Abstract

Abstract

First documented in 1741, the practice of episiotomy substantially increased worldwide during the 20th century. However, research shows that episiotomy is not effective in reducing severe perineal trauma and may be harmful. Using a mixed-methods approach, we conducted a study in 2013–14 on why obstetricians and midwives in a large maternity hospital in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, still do routine episiotomies. The study included the extent of the practice, based on medical records; a retrospective analysis of the delivery notes of a random sample of 365 patients; and 22 in-depth interviews with obstetricians, midwives and recently delivered women. Of the 365 women, 345 (94.5%, 95% CI: 91.7–96.6) had had an episiotomy. Univariate analysis showed that nulliparous women underwent episiotomy more frequently than multiparous women (OR 7.1, 95% CI 2.0–24.7). The reasons given for this practice by midwives and obstetricians were: fear of perineal tears, the strong belief that Asian women have a shorter and harder perineum than others, lack of time in overcrowded delivery rooms, and the belief that Cambodian women would be able to have a tighter and prettier vagina through this practice. A restrictive episiotomy policy and information for pregnant women about birthing practices through antenatal classes should be implemented as soon as possible.

Résumé

Documentée pour la première fois en 1741, la pratique de l’épisiotomie s’est nettement développée dans le monde au XXe siècle. Néanmoins, il a été démontré que l’épisiotomie n’était pas efficace pour réduire les traumatismes périnéaux graves et pouvait être dommageable. Moyennant une méthode « mixte », nous avons réalisé une étude en 2013–2014 sur les raisons incitant les obstétriciens et les sages-femmes d’une grande maternité de Phnom Penh, Cambodge, à pratiquer encore des épisiotomies systématiques. L’étude incluait une évaluation de l’ampleur de la pratique, sur la base des dossiers médicaux ; une analyse rétrospective des comptes rendus d’accouchements d’un échantillon aléatoire de 365 patientes ; et 22 entretiens approfondis avec des obstétriciens, des sages-femmes et de jeunes accouchées. Sur les 365 femmes, 345 (94,5%, 95% IC : 91,7–96,6) avaient eu une épisiotomie. Une analyse univariée a montré que les nullipares subissaient plus fréquemment une épisiotomie que les multipares (RC 7,1, 95% IC 2,0–24,7). Pour expliquer cette pratique, les sages-femmes et les obstétriciens ont cité : la peur de déchirures périnéales, la conviction que le périnée des asiatiques était plus court et plus rigide que les autres, le manque de temps dans des salles de travail surchargées, et le sentiment que les Cambodgiennes pourraient avoir un vagin plus étroit et « plus joli » à travers cette pratique. Nous recommandons la mise en łuvre dès que possible d’une politique restrictive de recours à l’épisiotomie et une information pour les femmes enceintes des pratiques d’accouchement lors de séances de préparation prénatales.

Resumen

Documentada por primera vez en 1741, la práctica de episiotomía aumentó considerablemente a nivel mundial durante el siglo XX. Sin embargo, las investigaciones muestran que la episiotomía no es eficaz para disminuir el trauma perineal grave y puede ser dañina. Utilizando una estrategia de métodos combinados, realizamos un estudio en 2013–14 sobre por qué los obstetras y parteras en una importante maternidad en Phnom Penh, Camboya, aún efectúan episiotomías de rutina. El estudio incluyó la frecuencia de la práctica, basada en expedientes médicos, un análisis retrospectivo de las notas sobre el parto de una muestra aleatoria de 365 pacientes, y 22 entrevistas a profundidad con obstetras, parteras y mujeres que dieron a luz recientemente. De las 365 mujeres, 345 (94.5%, 95% IC: 91.7–96.6) habían tenido una episiotomía. El análisis univariado mostró que a las mujeres nulíparas les practicó una episiotomía con más frecuencia que a las multíparas (OR 7.1, 95% CI 2.0–24.7). Las razones dadas para esta práctica por parteras y obstetras fueron: temor de desgarros perineales, la convicción de que las mujeres asiáticas tienen un perineo más corto y más duro que otras, la falta de tiempo en salas de parto abarrotadas, y la creencia de que las mujeres camboyana podrían tener una “vagina más estrecha y más bonita” por medio de esta práctica. Se debe aplicar lo antes posible una política restrictiva referente a la episiotomía y proporcionar información a mujeres embarazadas sobre las prácticas relacionadas con el parto por medio de clases prenatales.

According to the Cochrane database,Citation1 episiotomy was first described in 1741 by Sir Fielding Ould in an essay on midwifery. Episiotomy is the surgical enlargement of the vaginal opening by an incision in the perineum (skin and muscles), mostly performed using scissors during a delivery in order to facilitate the baby’s birth and to prevent spontaneous and severe perineal tearing.

Worldwide, rates of episiotomy rose substantially during the first half of the 20th century. At that time there was also an increasing move for women to give birth in hospitals and for physicians to become involved in the normal uncomplicated birth process.Citation2 Although episiotomy has become one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures in the world, it was introduced in clinical practice without strong scientific evidence of its benefits.Citation3 Reported rates of episiotomies vary in different studies since 2000 from as low as 9.7% (Sweden) to as high as 100% (Taiwan).Citation4 In Asia, rates of episiotomy reported in 2005 varied from 42-98%. In China, the estimated rate was 82%,Citation4 in Viet Nam in 2013Citation5 and Hong Kong in 2006Citation6 over 85%. For nulliparous women, the episiotomy rate was as high as 91% in Nepal in 2001,Citation7 and 98% in Hong Kong.Citation6

Perineal tears are defined as any damage caused to the genitalia during childbirth. They are classified according to the extent of the damage. A first-degree tear is an injury to the perineal skin only; a second-degree tear means injury to the perineal muscles but not the anal sphincter; a third-degree tear also involves the anal sphincter complex; and a fourth-degree injury involves the anal sphincter complex and the anal epithelium.Citation1 Third- or fourth-degree perineal tears are the most serious and can lead to potential sequelae, such as fecal incontinence and recto-vaginal fistula. An episiotomy involves the same structures as a second-degree tear but is easier to repair, being less anarchic.Citation8 Episiotomy is therefore frequently performed with the intention of preventing third- or fourth-degree tears, despite lack of proof of its effectiveness.

In Asia, the traditional belief is that women’s perineum is shorter, less flexible and more susceptible to trauma than in other women.Citation9 Indeed, the results from infrequent research remain controversial. Three studies conducted in 2003, 2007 and 2008 have shown that Asian ethnicity may be a risk factor for severe perineal tears. The first study, based on an audit of a US medical procedures database, studied 34,048 vaginal deliveries and concluded that Asia ethnicity was an independent risk factor for severe vaginal lacerations (OR 2.04 ; 95% CI, 1.43-2.92).Citation10 The second study, in Australia, was a prospective study of 6,595 women over two years and concluded that women of Asian origin were almost twice as likely to have severe perineal trauma as non-Asian women (OR 1.9; 95% CI, 1.3-2.8).Citation11 The third study was a randomized clinical trial in two maternity wards in Australia of 697 women. It showed that Asian women had significantly more perineal trauma compared with non-Asian women (OR 2.6; 95% CI, 1.4-4.7).Citation12 Dua et al. also showed in 2009 that having a shorter perineal body may be a risk factor for perineal trauma for primigravid women.Citation13 However, measuring the distance from the posterior fourchette to the centre of anal orifice in 1,000 women living in the UK, and collecting data on ethnicity, they also showed that the mean perineal length in Caucasian women was 3.7±0.9cm, which is not significantly different from Asian women, with a perineal length of 3.6cm±0.9cm. Another 2009 study in Hong Kong among 429 Chinese women reached the same conclusion: Asian women do not have a shorter perineum than Caucasian women.Citation9

The study by Lede et al. in 1996Citation3 was the first to contest routine episiotomy. Since then, the routine use of episiotomy has largely been questioned by national and international institutions, e.g. Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists, UK; Collège National des Gynécologues Obstétriciens Français, France (CNGOF); and the World Health Organization (WHO).Citation14–16 A 2009 Cochrane review by CarroliCitation2 found that episiotomy can cause unsatisfactory anatomic results such as skintags and asymmetry, and also fistula, increased blood loss, haematoma, pain, oedema, infection, dehiscence, dyspareunia and excessive cost. It compared the effects when episiotomy use is restrictive, i.e. rarely performed, to its routine or frequent use. This review included eight studies (5,541 women). It found that restricting episiotomy appeared to have a number of benefits: there was less severe posterior perineal trauma, less suturing, fewer healing complications, and no difference in severe vaginal/perineal trauma, dyspareunia, urinary incontinence or several pain measures. However, restrictive episiotomy was associated with more anterior perineal trauma.

Two more recent French studies (not included in the Cochrane review) also showed benefits of a policy of restrictive episiotomy.Citation17,18 They found that the recommendations of the CNGOF to restrict the use of episiotomy led to a dramatic decrease in the episiotomy rate (in the first study from 19% to 3% between 2003 and 2007 (17) and in the second study from 56% to 13% between 2004 and 2009Citation18 without any significant increase in severe vaginal tears (third and fourth degree) or sequelae (p<0.01).

Two studies have looked at the replicability of a policy of restrictive episiotomy in Asia. Through a prospective study in Hong Kong (429 women), Lai et al. concluded in 2009 that restrictive episiotomy reduced the number of episiotomies without compromising perineal safety. In Nepal, researchersCitation7 reported a rate of episiotomy at 91% in primigravidas in 2001. After introducing a protocol of restrictive episiotomy, this prospective observational study found episiotomy in 22% of primigravidas, with the rate of third-degree perineal tears in an acceptable range.

A search of PubMed and the Directory of Open Access Journals found no studies in Cambodia on the perineum, perineal length or perineal trauma. Only one small study of 40 deliveries, published in 2012, found an episiotomy rate of 85%.Citation19

This study in 2013 and 2014 in Cambodia, a low-income Southeast Asian country of about 15 million inhabitants,Citation20 aimed to assess the prevalence, risk factors and reasons for the practice of episiotomy in a large maternity ward in the capital city of Phnom Penh. It combined a retrospective quantitative data analysis with a qualitative survey. We questioned why obstetricians and midwives still perform routine episiotomies in Cambodia while the evidence shows that it is not beneficial for women.

Methods

The health system in Cambodia is pluralistic, with a large, mainly unregulated private sector and a “fine-meshed network of public facilities”.Citation21 In 2014, the public sector had 97 referral hospitals including seven in Phnom Penh, and 1,105 health centres, including 33 in Phnom Penh.Citation22 Both obstetric practices and episiotomy rates varied from one maternity unit to another. The maternal mortality ratio in Cambodia dropped dramatically from 510 per 100,000 in 2000 to 170 per 100,000 in 2014.Citation23,24 This success is attributed to several factors, including the strong engagement of the Cambodian government in investing in midwifery training. The number of trained midwives in the public health sector increased from 3,441 to 5,290 between 2009 and 2014.Citation22 This was the result of “managerial choices to accelerate and operationalize universal access to care”.Citation25 An “expanding primary health care network, a monetary incentive for facility-based midwives for every live birth, and an expanding system of health equity funds, making health care free of cost for poor people” also contributed to improving the health system.Citation21

The improvements in skilled birth attendance contributed to the reduction of maternal mortality ratio. Births delivered by trained staff at health facilities increased from 39% to 80% between 2008 and 2014,Citation22 despite the persistence of socio-cultural, economic and geographical barriers to accessing health services in Cambodia.Citation26 A consequence of this was an increase in the workload in maternity units.

Our study was conducted in the Maternity Unit of Calmette, a referral hospital in Phnom Penh. The maternity ward had seven delivery tables and 88 beds, 15 obstetrician-gynaecologists and 62 midwives. Data from Calmette Maternity show that the number of deliveries increased by 311% in the 11years between 2003 and 2014, from 3,220 to 10,022, leading to overcrowded and busy delivery rooms. Deliveries were performed both by midwives and obstetricians. Delivery cost the equivalent of US$60 for a vaginal delivery, $75 for a vaginal delivery with vacuum extraction, and $278 for a caesarean delivery. Episiotomy was included in the package of vaginal delivery.

After four months of observation and immersion in the hospital in 2013, we conducted a hospital-based survey from February to March 2014 using a mix of methods: first, a quantitative analysis of the use of episiotomy in Calmette hospital in 2013 based on delivery records; secondly, a retrospective analysis of a random sample of deliveries in 2013, based on delivery records and the patients’ medical files; thirdly, in-depth interviews with health professionals and mothers. The interviews aimed to compliment the quantitative data by describing and understanding the reasons for and representations of episiotomy among health care providers and parturients.

Quantitative data

The first source of information was the registry in which the midwives daily record detailed information about deliveries and summaries of activities. The second source was women’s medical files. From the summaries, we extracted daily numbers of deliveries and their type (vaginal, instrumental, surgical); and perineal procedures (episiotomy, tears). From a random sample of the patients’ medical files, we also extracted relevant socio-demographic and medical information. Data collected were: parity, age at time of pregnancy, type of delivery (normal vaginal or vaginal with vacuum extraction), state of perineum (intact, torn and/or episiotomy), infant birth weight, mother’s height, mother’s weight gain during pregnancy. We chose to extract these data after having explored with the obstetricians what medical information led them to perform episiotomies.

The size of our random sample of patients was calculated using Stata Version 8 (Stata Cooperation, College Station, TX). From interviews with the head of maternity, we estimated 90% episiotomies. We calculated that a total of 301 records would be necessary to show an episiotomy prevalence of 90–94% with 10% precision (alpha=0.05, power 90%). We added 20% more files in case of non-usable ones, i.e. we needed a total of 360 women. Finally, we chose to select one file per day to represent the possible weekly variation in episiotomies between normal days, holidays and duty days. We therefore randomly selected 365 deliveries out of the 8,842 deliveries in 2013, using the following method: the first woman we included gave birth on 1 January 2013 and was randomly chosen using one number picked from random numbers generated by Excel software. We then included one file for every 29th delivery until we obtained the targeted sample.

Quantitative data were entered in an Excel datasheet, cross-checked against original data sheets and analyzed using Stata 13 (Stat Corp., College Station, TX, USA) software. Descriptive analyses present medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous data and numbers and percentages for categorical data.

Factors associated with episiotomy and with vaginal tears were explored using logistic regression. The strengths of these associations were described with odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI). For all analyses, statistical significance was defined at a 5% threshold (p<0.05).

Qualitative data collection

In-depth interviews were conducted with five midwives and six obstetrician-gynaecologists, and 11 mothers admitted to the post-partum ward. Interviews were conducted until saturation of information was obtained. Interviews were based on willingness and availability of both health workers and women, and lasted 45minutes on average.

Interviews with the mothers were in Khmer, the local language, with a medical doctor translating into French, as the interviewer was a French social demographer. Interviews with midwives and medical doctors were done in French to avoid the need for translation. Questions to midwives and obstetricians related to their practice of episiotomy and their beliefs about female genitals: in which cases do you perform episiotomy? Why do you perform routine episiotomies? Are Asian perineums shorter than others?

Questions to mothers related to their knowledge of episiotomy; did they know whether and why they had one, whether they had received advice on their care; whether they were satisfied to have undergone an episiotomy; and whether they had sexual intercourse during their pregnancy. Interviews focused on these key points but were open, not limited to the pre-determined topics, and allowed the generation of unexpected information and themes.

All interviews were recorded except one (refusal by the interviewee, a medical doctor). The entire recording was then transcribed in electronic format and analyzed using Nvivo Version 10 software. Content analysis involved reading and examining transcripts to develop a sense of the themes and sub-themes as they related to the research objectives. This inductive thematic approach was used to understand and analyze the logic and practices of the clinicians for delivery and the women’s perceptions and views of their bodies.Citation27

The main findings from this study were later shared with the midwives and obstetricians of Calmette Maternity during a workshop on 27–28 March 2014. Comments and questions raised during the workshop were integrated into the final analysis.

This survey has several limitations. The sample size was limited due to time and budget constraints. The quantitative part of the study has the bias of all retrospective studies. In particular, we were not able to fully document the perineal tears, which were rarely described in the medical files. Interviews with post-partum mothers may have been influenced by the presence of an obstetrician acting as the translator.

The study protocol was approved by the National Ethics Committee for Health Research (NECHR, Ministry of Health, Phnom Penh). Interviews were conducted after obtaining informed oral consent from interviewees. Oral and written records and notes were anonymous.

Findings: Asian women’s perineums

In 2013, 8,842 deliveries were recorded at Calmette hospital, including 6,243 vaginal deliveries (70.6%), and 2,599 caesarean deliveries (29.4%). Of the 6,243 vaginal deliveries, 382 (6.1%) needed vacuum extraction. The median age of the women was 27.6years (range 14–46). Of the 365 women included in our study sample, 195 (53.1%) were nulliparous, 112 (30.7%) primiparous, and 58 (16.2%) multiparous. The median term at delivery was 39weeks (IQR 38–40). The median maternal weight gain was 11kg (IQR 9–14). The median newborn birthweight was 3,100g (IQR 2850–3400).

Episiotomy is routinely performed – mostly on nulliparas

Episiotomy was performed on 5,745 women (92.0%), and 215 (3.4%) vaginal tears were recorded. In our study sample, 345 (94.5%, 95% CI: 91.7–96.6) underwent an episiotomy and 15 (4.1%, 95% CI: 2.3–6.7) had a vaginal tear without associated episiotomy. Only five women (1.4%) had no episiotomy and no tears. There was no report of tears induced by episiotomy in these 365 medical files.

Univariate analysis found that more nulliparas underwent episiotomy than multiparas (OR 7.1, 95% CI 2.0–24.7, p=0.002). None of the other factors suggested by the gynaecologists (term of pregnancy, newborn birthweight, type of vaginal delivery with or without vacuum extraction, mother’s height and mother’s weight gain during pregnancy) were found to be associated with a higher risk of episiotomy (data not shown). Surprisingly, a low or normal newborn weight was not associated with less frequent episiotomy. The data show that in this maternity unit, episiotomies were performed for almost every vaginal delivery. Vaginal tears were significantly less frequent for nulliparas (OR 0.08, CI 0.02-0.46, p=0.002), as these women almost all had an episiotomy. No other factors were associated with tears.

The high overall episiotomy rate (94.5%), in one of the largest maternity units in Cambodia, was six times higher than the official recommendations by the French CNGOF, the only guidelines we found providing recommended episiotomy rates.Citation15 WHO recommends the use of a restrictive episiotomy policy,Citation16 but to our knowledge does not specify a recommended rate.

The episiotomy rate found in Calmette Hospital was similar to those found in Viet Nam and other Asian countries (China,Citation9 Nepal,Citation7 and TaiwanCitation4). Two other recent studies, in 2012 and 2013, have pointed to a gap between evidence-based international guidelines and current skilled birth attendant practices during labour, birth and immediate post-partum care in Cambodia today.Citation19,28

Why episiotomy rates were so high

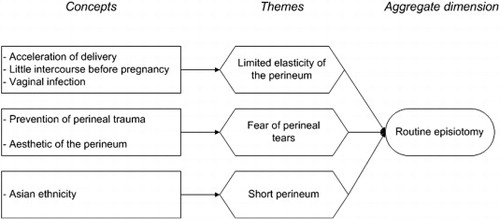

show the different factors and beliefs contributing to routine episiotomy in Calmette Maternity.

Fear of tearing

According to both the midwives and obstetricians in Calmette Hospital interviewed, episiotomy is mainly performed to prevent perineal trauma.

“If we do not do an episiotomy, we will get a tear.” (Obstetrician No.1)

Belief that Cambodian women have shorter and less elastic perineums than Caucasian women

All health care workers interviewed mentioned “Asian ethnicity “ as a justification for routine episiotomy, along with the assumption that perineal length in Asian women is shorter than in others and lacks elasticity, thereby increasing the risk of perineal trauma.

“The perineum of Asian women is short, it is not long, like European women’s.” (Obstetrician No.1)

“The perineum of Cambodian women is not elastic. It is a bit hard.” (Midwife No.2)

In fact, a strong negative correlation (r=0.6) has been noted in the literature between perineal length and third-degree tears (p=0.047).Citation13 Several studies have been done on perineal length in developed countries but few in developing countries.Citation8 The only two studies we found in Asian women showed that Asian women do not have a shorter perineum than Caucasian women,Citation9,13 so this belief is not supported by the existing evidence.

The health workers also explained the perceived lack of perineal elasticity as due to a limited amount of sexual intercourse between loss of virginity and first delivery.

“Women get pregnant very quickly after their wedding, after about one year, and the perineum is not very elastic by then.” (Midwife No.2)

Virginity at marriage is still a strong norm in Cambodian society today,Citation30 and premarital sex among women is infrequent.Citation21 Most of the women told us that they had had very little or no sexual activity during their pregnancy. However, even if the lack of elasticity in the perineum among nulliparous women is a risk factor for third- and fourth-degree tears,Citation8 no evidence supports the idea that frequent sexual intercourse would soften the perineum and make it less prone to injury.

The midwives and obstetricians also thought that perineal elasticity was reduced by vaginitis or vulvo-vaginal candidiasis, which they said were frequently found in Cambodian woman during pregnancy.

“Vaginitis is common during pregnancy; vaginal swabs and exams are not systematically carried out, they depend on the woman’ s ability to afford [the laboratory test]. It is difficult. It makes the vagina less extensible, and it bleeds a lot after delivery.” (Obstetrician No.5)

Vaginitis may be caused by vaginal douching, a very common practice in Cambodia.Citation31 These infections are under-diagnosed and under-treated during pregnancy, however, as laboratory exams are expensive (US$16.10 at Calmette). We did not find any information on this subject in the literature.

However, the literature does not support the belief that Asian women have a shorter and less elastic perineum than others. A systematic reviewCitation32 concluded in 2012 there was no evidence of risk for specific perineal trauma for Asian women living in Asia. In contrast, being of Asian ethnicity in some Western countries was identified as a risk factor for severe perineal trauma, but this review identified hidden factors that potentially explained this as arising for other reasons than ethnicity itself:

| • | The lack of a standard international definition for the term “Asian”. In particular, differences in ethnic group classification between the UK, USA and Australia limit the comparison and generalization of research findings. | ||||

| • | Difficulty of communication for Asian women in Western countries and potential factors within the birthing room setting may be influencing the practice among health workers. | ||||

Dahlen et al.Citation11 have reported that the strong association between Asian ethnicity and severe perineal trauma in Western countries could be explained by women’s inability to communicate effectively, being unable to understand the midwife’s advice, and being afraid and out of control when delivering, i.e. pushing inappropriately on the perineum.

However, based on our analysis of the literature, Asian ethnicity does not seem to be an independent risk factor for perineal trauma, at least for Asian women living in Asia. And if Dahlen et al. are right, then Asian ethnicity may be linked with other factors that increase the risk of severe trauma for Asian women living outside of Asia. But the belief that Cambodian women have a shorter perineum seems to be a “myth”.

Findings: the role of conditions in the delivery room

Birthing women’s lack of knowledge about episiotomy

Quality of care is a central part of legitimate expectations and of the rights of birthing women and their families. Over-medicalization is poorly documented, but has been identified as a big problem. WHO recently pointed out that a high clinic workload may go hand-in-hand with suboptimal quality of care.Citation33

Few of the women we interviewed knew why they had had an episiotomy; those who thought they knew why reported the same reasons as the health professionals (i.e. short perineum, to avoid tearing). The women seemed to have little other information and to accept episiotomy as unavoidable, and therefore did not question it.

“Almost all women have an episiotomy, that’s it.” (Post-partum woman No.1)

“No, I don’t know why the midwife has cut.” (Post-partum woman No.3)

“No, I don’t know whether the doctor has cut me.” (Post-partum woman No.10)

Diniz received the same responses in the context of routine episiotomy in Brazil,Citation34 and found that most women believed it was medically necessary to protect themselves and their baby. Diniz explains that in a context of shortage of beds in overcrowded hospitals, interventions such as this expedite labour and delivery. This was also mentioned by the women in our study:

“This is done to accelerate the labour, to make the baby come out fast.” (Post-partum woman No.8)

Overwhelmed delivery rooms leading to over-medicalized delivery

In 2004 in Brazil, episiotomy was included in the financial birth assistance package, as part of standard care, just as is the case in Calmette hospital now.Citation34 Thus, episiotomies may be done not for the woman but for the midwife/obstetrician – to accelerate the expulsion stage and save time during the delivery and the suturing process.

“The midwife does an episiotomy because she cannot wait for the stretching of the perineum.” (Obstetrician No.4)

“When there are complicated perineal tears, it takes too much time to suture them, more than just suturing an episiotomy.” (Midwife No.2)

Lack of time was a major reason cited by both the midwives and obstetricians for why they cut the perineum – to deliver women faster. The same reason was cited in a study about quality of maternity care practices among skilled birth attendants in Cambodia: episiotomy was performed in order to accelerate the delivery, given the high number of women in the labour ward.Citation19 It seems that the dramatic and continuing increase in hospital deliveries has encouraged this suboptimal care strategy in Calmette because of staff and time shortages.

In 2014 Van Lerberghe et al.Citation25 reported that Cambodia’s maternity care was characterized by an expansion in the network of birthing facilities, the scaling up of training for midwives, and a reduction in financial barriers. This perfectly describes Calmette hospital, where new buildings are built almost every year and where a large number of midwives have been deployed to cope with the increasing number of deliveries. Those authors point out that until very recently, midwives and doctors restricted the tendency to over-medicalize and promoted respectful woman-centered care in Cambodia, but this had received little or no attention. They explain that Cambodia has deployed “partly connected initiatives and measures to adapt to and improve on a changing environment, where strategies emerged and were self-organised over time, rather than as implementations of a pre-defined comprehensive plan”.Citation25

Pretty genitals and a tight vagina

Some midwives and obstetricians cited conjugal expectations and the “wish” of patients to have pretty genitals as reasons for a high episiotomy rate. The health professionals referred to the “aesthetic” aspect of the perineum: a perineum cut and sutured is nicer than a sutured perineal tear:

“If we do not perform episiotomy, the perineum is difficult to suture. With an episiotomy, the scar will be very nice. Cambodian women do not like it when their perineum is not aesthetically pleasing. They are not happy if the perineum is ‘deformed’ and next time they will look for another doctor to deliver them.” (Obstetrician No.1)

Diniz points out that many people seem to find it difficult to understand that the vulva and vagina have contractibility and that “these tissues are able to distend for birth and contract afterwards”. No pelvi-perineal therapy in the post-partum period is available in Phnom Penh. Such perineal re-education helps to strengthen the perineal muscles and is provided by midwives in many countries. The practice of routine episiotomy in Calmette hospital reflects the local belief that the perineum is vulnerable. Thus, birth practitioners have to “deconstruct and reconstruct the vagina” through episiotomy.

Moreover, according to Diniz, if women believe their sexuality will be adversely affected by a “flabby vagina” after birth and that episiotomy is a solution, they will agree to it.Citation34 This argument has also been heard in Calmette. Indeed, both the women and health workers we interviewed mentioned that the vagina had to be tight for good sex and that after a vaginal delivery it may become too large if an episiotomy is not performed. Thus, in Cambodia, a tight vagina is considered attractive. The two main reasons why women themselves said they wished a tight vagina were the fear of uterine prolapse in the future and their husband’s sexual pleasure. In Brazil, too, one of the main arguments used in favour of routine episiotomy is that vaginal delivery makes the vaginal muscles “flaccid”, compromising women’s sexual desirability.

Midwives and obstetricians repeatedly mentioned the practice of vulvo-vaginoplasty to achieve “pretty genitals and tight vagina”. Vulvo-vaginoplasty is a surgical procedure performed just after a vaginal delivery or in the following months or years, to “reshape” the vulva and the vagina. The exact biomedical term for this procedure is “perineomyoraphy”, which is simply called “perineo” by Cambodians. It is different from a hymeneoplasty, which is done to restore a woman’s virginity. Rather, it is done to tighten the perineum, by cutting and tightly sutturing the vulva, the vagina and the perineal muscles. This surgery is mostly practised – though not exclusively – in the private sector, and mostly but not exclusively on multiparas, and mostly by gynaecologists but also by some midwives. Cambodian women name it “de oy saat”, which can literally be translated as “sewn to be pretty”.

“When women have many children, sometimes they repair their perineum after giving birth through a “perineo”. Their perineum is tight and we need to perform an episiotomy if they deliver again.” (Obstetrician No.3).

Health workers report that after a “perineo”’, women can no longer deliver without an episiotomy. Thus, the practice of vulvo-vaginoplasty leads to subsequent episiotomy during the next delivery.

Conclusion

Every woman has the right to the highest attainable standard of health, which includes the right to respectful health care during pregnancy and childbirth. This includes also giving women a voice in birthing care, based on information about the need for and value of specific procedures.

Cambodia has made huge progress on decreasing the maternal mortality ratio. The country should now focus on the quality of maternity care. There is an excessive rate of episiotomy in Calmette Maternity Hospital which is not supported by research evidence and is contrary to international recommendations. WHO reports that limiting the use of episiotomy to strict indications has been done in some countries through adherence to standard protocols, training/retraining of birth practitioners, and supervision and quality improvement processes.Citation16 Another big maternity unit in Phnom Penh recently succeeded in reducing its episiotomy rates from 58% in 2010 to 16% in 2014Footnote* in these ways.

We strongly recommend the implementation of a programme to reduce the practice of episiotomy in Calmette. This recommendation has already found the agreement of the maternity unit directors. This programme should include the training of obstetricians and midwives to raise their awareness of the benefits of restrictive use of episiotomy, including evidence-based protocols that would reduce their fears of perineal tearing. Monitoring of trends in episiotomy rates would help to gather evidence of the impact of such a programme. In tandem with this, women will also need more information. We recommend setting up antenatal classes for pregnant women in Calmette. Women should be educated about the physiology of their vaginas and genitals to deconstruct some of their strong beliefs. The empowerment of pregnant and birthing women will contribute to improvements in birth practitioners’ own practices as well.

Acknowledgements

This study was part of PhD work by Clémence Schantz, supported by the Université Paris Descartes, France. We thank the hospital staff in Calmette and the Ministry of Health (National Ethics Committee) for their support. We thank Professor Tung Rathavy and Dr Prak Somaly for sharing their statistics on episiotomy in the National Maternal and Child Health Center with us. We thank Annabel Desgrées du Loû for her advice on the first version of this article.

Notes

* Statistics from National Maternal and Child Health Center, Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

References

- C. Kettle, T. Dowswell, K. Ismail. Absorbable suture materials for primary repair of episiotomy and second degree tears (review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: 2007

- G. Carroli, L. Mignini. Episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Systematic Reviews. 1: 2009

- R.L. Lede, J.M. Belizan, G. Carroli. Is routine use of episiotomy justified?. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 174(5): 1996; 1399–1402.

- I.D. Graham, G. Carroli, C. Davies. Episiotomy rates around the world: an update. Birth. 32(3): 2005; 219–223.

- A.T. Trinh, A. Khambalia, A. Ampt. Episiotomy rate in Vietnamese-born women in Australia: support for a change in obstetric practice in Viet Nam. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 91(5): 2013; 350–356. 10.2471/BLT.12.114314.

- K. Lam, H. Wong, T. Pun. The practice of episiotomy in public hospitals in Hong. Hong Kong Medical Journal. 12(2): 2006; 94–98.

- A. Joshi, R. Acharya. Perineal outcome after restrictive use of episiotomy in primigravida. Journal of the Nepal Medical Association. 48(176): 2009. http://www.jnma.com.np/jnma/index.php/jnma/article/viewFile/286/492.

- F. Hirayama, A. Koyanagi, R. Mori. Prevalence and risk factors for third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations during vaginal delivery: a multi-country study. BJOG : An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 340–7: 2012; 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03210.x.

- C.Y. Lai, H.W. Cheung, T.T. Hsi Lao. Is the policy of restrictive episiotomy generalisable? A prospective observational study. Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 22(12): 2009; 1116–1121. 10.3109/14767050902994820.

- J. Goldberg, T. Hyslop, J.E. Tolosa. Racial differences in severe perineal lacerations after vaginal delivery. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 188(4): 2003; 1063–1067.

- H.G. Dahlen, M. Ryan, C.S.E. Homer. An Australian prospective cohort study of risk factors for severe perineal trauma during childbirth. Midwifery. 23(2): 2007; 196–203.

- H. Dahlen, C. Homer. Perineal trauma and postpartum perineal morbidity in Asian and non-Asian primiparous women giving birth in Australia. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 37(4): 2008; 455–463.

- A. Dua, M. Whitworth, A. Dugdale. Perineal length: norms in gravid women in the first stage of labour. International Urogynecology Journal. 20(11): 2009; 1361–1364. 10.1007/s00192-009-0959-x.

- Royal College of Obstetricians UK. Gynaecologists. Clinical query answer produced by RCOG Library staff. https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/episiotomy---query-bank/. 2012

- CNGOF. Collège National des Gynécologues Obstétriciens L’épisiotomie. Recommandations pour la pratique clinique. http://www.cngof.asso.fr/D_PAGES/PURPC_14.HTM. 2005

- J. Liljestrand. Episiotomy for vaginal birth: commentary. WHO Reproductive Health Library. http://apps.who.int/rhl/pregnancy_childbirth/childbirth/2nd_stage/jlcom/en/index.html. 2003

- A. Eckman, R. Ramanah, E. Gannard. Évaluation d’une politique restrictive d’épisiotomie avant et après les recommandations du Collège national des gynécologues obstétriciens français. Journal de Gynécologie, Obstétrique et Biologie de la Reproduction. 39(1): 2010; 37–42.

- D. Reinbold, C. Éboue, R. Morello. De l’impact des RPC pour réduire le taux d’épisiotomie. Journal de Gynécologie, Obstétrique et Biologie de la Reproduction. 41(1): 2012; 62–68. 10.1016/j.jgyn.2011.08.006.

- P. Ith, A. Dawson, C. Homer. Quality of maternity care practices of skilled birth attendants in Cambodia. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare. 10(1): 2012; 60–67. 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2012.00254.x.

- National Institute of Statistics. Ministry of Planning. General Population Census Plan of Cambodia. 2008; UNFPA. http://www.stat.go.jp/english/info/meetings/cambodia/pdf/pre_rep1.pdf.

- J. Liljestrand, M.R. Sambath. Socio-economic improvements and health system strengthening of maternity care are contributing to maternal mortality reduction in Cambodia. Reproductive Health Matters. 20(39): 2012; 62–72. 10.1016/S0968-8080(12)39620-1.

- Department of Planning Health Information Ministry of Health, Cambodia. Health Sector Progress in 2014. March. 2015

- Organisation Mondiale de la Santé. Statistiques sanitaires mondiales 2013. 2013; OMS: Geneva. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/82056/1/9789242564587_fre.pdf.

- National Institute of Statistics Directorate General for Health ICF Macro. Cambodia Demographic and Health Survey 2014. Phnom Penh and Calverton, MD. 2015

- W. Van Lerberghe, Z. Matthews, E. Achadi. Country experience with strengthening of health systems and deployment of midwives in countries with high maternal mortality. Lancet. 384(9949): 2014; 1215–1225. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60919-3.

- P. Ith, A. Dawson, C.S.E. Homer. Women’s perspective of maternity care in Cambodia. Women and Birth. 26(1): 2013; 71–75. 10.1016/j.wombi.2012.05.002.

- J.-P. Olivier de Sardan. La Rigueur du Qualitatif: les contraintes empiriques de l’interprétation socio-anthropologique. 2008; Academia-Bruylant: Louvain-La-Neuve.

- P. Ith, A. Dawson, C.S.E. Homer. Practices of skilled birth attendants during labour, birth and the immediate postpartum period in Cambodia. Midwifery. 29(4): 2013; 300–307. 10.1016/j.midw.2012.01.010.

- B. Kudish, R.J. Sokol, M. Kruger. Trends in major modifiable risk factors for severe perineal trauma, 1996–2006. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 102(2): 2008; 165–170. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.02.017.

- A. Derks. Khmer Women on the Move. 2008; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu.

- L.S. Heng, H. Yatsuya, S. Morita. Vaginal douching in Cambodian women: its prevalence and association with vaginal candidiasis. Journal of Epidemiology. 20(1): 2010; 70–76. 10.2188/jea.JE20081046.

- J. Wheeler, D. Davis, M. Fry. Is Asian ethnicity an independent risk factor for severe perineal trauma in childbirth? A systematic review of the literature. Women and Birth. 25(3): 2012; 107–113. 10.1016/j.wombi.2011.08.003.

- World Health Organization. The prevention and elimination of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth. 2014; WHO: Geneva. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/maternal_perinatal/statement-childbirth/en/.

- S.G. Diniz, A.S. Chacham. “The cut above” and “the cut below”: the abuse of caesareans and episiotomy in São Paulo, Brazil. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(23): 2004; 100–110.