Abstract

Despite increasing awareness of the importance of sexuality for older adults, research and popular literature rarely acknowledge what we term “sexual bereavement” – mourning the loss of sexual intimacy when predeceased. The reluctance to acknowledge sexual bereavement may create “disenfranchised grief” leaving the bereaved unsupported in coping with this aspect of mourning. This preliminary study focuses on women in the United States and sought to determine whether they anticipate missing sex if predeceased, whether they would want to talk about this loss, and identified factors associated with communicating about sexual bereavement. Findings from our survey of 104 women, 55 years and older, most of whom were heterosexual, revealed that a large majority (72%) anticipates missing sex with their partner and 67% would want to initiate a discussion about this. An even higher percentage would want friends to initiate the topic. Yet, 57% of participants report it would not occur to them to initiate a discussion with a widowed friend about the friend’s loss. Disenfranchised grief can have negative emotional and physical consequences. This paper suggests a role for friends and professionals in addressing this neglected issue.

Resumé

En dépit d’une prise de conscience accrue de l’importance de la sexualité pour les adultes âgés, la recherche et les publications non spécialisées évoquent rarement ce que nous appelons le «deuil sexuel»: la perte de l’intimité sexuelle en cas de décès du partenaire. La réticence à reconnaître le deuil sexuel peut créer un «chagrin non reconnu» qui laisse la personne endeuillée seule pour faire face à cet aspect de la perte d’un être cher. Cette étude préliminaire, axée sur les femmes aux États-Unis, souhaitait déterminer si elles pensaient que les rapports sexuels leur manqueraient si leur conjoint venait à décéder avant elles et si elles voudraient parler de cette perte. Elle a identifié des facteurs associés avec la communication sur le deuil sexuel. Notre enquête auprès de 104 femmes, âgées de 55 ans et plus, pour la plupart hétérosexuelles, a révélé qu’une vaste majorité (72%) pensaient que les rapports sexuels avec leur partenaire leur manqueraient et que 67% voudraient entamer une discussion sur ce sujet. Un pourcentage encore plus élevé d’entre elles aimeraient que les amis prennent l’initiative de cette discussion. Pourtant, 57% des participantes ont indiqué que cela ne leur viendrait pas à l’idée de commencer à parler avec une amie veuve de la perte qu’elle a subie. Le chagrin non reconnu peut avoir des conséquences physiques et émotionnelles négatives. Cet article suggère un rôle pour les amis et les professionnels afin d’aborder ce problème méconnu.

Resumen

A pesar de mayor conciencia de la importancia de la sexualidad de adultos de edad más avanzada, las investigaciones y la literatura popular rara vez reconocen lo que llamamos “duelo sexual”, es decir, llorar la pérdida de intimidad sexual cuando su pareja fallece antes. La renuencia a reconocer el duelo sexual podría crear “pena no reconocida”, lo cual deja a la persona en duelo sin apoyo para superar este aspecto del duelo. Este estudio preliminar se enfocó en las mujeres en Estados Unidos y buscó determinar si prevén echar de menos las relaciones sexuales si su pareja fallece antes que ella, si les gustaría hablar sobre esta pérdida, y se identificaron factores asociados con la comunicación sobre el duelo sexual. Los hallazgos de nuestra encuesta de 104 mujeres, de 55 años de edad y mayores, la mayoría heterosexual, revelaron que la gran mayoría (72%) prevé echar de menos tener sexo con su pareja y al 67% les gustaría iniciar una conversación al respecto. A un porcentaje aun mayor le gustaría que sus amistades inicien el tema. Sin embargo, el 57% de las participantes informan que no se les ocurriría iniciar una conversación con una amiga viuda sobre la pérdida de esa amiga. La pena no reconocida puede tener consecuencias emocionales y físicas negativas. Este artículo sugiere que amistades y profesionales pueden desempeñar un papel en abordar este asunto olvidado.

Introduction

In recent years, both the academic and popular press have increasingly acknowledged that older people are engaging in and, importantly, enjoying sex.Citation 1–3 Fortunately the field of sexual health has come a long way since 2007 when DeLamater and Moorman wrote,

If a social scientist from an alien planet wished to learn about Earthling behavior from reading our scientific research literature, she might well conclude that sexuality is not important to humans older than 50 (p.1).Citation 4

In a 2007 U.S. study, more than half (54%) of men and almost a third (31%) of women over the age of 70 reported they were still sexually active.Citation 4 It is now acknowledged that many partnered men and women well over 55 years of age consider sex an essential part of their lives, and sexuality a “critical part” of their relationship.Citation 1,5,6 A 2012 study reported that a substantial number of adults in their eighth and ninth decades consider sexual expression to be an important part of their lives.Citation 7 The end of sexuality is no longer expected as a feature of aging, and sexual activity across the lifespan is now linked to overall health. The medical community is being advised to pay more attention to a decline in sexual function as possibly symptomatic of deterioration in physical health rather than a natural consequence of aging.Citation 8

Given the aging population, a growing number of seniors will experience the death of a long-term partner and the accompanying loss of sexual and affectional activities that enrich their lives. Yet, almost no studies are looking at this loss despite a growing older population. A recent report states that 40% of women over 65 in the U.S. were widowed in 2016Citation 9 and fifty-three million people are projected to be over 65 by 2020.Citation 10 The United Nations General Assembly on Women in 2000 reported statistics on widows over 60 years of age worldwide, ranging from 34% in the Caribbean to 59% in Northern Africa. Corresponding figures for Western and Eastern Europe are 40% and 48% respectively.Citation 11

Researchers have learned that mutual coping patterns develop over time in enduring sexual relationships,Citation 12,13 however much of the focus on older women and men has been on sexual dysfunction.Citation 14–16 Although some research has focused on widows and sexuality,Citation 17,18 the topic of sexual bereavement, the grief resulting from the loss of the sexual relationship with a long-term partner, has been overlooked.Citation 19 Courtney notes that it is natural to feel the loss of the sexual relationship as much as the loss of companionship and practical help.Citation 20 However, she notes the surviving partner may be embarrassed to bring this up in counseling. It has also been documented that physicians/counselors are generally uncomfortable discussing sex with older women and men.Citation 21,22 As a result, such discussions either never happen or happen awkwardly. Sexual bereavement, as a specific aspect of bereavement, has not received adequate attention from grief counselors in their practice or training.

Grief following the death of a spouse is associated with physical symptoms, emotional distress, and sexual feelings that have been described as, “floating, unanchored and undefined.” Citation 23,24 To mitigate these consequences and to overcome isolation, the surviving partner is urged by bereavement counselors to discuss all aspects of their grief without fear of criticism.Citation 25,26 However, a culture of silence surrounds feelings of sexual bereavement following a partner’s death and these feeling are left un-validated. In silence they become disenfranchised grief – a grief that is not openly acknowledged, socially sanctioned and publicly shared.Citation 27

Best-selling memoirs about the death of a spouse that fail to mention sexual bereavement reinforce the message that raising the topic is inappropriate.Citation 28–30 Self-help books for widows also usually exclude discussions about loss of sexual intimacy with the deceased partner and the grief surrounding that loss.Citation 31,32

Seeking support and information, some widows are now turning to blogs to share their stories. The anonymity provided by these forums has allowed widows, mostly women, to raise the topic of sexual bereavement and describe their discomfort when they have tried to discuss their grief. A brief review of these blogs uncovered poignant examples of women who felt alone and isolated because they were unable to talk about it.

A single posting from a woman sarcastically stated that she was not a good widow because,

“A good widow does not crave sex. She certainly doesn’t talk about it. …Apparently, I stink at being a good widow.” Citation 33

Her post unleashed a flood of responses about sexual bereavement and the frustration of being unable to express this grief:

“I wish there were more open forums to discuss this because I think it’s a huge hurdle.” Citation 34

“Sex is one of the things that I miss the most…but it is not something that you can share with the everyday person.” Citation 35

“I have not felt at ease to talk about this to any of my family or friends... I think they don’t know how to listen to this without it becoming uncomfortable for them.” Citation 36

Little is known about how extensively sexual bereavement is experienced or what widows believe would make communication with friends and professionals easier. This study attempted to gain a better understanding of whether women anticipate missing sex if predeceased and explore factors associated with their communication about this loss.

Methods

Sample

Not knowing if sexual bereavement is of legitimate concern, this exploratory study recruited currently partnered women rather than widows because of the discomfort that might be experienced by bereaved women. The difficulty of raising the double taboo of death and sex with bereaved subjects has been previously described.Citation 23 The convenience sample, appropriate for an exploratory study in a new and sensitive area of inquiry, was selected using a snowball technique that started with a network of currently partnered women aged 55 and older. This network was known personally to the researchers who were aware that the group was predominantly Caucasian, college-educated, and middle-class residents of the Northeast United States. Most of the women were heterosexual, but the sample also included lesbian women. The core network provided addresses for women in their networks. A chain referral technique assumes the majority of women outside the core network shared the characteristics of the core. Despite its limitations, a non-random, convenience sample was used to explore whether further study with a more generalizable sample would be worthwhile.

To protect the anonymity of the respondents known to the researchers, age was the only demographic information collected on the survey. For this reason we cannot present results by race, sexual orientation or socioeconomic status. Definitions of “older person” vary. The World Health Organization defines older person as one “whose age has passed the median life expectancy at birth.” Citation 37 The U.S. Administration on Aging defines aging as 60 years and older.Citation 38 Our definition of “older” is 55 years and older, applying a slightly younger definition than generally used in the U.S. because of the study’s focus on the anticipation of sexual bereavement.

Survey instrument and response rate

Data were collected through an anonymous, mailed survey containing 19 fixed-response items and space for voluntary, open-ended comments. The instrument was mailed in November 2013 and data collection closed at the end of January 2014. Of the 158 surveys mailed, 108 were returned (68%) and 104 met the age and partnered criteria.

The authors, retired, are no longer institutionally based and fielded the survey independently following criteria for IRB approval of research established by the US Department of Health and Human Services and the ethical guidelines for the protection of human subjects established by the American Psychological Association.Citation 39,40 Participants were informed about the purpose and intended use of the findings, and participation was voluntary and anonymous. Data were reported in aggregate and participants’ comments were reported without identifying information.

Measures

Participants were instructed to define sexuality broadly with specific directions to “…apply your personal meaning of sexual relations, sexual activity, making love, etc.” Sexual bereavement was measured by responses to the following question: “If my partner died, sex: 1) would definitely be something I would miss; 2) might be something I would miss; and 3) would not be one of the things I would miss.” Questions about communication about sexuality were both general (e.g., comfort talking about sex) and specifically related to attitudes about wanting to discuss sexuality should their own partner predecease them, and raising the topic with a friend whose partner has died. The survey questions did not specify whether these friends were female or male. Questions also focused on comfort/discomfort discussing the topic. All questions about sex used the term “partner” to be inclusive of respondents who were not all heterosexual and married. The survey collected data about health because of its potential impact on sexuality in this population. Because almost all respondents described themselves and their partners as being in good or excellent health, health was not used as an independent variable in the analysis.

Analysis

Due to the exploratory nature of this research, the analysis was descriptive – frequencies and cross tabulation – rather than explanatory. Chi square tests were applied to the crosstabs and p ≤ .05 was used as the criterion for statistical significance.

Results

Thirty-seven percent of the participants were ages 55-65, 57% were 66-75, and 6% were older. A majority of participants were currently sexually active with 40% reporting they engaged in sex once a week or more, 15% every two weeks, 11% once a month and 34% less often. Eighty-six percent of all participants reported they enjoyed sex.

Almost three-quarters of participants (72%) presumed they would miss sex if their partner died, with 53% reporting they definitely would. Twenty-seven percent reported sex would not be something they would miss. Missing sex was positively and significantly correlated with frequency of sex. Women who reported having sex with their partner every two weeks or more were far more likely to say they “would definitely” miss having sex than were women who had sex once a month or less (75% vs. 26%).

Discomfort conversing about sexual bereavement

Many women reported they would want to talk about sex with friends after the death of a partner. Two-thirds (67%) of all participants indicated they would probably initiate a discussion about sex with friends, and more, 76%, said they would want friends to initiate that discussion with them. Women who reported having sex frequently were significantly more likely to say they would probably initiate a discussion if their partner died compared to women who had sex less frequently (79% vs. 54%, respectively). Similarly, women having sex more frequently were more likely to want friends to initiate a sexual bereavement discussion compared to those having sex less frequently (85% vs. 64%, respectively).

Despite the fact that participants anticipated they would want friends to initiate a discussion about sexual bereavement, more than half (57%) reported it would not occur to them to discuss sexual bereavement with a widowed woman and 34% reported that even if it did occur to them, they “would probably be too embarrassed to discuss sex with a woman friend whose partner died.” Of the participants who reported that sex would be difficult to discuss with a friend whose partner had died, 67% attributed this difficulty to embarrassment.

Of those who reported they would be too embarrassed to discuss the topic of sex, 77% answered “true” to the statement, “Regardless of the closeness of the friendship or the gender, this would be a difficult topic for me to discuss with someone whose partner has died.” While the survey questions did not specify gender of the friend, the issue of the gender was raised by three of the 104 respondents in the survey’s open-ended comments section. One wrote, “I have had two close friends who have lost partners...I, in fact, discussed sexuality with my male friend and not yet with my female friend.” Another respondent, previously widowed, wrote, “I lost my partner at the age of 43. The only friend who ever asked me about my sex life was a very good male friend.” And one woman stated, “My sense is that I can actually talk with my gay (male) friends more easily about this – I mean several have actually brought it up.”

Other open-ended comments volunteered by participants suggested more general reasons for discomfort. One participant wrote, “I would find talking about it [sex] more inappropriate than I used to...and I no longer think...it’s always ok for me to ask.” Another wrote that it would seem “odd” to raise the issue unless the widowed friend indicated “some kind of need.” Despite their hesitance to raise the topic themselves, a large majority of all participants (90%) reported that they would not be embarrassed if a woman whose partner died raised the topic of sexual bereavement with them.

Respondents who were comfortable talking about sex were significantly more likely to want a friend to initiate a discussion about sex compared to respondents who were not comfortable (88% vs. 48% respectively). Seventy-nine percent of the women who thought they would definitely miss sex said they would initiate the discussion as did 68% of those who thought they might miss sex, and 43% of the women who thought they would not miss sex if their partner died. Again, a larger percentage of participants in each group said they would want their friends to initiate the discussion – 89%, 79% and 48%, respectively.

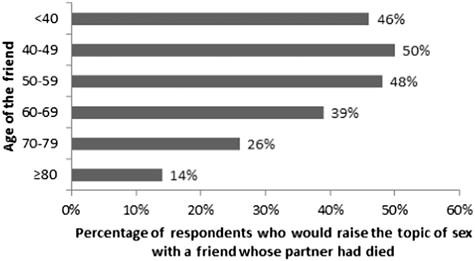

No statistically significant relationship was found between participants’ age and believing they would initiate communication about sexual bereavement or want a friend to initiate. However, while approximately half of the participants thought they would raise the issue with women under 60 whose partners had died, only 26% would raise the issue with women in their 70’s and 14% with women 80 or older ( ). No data were collected about raising the issue of sex with a male friend whose partner had died.

Figure 1. Relationship between age of friend and willingness to raise the topic of sex with a female friend whose partner had died

Most women mentioned they were comfortable talking to doctors/therapists about sex, but almost half say they never do and almost all (90%) say they do not want to talk to therapists about sex more frequently than they already do. This study did not ask participants to project whether they thought they would want to discuss sexual bereavement with a therapist.

Written comments volunteered by survey participants indicated the salience of this topic:

“The survey made me think more about its importance to those who have lost a partner…”, “This is such an important topic that is rarely discussed.”, “Thank you for raising my consciousness to these issues.”

Discussion

This study provides evidence that the partnered women surveyed, most of whom are heterosexual, expect they would miss the sexual relationship shared with their partner if predeceased. This corroborates anecdotal evidence from women on widows’ blogs about the importance of bringing attention to this issue. The bereavement literature is rich with information about navigating grief after a partner’s death, yet there has been little recognition of sexual bereavement as something to be validated in and of itself. Such unacknowledged sexual bereavement becomes disenfranchised grief – socially unacceptable and unresolved.Citation 26,27,41 The negative consequences of disenfranchised grief have been previously noted.Citation 23–25 It is possible that disenfranchised grief may be felt especially acutely by older people whose culture or sexual orientation may make discussions about sexual bereavement especially difficult. In the words of The New York Times personal health columnist, Jane Brody, “The only grief that does not end is grief that has not been fully faced.” Citation 42

Talking with friends and counselors has been shown to buffer the impact of the death of a spouse.Citation 43 Most (67%) of the women in our study believed they would want to talk with their friends about sexual bereavement. Although the survey did not specify the gender of the friend, there is reason to believe that gender might influence their desire to discuss this intimate topic. Since the 1990’s, best-selling books on gender and communication have described reasons for the difficulty men and women have communicating intimately with each other. Men are said to either withdraw or offer advice whereas women use conversation to negotiate for closeness and preserve intimacy.Citation 44,45 A blog that focuses on grief suggests that these gender differences in communication style lead women to consider their male friends unsupportive. In the opinion of the blogger, women do not want to be offered a “fix,” they want to work through their grief by confiding in friends who will allow them to express their emotions and “feel” their way through grief.Citation 46

Interestingly, more women in the current study stated a preference for having friends initiate conversations about sexual bereavement rather than initiating it themselves. Perhaps because the topic has not been generally acknowledged, even women who said they were comfortable talking about sex reported that it would not occur to them to initiate a discussion about sex if a friend’s partner died.

The inability to share aspects of grief can reduce the likelihood of receiving support.Citation 27 Talking about sexuality in older people, in general, was thought to be uncomfortable by our participants. Considering whether they would raise the issue of sexual bereavement with a “good friend” whose partner had died, some study participants said they would be embarrassed. This may be because sex is considered more normative for elderly men than elderly women.Citation 47 It has even been suggested that women might be more reluctant than men to talk openly about sex because of concern they will be judged as desiring sex. Citation 48

Implications for practice

Health professionals and counselors are in a unique position to address sexual bereavement, but will they raise this topic? While the current study did not encompass this issue, there is research that suggests that women and men find it easier to discuss sexual concerns if the clinician initiates the conversation.Citation 49 If health professionals/counselors are uncomfortable discussing sex with older women, it is unlikely the women will initiate the conversation.Citation 21,22 Although the importance of better training for health professionals who counsel older adults was raised almost 30 years ago, the need for such training still exists.Citation 20,50 The National Service Framework for Older People, published by the UK Department of Health in 2013Citation 51 makes no mention of the problems related to sexual issues older people may face. Researchers have even suggested that some healthcare professionals might share the prejudice that sex in older people is “disgusting” or “simply funny” and therefore avoid discussing sexuality with their older patients.Citation 52 In a 2003 study in England, 94% of the health care professionals (therapists, doctors and nurses) stated they were uncomfortable and unlikely to discuss sexual issues with their patients.Citation 53 Given these attitudes, it is no surprise that older patients would be reluctant to initiate discussions with counselors.Citation 54 A blog post by a widow illustrates this discomfort:

“I too find it hard to bring up while [in] counseling although I drop ‘hints.’ I am not comfortable discussing it with male counselors, and even the female ones seem to skirt the issue…” Citation 55

With appropriate awareness and training, practitioners are in a unique position to validate sexual bereavement and initiate conversations with widowed clients.

Limitations and future research

While preliminary, the findings of this exploratory study suggest that sexual bereavement is an aspect of bereavement that deserves further attention. The findings apply to a circumscribed group of women; consequently the non-random sample prevents generalizability. Further, the study sample did not include males, and because we did not know how many women in the sample defined themselves as heterosexual, lesbian or bisexual, we could not explore sexual bereavement and communication with these groups. Studies of generalizable samples of widows and widowers are needed in order to better understand the extent and nature of sexual bereavement and to learn how it may impact women and men of different ages, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and geographic locations.

Another limitation of this study is that it did not focus on gender differences in communication with friends or therapists. However, open-ended comments from a few participants who reported that they might find male friends more approachable, suggest that research on the role of gender in communication about sexual bereavement might be fruitful. In order to improve communication about sexual bereavement among friends and therapists, more needs to be known about the determinants of discomfort and embarrassment and successful strategies for raising the topic.

As noted, studies have shown that grief is frequently associated with physical and mental health issues.Citation 8 Knowing whether there is a relationship between sexual bereavement and health could be useful for improving the health and wellbeing of older adults. Similarly, the relationship between sexual bereavement and how one might experience sexuality and relationships after a death could also yield valuable information. Also, more needs to be known about whether there is anticipatory sexual bereavement when a partner has a disability or prolonged illness.Citation 56,57

Conclusion

This study is particularly timely. Baby boomers are increasing the numbers of people who will be predeceased by a partner with whom they have shared a satisfying sexual relationship. Until sexual bereavement is acknowledged as a form of disenfranchised grief, seniors may continue to navigate a significant loss in silence and without adequate support. We need to respond to the widow who wrote,

“Thank you for taking the step to raise this very emotional and tough subject. It seems very ‘taboo’ in this culture...to speak about the most profound, natural and necessary human need.” Citation 55

References

- L.L. Fisher. Sex, romance and relationships: AARP survey of midlife and older adults. 2010; AARP: Washington, DC Available from: http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/general/srr_09.pdf

- I. Krasnow. Sex after…: women share how intimacy changes as life changes. 2014; Avery: New York

- J. Delamater, S.M. Moorman. Sexual behavior in later life. Journal of Aging and Health. 19(6): 2007 Dec; 921–945. 10.1177/0898264307308342

- S.T. Lindau, L.P. Schumm, E.O. Laumann, W. Levinson, C.A. O’muircheartaigh, L.J. Waite. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine. 357(8): 2007 Aug 23; 762–774. 10.1056/NEJMoa067423

- I.B. Addis, S.K. Van Den Eeden, C.L. Wassel-Fyr, E. Vittinghoff, J.S. Brown, D.H. Thom. Sexual activity and function in middle-aged and older women. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 107(4): 2006 Apr; 755–764. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000202398.27428.e2

- M. Gott, S. Hinchliff. How important is sex in later life? The views of older people. Social Science & Medicine. 56(8): 2003 Apr; 1617–1628. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00180-6

- J. DeLamater. Sexual expression in later life: a review and synthesis. Journal of Sex Research. 49(2-3): 2012; 125–141. 10.1080/00224499.2011.603168

- B.L. Marshall. Science, medicine and virility surveillance: ‘sexy seniors’ in the pharmaceutical imagination. Sociology of Health & Illness. 32(2): 2010; 211–224. 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01211.x Epub 2010 Feb 8

- Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. Older Americans 2016: key indicators of well-being. 2016; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington (DC) Available from: http://www.agingstats.gov/docs/LatestReport/OA2016.pdf

- United States Census Bureau. Current population report. 2002; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington (DC)

- United Nations Division for the Advancement of Women. Widowhood: Invisible, Secluded, or Excluded. The World’s Women 2000: Trends and Statistics. 2000; United Nations Publications: New York

- J. DeLamater, J.S. Hyde, M.-C. Fong. Sexual satisfaction in the seventh decade of life. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 34(5): 2008; 439–454. 10.1080/00926230802156251

- K.R. Stephenson, C.M. Meston. When are sexual difficulties distressing for women? The selective protective value of intimate relationships. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 7(11): 2010 Nov; 3683–3694. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01958.x

- S. Foley. Older adults and sexual health: a review of current literature. Curr Sex Health Rep. 7(2): 2015; 70–79. 10.1007/s11930-015-0046-x

- P. Nash, P. Willis, A. Tales, T. Cryer. Sexual health and sexual activity in later life. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology. 25(01): 2015; 22–30. 10.1017/S0959259815000015

- W. Norton, P. Tremayne. Sex and the older man. The British Journal of Nursing. 24(4): 2015; 218–221. 10.12968/bjon.2015.24.4.218

- J. Kansky. Sexuality of widows: a study of the sexual practices of widows during the first fourteen months of bereavement. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 12(4): 1986; 307–321. 10.1080/00926238608415416

- V.J. Malatesta, D.L. Chambless, M. Pollack, A. Cantor. Widowhood, sexuality and aging: a life-span analysis. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 14(1): 1988; 49–62. 10.1080/009262388084039016

- A.S. Rossi. Eros and caritas: A biopsychosocial approach to human sexuality and reproduction. A.S. Rossi. Sexuality across the life course. 1994; University of Chicago Press: Chicago. 3–38.

- M. Courtney. The sexual needs of widowed people. Bereav Care. 4(1): 1985; 8–11. 10.1080/02682628508657128

- B. Elliott. Sexual needs of those whose partner has died. Bereav Care. 16(1): 1997; 2–5. 10.1080/02682629708657398

- S.A. Adams. Marital quality and older men’s and women’s comfort discussing sexual issues with a doctor. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 40(2): 2014; 123–138. 10.1080/0092623X.2012.691951 Epub 2013 Jun 14

- M.R.H. Nusbaum, A.R. Singh, A.A. Pyles. Sexual healthcare needs of women aged 65 and older. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 52(1): 2004; 117–122. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52020.x

- R.L. Utz, M. Caserta, D. Lund. Grief, depressive symptoms, and physical health among recently bereaved spouses. Gerontologist. 52(4): 2012 Aug; 460–471. 10.1093/geront/gnr110 Epub 2011 Dec 7

- C.L. Jenkins, A. Edmundson, P. Averett, I. Yoon. Older lesbians and bereavement: experiencing the loss of a partner. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 57(2-4): 2014; 273–287. 10.1080/01634372.2013.850583 Epub 2014 May 5

- A. Tracey. Perpetual loss and pervasive grief: daughters speak about the death of their mother in childhood. Bereav Care. 30(3): 2011; 17–24. 10.1080/02682621.2011.617966

- K.J. Doka. Grief is a journey: finding your path through loss. 2016; Atria Books: New York

- J. Barnes. Levels of life. 2013; Knopf: New York

- J. Didion. The year of magical thinking. 2005; Knopf: New York

- J.C. Oates. A widow’s story: a memoir. 2011; Ecco Press: New York

- C. Lightner, N. Hathaway. Giving sorrow words: how to cope with grief and get on with your life. 1990; Grand Central Publishing: New York

- J.H. McCormack. Grieving: a beginner’s guide. 2005; Darton, Longman & Todd, Ltd.: London

- T.H. Hunter. Sex, sensuality and sadness, reply [Internet]. Widow’s voice: seven widowed voices sharing love, loss, and hope. 2011; Soaring Spirits International [cited 2016Oct23]. Available from: http://widowsvoice-sslf.blogspot.com/2011/04/sex-sensuality-and-sadness_10.html

- Chris. Sex, sensuality and sadness, reply [Internet]. Widow’s voice: seven widowed voices sharing love, loss, and hope. 2011; Soaring Spirits International [cited 2016Oct23]. Available from: http://widowsvoice-sslf.blogspot.com/2011/04/sex-sensuality-and-sadness_10.html

- The Tomlin Family. Sex, sensuality and sadness, reply [Internet]. Widow’s voice: seven widowed voices sharing love, loss, and hope. 2011; Soaring Spirits International [cited 2016Oct23]. Available from: http://widowsvoice-sslf.blogspot.com/2011/04/sex-sensuality-and-sadness_10.html

- Anonymous. Lack of intimacy, reply [Internet]. Widows Speak Up!. [cited 2016Oct23]. Available from: http://www.widowsspeakup.com/2012/01/lack-of-intimacy.html 2015 Nov.

- World Health Organization. World report on ageing and health. 2015; WHO Press: Luxembourg 230.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Administration on Aging [Internet]. [cited 2016Oct23]. Available from: http://www.aoa.gov/

- Code of Federal Regulations, Title 45, Public Welfare, Department of Health and Human Services, Part 46, Protection of Human Subjects. §46.111 Criteria for IRB approval of research. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/index.html#46.111 2009.

- American Psychological Association. Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct [Internet]. [cited 2016Oct23]. Available from: http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/ 2010.

- B. McNutt, O. Yakushko. Disenfranchised grief among lesbian and gay bereaved individuals. J LGBT Issues Couns. 7(1): 2013; 87–116. 10.1080/15538605.2013.75834

- J.E. Brody. Jane Brody’s guide to the great beyond: a practical primer to help you and your loved ones prepare medically, legally, and emotionally for the end of life. 2009; Random House: New York 211.

- L.S. Kanacki, P.S. Jones, M.E. Galbraith. Social support and depression in widows and widowers. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 22(2): 1996 Feb; 39–45. 10.3928/0098-9134-19960201-11

- J. Gray. Men are from mars, women are from venus: a practical guide for improving communication and getting what you want in a relationship. 1992; HarperCollins: New York

- D. Tannen. You just don’t understand: women and men in conversation. 1990; Ballantine Books: New York

- Bekkers T. Green Bay Oncology [Internet]. Gender differences in grief. [cited 2016 Nov 1]. Available from: http://gboncology.com/blog/gender-differences-in-grief/ 2013 Oct.

- J.L. Hillman. Clinical perspectives on elderly sexuality. 2000; Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers: New York

- B. Montemurro, J. Bartasavich, L. Wintermute. Let’s (not) talk about sex: the gender of sexual discourse. Sexuality and Culture. 19(1): 2015 Mar; 139–156. 10.1007/s1219-014-9250-5

- M.R. Nusbaum, P. Lenahan, R. Sadovsky. Sexual health in aging men and women: addressing the physiologic and psychological sexual changes that occur with age. Geriatrics. 60(9): 2005 Sep; 18–23.

- V.J. Malatesta. Sexuality and the older adult: an overview with guidelines for the health care professional. Journal of Women & Aging. 1(4): 1989; 93–118. 10.1300/J074v01n04_07

- US National Institute on Aging. Sexuality in later life [Internet]. Age Page. National Institutes of Health. [cited 2016Oct23]. Available from: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/sexuality-later-life 2013.

- A. Taylor, M.A. Gosney. Sexuality in older age: essential considerations for healthcare professionals. Age and Ageing. 40(5): 2011 Sep; 538–543. 10.1093/ageing/afr049

- N.H. Haboubi, N. Lincoln. Views of health professionals on discussing sexual issues with patients. Disability and Rehabilitation. 25(6): 2003 Mar 18; 291–296. 10.1080/0963828021000031188

- E.M. Inelmen, G. Sergi, A. Girardi, A. Coin, E.D. Toffanello, F. Cardin, E. Manzato. The importance of sexual health in the elderly: breaking down barriers and taboos. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research. 24(3 Suppl): 2012 Jun; 31–34.

- Anonymous. Lack of intimacy, reply [Internet]. Widows Speak Up!. [cited 2016Oct23]. Available from: http://www.widowsspeakup.com/2012/01/lack-of-intimacy.html 2012 Jan 12.

- T.A. Rando. Anticipatory mourning: what it is and why we need to study it. T.A. Rando. Clinical dimensions of anticipatory mourning. 2000; Research Press: Champaign (IL).

- T.A. Rando, K.J. Doka, S. Fleming, M.H. Franco, E.A. Lobb, C.M. Parkes, et al. A call to the field: complicated grief in the DSM-5. Omega (Westport). 65(4): 2012 Jan; 251–255. 10.2190/OM.65.4.a