Abstract

Abstract

Uganda continues to have poor maternal health indicators including a high maternal mortality ratio. This paper explores community level barriers affecting maternal health in rural Wakiso district, Uganda. Using photovoice, a community-based participatory research approach, over a five-month period, ten young community members aged 18-29 years took photographs and analysed them, developing an understanding of the emerging issues and engaging in community dialogue on them. From the study, known health systems problems including inadequate transport, long distance to health facilities, long waiting times at facilities and poor quality of care were confirmed, but other aspects that needed to be addressed were also established. These included key gender-related determinants of maternal health, such as domestic violence, low contraceptive use and early teenage pregnancy, as well as problems of unclean water, poor sanitation and women’s lack of income. Community members appreciated learning about the research findings precisely hence designing and implementing appropriate solutions to the problems identified because they could see photographs from their own local area. Photovoice’s strength is in generating evidence by community members in ways that articulate their perspectives, support local action and allow direct communication with stakeholders.

Résumé

L’Ouganda continue d’enregistrer des indicateurs médiocres de santé maternelle, notamment un taux élevé de mortalité maternelle. L’article recense les obstacles du niveau communautaire influençant la santé maternelle dans le district rural de Wakiko, Ouganda. Avec photovoice, une méthode de recherche participative à assise communautaire, sur une période de cinq mois, dix jeunes membres de la communauté âgés de 18 à 29 ans ont pris des photographies et les ont analysées, parvenant ainsi à comprendre les questions émergentes et à entamer un dialogue autour de ces questions avec la communauté. Ce travail a confirmé les problèmes connus des systèmes de santé, notamment le transport inadapté, l’éloignement des centres de santé, les longues attentes dans les centres et la mauvaise qualité des soins. Mais d’autres aspects à corriger ont aussi été dégagés, par exemple des déterminants sexospécifiques clés de la santé maternelle, comme la violence familiale, le faible emploi de contraceptifs et les grossesses précoces des adolescentes, ainsi que des problèmes dus à l’eau non salubre, l’inadéquation des systèmes d’assainissement et l’absence de revenu des femmes. Les membres de la communauté ont apprécié d’être informés des conclusions de la recherche, et ont conçu et mis en łuvre des solutions appropriées aux problèmes identifiés, précisément parce qu’ils pouvaient les voir dépeints dans les photographies de leur propre zone locale. La force de la méthode photovoice est qu’elle donne aux membres de la communauté la possibilité de faire des constatations et d’articuler leurs perspectives, de façon à soutenir l’action locale et autoriser une communication directe avec les parties prenantes.

Resumen

Uganda continúa teniendo indicadores de mala salud materna, tales como una alta razón de mortalidad materna. Este artículo explora las barreras comunitarias que afectan la salud materna en las zonas rurales del distrito de Wakiso, en Uganda. Utilizando Fotovoz, una estrategia de investigación participativa comunitaria, durante un plazo de cinco meses, diez jóvenes miembros comunitarios, entre 18 y 29 años de edad, tomaron fotografías y las analizaron; lo cual les permitió entender los asuntos emergentes y entablar diálogos con la comunidad al respecto. Por medio de este trabajo, se confirmaron los problemas de los sistemas de salud conocidos, tales como transporte inadecuado, larga distancia a las unidades de salud, largas esperas en las unidades de salud y calidad deficiente de la atención brindada, pero también se establecieron otros aspectos que debían ser tratados. Entre estos figuraban determinantes clave de salud materna relacionados con género, tales como violencia doméstica, bajo uso de anticonceptivos y embarazo precoz en la adolescencia, así como problemas de agua sucia, falta de saneamiento y falta de ingresos de las mujeres. Los miembros comunitarios agradecieron poder conocer los hallazgos de la investigación y, por ende, formular y aplicar soluciones adecuadas a los problemas identificados, precisamente porque los vieron representados en fotografías en su localidad. La fortaleza de Fotovoz yace en generar evidencia por miembros comunitarios en formas que expresan sus perspectivas, apoyan la acción local y permiten comunicación directa con las partes interesadas.

Uganda continues to have poor maternal health indicators. Although the maternal mortality ratio was reduced from 530 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 420 in 2005, the 2010 estimate of 310Citation1 is far from Uganda’s Millennium Development Goal target of 131 for 2015.Citation2 Despite 95% of women receiving antenatal care from a skilled provider for their most recent birth, only 57% of deliveries were at health facilities.Citation3 Numerous studies have established the problems causing high maternal mortality in Uganda.Citation4,5 These include limited access to health services and poor health seeking practices.Citation6 Those most affected are the poor, mainly living in rural areas with limited resources and few health-seeking options.Citation5

Studies on community involvement in primary health care have mainly focused on community health workers, with little emphasis on youth.Citation7,8 However, youth have the energy and passion to lead community initiatives and may be an untapped resource,Citation9 as has been demonstrated in some studiesCitation10,11 and in the significant role they have played in HIV/AIDS and mental health.Citation12,13 In Uganda, not only do youth comprise a large part of the population,Citation3 but they also have several sexual and reproductive health needs, which are largely unmet.Citation14 Engaging youth in maternal health is important if programmes are to better understand their needs and also involve them in health improvement initiatives. This study gave youth the voice to be heard and to better understand the issues concerning them and their communities.

Community-based, participatory research has been increasing in health research,Citation15–17 emphasising the engagement of participants in all stages of the research process.Citation18 In addition to generating knowledge, community-based participatory research is an iterative process that involves reflection, shared learning and power sharing.Citation19 It supports a better understanding of social and physical determinants that impact the health of communities and supports communities in seeking improvements, for example in public health and livelihoods.Citation20 It is also useful in solving local problems and supporting social and policy change more broadly.Citation21 The extent to which these transformational and emancipatory aims are achieved, however, depends on the magnitude of community engagement and shifts in power from researchers to communities.Citation18

Photovoice was developed to enable people to share their experiences and the context of their environment through photographs. It has often been used as a community-based, participatory research approach by people with limited power, to capture aspects of their environment and experiences and share them with others.Citation22 The pictures can then be used, usually with captions composed by the photographers, to bring the realities of their lives and community to public and policy makers to influence change. The discussion of photographs promotes dialogue and knowledge, and facilitates understanding community assets and needs. In this way, photovoice can be used to explore sensitive issues such as sexual and reproductive health,Citation18 which could be challenging using other methodologies. Besides being a powerful tool for identifying community concerns and priorities,Citation23 photovoice has been shown to empower participants to improve their health and that of their communities through enhanced knowledge, self-confidence and critical thinking.Citation24

Photovoice enables participants’ involvement in various stages of research such as taking pictures, contextualization and participatory analysis.Citation25 There is also significant control of the research process by photovoice participants.Citation26 Dissemination of the qualitative research findings to the community can be spearheaded by the photographers through community presentations, and also to various stakeholders, leading to social changeCitation27 and influencing public health practice and policy.Citation28 In addition, visual data methods can generate information omitted from other forms of data.Citation29 We used photovoice to explore community level barriers affecting maternal health in rural Wakiso district, Uganda, as seen by youth. We used the methodology to learn alongside them, as they articulated their own understanding of maternal health barriers and facilitated community discussions on the issues they identified.

Methods

The study was qualitative and used photovoice as a community-based participatory research approach. Photography was used to explore the perspectives of youth on maternal health, carry out participatory analysis and disseminate findings to stakeholders. The study was carried out in Bulwanyi parish, Ssisa sub-county, Wakiso district, Uganda. The parish is predominantly rural and in the central region of the country. The main economic activities include agriculture, animal farming and small-scale trade. The study area has high rates of maternal mortality, comparable to other rural areas of Uganda.

Study participants and training workshop

Participants in the study were aged 18-29 years. The researchers were scientists with expertise in photovoice, maternal health and qualitative methods. Meetings were held between the researchers and local leaders to introduce the study. Bulwanyi parish has five villages, from each of which one male and one female participant were selected by community leaders. Selection was based on their level of education, occupation, economic and marital status, with the aim of ensuring diverse representation. A training workshop was conducted by the researchers for the ten participants chosen, which provided them with the knowledge and skills required for the research. This workshop, carried out at one of the schools in the area, lasted five hours and consisted of training in the use and care of cameras, and ethics in photography. To minimize potential risks to the participants, the training also discussed how to approach people and get their consent before taking their pictures. General maternal health issues such as antenatal care, delivery at health facilities and the importance of postpartum care were also explained during the workshop.

Photography assignment

Participants were asked to use the cameras provided to them by the researchers to capture aspects and situations in their community that related to maternal health. The participants were allowed to take as many photographs as they could over a period of five months. Monthly team meetings were held between them and researchers to discuss the photos taken during the previous month. In the event that someone did not provide consent for their photograph to be taken, the participants used notebooks to record what happened, which was then discussed during the team meetings. During the entire period, supervision by the researchers, including regular communication and follow-up visits, was carried out to ensure that the work was carried out as planned and any challenges faced were addressed.

Discussing photos and data analysis

During monthly meetings, each participant was asked to talk about all the photographs they had taken related to maternal health. From the photographs, issues discussed included how the pictures related to their lives and those of the community, and what they meant for the study. The discussions were facilitated by the researchers, who took note of the emerging issues. Pertinent issues that were not captured by the photographs were also raised during the meetings and discussed. The discussions were structured and guided by questions such as what was happening in the photo, how it related to the photographers’ lives and what could be done about it. More details of these discussions are described elsewhere.Citation30 A research assistant kept a record of all discussions, which was key in tracking the evolution of changing perceptions and challenges in the research. From the monthly participatory analysis, the researchers identified issues, themes and theories that arose. Summaries of the main themes emanating from each monthly meeting were also recorded. All discussions were tape-recorded and transcribed for further analysis. Atlas ti version 6.0.15 was used for thematic content analysis, also described elsewhere.Citation30 From the transcripts, codes were used to highlight the issues arising from the study from which themes emerged.

Dissemination

After data collection and participatory analysis, findings from the study were documented by the researchers and disseminated in three community workshops, which were attended by community leaders, health workers and researchers. A range of photographs selected by the photographers and researchers, showing the main themes emerging from the research, were displayed during the dissemination workshops. Although the workshops were facilitated by the researchers, the photographers presented the photographs which elicited discussion in the workshops. Recommendations for improvement of the problems identified in the study arose from the workshops.

Ethical approval and consent

The study was approved by the Makerere University School of Public Health Higher Degrees, Research and Ethics Committee. Research registration and clearance was also obtained from the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology. The photographers were informed during the training workshop about ethics in research using photography, including getting people’s consent before taking their photos. Participants provided written informed consent after explaining to them the research before they took part. No photograph showing individuals was released or used in any form for dissemination without the consent of both the photographer and those photographed.

Findings

The findings are described under the following three main headings: health systems challenges affecting maternal health, including perspectives on quality of care; gender-related social determinants of maternal health; and multi-sectoral concerns and other social determinants affecting maternal health.

Health systems challenges affecting maternal health

Long distances to health facilities and inadequate transport

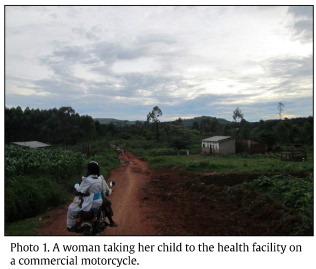

There are a few health facilities in the area and no government health facility in the five villages, thereby necessitating that residents seek health care in neighbouring communities, which were considered far away. The clinics were mainly used for minor ailments, with people having to go longer distances to seek services from government health facilities, the nearest being approximately 7 kms from the study area. It was also established that use of traditional healers, who were easily accessible to the community, was partly due to lack of transport to get to health facilities.

“Sometimes people in this village visit traditional practitioners when they do not have enough money to go to health facilities or when they are lacking transport or when it is late for them to move to the health centre. In other circumstances, they use traditional practitioners in case of an emergency because the health facilities are far away.” (Photographer 3, female, age 23)

“This woman had just given birth and she told me about some of the challenges she faced before going to the health centre where she gave birth. She said that the health centre was far and she had to travel at night and the health workers were not friendly at all. This was a government health centre.” (Photographer 1, female, age 20)

To aggravate the problem, photovoice participants discovered that the means of transport to get to these facilities was a major challenge, with many of the roads being of murram and impassable during the rainy season. There was no public transport that could be used and the only means was by commercial motorcycle, which was costly and not always safe (Photo 1).

Waiting for long hours at health facilities

Photovoice participants also established that patients seeking health care, particularly at government health facilities, had to wait for a long time before being attended to and at times had to lie down on the ground outside the facility due to their exhaustion and the lack of waiting facilities (Photo 2). The long waiting times were attributed to the low numbers of health workers available, and to the fact that some of them lived far away and arrived late for duty.

“The biggest problem we have at the health facilities is that the health workers come late. We have only four staff who live near the government health facility, but if they are not on duty, even if you sit at the health centre from sunrise to sunset, they will not come to attend to you. They have to wait for their colleagues who live far from the health facility. If they arrive at midday that is the time they will start handling patients.” (Photographer 2, male, age 25)

The other health system challenges affecting maternal health identified by photovoice participants were: lack of certain services at health centres, such as family planning; some services being offered only on specific days, such as antenatal care; and lack of awareness among women of the benefits of antenatal care and delivery at a health facility.

Perspectives on quality of care in public and private sectors

The participants agreed that patients were treated better in private health facilities than in government ones. However, some of the private facilities could not provide as wide a range of services, and referral of patients was often delayed because it represented loss of fees for further care.

“The care in private clinics is good, especially because they know that you are going to pay them money at the end, but the problem is that sometimes they will not even refer you to a bigger hospital when the case is complicated, as they are often interested in money. However, they also do not have any equipment for carrying out some diagnostic tests and therefore the situation could worsen afterwards.” (Photographer 10, female, age 20)

Problems with private health care therefore necessitated the community to seek health care at government facilities, particularly for cases that were considered major. However, pregnant women were at times mistreated by health workers at government health facilities. In addition, photovoice participants also noted that some government health workers also practised privately and would refer patients to their private practice, rather than treat them in the government facility.

“There is a health worker I know at a government hospital who can be very rude to you at the government facility, but when you go to his private clinic for treatment, he can give you all the necessary attention and you wonder why he has to behave in this way.” (Photographer 1, female, age 20)

Gender-related social determinants of maternal health

Domestic violence

The occurrence of domestic violence in the community was observed during the study. This was mainly in the form of men beating their spouses, and a few parents punishing their children through excessive beating, inflicting bodily harm. Photovoice participants discussed how domestic violence led to family break-ups, reflected the disempowered nature of women in their communities and also affected utilisation of health services, particularly by women.

“In this photo, I was trying to zoom in on the pregnant woman. This lady spends most of her time indoors, and she does not do any work. When her husband went to see a health worker, he was told that his wife will not be able to give birth normally because she is very short. Then he came and told the wife to pick up all her belongings and leave his house. The husband then beat her up and gave her some money that she should go back to her parents’ home. The money she was given was not enough and therefore she decided to stay somewhere nearby and come back to sleep in the husband’s house at night. But when she came that night she found that her husband had already got a new wife, who was taller.” (Photographer 8, male, age 19)

“In this photo, many people had come to intervene as the man was beating his wife. He was beating her because she wanted to leave him and go back to her parents with their two-year-old child, which the man was opposed to. The other people advised the man to beat up the wife until she leaves the child behind. They fought from morning till afternoon. We tried to stop them but they continued fighting. We even tried calling the police but they did not come. The mother of the woman finally sent some army personnel who came and fired bullets in the air to scare away the man and then they went with the woman and her child.” (Photographer 8, male, age 19)

Alcoholism

Drinking alcohol was found to be a serious problem, especially among men. High expenditure on alcohol by men usually led to reduction in resources available to support maternal health, for example paying for transport or access to health care. A few young people had also started drinking at a young age, and this was affecting their lives. For example, some children had dropped out of school partly due to alcoholism. Alcoholism was also found to contribute to domestic violence as many men would attack their spouses when drunk.

“I met this youth who was drunk at 1pm and sleeping on the ground. He drinks too much and is a very young man. I tried calling his name, but he was too drunk to respond. I hoped I would meet him again and counsel him that a youth should not behave like that, though I have not yet seen him. Imagine finding a person on the ground with his shoes having fallen off and with no idea of what was happening at such a time of the day.” (Photographer 9, male, age 29)

Family planning

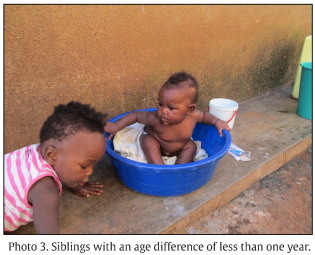

Generally, there was low use of contraception by the community. The main reasons given were inadequate knowledge of the various methods and lack of support of women by their spouses in using contraceptives.

“This lady was at the health centre. She looks quite old but was pregnant and had a young child who she had come with. It is rather risky for the health of women of her age to get children at such a rate without spacing them adequately. When I spoke to her, she told me that the husband does not want to hear anything about family planning. She had wanted to end with their sixth child, but she again found herself pregnant.” (Photographer 10, female, age 20)

Participants also noted that there were negative perceptions regarding the side effects of contraceptives. The main side effects reported included headache, nausea, weight gain, weight loss, interruption in menstrual cycle, reduced breast milk and delay in conceiving after stopping their use. Limited use of contraceptives in the area led to a high birth rate. Photovoice participants noted that some families were not able to adequately provide for their large families. Low use of family planning also led to poor spacing of children, leading to siblings that were very close in age (Photo 3).

Teenage pregnancies

Teenage pregnancy was a problem in the study area, with sexual partners of young women being both their peers and older men. Pregnancy was found to be one of the reasons why many girls were dropping out of school at an early age. In addition, the high risk nature of some teenage pregnancies entailed care that was at times not available at local health facilities.

“Sometimes young girls get pregnant and do not even know the father of the baby. There are also older men besides youth who are responsible for this. You can meet a 40-year-old man dating a 16- or 18-year-old girl. You may find that the girl even knows about the other women this man is committed to but that does not stop her from continuing with the relationship.” (Photographer 6, female, age 25)

“In this village, many girls who have given birth in the last two years are under 18 years old. These girls end up becoming pregnant when they are still in school and this leads to them dropping out. This has also put more pressure on the existing health centres to be able to cater for them. In fact, most of them deliver through caesarean section, hence require skilled care.” (Photographer 7, female, age 24)

The participants suggested that health education for both boys and girls be carried out to support their decision-making regarding sexuality and use of preventive health measures to change the trend of increased teenage pregnancies in the community. This intervention was expected to be able to contribute to reducing the number of teenage pregnancies in the community (Photo 4).

Multisectoral concerns and other social determinants affecting maternal health

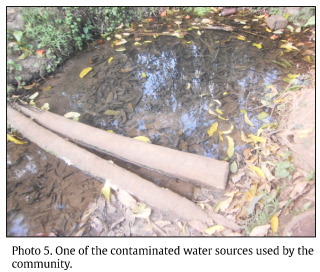

Water and sanitation

The water and sanitation status in the study area was poor. This included low safe water coverage, poor state of existing water sources and dilapidated latrine structures. The risk of contamination of many water sources was aggravated by the fact that they were being shared with animals. It was noted that pregnant women were no exception in using unsuitable water and sanitation facilities, hence the likelihood of them contracting water-borne infections. The status of some water sources not only posed a risk of diseases from drinking contaminated water, but also the possibility of children drowning in the unprotected sources (Photo 5).

“This is the well we use in our village. I found this boy fetching water from it and as you can see, drawing water from this well is very risky as you have to bend forward, because it is an open well. I was really touched since in case of any slight mistake, he could fall in and drown. When I asked him whether his mother was at home, he said yes and that his other brother had gone to school. I really felt bad and I am going to start a campaign to talk to the relevant authorities to intervene and protect this water source so as to avoid accidents that could happen.” (Photographer 5 male, age 26)

“This is a photo of a latrine that is used by the six tenants of that house. The latrine fell on one side and there is no longer any privacy as it is now just an open hole. I advised them to discuss amongst themselves and see how they can improve the latrine so that it is more decent, but they insisted that it is the responsibility of the landlord to take care of such matters and not them. So when they fall sick, is it the landlord who treats them?” (Photographer 8, male, age 19)

Nutrition

The participants noted that good nutrition is very important for the entire family but specifically for pregnant women. They identified a wide range of foodstuffs that could be included in the diet of pregnant women and lactating mothers. These included fruits, green vegetables, and sources of protein and carbohydrates.

“A pregnant woman needs milk, which is a very important food for her even after giving birth. So as families plan, they could have a cow at home, which would not require a lot to look after. It would be taken to the field as someone is going to the garden, eat peelings from the foods they eat, drink water that has been used for washing and if looked after very well it could help in sustaining the family.” (Photographer 2, male, age 25)

Women were mainly responsible for agriculture to provide food for their families. It was noted that many women continued with their agricultural and related responsibilities till late in pregnancy, with limited support from their spouses.

“In this photo, a cow had given birth and I found a pregnant woman carrying the calf, taking it home from the garden. Given that the woman was soon to be giving birth, I would have expected her to be helped by the husband in such a situation, but he was not there. This demonstrates that pregnant women continue doing most of their routine work even when pregnant.” (Photographer 4, male, age 24)

Income generation and diversification

Photovoice participants established that many women were not getting adequate financial support from their spouses, particularly during pregnancy, yet only a few were involved in any income-generating activities of their own. This affected health care-seeking by women, such as for antenatal care, because of lack of money to pay for transport and other services.

“This woman has so many children and was pregnant again. She told me about the challenges she faces, including the husband not giving her any money when she wants to go to the hospital, yet she is a housewife with no income. She said that the husband cares more about the children, with little attention given to her.” (Photographer 4, male, age 24)

In addition, many families were found with only one source of income, such as agriculture. Thus, if there were no good yields from the garden, the family income would be reduced and this would affect their family welfare, as well as access to health care, including maternal health services. The participants therefore suggested diversification of family income, such as involvement in other income-generation activities, so as to be able to meet the needs of family members (Photo 6).

“This he-goat belongs to a certain woman. It is of a very good breed so most people in the community bring their she-goats for impregnation. In a day, over five goats are brought here and each goat owner pays 3,000 Uganda shillings [about 1 US dollar] for the services. They say if impregnated by this he-goat, the she-goat would produce two or three kids at one go. In our previous meeting, we spoke about not depending on one activity such as agriculture for a livelihood, and this would be a good option. Even if you have your saloon, you can still rear some goats.” (Photographer 7, female, age 24)

Discussion

The many challenges faced by women in these rural communities in accessing maternal health services are well known and have been identified in other research. However, as they still exist, they must be reemphasised, and younger generations informed of them, until something is done to improve the situation.

The Ugandan health system includes a mandate that each parish must have a health centre to serve the parish community. However, the parish in which this study was conducted had no government health facility. Even where private clinics exist, though, rural communities many times prefer government ones, due to the absence of user fees and the availability of care for serious conditions.Citation31,32 However, as this study shows, long waiting times affect patient satisfaction and thus utilisation.Citation33 Lack of family planning services in this community is limiting the use of contraception, leading to unwanted pregnancies. Thus, it is necessary for the government to increase the number of health facilities in such rural areas as well as recruit more health workers to work in existing facilities to reduce waiting times.

This community thought quality of health care was better in private facilities compared to government ones, which is also reported elsewhere,Citation34,35 and reduces utilisation of services as well.Citation36 Indeed, it is well known that the poor attitudes of health workers towards patients, including pregnant women, is a major contributory factor in shunning of facilities.Citation37 The World Health Organization statement on the prevention and elimination of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth calls for reducing the mistreatment of women during delivery, a worldwide phenomenon.Citation38 Deficiencies such as delay in referral of patients to an appropriate level facility can lead to poor outcomes, including maternal death.Citation39 If women go to private facilities due to better quality of care, even if they have other deficiencies,Citation40 it undermines the perceived need to improve government facilities.

As this study demonstrates, photovoice can support data gathered using traditional methods, and identify and confirm problems.Citation29 These include the unmet need for family planning and facility-based delivery care. To ensure better maternal health outcomes, it is also important that gender-related social determinants such as domestic violence and alcoholism, leading to increased risk of miscarriages and other complications,Citation41–44 and sexual relationships in which older men take advantage of young girls, which leads to the negative consequences of early teenage pregnancies, are given due consideration and attention. The low use of contraceptives in the community was partly attributed to limited knowledge about the available options and fear of side effects, found also in other studies.Citation45,46 Health workers must be trained to teach the community (men as well as women, unmarried as well as married) about family planning methods so as to decrease misconceptions and increase their use. From the findings of this study, it is evident that programmes aimed at improving maternal health in an integrated way should also consider addressing the sexual and reproductive rights drivers of poor health in this community, as they have a significant impact on women, children and families. By visualising these issues through local photographs, photovoice is a strong tool for capturing problems relevant to the lives of the photographers, their communities, and health priorities.Citation47,48 Several other social determinants of health such as unclean water and poor sanitation, lack of income generation among women and poor nutrition, are also key in improving maternal health. Yet they have not been prioritised in other community studies on maternal health in low- and middle-income countries.Citation49–53

The photovoice photographers benefited from the project by becoming more knowledgeable about maternal health and increasing their capacity to address problems affecting their communities.Citation30 During the course of the study, they were involved in health education, promoting healthy practices and carrying out voluntary work in their villages. In addition, the dissemination workshops, where selected photos were displayed and discussed with the community and its leaders, were key in identifying community problems and devising solutions for them. For example, as regards teenage pregnancies, one community invited a non-governmental organisation to work with young girls and boys to sensitise them about early pregnancies and the importance of staying in school. Another example was when water user committees were advised to ensure public water sources were cleaned and maintained. Men were encouraged to support their wives, particularly during pregnancy, and to stop domestic violence.

It was clear that the communities appreciated learning about the issues emanating from the research precisely because they could see photographs taken in their own local areas, as compared to hearing about the research findings in other ways. This and other benefits from photovoice, such as community empowerment and action, building local capacity and involving stakeholders in improving the lives of communities, have also been identified in other studies.Citation24,27

Quality of care in health systems includes effectiveness, efficiency, accessibility, patient-centred care, equity and safety,Citation54 but this study focused on perceived patient satisfaction with services offered at health facilities, and particularly the attitude of health workers. This was appropriate in that photovoice is a methodology that captures user perspectives, which are essential when seeking to improve sexual and reproductive health and rights. While the study mainly engaged a small group of youth and young adults from a small number of villages, the themes they explored resonate with an understanding of the context of sexual and reproductive rights that underpin maternal health in many contexts, including in and beyond Uganda. Photovoice’s strength is in generating evidence by community members in ways that articulate their perspectives, support local action and allow direct communication with stakeholders.

Acknowledgments

This work is derived from a competitive small grant that builds young researcher capacity within the Future Health Systems Research Consortium, supported by the UK Department for International Development (DFID). The authors wish to thank the participants, local leaders and community mobilisers for their support and contributions towards implementation of this photovoice project.

References

- World Health Organization. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2010. 2012; WHO: Geneva. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/monitoring/9789241503631/en/.

- Government of Uganda. National Development Plan (2010/11–2014/2015). 2010; Uganda GoU: Kampala.

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics and ICF International Inc. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2011. 2012; UBOS, Calverton MD: ICF International Inc: Kampala. dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR264/FR264.pdf.

- J. Okal, L. Kanya, F. Obare. An assessment of opportunities and challenges for public sector involvement in the maternal health voucher program in Uganda. Health Research Policy and Systems. 11: 2013; 38. 10.1186/1478-4505-11-38.

- S.N. Kiwanuka, E.K. Ekirapa, S. Peterson. Access to and utilisation of health services for the poor in Uganda: a systematic review of available evidence. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 102(11): 2008; 1067–1074. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.04.023.

- K.S. Khan, D. Wojdyla, L. Say. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet. 367(9516): 2006; 1066–1074.

- G.G. Mchunu. The levels of community involvement in health (CIH): a case of rural and urban communities in Kwazulu-Natal. Curationis. 32(1): 2009; 4–13.

- W. Rennert, E. Koop. Primary health care for remote village communities in Honduras: a model for training and support of community health workers. Family Medicine. 41(9): 2009; 646–651.

- B.N. Checkoway, L.M. Gutierrez. Youth participation and community change: an introduction. Journal of Community Practice. 14(1/2): 2006; 1–9.

- E. Tsui, K. Bylander, M. Cho. Engaging youth in food activism in New York City: Lessons learned from a youth organization, health department, and university partnership. Journal of Urban Health. 89(5): 2012; 809–827. 10.1007/s11524-012-9684-8.

- K. Davis-Brown, N. Carter, B.D. Miller. Youth advisors driving action: hearing the youth voice in mental health systems of care. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services. 50(3): 2012; 39–43. 10.3928/02793695-20120207-07.

- G.J. Huba, L.A. Melchior. A model for adolescent-targeted HIV/AIDS services: conclusions from 10 adolescent-targeted projects funded by the Special Projects of National Significance Program of the Health Resources and Services Administration. Journal of Adolescent Health. 23(Suppl. 2): 1998; 11–27.

- M.D. Weist. Toward a public mental health promotion and intervention system for youth. Journal of School Health. 71(3): 2001; 101–104.

- L.H. Bearinger, R.E. Sieving, J. Ferguson. Global perspectives on the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents: patterns, prevention, and potential. Lancet. 369(9568): 2007; 1220–1231.

- C.L. Balazs, R. Morello-Frosch. The three R's: how community based participatory research strengthens the rigor, relevance and reach of science. Environmental Justice. 6(1): 2013; 10.1089/env.2012.0017.

- A. Guta, S. Flicker, B. Roche. Governing through community allegiance: a qualitative examination of peer research in community-based participatory research. Critical Public Health. 23(4): 2013; 432–451.

- H. Tapp, L. White, M. Steuerwald. Use of community-based participatory research in primary care to improve healthcare outcomes and disparities in care. Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research. 2(4): 2013; 405–419. 10.2217/cer.13.45.

- R. Loewenson, A.C. Laurell, C. Hogstedt. Participatory Action Research in Health Systems: A Methods Reader. 2014; TARSC, AHPRSR, WHO, IDRC Canada, EQUINET: Harare.

- M. Dalal, R. Skeete, H.L. Yeo. A physician team's experiences in community-based participatory research: insights into effective group collaborations. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 37(6/Suppl.1): 2009; 288–291. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.013.

- M.R. Flum, C.E. Siqueira, A. DeCaro. Photovoice in the workplace: A participatory method to give voice to workers to identify health and safety hazards and promote workplace change-a study of university custodians. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 53(11): 2010; 1150–1158. 10.1002/ajim.20873.

- B.A. Israel, A.J. Schulz, E.A. Parker. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 19: 1998; 173–202.

- H. Castleden. Garvin T; Huu-ay-aht First Nation. Modifying Photovoice for community-based participatory Indigenous research. Social Science & Medicine. 66(6): 2008; 1393–1405. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.030.

- K.C. Hergenrather, S.D. Rhodes, C.A. Cowan. Photovoice as community-based participatory research: a qualitative review. American Journal of Health Behavior. 33(6): 2009; 686–698.

- M. Teti, L. Pichon, A. Kabel. Taking pictures to take control: Photovoice as a tool to facilitate empowerment among poor and racial/ethnic minority women with HIV. Journal of Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 24(6): 2013; 539–553. 10.1016/j.jana.2013.05.001.

- C. Wang, M.A. Burris. Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior. 24(3): 1997; 369–387.

- C. Catalani, M. Minkler. Photovoice: a review of the literature in health and public health. Health Education & Behavior. 37(3): 2010; 424–451. 10.1177/1090198109342084.

- N.E. Findholt, Y.L. Michael, M.M. Davis. Photovoice engages rural youth in childhood obesity prevention. Public Health Nursing. 28(2): 2011; 186–192. 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00895.x.

- O. Chukwudozie, C. Feinstein, C. Jensen. Applying community-based participatory research to better understand and improve kinship care practices: insights from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone. Family & Community Health. 38(1): 2015; 108–119. 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000052.

- L.S. Lorenz, B. Kolb. Involving the public through participatory visual research methods. Health Expectations. 12(3): 2009; 262–274. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2009.00560.x.

- D. Musoke, R. Ndejjo, E. Ekirapa-Kiracho. Supporting youth and community capacity through photovoice: Experiences from facilitating participatory research on maternal health in Wakiso district, Uganda. Report from photovoice project. 2014. Kampala, Uganda.

- J. Nabyonga Orem, F. Mugisha, C. Kirunga. Abolition of user fees: the Uganda paradox. Health Policy and Planning. 26(Suppl.2): 2011; 41–51. 10.1093/heapol/czr065.

- J. Konde-Lule, S.N. Gitta, A. Lindfors. Private and public health care in rural areas of Uganda. BMC International Health and Human Rights. 10: 2010; 29. 10.1186/1472-698X-10-29.

- A.A. Adeniyi, K.O. Adegbite, M.O. Braimoh. Factors affecting patient satisfaction at the Lagos State University Teaching Hospital Dental Clinic. African Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences. 42(1): 2013; 25–31.

- H.M. Babikako, D. Neuhauser, A. Katamba. Patient satisfaction, feasibility and reliability of satisfaction questionnaire among patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in urban Uganda: a cross-sectional study. Health Research Policy and Systems. 9: 2011; 6. 10.1186/1478-4505-9-6.

- R. Karkee, A.H. Lee, P.K. Pokharel. Women's perception of quality of maternity services: a longitudinal survey in Nepal. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 14: 2014; 45. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-45.

- C. Puett, H. Alderman, K. Sadler. 'Sometimes they fail to keep their faith in us': community health worker perceptions of structural barriers to quality of care and community utilisation of services in Bangladesh. Maternal & Child Nutrition. 14: 2013; 10.1111/mcn.12072.

- L.C. Kumbani, E. Chirwa, A. Malata. Do Malawian women critically assess the quality of care? A qualitative study on women's perceptions of perinatal care at a district hospital in Malawi. Reproductive Health. 9: 2012; 30. 10.1186/1742-4755-9-30.

- World Health Organization. The prevention and elimination of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth. 2014; WHO: Geneva.

- G.U. Ugare, W. Ndifon, I.A. Bassey. Epidemiology of death in the emergency department of a tertiary health centre south-south of Nigeria. African Health Sciences. 12(4): 2012; 530–537.

- J.C. Fotso, C. Mukiira. Perceived quality of and access to care among poor urban women in Kenya and their utilization of delivery care: harnessing the potential of private clinics?. Health Policy and Planning. 27(6): 2012; 505–515. 10.1093/heapol/czr074.

- B.L. Anderson, E.P. Dang, R.L. Floyd. Knowledge, opinions, and practice patterns of obstetrician-gynecologists regarding their patients' use of alcohol. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 4(2): 2010; 114–121. 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181b95015.

- S. Kita, K. Yaeko, S.E. Porter. Prevalence and risk factors of intimate partner violence among pregnant women in Japan. Health Care for Women International. 35(4): 2014; 442–457. 10.1080/07399332.2013.857320.

- S. Toutain, L. Simmat-Durand, C. Crenn-Hébert. Consequences for the newborn of alcohol consumption during pregnancy. Archives de Pédiatrie. 17(9): 2010; 1273–1280. 10.1016/j.arcped.2010.06.018.

- S. Leppalahti, M. Gissler, M. Mentula. Is teenage pregnancy an obstetric risk in a welfare society? A population-based study in Finland, from 2006 to 2011. BMJ Open. 3(8): 2013; 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003225.

- V. Naanyu, J. Baliddawa, E. Peca. An examination of postpartum family planning in western Kenya: "I want to use contraception but I have not been told how to do so". African Journal of Reproductive Health. 17(3): 2013; 44–53.

- E. Saroha, M. Altarac, L.M. Sibley. Low use of contraceptives among rural women in Maitha, Uttar Pradesh, India. Journal of the Indian Medical Association. 111(5): 2013; 302–306.

- P. Foster-Fishman, B. Nowell, Z. Deacon. Using methods that matter: the impact of reflection, dialogue, and voice. American Journal of Community Psychology. 36(3-4): 2005; 275–291.

- M. Teti, C. Murray, L. Johnson. Photovoice as a community-based participatory research method among women living with HIV/AIDS: ethical opportunities and challenges. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 7(4): 2012; 34–43. 10.1525/jer.2012.7.4.34.

- M.F. Malik, M.A. Kayani. Issues of Maternal Health In Pakistan: Trends Towards Millennium Development Goal 5. Journal of Pakistan Medical Association. 64(6): 2014; 690–693.

- A.S. Nyamtema, D.P. Urassa, J. van Roosmalen. Maternal health interventions in resource limited countries: a systematic review of packages, impacts and factors for change. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth. 11: 2011; 30. 10.1186/1471-2393-11-30.

- O.M. Campbell. Getting the basics right - the role of water, sanitation and hygiene in maternal and reproductive health; a conceptual framework. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 20(3): 2014; 252–267. 10.1111/tmi.12439.

- N. Nxumalo, O. Alaba, B. Harris. Utilization of traditional healers in South Africa and costs to patients: findings from a national household survey. Journal of Public Health Policy. 32(Suppl.1): 2011; 124–136. 10.1057/jphp.2011.26.

- C. Lucas, K.E. Charlton, H. Yeatman. Nutrition advice during pregnancy: do women receive it and can health professionals provide it?. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 18(10): 2014; 2465–2478. 10.1007/s10995-014-1485-0.

- World Health Organization. Quality of Care: A process of making strategic choices in health systems. 2006; WHO: Geneva. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43470#sthash.P1qv8izw.dpuf.