Abstract

Abstract

As of 31 July 2014, some 27 countries in sub-Saharan Africa had adopted HIV-specific legislation to respond to the legal challenges posed by the HIV epidemic. However, serious concerns raised about these laws have led to calls for their repeal and review. Through the theory of “smarter legislation”, this article develops a framework for analysing the concerns relating to the process, content and implementation of HIV-specific laws. This theoretical framework provides specific guidance and considerations for reforming HIV-specific laws and for ensuring that they achieve their goals of creating enabling legal environments for the HIV response.

Résumé

Au 31 juillet 2014, près de 27 pays d’Afrique subsaharienne avaient adopté une législation spécifique sur le VIH pour répondre aux questions juridiques posées par l’épidémie de VIH. Néanmoins, les graves préoccupations suscitées par ces lois ont donné lieu à des appels pour qu’elles soient abrogées et révisées. Moyennant la théorie de la « législation plus intelligente », cet article fournit un cadre pour analyser les préoccupations relatives au processus, au contenu et à l’application de lois spécifiques relatives au VIH. Ce cadre théorique donne des conseils précis et des considérations en vue de réformer ces lois et veiller à ce qu’elles parviennent à leur objectif qui est de créer des environnements juridiques habilitants pour la réponse au VIH.

Resumen

Para el 31 de julio de 2014, unos 27 países en Ãfrica subsahariana habían adoptado legislación referente al VIH específicamente, con el fin de responder a los retos jurídicos que presenta la epidemia del VIH. Sin embargo, graves inquietudes planteadas acerca de estas leyes han producido llamados a su revocación y revisión. Por medio de la teoría de “legislación más inteligente”, este artículo crea un marco para analizar las inquietudes relacionadas con el proceso, contenido y aplicación de leyes referentes al VIH. Este marco teórico ofrece orientación y consideraciones específicas para reformar las leyes referentes al VIH y asegurar que logren sus objetivos de crear ambientes legislativos que propicien la respuesta al VIH.

Introduction

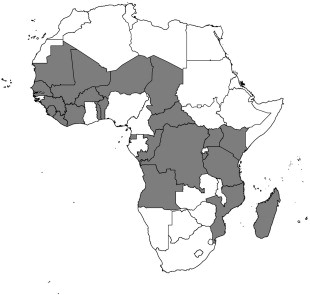

Experience and evidence from more than 30 years of the HIV epidemic have shown that enabling legal environments – including protective legislation – can play an important role in advancing the HIV response.Citation1 However, early reviews of the legal environment relating to HIV in countries across the world found that existing legislative frameworks were not adapted to the legal, social and human rights challenges raised by the epidemic.Citation2 Many countries have taken legislative measures to address the legal and human rights issues relating to HIV.Citation3 In sub-Saharan Africa, the majority of countries adopted HIV-specific legislation. As of August 2014, 27 sub-Saharan African countries had adopted such laws (see ).

HIV-specific laws, a single piece of legislation exclusively dedicated to HIV, cover issues such as HIV education and information, HIV testing and counselling, biomedical HIV research, non-discrimination based on HIV status, HIV prevention, treatment, care and support as well as penalties for various acts such as HIV non-disclosure, exposure or transmission.Citation4

Since their adoption, the great majority of HIV-specific laws have raised serious concerns relating to coercive provisions.Citation4,5 Research has also identified several flaws in the content of HIV-specific laws, such as lack of clarity, contradictory provisions, and failure to identify implementation agencies.Citation6

These concerns have generated questions about the rationale, process, content and implementation of most HIV-specific laws in sub-Saharan Africa. However, repealing HIV-specific laws in sub-Saharan African countries will prove challenging, with likely resistance from parliamentarians and other stakeholders at country and regional levels who have supported their adoption.Citation7 In addition, the removal of HIV-specific laws will create gaps in national HIV legal frameworks because in many countries they are the only legally binding instruments that explicitly guarantee some protection for people living with HIV and address legal issues relevant to the epidemic. On the other hand, efforts to review and improve HIV-specific laws have proved successful in a few countries in the region, including Sierra Leone, Guinea and Togo, thus suggesting that this approach is worth pursuing.Citation4

This article explores the application of the principles and approaches of “smarter legislation” to guide the review of HIV-specific laws. Following an overview of the human rights and implementation challenges in HIV-specific laws in sub-Saharan Africa, the article introduces the notion of “smarter legislation” and its application on key issues and challenges in the context of HIV-related law-making.

Human rights and implementation concerns in HIV-specific laws

Analyses of HIV-specific laws adopted in sub-Saharan Africa have shown that they contain some human rights protections covering areas such as non-discrimination, access to HIV information and education, protection in the workplace and informed consent in the context of research relating to HIV.Citation4,5 These laws also contain various forms of restrictive and coercive measures.Citation4,5 A recent review of HIV-specific laws in 26 sub-Saharan African countries found that 17 countries have broad provisions that allow for involuntary disclosure of HIV status of people living with HIV to their sexual partners, and 24 countries have provisions allowing for criminalisation of HIV non-disclosure, exposure or transmission (see Table).Citation4

Table 1 Example of coercive and restrictive provisions in HIV-specific laws

These coercive provisions not only infringe upon human rights, including the rights to autonomy, privacy and security; they have also been proved to negatively impact efforts to advance effective responses to HIV, as highlighted by the International Guidelines on HIV/AIDS and Human Rights:

“People will not seek HIV related counselling, testing, treatment, and support if this could mean facing discrimination, lack of confidentiality and other negative consequences…[C]oercive public health measures drive away the people most in need of such services and fail to achieve their public health goals of prevention through behavioural change, care and health support.” Citation8

A further concern in HIV-specific laws is the limited or lack of attention to the legal and human rights issues affecting many key populations, such as women and girls, sex workers and men who have sex with men, in spite of evidence on their greater vulnerability to HIV.Citation4

More than ten years after the first HIV-specific laws were adopted, there is limited evidence of their effective implementation and enforcement. Findings from surveys conducted in a number of countries that have adopted HIV-specific laws suggest that there is insufficient awareness of these laws among key stakeholders, including people living with HIV, who are arguably their primary beneficiaries.Citation9 In several countries, critical implementation measures that are expected to translate or accompany these laws have not been adopted several years after they were passed.Citation10

Intrinsic flaws in the normative content of HIV-specific legislation are considered to have hindered their implementation and enforcement. These challenges include vague provisions that are difficult to implement or enforce. In several countries, HIV-specific laws fail to address their relationships with other legislation dealing with similar issues. This situation is likely to lead to confusion among target populations and implementing actors regarding which law is to be applied in specific circumstances. Another important implementation and enforcement challenge is that HIV-specific laws often do not designate specific implementation agencies for ensuring that they are enforced or for addressing gaps and challenges in their implementation and enforcement.Citation6

Conceptual framework: “smarter legislation” in the context of HIV

To be effective, HIV legislation should be informed by the principles and approaches of “smarter” legislation. The notion of “smarter legislation” was coined by Ingram and Schneider. According to these authors, “[f]lawed statutes are the source of many implementation problems and failed policies.”Citation11 Ingram and Schneider argue that whether any legislation is effectively implemented and enforced depends largely on the normative content of the law and how it addresses key issues such as sound policy, clarity of provisions and supportive implementation agency.Citation11 On the basis of this theory of “smarter legislation” and the principle of participation – which is central to HIV policy – the present article highlights three key considerations that should guide the development of smarter HIV legislation.

First, smarter HIV legislation should be based on participatory law-making processes. Ensuring public participation in law-making processes, particularly on issues with important legal and social implications such as HIV, is an indicator of good and inclusive governance.Citation12 Public participation in law-making is a human right guaranteed under a number of global, regional and national norms.Citation12 In the context of HIV, the involvement of key stakeholders, including people living with HIV and populations most affected by the epidemic, in policy and decision making is considered essential to effective responses. This imperative is enshrined in the principle of the greater involvement of people living with HIV (GIPA) in all aspects of the response to HIV. GIPA was championed by people living with HIV and has been endorsed by countries globally through the Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS.Citation13

Second, the content of smarter HIV legislation should be based on sound public health policy and human rights principles. Evidence and experience from more than 30 years of HIV response have shown that effective responses are those that protect individuals against coercion and other restrictive measures in access to HIV prevention, treatment and care services.Citation8 These include the protection of informed consent and confidentiality, and eliminating overly broad HIV criminalisation and other criminal measures against key populations at higher risk of HIV infection.Citation8

Third, smarter HIV legislation should give due consideration to factors that influence whether and how legislation is implemented. In general, the implementation of law or policy is influenced by multiple factors. Some are extrinsic factors relating to the broader environment, such as social, political, economic, financial and administrative conditions in a given context.Citation6 Others are intrinsic factors, which relate to the normative content of the legislation and policy. Intrinsic factors address issues such as the clarity of normative provisions, the precision of the directives provided to the target population and implementers of the law as well as the identification of implementing agencies to advance the legislative goals identified in the law.Citation6 Since these intrinsic elements are under the direct control of the drafters of legislation, it is recommended that they be given due consideration in HIV-related law-making for ensuring the effective implementation of the resulting legislation.

Making smarter HIV laws: applying the conceptual framework to HIV-specific laws in sub-Saharan Africa

This section explores approaches for ensuring that the content of HIV-specific laws takes into account key elements that will contribute to improving their normative content and implementation.

Participatory process in HIV-related law-making

The great majority of HIV-specific laws adopted in sub-Saharan Africa did not allow the meaningful participation of key stakeholders in their development. For instance, in hearings and consultations relating to HIV-specific laws adopted in West and Central African countries between 2005 and 2007, people living with HIV and human rights organisations were often not included.Citation5

These actors should participate in parliamentary hearings and other consultations organised in the context of HIV-related law-making, and their involvement should not be symbolic; their concerns should be addressed in the laws. This requires specific and strategic engagement of civil society and law-makers on issues of concern to people living with HIV and key populations in order to identify solutions in each national context. For instance, recent HIV-related laws that have been developed through more inclusive processes in countries such as Senegal, Guinea and Côte d’Ivoire are considered to have better human rights provisions and to take into account best available public health recommendations.Citation4

Sound public health and human rights-based provisions

The great majority of HIV-specific laws in sub-Saharan Africa have embraced coercive and restrictive measures that ignore sound public health and human rights recommendations. Creating smarter HIV-specific laws will require addressing existing coercive provisions in these laws. Review efforts should focus on those provisions that have attracted the most criticisms and concerns and that are likely to have greatest impact on the HIV response. This includes provisions allowing for overly broad criminalisation of HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission which are often used to illustrate the embrace of coercive approaches in HIV legislation.

Over the years, civil society organisations have mobilised against HIV criminalisation provisions, demanding their removal. In some instances, these calls for change have been successful. This was the case for example in Sierra Leone where the provision allowing for explicit criminalisation of mother-to-child transmission of HIV was removed by parliament in 2011.Citation4 More recently, in Kenya, the provision criminalising HIV exposure and transmission was declared unconstitutional by the High Court.Citation14 Efforts should therefore continue to support countries to remove or, at the very least, amend the provisions relating to HIV non-disclosure, exposure or transmission to ensure that they are in line with sound public health evidence and human rights principles.

Creating smarter HIV legislation will also require addressing the silence or inappropriate provisions on women, children and other key populations. Across sub-Saharan Africa, women and girls constitute a population particularly impacted by the epidemic.Citation15 AIDS is also the leading cause of death among young people in Africa.Citation16 Yet, the vulnerabilities to HIV and the need for HIV services of these populations are not addressed in HIV laws.Citation5 The drafters' justification is that most countries already have legislation applicable to women and children and that it is not necessary to replicate in HIV laws norms that already exist in other laws.Citation17 Some also argue that issues relating to these populations could be addressed through regulations, policies and programmes which may be best suited for responding to their vulnerabilities.Citation17

In spite of these arguments, failure to address the specific HIV vulnerabilities and needs for HIV services of women and girls, young people and other key populations in HIV-specific laws is a gap and concern. Provisions in other legislation relating to women, children and other key populations are often inadequate to address HIV issues pertinent to these populations. In almost all countries in the region, there are no legal provisions relating to the protection of key populations, such as sex workers, men who have sex with men and people who inject drugs, and their access to HIV services. In addition, as compared to regulations and policy documents, laws are best suited for setting general principles relating to the protection and access to services for populations that face multiple forms of legal, social and health barriers and vulnerabilities. This is because legislation provides rights-holders with a clear claim on which to hold government accountable.

Implementation and enforcement of HIV-specific laws

Smarter HIV-specific laws should comprise clearly drafted provisions that explicitly address their relations with other legislation dealing with similar subjects.Citation6 Since HIV touches upon various areas, this would prevent potential conflict of laws rather than leaving the determination of the applicable legislation to the discretion of implementers or judges.Citation6 Clarity is also important because implementers and law enforcement agents are inclined to apply provisions that deal directly with the issue at hand. For instance, in relation to HIV and employment, implementers and law enforcement agents will “naturally” implement existing employment legislation rather than the provisions relating to HIV and employment that are provided in the HIV-specific legislation. This is because implementers and law enforcement actors are more likely to know about and be conversant with the provisions of existing legislation dealing with a specific area such as employment, rather than the provisions of lesser known HIV legislation.

In many countries, the recourse to coercive provisions in HIV-specific laws has led to serious opposition, resulting in lengthy law reform processes or court cases that have thwarted the implementation of the law.Citation4,14 For instance, in a number of West and Central African countries, coercive provisions in HIV-specific laws, such as restrictions to HIV education for adolescents, compulsory HIV testing for sex workers and overly broad criminalisation of HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission have generated mistrust among civil society actors who perceived these laws as violating rather than supporting human rights.Citation5,18 This situation has reportedly hindered the willingness and ability of civil society to invoke and use these laws.Citation19

HIV-related legislation should clearly designate agencies responsible for implementing key provisions. For instance, specific directorates within ministries of employment with relevant expertise could be explicitly tasked with the implementation of measures addressing discrimination in employment. HIV-specific laws should also provide a timeline within which the implementation agency is to take action and deliver on specific issues. In particular, such timelines should be set for the development of regulations or the setting up of institutions mandated by the law. In addition, to ensure progress in the overall implementation and enforcement of HIV legislation, it is important to task an entity with monitoring the implementation of the law. The only country with a mechanism to ensure the overall enforcement of its HIV legislation is Kenya, which has established an HIV-specific Tribunal under its HIV law.Citation20 This Tribunal has been given broad powers to ensure the implementation and enforcement of this legislation. A review of the composition, mandate and work of the Tribunal has concluded that in spite of the financial and resource challenges that it faces, the Tribunal can be an effective mechanism for ensuring the implementation and enforcement of the HIV law of Kenya.Citation20

Discussion

Human rights and public health concerns and gaps in HIV-specific laws call for urgent efforts to address and review them in order to support effective responses to HIV. Enabling legislative environments, including protective HIV laws, are necessary to unlock the barriers that prevent people living with or vulnerable to HIV from accessing HIV prevention, treatment and care services. Advocacy by civil society has shed light on these concerns and, in some countries, created momentum for change through law reform or litigation. International organisations, including UNAIDS and UNDP (in the context of the follow up to the recommendations of the Global Commission on HIV and the Law) are also supporting HIV-related law reform efforts through financial and technical assistance to legal assessments and national dialogues.Citation21

Efforts to review HIV-specific laws have proven complex and challenging, often requiring several years of engagement. Yet, they are worthwhile endeavours because in many countries, HIV-specific laws are the only binding legal instruments explicitly addressing the HIV epidemic. Ending punitive provisions in these laws, and strengthening the implementation and enforcement of their protective norms is therefore important for creating an enabling environment for the HIV response. A number of tools to guide national legal assessments and consultative processes have been developed to enable law makers and other stakeholders to identify and address key issues and gaps in the review of HIV legislation.Citation22 Effective use of such tools will help improve the content of HIV-specific laws.

Ultimately, securing “smarter HIV laws” is not merely a technical endeavour requiring solely sound theory, and the application of public health and human rights principles. Smarter HIV laws require “smart politics”. This includes identifying key allies in parliament, government and among other key constituencies who will support the content and objectives of HIV-related legislation, particularly on socially sensitive issues.Citation23 Since several issues, such as age of consent to HIV services for children and the protection of prisoners and other key populations, are controversial in many sub-Saharan African countries, law reforms should seek to build understanding and support around these issues among key allies and leaders who could champion appropriate legal provisions. For instance, in Mauritius, sensitisation and engagement of members of parliament and other key national actors have enabled the adoption of HIV legislation that protects and ensures access to HIV services for people who inject drugs in spite of existing punitive laws against people who use drugs.Citation24 Similarly, in Senegal, effective engagement by civil society, the national AIDS programme and other stakeholders has ensured explicit mention of HIV services for men who have sex with men in the HIV law in spite of existing criminal legislation punishing same sex relations.Citation25 While these examples of protective provisions for key populations remain rare, they demonstrate that “smart” politics can translate into smart HIV laws in spite of political, social and religious sensitivities and challenges.

As the world mobilises to achieve the vision of ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 within the integrated framework of inclusion, equality and rule of law provided by the Sustainable Development Goals, creating enabling and protective legal environments is expected to receive renewed attention which would support efforts by civil society and others working to end punitive laws and other legal barriers to HIV responses.Citation26

Finally, even the smartest HIV-related legislation will have little impact unless it is accompanied by financial and other measures to support its implementation and enforcement. These include adopting rights-based implementing regulations (where necessary), providing resources to disseminate the law, and taking all needed measures to inform and train duty bearers (including health care workers, police and employers) and rights-holders (including people living with and affected by HIV and civil society) on the content of the law and avenues for obtaining redress in case of rights violations.

Conclusion

HIV-specific laws are now part of the legislative framework of a majority of countries in sub-Saharan Africa, with 27 countries having adopted such laws as of July 2014. In spite of serious concerns with these laws, much can be done to improve them. Reforms should be guided by considerations and approaches of “smarter legislation” that are based on participatory process, sound public health evidence and human rights principles, and that pay due attention to intrinsic factors that affect legislative implementation and enforcement. Building political alliances and leadership among law-makers and other key national stakeholders to support efforts to review and improve HIV-specific legislation is also key. Adopting the measures and approaches presented in this article will contribute to ensure the emergence of “smarter HIV legislation” in sub-Saharan Africa which will be critical to efforts to remove the legal barriers to the HIV response and to ensuring that no one is left behind in efforts to end the AIDS epidemic as a public health threat.

Acknowledgements and disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the policies or positions of UNAIDS. I am indebted to my thesis supervisor, Dr Ann Strode, for her comments on an earlier draft of this article.

References

- L.O. Gostin. The AIDS pandemic: Complacency, injustice, and unfulfilled expectations. 2004; University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill.

- S.J. Frankowski. Legal responses to AIDS in comparative perspectives. 1998; Kluwer Law International: The Hague.

- R. D’Amelio, E. Tuerlings, O. Perito. A global review of legislation on HIV/AIDS: the issue of HIV testing. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 28(2): 2001; 173–179.

- P.M. Eba. HIV-specific legislation in sub-Saharan Africa: A comprehensive human rights analysis. African Human Rights Law Journal. 15: 2015; 224–262.

- R. Pearshouse. Legislation contagion: The spread of problematic new HIV laws in Western Africa. HIV/AIDS Policy & Law Review. 12: 2007; 1–12.

- P.M. Eba, A. Strode. A framework for understanding and addressing intrinsic challenges to the implementation of HIV-specific laws in Sub-Saharan Africa. 2016. (forthcoming).

- R. Pearshouse. Legislation contagion: building resistance. HIV/AIDS Policy & Law Review. 13: 2008; 1–10.

- UNAIDS. International guidelines on HIV/AIDS and human rights, 2006 consolidated version. 2006; UNAIDS: Geneva.

- National Council of People Living With HIV/AIDS Tanzania (NACOPHA). The people living with HIV stigma index report: Tanzania. 2013; NACOPHA: Dar es Salam. At http://stigmaindex.org/sites/default/files/reports/Tanzania%20STIGMA%20INDEX %20REPORT%20-%20Final%20Report%20pdf.pdf.

- IRIN. La faible application de la loi VIH frappe plus durement les femmes. 19 August. 2009. Athttps://www.irinnews.org/fr/report/85808/niger-la-faible-application-de-la-loi-vih-frappe-plus-durement-les-femmes

- H. Ingram, A. Schneider. Improving implementation through framing smarter statutes. Journal of Public Policy. 10(1): 1990; 67–88.

- K.S. Czapanskiy, R. Manjoo. The right of public participation in the law-making process and the role of legislature in the promotion of the right. Duke Journal of Comparative and International Law. 19: 2008; 1–40.

- D. Stevens. Out of the shadows: greater involvement of people living with HIV / AIDS (GIPA) in policy. 2004; Futures Group, POLICY Project: Washington DC. At http://www.policyproject.com/pubs/workingpapers/WPS14.pdf.

- High Court of Kenya. Aids Law Project v Attorney General & 3 others. 2015. Athttp://kenyalaw.org/caselaw/cases/view/107033/

- UNAIDS. The gap report. 2014; UNAIDS: Geneva. At http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2014/UNAIDS_Gap_report_en.pdf.

- UNAIDS. Leaders from around the world are All In to end the AIDS epidemic among adolescents. 17 February. 2015. Athttp://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/pressreleaseandstatementarchive/2015/february/20150217_PR_all-in

- P.M. Eba. Capacity building workshop on human rights and gender in HIV legal frameworks – Final report. 16-18 April 2008. (on file with author).

- C. Kazatchkine. Criminalizing HIV transmission or exposure: the context of francophone West and Central Africa. HIV/AIDS Policy & Law Review. 14: 2010; 1–11.

- Liberia Network of People Living with HIV. Liberia PLHIV stigma index report. 2013; Liberia National AIDS Commission: Monrovia. At http://www.stigmaindex.org/sites/default/files/reports/Liberia%20%20People%20Living%20with%20HIV%20Stigma%20Index%20Final%20Report%202013.pdf.

- P.M. Eba. The HIV and AIDS Tribunal of Kenya: An effective mechanism for the enforcement of HIV-related human rights?. Health and Human Rights Journal. 18(1): 2016; 169–180.

- UNAIDS. UBRAF thematic report: Ending punitive laws, June 2015. 2014. Athttps://results.unaids.org/sites/default/files/documents/C1_Ending_punitive_laws_Jun2015.pdf

- UNDP. Legal environment assessment for HIV: An operational guide to conducting national legal, regulatory and policy assessments for HIV. 2014; UNDP: New York. At http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/HIV-AIDS/Governance%20of%20HIV%20Responses/UNDP%20Practical%20Manual%20LEA%20FINAL%20web.pdf.

- D. Altman, K. Buse. Thinking politically about HIV: Political analysis and action in response to AIDS. Contemporary Politics. 18(2): 2012; 127–140.

- HIV and AIDS Act, No 31 of 2006 of Mauritius.

- Loi n° 2010-03 du 9 avril 2010 relative au VIH/SIDA of Senegal.

- UNAIDS. UNAIDS Strategy 2016-2021: On the fast track to end AIDS. 2015; UNAIDS: Geneva. At http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/20151027_UNAIDS_PCB37_15_18_EN_rev1.pdf.