Abstract

In the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, arrests and imprisonment of Palestinian men in their early adulthood are common practice. The Public Committee Against Torture in Israel (PCATI) collected thousands of testimonies of Palestinian men allegedly tortured or ill-treated by Israeli authorities. There are many types of torture, sexual torture being one of them. This study is based on the PCATI database during 2005-2012, which contains 60 cases – 4% of all files in this period – with testimonies of alleged sexual torture or ill-treatment. It is a first in the investigation of torture and ill-treatment of a sexual nature, allegedly carried out by Israeli security authorities on Palestinian men. Findings show that sexual ill-treatment is systemic, with 36 reports of verbal sexual harassment, either directed toward Palestinian men and boys or toward family members, and 35 reports of forced nudity. Moreover, there are six testimonies of Israeli officials involved in physical sexual assault of arrested or imprisoned Palestinian men. Physical assault in most cases concerned pressing and/or kicking the genitals, while one testimony pertained to simulated rape, and another described an actual rape by means of a blunt object. The article provides illustrations of the various types of sexual torture and ill-treatment of boys and men in the light of existing literature, and recommendations.

Résumé

Dans le contexte du conflit israélo-palestinien, les arrestations et emprisonnements de jeunes adultes palestiniens sont fréquents. Le Comité public contre la torture en Israël (CPTI) a recueilli des milliers de témoignages d’hommes affirmant avoir été torturés et maltraités par les autorités israéliennes. Il existe beaucoup de types de torture, la torture sexuelle étant l’un d’entre eux. L’étude est fondée sur la base de données du CPTI de 2005 à 2012, qui contient 60 cas - 4% des dossiers de cette période - avec des témoignages faisant état de tortures ou de mauvais traitements sexuels. C’est une première dans l’enquête sur la torture et les mauvais traitements de nature sexuelle, qui auraient été perpétrés par les autorités israéliennes de sécurité sur les Palestiniens. Les conclusions montrent que les mauvais traitements sexuels sont systématiques, avec 36 récits de harcèlement sexuel verbal, à l’endroit des hommes ou garçons palestiniens ou de membres de leur famille, et 35 informations faisant état de nudité forcée. De plus, il y a six témoignages de fonctionnaires israéliens ayant participé aux sévices sexuels des Palestiniens arrêtés ou emprisonnés. Dans la plupart des cas, les sévices physiques consistaient en pressions et/ou coups sur les organes génitaux, alors qu’une déposition évoque une simulation de viol et une autre décrit un viol véritable à l’aide d’un objet émoussé. L’article illustre les différents types de torture sexuelle et de mauvais traitement des hommes ou garçons à la lumière des publications existantes, puis il formule des recommandations.

Resumen

En el contexto del conflicto israelí-palestino, los arrestos y encarcelamiento de hombres palestinos en su adultez temprana son una práctica común. El Comité Público contra la Tortura en Israel (PCATI) recolectó miles de testimonios de hombres palestinos alegadamente torturados o maltratados por las autoridades israelís. Existen muchos tipos de tortura; uno de ellos es la tortura sexual. Este estudio se basa en la base de datos del PCATI durante 2005-2012, que contiene 60 casos -el 4% de todos los expedientes durante este período- con testimonios de tortura sexual o maltrato alegados. Es el primero en la investigación de tortura y maltrato de naturaleza sexual, alegadamente perpetrados por las autoridades de seguridad israelí contra hombres palestinos. Los hallazgos muestran que el maltrato sexual es sistémico, con 36 informes de acoso sexual verbal, ya sea dirigido a hombres y niños palestinos o a miembros de su familia, y 35 informes sobre desnudez forzada. Más aún, existen seis testimonios de funcionarios israelís involucrados en la agresión sexual física de hombres palestinos arrestados o encarcelados. En la mayoría de los casos, la agresión física consistía en presionar y/o patear los genitales, mientras que un testimonio era sobre una violación simulada y otro describió una violación real con un objeto desafilado. El artículo expone ilustraciones de los diversos tipos de tortura y maltrato sexuales de hombres y niños a la luz de la literatura disponible, y recomendaciones.

Introduction

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is an enduring armed conflict receiving much international attention. In the realm of this conflict, large numbers of Palestinian men are arrested and detained by Israeli security forces each year. In 2014 alone, “Israeli authorities held some 500 Palestinians in administrative detention without trial; thousands of other Palestinians were serving prison terms”.Citation1

Torture and ill-treatment of detained Palestinians are prevalent,Citation2–8 even though Israel has ratified the UN Convention Against Torture (1986/1991), prohibited the use of several forms of torture (1999),Citation9 and promulgated national laws against (sexual) harassment and abuse.Citation10,11 Israeli authorities admit interrogators employ “exceptional” interrogation methods and “physical pressure” in “ticking bomb” situations, but claim that this is done out of “necessity” and do not call these methods “torture”. Others have claimed that the term “ticking bomb” is used much too broadly and that this ruling de facto institutionalizes torture by Israeli authorities.Citation2,3,9

According to the United Nations Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment,Citation12

“(T)orture means any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions.”

The difference between torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment (in short, “ill-treatment”) lies in the intensity of the suffering and the purpose, but for practical reasons international bodies relate to the two prohibitions without differentiation.Citation13 The reason for doing so is that there is a cumulative effect in which a combination of incidents of ill-treatment or prolonged periods of ill-treatment can amount to torture.Citation9 Contextual factors need to be taken into account as well, since they mediate the perceived severity of the stressor and whether it could be considered torture.Citation14 Moreover, an international study focusing on the differentiation between ill-treatment and torture concluded that ill-treatment in captivity does not seem to be substantially different from physical torture in terms of the severity of mental suffering they cause, the underlying mechanism of traumatic stress, and their long-term psychological outcome.Citation15

The perpetrators involved in torture and ill-treatment are those concerned directly with keeping public order in Israel, but occasionally physicians are reported as complicit in torture.Citation7,8 Torture is generally concealed behind prison walls, but every so often victims of torture are brought to Israeli emergency rooms,Citation5 turn to a private lawyer and/or have their experiences documented by the Public Committee Against Torture in Israel (PCATI).Citation2 PCATI was established in 1990 as a non-governmental organization, acting to increase public awareness of torture during interrogations or under other circumstances, prosecute the guilty parties, and eliminate legal use of torture and ill-treatment. Its activities comprise legal advocacy, public engagement, and lobbying; it also functions as an information centre.

In Israel, victims of torture have the possibility to go to court and could be compensated if torture were established. However, in practice, torture allegations are dismissed without criminal investigation or rejectedCitation2,3,9 and perpetrators are cleared, though in rare cases soldiers are punished through a disciplinary system.Citation3 Rehabilitation and compensation based on allegations of torture are exceptional,Citation16,17 in spite of international recommendations.Citation12,18,19Footnote* In fact, financial settlements were reached only for cases that took place in the 1980s and 1990s and included a clause absolving the State from declaring the plaintiff a victim of torture.Citation20

As for the types of torture and ill-treatment, the 2014/2015 Amnesty International report states:

“Palestinian detainees continued to be tortured and otherwise ill-treated by Israeli security officials, particularly Internal Security Agency officials, who frequently held detainees incommunicado during interrogation for days and sometimes weeks. Methods used included physical assault such as slapping and throttling, prolonged shackling and stress positions, sleep deprivation, and threats against the detainee and their family. […] The authorities failed to take adequate steps either to prevent torture or to conduct independent investigations when detainees alleged torture, fuelling a climate of impunity.” Citation1

Sexual torture and ill-treatment of men

Sexual violence is often thought of as mainly directed toward women, but in the last decade there has been rising attention to sexual violence toward men in general, and in the realm of political conflict in particular. Forms of sexual torture described in the research literature range from verbal sexual harassment, through forced nudity, to severe forms of genital violence, such as squeezing the scrotum, rape, genital mutilation and castration.Citation30–32 Some studies relate to sexual violence in prisons;Citation21,22 others report on the detrimental mental health aspects, especially post-traumatic stress,Citation14,23–26 difficulties in treatment and rehabilitation of violated men due to taboo around the subjectCitation18,25,27 and some expose the human rights infringements by means of sexual abuse of men.Citation18,28,29

The manual on the effective investigation and documentation of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (“Istanbul Protocol”) claims that impairment of sexuality is among the many harmful sequelae of torture in general. In fact, sexual dysfunction is common among male torture survivors and may include decreased sexual interest, inability to trust a sexual partner, fear of or aversion to sexual activity, disturbance in arousal and erectile dysfunction. Sexual violence, in particular, which is often integrated in other forms of torture and ill-treatment, may cause a variety of both physical and psychological symptoms.Citation33

The Amnesty International report does not pertain to forms of sexual torture and/or ill-treatment toward Palestinians detained in Israel. An earlier study in 2003 noted that three human rights organizations involved in the Israeli/Palestinian conflict recorded almost no cases of sexual assault, but did file reports of lesser instances of verbal sexual harassment.Citation34 Since 2004, sexual torture in Israel has received media attention around the case of the then imprisoned Lebanese Amal leader Mustafa Dirani and his severe allegations of rape by Israeli security officers.Citation6 In 2015, the Supreme Court rejected the case, although it did not dismiss the allegations, claiming that as an enemy Dirani had no right to sue Israel.Citation35 But this is not the only case of sexual torture. In fact, it was maintained that there are quite a few Palestinian men complaining about sexual torture and ill-treatment during their arrest and imprisonment by Israeli authorities (Stroumsa R, Project Manager at PCATI, Personal communication, 1 June 2013).

Sexual rights include the understanding that everyone shall be free from torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment related to sexuality. These rights are grounded in basic human rights and essential for the achievement of the highest attainable sexual health.Citation36,37 There is extensive evidence of torture of Palestinian detainees (in arrest or prison) at the hands of Israeli security forces.Citation2,3,9 Sexual violence is often masked under the general term of “torture”,Citation38 and it seems probable that, if relevant questions were asked, more instances of sexual torture and ill-treatment would be found. This qualitative study responds to the call for more systematic collection of data and detailed studies in the field of sexual violence against men and boys in the context of armed conflict.Citation34,39–41 It aims at identifying sexual violence against male Palestinian detainees to reveal the extent and nature of sexual violence and ill-treatment among collected reports, as one component in a broader frame of torture perpetrated by Israeli authorities.

Method

PCATI’s archive includes thousands of testimonies (by Israelis, Palestinians, labour immigrants and other foreigners) of alleged torture and ill-treatment by Israeli security authorities. The procedure at PCATI regarding these allegations is to obtain an affidavit or a testimony, preferably as complete as possible, on the first visit. The interview is performed by a lawyer if the person is in prison, which is the most common situation, or by a trained field worker if the person is no longer detained, in which case it takes place in a mutually agreed location. The testimony is recorded in writing by the lawyer or field worker, either in Arabic or Hebrew, and the witness signs a consent form regarding its use for legal purposes, advocacy, or documentation and research. The testimony – if in Arabic, after translation to Hebrew – is then read by a third party, who categorizes the types of abuses in the testimony (beating, sleep deprivation, threats and so on). Those testifying do not receive any payment for their testimony. On the contrary, many of those no longer detained need to pay their own – for them, substantial – travel costs to reach someone from PCATI.

For this study, we searched the PCATI archive for the following relevant keywords: undressing, threat of sexual assault, and sexual assault.Footnote† We limited our search to testimonies of Palestinian men and boys submitted between 2005 and 2012. Testimonies were provided by Arab – predominantly Muslim – men living in different regions in the occupied Palestinian Territories (mostly from the West Bank). The selected testimonies were reviewed with a focus on the above-mentioned keywords and relevant parts marked. In each testimony, we counted only unique incidents of a sexual nature, i.e., incidents that were substantially different in circumstances; more incidents of the same nature by the same authorities were counted as one. We emphasize that these testimonies include documentation on many more incidents of torture and ill-treatment, but for the purpose of this study, we focused on those of a sexual nature.Footnote‡

We examined the diversity of sexual torture and/or ill-treatment, concerning a variety of authorities. We also looked to see whether there were any patterns of torture and/or ill-treatment of a sexual nature.

Findings

More than 1,500 testimonies were screened, of which less than 100 were by non-Palestinians. Of these, 60 testimonies (about 4%), – all provided by Palestinian boys and men concerning their detention, indicated incidents of sexual torture or ill-treatment. Many of these testimonies included more than one such incident. Thus, in total, 77 incidents of sexual torture or ill-treatment were identified. Incidents of sexual torture were embedded in other forms of torture and ill-treatment, not discussed here, occurring over altering periods of time, ranging from hours to weeks or even months.

Victims of sexual torture and ill-treatment were aged between 15 and 43 at the time of the incident, with the median age being 24. The majority (N = 26; 43%) were aged 20-29, while nine (15%) were minors and six (10%) were 18-19 years old. Eleven victims (18%) were aged 30-39, 2 victims (3%) were older, and information was missing for six victims (10%).

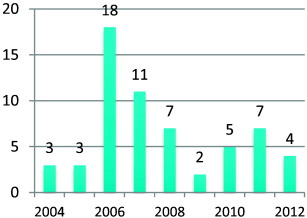

The occurrence of incidents of sexual torture and ill-treatment in our sample fluctuated across the years, with a minimum of two incidents in 2009 and a peak of 18 incidents in 2006 (see ). Fluctuations in the number of testimonies of sexual violence over the years do not necessarily reflect variation in the actual extent. They may relate to the overall number of testimonies during a specific year, the number of lawyers working in PCATI, their respective experience and capacity, the relations at a given point between PCATI and other prisoner organizations who may refer cases, access provided by Israel Prison Service, among other factors. As for the spike in 2006, this was a year of increased hostilities (Lebanon war, Israeli soldier taken hostage), but this could also be related to a particularly empathetic lawyer or to a general increase in attention to the issue of sexual abuse within the organization. As for the low in 2009, this year was characterized by a decrease in collected testimonies overall (Stroumsa R, Project Manager at PCATI, Personal communication, 30 August 2015). The time span between the incidents and the date of testimony ranged from 8 days to 3 years, with a median of 56 days.

Testimonies include allegations toward four different categories of perpetrators: a) soldiers and border police officers (25 reports), b) secret service officers (25 reports), c) police officers (8 reports), and d) jail officers (9 reports).Footnote§ Most allegations of sexual torture or ill-treatment concerned situations during arrest by either soldiers or border police officers and during interrogation. Although not rare, sexual torture allegations during police arrest or during detention either at police stations or in jail were less frequent. In two cases there was specific reference to perpetration by women (one secret service officer and one soldier). In all other cases, the perpetrators were identified as men or their sex was not mentioned.

For various reasons, only a few of the testimonies were submitted to court, and there were no convictions of perpetrators based on any of these testimonies, though at the time of writing one case is still in court.

The testimonies referred to three broad types of sexual torture and ill-treatment: verbal sexual harassment, which was most common; forced nudity; and physical sexual assault, which was least common (see Table 1). Following are illustrations for each type of torture/ill-treatment, translated from Hebrew, with the age of the victim at the time of the incident, and the alleged perpetrators. Names and places are disguised.

Table 1 Categories of sexual torture and ill-treatment

Verbal sexual harassment

Verbal sexual harassment seems relatively widespread among Israeli security authorities. In this category, we denote verbal sexual harassment in general, threats of rape, sexual humiliation with regard to family members and threats toward family members. The “Istanbul Protocol” for the investigation and documentation of torture states that “verbal sexual threats, abuse and mocking are also part of sexual torture, as they enhance the humiliation and its degrading aspects, all part and parcel of the procedure. […] There are often threats of loss of masculinity to men and consequent loss of respect in society”.Citation33

Reports of verbal sexual harassment include cursing and reference to victim’s sexual potency. In the next incident the detainee is shamed by relating his potency to an existing physical handicap.

“He started to humiliate me and told me that because of my handicap I won’t be able to have sex and that girls will not look at me.” (age 29, perpetrator: secret service)

We believe that verbal sexual harassment, as painful as it can be, dwindles in the light of other forms of ill-treatment and torture, and is likely to have passed unreported in many testimonies. The following is an example of a relatively common situation in which a detainee is cursed in sexual terms and pressured by insinuating harm of a sexual nature to family members:

“The investigation included many vulgar curses about me and my family members. They told me that if I do not confess, they will do obscene things to me and my family.” (age 24, perpetrator: secret service)

Several testimonies included threats of rape. The bulk of these cases involved secret service officers, trying to get a confession. Often the victims were minors or young adults:

“And the police officer… said ‘I will fuck you and you will sing on my dick’ as part of his threats.” (age 16, perpetrator: police)

“The interrogator [name] threatened that he will fuck me and put his hands in my ass if I won’t give him a full confession and if I won’t sign on all accusations that they directed toward me.” (age 28, perpetrator: secret service)

“One of the interrogators said ‘if you don’t confess, I’ll put my foot into your ass.’ […] One of the two interrogators had an electric lamp with cables and told me ‘if you don’t confess, I’ll put these electricity cables in your ass’. […] I confessed out of fear from the electricity and from putting the cables into my behind.” (age 17, perpetrator: secret service)

Sometimes the resemblance to homosexual relations was mentioned, which for many Arab men is a double offence, being raped and being (like) a homosexual.

“And they said ‘you maniac,Footnote** you son of a bitch, terrorist, I’ll fuck you like a homosexual!’” (age 23, perpetrator: secret service)

“The two of them [named] took me to the toilet and then one said that I’m sweet and that I better confess, since otherwise he’ll ask the other to fuck me. […] Then they started hitting me on my face, belly and back.” (age 16, perpetrator: secret service)

Sexual remarks and threats regarding family members almost always concerned female family members (mother, sister, wife, or daughter). In one case, there was reference to humiliation of the father, and in another there was a threat to rape the son of the detainee. This kind of ill-treatment may be experienced as at least as severe as if the detainee were the subject of the remarks or threats.

“And he said […] if you will talk and sign on everything that we’ll tell you, we’ll treat you nice and well, and if not, we’ll fuck your sister.” (age 15, perpetrator: secret service)

In some cases secret service officers brought in family members of the prisoner and threatened them sexually in front of the detainee:

“And he [the interrogator] said that he’ll call two people and that I have three minutes to talk, and if not they will start to rape my wife. My wife started to scream and told [name of the interrogator] that he is an evil man and then he hit her with force in her face.” (age 32, perpetrator: secret service)

A very curious incident is the following, in which a detainee was put under pressure through a threat to his brother to have a sex-change. Though the circumstances are unclear, the effect was mortifying.

“They put me in an investigation room with a glass partition and at the other side I saw my brother, dressed as a woman, immodest, in a mini-skirt. […] They said that they […] had arranged for him a sex-change surgery in Jerusalem.” (age 40, perpetrator: secret service)

Forced nudity

The “Istanbul Protocol” states: “Sexual torture begins with forced nudity, which in many countries is a constant factor in torture situations. An individual is never as vulnerable as when naked and helpless. Nudity enhances the psychological terror of every aspect of torture, as there is always the background of potential abuse, rape or sodomy”.Citation33

Not all requested nudity of detainees is considered ill-treatment; strip searches upon entering prison are a routine part of security procedures in Israel. Thus, virtually all Palestinian detainees are strip searched and, since often they will be moved from one prison to another, this may occur more than once. During such a strip search they are usually required to undress fully, spread their legs and bend. It could be argued that a strip search is inherently humiliating, degrading and harmful, and undermines basic civil and human rights.Citation42 Actually, in the context of a 2015 lawsuit by an Israeli right-wing activist for damages due to a strip search imposed on him, a Jerusalem Magistrate Court judge, in an exceptional ruling, declared routine strip searching of all detainees before their incarceration illegal.Citation43

Generally, strip searches are considered legal according to Israeli law, but the law requires that a) the detainee’s consent be obtained, or in case of objection, the search is authorized in writing by an officer after providing the detainee with an opportunity to be heard, and b) the search is performed in a way that is respectful of the prisoner’s health and privacy, and with minimal inconvenience, pain or hurt.Citation44 Conditions, such as when more individuals are unnecessarily present, or when sexually humiliating remarks are expressed during the search, or when the search is one in a series of sexually tainted incidents, mean that it could be experienced as ill-treatment.Citation3

The following is a common example of a routine strip search that was not according to the protocol.

“They started to do a body search while I was completely nude. I was asked to bend and straighten. During the search I felt that the jailers were provoking me and trying to mock me and especially hurt my honour.” (age 20, perpetrator: jailers)

Apart from strip search upon entering custody, Palestinian detainees are occasionally requested to undress – either partially or fully – during arrest and/or interrogation, mostly by Israeli soldiers or secret service agents, and sometimes by police officers or jailers.

Some victims described being interrogated in the nude, which makes the already frightening situation even more horrific, such as the two examples below, where detainees do not know what to expect next and feel particularly helpless and vulnerable:

“In [name of prison] I sat in a room where they asked me about general issues, after I took off all my clothes except my underpants. I stood with my face to the wall and the soldier who asked me a variety of questions grabbed my neck and pressed my face to the wall.” (age unknown, perpetrator: soldiers)

“Two interrogators lifted me and pushed me to the wall. Then my trousers dropped and I was left in my underwear and the interrogators started to make mocking and very embarrassing remarks that included a sexual, repulsive and humiliating aspect that I remember now in detail. A third interrogator made photographs of me in this humiliating position.” (age 34, perpetrator: secret service)

A few victims reported that they were requested to fully undress in public places. Most likely the soldiers requested the detainees to undress “for reasons of security” and not necessarily to humiliate on purpose; nonetheless, these situations are extremely degrading. Moreover, it is highly dubious that there was no way to protect the privacy of these detainees.

“One of the soldiers threatened me with his gun and ordered me to take off all my clothes in front of all those present. The place was filled with women, men and children, because many people were waiting there to get entry permits to Israel.” (age 25, perpetrator: soldiers)

There are a number of testimonies by detainees who had to remain naked for some period of time; in over half of these cases, without their underwear. The following is an example of how sexually tainted incidents can accumulate to ill-treatment and torture, with forced nudity in public, interrogation in the nude and prolonged nudity without any clear reason:

“They forced me to take off all my clothes, even my underwear, in front of all the men and women who were at the place. After that they gave me a piece of white cloth, which sticks to the body and I remained with that, and they started to interrogate me. […] Four to six hours after the investigation, they moved me to camp [name], at [name] I stayed for only an hour. […]They moved me to prison [name], while I am – still without clothes – hiding my body with the little white cloth that they gave me when they arrested me.” (age 25, perpetrator: soldiers)

Several detainees recounted being photographed in the nude, crossing the border of acceptable conduct. This kind of ill-treatment recalls incidents at Abu Ghraib.Citation45,46

“When I got off the army jeep at [name place] I was nude like a baby is born, and the soldiers started to take pictures together with me.” (age 23, perpetrator: soldiers)

Physical sexual assault

The “Istanbul Protocol” states: “In most cases, there will be a lewd sexual component, and in other cases torture is targeted at the genitals”.Citation33 In our study, reports of sexual assault referred mostly to hits or kicks to the genitals. Some testimonies concerned severe cases of sexual abuse, but mostly in forms that do not leave physical signs. Physical sexual assault by Israeli security officers occurred only exceptionally. However, hits to the testicles were described by several victims. This typically happened while dressed:

“I was taken to a room, I don’t know where, with my eyes covered. After that they jumped on my hands that were stretched to the sides and I got a strong blow in my testicles.” (age 16, perpetrator unknown)

“The interrogator [name] was sitting opposite to me [while feet cuffed] and put his foot on my genitals and pressed and kicked my testicles.” (age 40, perpetrator: secret service)

One testimony concerned simulated rape, which was considered highly demeaning:

“One of the undercover soldiers lay down on me and started to caress my bottom as if he was having sex with me and he started to move his hips and genitals while making sounds. At that point I tried to fight him with all my strength, but my hands were tight behind me and I wasn’t able to. When this undercover soldier got up from me, another came and he too started to caress me and my genitals and buttocks. He tried to take off my trousers, but I kicked him with my feet and they then hit me on all parts of my body with their hands and feet.” (age 26, perpetrator: soldiers)

Of all cases reviewed in this study, the following case from 2007, of an actual rape with a blunt object, is the only one in which the victim’s complaint was not rejected outright by the authorities.Citation47 At the time of writing this article, it is still in court.

“They took off my trousers and underwear and shove a pole into my behind. […] They stopped when someone came in and asked what they were doing. […] A little later, the officer took me to the toilet, locked the door, sat me down and urinated on my face and body.” (age 23, perpetrator: police)

Discussion

The intention of this study was to investigate the occurrence and nature of sexual torture and ill-treatment by Israeli security authorities. Our findings clearly indicate incidents of sexual torture and/or ill-treatment perpetrated by Israeli authorities between 2004 and 2012. The allegations of sexual torture and ill-treatment appertain to a variety of perpetrators including secret service, army, police and jail officers, but not to health professionals.

The incidents can be divided into three broad categories: verbal sexual harassment, forced nudity, and physical sexual assault. Verbal sexual harassment, sometimes with a homosexual connotation, and forced nudity, apart from routine strip searches, are described most frequently in this study, while reports of physical sexual assault were incidental. It may be argued that the severity of most of the incidents is not as cruel as reported in studies from other conflict situations, such as rape, genital mutilation and castration, and that it is not as extensive as in other countries.Citation28–32,34,38,39,48–51 However, a recent review concluded that sexual humiliation is considered a form of psychological torture, with many victims painfully reliving memories of sexual insults and threats. Forced nudity, which strips a person of his/her identity and puts him/her in a shameful position and at risk of assault, was suggested as comparable to sexual assault.Citation65

The literature suggests that sexual torture leaves more profound psychological effects than physical effects and that being the victim of sexual abuse is likely to have detrimental effects on one’s psychological well-being; also if the victim is a man.Citation40,52 For example, a study on victims of torture from 45 countries, found that less than 20% of the male detainees sexually assaulted by their guards or interrogators had physical signs of the assault, while over 50% had symptoms classified as post-traumatic stress disorder.Citation53 Fear- and helplessness-inducing effects of captivity and ill-treatment, sexual torture among them, appear to be the major determinants of perceived severity of torture and psychological damage in detainees.Citation14

There are profound changes taking place in the Arab world regarding sexual and gender relations, with conflicting expectations, uncertainty, ambivalence and collective anxiety. At the same time, the importance of sexuality as defining self and morality retains its central role.Citation54 Sexual torture and ill-treatment, including forced nudity and curses with sexual contents, may have particularly deep and sometimes long-lasting humiliating effects among Arab men. This is grounded in the notion of honour, which is basic in social life in much of the Muslim world.Citation55,56 Considering the link between honour and masculinity, sexual violence toward men in armed conflicts is often based on dynamics of emasculation, feminization and/or homosexualization.Citation31,57 Sexual violence is also related to the notion of modesty. The practice of modesty is central in daily life in Islamic cultures in the Middle EastCitation58 and immodesty of either the person himself or a family member is dishonouring. Many Palestinian men would subscribe to the understanding that a Muslim Arab man’s honour is derived for an essential part from retaining intact the unblemished sexuality of the women of the family.Citation55,56 The understanding that in honour cultures insult to a family member could create the same level of intense anger and shame as if the target of the insult had been the person himself,Citation59 gives rise to forms of torture by proxy or vicarious torture.Citation60 In general, sexual violence toward men in war has consequences not just for the person himself, but also for his family, and possibly for the community as a whole.Citation49 Put in a broader context, sexual violence toward Arab men by non-Arabs can be viewed as a way to superimpose one culture over another and break down social codes.Citation61 In fact, the United States was accused of deliberately practicing faith-based (anti-Islamic) torture.Citation60 These factors need to be taken into account when evaluating allegations of sexual torture and/or ill-treatment. The quotes above illustrate how the honour of the detainees is damaged and how victims are disempowered, including transgressions of modesty, emasculation and the threat of violence against female family members.

While there is a rise in scientific publications in the field, the discussion in society of sexual violence toward men remains a delicate issue and is hindered by social stigma.Citation34,38,49,50,41 In the Arab world, there is a relative silence in discourse around sexuality in general.Citation62 Furthermore, there are taboos surrounding male-to-male sexuality in most of the Arab world and homosexuality tends to remain concealed.Citation63 It was suggested that public display or discourse of sexuality may be more troubling for many Muslims than the practice of varying forms of sexuality;Citation64 the more reason to keep divergent sexuality in silence. In fact, both torture and sexual assault are issues that are taboo in many societies and, especially for men, too shameful to speak about openly.Citation53 This makes sexual torture of men extra painful and difficult to resolve, and calls for efforts to bring it into the open. At the same time, it needs to be contemplated that the publication of data on sexual torture during an ongoing conflict, or even in its aftermath, could be experienced as insulting for the relevant population or misused by authorities, which obviously is not its intent. In this case, the information provided is believed not to be new to Israeli security forces and therefore will not enhance practices of torture. Furthermore, the benefit of exposure is reckoned to weigh heavier than its potential harm to the honour of the Palestinian reader.

Concerns remain about the occurrence of sexual torture and ill-treatment of Palestinian detainees and the reluctance of the relevant Israeli authorities to investigate allegations and compensate victims. As stated, the testimonies in this study expose neither the extent of sexual torture and/or ill-treatment, nor the prevalence of this phenomenon in society. Although we indicate 4% as the prevalence of sexual torture and ill-treatment in the testimonies from the PCATI archive reviewed in this paper, it is expected that the actual number of sexual torture and ill-treatment is much higher. As observed in other places,Citation39 it is assumed that most of the incidents of torture, and especially sexual torture, remain unreported. It is believed that not all victims approached PCATI or that many were lost to follow up after the initial phone contact. Some of the reasons for not submitting a testimony could be lack of awareness of the organization, reluctance of turning to an Israeli organization, lack of incentive (especially since reporting is not rewarded), taboo and fear of stigmatization, fear of repercussion either by Israeli authorities or by Palestinian society toward the victims or their family members, the emotional effort required, as well as travel restraints, costs and time.

In addition, there are two stages in the process of collecting torture-related data at which information of a sexual nature may be disregarded or not noted: the submission of the testimony (the interview) and the process of codification. The interview, if in prison, is not private. Prisoners and their lawyers are separated by a glass wall, while others are in close proximity, which undoubtedly is an uncomfortable position to disclose issues with a sexual aspect. Thus, victims may have concealed sexual facets of ill-treatment because of lack of privacy or out of embarrassment. In addition, they may have overlooked the significance of incidents, especially if assumed to be relatively common, like humiliating remarks during strip searches or sexually tainted cursing. It also needs to be noted that, generally, victims meet PCATI representatives only once, while it is known that information about sexual assault (also if merely verbally) is often shared only at a second or third encounter with a torture investigator.Citation33 Furthermore, fieldworkers and lawyers are trained to ask open questions and clarifications and their protocol does not refer to specific contents and they will not pose leading questions. As a consequence, they usually do not enquire specifically about incidents of sexual nature. In fact, since awareness and sensitivity regarding sexual torture is rising only in recent years, they may not in all cases have recorded sexual aspects, even when expressed. For example, the victim may have reported being verbally humiliated, mentioning the sexual nature of the humiliation, but the lawyer/fieldworker only recorded humiliation without specifying the sexual nature.

During the process of codification, which takes place at a later stage by a different person, incidents of a sexual nature could have been ignored not just because codification at the time (2005-2012) was only partially implemented, but also because of lack of sensitivity to the sexually humiliating nature of certain situations. In addition, issues of translation (from Arabic to Hebrew), gender-bias (e.g., the notion that men are less vulnerable to verbal insults of a sexual nature) and the existence of “more serious” violations in certain cases could have resulted in sexual torture and/or ill-treatment of men not being recorded.Citation66 This reinforces the argument that it is not to be assumed that the number of cases documented is an indicator of prevalence of sexual torture against Palestinian men in Israeli detention.

Another limitation is the significant lapse of time between the incident and its report, which in some cases can be several years. This time lag is likely to affect the testimony due to recall bias as a result of various “normal” memory processes, and distort the facts.Citation67 One could also argue that testimonies were fabricated as the base for a legal claim, to take revenge on the Israeli authorities, or to receive compensation for personal damage. However, there are no reasons to believe that the testimonies of the incidents were fabricated; the reality is that until now, few testimonies have been brought to court, no Israeli official has been convicted on these grounds, and no victim has obtained any compensation, as would be expected according to the UN Convention Against Torture.Citation12 For socio-cultural reasons, it is unlikely that Palestinian men invent or elaborate on stories in which they were sexually victimized; recounting these kinds of incidents is expected to be most embarrassing for them, if not humiliating, whereas no extrinsic rewards are to be expected.

It needs to be noted that throughout this study we encountered some methodological difficulties, limiting the possibility of generalization and statistical analysis. More sophisticated and robust methodology of documentation could allow for systematic and comparable data in the future.

Unfortunately, we have no data regarding the impact of incidents after the testimonies were recorded, since PCATI doesn’t follow up with the victims. We can speculate that Palestinian boys and men, if released from prison, will go back to their families and try to rebuild a living. Some will go in and out of prison; few will be expelled from their living environment or the country. It is to be expected that most will keep to themselves the terrible experiences they went through and will try to conceal symptoms of torture and/or ill-treatment. Treatment is rare, but those who have the courage to talk and the means to reach Ramallah (Palestinian Authority) can turn to the Treatment and Rehabilitation Centre for victims, which is the main institute providing assistance.Citation27

Conclusion & RecommendationsFootnote††

This study, which is the first of its kind to report on sexual torture and ill-treatment experienced by Palestinian men and boys, provides reliable and valid insight into the occurrence and the types of sexual torture and/or ill-treatment experienced by Palestinian men at the hands of Israeli interrogation and/or law enforcement authorities. The study demonstrates that sexual torture and ill-treatment continued during 2004-2012, by different perpetrators and in a variety of settings within the system. Our findings indicate that, although limited in extent, Israeli authorities are systemically involved with torture and ill-treatment of a sexual nature, thus breaching the basic sexual rights of Palestinian detainees. The fact that a previous reportCitation34 suggested the contrary merely shows that these practices can remain under the radar for many years, implying that sexual torture and ill-treatment may be more common than believed to be, also in other armed conflicts where there is no public awareness.

As seen in other countries,Citation39 these incidents often do not stand alone; they are all embedded in a series of other forms of torture and ill-treatment. The reality that allegations of torture are hardly ever investigated by the relevant authorities and that no victims are rehabilitated and/or compensated makes it clear that there is a lack of recognition by Israeli authorities of the existence of (sexual) torture and ill-treatment, despite subscription to international conventions and national laws relating to sexual violence and abuse. Based on these findings, some recommended actions are warranted.

Taking responsibility

There is an urgent need for the relevant authorities to comply with international legal and human rights standards and take responsibility for a) the investigation of incidents of (sexual) torture and ill-treatment on all levels, b) provision of treatment for the possibly pernicious impact on the psychological and sexual health of the victims, and c) compensation for all victims, regardless of their current sequelae.

Raising awareness

Dissemination of information to the general public, and especially among potential perpetrators, could possibly change the general attitude toward torture and ill-treatment and press authorities and perpetrators to take responsibility for their actions.

Training of legal and health professionals

Training is required so that health and legal professionals will be more sensitive to the detrimental effects of torture and ill-treatment in general, and their sexual aspects in particular. This may have a double effect: professionals in various settings who come in contact with detainees will be more ready to expose and interfere in abusive interrogations, and professionals handling allegations of torture in courts and complaint systems will be better prepared.

Documentation

There is need for more detailed and systematic documentation and codification of data, allowing for statistical analysis of incidents of (sexual) torture and ill-treatment, assessment of health-related effects, follow up and comparison with data from other countries.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr. Rachel Stroumsa, Att. Shahrazad Odeh, Efrat Shir and Immanuel Ben Porat for their extensive help in preparing this article. No funding to declare. No conflict of interest.

Notes

* For an outline of the difficulties in bringing sexual and other forms of torture to court in Israel, see elsewhere.Citation68

† The archive makes use of a very limited number of keywords/categories (e.g. terms such as sexual humiliation, genitalia and verbal torture are missing). Moreover, texts cannot be searched by computer, because they are handwritten.

‡ It would be of significant interest to obtain information on the health impact of (sexual) torture or ill-treatment, but as a legal aid and social change organization PCATI does not record this in a systematic way, aiming rather to highlight a pervasive problem (Stroumsa R, Project Manager at PCATI, Personal communication, 30 August 2015).

§ Soldiers and border police officers belong to different governmental authorities, but are grouped here together, because many Palestinians do not differentiate between the two, as a result of their similar uniforms.

** In Arabic, the word "maniac" has the connotation of a "passive" homosexual.

†† These are the opinion of the author, and not necessarily the position of PCATI.

References

- Amnesty International. Amnesty International Report 2014/2015: The State of the World’s Human Rights [Internet]. [cited 2015 Feb 25]. Available fromhttps://www.amnesty.org/en/. 2015

- Public Committee Against Torture in Israel. 1999 to the present [Internet]. [cited 2015 May 4]. Available fromhttp://www.stoptorture.org.il/en/skira1999-present

- Y. Lein. Absolute prohibition: The torture and ill-treatment of Palestinian detainees. 2007; B’tselem & Hamoked: Jerusalem, Israel.

- G.-W. Falah. Geography in ominous intersection with interrogation and torture: Reflections on detention in Israel. Third World Quarterly. Routledge. 29(4): 2008; 749–766.

- F.A. Akar, R. Arbel, Z. Benninga, M.A. Dia. The Istanbul protocol (manual on the effective investigation and documentation of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment): implementation and education in Israel. Israeli Medical Association Journal. 16(3): 2014; 137–141.

- G. Menicucci. Sexual Torture Rendering, Practices, Manuals. 2005; ISIM: Leiden, 18–19.

- S. Devi. Israeli doctors accused of collusion in torture. Lancet. 381: 2013; 794.

- J.S. Yudkin. The Israeli Medical Association and doctors’ complicity in torture. British Medical Journal. 339: 2009; b4078.

- Y. Ginbar. “Celebrating” a decade of legalised torture in Israel. Essex Human Rights Review. 6(1): 2009; 169–187.

- Penal Law - Article Five: Sex Offenses. Israel State Law. 1977

- Prevention of Sexual Harassment Law. Israel State Law. 1998

- United Nations. UN Convention against Torture, A/RES/39/46 [Internet]. Available fromhttp://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/39/a39r046.htm. 1986

- B’Tselem. Torture and ill-treatment from the perspective of international law [Internet]. [cited 2015 Aug 27]. Available fromhttp://www.btselem.org/torture/international_law. 2011

- M. Başoğlu. A multivariate contextual analysis of torture and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatments: implications for an evidence-based definition of torture. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 79(2): Apr. 2009; 135–145.

- M. Başoğlu, M. Livanou, C. Crnobarić. Torture vs other cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment: Is the distinction real or apparent? Archives of General Psychiatry. American Medical Association. 64(3): Mar. 1 2007; 277–285.

- C. Levinson. Israel to compensate Palestinian for disability caused by interrogation [Internet]. Haaretz. 2010 Dec 21. (Available from: Haaretz.com).

- H. Greenberg. Palestinians compensated over torture claims [Internet]. Ynetnews. 2006 Jan 2;Available fromynetnews.com

- N. Sveaass. Gross human rights violations and reparation under international law: approaching rehabilitation as a form of reparation. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 4: Jan. 2013. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.17191.

- J.M. Jaranson, M.K. Popkin. Caring for Victims of Torture. 1998; American Psychiatric Press: Washington, D.C.. (308 pp.).

- N. Hofstadter, E. Koru. By the rules: A comparative study in the legal framework of torture in Turkey and Israel [Internet]. 2015; PCATI & Human Rights Foundation of Turkey. (Sept. 2015 from: http://en.tihv.org.tr/).

- J. Modvig. Violence, sexual abuse and torture in prisons. S. Enggist, L. Moeller, G. Galea. Prisons and Health. 2014; World Health Organization. 19–24.

- S. Enggist, L. Moeller, G. Galea. Prisons and Health. 2014

- Human Rights Foundation of Turkey. Psychological Evidence of Torture: A Practical Guide to the Istanbul Protocol. Copenhagen: International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims [Internet]. 2004. (Available from: http://www.hrea.org).

- I.A. Kira, M.H. Fawzi, M.M. Fawzi. The dynamics of cumulative trauma and trauma types in adults patients with psychiatric disorders: Two cross-cultural studies. Traumatology. 19(3): 2013; 179–195.

- S. Yuksel. Impact of sexual torture. Human Rights Foundation of Turkey. Treatment and Rehabilitation Centers Report 1994. 1995; HRFT: Ankara, Turkey, 71–82.

- K.E. Miller, A. Rasmussen. War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Social Science and Medicine. 70(1): Jan. 2010; 7–16.

- M. Sehwail. Responding to continuing traumatic events. International Journal of Narrative Therapy and Community Work. 3/4: 2005; Dulwich Centre Publications Pty Ltd. 54–56.

- H.M. Zawati. Impunity or immunity: Wartime male rape and sexual torture as a crime against humanity. Torture. 17(1): Dec. 22, 2007; 27–47.

- E.S. Carlson. The hidden prevalence of male sexual assault during war: Observations on blunt trauma to the male genitals. British Journal of Criminology. 46(1): Apr. 27, 2005; 16–25.

- ì. ìzkalipçi, é. łahin, T. Baykal. Atlas of torture: Use of medical and diagnostic examination results in medical assessment of torture. 2010; Human Rights Foundation of Turkey: Ankara, Turkey.

- S. Sivakumaran. Sexual violence against men in armed conflict. European Journal of International Law. 18(2): Apr. 1,2007; 253–276.

- N. Warfa, K. Izycky, E. Jones. Contemporary methods of torture and sexual violence medical record analysis [Internet]. [cited 2015 Feb 25]World Cultural Psychiatry Research Review. 2011; 112–118. (Available from: http://www.wcprr.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/2011.02.112-118.pdf).

- UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Manual on the effective investigation and documentation of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (“Istanbul Protocol”). HR/P/PT/8/Rev.1 [Internet]. 2004http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/4638aca62.html. 2004

- E.J. Wood. Variation in sexual violence during war. Politics & Society. 34(3): Sep. 1, 2006; 307–342.

- Y.J. Bob. Supreme Court: Lebanese terrorist can’t sue Israel for interrogators' alleged rape, torture [Internet]. Haaretz. Jan. 15, 2015. (Available from: Haaretz.com).

- World Association of Sexual Health. Declaration of Sexual Rights. 2014

- E. Kismödi, J. Cottingham, S. Gruskin. Advancing sexual health through human rights: the role of the law. Global Public Health. 10(2): Jan. 2015; 252–267.

- S. Solangon, P. Patel. Sexual violence against men in countries affected by armed conflict. Journal of Conflict, Security and Development. 12(4): Sep. 28 2012; 417–442.

- United Nations OCHA. Use of Sexual Violence in Armed Conflict: Identifying gaps in Research to Inform More Effective Interventions UN OCHA Research Meeting - 26 June 2008. Discussion Paper 2 The Nature, Scope and Motivation for Sexual Violence Against Men and Boys in Conflict. 2008

- M.A. Onyango, K. Hampanda. Social constructions of masculinity and male survivors of wartime sexual violence: an analytical review. Taylor & Francis Group, International Journal of Sexual Health. 23(4): Oct. 29, 2011; 237–247.

- T. Alcorn. Responding to sexual violence in armed conflict. Lancet. Elsevier. 383(9934): Jun. 2014; 2034–2037.

- G. Annas. Strip searches in the Supreme Court – Prisons and Public Health. New England Journal of Medicine. 367(Oct. 25): 2012; 1653–1657.

- Y.J. Bob. Court declares IPS automatic strip search policy illegal in right-wing activist case. Jerusalem Post [Internet]. Feb. 26, 2015. (Available from: jpost.com).

- Criminal Procedure (Enforcement Powers - body search and seizure of identifying information), Section 1. Israel State Law. 1996

- C.B. Laustsen. The camera as a weapon: On Abu Ghraib and related matters. Journal of Cultural Research. Routledge. 12(2): Apr. 10, 2008; 123–142.

- M.A. Tétreault. The sexual politics of Abu Ghraib: Hegemony, spectacle, and the global war on terror. NWSA J. 18: 2006; The Johns Hopkins University Press. 33–50.

- O. Rosenberg. Activists call for police abuse case to be reopened [Internet]. Haaretz. Jan. 19, 2012. (Available from: Haaretz.com).

- P. Oosterhoff, P. Zwanikken, E. Ketting. Sexual torture of men in Croatia and other conflict situations: An open secret. Reproductive Health Matters. Elsevier. 12(23): May 5, 2004; 68–77.

- M. Christian, O. Safari, P. Ramazani. Sexual and gender based violence against men in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Effects on survivors, their families and the community. Medicine, Conflict and Survival. Routledge. 27(4): Jan. 30, 2012; 227–246.

- S. Mirzaei, T. Wenzel. Anal torture with unknown objects and electrical stimuli. Journal of Trauma & Treatment. 2(162): 2013; 1222–2167.

- F. Ní Aoláin. Sexual torture, rape, and gender-based violence in the Senate Torture Report [Internet]. Just Security. 2015. ([cited 2015 Mar 2]. Available from: http://justsecurity.org/19731/sexual-torture-rape-gender-based-violence-senate-committee-report/).

- E. Romano, R.V. De Luca. Male sexual abuse: A review of effects, abuse characteristics, and links with later psychological functioning. Aggression and Violent Behavior. Elsevier. 6(1): 2001; 55–78.

- M. Peel. Male sexual abuse in detention. M. Peel, V. Iacopino. The Medical Documentation of Torture. 2002; Greenwich Medical Media: London, 179–190.

- S. Khalaf. Living with Dissonant Sexual Codes. S. Khalaf, J. Gagnon. Sexuality in the Arab world. 2014; Saqi.

- L. Abu-Odeh. Crimes of honor and the construction of gender in Arab societies. Comparative Law Review. 2(1): 2011; 1–47.

- D. Pely. When honor trumps basic needs: The role of honor in deadly disputes within Israel’s Arab community. Negotiation Journal. 27(2): Apr. 17, 2011; 205–225.

- P. Owens. Torture, Sex and Military Orientalism. Third World Quarterly. Taylor & Francis. 31(7): 2010; 1041–1056.

- C.E. Rothenberg, C.E. Rothenberg. Modesty and Sexual Restraint. C.R. Ember, M. Ember. Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender. 2004; Springer US: Boston, MA, 187–191.

- P.M. Rodriguez Mosquera, L.X. Tan, F. Saleem. Shared burdens, personal costs on the emotional and social consequences of family honor. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 45(3): Nov. 19, 2013; 400–416.

- A. Khan. Faith-based torture. 12: Nov. 13, 2010; Global, Dialogue.

- J. Butler. Sexual politics, torture, and secular time. British Journal of Sociology. 59(1): Mar. 2008; 1–23.

- A. Dialmy, A.J. Uhlmann. Sexuality in contemporary Arab society. Social Analysis. 49: 2005; 16–33.

- D.J.N. Weishut. The Middle East. Tin Louis-Georges, M. Redburn. The dictionary of homophobia: A global history of gay and lesbian experience. 2008; Arsenal Pulp Press: Vancouver, BC.

- K.P. Ewing. Naming our sexualities: Secular constraints, Muslim freedoms. Focaal. Berghahn Journals. 2011(59): Mar. 30, 2011; 89–98.

- D. Cunniffe. The worst scars are in the mind: Deconstructing psychological torture. Vienna Journal on International Constitutional Law. 7(1): 2013; 1–61.

- M.L. Leiby. Wartime sexual violence in Guatemala and Peru. International Studies Quarterly. 53(2): Jun. 2009; 445–468.

- D.L. Schacter. The seven sins of memory: Insights from psychology and cognitive neuroscience. Americal Psychologist. 54(3): 1999; 182–203.

- Odeh S. [Sexual Torture against Men: Present and Desirable Legal Status] Hebrew. (Unpublished). Jerusalem; 2014.