Abstract

Abstract

As governments around the world prepare to adopt a new development framework and supportive financial flows, the OECD Development Assistance Committee is exploring new ways of measuring and reporting on resource flows enabling development, including population assistance. These changes will affect the evidence base, discourse about and donor incentives related to sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR). They may lead to: i) reduction of grant aid in favour of instruments that are less suitable for SRHR, like loans and market-like instruments; ii) expansion of the range of development stakeholders to include those with market power that can steer the discussion away from the needs of the most under-served populations; and iii) diversion of attention and resources away from SRHR. The discourse over how to provide, incentivize and report on development assistance in the new framework demonstrates the crucial relationship between knowledge, evidence, practice and power in relation to funding for SRHR in developing countries. With all that is at stake, although the OECD debate on the future of the development finance measurement system may seem highly abstract, this is a high-stakes game that SRHR advocates need to have a hand in. Those who seek to improve SRHR are well served to engage in these discussions as early and often as possible before the momentous decisions over the coming months.

Résumé

Alors que les gouvernements dans le monde se préparent à adopter un nouveau cadre du développement, assorti de flux financiers le soutenant, le Comité d’aide au développement de l’OCDE étudie de nouvelles méthodes de mesure et de notification des flux de ressources permettant le développement, y compris l’assistance en matière de population. Ces changements affecteront la base de connaissances, le discours s’y rapportant et les encouragements des donateurs en matière de santé et droits sexuels et génésiques. Ils peuvent aboutir à : i) une réduction de l’aide sous forme d’allocations au profit d’instruments moins adaptés à la santé et aux droits sexuels et génésiques, comme les prêts et les instruments de marché ; ii) l’élargissement de l’éventail d’acteurs du développement pour inclure ceux qui ont une puissance de marché, capables d’éloigner la discussion des besoins des populations les plus sous-desservies ; et iii) le détournement de l’attention et des ressources de la santé et des droits sexuels et génésiques. Le discours sur la manière de prodiguer, stimuler et notifier l’aide au développement dans le nouveau cadre démontre les relations cruciales entre les connaissances, les faits, la pratique et le pouvoir en rapport avec le financement de la santé et des droits sexuels et génésiques dans les pays en développement. Eu égard aux enjeux, ceux qui souhaitent améliorer la santé et les droits sexuels et génésiques ont intérêt à participer à ces discussions sans attendre et aussi souvent que possible, avant les décisions capitales de ces prochains mois.

Resumen

A medida que los gobiernos del mundo se preparan para adoptar un nuevo marco de desarrollo y flujos financieros de apoyo, el Comité de Ayuda al Desarrollo de la OCDE está explorando nuevas maneras de medir y reportar flujos de recursos que permiten el desarrollo, incluida la ayuda a la población. Estos cambios afectarán la base de evidencias, el discurso y los incentivos de donantes relacionados con la salud y los derechos sexuales y reproductivos (SSR y DD. SS. RR.). Posiblemente lleven a: i) reducir la ayuda financiera a favor de instrumentos menos aptos para SSR y DD. SS. RR., como préstamos e instrumentos similares a los del mercado; ii) ampliar la variedad de partes interesadas en el desarrollo para incluir a aquéllos con poder de mercado que puedan alejar la discusión de las necesidades de los sectores más desatendidos de la población ; y iii) desviar la atención y los recursos de SSR y DD. SS. RR. El discurso sobre cómo brindar, incentivar y reportar la ayuda para el desarrollo en el nuevo marco demuestra la relación crucial entre conocimiento, evidencia, práctica y poder con relación al financiamiento para SSR y DD. SS. RR. en los países en desarrollo. Con todo lo que está en juego, a las personas que buscan mejorar la SSR y DD. SS. RR. les vendría bien entablar estas discusiones lo más temprano y frecuente posible antes de las decisiones trascendentales en los próximos meses.

Key Words:

- population assistance

- sexual and reproductive health and rights

- Sustainable Development Goals

- economic development

- Official Development Assistance

- donors

- emerging donors

- grants

- loans

- concessional lending

- low-income countries

- least developed countries

- middle-income countries

- Total Official Support for Development

- international financial flows

- health expenditures

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Development Assistance Committee (OECD DAC)

- private sector financing

- public-private partnerships

As the global community negotiates a new set of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to end extreme poverty by 2030, parallel negotiations for the 3rd International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD 3) will determine how to finance the new global framework. At the level of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), technical experts and donor representatives have been working since 2012 on proposals to modernize the Official Development Assistance (ODA) definition and improve the measurement and monitoring of financial flows overall. In December 2014, DAC Ministers at a High-Level Meeting finalized reform proposals to inform global FfD and SDG negotiations.

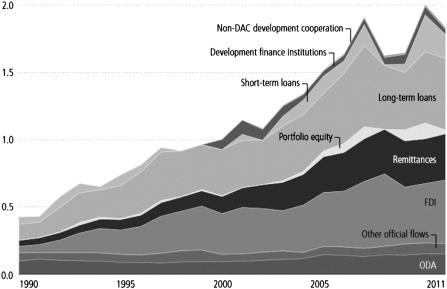

The scale and diversity of international resource flows to developing countries have changed significantly since the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were agreed in 2000 (). Even though ODA provided by donor governments increased only slightly, overall international flows, including remittances, foreign direct investments, non-ODA loans and market-like instruments, more than doubled.

Fig. 1 International resource flows to developing countries (in 2011 US$ millions).Citation1

Partly because of this, FfD in the post-2015 framework will go beyond traditional ODA and include commitments from other development actors, including Development Finance Institutions (DFIs), new emerging donors and the private sector.

This paper analyses the potential consequences of development finance reform, ODA modernization and the future measurement system at the DAC for SRHR financing. It outlines major DAC reform proposals and decisions (current at this writing); identifies risks and opportunities for SRHR financial allocations post-2015Footnote*; and provides concrete recommendations for decision-makers and SRHR advocates to strengthen the discourse on SRHR financing leading up to 2015’s major events.

Overall funding for SRHR

The international community has reaffirmed the importance of SRHR by including specific targets in official SDG proposals. However, with an annual US$ 68.2 billion funding gap for SRHR in developing countries, including US$ 10.3 billion missing from donors, progress implementing the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) and achieving MDG5 has been limited to date.Citation2–5

| • | 300,000 women died and 6 million women suffered severe injuries and disabilities as a result of pregnancy and childbirth in 2013; | ||||

| • | More than 200 million women lacked access to a modern method of contraception; | ||||

| • | 16 million girls aged 15–19 years gave birth every year; | ||||

| • | 40 million births in developing regions were not attended by skilled health personnel in 2012; and | ||||

| • | 21.6 million unsafe abortions took place in 2008.Citation6 | ||||

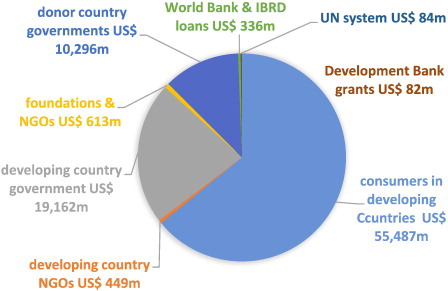

The DAC Creditor Reporting System uses “purpose codes” that enable bilateral and multilateral donors to indicate where they direct their development aid, i.e. the sectors and purposes they intend to support. However, many of these are broad enough to obscure the nature of the information, services or supplies being provided. In the past, the UNFPA/NIDI Resource Flows projectCitation3 (now coming to an end) has combined in-depth analysis of the Creditor Reporting System data with other sources – e.g. developing country governments, World Health Organization – to identify “hidden” ICPD disbursements, estimate private out-of-pocket expenditure and enable an overall picture of resources (). According to this project, US$ 86.5 billion was allocated for items included in the ICPD Programme of Action costed package in 2012. Domestic support for SRHR – 87% of all known financial flows – far exceeded the two-thirds agreed as a fair share in 1994.Citation3 At 64% of total financial flows, private out-of-pocket expenditures by consumers in developing countries represented the single largest source of funds for SRHR in developing countries, above all other sources of international or domestic finance.

Fig. 2 ICPD costed package financing in 2012 (US$ millions)Footnote†† Citation3

International public finance for development and SRHR

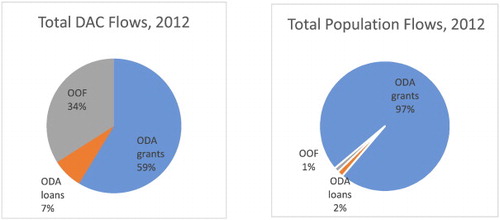

International public finance as measured by the DAC includes three main types of financial flows: ODA grants, ODA loans and Other Official Flows (OOF). They all qualify as international public flows, as they are transferred by donor governments (public as opposed to private actors) and are transferred internationally (as opposed to domestically).

In the existing DAC framework, ODA is defined as “[g]rants and concessional loans for development and welfare purposes from the government sector of a donor country to a developing country or multilateral agency active in development”.Citation7 International public loans and other new “market-like instruments” (explained below) can be provided by donors either at market terms or at softer “concessional” terms. “Concessional” terms are less expensive than could be accessed on the open market. When it comes to loans and market-like instruments, only those offered at concessional terms qualify as ODA.

In addition to ODA, the DAC tracks Other Official Flows by donor governments and agencies to developing countries. They include official loans which support development and welfare in the partner country (and thus have the same objective as ODA loans), but which do not offer sufficiently concessional terms to qualify as ODA. Other Official Flows also include: other official loans not directed to development or welfare purposes (e.g. commercial loans), export credits, and a small number of non-ODA grants.

While ODA grants provide the largest share of international public finance for development cooperation overall (59% in 2012), they are by far the most significant funding modality for population assistance specifically (97%). And while ODA loans (7%) and OOF (34%) constitute significant elements of total public development flows, their shares of overall population assistance as measured by the DAC are marginal ().

Fig. 3 International public flows 2012: total and for population assistanceFootnote‡‡

Two Development Finance Institutions provided OOF for population assistance in 2012, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (US$ 117 million) and the Asian Development Bank (US$ 1.11 million). Most ODA loans for population assistance in 2012 came from the World Bank’s International Development Association (US$ 131 million), followed by Japan (US$ 9.8 million), the African Development Fund (US$ 9.1 million), Germany (US$ 4.4 million) and France (US$ 1 million).Citation8

Modernization of development finance

The DAC is now reforming its measurement system for international public finance in order to refresh outdated reporting rules and to better capture major changes in non-ODA financial flows, such as:

| • | Donor government use of new financial mechanisms that do not qualify as ODA (e.g., market-like instruments). | ||||

| • | New “Southern” donors providing resources not systematically tracked at the DAC. | ||||

| • | Development loans representing a growing share of ODA. | ||||

The DAC is revising the concept of what constitutes ODA, and international public finance as a whole, to potentially encompass a wider variety of donors and donor-funded activities.

The DAC effort to modernize its international development finance measurement and reporting system is focused onCitation9:

| 1. | A new measure of “total official support for development” (TOSD), to better capture the total donor effort in development cooperation, beyond ODA and OOF. | ||||

| 2. | A modernized ODA definition to improve the DAC statistical system to include, among other things, global public goods (e.g. climate) that enable development, and to modify the way ODA loans are calculated and reported. | ||||

| 3. | An increased focus on international public finance for the world’s poorest countries, including Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Low-Income Countries (LICs), to reverse recent trends of declining donor funding. | ||||

To ensure coherence with the SDG process and enhance accountability for outstanding ODA commitments, such as the EU donor target to achieve 0.7% ODA/GNI by 2015, any changes in ODA and development finance measurement will apply at the earliest for flows from 2016 onwards.

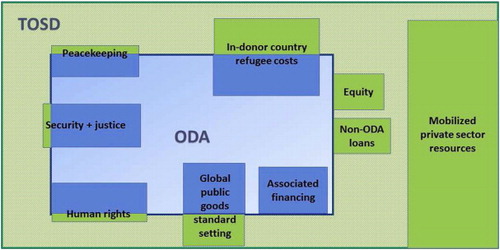

Total Official Support for Development (TOSD)Footnote†

DAC Ministers in 2014 agreed to create a new TOSD measure under which all international public finance resources for sustainable development will be considered, regardless of their terms and conditions. Within TOSD, the DAC wants to better capture international public flows to sectors that are not ODA eligible (i.e. without economic development and welfare as main objective), in areas that are considered global public goods or “enablers of development”. Two noteworthy features of TOSD are discussed below:

| 1. | TOSD will continue to focus on official flows, enabling “non-DAC” public providers of development finance to align with TOSD measurements in support of the SDGs. | ||||

| 2. | TOSD includes activities that promote economic development and welfare, but not necessarily as a main objective. TOSD activities may be designed to benefit finance providers, e.g., for market-like instruments. Private flows, even those mobilized by TOSD public flows, will not be included in TOSD, but the DAC will aim to measure them separately.Citation10 | ||||

While many of the new potential areas are currently partly included in ODA (e.g. 6% of UN peacekeeping missions in developing countries), TOSD could include non-ODA flows for security and justice; peacekeeping missions; climate finance; human rights (e.g. contributions to Amnesty International); standard setting for global public goods in international organizations; and non-ODA refugee spending in donor countries.

indicates the potential order of magnitude of TOSD and its implications for DAC ODA reporting in the future. In the future, donors could report a greater share of the funding flows mentioned above as ODA (shaded in blue), in particular more funding for UN-mandated peacekeeping operations, security and justice, human rights, and standard setting for global public goods. In addition, over half of in-donor refugee costs in the first year of a crisis and “associated financing” could count as ODA. The remaining shares of those costs, e.g. the other half of in-donor country refugee costs, would be included in TOSD (shaded in green) next to other non-ODA flows such as equity investments, loans that do not qualify as ODA and mobilized private sector resources.

Fig. 4 Order of magnitude of possible TOSD components in pilot studyFootnote§§

The concept of TOSD will help the development community better capture overall funding for development. The representation of SRHR in the overall financing discourse will likely shrink as population assistance depends on ODA grants, which will only constitute a small part of TOSD. Nonetheless, TOSD may highlight population assistance underfunding and the massive gap between financing and supportive policies.

Following the DAC decision to create TOSD, further details will be presented at the FfD3 conference. Following adoption of the SDG framework in September, all purpose codes and thematic areas, including population assistance, will be aligned with the SDGs and will apply equally to TOSD and ODA. As the UNFPA/NIDI Resource Flows project ends, SRHR stakeholders will need to find new solutions to address limitations of DAC and other resource tracking for the ICPD costed package that will continue to exist in the reformed measurement system.

“Non-DAC” international public financial flows

The DAC system changes aim at clarifying and addressing non-DAC donor contribution issues – such as differences in terminologies or participation in DAC decision-making – to give a more complete picture of international public flows in support of SDG commitments.Citation11 The DAC’s existing measurement system is based on data received from traditional donors. However, emerging donors provide an increasing amount of international public flows.

More than an estimated US$ 138 billion in development finance was invested by non-DAC donors in developing countries in 2012, including 17 emerging donors that already report concessional development finance, or “ODA-like flows”, to the DAC. However, with the exception of Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates, these donors are reporting at aggregate level only. Resource flows by other donors such as China, India and Brazil are not yet captured in a coherent way, which allows for only rough estimates.Citation11 As it aims to be “relevant for any provider of development finance”,Citation12 TOSD may promote greater coherence and alignment by non-DAC donors and South-South cooperation.

It is currently impossible to obtain comprehensive, detailed information on population support from emerging donors, but some data are available online.

| 1. | South Korea’s Health StrategyCitation13 identifies improvement of maternal and child health, family planning, and prevention of HIV/AIDS as top priorities. South Korea disbursed US$ 50.21 million for health in 2011, mostly (71%) to improve access to health services generally, but with 5% (US$ 2.73 million) for maternal and child health and family planning. | ||||

| 2. | Chinese development assistance is non-transparent; however, sources indicate that between 2003 and 2012, 11 African projects may have received a total US$ 4.86 million in population assistance, including US$ 3.6 million for hospital construction in Cameroon. This compares with US$ 275 million for overall health in Africa and US$ 9.2 million for construction of a women’s centre in Chad in 2012.Citation14 | ||||

| 3. | Turkey includes health as one of its main development assistance priorities, having provided US$ 9.8 million in 2012. Turkey reports contributing an additional US$ 0.43 million for population and reproductive health in 2012.Citation15 | ||||

Better DAC tracking of other sources of international public flows, especially for SRHR, could lead to better policymaking, improved coordination of donor efforts for overall results, and better advocacy for funding to meet SRHR needs.

Development Finance Institutions and market-like instruments

In addition to emerging public bilateral donors, a number of DFIsFootnote‡ report to the DAC. However, comprehensive and systematic data collection on all 35 bilateral and multilateral institutions is currently missing. In practice, this means that a considerable amount of international public flows for development is currently unaccounted for (see Fig. 4). Estimates show that DFIs allocated a total of US$ 104 billion in 2011, of which US$ 38 billion were not captured by ODA or OOF categories.Citation1

With regard to population assistance, DAC data show that six DFIs provided financial flows in the form of ODA (US$ 187 million) and Other Official Flows (US$ 118 million) in 2012: the World Bank’s International Development Association and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the African Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, Arab Fund (AFESD) and the OPEC Fund for International Development. However, it is difficult to find comprehensive evidence for SRHR support from DFIs, so improved OECD data collection on DFIs activity is welcome.

DFIs and DAC members reportedly channel increasing amounts of official finance through new financing mechanisms to mobilize private investment in developing countries. These so-called “market-like instruments” are not measured by the DAC, so comprehensive data are not available. A 2013 DAC survey reports that total official guarantees of private investment in developing countries alone mobilized US$ 6.4 billion in 2011, while the risk taken by the guarantor (measured as net exposure) was US$ 4.9 billion.Citation16

If the TOSD measure incentivizes donors to increase funding through market-like instruments, they are likely to be more common in the near future. This provides the SRHR (and the broader health) community with an opportunity – to leverage additional private capital toward achieving ICPD outcomes – and a challenge – to ensure ICPD outcomes in poor countries are efficiently and effectively improved by private capital. The latter will be difficult considering the scarcity of data on private financing of ICPD outcomes and the voluntary nature of reporting by private entities. The Global Financing FacilityCitation17 (GFF) in support of the Every Woman Every Child Global Strategy for Women’s and Children’s Health,Citation18 to be launched at FfD3 in July 2015, illustrates the upcoming importance of new (beyond ODA grants) instruments for health and population assistance. USAID, the largest donor in the world, indicated that it would support the GFF through innovative financing mechanisms and public-private partnerships (PPPs). Even while there is confusion about the term PPP,Citation19 the GFF illustrates that the private health sector is getting more attention and funding in development finance.Citation20,21

Expansion of the ODA definition

As the Development Assistance Committee looks for ways to better measure TOSD in the overall changing FfD landscape, some argue that the new, holistic sustainable development approach makes it artificial to exclude global public goods such as climate change and peace/security from the definition of ODA itself. Several DAC members have called for these financial flows to be included in future measurement of ODA within TOSD. The DAC now tracks most climate-related ODA and Other Official Flows to help monitor the international commitment of US$ 100 billion for climate change by 2020. While climate-related ODA already represents 15% of total bilateral ODA commitments, some argue that additional elements – carbon capture and storage, early-stage mitigation technology development and carbon market finance flows – should not only be captured under the new TOSD measurement but be considered as ODA. Similarly, while ODA currently excludes military equipment and service financing, military components of peacekeeping operations and combating terrorism, some argue that 100% rather than the current 6% of contributions to UN peacekeeping operations could be counted as ODA. Like with TOSD, the expansion of the ODA definition risks further marginalizing population assistance (i.e. as a smaller piece of a bigger pie), while it might at the same time provide a more accurate picture of the insufficiency of international funding for SRHR.

Incentivizing the use of ODA loans

ODA growth between 2012 and 2013 was largely due to a 33% increase in development loans and other non-grant ODA.Citation22 However, when it comes to “concessionality”, DAC donors previously had no commonly agreed definition. In practice, this led to different ODA reporting practices by different donors and compromised DAC statistics. France, Germany and the EU – the main providers of ODA loans – submit data that would fail stricter tests of concessionality.Citation23

Against this background, the DAC agreed in 2014 on a common formula to define when lending terms are concessional enough to be reported as ODA, and to ensure that development loans are recognized – and incentivized – as contributing to international development. This outcome of a politically charged debate among DAC members and experts, while appearing profoundly technical, is highly relevant for the quality of future ODA commitments, such as the international 0.7% of Gross National Income (GNI) target.

Under the new reporting system, grants will receive greater “ODA credit” than loans, while more concessional loans will earn greater ODA credit than less concessional loans. While in principle this recognition of the value of grant aid and loans issued at concessional terms, it could have an adverse effect and in fact incentivize non-ODA loans under the new system.Citation24 Donors will no longer be attributed as much ODA from loans as before, but they will be recognized for the total gross value of development flows under the TOSD measure. Especially with regard to the introduction of a potential TOSD target, e.g. 1% of GNI, this could be to the detriment of concessional ODA investments.

Moreover, the DAC plans to base loan concessionality on differentiated discount rates: taking the IMF discount rate (currently 5%) as a base factor, different adjustment factors will be used depending on the relative wealth of borrowing developing countries, namely 1% for upper-middle-income countries, 2% for lower-middle-income countries and 4% for least developed countries and other low-income countries. While loans currently only constitute 5% of total ODA allocated by DAC donors to LDCs and other LICs,Citation25 the DAC expects that this new system, combined with the grant equivalent method described above, will encourage the use of more lending on highly concessional terms to the world’s poorest countries.Citation9

In 2011, around half of ODA loans were specifically allocated to productive sectors that offer high economic returns, while only 30% went to support social sectors such as health.Citation26 When it comes to SRHR, both the measurement of non-grant loans within overall TOSD and the redefinition of the loan reporting framework may be of great concern for SRHR financing as donor funding priorities might shift further away from the social, non-productive sectors – including in the world’s poorest countries where basic health systems, including SRHR services, continue to be chronically underfunded.

World Bank loans reported to the DAC under population assistance sector coding frequently indicate coverage of recurrent, operational (“current”) costs, in direct conflict with generally accepted public sector financial management guidelines,Citation8 which recommend loans for expenses whose value lasts longer than one year – such as buildings and equipment – rather than expenses that recur each year as part of normal operations. Based on the highly limited evidence available in the DAC database, loans that have been disbursed for population assistance almost always include a significant service delivery or information-education-communications component, which typically recur every year as part of the ongoing effort to improve access.Citation8 The issue of what types of projects and expenses are funded through loans rather than grants, and what loan information gets reported, clearly merits better transparency, standardization and centralization.

It is important to remember that public debt is repaid by domestic revenue generation. Using debt financing to fund recurring SRHR operational costs risks increasing the burden on the world’s poorest consumers, who already pay a disproportionate amount out of pocket for these costs. By charging interest and other repayment fees, it increases the total cost of SRHR. Debt financing feeds a vicious cycle, preventing governments from escaping the poor economic performance that makes it difficult to find the needed domestic revenue required to fund these services without external assistance.

Refocusing ODA where it is needed most

The DAC measurement system does not direct geographic donor investments in development cooperation. However, by defining what counts towards international donors’ global commitments for FfD and ODA, it affects donor sustainable development goal financing incentives.

The DAC has outlined four collective measures to improve the targeting of aid to countries most in need Citation27:

| • | reverse the trend of declining aid to least developed countries (LDCs) and reaffirm the target of 0.15%–0.20% of GNI as ODA for LDCs; | ||||

| • | enhance the monitoring and visibility of members’ performance in supporting countries most in need; | ||||

| • | ensure more analysis to identify countries where ODA is most needed; and | ||||

| • | monitor the impact of different channels, instruments and modalities in various contexts and for different purposes across countries, including in countries most in need, to promote ODA. | ||||

Currently ODA constitutes more than two-thirds of all international flows to LDCs. The poorest beneficiary countries continue to depend heavily on ODA for investments in basic services and infrastructures. Yet, since 2010, LDCs have received less aid, while ODA to middle-income countries (MICs) has increased,Citation28 not least due the increasing share of loans. As a result ODA per person is less in LDCs than it is in MICs,Citation29 while the needs are significantly higher (when assessing national or regional level data). UN data from 2013 indicate that the maternal mortality ratio in least developed countries (average 440, up to 1100 in Sierra Leone) is almost double than that in middle-income countries (230).Citation30

The DAC initiative to focus aid on LDCs is commendable; however, the majority of the world’s poor live in MICs, where the disease burdenFootnote§ is now highest.Citation31

| • | Two MICs accounted for roughly one-third of all maternal deaths in 2010 – India (19% of the total or 56,000 deaths) and Nigeria (14% of the total or 40,000 deaths).Citation32 | ||||

| • | Among OECD member states, Mexico has the highest teenage birth rate (64.2 per 1,000 births).Citation33 | ||||

| • | With 50% of MICs deemed fragile, women and girls are at much higher risk, experiencing very poor SRHR outcomes, especially in conflict situations.Citation34 | ||||

Keeping national per capita income as the main criterion for ODA ignores the inequality, health and SRHR challenges poor people face in MICs. Middle-income countries are particularly vulnerable to donor flight, even if they do not have health systems capable of sufficiently addressing SRHR, let alone many other major health problems. Private and domestic resources in MICs are often insufficient, or insufficiently prioritized and directed, to address existing inequality and poverty.

European development NGOs have suggested broadening eligibility beyond growth indicators to include factors such as human development, inequality and vulnerability criteria.Citation35 The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean – covering a region of emerging economies with persisting high levels of inequality – suggests abandoning the GNI per capita measurement altogether in favour of a “structural gap” approach.Citation36 Determining gaps for certain sectors and issues (including health and gender) via a selected set of indicators would better identify the need for in-country investments. The Equitable Access Initiative (EAI)Footnote** focuses on key components of equitable access to health, rather than GNI, to improve data collection and support effective interventions.Citation37,38

Conclusions

We conclude first and foremost that meaningful improvements in global SRHR require that ODA allocations continue to be prioritized and available for poor populations in least developed, low income and middle-income countries.Citation9

The OECD debate on the future of the development finance measurement system may seem highly abstract and removed from practical and pressing SRHR advocacy priorities right now, but this is a high-stakes game that SRHR advocates need to have a hand in. However, the development of the new measurement system for international development finance presents a unique opportunity for the DAC to promote coherence and alignment by non-DAC donors and better capture the “ODA-like” flows in South-South Cooperation under TOSD. As population assistance currently accounts for just over 5% of ODA, DAC measurement of TOSD may show how under-funded activities measured under this sector code are compared to their importance in the Sustainable Development Goals framework.Citation39 The question is whether this opportunity is overwhelmed by the risks associated with incentivizing donors to increase funding through non-grant instruments that have previously been poor means of support for population assistance activities.

DAC tracking of TOSD may incentivize donors to increase funding through non-grant ODA mechanisms, such as loans and market-like instruments. This presents at least two major, distinct challenges:

| • | Much like with TOSD, the broadening of ODA to include funding for climate change and peace and security will further marginalize the percentage of funding going to population assistance. This could lead to a reduced role for SRHR in global discussions and negotiations. As SRHR is subsumed in an increasingly broad ODA discourse and agenda, the burden of increasing and improving sexual and reproductive health as a basic human right may easily disappear under a broader range of competing issues and interests than those focused on poverty reduction. The expansion of “development finance” through TOSD to include for-profit interests will further exacerbate the problem. Other stakeholders that profit from market-like instruments and poor country indebtedness will be better represented and enabled to steer the development discourse away from poverty eradication and towards economic growth. In this context, resources for SRHR representation in the global financing discourse are likely to shrink further. | ||||

| • | We are concerned that an increased use of development financing mechanisms that do not have a primary focus on poverty eradication might shift resources away from under-served populations and poor countries. In this case, the total development effort as measured through TOSD will appear to increase exponentially, but by counting financial flows not targeted exclusively at poverty eradication and those most in need. For the poorest countries, such a dynamic would further exacerbate the macroeconomic poverty trap that prevents them from having functioning health systems. This shift might prove especially problematic for population assistance activities, which are largely recurrent, ongoing operational costs. If donors are incentivized to increase non-grant ODA, especially loans and market-like instruments, in order to demonstrate impressive overall volumes of support for development, these increases could directly conflict with the need for increased population grant aid to support progress on SRHR indicators, including for the poorest and most under-served. | ||||

These challenges present immediate concerns for SRHR advocates, as concretely illustrated by the Global Financing Facility (GFF) for Every Woman Every Child, which will use a combination of grants, loans and other instruments. On the one hand, the GFF and its variety of funding models illustrates the need for the DAC reporting to capture more international public funding then it currently does. GFF design, however, demonstrates that future development finance commitments for population assistance and SRHR may focus more on international loans and domestic resource mobilization rather than on ODA grants.

Finally, the discussion on where to focus ODA geographically will challenge SRHR advocates. With the large majority of poor people living in middle-income countries, with disproportionate health and SRHR outcomes, the upcoming shifts in development financing could well undermine needed funding for SRHR for under-served populations which rely on grants to ensure access. Additional research and analysis is required to allow SRHR advocates to intervene in the discourse about geographic allocations in development finance.

Recommendations for SRHR advocates

This article gives an indication of the many upcoming changes in the field of financing for development and the impact they might have on levels of population assistance. The technicality of these discussions often deters the involvement of SRHR advocates, but the authors hope this article stimulates engagement, as the changes will clearly affect future levels of SRHR support.

As the global political discourse shifts from ODA to TOSD, SRHR advocates will need to be able to justify a seat at the table where the discussion takes place – including at the FfD3 conference in Addis Ababa (July 2015) and beyond. SRHR messaging must be more precisely linked with economic progress and climate. Although not currently recognized as a public good, SRHR is clearly an enabler of progress on global challenges and should be presented as such.

As confirmed by the DAC decision of December 2014, loans will clearly have an important place in financing for development. However, using loans routinely to support the recurring operational costs of SRHR goes against public sector best practice. Unless very carefully crafted and transparently monitored, they could undermine health system strengthening and increase the debt and dependency of poor countries. Advocates need to stress that other mechanisms, most notably grants, are better suited to support sexual and reproductive health and rights.

Regarding future ODA allocations in MICs, the SRHR community should support proposals that emphasize human development and ways to reduce inequality and vulnerability rather than focusing exclusively on national economic development to assess country eligibility. Along with this, SRHR champions need to ensure that universal access to SRHR is included among the sectors and indicators measured to identify gaps to be filled.

Finally, SRHR advocates need to urgently find a way to address the information gap regarding resource flows, which will be worsened by the closure of the UNFPA/NIDI Resource Flows project. Solutions are critically needed to address the challenges and limitations presented by traditional DAC resource tracking for the ICPD costed package, and to establish a much-needed evidence base for SRHR advocates to effectively navigate the new FfD and DAC environment.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Isabelle de Lichtervelde and Marge Berer for their invaluable advice on this article.

Notes

* This article refers to the OECD DAC category “population assistance”, the ICPD costed package tracked by UNFPA / NIDI and the overarching conceptual framework of SRHR.

† The FfD3 Outcome Document refers to the new measure as Total Official Support for Sustainable Development (TOSSD).

‡ National and international DFIs are specialized development banks set up to support private sector development in developing countries, e.g. the African Development Bank and the European Investment Bank, the Netherlands Development Finance Company (FMO) and the German Investment and Development Company (DEG).

§ Measured in Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALY) expressed as the number of years lost due to ill-health, disability or early death. The number of DALYs is highest in MICs.

** Set up by WHO, the World Bank, GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance, UNAIDS, UNICEF, UNDP, UNFPA, UNITAID and the Global Fund for AIDS, TB and Malaria.

References

- Development Initiatives. Investments to End Poverty. Real money, real choices, real lives. 2013. Bristol, United Kingdom.

- UN Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. Proposal of the Open Working Group for Sustainable Development Goals and SG report. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/focussdgs.html

- UNFPA. Financial Resource Flows for Population Activities in 2012. http://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/GPAR%202012%20Sept.pdf. 2014

- UNFPA. Messages and Preliminary Findings From the ICPD Beyond 2014 Global Review. http://icpdbeyond2014.org/uploads/browser/files/initial_findings_of_icpd_beyond_global_survey.pdf, 24 June. 2013

- UN. Report of the Secretary-General: Framework of Actions for the follow-up to the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) Beyond 2014. http://icpdbeyond2014.org/uploads/browser/files/93632_unfpa_eng_web.pdf, 20 January. 2014

- WHO. Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2008. Sixth edition, 2011. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241501118_eng.pdf?ua=1.

- OECD Development Assistance Committee. Factsheet. OECD DAC statistics: a brief introduction. http://www.oecd.org/dac/stats/43544160.pdf, July. 2008

- OECD DAC online database. accessed December 2014http://stats.oecd.org/

- OECD Development Assistance Committee. DAC High Level Meeting Final Communique. 15-16 December 2014. Paris. http://www.oecd.org/dac/OECD%20DAC%20HLM%20Communique.pdf.

- OECD Development Assistance Committee. DAC Senior Level Meeting Report. Measurement of Development Finance Post-2015. 7-8 October 2014. Paris. http://www.oecd.org/dac/SLM-devfinance-consolidated-branded-english_.pdf.

- OECD. Non-DAC Countries and the Debate on Measuring Post-2015 Development Finance. http://www.oecd.org/dac/externalfinancingfordevelopment/documentupload/DCD-DAC%282014%296-ENG.pdf. 2014

- OECD Development Assistance Committee. Background paper: Towards more inclusive measurement and monitoring of development finance – Total Official support for Sustainable Development. DAC High-Level Meeting. Paris. http://www.oecd.org/dac/DACHLM%202014%20Background%20paper%20Towards%20more%20inclusive%20measurement%20and%20monitoring%20of%20development%20finance%20%20Total%20Official%20support%20for%20Sustainable%20Development.pdf. 15-16 December 2014

- Korea International Development Agency. http://www.koica.go.kr/. 2014

- Tracking Chinese Development Finance. http://china.aiddata.org/. 2014

- Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency Turkish Development Assistance. http://www.tika.gov.tr/en. 2012

- Raundi Halvorson-Quevedo, Mariana Mirabile. Guarantees for Development. March. 2014; OECD. http://www.oecd.org/dac/financingforsustainabledevelopment/documentupload/GURANTEES%20report%20FOUR%20PAGER%20Final%2010%20Mar%2014.pdf.

- World Bank. Global Financing Facility in Support of Every Woman Every Child. http://rbfhealth.org/resource/global-financing-facility-support-every-woman-every-child. 09/2014

- UN Secretary General. Global Strategy for Women’s and Children’s Health. September. 2010. New York. http://www.who.int/pmnch/activities/advocacy/fulldocument_globalstrategy/en/.

- A. Harding. The many definitions of public-private partnership in the health sector. Health, Nutrition, population. 29 February, 2012; World Bank.

- S. See Yeung, E. Patouillard, H. Allen. Socially-marketed rapid diagnostic tests and ACT in the private sector: ten years of experience in Cambodia, 2011. Malaria Journal. 10: 2011; 243.

- B. Hayes. The best of both worlds: how public-private partnerships deliver choice. Marie Stopes International News. 25 November. 2014. http://mariestopes.org/news/best-both-worlds-how-public-private-partnerships-deliver-choice.

- Jon Lomøy. Aid only for the neediest? Official development assistance after 2015. OECD Insights. 2014. http://oecdinsights.org/2014/06/17/aid-only-for-the-neediest-official-development-assistance-after-2015/.

- D. Roodman. Straightening the Measuring Stick: A 14-Point Plan for Reforming the Definition of Official Development Assistance (ODA). 2014; Center for Global Development. http://www.cgdev.org/publication/straightening-measuring-stick-14-point-plan-reforming-definition-official-development.

- Assessing the Implications of OECD DAC Proposals for Statistical Reform. Commonwealth Finance Ministers Meetings, Washington, D.C. http://www.oecd.org/dac/Commonwealth%20Finance%20Ministers%20Meeting%20Background%20Document.pdf, 8 October. 2014

- Data for 2012. OECD DAC Table 2a. http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=Table2A

- R. Tew. ODA Loans – Investments to End Poverty. 2013; Development Initiatives: Bristol, UK.

- Communique, DAC High Level Meeting, 15-16 December 2014 OECD, Conference Centre, Paris. http://www.oecd.org/dac/OECD%20DAC%20HLM%20Communique.pdf

- ONE. The 2014 DATA report. http://www.one.org/us/policy/data-report-2014/. 2014

- Manual M. Getting to zero poverty by 2030 – stop giving more to those that need it the least. Development Progress. Blog Post http://www.developmentprogress.org/blog/2014/10/07/getting-zero-poverty-2030-%E2%80%93-stop-giving-more-those-need-it-least.

- UNFPA. State of World Population 2014: The power of 1.8 Billion. 2014; UNFPA: New York.

- A. Glassman. Health Aid eligibility and country income status: a mismatch mishap?. Global Health Policy Blog. 5 May. 2014. http://www.cgdev.org/blog/health-aid-eligibility-and-country-income-status-mismatch-mishap.

- WHO UNICEF UNDP World Bank. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2010. 2012; WHO: Geneva.

- UNFPA. State of World Population 2013: Motherhood in Childhood: Facing the challenge of adolescent pregnancy. 2013; UNFPA: New York.

- OECD. Fragile States Report 2013: Resource Flows and Trends in a Shifting World, DAC International Network on Conflict and Fragility. December. 2012; OECD.

- CONCORD AidWatch. CONCORD AidWatch input OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) senior level meeting on 3-4 March. 2014. Brussels. http://www.concordeurope.org/publications/item/301-concord-aidwatch-input-oecd-s-development-assistance-committee-dac-senior-level-meeting-on-3-4-march.

- UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. Middle-Income Countries: A Structural Gap Approach. November. 2012. Santiago, Chile. http://www.cepal.org/publicaciones/xml/6/48486/Middle-incomeCountries.pdf.

- Updated - Terms of Reference for the Equitable Access Initiative. http://www.theglobalfund.org/documents/eai/EAI_EquitableAccessInitiative_ToRs_en/

- Mark Dybul, Nordstrom Anders. The Changing Landscape and Implications for the Global Fund. Board Retreat, Montreux, Switzerland. 16-18 November 2014

- UN Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform Synthesis Report of the Secretary-General on the Post-2015 Agenda. http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/69/700&Lang=E