Abstract

In recent decades, attitudes in many parts of the Arab region have hardened towards non-conforming sexualities and gender roles, a shift fuelled in part by a rise in Islamic conservatism and exploited by authoritarian regimes. While political cultures have proved slow to change in the wake of the ‘Arab Spring’, a growing freedom of expression, and increasing activity by civil society, is opening space for discreet challenges to sexual taboos in a number of countries, part of wider debates over human rights and personal liberties in the emerging political and social order.

Résumé

Ces dernières décennies, les attitudes dans de nombreuses parties de la région arabe se sont durcies à l’égard des sexualités et des rôles sexospécifiques non conformes, une évolution alimentée en partie par une montée du conservatisme islamique et exploitée par les régimes autoritaires. Si les cultures politiques ont été lentes à changer au lendemain du « printemps arabe », dans plusieurs pays, une plus grande liberté d’expression et une activité croissante de la société civile ouvrent l’espace pour une discrète remise en question des tabous sexuels, dans le cadre de débats plus larges sur les droits de l’homme et les libertés individuelles au sein de l’ordre politique et social émergent.

Resumen

En décadas recientes, en muchas partes de la región árabe, se han endurecido las actitudes hacia sexualidades y roles de género no convencionales, un cambio impulsado en parte por un aumento en el conservatismo islámico y explotado por regímenes autoritarios. Mientras que las culturas políticas han resultado ser lentas en cambiar tras la 'Primavera árabe', la creciente libertad de expresión y creciente actividad por la sociedad civil están abriendo camino para retos discretos a los tabúes sexuales en varios países, parte de debates más amplios sobre los derechos humanos y libertades personales en el nuevo orden político y social.

In the Arab region, movement on sexual rights generally follows Newton’s Third Law: for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. A case in point is Morocco. In May 2015, King Muhammad VI, Head of State and the country’s highest religious authority, authorised a new law on abortion. The existing legislation was, on paper, highly restrictive, allowing terminations only in the case of risk to a woman’s life or health, and then only with permission of her husband or local medical officials. The upshot was a thriving business in illegal abortions: upwards of 600 a day,Citation1 whose complications were estimated to account for almost 5% of maternal deaths.Citation2

With the rise of Morocco’s Islamist party – the Parti de la Justice et du Développement (PJD) – to the head of government in 2011, its hard line on abortion also meant a sharp rise in the prosecution and sentencing of doctors conducting such illegal procedures. After several months of national consultation, led by the Ministers of Justice, Religious Affairs and the National Council on Human Rights, the new law was approved, widening the legal grounds for abortion to include rape and incest, as well as fetal abnormalities.Citation3 While far short of the liberalization that public health experts and women’s rights activists had hoped, the new law is nonetheless a step forward.

That same month, Moroccan filmmaker Nabil Ayouch found himself on the back foot. His latest film, Zin Li Fik (Much Loved), tells the story of female sex workers in Marrakech, and spares little detail about their business. Such experiences are reflected in a number of studies on sex work in the country, including a four-city investigation of the lives of more than a thousand female sex workers, and their risk of HIV, conducted by a leading Moroccan NGO and cited by the Moroccan Ministry of Health.Citation4 But cold facts in print are one thing; hot scenes on screen quite another. Much Loved was banned by the Moroccan government long before its scheduled release in the country; Facebook death threats aside, Ayouch and his leading lady have also been accused of undermining the “Kingdom’s image”, and summoned on charges of pornography, public indecency and inciting debauchery.Citation5

Four years ago, the high hopes of the Arab uprisings were writ large, quite literally, in the graffiti wallpapering Cairo, Tunis and cities across the region. Since then, the grand political aspirations which fed the Arab Spring have either frosted over, as in Egypt, or burnt up in the conflagration now consuming Libya, Yemen, Syria and Iraq. Sex has shown itself a powerful tool in the hands of the region’s newly minted authoritarian regimes, be it sexual exploitation of women under ISIS’s reign of terror,Citation6 or the state-sanctioned sexual abuse of political opponents in Egypt.Citation7

The Arab world is vast and varied – 370 million people, 22 states, three major religions and dozens of ethnic groups – with as much diversity within borders as there is across them. Yet running right across it is a hard and fast rule: the only publicly-accepted sexuality is strict heteronormativity, its cornerstone family-endorsed, religiously-sanctioned, state-registered marriage. Anything outside this context is haram (forbidden), illit adab (impolite), ‘ayb and hchouma (shameful) – a seemingly endless lexicon of reproof. It is a social citadel, like those impregnable fortresses which once braced the land, from Marrakech to Baghdad, resisting any assault, any challenge to sexual norms. Outside the citadel lies a vast terrain of taboo – premarital sex, homosexuality, unwed motherhood, abortion – and a culture of censorship and silence, preached by religion, buttressed by law and enforced by social convention.Citation8

Public opinion would appear to uphold this sexual status quo. In a recent Pew Research Center survey, more than 80% of those polled across the Arab region rejected homosexuality and premarital sex as “morally unacceptable”.Citation9 This pattern is in stark contrast to much of Western Europe, Australasia and North America, where less than two-fifths of those surveyed considered such practices untenable.Citation9 Yet on questions of democracy and its importance to their own lives, their publics were far more closely aligned, even with popular disenchantment in the aftermath of the Arab Spring.Citation10 It remains true, as academics Norris and Inglehart observed in 2002, that the gulf separating Middle East and West “involves Eros far more than Demos”.Citation11

These conflicts play out in international fora, notably at the United Nations, with battle lines clearly drawn over sexual rights. Since the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo, civil society and governments around the world have struggled to enshrine sexual rights in international agreements, in the face of strong resistance from Arab states, collected under the umbrella of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC).Citation12 More recently, further alliances have formed with member states of the African Union, as well as Russia and its allies, to oppose recognition of rights on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, and to enshrine the legitimacy of “traditional values” and conservative definitions of the family.Citation13

The rise of Islamic conservatism in the Arab region since the 1970s has significantly hardened and politicized attitudes towards gender roles and sexuality, for both men and women, in many quarters. While gains have been made in a number of countries on some aspects of sexual rights, particularly as they relate to marriage (for example, 2008 amendments to Egypt’s Child Law), these have been introduced in the absence of wider political, economic and social reforms recognizing and respecting fundamental human rights. Where laws have been reformed, as in the example of Morocco above, change is often small or piecemeal, as governments try to minimize the ammunition on offer to even more conservative forces in society. For example, Lebanon’s recent introduction of anti-domestic violence laws fails to explicitly recognize marital rape as a crime, much to the dismay of human rights activists, since the concept of rape within marriage is disputed by key Islamic authorities in the country.Citation14

Progressive laws are hard to enforce in the face of societal opposition, which can include the judiciary. Female genital mutilation, for example, is slowly declining in Egypt, with two-thirds of 15-17 year old girls now circumcised, down by almost a quarter since 2008.Citation15 But it took more than six years, and several acquittals, before an Egyptian court finally passed sentence under the country’s law criminalizing the practice. On the other hand, as recent events clearly demonstrate, punitive regulations and heavy-handed enforcement are all too common and all too often directed at women, whether it is official discrimination against students in Algeria for the length of their skirts, or the rape by police and subsequent detention of a Tunisian woman for going on a date with her fiancé, or the conviction of a Norwegian woman in the UAE for extramarital sex when she complained to police of having been raped. The calls for justice, freedom and dignity – as well as equality, autonomy, integrity and privacy – which mobilized millions during the Arab Spring are, as yet, unanswered, in and out of the bedroom.

Sex and the single Arab

This is a particularly pressing problem for those beyond the citadel, chief among them unmarried youth. While they are on the sharp end of sexual regulation, a growing sense of freedom of expression means they are increasingly pushing back, and moving forward.

In contrast to many Western societies, matrimony remains the most desirable estate for the vast majority of people across the Arab region. Marriage is the gateway to adulthood – without it, it is difficult to move out of the parental home (all the more so if you are a woman) and almost inconceivable to start a family. Early marriage remains a risk for poor, less educated and rural girls across the region, particularly those in desperate circumstances. Syrian refugees, for example, continue to be trafficked into sex work, masquerading as short-term marriages, by their impoverished families.Citation16 But matrimony by 16 and motherhood soon thereafter, which was the norm only a generation or two ago, is a declining proposition, even in such traditional strongholds as Yemen.Citation17

There is, instead, trouble brewing at the other end of the spectrum. The mean age of marriage is rising in much of the Arab region, in some cases dramatically: in Tunisia, for example, on average women are first marrying in their late twenties and men in their early thirties.Citation18 This delay is due in part to economics, matrimony having become an expensive proposition in the consumer-culture economies of the Arab region. Tradition and religion dictate that men and their families cover the costs of marriage, from the big white wedding and beyond, but double digit unemployment among youth – a major driver of the recent uprisings – means that men are having to wait to tie the knot.

At the same time, significant advances in female education, and the small, but growing, presence of women in the workplace, is also pushing up the age of marriage of women. Indeed, there is rising moral panic in many countries over the phenomenon of ‘anusa, or spinsterhood – educated women who fail to find a husband, and therefore remain at home, dependent on their families.Citation19 Divorce is causing similar social anxiety, particularly in the wealthier Gulf States, which fear a rising tide of family disintegration, and a loss of national identity in the face of mass migration of foreign workers to their rapidly developing economies. Nonetheless, fears of the death of marriage in the Arab region are greatly exaggerated: beyond the headlines, official statistics show that most people in the Arab region get, and stay, married, though they are, in many cases, waiting longer now to do so.Citation18

As a consequence, there are more single youth in the region than ever before. This is a generation caught between biology and sociology, reaching sexual maturity in a climate that is reluctant to countenance any alternative to sex within marriage. Given rising religiosity among much of the region’s youth, an unknown number are also turning to alternative forms of marriage within Islam, among them mut‘a (temporary “pleasure” marriage, permitted under Shi‘i Islam) and ‘urfi (“customary” marriage, increasingly popular in Sunni-majority countries) in an attempt to give their sexual relations a religious cover, however controversial.Citation20 For most young people, however, these unions remain more of a last resort than a lifestyle choice.

Research on unmarried youth sexuality remains difficult across the region, in large measure due to official reluctance to face up to the shifting cultural and demographic landscape. Even where it is possible to ask such questions, getting honest answers can be a challenge, given the pressure on young people to conform to societal expectations. Still, it is clear that young people are not waiting for marriage to make their sexual debut. Findings from Lebanon and Tunisia, for example, which have the most extensive body of research on youth sexuality, are reflective of smaller studies and anecdotal evidence from across the region: upwards of a third of young men say they are sexually active before marriage, generally making their debut in their mid- to late teens and taking multiple partners along the way.Citation21 Condoms are rarely used, in large measure because of their popular association with zina, that is, religiously proscribed sex outside of marriage.

Far smaller percentages of young women are willing to admit to premarital sex. This is due to the primacy of female virginity. Sex before marriage is legally prohibited for both sexes – at least on paper – in many Arab states, but law, as anywhere in the world, does little to influence people’s sexual behaviour. Although the major faiths of the region extol premarital chastity, in patriarchal societies the world over, boys will be boys: men have sex before marriage and people largely turn a blind eye. Not so for women in communities across the Arab region, who are expected to be virgins on their wedding night – that is, turn up with their hymens intact. This is not a private affair, but rather a collective concern, a matter of family reputation, and in particular men’s honour. And so women and their relatives continue to go to great lengths to conserve this tiny membrane, from female genital mutilation to virginity testing to hymen repair surgery.

Under even further pressure are young men and women who cross the heteronormative line – who have sex with their own sex, or have a different gender identity. They’re on the receiving end of laws which punish their activities, even their appearance, in most countries of the region, whose application (in the case of Egypt’s recent crackdown on gay men and transgender women) has more to do with realpolitik than morality. Add to this a daily struggle with social stigma, family despair, media misrepresentation and religious fire and brimstone. While religious conversion is, quite literally, a matter of life and death in the Arab region, sexual conversion – gay to straight, that is – is generally viewed as not just acceptable but strongly advisable by most families, with the result that reparative therapy is thriving in many parts of the Arab region.Citation8

Nor is all well within the bastion of marriage. There is, as yet, no Arab Kinsey report to lay bare the region’s sexual life, but a growing body of research is uncovering plenty of trouble in the marital bed: male impotence, female sexual dysfunction and sexually transmitted infections, for starters.Citation22–24 HIV is a crescent concern. While prevalence rates across the Middle East and North Africa are a tiny fraction of those south of the Sahara, the region is one of only two in the world where HIV is still on the rise: infections have more than doubled and AIDS-related deaths more than tripled since 2000.Citation25 For the moment, HIV is concentrated in certain key populations, whose practices put them at highest risk, among them men-who-have-sex-with-men, female sex workers and people who inject drugs. But sex lies at the heart of this emerging epidemic and that puts women on the front line: in Morocco, for example, more than 70% of women reported to be living with HIV (an underestimate, to be sure) have been infected by their husbands.Citation26

The Arab region is by no means alone in its sexual dilemmas: witness recent furores over homosexuality in Uganda or sexual violence in India or abortion in Spain. But some features stand out. Sex is bound up in shame – particularly for women – which makes it a powerful tool of social control, one which authorities use to devastating effect, be it rape in the Syrian and Libyan civil wars, or forced virginity testing of protestors by Egypt’s military authorities, or the sodomization of prisoners, tool of choice for torturers through the ages.Citation8 Diversity does not do well in dictatorships, so those who fail to conform to norms – sexual, social and otherwise – find little tolerance in most quarters. Sexual rights are hard to exercise when family interests trump individual choice. And when appearance counts for more than reality, in all aspects of life – when virginity is defined by a piece of anatomy rather than a state of chastity, or when prostitution masquerades as marriage.

Back to the future

“Just say no’ is how conservatives around the world respond to any challenge to the sexual status quo. In the Arab region, they often brand such attempts a “Western” conspiracy to undermine so-called traditional “Islamic” and “Arab” values. But history shows us that, within living memory, there have been times of greater tolerance, and pragmatism, and a willingness to consider other interpretations when it comes to sexual life. Be it abortion or condoms or even the incendiary topic of homosexuality, it is not black and white, as conservatives maintain.Citation27–29 On these and other matters, religion and culture offer at least 50 shades of grey.

The Arab Spring, for all its twists and turns, has opened new space for men and women to explore this spectrum. A decade ago, hardly any woman would speak openly about her experience of sexual harassment, let alone rape. Yet today, it is a topic of public debate and civil society action – notably in Egypt with its tide of street-based sexual violence.Citation30 Even domestic abuse, long hidden away, is coming to light, thanks to comprehensive research; recent national surveys in Morocco,Citation31 Tunisia,Citation32 the Palestinian TerritoriesCitation33 and Egypt,Citation34 for example, have shown that around a third of women have experienced gender-based violence at some point in their lives, with a tenth or so reporting sexual violence, on a par with international trends.Citation35 Clearly data is not enough to shift widespread attitudes among men and women, which still condone violence against women, but it is an early step on that long road.

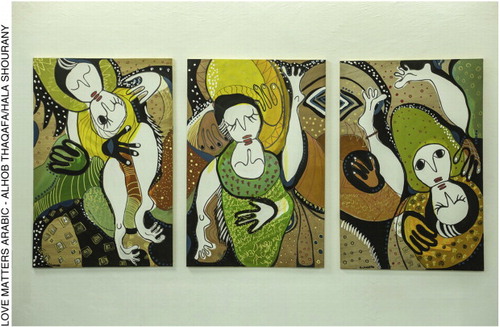

Social media is increasingly central to such progress, offering unprecedented opportunities for sexual expression. A good example is Al-Hubb Thaqafa (“Love is Culture”), a ground-breaking social media platform offering straight talk on love, sex and relationships in Arabic.Citation36 Launched in 2014, its website, Facebook page, Twitter feed and YouTube channel have attracted more than nine million visitors, mainly from Egypt and Morocco. Al-Hubb Thaqafa’s no-nonsense approach to sex, offering accurate information on everything from the basic facts of life to the finer points of fellatio, is a welcome development in a region where teachers are often too embarrassed to communicate even the barebones sexual and reproductive curriculum on offer and parents generally draw a veil of silence over such topics with their kids.

With its emphasis on sex as a pleasure to be enjoyed, rather than a problem to be solved, Al-Hubb Thaqafa harks back to a long tradition of free and frank exchange on sexual matters in Arabic. Short of cybersex and internet porn, there are few topics on its platforms that Arabs were not writing about more than a millennium ago. There is nothing un-Islamic about talking about sex; indeed, many of the great works of Arabic erotica were written by religious scholars, among them Jamal Al-Din Al-Suyuti, a famous Qur’anic exegete and author of almost a dozen books on sexual life.Citation37 Over the centuries, societies across the Arab region have become far less comfortable in their sexual skin. Al-Hubb Thaqafa offers a chance (in part by reclaiming Arabic as a language of sexuality and offering a “respectable” alternative to street slang) for men and women to talk each other about sex – asking questions, sharing personal experiences and contesting each other’s opinions without the usual embarrassment or censure.

Translating online fervor to offline transformation is tough, as millions of political protestors across the region can attest. Arab NGOs supporting LGBT populations are proving remarkably successful at this transition, their numbers having doubled (albeit from a very small base) since the beginning of this decade. Tunisia, for example, now has seven such organizations, many of which are also officially registered with the government. Some are primarily online operations, but a number, among them Damj and Chouf, have a growing presence on the ground, with hundreds of members and highly public activities, joining forces with other organizations to press for minority rights.

There are many more such groups taking root, even on the rockiest ground, for example trying to get sexuality education into schools, improve the lives of sex workers or help unmarried mothers find a place in society. The most successful of these initiatives are keenly aware that change in the Arab region comes not from confrontation, such as FEMEN-style baring of breasts, but through negotiation, along the grain of religion and culture. In essence, we are talking about a sexual evolution, not revolution.

Bringing sexuality into the broader debate on individual rights and personal freedoms emerging in the Arab region is key to change in both political and personal domains. Our sexual lives are shaped by forces on a bigger stage – in politics and economics, science and religion, culture and tradition. And vice-versa. How empowered can women be at the ballot box, if they do not control their own bodies? How will young people lead their societies when they are not trusted with the information and services to lead their own sexual lives? If men and women cannot communicate, cannot treat each other with respect in the bedroom, how can they work as equals in the boardroom? Sexuality is a mirror of the conditions that led to the recent uprisings in the Arab region, and it will be a measure of the progress of hard-won reforms in the decades to come. But that is the work of a generation, at least.

References

- Association Marocaine de Planification Familiale (AMPF). Étude exploratoire de l’avortement à risque. Nov. 2008; AMPF: Rabat.

- Ministère de la Santé. Rencontre nationale sur l’avortement sous le thème “L’avortement : Encadrement législatif et exigences de sécurité sanitaire”. May 15, 2015

- C. Bozonnet. Libéralisation a minima de l’avortement au Maroc. Le Monde. http://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2015/05/18/liberalisation-a-minima-de-l-avortement-au-maroc_4635141_3212.html, 18 May. 2015

- Ministère de la Santé. Mise en oeuvre de la declaration politique sur le VIH/SIDA Rapport National 2014. 2014; Ministère de la Santé, Royaume du Maroc: Rabat. (http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/en/dataanalysis/knowyourresponse/countryprogressreports/2014countries/MAR_narrative_report_2014.pdf).

- A. Alexander. Moroccan director accused of 'pornography and debauchery' over sex worker drama Much Loved. The Guardian. June 24, 2015. (http://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/jun/24/moroccan-director-accused-of-pornography-and-debauchery-much-loved).

- Amnesty International. Escape from Hell: Torture and Sexual Slavery in Islamic State Captivity in Iraq. 2014; Amnesty International: London. (http://www.amnesty.org.uk/sites/default/files/escape_from_hell_-_torture_and_sexual_slavery_in_islamic_state_captivity_in_iraq_-_english_2.pdf).

- FIDH. Exposing State Hypocrisy: Sexual Violence by Security Forces in Egypt. 2015; FIDH: Paris. (https://www.fidh.org/IMG/pdf/egypt_report.pdf).

- S. El Feki. Sex and the Citadel: Intimate Life in a Changing Arab World. 2014; Vintage: London.

- Pew Research Center. Global Views on Morality. www.pewglobal.org/2014/04/15/global-morality.

- World Values Survey Wave 6: 2010-2014. www.worldvaluessurveys.org.

- P. Norris, R. Inglehart. Islam and the West: Testing the ‘Clash of Civilizations’. Thesis, 2002; John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

- A.M. Miller, M.J. Roseman. Sexual and reproductive rights at the United Nations: frustration or fulfilment?. Reproductive Health Matters. 19(38): 2011; 102–118. (http://www.rhm-elsevier.com/article/S0968-8080(11)38585-0/pdf).

- A.T. Chase. The Organization of Islamic Cooperation: A Case Study of International Organizations’ Impact on Human Rights. 2015; The Danish Institute for Human Rights: Copenhagen. (http://www.humanrights.dk/files/media/dokumenter/udgivelser/research/matters_of_concern_series/matters_of_concern_chase_2015.pdf).

- Human Rights Watch. 3 April. 2014; Domestic Violence Law Good, but Incomplete: Lebanon. (https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/04/03/lebanon-domestic-violence-law-good-incomplete).

- Ministry of Health and Population (Egypt). Egypt Demographic and Health Survey 2014. 2015; Ministry of Health and Population and ICF International: Cairo and Rockville, MD, 185–196.

- UNWomen. Inter-agency Assessment Gender-based Violence and Child Protection among Syrian Refugees in Jordan, with a Focus on Early Marriage. 2013; UNWomen: Amman. (http://www.unwomen.org/ࡤ/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2013/7/report-web%20pdf.pdf).

- UNFPA. Marrying Too Young: End Child Marriage. 2012; UNFPA: New York.

- Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA). Bulletin on Population and Vital Statistics in the Arab Region. 16th Ed., 2013; ESCWA: Beirut. (http://www.escwa.un.org/information/publications/edit/upload/E_ESCWA_SD_13_8.pdf).

- H. Rashad. The tempo and intensity of marriage in the Arab region: Key challenges and their implications. DIFI Family Research and Proceedings 2. 2015; 10.5339/difi.2015.2.

- F.S. Hasso. Consuming Desires: Family Crisis and the State in the Middle East. 2010; Stanford University Press: Stanford.

- P. Salameh, R. Zeenny, J. Salamé, M. Waked, B. Barbour, N. Zeidan, I. Baldi. Attitudes Towards and Practice of Sexuality Among University Students in Lebanon. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2015; 10.1017/S0021932015000139.

- A. El-Sakka. Erectile Dysfunction in Arab Countries. Part 1: Prevalence and Correlates. Arab Journal of Urology. 10(2): 2012; 97–103.

- T. Anis, S. Aboul Gheit, H. Saied, S. Al-Kherbash. Arabic Translation of Female Sexual Function Index and Validation in an Egyptian Population. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 8(12): 2011; 3370–3378.

- l Abu-Raddad, F. Akala, I. Semini, G. Riedner, D. Wilson, O. Tawil. Characterizing the HIV/AIDS Epidemic in the Middle East and North Africa. Time for Strategic Action. 2010; World Bank: Washington, DC, 81–101.

- UNAIDS. How AIDS Changed Everything. MDG: 15 Years, 15 Lessons of Hope from the AIDS Response. 2015; UNAIDS: Geneva.

- J. DeJong, F. Battistin. Women and HIV: The Urgent Need for More Research and Policy Attention in the Middle East and North Africa Region. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 18(1): 2015; 10.7448/IAS.18.1.20084.

- G. Shapiro. Abortion law in Muslim-majority countries: an overview of the Islamic discourse with policy implications. Health Policy and Planning. 29: 2014; 483–494.

- A. Omran. Family Planning in the Legacy of Islam. 1992; Routledge: London.

- S. Kugle. Homosexuality in Islam. 2010; OneWorld: London.

- M. Tadros. Reclaiming the Streets for Women’s Dignity: Effective Initiatives in the Struggle against Gender-Based Violence in between Egypt’s Two Revolutions, IDS Evidence Report 48, Brighton: IDS, 2014. http://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/123456789/3384/ERB48.pdf?sequence=4. 2014

- Haut Commissariat au Plan. Enquête nationale sur la prévalence de la violence a l’égard des femmes au Maroc. 2009; Haut Commissariat au Plan: Rabat.

- Office National de la Famille et de la Population. Enquête nationale sur la prévalence de la violence a l’égard des femmes en Tunisie. 2010; Office National de la Famille et de la Population: Tunis.

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS). Main Findings of Violence survey in the Palestinian Society, 2011. 2011; PCBS: Ramallah. (http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/portals/_pcbs/pressrelease/el3onfnewenglish.pdf).

- Ministry of Health and Population (Egypt). Egypt Demographic and Health Survey 2014. 2015; Ministry of Health and Population and ICF International: Cairo and Rockville, MD, 229–245.

- World Health Organization. Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. 2013; WHO: Geneva.

- S. El Feki, E. Aghazarian, A. Sarras. Love is Culture: Al-Hubb Thaqafa and the New Frontiers of Sexual Expression in Arabic Social Media. Anthropology of the Middle East. 9(2): 2015; 1–18.

- E. Rowson. Arabic: Middle Ages to Nineteenth Century. Encyclopedia of Erotic Literature. 2006; Routledge: New York, 43–61.