Abstract

The prevalence of violence against women worldwide raises the question of the desirability and feasibility of integrating interpersonal violence (IPV) services within abortion care. By examining present services and context in an Inner London borough in the UK, this situation analysis explored the hypothesis that an established, integrated, health-based service (comprising raised awareness, staff training in routine IPV enquiry and referral to a community-based in-reach IPV service) would be transferable into abortion services. Four sources of qualitative data investigated views on integrating services: key stakeholder in-depth interviews including with providers of abortion and IPV services and commissioners and IPV survivors with past abortion service use (3 user, 15 provider); qualitative analysis of the open-ended part of a survey of current abortion service users with and without experience of IPV; feedback from an interactive workshop and data from field observations. While there was consensus among all informants that women experiencing IPV and seeking abortion have unidentified, unaddressed needs, how any intervention might be organised to address these needs was contested; thus questions remain about whether, when and how to raise the topic of IPV and what to offer. Two major anxieties surfaced: a practical concern in terms of interrupting a streamlined abortion service that suits the majority of staff and patients, and a conceptual concern about risk of stigmatising abortion seekers as ‘victims in crisis’. Thus, our findings indicate: when integrating IPV interventions into abortion services, local context, the integrity of separate pathways, and women’s safety and agency must be considered, especially when abortion rights are under attack. Novel approaches are required and should be researched.

Résumé

La violence contre les femmes est omniprésente dans le monde et l’avortement sécurisé soutient la santé et les droits sexuels et génésiques, ce qui soulève la question de la désirabilité et la faisabilité de l’intégration de services traitant la violence interpersonnelle au sein des services d’avortement. En examinant le contexte et les services actuels dans un quartier de Londres au Royaume-Uni, cette analyse de situation a étudié l’hypothèse selon laquelle un service de santé intégré (comprenant des activités de sensibilisation, la formation du personnel à l’enquête systématique sur la violence interpersonnelle et l’aiguillage vers un service communautaire s’occupant de violence interpersonnelle) pourrait être transféré dans des services d’avortement. Quatre sources de données qualitatives ont été utilisées pour obtenir des avis sur l’intégration des services: des entretiens approfondis avec des acteurs clés, notamment des prestataires d’avortement et de services relatifs à la violence interpersonnelle et des victimes de violence interpersonnelle ayant eu recours à l’avortement (3 utilisatrices, 15 prestataires); une analyse qualitative de la partie à questions ouvertes d’une enquête auprès des utilisatrices des services actuels d’avortement avec ou sans expérience de violence interpersonnelle; des commentaires d’un atelier interactif et des données tirées d’observations sur le terrain. Si tous les informants étaient d’accord pour affirmer que les femmes connaissant la violence interpersonnelle et voulant avorter avaient des besoins non identifiés et non satisfaits, la manière dont toute intervention peut être organisée pour répondre à ces besoins était contestée; des interrogations demeurent donc sur l’opportunité, le moment et la manière de soulever la question de la violence interpersonnelle et sur ce qu’il faut proposer. Deux inquiétudes majeures sont apparues: une préoccupation pratique face à l’interruption d’un service d’avortement rationalisé qui convient à la majorité du personnel et des patientes, et une préoccupation conceptuelle sur le risque de stigmatisation des femmes souhaitant avorter comme « victimes en crise ». Par conséquent, nous en concluons que lorsqu’on intègre des interventions relatives à la violence interpersonnelle dans des services d’avortement, il faut tenir compte du contexte local, de l’intégrité des voies séparées ainsi que de la sécurité et de l’activité des femmes, spécialement quand le droit à l’avortement est menacé. De nouvelles approches sont requises et devraient faire l’objet de recherches.

Resumen

La violencia contra las mujeres es prevalente en todo el mundo y los servicios de aborto seguro apoyan la salud y los derechos sexuales y reproductivos, lo cual plantea la interrogante acerca de la conveniencia y viabilidad de integrar los servicios de violencia interpersonal (VIP) en los servicios de aborto. Al examinar el contexto y los servicios actuales en un distrito en el centro de Londres, en el Reino Unido, el análisis situacional exploró la hipótesis de que un servicio de salud establecido e integrado (que comprende concienciación y capacitación del personal en la investigación y referencia rutinaria de VIP a un servicio comunitario de VIP al alcance) sería transferible a los servicios de aborto. Cuatro fuentes de datos cualitativos investigaron los puntos de vista relacionados con la integración de los servicios: entrevistas a profundidad con partes interesadas clave, que incluyeron a prestadores de servicios de aborto y servicios de VIP, así como comisionados y sobrevivientes de VIP que habían usado los servicios de aborto (3 usuarias, 15 prestadores de servicios); análisis cualitativo de la parte abierta de una encuesta sobre usuarias actuales de servicios de aborto con y sin experiencia de VIP; retroalimentación de un taller interactivo y datos de observaciones de campo. Aunque hubo consenso entre todos los informantes de que las mujeres que sufren VIP y buscan servicios de aborto tienen necesidades no identificadas y no atendidas, se disputó la manera en que la intervención podría ser organizada para atender estas necesidades. Por lo tanto, aún hay preguntas en cuanto a si se debe mencionar el tema de VIP y, en caso afirmativo, cuándo y cómo plantearlo y qué ofrecer. Surgieron dos ansiedades principales: una preocupación práctica con relación a interrumpir un servicio de aborto organizado que es adecuado para la mayoría del personal y las pacientes, y una preocupación conceptual sobre el riesgo de estigmatizar a las mujeres que buscan servicios de aborto como ‘víctimas en crisis’. Por lo tanto, nuestros hallazgos indican: al integrar intervenciones de VIP en los servicios de aborto, se debe considerar el contexto local, la integridad de vías individuales y la seguridad y agencia de las mujeres, especialmente cuando los derechos de aborto están bajo ataque. Nuevos enfoques son necesari

Introduction

Violence and abuse against women and girls is prevalent worldwide with health, criminal justice and financial implications.Citation1,2,3,4 Interpersonal violence (IPV) is increasingly recognised as an important cause of avoidable mortality and morbidity.Citation5,6,7,8 In international debates, some authorities recommend screening all women of childbearing age for detecting IPV, as reproductive and sexual health services provide an opportune setting for multi-agency interventions.Citation9,10,11 Others do not, due to lack of evidence of improved outcomes for women,Citation2,12,13 though they recommend training health professionals to be alert to the signs,Citation2 provision of safe environments for disclosure, and the commissioning of pathways across health and social care.Citation12 Thus, health-sector based IPV interventions remain in their infancy.Citation14,15

A recent systematic review identified high prevalence of IPV in women seeking abortion and an association with multiple abortions.Citation16 Meta-analysis showed worldwide rates of IPV in the preceding year in women undergoing abortion ranging from 2.5% to 30%. Lifetime IPV prevalence was shown to be 24.9% (95% CI, 19.9%-30.6%).Citation16 There is also a high rate of abortion following rape.Citation17 Despite an early recognition that a commonly cited reason for seeking abortion is ‘relationship problems’,Citation18 there are very few studies about the links between abortion and IPV. There are no published articles on integrated IPV interventions within abortion services. Although context-specific and not generalisable, individual studies about IPV disclosure or intervention in relation to abortion services described in detail in the above mentioned systematic review indicate that: IPV questionnaires may be acceptable in abortion facilities;Citation19 non-responding women may differ from responders in that they have undergone more abortions;Citation20 only half the women during a period of universal screening were asked about IPV;Citation21 some women report IPV-defining events although not identifying themselves as experiencing IPV;Citation22 many women wish to talk about IPV with regard to further management or intervention,Citation23 with some citing their doctor as the main source of information;Citation24 and women in violent relationships appear as likely to attend for follow-upCitation23 and more likely to know about community resources.Citation24 Previous situation analyses of abortion generally relate to the provision of safe abortion and quality of care rather than the intersection with IPV.Citation25,26,27

Thus, it remains moot whether IPV is accepted as rightful business for the abortion sector, and what training and support healthcare professionals need. In particular, in the UK, there is no policy for screening for IPV. Though health services, social care and the organisations they work with should respond effectively, there is no agreed evidence of benefit of screening.Citation12

The aim of this study was to explore the desirability and feasibility of offering IPV services within abortion care in a local setting (two boroughs) in London. A nearby, established, maternity-based service had an integrated IPV service comprising raised awareness, staff training in routine IPV enquiry and referral to a community-based in-reach IPV service. There are posters and leaflets displayed around the service. There is mandatory confidential time with pregnant women at the first visit and a routine question can be asked verbally and ‘ticked’ as having been asked in a coded way in the hand-held notes. Opportunistic case-based questioning also occurs and generates about half the disclosures. Referral is then made to an onsite IPV service. The IPV service has been evaluatedCitation14 and regularly audited. The hypothesis for this study was that the model of an integrated maternity-based IPV service would be transferable to an abortion setting.

Study setting

The study was conducted in 2012 in a deprived, multi-ethnic, inner city area in London, UK where there is a National Health Service (NHS) funded by taxpayers. Abortion has been legal in England, Wales and Scotland since the 1967 Abortion Act, amended by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990. The Act requires that two doctors sign in good faith that one of five legalised provisions is fulfilled and ensure that abortion takes place in a licensed premise, unless there is an emergency. Nationally, abortion is provided free of charge if women are resident in the UK and entitled to NHS care. Different NHS trust contractors agree to different add-on services alongside the abortion itself (e.g., pre-abortion counselling or post-abortion contraception).

In the two study boroughs, the NHS sub-contracts all but medically complicated abortions (e.g., maternal cardiac disease/ late diagnosis of foetal abnormality) to two non-governmental, non-profit providers (i.e., three abortion services in total). Both of the providers are contracted by the NHS for provision of abortion and contraception services and receive women from all over the UK and Ireland.

IPV services in the UK consist of policy, criminal justice, non-governmental and local government initiatives. There is no formal screening for IPV in the health service as there is no evidence of benefit, though it has been recognised that a health service response is required.Citation12 There is limited training of healthcare providers in addressing IPV, and no specialist IPV services were provided in any abortion clinic. There is high-level commitment to talking about violence against women and girls at nationalCitation28,29 and London-wideCitation30 levels with plenty of discourse about the need for joined-up government and multi-agency collaborative services. The local government in the study area has a commitment to provide services for women who are subject to violence,Citation31,32 and IPV initiatives exist in local health services. IPV advisors are located in a community-based ‘one-stop shop’ and primary healthcare, as well as in one of the two teaching hospitals (in maternity,Citation14 department of genitourinary medicine, as well as in the accident and emergency room). A Sexual Assault Referral Centre, co-commissioned by police and health services, is located in the other hospital. In our study of women accessing abortions in the local area in 2012, the current prevalence of IPV was 4%, past year IPV was 11%, and lifetime experience was 16%.Citation33

Methods

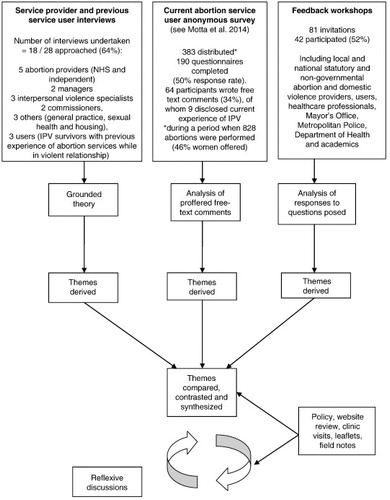

This paper analyses the qualitative results from a larger research project (Abortion in Context) which contained three main studies: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the associations of IPV and abortion;Citation16 an anonymous survey to assess IPV prevalence in a local abortion clinic;Citation33 and a situation analysis.

There were four sources of qualitative data:

| 1. | In-depth interviews. 18 stakeholders (3 user, 15 provider) were interviewed to assess whether violence and abuse were considered issues for women accessing abortion services, what services were currently provided and what future IPV services in abortion clinics should look like. The in-depth interviews took place between 9 May and 21 September 2012. The three service users were women who had experienced abortion(s) whilst in a violent relationship and had received IPV services since. They were recruited through a local IPV survivor-initiated, peer-support group. Women were not approached directly by the researchers for ethical reasons, to ensure they were volunteering within an already supportive environment. We addressed a meeting of the single IPV-survivors group (facilitated by the IPV specialist) to explain the study. An email was sent around the survivor group (now defunct and number unknown) inviting women who had accessed abortion services while in a violent relationship to participate. IPV advocates also approached individuals they thought likely to be able to assist. The IPV advocates acted as liaison and passed contact details onto LPK. It was difficult to recruit users and only three women in the IPV survivor group volunteered for an in-depth interview. It is not possible to know how many others had accessed abortion services but did not come forward. The three interviewees had multiple experiences of abortion services and complex needs and may not be typical. The criterion for service providers was involvement in relevant contributory agencies. An initial list was based on SB’s local knowledge. Service provider interviewees were asked to suggest other people via snowball sampling in order to ensure a mixture of perspectives (sample sizes and roles, ). Of service providers who were approached for in-depth interviews, the overwhelming majority agreed. Some declined interviews if they were not in a relevant role, or knew a better informant. There were no outright refusals, and only one local abortion provider who initially agreed to be interviewed did not respond after three contacts. All interviewees received a personalised invitation (see Box 1 below.) and, following consent, interviews were taped, transcribed, anonymously numbered, and kept in a locked cabinet. Semi-structured interview guides with 16 open-ended questions and prompts were developed to ask both service providers and service users about abortion-seeking women’s needs of IPV services, what services were in place and available locally on the abortion pathway, and to comment about design of any future services (see Box 2 below). (See Stakeholder interview guide (MOSAiC-VR) – for service providers and Stakeholder interview guide (MOSAiC-VR) – for survivors.) The results of the interview have not previously been published. | ||||

| 2. | Qualitative analysis of an open-ended part of an anonymous prevalence survey. In order to hear the voices of women currently undergoing abortion services, free-text comments made by service users participating in an anonymous cross-sectional prevalence surveyCitation33 were examined (complete anonymity had been chosen to encourage participation). Only one local abortion clinic allowed the anonymous prevalence study of users, with clinic staff handing out the questionnaires. They were asked “Do you think having a support service for victims of abuse, domestic or sexual violence in abortion clinics could be a useful thing? Yes/No. Please detail your thoughts about this.” and given space for explanation. This was to ensure that current abortion service users were included in terms of designing services, as women with or without IPV might be impacted. Sixty-four women (of 190 participants) answered the open-ended question, of whom nine disclosed current IPV (all unknown to the clinic staff). A third of all participants removed the stapled card with information about national and local IPV services.Citation33 The results of this survey have been published, however, the qualitative data are being used for secondary analysis in this study. | ||||

| 3. | Information from feedback workshops. All user and service provider interviewees were invited to a half day interactive feedback workshop on September 28th 2012, along with members of key local and national agencies and additional external experts identified during the research project and via informants (). The purpose was to present the preliminary analyses of all Abortion in Context studies for validation and comment, and to collect additional feedback from a wider group in order to reflect on the implications for UK services and research. Small round-table self-directed focus groups were formed to discuss two open-ended questions about design and evaluation of a multi-agency IPV intervention in abortion services. Feedback sheets were typed up and coded (individuals not identifiable). All feedback workshop participants actively engaged in the discussions and in small groups (). | ||||

| 4. | Participant observation. The researcher (LPK) kept detailed field notes, noted relevant media stories, reviewed local and national websites of statutory and non-governmental organisations dealing with abortion or IPV, visited abortion and IPV facilities during stakeholder interviews, requested policies relevant to abortion and IPV and picked up available leaflets. This was done in order to establish context, triangulate findings from the interviews, explore inconsistencies and for reflexive analysis. | ||||

Ethics

Research processes were guided by safety for participants and consistent with academic and criminology practical guidance.Citation34,35 The National Research Ethics Service (NRES London-Westminster committee) approved the stakeholder interview study (11/LO/1832 December 6th 2011) and anonymous prevalence study (Ref. 12/LO/0165 January 31st 2012). Abortion provider ethics and R&D approval were obtained (Ref.2012/05/SM May 9th 2012).

Analysis

Transcribed interview data were analysed using grounded theory, an inductive and deductive processCitation36 to ensure the thematic analysis was data-driven. Preliminary themes were extracted by LPK and independently coded (LPK/SB). Survey comments were analysed by three researchers (LPK/SB/MH). Triangulation and validation were achieved via the feedback workshop. Feedback group workshop sheets were analysed by three researchers (LPK/SB/MH). Regular two-monthly meetings were held (LPK/SB) to ensure research quality, discuss emerging results, hypotheses, experiences and implications for future service design.

Results

Seven themes were identified in the analysis of data, which are presented below:

Fragmented pathways into abortion services do not lend themselves to integrated IPV enquiry

Field work and interviews revealed that women could access abortion services locally by having received a referral by a general practitioner (GP) or other health provider, seen an advertisement, or checked the abortion provider websites. Different organisations were sub-contracted by the NHS to provide parts of the care for women along the pathway to abortion services (i.e., website, telephone booking, counselling, initial appointment and procedure). Very few service providers knew which pathway for abortion women with experience of IPV took. They did not know what, if any, IPV enquiry had been done nor what IPV services were available. There was no consistency in approach to IPV by organisations working independently from one another. Health providers highlighted that there are different pathways to abortion services, but felt that GPs might be best placed to screen for IPV. However, a local policy of self-referral meant that women did not need referral from their GPs, although all women had to phone a dedicated central number to book an initial abortion appointment.

“… it does get complicated! Because there are two levels of contract, so there’s the contract for the provision of the [abortion] service and then there’s the contract for, if you like, the booking and … organising of the service.”

(Abortion provider, interview)

Abortion provision is under attack

Field observations showed women and the researcher had to walk past, and were approached by, anti-abortion campaigners.Citation37 There were a number of contemporaneous media stories about abortion restrictions,Citation38 gestation limits,Citation39 compulsory counselling,Citation40 and threats to release women’s names after a major service provider database was hacked.Citation41 In this national context, some abortion providers were concerned about the ramifications of focusing on IPV as the vast majority of women accessing abortion services were not experiencing IPV:

“… there is a real issue actually, a political issue that’s going on now …. if we go back to a woman’s right to choose, which we have to believe in, and people who make decisions that aren’t victims.” (Commissioner, interview)

Service providers are committed to integrated IPV and abortion services in theory but this does not happen in practice

Interviews with service providers and field observations revealed that many initiatives tried to tackle violence against women. IPV services were funded by local government and were linked to parts of the health sector (with IPV advocates working in maternity, genitourinary medicine, accident and emergency, general practice) but not to abortion providers. On visiting abortion provider sites (two independent, one NHS), some leaflets about IPV were available and posters were seen on walls. Some of these were out of date. When contact details were provided these were to national hotlines only.

Desk review of webpages found national health information about abortion services contained little or no mention of violence. Abortion provider websites did not mention violence at all. Field work revealed that current call station operatives, whilst briefed on risks, did not ask about IPV. One national abortion provider had an official policy for vulnerable adults, which stated that, in the event of discovering abuse, managers should be informed immediately and police or ambulance should be called if there was physical injury. Interviews identified only one abortion provider who had introduced a non-specific screening question into pre-abortion counselling – “are you safe at home?” (though this does not recognise non-cohabiting IPV) – and had incorporated this into short accompanying training with plans for referrals to IPV services searched for online. The other abortion provider had no specific training for staff, who did not know what process to follow. There had been a one-off workshop set up by the police. Although there were clear child protection pathways and overriding of confidentiality, there was confused policy about over 18s who did not want them to respond. IPV had occasionally been identified, usually treated as an emergency, with police seen as the key source of help, although there had not been good experiences of calling them. For example, in one case the police arrived six hours after the abortion provider called following a disclosure of current violence for which the woman wanted police support.

Misperceptions and mismatched views about the extent of violence experienced by women accessing abortion

The majority of interviewees and women who participated in the survey recognised some abortion service users would be facing IPV. On the whole, abortion provider interviewees and feedback workshop responders were shocked by the high rates of abuse found in women seeking abortion, both from the systematic reviewCitation16 and the local prevalence studyCitation33 and recognised that IPV had to be taken more seriously. Despite underestimating the extent or believing IPV rare, every abortion provider could recall cases – often memorable and traumatic – where women had disclosed:

“She just told us that she had this rough sex, which was really rape, and it was a man who said he was a pastor and everything.”

(Abortion provider, interview)

IPV providers talked about “huge” levels of violence, some feeling that abortion was a small part of a woman’s difficult story, and relatively easy to deal with. All IPV providers and some survivors recounted stories of abortions under duress. Those in senior positions in abortion services acknowledged clinicians had dealt with cases but did not see a major problem:

“I don’t think [an IPV service] would be viable for us… I’m not convinced that there’s enough [IPV] that we see, that becomes apparent to us, that would warrant that.”

(Abortion provider, interview)

Integrating two stigmatised services poses opportunities and threats

Interviewees and workshop participants were divided about responses within abortion services. Some were enthusiastic:

“If you said to me, would I want that [IPV service] to be available to me, I’d say absolutely.”

(Abortion provider, interview)

The majority of the 64 current abortion service users who gave a free-text answer, whether experiencing IPV or not, supported the idea of a support service, recognising that women may be isolated, might need and seek help and protection:

“I would be more likely to seek help at this time due to my vulnerability.”

(Abortion service user, previous experience of IPV, questionnaire)

Some service providers felt abortion was stigmatised, but user and provider interviewees anticipated benefits of integrating with specialist IPV services:

“… when I went to [health-based IPV provider] I really opened up to them, I told them everything, the truth about everything….”

(IPV survivor, previous abortion, interview)

Addressing IPV might avoid some coerced abortions, but not all, and this was reinforced by the experience of IPV providers and a service user who sounded a note of caution:

“I was being seen by the advisor, but like I said, I lied. I didn’t really tell her the truth [about the violence], even though she’d have helped me.”

(IPV survivor, previous abortion, interview)

Looking back, she explained she was not ready to disclose at that time.

There are practical barriers to designing integrated services that ensure women’s safety and agency

There was a consensus about practical concerns raised in interviews, field work and feedback workshops. Funding, capacity, staff capability and training, detailed timing of any intervention (pre- or post-abortion), and sustainability were posed as programmatic barriers to introducing IPV services to an otherwise streamlined abortion service. Any quality improvement must not endanger or further stigmatise women, nor make access difficult:

“Greater clarity on what actions to take for front line services … Must not distract from main [abortion] service… Must be robust – ad hoc service provision may put women at risk…”

(Workshop feedback)

There were also design issues flagged up if introducing IPV interventions in abortion services. Should we aim for a universal approach where every woman is screened for IPV and given equal high quality advice? How can the pathways be kept separate so that women do not feel the abortion is contingent on their answers to IPV questions? Is it ethical to offer information only after abortion, for example on discharge? Providing IPV services is not easy. Abortion procedures can be demanding and emotional (depending on gestation, method and personal circumstances), so additional questioning might be unhelpful. There was no agreement about IPV enquiry (whether screening or case-based enquiry), its timing (before, on the day, or after the termination itself) or appropriateness (asking or providing a universal intervention without disclosure):

“Yes, it might be the only chance the person has to speak about the situation. No, it’s a long day within the service, too much.”

(Abortion service user, no IPV, questionnaire)

There are ideological differences between providers of services to women

Although the majority of women supported addressing IPV in the abortion clinic, providers contested whether IPV services should be health- or community-based. Based on their experiences of working with women, some felt women would prefer not to return to the abortion clinic to see a specialist adviser, others felt that as women’s views were respected in abortion services (e.g., not informing the GP routinely without explicit consent) this might make the setting safe and advantageous. Confidentiality is taken seriously in the private, supportive, women-friendly setting of an abortion clinic. However, there was potential for conflicting ideologies at the interface of abortion and IPV services as the IPV providers were not all profoundly pro-choice:

“For many young people, they’ve been brought up knowing it [abortion] is an option, you know, almost a form of contraception.”

(IPV provider, interview)

Workshop respondents urged extrapolating best practice from other settings, user involvement and monitoring impact. Service users might have different needs, e.g. by age, and should be involved when designing or researching innovations. There were concerns that women might not disclose violence, maybe for fear of not getting the abortion. Publicly raising the issue of IPV screening might risk the political imposition of mandatory “issues counselling” (as part of an anti-abortion agenda) that can be problematic and it would be important to avoid stigma.

“Women are faced with, you know what’s sometimes called a crisis pregnancy, I’m not fond of that term, but just for lack of a better term, um, and it’s a problem, and they want to get that problem sorted out, and we provide a solution to that problem, and then they want to move on with their lives.”

(Abortion service provider, interview)

Discussion

This study extends previous findings, that IPV remains an unaddressed issue within abortion services,Citation16,33 but it also demonstrates the complexities of integration when trying to provide assistance. Most abortion and IPV service providers recognise that some abortion-seeking women experience IPV and have unidentified, unaddressed needs but are unsure that abortion and IPV services can, or should, be integrated. How any intervention might be organised is contested: questions remain about whether, when and how to raise the topic and what to then offer. Two major anxieties surfaced: a practical concern, in terms of interrupting a streamlined service that suits the majority of patients and staff, and a conceptual concern in terms of stigmatising abortion seekers as victims in crisis. Considering these, the prior hypothesis that a nearby, established, integrated health-based IPV service would simply be transferable to abortion services was found to be wanting.

Study strengths include the use of multiple sources of information; the involvement of major national abortion providers and interviews with users and the full range of service providers involved in women’s pathways, ensured comprehensiveness. Validity was tested by seeking feedback on the preliminary results. Limitations included using one locality in a high income country with legal safe abortion services, and variable quality of data sources. Furthermore, few IPV survivors were recruited for interviews, though they had multiple abortion experiences. Although interviewees and service users were from wide, diverse backgrounds, the study was not designed to pick up cultural and ethnic variation, and is subject to recruitment and selection bias. There were a number of issues that were raised in the interviews that we were not able to explore in as much depth as we would have wished, such as the issue of stigmatisation of abortion and IPV services, and why and how this happened.

No similar study has examined the integration of abortion services and IPV services, which may not be surprising given the difficulty of conducting research at the intersection of two ‘hard-to-research’ areas.Citation42 This work complements previous studies that have found resistance and vulnerability to stigmatisation pertaining to the workforce who provide abortions,Citation43 variability in clinicians’ confidence about routine IPV enquiry and the influence of health setting.Citation44 A situational analysis from India examined the intersection of abortion, violence and women’s human rights, which showed that in the absence of adequate social conditions and gender equality, abortion only afforded temporary relief to women in oppressive situations.Citation45

Our findings show that abortion providers and clinicians lack training and have limited knowledge about how to respond to cases of IPV. Clinicians should be able to inform women presently using abortion services of relevant support (whether disclosing IPV or not, and whether for themselves or for other women they may know). They need training to ask questions skilfully and respond non-judgementally. A clash of safety and agency was identified for a few cited individual cases where abortion was a means of escaping violence or its consequences (e.g., rape), or where women experiencing coercive control denied IPV to obtain abortion under duress. Stakeholders suggested ways to integrate services to promote safety and agency concurrently, such as identifying opportunities to bypass staff and signpost women to sources of help or direct self-referral (e.g. via websites/ posters), without disrupting the abortion pathway. However, information has to be up-to-date and providers must monitor pathways they think are being used despite little multi-agency work. IPV and other services need training about abortion care and the importance of being non-judgemental.

At a policy level, clear leadership is needed to protect abortion rights and change the dynamic of multiple stigmatisation, particularly as IPV may be a reason for seeking abortion. Potential individual or integrated service interventions need rethinking. Research should examine whether the timing of opportunistic or routine IPV enquiries affects disclosure and referrals, influences stigma and improves or worsens women’s safety, taking into account cultural and ethnic factors. Novel interventions could focus on broader public health education, community awareness raising, and direct access to services and information (peer-to-peer support, or new technologies such as video or web-based information) in parallel to, and alongside, the abortion pathway. User-led and pro-choice interventions should involve IPV survivors in design, research and field work. Evaluation must examine service boundaries, the impacts of fragmentation on access and uptake, the commissioning of IPV and abortion services, whether the vulnerable women fall through gaps in services, and consider unintended harms. Cost implications and the impact of different budget streams in the NHS (and elsewhere) on services need to be examined. It should also be taken into consideration that not all IPV service providers are automatically pro-choice.

Conclusions

This single setting situation analysis emphasises that the context of healthcare work and local conditions matter. Abortion services see agency and women’s control over their own bodies as fundamental to sexual and reproductive health and human rights and can provide woman-centred, confidential and non-stigmatising settings. Globally, healthcare services are not always women-friendly. Human rights abuses can occur within and outside healthcare environments. Activists and innovators concerned about intersecting women’s rights issues need to consider this time, this environment and these particular resources. IPV services also have a rights-based, survivor-led, agency-enhancing approach to women’s empowerment. Interventions must consider women’s safety and agency, local context and the integrity of separate pathways. There is need for more innovation, especially looking for harms when abortion is under attack, as the starting assumption that integrated services would be desirable and transferable was not found to be the case in this context. This article cannot tell providers and women’s health advocates what to do in terms of organising IPV and abortion services, but it highlights questions and issues to think about in their own context. This article also points to the need to more research in the area.

Authors' contribution

The authors were involved as follows: LPK SB conception, design, analysis, interpretation; LPK MH SM data acquisition; LPK, SB, MH drafting of article; all authors were responsible for revision and final approval of manuscript. KCL is the guarantor for the study.

Funding

Friends of Guy’s Charity (charity number 264150) funded the study. The authors had full access to all of the data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing Interest

LPK had financial support from Friends of Guy’s Charity for the submitted work; SM was a Masters student at KCL; SB has previously set up and researched domestic violence services within maternity care. She gave obstetric consultancy advice to Marie Stopes International (2011-12) and is a member of World Health Organisation Reproductive and Sexual Health and Human Rights for women living with HIV. Guideline Development Group (2014-15). No other financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Acknowledgements

We thank Susan Fairley Murray and Loraine Bacchus for their encouragement and comments on an earlier draft, the Friends of Guys Charity for funding and all the participants who contributed to study completion.

Image 1

Could you tell me about your present job and responsibilities?

[prompt with respect to reproductive health services and DV services]

How do you think abuse and violence impacts the lives of women using your services?

[prompt: which women, how frequent]

If a woman in your services discloses abuse (or abuse is suspected), what are the current procedures for dealing with it?

[prompt: who deals with it, where are they referred, documentation, referrals, monitoring?]

Do you feel that what is in place now meets the needs of women?

| • | Are there any other special groups of women with different needs? [prompt: vulnerable, ‘red-flag’] | ||||

| • | Are there women who current services fail to capture? | ||||

| • | Would anything we have discussed be different for younger women? [prompt: <16, <18, young >18] | ||||

What are the barriers and facilitators to providing good quality services?

[prompt: asking the Qs, attitudes of staff, training]

How could present services be improved?

What is your view on the advantages and disadvantages of routinely enquiring about GBV in all women using your service?

Do you perceive there is a need for new services?

Considering onward referral, are you happy with the procedures in place?

What would be the advantages or disadvantages of on-site, close liaison with specialist domestic violence advocacy services?

[prompt: quality, relationships with staff, special groups of women]

Do you think services need to be different for teenagers/ young women? And in what way?

Are there any other groups of women who you think need specially designed domestic violence services?

Do you have any other comments on this issue?

Image 2

Do you think abuse and violence are a problem in the lives of many women who use abortion and/or gynaecology services?

Do you think health services have anything to offer women in violent relationships?

[If no, why not?]

If yes, what kind of help do you think women would want?

What do you think the health service can realistically offer women in violent relationships?

[prompt: priorities]

And what do you think health services should not do?

[prompt: poor practice, unhelpful, unsafe]

Do you think that gynaecology services are a good place to ask about domestic violence?

[prompt: why? why not? time, DV trajectory]

Do you think that abortion services are a good place to ask about domestic violence?

[prompt: why? why not? time, DV trajectory]

How do you think women in violent relationships would feel about being asked routinely about domestic violence in gynaecology or abortion services?

Do you think it would be different to being asked in maternity (or GUM) services?

We are considering setting up a new domestic violence service in abortion or gynaecology services. Have you any suggestions about how this should operate?

Is that anything that should be avoided?

What would be the advantages or disadvantages of having domestic violence services at the same place or very near where the health service is provided and which interact with staff at the hospital?

[prompt: quality, relationships with staff, special groups of women]

What would be the advantages and disadvantages of referring women to services that are not connected to the hospital?

Do you think there are any special groups of women with different needs in terms of domestic violence services?

Should services be different for teenagers/ young women? Why, and in what way?

[prompt: experiences, needs, interactions with services, <16, <18, young >18]

Do you have any other comments not already covered?

Notes

* Over the lifetime of this project, language and terminology have been changing at local, national and international levels. As abortion only affects women and girls, the terms VAWG (violence against women and girls), and GBV (gender based violence) have been eschewed, and the more generic term ‘interpersonal violence (IPV)’ used in preference, to include both domestic and sexual violence, and which would cover other forms that might intersect with abortion (such as human trafficking or ‘honour’-based violence). Other terms are used if described by the specific services, policies or papers.

References

- E.G. Krug, L.L. Dahlberg, J.A. Mercy. World Report on Violence and Health. 2002; World Health Organisation: Geneva. (www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en/?).

- World Health Organization. Global and regional estimate of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. 2013; WHO: Geneva. (http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/9789241564625/en/).

- D.M. Patel, R.M. Taylor, on behalf of Institute of Medicine and National Research Council of the National Academies. Social and Economic Costs of Violence. Workshop Summary. Chapter 6. Direct and Indirect Costs of Violence. 2011; The National Academies Press: Washington DC, 33–83. (http://www.nap.edu/catalog/13254/social-and-economic-costs-of-violence-workshop-summary).

- A. Willman. Valuing the Impacts of Domestic Violence: A Review by Sector. S. Skaperdas, R. Soares, A. Willman, M. SC. The costs of violence. 2009; World Bank: Washington, DC, 57–96. (http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2009/03/11304946/costs-violence).

- World Health Organisation. Global status report on violence prevention. 2014. (http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/status_report/2014/report/report/en/).

- Lancet series. http://www.thelancet.com/series/violence-against-women-and-girls

- J. Chang, C.J. Berg, L.E. Saltzman. Homicide: A Leading Cause of Injury Deaths among Pregnant and Postpartum Women in the United States, 1991–1999. American Journal of Public Health. 95: 2005; 471–477.

- Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries (CMACE). Saving Mothers’ Lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006–08. The Eighth Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. BJOG. 118(Suppl. 1): 2011; 1–203.

- M. VA. Screening for intimate partner violence and abuse of elderly and vulnerable adults: A U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 158: 2013; 478–486.

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 518: intimate partner violence. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 119(2 Pt1): 2012; 412–417.

- C. García-Moreno, K. Hegarty, A.F. Lucas d’Oliveira. The health-systems response to violence against women. Lancet. 385: 2015; 1567–1579. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61837-7.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. NICE guidelines [PH50]. Domestic violence and abuse: how health services, social care and the organisations they work with can respond effectively. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph50/chapter/introduction. 2014

- L.J. O’Doherty, A. Taft, K. Hegarty. Screening women for intimate partner violence in healthcare settings: abridged Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 348: 2014; g2913. 10.1136/bmj.g2913. (Published online 2014 May 13).

- L.J. Bacchus, S. Bewley, G. Aston. Evaluation of a domestic violence intervention in UK maternity and sexual health services. Reproductive Health Matters. 18: 2010; 147–157.

- L. Bacchus, S. Bewley, C. Fernandez. Health sector responses to domestic violence in Europe: A comparison of promising intervention models in maternity and primary care settings. 2012; London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine: London. (Available online at: http://diverhse.eu/project-outputs/).

- M. Hall, L. Chappell, B. Parnell. Associations between domestic violence and termination of pregnancy: a systematic review. PLoS Medicine. 2014; 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001581.

- M.M. Holmes, H.S. Resnick, D.G. Kilpatrick. Rape-related pregnancy: estimates and descriptive characteristics from a national sample of women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 175: 1996; 320–324.

- A. Bankole, S. Singh, T. Haes. Reasons why women have induced abortions: evidence from 27 countries. International Family Planning Perspectives. 24(3): 1998. (117-127&152).

- A. Whitehead, J. Fanslow. Prevalence of family violence amongst women attending an abortion clinic in New Zealand. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 45: 2005; 321–324.

- L. Roth, J. Sheeder, S.B. Teal. Predictors of intimate partner violence in women seeking medication abortion. Contraception. 85: 2011; 76–80.

- E.R. Wiebe, P. Janssen. Universal screening for domestic violence in abortion. Women's Health Issues. 11: 2001; 436–441.

- V.L. Souza, S.L. Ferreira. Influência da violência conjugal sobre a decisão de abortar. Impact of spouse violence on the decision to have an abortion. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem. 53: 2000; 375–385.

- T.W. Leung, W.C. Leung, P.L. Chan. A comparison of the prevalence of domestic violence between patients seeking termination of pregnancy and other general gynecology patients. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 77: 2002; 47–54.

- G. Evins, N. Chescheir. Prevalence of domestic violence among women seeking abortion services. Womens Health Issues. 6: 1996; 204–210.

- S.N. Chowdhury, D. Moni. A situation analysis of the menstrual regulation programme in Bangladesh. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24 Suppl.): 2004; 95–104.

- M.H. Nguyen, T. Gammeltoft, V. Rasch. Situation analysis of quality of abortion care in the main maternity hospital in Hai Phang, Viet Nam. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(29): 2007; 172–182.

- N. Ojha, K.D. Bista. Situation analysis of patients attending TU Teaching Hospital after medical abortion with problems and complications. JNMA; Journal of the Nepal Medical Association. 52(191): 2013; 466–470.

- The report of the Taskforce on the Health Aspects of Violence Against Women and Children Chair: Alberti G.. Responding to violence against women and children – the role of the NHS. http://www.health.org.uk/media_manager/public/75/external-publications/Responding-to-violence-against-women-and-children–the-role-of-the-NHS.pdf. 2010

- Her Majesty’s Government. Call to end violence against women and girls. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/97903/vawg-action-plan.pdf. 2011

- Mayor of London. The way forward: taking action to end violence against women and girls. Final strategy 2010-2013. https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/'The%20Way%20Forward'%20strategy.pdf. 2010

- Safer Lambeth Partnership. Violence Aainst Women and Girls Strategy 2011-14. http://www.lambeth.gov.uk/sites/default/files/sc-safer-lambeth-vawg-strategy-2011-14.pdf. 2010

- Safer Southwark Partnership. Southwark Violent Crime Strategy 2010-15. http://www.southwark.gov.uk/downloads/download/2640/southwark_violent_crime_strategy. 2010

- S. Motta, L. Penn-Kekana, S. Bewley. Domestic violence in a UK abortion clinic: anonymous cross-sectional prevalence survey. The Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care. 2014 May 20; 10.1136/jfprhc-2013-100843.

- R. Jewkes, C. Watts, N. Abrahams. Ethical and methodological issues in conducting research on gender-based violence in Southern Africa. Reproductive Health Matters. 8(15): 2000; 93–103.

- R.M. Lee, B. Stanko. Researching violence: essays on methodology and measurement. 2003; Routledge: London.

- C. Seale. The quality of qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry. 5: 1999; 465–478.

- Anonymous. Pregnant woman accuses anti-abortion protesters outside London clinic of making women feel guilty. 4 December. 2014; The Independent. (http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/pregnant-woman-criticises-antiabortion-protesters-for-filming-outside-london-clinic-9903105.html).

- S.R. Jeremy. Hunt is controversial appointment as Health Secretary. 4 September. 2012; The Telegraph. (http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/politics/conservative/9520269/Jeremy-Hunt-is-controversial-appointment-as-Health-Secretary.html).

- R. Watts. Senior ministers call for cut in abortion limit. 6 October. 2012; The Telegraph. (http://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/womens-politics/9591847/Senior-ministers-call-for-cut-in-abortion-limit.html).

- B. Quinn, D. Campbell. Abortion providers alarmed over counselling plans. 28 June. 2011; The Guardian. (http://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/jun/28/abortion-providers-alarm-government-proposals).

- BBC. Arrest after BPAS abortion advice service site hacked. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-17309772, 9 March. 2012

- R. Jewkes, Y. Sikweyiya, N. Jama-Shai. The challenges of research on violence in post-conflict Bougainville. Lancet. 383(9934): 2014; 2039–2040.

- J. O'Donnell, T.A. Weitz, L.R. Freedman. Resistance and vulnerability to stigmatization in abortion work. Social Science & Medicine. 73(9): 2011; 1357–1364.

- C. Torres-Vitolas, L.J. Bacchus, G. Aston. A comparison of the training needs of maternity and sexual health professionals in a London teaching hospital with regards to routine enquiry for domestic abuse. Public Health. 124: 2010; 472–478.

- S.B. Sri, T.K. Ravindran. Safe, accessible medical abortion in a rural Tamil Nadu clinic, India, but what about sexual and reproductive rights?. Reproductive Health Matters. 22(44 Supplement 1): 2015 Feb; 134–143.