Abstract

Although Chile is a traditionally conservative country, considerable legal advances in sexual and reproductive rights over the past decade have brought discourses on sexuality into mainstream political, social and media agendas. In light of these changes it is important to explore how adolescents conceptualize sexuality, which in turn influences their understanding of sexual rights. This study is based on four focus group discussions and 20 semi-structured interviews with adolescents, and seven interviews with key informants in Santiago, Chile. Findings indicate that adolescent conceptualizations of sexuality are diverse, often expressed as attitudes or observations of their social context, and primarily shaped by peers, parents and teachers. Attitudes towards individuals with non-heterosexual orientations ranged from support to rejection, and conceptualizations of sexual diversity were also influenced by media, medicalization and biological explanations. Gender differences in sexual expression were described through gendered language and behaviour, in particular observations of gender stereotypes, censored female sexuality and discourses highlighting female risk. Many adolescents described social change towards greater equality regarding gender and sexuality. To optimize this change and help bridge the gap between legal and social recognition of sexual rights, adolescents should be encouraged to reflect critically on issues of gender equality and sexual diversity in Chile.

Résumé

Bien que le Chili soit un pays normalement conservateur, les progrès juridiques considérables des droits sexuels et génésiques ces dix dernières années ont placé les discours sur la sexualité à l’ordre du jour politique, social et médiatique. Face à ces changements, il est important d’analyser comment les adolescents conceptualisent la sexualité, ce qui influence leur compréhension des droits sexuels. Cette étude est fondée sur quatre groupes de discussion et 20 entretiens semi-structurés avec des adolescents, et sept entretiens avec des informateurs clés à Santiago (Chili). Les conclusions indiquent que les conceptualisations de la sexualité chez les adolescents sont diverses, souvent exprimées comme attitudes ou observations de leur contexte social, et principalement façonnées par les pairs, les parents et les enseignants. Les attitudes envers les individus aux orientations non hétérosexuelles allaient du soutien au rejet, et les conceptualisations de la diversité sexuelle étaient aussi influencées par les médias, la médicalisation et les explications biologiques. Les inégalités sexospécifiques dans l’expression sexuelle étaient décrites par un langage et des comportements sexués, en particulier les observations des stéréotypes sexospécifiques, la sexualité féminine censurée et les discours mettant en lumière les risques pour les femmes. Beaucoup d’adolescents ont décrit le changement social vers une plus grande égalité concernant le genre et la sexualité. Pour optimiser ce changement et aider à combler le fossé entre la reconnaissance juridique et sociale des droits sexuels, les adolescents doivent être encouragés à réfléchir de manière critique aux questions d’égalité entre les sexes et de diversité sexuelle au Chili.

Resumen

Aunque Chile es un país tradicionalmente conservador, en la última década considerables avances legales en derechos sexuales y reproductivos han puesto los discursos sobre sexualidad en las agendas políticas, sociales y en los medios de comunicación. En vista de estos cambios, es importante explorar cómo los adolescentes conceptualizan la sexualidad, lo cual a su vez influye en su comprensión de los derechos sexuales. Este estudio se basa en cuatro discusiones de grupos focales y 20 entrevistas semiestructuradas con adolescentes, y siete entrevistas con informantes claves en Santiago de Chile. Los resultados indican que las maneras en que los adolescentes conceptualizan la sexualidad son diversas, a menudo expresadas como actitudes u observaciones de su contexto social y principalmente definidas por pares, padres y profesores. Las actitudes hacia personas con orientaciones no heterosexuales variaron desde apoyo a rechazo, y las conceptualizaciones de la diversidad sexual también fueron influenciadas por los medios de comunicación, medicalización y explicaciones biológicas. Las diferencias en cómo se expresa la sexualidad según genero fueron descritas por medio de lenguaje y comportamiento de hombres y mujeres, en particular observaciones de estereotipos de género, sexualidad femenina censurada y discursos que destacan el riesgo de la sexualidad femenina. Muchos adolescentes describieron el cambio social como mayor igualdad de género y sexualidad. Para optimizar este cambio y ayudar a reducir la brecha entre el reconocimiento legal y social de los derechos sexuales, se debe motivar a los adolescentes a reflexionar críticamente sobre los temas relacionados con la igualdad de género y la diversidad sexual en Chile.

Background

Sexuality is a central component of human life.Citation1 Definitions of sexuality tend to be broad and include “sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, eroticism, pleasure, intimacy and reproduction” Citation1 and “ideals, desires, practices, preferences and identities”.Citation2 Sexuality is regulated by sociocultural norms, beliefs, morals and taboos, and “policed by a large range of religious, medical, legal and social institutions”.Citation3 In most societies religion is the central agent in sex regulationCitation3 and in the Latin American context, the Catholic Church remains the central opponent to full recognition of sexual and reproductive rights.Citation4 The influence of religion is most visible in countries with policies surrounding the criminalization of abortion, denial of reproductive services to unmarried adolescents, restrictions on provision of comprehensive sex education, and discrimination against individuals with non-heterosexual orientations.

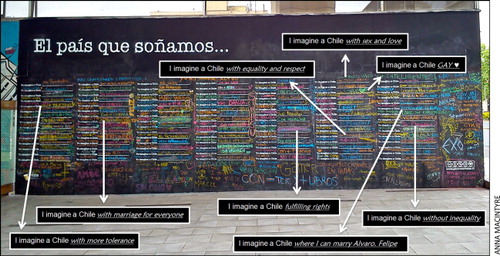

Globalization of sex, sexual identities and sexual rights contribute towards dissolving the distinction between public and private behaviours, often creating tensions between global and local discourses on sexuality and sexual rights.Citation3 In Chile, these global-local tensions are visible in reports published by international human rights organizations criticizing inadequate protection of sexual and reproductive rights by the Chilean State.Citation5 Although important, global pressure alone is not enough to accomplish lasting change on the local level without support from civil society networks and organizations within a country.Citation6 In Chile, local non-governmental organizations such as Fundación Iguales (Equality Foundation) and Movimiento para la Integración y Liberación Homosexual (Movement for Homosexual Integration and Liberation) are examples of civil society organizations promoting sexual rights.

Sexual rights are intrinsically linked to sexual politics. In Chile, the years immediately following the return to democracy in 1990 were characterized by cautious coalition governing.Citation7 During this period there was strong opposition to discussing sexual and reproductive rights issues seen to pose a risk to the fragile political power balance.Citation7,8 This opposition has also been linked to key positions of power held by conservative religious politicians and political supporters in the post-dictatorship period.Citation4,7,8

The mid 2000s brought a significant shift in political will to tackle issues of gender and sexual rights in Chile. These include: legalization of divorce in 2004; a legal decree in 2005 that explicitly stipulates the educational rights of pregnant and mothering students;Citation9 passing of a law in 2010 guaranteeing access to emergency contraception and sex education; inclusion of sexual orientation in the 2012 anti-discrimination law and passing of a civil union bill in 2015.Footnote* Although these advances are highly significant, issues still remain, with decriminalization of abortion perhaps the most controversial. Casas and VivaldiCitation10 state that Chile is currently at a crossroads regarding abortion law reform, with the most recent attempt plausibly ending 24 years of criminalization and failed efforts at reform.

Although Chile is experiencing considerable political and legal change in relation to gender equality and sexual and reproductive rights, questions remain as to the extent legal and political changes reflect a substantial shift in cultural and social conceptualizations of gender and sexuality. In light of these political and legal changes, it is interesting to investigate social change through an exploration of how adolescents conceptualize sexuality, which in turn has implications for their understanding of sexual rights.

Adolescence is a period of considerable development, characterised by exploration, experimentation and discovery.Citation1 During this time, numerous socializing agents play a part in shaping individual sexuality, including family, peers, education, religion, media and medicine.Citation11,12 Youth must negotiate information about sexuality that they receive from a multitude of sources, from parents, teachers and friends, to pornography and commercial marketing. Thus, what they understand as good or bad, healthy or unhealthy, acceptable or unacceptable sexuality will be shaped by their unique social context.

This paper reports on findings from a wider study with the main objective of exploring sources of information and adolescent learning about sexual health and sexuality in Santiago, Chile. The word “information” is understood in a wide sense to include seemingly objective information presented in the form of facts and organized sex education curricula, as well as the more subjective information presented through attitudes, opinions and observable behaviours. “Learning” is understood broadly as a process that is formal and informal, active and passive, and both an individual and group process guiding development of attitudes, opinions and behaviours.

Methods

Data was collected from September to December 2013 and included focus group discussions and semi-structured interviews. The first author conducted all interviews and discussions in Spanish. However, as she is not a native Spanish speaker, an interview team was created with a local research assistant. The assistant was present during all adolescent interviews and discussions, taking notes, keeping time, clearing up language misunderstandings and explaining culturally specific concepts or terminology. All discussions and interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. For a more detailed description of research methods see Macintyre, Montero Vega and Sagbakken.Citation13

Initial pilot interviews with two university students and two focus group discussions in a public high school provided opportunities to practice interview techniques and tailor interview guides to the Chilean context. After completion of the individual interviews, a further two focus group discussions were held with anthropology students at a public university to discuss the preliminary findings and emerging themes. These discussions also provided valuable opportunities to observe the way in which adolescents discussed the topic of sexuality in a peer group setting. A total of 24 adolescents 18-19 years old participated in the four gender-separated focus group discussions: seven females and seven males in the high school focus groups and five females and five males in the university focus groups. Participants were sampled using homogenous sampling to limit variation and promote open communication in a safe environment, and opportunistic sampling in response to poor participant attendance on the days scheduled for discussions in the high schools.Citation14

In total, 20 individual semi-structured interviews were conducted with adolescents 16-19 years old recruited from three high schools in the Santiago municipalities of Independencia, Recoleta and Las Condes. The purpose of sampling in different schools was to encourage maximum variation as schools differed in size, religiosity (one Catholic school and two secular schools), academic focus, sex education programs and socioeconomic status of pupils.Footnote† Although maximum variation was the main sampling approach used, practical limitations meant that purposeful random sampling and purposeful sampling of adolescent parents were also utilized.Citation14 The final sample included 10 females and 10 males.

Participants were first asked how they defined the terms sexual health, sex education and sexuality, to ensure a common understanding of these key terms between researcher and participant. The remainder of the questions were structured around the sources of sexual health and sexuality information described in the literature, pilot interviews and focus group discussions: teachers, family, friends, partners, health professionals, internet, television, films, advertisements, radio and religion. Participants were asked about the content of the information they sought or received, how it was communicated, the trustworthiness of the sources, as well as the way gender influenced their learning. The interview guide was used flexibly as some adolescents provided detailed responses to open questions, whilst others required more extensive probing.

Finally, seven key informants were interviewed in order to triangulate data from adolescent interviews and include adult perspectives on themes developed by adolescents. Informants included three school psychologists, three health professionals (midwife, paediatrician and gynaecologist) and a Catholic priest with extensive experience working with adolescents. Interview questions were based on preliminary findings and anecdotes from adolescent interviews and discussions.

During recruitment, the first author presented the study to potential participants, describing the objectives, methods and ethical considerations of participation. Prior to interviewing, verbal and written informed consent was collected from all participants. For those adolescents under 18 years of age, written parental consent was collected before the interviews, alongside adolescent assent.

Data analysis in the field included journaling and transcription, as well as debriefing and formal pre-analysis sessions within the interview team. During these sessions, completed transcripts were revised and recurrent and emerging themes were discussed. This allowed for tweaking the interview guide, improving interview techniques, evaluating saturation of data and exploring new emergent themes. Structured analysis upon returning from the field was based on Taylor-Powell and Renner’s five steps in content analysis.Citation15 All interviews and discussions were coded manually by the first author. Initially data was coded descriptively using present categories based on the sources of sexual health information from the literature and interview guide. These codes were expanded and re-coded analytically into larger categories based on the content of sexual health and sexuality information. Finally, merging of categories resulted in three major themes, one of which is reported in this paper. The remaining themes are reported elsewhere.Citation13

The study has several limitations that could affect the transferability of the results. Given that participation was voluntary, the sample may be biased towards adolescents with a stronger interest in the topic of sexuality compared to their peers. Also, since the university students were studying anthropology, they may have been more inclined to social criticism than adolescents in general. Recall bias may have affected the participants’ ability to describe in detail their experiences learning about sexuality whilst growing up. Limitations aside, this study provides valuable insights into adolescent views on sexuality in Chile.

The Board of Ethics at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Chile, Santiago and the Norwegian Social Science Data Service approved this study.

Findings

Defining sexual health, sex education and sexuality

Adolescent definitions of sexual health focused on biological heterosexual relations as they relate to pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections and contraception. Sex education was generally defined in relation to a way of learning as passive or active, theoretical or practical. When asked to define sexuality, participants tended to take long pauses, stating that sexuality was hard to put into words. Subsequent responses included short replies such as “man and woman” or “homosexual and heterosexual”, as well as broader definitions such as:

“Sexuality… that has more meaning. Sexuality can be a way of being, or directly related to the sexual act, with a person's sexuality, with their personality.” (Male, 18 years, interview)

The most frequent responses included topics of identity as a man or woman, sexual orientation, partner relations and biological development.

Gendered sexuality: Roles and representations

Adolescent definitions of sexuality included identity as female or male, and differences in the roles and representations of female and male sexuality were particularly noteworthy during interviews and focus group discussions. A double standard between gender-appropriate discourse and behaviour was discussed by a number of participants, particularly during focus group discussions. The primary socializing agents were parents, teachers and peers.

Participants described how parents and teachers talked about female sexuality as a type of risk, both in relation to the higher biological and sociocultural burdens of adolescent pregnancy, as well as the greater risk of being exposed to sexual violence. A university participant critiqued her school sex education for this:

“I feel that with females the topic of sex is always talked about as something serious, because it's viewed as a type of risk […] because they can become pregnant at a young age. I feel that it [female sexuality] is very stigmatized because of this. In contrast, for males it's more like an exploration […] more relaxed.” (Female, 18 years, focus group discussion)

Similarly, one male described differential treatment by his parents between himself and his younger sister due to this gendered risk:

“I think they'll talk more with her than they did with me as a male, because she’s a woman and she's more at risk.” (Male, 17 years, interview)

Female sexuality was also described as something hidden, with females projecting an outward image of ignorance about sexual health and sexuality topics. This was demonstrated through partial self-censorship in front of male peers, or complete self-censorship in front of female peers as well. Participants in the two male focus groups discussed this as a conscious decision made by females to distinguish between their private and public images:

“It’s very different what they talk about in public and what they say between themselves intimately, it’s like they’re more vulgar perhaps, between friends, but outwardly they’re more… prudent, more like a lady.” (Male, 19 years, focus group discussion)

This idea that females maintain their image of being “a lady” was also reflected in discussions of the acceptability of females watching pornography compared to males:

“I would say that it’s far less accepted, there could be some [females that watch pornography] but […] they wouldn't talk about it […] You expect that a female will be a lady. You expect a male to be more like a cave man.” (Male, 17 years, interview)

This analogy reiterated the gender double standard whereby expression of female sexuality or interest in sexual pleasure/stimulation was defined as un-ladylike. Furthermore, words used throughout interviews to describe females during sex education lessons included: “quiet”, “reserved”, “withdrawn”, “timid”, “nervous”, “introverted”, “prudish”, “not wanting to see”, “self-conscious” or “contracted”; whilst males were described as “impulsive” and “curious”, often joking and laughing during the classes. A male participant described his observations of this double standard in language:

“The male is used to being the centre of attention, so it’s like, no one will complain about what he says […] if a man says ‘dick’ everyone laughs, if a woman says ‘dick’, ‘why did she say dick?’ Understand? It's like the woman is stigmatized.” (Male, 18 years, focus group discussion)

In relation to behaviour, one adolescent mother described her observation of the double standard celebrating male sexual activity whilst stigmatizing female sexual activity:

“Females need to be more reserved, and… to say it in a vulgar way, not go to bed with everyone […] but if the male comes and does the same thing as the female [has multiple sexual partners], the female will be judged negatively and the male will be judged as macho. This is just part of life.” (Female, 18 years, interview)

Conversely, participants described how a male abstaining from sex was the subject of jokes between male peers. Jokes included asking when he was going to “become a man”, stating he was “made of iron”, “without feelings”, “cold” or questioning whether he was homosexual.

Another aspect of sexuality governed by this gender double standard was pleasure. Adolescents explained that masturbation was the only topic related to sexual pleasure discussed in the formal school setting, however only as a natural process of sexual development for males. One school psychologist shared her observations of teaching about masturbation:

“The females in general kept silent, they said ‘women don’t do that’, they said ‘how’s she going to do it?’ […] I told them 'women also masturbate, for them it is also normal because it is part of exploring one’s body’. They remained with the expression ‘but why?’” (School psychologist)

Even given these observations of gender inequalities in language and behaviour, many younger participants described a generational change whereby traditional gender double standards were no longer valid in Chilean society. Conversely, many of the older university participants were more sceptical, stating that Chile remained a “machista”, “conservative” country.

Sexual diversity: Attitudes and explanations

Many adolescent definitions of sexuality included sexual orientation and adolescents were probed specifically about where and what they had learnt about sexual orientation. The main socializing agents that provided information or opinions on sexual orientation were teachers, parents, peers, health professionals and media. The term homosexuality was used in questioning to explore issues of sexual diversity, as many adolescent participants were not familiar with the term sexual orientation.

It was observed that participants discussed the topic of sexual diversity with fluidity, many stating that the topic was no longer taboo in Chile. Examples of this change were given through descriptions of seeing same-sex couples in schools, on the streets of Santiago and in the media. As two females described:

“When one’s a child, it’s strange to see a homosexual man or woman. But now I think that it’s part of the society that we’re living in… If one sees two men hand in hand, it’s like it makes no difference… But in the past it was unacceptable, no way.” (Female, 18 years, interview)

“Now you see it [same-sex couples] more frequently. Now they dare more.” (Female, 18 years, focus group discussion)

Although this increased visibility may indicate a change in social acceptability of same-sex couples, the word “dare” indicates an ongoing element of danger. Another female, who stated that she respected homosexual people, described discussions with friends about the contagious effect seeing same-sex couples together could have on children:

“None of us think that it’s good for children to see that [same-sex couples]. Because then they'll think that it's okay and then everyone will be homosexual.” (Female, 16 years, interview)

One participant called this increased visibility a “fashion of bisexuality”, describing her observations of same-sex couples in the playground, photos of same-sex couples uploaded on social networking sites and seeing peers on television participating in “gay pride” marches. One health professional related this “fashion of bisexuality” to adult sexual rights discourses and extensive media coverage of rights movements:

“I think it has to do with us, the adults, and the discourse we give, not only to adolescents, but to the whole society, that homosexuality is accepted. There is no drama with that, it is a different form of expressing oneself. But for adolescents […] because of their maturing process, they pass through a stage of searching for their sexual identity [..] and adolescents today don’t just stop at reflection, instead they try it out.” (Healthcare professional)

Other key informants and university focus group participants shared their observations of a general lack of reflection on sexual behaviours by Chilean adolescents, regardless of sexual orientation. This was described as a result of the increased sexualization of youth culture, primarily through media exposure. Examples of this “sexualization” included erotic music such as reggaeton, hyper-sexualized commercial marketing, online pornography, publication of erotic content on social networking sites and online sexual abuse such as “grooming”.Footnote‡ Two key informants also described eroticization of youth behaviour through highly sexualised youth movements, giving the example of “ponceo” and the Santiago urban tribes of the late 2000s.Footnote§ This exposure to hyper-sexualized content without critical reflection was seen to influence adolescent sexual behaviour.

Sexual orientation was also discussed in schools, at home and between peers from the perspective of discrimination. When initially probing adolescents about what they had learnt about homosexuality, it was common for participants to first describe their learning in relation to their personal opinions of sexual diversity and then describe who or what had shaped their opinion. Many adolescents described how teachers and parents taught them to respect or accept individuals with non-heterosexual orientations. One female described the message she received from her mother:

“Ever since I was young she’s told me there are people like that [homosexual], that you can meet a variety of people and preferences, so you have to accept them, in reality they are people.” (Female, 18 years, interview)

Others received messages openly rejecting sexual diversity:

“My mum doesn’t like homosexuals, she doesn’t believe in it because she’s religious, my mum’s evangelical […] If I were a lesbian, my mum would die. She wouldn't accept it.” (Female, 17 years, interview).

Although many adolescents initially described their opinions of homosexuality using words such as “respect” and “acceptance”, inconsistencies were also apparent with one male participant later describing homosexual males as “repulsive”, whilst another female stated that having a lesbian friend would be “terrible”. Others described their respect as conditional:

“I know I must respect them, because they are people and have sexual deviations, at least if they don’t affect me and trespass on my space, I respect them.” (Male, 16 years, interview)

The idea of “sexual deviations” can be linked to observations of a medicalization of sexual diversity. Healthcare professionals and schools medicalized sexual diversity by referring adolescents suspected of being homosexual, lesbian or bisexual to psychologists and psychiatrists for specialist follow-up. When probed on what these key informants expected from the mental health services, informants described the special needs of individuals with non-heterosexual orientations for guidance in discovering their orientation, and support in revealing their orientation to their social network. One health professional also stated it was important to investigate whether there was any history of childhood sexual abuse to explain the homosexual orientation, whilst sharing her belief that in most cases homosexuality was genetic.

Finally, a number of participants described how in schools a non-heterosexual orientation was explained as a biological condition resulting from hormonal imbalances or genetics. One participant described a classroom debate about whether a person was born homosexual or became homosexual, whilst another participant described a class presentation where peers discussed whether homosexuality was a disease or not.

These findings on gendered sexuality and sexual diversity provide an insight into the breadth of opinions, experiences and attitudes shared by participants in this study. The following discussion will explore key issues emerging from these findings regarding the social construction of gender and sexuality, which impact upon the social acceptance of sexual and reproductive rights in Chile.

Reflections and discussion on the construction of gender and sexuality

Gender role socialization and double standards

Gender socialization starts early in life as children learn what gender is assigned to them, alongside the social expectations and appropriate behaviour this implies in their given social context.Citation2 These roles are taught in the home, later reinforced by peers, schools and media, and difficult to change.Citation1,16 Sexuality may also be regarded as a social construction, shaped by socializing agents with power to control and define appropriate and inappropriate sexual objects and behaviours.Citation11 In this study, this power was visible through the influence of the family, education, medicine, religion and media on adolescent conceptualizations of sexuality and gender.

In Chile and Latin America in general, Catholicism has historically promoted binary gender separation and strict gender roles within the family.Citation2 These roles are founded on a system of patriarchy where the male represents economic power as the provider, whilst the female is venerated in her role as mother and carer in the home.Citation17 Sexual diversity and female gender empowerment (including economic and political participation) threaten these traditional roles, providing ripe ground for gender-based repression and homophobia. Homosexuality may be seen as less of a threat to the gender system in a society where gender roles are more fluid and fewer assumptions are made about innately male and female characteristics.Citation18 Thus, in contexts with high levels of homophobia, fear of being socially defined as homosexual may encourage adoption of hyper-feminine behaviours for females and hyper-masculine behaviours for males.Citation19 In Latin America the term “machismo” is often used to describe an over-exaggeration of male masculinity, virility, power and dominance, whilst females (and homosexual males) are framed as passive and powerless.Citation17 Females may be expected to behave in lady-like and hyper-feminine ways,Citation19 remaining passive and obedient,Citation20 as well as virtuous and chaste like the Virgin Mary.Citation17

In this current study, gender role socialization was exemplified through gender double standards of discourse and behaviour. Participants described how a woman was expected to maintain the reputation of “a lady”, and thus not use joking or explicit words when talking about sex, nor watch pornography, masturbate or have multiple sexual partners, whilst males were expected to be sexually assertive to prove their masculinity and heterosexuality. This sexual double standard is in no way unique to Chile, on the contrary, a systematic review of 268 qualitative studies from a range of global settings found striking similarities in the gender double standards determining sexual behaviour and restricting female sexual expression.Citation21 The descriptions of partial or complete female self-censorship, observations of shy female behaviour during sex education classes, and scepticism at the idea of female masturbation, may all be interpreted as an enactment of the gendered expectation of modesty and ignorance. It also exemplifies the internalized barriers to gender equality that female adolescents themselves may carry as a result of lifelong gender socialization into “appropriate” female behaviours. In this way female sexuality, in particular female sexual assertiveness and pleasure, is repressed and stigmatized. Repercussions of this gender repression may stretch far beyond unequal entitlement to sexual pleasure to include sexual violence. A study on adolescent pregnancy in Ecuador found that female sexual and reproductive freedom was constrained by socialization teaching female passivity and obedience.Citation20 This gender subordination was not only covertly perpetuated through symbolic constructions of female passivity, but also overtly enacted through sexual violence.Citation20

Female risk discourse

Female sexual behaviour was also restricted through implicit or explicit depictions of female sexuality as riskier than male sexuality. Adolescent females carry a higher health and socioeconomic burden of unplanned pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections.Citation22 However, socializing adolescents into believing this risk justifies societal control of female sexuality disregards the fundamental roles legal, social and economic discrimination and gender inequality play in increasing this burden for females.Citation22 LuptonCitation23 critiques the rationalized concept of risk as an objective phenomenon, instead describing risk as something that serves a political, cultural and social function. In the healthcare field, medicine and epidemiology constantly seek to objectively quantify this risk, nevertheless, little attention is paid to the social, economic and cultural contexts in which this risk is manifested.Citation23 In their systematic review, Marston and KingCitation21 describe socio-cultural factors that influence youth sexual behaviours, which in turn have implications for sexual health outcomes. These factors include social expectations that make communication about sexuality and thus planning/negotiation of safe sex impossible, social stigma that prevents women from carrying condoms even when they are seen as responsible for contraception, and societal normalization of sexual coercion and violence against women.Citation21 Many of these factors are based on gendered power imbalances in relationships that hinder shared responsibility for ensuring safe, consensual and pleasurable sex.

Heteronormativity and medicalization of sexuality

The female risk discourse limits discussion of wider topics such as sexual pleasure and masturbation, alternative sexual acts such as oral or anal sex, as well as ignoring alternative sexual partnerships such as lesbian and transgender relationships. This leads directly to a discussion of how conceptualizations of sexual diversity are also socially constructed through heteronormative information provided by schools and parents. What is defined as “normal” is only made legitimate in relation to the “abnormal” other.Citation24 Thus the superiority of heterosexual relationships is repeatedly legitimized through comparison with homosexuality as a deviation from the norm, implying a type of hierarchy in sexual orientation.Citation26 In this study, the distinction between normal and abnormal sexual orientation was exemplified in the desire to explain homosexuality through biology, genetics, social context (e.g. a fashion) or history of childhood sexual abuse. This desire to explain non-heterosexual orientations has been reflected in extensive research exploring biological and environmental factors influencing development of sexual orientation.Citation25 However, this focus on explaining sexual orientation overshadows vital exploration of the social and cultural conditions that continue to make these distinctions between “normal” and “abnormal” sexual orientation significant in many contexts.

Medicine also plays a role in defining normal sexuality along a normal-abnormal continuum.Citation10 Medicalization of homosexuality has a long history in Chile, encompassing the disciplines of psychiatry, psychology, genetics and endocrinology,Citation26 and the example of a class discussion on whether homosexuality was a disease or not seems to be a lasting legacy of this. The medicalization described by key informants in this current study was not focused on curing or explaining homosexuality, rather providing support and guidance to youth discovering their sexual orientation. Healthcare professionals have been identified as an important source of information for lesbian, gay and bisexual youth.Citation27 It is therefore an unfortunate paradox that the process of referral to mental health services risks stigmatizing these youth as abnormal, when the goal of these services seems to be to support youth facing potentially hostile attitudes in their social networks.

Attitudes towards sexual diversity

The attitudes towards sexual diversity shared by adolescents in this study were broad, ranging from open rejection to full support. This may be a reflection of the breadth of attitudes present in Chilean society today. Although many youth described being taught by teachers and parents not to discriminate, using the terms “acceptance” and “tolerance”, even these may be considered discriminatory attitudes as they imply that a non-heterosexual orientation is undesirable and must be accepted or tolerated by a heterosexual individual. In this way, encouraging tolerance may be seen as the opposite of embracing diversity.Citation24 As observed in this current study, accepting or respecting sexual diversity may be conditional to some form of restriction of behaviour or distance, which seems to mask an underlying discrimination or fear of contagion.

Many adolescents described a societal shift whereby the taboo of discussing homosexuality no longer existed and sexual rights organizations describe an overall positive cultural change in relation to sexual diversity in Chile.Citation28 Nevertheless, hazard remains with ongoing violent homophobic attacks serving as constant reminders of the dangers of discrimination based on sexual orientation.Citation28

Concluding reflections

The ability to realize one’s sexual and reproductive rights is intrinsically linked to both legal rights and social acceptance. Ensuring both legal and social protection of these rights is a challenge in a context where complex cultural, religious and moralistic ideologies define and control “appropriate” sexual and gender expression. Thus, even when legal, financial or institutional barriers to sexual and reproductive rights are removed, external and internal sociocultural barriers may still restrict an individual's enjoyment of these rights.

To compound these challenges, adolescents today face a perplexing assortment of mixed messages about gender and sexuality from the social world around them. The traditional religious morals on sexual behaviour that many adolescents learn at home or at school, contrast to the hyper-sexualized media many adolescents are exposed to. Similarly, media coverage of social movements for greater gender equality and sexual rights, contrasts to the ongoing pressure many adolescents face to conform to the strict gendered expectations of their families and peer groups.

To manage this wide array of conflicting information, it is important that children and adolescents are taught to be critical consumers of information, whatever the source, in order to make well-informed decisions regarding their sexuality and sexual health. Furthermore, to confront both internal and external barriers to gender equality and sexual diversity, it is vital that children and adolescents are encouraged to reflect on the meaning of sexuality and gender in their social context. Trusted adults such as teachers, parents and healthcare professionals may be key facilitators of this reflection, promoting critical thinking and diverse understandings of gender and sexuality from an early age, founded on human rights and gender equality.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants for sharing their experiences and opinions with the research team. Special thanks to Magdalena Rivera for her valuable contributions as research assistant in the field. This study received a grant from the Helle Foundation towards field costs.

This research is based on Anna K-J Macintyre's MPhil thesis in International Community Health, submitted in May 2014 to the Institute of Health and Society, University of Oslo, Norway.

Notes

* The first same-sex civil unions were performed in Chile on the 22nd October 2015.

† Information was collected from school websites and school psychologists.

‡ Online grooming is a form of cyber sexual abuse whereby the abuser builds an emotional relationship with a victim online, often by posing as a same aged peer in chat rooms or social networking sites. Once the relationship has developed, the abuser may establish online sexual contact by encouraging the victim to pose for erotic photos, engage in “sex talk” or watch/perform sexually explicit acts in front of a web camera. Alternatively they may arrange offline contact to meet the victim in person.

§ The urban tribes were social movements where youth formed groups identified by a particular style of dress and attitude. These youth would often gather in public parks or at large underage parties to engage in activities such as “ponceo”, which involved kissing and groping/fondling as many partners as possible, often independent of gender.

References

- WHO. Defining sexual health. Report of a technical consultation on sexual health, 28–31 January 2002, Geneva. 2006; WHO: Geneva. [http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/sexual_health/defining_sexual_health.pdf].

- S. Chant, N. Craske. Gender and sexuality. S. Chant, N. Craske. Gender in Latin America. 2003; Latin American Bureau: London.

- D. Altman. Global Sex. 2001; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL.

- B. Shepard. The “double discourse” on sexual and reproductive rights in Latin America: The chasm between public policy and private actions. Health and Human Rights. 4(2): 2000; 110–143.

- CEDAW. Concluding observations of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women: Chile. 2012; United Nations: New York. [http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/cedaw/docs/co/CEDAWCCHLCO5-6.pdf].

- N. Craske. Gender, politics and legislation. S. Chant, N. Craske. Gender in Latin America. 2003; Latin American Bureau: London.

- V. Guzmán, U. Seibert, S. Staab. Democracy in the country but not in the home? Religion, politics and women's rights in Chile. Third World Quarterly. 31(6): 2010; 971–988.

- L. Casas, C. Ahumada. Teenage sexuality and rights in Chile: from denial to punishment. Reproductive Health Matters. 17(34): 2009; 88–98. [http://www.rhm-elsevier.com/article/S0968-8080(09)34471-7/pdf].

- Decree 79, Law 18.962. March 24. 2005

- L. Casas, L. Vivaldi. Abortion in Chile: the practice under a restrictive regime. Reproductive Health Matters. 22(44): 2014; 70–81.

- J. DeLamater. The social control of human sexuality. K. McKinney, S. Sprecher. Human Sexuality: The Societal and Personal Context. 1989; Ablex Publishing: Norwood, N.J.

- J. Schutt-Aine, M. Maddaleno. Sexual health and development of adolescents and youth in the Americas: Program and policy implications. 2003; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, D.C.. [http://www1.paho.org/English/HPP/HPF/ADOL/SRH.pdf].

- A.K.J. Macintyre, A.R. Montero Vega, M. Sagbakken. From disease to desire, pleasure to the pill: A qualitative study of adolescent learning about sexual health and sexuality in Chile. BMC Public Health. 15(945): 2015. [http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/s12889-015-2253-9.pdf].

- M.Q. Patton. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed., 2002; Sage: Thousand Oaks, C.A.

- E. Taylor-Powell, M. Renner. Analysing Qualitative Data. 2003; University of Wisconsin Extension: Madison, W.I.. [http://learningstore.uwex.edu/assets/pdfs/g3658-12.pdf].

- V. Bryson. Feminist Political Theory: An Introduction. 2nd ed., 2003; Palgrave MacMillan: New York.

- M. Melhuus. Configuring gender: Male and female in Mexican heterosexual and homosexual relations. Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology. 63(3-4): 1998; 353–382.

- S. Kamano, D. Khor. Toward an understanding of cross-national differences in the naming of same-sex sexual/intimate relationships. NWSA Journal. 8(1): 1996; 124–141.

- M.G.F. Worthen. The cultural significance of homophobia on heterosexual women's gendered experiences in the United States: a commentary. Sex Roles. 71: 2014; 141–151.

- I. Goicolea. Adolescent pregnancies in the Amazon Basin of Ecuador: a rights and gender approach to adolescents' sexual and reproductive health. Global Health Action. 3June 24. 2010. [http://www.globalhealthaction.net/index.php/gha/article/view/5280/5726].

- C. Marston, E. King. Factors that shape young people's sexual behaviour: a systematic review. Lancet. 368Nov 4. 2006; 1581–1586.

- UNFPA. Motherhood in childhood: Facing the challenge of adolescent pregnancy. 2013; UNFPA: New York. [http://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/EN-SWOP2013-final.pdf].

- D. Lupton. Introduction: Risk and sociocultural theory. D. Lupton. Risk and Sociocultural Theory: New Directions and Perspectives. 1999; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- K.C. Franck. Rethinking homophobia: Interrogating heteronormativity in an urban school. Theory and Research in Social Education. 30(2): 2002; 274–286.

- E.M. Saewyc. Research on adolescent sexual orientation: Development, health disparities, stigma, and resilience. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 21(1): 2011; 256–272.

- J.R. Cornejo. Configuración de la homosexualidad medicalizada en Chile. Sexualidad, Salud y Sociedad. 9Dec. 2011; 109–136. [http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S1984-64872011000400006&script=sci_arttext].

- I.D. Rose, D.B. Friedman. We need health information too: A systematic review of studies examining the health information seeking and communication practices of sexual minority youth. Health Education Journal. 72(4): 2013 July; 417–430.

- Movimiento de Integración y Liberación Homosexual (MOVILH). XIII Informe anual de derechos humanos de la diversidad sexual chilena (Hechos 2014). 2015; MOVILH: Santiago, Chile. [http://www.movilh.cl/documentacion/2014/XIIIInformedeDDHH2014-web.pdf].