Abstract

The purpose of this study is to understand Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland's opt out position from the Banking Union (BU). The Banking Union is compulsory for Eurozone member states and optional for non-Eurozone member states. From the Central and Eastern European (CEE) region only Romania and Bulgaria decided to join. First, we attempt to explain this fact based on structural characteristics of the CEE banking sectors, but we find no substantial difference between the opt-in and opt-out countries’ banking sectors. Second, we look at the role of state capacity in maintaining a stable banking sector, and find that state capacity is a necessary condition for opting out. Finally, using Hungary as a case study, and the Czech Republic and Poland as further examples, we argue that these countries opted out because their governments’ policy preference of banking nationalism conflicts with the BU's ideals.

1 Introduction

Banking Union (BU) is possibly the greatest single step towards tighter financial integration taken by the European Union (EU) member states since the introduction of the Euro. Based on a single rule book for all 28 member states, it establishes a single supervisory mechanism (SSM) located at the European Central Bank (ECB) and it has the promise of creating a level playing field for all major banks in Europe. The Banking Union project also encompasses a single resolution mechanism (SRM) that has the potential to disentangle the interdependence among banks and member states. Once the BU is fully functional — including the now postponed single deposit insurance system — it is hoped that there will be a more stable and secure banking system in Europe.

There is an ongoing debate on the magnitude of change brought about by Banking Union. Some contend that the creation of a common supervisory mechanism amounts to a huge loss of national control over banks (CitationEpstein & Rhodes, 2014; Howarth & Quaglia, 2014), others however, question the magnitude of change. They argue that major change was compromised and national regulators are still in control (CitationDonnelly, 2014; McPhilemy, 2014). We agree with CitationDe Rynck (2016) who argues that “centralising supervision and harmonising standards are a rupture with the past and introduce a new policy model” (p. 120). However, the change will not affect all member states equally. Joining the Banking Union is only compulsory for Eurozone member states. Non-Eurozone EU members may decide to join the project or not. UK and Sweden opted out saying that the BU gives limited rights to non-Eurozone states. However, Denmark also outside the Eurozone has indicated an interest in joining the club. A few Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries with banking sectors largely dominated by Western European mother banks have taken a cautious wait-and-see approach, while others decided to join in. In this paper, we are interested in why three CEE states decided to stay outside from this potentially beneficial arrangement?

CEE non-Eurozone countries’ mixed position on the BU is puzzling for at least two reasons. First, their banking sectors share several similar structural characteristics, yet their positions vis-à-vis the BU differ sharply. While Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Croatia have taken a wait-and-see approach in 2014, Bulgaria and Romania declared intentions to join. Second, because these countries’ banking sectors are extremely open to foreign investors, two influential Bruegel studies one in 2013 (CitationDarvas & Wolff, 2013) and one in 2016 (CitationHüttle & Schoenmaker, 2016) argued that joining the BU would be beneficial for them because it could improve the credibility of national prudential arrangements. Yet, three CEE countries prefer local control over their banking sectors to ECB provided stability.

CEE policy makers’ own account for the dissent was presented and analysed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 2015. CEE decision makers were found to be more concerned about potential downsides of early opt-in to the BU than benefits of potential upsides. Among the downsides they emphasised those features of the BU which weakens the supervisory power of the state. They extensively criticised the current set up of the SSM for being overly complicated, for not granting the same fiscal safety guard to non-Eurozone member states and for being too expensive for what it provides (CitationIMF, 2015, p. 38). In other words, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Poland and Croatia communicated that their reason for opting out is that they believe they can provide for the same level of stability of their banking sector as the ECB, but cheaper.

We argue that these countries opt out mainly because governments in these countries want to stay in control of their own banking sectors. We show how banking nationalism dominates policy making in CEE and that this policy choice explains their preference for keeping a distance from BU. We argue that Bulgaria and Romania opt-in because they want to compensate for the low level of state capacity to maintain financial stability by delegating banking supervision to a supranational entity. In this study, we only consider opt-out positions taken by Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland and exclude Croatia. Even though Croatia took a similar wait-and-see approach, because it only joined the EU in 2013, we cannot exclude that it made the same decision for different reasons.

In the course of the research we conducted semi-structured interviews with officials from the Hungarian central bank, experts from Hungary and Poland and bankers from Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic in 2015. We consulted policy briefs, policy documents, memos, and other primary sources. Our methodology is process tracing with a special focus on policy goals, policy instruments and orders of policy change, the components of policy design as defined by CitationBakir and Woo (2016) in the introduction of this issue. The paper is organised as follows. First, we overview alternative explanations to the dissent of CEE countries. Most of these explanations take distinct structural characteristics of banking sectors and derive the opting in and opting out choices from these characteristics. We show that these attempts not only fail to logically link different structural attributes to the chosen policy lines, but that there are no underlying structural similarities in the opt-in countries that would set them apart. As potential alternative explanation we analyse state capacity to maintain banking sector's stability. It is followed by an outline of banking nationalism, a policy choice that legitimates controversial policies that could not be pursued inside the Banking Union. Next, we present a case study of Hungary. Finally, we detail examples of banking nationalism from Poland and the Czech Republic. The last part concludes.

2 A failed attempt: structuralist frameworks

Explaining positions taken by various countries towards international rule harmonisation based on differences in their domestic structural characteristics has a long established tradition within IPE (CitationFrieden, 1991; Frieden & Rogowski, 1996; Frieden, 2002; Garett 1992). CitationSpendzharova (2014) based her analysis on this literature. She argued that EU countries where foreign ownership in the banking sector is high and domestic banks’ internationalisation is low would prefer to preserve some national regulatory autonomy. In her analysis, all CEE countries have fallen into this category.

There are several problems with this argument, however. First, as of 2016 we know that Romania and Bulgaria opted in the BU, while Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary registered a wait-and-see approach. In the two selected structural categories, Romania and Bulgaria are in the same category as Poland and the Czech Republic so they should have the same preferences, but they do not. Second, selecting only two structural categories may not be enough to clearly see how banking sector structures influence governments’ policy formation. Finally, as in the case of other structure-based analysis, it is unclear that given the particular structural conditions why regulators chose the predicted behaviour. A preference for the autonomy in financial regulatory matters is assumed rather than accounted for causally.

CitationHowarth and Quaglia (2014) set out the task of explaining EU member states’ position towards the BU using a much larger set of structural variables. They looked at the degree of banking system concentration; the degree of internationalisation/Europeanisation; the degree of foreign bank penetration; and the funding structure of different banking systems. The major claim of their paper is that banking sector structures strongly influence member states’ positions vis-à-vis the BU. However, when turning to explain the opt-out positions of CEE countries they write: “Central and Eastern European countries with banking systems dominated by foreign (mostly Euro area) banks had an incentive to join BU because they were not in a position to safeguard financial stability domestically. However, they came out against participation.” (p. 12) Therefore, they conclude “these stand as counter-examples to the importance of banking system structure to policy preference” (p. 12.) Unfortunately, they stop their explanation with regards to CEE positions right there.

CitationEpstein and Rhodes (2014), in a partly structure-based, partly institutionalist analysis, also examine the reasons why European countries decided to move financial supervision to supranational level. First, they point out that global liberalisation made banking sector protectionism more costly and conflictual for states. In particular, they argue that because of increased integration of capital (including bond) markets the danger in the process that banks provided credit to “their sovereigns” became more costly and risky. As government bond yields increased not only did states face higher borrowing costs, but also their banks got into trouble, too. Therefore, they claim, one of the major reasons why states in Europe became inclined to give up banking sector protectionism was the increased financial vulnerability of both banks and states. Second, they argue that the introduction of common currency, together with fragmented banking systems, created structural conditions in which recession-affected banking systems faced limited adjustment tools. Moreover, the same structural contradiction led to another problem in the Eurozone, namely the ineffective transmission mechanism of the monetary policy by ECB. Third, CitationEpstein and Rhodes (2014) point out a change in the interest of international banks away from that of their home authorities. Internationally active banks became increasingly wary of the conflicts they faced with home and host regulators and demanded a common framework of supervision. Finally, they point out the importance of ECB and the Commission in actively persuading member states (most importantly the reluctant Germany) to follow suit and opt into the BU initiative.

While CitationEpstein and Rhodes (2014) only endeavoured to explain the opt-in position, we may try to relate these structural and institutional factors and examine how they affect CEE5 choices. During the financial and sovereign debt crisis, in CEE the sort of sovereign-and-banks intimacy which affected some Eurozone countries have never developed, due to the very high internationalisation of their banking sectors. CEE5 countries have not introduced the Euro yet, so those structural changes in banking that make the preservation of fragmented banking systems in Europe costly under one single currency do not affect them. These two structural factors thus do not push them towards an opt-in position, yet two out of the CEE5 non-Euro area countries decided to join in. Moreover, the change in the interest in the internationally active banks if applied to the CEE cases would certainly push all of them towards opting-in, since their banking sectors are dominated by large, international banks. Yet, three CEE countries chose the opt-out position.

In sum, according to the two Bruegel studies, CitationHowarth and Quaglia (2014) and CitationEpstein and Rhodes (2014) structural conditions urges all CEE governments to opt in, therefore the opt-out positions must be explained. On the other hand, CitationSpendzharova (2014) expected all CEE to opt out. In her case, the opt-in decisions of Romania and Bulgaria represent a puzzle that must be explained. It seems that the above discussed structural factors do not help in understanding CEE5 different positions. However, other factors might. This is why we surveyed a number of additional structural factors. Our main question in the following is thus: Does the structure of a CEE country's banking sector explain its opt-in or opt-out choice?

3 Survey of CEE5 banking sectors’ structural characteristics

In 2013 CEE5 have much shallower banking systems than their West European peers. The largest deviation from West European trends is shown in the case of Romania. Poland has the second lowest level of banking intermediation, while the total assets to GDP value is very similar in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic and Hungary. All five countries’ banking systems are dominantly foreign owned, mostly by EU banks. The largest market participants are subsidiaries; however, some branches are also operating on CEE5 markets. The market share of subsidiaries and branches of non-EU banks is negligible. The proportion of foreign banks’ total assets to total assets of banking sector is 25 percent in EU 27. It ranges in CEE5 between 60 (Hungary) and 92 (the Czech Republic) percent. In addition, the five countries’ banking systems are similarly concentrated. The share of the three largest banks’ total assets is between 24 and 51 percent which is in the lower half of EU national banking markets. The Herfindahl indices also show that the CEE5 banking markets are not too concentrated (CitationECB, 2014). In addition, all five countries have competitive banking markets, measured by Lerner index. The value of the index varies in a narrow range and it is very close to the Eurozone average (Global Financial Development Database, CitationGFDD, 2016).

Since CEE5 banks are relatively small only the three largest banks per country would be directly supervised by the SSM in case of opt-in. The owners of the top three CEE5 banks are predominantly banks from the Eurozone (10 cases out of 15). There is only one large state owned bank (the Polish PKO BP). Out of the two domestically controlled banks, Bulgarian First Investment Bank (the third largest) is 85 percent owned by two Bulgarian private persons and the remaining part is public; the Hungarian national champion, OTP is a public company with dispersed holding, but controlled by the Hungarian management. OTP is also the owner of the second largest Bulgarian Bank, DSK.

CEE5 banks focus on domestic banking. Only the Hungarian OTP has significant foreign activity. It has subsidiaries in the Eurozone (Slovakia), in the EU outside the Eurozone (Bulgaria, Romania, and Croatia) and outside the EU (Montenegro, Serbia, Ukraine, and Russia). The total foreign assets of OTP are equal to about 40 percent of its domestic assets. The Bulgarian Fibank has limited foreign activity: it has a subsidiary in Albania and a branch in Cyprus. Apart from these, only the Polish PKO BP and the Romanian Banca Transilvania have some, but very limited foreign activity.

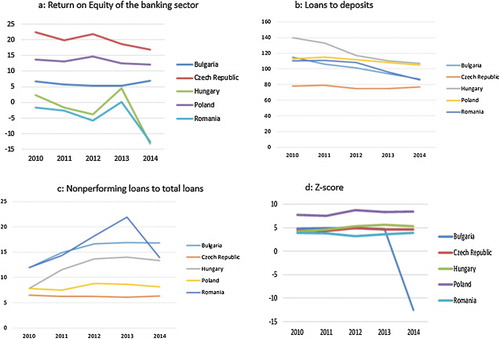

CEE5 banks’ profitability has a high standard deviation. On average the Hungarian and the Romanian banking sectors were predominantly loss-making between 2010 and 2014, while the other three countries’ were profitable. The Czech banking sector's profitability remained outstandingly high after the crisis, Polish banks also realised high returns and the Bulgarian banking sector had positive but modest RoEs (/a ). On aggregate level, only the Czech banking system is financed from domestic deposits. By 2013 Bulgarian and Romanian banking systems also became domestically financed. In the meantime, Polish and Hungarian banking systems are still exposed to foreign funds although to a steadily decreasing extent (/b). As regards the portfolio quality of the CEE5 banks, the Czech and the Polish banking sectors have a significantly lower, the Romanian and the Bulgarian have a higher proportion of nonperforming loans. Hungary is in between. In 2010 the Hungarian nonperforming loan ratio was on the Polish level, but later on, the portfolio quality came closer to the Bulgarian and Romanian levels (/c). Since the portfolio quality relates to banking system's stability and this is the first indicator that showed marked difference between the opt-in and opt-out countries, another banking stability indicator, the Z-score (CitationČihák, Demirgüç-Kunt, Feyen, & Levine, 2012) were analysed. Its main advantage is, that it is forward looking, since it explicitly compares the risk (measured by volatility of the RoA) with the capital and return, i.e. to available risk absorbing buffers. The Eurozone's Z-score average was between 8.8 and 10.1 in the period of 2010–2014. Within the CEE5 it was the highest in Poland, still a bit below the Eurozone's values. Romania had the lowest values, but only slightly below the Z-score for the Czech Republic, Hungary and Bulgaria for the period of 2010–2013. In 2014 the Bulgarian Z-score had fallen to −12.6 (i.e. indicates an insolvent banking system) as a result of unforeseen failure of two large banks (/d). The sudden fall of the Bulgarian Z-score indicates that the collapse of two Bulgarian banks in 2014 was not (or not only) due to accumulated high risk relative to buffers, but to other reasons (for example, misreporting, falsification of accounting, corruption, etc.).

Source: CitationRaiffeisen Research (2014), CitationGFDD (2016).

As it is shown above, despite the common roots and essential similarities CEE5's banking systems are relatively diverse. gives an overview of the most important similarities and differences. It determines the dividing line among the CEE5 countries in relation to all relevant structural attributes. Based on this overview we can clearly conclude that, except for the level of non-performing loans, there is no structural dividing line between the two opt-in countries’ banking sectors and the three opt-out countries’ ones.

Table 1 Structural dividing lines of CEE5 banking system.

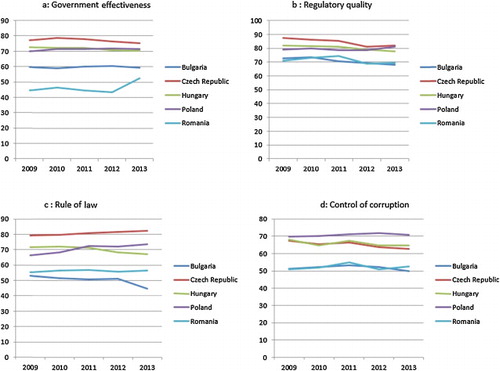

4 A potential alternative explanation: state capacity and its political repercussions

Looking for alternative explanations we investigate the role of a domestic political factor: state capacity. State capacity is defined here following CitationWu, Ramesh, and Howlett (2015) as “the set of skills and resources -or competences and capabilities- necessary to perform policy functions” (p. 166). We measure the level of state capacity using CitationWorldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) and focus on the post-crisis period (2009–2013). It seems clear that the values for CEE5 are generally lower than that of the most developed countries’ values. Moreover, there is a strong dividing line between Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland, on the one hand, and Romania and Bulgaria, on the other, with regards to governments’ autonomy. Looking at government effectiveness; regulatory quality; rule of law and control of corruption Romania and Bulgaria show significantly lower values compared to Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland ( ). The greatest divide can be seen in the effectiveness of controlling corruption. While Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland cluster between 62 and 71 percentile, Romania and Bulgaria can be found between 55 and 49 percentile. With regards to government effectiveness Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland are between 70 and 80 percent for most of the period, Romania and Bulgaria score no higher than 60 percent. If we look at more qualitative indicators the dividing line still prevails. In the case of rule of law we see that Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland vary between 67 and 82 percent, while Romania and Bulgaria stays between 45 and 55 percent. With regards to regulatory quality we see them closest; nevertheless the two clusters of countries take on significantly different values.

Source: WGI database (2015)

Based on these findings, we argue that the low level of state capacity in the cases of Bulgaria and Romania motivated these governments to delegate banking supervision to EU level. CitationWoo (2016) argued that financial policy comprises three types of policy instruments such as stabilising, enabling and developmental instruments (p. 15). We argue that in the cases of Bulgaria and Romania low level of state capacity especially in the area of providing financial stability came to a critical level. Governments in these countries decided that delegating the stabilising policy instruments to supranational level has the promise of a superior outcome than keeping bank supervision at national hands.

Lower values of state capacity were reflected in Bulgarian and Romanian politics as well. In Bulgaria, the initial political position on Banking Union in 2012 was unfavourable. The negative attitude prevailed throughout the political crisis that followed the 2012 elections. General elections took place in 2013 and in 2014. During all these political turmoil, banking and politics remained closely connected. In June 2014, however, two Bulgarian banks experienced bank runs that profoundly shook banking sector stability and the political scene. A month later, on July 14 Bulgarian president, Rosen Plevneliev announced Bulgaria's intention to join the Banking Union.

Romania's political decision to join BU was based on a realisation of low state capacity that was accentuated by two political factors: a political distress that surrounded the increase in non-performing loans and the strong political support of European integration. Romania's experience with the CitationVienna Initiative (VI) was less favourable than that of other participating countries. Although VI provided guarantee of funding from mother bank was kept during the most difficult years of the crisis (CitationHass De, Korniyenko, Loukoianova, & Pivovarsky, 2012), in 2011 and 2012 the lack of credit growth was partly a result of withdrawal of funding by mother banks (VI 2012). In addition, leading politicians’ Europhilia presented Banking Union as a viable solution to financial stability issues. In particular, Romanian president and the central bank's governor were in favour of tighter EU integration. This enthusiasm explains also the fact why Romania is the only country in the region with a set target date of Euro adoption in 2019. While the analysis above clearly shows how weak state capacity conditioned Romania and Bulgaria to join the Banking Union, in the cases of the opt-out countries the higher levels of state capacity provide the condition for opting-out, but do not explain it.

5 Reason for opt-out: banking nationalism

In order to explain the opt-out positions of Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland we propose to look at the effect of banking nationalism on the formation of financial policy goals, choice of policy instruments and orders of policy change. In the case of Hungary, financial nationalism was recently exposed by CitationJohnson and Barnes (2015) as the dominant ideological framework within which financial policies are designed. The authors indicated that while financial nationalism, just like economic nationalism may be constructed in a number of ways i.e. in different countries the term may describe different policy choices, in general, however, financial nationalism usually manifests itself in five interrelated policy choices. These policy choices are autonomous monetary policy, dirty floating currency regime, undermined independence of the central bank, banking nationalism and animosity towards foreign international institutions. CitationJohnson and Barnes (2015) convincingly argue that in Hungary Orban's government follows financial nationalism, but they did not look at the CEE region at large. We argue that a sub-set of financial nationalism, namely banking nationalism is clearly present in the Czech Republic and Poland, as well.

Banking nationalism is a government policy which promotes national interest in all areas of banking policy: bank ownership, bank regulation and bank supervision. We argue that to detect banking nationalism in CEE it is necessary to enlarge the concept and to look at all of the above mentioned functions. In the majority of CEE countries banks are dominantly foreign owned. If we narrowed down banking nationalism to ownership of banks (as CitationJohnson and Barnes (2015) or CitationEpstein (2014) did) we might miss detecting it in CEE. Using this enlarged concept it becomes possible to see that banking nationalism in CEE not only serves the purpose of bringing national banks to a better off position to foreign banks, but more importantly to legitimate controversial government actions (see CitationSmith (1995) on why the notion of legitimacy is essential to the study of nationalism). Government actions advanced in the name of national interest in the banking sector might be controversial for a number of reasons. They for instance may not primarily promote stability of banking, but rather are helpful in inserting ruling party-related individuals into important decision making positions. They may create regulatory environment more beneficial for local banks. Or, they may serve the purpose of channelling public and private funds into cronies’ pockets. In other words, banking nationalism as a policy — through a claim to national interest — increases governments’ room for manoeuvring within the banking sector. Although national interest as a concept could be filled with other content in Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland, it increasingly justifies a banking policy that is hostile to foreign banks and international organisations. We argue that banking nationalism as advanced by CEE governments clashes with the BU's ideals. This is why these governments opted out.

Banking nationalism manifests itself differently in the three above mentioned state functions in CEE. Within the EU the scope for banking nationalism in the field of bank regulation has been significantly reduced since the introduction of the single rule book, one of the pillars of BU. Nevertheless, the European regulatory framework delegates some important regulatory power to competent supervisory authorities, which is the ECB for BU members and the national supervisory authorities for non-BU members. Both trends encourage CEE governments to retain their existing regulatory power and stay outside the BU.

Bank ownership by states or national owners has been more important in Western Europe than in CEE since the mid-1990s (CitationEpstein, 2014; Kudrna & Gabor, 2013). Banking nationalism in the form of bank ownership has been exposed as one of the main causes of the 2010 Euro crisis in Western Europe (CitationEpstein & Rhodes, 2014). The BU was created precisely to loosen the ties between national banks and government. In CEE, however, where national bank ownership was lower, since Global Financial Crisis (GFC), there seems to be an urge to increase national ownership. In other words, CEE governments would increase national ownership of banks at a time when BU would loosen ties between national banks and governments.

Finally, it is in the field of bank supervision that BU clashes most with CEE3 governments’ banking nationalism. Bank supervision both at the micro (individual bank) and macro (banking sector) level gives the opportunity for politicians to exercise control over banks. Retaining bank supervisory powers frees CEE policy makers to harmonize their decisions with the ECB. Transferring the right of authorisation is an especially dear power that CEE politicians would not want to give up. The freedom of authorisation can be very important in reshaping the ownership structure of the banks. Moreover, giving up further scope of supervisory autonomy is against the banking nationalist ideals of the CEE governments in power.

summarises our argument: banking nationalism as pursued by CEE governments clashes with the BU's ideals.

Table 2 CEE banking nationalism and the BU.

6 The Hungarian case study

In the following, we analyse those elements of the Hungarian government's banking policy that provide particulars on the existence of banking nationalism. We look at events that occurred between 2012 and 2015 around the time when the decision on the BU was made.

6.1 Bank ownership

The Orban government declared its aims to radically change bank ownership structure in 2012. With a supermajority in the Parliament and the central bank under an ally's control Orban's government was in the position to fully achieve its policy goals since 2013. The related steps are well-documented in the Hungarian press and in CitationKirály (2015). Here we just highlight some of them. The Hungarian state nationalised the fourth largest bank (MKB). After purchasing it from Bayerische Landesbank in December 2014 MNB, as the Hungarian Resolution Authority, took MKB under resolution. The resolution was an opaque process however, several market rumours talked about the cherry picking of MKB's portfolio by businessmen close to the government. During the resolution process, a former Deputy Governor, Adam Balog, became the bank's CEO. Several members from MNB's staff–including former supervisors - became the bank's top or middle managers. Another upper medium size bank, Budapest Bank, the commercial bank of GE Capital is now also under nationalisation. These nationalisations are declared temporary. However, the lack of transparency in these steps questions the transparency of future privatisation.

In 2013 and 2014 the Hungarian government increased capital in several small Hungarian banks. One of them, Széchenyi Kereskedelmi Bank was 51 percent owned by István Töröcskei, CEO of State Debt Management Company (ÁKK). Mr Töröcskei resigned from ÁKK only after the collapse of his bank in December, 2014. According to a document owned by a Hungarian weekly (CitationMáriás, 2014) MNB was aware of the Bank's insolvency in January, but it failed to act as the competent supervisory authority until December.

FHB Kereskedelmi Bank needed a capital increase in late September 2014, since according to a law which entered into force on the 24th of September all banks were obliged to convert the still existing FX loans to HUF and compensate borrowers for the items which were declared unfair by the Hungarian High Court. The bank was loss-making during the previous years, and the loss accumulated due to the new state measures would have undermined its solvency. The FHB Group's main owner was a company owned by Zoltán Spéder, a businessman with strong connection to Fidesz. On the 30th of September 2014 the state owned Hungarian Post obtained 49 percent ownership in the bank. The case even raised the question of forbidden state aid. As the president and CEO of the OTP, Sándor Csányi announced at a conference (CitationCsányi, 2015), OTP turned to State Aid Monitoring Office to investigate the case. A whole chain of intricate changes in ownership rights characterised the case of Takarékbank, the central bank of Hungarian cooperative banking sector, as well. As a first step, it was nationalised with the help of two state owned companies, the Hungarian Post and the Hungarian Development Bank. As a result of several state measures, including establishing a huge state financed guarantee fund for the Hungarian cooperative banking sector, the right to dispose of the whole Hungarian cooperative banking sector and its guarantee fund together with the ownership right of Takarékbank went to the FHB Group. In this way, with using state money, the FHB Group got access to an outstandingly large volume of bank assets, without any state control (CitationKirály, 2015; Várhegyi, 2013).

All the transactions described above required authorisation from MNB. The central bank issued all the necessary licenses for these transactions. In the BU authorisation is the sole right of ECB. The above cases show that having the freedom to re-shape the ownership structure of the banking system also can be a strong motivation for opting out. Our interviewees confirmed that MNB's authorisations are generally “quick and dirty”, which means that all the necessary licenses are issued quickly without questioning the transactions. In all the above cases of authorisation only staying outside BU can ensure smooth authorisation of ownership changes.

6.2 Banking supervision

In relation to banking supervision the special treatment of the Hungarian national champion, OTP Bank is a case in point. OTP has more than 20 percent market share in Hungary and it has a significant East European subsidiary network. However, it is a small bank by European standards. In case of opt-in OTP would be supervised by the ECB and it would become a small individually supervised bank with less specific, tailor made supervisory attention. OTP is definitely a too-big-to-fail, systemically important bank in Hungary, which explains the special regulatory and supervisory interest. To be nationally regulated and supervised is beneficial for the bank, for the government and for MNB, as well. The very close connection of regulators, supervisors and the bank is testified by the fact that several former regulators and supervisors continue their career with OTP group after resigning from their position. These officials include the Finance Minister, the State Secretary of Ministry of Finance, the President of the HFSA, the deputy CEO of HFSA and several top and middle managers of HFSA.

An example of the advantages being domestically supervised for OTP is the case of Asset Quality Review (AQR). Before joining the BU all the EMU member states had to conduct an AQR in line with ECB's methodology. OTP voluntarily underwent a very similar AQR. The successful AQR was good not only for OTP, but for MNB, as well, since it also could communicate that the national champion is stable and appropriately supervised. However, despite strong similarities, one can identify several important differences between the AQRs of banks’ inside the BU and the AQR of OTP. In both cases, the competent national authorities were responsible for AQR, and the review itself was made by selected large audit companies. In case of BU member states, AQR was paid and quality checked by ECB. In case of OTP it must have been domestically paid (in principle by OTP or by MNB; but more probably by OTP) and quality checked by MNB. The lack of ECB's quality checking and the domestic finance of AQR, by definition, meant that the level of independence and objectiveness of the AQR were not identical. Since the interest of both OTP and MNB was a successful AQR, which did not cover hidden asset quality problems, ECB's quality check would have been a very important element of the procedure.

Another advantage of staying outside the BU is the possibility to conducting the Supervisory Review Process (SREP) and imposing fines domestically. In the SREP framework a dialogue takes place between the banks and the supervisors, which results in determining the Pillar II capital requirement of the given bank. In case of BU members, the decision on the SREP capital requirement is made by ECB, while in case of non-BU members by competent national supervisory authorities. The SREP capital requirement is a very sensitive question, because it can significantly increase the banks’ capital requirement. For banks with good connections to supervisory authorities the SREP can be relatively lighter. Moreover, the SREP process is a useful tool for supervisors to follow their preferences or even to punish banks not in line with the supervisory (and/or governmental) preferences. According to our interviewees and market information MNB is not averse to use the SREP as a tool for the enforcement its own (and the government's) preferences.

6.3 Bank regulation

As regards bank regulation, several special bank regulatory tools were introduced since 2010. They are partly macroprudential tools (CitationMéró & Piroska, 2015), partly tools that handle households’ losses that became indebted in FX before the crisis and partly tools that aim to increase fiscal revenues and take the form of different taxes (CitationVárhegyi, 2012). The latter would not clash with the BU. However, MNB's macroprudential tools would become weaker within the BU. According to MNB's fears (CitationKisgergely & Szombati, 2014, p. 17) one “cannot be sure that the problems of smaller, non-euro area Member States will be taken as seriously as those of key Banking Union members with a more significant banking sector.” In addition, MNB's management is also wary of the possibility of losing its ability to set extra requirements for systemically important subsidiaries of banking groups. Being able to retain the right to set independent domestic macroprudential rules - that are also thought to be superior to ECB's regulation - is a key element of MNB's opt-out position.

Moreover, we can identify other regulatory steps that are in line with the Hungarian government's banking nationalism and should result in clash within the BU. A prominent example is the case of those cooperative banks that with good government connection could avoid nationalisation. Out of more than 100 Hungarian cooperative banks there were only five that could avoid the obligatory integration and nationalisation of the cooperative banking sector, due to a special regulation. The Act on the integration of cooperative banking sector contained a special paragraph that allowed exemption for those two cooperative banks that applied for authorisation of transforming their corporate form from cooperative to joint stock banks. However, the President of Hungary did not sign the law, but sent it back to the Parliament for deliberation. During the period of deliberation three additional cooperative banks applied for authorisation of their transformation to joint stock banks. All three cooperative banks belonged to the Buda Cash group, a group with very good government connections. The three cooperative banks got authorisation for transformation, so they could continue working in close cooperation in Buda Cash group framework. Buda Cash's banks together with their mother investment company became bankrupt in early 2015.

Another example of amending an act in order to enforce the government's will with regards to banks is the amendment of the Act on MNB in July 2015. The aim of amendment was to permit the appointment the deputy governor of MNB for CEO of the MKB Bank. The amendment overstepped the conflict of interest rules, which in their original form would encumber the appointment of the deputy Governor to a commercial bank's CEO.

7 Examples of banking nationalism from the Czech Republic and Poland

The Czech and the Polish banking sectors were not seriously hit by GFC, they are the healthiest in CEE. They accumulated relatively few nonperforming loans and their profitability has remained continuously high. Both governments are convinced that it is the result of high quality domestic banking policy and especially supervision. In the following, we show a few examples as for how banking nationalism affects these countries’ banking policies in a way that clashes with BU's ideals.

Polish policymakers including the Governor of the central bank declared that the banking system's “domestication” would be useful for an effective and well-functioning banking system (CitationNBP, 2011; Rylukowski, 2015). In Poland -similar to Hungary- restructuring bank ownership needs a smooth authorisation, that is easer under domestic supervision. The first step in domestication was the conditional authorisation of acquisition of a Greek-owned Polish bank by Raiffeisen Bank in 2012. The condition was that by mid-2016 either Raiffeisen International lists its shares on the Warsaw Stock Exchange or 15percent of its Polish subsidiary will be listed in form of IPO. At the end of 2015 Raiffeisen announced that it intended to sell the Slovenian and Polish subsidiaries. The Polish Supervisory Authority insisted on conducting the IPO before authorising the sale of the Polish operation. As a consequence, Raiffeisen undertook an IPO and a sale simultaneously, which was not the most logical and effective way to find a new owner (CitationReuters, 2015). More importantly, this kind of authorisation would most probably have been different if exercised by ECB. As the new Polish government elected in 2015 strengthened its commitment towards increasing Polish ownership in banking, further authorisation in favour of domestic owners are expected.

Regarding the Czech Republic there were neither similar actions nor declarations in favour of Czech ownership in banking. However, ring-fencing of foreign capital in banking is the strongest here in the whole of CEE. Signs of ring-fencing are the early introduction of capital conservation buffer; the counter cyclical capital buffer's elevation from zero percent to 0.5 percent in 2015 (valid from 2017) as the only country in the region; and introduction of systemic risk buffer for the four largest banks in a range between 1 to 3 percent in 2014. These capital buffers are in line with the letters of regulation. However, they are outstandingly high relative to the rest of Europe and their calibration definitely aims not only to increase banks’ stability, but also the ring-fencing of foreign capital invested in the Czech subsidiaries. Although ring-fencing is possible even within BU, this high level of its usage by Czech policy makers would surly raise more questions by ECB. This case of ring fencing is on the borderline of nationalism and protectionism.

8 Conclusions

Banking Union is not only the European answer to the financial crisis, but it is also a significant step towards deeper integration. Understanding why three CEE governments opted out may help us better understand the dynamics of EU integration in other policy areas as well. In this article, first, we analysed structural explanations and characteristics of the CEE5 banking systems and found that there are no structural reasons for opt-in or opt-out choices. In the next step, we looked at state capacity. We found that extremely low state capacity conditioned Romania's and Bulgaria's choices. In these countries, joining the BU seems to be the logical choice to overcome government's weakness to maintain financial stability. In Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland state capacity is also low in European comparison, but significantly higher than in Romania and Bulgaria. Authorities are capable of maintaining banking sectors’ stability. Capability, however, does not explain choice; this is why we turned to the analysis of political preferences of opt-out countries. Using the case of Hungary, we found that banking nationalism has strong explanatory power. These governments opted out from BU because such an arrangement leaves greater room for manoeuvring for local politicians to purse banking nationalism.

In a detailed Hungarian case study enriched with Czech and Polish examples we showed how banking nationalism can turn governments against supranational solutions. We detected and documented cases for banking nationalism in all important bank related state functions, i.e. ownership, regulation, and supervision. The case study also documents that banking nationalism results in less transparent and accountable state banking policy that can lead (and in some cases has led) to deterioration in the quality of banking regulation and supervision. Do these countries’ wait-and-see positions mean that they will not join the BU before joining the Monetary Union? On the basis of our research, we believe that their attitude might change for two reasons. First, if state capacity further weakens, governments might lose their ability to maintain financial stability outside the BU. Second, if banking nationalism becomes significantly lower, BU may become more attractive. In the short run, neither solution seems to be highly probable.

References

- C. Bakir , J.J. Woo . Introduction to this issue. Policy and Society. 2016

- M. Čihák , A. Demirgüç-Kunt , E. Feyen , R. Levine . Benchmarking financial system around the world. The world bank policy research working paper 6175. 2012

- S. Csányi . Lecture at the 53. Annual conference of economists. 2015, September. http://privatbankar.hu/penzugyi_szektor/tiltott-allami-tamogatasrol-es-lemarado-magyarorszagrol-beszelt-csanyi-sandor-285182 Accessed 16.01.11.

- Z. Darvas , G.B. Wolff . Should non-euro area countries join the single supervisory mechanism?. Policy Contribution Bruegel. 2013. http://bruegel.org/2013/03/should-non-euro-area-countries-join-the-single-supervisory-mechanism/ Accessed 15.09.07.

- S. De Rynck . Banking on the union: The politics of changing Eurozone Supervision. Journal of European Public Policy. 23(1): 2016; 119–135.

- S. Donnelly . Power politics and the undersupply of financial stability in Europe. Review of International Political Economy. 21(4): 2014; 980–1005.

- ECB the European Central Bank . Banking structures report. 2014, October

- R.A. Epstein . When do foreign banks ‘cut and run’? Evidence from west European bailouts and east European markets. Review of International Political Economy. 21(4): 2014; 847–877.

- R.A. Epstein , M. Rhodes . International in life, national in death? Banking nationalism on the road to banking union. Paper prepared for the ECPR meeting in Salamanca. 10–15, April 2014

- J.A. Frieden . Invested interest: the politics of national economic policies in the world of global finance. International Organization. 45(4): 1991; 425–451.

- J.A. Frieden . Real sources of European currency policy: Sectoral interests and European monetary integration. International Organization. 56(4): 2002; 831–860.

- J.A. Frieden , R. Rogowski . The impact of the international economy on national policies: an analytical overview. R.O. Keohane , H.V. Milner . Internationalization and domestic politics. 1996; Cambridge University Press: New York 25–47.

- G. Garrett . International cooperation and institutional choice: The European Community's internal market. International Organization. 46(2): 1992; 533–560.

- Global Financial Development database. http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/global-financial-development Accessed 28.08.16..

- R. Haas De , Y. Korniyenko , E. Loukoianova , A. Pivovarsky . Foreign banks and the Vienna initiative: Turning sinners into saints?. IMF Working Paper WP/12/117 2012

- D. Howarth , L. Quaglia . The political economy of the new single supervisory mechanism: Squaring the ‘inconsistent quartet’. Paper presented at the ECPR joint session of workshops in Salamanca. 10–15, April 2014

- P. Hüttle , D. Schoenmaker . Should the ‘outs’ join the European Banking Union?. Bruegel policy contribution, 2016/03. 2016. http://bruegel.org/2016/02/should-the-outs-join-the-european-banking-union/ Accessed 16.02.17.

- IMF . Central and Eastern Europe: New Member States (NMS) policy forum. 2014, IMF country report no. 15/98. 2015, April

- J. Johnson , A. Barnes . Financial nationalism and its international enablers: The Hungarian experience. Review of International Political Economy. 22(3 Institutional and Policy Design for the Financial Sector): 2015; 535–569.

- J. Király . A bankszektor átalakítása 2010?. B. Magyar . Magyar polip, a posztkommunista maffiaállam. 3 2015; Noran Libro: Budapest 247–257.

- Kisgergely, K., & Szombati, A. (2014) Banking union through Hungarian eyes - the MNB's assessment of a possible close cooperation, MNB Occasional Papers 115..

- Z. Kudrna , D. Gabor . Political risk, crisis and foreign-owned banks in New Member states. Europe Asia Studies. 65(3 Institutional and Policy Design for the Financial Sector): 2013; 548–566.

- L. Márias . Titkos dossziék a Széchenyi Bank vándorló milliárdjairól. 2014. http://hvg.hu/gazdasag/20150823_titkos_dossziek_a_Szechenyi_Bank_vandorlo Accessed 15.12.09.

- S. McPhilemy . Integrating rules, disintegrating markets: the end of national discretion in European banking?. Journal of European Public Policy. 21(10): 2014; 1473–1490.

- K. Méró , D. Piroska . Macroprudential paradigm shift in Hungarian bank regulation. Special Issue of Külgazdaság, 1 Studies in international economics. 2015, August

- NBP, National Bank of Poland . Press conference after the meeting of the Monetary Policy Council held on 9 November 2011. 2011. http://www.nbp.pl/homen.aspx?.f=/en/aktualnosci/2011/mpc_2011_11_09_rel.html Accessed 15.12.12.

- Raiffeisen Research . CEE banking sector report. 2014. http://www.rbinternational.com/eBusiness/services/resources/media/829189266947841370-NA-988671613168380133-1-2-EN.pdf Accessed 15.12.12.

- Reuters . Exclusive — Raiffeisen to submit Poland unit IPO prospectus in mid 2015. 2015. http://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-raiffeisen-poland-exclusive-idUKKBN0ND2BZ20150422 Accessed 16.02.09.

- W. Rylukowski . Belka: I am in favor of domesticating banks. 2015. http://wbj.pl/belka-im-in-favor-of-domesticating-banks/ Accessed 16.02.09.

- A. Smith . Nations and nationalism in the global era. 1995; Polity Press: Cambridge

- A.B. Spendzharova . Banking union under construction: The impact of foreign ownership and domestic bank internationalization on European Union member-states’ regulatory preferences in banking supervision. Review of International Political Economy. 21(4): 2014; 949–979.

- õ. Várhegyi . A magyar bankszektor szabályozása és versenyhelyzete a válságban. P. Valentiny , F.L. Kiss , C.I. Nagy . Verseny és szabályozás 2011. 2012; 210–238. http://econ.core.hu/file/download/vesz2011/bankszektor.pdf Accessed 15.12.12.

- õ. Várhegyi . A maffiaállam bankjai. B. Magyar . Magyar polip, a posztkommunista maffiaállam. 1 2013; Noran Libro: Budapest 247–257.

- Vienna Initiative . CESEE Deleveraging Monitor. 2012, July. http://vienna-initiative.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/July-2012-Deleveraging-Monitor.pdf Accessed 16.09.09.

- Worldwide Governance Indicators database. 2015. Available from http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/worldwide-governance-indicators Accessed 16 December.

- J.J. Woo . Business and politics in Asia's key financial centres. 2016; Springer: Berlin

- X. Wu , M. Ramesh , M. Howlett . Policy capacity: a conceptual framework for understanding policy competences and capabilities. Policy and Society. 34 2015; 165–171.