Abstract

Abstract

In India, safe abortion services are sought mainly in the private sector for reasons of privacy, confidentiality, and the absence of delays and coercion to use contraception. In recent years, the declining sex ratio has received much attention, and implementation of the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (PCPNDT) Act (2003) has become stringent. However, rather than targeting sex determination, many inspection visits target abortion services. This has led to many private medical practitioners facing negative media publicity, defamation and criminal charges. As a result, they have started turning women away not only in the second trimester but also in the first. Samyak, a Pune-based, non-governmental organization, came across a number of cases of refusal of abortion services during its work and decided to explore the experiences of private medical practitioners with the regulatory mechanisms and what happened to the women. The study showed that as a fallout from the manner of implementation of the PCPNDT Act, safe abortion services were either difficult for women to access or outright denied to them. There is an urgent need to recognize this impact of the current regulatory environment, which is forcing women towards illegal and unsafe abortions.

Résumé

En Inde, les femmes s’adressent principalement au secteur privé pour obtenir un avortement sûr, pour des raisons de protection de la vie privée et de confidentialité, et l’absence de retards et de pressions en faveur de la contraception. Ces dernières années, la baisse du rapport de masculinité a reçu beaucoup d’attention et la loi sur les techniques de diagnostic prénatal et préimplantatoire (2003) a été appliquée strictement. Néanmoins, au lieu de se centrer sur la détermination du sexe, beaucoup de visites d’inspection ciblent les services d’avortement. Il s’ensuit que beaucoup de praticiens privés ont été exposés à une publicité médiatique négative, des diffamations et des poursuites pénales. Ils ont donc commencé à refuser de traiter des femmes pendant le deuxième trimestre, mais aussi pendant le premier. Au cours de son travail, Samyak, organisation non gouvernementale basée à Pune, a eu connaissance de plusieurs cas de refus d’avortement. Elle a examiné l’expérience des praticiens médicaux avec les mécanismes régulateurs et ce qui était arrivé aux femmes. L’étude a montré que, suite à la manière d’appliquer la loi de 2003, l’accès aux services d’avortement sûr était devenu difficile ou même impossible pour les femmes. Il est urgent de reconnaître l’impact de l’environnement régulateur actuel, qui force les femmes à avoir recours à des avortements illégaux et à risque.

Resumen

En India, los servicios de aborto seguro son buscados principalmente en el sector privado por razones de privacidad, confidencialidad y la ausencia de demoras y coacción para usar métodos anticonceptivos. En los últimos años, la decreciente proporción de sexos ha recibido mucha atención, y la aplicación de la Ley de Técnicas Diagnósticas Pre-Concepción y Pre-natales (PCPNDT) (2003) se ha vuelto estricta. Sin embargo, en lugar de enfocarse en la determinación del sexo, muchas visitas de inspección se enfocan en los servicios de aborto. Por consiguiente, muchos profesionales médicos particulares se enfrentan a publicidad negativa, difamación y cargos penales. Como resultado, han empezado a rechazar a las mujeres no solo en el segundo trimestre del embarazo, sino también en el primer trimestre. Samyak, una organización no gubernamental con sede en Pune, se enteró de varios casos de servicios de aborto negado y decidió explorar las experiencias de profesionales médicos particulares con los mecanismos reguladores y lo que les sucedió a las mujeres. El estudio mostró que como secuela de la manera en que la Ley PCPNDT fue aplicada, los servicios de aborto seguro eran difíciles de acceder o eran negados. Existe la necesidad urgente de reconocer este impacto del ambiente regulador actual, el cual está obligando a las mujeres a tener abortos inseguros e ilegales.

India was one of the few countries to legalize abortion as early as 1971 with the passing of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) ActCitation1 by the Indian Parliament. However, legalizing abortion has not translated into safe and affordable abortion services for the vast majority of women in the country. Although all public sector facilities of a certain category are deemed recognized and are supposed to provide MTP services free of cost, the reality is very different. Abortion services have remained predominantly in the private domain, even for women who cannot afford them. With an issue as sensitive and socially stigmatizing as abortion, women choose secrecy over all else. The public sector health centres in most of the states have not yet integrated medical abortion pills within their MTP services and in those that do have the equipment and trained providers for surgical abortion, the services are often made conditional on acceptance of a long term or permanent method of sterilization.

Women’s lack of awareness of the MTP Act, and lack of information about safe, legal services means that they are often late in finding care and come in at later gestations. In the meanwhile, unsafe abortion continues to be among the top five causes of maternal mortality in India.Citation2

The status of women and girls in India has traditionally been seen as secondary to men and boys. The girl child has always been unwanted to some extent, and female infanticide has been a tradition in many communities for hundreds of years. In fact, the Female Infanticide Prevention Act was passed as long ago as 1870 during British rule in India.Citation3 With scientific advances it became progressively easier to identify the sex of the fetus at an early stage through pre-natal diagnostic techniques, and people could now terminate a pregnancy when fetal sex was identified rather than wait for the delivery to eliminate the girl child.

Although the sex ratio in India has been declining since the 1901 census,Citation4,5 it was the mobilization of advocacy efforts by many civil society groups in the 1980s that led to the passing of the Pre-Natal Diagnostic Technique Act in 1994,Citation6 which was later amended in 2003 and renamed the Pre-Conception & Pre-Natal Diagnostic Technique (Prevention and Misuse) Act Citation7. The PCPNDT Act is applicable to radiology (which includes the use of ultrasound), in-vitro fertilization facilities and genetic laboratories.

The MTP and PCPNDT Acts are very distinct in content, addressing two completely different types of facilities with no cross referencing. Despite this, at the implementation level, most authorities tend to conflate the two and speak of “preventing sex selective abortions”.

These two laws are part of a long list of laws directed towards the potential welfare of women and the girl child – such as prevention of child marriage,Footnote* against dowry,Footnote† and equal inheritance rights. However, the lack of rigorous implementation and no strategy to address the deep-seated cultural and social values have resulted in little change in the status quo.Citation8

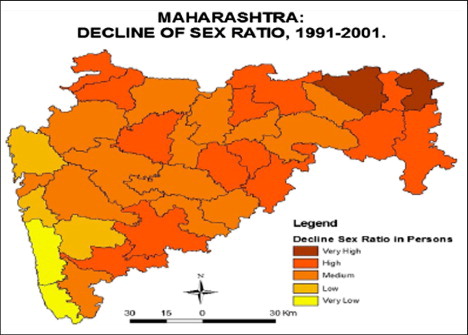

Thus, despite the attempts by government authorities to monitor radiologists and genetic laboratories, the Census of India 2011Citation9 reported a dip in the child sex ratio () in states like Maharashtra between 2001 and 2011 (from 913 down to 894). This alarmed the state health authorities and in response to growing pressure from civil society groups, women’s rights groups and wider media coverage, the government started stringent monitoring of the implementation of the PCPNDT Act in smaller towns in Western Maharashtra, from where most of the “decoy cases” were registered with police. These are usually led by local NGOs and involve a pregnant woman who is used by them as bait to draw out a doctor who agrees to do a sex determination for her.

Figure 1 Maharashtra decline of sex ratio 2001-2011.

Source: Barakade, AJ. Declining sex ratio: an analysis with special references to Maharashtra State.

In 2012, the Maharashtra government sent a proposal to the Centre to treat sex selective abortions as murder and make the act a punishable offence with life imprisonment.Citation10 Other statements from health ministers have been about restricting access to 12 weeks of pregnancy.Citation11 Moreover, the State Food and Drugs Administration recently clamped down on sales of medical abortion pills, ostensibly since they were being used for sex selection, but which has resulted in all chemists refusing to stock the pills any more.Citation12 All of this has created an undercurrent of anti-abortion sentiment.Citation13

During the course of their work in rural areas of Western Maharashtra, SAMYAK, a Pune-based, non-government organization that promotes gender equality and advocates for human rights, found cases of private medical practitioners denying safe abortion services to women, claiming legal concerns.

“It does not make any difference to my practice if I say no to provide an abortion, but it makes a great difference to my practice if I do an abortion and it turns out to be a female fetus. PCPNDT machinery wants us to report every single abortion and its result. So I asked the family to get a permission letter from Taluka (Block) Medical Officer, which he refused to provide, so I denied abortion service to this woman.” (Respondent)

More such stories were reported in SAMYAK’s interaction with communities in the semi-urban areas, and we suspected that many more such stories existed. Hence, we decided to explore the interactions of private medical practitioners with the regulatory machinery and the specific reasons behind their refusal to provide abortion services.

Methodology

SAMYAK planned an exploratory study to document the knowledge and perspectives of private practitioners regarding the relevant laws and their interactions and experiences with the PCPNDT regulatory authorities and persons responsible for on the ground implementation. The study, being exploratory, involved a purposive and small sample of service providers in four districts of Western Maharashtra. The four districts were identified on the basis of low or declining child sex ratio in three consecutive Census of India reports. The sex ratio in these districts averaged 933 (range 924-941) in 1991, 865 (range 839-895) in 2001, and 864 (range 845-880) in 2011.

Within each district, the blockCitation14,15 with the lowest sex ratio was selected. In the selected block, one town was selected based on information about use of abortion services (either observed or provided by the municipal councils).

Many studies, including the recent National Family Health Survey (NFHS) III, show that the private medical sector remains the primary source of health care for the majority of households in urban (70%) as well as rural areas (63%).Citation16

An exercise was undertaken to map the registered private medical practitioners who are authorized to provide abortion services. About 10% of these medical practitioners, or at least five of them (whichever was more), constituted the sample for in-depth interviews. Informed consent was sought from the selected private medical practitioners, and interviews were conducted with those who agreed to participate in the study.

The study was conducted in four selected blocks of the four identified districts of Western Maharashtra. A total of 19 gynaecologists (about five per block) were interviewed.

Detailed interview notes and audio recordings of interviews were transcribed into Marathi, the local language. The transcripts were then coded and analysed according to the objectives of the study.

During the mapping exercise, we approached 34 private medical practitioners through phone calls; 29 of them agreed to be part of the study. However, during the data collection, ten refused, some even after giving appointments. The reasons given ranged from fear of reprisal from the government authorities, high workload or influence of their colleagues, who advised them to refuse. In themselves, these were signs of something going very wrong. Finally, we were able to interview 19 respondents from four selected towns.

Findings

All 19 private medical practitioners who participated in the study were post-graduates in gynaecology and obstetrics. The majority were over 40 years of age and had more than ten years of clinical experience. Their ages ranged from 34 to 65. Seven of them had more than 20 years of work experience; all the others had 5–20 years of experience. Twelve were male and seven female.

Knowledge and views on the MTP Act

All the respondents said that information on the MTP Act was included in their undergraduate and post-graduate curriculum. Fifteen of the 19 were aware of the year in which the MTP legislation was enacted and the conditions stipulated for provision of abortion services.Footnote‡ However, they did not have adequate knowledge of the history and origins of the Act.

Two respondents mistakenly thought the MTP Act had been enacted for the purpose of family planning and population control, and one respondent with 20 years’ practice mistakenly believed the MTP Act had been “converted into the PCPNDT Act in 1994”.

Three respondents raised the issues of compromising confidentiality of patient information under the strict monitoring environment and pressure from the government authorities.

Two respondents mentioned: “It is necessary to keep all the records confidential according to the MTP Act but government authorities ask us about these records when they come to visit and we have to show them whatever they demand.”Footnote§

When specifically asked about their views on the MTP Act, most of the respondents agreed that it is necessary to have the Act in place but a few were of the view that the Act is being “interpreted liberally”.

“Majority of pregnancies are unwanted pregnancies and we don’t have permission to abort unwanted pregnancies. So these abortions are recorded under the criteria of failure of contraception. This is a big contradiction because the government shows success of use of contraception as 99% and here we see 99% of abortions being listed under the criterion of contraception failure.” (Respondent, 30 years’ practice)

All of them were aware of the formalities to be completed as per the MTP Act in terms of the consent forms and records and reports.

“We have to submit a monthly record of MTPs conducted in the hospital. Keeping records of case papers and consent forms is necessary for us. We submit all these documents to the Civil Surgeon at the end of the month.” (Respondent, 40 years’ practice)

“All these documents are secret and we are not allowed to show them any one, not even government people. We keep a record of all cases in an MTP register, in which we include a serial number, name, name of husband or father, reason for MTP, day of admission and discharge… When submitting this register, we remove the name of the patient…” (Respondent, 4 years’ practice)

“All our patients are coming from rural areas… and are not much bothered about delay in taking a decision. This is an important reason for second trimester abortions. On the other hand, they are not aware of the law.” (Respondent, 15 years’ practice)

Knowledge and views on the PCPNDT Act

Since most of these respondents had completed their post-graduate studies before 1994, before the PCPNDT Act had been enacted, it was not part of their curriculum. They had obtained information about the Act from the media, meetings of their local professional association, and government publications, circulars and notifications.

All 19 respondents were aware that the PCPNDT Act was enacted to prevent sex determination. They were also aware of the recording and reporting requirements under the Act. They expressed mixed views on the Act and were sceptical about its impact in controlling sex determination. Their views were aptly summarised by one of them with many years of experience:

“The PCPNDT Act was made by people who are sitting in Delhi. They don’t know about the field realities. I don’t think it is possible to identify those who give wrong information to the doctors. Many people have said that this law is very effective, but I don’t think it is. Tell me how many couples are arrested who have demanded sex selection? And who will accept honestly that she/he is doing sex selection? Then what is use of this act? In fact, teri bhi chup meri bhi chup culture (silence of both doctor and regulatory authorities) promotes sex selection. There are many doctors who are still doing sex selection. Government officials know about them but they don't take action against them because they either have government support or have connections with criminals. Some doctors are still doing it openly and no one can go against them. The law is useless in this case.”

This perspective was expressed by 14 respondents. Another aspect on which 11 of the respondents agreed was the increased documentation required of them, due to the focus on record keeping under the Act. They complained about the increased amount of time needed for this.

While one can understand the frustrations of these respondents, who have been working in an environment of a largely unregulated private sector and who have never been expected to do so much mandatory paperwork, it is also true – as one of the respondents stated: “Clerical work does not stop sex selection – we need to have a different mechanism for it.”

They also expressed their frustration at the pressure of the demands from the local community as well.

“This area is very much developed and many people have money in hand, so they are ready to pay anything; they are not bothered about the fees. So the abortion rates are also high in this area. And they openly ask us for sex selection.”

Perspectives on the right to safe abortion

The MTP Act permits pregnancy termination only under certain conditions and while it is quite liberal in its scope, it does not recognize safe abortion as a woman’s right. Thus, it allows abortion if caused by failure of contraception used by a married woman or her husband for the purposes of limiting their family. An unmarried pregnant girl who has not been raped, can only be considered on the ground of risk to mental health.

We asked the respondents for their views on this issue and 14 of the 19 said that unmarried girls should have access to abortion services for an unwanted pregnancy because it is a very sensitive issue and could result in lifelong problems for her. Three of them also said that they did not ask for the consent of parents if the unmarried girl is an adult. They just keep a copy of identity proof, such as a ration card, and provide the abortion.Footnote**

So, while not articulating it specifically as a right for all women, these respondents were in favour of removing barriers to access for unmarried girls as a way of protecting them from social stigma and future difficulties. The mental health risk, however, is open to interpretation by individual doctors. In fact, five of our respondents said they do not provide abortion services in their private practice to unmarried girls because they do not want to create problems for themselves.

“Pregnancy in unmarried girls may be due to certain illegal things. It can create problems for that girl and her family. My opinion is that we should inform the police while dealing with these types of cases because there are chances of medico-legal problems after MTP. So it is better to inform police. I generally do not do MTPs of unmarried girls in my hospital. I advise them I will do it in the institute (privately) because it is easy to deal with these types of cases there. We can also protect the privacy of that patient”. (Respondent, 4 years’ practice)

All but two respondents said that while they provided abortion services in the first trimester unhesitatingly, they strictly avoid these services in the second trimester because of the probability of the woman having undergone sex determination.

“Though I am authorized to do MTP up to 20 weeks in our hospital, still we are not doing abortions after 10 weeks. We make sure that women do not abort at our hospital in the second trimester. Because we don’t know if it is sex selective abortion or not, so it is better to keep ourselves away from it.” (Respondent, 7 years’ practice)

“I don’t do second trimester abortions because record keeping is very difficult and moreover if unluckily the aborted fetus is female, then it will be more problematic. Nowadays it is very easy to catch a gynaecologist for sex determination and sex selective abortions.” (Respondent, 11 years’ practice)

Addressing the issue of access to services, eight respondents said that the government should take responsibility for increasing the number of MTP centres or should train general practitioners to provide these services. They should also ensure abortion services at rural hospitals that are accessible to the poor. This will reduce their need to seek costly abortions in the private sector or resort to unsafe methods.

Sex determination

It is to be expected that in the current legal environment, all but one respondent said they were absolutely against sex determination. However, the rationale was not only the law but also the perceived social impact on the marriages of men and not for the sake of girls or women themselves.

“Now we are witnessing the conditions a state like Haryana is facing. They have to go to Kerala for a bride. If we ignore the continuous declining sex ratio in Maharashtra then after some time we might have to face the same problem. I agree that our culture is male dominant and people want to have baby boys, but at any cost government should not allow sex selective abortions.” (Respondent, 7 years’ practice)

Only one respondent perceived the right of the woman as absolute and not to be influenced by concern for the demographic consequences of sex selection. However, he said: “Sex selection should not be allowed to all. It can have a negative impact on the sex ratio. But my personal opinion is that for a couple who have had three or four daughters, government should give them permission for sex selection for future pregnancies. Karan tyani achya samajala already 4 muli dilya aahet aani tyamule tyana mulga honyacha hakka aahe asa mala vatata (Because they have already given four daughters to our society so they have the right to wish for a boy).”

Despite being almost unanimous in their opposition to the practice of sex determination, some of the respondents still tried to justify it from a cultural and religious perspective.

“Our society is male dominant and there are many rituals that require a male presence. That’s why less importance is given to the girl child. To stop these practices, we need 50 more years. In spite of the implementation of the law some people still force us to do sex determination tests. Yat tumhi docotrana jababdar dharuch naka (In these cases the private medical practitioners should not be blamed) because we are not the ones who promote female feticide, it is society who forces us to do it.” (Respondent, 25 years’ practice)

Only two respondents actually located the issue within the larger paradigm of women’s inequality and why daughters are unwanted, and articulated that dowry was the root cause.

“It should be strictly banned. As per my opinion the person who is doing sex selection or sex selective abortions should be punished with lifelong imprisonment. Also the government is working on short-term impact. They should think about long-term impact and should work for basic equality between men and women. Government should strictly prohibit dowry, which will help to decrease sex selective abortions.” (Respondent, 13 years’ practice)

“Indian culture and society are responsible for the increase in sex selective abortions. The family wants a male child to continue their family and to hand over the property to. That’s why they ask for sex selection. It is impossible to stop sex selective abortion without changing the mindsets of people. Now we are witnessing that one family has had four or five girls, and still they are waiting for a boy.” (Respondent, 20 years’ practice)

Experiences of the PCPNDT Act interface with implementing authorities

All the respondents we interviewed spoke of the difficulties and challenges they faced while attempting to follow the guidelines of the PCPNDT Act. As a sector which has largely been unregulated, they have felt the burden of increased record-keeping as a very time-consuming process. They must personally do the record-keeping themselves, and cannot rely on their clinic staff, in case they make mistakes, since it is the practitioner who is held responsible during inspections by government authorities.

“Filling in 18 columns of F form is very difficult and time-consuming. Government people ask us to maintain records for those who have two or more daughters. They tell us they will find out what these people did after pregnancy. It takes more than three minutes to fill in F form. These minutes should be invested in discussions with patients, which we are not able to do because we have a heavy case load. We deal with more than 40 patients every day. We have to fill these F forms manually and must also submit them online. Many times there are internet problems and the system does not accept these forms… Record-keeping for the PCPNDT Act is very difficult.” (Respondent, 25 years’ practice)

Two respondents held a different view and said that it is not so difficult to keep records. But they did agree that the process was time consuming and that training to do so would be useful. One of them also expressed his scepticism about the validity and therefore the utility of information about the reasons for abortion shared with them by patients:

“Many times patients give us false information. How can we ensure true information from every patient?” (Respondent, 5 years’ practice)

“One referral case came to me with severe bleeding. That woman was registered for antenatal care in government hospital. I did abortion. It was a three months’ pregnancy. When I asked that woman about kids she told me that she has one girl and one boy. But she actually had two girls. After the abortion the government people came to my hospital for inquiry and they troubled me a lot even though the abortion was in the first trimester.” (Respondent, 20 years’ practice)

“When government people come to us, they ask us about the records of women who have two or more girls. That’s it. They don’t want anything else. Some government people are good. But some people don’t even know about the Act. Last time a government person came to my hospital, he asked for my MTP register for checking. In that month I did two second trimester abortions in which sex of the fetus was mentioned. After checking that register he asked me if the other fetuses were male. I felt very sorry for him and I explained to him that the other abortions were first trimester abortions.” (Respondent, 8 years’ practice)

“When government people come to our hospital, they just walk in and don’t even show us their card. How would we know that they are government people? They suddenly come and ask us to show them our records. They don’t even introduce themselves… Generally, it is when they have deadlines that they come for checking and force us to show our records and trouble us. They find many problems in our records and started blackmailing us by saying ‘We will seal your machine and arrest you’, etc. They even ask us for money. Next time, new people come for visit and again they trouble us a lot.” (Respondent, 15 years’ practice)

“…One rape case was admitted to our hospital. The Superintendent of Police came for inquiry and asked us to show the confidential documents of the patient. I told them that it’s not legal if you don’t have authorization. The Superintendent said that if I did not cooperate with then then they would take action against me. But I still said no.” (Respondent, 15 years’ practice)

The doctors’ perception that the PCPNDT Act is used against them

All the respondents had had some negative experiences during their interactions with the PCPNDT Act monitoring authorities at the district level. While all of them said they had been trying hard to maintain the paperwork that is required, they talked about the relatively trivial mistakes which were used by the authorities to warn and intimidate them as well as the inevitable exploitation and corrupt practises that have occurred.

“Government authorities can point to any problem, like the size or colour of font. One time they said the colour of the background was wrong. Also, they caused us trouble for so many mistakes in the forms, such as date, age, etc. which I think are not valid points.” (Respondent, 13 years’ practice)

“One of my colleagues said that the government people had fined him because he wrote ‘Nil’ rather that ‘No’ on one point.” (Respondent, 12 years’ practice)

“They asked us for double the money because we changed the position of our machine. We had given them 10,000 rupees two times. Generally they come with constables, police inspectors and other government members. They treat private medical practitioners like criminals.” (Respondent, 27 years’ practice)

Some of the respondents reported that apprehension over action by the regulatory authorities was resulting in some of their colleagues exhibiting irrational behaviour: “I saw in the cancer hospital a friend was filling in the F form for a male cancer patient. When I asked him why, he told me that it was better than being harassed.”

“…Nowadays it is very easy to accuse a gynaecologist of sex determination and sex selective abortions. I am very conscious of this and that is why I have 11 CCTV cameras in my hospital and in the compound also. Because I don’t know if someone might put a female fetus in the hospital compound. Then it will create problems for me (zakzak nako dokyala).” (Respondent, 11 years’ practice)

Some of the doctors revealed that they were more apprehensive about the Committee visitsFootnote†† than the regular monitoring visits: “Committee visits are frightening. They come with a team, sometimes with media people. In these visits, if they find any error then it will become headline news for the press. It can impact our practice.” (Respondent, 25 years’ practice)

It was revealing that sometimes, when they do try to help the authorities, it can backfire badly, resulting in an atmosphere of mistrust, fear and hostility. One respondent recounted his experience of dealing with a case of sex determination, which he reported to the authorities:

“I told them about a patient who came to me a few days back for sex determination test and gave them contact details of that patient. They called up the local medical officer and told him that I had told them that so-and-so patient was asking for a sex determination test. So he should go and check it. That medical officer went to that patient’s home for enquiry. Next day the relatives of that patient came to my hospital and threatened me… They should have kept my name confidential. Later, I heard that the patient went and got her pregnancy terminated. Then I realized that by giving information to the appropriate authority, I wouldn’t be able to stop an abortion happening, but instead I would be in trouble” (Respondent, 22 years’ practice)

“Yes, it impacts our practice. Whenever they come, we have to stop our all work. Their visits take a minimum two hours, in which we cannot attend to our patients. Also we have to give them every document they ask for. According to the MTP Act, the personal records of patients should not be opened by anyone. But we cannot say no to these people, because we want to continue our practice. I used to record the names of people who were asking for sex determination and inform the Civil Surgeon. But no one has taken any steps against it.” (Respondent, 25 years’ practice)

Three respondents pointed out that it was local politicians and sugarcane factory owners who pressurized them for sex selection. One of them said: “Many people pressurized us for sex selection. Political people also forced us to do it. I can’t tell you the names. But yes, many such people pressurized us for sex determination.”

Refusal of abortion services and the consequences

Respondents reported that their personal experiences and those recounted by others have created a fear of being penalised under the PCPNDT Act for reasons they cannot control. This has made most practitioners refuse abortion services to women. There are rumours of new rules and regulations which are not found in documents but which pervade the atmosphere in their practices. To quote only a few of them:

“This record keeping is a very time-consuming process. I have to spend my time on that. It impacts my practice. I can’t give sufficient time to patients. Also since the last one year I have stopped doing second trimester MTPs because of this record-keeping.”

“Recently, government have announced that we should not use indication of contraception failure for the second trimester abortions as they can be sex selective abortions. It is a protective step taken by the government. So we do not provide abortion service in the second trimester, even if there is any anomaly in the baby.”

“Generally we never do MTPs for referral cases because there might be a chance of sex selective abortions. Also if the patient has one or two daughters then we refuse the abortion.”

The study also found that these fears are leading medical professional organizations in some towns to advise their members to avoid providing terminations, especially in the second trimester.

“In our Association we discussed various issues related to the PCPNDT Act and decided that, if any second trimester MTP cases come to our hospitals we would send them to the president of the association. Our President would look for the reasons for MTP, check their reports and then inform the respective medical officers about them. We ask the patients for a permission letter from the president to perform MTP.”

Some of the respondents have increased their charges for sonography as compensation for the harassment they might face: “Our staff are trained and now we know how to do the documentation, so there is not much trouble from the authorities. But what we have done is we have increased our sonography rates by 100 rupees.”

As gynaecologists they are aware of the implications of denial of services to women and the impact this has on women’s health. One of them said: “After refusal [of abortion] many patients might go to illegal practitioners. In the periphery many BHMS, BAMS Footnote‡‡ practitioners are doing illegal abortions. They charge less than us, so patients prefer to go to these hospitals, but many times it creates problems, such as septic abortions. Also there are many patients who are forced to continue the pregnancy even though it is unwanted.”

“Average 30 abortions cases I used to deal with every month. Now from last year we have stopped doing second trimester abortions, so the abortion cases are decreased. I am new in this town and have much less experience of working here. So I cannot tell you about any change in pattern of cases. But I know one thing for sure, that many doctors are not doing abortion services right now.” (Respondent, 6 years’ practice)

We did not ask for specific data on the exact decline in the numbers of services but one doctor said that he was refusing at least two such cases per day. Many of them reported that they had reduced the number of abortion services because of the burden of clerical work and the fear of PCPNDT authorities.

“Government people troubled us for various reasons. They even said ‘You are lying; you must be doing sex selection.’ This is very disturbing for us. That’s why I stopped doing MTPs in the second trimester.” (Respondent, 20 years’ practice)

Most of the respondents reported that if a woman has even one daughter, they refuse to perform the abortion.

Discussion and conclusions

While the role that radiologists, genetic laboratories and gynaecologists have played in recent decades in facilitating sex determination and sex selection through abortion cannot be ignored, the reality of the barriers to obtain safe, legal abortion services in India are many.

The vigorous implementation of the PCPNDT Act in the absence of a larger policy environment that recognizes gender discrimination as the root cause of sex determination, has meant that it is the safe abortion services that come under fire. It is the sex determination which is illegal and a woman who finds out that she has a male fetus and goes home to deliver a boy is as guilty of having broken the law but somehow the implementation and the language (‘female feticide’) has tended to conflate this issue with abortion access. It is therefore ironic that the PCPNDT Act, which emerged from the women’s rights movement (unlike the MTP Act), has ended up hurting the interests of women due to misdirected zeal in implementation.

Private medical services have been and continue to be largely unregulated in India. Citation17 While most private medical practitioners have interacted with the authorities to register their nursing homes and get approvals, they have never been subjected to such draconian, public, often hostile monitoring by non-medical personnel. Private medical practitioners who have been practising without any regulation before the enactment of the PCPNDT Act, are now forced to be accountable to officials who are mostly not doctors. This adds another dimension to the interaction dynamics, and while one does not recommend that the regulations be reduced, it is short-sighted to expect reform to take place through only one Act addressing only one service while everything else continues as it is.

Our study uncovered a scenario in which private medical practitioners were resentful of being harassed for clerical errors; they wanted their dignity as professionals to be respected. On 15 April 2015, thousands of radiologists went on strike in India to protest criminal action being taken against their numbers under the PCPNDT Act 1994. The radiologists said the PCPNDT Act had become "draconian for all practising sonologists and radiologists" instead of serving the purpose of ‘saving the girl child’. They alleged that the Act had become "a harassing tool" in the hands of the authorities implementing it. They also echoed the views of many of our respondents and said that “This Act has failed to yield any result for the past two decades. So, the actual reasons for deteriorating sex ratio should be analysed and corrective action taken”.Citation18

We learned that women’s right to confidentiality under the MTP Act was not respected under the PCPNDT Act by the monitoring authorities, thus making the atmosphere hostile. Due to the fear of PCPNDT authorities, many private medical practitioners are refusing to provide abortion services, especially second trimester abortions. The main reason they gave for this was to protect themselves from harassment and criminal prosecution. There are also numerous instances where private medical practitioners have denied abortions to unmarried girls, single women and for pregnancies caused by rape for fear of any enquiry jeopardising their practice, even though quite clearly these women are not likely to have carried out sex determination or wanted an abortion for this reason.Citation19

In a society where girl children continue to be abandoned after being born,Citation20,21 paperwork will not encourage non-discrimination and a tunnel vision approach to punishing practitioners will not succeed in resolving the social dimensions of this issue. The daily news of violence and discrimination against women, the reality of lack of basic amenities, school education, secure employment, adequate food and medical care during sickness – worse for girls than for boys – are a stark reminder of the lack of value of the girl child in our society. Historical evidence of discrimination against the girl child, the patriarchal mind-set regarding the role of women and girls, poor implementation of other laws such as preventing child marriages and payment of dowry, the role of technology, misdirected campaigns, going for easy targets over making deeper changes, selective regulation of the private medical sector and lack of options within the public sector – all these further reduce spaces for women’s health rights and access to services.

Private medical providers’ opinions often echo the unfortunate ways in which the campaigns and rhetoric against sex determination have reinforced stereotypes of women as wives and mothers only, and project the horrors of sex selection as being its impact on maintaining the existing patriarchal structures. Rather than recognize requests for sex determination and abortion of female fetuses as a marker of gender discrimination and the status of women in the country, a misdirected connection is repeatedly made with access to safe abortion services, especially those obtained in the second trimester.

Undoubtedly there are medical practitioners who continue and will continue to provide these practices, but it would be for the greater good for the government to work with them and their professional bodies, not against them. Government authorities also have to be made aware that rather than acting on suspicion or assuming guilt, they need to review and access only those documents that fall within the purview of the PCPNDT Act, not encourage media publicity, and not visit the clinic accompanied by the police before obtaining any clear evidence of criminal activity. It is also necessary to train private medical practitioners in different aspects of the law so that they can deal effectively with the authorities and be able to defend the confidentiality of the women as enshrined in the MTP Act. The medical associations should engage themselves in this endeavour. This will reduce fear among these providers and make their refusal to provide safe abortion services unnecessary, thus serving the best interests of women. Professional bodies need to also move their initiatives beyond documents, statements and trainings and take action against errant colleagues.

The time has come to move away from quick fixes and rhetoric about “save the girl child” and recognize the need to approach the issue from multiple levels. Positive reforms, interventions and implementation are what will make a difference. While Acts such as the PCPNDT Act should be implemented, so should the MTP Act, as well as laws against dowry, to prevent child marriage, to provide education and employment for girls and women, and ensure equal inheritance, paid maternity leave and so many others to ensure that all factors determining girls’ and women’s welfare are addressed in a holistic and comprehensive manner.

Notes

* The Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006. http://wcd.nic.in/cma2006.pdf.

† The Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961. http://wcd.nic.in/dowryprohibitionact.htm.

‡ To save the life of the pregnant woman, to prevent grave injury to the physical and mental health of the pregnant woman, to prevent the birth of a seriously handicapped child and in case of pregnancy resulting from rape or failure of contraception.

§ As per the MTP Act regulations, only a court can order that these records to be shared. The PCPNDT implementation officers have no authority to ask for MTP documents, since the PCPNDT Act deals only with sex determination.

** This is not required by the Act and is an example of extra barriers/conditions doctors are creating in order to protect themselves. A young unmarried girl is unlikely to have the ration card to hand; it is given to a family as a whole, not to individuals, for subsidized food rations. And if the girl does not go to college, she will have no college ID either.

†† A team of legal advisors, the Medical Superintendent and NGO members who are on the advisory committee of the PCPNDT Act.

‡‡ Bachelor of Homeopathy Sciences, Bachelor of Ayurveda Medicine and Surgery are the other approved medical streams besides allopathy (MBBS) in India.

References

- Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971. http://tcw.nic.in/Acts/MTP-Act-1971.pdf

- Center for Reproductive Rights. Maternal Mortality in India Using International and Constitutional Law to Promote Accountability and Change. 2008; CRR: New York. (http://www.unfpa.org/sowmy/resources/docs/library/R414_CenterRepRights_2008_INDIA_Maternal_Mortality_in_India_Center_for_Huiman_Rights.pdf).

- Female Infanticide Prevention Act, 1970. http://www.sja.gos.pk/Statutes/Criminal%20minor%20acts/Female%20Infanticide%20Prevention%20Act%201870.html

- K. Pakrasi, A. Ajit Halder. Sex ratios and sex sequences of births in India. Journal of Biosocial Science. 3(4): 1971; 377–387. Published online on 31st July 2008.

- Trends in India’s sex ratio science 1901-2001. http://www.infochangeindia.org/women/statistics/trend-in-indias-sex-ratio-since-1901-2001.html

- Pre-Conception Pre-Natal Act Diagnostic Techniques Act, 1994. http://www.maha-arogya.gov.in/actsrules/default.html

- India. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Handbook on Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques Act and Rules with Amendments. 2006

- Inheritance rights for women: a response to some commonly expressed fears. http://www.manushi-india.org/pdfs_issues/articles/Inheritance%20Rights%20for%20Women.pdf

- Census of India 2011. http://censusindia.gov.in/Census_And_You/gender_composition.aspx

- Maharashtra for treating sex selective abortions as murder. Indian Express, 28 August 2012. http://archive.indianexpress.com/news/maharashtra-for-treating-sex-selective-abortions-as-murder/994396/

- State plans 10-week abortion limit for contraceptive failure cases Times of India, 25th June 2011. http://epaper.timesofindia.com/Default/Scripting/ArticleWin.asp?From=Archive&Skin=TOINEW&BaseHref=TOIM%2F2011%2F06%2F25&EntityId=Ar00105&AppName=1&ViewMode=HTML

- M. Iyer. State driving abortion pills out of market. Times of India. 25 April 2013. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/mumbai/State-driving-abortion-pills-out-of-market/articleshow/19718182.cms

- Crackdown on female foeticide in Maharashtra creates shortage of abortion pills. Economic Times, 7 September 2014. http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2012-09-07/news/33677400_1_mtp-drugs-surgical-abortions-termination-of-pregnancy-kits

- Government of Maharashtra State Welfare Department. (Marathi). 2005

- Census of India 2001. http://censusindia.gov.in/Census; You/gendercomposition.aspx

- P.H. Rao. The private health sector in India: a framework for improving the quality of care. ASCI Journal of Management. 41(2): 2012; 14–39.

- A. Jesani. The unregulated private health sector. CEHAT. http://www.cehat.org/publications/pb05a24.html

- Feature: Sonologists, radiologists and gynaecologists in India on strike, 15 April 2015. http://sxpolitics.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/FEATURE-Sonologists-in-India-go-on-strike-15-April-2015.pdf

- https://in.news.yahoo.com/if-you-re-in-your-second-trimester-and-want-to-get-an-abortion-in-maharashtra--good-luck-060713360.html

- 90% of 11m abandoned kids are girls. TNN. (22 April 2011)http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/90-of-11m-abandoned-kids-are-girls/articleshow/8052318.cms

- R. Mohanty. Trash bin babies: India's female infanticide crisis. http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2012/05/trash-bin-babies-indias-female-infanticide-crisis/257672/