Abstract

Abstract

Although unsafe abortion continues to be a leading cause of maternal mortality in many countries in Asia, the right to safe abortion remains highly stigmatized across the region. The Asia Safe Abortion Partnership, a regional network advocating for safe abortion, produced an animated short film entitled From Unwanted Pregnancy to Safe Abortion to show in conferences, schools and meetings in order to share knowledge about the barriers to safe abortion in Asia and to facilitate conversations on the right to safe abortion. This paper describes the making of this film, its objectives, content, dissemination and how it has been used. Our experience highlights the advantages of using animated films in addressing highly politicized and sensitive issues like abortion. Animation helped to create powerful advocacy material that does not homogenize the experiences of women across a diverse region, and at the same time emphasize the need for joint activities that express solidarity.

Résumé

Même si l’avortement à risque demeure une cause majeure de mortalité maternelle dans beaucoup de pays d’Asie, le droit à un avortement sûr reste un fort motif de stigmatisation dans l’ensemble de la région. L’Asia Safe Abortion Partnership, réseau régional qui plaide pour un avortement sans risque, a produit un film d’animation intitulé « D’une grossesse non désirée à un avortement sûr ». Ce court métrage peut être diffusé dans des conférences, des écoles et des réunions pour partager les connaissances sur les obstacles à un avortement sûr en Asie et faciliter les conversations sur le droit à un avortement sans risque. L’article décrit la réalisation du film, ses objectifs, son contenu, sa diffusion et l’utilisation qui en a été faite. Notre expérience montre les avantages de l’emploi de films animés pour aborder des questions extrêmement politisées et sensibles comme l’avortement. L’animation a créé un matériel de plaidoyer efficace qui n’homogénéise pas les expériences des femmes à travers une région diverse tout en soulignant la nécessité d’activités conjointes qui expriment la solidarité.

Resumen

A pesar de que el aborto inseguro continúa siendo una de las principales causas de mortalidad materna en muchos países de Asia, el derecho al aborto seguro continúa siendo muy estigmatizado en toda la región. La Alianza Asiática por el Aborto Seguro, una red regional que aboga por el aborto seguro, produjo un cortometraje animado titulado “Desde el embarazo no deseado hasta el aborto seguro” (From Unwanted Pregnancy to Safe Abortion) para mostrarlo en conferencias, escuelas y reuniones, con el fin de compartir los conocimientos sobre las barreras para obtener servicios de aborto seguro en Asia, así como para facilitar conversaciones sobre el derecho al aborto seguro. En este artículo se describe la producción de este cortometraje, sus objetivos, contenido, difusión y cómo ha sido utilizado. Nuestra experiencia destaca las ventajas de utilizar películas animadas para abordar temas muy politizados y delicados como el aborto. La animación ayuda a crear material influyente que no homogeneiza las experiencias de las mujeres en una región diversa, y a la vez hace hincapié en la necesidad de llevar a cabo actividades conjuntas que expresen solidaridad.

Introduction

Asia is the most highly populated region in the world, and records a high rate of unsafe abortions. Studies show that while fertility rates in Asia have declined in the last ten years,Citation1 the rate of unintended pregnancy continues to be as high as 49 per 1,000 women aged 15–44.Citation2 The rate of induced abortion is Asia is 28 per 1,000 women aged 15–44Citation3 and around a third of these women (10.8 million) have unsafe abortions annually.Citation4 These rates are highest in South Central Asia (65% of abortions are unsafe),Citation5 while in East Asia, almost all abortions are safe.Citation6 Studies show that two out of five Asian women with an unmet need for safe abortion are under 25 years of age ().Citation7

Figure 1 Clip from From Unwanted Pregnancy to Safe Abortion showing women using back alley abortions when barriers are erected in their path. The image shows women from various countries to emphasise that the issue of unsafe abortion happens all over Asia.

Although unsafe abortion continues to be a leading cause of maternal mortality in many countries in Asia, the right to safe abortion remains highly stigmatized across the region. This stigma is reflected in restrictive laws, the lack of trained providers and the general lack of awareness of the laws on abortion, which drives large numbers of women to unsafe abortion.Citation8 As a regional network promoting the right to safe abortion, the Asia Safe Abortion Partnership (ASAP) has to address the lack of access to safe abortion both as a transnational phenomenon and as a highly localized experience. In order to increase knowledge about specific barriers to safe abortion through educational materials for its regional advocacy, ASAP funded the making of an animated short film entitled From Unwanted Pregnancy to Safe Abortion.

This film addresses the various barriers to safe abortion that the Partnership and its partner organizations in 20 countries across the Asia-Pacific and Middle East encounter in their everyday work. These countries have extremely diverse abortion laws. While a greater number of safe abortions occur in countries where abortion is legal, abortion stigma and negative attitudes towards abortion can still drive women to unsafe abortion even in these countries. India is a good example of a country where abortion access has suffered from conservative interpretations of an otherwise liberal law.Citation9 In fact, studies show that only two-fifths of abortions in India are safe and legal.Citation10 To understand this phenomenon better, ASAP conducted a study in seven countries across Asia to assess attitudes to abortion and knowledge of the abortion law among those who act as gatekeepers to the law and its implementation. The studyCitation11 found misconceptions and a dearth of information even among these key stakeholders,Footnote* as well as limited recognition of the importance of international covenants and the understanding of safe abortion as a right. ASAP recognized the need to create a self-contained message that could provide essential knowledge about abortion and facilitate conversations around the need to understand a rights-based approach.

The idea for creating such a film also grew from the Partnership’s advocacy and capacity-building workshops. ASAP is committed to improving knowledge about safe surgical and medical abortion, and has conducted trainings and workshops since 2008 for various stakeholders, ranging from the media and policymakers to health care providers, such as doctors, nurses and midwives. Since 2012, it has also conducted an annual Advocacy Institute for young activists across Asia. ASAP is also a co-founder and promoter of the International Campaign for Women’s Right to Safe Abortion and has supported activities conducted under the umbrella of the Campaign across Asia. Through its advocacy and training work, ASAP aims to highlight that the lack of access to safe abortion is both a public health and social justice concern and a human rights violation. In order to address the lack of awareness about the laws on abortion in the region, the Partnership has also curated legal information in its member countries, which can be found on our website.Footnote† Through the film, ASAP sought to enhance its work and create a tool that would introduce the context within which abortion in Asia must be understood, both in its trainings and in its advocacy work. This paper examines the making of this film, its objectives and distribution and how it has been used, in order to highlight the advantages of using animated films in addressing highly politicized and sensitive issues like abortion.

Conception

Films are increasingly being used for local, national and transnational advocacy.Citation12 Animation has been seen as a potential tool for advocacy since UNICEF used it in the late 1960s.Citation13 Since real-life images can fatigue or even desensitize the viewer when they have been exposed to similar images very often, organizations have turned to animation to create more captivating and engaging visual material for advocacy.Citation14 Recognizing our own need to produce an advocacy and training tool that would address the issue of unsafe abortion in Asia, ASAP explored the option of making a film. The animated video Why Did Mrs X Die, Retold Footnote‡ inspired us to employ animation in disseminating information about safe abortion.

In 2012, when the World Health Organization released the animated film Why Did Mrs X Die, Retold in order to emphasize the need for continuing conversations around preventable maternal deaths, ASAP was inspired to create a similar film around the topic of abortion. Why Did Mrs X Die tells the story of a woman whose life is threatened because of complications arising from her pregnancy. The film explores how timely access to medical attention or the lack thereof could affect her life. The use of animation allows the viewer to explore the options with some flexibility, and plot the various paths down which Mrs X could have progressed, had she had access to information and health care. The movie’s potential to educate its audience and share vital information was obvious.

Both the WHO film and our own are similar in so far that they address preventable maternal deaths. Why Did Mrs X Die succeeds in making this issue seem less like a statistical detail and more like a social issue that impacts the lives of individual women. It does this by introducing a character called Mrs X and talking about maternal morbidity and mortality through her experience. This allows the audience to relate to her and empathize with her medical needs. Similarly, From Unwanted Pregnancy to Safe Abortion tells the story of Ms A, who is in need of an abortion, and explores her options in various countries around Asia. This movie too attempts to put a face to the issue and seeks to portray abortion as a personal issue that affects the lives of individual women and girls who collectively constitute the maternal health statistics.

However, From Unwanted Pregnancy to Safe Abortion is a departure from Why Did Mrs X Die on several other counts. Why Did Mrs X Die tells the story of women whose pregnancies could be assumed to occur within the institution of marriage, as the title ‘Mrs’ is assigned to the protagonist. But in seeking to tell stories of women experiencing an unwanted pregnancy, we felt it important to include pregnancies that occur both within and outside of marriage, so we chose to use the less specific title ‘Ms’ for the protagonist. The ASAP film also attempts to show that the demographic it represents is diverse. The nine-minute narrative introduces many different women with different ethnicity, age and socio-economic class. Through their collective experience, the film seeks to highlight that stigma and lack of access are widespread phenomena that cut across countries, class, marital status, race and age; through each woman’s country-specific experience, it seeks to underline localized tensions across Asia.

Animation was chiefly adopted because of the flexibility it lent to the narrative in Why Did Mrs X Die, allowing the makers to plot Mrs X’s options visually. The ASAP film also benefits from animation but also for another reason. While the narratives ASAP comes across in its workshops and in the reports of its partners have influenced the script, these narratives cannot be captured on film for fear that the women, the health care providers and others might be identified and threatened. It was therefore safer to tell these stories and address these barriers through different Ms As. While on the one hand their presence allows the film to humanize the issue, it also helps to protect the identities of the real women who have shared their stories, which are the basis of the film.

The authors of this paper developed the concept and prepared the story board for the film. The script was written and narrated by the first author. US-based Indian artist Shachi Kale did the artwork used in the film. The film was edited by the first author, with inputs from the second author throughout the process. The funds for production and distribution were provided by the Asia Safe Abortion Partnership.

Objectives

The film was conceived as a stand-alone tool to introduce abortion in the Asian context for ASAP’s advocacy and training programmes, but it also has other purposes.

Firstly, the film shows that deaths from unsafe abortions are most often preventable. The film explores various sociocultural and legal factors, and their interrelationship with laws and practices, to outline the complexities that permit access to safe abortion or force women to seek unsafe abortions. It then shows how these barriers can be addressed, to portray how unsafe abortion can be prevented and safe abortion made a reality in the lives of women. In addition to this, the film aims to show that unsafe abortion is an issue that affects relationships and entire families and is not only a woman’s problem. The loss of a woman’s life impacts the lives of those who depend on her, while her health and well-being allow her to become/remain a productive member of the family and society at large. In making this argument the makers also simultaneously argue for the need to empower women within families and communities.

The film also highlights Ms A’s agency, by portraying her, in each of her avatars, as a proactive person, who constantly negotiates her choices and seeks empowerment by exploring the options made available to her through activism, advocacy and changes in law and policy. It portrays safe abortion as a woman’s right and shows that it has an impact on all subsequent life choices such as education, employment and a woman’s ability to establish her independence.

The film also underlines the need for communities to come together and support women in their journey towards a more equal life. The script not only talks of the many Ms As, who seek abortion services, but also of the community that will either act as a barrier or facilitate their having a safe abortion and moving on. In situating women’s reproductive choices within their homes and communities, this film aims to show that these choices are complex and often dependent on multiple factors. Thus, access to safe abortion is a constant negotiation between women and their families, their communities and their countries. Thus, the film emphasizes not only the need to empower women as decision-makers, it also stresses the need to build and foster a supportive community as well as the duties of the State towards women.

Making the film: scripting and editing

The script is divided into three self-contained blocks: the first introduces safe abortion as a public health and human rights concern; the second introduces the viewer to the many Ms As and shows how specific barriers affect their life; the third introduces the viewer to specific ways in which these barriers can be addressed. Each of these blocks can be viewed independently. This allows ASAP to use each of them as shorter versions during its workshops.

The first block presents public health information to educate the viewer about abortion in Asia. It uses numbers and statistics to show the burden of unsafe abortion as part of maternal deaths and morbidity.

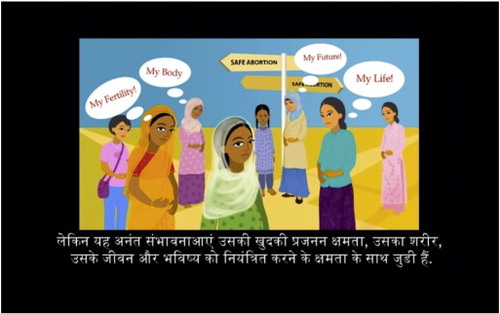

The second block introduces the audience to different avatars for Ms A, whose experiences of safe and unsafe abortion vary depending on their age, class, nationality and ethnicity. While ASAP’s work spans 20 countries in the region, including 20 different Ms As might have created confusion. The film therefore shows only nine Ms As. Six of them represent the ethnic diversity in Asia (2 for South Asia, 3 for South East Asia and 1 for the Middle East.) One Ms A is a young girl, representing adolescents who need abortions. While she is sketched as a South Asian, she is used in the film where the script addresses the age of the person seeking abortion, not their ethnicity. Similarly, two additional Ms As were sketched to show women who represent different socioeconomic classes. One of them was styled to represent college-going students, the other to represent working women. Through these images, and in the way they are used alongside each other, the film narrates the different contexts in which women seek abortion, and shows how safe abortion must be an unconditional right – irrespective of women’s reasons and contexts ().

Figure 2 Clip from From Unwanted Pregnancy to Safe Abortion showing on the left a woman wanting an abortion and on the right a helpline counsellor giving advice on how to use misoprostol for safe abortion.

Figure 3 Clip from From Unwanted Pregnancy to Safe Abortion showing women from around Asia making a demand for safe abortion.

Though the film has nine Ms As, the script depicts personal experiences of individual women and therefore uses the singular pronoun ‘her’ very often. The scenes however fade into one another or are juxtaposed on two halves of the screen to allow the viewer to appreciate similarities and differences between these personal experiences, and create a collective narrative.

The artist also sketched eight background images and several supporting characters to contextualize the women’s experiences of abortion in the community. Through these characters and background images, the film aims to highlight the fact that barriers to safe abortion need to be understood in relation to the local context where they are produced and experienced, but also addressed as a transnational phenomenon.

The second block is divided thematically into three sub-sections:

| 1. | The first takes the audience into Ms A’s home, where we see her in relation to her marital and natal families. The film explores a pregnancy that occurs within a marriage while a woman is living in her marital home, and another that occurs outside of marriage while a woman is living in her natal home. It then explores how gender complicates her relationships with the people around her and also affects her financial independence. It talks about the role of her partner in facilitating or preventing the use of suitable methods of contraception. It shows how family members can often act as a barrier unless they understand the complex social realities that the woman is forced to face. It also explores how patriarchy and patriarchal themes like family honour and shame engender stigma that drives her to unsafe abortion. | ||||

| 2. | The film then takes the audience into the health care system, exploring how the attitudes of doctors, the out-of-pocket costs of health care and the complex referral systems often complicate access to safe abortion. | ||||

| 3. | The film finally looks at the relationship between the woman and her country, and explores the complex relationship between traditional gender biases, stigma and the law. It specifically explores barriers to second trimester abortions. | ||||

After this, the film goes into the third block, where it discusses transnational and national processes that can be used to advocate for more liberal laws and for the liberal interpretation of existing laws. The film also addresses the need to adopt a rights-based language in order to address gender inequality and social stigma. It also highlights the work of non-profits, particularly those of ASAP’s partner organizations who run hotlines in Bangladesh, Indonesia, Pakistan and Thailand to provide accurate information about the use of misoprostol for safe abortion ( ).

Lastly, there was a conscious decision to produce a script that would speak to a lay audience who might come across this film on social media. The script therefore avoids using technical terms, and explains Ms A’s problems, choices and negotiations in simple, non-technical language.

The original film was made in English and was produced in two phases. The first phase was completed in time to be shown during Women Deliver, May 2013, and a selected group of ASAP’s regional and international partners were invited to provide feedback on the content. Based on their comments, the films was adapted to include more avatars for Ms A, provide more detailed information about medical and surgical abortions, and thoroughly explore the legal barriers to safe abortion. For example, the feedback helped the film-makers to make a distinction between countries where laws are stringent due to the religion and the State functioning together (e.g. Iran, Philippines) and countries where laws are liberal but access is still affected by various barriers (e.g. India, Malaysia.) The second phase of editing was completed in November 2013, and the film was published on 25 November 2013 on YouTube and CD.

Distribution and impact

ASAP initially released a statement about the release of the film on its blog,Footnote§ and then distributed the links to the film along with this statement. Since then, we have distributed the film over YouTube and on ASAP’s social media pages (Facebook, Twitter). It was also shared with selected partners, donors and on other forums, such as listserves, and publicised through the International Campaign’s e-newsletter. The film has been watched 4,900 times to date on YouTube. The total reach has been much greater, however, through ASAP’s social media pages.Footnote**

During production, the makers aimed to create a film that would have the capacity to educate and initiate discussions amongst a select audience in trainings and capacity-building workshops on advocacy. The film, we thought, could provide the facilitators with a tool for further advocacy, and allow them to illustrate the context in Asia with ease in their own advocacy work. Thus, ASAP has used the film in its Youth Advocacy Institutes (2012, 2013, 2014) to introduce youth advocates to the issue of abortion in Asia. These young advocates were interested in showing the film to members of their youth networks, and in order to make it more accessible, some of them offered to translate the script so that local language subtitles could be added to the film.

With their help, and that of ASAP’s Steering Committee members, the subtitles were translated into Arabic, Hindi, Nepali, Sinhalese and Vietnamese.Footnote†† These versions of the film are also distributed through YouTube and on CD, which the youth advocates have distributed in their local advocacy work (e.g. workshops conducted by the Bhaktapur Youth Information Forum in Nepal) and in international conferences they have attended (e.g. World Youth Conference, Sri Lanka, May 2014). A total of 2,500 DVDs have been distributed at international events and through ASAP’s youth networks.

The original in English plus the Asian language versions are available on YouTube as follows:

Sinhalese: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z7nQPyNGYI

Vietnamese: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z9OmR0sfeVA

While maternal health is a broadly discussed topic, abortion is often marginalized even in conferences and conventions on family planning and maternal mortality. The film was written such that it can serve as a self-contained, short introduction to the problem of unsafe abortion, and begin conversations on a stigmatized topic with ease. Shortly after its release in November 2013, the first author was invited to speak at a bioethics conference at the Indian Institute of Technology Madras (IIT Madras, India). The conference’s aim was to explore the significance and meaning of the word “life” in ethical debates that crosscut law and medicine. The film helped the first author introduce the human rights and ethical issues around access to safe abortion, show why feminist debates were necessarily within the realm of bioethics, and why personification of the fetus could present problems for women and affect the quality of their lives. The film gave rise to several interesting debates, including debates on upper time limits for abortions, barriers in second trimester abortions, and safe abortion access for young girls and older women.

The film was also featured in two sessions at the 7th Asia Pacific Conference on Reproductive and Sexual Health and Rights in Manila, Philippines, in January 2014. The first session was part of a panel entitled, Unsafe Abortion – Not Merely A Number, where the second author used the film to emphasize the need for conversations to contextualize the localized tensions but also relate them to the broader regional conversation, in order to gain solidarity and build a stronger movement for safe abortion in Asia. In the second session, SRHR in Social Media, the first author spoke about the importance of producing advocacy material that presents the issue in a humanized way. The film was featured in a news article about the conference.Citation15 This article highlighted the content of the film, and the broader idea of using animation to address such sensitive and stigmatized issues. This was a triumph particularly because local Catholic organizations were opposed to the discussion of abortion in the conference. The film helped gain some positive attention for safe abortion in the face of their animosity.

Challenges encountered

During the distribution of the film, ASAP encountered two challenges: representation of second trimester abortions and language issues.

Representation of second trimester abortions

The discourse on abortion is often situated within political debates that stigmatize the act of abortion, and often marginalize certain abortions within the wider discourse. Debates on upper time limits for abortion tend to position second trimester abortions as a grey area. While the film specifically seeks to address such stigma through a specific segment on second trimester abortions, some reviewers felt that the inclusion of second trimester abortion would dampen the reception to abortion as a whole.

In particular, a decision made regarding the size of the abdomen during the making of the film has been challenged by a few viewers. During the making of the film, ASAP decided to make the women seem obviously pregnant, so the size of Ms A’s abdomen does not correspond with the number of weeks of her pregnancy. While she displays a smaller abdominal protuberance in the first trimester, the protuberance is exaggerated to demonstrate second trimester pregnancies. ASAP’s aim was to make sure that someone who randomly came across the film would connect it with a second-trimester pregnancy as soon as they saw even one frame of the film. The visual cue was therefore prioritized over scientific accuracy.

However, two doctors in India and one from Viet Nam objected to this, as they believed this visual cue could provoke women to seek later and later abortions, increasing the number of women who delayed the decision during their first trimester and sought abortions during their second trimester.

While ASAP acknowledges these concerns, we did not receive similar feedback from other health care providers or from activists who have watched this video. In fact, some of the initial feedback received after phase one of the video congratulated the organization for not shying away from second trimester abortions. Others asked us to expand that section, which we did in the final version of the film. So while the organization acknowledges the fact that the images are not accurate from a scientific standpoint, it also would like to stand by its original decision to use an exaggerated abdominal size as it seems to have worked as intended for most people. The organization also felt that since this film is meant to advocate for the right to safe abortion, rather than provide information on the legal limits set by countries, it is not necessarily misleading. Instead the organization believes that these statements of discomfort about second abortion could be used for discussions in workshops and trainings. While the first author was able to address this discomfort in the bioethics talk at IIT Madras, the organization can explore this potential more in its trainings and workshops.

Language

Some issues the film deals with have roots in localized cultural values; others have been introduced through global feminist discourses. The words and terms used, sometimes newly coined, are often difficult to translate into local languages. The title ‘Ms’ is quite recent even in the English-speaking world and could not be translated into the Asian languages we used. The titles used for older women in those languages almost always indicated that they were married, while those used for unmarried women seemed to connote that they were very young. Similar problems arose for words like “gender” and “sexuality”. Very often, the vernacular terms closest in meaning to the English alternative were used for this film. However, the organization understood that it would be necessary to come up with local terms that would introduce these cultural ideas without making them seem too foreign or alien. This would have to be a long-term project, outside the scope of this project. However, the film helped to identify some specific linguistic challenges for feminist advocacy in these local languages.

Conclusion

From Unwanted Pregnancies to Safe Abortion was made primarily for the purpose of addressing abortion stigma and creating a tool for ASAP and partners to help to ease people into conversations on the problems presented by unsafe abortion and the need to advocate for the right to safe abortion in their trainings and workshops. The film was produced on a shoestring budget and distributed on free social media platforms. The popularity of the film among ASAP’s youth advocates and the use of the film in subsequent workshops conducted by them shows that the film is able to serve the purpose it was created for.

The making of the film, particularly its conception and scripting, have led us to believe that animation has the potential to create appealing films that humanize a cause while protecting the identity of the sources. The popularity of the film in the Youth Advocacy Institutes suggest that this medium particularly appeals to a young generation and can be explored for creating further advocacy material.

Feedback received shows that the medium and the presentation were interesting to health care providers as well. Some of them suggested that a film on post-abortion care be made as a sequel to this film in order to address the issues of access to PAC in countries such as Pakistan and Afghanistan where access to safe abortion is restricted but PAC is legal.

While creating Ms A, ASAP also realized the potential to tell stories that focus simultaneously on localized contexts as well as the larger regional implications of such stories. This helps to create powerful advocacy material that does not homogenize the experiences of women across a diverse region, but at the same time has the capacity to emphasize the need for joint activities that express solidarity on sensitive issues like abortion.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the grant received through the ASAP Small Grant Programme. The production costs and dissemination costs were covered from this grant.

Notes

* The study was conducted in India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines and Sri Lanka. While a majority of the stakeholders across the region did not seem to be fully aware of the abortion laws and policies in their countries, their attitudes and misconceptions depended to a large extent on the country they came from and local attitudes towards abortion in that country. Stakeholders in India, Indonesia and Nepal largely supported the view that abortion was a woman’s right. However, in Malaysia, Pakistan, Philippines and Sri Lanka, a majority of the stakeholders held the view that abortion was in conflict with their religious beliefs. While a number of them agreed that abortion could be permitted for public health reasons, they were not of the view that it could be considered a woman’s right.11.

‡ Why Did Mrs X Die, Retold is a remake of the 1988 World Health Organization film Why Did Mrs X Die. This film was produced to educate midwives, health workers and key stakeholders about the complications of pregnancy, and of pregnancy-related mortality. WHO remade this film in 2012 because the key issues had not changed for so many women in spite of progress made between 1988 and 2012.

** Unfortunately, ASAP’s social media were hacked at the time this article was being written, resetting the tools used for measuring the number of posts shared on these platforms. We can therefore only indicate this success anecdotally.

†† We originally intended to include a Farsi version, but this had to be postponed indefinitely for technical reasons. Translations into the other languages proceeded smoothly.

References

- M.J. Abbasi-Shavasi, B. Gubhaju. Different Pathways to Low Fertility in Asia: Pathways, Consequences and Policy Implications. Proceedings from the UN Expert Group Meeting on Fertility, Changing Population Trends and Development: Challenges and Opportunities. 2013; United Nations, Population Division: New York. (http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/events/pdf/expert/21/2013-EGM_Mohammad%20Jalal%20Abbassi-Shavazi%20&%20Bhakta%20Gubhaju.pdf).

- Guttmacher Institute. Rates of unintended pregnancies remain high in developing regions, 2011. Digest. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 37(1): 2011; 10.2307/41202971. (http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/journals/3704611.html).

- World Health Organization. Information Sheet – Safe and unsafe induced abortion, global and regional levels in 2008, and trends during 1995–2008. 2012; WHO: Geneva. (http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75174/1/WHO_RHR_12.02_eng.pdf).

- World Health Organization. Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2008. 2012; WHO: Geneva10.1016/50140-6736(11)61786-8. (http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241501118_eng.pdf).

- G. Sedgh, S. Singh, S.K. Henshaw. Induced abortion: incidence and trends worldwide from 1995 to 2008. Lancet. 379(9816): 2012; 625–632. 10.1016/S0140-6763(11)61786-8. (http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/journals/Sedgh-Lancet-2012-01.pdf).

- Guttmacher Institute. Facts on abortion in Asia. 2012; GI: New York. (https://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/IB_AWW-Asia.pdf).

- Population Review Bureau. Abortion – facts and figs. 2011. 2011; PRB: Washington, DC. (http://www.prb.org/pdf11/abortion-facts-and-figs. 2011.pdf).

- M. Berer. Making abortions safe: a matter of good public health policy and practice. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 7((5): 2000; 580–592. 10.1016/S0968-8080(02)00021-6. (http://www.who.int/bulletin/archives/78(5)580.pdf).

- A. Jesani, A. Iyer. Women and abortion. Economic and Political Weekly. 28(48): 1993; 2591–2594. (http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Aditi_Iyer/publication/11694690_Women_and_abortion/links/00b7d52955cb430dca000000.pdf).

- Guttmacher Institute. Facts on abortion in Asia. https://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/IB_AWW-Asia.pdf. 2012

- Asia Safe Abortion Partnership. A study of knowledge, attitude and understanding of legal professionals about safe abortion as a woman’s right. Country reports for: India (http://asap-asia.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/India_Abortion_Booklet_Update.pdf), 2009. Indonesia (http://asap-asia.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Indonesia_Abortion_Booklet_Update.pdf), 2009. Malaysia (http://asap-asia.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Malaysia_Abortion_Booklet_Update.pdf), 2009. Nepal (http://asap-asia.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Nepal_Abortion_Booklet_Update.pdf), 2009. Pakistan (http://asap-asia.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Pakistan_Abortion_Booklet_Update.pdf), 2009. Philippines (http://asap-asia.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Philippines_Abortion_Booklet_Update.pdf), 2009. Sri Lanka (http://asap-asia.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Sri_Lanka_Abortion_Booklet_Update.pdf ), 2009.

- S. Gregory. Transnational storytelling: human rights, WITNESS, and video advocacy. American Anthropologist. 108(1): 2006; 195–204. 10.1525/aa.2006.108.1.195. (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1525/aa.2006.108.1.195/abstract).

- D. Blackall. Drawing insight – communicating development through animation. Book review, Asia Pacific Media Educator. 1(1): 1996; 162–164. (http://ro.uow.edu.au/apme/vol1/iss1/16).

- K.L. Katfiekd, A. Hinck, M.J. Birkholt. Seeing the visual in argumentation: a rhetorical analysis of UNICEF Belgium’s Smurf Public Service Announcement. Argumentation and Advocacy. 43: 2007; 144–151. (https://www.academia.edu/778719/Seeing_the_Visual_in_Argumentation_A_Rhetorical_Analysis_of_UNICEF_Belgiums_Smurf_Public_Service_Announcement).

- Majumdar Swapna. Philippine sex ed comes via video and text message. 2013; We.News, Reproductive Health. (http://womensenews.org/story/reproductive-health/140331/philippine-sex-ed-comes-video-and-text-message.