Abstract

Abstract

This paper describes the implementation of five Safe Abortion Information Hotlines (SAIH), a strategy developed by feminist collectives in a growing number of countries where abortion is legally restricted and unsafe. These hotlines have a range of goals and take different forms, but they all offer information by telephone to women about how to terminate a pregnancy using misoprostol. The paper is based on a qualitative study carried out in 2012-2014 of the structure, goals and experiences of hotlines in five Latin American countries: Argentina, Chile, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela. The methodology included participatory observation of activities of the SAIH, and in-depth interviews with feminist activists who offer these services and with 14 women who used information provided by these hotlines to induce their own abortions. The findings are also based on a review of materials obtained from the five hotline collectives involved: documents and reports, social media posts, and details of public demonstrations and statements. These hotlines have had a positive impact on access to safe abortions for women whom they help. Providing these services requires knowledge and information skills, but little infrastructure. They have the potential to reduce the risk to women’s health and lives of unsafe abortion, and should be promoted as part of public health policy, not only in Latin America but also other countries. Additionally, they promote women’s autonomy and right to decide whether to continue or terminate a pregnancy.

Résumé

Cet article décrit la mise en łuvre de cinq lignes d’information sur l’avortement sûr, une stratégie élaborée par des collectifs féministes dans un nombre croissant de pays où l’avortement est restreint par la loi et à risque. Ces lignes ont un éventail d’objectifs et prennent différentes formes, mais toutes renseignent les femmes par téléphone sur la manière d’interrompre une grossesse avec le misoprostol. L’article est fondé sur une étude qualitative réalisée en 2012-2014 sur la structure, les objectifs et les expériences des centrales d’appel dans cinq pays latino-américains: Argentine, Chili, Équateur, Pérou et Venezuela. La méthodologie incluait l’observation participative des activités des lignes d’informations ainsi que des entretiens approfondis avec des militantes féministes qui offraient ces services et avec 14 femmes qui avaient utilisé les informations fournies par ces lignes pour provoquer leur avortement. Les conclusions sont aussi fondées sur un examen des matériels obtenus des cinq collectifs concernés : documents et rapports, messages sur les médias sociaux et détails des manifestations et déclarations publiques. Ces lignes téléphoniques ont un impact positif sur l’accès à un avortement sûr pour les femmes qu’elles aident. Assurer ces services exige des connaissances et des compétences en information, mais peu d’infrastructures. Les lignes ont le potentiel de réduire la menace que l’avortement à risque fait peser sur la santé et la vie des femmes, et devraient être promues dans le cadre de la politique de santé publique, non seulement en Amérique latine, mais aussi dans d’autres pays. De plus, elles favorisent l’autonomie des femmes et leur droit à décider de continuer ou d’interrompre une grossesse.

Resumen

Este artículo describe la aplicación de cinco Líneas de Información sobre Aborto Seguro, una estrategia formulada por colectivos feministas en un creciente número de países donde el aborto es inseguro y restringido por la ley. Estas líneas de atención telefónica tienen una variedad de metas y asumen diferentes formas, pero todas ofrecen información por teléfono a mujeres sobre cómo interrumpir un embarazo utilizando misoprostol. El artículo se basa en un estudio cualitativo llevado a cabo en 2012-2014 sobre la estructura, metas y experiencias de líneas de atención telefónica en cinco países latinoamericanos: Argentina, Chile, Ecuador, Perú y Venezuela. La metodología incluyó la observación participativa de las actividades de las SAIH y entrevistas a profundidad con activistas feministas que ofrecen estos servicios y con 14 mujeres que utilizaron la información proporcionada por estas líneas de atención telefónica para inducir sus abortos. Los hallazgos también se basan en una revisión de materiales obtenidos de los cinco colectivos participantes: documentos e informes, comentarios publicados en los medios sociales de comunicación y detalles sobre manifestaciones y declaraciones públicas. Estas líneas de atención telefónica han tenido un impacto positivo en el acceso a los servicios de aborto seguro para las mujeres a quienes ayudan. La prestación de estos servicios requiere conocimientos y habilidades de información, pero poca infraestructura. Tienen el potencial de reducir el riesgo del aborto inseguro para la salud y vida de las mujeres, y deben ser promovidos como parte de la política de salud pública, no sólo en Latinoamérica sino también en otros países. Además, promueven la autonomía de las mujeres y su derecho a decidir si continuar o interrumpir un embarazo.

The demand for the decriminalization of abortion is getting more and more priority in the agendas of feminist organizations in Latin America and the Caribbean. As part of this action, feminist collectives in a number of countries in the region where abortion is legally restricted and unsafe have begun to implement Safe Abortion Information Hotlines” (SAIHs). This is an information service whose purpose is to promote access to safe abortions,Citation1 offering women information by telephone about how to terminate a pregnancy using misoprostol, a prostaglandin abortifacient medication in pill form, which is on the Essential Medicines List of the World Health Organization. This paper describes and analyzes the work and experiences of hotlines in five Latin American countries – Argentina, Chile, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela – where there are legal restrictions on access to safe abortions.

Methodology

This was a qualitative study, which consisted of participatory observation in various activities organized by three of these groups and in-depth interviews with ten women activists who participate as volunteers in providing this service for the five hotlines, identified through snowball sampling. I also interviewed 14 women who requested information from one of the SAIHs by telephone and later had an abortion using misoprostol. The women who used the hotlines’ services gave informed consent for the interview, the recording and the publication of the results of the research. The National Clinical Hospital Ethics Committee in Córdoba, Argentina, approved the research with the women who used misoprostol. The findings are also based on a review of materials obtained from the five hotline collectives involved: documents and reports, social media posts, and details of public demonstrations and statements.

The main aim of the research was to describe the potential of safe abortion information hotlines for reducing the risks of unsafe abortion for women who live in legally restrictive contexts in Latin America.

The global impact of unsafe abortion

In the developing world, 56% of abortions are unsafe. In the developed world, in contrast, only 6% of abortions are unsafe.Citation2 Globally, 40% of women of reproductive age live in countries with highly restrictive laws in which abortion is completely prohibited or allowed only to save the life of the woman or protect her physical or mental health.Citation3 In Chile, El Salvador, Honduras, Dominican Republic, Nicaragua and Surinam, all abortions are criminalized. On the other hand, in Mexico City, Uruguay, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guyana, and French Guyana, abortion is legal when it is carried out before the 12th or 14th week of pregnancy. In the rest of the countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, the “indications model” is applied, which allows for abortion on certain grounds,Citation4 such as risk to the life or health of the woman, non-viability of the fetus outside the uterus, and/or when the pregnancy is the result of rape or sexual abuse.

The main problem in countries with restrictive laws on abortion is that women with few resources resort to untrained abortion providers or induce an abortion themselves with unsafe methods. In these cases, there is a high risk of incomplete abortion, infection, uterine perforation, pelvic inflammatory disease, haemorrhage or other injury to internal organs that can lead to death, permanent morbidity and/or infertility. This makes it important for women to be able to receive adequate post-abortion care for such complications, which can help to reduce the morbidity and mortality from unsafe abortion if accessible in a timely manner.Citation5 Studies carried out in Latin AmericaCitation6 indicate that the increase in the self-use of misoprostol for medical abortion is related to a decrease in serious complications and maternal mortality and morbidity caused by unsafe abortions with other methods. This article shows how Safe Abortion Information Hotlines are one means of allowing women to obtain reliable information about medical abortion.

Medical abortion in legally restrictive contexts

The penalization and criminalization of abortion is not actually associated with lower rates of abortion.Citation2 They do not discourage women in their search for an abortion, but they do increase the risks to their health and lives. In the clandestine context of restrictive laws, one of the options that has gained traction in recent decades is the use of medical abortions.Footnote* Medical abortion using a combination of mifepristone and misoprostol as per WHO guidance has a similar safety and efficacy profile as surgical or aspirations abortion in the first trimester of pregnancy.Citation7 In countries where abortion is legally restricted, however, mifepristone has not been approved because its only indication is for inducing abortion.

Where mifepristone has not been approved, including in Latin America, medical abortion is carried out using the drug misoprostol, an E1 prostaglandin analog that has been available in pharmacies in Latin America since the late 1980s, under the trade name Cytotec, as a medication for treating gastric ulcers. Misoprostol causes uterine contractions, which causes the detachment of tissue formed within the uterus in pregnancy, similar to what happens with a spontaneous abortion or miscarriage. The expulsion of the contents of the uterus with misoprostol alone occurs in 80-85% of cases.Citation8 The most frequent form of use is by placing the pills in the vagina, or in the mouth sublingually or buccally, using a dosage that is related to the number of weeks of pregnancy from the last menstrual period.Citation9 Footnote†

Beginning in the late 1980s, the use of misoprostol outside of the network and control of health care providers spread rapidly, driven by word of mouth between women who had abortions without complications. Starting in the 1990s, in various Latin American countries misoprostol became one of the most commonly used abortifacients to induce abortionsCitation10 because it allows safe early termination of pregnancy,Citation1 even where there are legal restrictions and in contexts with limited health care resources. This medication allows women to take the simple steps necessary for this procedure.Citation11 The decision to abort with misoprostol can even precede consultation with a doctor.Citation12

In the majority of Latin American countries, women access the medication by buying it in pharmacies with or without a prescription.Citation10,13 Where legal restrictions on pharmacies selling the medication have been imposed, as for example in Brazil, access becomes more difficult, and forces women to buy it on the black market. On the black market, there is a risk of acquiring a product that is more expensive than in pharmacies and that may also be adulterated or ineffective.Citation14,15

Based on exhaustive research, WHO includes misoprostol on its Model List of Essential Medicines for early termination of pregnancy, medical treatment of retained spontaneous abortion, and for inducing labour.Citation16 This means member States should incorporate misoprostol for obstetric use in their health care systems, due to its contribution to reducing maternal morbidity and mortality, which is supported by regional organizations.Citation17

Studies show that in the last decade, in Latin American countries, a relationship exists between access to misoprostol and a reduction in hospital stays for complications of unsafe abortion.Citation6 These studies attribute at least part of the reasons to the wide distribution and popularity that misoprostol has gained,Footnote‡ especially in urban populations.Citation20

Women who support women to have safe abortions

There are historical precedents of feminist groups being involved in helping women to have safe abortions, for example during the second wave of feminism. One of these was in Italy, carried out by a group of leftist, feminist women who formed “Soccorso Rosa” in Rome. This organization established a mutual aid network for carrying out surgical abortions, facilitated by doctors in clandestine locations, and the experience was later replicated in other Italian cities.Citation21 In France, the Mouvement pour la Liberté de l’Avortement et de la Contraception (MLAC) was made up of feminists who in the 1970s created networks across the country that also included committed doctors and facilitated women being able to have safe abortions. They also learned to carry out the abortions themselves. The experience was portrayed in the 1980 documentary “Regarde, elle a les yeux grands ouverts" (Look, she has her eyes wide open), which included an important discussion about the necessity of the group continuing to function even after the legalization of abortion in France, which they helped to bring about.Footnote§ In the United States, women in Chicago organized the “Jane Collective", which operated from 1969-73 providing abortions, first through trusted doctors and later performing the abortions themselves. Their experience was extensively portrayed by Jane members in 1997 and later.Citation22,23

Generally, in those earlier times, in all three countries described, contact was made by telephone or in person. The process involved included offering women information about what they were going to go through and personal accompaniment and emotional support were provided as well at the time of the abortion. The safe abortion methods available were surgical and highly effective. In addition, these collectives sought to respond to most women’s lack of economic resources to pay for an abortion. Historically, as now, money has been an obstacle to accessing safe abortion services, including in clandestine situations.

Abortion with medication had not yet been developed, with its potential for self-inducing a safe, easily accessible, autonomous, and low-cost abortion.

Five Safe Abortion Information Hotlines in Latin America

Telephone hotlines that offer information, counselling, assessment, and help, among other things, are a resource with important precedents. In Latin American countries, governments and various other organizations have implemented telephone counselling services for all kinds of information, advice and consultations: suicide prevention, addiction, HIV and AIDS, sexual and reproductive health, contraception and unplanned pregnancy, violence and sexual violence. Even the church has hotlines, for example, for spiritual accompaniment for married couples in crisis, or for providing “spiritual support” after an abortion.

Similarly, Safe Abortion Information Hotlines are being initiated today with the goal of informing women via telephone about how to have an abortion using misoprostol. They are working in contexts where access to safe abortion services is legally restricted and where stigma, obstetric violence, and so-called “pro-life” pressure groups are also active.Citation24,25,35 These hotlines are the result of initiatives carried out by women’s collectives and are not a part of any health institution. On the contrary, they are independent spaces that provide health information and that challenge the conventional biomedical/clinical structures, and their services are not offered by doctors or men. They favour improvements in women’s “abortion itinerary",Citation10,39 because access to adequate and reliable information gives women the possibility of having an abortion that is safe for their health and lives, in these cases with misoprostol.

The experiences of the Safe Abortion Information Hotlines described here took place in Ecuador, Venezuela, Peru, Chile and Argentina.

Ecuador “Women’s Health Collective – Tel 0998-301317”

In June 2008, the first of these five initiatives in the region was inaugurated in Quito, Ecuador, by the Coordinadora Política Juvenil por la Equidad de Género (CPJ, Youth Political Organization for Gender Equity) as part of the project “Information hotline on sexuality and safe abortion, Women’s Health”.Footnote** This is an organization of young feminists who work to promote, defend, and guarantee the sexual and reproductive rights of women and youth in Ecuador.Citation26 Theirs was the first hotline in the region, and it was created with support from the Dutch organization, Women On Waves (WOW).Footnote††

A central goal of this hotline is to achieve the social and legal decriminalization of abortion. On their blog (which has had approximately 2.5 million visits since its creation in 2008) the activists provide services via chat (since 2013) on pre-established days and hours. It is also possible to contact them by email and leave comments on their posts. According to their report, the most consulted entries are “How to have a safe abortion” and “Frequently asked questions”. One of the least consulted entries is “Birth control methods”.Citation26

In September 2010, the hotline was blocked by a court order, but a new one was inaugurated immediately, which continues operating at present. In this context, blogs and social networks are effective strategies to overcome obstacles and the interventions of conservative groups and to continue providing information.

Recently, they opened a space for personal consultations called Warmikunapa Willachik Wasi, or Women’s Information House, which operates in the city of Quito. They defend the need to demedicalize abortion and promote women's decision-making regarding their bodies soberanía sobre nuestros cuerpos (sovereignty over our bodies). A notable feature of this collective is that they identify fundamentally with youth.

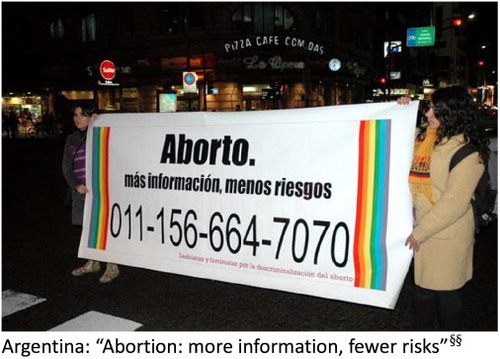

Argentina: “Abortion Hotline: more information, less risks – 011-15-66-64-7070”

In Buenos Aires, the Safe Abortion Information Hotline is part of the project “Abortion: more information, less risks” and has been in operation since 2009, maintained by the collective Lesbianas y Feministas por la Decriminalización del Aborto (Lesbians and Feminists for the Decriminalization of Abortion).Footnote‡‡ The founders decided to distance themselves from the feminism of the majority and their slogans in the fight for legalizing abortion in Argentina. They seek to distance themselves from established ideas like the danger and the deaths associated with clandestine abortion, with the goal of reducing the stigma and the distress it entails. Instead, this group connects the practice of abortion with “pride in aborting” and maintain that “abortion lesbianizes”, establishing what they consider a clear relationship between the practice of abortion and the desire to be a lesbian. Their slogans seek to fight stigma and to problematize an exclusively heterosexist vision of sex.

In March 2010, they presented the first edition of their manual “Everything You Want to Know about How to Abort with Pills”,Citation27 which was downloaded more than 500,000 times and of which 20,000 print copies were distributed free. The updated second edition was published in 2012.

As a result of the systemization of anonymous data collected through the hotline, this group has presented an activities report for each year of its operation. The proposal seeks to bring abortion discourse and practice out of clandestinity. The hotline has presented seven reports, and the most recent report indicates that they received 5,000 calls in one year, of which 80% were from women who live in the Buenos Aires area.Citation28,29

Currently, the hotline provides the services of pre- and post-abortion counselling in Buenos Aires province, a result of the cooperation of activists, health professionals, and the official political sector. This counselling occurs within public health institutions and in the offices of the political party Nuevo Encuentro, allied with the national government (Frente para la Victoria). It is interesting to observe how their actions in practice allow for advances in the promotion of safe abortions, even while the national government does not display the political will to debate a bill to legalize or decriminalize abortion.

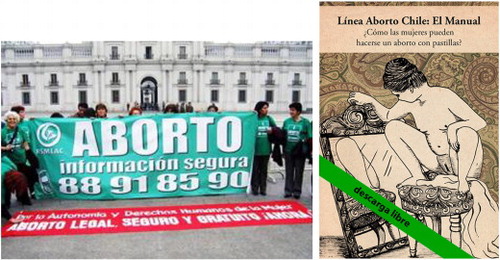

Chile: “Abortion Hotline Chile – 8891-8590” and “Free Abortion Hotline – 7530-7461”

The experience of the “Linea Aborto Libre” (Free Abortion Hotline) in Chile began on the International Day of Action for Women’s Health 28 May in 2009. The hotline was created by the group Bio Bio Feminists and is currently maintained by the Colectivo Lesbianas y Feministas. The initiative is multiplying and their experience is being shared and developed in different cities in Chile. They operate in Santiago and Iquique (since 2013) and in Concepción (Abortion Hotline Chile, since 2009) and they maintain constant activity on Facebook and Twitter.

The connection with a lesbian identity, "love between women" and "lesbian feminism", characterizes this collective, which happens with other Latin American groups as well. Their political objective aims at promoting lesbianism as non-reproductive sexual practice and a contraceptive methodCitation30 and criticizes heteronormativity, patriarchy, and obligatory maternity.

It is important to point out that, in Chile, the service operates in a context where all abortions are illegal ever since the last year of the Pinochet dictatorship in 1989, and the possibility of a therapeutic abortion does not exist. Early this year, President Michele Bachelet sent a bill to Congress that would decriminalize abortion in three circumstances. However, the hotline activists do not look favourably on this bill, as most abortions would continue to be a crime.

The hotline in Concepción has answered more than 20,000 calls since 2009. The data collected indicates that the greatest obstacle is obtaining misoprostol, and that 90% of women buy it online on the black market. They published Línea Aborto Chile: El Manual (Abortion Hotline Chile: The Manual),Citation30 which on sale in bookstores and downloadable from their blog.Footnote***

These groups carried out many public interventions for the decriminalization of abortion and other activities, such as a national mobilization under the slogan “Without doctors or police, our abortions are happiness” and hold workshops on self-inducing abortion in various cities in Chile. They have also presented information and data about the hotline in academic conferences.Citation31 Through the creation of a feminist publishing house, they offer Spanish editions of classic works of feminist and abortion rights activism. They also have centres operating in Santiago and Iquique.

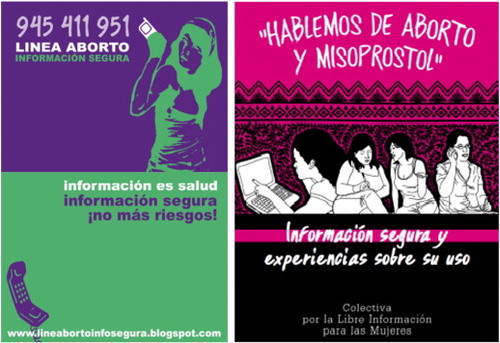

Peru: “Dependable Information Abortion Hotline – 945-411-951”

The group in Lima, Peru, also received initial support from Women on Waves. It began in May 2010 with the project “Abortion: dependable information”, carried out by the feminist organization Colectiva por la Libre Información para las Mujeres (CLIM, Collective for Free Information for Women), made up of women, men, and sexual dissidents. Although they have a blog,Footnote††† the information is provided exclusively by phone, although lately there have been interruptions in the service.Footnote‡‡‡

In October 2011, the hotline published its first annual reportCitation32, and in 2014 they published the manual Hablemos de aborto y misoprostol (Let’s talk about abortion and misoprostol).Citation33 This document, like those of other hotlines, provides the protocol for using misoprostol through simple information, with illustrations to facilitate understanding. It also contains political messages about women’s right to decide whether to have an abortion or not.

In Peru, especially in Lima, it is common to encounter advertisements in the street for clandestine abortion services, which offer to solve the problem of “delayed menstruation”. The project that this hotline promotes, in contrast, is the option of a safe, autonomous abortion using misoprostol.

Venezuela: “Abortion Hotline, Dependable Information – 0426-1169496”

In Caracas, Venezuela, this hotline has operated since 2011, sustained by the collective Feministas en Acción Libre y Directa por el Aborto Seguro en Revolución (Feminists in Free and Direct Action for Safe Abortions in Revolution). Its founders have been closely identified with the socialist government of Hugo Chavez and the current president, Nicolas Maduro. However, neither of these leaders has promoted the decriminalization of abortion. This is an example of the complex relations between some Latin American women’s movements and Left or Center-Left governments in the region. In consonance with its adherence to socialism, the organization demands an end to the clandestine market and that the state take responsibility for women’s health.

This collective also promotes the decriminalization of abortion and access to misoprostol. They are active on Facebook and Twitter and have a blog,Footnote§§§ and they offer information on having a safe and demedicalized abortion. From their beginnings, the organization has shown great concern for the incorrect use of misoprostol by Venezuelan women. Since 2013, they have answered approximately 450 calls per month.

Commonalities and differences

The five hotlines described here are all members of the Red de Experiencias Autónomas de Aborto Seguro (REAAS, Network of Autonomous Experiences for Safe Abortion). This network allows them to share their experiences of working locally.

These groups’ activities have a number of things in common. For example, the hotlines that use blogs and social networking disseminate the protocol for safe use of misoprostol, as recommended by the WHO, and those in Chile, Argentina and Peru reproduce in detail in their manuals information in a manner that is accessible to a non-specialist population.

There are also a number of important differences between them. One example is that the hotline in Chile is the political project of a feminist organization that does not have the goal of dialogue with the State, but rather seeks to promote women’s autonomy in self-inducing abortion with misoprostol. This means not waiting for the State to grant women their “rights”.Citation30 This position is markedly different to the other four hotlines discussed in this paper, e.g. in Venezuela.

This survey of Safe Abortion Information Hotlines is not exhaustive, and the work they are doing may be occurring in innumerable contexts and with other characteristics. The examples provided consist of the first groups that were initiated in Latin America and that have promoted their activities onlines. There are also active hotlines in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, for example.

They must also be differentiated from those provided by other women's collectives. While in the hotlines presented here, the contact is exclusively by telephone, there are feminist groups who use other methods, for example “Socorristas en Red” (Women Rescuers Network) in Argentina, who are present in more than 16 cities in the country with the service "Socorro Rosa” (Pink Rescue).Footnote**** The group use their telephone line to establish contact with women who want to abort using misoprostol, but the counselling and accompaniment are provided in person until the process is complete.Citation34

A special case is that of Uruguay, where the law now allows abortion in the first trimester, but there is still at least one hotline that offers information and is attended by feminists from Mujeres en el Horno (Women in the Hot Seat).Footnote††††

What they have in common is that they are initiatives carried out by women’s collectives, and that they are not part of a health institution. On the contrary, they are spaces that provide health information and challenge biomedical organization as a hierarchical and patriarchal structure.

Financial support for these services is an important challenge. They sometimes receive financial support from international organizations, but only temporarily, and they must generate their own resources in order to operate. A great number of the collectives that do advocacy work in countries where abortion is legally restricted work this way. A variety of strategies implemented by these groups to maintain themselves have been recorded. For example, charging for phone calls, selling tickets for raffles, or inviting people to send donations to the collective’s bank accounts, among others.

What information do the Safe Abortion Information Hotlines provide?

During telephone communication, first the activists collect information about the woman making the call, more than anything to determine if she is able to use misoprostol and to rule out contraindications. Next, they provide information about the dosage and the routes of administration for the misoprostol pills,Footnote‡‡‡‡ the number of weeks of pregnancy in which it is recommended that they be used, the levels of efficacy, what symptoms to expect, possible side effects and complications, in which cases to seek help from a health professional, and other information. This is the basic procedures that all of the hotlines provide. The information offered comes from publications by the WHO and recognized scientific organizations.

Depending on the context, women also learn about the most common strategies to avoid being reported to the police by doctors if they need to go to a hospital. They are told what questions they might be asked in the medical institution if they present because of complications or to have a post-abortion ultrasound, and how to deal with those questions and any threats made by doctors to report them, while protecting their own rights and exercising their right to receive medical attention. The hotline functions as a tool for protecting the health of women who do not give up on their decision to abort in the face of criminal penalties, clandestinity, and stigma.

Internet access, when available, is a very helpful addition for women, as it lets them interact with the Safe Abortion Information Hotline through blogs, chat, Facebook and Twitter. It also makes it easier to contact a misoprostol provider. The illegal status of abortion has created a black market that leads to overpricing, greater risks of adulteration of the medicine, false medicines, and in some cases, women getting nothing after sending money.

In general, the hotline constitutes an easily accessible tool, especially in urban contexts, for anyone with a landline or cellphone. If a woman cannot cover the cost of the call, she can ask to be called back, leaving her number. With a cellphone, the first contact can be made via text message.

Another advantage of telephone communication is that it allows for maintaining anonymity in relation to a sensitive topic. Telephone contact avoids the stigmatization of women who want to abort. For adolescents, it allows them to maintain their privacy and find support when they are not getting it from their family or other adults.

However, it can be difficult to make the existence of the service known to women who live in isolated rural areas where there are no women’s collectives to transmit the information and the health professionals in the area do not do so, often due to lack of knowledge.

Currently, social networks like Facebook and Twitter favour the distribution of information, basically the telephone numbers of the hotlines. Widespread publicity of the hotline phone number is a key factor in their success. However, greater visibility also creates greater risks for the women’s collectives. In all countries in the region, the law establishes that offering information is not against the law, as the right to information is guaranteed by the national constitutions and through international treaties. However, anti-abortion groups often target Safe Abortion Information Hotlines in their protest actions.Citation35 False calls, unnecessarily occupying the telephone line, and reports to authorities are some of the actions that have been taken against these groups, although with little impact.

The Safe Abortion Information Hotlines can be made more effective in each of their contexts, by overcoming limitations, such as the comprehensibility of the information that it is provided in the local language. Migrant women who have not mastered the language, for example, including local terminology such as terms for sexual organs, may not understand the information completely. This difficulty can be compensated for by recommending that the women access the instruction manual of the organization online where the illustrations that accompany the text facilitate understanding the information.Citation27,30

In countries where abortion is legal, abortion services include care and counselling pre- and post-abortion, as well as contraceptive provision.Citation28 The lack of this holistic care is a shortcoming that the Safe Abortion Information Hotlines cannot overcome. It is the result of the adversity of the context in which women are forced to have clandestine abortions. There is no follow-up of the women who consult the hotlines. Once a woman has been advised, the system does not contemplate further communication or ask her to let them know what she decided, to continue with the pregnancy or to terminate it, and if she decided to terminate the pregnancy, how she did it and what the results were.

Some of the hotlines try to implement evaluation and follow up, but there is no way to document how many women are actually using the information or sharing it with others. It is also impossible to know if women are applying the information correctly or if it is useful, nor is it possible to carry out a self-evaluation of the service.

Even so, a hotline can orient women towards friendly, accessible health services, within their context. Detecting and socializing information regarding friendly health services in the region are high-impact actions for women who live in restrictive contexts. This type of health service should include a consultation with a professional or 24-hour availability if the woman needs care, e.g., for incomplete abortion or confirmation that the abortion was complete, as well as her choice of contraceptive. In case it is needed, it is important for the hotlines to mention where there are therapeutic post-abortion care services, including ones that will do an ultrasound if it is thought necessary to check everything is OK.

Several of the hotlines have developed ways of obtaining and recording important non-personal data from women during a phone call. These data help the collectives to understand what kind of information is most needed by women calling them. For example, it is valuable to ask, in addition to socio-demographic data, about previous medical abortions, about the ease or difficulty of obtaining misoprostol and where it was obtained, and if the woman knows of a support network of health professionals. In-depth analysis of data collected is important, because it provides empirical support for issues about which there is not yet any or enough evidence. It is also about promoting knowledge creation with a feminist perspective.

Conclusions

This paper has shown how Safe Abortion Information Hotlines are a valuable service that allows women to obtain information about having a safe abortion, even in legally restrictive contexts. If these services were spread to more cities within these countries and elsewhere, many more women could obtain this information at close hand. Closeness increases women’s confidence in the service. It means they can recommend friendly health services if help is needed and can also help women to avoid health services where they may be mistreatedCitation36, and even reported to the police, if they experience complications.

As long as abortion is illegal, these services will continue to expand because they have shown themselves to be effective and to meet women’s immediate needs for help. Within a number of countries, there are places where women who seek abortions are prosecuted and where self-proclaimed “pro-life” groups are well organized. As such, commitment and networking with other supportive social actors are needed. Alliances with friendly health care teams should also be deepened, in order to promote access to safe abortion care.

Safe Abortion Information Hotlines are innovative models developed by activists outside of the health system, and they should be thought of as a form of feminist activist health promotion. They provide information on the use of misoprostol for the safe termination of pregnancy, which is consonant with a public health perspective, and within the ethos of harm reduction.Citation37 However, the hotlines described here began this work with the feminist goal of promoting women’s rights and human rights, and that remains their main purpose.

The women’s rights perspective means recognizing that women must confront “judicial, economic, social, or cultural barriers to obtaining abortion services in the health system, [and that] the use of misoprostol outside of the health system is safer than the methods these women would otherwise resort to”.Citation38 However, where abortion is penalized by the law, Safe Abortion Information Hotlines have not been implemented within or by health institutions. However, this approach to information provision is pertinent to health systems, and I believe they should be promoted as part of public health policy. Harm reduction interventions to prevent unsafe abortions save lives and should be supported – even by governments that do not support legalization or decriminalization of abortion.

Notes

* Also called medication abortion, mostly in the USA.

† The updated protocol for medical abortion with misoprostol alone can be found in detail in the 2014 WHO Clinical Practice Handbook for Safe Abortion Citation8.

‡ For example, PradaCitation18 shows that in 2009, half the abortions carried out in Colombia were with misoprostol. Similar results were observed previously in Brazil by Barbosa Citation19 and Costa Citation20.

§ See: http://www.fondation-copernic.org/spip.php?article75 for a short history (in French).

†† Women on Waves was founded with the goal of preventing unwanted pregnancies and unsafe abortions by providing sexual health services, including the abortion pill, on board a Dutch ship outside the territorial waters of countries where abortion is illegal. http://www.womenonwaves.org/.

††† http://lineabortoinfosegura.blogspot.com.ar/; Twitter: @LineaAbortoPeru.

‡‡‡ http://abortoinfosegura.com/blog/aviso-importante-telefono-no-atiende/, 17 March 2015.

§§§ Twitter account: @FaldasR and Blog http://infoseguraborto.blogspot.nl/.

‡‡‡‡ Mifepristone is not authorized for sale in these countries.

References

- B. Ganatra, A. Tunçalpa, H.B. Johnston. From concept to measurement: operationalizing WHO’s definition of unsafe abortion. Bull. World Health Organ. 92: 2014; 155. 10.2471/BLT.14.136333.

- Guttmacher Institute. Hechos sobre el aborto inducido en el mundo. 2012; Resumen. (http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/fb_IAW_sp.pdf).

- S. Singh, D. Wulf, R. Hussain. Abortion Worldwide: A Decade of Uneven Progress. 2009; Guttmacher Institute: New York.

- P. Bergallo. Aborto y justicia reproductiva: una mirada sobre el derecho comparado. Cuestión de Derechos. No 1. Julio de 2011

- M. Romero, N. Zamberlin, M.C. Ganni. La calidad de la atención posaborto: un desafío para la salud pública y los derechos humanos. Salud Colect. 6(1): 2010; 21–35.

- A. Faúndes, L.C. Santos, M. Carvalho. Post-abortion complications after interruption of pregnancy with misoprostol. Adv. Contracept. 12(1): 1996; 1–9.

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Preguntas clínicas frecuentes acerca del aborto farmacológico. 2008; WHO: Geneva. (http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789243594842_spa.pdf).

- L. Távara Orozco, S. Chávez, D. Grossman. Disponibilidad y uso obstrétricio del misoprostol en los países de América latina y el caribe. Rev. Peru. Ginecol. Obstet. 54: 2008; 253–263.

- World Health Organization. Clinical Practice Handbook for Safe Abortion. 2014; WHO: Geneva. (http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/97415/1/9789241548717_eng.pdf?ua=1).

- D. Diniz, A. Madeiro. Itinerários e métodos do aborto ilegal em cinco capitais brasileiras. Cien. Saude Colet. 17(7): 2012; 1671–1681.

- C. Shannon, B. Winikoff. How much supervision is necessary for women taking mifepristone and misoprostol for early medical abortion?. Women’s Health. 4(2): 2008; 107–111.

- L.S. Lie Mabel, S.C. Robson, C.R. May. Experiences of abortion: a narrative review of qualitative studies. BMC Health Serv. Res. 8: 2008; 150.

- R.I. Drovetta. O aborto na Argentina. Implicações do acesso à prática da interrupçao voluntária da gravidez. Revista Brasileira de Ciência Política. Janeiro–abril 2012; Instituto de Ciência Política da Universidade de Brasília, Dossier Aborto N°7: Brasília.

- M. Pazello. Internet, restrição de informações e acesso ao misoprostol. M. Arilha, T. Lapa, T.C. Pisaneschi. Aborto medicamentoso no Brasil. 2010; Oficina Editorial: São Paulo.

- D. Diniz, A. Madeiro. Cytotec e aborto: a polícia, os vendedores e as mulheres. Cien. Saude Colet. 17(7): 2012; 1795–1804.

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Lista Modelo de Medicamentos Esenciales. 16 Lista. March. 2009; WHO: Geneva.

- Consorcio Latinoamericano contra el Aborto Inseguro y Comité Derechos Sexuales y Reproductivos FLASOG. Declaración Primera Conferencia Latinoamericana Prevención y Atención del Aborto Inseguro. 30 de junio de 2009. (Lima, http://www.clacaidigital.info:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/21).

- E. Prada, S. Singh, C. Villarreal. Health consequences of unsafe abortion in Colombia, 1989–2008. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 118(Suppl. 2): 2012; S92–S98. 10.1016/S0020-7292(12)60006-X.

- R.M. Barbosa, M. Arilha. A experiencia brasileira com o Cytotec. Estud. Fem. 1(2): 1993

- N. Zambelin, M. Romero, S. Ramos. Latin American women’s experiences with medical abortion in settings where abortion is legally restricted. Reproductive Health. 9: 2012; 34.

- A. Cilumbriello, D. Colombo. La lucha por los derechos reproductivos en Italia. Z. Hlatshwayo. Estrategias para el acceso al aborto legal y seguro: un estudio en once países. 2001; Foro por los Derechos Reproductivos; Johannesburg, University of the Witwatersrand: Buenos Aires.

- A.A.V.V. Jane. Documentos del servicio clandestino de aborto de Chicago (1968–1973). Traducido y adaptado al español de la versión compilada y publicada en 2004 por Firestarter Press. Colección ‘Estrategias feministas frente al aborto clandestino’. Noviembre de 2014; Editorial “Dejemos la escoba: Santiago de Chile.

- L. Kaplan. The Story of Jane: The Legendary Underground Feminist Abortion Service. 1997; University of Chicago Press: Chicago.

- K. Stratten, R. Ainslie. Field Guide: Setting Up a Hotline. Field Guide 001. 2003; Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health/Center for Communication Programs: Baltimore.

- S. Yanow. Using Hotlines on Misoprostol for Safe Abortion to Improve Women’s Access To Information in Legally Restricted Settings. Conference Report. March 9-11 2012. (Bangkok).

- Coordinadora Juvenil por le Equidad de Género. Construyendo Redes de Confianza. Informe Blog 2010-2013. 2014. (Quito).

- Lesbianas y Feministas por la Descriminalización del Aborto, comp. Todo lo que querés saber sobre cómo hacerse un aborto con pastillas. 2010; El Colectivo: Buenos Aires. (http://www.editorialelcolectivo.org/ed/images/banners/abortopastillas.pdf).

- Lesbianas y Feministas por la Descriminalización del Aborto. Quinto informe de atención de la línea Aborto: más información, menos riesgos. http://abortoconpastillas.info/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/LAS-MUJERES-YA-DECIDIERON-QUE-EL-ABORTO-ES-LEGAL-15-12-12.pdf, Noviembre. 2012

- A. Mines, G. Díaz Villa, R. Rueda. El aborto lesbiano que se hace con la mano. Continuidades y rupturas en la militancia por el derecho al aborto en Argentina (2009-2012). Rev. Bagoas. 9: 2010; 133–160.

- Lesbianas y Feministas por el Derecho a la Información. Línea Aborto Chile: El Manual Cómo las mujeres pueden hacerse un aborto con pastillas?. http://infoabortochile.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/manual.pdf. 2013

- E. Seiter, Ã.E. Jara, A. León Saucedo. Experiencias de aborto clandestino con medicamentos en Chile. Lesbianas y feministas por el derecho a la información. Ponencia presentada en el 2° Congreso Latinoamericano y del Caribe sobre Salud Global, la Escuela de Salud Pública de la Universidad de Chile. de enero de 9–11 2013

- Colectiva por la Libre Información para las Mujeres. Primer Reporte Político a un Año de Funcionamiento de la Línea Aborto Información Segura. Lima: Mayo 2010-Junio 2011http://lineabortoinfosegura.blogspot.com.ar/2011/10/bajate-el-1er-reporte-de-la-linea-aqui.html

- Colectiva por la Libre Información para las Mujeres. Hablemos de aborto y misoprostol. Información segura y experiencias sobre su uso. Julio del 2014. (Lima, http://abortoinfosegura.com/).

- B. Grosso, M. Trpin, R. Zurbriggen. Políticas de y con los cuerpos: cartografiando los itinerarios de Socorro Rosa (un servicio de acompañamiento feminista para mujeres que deciden abortar). A.M. Fernández, W. Siqueira Peres. La diferencia desquiciada. 2013; Editorial Biblos: Buenos Aires.

- J.M. Vaggione. La cultura de la vida. Desplazamientos estratégicos del activismo religioso conservador frente a los derechos sexuales y reproductivos. Relig. Soc. 32(2): 2012; 57–80.

- C Steele, S Chiarotti. Con todo al aire: crueldad en la atención del posaborto en Rosario, Argentina. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24/Suppl): 2004; 39–46.

- L. Briozzo, A. Labandera, M. Gorgoroso. Iniciativas sanitarias: una nueva estrategia en el abordaje del aborto de riesgo. L. Briozzo. Iniciativas Sanitarias contra el Aborto Provocado en Condiciones de Riesgo. 2007; Arena: Montevideo.

- Ipas. Boletín Asuntos de aborto con medicamentos. Noviembre. 2012. (http://www.ipas.org/es-MX/What-We-Do/Comprehensive-Abortion-Care/Elements-of-Comprehensive-Abortion-Care/Medical-Abortion--MA-.aspx).

- M.L. Heilborn. Itinerários Abortivos em Contexto de Clandestinidade na Cidade do Rio de Janeiro–Brasil. Cien. Saude Colet. 17: 2012; 1699–1708.