015: 4–5; see also CitationMeuwese, Scheltema, & van der Velden, 2015; Radaelli, 2007; Smismans, 2015). As part of the EU's commitment to designing effective and coherent policies, the European Commission has conducted extensive stakeholder consultations and regulatory impact assessments before proposing new legislation (CitationAlemanno, 2015; De Francesco, Radaelli, & Troeger, 2012; Dunlop, Maggetti, Radaelli, & Russel, 2012).

CitationBakir and Woo (2016) refer to policy design as ‘deliberate governmental efforts at attaining desired policy objectives’. One of the core aims of policy design is to produce policy tools and instruments facilitating the attainment of policy goals (see also CitationHowlett & Lejano, 2013; Howlett, 2011; Woo et al. (in this volume)). Furthermore, CitationWoo et al. (in this volume) highlight the importance of regime coherence at the domestic and international level in order to achieve optimal policy design. However, in practice, mismatches in coherence occur frequently. For example, highly coherent domestic regimes may intersect with incoherent international regimes. CitationWoo et al. (in this volume) point out that this scenario may produce regulatory capture. This article adds first insights into another limitation of policy design, which I refer to as ‘regulatory cascading’.

In line with one of the central goals of this special issue — to provide a clearer and deeper understanding of the underlying processes shaping financial regulation reform — this article focuses on the interests of the public and private sector actors seeking to shape banking sector reforms in the EU (see also CitationHowarth & Quaglia, this volume; Méró & Piroska, this volume). In particular, I investigate banking structural reforms introduced in the European Union (EU), placed in an international context. One of the main aims of banking structural reforms at all governance levels is to streamline and simplify bank structures, thus facilitating the resolution of large internationalised banks in times of crisis.

Analysing EU banking structural reforms provides us with a better understanding of how governments and the financial industry are managing the cumulative impact of rapid institutional and regulatory reforms (see also CitationQuaglia, 2008; Pagliari & Young, 2014; Young, 2014). This investigation is especially relevant in a multi-level polity such as the EU because it allows us to capture the interplay of international, (macro-)regional, and domestic banking sector reforms initiated after 2008 (see also CitationQuaglia, 2014a, 2014b; Mügge, 2014).

In Section 3, the concept of ‘regulatory cascading’ is put forward to examine how European policy-makers tackle complex multi-faceted problems, such as ‘too big to fail’. Partial solutions to the problem introduced in a rapid sequence of reforms in capital adequacy rules, bank supervision, and bank resolution regimes have constrained the opportunities to design a coherent EU framework regulating bank structures. Furthermore, the article investigates the repercussions of regulatory cascading for the coherence and effectiveness of the new policies. I argue that the quick accumulation of new regulatory standards and policy instruments poses significant challenges for policy-makers and stakeholders. By necessity, the policy evaluation tools used by the European institutions operate on a slower time scale than the widely-used stakeholder consultation tools. So far, policy evaluation, including ex ante economic impact assessment, has not captured fully the interactions between different strands of reform and unintended consequences of regulatory cascading.

What issues stand out in European banking structural reforms and which stakeholders will be affected the most? The CitationEuropean Commission's (2014a: 7) legislative proposal contains two main elements: ‘a ban on proprietary trading’ and ‘mandatory separation of some trading activities from the deposit-taking entity.’ Existing EU legislation, such as the Capital Requirements Directive IV (CRD IV) and the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) Regulation, was desirable from the point of view of regulators and the financial industry, as it guaranteed a European level playing field, created a single supervisory contact point, and a single rulebook in banking. By contrast, analysts have pointed out that the proposed EU banking structural reforms will generate high compliance costs and require a substantial redesign of banks’ business models. The high adjustment costs are expected to have especially adverse effects on universal banks in Europe, which rely on both deposit-taking and market-making activities (CitationDeloitte, 2015; Hardie & Macartney, 2016; Spendzharova, Versluis, Flöthe, & Radulova, 2016).

In the following sections, I first take stock of banking structural reforms placed in an international context. Next, I outline the concept of ‘regulatory cascading’ in EU banking structural reforms. After that, I examine the reforms adopted in individual EU member states and analyse the positions of the European Parliament and Council on the legislation proposed by the European Commission. Lastly, the conclusion summarises the main findings.

2 Banking structural reforms in a global perspective

In order to position the proposed EU legislation on banking structural reforms in a global perspective, this section dicusses similar measures implemented in other jurisdictions. The desired effect of these reforms is to ‘reduce systemic risk, enhance depositor protection, and limit the need for state-led bailouts’ (CitationFSB, 2014: 1). Severely affected by the 2008 global financial crisis, the USA and the UK were front-runners in adopting banking structural reforms as early as 2010. Policy-makers in the two countries have been very active in the international efforts to mitigate the problem of banks which are ‘too big to fail’ partly for structural reasons: their jurisdictions are home to global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) and host to foreign G-SIBs. The crux of the reforms adopted in the USA and the UK was to ‘protect the deposit-taking parts of banking groups by insulating them from risks stemming from trading activities’ (CitationFSB, 2014: 3). Moreover, policy-makers aimed to simplify the legal and operational structures of large internationalised banks. The reforms would also make it easier to supervise and resolve G-SIBs in times of crisis and limit the exposure of taxpayers to bank bail-outs.

At the international level, the G20 has been actively engaged in coordinating the measures adopted in different jurisdictions. In 2013, the Basel-based Financial Stability Board (FSB) received a request from the G20 to review and report on the range of banking structural reforms adopted in different jurisdictions, using input from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (CitationFSB, 2014: 3). A broad aim of many banking structural reforms was ‘to introduce a separation between certain core banking activities, such as payment systems and retail deposit-taking, and the risks emanating from investment banking and capital market activities’ (CitationFSB, 2014: 3). According to the FSB, banking structural reforms would also help to streamline the complex organisational and operational structures of G-SIBs, which make it very difficult to resolve these cross-border banking groups in an orderly manner. In addition, many states adopted stricter rules on capital adequacy, in line with the Basel III Accords, to ensure that banks have sufficient capital to withstand periods of distress.

The USA was the first jurisdiction to adopt banking structural reforms after 2008 by putting in place the Volcker Rule, the Swaps Push-Out Rule, and the Foreign Banking Organisations Rule (CitationFDIC, 2014). A provision of the Dodd–Frank Act, the Volcker Rule prohibits US and foreign banking entities in the US from engaging in proprietary trading, defined as ‘short-term, speculative risk-taking that is separate from activities performed for a client’ (CitationFSB, 2014: 10; CitationFDIC, 2014: SEC. 619). The core objective of the Volcker Rule is to limit the exposure of insured deposit-taking entities operating in the US to what are perceived as riskier trading activities. The rule is applicable to the domestic and foreign activities of US banks as well as the activities of foreign banks operating in the US, but it contains some important exemptions, such as ‘all banking entities are permitted to engage in proprietary trading in US government debt instruments’ (CitationFSB, 2014: 5). Furthermore, foreign banks operating in the US are allowed to ‘engage in proprietary trading in their home country's government debt securities’ (CitationFSB, 2014: 5). Second, the Swaps Push-Out Rule is also part of the Dodd–Frank Act. This rule prohibits the granting of US federal assistance, ‘including Federal Reserve discount window access and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) deposit insurance’, to legal entities operating as swap dealers or major swap participants, security-based swap dealers or major security-based swap participants (CitationFSB, 2014: 6; CitationFDIC, 2014: Sec. 731).

Third, according to the Foreign Banking Organisations Rule, foreign banking entities which hold in the US non-branch assets of 50 billion or more ‘must use a US intermediate holding company (IHC) in order to organise their subsidiaries’ (CitationFSB, 2014: 6). In turn, this holding company should comply with capital, capital planning, liquidity, and stress testing requirements similar to those applicable to regular US bank holding companies (BHCs)’ (CitationFSB, 2014: 6; CitationFDIC, 2014: Sec. 616). The rule does not push foreign banks out of the US market. The goal is rather to establish a greater proportionality between the risks taken by foreign banks in the US and the amounts of capital and liquidity that these entities are obliged to hold. All in all, from the point of view of US regulators, the Foreign Banking Organisations Rule ensures greater insight into and powers to influence foreign banks operating in the country.

3 Regulatory cascading in European banking structural reforms

Drawing on findings in the international relations and public policy literature, this section identifies a limitation of policy design in complex policy-making systems, which I refer to as ‘regulatory cascading’ — an example of overregulation in the aftermath of crises.

In order to manage the domestic financial system, public sector actors interact with international organisations (IOs), transnational regulatory networks, and private firms (CitationFerran et al., 2012; Hardie & Howarth, 2013; Mattli & Büthe, 2005 Citation; Quaglia, 2010; Quaglia, 2014b; Singer, 2007; Wymeersch, 2012). In the international relations field, CitationGenschel and Zangl (2014: 339) have argued that the acceptance of regulation by the citizens as legitimate requires that the people can ‘throw the government out’ in free and fair elections if it fails to produce the desired public goods. Neither international organisations nor private actors can be ‘thrown out’ if regulatory reforms fail. Thus, the state remains the basic unit of authority in OECD countries, even when we take into account the increased role of international organisations and the private sector in governance decisions. Yet, the role of the state has changed ‘from virtual monopolist of political authority to key manager of partly privatised and internationalised political authority’ (CitationGenschel & Zangl, 2014: 338).

In the realm of banking structural reforms, policy change has been taking shape simultaneously at the national, European, and international level. This has raised policy design dilemmas as outlined in CitationOstrom's (1961, Citation2010) work on polycentric governance, where many decision-making arenas interact in the policy system. In the EU, in particular, the member states are important actors in the decision-making process; they seek to assert their preferences when new EU policies are designed and negotiated.

At the same time, in the public policy literature, CitationCapano, Howlett, and Ramesh (2015: 5) have shown that monopolistic governance arrangement based on hierarchical command and control by the central government are no longer suitable to tackle complex policy problems (see also CitationCapano, Rayner, & Zito, 2012; Héritier & Lehmkuhl, 2008). Furthermore, according to CitationCapano et al. (2015: 6), the effectiveness of new governance arrangements such policy networks and collaboration with the private sector is closely linked to the presence and actions of public sector organisations.

In this more complex policy system, states have to cooperate with this larger set of actors in order to solve problems and cope with regulatory challenges (see also CitationCoen & Thatcher, 2008; Dehousse, 1997; Eberlein & Grande, 2005; Eberlein & Newman, 2008). Of particular relevance for my analysis are shortcomings of policy design, which may lead to governance failure. On the one hand, scholars have pointed out that regulatory capture is a governance pathology at the extreme end of the private governance mode, lacking systematic public oversight (CitationBaker, 2010; Grossman & Woll, 2014; Pagliari & Young, 2014 Citation; Porter, 2012; Spendzharova, 2008; Young, 2012). On the other hand, during the period of rapid financial globalisation, scholars examined the pitfalls of cumbersome legislation which lags behind current market practices and conditions (CitationBarth, Caprio, & Levine, 2006). While regulatory capture has been well-documented in the literature, this article aims to add new conceptual insights about what I refer to as ‘regulatory cascading’ — an example of overregulation in the aftermath of crises (see also CitationSpendzharova et al., 2016: 134).

While US policy-makers moved quite quickly with adopting banking structural reforms, progress at the supranational EU level has been slow. The two EU co-legislators, the European Parliament and Council, are currently considering the CitationCommission's (2014a: 7) proposal for a Regulation on Banking Structural Reform, which consists of ‘a ban on proprietary trading’ and ‘separation of certain trading activities from the deposit-taking entity.’

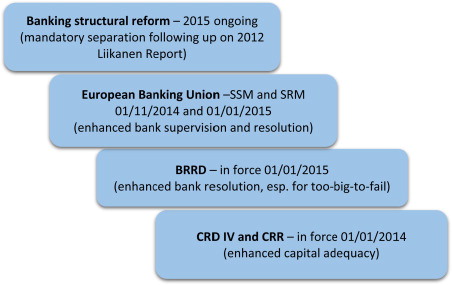

However, if adopted, the reforms proposed by the Commission will add another layer of reforms to existing EU legislation in the areas of capital adequacy, bank supervision, and bank resolution (CitationSpendzharova et al., 2016: 137). To provide a visualisation of regulatory cascading, presents the timing and purpose of major legislative packages such as the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD IV), Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR), Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD), Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM), Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM), and the 2012 Liikanen Report. All EU legislative packages in contribute partial solutions to the problem of banks that are ‘too big to fail’ in areas related to banking structural reforms, such as introducing higher capital adequacy standards (CRD IV, CRR), an enhanced role of the SSM and SRM in bank supervision and resolution in the Euro area (European Banking Union), and more transparent arrangements in cross-border bank resolution (BRRD).

Fig. 1 Regulatory cascading in European banking structural reforms (CitationSpendzharova et al., 2016: 136).

All in all, CitationHowlett and Rayner (2007: 7) have examined a variety of ‘integrated strategies’ in policy design, through which governments attempt to achieve ‘coherent policy goals, relying on a consistent set of policy instruments that support each other in the achievement of the policy goals’. However, we do not observe a deployment of these strategies in order to streamline the proposed EU banking structural reforms. This shortcoming of policy design speaks to recent work in historical institutionalism, where scholars have found inconsistencies and contradictions in reforms during periods of rapid policy layering (CitationThelen & Mahoney, 2015).

The wide-spread sentiment among the general public and policy-makers that the global banking sector has become too detached from serving citizens and the ‘real’ economy has been an important driver of regulatory cascading in EU banking structural reforms (see also CitationFerran, 2012; Rosas, 2009; Seabrooke, 2010). Individual member state governments and EU decision-makers have pledged to enact stringent reforms to rein in risk-taking in the banking sector. Taxpayers in EU member states such as the UK, Ireland, Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Belgium have borne the cost of bail-outs of large internationalised banks in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis (CitationWoll, 2014). The governments of many EU member states have vowed, in turn, to implement reforms that will make similar bail-outs less likely in the future and will force banks’ shareholders and creditors to shoulder the cost of bank failures (CitationSchmidt, 2014). At the international level, EU governments have also made commitments to reform banking structures in the G20 framework (CitationFSB, 2014).

To remedy the broad public dissatisfaction with banks that have become a liability, each legislative package in aims to make the European banking sector more resilient during crises. CRD IV and CRR focus on rules to make banks better capitalised, so that they can withstand better periods of distress. BRRD and the European Banking Union, especially the SRM, focus on making banking structures more streamlined, so that cross-border banks can be resolved with the least negative impact on their depositors and customers (see also CitationEpstein & Rhodes, 2016; Howarth & Quaglia, 2016a; Kudrna, 2016; Spendzharova & Bayram, 2016). Yet, the analysis below sheds light on the challenges of dealing with the cumulative effect of these cascading reforms and overlap between different legislative packages adopted in close temporal proximity in order to address specific aspects of the complex policy problem of banks which are ‘too big to fail’.

Turing to the main policy focus of this article, EU banking structural reforms, in 2014, the European Commission introduced a proposal for common EU legislation on banking structural reforms in order to put in place a coherent European framework. The main objective of the draft legislation is to ‘reduce the systemic risk associated with the largest, most complex, and interconnected banks that engage in market-based trading activities’ (CitationEuropean Commission, 2014a: 2–3). This will be accomplished by insulating the core deposit-taking business structurally and operationally from investment banking activities, which should be located in a separate legal entity. These measures would also make large internationalised banking groups more resilient and more resolvable. Furthermore, the 2014 Commission's proposal is accompanied by a detailed economic impact assessment study (CitationEuropean Commission, 2014b). The CitationCommission's (2014b: 24) analysis lists a number of anticipated benefits for the EU's single market, such as ‘enhanced financial stability within the EU, better integrated financial markets, orderly resolution and recovery, enhanced cross-border provision of services, reduced competitive distortions, and less regulatory arbitrage’.

The 2012 Liikanen report has provided a template for the subsequent EU legislative proposal. Michel Barnier, then EU Commissioner for Internal Market and Services, established a High-level Expert Group (HLEG) on structural bank reforms in February 2012 ‘in order to assess the need for additional reforms to reshape the structure of Europe's banks’ (CitationLiikanen et al., 2012: i). The HLEG recommended a set of five measures which ‘augment[ed] and complement[ed] the set of regulatory reforms already enacted or proposed by the EU, the Basel Committee and national governments’ (CitationLiikanen et al., 2012: iii).

The final version of the CitationLiikanen (2012: ii) report advised in favour of ‘a mandatory legal separation of riskier investment activities from the core deposit-taking activities within a banking group.’ The central objectives of mandatory ownership separation are to make banking groups, especially their core deposit-taking and retail banking operations more insulated from risks emanating from a wide range of trading activities. This, in turn, would limit the implicit or explicit taxpayer guarantee for the investment parts of banking groups.

summarises nine policy options for EU-wide banking structural reforms, representing different combinations of the range of activities to be separated and the strictness of required separation. For example, policy option ‘A’ stands for the least restrictive option for bank structural reforms and would entail the lowest adjustment costs for the banking sector, whereas policy option ‘I’ stands for the most restrictive separation of trading activities and strictest ownership separation. Option ‘I’ would be detrimental to the current business model of universal banks in the EU, which engage in both deposit-taking and trading activities.

Table 1 Policy options for EU-wide banking structural reforms (adapted from CitationEuropean Commission, 2014b: 34).

The following paragraphs discuss the policy implications of the different calibrations of range of activities to be separated and the strictness of required separation. In the narrow trading entity and broad deposit entity model only a few trading activities are separated from the deposit-taking entity. The medium trading and medium deposit taking entity model means that more trading activities, such as market-making, are separated from the deposit-taking entity. At the same time, market-making generates substantial revenues for EU banking groups. Thus, separating this type of activity from the deposit-taking entity is seen as detrimental to banks’ business model. Moving to the last model in the table, in the broad trading entity and narrow deposit entity combination a broad range of trading activities, such as underwriting, brokerage services and derivatives transactions, are separated from the deposit-taking entity and can only be performed by another trading entity, such as an investment bank.

With regards to the three policy options for ownership separation, the accounting separation model entails a light restructuring of the banking group, mostly for accounting purposes to introduce greater transparency and insight into the transactions of the trading and deposit-taking entities. In practice, the banking group would continue to provide integrated financial services. The next model, subsidiarisation, refers to the legal separation of the deposit-taking and trading business units into separate legal entities. This type of restructuring is necessary for the ring-fencing reforms introduced in the UK. Lastly, strict ownership separation is the most intrusive model of banking structural reforms. The banking group would need to separate the ownership of assets into different firms that may not be affiliated with each other. This approach was used in the US under the 1933 Glass—Steagall Act until two of its major provisions were repealed by the 1999 Gramm—Leach—Bliley Act.

The proposed EU reforms would simplify bank structures and insulate the core deposit-taking entity from potential losses in the trading entity, but they are also likely to have a negative effect on the risk diversification within the banking group and level of intermediation in the broader economy (see CitationHakenes & Schnabel, 2014; Huertas, 2015). In particular, the full ownership separation options (C, F, and I), also envisioned in the Liikanen report, would require that the deposit-taking entity and investment-oriented entities be fully distinct in legal, economic, governance, and operational terms.

Once adopted, the reforms would apply to banks operating in all 28 EU member states, including the EU subsidiaries of non-EU banks. They will have a significnat impact on the activities and operations of EU-based banks identified as ‘being of global systemic importance’ and/or banks exceeding certain thresholds, such as ‘€30 billion in total assets, and trading activities either exceeding €70 billion or 10% of the bank's total assets’ (CitationEuropean Commission, 2014a: 7). Under the proposed rules, banks will also face restrictions on proprietary trading when this is done without a connection to trading for a specific client. Similarly to US legislation under the Volcker Rule, trading in EU sovereign debt is exempt from the restrictions on proprietary trading (see CitationEuropean Commission, 2014: 7–8).

At the same time, it is important to understand the unintended consequences of overlapping and cumulative reforms. The Commission invited EU banks and other stakeholders to estimate and discuss the impact of the proposed variants of banking structural reforms, while taking into account the interaction with EU legislation in related areas, such as CRD IV, CRR, and BRRD. Demonstrating the difficulty of conducting such an assessment ex ante, the Commission reports that very few banking groups actually responded to this query and ‘the simulated impacts…differed substantially between respondents and gave rise to inconsistencies both within a given set of results and between different sets of estimated impacts’ (CitationEuropean Commission, 2014b: 67). In line with best practices in the ‘Better Regulation’ agenda, the Commission paid careful attention to the views of stakeholders, including the financial industry and consumer organisations. As we can see in , the Commission conducted two online stakeholder consultations dedicated to EU banking structural reforms and one on-site stakeholder meeting in Brussels. The 2013 online stakeholder consultation asked organisations and individuals to comment on the nine reform options presented in and the feedback was subsequently taken into account in the 2014 legislative impact assessment.

Fig. 2 Timing of banking structural reforms (BSR) at the international, European, and domestic level of the EU member states.

Furthermore, the CitationCommission's (2014b) legislative impact assessment considered the international dimension of banking structural reforms, impact on stakeholders, and potential overlaps with ongoing reforms in the EU member states. However, the assessment stressed that ‘the final balance between the additional benefits in terms of improved ex ante financial stability versus the increased costs in terms of foregone economies of scale and scope and operational costs in this instance is more a matter of political choice than technical ranking’ (CitationEuropean Commission, 2014b: 65). This finding confirms CitationAlemanno's (2015) conclusion that political discretion and inter-institutional bargaining still dominate the EU policy-making process, even after the launching the new ‘Better Regulation’ agenda.

As illustrated in , the European Commission has carefully planned monitoring and policy evaluation of banking structural reform legislation, but its current toolbox of measures works on a slower time scale. For example, the Commission will monitor the impact of legislation on the banking sector during the phase-in period, but, by necessity, ex-post evaluation is planned for about four years after the implementation deadline (CitationEuropean Commission, 2014b: 81). Commission staff will assess whether the legislation has achieved its objectives and whether any new measures or amendments are necessary. In the meantime, however, both regulators and banks will have to cope with overlapping reforms and any unintended consequences.

4 Banking structural reforms in the EU member states and Council's position

Having considered the international and European dimension of banking structural reforms, we now turn to examining how preceding domestic reforms in the EU's member states have limited the options for coherent policy design at the European level. While the common EU legislative measures are still under negotiation, individual member states such as the UK, France, and Germany have already introduced domestic banking structural reforms explained in greater detail below.

The EU member states which strategically moved first to introduce domestic banking structural reforms are the UK, Germany, and France. All three countries are home to global systemically important banks (G-SIBs), such as HSBC, Deutsche Bank, BNP Paribas and Crédit Agricole. Even though Belgium currently does not have any G-SIBs, it has introduced measures similar to those adopted in France and Germany. However, many other member states which are home to G-SIBs, such as Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden have not yet put in place domestic banking structural reforms. Instead, they have opted to wait for the harmonised EU-wide measures.

To begin with, the main two reforms that have been put in place in the UK refer to the so-called ‘ring-fencing’ of core banking activities and a new authorisation procedure for UK branches of foreign banks (CitationBank of England, 2014: 5–6). With regards to ring-fencing, the UK's Financial Services (Banking Reform) Act of 2013 implements the advice of the Independent Commission on Banking, which was set up in 2010 in response to the global financial crisis (CitationBank of England, 2014: 5). The main objective of ring-fencing is to insulate the provision of core banking services from what are perceived as riskier trading activities (CitationJames, 2015; Hardie & Macartney, 2016). In practice, this means that if a UK bank has more than £25 billion of aggregated core deposits, such as retail deposits, overdrafts, and related payments services, these need to be placed in a subsidiary called a ‘ring-fenced body’ which must be legally, financially, and operationally independent from the rest of the corporate group (see CitationFSB, 2014: 7). The 2013 Banking Reform Act prohibits the ring-fenced body from engaging in a range of investment banking activities.

Furthermore, the structural reforms implemented in the UK are intended to ‘enhance the resolvability of both ring-fenced bodies and their wider groups’ (CitationBank of England, 2014: 5). Considering the complex organisational and operational structure of large internationalised banking groups, these measures fit with the post-2008 efforts at the international level to develop effective resolution regimes, especially for G-SIBs. At the same time, the ring-fencing reforms adopted in the UK are sensitive to the fact that different divisions of the same banking group may have different systemic impact on the UK's financial system. Thus, different divisions of the banking group may be subject to tailored capital and loss absorbency requirements rather than uniform ones. Ring-fencing also applies to the UK subsidiaries of non-UK banks if they possess more than £25 billion of aggregated core deposits (CitationFSB, 2014: 7). However, the branches of foreign banks in the UK and the overseas subsidiaries of UK banks are outside the scope of the reforms.

The UK's Prudential Regulatory Authority's (PRA) will play a key role in assessing whether and how foreing banks will operate in the country without posing serious risks to finanical stability in the UK. For bank branches from outside the European Economic Area (EEA), the PRA's assessment will consider three main factors: ‘(1) whether the supervision of the entity in its home state is equivalent to that of the UK; (2) the activities undertaken by the branch; and (3) whether the UK supervisor has assurance from the home supervisor over the firm's resolution plan in a way that reduces the impact on financial stability in the UK’ (CitationFSB, 2014: 8). At the end of the assessment process, the PRA will issue a judgement whether the bank can operate as a branch in the UK.

Apart from the UK, France and Germany have also adopted domestic banking structural reforms. The measures put in place in France and Germany largely follow the conclusions of the 2012 Liikanen report. They aim to protect the deposit-taking banking entity, and its essential functions in the country's banking system, from risks arising from trading activities. In both states, if a deposit-taking entity exceeds certain thresholds, it must either discontinue a range of trading activities or transfer those activities to a trading entity which is economically, operationally, and legally separated from the core deposit-taking credit institution (CitationDeloitte, 2015; FSB, 2014: 10).

The new rules also prohibit certain relations with hedge funds and proprietary trading, defined as ‘an acquisition and sale of financial instruments on the institution's account, without a service for third parties, except when used for prudent hedging and management of the institution's capital’ (CitationFSB, 2014: 10). At the same time, market-making activities can still be carried out by the deposit-taking entity. Allowing universal banks to engage in both deposit-taking and market-making is seen as essential to guarantee the viability of this banking model, which is very important in both the French and German banking system (CitationDeloitte, 2015; Hardie & Macartney, 2016). Furthermore, the national banking supervision authorities have received new powers to enforce the separation of market-making activities if they threaten the solvency of the deposit-taking entity.

How does the existence of domestic banking structural reforms in the member states affect the harmonisation of these reforms at the EU level? The Commission's 2014 legislative proposal was subject to heated debates in the two EU institutions responsible for co-legislating — the European Parliament and Council. In December 2014, the European Parliament's ECON committee rapporteur on banking structural reforms, Gunnar Hökmark, released a report which watered down the Commission's proposal and put forward 90 amendments (CitationEuropean Parliament, 2015). The amendments significantly reduced the number of banks affected by the Commission proposal and suggested that full ownership separation was just one option in a supervisor's toolkit. However, the ECON committee vote in May 2015, resulted in rejecting the proposed amendments and a failure to reach a common position (30—29, one abstention).

The other EU co-legislator, Council, also amended significantly the Commission's 2014 legislative proposal during its June 2015 meeting, prepared by the Luxembourg Council Presidency. Rather than using the two solutions in the original 2014 Commission proposal, which focused on a ban on proprietary trading and separation of certain trading activities from the deposit-taking entity, the Council took a different position.

As the EU institution where member states’ preferences are most clearly articulated, the Council pushed for a more careful consideration of existing reforms at the domestic level. It put forward its own two solutions. One possibility would be to force banks to ‘separate trading activities in an entity legally, economically, and operationally separate from the credit institution that carries out core retail banking activities’ (CitationCouncil, 2015: 6). This is in line with the measures already adopted in Germany and France. Another option would be to ‘ring-fence core retail banking activities in accordance with national law’ (CitationCouncil, 2015: 6). This corresponds to the reforms already in place in the UK. At the same time, the Council's position also stresses that the Commission should be empowered to monitor and assess the application of banking structural reforms in the member states in order to prevent regulatory arbitrage and fragmentation of the internal market in financial services. The Dutch Council Presidency, January-June 2016, stated in its work programme that trilogue negotiations between the Council, Parliament, and Commission would begin as soon as the European Parliament has determined its position, but that has not happened at the time of writing (CitationThe Netherlands, 2016: 15).

5 Conclusion

The main finding of this article is that partial solutions to the problem of banks which are ‘too big to fail’ in different areas of EU banking regulation, coupled with the strategic activism of key member states such as the UK, France, and Germany, have limited the opportunities to design a coherent harmonised EU framework regulating bank structures.

I developed the concept of ‘regulatory cascading’ in order to analyse the rapid successive introduction of legislative packages, designed to improve the regulation of banks that are ‘too big to fail’. In the EU, different expert groups designed policy reforms to address distinct aspects of this policy problem. As shown in , important amended and new pieces of EU legislation, such as CRD IV, CRR, and BRRD all provided partial solutions to the problem. However, the analysis of regulatory cascading in EU banking structural reforms has revealed that neither policy-makers nor stakeholders have been able to anticipate the interactions between different strands of reform introduced in close temporal proximity to tackle this complex multi-faceted policy problem.

The article discussed banking structural reforms introduced in the EU, taking into account similar reforms developed at the international level and domestic level of the member states. While EU policy-makers are still negotiating harmonised EU legislation, member states such as the UK, France, and Germany have already put in place their own domestic measures. In response to the Commission's proposal for European banking structural reforms, the Council stressed in its position two approaches that closely correspond to the measures adopted in France and Germany, on the one hand, and the UK, on the other hand. This finding confirms that political discretion and inter-institutional bargaining are still important features of EU policy-making, even after the launch of the EU's new ‘Better Regulation’ agenda, which aims to streamline and rationalise policy-making in the Union.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank two anonymous Policy and Society reviewers and the organisers of and participants in several research workshops for their valuable feedback on previous versions of this article: the workshop on ‘Institutional and Policy Design in Financial Sector Reform’ held in Istanbul in September 2015, in particular the discussant Travis Selmier; ‘The Better Regulation Agenda: Achievements and Challenges Ahead’ held in Brussels in December 2015, in particular the discussant Sebastiaan Princen; ‘European Union Decision-Making and Challenges to Economic and Financial Governance’ held at the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study in the Humanities and Social Sciences (NIAS) in December 2015, in particular the discussant Jakob de Haan.

References

- A. Alemanno . How much better is better regulation? Assessing the impact of the better regulation package on the European Union — A research agenda. European Journal of Risk Regulation. 6(3 Institutional and Policy Design for the Financial Sector): 2015; 344–356.

- A. Baker . Restraining regulatory capture? Anglo- America, crisis politics and trajectories of change in global financial governance. International Affairs. 86(3 Institutional and Policy Design for the Financial Sector): 2010; 647–663.

- Bakir, C., & Woo, J. J. (2016). This volume..

- Bank of England — Prudential Regulation Authority . The implementation of ring-fencing, consultation on legal structure, governance and the continuity of services and facilities — CP19/14. 2014. Available from: http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/pra/Pages/publications/cp/2014/cp1914.aspx .

- J. Barth , G. Caprio , R. Levine . Rethinking bank regulation. Till angels govern. 2006; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge

- G. Capano , J. Rayner , A. Zito . Governance from the bottom up: Complexity and divergence in comparative perspective. Public Administration. 90(1): 2012; 56–73.

- G. Capano , M. Howlett , M. Ramesh . Re-thinking governance in public policy: Dynamics, strategy and capacities. G. Capano , M. Howlett , M. Ramesh . Varieties of governance. Dynamics, strategies, capacities. 2015; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke

- D. Coen , M. Thatcher . Network governance and multi-level delegation: European networks of regulatory agencies. Journal of Public Policy. 28(1): 2008; 49–71.

- Council of the European Union (Council) . Council position on proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on structural measures improving the resilience of EU credit institutions. 2015; Council of the European Union: Brussels 2014/0020 (COD).

- F. De Francesco , C.M. Radaelli , V.E. Troeger . Implementing regulatory innovations in Europe: The case of impact assessment. Journal of European Public Policy. 19(4): 2012; 491–511.

- R. Dehousse . Regulation by networks in the European community: The role of the European agencies. Journal of European Public Policy. 4(2): 1997; 246–261.

- Deloitte . Structural reform of EU banking. Rearranging the pieces. 2015; EMEA Center for Regulatory Strategy: London Available from: http://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/financial-services/deloitte-uk-fs-structural-reform-eu-banking-april-14.pdf .

- C. Dunlop , M. Maggetti , C. Radaelli , D. Russel . The many uses of regulatory impact assessment: A meta-analysis of EU and UK cases. Regulation & Governance. 6(1): 2012; 23–45.

- B. Eberlein , E. Grande . Beyond delegation: Transnational regulatory regimes and the EU regulatory state. Journal of European Public Policy. 12(1): 2005; 89–112.

- B. Eberlein , A.L. Newman . Escaping the international governance dilemma? Incorporated transgovernmental networks in the European Union. Governance. 21(1): 2008; 25–52.

- R.A. Epstein , M. Rhodes . The political dynamics behind Europe's new banking union. West European Politics. 39(30): 2016; 415–437.

- European Commission . Proposal on banking structural reform. 2014. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/finance/bank/structural-reform/index_en.htm .

- European Commission . Impact assessment accompanying the document proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on structural measures improving the resilience of EU credit institutions. 2014; European Commission: Brussels SWD(2014) 30 final. Available from: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52014SC0030 .

- European Commission . Communication. Better regulation for better results — An EU agenda. 2015. SWD(2015) 110 and 111 final. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/smart-regulation/better_regulation/documents/com_2015_215_en.pdf .

- European Parliament . Draft report on the proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on structural measures improving the resilience of EU credit institutions, prepared by Gunnar Hökmark. 2015. Available from: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?type=COMPARL&mode=XML&language=EN&reference=PE546.551 .

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) . Selected sections of the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. 2014. Available from: https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/reform/dfa_selections.html .

- E. Ferran . Crisis-driven regulatory reform: Where in the world is the EU going?. E. Ferran , N. Moloney , J.G. Hill , J.C. Coffee . The regulatory aftermath of the global financial crisis. 2012; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge

- E. Ferran , N. Moloney , J.G. Hill , J.C. Coffee . The regulatory aftermath of the global financial crisis. 2012; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge

- Financial Stability Board (FSB) . Structural Banking Reforms. Cross-border consistencies and global financial stability implications. 2014. Report to G20 Leaders for the November 2014 Summit. Available from: http://www.fsb.org/2014/10/r_141027/ .

- P. Genschel , B. Zangl . State transformations in OECD countries. Annual Review of Political Science. 17 2014; 337–354.

- R. Germain . Governing global finance and banking. Review of International Political Economy. 19(4): 2012; 530–535.

- E. Grossman , C. Woll . Saving the Banks: The political economy of bailouts. Comparative Political Studies. 47(4): 2014; 574–600.

- H. Hakenes , I. Schnabel . Separating trading and banking: Consequences for financial stability. 2014; German Institute for Economic Research Paper. 2 October.

- I. Hardie , D. Howarth . Market-based banking and the international financial crisis. 2013; Oxford University Press: Oxford

- I. Hardie , H. Macartney . EU ring-fencing and the defence of too-big-to-fail banks. West European Politics. 39(3 Institutional and Policy Design for the Financial Sector): 2016; 503–525.

- A. Héritier , D. Lehmkuhl . Introduction: The shadow of hierarchy and new modes of governance. Journal of Public Policy. 28(1): 2008; 1–17.

- D. Howarth , L. Quaglia . The political economy of banking union. 2016; Oxford University Press: Oxford

- Howarth, D. & Quaglia, L. (2016b). This volume..

- M. Howlett , J. Rayner . Design principles for policy mixes: Cohesion and coherence in ‘new governance arrangements’. Policy and Society. 26(4): 2007; 1–18.

- M. Howlett . Designing public policies: principles and instruments. 2011; Routledge: London

- M. Howlett , R. Lejano . Tales from the crypt: The rise and fall (and rebirth?) of policy design. Administration & Society. 45(3 Institutional and Policy Design for the Financial Sector): 2013; 357–381.

- T.F. Huertas . Six structures in search of stability. LSE Financial Markets Group Paper Series Special Paper No. 236. 2015. July 2015.

- S. James . The UK in the multilevel process of financial market regulation: Global pace-setter or national outlier?. R. Mayntz . Negotiated reform: The multilevel governance of financial regulation. 2015; Campus Verlag: Frankfurt 121–137.

- Z. Kudrna . Governing the ins and outs of the EU's banking union. Journal of Banking Regulation. 17(1): 2016; 119–132.

- R.M. Lastra . The governance structure for financial regulation and supervision in Europe. Columbia Journal of European Law. 10 2003; 49–68.

- E. Liikanen . Report of the high-level expert group on reforming the structure of the EU banking sector. 2012. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/finance/bank/docs/high-level_expert_group/report_en.pdf .

- D. Masciandaro , S. Eijffinger . The Handbook of Central Banking, Financial Regulation and Supervision after the Crisis. 2011; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham

- W. Mattli , T. Büthe . Accountability in accounting? The politics of private rule-making in the public interest. Governance. 18(3 Institutional and Policy Design for the Financial Sector): 2005; 399–429.

- Méró, K. & Piroska, D. (2016). This volume..

- A. Meuwese , M. Scheltema , L. van der Velden . The OECD framework for regulatory policy evaluation: an initial assessment. European Journal of Risk Regulation. 6(1): 2015; 101–110.

- N. Moloney . EU financial market regulation after the global financial crisis: ‘More Europe’ or more risks?. Common Market Law Review. 47(5): 2011; 1317–1383.

- D. Mügge . Europe's regulatory role in post-crisis global finance. Journal of European Public Policy. 21(3 Institutional and Policy Design for the Financial Sector): 2014; 316–326.

- V. Ostrom , C. Tiebout , R. Warren . The organization of government in metropolitan areas: A theoretical inquiry. American Political Science Review. 55(4): 1961; 831–842.

- E. Ostrom . Beyond markets and states: Polycentric governance and complex economic systems. American Economic Review. 100(3 Institutional and Policy Design for the Financial Sector): 2010; 1–33.

- S. Pagliari , K. Young . Leveraged interests: Financial industry power and the role of private sector coalitions. Review of International Political Economy. 21(3 Institutional and Policy Design for the Financial Sector): 2014; 575–610.

- T. Porter . Regulatory capture in finance: Lessons from the automobile industry. S. Pagliari . Making good financial regulation. Towards a policy response to regulatory capture. 2012; International Centre for Financial Regulation: London

- L. Quaglia . Setting the pace? Private financial interests and European financial market integration. British Journal of Politics and International Relations. 10(1): 2008; 46–64.

- L. Quaglia . Governing financial services in the European Union: Banking, securities and post-trading. 2010; Routledge: London

- L. Quaglia . The sources of European Union influence in international financial regulatory fora. Journal of European Public Policy. 21(3 Institutional and Policy Design for the Financial Sector): 2014; 327–345.

- L. Quaglia . The European Union and global financial regulation. 2014; Oxford University Press: Oxford

- C.M. Radaelli . Whither better regulation for the Lisbon agenda?. Journal of European Public Policy. 14(2): 2007; 190–207.

- G. Rosas . Curbing Bailouts: Bank Crises and Democratic Accountability in Comparative Perspective. 2009; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, Michigan

- V.A. Schmidt . Speaking to the markets or to the People? A discursive institutionalist analysis of the EUs sovereign debt crisis. British Journal of Politics and International Relations. 16 2014; 188–209.

- L. Seabrooke . What do i get? The everyday politics of expectations and the subprime crisis. New Political Economy. 15(1): 2010; 51–70.

- D.A. Singer . Regulating capital: Setting standards for the international financial system. 2007; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, N.Y

- S. Smismans . Policy evaluation in the EU: The challenges of linking ex ante and ex post appraisal. European Journal of Risk Regulation. 6(1): 2015; 6–26.

- A. Spendzharova . For the market, or ‘for our friends’? the politics of banking sector legal reform in the post-communist region after 1989. Comparative European Politics. 6(4): 2008; 432–462.

- A. Spendzharova . Banking union under construction: The impact of foreign ownership and domestic bank internationalization on European Union member states’ regulatory preferences in banking supervision. Review of International Political Economy. 21(4): 2014; 949–979.

- A. Spendzharova , E. Bayram . Banking union through the back door? The impact of European Banking union on Sweden and the Baltic states. West European Politics. 39(3 Institutional and Policy Design for the Financial Sector): 2016; 565–584.

- A. Spendzharova , E. Versluis , L. Flöthe , E. Radulova . Too much, too fast? The sources of banks opposition to European banking structural reforms. Journal of Banking Regulation. 17(1–2): 2016; 133–145.

- The Netherlands . Programme of the Netherlands Presidency of the Council of the European Union. 2016. 1 January–30 June 2016, Available from: http://english.eu2016.nl/ .

- K. Thelen , J. Mahoney . Advances in comparative historical analysis. 2015; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge

- J. Vickers . The independent commission on banking: The Vickers report. 2011. Available from: http://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/SN06171 .

- C. Woll . The power of inaction: Bank bailouts in comparison. 2014; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY

- Woo, J. J., Ramesh, M., Howlett, M., & Coban, K. (2016). This volume..

- E. Wymeersch . The European financial supervisory authorities or ESAs. E. Wymeersch , K.J. Hopt , G. Ferrarini . Financial regulation and supervision: A post-crisis analysis. 2012; Oxford University Press: Oxford 232–317.

- K. Young . Transnational regulatory capture? An empirical examination of the transnational lobbying of the Basel committee on banking supervision. Review of International Political Economy. 19(4): 2012; 663–688.

- K. Young . Losing abroad but winning at home: European financial industry groups in global financial governance since the crisis. Journal of European Public Policy. 21(3 Institutional and Policy Design for the Financial Sector): 2014; 367–388.