Abstract

Sexuality education, its protocols and planning are contingent on an ever-changing political environment that characterizes the field of sexuality in most countries. In Brazil, human rights perspectives shaped the country’s response to the AIDS epidemic, and indirectly influenced the public acceptability of sexuality education in schools. Since 2011, however, as multiple fundamentalist movements emerged in the region, leading to recurrent waves of backlashes in all matters related to sexuality, both health and educational policies have begun to crawl backwards. This article explores human rights-based approaches to health, focusing on a multicultural rights-based framework and on productive approaches to broadening the dialogue about sustained consent to sexuality education. Multicultural human rights (MHR) approaches are dialogical in two domains: the communication process that guarantees consent and community agreements and the constructionist psychosocial-educational methodologies. In its continuous process of consent, the MHR approach allowed for distinct values translation and diffused the resistance to sexuality education in the participant schools/cities, successfully sustaining notions of equality and protection of the right to a comprehensive sexuality education that does not break group solidarity and guarantees acceptability of differences.

Résumé

L’éducation sexuelle, ses protocoles et sa planification sont tributaires d’un environnement politique en continuelle évolution qui caractérise le domaine de la sexualité dans la plupart des pays. Au Brésil, les perspectives des droits de l’homme ont façonné la réponse du pays à l’épidémie de sida et ont influencé indirectement l’acceptabilité publique de l’éducation sexuelle à l’école. Néanmoins, depuis 2011, avec l’apparition dans la région de multiples mouvements fondamentalistes qui ont abouti à des vagues récurrentes de réactions hostiles dans toutes les questions relatives à la sexualité, les politiques de santé et d’éducation ont commencé à reculer. Cet article étudie les approches fondées sur les droits de l’homme en matière de santé, en se centrant sur un cadre multiculturel basé sur les droits et des approches productives de l’élargissement du dialogue sur le consentement durable à l’éducation sexuelle. Les approches multiculturelles des droits de l’homme utilisent le dialogue dans deux domaines: le processus de communication qui garantit le consentement et les accords communautaires, et les méthodologies psychosociales-éducatives constructionnistes. Dans son processus de consentement durable, l’approche multiculturelle des droits de l’homme permettait une traduction de valeurs distinctes et atténuait la résistance à l’éducation sexuelle dans les écoles/cités participantes. Elle est ainsi parvenue à faire aboutir des notions d’égalité et de protection du droit à une éducation sexuelle globale qui ne rompt pas la solidarité de groupe et garantit l’acceptabilité des différences.

Resumen

La educación sexual, sus protocolos y planificación dependen de un siempre cambiante ambiente político que caracteriza el campo de la sexualidad en la mayoría de los países. En Brasil, las perspectivas de derechos humanos influyeron en la respuesta del país a la epidemia del SIDA, e influyeron indirectamente en la aceptación del público de la educación sexual en las escuelas. Sin embargo, a partir del año 2011, a medida que surgieron múltiples movimientos fundamentalistas en la región, que produjeron recurrentes oleadas de respuestas negativas en todo lo relacionado con la sexualidad, tanto las políticas de salud como las educativas han empezado a dar marcha atrás. Este artículo explora los enfoques en la salud basados en los derechos humanos, y se centra en un marco multicultural basado en los derechos y en estrategias productivas para ampliar el diálogo sobre el consentimiento continuado a favor de la educación sexual. Los enfoques multiculturales de derechos humanos (MHR) son dialógicos en dos campos: el proceso de comunicación que garantiza consentimiento y acuerdos comunitarios, y las metodologías construccionistas psicosociales-educativas. En su continuo proceso de consentimiento, el enfoque de MHR permitió una traducción específica de los valores, difundió la resistencia a la educación sexual en las escuelas/ciudades de los participantes y logró sostener las nociones de igualdad y protección del derecho a una educación sexual integral que no rompe los lazos de solidaridad grupal y garantiza la aceptación de diferencias.

Introduction

Sexuality education, its protocols and planning are contingent upon an ever-changing political environment that distinguishes the field of sexuality in most countries. In Latin America, the 1980-1990s transition from authoritarian regimes to democracies resulted in innovative human rights-based public policies that have fostered the notion that promoting and protecting health are inextricably linked to the promotion and protection of rights. In Brazil, this perspective has shaped the country’s response to HIV/AIDS, and indirectly influenced the public acceptability of sexuality education in schools. Since 2011, however, as multiple fundamentalist movements emerged in the region, leading to recurrent waves of backlashes in all matters related to sexuality, both health and educational policies have begun to crawl backwards. Concepts of “citizenship” (including “sexual citizenship”) which were central to health policies of the previous decades are now subject to challenges which have come to characterize the current political environment. Unexpectedly, Brazil seems to be now an emblematic case of backlash.Citation1,2

In 1996, as the country embarked on a progressive public health response to the HIV pandemic, the Brazilian Ministry of Education, under the umbrella of the Health and Prevention in Schools project, the SPE (Saúde e Prevenção nas Escolas), led the implementation of sex education as a crosscutting critical issue in schools’ curricula in 27 states of the federation (and around 600 cities).Citation3 For almost two decades, SPE disseminated preventive information, promoted condom and contraceptive use, and the alleviation of sexuality-related stigma and discrimination. Its inter-sectoral effort emphasized the right to scientific information, the need to think and talk about gender relations and sexual diversity, and fostered non-discrimination and citizenship education.Citation4 The SPE perspective included harm reduction along with the promotion of a “culture of peace” (non-discrimination and non-violence) by not allowing abstinence-only programs in public schools, and by inspiring private schools to launch initiatives focusing on condom use and, when acceptable, making condoms available on campus.

However, the religious scenario has shifted, due to a growing conservative, and primarily Evangelical, constituency. Per the 1980-Census, 90% of Brazilians were Catholics and, throughout the decade’s democratization process leading to the 1988 Constitution, a Catholic liberation theology movement played a key role in the alliance for human rights-based policies, which were supported by grass-roots organizations as well as prominent bishops. In 1989, however, the Vatican began to replace “pastoral” bishops and organizations with “canonical” and vaticanist groups – an instrumental move by the Vatican in dismantling the liberation theology movement and influencing sexuality policies as the response to HIV/AIDS.Citation5 The 1990s saw the rise of new Evangelical movements, disseminated by large TV and radio networks and benefiting from tax exemption policies. The 2010 Census reports that the Evangelicals grew from 15% in 2000 to 22% in 2010 (Catholics were 65%, and non-religious 8%).Citation6 Evangelical movements resort to conversion methods that emphasize other faiths as “infidel” or “demonized”, and have been a force in action aiming for political power, as seen in other parts of the world.

In June 2015, a national action of conservative Christian-Catholic politicians (the “bible coalition”) successfully eliminated any mention to “gender”, “diversity” and “sexuality” from numerous municipal educational plans. At the national level, the same coalition is proposing to redefine homosexuality as a disease, and to criminalize HIV transmission and health professionals who care for women suffering from complication of unsafe abortions. In this orchestrated backlash – a Brazilian version of what Richard Sennet calls the “politics of the tribe (rather than the city)”Citation7 – even major metropolitan areas and state capitals have been hard hit by a political movement that will affect the future of generations to come.

Unfortunately, the consequences of two decades of political mobilization of conservative Christians might still get worse: prevention education and condom use are decreasing and HIV incidence among young people (15-24 years old) born in the 1990s is 3.2 times higher than young people in this same age cohort born in the 1970s; for young men who have sex with men (MSM) it is 6.4 higher.Citation8 As in many countries,Citation9 HIV incidence in Brazil is growing mostly among young girls and young MSM, and 12,000 pregnant women annually are estimated to be HIV +,Citation10 while transmission from mother-to child has stabilized at around 3.5% since 2008. Moreover, a recent analysis of the SPE-Health and Prevention in Schools program implementation shows that, typically, most public schools around the country invite “experts” (mostly health professionals with no experience in sex education) to present on the risk and dangers of sex, and not on prevention.Citation11

More broadly, a growing emphasis on Christian values, while without clearly naming it as such, has been observed in various presumed secular institutions – schools and reproductive health services.

Human rights-based approaches to health postulate that increases in human rights violation or negligence will result in greater psychosocial suffering, morbidity and mortality.Citation12 In the global scenario, evidence has already shown the negative impact of the epidemic of bad laws that criminalize sexualities, practices and populations.Citation13 As Sennet puts it, tribalism can be destructive; the challenge is “to respond to others on their own terms” while building cooperation among people who value diversity and differ religiously, economically, racially, ethnically and on how they conceptualize gender and sex.Citation7

This article will focus on a multicultural rights-based framework and on productive approaches to broadening the dialogue about sustained consent to sexuality education.

To expand and sustain access to comprehensive sexuality education we needed some answers: how to dialogue with different concepts of femininity, masculinity and conjugality in a school setting – with students, parents, teachers and different educational authorities? How to promote the right to prevention and sexual and reproductive rights of students with different religious and ethical affiliations? The continuous process of developing acceptability to an HIV prevention and reproductive health promotion project will be presented in this article. Sustained consent is the key process indicator of stronger and lasting sexuality education programs: consent resulting from community involvement and participation that fosters acceptability – two key principles of the human rights-based approach to health that informs this framework.Citation14,15

Framework

This framework was built on social constructionist perspectives on sexuality, inspired by gender theories and local experimentations of constructionist popular education in HIV prevention and sexuality education in the 1990s.Citation16,17 With the goal of reducing the prevalence of HIV and HIV-related stigma, improving understanding of gender, sexual, ethnic and racial diversity, and promoting an enabling school learning environment, the early 2000s saw an increase in projects fostering respect for diversity in schools.Citation18 Both were predominately inspired by critical pedagogies and the Latin American tradition that the work of Paulo Freire represents.Citation19

To answer some of our critical questions, the human rights-based approach to healthCitation20 was refined via pilot sexuality education projects.Citation14 In contrast to outcome-focused methodologies (such as contraceptive and condom use), both constructionist and human rights-based approaches focus on processes.Citation12,14,15

The multicultural human rights (MHR) approach

Santos'sCitation21 concept of multicultural human rights is the basis of the MHR approach to sexuality education: it deals with the dilemma of recognizing difference and affirming equality in the promotion of rights, without losing sight of the universal and particular dimensions of human rights.

To reinvent human rights as an emancipatory language, Santos points out that different concepts of human dignity coexist in different cultural traditions: such as dharma, in the Hindu tradition, or umma in the Islamic tradition. Each cultural tradition considers their own values to be valid (and superior), independent of the context; in other words, in each culture’s perspective, all other cultures will always be incomplete. Additionally, all cultures tend to distribute people and social groups into two primary hierarchies: that of equality between homogenous units (citizens or foreigners) and that of difference that produces a hierarchy between different social identities (between sexes, between ethnicities, between religions).

Therefore, recognizing the incompleteness of our own cultures and traditions is the necessary foundation of cultural humility: we live in the process of articulated globalizations, interacting with different cultural traditions, all aiming for universal validity: “speaking from a self-appointed place of universality”.Citation22 To realize ambitions for equality, as well as peace and justice, we will always depend on a dialogue between different conceptions of human dignity – an intercultural dialogue.

Santos's “diatopical hermeneutics” provides three principles for action. Firstly, dialogue should qualify and render mutually intelligible (“translating” different positions) the different concepts of human dignity built into discourses and traditions. Secondly, interpretations must recognize the incompleteness of all cultural traditions (and as such, of all discourses about sexuality). In the process of dialogue inevitable tension will emerge as history constructs hegemonies, powers, and inequalities. Finally, openness for agreement may happen when two intercultural imperatives can be recognized:

| a. | of the different versions, the version that goes furthest in recognizing the other, representing the broadest circle of reciprocity, should be chosen; | ||||

| b. | to defend equality every time difference generates inferiority and defend difference when equality results in de-characterization. | ||||

Contrary to the initial reaction of education officials and school authorities who feared opposition, these two avenues, presented and discussed throughout the continuum of the consent process, contribute to sustained dialogue.

Another aspect of the MHR approach to sexuality education is recognition that we are all partners in rights: in considering oneself as a rights holder and an active human rights agent, one should symmetrically recognize that right in others as well; otherwise we would be describing a privilege rather than a right!Citation23

Fostering dialogues based on diatopical hememenutics, promoting solidarity and reciprocity among rights holders, MHR processes respect the four moments, as described in Box 1.

BOX 1 Four moments of Multicultural Human Rights approach to sexuality education

| 1) | Defining the interaction as a collaboration of specialists throughout an enduring consent process. Sexuality education professionals carry technological-scientific knowledge that, by definition, is a temporary expertise. This techno-scientific expertise should be constantly updated and interact with people’s day-to-day knowledge and expertise in their daily life. So, the following moments are collaborative tasks with participants. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2) | Analysing the sexuality-rights dynamic for each group and community.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3) | Analysing the quality of services related to sexuality in different dimensions.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4) | Identifying daily life inequalities, at least:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In synthesis, multicultural human rights-based (MHR) sexuality education is a psychosocial intervention that promotes understanding of the cultural and social dimensions of sexuality, expands access to prevention tools (including testing, hormonal and antiretroviral based ones) necessary to the practice of self-care and care for others, and improves sexuality education through dialogues that recognize differences without reinforcing inequality and rights violations, thus producing equity and solidarity. As an alternative to more prevalent methodologies based on promotion of condom and contraceptive use or abstinence only programs, MHR methodologies are dialogical in two domains: the communication process that guarantees consent and community agreements (per MHR perspective synthetized above); and the constructionist psychosocial-educational methodologies, developed from the critical and emancipatory pedagogies since the 1990s.Citation12,14,15,17,18,24

Participants are treated as citizen-subjects (rights holders) who join in the dialogue with scientific experts and knowledge to co-construct their own wellbeing. Such dialogue incorporates diverse values, trajectories, and examines social and programmatic contexts that may mitigate participants' vulnerability to unintended consequences of sexual behaviour – in a mutually respectful environment, at school or in health services.

Methodology

The focus of this article is the process of obtaining and sustaining consent for an unintended pregnancy and HIV prevention projectCitation25 in public high schools, including consent from education officials, the adult school community (school managers, parents and teachers), and students.

The study on the acceptability of the program, growing participation, and sustainability of the continual consent process – analysed through the MHR framework, and developed on previous projectsCitation14,26 – was conducted and led by the principle investigator and first author of this paper. Research team members conducted rigorous observations and registered the process into field notes, films and tapes, when accepted and after signed informed consent.

Dialogical meetings and interviews with education officials triggered the project. After obtaining project approval at the federal and regional levels, we sought approval from school principals and pedagogical coordinators. Through a presentation of the MHR framework, the research team engaged officials at all levels and members of every school community in discussions about the core principles of community participation and autonomy. These conversations followed the project’s methodology by introducing the notion of solidarity underlying human rights perspectives, while stressing the notion of respect for differences. A key topic introduced by the research team was the constitutional secularism that requires respect for different religions and values.

In 2013, two meetings at the Ministries of Health and of Education generated a common understanding of how to navigate the current political context while protecting the SPE/ Health and Prevention in Schools projects. The first agreement was to protect the identity of participating cities and public schools, unless the entire school community decided otherwise. The second step was to meet with local education officials, and subsequently with the school community, to engage them in the consent process.

Obstacles and limits

Fear of possible negative reaction from both parents and representatives of the Evangelical faith, so-called “Evangelics”, were noted as obstacles in two cities. Officials at these cities refused the project without ever returning the agreement letter (unsigned) to the research team, or even communicating a candid “no”; informal talks implied that local elections and the growing fundamentalist political mobilization were the issue.

Seven public schools agreed to participate in the project, expressing but not representing the diversity of the country. These schools were in impoverished settings as described below:

(A) a coastal city known for its ecotourism and as a Catholic pilgrimage site; (B) an inland town characterized by agro-business and as a transportation hub in the region, with strong Evangelical communities; (C) rural isolated villages in the Sierra, originally an Afro-Brazilian slaves refuge, resistant to state policies and home to a growing austere Evangelical community; (D, E, F, G) impoverished territories in urban areas.

In each setting, three to five meetings were conducted with school managers, and at least one meeting was conducted with local health and educational officials. Two to four “conversation circles” were held with parents and teachers to reach consent for the project, and many others with principals, teachers, parents, and students engaged in the consent process along the way.

The first obstacle the research team faced was time management, which can limit the use of the MHR methodology. Conversations about daily life experiences and diatopical hermeneutics require availability of time to talk and listen to stories. The methodology is centred on participation by affected “citizen-subjects” – or rights-holders in charge of their sexuality and self-care – which guarantees all other dimensions of MHR methodology, especially the acceptability of the proposed actions focused in this article; not a simple task in backlash contexts!

The second obstacle was the lack of financial resources to respond to schools that wanted to expand the project, under our supervision, after the end of the 18-month study. We were able to expand it to two cities, and chose cities B and C where teachers incorporated sexuality education into curriculum planning (2015-2016).

Sustaining the school community consent

The need for additional meetings in the beginning of the process characterized greater resistance to consent. In some cases, however, growing interest in the project and community involvement led to an increased number of meetings.

The most productive first approach in all schools was to talk about the history of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948. Questions like “where do Human Rights come from, what do they mean to you?” prompted some parents and teachers to talk about experiences of genocide or extreme violence in the history of their own community. Others recalled the first atomic bombs in Japan, as an “example of the final destructive capability of non-mediated human conflicts” (parents-teachers-students meeting conclusion). Participating parents usually had low levels of literacy. But even in distant and isolated mountain and rainforest villages, parents were able to articulate what they consider a human right, a sign of a positive cultural change in Brazil, following the adoption of the 1988 human rights-based Constitution, and the end of the dictatorship.

It was powerful to open the dialogue with a collective construction of a list of human rights, or the reading of the Declaration Preamble: people are born free and equal in dignity, with inalienable rights that establish liberty, justice, and peace in the world.

Project leaders focused the debate on the psychosocial and structural factors that produce power hierarchies (or lack thereof), fostering collective awareness to cope with them. The challenge was to address equality and the right to comprehensive sexuality education without breaking group solidarity, and securing acceptability of all different views. Participants were constantly invited to engage in the dialogue as “rights holders” (sujeito de direitos, agents), in a secular environment. “Agent” conceptualizes an individual who is doing or being something: as agents of rights, participants should be guided by the principle of reciprocity.

By far the most helpful question to overcome resistance from city officials, school principals, community leaders and parents was: “is the right to be literate on prevention and self-care, and to be informed about latest scientific consensus in a non-compulsory sexuality education, to be taken from all students because some would not allow their children to participate?” It was an excellent entry point to discussing “the right to health” as the obligation of states to ensure access to comprehensive health care and education, which in Brazil is a universal (“free and for all”) constitutional right.

Again and again we observed how sexuality, and the idea of sexual rights, is one of the most emblematic arenas for disputing notions of equality, liberty and dignity.Citation27 Parents’ participation was mostly on behalf of their children’s access to sexuality education and prevention in schools: “we do not know how to do it!”; “the school needs to support us in these issues”. Opposition to the program was never voiced by parents. Adults who pondered that sexuality education may lead to sexual activity listened attentively to productive questions: “is it worse than watching TV and the Internet?” Or “can you control what they exchange via social media and talk with their friends?”

Some adults expressed concern on how to deal with non-traditional gender identities or non-heterosexual orientation, and the most productive question for debate was: “how do you ensure that young people who want to delay sexual debut (or are not interested in sex) do not become exposed to bullying, stigmatization and discrimination for being “asexual”, a discrimination similar and shared with LGBT students, as observed in all schools? How do we make asexuality as well as homosexuality and diverse gender identities and gender performances a part of the dialogue about equality and prevention?”

“Good to know who our students and children are and what they really do”

Discussion about national data on average age of sexual debut, condom use, HIV prevalence and pregnancy rates among adolescents, presented to participants from a human rights perspective, was a turning point for consent and greater participation of the school community.

In meetings at all levels – with local officials, teachers, parents, and parents together with their children – the research team highlighted that while values and religious faith may affect opinions and attitudes about sexuality, the diversity of sexual behaviour among Brazilian youth is a fact, as shown in all national survey data. Adolescents’ different religious affiliations do not produce different sexual practices, even when we survey the everyday life of youth engaged in the churches.Citation14

In all schools, it became evident that sexuality education is needed. For example, when asked when sexuality education in schools should begin, students didn’t raise their hands to the ages 18, 17…16 years old: the majority put the ideal age between 12 and 14. Allowing adults and local government education and health officials to attend these meetings and learn about students’ views was instrumental in garnering support for the project.

These meetings helped to clarify to all involved that the panic over AIDS of the 1980-90s had been replaced with a misconception “that AIDS is no longer a problem, (because) it is controlled". The meetings also made clear that emergency contraception had been adopted by young girls.

Consent became stronger after the initial results of the project’s knowledge, beliefs and practices survey on sexuality and prevention showed local gaps when compared to national data. The survey complied with obtaining required parental consent, and used palmtop-handheld devices to collect anonymous individual data. Adherence to the survey and study activities was high and reflected the schools’ profiles: 42% Catholics, 37% Evangelicals, 14% declared non-religious and 7% were affiliated to other religions. Mean age was 16.7 years old, 59% were girls and 41% boys; 34% students self-reported as white, and 66% as non-whites (afro-Brazilians, indigenous and mixed).

Similarly to national data for 14-19 years old, results in all schools included: 97% support for sexuality education and access to condoms; mean age of sexual debut was 14.6 years (15 for girls, 14.3 for boys); 69% of students reported condom use at the first intercourse; and 10-17% of students reported sex with a person of the same sex at least once. Most believed sex education should begin around 12 years old; 20-40% do not know how to use a condom or where to get tested for HIV; and 40% of students declared “love and trust in the partner” as a method of self-protection. Religious affiliations were not a significant difference in any of these factors.

The adult school community considered that the results “require attention” and expressed their “faith in science” and that there is “need to do something together”. Acceptability was the first result of the process in schools, where high participation indicated that community involvement is viable.

In one city, and in contrast to parents’ consent, teachers’ adherence to capacity building and students’ enthusiasm, the school principal tried to limit engagement by parents and teachers by raising barriers to project implementation, which eventually lost momentum.

Sexual risk and health or sexual rights and agents (sujeitos)?

Through teacher training and students’ involvement as “project-agents”, public health discourse about the risks and dangers of sexual behaviour and the prevailing normative definitions of sexual health as (good) behaviour-to-be-modelled gave way to lively discussions with young people. This is the latest consent stage expected in the framework in this timeframe, a good indicator of community engagement and participation.

As anticipated in the MHR framework, each school adopted different activities, which called for collaboration and co-production with the school community. Activities from the SPE and other similar projects were frequently reinvented, respecting the local context. Greater community participation led to greater time for activities and more activities to be built into the curriculum, and to continuous consent and community engagement.

Key curriculum activities included: 1. small group discussions using their own words, knowledge and imagination to describe their bodies and sexualities and discuss with teachers and peers how heterosexual and homosexual couples can prevent HIV and other STIs. 2. art projects using clay or local flour paste to represent “reproductive and sexual body parts” and then talking about local sexual culture and processing the activity by decoding meanings and paraphrasing students. 3. Involving participants in creating things, words, and scenes or scenarios, which then come alive through short stories about love, dating and sex as socially compulsory, or about real or imaginary scenarios that may lead to HIV infection, unintended pregnancy or intimate partner violence, followed by decoding and processing. 4. in larger group sessions using films to discuss specific scenes. 5. engaging students in competitions on “how fast girls versus boys fill condoms as balloons” showing how condoms take time to break and how big they get.

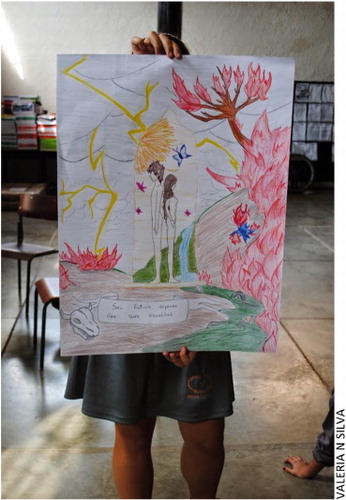

Students also interviewed elderly family members on their experiences with sexuality education when they were teenagers, building a historical perspective. In school festivals, the students produced images to decorate a condom dispenser, some using their religious imagery.

Differences in prevention knowledge among boys and girls and discriminatory attitudes in relation to non-normative sexual scripts and trajectories, such as becoming pregnant, were the way to discuss gendered power and relations in most schools; in two schools, sexual violence and abuse was the emergent gender issue, while in one school a transgender girl’s process of coming out was the entry point for this debate.

In metropolitan territories, unknown sexual scenes and scriptsCitation28 drew special attention. We learnt about almondegas (meatball) and the lavajato (carwash). Meatball is a close huddle of dozens of people in the dancing crowd signified as pure flesh to be sexually consumed anonymously while dancing. Girls without pants also stay put along the walls at funk dancing parties (pancadão), which are very popular in favelas, waiting for different boys to wash them inside with “their potent squirts”, as in carwash places. Young boys and girls who adhere to these styles of scripts go to schools, and we could hear their stories of using emergency contraception or facing discrimination for getting pregnant. One was escaping from very strict and recently converted Evangelical parents, and confronting her socialization.

Final considerations

The history of sexuality has definitely been the “history of a subject in constant flux”.Citation29 Flux is also a good term to describe community engagement in sexuality education through continuous consent that builds acceptability, key aspects of its sustainability.

In the MHR approach, sexuality and sexuality education are both conceived as fluid and contextual-dependent social activities. In its continuous process of consent, this approach allowed for distinct values translation and bypassed the resistance to sexuality education in the participant schools/cities; non-participant families and adolescents did not oppose the project in their school. Data collected with the active participation of teachers and students, bypassed the denial of (unacceptable) adolescents’ active sexuality, an argument used to suspend sexuality education and quite prevalent in other parts of the world,Citation13 except for Western European countries.Citation30 The normative and moralizing risk-preventive models of recent years were challenged: sexual scripts cannot be the same for everyone, or for every sexual scene or context, and every moral and religious perspective; sexual citizenship should not be reduced to “consumers' rights” (right to a predefined sexuality, predefined good behaviour). Education (as health) is not to be consumed but co-produced.Citation19

The language of human rights has successfully mediated the debate about different definitions of autonomy and dignity and the social organization of sexuality. The rights language showed that definitions of “desirable” or “unacceptable” are a discursive construction, particular to a community and a historic moment. Rights fulfilment was frequently related to the programmatic responsibilities of local governments, as the lack of adolescent-friendly testing sites.

UN experts and evidence have supported human rights-based sexuality education projects, such as MHR.Citation31 Being recognized and recognizing others as holders of rights has increased participation and guaranteed diversity in other projects, as in a project that responded to abstinence-only programs in the USA.Citation32 But each country history should be considered, as it does make a difference to how we conceptualize and experience human rights approaches.

The strongest limitation to adopting this approach is how people conceptualize human rights: multicultural human rights (MHR) approaches are productive where political history emphasizes notions of dignity associated with social justice and defines citizenship in terms of rights. Still, where human rights approaches do not value the reciprocity principle, and one group, speaking from a self-appointed place of universality, claims exclusive validity of their values – as do those who adopt (or fear) Christian fundamentalist movements in the current Brazilian context – the rights of those with different values will be affected.

Given that there is no universal sexuality education that is flawless, different approaches can be more or less damaging to particular students and social groups.Citation33 A central aspiration of MHR-based sexuality education is to prevent and mitigate damages and sustain a strong participative program ensuring adolescents’ rights to a comprehensive sexuality education.

In this web-connected world, growing diversity and alternative sexualities, gender identities and performances that require recognition within sexuality education will not end by the force of law or religious preaching. Backlashes also open into opportunities to develop productive resistance and innovation. We hope that this multicultural human rights approach can inspire other initiatives in the same direction: difference and diversity ought not be translated into inequality.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Louisa Allen and the reviewers for their comments and the kind support and mentorship of Magaly Marques during the revision process.

We would also like to acknowledge our collaborators and the research team in the study sites: Ximena Pamela Diáz Bermúdez, Edgar Hamman, Maria Cristina Antunes, Ricardo Casco, Grazielle Tagliamento, Mauro Niskier Sanchez, Bárbara Ribeiro de Souza Dias, Laura Malaguti Modernell, Joao Paulo Fernandes, Isabelle Picelle, and Clelia Prestes.

The principal investigator of the research project “Avaliação da estratégia de prevenção da gravidez não planejada e das DST / AIDS por meio da inclusão de dispensadores de preservativos em escolas de ensino médio” was Vera Paiva and the project was sponsored by the Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa (CNPq/Universal &Pq1C). Funds were received from the Ministry of Health/DN AIDS, UNESCO and UNFPA.

References

- M. Malta, C. Beyrer. The HIV epidemic and human rights violations in Brazil. JIAS. 16: 2013; 18817.

- Silva. Sex education in the eyes of primary school teachers in Novo Hamburgo, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Reproductive Health Matters. 21(41): May. 2013; 114–123.

- Brasil/Ministério da Educação. Home Pagehttp://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?Itemid=578. (& accessed in April 2015).

- Brasil/Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Saúde e prevenção nas escolas: guia para a formação de profissionais de saúde e de educação. 2006; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília.

- V. Paiva, A.P. Ferrara, R. Parker. Religious Coping and Politics: Lessons from the Response to Aids. Temas em Psicologia. 21(3): 2013; 883–902. (http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/tp/v21n3/en_v21n3a10.pdf).

- F. Teixeira, R. Menezes. Religões em movimento: o censo de 2010. 2013; Petrópolis: Vozes.

- R. Sennet. Together. 2012; Yale University Press: London/New York.

- A. Grangeiro. A política de saúde para o enfrentamento da aids. Apresentação na audiência pública. 11 de junho de 2015. 2015; Câmera dos Deputados: Brasília.

- P. Idele, A. Gillespie, T. Porth. Epidemiology of HIV and AIDS among adolescents: current status, inequities, and data gaps. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 66(Suppl. 2): 2014; S144–S153.

- Brasil/Ministério da Saúde. Boletim Epidemiológico HIV/Aids. 2014. (Ano III (1)).

- C.A. Lombardi. Relatório Final da Avaliação (produto 4). 2014; UNESCO: Brasília.

- V. Paiva. Social Psychology and Health: Socio-Psychological or Psychosocial? Innovation of the Field in the Context of the Brazilian Responses to AIDS. Temas em Psicologia. 21(3): 2013; 551–569.

- V. Paiva, L. Ferguson, P. Aggleton. The Current State of Play of Research on the Social, Political and Legal Dimensions of HIV. Cad. Saúde Pública, Rio de Janeiro. 31(3): 2015; 477–486.

- V. Paiva, J. Garcia, A.O. Santos. Religious communities and HIV prevention: an intervention-study using human rights based approach. Global Public Health. 5: 2010; 280–294.

- S. Gruskin, D. Tarantola. Universal access to HIV prevention, treatment, and care: assessing the inclusion of human rights in international and national strategic plans. AIDS. 22(Suppl. 2): 2008; S123–S132.

- V. Paiva. Sexuality, condom use and gender norms among Brazilian teenagers. Reproductive e Health Matters. 2: 1993; 98–109.

- Paiva V. Gendered scripts and the sexual scene: promoting sexual subjects among Brazilian Teenagers. In: Parker, Aggleton (Org.). Culture, Society and Sexuality. A reader. 2nd edition. New York: Routledge. 2007. pp. 427-442.

- Centro Latino-Americano em Sexualidade e Direitos Humanos /CLAM. Diversity in School. 2012; CEPESC: Rio de Janeiro.

- M. Gadotti, C.A. Torres. Legacies. Paulo Freire: Education for Development. Development and Change. 40(6): 2009; 1255–1267.

- S. Gruskin, D. Tarantola. Health and Human Rights. S. Gruskin, M.A. Grodin, S.P. Marks. Perspectives on Health and Human Rights. 2005; Routledge: London.

- B.S. Santos. Subjetividade, cidadania e emancipação. Santos. Pela mão de Alice. O social e o político na pós-modernidade. 10th ed., 2003; Cortez: São Paulo.

- Santos BS, Nunes JA. Introdução. Para Ampliar o cânone do reconhecimento. In: Santos (Org.) Reconhecer para libertar: os caminhos do cosmopolitismo multi-cultural.Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira. 2003. pp 23.

- J.R.C. Ayres, V. Paiva, I. Franca-Jr. From Natural History of Disease to Vulnerability: changing concepts and practices in contemporary public health. Sommers Parker. Routledge Handbook of Global Public Health. 2010; Routledge: London, 98–107.

- V. Paiva. Analysing sexual experiences through 'scenes': a framework for the evaluation of sexuality education. Sex Education, Londres. 5(4): 2005; 345–359.

- V. Paiva, E. Merchan-Hamann, X.P.D. Bermudez. Avaliação da Estratégia de Prevenção da Gravidez não planejada, das Dst / Aids em Escolas De Ensino Médio. Projeto CNPq/Universal. 2012; Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa: Brasil.

- Paiva V. Everyday Life Scenes: methodology to understand and reduce vulnerability in a human rights perspective [Cenas da Vida Cotidiana: Metodologia para Compreender e Reduzir a Vulnerabilidade na Perspectiva dos Direitos Humanos]. In: Paiva, Ayres, Buchalla. (Org.). Vulnerabilidade e Direitos Humanos. vol I .Curitiba: Juruá Editora, 2012, p. 165-208.

- J. Garcia, R. Parker. From global discourse to local action: the makings of a sexual rights movement?. Horizontes Antropológicos. 12(26): 2006; 13–41.

- W. Simon, J.H. Gagnon. Sexual scripts. Aggleton Parker. Culture, society and sexuality. 1999; UCL Press: London, 29–38.

- J. Weeks. The importance of being historical. Aggleton Parker. Routledge handbook of sexuality, health and rights. 2010; Routledge: New York, 28–36.

- The Alan Guttmacher Institute (AGI). Can more progress be made? Teenage sexual and reproductive behavior in developed countries. Executive Summary. 2001; AGI: New York.

- H.D. Boonstra. Advancing sexuality education in developing countries: evidence and implications. Guttmacher Policy Review. 14(3): 2011. (https://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/gpr/14/3/gpr140317.html).

- M. Marques, N. Ressa. The Sexuality Education Initiative: a programme involving teenagers, schools, parents and sexual health services in Los Angeles. Reproductive Health Matters. 21(41): 2013; 124–135.

- T. Jones. A Sexuality Education Discourses Framework: Conservative, Liberal, Critical, and Postmodern. American Journal of Sexuality Education. 6(2): 2011; 116.