Abstract

Abstract

Medical abortion is a method of pregnancy termination that by its nature enables more active involvement of women in the process of managing, and sometimes even administering the medications for, their abortions. This qualitative evidence synthesis reviewed the global evidence on experiences with, preferences for, and concerns about greater self-management of medical abortion with lesser health professional involvement. We focused on qualitative research from multiple perspectives on women’s experiences of self-management of first trimester medical abortion (< 12 weeks gestation). We included research from both legal and legally-restricted contexts whether medical abortion was accessed through formal or informal systems. A review team of four identified 36 studies meeting inclusion criteria, extracted data from these studies, and synthesized review findings. Review findings were organized under the following themes: general perceptions of self-management, preparation for self-management, logistical considerations, issues of choice and control, and meaning and experience. The synthesis highlights that the qualitative evidence base is still small, but that the available evidence points to the overall acceptability of self-administration of medical abortion. We highlight particular considerations when offering self-management options, and identify key areas for future research. Further qualitative research is needed to strengthen this important evidence base.

Résume

L’avortement médicamenteux est une méthode d’interruption de grossesse qui, par sa nature, permet une participation plus active des femmes à la gestion, et parfois même l’administration des médicaments pour leur propre avortement. Cette synthèse de données qualitatives a examiné les données mondiales sur les expériences, les préférences et les préoccupations relatives à une autogestion croissante de l’avortement médicamenteux, avec une moindre participation des professionnels de santé. Nous nous sommes concentrés sur la recherche qualitative, depuis de multiples perspectives, sur la manière dont les femmes ont vécu l’autogestion d’un avortement médicamenteux du premier trimestre (< 12 semaines) de gestation. Nous avons inclus la recherche portant sur des environnements légaux et juridiquement restrictifs, que l’avortement médicamenteux ait été obtenu par des systèmes formels ou informels. Une équipe de quatre personnes a sélectionné 36 études réunissant les critères d’inclusion, en a extrait des données et rédigé un projet de synthèse. Les résultats ont été organisés d’après les thèmes suivants : perceptions générales de l’autogestion, préparation à l’autogestion, considérations logistiques, questions de choix et contrôle, et signification et expérience. La synthèse montre que la base de données qualitative est encore mince, mais que ces informations indiquent une acceptabilité globale de l’auto-administration. Nous soulignons des points particuliers à prendre en compte lors de l’application des options d’autogestion, et nous identifions des domaines clés pour de futures recherches. Il faut poursuivre les recherches qualitatives pour étoffer cette base de données importante.

Resumen

El aborto con medicamentos es un método de interrupción del embarazo que por su naturaleza permite una participación más activa de las mujeres en el proceso de manejar, y en algunos casos incluso administrar los medicamentos, para su aborto. Esta síntesis de evidencia cualitativa revisó la evidencia mundial de experiencias, preferencias e inquietudes relacionadas con mayor automanejo del aborto con medicamentos y menos participación de profesionales de la salud. Nos enfocamos en investigaciones cualitativas, desde múltiples puntos de vista sobre las experiencias de las mujeres con el automanejo del aborto con medicamentos en el primer trimestre de embarazos (< 12 semanas) de gestación. Incluimos investigaciones de contextos donde es legal y donde es restringido por la ley, ya sea que los servicios de aborto con medicamentos hayan sido accedidos por medio de sistemas formales o informales. Un equipo de revisión integrado por cuatro personas identificó 36 estudios que reunían los criterios de inclusión, extrajó datos de estos estudios y redactó los hallazgos de la revisión sintetizada. Los hallazgos fueron organizados bajo las siguientes temáticas: percepciones generales del automanejo, preparación para el automanejo, consideraciones logísticas, asuntos de elección y control, y significado y experiencia. La síntesis destaca que la base de evidencia cualitativa aún es pequeña, pero que la evidencia existente indica la aceptación general de la autoadministración. Destacamos asuntos específicos que deben ser considerados al aplicar las opciones de automanejo, e identificamos áreas clave para futuras investigaciones. Se necesitan más investigaciones cualitativas para fortalecer esta importante base de evidencia.

Introduction and Background

Medical abortion (MA) is a method of pregnancy termination that enables more active involvement of women in the process of managing, and sometimes even administering the medication for, their abortions. We define self-management as the overall management of the medical abortion process when one or more aspects of the process occurs outside of a clinical context. We also use the term self-administration to refer to a specific aspect of self-management, the act of taking the medication (mifepristone, misoprostol – also known as Cytotec – or both) outside a clinical context without clinical supervision. Enabling women’s greater self-management of their abortions is one way of improving access to safe abortion by lessening demand on the health system, and by overcoming geographical and financial barriers to accessing health facilities. However, concerns remain around what forms of self-management are safe, effective, feasible and acceptable. In relation to feasibility and acceptability, this qualitative evidence synthesis (also known as a systematic review of qualitative research) reviewed the global evidence on experiences with, preferences for, and concerns about greater self-management of medical abortion with lesser health professional involvement. The aim of the paper is to synthesize the global evidence on self-management.

Existing protocols for medical abortion – and the options for self-management in the protocol – vary widely. In the majority of settings described in the qualitative literature we reviewed, where abortion was being legally-provided, the organization of medical abortion care was rooted in a medicalized, three-clinic-visit model: a first visit to initiate the abortion process, receive counselling and take mifepristone, a second visit generally two days later to take or be given misoprostol, and a follow-up visit 1-2 weeks later to confirm completion of the abortion. Current WHO guidelines for medical abortion offer guidance for enabling women to take mifepristone at the clinic and receive misoprostol from a healthcare provider to self-administer at home, assuming that appropriate counselling is provided, and follow-up and emergency care are accessible. However, the three-clinic-visit model is the dominant model in highly medicalized settings.Citation1

We draw on a “medicalization” frameworkCitation2,3 to describe the spectrum of approaches to the management of medical abortion ranging from most medicalized to least medicalized. Shifts towards less medicalized care can include: the administration of misoprostol in clinic but the option for women to be discharged to manage the process of expulsion at home;Citation4,5 the option to self-administer misoprostol at home after the clinical administration of mifepristone;Citation6,7 the option to administer both misoprostol and mifepristone at home; and replacing follow-up with remote monitoring/self-assessment of abortion completion, for example via mobile phones,Citation8 or the independent use of self-assessment cards and pregnancy tests.Citation9,10

In this review, we focused exclusively on first-trimester medical abortion. Although the cut-off between first trimester and second trimester medical abortion is somewhat arbitrary, it is a politically, experientially and medically important distinction. As second trimester medical abortion implies both changes in the route, timing and dosage of the medicationCitation11 and increased risk associated with gestational age, women may have additional needs for professional and mentoring support.Citation12

This synthesis was one of several carried out to inform the 2015 World Health Organization guideline entitled “Health Worker Roles in Providing Safe Abortion Care.”Citation12 The guideline acknowledges that, “…it is possible for women to play a role in managing some of the components by themselves outside of a health-care facility”Citation12 and centres them as important actors in their medical abortions.

Methods

Search Strategy

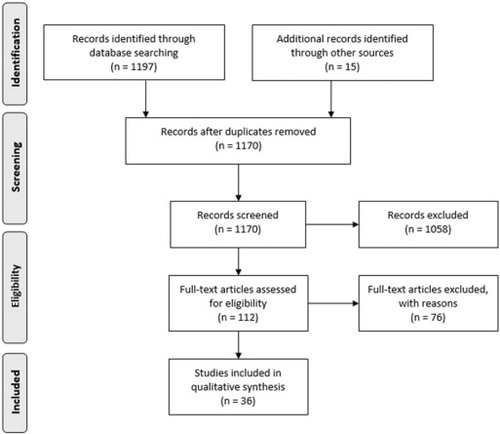

We searched the following electronic databases for eligible studies: MEDLINE, CINAHL Plus, WHO Global Health Library, Global Health and Popline. Bibliographies and grey literature were also searched. The original search for the WHO guidelineCitation12 was up to June 23, 2014. For publication, we updated our searches through to October 27, 2015. The flow diagram () represents the search and inclusion (combining original and updated searches). We considered studies in English, Spanish, Portuguese, and French for inclusion.

Study Selection

Our primary inclusion criteria were that the study report either on the experiences of women self-managing their medical abortions in some way or on perspectives (current or future) about self-management. We included studies reporting the perspectives of women, their partners, family members, health professionals, programme managers or policymakers. As is common in qualitative evidence synthesis, our inclusion and exclusion criteria were revised as we read through all the abstracts and reached consensus on the criteria.Citation13 At the start of the selection process, the four authors independently assessed the first 200 abstracts. They then discussed the studies selected for inclusion and clarified the inclusion criteria. MW then reviewed all the abstracts and AS and NL each reviewed half the abstracts, ensuring all abstracts were screened by two reviewers. Full texts of papers identified as “potentially relevant” were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. Inclusion criteria were revised and clarified throughout this stage in response to the emerging evidence.

A key decision was the inclusion of data from settings where abortion was legally-restricted, deemed as “indirectly relevant”. According to Lewin et al, “the evidence supporting a review finding may be indirectly relevant if one of the review domains above, such as perspective or setting, has been substituted with another”.Citation14 In this case, evidence from settings where abortion is legal was supplemented by evidence from legally-restricted settings. Although indirectly relevant evidence may pose a threat to our confidence in a review finding (see CERQual approach in Lewin et al), we decided there could be important insights into women’s self-management of abortions at home from experiences in legally-restricted settings. This decision also increased the geographical spread of the included studies.

Studies from settings where abortion is legal had to meet four criteria for inclusion: qualitative methodology, first trimester (< 12 weeks) medical abortion (mifepristone and misoprostol or misoprostol-only), a shift to a less medicalized process as outlined in the introduction, and data specific to self-management. We included studies using qualitative methods for data collection and analysis as well as mixed-methods studies, provided the qualitative component met the above criteria.

Studies from settings where abortion is legally-restricted often did not specify the stage of pregnancy and frequently drew from experiences of informal care networks that may or may not have included health professionals. Inclusion of such studies was based therefore on qualitative design/method/analysis, and on reporting data pertaining specifically to the experience of managing an abortion at home and/or administering the medication without the presence of a healthcare professional. Studies that reported on general experiences of abortion without data on some dimension of self-management were excluded.

Colleagues with expertise in abortion research (see acknowledgements) reviewed our list of included studies to help ensure important studies were not missed. One article in press was identified and included. Of the studies meeting our inclusion criteria, five were in Portuguese and the remainder were in English.

Data extraction and management

For data extraction, we developed an initial framework organized around four areas: a) technical knowledge/comprehension/communication, b) motivations/acceptability of home use (attitudinal aspects), c) process/logistics/steps/feasibility, d) subjective experience/feelings/inter-personal context (including provider views of women's experiences). All four authors independently extracted data from five studies. After discussion and consensus on the data extraction framework and approach, MW extracted the remaining data.

Data synthesis and CERQual

We synthesized data using thematic analysis, one of several approaches recommended by the Cochrane Qualitative Review Methods Group.Citation15 After data extraction, MW and CC identified four key thematic areas and each took data from two thematic areas and drafted initial review findings. These were then discussed and refined, with a focus on clarifying findings, supporting them with data and distinguishing them from each other. A second round of synthesis resulted in grouping review findings related to “issues of choice and control” as a fifth key thematic area. MW drafted a narrative that expanded on these key findings and all authors revised the final synthesis.

In cases where local contextual factors, such as legality of abortion, affected the finding, we make note of this. When specific local context is not mentioned in the finding, it is because we believe the finding is substantially similar across settings.

We applied the GRADE-CERQual (Confidence of the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research) to reach an overall assessment of confidence of either high, moderate, low or very low for each review finding (a summary of our findings, including CERQual assessments, can be found at: http://www.publichealth.uct.ac.za/phfm_publications-sbs). Note that CERQual is not an approach for assessing quality of individual studies or the quality of the overall synthesis.Citation14 It is a process for making judgements about our confidence in each individual review finding.

Findings

A total of 36 studies met our inclusion criteria (Table 1). Nineteen (19) studies were conducted in settings where abortion is legalized, 14 studies in legally-restricted settings, and three studies were multi-country studies with evidence from legal and legally-restricted settings. In legal settings, we found that the older studies described more medicalized approaches that required women to remain in clinic for four hours following misoprostol administration.Citation16,17 Shifts to less medicalized care in the more recent studies took the following forms: administering the misoprostol to women at the second appointment but then sending them home to abort,Citation18–20,4 giving women misoprostol at the second appointment but allowing them to self-administer it at home,Citation18,21 giving women misoprostol at the first appointment to be self-administered at home,Citation19,22–27 and giving women both mifepristone and misoprostol at the first appointment to be taken at home.Citation27,28 The studies from legal settings that reported misoprostol-only abortions reported self-administration at home.Citation29,30 In the findings we use self-administration when it pertains to taking the medication at home without direct medical supervision. When the finding is not specific to taking the medication, but about other or more general aspects of the abortion process, we use the term self-management.

Table 1 Description of included studies grouped by legal setting.

General perceptions of self-management of medical abortion

Providers were generally approving of the concept of self-management, including self-administration if initiation of medical abortion was supported by trained providers, and they believed that it could be done feasibly, effectively and safely.Citation16–19,25,27–32 Even in restricted contexts, some offered support for women self-administering, by providing clinical advice and counselling and noting likely sources of the drug. Providers were not, however, generally supportive of over-the-counter access to medical abortion drugs.Citation33–36 Self-management and self-administration allowed providers in restricted contexts to distance themselves legally from the abortion.Citation37,38 Providers in legal contexts could accomplish a similar kind of distancing on moral grounds.Citation17

Women were also generally approving of the concept of self-management. They often reported some degree of anxiety at the beginning of the process but reported relief at the end and a strong sense of satisfaction with the choice to self-manage.Citation19,20,22,23,29 In some contexts, the use of misoprostol at home for early medical abortion falls within existing interpretive frameworks and practices (such as “menstrual regulation” (Bangladesh) and was understood as one of many treatments for local illness categories referring to missed menstrual periods (e.g. “late menses” in Brazil).Citation32,35,36,39 Women in settings where there is little formal public information about abortion (whether in legal or legally-restricted settings), can sometimes be confused about the distinction between misoprostol for medical abortion, emergency contraception and oral contraceptives.Citation36,38

Women's perceptions of the acceptability of self-management without in-person contact with health professionals depended on: the standard of care and their prior experiences with medical abortion, local notions of professional medical hierarchy, abortion taboos and stigma, and perceptions around the strength, danger and complexity of the drugs.Citation20,32,40,41

Providers’ perceptions about which healthcare workers should be able to provide medical abortion drugs to women for self-administration varied and depended on: perceptions of the strength of the drugs and hence the expertise in anatomy and physiology needed to explain their full effects; a provider’s training in appropriate counselling for abortion; a provider’s knowledge of abortion-friendly emergency departments to refer women to in the case of complications; and the client’s experience, and therefore trust, of different healthcare workers.Citation16,33,42

Preparation for self-management

In preparing for self-management of medical abortion, women reported anxiety, uncertainty, or ambivalence, sometimes to do with the decision to terminate the pregnancy, but more often in relation to the process and experience of the medical abortion.Citation19,20,22,23,29,39,43,44 Effective counselling by trained providers during the first step of medical abortion that offered women a sense of confidence, being prepared, having a choice, and being in control, was important in building the acceptability of self-management among women.Citation17,22–24,44 Women and providers both felt that critical aspects of the educational component of counselling included preparing women for possible side effects and complications. Critical psychosocial components of counselling included: preparing women for the variability in individual women's physical experiences of medical abortion; the practical and physical difficulties of managing the expulsion process at home; and the fact that most women reported anxiety during the beginning of the medical abortion process but relief at its completion.Citation20,22,23,30,33,36 Providing adequate counselling in the context of health facilities was, however, seen as time consuming for health professionals and written materials for patients were reported to be underutilized.Citation19,22,29,33,34

We also derived a number of insights from evidence in both restricted and legal contexts where women self-administer misoprostol through informal networks. Women seek advice from a range of sources: friends, family, older women, websites, hotlines, pharmacists, informal sellers and sometimes even GPs without expertise in abortion. However, the information they receive can be inconsistent and/or inadequate and can lead to: variability in dosage, route and intervals; women not knowing what to expect; not trusting the quality of the medication; not knowing the duration of the process; being afraid of dying; and not knowing in which situations to seek help. Help may be sought prematurely when bleeding begins for fear of haemorrhage, or it can be dangerously delayed resulting in complications that require tertiary level care.Citation21,27,30,31,36,37,39,41,44–49 Recent studies indicate that women in settings where abortion is legally-restricted can access dependable and clear information from reputable hotlines and websites, when available.Citation40,44

Logistical considerations

Women were drawn to self-management including self-administration for a number of practical reasons including lower costs, ease of scheduling, reduced transportation needs, ability to manage stigma, and being able to terminate the pregnancy earlier. In general, women found efforts to reduce the logistical demands of medical abortion via telemedicine and website and hotline-based forms of counselling to be acceptable and to support privacy and de-stigmatization. A few women, however, noted that they preferred more direct engagement with trained providers and the clinic context for similar reasons of privacy, ease and security.Citation18,20,25,30,37,40,42,44,50

Women who self-administered or would have liked to, valued the sense of control over the process, the timing of the onset of symptoms (in contrast to being anxious about symptoms starting on the way home from clinic), the ability to plan for bleeding around work and caring duties, and the ability to maximize comfort and make arrangements to be accompanied or, in fewer cases, choose to be alone with telephone support.Citation4,21–23,44 When women were counselled by trained providers in the self-administration of misoprostol, providers trusted women’s ability to comply with dosage and timing requirements, women felt confident and reported uncomplicated abortions for the most part, and women called hotlines or consulted providers when the abortion process did not proceed as expected.Citation19,21,26,28,32–34,37,44,50

Although less commonly reported, concerns regarding the process of prescribing misoprostol for self-administration at home included not keeping oral misoprostol in one’s cheek long enough, developing abrasions, feeling nauseous from the taste of misoprostol, taking the misoprostol earlier than indicated, having difficulty administering the misoprostol vaginally and worrying about whether the medication was taken properly.Citation19,29,44 There were also reports of misunderstandings and inconsistencies regarding the prescription and use of painkillers as part of the counselling for home use, including staff not providing pain medication, or women not taking them because of fear that it would stop the abortion process or the belief that the misoprostol pill contained its own painkiller.Citation18,44

Issues of choice and control

Numerous social, economic and cultural factors, including concerns around privacy, cost, convenience, comfort and perceptions of medical care, affected the degree to which self-administration of misoprostol was the preferred method of abortion for individual women. Women expressed a desire to be able to choose the method of abortion that fit their context and circumstances.Citation20,29,41,42,44 Having the choice to self-administer medication at home (versus having it in clinic), may be an important element of acceptability of medical abortion for women.Citation4,20,23,25,43

There were some concerns among women and providers, with respect to women's autonomy over their sexual and reproductive health decision-making, around the potential unintended consequences of increasing access to medical abortion through self-management and self-administration. Specifically, there were concerns that increased access to misoprostol, especially via pharmacists, with or without prescription, could increase men's, and mothers’ involvement in and control over abortion – either in a restrictive or a coercive fashion – and increase pressure for sex-selective abortions.Citation26,30,33,42,49 Again, while providers were optimistic that having the choice to self-administer could help increase access to abortion services for younger women, whose age often represented a barrier to access, some older women were concerned that increasing access would incentivise the use of abortion as a form of routine family planning for younger women.Citation22,42

Pharmacists were commonly drawn upon for information about pregnancy termination, but in contexts where abortion is legally-restricted, pharmacists feared legal repercussions. Nonetheless, some took the risk and counselled women (often based on inadequate training and knowledge) about how to take misoprostol and what to expect, and in some cases even distributed misoprostol.Citation28,33,36,47 There was distrust, however, among women and providers in pharmacists’ ability to properly counsel and administer medical abortion. Distrust arose from a perception of pharmacists as business people, as not holding adequate knowledge, and of being incapable or uninterested in providing follow-up in the case of complications. Distrust also stemmed from a sense that pharmacies and pharmacists were poorly regulated and controlled, thus augmenting the potential for unequal treatment options/prices for clients and counterfeit or poor quality/“weak” drugs.Citation19,20,28,32,33,36,42,47

Cost was an important factor shaping choices for self-management from the perspective of both women themselves and physicians and pharmacists.Citation18,28,30,31 To save costs, some women went directly to a pharmacist without going to the physician first, and some chose to use only misoprostol (instead of misoprostol and mifepristone).Citation28,30 Pharmacists also reported making judgments about the purchasing power of their clients when recommending treatments to end pregnancy.Citation28

Meaning and experience

The evidence showed that self-management allowed for a new range of meanings and experiences of abortion to emerge, increasing the acceptability of self-management. These included the sense that it is more “natural” (more like a period or miscarriage), less about “killing”, less clinical/medicalized, allows one to be more “in control”, and allows for grief and other alternative moral interpretations and emotional experiences.Citation17,22–24,35,39,43,44

Self-management with self-administration also increased the opportunities for partners to be involved in supporting women through their medical abortions at home. However, both men and women expressed a desire for more counselling of partners about the process of medical abortion itself (e.g., what to expect with respect to pain, bleeding, side effects, length of the process) and what role they could play in supporting their partners.Citation24,26,27,40,44

Having an abortion at home also meant greater direct contact with the products of conception as they are expelled and the evidence describes different levels of comfort dealing with them. Many were curious to see, some worried about what they would see, while others held the products of conception and inspected them more closely. Comfort with seeing these products depended on the individual as well as the cultural context.Citation17,20,23

Discussion

Consistent with quantitative findings,Citation2 while most women describing their experiences with medical abortion in legal settings reported a strong sense of satisfaction with the choice to self-manage, some expressed a desire for more medicalized care. Reasons included insecurities around proper administration of the medication, convenience, ability to manage complications, having support during the process, and maintaining privacy. The concept of “privacy” is a good example of the cultural specificity of some of these findings. Similarly, “convenience” depends on how the woman perceives the differences between her home and the clinic and these differences affect what seems most comfortable. For example, women and partners in Sweden reported valuing the choice to be home for the privacy, quiet, security and comfort it offered.Citation23,24 In a study of rural Indian women, however, even though being able to stay home could help maintain privacy (by preventing neighbours from seeing one go back and forth to hospital), most were opposed to taking misoprostol at home. They were concerned about not having the appropriate facilities, having no place to lie down, and the added burden of having to continue daily household chores for others in the family.Citation42 Where possible, women should have the ability to choose different options for medical abortion and different degrees of self-managementCitation1 as suits their setting and preferences.

Synthesizing the experiences and perceptions around self-management in legally-restricted and unrestricted contexts demonstrated the key role informed counselling plays in ensuring both medical abortion’s proper use and women’s confidence. Harm-reduction programmes have shown that providing adequate counselling is possible even in restricted contexts.Citation34,50 One interesting intervention in a legally-restricted setting took the approach that it was a health professional’s duty to tell women what their options are when faced with an unwanted pregnancy, and one of those options is to obtain misoprostol on the black market.Citation34 The intervention included: consulting women on the availability of misoprostol on the black market, what to look out for when buying the medication, how to take the medication if they decided on that option, and scheduling a follow-up appointment. As counselling programmes in restricted settings have to prepare women for self-management including self-administration (and frequently self-assessment), their approaches provide important insights for programme planners in legal settings working towards less medicalized abortion services. Based on evidence from legal and legally-restricted settings, our recommendation is that counselling and support to women considering self-management should include instructions and information regarding: 1) the fact that medical abortion should not be confused with emergency or oral contraception, 2) how to take the medication, including dosage, timing and how to actually administer the drug vaginally or orally, 3) what to expect after taking the medication, including the wide degree of variability of physical experiences of medical abortion as well as possible psychological experiences, 4) possible side effects and how to deal with these, 5) how to plan for the management of the expulsion process at home, 6) if and when to take pain killers, which painkillers to take, and where these can be obtained, and 7) how to recognise in which situations to seek help.

With regards to managing the expulsion process, one guideline recommends that women receive guidance on what they can do with the products of conception and one option should be bringing the tissue back to the health centre for disposal.51 Dealing with the products of conception is an important experiential element of self-management of medical abortion, and one that is not well reported on in the qualitative literature. This may be a sensitive area for women, and therefore research designs should include space and time for researchers to build rapport and trust with their participants in order to explore this issue. Understanding women’s practices, and preferences regarding the expelled products is important especially as this is likely to vary not just culturally but also in relation to gestational age of the foetus. These differences may make it more or less easy for women to describe the appearance of their bleeding and identify the passing of the foetus, as well as shape their preferences for what to do with the products of conception.

Counselling, whether in restricted or unrestricted contexts, should also be provided for the person(s) who may be supporting the woman during her abortion at home, in particular, for women’s partners. An important future research question is how the expectations, levels of comfort and confidence of partners or other supporters, shape the woman’s experience and the process of self-management. This question may be particularly important in contexts where men’s anxiety about the levels of pain or bleeding cause them to insist that their partners seek healthcare. However, considerations around partners’ needs also must be balanced against the possibility that men’s involvement could lead to restrictions or coercion in relation to abortion. A Brazilian study described a criminal case where a man had inserted misoprostol into his pregnant partner’s vagina during sex without her knowing.Citation47 On the other hand, in restricted contexts, men often play an important role in procuring the misoprostol for their partners from the pharmacy since they are likely to be asked fewer questions by pharmacists (the medication is also prescribed for ulcers – more common among men).

As the standard of care has moved significantly towards self-management of not only misoprostol but also of mifepristone,Citation52 more qualitative research is needed on the experience of these less medicalized forms of service provision. For example, a qualitative study of innovations in places such as Australia where combination packs of mifepristone and misoprostol are available to be prescribed by physicians and dispensed at pharmaciesCitation53 would add to this limited body of evidence.Citation27,28 Furthermore, in settings where women may not be aware of medical abortion, they may or may not be offered it as a choice, depending on local providers’ own ideas regarding eligibility, appropriateness and risk. Understanding these implicit and explicit reasons for giving some women the option to administer at home, and others not, is important because individual practitioners may be assessing “eligibility” by their own implicit criteria, in turn limiting the options for certain women (for example, rural women).

Limitations of the review

The main limitations of this review is the variability of models of care for medical abortion across different settings. Another limitation is the fact that self-management was rarely the primary topic of interest of the included studies and as such, the data pertaining to self-management was relatively thin. This could be because issues related to self-management were not explored with research participants as thoroughly as they could have been, or because they were not reported on as much as they could have been. It was also difficult to tell from the qualitative literature whether differences in experience were related to different models of self-management, and how access to mifepristone-misoprostol abortion, vs. misoprostol-only abortion might have influenced the experience.

Conclusion

The overall acceptability and feasibility of self-management of medical abortion is supported by the qualitative evidence. However, in conducting this qualitative evidence synthesis we have identified that, from a global perspective, more qualitative research on self-management is needed. Research is needed on all aspects of the self-management process (e.g., self-administration, managing expulsion, assessing termination, following up if needed, etc.), as services move to less-medicalized programmes. Our findings highlight what, according to current qualitative evidence, have been the shifts towards less medicalized medical abortion and the experiences, preferences and concerns arising from these shifts. It makes the point that evidence from legal and legally-restricted settings provides relevant insights in this regard.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Debbie Constant, Jane Harries and Bela Ganatra for reviewing our list of included studies and for providing feedback. Thank you to Kim Tapscott for her assistance, and Kristen Daskilewicz for her feedback. The review was undertaken as part of a series of evidence syntheses for the development of the guidelines on “Health worker roles in providing safe abortion care” developed by the Department of Reproductive Health and Research, WHO. The support of the Department is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- E. Chong, L.J. Frye, J. Castle. A prospective, non-randomized study of home use of mifepristone for medical abortion in the U.S. Contraception. 92(3): 2015; 215–219.

- K. Iyengar, M. Klingberg-Allvin, S.D. Iyengar. Home use of misoprostol for early medical abortion in a low resource setting: secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 95: 2016; 173–181.

- E.G. Raymond, D. Grossman, E. Wiebe. Reaching women where they are: eliminating the initial in-person medical abortion visit. Contraception. 92(3): 2015; 190–193.

- P.A. Lohr, J. Wade, L. Riley. Women's opinions on the home management of early medical abortion in the UK. The Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care. 36(1): 2010; 21–25.

- S. Cameron, A. Glasier, H. Dewart. Women’s experiences of the final stage of early medical abortion at home: results of a pilot survey. The Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care. 36(4): 2010; 213–216.

- K.S. Louie, E. Chong, T. Tsereteli. The introduction of first trimester medical abortion in Armenia. Reproductive Health Matters. 22(44 Suppl.1): 2015; 56–66.

- A. Shrestha, L.B. Sedhai. A randomized trial of hospital vs home self-administration of vaginal misoprostol for medical abortion. Kathmandu University Medical Journal. 12(47): 2014; 185–189.

- D. Constant, K. de Tolly, J. Harries. Assessment of completion of early medical abortion using a text questionnaire on mobile phones compared to a self-administered paper questionnaire among women attending four clinics, Cape Town, South Africa. Reproductive Health Matters. 22(44 Suppl 1): 2015; 83–93.

- M. Puri, S. Regmi, A. Tamang. Road map to scaling-up: translating operations research study’s results into actions for expanding medical abortion services in rural health facilities in Nepal. Health Research, Policy and Systems. 12(24): 2014; 1–7.

- N.S. Whaley, A.E. Burke. Update on medical abortion: simplifying the process for women. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 27(6): 2015; 476–481.

- World Health Organization. Safe abortion: technical and policy guidance for health systems [Internet]. WHO. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/70914/1/9789241548434_eng.pdf

- World Health Organization. Health worker roles in providing safe abortion care and post abortion contraception [Internet]. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/181041/1/9789241549264_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1. 2015

- C.J. Colvin, J. de Heer, L. Winterton. A systematic review of qualitative evidence on barriers and facilitators to the implementation of task-shifting in midwifery services. Midwifery. 29(10): 2015; 1211–1221.

- S. Lewin, C. Glenton, H. Munthe-Kaas. Using qualitative evidence in decision making for health and social interventions: An approach to assess confidence in findings from qualitative evidence syntheses (GRADE-CERQual). PLoS Medicine. 2015

- J. Noyes, S. Lewin, J. Noyes. Chapter 6: Supplemental Guidance on Selecting a Method of Qualitative Evidence Synthesis, and Integrating Qualitative Evidence with Cochrane Intervention Reviews. Supplementary Guidance for Inclusion of Qualitative Research in Cochrane Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 1 (updated August 2011): Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group. 2011

- C. Ellertson, W. Simonds, B. Winikoff. Providing mifepristone-misoprostol medical abortion: The view from the clinic. Journal of the American Medical Women's Association. 54(2): 1999. 91-6 (+ 102).

- W. Simonds, C. Ellertson, K. Springer. Abortion, revised: Participants in the U.S. clinical trials evaluate mifepristone. Social Science and Medicine. 46(10): 1998; 1313–1323.

- R. Acharya, S. Kalyanwala. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of certified providers of medical abortion: Evidence from Bihar and Maharashtra, India. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 118: 2012; S40–S46.

- A. Alam, H. Bracken, H.B. Johnston. Acceptability and feasibility of mifepristone-misoprostol for menstrual regulation in Bangladesh. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 39(2): 2013; 79–87.

- B. Ganatra, S. Kalyanwala, B. Elul. Understanding women's experiences with medical abortion: In-depth interviews with women in two Indian clinics. Global Public Health. 5(4): 2010; 335–347.

- B. Elul, E. Pearlman, A. Sorhaindo. In-depth interviews with medical abortion clients: Thoughts on the method and home administration of misoprostol. Journal of the American Medical Women's Association. 55(3): 2000; 169–172.

- S.L. Fielding, E. Edmunds, E.A. Schaff. Having an abortion using mifepristone and home misoprostol: A qualitative analysis of women's experiences. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 34(1): 2002; 34–40.

- A. Kero, M. Wulff, A. Lalos. Home abortion implies radical changes for women. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care. 14(5): 2009; 324–333.

- A. Kero, A. Lalos, M. Wulff. Home abortion – experiences of male involvement. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care. 15: 2010; 264–270.

- K. Grindlay, K. Lane, D. Grossman. Women's and providers' experiences with medical abortion provided through telemedicine: A qualitative study. Women's Health Issues. 23(2): 2013; e117–e122.

- M. Makenzius, T. Tyden, E. Darj. Autonomy and dependence – experiences of home abortion, contraception and prevention. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 27: 2012; 569–579.

- P.H. Petitet, L. Ith, M. Cockroft. Towards safe abortion access: an exploratory study of medical abortion in Cambodia. Reproductive Health Matters. Suppl(44)(55): 2015; 47.

- B. Ganatra, M. Vinoj, P.S. Prasad. Medical abortion in Bihar and Jharkhand. 2005; IPAS: New Delhi, India.

- E.M.H. Mitchell, A. Kwizera, M. Usta. Choosing early pregnancy termination methods in Urban Mozambique. Social Science & Medicine. 71: 2010; 62–70.

- P. Nanda, A. Barva, S. Dalvie. Exploring the transformative potential of medical abortion for women in India. 2010; International Center for Research on Women: New Delhi, India.

- H. Espinoza, K. Abuabara, C. Ellertson. Physicians' knowledge and opinions about medication abortion in four Latin American and Caribbean region countries. Contraception. 70: 2004; 127–133.

- G. Pheterson, Y. Azize. Abortion practice in the Northeast Caribbean: “Just write down stomach pain”. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(26): 2005; 44–53.

- J. Cohen, O. Ortiz, S.E. Llaguno. Reaching women with instructions on misoprostol use in a Latin American country. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(26): 2005; 84–92.

- V. Fiol, L. Briozzo, A. Labandera. Improving care of women at risk of unsafe abortion: Implementing a risk-reduction model at the Uruguayan-Brazilian border. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 118: 2012. S21-S27.

- M.K. Nations, C. Misago, W. Fonseca. Women's hidden transcripts about abortion in Brazil. Social Science and Medicine. 44(12): 1997; 1833–1845.

- J. Sherris, A. Bingham, M.A. Burns. Misoprostol use in developing countries: Results from a multicountry study. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 88: 2005; 76–81.

- M.M. Arilha. Misoprostol: percursos, mediacoes e redes sociais para o acesso ao aborto medicamentoso em contextos de ilegalidade no Estado de Sao Paulo. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 17(7): 2012; 1785–1794.

- L. Bury, S.A. Bruch, X.M. Barbery. Hidden realities: What women do when they want to terminate an unwanted pregnancy in Bolivia. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 118: 2012; S4–S9.

- D. Grossman, K. Holt, M. Pena. Self-induction of abortion among women in the United States. Reproductive Health Matters. 18(36): 2010; 136–146.

- R.I. Drovetta. Safe abortion information hotlines: an effective strategy for increasing women's access to safe abortions in Latin America. Reproductive Health Matters. 23(45): 2015; 47–57.

- J.D. Gipson, A.E. Hirz, J.L. Avila. Perceptions and practices of illegal abortion among urban young adults in the Philippines: A qualitative study. Studies in Family Planning. 42(4): 2011; 261–272.

- B. Subha Sri, T.K. Sundari Ravindran. Medical abortion: Understanding perspectives of rural and marginalized women from rural South India. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 118: 2012; S33–S39.

- S.M. Harvey, L.J. Beckman, M.R. Branch. The relationship of contextual factors to women's perceptions of medical abortion. Health Care for Women International. 23: 2002; 654–665.

- S. Ramos, M. Romero, L. Aizenberg. Women's experiences with the use of medical abortion in a legally restricted context: the case of Argentina. Reproductive Health Matters. Suppl(43): 2015; 1–12.

- R.M. Barbosa, M. Arilha. A experencia brasileira com o cytotec. Estudos Feministas. 2(93): 1993; 408–417.

- R.M. Barbosa, M. Arilha. The Brazilian experience with Cytotec. Studies in Family Planning. 24(4): 1993; 236–240.

- D. Diniz, A. Madeiro. Cytotec e aborto: A policia, os vendedores e as mulheres. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 17(7): 2012; 1795–1804.

- Z.C. Silva do Nascimento Souza, N.M. Freire Diniz, T. Menezes Couto. Trajectoria de mulheres em situacao de aborto provocado no discurso sobre clandestinidade. Acta Paulista de Enfermagem. 23(6): 2010; 732–736.

- L.M. Vallely, P. Homiehombo, A. Kelly-Hanku. Unsafe abortion requiring hospital admission in the Eastern Highlands of Papua New Guinea – a descriptive study of women's and health care workers' experiences. Reproductive Health. 12(22): 2015; 1–11.

- D. Grossman. Evaluation of a harm-reduction model of service delivery for women with unintended pregnancies in Peru. 2013; Ibis Reproductive Health: Oakland, CA, USA.

- Bpas. Clinical Guidelines: Early Medical Abortion. 2015; Bpas: Warwickshire, UK.

- M. Gold, E. Chong. If we can do it for misoprostol, why not for mifepristone? The case for taking mifepristone out of the office in medical abortion. Contraception. 92(3): 2015; 194–196.

- D. Grossman, P. Goldstone. Mifepristone by prescription: a dream in the United States but reality in Australia. Contraception. 92(3): 2015; 186–189.