Abstract

In this empirical case study we explore the fantasy nature of strategy work and propose fantasising as a framework contributing to the nascent literature dealing with the previously overlooked fantasy nature of strategy. More specifically, our interest is on examining how the meaning of official strategy gets constructed as it is being implemented, as well as and how and why the perceptions may evolve during implementation. Our data consists of official strategy documents and interviews from Finland's largest financial services group and its largest unit. The interviews cover all organisational levels, enabling us to reveal the variations of perceptions of strategy as it is being implemented. The data analysis is carried out by means of qualitative interpretation. According to our findings, the main goal of becoming the leading bank, as outlined in the official strategy, had been adopted throughout the organisation hierarchically. However, conceptions of what would constitute ‘a leading bank’ varied, especially horizontally. The plausibility of the official strategy is constructed through rational techniques (e.g. numerical ‘objective’ accounting information) intertwined with storytelling. As a result we propose that strategy implementation may best be understood as fantasising involving two forms: functional (explicit, short-term-oriented) and symbolic (metaphorical, long-term-oriented). We offer fantasising in these two forms as an addition to fantasy-oriented strategy literature for further exploration to better understand the nature of strategy work.

Keywords:

Introduction

The majority of the mainstream strategic management literature has paid little attention to how strategy may assume varied meanings during the implementation process as it is affected by different organisational actors trying to make sense of the official strategy. Instead, strategy is seen to remain constant supposing that stability, orderliness and predictability would prevail in social life, and as if human behaviour would be characterised solely by rationality (Boedker Citation2010). This is most often not the case in organisations, nor in social life more generally.

However, rational discourse with its logical-rational reasoning has persisted in organisation and management research (March Citation2006, Schipper Citation2009, Klikauer Citation2013). Mainstream management literature has traditionally operated in a rational paradigm that emphasises the importance of numerical information perceived as objective facts. Chua (Citation1986, p. 617) explains this firm belief in numbers fittingly: ‘Numbers are often perceived as being more precise and “scientific” than qualitative evidence’. However, managers may best be seen fundamentally as storytellers resorting to their beliefs and emotions in their work (McCloskey Citation1992, Pihlanto Citation2002, Taleb Citation2007). Thus, in this paper, we will take a closer look at strategy by looking at its salient elements, both those generally perceived as objective/rational (numerical) and those often seen as subjective/irrational (interpretative) to better understand how they are mingled together in strategy implementation.

The prevailing understanding of how accounting information may shape strategy and transform organisational reality is still too narrowly understood. In effect, by operating at the crossroads of two traditionally separate, yet closely connected fields of management study we are responding to Chua's (Citation2007, p. 493) call to rediscover accounting and strategy as ‘contingent, lived verbs rather than abstract nouns’. Hence we are able to benefit from ideational cross-pollination while doing so.

We take a social constructionist view on strategy work and maintain that the meaning of strategy is constructed in social interaction as it is communicated throughout the organisation. Hence, our point of departure is discursive and, in particular, narrative (Sonenshein Citation2010, Vaara and Reff Pedersen Citation2013). We see the use of language as having a central role in constructing and conveying meanings in organisational reality and building it. The primary form this meaning construction takes is narration; a cognitive process that arranges human experience in meaningful episodes (Polkinghorne Citation1988, p. 1). We define a story as an oral or written communicative act where particular events occur over time; therefore, all stories have a chronological dimension (Søderberg Citation2003). Furthermore, we follow Polkinghorne (Citation1988) and Czarniawska (Citation2004) in using the terms story and narrative interchangeably. Therefore, strategy can also be understood as storytelling with emplotted action (Gioia and Chittipeddi Citation1991), directions for activity embedded with numerical financial and non-financial information (such as key ratios and figures), or, as suggested in this paper, fantasising assuming varying forms and containing elements deriving from sources perceived either more or less ‘objective’ in varying degrees.

We will focus on illustrating how strategy implementation can be understood as fantasising; a form of organisational sensemaking (cf. Kets de Vries and Miller Citation1984) that takes place in functional and symbolic planning, and how numbers and ‘number talk’ as a particular form of discourse (cf. Chua Citation1986, Citation2007) are intertwined in these organisational processes.

We aim to contribute to the literatures having an orientation tilted towards fantasy in their treatment of either management accounting (e.g. Ahrens and Chapman Citation2007, Chua Citation2007, Jörgensen and Messner Citation2010, Skaerbaek and Tryggestad Citation2010) or strategy (Clegg et al. Citation2004, MacIntosh and Beech Citation2011) by empirically developing the concept of fantasising to better understand the nature of strategy work, in particular strategy implementation as a social phenomenon.

Research task

Strategy is present in everyday organisational routines but it only becomes existent for organisational members through the use of language; in other words, organisational discourses (Laine and Vaara Citation2011). For the purposes of this study, we are interested in how the meaning of ultimate strategic goal is being constructed in organisational discourse and how numerical accounting informationFootnote1 performs a role in this. As referred to above, the focus will be in particular on the implementation of strategy, involving fantasising.

Strategy may be best understood as prospective (future oriented) organisational meaning construction because strategic planning and plans orient to the future. Strategy implementation on its part is the process where prospective futures are enacted in the form of fantasy and fantasising. Thus, we focus on the perceptions and meanings attached to official strategy in different echelons of an organisation to better understand how and why strategy may assume evolving manifestations while being implemented. It is a matter of dissecting different conceptions about strategy adopted among organisational members and how these conceptions are related to everyday language usage and numerical accounting information.

Addressing these issues helps us better understand how the conception of strategy evolves in the implementation process and how numerical information and storytelling are intertwined in attempts to amplify the message contained in the official strategy and to concretise the abstract through fantasising.

Theoretical framing

In the following, we intend to draw out the discussions and central concepts we will use to build our argumentation and to support the analysis of our empirical data. We will first briefly outline the ideational background of the paper building on recent developments in strategy and management accounting literatures departing from mainstream of their respective domains, and explain how these will be utilised to support our analysis.

Likewise, we will present a discussion on how fantasy and fantasising – both neglected and empirically underdeveloped concepts in the strategy literature (MacIntosh and Beech Citation2011) – offer insightful ways to enrich our understanding of how strategy-related meaning is constructed, especially when it comes to strategy implementation. While the concept of fantasy is akin to the concept of fiction used for example by Barry and Elmes (Citation1997) and Bubna-Litic (Citation1995) in their conceptual work in an attempt to undrape strategic management's more fictitious nature, we resort to fantasy instead. We take fantasy to be a more inclusive concept and use it to support our description and discussion. Moreover, while the abovementioned contributions are important explorations into the narrative nature of strategy, they differ from our focus by being purely conceptual/theoretical in their orientation.

Departures from mainstream in strategy and management accounting

Both strategy and management accounting literatures have recently embraced an alternative, micro-orientation, as a way forward in understanding how organisational reality unfolds and how everyday micro activities at different levels of organisations actually play an important role in organisations and their functioning (see e.g. Whittle and Mueller Citation2010, Golsorkhi et al. Citation2011, Vaara and Whittington Citation2012). This orientation recognises the limits of rationality and planning orientation, which are the taken-for-granted assumptions in much of the modern management literature and reintroduces ideas dating back to such thinkers as Charles Lindblom (Citation1959) with ‘muddling through’, and Herbert Simon (Citation1947) with ‘bounded rationality’ as the guiding principles of both individual and organisational decision-making and resultant behaviour.

The fallacy of both rationality and stability as guiding principles in organisational life has been acknowledged recently resulting into increased concern for the micro-dynamics of strategy-making (see e.g. Whittington Citation2006, Jarzabkowski et al. Citation2007). Central for the concentration on micro-dynamics is that it takes ‘an interpretive approach in which the world cannot be understood independently of the social actors and processes that produce it’ (Kaplan Citation2007, p. 988). Research building on micro-dynamics can be said to operate within the interpretative research paradigm (Burrell and Morgan Citation1979) which is true for the current study as well.

The micro-dynamics perspective clearly contrasts with the traditional strategy literature in which strategy-making has been portrayed as a process led by rational analysis and decision-making in which managerial agency traditionally has supremacy in shaping what takes place (Wilson et al. Citation2010). Both the rationality and managerial supremacy assumptions have been heavily questioned, and established as unfounded (cf. Wilson Citation1992).

Furthermore, accounting regimes may play a key role in defining the ‘added value’ of ideas, with implications for how business strategies are formulated (Whittle and Mueller Citation2010). Moreover, Tillmann and Goddard (Citation2008) have pointed out that in order to better understand the relationship between strategy and accounting we should take a closer look into the sensemaking around management accounting and strategy. Also Jordan and Messner (Citation2012) recently pointed out how accounting numbers may be imperfect for management situations, but they still may provide the stimulus for many kinds of processes in organisations involving construction of meaning.

Focusing on ‘strategy-accounting talk’ (Chua Citation2007, p. 492) allows, for instance, for the discussion of how accounting is woven into strategic considerations and debates, as well as how accounting concepts are mobilised when crafting strategy (Jörgensen and Messner Citation2010). Thus, there seems to be growing agreement between strategy and management accounting scholars that a closer connection of the two fields would advance our understanding of how and by which means the varying meanings of strategy get constructed in organisations, and what is the role of ‘numbers talk’ in the process.

Numerical accounting information may be thought of as having an important role in the construction of strategy by alleviating the built-in problem of it. As strategy is aimed at promoting an illusory singular order through planning, which would require participants to become accomplished in suspending disbelief and being able to fantasise positive futures, heroic outcomes and defining victories (MacIntosh and Beech Citation2011), numerical information provides for strategy an alleviation of its profoundly illusory nature. At the very least, numerical information may be seen to offer a partial relief of the uncertainty of strategy by introducing supposedly rational, allegedly factual reference points for otherwise obscure and uncertain, even highly imaginary future states (cf. Burchell et al. Citation1980, Hines Citation1988, Ditillo Citation2004, Marginson and Ogden Citation2005, MacIntosh and Quattrone Citation2010, Messner et al. Citation2013).

As part of the ‘factualisation’ of strategy, actual numbers, such as key ratios, play an important role in modern organisations in both setting targets and gauging progress towards them (Kaplan and Norton Citation1996, Micheli, Mura and Agliati Citation2011). There is a craving for numbers, which are thought to indicate objectively and factually (Burchell et al. Citation1980, Hines Citation1988, MacIntosh and Quattrone Citation2010) where the organisation stands at any given time, and in relation to the goals set. In general, numbers may be more powerful in strategy work than thought of, as Denis et al. (Citation2006) have demonstrated in their study of the strategic reformation of the healthcare system. The craving for numbers may be so great that if numbers are not provided, they are made up to be able to make sense of the prevailing situation based on numbers conceived to hold true and able to forecast progress towards the ultimate goal, as will be demonstrated below in our analysis.

Fantasy and fantasising

Fantasy, unlike numerical information, has not been a typical framework in strategy or management accounting literatures. However, fantasy has gained some recognition within organisation studies and thus holds promise for strategy and management accounting literatures as well. For instance, Clarke (Citation1999) has proposed fantasy documents as a framework for preparing for crisis situations and disasters. Gephart et al. (Citation2012) have applied Clarke's framework for future-oriented sensemaking in their work on institutional legitimation. Gabriel (Citation1995, p. 479), as a renowned organisation theorist, states that the chief force in the unmanaged organisation is fantasy, and its landmarks include jokes, gossip, nicknames, and above all, stories (cf. Barry and Elmes Citation1997 for a strategy-as-story perspective). Gabriel (Citation1995, p. 479) stresses the view that fantasy can offer a method for an individual, which amounts neither to rebellion nor conformity, but to a symbolic refashioning of official organisational practices in the interest of pleasure, allowing a temporal supremacy of emotion over rationality and of uncontrol over control.

While rarely utilised in strategy and management accounting literatures, the concept of fantasy is not altogether unrecognised in either. Of the few exceptions we were able to discover, we will briefly describe the use of the concept in contributions by Clegg et al. (Citation2004), MacIntosh and Beech (Citation2011), Roberts (Citation2009), and O'Neill (Citation2006). Roberts (Citation2009), for instance, in his rather philosophical study dealing with transparency as a form of accountability, building on theorising in psychology (e.g. Freud) proposes that while transparency is seen as the remedy of all failures in regulation, and while the ideal is appealing and widely shared, complete transparency for him ‘is an impossible fantasy’. This view is shared by O'Neill (Citation2006) in her study of the ethics of communication by referring to the general embrace of new forms of control as ‘a fantasy of total control’. Clegg et al. (Citation2004) on the other hand take up the issue of fantasy in their critique of fallacies of strategic management and its Cartesian underpinnings when discussing the gap between managerial fantasy and organisational capabilities depicting planning and plans as something promising ‘a better, utopian future’ for the organisation. The previous contributions share a feature in common: they all frame fantasy in terms of it being something that cannot be obtained, essentially a fictitious state that would never be reached.

MacIntosh and Beech's (Citation2011) contribution clearly departs from the previous ones in that it treats the issue of fantasy and its representations in more detailed way connecting it with identity work of strategists as part of strategy work – strategy development in particular. They, building on strategy-as-practice thought, suggest four types of fantasies (1: helpful pairing, 2: the arms race, 3: the eternal optimist, and 4: the merchant of doom) connecting the identity of the strategist to that of others, and take, what could be termed a processual perspective on fantasies portraying their emergence as a dynamic phenomenon. While intuitively informative and appealing, the fantasy types outlined by MacIntosh and Beech (Citation2011), being formulation-oriented and concerned with the identity construction of those involved, is not best suited to facilitate analysis of construction of meaning(s) of strategy as it is being implemented, which is the focus of the current paper. That is why we next explicate our ideas regarding fantasy and fantasising aided with Ricoeur's (Citation1994) thinking for the analytical purposes of our paper.

Fantasy, which is required in the creative process of strategising,Footnote2 is produced by the human imagination. To clarify the connection between fantasy and imagination, we refer to Ricoeur (Citation1994, pp. 118–120), who distinguishes four uses for the concept of imagination. All the uses deal with the ideas of presence/absence and existence/non-existence. First, something which is absent here but present somewhere else can be called/brought to be here through the imagination. Second, some things (e.g. artwork), which have physical existence here, can function to represent something which is existent somewhere else. Third, through imagination we are able to bring images which are not only absent here, but also non-existent elsewhere to our minds. This is exactly what fiction does: it creates scenes, events, and landscapes that have no present and physical existence anywhere. Fourth, imagination makes illusion possible. In a certain incident it is possible to create phenomena, which call for the present audience to believe that they are reality.

Of these four uses outlined by Ricouer (Citation1994), we would like to maintain the following issues. First, plans, figures and various other documents and artefacts brought about by strategising exist here and now, but represent ideas desired to be realised in the future (the second use of imagination outlined by Ricouer). Second, considering strategising as a creative process, as we do here, imagination is an essential part of it. Because strategising is always future oriented, and the future is unknown, we have no other choice but to imagine it. In strategising it is a matter of creating future scenes and events, with no existence anywhere (the third use of imagination outlined by Ricoeur). Third, strategic fantasies need to be ‘sold’ to the members of the organisation to build commitment for the strategy to be implemented. The fourth Ricoeurian use of imagination suggests that imagination enables the creation of an illusion making the realisation of the fantasy plausible. Thus, imagination in this sense helps to merge different associations of strategy into a shared fantasy – inter-subjective meanings close enough to allow coordinated action (cf. Maitlis and Christianson Citation2014, pp. 66–67). Moreover, all of these issues leave the question of the realisation of the products of imagination unresolved, leaving the future state of fantasies created by imagination in strategising open.

Furthermore, dictionaries define fantasy as: (1) ‘something that is produced by the imagination: an idea about doing something that is far removed from normal reality’ (Merriam Webster) or as: (2) ‘the faculty or activity of imagining impossible or improbable things’ (Oxford English Dictionary). The former definition does not exclude the possibility of fantasy becoming real while the latter explicitly emphasises the impossible or improbable nature of such imaginings portraying it as ‘pure fiction’.

Gabriel's (Citation1995) orientation towards fantasy above is in line with Merriam Webster's definition, having a rather positive tone in regard to fantasising. Weick, however (Citation2001, p. 462), unlike Gabriel, warns us not to mix fantasy with plausibility. Therefore, it could be argued that Weick displays a traditional, functionalist orientation to fantasy and fantasising that is also reflected in the Oxford definition above.

Gephart et al. (Citation2012) discuss distinguishable forms of fantasy in organisational sensemaking. They propose two general types of planning: functional and symbolic.

Functional planning … requires a meaningful history to estimate probabilities of events. If decision makers cannot assign definite probabilities to events, planning becomes symbolic and ‘fantasy documents' are often created since events are uncertain. Fantasy documents are imaginative fictions about what people hope will happen. One cannot know if the promises made by the documents can be fulfilled until … plans are implemented. Thus fantasy documents are a ‘form of rhetoric, tools designed to convince audiences they ought to believe what an organisation says' (Gephart et al. Citation2012, p. 283)

We can assume that different levels of management will use different kinds of rhetoric in order to manage, control, and persuade various organisational members.

As becomes apparent from the previous discussion, fantasy has several meanings and applications in the literature. Hence, as a synthesis, we have decided upon a particular operationalisation of fantasy to support our analysis on strategy implementation. The two distinguished definitions used in this study are as follows:

Fantasy as eligible reality: A desired status quo, which at the moment is far from present reality, but for which there is no apparent reason for stopping it from being realised, hence this sort of fantasy holds probability of being actualised and the fantasy thus appears plausible.

Fantasy as utopia: A desired but purely imagined reality; a fabulous dream, which is impossible to materialise and hence the fantasy appears implausible.

To sum up, for the purposes of this study we use the term fantasy document to describe strategy, and fantasising to describe its implementation. Furthermore, fantasising can be distinguished in two forms of planning: functional and symbolic.

Methodology

The research strategy chosen for this study is an interpretative case study, more specifically, an embedded single-case design (Yin Citation2009, p. 46). This methodological choice is deemed appropriate for the current study on the grounds that the case study method is suitable for situations characterised by (1) the type of research questions posed (how, why), (2) the extent of control the investigator has over actual events (none), and (3) the degree of focus on contemporary events (on-going) (Yin Citation2009, p. 8). Moreover, the case study as a methodological choice has gained increasing acceptance and an established position within both the management accounting (cf. Ahrens and Chapman Citation2006, Kakkuri-Knuuttila et al. Citation2008, Lukka and Modell Citation2010) and strategy as practice literature (see e.g. Kornberger and Clegg Citation2011, Sugarman Citation2014); therefore, connecting our study to established research traditions in the field.

Case organisation and empirical data

Our case organisation is a fairly large financial institution located in Finland, Helsingin OP Bank Plc (hereinafter HOP Bank). It is part of the OP-Pohjola Group Central Cooperative (hereinafter OP-Pohjola), Finland's largest financial services group employing some 12,000 employees with total assets of 99,769 billion EUR (OP-Pohjola annual report 2013). HOP Bank is the single largest bank within OP-Pohjola, employing over 700 people.

Having secured access to the organisation, the research team ventured out to find out how the members at different levels of the organisation made sense of HOP Bank's strategy, values, strategy communication and goals. Early on in our interviews it became clear that HOP Bank had one ultimate strategic goal: that of becoming the leading bank in the metropolitan region in 2025. This goal was openly declared, and therefore, it became the centre of attention in our initial round of interviews within HOP Bank as the theme popped up in almost every interview.

We conducted altogether 23 informant interviews in two rounds between December 2012 and February 2014 covering all organisational levels: OP-Pohjola Group top management (hereinafter Tier 1), HOP Bank top management team (Tier 2), middle management (Tier 3) and the operative personnel (Tier 4). All the interviews were conducted in the offices of the informants or otherwise at the premises of HOP Bank and its branch offices. To select our informants, we resorted to purposeful sampling (Patton Citation2002) to include in our data organisational members from all echelons involved in strategising. The method used to identify the informants was the snowball sampling procedure (Laumann and Pappi Citation1976), where the initial interviewees, representatives of the senior management of HOP Bank were asked to identify individuals representing both Tier 3 and Tier 1 for further interviews. Tier 3 representatives then were further asked to identify Tier 4 individuals to be contacted for interviews. All interview candidates identified through the snowball method agreed to be interviewed. The interviews lasted from 20 minutes to 1.5 hours each and were audio recorded resulting in some 30 hours of interview speech and 466 pages of transcription text (single spaced). The identity of each interviewee is hidden and codified for ethical and confidentiality reasons. An overview of the empirical data is presented in .

Table 1. An overview of empirical data.

The themes in the semi-structured interviews related to the work history of the interviewee, the description of organisational strategy (emphasising the interviewee's subjective perspective), the meaning and role of numerical information in organisational strategy, the communication of strategy within the organisation and the forms of influence used by the management in their effort of making the strategy known within the organisation.

Besides interviews, we were provided the official strategy documents (altogether some 40 pages), which were used in the analysis. However, since the information is strategic and partially confidential, the key ratios and any actual figures presented to the research team or appearing in interviews have been modified.

The data analysis was organised in two separate phases. In preparation for codification and to avoid misinterpretation of the data, each transcript was read thoroughly by all the researchers involved, thereafter the research team held a group discussion regarding the interview, and at that point interpretations were cross-checked between the researchers. We then compared data from other interviews to identify similarities and differences. Only after this did the research team codify the data using the Atlas.ti software (ver. 7.5.2). Thus, in the first phase, before and during the codification, we circulated the data within the research team in several rounds with a view to making sense of the material in order not to miss anything of importance in our data with regard to the coding scheme to be followed. In the second phase, we further analysed the content of the data based on the codes chosen, focusing particularly on the meanings associated with strategy and the role of numerical information. By utilising the tools offered by the Atlas.ti software we were able to condense the data mass and make it more readily available for further detailed analysis by distilling interview excerpts with most relevance for our research purposes from the otherwise extensive transcription. Hence the first phase of analysis could be understood in terms of qualitative theme analysis while the latter phase was about qualitative content analysis since this involved a deeper interpretation of the data (Eskola and Suoranta Citation1999, Boje Citation2001, Eriksson and Kovalainen Citation2008).

Analysis of strategy implementation – fantasising in action

The analysis is structured as follows: we first introduce the official strategy and outline how narration as emplotment, and numerical information as means of legitimation are involved in fantasising. We next address the variation in meaning construction related to the official strategy referred to as unified diversity and divergent unity to establish how the meanings evolve as strategy is being implemented.

Setting the scene: the official strategy of HOP Bank

To establish our analysis of the discourse on strategy, we will briefly outline the most important elements of the official strategy statement of HOP Bank as it serves as a starting point for our analysis and discussion. The official strategy statement of HOP Bank is essentially a carbon copy of that of OP-Pohjola with only one important specification noted below. OP-Pohjola's strategy has been publicly disclosed and the key elements are therefore described here (OP-Pohjola Citation2014):

Mission: We promote the sustainable prosperity, well-being and security of our owner-members, customers and operating regions through our local presence.

Core values: A people-first approach, Responsibility, Prospering together

Goal: We are the leading financial services group in Finland. We will grow faster than the market rate.

Customer promise: We offer the best loyal customer benefits.

Competitive advantages: Comprehensive financial services offering, best loyalty benefits, close to customers, cooperative basis, Finnish roots, stability

The only differences to the above in the strategy statement of HOP Bank are related to the important regional role of HOP Bank within OP-Pohjola and a set date.

Goal: We are the leading bank in the metropolitan region in 2025.

Narration and numerical information – central vehicles of fantasising

We begin by addressing how narration and numerical information appears in language use related to strategy implementation (i.e. fantasising) within the organisation. A member of top management team of HOP Bank (Tier 2), Manager 2 explains the use of an illustrated narrative, which he had utilised repeatedly as a vehicle of discussion in internal annual operating planning meetings (integral part of strategy implementation of HOP Bank) to communicate the ultimate strategic goal – becoming the leading bank in the metropolitan region in 2025 – to the members of the organisation.

The story took about 35 minutes. The end result of it was that at the bottom [of flipchart] is 2025, and that has been so deeply inscribed in peoples’ minds over the past two years, that the date is all that is needed. They know the rest that goes with it. Then, in the middle [of flipchart] words commission earnings. And here at the top [of the flipchart] I place Loyalty Customer … the story boils down to [20]25 being the strategic goal of HOP Bank. That has not changed a bit … I began my story with the growth objective and I ended with it.

The centrality of one numerical expression – 2025 – is accentuated as the one single number needed to communicate the strategic goal of becoming the leading bank for the organisation's members. The year 2025 appears as a widely shared understanding within the organisation for Manager 2 (Tier 2), bearing strong implications and evoking directed action towards the set goal without any need to specify the details. In effect, the number 2025 seen in this respect is analogous with what Mintzberg (Citation1987) refers to as ‘strategy as perspective’: a widely shared mental frame, or ingrained way of perceiving the world. The meaning conveyed by 2025 would then assume the role of a guiding principle for the members of the organisation in the Manager 2's thinking; it is perceived to distil the essence of what is sought after by the organisation as a whole.

In addition, the excerpt above serves as an example of the symbolic nature of the bank's official strategy. As the Manager 2 himself put it, he narrates the time span for reaching the organisational goal. Hence, his illustration can be understood as a narrative – an emplotting of strategy and its implementation involving actors (the staff, other relevant stakeholders), the temporal dimension (2025) and an outcome (leading bank). In addition, the narrative contains rhetorical techniques in the domain of accounting: commission earnings are used for legitimation and concretisation purposes: widely used accounting terminology (forthcoming earnings and the consequential remunerations to the staff) are resorted to in order to add the plausibility of the sought-after sensemaking within the organisation as suggested by Thurlow (Citation2010) to get things done. It appears that while the intention of the Manager 2 was to resort to a functional approach to fantasising, above all, the excerpt is about symbolic planning. Functional planning would require a meaningful history to estimate the probabilities of events; however, when the situation does not permit that due to the uncertainty and ambiguity brought about by a long time horizon, symbolic planning assumes its place (cf. Clarke Citation1999).

Another illustrative example of how numerical information and narration are intertwined in fantasising comes from middle management (Tier 3). A middle manager in the corporate customer banking business line aims to concretise the milestones towards 2025 for subordinates. Since the middle manager feels that it is too far in the future to have any concrete meaning, s/he resorts to ‘making up’ numbers in an attempt to make the goal more comprehensible. The middle manager, for instance, uses ratios (e.g. annual growth, turnover) – established management accounting concepts – in the attempt.

If I think about the issue of being the leader from the corporate customer banking perspective, it's not that clear … I have tried to piece it together so that if our business volume in my own business unit is a bit over [x] billion, for us to be the leading bank in the metropolitan region that would mean it would need to be at least three-fold in 2025 … I even break the total to individual account managers so that they know what I am expecting from them on a yearly basis.

Therefore, in this case, the narration is about emplotting long-term goal attainment by providing ‘concrete’ measurable milestones in order to maintain within functional realm regardless of some of the figures and ratios utilised being rather imaginary. According to the middle manager's colleague, and also superior such numerical information, in fact, does not exist yet, since the management information system (MIS) does not contain all the relevant information required for such calculations. Furthermore, another manager at HOP Bank (Tier 2) working with financial data, Manager 3, also recognises that the numerical information used for future-oriented purposes is not absolutely true and accurate. This, however, does not necessarily undermine its importance for fantasising, as numerical information, while containing assumptions and best guesses, holds plausibility and Manager 3 (Tier 2) seems rather convinced that this applies to the middle management (Tier 3) as well.

… now, if you start making forward-looking calculations or finding justifications for your arguments, they always inevitably contain assumptions, so that they are not anymore necessarily fact. They are only best estimates of what may happen and what you should do … it is the best estimate of how by doing this the bank will reach its goal. We are talking about annual goals here. In the next forum the discussion is on how, by achieving these goals this year, we are able to move toward the ultimate goal. All this should be well known at middle management [Tier 3] level; that all these [forward-looking calculations] are simply best guesses about what we should be doing.

Therefore, it appears that forward-looking calculations in combination with attempts at formal planning would be important pieces in the puzzle of laying out the steps towards becoming the leading bank in the metropolitan region in 2025. Next, we will focus on the meanings associated with the target (the ultimate goal) itself.

Unified diversity? The leading bank in the metropolitan region in 2025

During our initial round of interviews, when asked about the central theme in HOP Bank's strategy, many of the middle managers (Tier 3) could cite the ultimate strategic goal of the official strategy word for word, or at the very least, the central idea.

… the strategy of ours, becoming the leading bank in the metropolitan region in 2025, has concretised for many of us the fact that OP-Pohjola as a group cannot do well without us becoming the leading bank … But still, we are quite small here [in the metropolitan region] and it's here where the growth has to happen.

While the strategic goal appeared to have been somewhat unanimously accepted among Tier 3 interviewees, some hesitation was still evident whether the strategic goal was HOP Bank's or that of OP-Pohjola as is evident in the following remark from a middle manager:

… really, no-one knows more about the strategy. We know what the strategy of OP-Pohjola as a group is; that both private banking and merchant banking are the focus. What that means in practice, no-one knows, it's all hazy.

Given that HOP Bank's strategy statement is essentially identical with OP-Pohjola's declared official strategy, confusion is not inconceivable. However, despite the critical tone, the middle manager's (Tier 3) statement above about the group's strategy being known would indicate the ultimate strategic goal having been received and not questioned. What is put in doubt is by which practical means it is to be achieved, as the path and intermediate steps towards it remain abstract and unspecified at the middle management level.

Not only had the leading bank idea penetrated the middle management, but Tier 4 representatives also echoed the central message.

… we have this strategy, leading bank in 2025, so growth is what is sought after, and that has been pretty well hammered into our brain.

The evident conviction reflected in a high-ranking HOP Bank officer, Manager 1's (Tier 2) statement of this being the case appeared to be well-founded:

… the leading bank in the metropolitan region, that is known by everyone here, that's how all presentations start … the leading bank in the metropolitan region in 2025 and all activities are aimed at it.

With only a few discomforting notes to the rather unified perception of the leading bank as the future state of HOP Bank, diversity in perception of the stated goal appeared only as a rare exception to the rule. At all levels of the organisation the ultimate goal of becoming the leading bank in the metropolitan region in 2025 appeared somewhat inevitable and was not questioned. Therefore, perceptions related to the ultimate goal appeared to be in line with type 1 fantasy in our typology (eligible reality). It would thus appear, based on the above, that the symbolic planning aspect of the official strategy had been effectively communicated throughout the organisation.

Divergent unity? Seemingly uniformly shared conception frays at the edges

When digging deeper to understand what the conception of ‘leading bank’ carried with it, and how the organisation would be able to gauge progress towards the stated goal, interesting variations in perceptions began appearing at different organisational levels, and especially, between lines of business.

As noted above, we were gradually awakened during the first round of interviews to the fact that while the idea of the ‘leading bank’ appeared to be of paramount importance within the organisation in relation to its future state – almost a cherished artefact – its meaning remained obscure and vague. Initially, we assumed we had just overlooked the obvious, and so, returned to the theme during the second round of interviews with the intention of simply finding out what exactly did leading bank mean for the organisation's members.

However, contrary to our expectation of ‘finding out a simple overlooked fact’ the recurrent strategic goal-related discourse began to take varying shapes as we drilled in on what the conception of being the leading bank in 2025 means exactly. As the excerpts below demonstrate, even within the upper echelons of the organisation, the concept of leading bank started blurring and took varying meanings at least partially appearing to emerge from the context of each different business line.

Excerpt, Manager 1 (Tier 2):

… it's not an explicit definition, and it can't be, because we would need to chop it up first – the leading retail bank or the leading private bank, or the leading bank in personal customer banking or in corporate customer banking? For us it means that we are the leading bank in the metropolitan region in 2025 when our market share in personal customer banking business is larger than Nordea's [market leader].

Excerpt, Manager 2 (Tier 2):

In plain Finnish it means that we are also the biggest actor here, and the size is measured whether or not we are considered the primary bank for our customers. And bank means also the insurance company. The leading bank 2025 is an excellent crystallisation in my opinion. Its weakness is the word ‘bank’; it obscures the importance of insurance, and that's why my message is that the leading bank 2025 means that we are the largest actor here [metropolitan region], we are the biggest insurer, and we are the biggest bank … if I were to walk a kilometre from here, and asked everyone passing by what's your primary bank or insurance company, I would accept such answers as co-operative bank, HOP Bank, even Pohjola will do, also Poutiainen's ears [reference to a common anecdote], or right colour [orange] would do … More often than Nordea. That's the indicator that counts.

Excerpt, Manager 4 (Tier 2):

Now, that's an excellent question – I don't know, because no one else does either. It's a highly subjective issue … if we are perceived by the customers to be their primary bank … if customers don't name us when asked about their primary bank, then we are not the leading bank. If we ourselves think that we are the leading bank just because we have shovelled out money through doors and windows, nothing good will result from that in the long run.

The defining features of ‘leading bank’ assume different characteristics: perceived variably as verifiable by market share, relative size to main competitor, or even something as abstract as individual customer perceptions. The ease or difficulty in defining how leading bank is to be made sense of appears to be attributable to differences in the everyday realities faced by the business lines: the social context of business line seems to bring about varying flavours.

When analysing the three perceptions above in terms of fantasising, both functional and symbolic planning surface. The Manager 1 builds on functional, accounting and numerically centred conception of the issue by resorting to alluded market share figure and comparison to the main competitor. The Manager 1's perception appears to be sensitive towards business lines’ differences. The Manager 2 embraces at first rationally oriented approach highlighting measuring in terms of size. However, despite of the early functional appearance, the perception turns out to be rather symbolic as the actual indicator alluded to (customer's primary bank) is not possible and even intended to be measured and defined explicitly, but is metaphorical, displaying fantasising in symbolic mode. The Manager 4's excerpt displays fantasising in symbolic realm in its ‘purest’ sense as the manager does not even make an attempt to resort to functional approach, but openly admits there is no way of measuring such matters as subjective interpretations of individual customers, thus creating an interesting exception among top management (Tier 2) informants.

The differing social contexts and their implications appear to be especially clearly present in how private banking is talked about in relation to the leading bank concept by the Manager 2 and another top management team member representing the private banking business line (Manager 5).

Excerpt, Manager 2 (Tier 2):

In private banking it [leading bank] has been crystallised slightly differently … the owner will tolerate us not being necessarily the absolute biggest, but we have to be around the same level that the biggest operators roam … in private banking slightly more room has been left. That's because there we have the biggest handicap. Nevertheless, a very ambitious growth target has been set for private banking also.

Excerpt, Manager 5 (Tier 2):

… we are now, you could say the size of a mosquito, if we now have less than [x],000 private banking customers … we are miniscule compared to Nordea. So if we managed to reach some 60% of their customer count, then I would consider us noteworthy. At that point we have visibility in the market and we will be talked about in the metropolitan region … to be noteworthy we need to get this close to Nordea [referring to a presentation slide].

Even if the ultimate strategic goal of becoming the leading bank in the metropolitan region in 2025 was, in principle at least, common to HOP Bank as a whole, the top management was clearly willing to cut private banking some slack with respect to the ‘leader role’ in this particular business line, as both the Manager 2 and senior manager of private banking, Manager 5, eased up on the goal of being the leader in this business line in 2025. Instead, moderation in the use of the term leading was made: ‘noteworthy’ replaced leading to describe private banking's aspired status in 2025.

The need to moderate goal setting was justified by the Manager 2 and Manager 5 by describing HOP Bank's private banking (backed up by numbers for added plausibility) as the underdog in need of serious catch-up efforts with relation to its main competitor. This discourse is an example of how accounting-based numerical information influences strategy-related sensemaking as suggested by Jordan and Messner (Citation2012), and how they may be used as a rhetorical technique for legitimising a claim or its suggested ‘factual’ base. In this instance, the numbers are used as a vehicle of persuasion for the utopian nature of the fantasy of becoming the leading player in private banking in the metropolitan region (i.e. in the sense of type 2 fantasy: fantasy as utopia, in our typology). As the goal seems outright unattainable in the given timeframe due to such a sizeable competitor, the leading rhetoric is replaced with less definitive rhetoric justifying the likelihood of nonconformity with the goal well in advance.

This is in clear contrast with the perception of a high-ranking officer at OP-Pohjola (Tier 1) who outlines HOP Bank's ultimate strategic goal to be the leading bank in all business lines, while some hesitation with regard the ‘due date’ is expressed:

… being the leading [bank] in our different business lines – market shares, they need to be number one … at some point that means that HOP Bank also needs to be the number one in every single business line.

However, another Tier 1 representative at OP-Pohjola (Manager 6) resorts to a different kind of elucidation for the meaning of the ultimate strategic goal, being the leading bank:

… it is about gaining and retaining mental air supremacy.

These two statements clearly represent different rhetorical means: the former is more rational, explicit and established also in terms of accounting; market share appears more concrete and objective, something which can be measured. However, the latter represents rather metaphorical rhetoric with reference to air warfare.Footnote3 Gaining or retaining mental air supremacy is by no means possible to be measured, neither is it intended to be. As the manager describes, the idea of strategy is about addressing the direction of actions among all organisational members. Both informants above ranking among those formulating the official strategy of HOP Bank makes their statements important in the following respect: the different perceptions reflect the fantasy nature of the official strategy. The former represents functional planning, while the latter is clearly symbolic in nature.

While the date 2025 appeared to be widely received and well-remembered by the interviewees at all levels, giving the year 2025 the appearance of an unquestioned future state against which all development would be mirrored within the organisation, the perceived absoluteness of the temporal dimension received a less fixed definition from the Manager 6 (Tier 1), as he explains:

… a given year [2025] was set to mark the time by which we want to achieve the goal. It really doesn't matter if the goal is reached in that exact year. 2025 is there more to symbolise that we believe the goal is achievable within some reasonable timeframe.

Therefore, while the rest of the organisation had perceived the year 2025 rather unanimously as ‘a binding contract’ by which date the ultimate strategic goal had to be realised, the year 2025 appeared to be just part (albeit a very central one) of the overall organisational narrative; that of becoming the leading bank. The central role in the fantasy was offered to HOP Bank from the top by the owner, OP-Pohjola, as an inspiring long-term future state, perceived widely as an eligible reality to realise through the strenuous effort of the organisation.

Eisenberg (Citation1984) has proposed that ambiguity can be used strategically to foster agreement on abstractions without limiting specific interpretations. While the recurring theme of the leading bank appeared as if it might have been deliberately created to contain ambiguity to leave room for both individual and organisational sensemaking – our initial impression – this clearly was not the intention at HOP Bank. Instead, the top management had undertaken a painstaking exercise in the form of a strategy road-show throughout the organisation visiting every single HOP Bank branch office during spring 2013 in order to communicate the strategy in as unified a form and with as coherent a message as possible.

While the intention of the strategy road-show may be inferred to have been to force a unified idea of the strategy and strategic goal – essentially the top management's perception – onto the rest of the organisation in a traditional top-down fashion, the intention was not fully realised, however. Again, the symbolic aspects of the official strategy (e.g. leading bank, fixed timespan) would appear to have been rather effectively diffused within the organisation as the goal of becoming the leading bank seemed unquestioned at all levels of the organisation. In terms of the functional aspects of the official strategy, the question of what constitutes a leading bank seems particularly challenging (or even impossible) to delineate. How is the organisation to know whether or not the leading bank position has been attained (i.e. how to measure and verify it)?

As discussed above, the leading bank concept remained relatively constant during both rounds of interviews, and as such, the constancy reflects the aspect of unified diversity. However, as will become evident with the following excerpts from the second round of interviews, the middle management interviewees clearly add their own flavour to the concept of leading bank. This reflects the aspect of divergent unity in fantasising: the attempts to operationalise the symbolic aspect of strategy into more concrete terms by resorting to functional rhetoric and terminology. Multiple conceptions surface here related to cues by which the target of being the leading bank would emerge as actual or imminent as reflected in the following excerpts of middle management (Tier 3).

Excerpt, Tier 3 (personal customer banking):

That means that, in market shares, customer volumes, we are the number one here [metropolitan region]. Growth is what we're after, in both business lines and customer volumes … Now, what does the leading bank mean – it means that we have achieved the goals set to us, that market shares in different business lines are at the level we want them to be.

Excerpt, Tier 3 (private banking):

Leading bank most likely means that our market shares should be on track, and also customer volumes … our market share is somewhere below [x]0% and Nordea around 45%, so that's our target to nibble away … currently we have something like under [x],000 customers, so we need to get to closer to [x]0,000 customers if we want to be the leading bank in private banking [in the metropolitan region].

Excerpt, Tier 3 (corporate customer banking):

[Leading bank] means that the customers perceive us to be their primary bank. That's what it means in my opinion … market share, how customers see it … we must hold 51, or 50.01 share to be the leading bank. Or rather, a bit thoughtless of me, just the largest market share is enough. Like if we now have [xx] and Nordea has 60, that needs to be reversed.

For middle managers, the signification of leading bank emerges pronouncedly through market share in different business lines, trailed by size of customer base, and business volume, again backed up with numbers to gauge against the main competitor in the metropolitan region. For middle management (Tier 3), the numbers clearly play a more important role in making sense of the ‘leader’ concept than for the top management as a means of concretising strategy and directing action towards goal attainment. Thus, numbers appear to be a highly important means for middle managers to relate the organisation to its main competitor against which all activities are directed in order to accomplish the ultimate goal of become the leading bank in the metropolitan region.

Furthermore, to add still another layer in the construction of meanings of the strategic goal we present some excerpts of the operative personnel (Tier 4).

Excerpt, Tier 4 (corporate customer banking):

… it [strategy] has been said, or the leading bank has, I really don't know if it is the same as the biggest, may not be … Because we are most likely not able at any time to be competing in terms of size with Nordea or Danske Bank, but anyhow, here in our own [metropolitan] region we want to be one of the leaders in corporate customer banking.

Excerpt, Tier 4 (private banking):

What else goes into the strategy, that's not too well known, but the big picture at least is. And that's growth, and we have a set date for being the biggest … Most likely that springs out of the strategy that growth is a must. To be the most successful in Finland, the biggest bank in the metropolitan region in 2025, we must achieve growth. And what's the driver behind growth? … personal targets set. How they are reached gets monitored on a weekly basis.

As the excerpts above reveal, the link between strategy and daily operations appear somewhat thin judging from the front line. Nevertheless, target-related numerical information appears as an important vehicle for the fantasising in action due to the perceived factual and objective nature of numbers. Numbers offer justification for the necessary activity for achieving the leader status in the metropolitan region although their actual reference point is constantly moving, and to certain extent, fictional. Thus, it appears that the further down in organisational hierarchy one is, the more functional fantasising takes place: the daily operative reality is where strategy becomes ‘real’ and ‘materialised’ through activity (e.g. following personal targets set in Excel sheets), which eventually either brings or does not bring about the aspired future state of the organisation.

Despite of the fact that staffers repeated the ultimate goal word for word, the symbolic aspects of fantasising, however, remain distant and blurred for them. While the symbolic fantasising aspires to act as an inspirational framework towards the goal, there is a risk of it getting ‘mechanically’ repeated and becoming constant refrain, ‘the same old story’, only (cf. Boje Citation2003). The staffers cannot see the connection between functional and symbolic fantasising since symbolic fantasising lacks substance in the form of figures and numbers appearing instrumental for them to make sense of it. Although micro-level activities springing out of strategy-related sensemaking are of utmost importance in achieving the goals of any organisation, it is most often neglected in strategy research (cf. Mantere Citation2005). The understanding of fantasising on why and what needs to be done in daily work to accomplish the goals is of instrumental importance for the functioning of organisations.

Discussion and conclusions

The strategy document in this study is understood as a fantasy document involving two forms of fantasy, (1) eligible reality; prospective future state of affairs and (2) utopia; desired but unlikely to be realised future state of affairs. Furthermore, in this paper the implementation of strategy is referred to as fantasising taking place via two forms of planning: (1) functional and (2) symbolic. The functional form refers to traditional, rationally oriented strategic planning (cf. Mintzberg Citation1994) that typically focuses on the use of numerical information (e.g. key ratios such as growth rate, market share). Apart from numerical information, the construction of meaning of strategy needs symbolic communication involving narration (emplotment) which typically assumes such devices as visioning, metaphorisation and inspiring organisational members to move towards a common goal. Unlike functional planning, symbolic planning has no explicit reference point and cannot be verified in terms of numerical information. Both functional and symbolic forms of planning are intertwined in fantasising – directing the organisation towards the set goal by creating necessary action and activity at all levels, that is, strategy implementation.

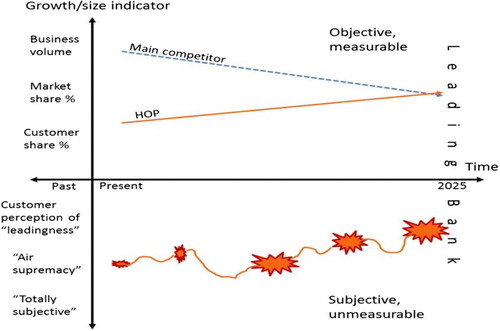

To illustrate our findings related to strategy as a fantasy document and strategy implementation as fantasising, we have condensed them into . In it, the X-axis indicates temporal horizon, while the Y-axis displays indicators perceived to reflect the ultimate goal sought by the strategy, and the ‘level’ of its attainment springing out of our analysis as constructed by the informants. Above the X-axis are the conceptions assuming more objective and measurement-oriented indicator forms of what a leading bank consists of (functional form), while below it are the indicators assuming unmeasurable, subjective conceptions among organisational members (symbolic form). We will utilise as a vehicle for discussion in what follows to explicate our findings further.

By and large the meaning construction related to strategy may be seen as storytelling since there is a certain temporal dimension (time span, 2025 in this case), actors (such as organisational members, the organisation itself, main competitor), a plot (growth; overtaking the main competitor) and the end (aim; becoming leading bank within the time span). The overall story is embedded with myriad of rational elements. Numerical information, such as accounting figures, are needed and used mainly in two senses.

First, as outlined by interviewees, numbers in a bank are simply needed; for instance, to bring about credibility and perform a legitimate role while proclaiming ideas and also for leading people. Second, as the body of management accounting literature postulates (cf. Bhimani et al. Citation2012), numbers in general are needed in organisations for the purpose of identifying current progress, to locate the present standing in relation to the market and the main competitors, and also to conceive, determine and concretise the operations needed to reach the goal, among other things. The importance of numerical accounting information for fantasising is twofold: first, micro-level ratios themselves in isolation have little relevance in terms of the ultimate goal of the organisation (becoming leading bank in 2025), but the micro-level phenomena become understandable by reference to meso-level or macro-level structures or systems (such as Basel III regulation). We too suggest that by connecting the micro and macro level explanations in future studies, as proposed by Seidl and Whittington (Citation2014), combining flat and tall ontologies in empirical research would take the strategy literature a step forward.

Second, numerical accounting-based information has importance for functional planning in such occasions as annual operating planning meetings and strategy road-shows by the top management emphasising functional planning backed up by what is generally perceived as rational, objective accounting figures. This is the part of fantasising Clarke (Citation1999) calls imagined planning documents aimed to stimulate short-term activity. However, when it comes to the ultimate goal (leading bank in 2025) in our particular case, the time span is more than a decade making assigning probabilities to such far removed future events impossible. This is why the nature of such far-reaching plans become symbolic and the persuasiveness of accounting figures fade and their place is assumed by, for example, metaphors that carry more powerful messages regarding the aspired future than numbers.

However, despite the human tendency of receiving ‘numbers talk’ in rational, objective and factual terms, many numbers utilised in strategising are not true per se or even perceived as such by those using them as revealed in the analysis. Therefore, our study, which builds on earlier works by Burchell et al. (Citation1980) and Hines (Citation1988), contributes to recent micro-oriented management accounting literature (Ahrens and Chapman Citation2007, Chua Citation2007, Boedker Citation2010, Jörgensen and Messner Citation2010, Skaerbaek and Tryggestad Citation2010, MacIntosh and Beech Citation2011) by providing the concept of a fantasy document having two forms, functional planning and symbolic planning, and exploring the role of numerical accounting information as a rational technique in providing a sense of plausibility for strategy interwoven with storytelling. Addressing these issues help us better understand how the conception of strategy evolves in the implementation process, and how numerical information and storytelling are deeply intertwined in attempts to amplify the message contained in an official strategy and to concretise the abstract.

While in terms of hierarchy the ultimate goal of becoming the leading bank had penetrated all levels of the organisation, the fantasising itself differs to some extent. According to our findings, top management (Tiers 1 and 2) resorts more often to symbolic planning rhetoric and makes use of widely metaphorical indicators (e.g. ‘mental air supremacy’). Middle management (Tier 3) on the other hand resorts to functional planning rhetoric in order to make things happen and gauge progress, while operative personnel (Tier 4) utilises micro-level numeric information due to the nature of their daily work, being filled with Excel sheets and score cards guiding activity, and consequently, conceptions of strategic goals (cf. Burchell et al. Citation1980, Hines Citation1988, Jörgensen and Messner Citation2010, Kaplan and Norton Citation1996, MacIntosh and Quattrone Citation2010, Micheli et al. Citation2011). Thus, for the Tier 3, and above all for Tier 4 representatives, the management accounting-based numerical information plays a pivotal role in their daily activities and in their attempt of understanding their relation to the goals set in the official strategy: numbers, in the form of weekly, monthly, or quarterly personal targets assume the role of strategy as the guiding principle of daily work. The connection of the personal targets, official strategy, and the strategic goal, however, seems hazy at best.

Overall we may infer the fantasy nature of HOP Bank's official strategy to be mostly of type 1: fantasy as an eligible reality, in our typology, for which there is no apparent reason stopping it from realising. While challenging and stretching, firm belief in its attainment was present, and the fantasy remained coherent throughout the organisational hierarchy. The coherence of this fantasy, however, is challenged horizontally between business lines. The most important exception we are able to discern, and take to represent the simultaneous existence of the two types of fantasy is the way the private banking business line becoming the market leader was narrated. Private banking becoming the market leader is a case in point of the type 2 fantasy – a utopian and imagined future state which is impossible to realise. This future state was generally perceived as impossibility.

While we find both types of fantasy simultaneously present, and seemingly they contradict one another in a way that would appear to cause the fantasy as a whole to crumble, this clearly is not the case with HOP Bank. By utilising Weick's (Citation1995, Citation2001) ideas as they relate to sensemaking, we are able to fathom why. As Weick (Citation2001) explains, sensemaking is about the construction of meaningful events encountered in the world by people: it is driven by plausibility rather than accuracy. It is about coherence: that is, how events hang together. It is also about the certainty that is sufficient for existing purposes and credibility. Thus, human beings do not rely primarily on accuracy when making sense of an event.

Weick's idea may be extended to fantasising in our case. While we are able to find contradicting elements in the overall fantasy of becoming the leading bank – private banking being referred to as becoming ‘noteworthy’ instead of leading – this contradiction does not seem to make any noteworthy fracture in the overall fantasy. Instead, the overall story of becoming the leading bank hangs together supported by other plausible cues offering it credibility and perceived certainty for the members of the organisation for the existing purpose of mapping out the otherwise unknown future by establishing it as the almost ‘inevitable’ future state outlined in the official strategy. In the case of HOP Bank too, strategy-related or prospective sensemaking in the form of fantasising may thus be said to be driven clearly by plausibility, not accuracy, as suggested by Weick (Citation1995, Citation2001). Moreover, while Weick (Citation2001) recognises fantasy, it is treated as something to stay away. However, we would suggest acknowledging fantasy and fantasising as part of the sensemaking framework instead of shutting it out could open up new research avenues for sensemaking research making it more sensitive to implications of imagination and prefactual thinking (MacKay Citation2009) on sensemaking.

While the top management aimed at ‘forcing’ a unified view of the strategy upon the rest of the organisation in a top-down fashion by delivering a strategy road-show to the furthest corners of the organisation in an attempt to reduce any ambiguity related to the strategy, this kind of managerial orientation aiming at one shared view of strategy worked almost the opposite way. Instead of forming a unified worldview within the organisation, it created the prospect for multiple conceptions within different echelons and different business lines within the bank. Both the timeline, which is rather long and hence hard to conceive for an individual human being, and the core idea of the ‘strategy/vision’ is constructed meaningful in a multitude of different ways within the organisation instead of the one coherent conception aimed at by top management.

It appears that unified diversity (Eisenberg Citation1984) was achieved in our case organisation to a significant degree unintentionally, or at the very least, counter to the intentions of the top management. The ‘story’ of the leading bank in the metropolitan region is a theme that penetrates the whole organisation. However, what constitutes a leading bank assumes multiple meanings within the organisation: ultimately organisational actors make sense and judge what is significant in their actions in relation to the ultimate goal (cf. Vaara Citation2010, Laine and Vaara Citation2011).

We may infer the highest level fantasy document being the official strategy of HOP Bank containing the central idea of becoming the leading bank in the metropolitan region in 2025 as the ultimate goal. The fantasy is narrated as plausible by resorting to both functional planning rhetoric (objective, measurable numerical information and various key ratios) and symbolic planning rhetoric (highly subjective, either hard or impossible to measure matters). Thus, in summary, we contend that strategising is on-going and future oriented (also referred to as projective; cf. Helms Mills Citation2003) sensemaking by nature, inevitably involving fantasising in both functional and symbolic form. The two are so deeply intertwined the overall fantasy contained in the official strategy cannot survive without both being present.

In essence, making sense of something that is not real in the present requires imagination (cf. Ricoeur Citation1994). Traditional approaches have esteemed more logical-rational reasoning, argumentation and objectivity, but we propose, intuition, narration, subjectivity and even foolishness (see e.g. March Citation2006) must also be recognised as important parts of strategising. In the domain of strategy, functional and symbolic planning are the intertwined and inseparable fantasising vehicles that construct and convey meanings, significance and plausibility. Strategy must resort to fantasising in order to materialise as an actual path with direction for organisational members navigating their organisation into the future.

To conclude our findings on fantasising, we refer to Mason's (Citation1969, B-403) thoughts on imagination and strategy presented nearly five decades ago, which we take to be still valid:

Man lives by his imagination. This is as true of the modern organisation as it is for the individual. The particular set of beliefs or assumptions about the world that an organisation adopts guides its activity and dictates its success or failure. This is especially true of an organisation's strategic plan.

The intricacies of present-day organisations (and life in general) make guiding beliefs and assumptions, such as those offered by strategy, of heightened importance for organisations and their members. To understand strategy as a form of fantasy created by the imagination offers us a valuable additional way of perceiving it, and opens up further avenues of exploration in the spirit pointed out by Mintzberg and Lampel (Citation1999), in seeing strategy as a creative interpretation of the future – in essence – a fantasy that can only actualise through its implementation, that is, fantasising. Strategy, however, can only be partially operationalised in functional planning using accounting numbers. What numbers can provide, however, is, combined with storytelling, metaphors, and other vehicles of symbolic planning, an important source of plausibility to provide ‘certainty’ and substance to strategy sufficient for the purpose of its execution that they alone could not. Therefore, the important component of strategy work not to be overlooked is fantasising in the form of symbolic planning.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions to improve the quality of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. By the term numerical (accounting) information, we refer to processed data entered into a database and utilized by accounting professionals. Thus, information for us is data that is endowed with meaning, relevance and purpose (Jaspahara Citation2005, see also Rowley Citation2007).

2. Strategising is used here as an umbrella concept much in the same manner as strategy work (cf. Vaara and Whittington Citation2012, p. 3) ‘to refer to more or less deliberate strategy formulation, the organizing work involved in the implementation of strategies, and all the other activities that lead to the emergence of organizational strategies, conscious or not'.

3. The NATO Glossary of Terms and Definitions explains air supremacy as ‘That degree of air superiority wherein the opposing air force is incapable of effective interference’ (NATO Citation2015).

References

- Ahrens, T. and Chapman, C.S., 2006. Doing qualitative field research in management accounting: positioning data to contribute to theory. Accounting, Organizations & Society, 31 (8), 819–841. doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2006.03.007

- Ahrens, T. and Chapman, C.S., 2007. Management accounting as practice. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 32 (1–2), 1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2006.09.013

- Barry, D. and Elmes, M., 1997. Strategy retold: toward a narrative view of strategic discourse. Academy of Management Review, 22 (2), 429–452.

- Bhimani, A., Horngren, C., Datar, S. and Foster, G., 2012. Management and Cost Accounting. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

- Boedker, C., 2010. Ostensive versus performative approaches for theorizing accounting-strategy research. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 23 (5), 595–625. doi: 10.1108/09513571011054909

- Boje, D.M., 2001. Narrative Methods for Organization and Communication Research. New York: Sage.

- Boje, D.M., 2003. Using narrative and telling stories. In: D. Holman and R. Thorpe, eds. Management and Language. London: Sage, 41–53.

- Bubna-Litic, D., 1995. Strategy as fiction. Paper presented at the Standing Conference on Organizational Symbolism (SCOS) July, 1995, Turku, Finland.

- Burchell, S., Clubb, C., Hopwood, A., Hughes, J. and Nahapiet, J., 1980. The roles of accounting in organizations and society. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 5 (1), 5–27. doi: 10.1016/0361-3682(80)90017-3

- Burrell, G. and Morgan, G., 1979. Sociological Paradigms and Organisational Analysis: Elements of the Sociology of Corporate Life. London: Heinemann.

- Chua, W.F., 1986. Radical developments in accounting thought. Accounting Review, 61 (4), 601–632.

- Chua, W.F., 2007. Accounting, measuring, reporting and strategizing – re-using verbs: a review essay. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 32, 484–494. doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2006.03.010

- Clarke, L., 1999. Mission Improbable: Using Fantasy Documents to Tame Disaster. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Clegg, S., Carter, C. and Kornberger, M., 2004. ‘Get up, I feel like being a strategy machine’. European Management Review, 1 (1), 21–28. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.emr.1500011

- Czarniawska, B., 2004. Narratives in Social Science Research. London: Sage.

- Denis, J.-L., Langley, A. and Rouleau, L., 2006. The power of numbers in strategizing. Strategic Organization, 4 (4), 349–377. doi: 10.1177/1476127006069427

- Ditillo, A., 2004. Dealing with uncertainty in knowledge-intensive firms: the role of management control systems as knowledge integration mechanisms. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29 (3–4), 401–421. doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2003.12.001

- Eisenberg, E.M., 1984. Ambiguity as strategy in organizational communication. Communication Monographs, 51 (3), 227–242. doi: 10.1080/03637758409390197

- Eriksson, P. and Kovalainen, A., 2008. Qualitative Methods in Business Research. London: Sage.

- Eskola, J. and Suoranta, J., 1999. Johdatus laadulliseen tutkimukseen. Tampere, Finland: Vastapaino.

- Gabriel, Y., 1995. The unmanaged organization: stories, fantasies and subjectivity. Organization Studies, 16 (3), 477–501. doi: 10.1177/017084069501600305

- Gephart, R.P., Topal, C. and Zhang, Z., 2012. Future-oriented sensemaking: temporalities and institutional legitimation. In: T. Hernes and S. Maitlis, eds. Process, Sensemaking & Organizing. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 275–302.

- Gioia, D. and Chittipeddi, K., 1991. Sensemaking and sensegiving in strategic change initiation. Strategic Management Journal, 12 (6), 433–448. doi: 10.1002/smj.4250120604

- Golsorkhi, D., Rouleau, L., Seidl, D. and Vaara, E., 2011. Introduction: what is strategy as practice? In: D. Golsorkhi, L. Rouleau, D. Seidl and E. Vaara, eds. Cambridge Handbook of Strategy as Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1–20.

- Helms Mills, J., 2003. Making Sense of Organizational Change. London: Routledge.

- Hines, R.D., 1988. Financial accounting: in communication reality, we construct reality. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 13 (3), 251–261. doi: 10.1016/0361-3682(88)90003-7

- Jarzabkowski, P., Balogun, J. and Seidl, D., 2007. Strategizing: the challenge of a practice perspective. Human Relations, 60 (1), 5–27. doi: 10.1177/0018726707075703

- Jaspahara, A., 2005. Knowledge Management: An Integrated Approach. Harlow: Prentice Hall.

- Jordan, S. and Messner, M., 2012. Enabling control and the problem of incomplete performance indicators. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 37 (8), 544–564. doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2012.08.002

- Jörgensen, B. and Messner, M., 2010. Accounting and strategising: a case study from new product development. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 35, 184–204. doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2009.04.001