Abstract

The US Agency for International Development (USAID) launched a significant effort to improve global immunization coverage in the mid-1980s, beginning a long history of investments in various approaches to supporting the improvement of national vaccination programs in developing countries. As Primary Health Care evolved, USAID's approach to immunization also evolved, heavily influenced by the child survival revolution, a period when the global community struggled to define an approach that incorporated the essence of the Alma-Ata Conference with the selective primary health-care approach. Eventually, what became known as the ‘twin engines' approach, a focus on two high impact interventions—immunization and oral rehydration therapy—would characterize USAID's child survival program. As coverage fell during the less favorable international economic climate of the 1990s, USAID re-evaluated its approach and moved toward a more system strengthening concept. At the turn of the century, with the pressure of measurable impact, the Agency moved toward more easily measured inputs and away from the longer-term system strengthening activities of the previous two decades. This approach emphasized simple, proven technologies, more public/private partnerships and greater investment in vertical disease programs with short-term impact. Investments such as polio eradication and vaccine purchase through the GAVI Alliance (formerly the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization) became funding priorities for the Agency. Today, USAID faces a challenge of how it will support developing country vaccination programs. Will it provide assistance through vertical disease efforts and material inputs or will it shift back to a more system strengthening approach? The answer has not yet been provided.

Introduction

In the mid-1980s, the United Stated Agency for International Development (USAID) fully committed itself to a significant effort to improve global childhood immunization coverage. This effort was fueled by the recognition that childhood mortality and morbidity had reached unacceptable levels and that developed countries had an obligation to act in order to reverse this situation. As President Bush stated at the World Summit for Children in 1990 as he addressed the world's leaders, ‘let us affirm, in this historic summit, that these children can be saved. They can be saved when we live up to our responsibilities, not just as an assembly of governments, but as a world community of adults, of parents'.Citation1

The exact nature of those ‘responsibilities’, however, was left somewhat vague and over time has been, and would continue to be, a highly debated subject. To fully understand what lead to the approach that USAID took in its child survival programs, and specifically immunization, it is necessary to understand the dynamics of how the world was viewing health and development and how US foreign assistance policy with respect to child health programs evolved into its present form.

The global environment which saw the development of USAID's approach to immunization was born out of a dynamic period characterized by a struggle to define the most efficacious approach to bring about sustainable improvements in health status among the world's most disadvantaged populations. The prevailing schools of thought that evolved from the 1950s to the present ranged from traditional Western medical models which focused most of their attention on curative urban services to more progressive reform models that focused on community-based approaches and even to some degree the social determinants of health.

During the 1950s and 1960s, donor support was oriented primarily toward a post-colonial approach, focusing on high-technology curative care for developing country elites which resulted in the low prioritization of primary health-care programs for the poor and rural segments of the population. What international public health programs that did exist, stressed vertical disease programs such as smallpox eradication, malaria control and yaws treatment.Citation2 While these disease specific programs were born out of a pressing need to combat extremely serious health threats, they were designed as vertical campaigns targeting only a specific disease and largely ignoring the social and economic environments which characterized the spread of the vectors and the disease. In doing so, these programs failed to incorporate an approach which was sensitive to the economic, social and political determinants of health and failed to take into account the issue of poverty as a substantial contributor to health status in a meaningful and substantive manner.

During the late 1960s and 1970s, the medical and vertical disease models were showing mixed results and having questionable development impact on the poor. At the 1976 World Health Assembly, Halfdan Mahler, Director General of the World Health Organization (WHO), passed the ‘Health For All by the Year 2000’ resolution. The principle of Health for All was captured in its definition of health which noted that health was ‘… a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’. It further stated that health ‘is a fundamental human right and that the attainment of the highest possible level of health is a most important world-wide social goal whose realization requires the action of many other social and economic sectors in addition to the health sector’.Citation3 Mahler actualized this definition by identifying four basic pillars for action: (i) appropriate technology that is socially acceptable and affordable; (ii) political will to allow the population to lead economically productive and socially fulfilling lives; (iii) intersectoral cooperation between all relevant sectors of the government and civil society; and (iv) community and individual participation and empowerment in the areas that control health status.

This broad definition of health gave rise to community-based health programs as a more effective way to improve the health status of isolated and disadvantaged populations. The movement was characterized by a strong focus on Primary Health Care (PHC), which took on a broader definition than it had in the past. PHC was basic health care, but it went beyond the traditional medical approach and embodied grassroots decision making and the incorporation of economic, social and political issues into the discussion about the production of health. It was designed to be a truly empowering movement that shifted authority away from the established medical infrastructure to community-based decision making that created a paradigm changing moment.

The Alma-Ata Conference on Primary Health Care, two years later in 1978, provided the substance to that concept and articulated the actions that were needed to bring about real change. The Alma-Ata Declaration stated that: ‘Primary Health Care is essential health care based on practical, scientifically sound and socially acceptable methods and technology made universally accessible to individuals and families in the community through their full participation and at a cost that the community and country can afford to maintain at every stage of their development in the spirit of self-reliance and self-determination. It forms an integral part of both the country’s health system, of which it is the central function and main focus, and of the overall social and economic development of the community’.Citation4

The concept of community-based health programs had strong implications for international health programming and because of its revolutionary approach, it also generated a strong backlash from entrenched interests. While the four principles set forth by Mahler, as noted above, were influential in USAID's child survival program design, their interpretation was not as structurally transforming as envisioned by Alma-Ata. The idealism of PHC that was expressed in the Alma-Ata Declaration soon began to be transformed by a wave of technical programming around specific mortality and morbidity reduction programs that were to have profound impact on child survival design. This reinterpretation altered concepts such as community empowerment into community participation, and seriously diluted its impact as a transformational strategy. Issues such as feasibility to implement, low cost and approaches that had proven impact, were used to replace the broader concepts expressed in ‘Health For All’.

Countering the more structurally aggressive approach of Alma-Ata, in 1982, under the direction of Jim Grant, United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) launched the Child Survival Revolution, which was an international initiative to reduce mortality rates among infants and children. The center piece of the initiative was GOBI, which was a selective child survival approach involving growth monitoring, oral rehydration therapy for diarrhea, breastfeeding and immunization (GOBI). GOBI was seen as a targeted package of interventions that were feasible, low cost and had proven measurable impact on child morbidity and mortality. For many, however, even the comparatively narrow programming confines of GOBI were too broad and so UNICEF introduced a more focused approach that restricted its emphasis on only two of the interventions—oral rehydration therapy and immunization. This approach became known as the twin engines of child survival, and was highly influential within the planning structures of USAID.

The ‘twin engines’ strategy focused its effort on selective primary health-care activities that promised the greatest possibility for morbidity and mortality reduction with the most cost effective level of inputs. Lost were the more horizontal community-based, poverty-oriented approaches of Alma-Ata. Immunization was a critical aspect of the ‘twin engines’ approach as it not only had an immediate mortality and morbidity reduction component, but it also was a strong system building intervention, which laid the foundations for health system strengthening in areas such as service delivery, disease surveillance, logistics, training and supervision.

THE LAUNCH OF EXPANDED PROGRAM ON IMMUNIZATION (EPI): PLATFORMS FOR USAID'S IMMUNIZATION STRATEGY

In 1974, the WHO launched the EPI to prevent six major vaccine preventable childhood diseases—polio, diphtheria, tuberculosis, pertussis (whooping cough), measles and tetanus—with individual national governments creating and implementing their own policies for vaccination programs following the guidelines set forth by EPI. When the program was launched, less than 5% of the world's children were immunized during their first year of life.Citation5 Ten years later, in 1984, at the Bellagio Conference on ‘Protecting the World's Children’, the Universal Childhood Immunization (UCI) program was put forth by UNICEF under the charismatic leadership of James Grant.Citation6 UCI quickly became the core of the Child Survival Revolution. The goal of UCI was set in 1990 noting that ‘immunization levels need to be raised further, aiming to reach levels of at least 80% for all children of the world by 1990 and of at least 90% by the year 2000, within the context of comprehensive maternal and child health services. This will require considerable continued effort, particularly in improving the management of immunization services’.Citation7

EPI and UCI provided effective platforms for USAID's immunization strategy that would serve the Agency for several decades. In 1985, USAID launched the Technology and Resources for Child Health Project which marked the first major effort for a global project that would provide assistance to countries and the global technical community in support of childhood immunization services. This activity focused on improving the efficiency and equity of EPI worldwide by expanding coverage, improving program efficiency, increasing the level of training and strengthening the logistical and management systems to support immunization and eventually other primary care interventions. In 1987, USAID also started the HealthTech Program, which was charged with discovering new and appropriate cost effective technologies to apply to immunization programs in the developing world.Citation8 Additionally, USAID ramped up support for programs in measles campaigns and the global polio eradication program. The overall focus of the Agency at this time was mortality reduction through measurable immunization activities in target countries. As the Agency noted in its sixth report to Congress, it had ‘launched a major child survival initiative and committed itself to a course of action to bring a significant reduction in the number of preventable child deaths in the developing world’.Citation1

USAID's strategy focused on several key areas that the Agency used to define its approach to morbidity and mortality reduction: (i) focus on a few relatively simple, proven technologies; (ii) focus on countries with high child and infant mortality rates where greatest impact can be made; (iii) collaborate with other partners such as WHO, UNICEF, universities and host country institutions; (iv) mobilize and work closely with the private sector; (v) provide technical assistance; (vi) promote sustainable services; (vii) increase effectiveness though problem-solving applied research; and (viii) monitor, evaluate and refine program services.

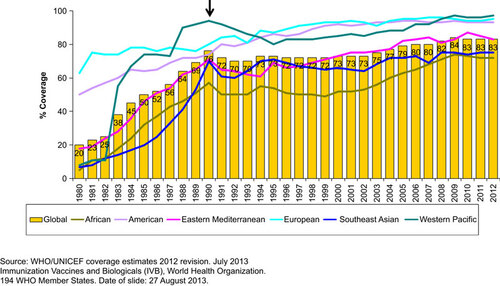

While certain elements of this strategy received more attention than others, the shift away from the social and political structural modifications of the ‘Health For All’ approach became clear. The idealism of ‘Health For All’ had been replaced with a more pragmatic model of high impact at low cost within a short time frame. This methodology shift was not uncommon and represented the prevailing approach for most international health organizations and bilateral donor agencies at the time. The impact over the next three decades would be dramatic. Global coverage, as seen in Figure , increased dramatically, but while this was happening, the approaches used and the global economic environment were conspiring against the long-term sustainability of the progress achieved.

EPI and UCI were significant forces in drawing resources and attention to the global immunization push of the 1980s and early 1990s. As Figure shows, coverage, as measured by the third dose of DTP (diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis) vaccine (DTP3), was pushed to what, at the time, was reported to have reached the target level for 1990 of 80%. While later adjustments reduced this achievement somewhat, nevertheless, the accomplishment had been remarkable over such a short period of time. Donors and developing countries celebrated the achievement of reaching the 1990 target while paying less attention to the methods that were used to accomplishment this feat, their sustainability and the collateral impact that this vertical program was having on the development of health capacity in developing countries.Citation9 They also seemed less aware of the looming impact of the larger global economic environment, characterized by structural adjustment, which was severely weakening national capacity to sustain the infrastructure needed to maintain and expand immunization coverage.Citation10 These factors were part of a complex mosaic that was undermining many of the gains in immunization made up to the early 1990s and setting the stage for stagnating performance during the coming decade.

As Figure shows, the most dramatic change in coverage improvement can be seen in Sub-Saharan Africa. While the region never actually reached the 1990 target, it did show steady and remarkable increases in coverage throughout the 1980s. However, as events conspired to detract from a focus on vaccination after 1990, the coverage rate for DTP3 began to drop. Regionally, it fell to about to 50% in 1991 and stagnated at close to that level for most of the rest of the decade. Not only was this a time of lower coverage and consequently more children going unprotected, but countries were unable to introduce new vaccines into their routine schedule and the advantage of vaccines such as hepatitis B was going unrealized in many countries. The 1990s was a critical period for immunization programs worldwide as donors and national programs had to adjust to a difficult global economic environment largely characterized by structural adjustment programs, as well as the consequences of their own unsustainable approaches that were employed during the previous decade. While the global economy was largely beyond their control, the manner in which an agency such as USAID-assisted countries was well within the scope of change.

To assist that change process, in 1996, UNICEF commissioned a study on the lessons learned from UCI and provided the following key insights that highlighted the weaknesses of the program as:Citation9 (i) the lack of operational flexibility in the use of campaigns as the main strategy for delivery of services; (ii) local efforts to build community input were often overwhelmed by large amounts of target-driven external resources; (iii) the capacity for UCI to detract from the development of PHC systems; (iv) there was too little attention to building national systems for the development of national capacity; (v) the focus of progress in terms of coverage as opposed to disease indicators and the development of surveillance systems; and (vi) the lack of an explicit strategy for addressing sustainability.

From these insights and USAID's own observations, the Agency decided that it could best serve the long-term need of developing countries by engaging a strategy that concentrated more effort on the service delivery and capacity needs of national programs. That approach would focus on inputs such as providing intensive technical support to countries in areas such as cold chain management, vaccine and materials logistics, personnel management, training, program planning and design, policy and practices, advocacy and communications, monitoring and surveillance, and financing.

Furthermore, USAID's interpretation of the programmatic trends lead to the conclusion that inadequate attention had been placed on the long-term development aspects of national immunization systems in developing countries. Attention had been given, overwhelmingly, to achieving short-term coverage targets at the expense of long-term capacity. This analysis led to a focus in programming within USAID toward a technical assistance approach with a longer time horizon that would assist counties in a bottom-up development approach. While results in terms of outcome (coverage) and impact (mortality reduction) would be slower in achievement, the accomplishments achieved would be more sustainable and contribute to a viable community-based health-care system. Albeit, this was not the type of community-based system envisioned by Alma-Ata and did not fully embrace the social determinants of health, it was, however, a more constructive and sustainable version of the selective primary health-care concept that was designed to reverse the negative trends seen after the coverage peak in 1990.

USAID's focus became building sustainable capacity to implement services that supported strengthening primary health-care structures while improving the efficiency and equity of coverage. In addition to a focus on country needs, the Agency also became intimately involved in international immunization policy and influencing global technical standards through its experience and close involvement with on-the-ground work and bringing that experience to the global arena with groups such as WHO and UNICEF. However, the primary effort remained to work with developing countries at all levels in order to facilitate change through the process of strengthening national capacity.

USAID'S STRUCTURAL CHALLENGE

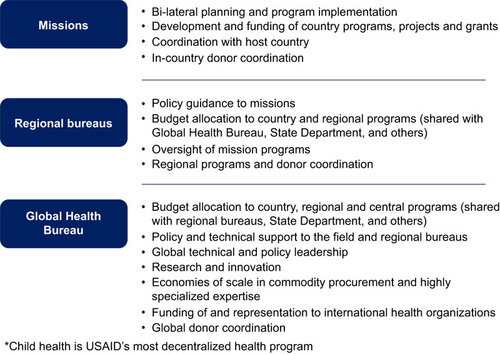

During the 1990s, USAID itself was in a process of structural reform. Programming and funding authority were being shifted dramatically within the Agency to further decentralize responsibilities. The centralized strategic decision making that characterized the Agency in the first part of the decade was being shifted to missions and the role of Global projects was changing dramatically. While this change placed greater responsibility for program decisions at the field level, it somewhat hindered the ability of the Agency to adopt unified global technical strategies. The struggle to adapt to this change has been long and in some cases, difficult. Programs such as immunization have less control over resources and technical direction, but they also gained more involvement of USAID mission staff. Even now the full impact of USAID's decentralization is yet to be fully evaluated. However, it is clear that the process remains in place and there are no immediate signs of change.

The current structure for technical programming and resource allocation incorporates country missions, regional bureaus and global technical bureaus. The responsibilities of implementation are divided in a manner that facilitates effective programming. Figure shows the roles of each unit and how they support each other. While in optimal situations, these relationships function efficiently and effectively, they sometimes suffer from a lack of coordination and oversight that prevents harmonized planning and implementation across the Agency. This can often be traced back to a lack of coordinated funding guidance and inadequate leadership in the articulation of clear objectives. This relationship is further complicated by the insertion of the Department of State into the process as noted by former USAID Administrator Natsios.Citation11 However, for the most part, the decentralization of the Agency works well and provides an opportunity to engage in innovative field work that helps countries acquire the basic skills needed to move their programs ahead. Immunization rates in many USAID-assisted countries stabilized during the 1990s and began to show indications of improvement by the turn of the century.

THE COMPONENTS OF USAID'S APPROACH

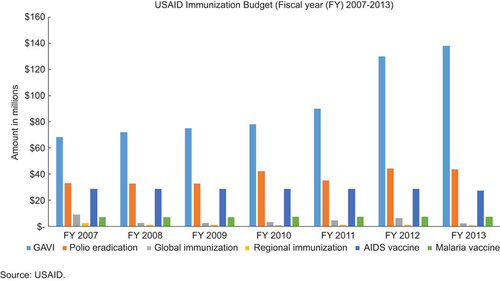

USAID has a multipronged approach to supporting immunization utilizing several areas of work to combine into an overall program. The critical issue is the degree to which the Agency has emphasized the various areas at various times over the last three decades. The best measure for this is the level of funding that has gone into each area of work. However, that data are difficult to acquire and is often misleading due to how the Agency's financial reporting systems are structured and the influence of congressional earmarks. Furthermore, after the decentralization of funding that occurred in the late 1990s, reporting on mission funding by program element is unclear in some cases. Since immunization is only reported as a ‘planned’ expense and not an actual expense, it is very difficult to validate actual utilization by missions who may significantly alter their planned allocation of funds after the reporting process is complete. Figure shows the most reliable data for planned activities under the element of immunization since fiscal year 2007. Mission figures are not shown given the difficulty in verifying their utilization for immunization activities. Nevertheless, it can clearly be seen where the Agency's emphasis on funding has been placed.

A brief description of the various areas of work which USAID supports within its overall immunization strategy follows.

Routine immunization systems

The focus of much of the international community prior to the 1990s was on increasing coverage to meet the targets set by UCI as opposed to building sustainable and equitable health-care systems. The performance of UCI was subject to a wide range of factors from the specific orientation of the donors to the level of coordination among donors and countries to the global economy and subsequent financial commitment to health programs and foreign assistance in general. The methodologies that were advocated and applied were mixed, and while it can be argued that the experience of UCI had a distinct overall positive impact on health delivery capacity in many countries, strategies were often utilized that did not build sustainable capacity in the target countries. An evaluation of UCI noted that ‘in general, it was felt that those countries with well-developed health systems were better able to absorb and effectively apply resources during UCI and consequently to maintain or sustain coverage’.Citation9 Consequently, countries with poor health systems had their coverage supported more by mass campaigns that offered less sustainable system strengthening inputs and thus, did not receive the intensive system building attention of which they were most in need.

The debate over the impact of the strategies applied in order to achieve coverage targets will continue, but the decade of decline that was observed in the 1990s informed USAID program designers that a more system strengthening approach was called for: one that invested more technical assistance in a longer timeframe to produce the level of change that was required to secure the lasting benefits of vaccination. The USAID Technology and Resources for Child Health Project and its larger and more comprehensive follow-on projects—BASICS (Basic Support for Institutionalizing Child Survival); the IMMUNIZATIONbasics Project and the MCHIP Project (Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program)—were designed to provide those inputs. An intensive system strengthening element focused on the routine immunization system with the objective of building capacity at the country level to be able to design, plan, manage and implement effective, equitable and sustainable immunization services in target countries. The critical methodologies used by these projects were: (i) provision of world class technical assistance; (ii) establishment of bilateral and multilateral partnerships; (iii) operations research into issues affecting delivery of services; (iv) communications and behavior change approaches; (v) private sector partnerships; (vi) involvement from the community to the national level; (vii) advocacy for local issues at the global level; and (viii) continued focus on the routine system as the backbone of immunization services.

The strategy that USAID adopted was that the core of the national immunization program in any country was the routine system. This was the systematic capacity of a health-care system to provide childhood vaccinations to children at the appropriate age in a safe and consistent manner. It could draw on a number of approaches ranging from fixed facility to outreach to campaigns. However, whatever strategy was applied for a specific population, the critical feature was that it was one that could reach all the children at the appropriate age and was reproducible over time. This required the necessary equipment, training, management, supervision, planning, logistics and evaluation. Strategies that were applied to meet immediate coverage targets but which could not be expected to be reproduced on a consistent basis were not considered routine.

The focus on this broad definition of ‘routine’ gave USAID flexibility with respect to the type of assistance it offered, but it also required a long-term focus on results. It required developmental inputs that empowered all levels of the health system to have input into policy decisions and it required international donors to respect the needs and interests of host countries. The inputs could be measured in whatever terms suited the resources of the donor agency, but its outcomes were more difficult to measure as they required longer timeframes than a donor agency was accustomed to providing. It was this phenomenon that was to be the burden to this developmental approach to improving national immunization capacity. As international pressure grew for short-term mortality reduction impact targets, the ability to commit resources to long-term development activities was under considerable pressure. Over the years, following the turn of the century to the present, the dramatic shift of Agency resources away from developmental approaches toward ‘countable’ inputs has clearly been demonstrated. The impact that this shift will have on developing countries has yet to be fully realized, but failing to provide substantial support to strengthening national capacity for the routine immunization system will only mean that we have failed to learn the lessons of the 1990s.

Health technology

During the 1980s and 1990s, USAID also invested heavily in the development of new health technologies that could address operational issues confronting developing countries. Through the HealthTech Project, USAID invested in the development of appropriate technologies which would serve to make immunization services safer and more effective.Citation8 Among these was Soloshot, the first autodisable syringe that is automatically disabled after one use and cannot be refilled or reused, preventing transmission of blood-borne diseases from needle reuse. This technology was developed by HealthTech and licensed to Becton Dickinson, a medical technologies company, for production. According to HealthTech, more than six billion of these syringes have been used worldwide. Another HealthTech product that has had significant impact is the Vaccine Vial Monitor, a small label that is affixed to individual vaccine vials that records exposure to heat and provides a visual indication of whether the vial can still be used or should be discarded due to too much heat exposure. Today, more than four billion have been distributed and 94% of UN-purchased vaccines are labeled with Vaccine Vial Monitor. Finally, HealthTech developed the Uniject injection system, which is a combined needle and syringe which is prefilled with a vaccine or pharmaceutical and can only be used once. Uniject has been used for nationwide delivery of hepatitis B vaccine to newborns in Indonesia for almost a decade because its practical field advantages enable midwives to immunize newborns in both home and clinic settings.

Disease eradication

As part of a world-wide effort to eradicate smallpox undertaken by WHO, in 1966, USAID entered into the global immunization arena supporting a large regional project in Africa to control measles and eradicate smallpox. Investments in the development of a jet gun injector accelerated smallpox eradication by advancing the use of new technology for mass immunization campaigns. USAID was active in the smallpox eradication program through the 1970s, as well as being an early strong advocate for measles control. In the 1980s, USAID provided significant support to Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) to strengthen EPI programs in the region while seeking to eradicate polio in the Americas. In 1996, Congress provided a funding earmark which allowed the substantial investment of Agency resources into polio eradication to extend to other WHO regions (AFRO, EMRO, SEARO, EURO). The Agency sought to learn from the successful eradication of polio in the Americas and apply these lessons to the global effort for polio eradication in collaboration with other partners, primarily WHO, UNICEF, Rotary International and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Citation12 To date, the Agency has spent over one half billion dollars on this global program and continues to be actively involved in the international Global Polio Eradication Initiative—investing primarily in improving acute flaccid paralysis surveillance and laboratory capability to identify cases of polio, as well as communications activities. At the global level, USAID supports tools used to accredit the 148 laboratories in the global polio laboratory network. Regionally, USAID funds are used by WHO to convene country and regional activities including certification commissions, regional advisory groups, cross-border meetings, and training and technical meetings. At country level, USAID funds support full-time surveillance officers to conduct acute flaccid paralysis surveillance and works with non-governmental organizations to also conduct community-based surveillance and to mobilize communities and disseminate messages on polio, routine immunizations and broader health issues such as water and sanitation, breastfeeding and hand washing.

Vaccine research and development

Beyond the focus on immunization systems and technologies, USAID has had a history of working with other US Government Departments and Agencies to explore the development of vaccines for specific diseases—most notably malaria and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The approach has been to accelerate and advance potential vaccine candidates against HIV and malaria through the regulatory pathway towards licensure and commercial use. USAID initiated the Malaria Vaccine Development Program at the termination of the first global malaria eradication program in the 1960s. USAID reasoned, in the context of the increasing global burden of malaria and increasing drug and insecticide resistance (at a time before the President's Malaria Initiative), research toward better tools, such as a vaccine, was a sound investment to addressing the malaria problem. USAID's long and strategic investments in the field through a variety of partners in government, academia, non-governmental organizations and commercial entities (e.g., Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Naval Medical Research Center and the Malaria Vaccine Initiative at PATH) have contributed to accelerating progress toward the goal of an efficacious and cost-effective vaccine. Notably, the Agency's contributions to the culture of Plasmodium falciparumCitation13 transformed the field and the cloning of the gene for the circumsporozoite proteinCitation14 lead directly to the first clinical trials based on this moleculeCitation15 and ultimately, to GlaxoSmithKline's RTS,S vaccine trial currently in phase III testing.

Unlike the Malaria Vaccine Development Program model, USAID's investments in HIV are currently concentrated through the International Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) Vaccine Initiative. Through International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, USAID is able to leverage translational capacity, strengthen scientific and clinical research capacity in developing countries, develop novel vaccines through applied research and strengthen the global environment for AIDS vaccine development and future access and delivery. Achieving an AIDS-free generation is a vision and a priority for the Agency with an HIV vaccine as a central strategy.

Vaccine supply

The first global program to assist low to middle-income countries in vaccine procurement was the Vaccine Independence Initiative (VII), established by UNICEF and WHO in 1991. This program supports countries to become self-reliant in the procurement of the vaccines needed to maintain their national immunization programs. The VII, managed by UNICEF, allows countries to pool their procurement, thereby getting better prices and arrangements; pay after delivery; utilize local currency through a swap mechanism with UNICEF; and, benefit from economies of scale. The goal of the VII is to help countries become independent in vaccine funding and procurement while maintaining a steady supply of approved and high quality vaccines. USAID helped to capitalize the VII fund and encourage United States-assisted countries to make use of this valuable asset.

USAID also supported the PAHO Revolving Fund, a pooled procurement mechanism to purchase vaccines, syringes and immunization supplies. The success of this collective purchasing mechanism helped expand access to vaccines in Latin American and Caribbean countries. The PAHO Revolving Fund has played a central role in immunization programs, leading to high vaccination rates and introduction of new vaccines as well as vaccine self-sufficiency in many member states.Citation16

In 2000, the global community realized that a different mechanism was needed to expand access and introduce new vaccines to developing countries and so, with the support of a substantial grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the GAVI Alliance (formerly the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization) was started. This fund has grown substantially and USAID plays a major role in its governance and financing. Through the year 2015, the US government, through USAID, will have contributed over US$1 billion to GAVI. These funds go for the purchase of vaccine.

THE NEW ENVIRONMENT OF GLOBAL GOALS

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, USAID was undergoing substantial internal changes as the Agency was coming more under the influence of performance-based measurement. This concept, expressed through various administrative mechanisms, put more emphasis on clear targets and measurable performance over shorter time periods. The impact on strategies such as that being applied toward immunization was in part to place greater emphasis on programs that could be easily counted and where the metrics of change could be easily measured over annual time frames.Citation11 Long-term investment in system changes that were not easily measured by simple metrics were less attractive and, therefore, received fewer resources. As former USAID Administrator Andrew Natsios notes, ‘pressure from the counter-bureaucracy, the Congress, and the State and Defense Departments has driven institution building and policy reform to the back seat, while service delivery has taken over’.Citation11

While former Administrator Natsios observed a preference for public health programs that can be easily measured, he did note that ‘even within health programs, institution building is more difficult to measure and takes a long time to produce quantitative results and is increasingly underfunded’.Citation11 Figure shows the funding profile for USAID immunization activities over the last seven budget cycles. The allocation of funds is largely influenced by Congressional earmarks but levels such as that for GAVI are also strongly supported by the current Administration, which supported major funding increases as a central strategy to expand access to immunizations. Since allocation of funds to GAVI are transfers to an international organization that purchases vaccine, this approach would seem to support former Administrator Natsios' point that they simply appeal to the ‘counter-bureaucracy’ and Congresses' need for easily measurable outcomes as opposed to long-term development investments. The long-term development investment in support of routine immunization systems is represented in Figure by the global and regional immunization bars. It can be seen that this area of investment has received decreased funding over time with increased funding in areas with more easily quantified measures of performance such as vaccine procurement.

The trend away from system building became even more embedded within the culture of USAID's programming as new global and Agency targets were adopted. In September 2000, the global community adopted the Millennium Development Goals (MDG), of which MDG 4 targets a reduction of global under-five mortality rates by two-thirds from their 1990 levels by the year 2015. This placed further pressure on the Agency to focus on short-term measurable activities that have direct impact on under-five mortality. Furthermore, in 2009, the Global Health Initiative, a US Government commitment to maximizing investments to address global health challenges, was launched establishing a target for a reduction of under-five mortality rates in US government-assisted countries.Citation17 Subsequently, the recent Child Survival Call to Action in 2012 called for an end to preventable child deaths by the year 2035.Citation18 All these quantifiable targets give emphasis to interventions and strategic approaches that are measurable, focused and can have significant impact on mortality levels within a relatively short period of time. The message to the allocation of resources within USAID is reflected in these trends. Long-term community-based development investment to insure that the short-term mortality and morbidity gains are sustainable through stable primary health-care systems, such as the routine immunization system, is overshadowed by other Agency priorities.

THE FUTURE FOR IMMUNIZATION AT USAID

The USAID child survival strategy has always been a selective primary health-care approach leveraging small investments to gain high returns in mortality reduction. The justification for low-cost approaches is affordability and sustainability in low-resource environments. Immunization services offer an excellent opportunity for this type of strategy as vaccines have always been considered one of the most cost-effective health investments possible and the external benefits of logistical and managerial capacity that are developed during implementation of the ‘vaccination system’ dramatically increase its cost-effectiveness and utility for other child survival interventions.

In the early years, the focus of immunization activities at USAID and other global health organizations was primarily on increasing national coverage rates over a short timeframe. This approach required the most attention to be given to strategies that delivered immediate impact on reportable outcomes, such as national DTP3 coverage. However, USAID recognized that the ability of countries to maintain these rates depended on the sustained viability of the vaccination system and the primary health-care system in which it was embedded. Preserving the ability to maintain and expand a country's capacity to deliver vaccination services in an equitable and safe manner would rely on long-term development assistance that would build the necessary management and technical infrastructure. This aspect of donor assistance had largely been subsumed by the imperative to achieve high coverage, but must now be incorporated into an effective and appropriate health development strategy for the future by USAID. Furthermore, the ability of developing countries to address the threat of emerging and re-emerging diseases, for which vaccines are available, will depend on the presence of an immunization infrastructure that is capable of incorporating new vaccines into an efficient and universal routine system that is not disruptive to other critical primary health-care programs. For organizations such as USAID, this calls for a foreign assistance strategy that prioritizes a system building approach that places long-term development as its primary objective.

Critical operational decisions need to be made as to how emerging and re-emerging diseases will be handled as new vaccines are developed as well as what considerations will factor into the research and development process for those new vaccines. Targeted vertical programs, such as those used for smallpox and polio eradication, as well as measles elimination, are an option that provides short-term gains, but, at least in the case of smallpox eradication, have been shown not to offer significant long-term system benefits. As vaccines for malaria and HIV are developed, they will face serious introduction issues and the manner in which they are introduced and used to achieve their morbidity and mortality reduction impact needs to be carefully assessed to assure that their system impact does not detract from the long-term development of sustainable immunization systems. The potential for new vaccines to have negative impact on immunization systems needs to be addressed as an ongoing system building effort, but it also needs to be a consideration during the vaccine development phase. Potential negative system impact needs to be critically evaluated for new vaccines during their development and prior to their introduction into stressed systems in developing countries that have not had the attention of long-term infrastructure investments. The development of new vaccines for emerging and re-emerging diseases cannot be simply a scientific pursuit. The target product profile needs to take into consideration systems issues like price, how the vaccine will fit into the routine schedule, its cold chain capacity requirements and other programmatic practice considerations. The push toward the development of new vaccines that can combat emerging and re-emerging infections will only be sustained as those vaccines are pulled into effective and equitable vaccination delivery systems and researchers have accounted for the operational and economic appropriateness of the vaccine to the environment in which it will be used. If the investment in immunization system strengthening is not adequate from development agencies and national governments and research institutions do not address the appropriateness of vaccines for developing countries, then the pull effect will disappear and the result will be a serious negative impact on vaccine research and development, as well as public health.

Immunization, like other technical programs at USAID, has continued to be influenced by the force of performance indicators and the current program is heavily influenced by global and bilateral performance targets, which are quantifiable, time-sensitive, mortality reduction objectives. While these goals have clear humanitarian value, they, nevertheless, have the same programmatic impact of the high coverage targets of the 1980s. They tend to drive the program to measurable impact while avoiding the developmental aspects of how those impacts were achieved. USAID is confronted with balancing short-term vertical high-impact approaches that offer the best route to achieving the level of desired mortality reduction with longer-term developmental approaches, which offer more basic and foundational changes in the conditions which contribute to poor health status.

The future challenge for USAID is to embrace the short-term programmatic methodologies that global mortality and morbidity reduction goals tend to dictate with the long-term strategies for structural change and the ability to address the social and economic determinants of health that programs defined in the true spirit of Alma-Ata offer. With respect to immunization the challenge is clear—do we invest primarily in the tools of vaccination or do we blend this with a more concerted effort to build the infrastructure to allow countries to address issues such as equity, sustainability, accessibility and responsiveness to mention just a few? USAID has the opportunity to be a leader at this critical moment in the evolution of the Child Survival Revolution and the work that the agency decides to emphasize in immunization will exemplify how they meet this challenging decision. USAID has an opportunity to step forward in defining an innovative public health approach, which will require defining a strategy that can be drawn from the spirit of Alma-Ata while defining constructive models of change that will have rapid impact on the health status of all people. It will require a commitment of remarkable proportion and committed intellect to bring health—and immunization—to all.

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not reflect opinions and views of the US Government.

- US Agency for International Development. Child survival 1985–1990: a sixth report to congress on the USAID Program.Washington, DC US Agency for International Development, 1991.

- Werner D, Sanders D. Questioning the solution: the politics of primary health care and child survival.Palo Alto Health Wrights Publishing, 1997.

- Mahler HT.The meaning of “health for all by the year 2000”. World Health Forum1981;2: 2–22.

- World Health Organization.Declaration of Alma-Ata.In: Proceedings of International Conference on Primary Health Care; 6–12 September 1978; Alma-Ata, USSR.WHO Geneva, 1978: 3.

- United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. Expanding immunization coverage.New York UNICEF, 2011.Available at http://www.unicef.org/immunization/index_coverage.html (accessed 21 October 2013).

- Rockefeller Foundation. Protecting the world's children: vaccines and immunizations within primary health care.New York Rockefeller Foundation, 1984.

- World Health Organization.Expanded programme on Immunization. Global Advisory Group. Wkly Epidemiol Rec1989;64: 5–12.

- PATH. HealthTech Program. Technologies for high-priority needs.Seattle PATH, 2013.Available at http://www.path.org/projects/healthtech.php (accessed 21 October 2013).

- United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund. Sustainability of achievements: lessons learned from universal child immunization.New York UNICEF, 2006.

- Kim JY, Millen JV, Irwin A, Gershman J (eds.). Dying for growth: global inequality and the health of the poor.Monroe Common Courage Press, 2000.

- Natsios A. The clash of the counter-bureaucracy and development.Washington, DC Center for Global Development, 2010.Available at http://www.cgdev.org/content/publications/detail/1424271 (accessed 7 October 2013).

- US Agency for International Development. The USAID Polio Eradication Initiative.1998 Report to Congress.Washington, DC USAID, 1998.

- Trager W, Jensen JB.Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science1976;193: 673–675.

- McCutchan TF, Hansen JL, Dame JB, Mullins JA.Mung bean nuclease cleaves plasmodium genomic DNA at sites before and after genes. Science1984;225: 625–628.

- Herrington DA, Clyde DF, Losonsky G et al.Safety and immunogenicity in man of a synthetic peptide malaria vaccine against Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites. Nature1987;328: 257–259.

- Pan American Health Organization. PAHO/WHO Revolving Fund helps countries provide free vaccines during Vaccination Week in the Americas.Washington, DC PAHO, 2013.Available at http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=8598%3Apahowho-revolving-fund-helps-countries-provide-free-vaccines-during-vaccination-week-in-the-americas&catid=740%3Anews-press-releases&Itemid=1926&lang=en (accessed 20 October 2013).

- US Global Health Initiative. Child health.Washington, DC GHI, 2013.Available at http://www.ghi.gov/results/docs/CHTarget.pdf (accessed 20 October 2013).

- United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund. Global leaders to chart course towards the end of preventable child deaths.New York UNICEF, 2012.Available at http://www.unicef.org/media/media_62614.html (accessed 20 October 2013).