Abstract

Should one expect convergence among MPA/MPP programs around the world, and in particularly among programs in the “Anglo-sphere” or among the Anglo-democracies, defined here as Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States. For reasons of shared history and language, one might expect convergence, but there are counter-arguments as well that note, for example, the rich diversity among American programs alone. The paper analyzes 99 programs drawn from among these countries to find an answer. The analysis is wider in scope and more granular than anything that has been done to date, with data that allow comparisons of: (1) subject matter emphasis between policy and management, (2) the amount of required quantitative content, and (3) program length (number of standardized courses required to graduate). After illustrating a standardized metric of comparison we show that the convergence hypothesis cannot be sustained. Our conclusion entertains several conjectures about why this might be the case.

1 Introduction

Should one expect any convergence among MPA/MPP programs in the Anglo-democracies (Australia/New Zealand, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States)? Simple sharing of language (though Canada is officially bilingual) is not enough any longer, as an increasing number of international programs are taught in English. However, there remain several arguments in favour of the convergence hypothesis. One is simply that the post-1945 “internationalization” or “globalization” of these programs is actually the spread of a US “model” (CitationFritzen, 2008), and this model would spread more fluidly through countries that shared a common language, historical ties and culture. Another would be that New Public Management had a specific flavour in the Anglo-democracies, and this would have filtered into academic programs (CitationPollitt, Thiel, & Homburg, 2007). The contiguity of Canada and the US, the proximity of both to the UK, as well as the Westminster parliamentary traditions shared by four of the countries, would also suggest that there should be strong convergence. The spread of quality assurance regimes in higher education has also been argued to be a homogenizing force (CitationJarvis, 2014).

There are counter-arguments as well, however. It is not clear, for example, whether there is substantial convergence even among US programs – CitationEllwood (2008), CitationHur and Hackbart (2009); and CitationLynn (2001) argued yes, but there is ample work (somewhat dated, it is true) to suggest the opposite (CitationBreaux, Clynch, & Morris, 2003; Geva-May, Nasi, Turrini, & Scott, 2008; Kretzschmar, 2010; Straussman, 2008). There was long-standing concern that the NASPAA accreditation process would force curricular convergence in US programs, but the new emphasis on competencies rather than courses has allowed, and even encouraged, divergence (CitationPiskulich & Peat, 2014). As well, while there is a logic of convergence in accreditation processes and in disciplinary boundary-drawing exercises and disciplinary fashions (CitationKettl, 2000; Lynn, 2006), there is also a logic of competition and specialization. Canadian, Australian, and New Zealand programs show a similar mix of convergence and divergence (CitationGeva-May & Maslove, 2006; Pal, 2008; Scott, 2013).

Underlying these debates is an often unstated conceptual issue – what actually counts as convergence? Courses? Core versus electives? Ancillary features of programs such as internships or capstones? The nature of the faculty (training, disciplines)? Since 2009 the CitationNASPAA accreditation standard has focused on competencies, and it is quite clear that different program configurations in terms both of course content and even course requirements (within limits) can all still be demonstrated to meet the given competency requirements (CitationNASPAA, 2009, 2012). So, before even beginning to answer the question of convergence, one needs to have a benchmark or set of parameters for what constitute the elements of MPP/MPA programs.Footnote 1 To do this, the paper draws on the datasets and frameworks developed for the Atlas of Public Management.Footnote 2 The Atlas contains standardized data, drawn primarily from program websites, for 119 programs across 17 countries. At first glance, this range of programs shows a wondrous variety of features, despite the common degree designations. Nonetheless, as academic degree programs in a particular field with reasonably clear contours (more on that below), there are some basic parameters that can be judged to be more or less important. For example, the availability of internships or cooperative education opportunities – an advertised feature of many MPP/MPA programs – can be viewed as nice to have, but not essential. Our analysis of these programs suggests that the three most crucial curricular characteristics are:

| 1. | The subject-matter emphasis, which can be expressed in terms of domains of subject matter within the pedagogical field of public management (defined below); | ||||

| 2. | The amount of quantitative content required, which is usually manifested in the number of courses in economics and quantitative methods expected of the typical student; and | ||||

| 3. | The number of courses required for graduation, which is closely related to the normal time to completion. | ||||

The article proceeds as follows. The following section describes the methodology used to distinguish major attributes of programs. The next section presents a classification system for the entire dataset and discusses its application to the programs in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The article ends with a set of conclusions and suggestions for further research.

2 MPP/MPA programs: a field guide

The Atlas database of curricular content includes course titles (linked to course descriptions and, where available, to detailed course syllabi) for the course offerings in 119 MPP/MPA programs (those offering MPP, MPA and similarly named degrees) in 17 countries.Footnote 3 Courses are assigned to one or other of 34 subjects in the field of public management. The names and descriptions of these subjects – shown in – have been derived from the names used for courses in MPP and MPA programs (drawn from publically available syllabi), the names for ministries in OECD governments, and the names of branches within international governmental organizations providing advice on public policy and management. The resultant array of subjects is broadly consistent with the nomenclature in the canonical literature defining the field: the handbooks (CitationAraral, Fritzen, Howlett, Ramesh, & Wu, 2013; Moran, Rein, & Goodin, 2006; Peters & Pierre, 2006, 2012; Rabin, Hildreth, & Miller, 2007); the encyclopaedias (CitationBerman, 2012; Schultz, 2003; Shafritz, 1997); and the “state of the discipline” articles (CitationKapucu, 2012; Kettl, 2000; Lynn & Wildavsky, 1990).

Table 1 The field of public management: subjects, domains and other attributes.

The 34 subjects can be grouped in various ways to reflect pedagogical distinctions considered relevant to curricular design. The highest-level distinction is between General Preparation (with the further distinction between the “how to” Analysis and Skills subjects, and the “why does” Institutions and Context subjects) and Specific Practice Preparation (with the further distinction between Management Functions subjects and Policy Sectors subjects). These distinctions are reflected in the four domains indicated by the columns in .

As noted above, programs differ in (1) the subject-matter emphasis (the amount and distribution of the subject matter they teach), (2) the quantitative nature of the subject matter of the courses they offer, and (3) the subject matter they include in required courses and the number of courses required for graduation.

The Atlas project addresses the issue of how much is taught through its table of Credit and Course Equivalencies (summarized in ) based on estimates of the total hours of instruction associated with the instructional units used by each program. The one-semester-equivalent course (referred to in many North American universities as “3 credit hours”) is used as the standard unit of instruction, and is taken to be equivalent to 3 h of instruction per week over 12–14 weeks. The number of one-semester-equivalent courses required to graduate for programs in the Atlas database varies between 10 and 20, with most in the range of 12–18.

Table 2 Credit and Course Equivalencies.

In distinguishing among different subject matter for instruction, the Atlas project distinguishes the subjects (and thus the courses assigned to them) on two attributes:

| • | Policy-Oriented subjects vs. Management-Oriented subjects. This distinction harkens back a half century to the 1960s movement to create MPP programs, focusing on policy analysis, to complement MPA programs, focusing on public sector management. Of the 34 subjects in , eight are designated as management-oriented (leadership skills; communication skills; public financial management; human resources management; information and technology management; regulatory policy and management; local government management; and nonprofit management and advocacy), two are designated as both, and the remaining 24 are designated as policy-oriented. These designations are intended to represent emphases rather than absolutes since most of the 34 subjects include a blend of policy- and management-oriented material. | ||||

| • | Mathematics-Economics intensive subjects vs. Other subjects. This distinction is important for determining the academic preparation of both teaching faculty and students. The four mathematics-economics subjects (economic analysis; quantitative methods; macroeconomic policy; and financial markets) tend to be taught by economists and students usually require some undergraduate preparation in economics and statistics. | ||||

For each program one can calculate the proportion of enrolment-adjusted course offerings (PEACO) in each subject. The PEACO algorithmFootnote 4 takes account of the difference between a required and an elective course by assuming that the probability of a typical student taking take a course is equal to the number of electives taken available divided by the number of elective courses offered. One can then compare the PEACO profiles of the programs along the three attributes of domain, policy/management orientation, and mathematics-economics.

As an illustration of PEACO results, shows two programs – Columbia University in New York and the University of Victoria in British Columbia – that have the same degree designation (MPA) but which have, according to our PEACO analysis, very different programmatic profiles. The Columbia MPA is a high mathematics-economics, policy-oriented (the typical student takes more than 60% of her courses in policy-oriented subjects) program, while the Victoria MPA is a lower mathematics-economics, management-oriented program (the typical student takes more than 40% of her courses in management-oriented subjects). The differences are quite stark. Whereas the Columbia degree has a score of 79% for policy-oriented subjects, the Victoria degree has 37%. The mathematics-economics quotient for Columbia is 26%, while the Victoria quotient is 19%. On the other hand, Columbia's MPA has a quotient of 21% for management subjects, while Victoria's MPA has a quotient of 63%. As noted above, these scores are based on an algorithm that takes account of the likely distribution of electives, and the balance of core/required courses and electives in the program. While the PEACO algorithm is based on a number of assumptions and approximations, it provides a better snapshot of programs than a simple assessment of required or core courses. Another point to note is that both the Columbia and Victoria MPAs are recognized as strong exemplars within their respective “Anglo-sphere” countries and have the same degree designation, but are significantly different.

Table 3 PEACO scores.

3 A classification of curricular types

presents the full classification of curricular types, using the following criteria: (1) course requirements (high, medium, low), (2) subject matter emphasis (policy or management), (3) mathematics-economics content (higher versus lower). This yields a 12-cell classification of the programs in the Atlas database. For ease of reference, each type is named for a pair of representative programs. shows the entire database, while shows only the 99 programs in the countries of focus for this paper: Australia/New Zealand, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Of a total of 99 programs, the distribution among those countries is: Australia/New Zealand: 11, Canada: 24; UK: 11, and US: 53. Across the total of programs, there is an almost even split between policy-oriented (56) and management-oriented programs (43).

Table 4 Curricular types.

Table 5 Curricular types – “Anglosphere”.

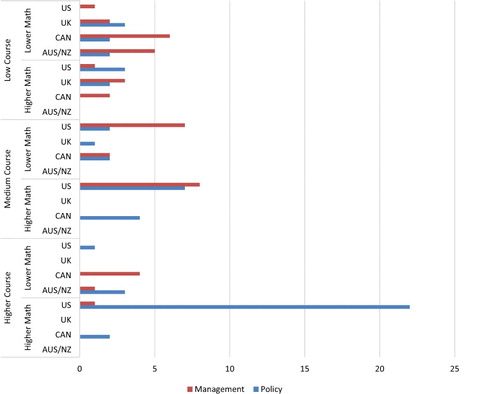

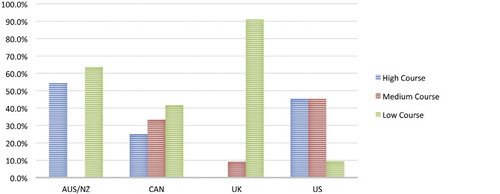

shows the distribution among countries in raw numbers. Obviously the United States dominates, with a total of 53 programs out of 99. But even a quick look at the chart shows that US programs tend to be concentrated in the higher-course category. shows the percentage distribution in percentage terms, and 90% of US programs are evenly spilt into the two categories of high-course and medium-course requirements. It is still notable that about half of US programs have course requirements of between 16 and 20 courses to complete their programs. UK programs, but contrast, are clearly concentrated (at about 90%) in the low-course category. The Australia/New Zealand programs are evenly split between low and high, while Canada shows a more even distribution across high-, medium-, and low-course requirements, though the tilt is clearly towards lower course requirements, thereby once again confirming the adage that Canada is “in-between” the UK and the US in all things.

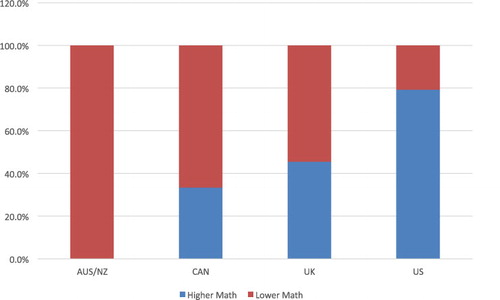

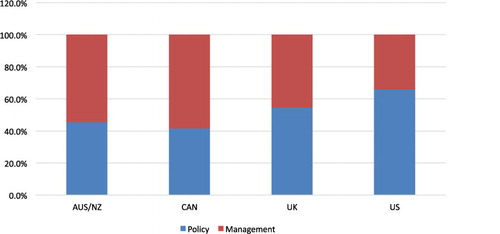

One can also distinguish among programs in terms of their mathematics-economics emphasis, and the distinction between management- or policy-oriented degrees. The contrast among countries on this dimension is even more striking (). The Australia/New Zealand programs are 100% in the lower mathematics/economics (including quantitative methods). Canada has about two-thirds of its programs in the lower-mathematics category, the UK is almost evenly split, but the US is predominantly (80%) higher-mathematics. One could hypothesize that programs with more of a policy orientation will put a higher premium on mathematical and related skills, since those programs usually demand more analytical skills. Programs with a the more traditional management or administration orientation would therefore be likely to have less emphasis on quantitative skills. The problem of course is that while programs carry different designations – MPA versus MPP – in reality it is quite possible to have a strong policy orientation even in an MPA degree, for evolutionary reasons (i.e., the program began as a management degree but then over time, as faculty and fashions changed, added more policy), or because of available concentrations (i.e., if a policy concentration becomes popular within a management degree), or because of regulatory restrictions on degree names (i.e., if a jurisdiction does not recognize the MPP designation, as is the case in New York State). Perhaps because of these or other reasons, shows a much more even division between policy and management orientations than one might expect from the emphasis in national programs on mathematics and economics. All programs in Australia/New Zealand, for example, were in the lower-mathematics category, and yet about 45% of their programs are policy-oriented. The US is a little closer to expectations, with almost exactly two-thirds of its programs being policy-oriented, and as already noted, almost 80% of all programs in the higher-mathematics category. Nonetheless, this should caution against too easy an equivalence between policy and “harder” analytical skills.

4 Conclusions

These results clearly challenge the convergence hypothesis in several ways. First, as noted at the beginning of the paper, US programs alone show a remarkable diversity across our categories, even while indicating a certain “tilt” towards lengthier, more policy- and quantitatively oriented programs. Second, despite whatever historical, cultural, linguistic, and professional connections one might make among these Anglo-democracies, they differ quite sharply. One could deliberately select a more “US-style” program in any one of the countries, but if one were selecting programs at random, there are greater probabilities of selecting one clear “national” type within each country.

The analysis in this article has been static – a snapshot of programs circa 2013–2015. It is worth asking a more dynamic question, and that is whether programs are in a process of converging or diverging? That question is beyond the scope of this paper, but one might perhaps speculate that there was a “golden age” of convergence in the 1990s. The collapse of the Soviet Union, for example, led to the establishment of MPA/MPP programs through central and Eastern Europe (CitationEisfeld & Pal, 2010), and the Network of Institutes and Schools of Public Administration in Central and Eastern Europe (NISPAcee) was established with the assistance of USAID and NASPAA. The public policy discipline first arose in the US in the 1980s, as did MPPs as a consequence, and there was likely to be an exportation of the “Berkeley” or “Harvard” models throughout the English-speaking academic sphere (CitationMahbubani, Yiannouka, Fritzen, Tuminez, & Tan, 2013). It would not be unnatural, after a time of rapid dissemination and convergence, for a certain divergence to take place. The 2013–2015 observations presented here may reflect that “age of divergence” more than an earlier “age of convergence.”

Be that as it may, our findings suggest that it is important to reflect on the various factors that might encourage divergence and differentiation. First, on the forces of divergence. As noted above, there is a natural competitive dynamic, at least within national MPP/MPA markets. This competition usually has to be on a level playing field of credentialization – almost every jurisdiction in the world will require some sort of licensing and approval of graduate programs, which is to the advantage of those programs since they want to be able to claim that the credential will be recognized within the jurisdiction (if not beyond) as bona fide. So there is always a delicate balance between meeting some minimal quality assurance standard for licensing, and differentiating oneself in the market. Once established, however, programs do have incentives to diverge and distinguish themselves. Sometimes this differentiation is driven by internal university dynamics. MPA and MPP programs often have to position and defend themselves vis-à-vis their particular sister business schools and political science departments. On the other hand, in more collaborative contexts, they can build on niche programming in those sister units. The other driver in differentiation is simply that the national markets for MPAs and MPPs (i.e., administration and policy) inevitably have national profiles and characteristics. Programs like the Harvard Kennedy School's MPP and MPA might plausibly claim that they can train high-level generic skills that apply as well in Boston as they do in Beijing, but there is an inevitable “stickiness” to these programs. Nonetheless, there are programs that can claim a strong international profiles and hence transferrable skills, but this depends on a mix of factors: (1) being a program in a top-ranked university like Harvard, Berkeley, or Oxford (CitationWildavsky, 2010), (2) being a top-ranked program, irrespective of the university, as is the case for the Syracuse MPA in the US News & World Report rankings, (3) laying claim to a concentration of leading scholars in the field (this tends to overlap with the first two), (4) being a dominant school in a regionally dominant country, such as Tsinghua University in China, or (5) occupying a distinctive niche that is of international interest (e.g., Islamic finance).

This logic of differentiation is strengthened further in that administration and policy are not only national in character, but often have a regional flavour. This is clearly the case with the US, Canada, and Australia, both as large countries and as federal states. Western Canadian programs, for example, will naturally emphasize some aspects of petroleum and other resources, while ones in central Canada would not. Carleton's MPPA, for example, while located in the national capital, has a diploma in indigenous administration, and several western Canadian programs do as well, simply because of the concentration of indigenous peoples in those parts of the country.

Another contributing factor to divergence is the emerging trend towards competency-based quality assurance systems. It has been noted above that the current NASPAA accreditation process, in contrast to its predecessor, does not highlight specific courses or even subject-matter per se. Instead, NASPAA has identified key competencies that it presumes an MPP/MPA graduate should have, and then encourages programs seeking accreditation to demonstrate – in terms of their specific course and program configurations and overall “mission” – how they will deliver (and assess) these competencies among their graduates. These competencies are not empty categories of course, and someone who has mastered them will have a different skill profile than an engineer or a philosopher. But they are considerably more flexible than the previous model, which demanded certain key courses in certain key areas. This expands the program design palette, and in principle encourages more vibrant program renderings than before.

Our second, speculative observation is posed as question: even if our analysis shows divergence, are we in fact looking in the right place? This is not a case of resisting our own evidence, but of giving due weight to a vivid perception that the field as it is practiced and taught today is more closely bound, more integrated in some sense, as a result of globalization. At the level of practice, for example, we are all aware of the global public management revolution (CitationKettl, 2005), the role of international organizations in promoting that revolution (CitationPal, 2012), and even if the impact was variable (CitationPollitt & Bouckaert, 2011), it led to a global conversation on the contributions of administrative institutions to good governance (CitationFukuyama, 2013; Holt & Manning, 2014). At the level of pedagogy, programs in the Anglo-democracies are increasingly marketing themselves internationally drawing in more international students, who often return to their home countries as officials or as teachers. Key books and articles are more easily accessible around the world, and there exists a super-stratum of global teachers and administrators who teach in multiple programs, work with scattered networks of research colleagues, and have students from around the globe. We may have an apparent paradox of more differentiated programs coupled with a more tightly integrated or harmonized set of practices and communities. As always, further research awaits.

Notes

1 “MPP/MPA programs” (or “MPA/MPP programs”) is the generic term used in this paper for Master's programs in public policy, public administration, public affairs and similarly sounding fields of study.

2 Available at: http://www.atlas101.ca/pm/. This is the successor to a previous web portal, The Atlas of Public Policy and Management, which was part of a research project launched in 2008 and funded by the Canada School of Public Service and the Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (grant #435-2012-1248). The current Atlas contains datasets on: (1) programs: over 100 international MPP/MPA programs, (2) courses: the syllabi of “specimen” courses from these programs, (3) topics: 120 core topics common to many MPP and MPA programs, (4) concepts: definitions and sources for over 1000 disciplinary concepts, and (5) advice: “best practice” advice on public management from international governmental organizations.

3 The Atlas sample of 119 programs includes all Canadian programs, and all programs offered by the most research intensive universities in the UK, Australia and New Zealand, as well as the principal English-speaking programs in Europe and Asia. The sample has 53 programs from the United States. These 53 programs include the most highly ranked programs in the US News & World Report ranking Public Affairs schools as well as a number of other programs that provide extensive course descriptions on their public websites.

4 The PEACO number for any characteristic (e.g., “analysis and skills courses” or “institutions and context courses”) is the proportion of the overall course offerings with that characteristic, after making an adjustment for the number of students expected to enrol in the course. For example, an “analysis and skills PEACO” of 0.25 means that, on average, 25% of the courses taken by students in completing their degrees are can be classified as “analysis and skills courses.”

The enrolment adjustment is made by assuming that all students take required courses and that enrolment in elective courses is evenly spread over the elective courses available, given the number of electives that a student needs to graduate and the number of available elective courses (or elective course sections, where an elective has more than one section in a year). An adjustment is made for relative credit where an elective is shorter than a normal required course and has a fractional credit value.

The enrolment-adjustment factor for an elective course = ([minimum number of electives that a student may take] × [course credit relative to a required course] × [number of sections of that elective offered in a year])/[total number of elective courses and sections offered in a year].

The PEACO number for a given characteristic = ([number of required courses with that characteristic] + ([number of elective courses and sections with that characteristic] × [enrolment-adjustment factor]))/[number of courses required to graduate].

The validity of the three simplifying assumptions implicit in this methodology (students do not take more than the minimum number of electives; students take all their electives from within the program; and, all elective courses and sections have the same enrolment) will differ among programs.

References

- E. Araral , S. Fritzen , M. Howlett , M. Ramesh , X. Wu . Routledge handbook of public policy. 2013; Routledge.: New York

- E.M. Berman . Encyclopedia of public administration and public policy. 2nd ed., 2012; CRC Press.: Boca Raton, FL

- D.A. Breaux, E.J. Clynch, J. Morris . The core curriculum content of NAPSAA-accredited programs: Fundamentally alike or different?. Journal of Public Affairs Education. 9(4): 2003; 259–273.

- R. Eisfeld, L.A. Pal . Political science in Central and Eastern Europe: Diversity and convergence. 2010; Barbara Budrich.: Farmington Hills, MI

- J.W. Ellwood . Challenges to public policy and public management education. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 27(1): 2008; 172–187.

- S.A. Fritzen . Public policy education goes global: A multi-dimensional challenge. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 27(1): 2008; 205–214.

- F. Fukuyama . Commentary: What is governance?. Governance. 26(3): 2013; 347–368.

- I. Geva-May, A. Maslove . Canadian public analysis and public policy programs: A comparative perspective. Journal of Public Affairs Education. 12(4): 2006; 413–428.

- I. Geva-May, G. Nasi, A. Turrini, C. Scott . MPP programs emerging around the world. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 27(1): 2008; 187–204.

- J. Holt, N. Manning . Fukuyama is right about measuring state quality: Now what?. Governance. 27(4): 2014; 717–728.

- Y. Hur, M. Hackbart . MPA vs. MPP: A distinction without a difference?. Journal of Public Affairs Education. 15(4): 2009; 397–424.

- D.S.L. Jarvis . Regulating higher education: Quality assurance and neo-liberal managerialism in higher education – A critical introduction. Policy and Society. 33 2014, September; 155–166.

- N. Kapucu . The state of the discipline of public administration. Public Administration Review. 72(3): 2012; 458–463.

- D.F. Kettl . Public administration at the millennium: The state of the field. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 10(1): 2000; 7–34.

- D.F. Kettl . The global public management revolution. 2nd ed., 2005; Brookings Institution Press.: Washington, DC

- B. Kretzschmar . Differentiated degrees: Are MPA and MPP programs really that different?. Perspectives in Public Affairs. 7(Spring): 2010; 42–67.

- L.E. Lynn Jr. . Globalization and administrative reform: What is happening in theory?. Public Management Review. 3(2): 2001; 191–208.

- L.E. Lynn Jr. . Public management: Old and new. 2006; Routledge.: New York

- N.B. Lynn , A. Wildavsky . Public administration: The state of the discipline. 1990; Chatham House.: Chatham House, NJ

- K. Mahbubani, S.N. Yiannouka, S.A. Fritzen, A.S. Tuminez, K.P. Tan . Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy: Building a Global Policy School in Asia. 2013; World Scientific Publishing Co..: Singapore

- M. Moran , M. Rein , R.E. Goodin . The Oxford handbook of public policy. 2006; Oxford University Press.: Oxford

- NASPAA . NASPAA accreditation standards for master's degree programs. 2009. Retrieved from http://www.naspaa.org/accreditation/NS/naspaastandards.asp: .

- NASPAA . NASPAA standards 2009: Self study instructions. 2012. Retrieved from http://www.naspaa.org/accreditation/NS/selfstudyinstruction.asp: .

- L.A. Pal . The challenge ahead: A comparison of Canadian masters programs in public administration, public management and public policy, 2008. 2008. Retrieved from Toronto.

- L.A. Pal . Frontiers of governance: The OECD and global public management reform. 2012; Palgrave Macmillan.: Houndmills, Basingstoke

- B.G. Peters , J. Pierre . Handbook of public policy. 2006; Sage.: Thousand Oaks, CA

- B.G. Peters , J. Pierre . The Sage handbook of public administration. 2nd ed., 2012; Sage.: Thousand Oaks, CA

- C.M. Piskulich, B. Peat . Assessment of universal competencies under the 2009 standards. Journal of Public Affairs Education. 20(3): 2014; 281–284281.

- C. Pollitt, G. Bouckaert . Public management reform: A comparative analysis – New public management, governance, and the neo-Weberian state. 3rd ed., 2011; Oxford University Press.: Oxford

- C. Pollitt, S.v. Thiel, V. Homburg . New public management in Europe: Adaptation and alternatives. 2007; Palgrave Macmillan.: New York

- J. Rabin , W.B. Hildreth , G.J. Miller . Handbook of public administration. 3rd ed., 2007; CRC Press.: Boca Raton, FL

- D. Schultz . Encyclopedia of public administration and public policy. 2003; Facts on File.: New York

- C. Scott . Teaching policy analysis in cross-national settings: A systems approach. Journal of Public Affairs Education. 19(3): 2013; 433–443.

- J. Shafritz . International encyclopedia of public policy and administration. 1997; Westview Press.: Boulder, CO

- J.D. Straussman . Public management, politics, and the policy process in the public affairs curriculum. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 28(3): 2008; 624–635.

- B. Wildavsky . The Great Brain Race: How global universities are reshaping the world. 2010; Princeton University Press.: Princeton