Abstract

We discuss the concept and costs of resolving accounting issues. We first characterise the (degree of) resolution of an accounting issue as a continuous concept, arguing that an accounting issue is unresolved where an established solution is either uncertain or produces financial information with undesired consequences. We then describe standard setters and market participants as possible institutions that can contribute to such resolution. A series of standard-setting cases illustrates different settings as well as sources and degrees of resolution. We then review extant studies that speak to two important cost factors shaping the supply of accounting solutions: costs of learning about accounting solutions and opportunity costs arising from reduced incentives for innovations in accounting. We conclude with suggestions for future research and implications for standard setting.

1. Introduction

We study the concept and costs of resolving accounting issues. Accounting standard setters like the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) and the U.S. Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) provide guidance that instructs preparers how to ‘map’ their economic activities into financial information. Proponents argue that accounting standard setting provides a range of benefits, including greater decision usefulness of financial reports as well as efficiency gains, due to, for example, lower transaction costs (Meeks and Swann Citation2009, Williamson Citation1998) – relative to a situation where firms individually provide unstandardised information. Consistent with these arguments, mandatory accounting standards are pervasive, with most public firms applying either IASB or FASB standards.

However, there is a puzzle. Whereas many accounting topics are covered by longstanding and relatively uncontroversial standards, some particularly ‘vexatious and recurring’ (Schipper Citation2022) issues appear to persistently defy a standard-setting resolution. These either take exceptional amounts of time and effort for a standard to emerge; they are subject to standards deemed to be flawed; or they remain in the ‘too-difficult box’, as it were – permanently unresolved by standard setters. In this issue, Schipper (Citation2022) asks why such ‘gaps’ in accounting standards arise and persist. We complement her study by exploring to what extent accounting issues should be resolved by standard setters.

We consider an accounting issue unresolved where available solutions are either uncertain or produce financial information with undesired consequences. We propose that resolution is a continuous concept that can result from different institutional arrangements. Specifically, we argue that both standard setters and market participants can contribute to the resolution of accounting issues. They do so by developing distinct solutions (such as accounting standards or preparer-specific accounting policies) that reduce uncertainty about how a firm’s financial statements reflect its economic fundamentals and/or mitigate undesired consequences (e.g. in terms of firms’ real earnings management).

In this paper, we provide a conceptual framework that highlights the distinct contributions made by standard setters and market participants towards the resolution of accounting issues, which we link to the role of standard setters as described by the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) Foundation’s governance documents. To illustrate the different solutions provided by standard setters and market participants, respectively, we use a series of cases from the IASB’s and FASB’s standard-setting agendas. Whereas prior research has emphasised the benefits of (or demand for) these solutions (such as, constraining managerial opportunism; Fields et al. Citation2001), we focus on their cost. To that end, we review the literature on two potentially important cost factors shaping the supply of accounting solutions: (i) learning cost, which arise because preparers and market participants need to collect, process, and analyse information about possible solutions; and (ii) opportunity costs arising when the presence of an established solution mitigates incentives to innovate (i.e. to invest resources in developing novel, potentially better solutions).

Our analysis provides the following insights. First, we emphasise the distinction of an accounting solution (the discrete answer to an accounting issue, e.g. measurement at fair value through profit or loss) from the continuous notion of resolution (the degree to which an accounting solution eliminates uncertainty and undesired consequences). Second, we argue that different degrees of resolution can be achieved by different institutional arrangements. The efficient arrangement depends on standard setters’ and preparers’ competitive advantages in developing accounting solutions that mitigate uncertainty about accounting treatments and yield financial information with desired properties. For instance, higher degrees of resolution may require greater learning costs, which, compared to preparers, standard setters may be able to scale over a larger number of transactions. At the same time, preparers might face lower search costs for finding accounting solutions tailored to their specific economic activities and their stakeholders’ information demands. Third, we recommend that future studies seek to better understand the degree of resolution for key accounting issues in order to help derive standard-setting priorities, and that more research be devoted to assessing where a desired degree of resolution is more efficiently achieved via centralised standard setting versus decentralised ‘market solutions’, including preparer learning.

2. Conceptual background

In this section, we first discuss what constitutes an unresolved accounting issue, why demand for its resolution arises, and how standard setters and market participants can contribute to it. We then focus on standard setters’ role in resolving accounting issues by deriving their mandate to do so from the IFRS Foundation’s governance documents, and by discussing the relation between accounting standard design (e.g. rules-based versus principles-based standards) and accounting issue resolution.

2.1. Key concepts

2.1.1. Accounting issues and accounting treatments

As illustrated by the Pathways Vision Model (Pathways Commission Citation2015), accounting represents (the process and outcome of) ‘mapping’ economic activity (i.e. transactions or other events) into financial reports. Various types of accounting issues arise during this mapping process; these are questions about which accounting treatment (or ‘mapping rule’) to apply to a given transaction (e.g. acquisition of a crypto asset) or event (e.g. a firm’s exposure to the Covid-19 pandemic or climate change). Accounting issues differ in terms of scope (e.g. broad issues pertaining to whole classes of transactions or events such as the question how to account for financial instruments, and narrow issues pertaining to more restricted questions such as the delineation of capitalised development costs) and type (e.g. recognition, measurement, presentation, and disclosure). Some accounting issues are perceived as problematic by constituents – either (a) due to uncertainty about which accounting treatments to apply, and how to apply them (‘mapping uncertainty’), or (b) because a given accounting treatment yields financial information that has undesired consequences.

2.1.2. Mapping uncertainty

Mapping uncertainty arises, typically on the part of preparers (and, to some extent, auditors), where it is not obvious how an economic transaction or event should be mapped into a firm’s financial reports. On the one hand, it takes the form of compliance uncertainty about which among several potential accounting treatments for the accounting issue in question meet the requirements. On the other hand, in selecting from the set of permitted accounting treatments, preparer managers consider the uncertain ‘payoffs’ associated with each accounting treatment – which reflect the information needs and preferences of various stakeholders, as well as managers’ economic incentives, legitimacy and reputation concerns, compliance costs, and other objectives (outcome uncertainty).

2.1.3. Undesired consequences

We consider an accounting treatment as yielding financial information that has undesired consequences where some constituents of accounting voice concerns about the accounting treatment. These concerns can come from users (e.g. perceived lack of decision-useful information, disclosure overload), preparers (excessive one-time or recurring compliance costs, disclosure overloadFootnote1), or other constituents (e.g. several types of ‘real effects’).Footnote2 Examples of undesired consequences include concerns about the understatement of ‘true’ financial leverage under IAS 17, a key reason for replacing IAS 17 by IFRS 16; ‘artificial volatility’ in earnings introduced by fair value accounting for financial assets, which triggered the debate surrounding the IASB’s reclassification amendment of IAS 39 in 2008; ‘artificial volatility’ in equity due to the introduction of the ‘OCI’ method for defined benefit pension plans in IAS 19R in 2013; asset impairments during the financial crisis of 2007/2008 being ‘too little, too late’; ‘inflated’ goodwill amounts due to lack of amortisation and too much discretion with regard to impairment-testing requirements; overwhelming and allegedly irrelevant fair value disclosures under IFRS 7; costly IT system investments for implementing the recently revised lease accounting (IFRS 16) and revenue recognition requirements (IFRS 15); and alleged reductions in investment, economic output, and jobs due to the elimination of lessees’ off-balance-sheet accounting for operating leases (IAS 17).

2.1.4. Accounting solutions and accounting issue resolution

Mapping uncertainty and undesired consequences create demand for (accounting) solutions, i.e. answers to these accounting issues – in the form of applicable (sets of) accounting treatments that solve these problems by minimising mapping uncertainty and undesired consequences. Such solutions can be established in abstract-general form by standard setters (principles or rules that apply to entire classes of transactions or events), or by market participants (social norms, or accepted practices at the market, industry or firm level). To the extent they are not, firms will have to develop internal, case-specific solutions for the (classes of) transactions or events they face.

The resolution of a given accounting issue, then, is a continuous concept – namely the degree to which the established accounting solution successfully reduces mapping uncertainty and undesired consequences. We consider an accounting issue as unresolved to the extent that both standard setters and market participants have failed to provide an abstract-general solution that addresses its problems. Such lack of an established solution can originate because the issue is too new (e.g. accounting for cryptocurrencies), too vexatious (e.g. with no conceptually grounded solution existing, or with such solution being too difficult to implement; see Schipper Citation2022), or not important enough (e.g. because the given type of transaction is very rare) to warrant the development of a solution provided by either the standard setter or market participants. Overall, we stress that the development of some accounting solution for a given accounting issue is not a sufficient condition for its resolution.

2.2. Resolution by standard setters versus market participants

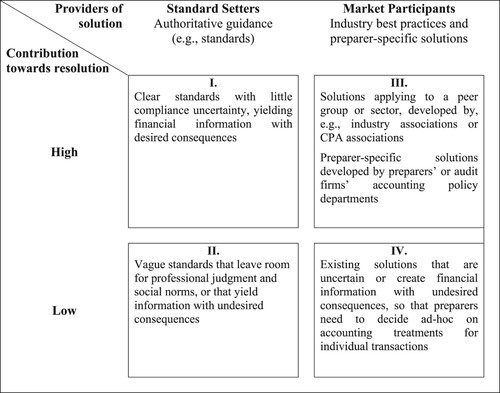

provides an overview of the institutions than can provide solutions to an accounting issue and, hence, contribute towards its resolution. These institutions comprise standard setters (left column) and market participants, such as preparers or industry associations (right column). Whereas the former provide centrally developed solutions in the form of authoritative guidance (e.g. accounting standards and interpretations), the latter provide decentral solutions, including those developed by preparers’ or audit firms’ accounting policy departments, or industry-wide solutions recommended by industry associations.Footnote3 In the preparation of financial reports, standard setters’ solutions take precedence over market participants’ solutions; i.e. the latter are ‘residual’ in that they come into play (only) where the former leave room for them.Footnote4 This follows as, even where no standard or similar authoritative guidance exists for a given accounting issue, preparers need to ultimately settle on some accounting treatment, e.g. by implementing ‘working rules’ for their day-to-day accounting practices (Kothari et al. Citation2010).

Figure 1. Providers and Degree of Accounting Resolution.

Note: This figure illustrates the different contributions towards resolution of an accounting issue made by standard setters and market participants.

Via these different types of solutions, both standard setters and market participants can contribute towards the resolution of an accounting issue. Standard setters’ contribution towards resolution will be higher in the case of clear standards with low mapping uncertainty that result in financial information with desired consequences (quadrant I in ). To the extent that standard setters leave an accounting issue unresolved, e.g. due to vague standards and/or standards that yield financial information with undesired consequences (quadrant II), there is room for market participants to contribute towards the resolution of the issue (quadrant III). These include solutions developed for individual firms (e.g. firm-specific accounting policies or non-GAAP metrics), for small sets of preparers that form a peer group (e.g. where one firm’s solution diffuses through imitation), or for a larger sector (e.g. industry best practices, which can emerge through networking and may or may not end up being codified in writing).Footnote5

Where an accounting issue is left unresolved by standard setters, and market participants have not produced an abstract-general solution either, preparers will need to develop their own abstract-general guidelines or decide how to account for individual transactions or events on a case-by-case basis (quadrant IV in ). Doing so, they need to rely more strongly on professional judgment, which increases mapping uncertainty and may yield financial information with undesired consequences.

In conclusion, the degree of resolution of a given accounting issue will ultimately reflect both standard setters’ and market participants’ contributions. For instance, even when standard setters fail to (fully) resolve an accounting issue (quadrant II), market participants can compensate for such lack of resolution by standard setters (quadrant III). Therefore, the important question is not only the overall degree of resolution, but also through which institutional arrangements (i.e. standard setters versus market participants) such resolution can be organised most efficiently.

2.3. Do standard setters have a mandate to provide solutions for all accounting issues?

Following from the above, we conceive of a standard setter’s task as being to resolve accounting issues by providing accounting solutions that (a) reduce mapping uncertainty and (b) yield financial information that has desired consequences – to the extent that the standard setter has a competitive advantage in doing so. The latter caveat reflects the fact that not all accounting issues require a high degree of resolution through solutions provided by standard setters. This is the case when solutions developed decentrally by market participants are more efficient (e.g. because preparers have better information about their stakeholders’ information needs).

In the case of IFRS, this understanding of the standard setter’s mandate emanates from the IFRS Foundation’s Constitution (IFRS Foundation Citation2021), Due Process Handbook (IFRS Foundation Citation2020), and Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting (IFRS Foundation Citation2018). To illustrate, consider para. 2 (a) of the Constitution:

‘The objectives of the IFRS Foundation are: (a) through the IASB … , to develop, in the public interest, high-quality, understandable, enforceable and globally accepted standards … for general purpose financial reporting based on clearly articulated principles. These … IFRS Standards are intended to result in the provision of high-quality, transparent and comparable information in financial statements … that is useful to investors and other participants in the world’s capital markets in making economic decisions’ (italics added).

These objectives translate into a ‘job description’ that mandates the IASB to (1) develop accounting solutions (2) with certain properties (3) that will yield financial information with certain attributes. We discuss each of these three elements in turn. The first element reflects the IASB’s core task of developing accounting solutions (‘standards’; left-hand column in ). Importantly, however, as evidenced by the phrase ‘in the public interest’ and by its recurring agenda consultations (as well as well as given its limited resources), this mandate does not imply that the IASB develops solutions for each and every accounting issue. Rather, it should do so only if that is efficient. The IASB’s first task, then, is to decide for which accounting issues it should provide a standard-setting solution at all, and where the development of a solution is better left to market participants. Guidance for these decisions is provided in the Due Process Handbook. For example, the ‘Board evaluates the merits of adding a potential project to the work plan primarily on the basis of the needs of users of financial reports, while also taking into account the costs of preparing the information in financial reports’ (IFRS Foundation Citation2020, para. 5.4), considering a list of criteria including any deficiencies in current practice, the importance of the accounting issue to users, and its pervasiveness and acuteness for preparers (IFRS Foundation Citation2020, para. 5.5).

The second element describes desired formal characteristics of accounting solutions. As quoted above, the high-level guidance from the Constitution intends for IFRS standards to be high-quality, understandable, enforceable, globally accepted, applicable to general purpose financial reporting, and based on clearly articulated principles. The understandability requirement can be seen as intended to reduce preparers’ implementation costs and compliance uncertainty.

The third element mandates that the IASB develop accounting solutions that are effective in that, when implemented by preparers, they produce IFRS financial reports that contain financial information with certain desired attributes.Footnote6 Generally, the attributes of financial information can be distinguished into two categories, depending on whether they are (i) relevant or (ii) (potentially) irrelevant to the standard setter. Attributes under (i) are described in the Conceptual Framework, where financial information is assumed to be ‘useful to existing and potential investors, lenders and other creditors in making decisions relating to providing resources to the entity’ (IFRS Foundation Citation2018, para. 1.2) when it has certain fundamental and enhancing qualitative characteristics, and its production meets a cost constraint. Regarding (ii), financial information prepared under IFRS may exhibit attributes that, while considered desired by some constituents and undesired by others, the standard setter may consider irrelevant to their choice among possible accounting solutions for an accounting issue. For example, IFRS 16’s abolishment of operating lease treatment affects many lessee firms’ financial ratios, raising concerns about greater perceived financial risk and higher cost of capital. These concerns may lead some lessees to adopt other forms of financing, leading to ‘real effects’ on their financing and investing decisions. Since such ‘real effects’ do not necessarily affect the decision usefulness of financial reports, the standard setter may argue that they are irrelevant to its choice among possible accounting solutions for operating leases. We note that individual members of standard setting bodies may disagree about whether and how certain ‘real effects’ should be considered in the standard-setting process.Footnote7

The attributes of IFRS standards and the resulting characteristics of financial information prepared under these standards reflect the perceptions of preparers, regulators, and auditors on the one hand (second element), and those of users of IFRS financial reports on the other hand (third element). Assessing them ex ante, i.e. before a standard has been developed and implemented, is a key challenge for standard setters. The Due Process Handbook’s principles of transparency, full and fair consultation, and accountability (IFRS Foundation Citation2020, section 3) underscore the IFRS Foundation’s view that input from a broad range of constituents facilitates this assessment.

2.4. Resolution and accounting standard design

Standard setters contribute to the resolution of accounting issues by developing accounting standards and accompanying guidance. A deep stream of literature discusses the optimal design of these standards, specifically, whether they should be based on principles or rules.Footnote8 Given the focus of our study, the question arises how the degree of ‘principles- versus or rules-basedness’ of accounting standards relates to the degree of resolution in terms of mapping uncertainty and undesired consequences.

Similar to our concept of resolution, the degree to which accounting standards are principles-based is a continuous concept (e.g. Mergenthaler Citation2009). Rules-based accounting standards tend to be characterised by bright-line thresholds, detailed scope exceptions, large volumes of implementation guidance, and a high level of detail (e.g. Donelson et al. Citation2016; SEC Citation2003). Principles-based standards, on the other hand, are typically characterised as containing clear statements of intent but lacking detailed guidance, rather leaving implementation decisions to the judgment of preparers, auditors and enforcement bodies.

Rules-based and principles-based standards are likely to have different effects on the two problems – mapping uncertainty and undesired consequences – that underlie unresolved accounting issues. Principles-based standards might induce higher mapping uncertainty due to preparers’ wider choice sets (e.g. Kothari et al. Citation2010), creating demand for guidance and more rules-based accounting standards.Footnote9 Rules-based standards, however, are prone to creating undesired consequences (e.g. due to transaction structuring around bright-line thresholds; Collins et al. Citation2012) and compliance uncertainty when rules are unclear or difficult to apply (Binz et al. Citation2021; Plumlee and Yohn Citation2010). We conclude that there is no linear relation between the degree of ‘principles- versus or rules-basedness’ of accounting standards and the degree of accounting issue resolution (mapping uncertainty and undesired consequences).

In the remainder of this study, we will focus on the question to what extent resolution of an accounting issue by standard setters appears desirable, but abstract largely from how (e.g. via principles-based or rules-based standards) achieve such resolution. The type of standard best suited to achieve the desired degree of resolution by standard setters will depend on the specific accounting issue at hand as well as other contextual factors, including the incentives, expertise, and resources of preparers, auditors, and enforcement agencies (Schipper Citation2003). For instance, a principles-based standard is unlikely to resolve an accounting issue (i.e. mitigate mapping uncertainty and lead to desired consequences) when preparers lack the expertise to translate the principle into ‘working rules’ (Kothari et al. Citation2010) for their daily accounting practices, or when there is uncertainty about how the principle will be enforced.

3. Illustrating unresolved accounting issues

In this section, we provide selected examples of accounting issues that appear to lack resolution by standard setters.

3.1. Identifying unresolved accounting issues

As described in the previous section, the resolution of an accounting issue is a continuous concept that reflects the degree of mapping uncertainty as well as the availability of financial information that has desired consequences, and results from accounting solutions provided by different institutions, namely standard setters and market participants. In this section, we illustrate this concept, focusing on accounting issues that appear to exhibit a low degree of resolution by standard setters. To select such unresolved accounting issues, we use the following set of indicators:Footnote10 (a) the issue, while material for a subset of preparers, is not currently subject to a standard (or a previous standard has been withdrawn) or; (b) the existing standard has had an exceptionally long and controversial development history; (c) the existing standard is described as ‘preliminary’ or ‘narrow-scope, while a broader reform is pending; (d) there is evidence in the accounting literature that the current standard is (perceived as) problematic; or (e) the issue appears regularly during agenda consultations. Collectively, these indicators reflect the three elements of the standard setter’s task above, in that unresolved accounting issues tend to be those where the standard setter has either decided against developing a solution despite apparent demand, or has developed as solution that (some) constituents perceive as problematic.

Some of the examples below relate to industry-specific accounting issues, which are relevant for only a relatively small, well-organised group of preparers and their industry associations, who make vocal contributions to the related policy debates.Footnote11 Also, the niche nature of some of these topics often implies that relatively little research attention has been devoted to them. However, the range of unresolved accounting issues also includes broader, industry-agnostic topics, several of which stem from emerging issues and new economic developments.

3.2. Selected cases

3.2.1. Extractive activities

The core question of extractive activities accounting is whether to recognise as assets, and how to measure, expenditures for the exploration and evaluation of mineral resources in the extractive industries (i.e. oil, gas, metals, minerals, etc.). Such expenditures are currently accounted for under IFRS 6, Exploration for and Evaluation of Mineral Resources, which the IASB introduced in 2004 as an interim measure while considering a long-term solution (IFRS Foundation Citation2022). IFRS 6 allows IFRS preparers to continue applying some aspects of their previous accounting policies for exploration and evaluation expenditures, perpetuating diversity in accounting for exploration and evaluation expenditures. A review is currently underway in a new research project Extractive Activities, which the IASB initiated in 2018, and in which it is gathering evidence to help the Board decide whether to develop proposals to amend or replace IFRS 6.Footnote12 Given a lack of ‘sufficient evidence to suggest that the benefits of reducing the diversity in the accounting policies applied to exploration and evaluation expenditure would outweigh the costs’,Footnote13 the IASB tentatively decided not to explore developing requirements or guidance for reserve and resource information in financial statements, but instead to explore amending the disclosure requirements in IFRS 6 and removing the temporary status of IFRS 6.

Without going into too much detail, the project history of extractive activities accounting under IFRS holds several interesting insights into the costs and benefits of leaving an accounting issue unresolved:Footnote14 First, according to the Basis for Conclusions on IFRS 6 (para. BC2), a key reason for issuing this interim standard, which grandfathers firms’ existing accounting treatments for the exploration for and evaluation of mineral resources by providing a temporary exemption from the IAS 8 hierarchy, was the IASB’s concern that forcing firms to solve the accounting issue using the IAS 8 hierarchy, only to change it again later, ‘could have been costly’ for preparers and caused ‘unnecessary disruption’. This concern about preparers’ costs appears to be based on 55 comment letters received on the exposure draft preceding IFRS 6, most of which came from preparers. It seems that potential costs then anticipated by preparers shaped the IASB’s decision not to prescribe a solution that would have limited firms’ choice set of acceptable accounting treatments.

Second, outreach activities conducted in 2019 initially ‘did not include many responses from users.’ Subsequent ‘targeted outreach with investors’, including a survey yielding 25 responses, showed that, whereas all 25 respondents considered exploration and evaluation expenditure information disclosed in the financial statements important or very important for their analyses, and 24 found the existing accounting diversity to pose at least some problems when comparing entities, almost two thirds of respondents (16 out of 25) advocated against solving the accounting issue by proposing a uniform accounting treatment for all entities.Footnote15 The IASB’s decision to keep preparers’ choice sets wide therefore appears consistent with users’ preferences, i.e. a lack of expected benefits from narrowing the set.

Third, having concluded that recognition and measurement issues should be left unchanged for the time being, the IASB unanimously decided to try and render extraction activities accounting more useful for users by exploring ‘developing requirements or guidance to improve the disclosure objectives and requirements about an entity’s exploration and evaluation (E&E) expenditure and activities’.Footnote16 Improved disclosures on exploration and evaluation accounting treatments is also a preferred solution for 15 of the 25 respondents to the user survey. Hence, a ‘disclosure solution’ to the unresolved extraction activities accounting issue appears a reasonable compromise between preparers’ desire to be left alone and users’ need for better information.

3.2.2. Investment property

The subsequent measurement of investment property can also be considered an unresolved accounting issue due to hampered comparability among sector firms. First, the choice between the cost model and the fair value model has been causing continued non-comparability even among publicly traded real estate firms using IFRS, as documented, for example, in Müller, Riedl and Sellhorn (Citation2015) and Christensen and Nikolaev (Citation2013). Early on in the IASB’s history, the European Public Real Estate Association (EPRA) has stepped in to provide a ‘market solution’ by advocating the fair value model, which the vast majority of the industry has been converging towards (EPRA Citation2022).

Second, U.S. real estate firms and Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) remain difficult to compare to their IFRS counterparts, since the FASB prohibits fair value measurement for real estate assets, and voluntary fair value disclosure is rare (Muller, Riedl and Sellhorn Citation2011, Liang and Riedl Citation2014). In 2010, as part of its ongoing convergence efforts with IFRS, the FASB announced its intention to explore permitting or requiring firms to report investment property assets at fair value. To infer investors’ perception of the FASB’s movement toward (and subsequent movement away from) this reporting solution, Conaway, Liang and Riedl (Citation2021) investigate market reactions to six events that increase or decrease the likelihood of U.S. adoption of fair value accounting for investment property assets. Results are consistent with U.S. investors perceiving net benefits from the FASB’s movement toward a fair value reporting approach for this asset class; however, in January 2014 the FASB removed the investment property topic from its agenda without changing existing requirements.

3.2.3. Pollutant pricing mechanisms

A pollutant pricing mechanism is an approach to reducing emissions of pollutants (e.g. greenhouse gases, or GHG). It uses market mechanisms that discourage pollution by employing the ‘polluter pays’ principle to pass the cost of emitting pollutants on to emitters. An example is the EU Emissions Trading Scheme, which was set up in 2005 as ‘a cornerstone of the EU’s policy to combat climate change and its key tool for reducing greenhouse gas emissions cost-effectively.’Footnote17

Accounting issues related to pollutant pricing mechanisms relate to the nature of obligations arising from such schemes, especially where emission allowances are received free of charge, as well as whether, and if so how, to recognise assets and liabilities arising from pollutant pricing mechanisms (e.g. Bebbington and Larrinaga Citation2008).Footnote18 To explore solutions to these issues, the IASB initiated in 2015 a research pipeline project ‘Pollutant Pricing Mechanisms’. This project relates to the earlier ‘Emissions Trading Schemes’ project, which, in 2004, had culminated in the issuance of IFRIC 3 Emission Rights on the accounting for cap and trade emissions trading schemes. IFRIC 3, in turn, had been withdrawn in 2005 due to concerns about accounting mismatches in recognition and measurement bases. Since the withdrawal of IFRIC 3, the accounting issues related to pollutant pricing mechanisms have lacked a standard-setting solution, spurring diversity in practice (e.g. IASB Citation2015, Black Citation2013), and triggering calls for such a solution (e.g. Elfrink and Ellison Citation2009) as well as conceptual research proposing such solutions (e.g. Ertimur et al. Citation2020, Giner Citation2014, Haupt and Ismer Citation2013).

3.2.4. Sustainability-related financial disclosure

The IFRS Foundation recently expanded its standard-setting activities into the area of sustainability-related financial reporting. Initiated in 2020, the Foundation’s ‘Sustainability-related Reporting’ projectFootnote19 has culminated, in November 2021, in the establishment of a new International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), which will ‘develop – in the public interest – a comprehensive global baseline of high-quality sustainability disclosure standards to meet investors’ information needs.’Footnote20 The accounting issue of how to reflect in IFRS financial statements the risks and opportunities related to sustainability matters – in particular, climate change – predates recent developments by many years. Consequently, in 2019 and 2020, the IASB had already provided initial guidance on these matters via an article by Board member Nick AndersonFootnote21 as well as supplementary educational material intended to ‘support the consistent application of requirements in IFRS standards’.Footnote22

The IFRS Foundation’s initiative and surrounding debate, including a consultation paper published in September 2020Footnote23, which triggered 577 comment lettersFootnote24, are testimony to the immense demand by investors and other stakeholders for sustainability-related information. Given the complexity of the task – namely of producing and conveying qualitative and quantitative information that enables users of general purpose financial reporting to understand the impact of significant sustainability-related risks and opportunities on its financial position, financial performance and cash flows at the reporting period end, and the anticipated effects over the short, medium and long termFootnote25 – preparers’ compliance uncertainty is likewise massive.

The IFRS Foundation has chosen to solve the accounting issues related to sustainability reporting via a new Board (the ISSB), which will sit and operate alongside the IASB within the Foundation, rather than, for example, by elevating the existing IFRS Practice Statement 1 Management CommentaryFootnote26 into the status of a full IFRS and augmenting it with guidance on sustainability-related financial disclosures, by developing a separate IFRS for this purpose, by expanding upon its existing educational material, or by referencing existing frameworks for sustainability reporting.Footnote27 Given that, at the time of this writing, the ISSB has yet to start operating, and that potentially competing sustainability reporting requirements are being developed elsewhere,Footnote28 it will be some time before preparers’ compliance uncertainty in this important area will be resolved.

3.3. Interim conclusion

This discussion of (a selected set of) unresolved accounting issues illustrates that different ‘players’, including standard setters and various market participants, can contribute to the resolution of an accounting issue by developing an accounting solution that meets the needs of the constituents of accounting. These players employ different ‘technologies’ in developing solutions, which include accounting standards, interpretations, or industry best practices. Importantly, we stress again that an accounting solution developed by the standard setter (i.e. either a required accounting treatment or an overt choice among several treatments) constitutes neither a sufficient nor a necessary condition for a high degree of resolution of the issue at hand. This is because, first, a standard-setting solution may fail to meet constituents’ needs, and second, a solution meeting constituents’ needs may emerge via market forces without the standard setter stepping in. We further observe again that the resolution of an accounting issue invariably is a matter of degree – someone will always be somewhat ‘unhappy’.

We now turn to the decision problem implied by the first element of the standard setter’s task, namely whether to take the development of a solution for a given accounting issue into its own hands, or to leave its resolution entirely to market participants. Whereas the benefits of such resolution (e.g. potentially increased comparability, or reduced transaction cost) feature prominently in policy discussions and academic research, we argue standard setters should also consider its (opportunity) cost.Footnote29

4. Learning and innovation in accounting

4.1. Supply and demand for resolution

The optimal degree of resolution depends on its costs and benefits. Clearly, a high degree of resolution has significant benefits as it reduces mapping uncertainty and/or undesired consequences resulting from extant accounting solutions. Given the importance of these benefits, prior studies have emphasised the demand for resolution (mostly in terms of undesired consequences) and analysed whether it is better met by standard setters or market participants (e.g. by exploring the conditions under which managers make opportunistic or informative accounting choices; see Fields et al. Citation2001). By contrast, we focus on the supply side of accounting resolution. Doing so, we consider that developing, or ‘producing’, an accounting solution is costly, and that standard setters and market participants have only limited resources at hand that they can devote to this task. To that end, we focus on what we believe are two key cost factors restricting the supply of accounting resolution: learning costs and opportunity cost of stifled innovation. In the following section, we describe these two cost types in more detail.

4.2. Learning in accounting contexts

4.2.1. Uncertainty about optimal accounting solutions

Standard setters and market participants are likely to face uncertainty about the optimal accounting solution to an unresolved accounting issue. Such uncertainty arises because standard setters have only incomplete knowledge about the effects of their standards on a diverse set of preparers and users (Sunder Citation2010; Dye Citation2002),Footnote30 and preparers have incomplete knowledge about the degree of permissibility of different accounting treatments (compliance uncertainty), as well as their stakeholders’ responses to different accounting treatments (outcome uncertainty). For example, Oberwallner et al. (Citation2021) document uncertainty about stakeholder responses to a firm’s decision to reshape its corporate reporting. Similarly, Gassen and Muhn (Citation2018) and Bourveau et al. (Citation2021) provide empirical evidence on preparers’ incomplete knowledge about their optimal reporting. Thus, to resolve an accounting issue, both standard setters and managers need to engage in learning.

4.2.2. Learning strategies

Learning by standard setters typically involves a formalised process by which the standard setter devotes resources to collecting information about the (expected ex-ante and actual ex-post) effects of different potential accounting solutions on a broad range of constituents (such as affected preparers and their investors). For example, the IASB’s due process can be viewed as a costly solution-finding mechanism by which the IASB seeks to understand the (decision-usefulness) benefits and (compliance) costs of alternative solutions to a given accounting issue. As explained in para 3.76 of the IFRS Foundation’s Due Process Handbook: ‘The Board is committed to assessing and explaining its views about the likely costs of implementing proposed new requirements and the likely ongoing associated costs and benefits of each new IFRS Standard – the costs and benefits are collectively referred to as effects. The Board gains insight on the likely effects of the proposals for new or amended Standards through its formal exposure of proposals and through its fieldwork, analysis and consultations with relevant parties.’

Whereas standard setters’ learning is, at least to some extent, determined by a formal standard-setting process, market participants (especially, preparers) can choose among different learning strategies. First, preparers can learn from their own past experience. This learning mechanism might be especially important for ‘technical,’ compliance-oriented accounting issues that remain relatively stable over time. For instance, Liu et al. (Citation2004) find that the quality of banks’ value-at-risk disclosures improves as banks learn and refine their modelling and estimation techniques over time. Similarly, the then IASC established the choice between the cost and fair value models of measuring investment properties (IAS 40.30) in order to ‘to give preparers and users time to gain experience with using a fair value model’ (IAS 40.BC12).

Second, preparers can learn about their reporting costs and benefits from external information sources. Such learning involves direct communication with users of financial statements, e.g. via stakeholder survey. In this vein, Jung (Citation2013) finds investor overlap being an important determinant in the diffusion of a new hedge accounting practice, suggesting that affected firms learn about and respond to their investors’ reporting demands. Next to learning from their own users, preparers can also learn about their reporting costs and benefits via social learning, i.e. by observing other firms’ reporting (for overviews, refer to Brenner, Citation2006; Duffy, Citation2006). Several studies provide evidence consistent with social learning in firms’ business decisions (for a review, see Liebermann and Asaba, Citation2006). Specifically, these studies provide evidence that, by observing their peers’ choices and outcomes, firms update their beliefs about their own optimal behaviour.Footnote31

Consistent with social learning in accounting contexts, Drake et al (Citation2019) provide empirical evidence on disclosure benchmarking by auditors, which they define as ‘auditors’ acquisition of non-client financial statement information for the purpose of evaluation a client’s financial statement information’ (p. 393). They provide survey and archival evidence (using a proxy derived from auditors’ clicks on non-client financial statements filed with the SEC) that disclosure benchmarking is an important learning mechanism used by auditors. In their survey among auditors, 88.5% of respondents indicated that they are extremely likely or somewhat likely to look at the 10-K filings of another company when reviewing a client’s 10-K filing. Consistent with this notion, they document that auditors access, on average, about ten non-client financial statements in the period prior to their own clients’ filings. Interestingly, their finding that auditors use benchmark firms at both ends of the accounting quality spectrum (i.e. firms with very high and firms with very low accounting quality) appears to be consistent with auditors aiming to learn about the range of acceptable accounting treatments, rather than about ‘best practice’ only. Similarly, interview evidence in Mauritz et al. (Citation2021) also supports the role of peer learning, with responding auditors stating that they advise clients to consider competitors’ disclosures (p. 26). Taken together, these results suggest that the role of social learning generalises across different settings and types of firms, with Drake et al. (Citation2019) focusing on U.S. publicly listed firms, and Mauritz et al. (Citation2021) studying German private firms.

4.2.3. Learning costs

To apply the learning strategies described in the previous section, standard setters and market participants need to incur costs. Empirical evidence on these costs is scarce and mainly focused on the processing and compliance costs that preparers need to incur when finding and implement ‘working rules’ (Kothari et al. Citation2010) in their day-to-day accounting practices. This task requires resources, in particular, accounting expertise. Consistent with an increased need for learning, Chychyla et al. (Citation2019) find that, when the accounting requirements applying to a given firm are more complex, the number of accounting experts on the board and audit committee increases. Since the number of board members is limited, the need to acquire more accounting expertise likely comes at the cost of lower expertise with respect to other (e.g. operational) skills. Consistent with such a trade-off, Bernard et al. (Citation2020) present evidence that CFOs with high accounting expertise lack expertise in other areas.

In addition to investing into in-house expertise, preparers can also incur learning costs via ‘outsourcing’ the resolution of their accounting issues. In this case, rather than learning about optimal reporting themselves, they rely on the expertise of gatekeepers and information intermediaries. Mauritz et al. (Citation2021) provide evidence on the role of a high-expertise gatekeeper (the auditor) in addressing an unresolved accounting issue (narrative reporting) for a sample of firms with low accounting expertise (private firms). They find that auditors importantly shape firms’ narrative disclosures, and that auditors’ imprint is larger for firms with higher learning costs (i.e. for small firms). Field evidence from interviews with auditors supports the notion that auditors’ superior expertise (relative to preparers) is an important reason for their role in shaping clients’ disclosures.Footnote32

A key advantage of auditors is that they can scale their learning efforts over several clients (Mauritz et al. Citation2021), allowing them to build up task-specific expertise (Ahn et al. Citation2020). This, however, does not imply that their learning is costless. For instance, Zimmerman et al. (Citation2021) document that audit firms are more likely to involve an in-house specialist on engagements involving fair value measurement, intangible assets, or pension liabilities – areas of potentially unresolved accounting issues that require a greater degree of professional judgment. Consistent with auditors’ learning costs being passed on to clients at least partially, Zimmerman et al. (Citation2021) document that specialist involvement is associated with higher audit fees.Footnote33 Similarly, Drake et al. (Citation2019) provide evidence on auditors making larger efforts to learn from non-clients’ financial statements when the application of accounting standards is more challenging (i.e. in the presence of complex, technical guidance).Footnote34

4.3. Accounting innovation

Next to learning costs, resolving an accounting issue can also be costly when it stifles accounting innovation. In the following section, we discuss these opportunity costs, along with an alternative view that accounting issue resolution could have positive effects on innovation in accounting.

4.3.1. Negative effects of resolution on innovation

On the one hand, there are arguments that a high degree of resolution of a given accounting issue could affect accounting innovation negatively (and, hence, that leaving it relatively unresolved could be beneficial). First, a high degree of resolution can dampen agents’ incentives to question the current accounting treatment and learn about better alternatives. In contrast, a low degree of resolution can create an immediate need that preparers (and their stakeholders) search for and develop novel accounting treatments addressing mapping uncertainty and undesired consequences. For example, in the absence of precise guidance on the process of measuring provisions, firms may innovate by using machine learning techniques in an effort to reduce objective estimation errors as well as managerial manipulation (Ding et al. Citation2020). Similarly, in the absence of a standardised solution, generally accepted practices can evolve over time via social norms relying on professional, context-specific judgment (Sunder Citation2010). Requiring preparers to exercise such judgment provides them with incentives to invest in their accounting expertise and can, thus, enhance the professional dialogue and accounting innovation.

This positive effect of a low degree of resolution on learning and innovation incentives can also have broader implications for the accounting profession. Sunder (Citation2010) voices concerns that accounting education suffers because the increased tendency to resolve accounting issues via standardisation crowds out critical thinking and professional judgment, leading to negative selection effects as accounting becomes unattractive for students looking to acquire these skills. To combat this trend, the Pathways Commission sponsored by the American Accounting Association (AAA) and the American Institute of Chartered Public Accountants developed its Vision Model (Pathways Commission Citation2015). The now-famous ‘This is Accounting!’ diagram illustrates that accounting requires critical thinking and professional judgment when mapping economic activity into useful information for good decisions – rather than consisting only of repetitive routine tasks. Similarly, Schipper (Citation2003) emphasises the need to develop adequate skills if accounting standards rely more on principles and, hence, professional judgment. Madsen (Citation2011) provides empirical evidence consistent with a crowding-out effect of the establishment of the FASB on the participation of professional accountants, organisations, and accounting experts in the professional dialogue.

Second, resolving accounting issues can hinder innovation because resolved accounting issues are more difficult to adapt to changes. Farrell and Saloner (Citation1985) investigate model situations where firms are trapped in an inferior standard even though there is a better alternative available. They refer to these situations as ‘excess inertia.’ Excess inertia arises because there is no individual firm with sufficiently high incentives (or, possibilities) to deviate from the existing standard and, thus, ‘get the bandwagon rolling,’ even though firms would collectively prefer an alternative solution. In a similar vein, inertia might arise where conceptual frameworks are imposed ‘top down’ by standard setters to apply to all sorts of accounting issues. These frameworks serve as stable guardrails within which more detailed rule-making takes place. Thus, they only slowly (if at all) adapt to changes in economic conditions (e.g. triggered by the development of new technologies) and, as a result, may present inadequate (‘outdated’) reference points (for a related criticism on reliance on conceptual frameworks, see Waymire and Basu Citation2022). Further, the constraints imposed by these frameworks likely inhibit accounting innovation because they constrain preparers’ opportunities to experiment with different accounting practices and learn from ‘trial and error’ (e.g. Chen et al. Citation2020).

According to Farrell and Saloner (Citation1985), excess inertia will be especially acute when there is incomplete information about firms’ preferences, making coordination among them more difficult. This finding suggests an important implication for the role of standard setters, industry associations, professional networks,Footnote35 and gatekeepers. They can provide a communication platform for constituents to share information about their preferred accounting solutions, facilitating coordination and, thus, diffusion of accounting innovation and adaptation of existing solutions to changes in the business environment. Such a role is consistent with the recommendation by Waymire and Basu (Citation2022) that standard setters focus on knowledge curation, rather than knowledge creation.

4.3.2. Positive effects of resolution on innovation

On the other hand, resolving an accounting issue can also spur accounting innovation. Specifically, centrally developed, abstract-general solutions to accounting issues can serve as ‘infrastructure.’ Such a role has been documented in prior studies on the consequences of standardisation (Meeks and Swann Citation2009). The idea is that the knowledge codified by standardisation can serve as a reference point, helping the dissemination of ‘best practices.’ Swann (Citation2010) uses the analogy of pruning and training fruit trees by cutting off unproductive branches to channel available energies and resources into the most promising areas. An important implication of this ‘infrastructure role’ of standards in resolving an accounting issue could be that it frees up resources that preparers can then spend on more productive pursuits.Footnote36 Importantly, this role of abstract-general standards does not hinge on them being developed by standard setters; arguably, industry best practices established by market participants can work similarly.

5. Conclusion

We have provided a conceptual framework to describe the resolution of accounting issues and discussed empirical evidence on three of its important consequences: consistency and comparability of accounting practices, learning about optimal accounting practices, and accounting innovation. Whereas unresolved accounting issues feature prominently in professional dialogues and practitioner discussions, there is little academic research on the costs of achieving resolution, and how they differ between standard setters and market participants.

Our study provides the following insights: First, accounting issues are manifold (including matters related to recognition, measurement, presentation and disclosure), and it would be misleading to consider their resolution a dichotomous concept (i.e. either ‘resolved’ or ‘unresolved’). Rather, we conceive of resolution as a continuous concept, i.e. a matter of the degree to which (a) there is uncertainty about firms’ accounting treatments and (b) these accounting treatments yield financial information with desired consequences. Second, accounting issues can be resolved by different agents and at different levels. Whereas standard setters and industry associations centrally develop abstract-general solutions that apply to whole classes of firms and accounting issues, individual preparers’ decisions about the accounting treatments they apply to a given issue will also contribute to ultimate resolution. Thus, preparers may subjectively perceive different degrees of resolution. Third, a lower degree of resolution provided by standard setters can cause larger costs for preparers; these learning costs are different from, and incremental to, the (one-time and ongoing) costs of compliance with a given solution. Fourth, the higher the degree of resolution, the lower are preparers’ compliance uncertainty, learning costs, and scope for opportunistic discretion – but also preparers’ learning benefits and signalling opportunities. Therefore, what degree of resolution is efficient (i.e. net beneficial from a societal welfare perspective) is highly context-dependent.

These insights suggest the following areas where we think more evidence would be especially promising. First, researchers interested in the consequences of resolving an accounting issue face a measurement problem: How can we capture the degree of accounting issue resolution? There are some existing measures based on firms’ observed accounting practices (e.g. Peterson et al. Citation2015), on the characteristics of written accounting standards (e.g. Chychyla et al. Citation2019), or both (Andreicovici et al. Citation2020). These measures, however, reflect both the need for resolution as well as standard setters’ and firms’ efforts to address it. Therefore, these measures speak only indirectly to the actual degree of resolution. We believe collecting field evidence from preparers and other constituents of accounting on the degree to which they perceive a given accounting issue as resolved would be a useful first step towards better characterising the phenomenon.

Second, different agents and institutions can contribute to the resolution of accounting issue at different levels. We know relatively little about these agents’ learning mechanisms and the relative costs they incur when searching for and developing accounting solutions. Better understanding these costs and mechanisms is important for determining the efficient degree of resolution for a given accounting issue, as well as the efficient mix of contributions by different ‘players’ to that resolution. For instance, the efficient resolution is likely to depend on the type of issue and the number of firms affected. In particular, market-wide standards appear to be better suited for resolving accounting issues faced by a larger number of firms, to avoid duplicative learning efforts.

Third, it is theoretically ambiguous whether a greater degree of resolution will spur or reduce innovation in accounting. Thus, we believe empirical evidence on this question would be especially useful. Again, given the lack of a readily available measure for firms’ accounting innovation, such evidence would also need to rely on field data.

Fourth, we have focused on whether and when standard setters have a competitive advantage (relative to market participants) in resolving accounting issues. A related question, exceeding the scope of our paper, is which accounting standards design – rules-based or principles-based – is preferrable to achieve such resolution. The answer to this question is likely to depend on numerous contextual factors, such as the nature of the underlying accounting issue, the enforcement regime, and affected constituents’ expertise and incentives in applying accounting standards.

We close with the following standard-setting implications. Given the above discussion, standard setters have three main tasks. The first is to decide for which ones among a potentially large set of issues accounting standard setters have a competitive advantage over market participants when it comes to finding solutions. The IASB’s five-yearly agenda consultations among a wide set of constituents serve this purpose. This decision is initially disconnected from the question of what the solution should look like. For example, should the IASB develop an accounting standard for emissions trading schemes, or are preparers and their industry associations better poised to converge on a solution that minimises compliance uncertainty and undesired consequences?

Second, the standard setter works towards understanding which one among a possible set of accounting practices for a given economic transaction or event would provide the most decision-useful information to investors. Users’ views and relevant academic studies should be most helpful in this regard, whereas preparers’ perspectives seem less pertinent (and may even be viewed sceptically as potentially self-serving).

Third, once a decision-useful accounting treatment has been settled upon, the focus should lie on the appropriate degree of resolution and the design of accounting standards to achieve it. In these deliberations, preparers’ and auditors’ views should also be considered, as their perspectives matter for assessing the trade-off between costs (compliance uncertainty) and benefits (learning, innovation) of leaving an accounting issue unresolved by standard setters. Similarly, the extent of resolution achieved by a rules-based versus principles-based standard depends on preparers’ ability to translate a given principle into practical, day-to-day working rules and policies when preparing their financial statements. For example, in the context of goodwill accounting, users’ information needs and academic studies (e.g. Amel-Zadeh et al. Citation2021) can help settle on an appropriate accounting treatment (e.g. impairment-only vs amortisation), whereas preparers should (only) be consulted when it comes to the extent of guidance needed to ensure compliance.

Overall, the IASB can make its own job easier by narrowing down the constituent groups that it consults on a given aspect of the standard-setting task. For example, while users should be most competent in evaluating the decision usefulness of alternative accounting solutions, preparers’ views are most relevant when it comes to assessing their implementation costs, and academics should be able to speak with the greatest authority about related research findings. Standard setters’ focusing on the most relevant constituents for a given aspect of standard setting would save time and resources, as well as contribute to railing in self-interested lobbying.Footnote37

Acknowledgements

We thank the ICAEW as organisers of the 2021 Information for Better Markets Conference, as well as the Editors of Accounting and Business Research, for the kind invitation to contribute this article and related conference presentation. We are grateful to Doug King (discussant), an anonymous reviewer, Rolf Uwe Fülbier, Katherine Schipper, and participants of the 2021 Information for Better Markets Conference for their insightful comments. We thank Kim Frank and Inga Meringdal for excellent research assistance. The authors acknowledge financial support from the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft – DFG): project ID 403041268 – TRR 266. All errors are our own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 We view ‘disclosure overload’ as a potential concern of both users and preparers, consistent with the IASB’s survey results indicating that significant fractions of surveyed users and preparers agreed or strongly agreed that ‘too much irrelevant information’ is part of ‘the disclosure problem’ (IFRS Foundation Citation2013, p. 35).

3 Note that in our discussion, we focus on whether standard setters provide a solution, rather than how they do so (e.g., via rules-based versus principles-based standards).

4 We note a potential exception from this rule – the ‘True and Fair Override’, under which, in ‘the extremely rare circumstances in which management concludes that compliance with a requirement in an IFRS would be so misleading that it would conflict with the objective of financial statements set out in the Conceptual Framework, the entity shall depart from that requirement’ (IAS 1.19). See, for example, Evans (Citation2003). Here, the standard setter effectively delegates the responsibility for developing an appropriate accounting solution to preparers. There is some empirical evidence suggesting that preparers tend to invoke the ‘True and Fair Override’ where there is less authoritative guidance (Livne and McNichols Citation2009).

5 An example of written industry best practices is the European Public Real Estate Association’s (EPRA) Best Practice Recommendations Guidelines (EPRA 2012), ‘which focus on making the financial statements of public real estate companies clearer and more comparable across Europe’, particularly by recommending that firms adopt the fair value model of accounting for investment property under IAS 40 (rather than the permitted alternative, the cost model).

6 To see the difference between the formal attributes of an accounting solution (‘standard’) itself and those of the financial information resulting from its application by preparers, consider as an example the attribute of understandability. In paragraph 2 (a) of the Constitution, ‘understandable’ relates to ‘standards (referred to as ‘IFRS Standards’)’, whereas in paragraphs 2.4, 2.23, and 2.34-2.36 of the Conceptual Framework, that term relates to ‘financial information’. In the former case, as noted above, understandability intends to reduce preparers’ implementation costs and compliance uncertainty, whereas in the latter case, understandability is among the ‘qualitative characteristics that enhance the usefulness of information’ for users (IFRS Foundation Citation2018, para. 2.23).

7 In a current working paper, Gassen, Sellhorn and Weiß (Citation2022) use interview evidence and public statements to show that individuals involved in IFRS-related standard setting vary in terms of their ex-ante awareness of potential real effects, as well as the extent to which they consider them relevant costs or benefits (versus irrelevant non-issues) when deciding among alternative accounting practices.

8 This literature exists despite fundamental concerns about the principal impossibility of deriving accounting standards that completely and correctly rank alternatives according to constituents’ preferences (Demski Citation1973).

9 Consistent with this notion, Donelson et al. (Citation2016) document that standards are more rules-based when accounting issues are more complex and there are more frequent transactions. In these contexts, the demand for resolution by standard setters is arguably higher because it is more cost-effective for market participants to rely on one centrally provided solution rather than to ‘reinvent the wheel for common transactions’ (Kothari et al. Citation2010).

10 We thank Katherine Schipper for insightful comments on selecting these indicators; see also Schipper (Citation2022).

11 The extent to which accounting issues like extractive activities, rate-regulated activities, pollution pricing mechanisms (such as GHG emission rights), insurance contracts, investment property, or leases are truly confined to a single industry varies. They share in common, however, that they relate to certain resources or activities that tend to be material only in a limited set of industries.

12 A previous research project, which culminated in an IASB Discussion Paper (DP/2010/1), was suspended by the Board in 2010.

14 Most of these emerge from the IASB’s September 2021 staff papers on the extractive activities project, available here: https://www.ifrs.org/projects/work-plan/extractive-activities/#project-history.

15 See Extractive Activities Cover Paper, September 2021, Appendix B, available here: https://www.ifrs.org/content/dam/ifrs/meetings/2021/september/iasb/ap19-cover-paper.pdf.

18 Bebbington and Larrinaga (Citation2008) forms the introduction to the Special Section: Accounting and the Market of Emissions of European Accounting Review. For more information on the accounting issues arising in the context of pollutant pricing mechanisms, refer to the IASB’s Emissions Trading Schemes (https://www.ifrs.org/projects/completed-projects/2012/emissions-trading-schemes/) and Pollutant Pricing Mechanisms (https://www.ifrs.org/projects/work-plan/pollutant-pricing-mechanisms/#about) project websites.

21 See https://www.ifrs.org/content/dam/ifrs/news/2019/november/in-brief-climate-change-nick-anderson.pdf.

24 See https://www.ifrs.org/projects/completed-projects/2021/sustainability-reporting/consultation-paper-and-comment-letters/#view-the-comment-letters. Großkopf et al. (Citation2021) analyse and summarise these comment letters.

25 This wording mirrors the IFRS Foundation’s ‘Climate-Related Disclosures Prototype’ (www.ifrs.org/content/dam/ifrs/groups/trwg/trwg-climate-related-disclosures-prototype.pdf), which states in para. 9: ‘An entity shall disclose information that enables users of general purpose financial reporting to understand the impact of significant climate-related risks and opportunities on its financial position, financial performance and cash flows at the reporting period end, and the anticipated effects over the short, medium and long term.’ The prototype goes on to require several disclosures to be made, ‘qualitatively, and quantitatively when feasible’.

26 See the related project website here: https://www.ifrs.org/projects/work-plan/management-commentary/

27 For example, in one of the comment letters on the IASB’s September 2020 consultation paper, Adams (Citation2020) states: ‘There is already a global set of internationally recognised sustainability reporting standards. There is no need for another one. The GRI Standards are internationally recognised and used by companies around the world. The IFRS Foundation could use its relationships to assist in making those Standards mandatory’.

28 These include, for example, the EU’s proposed Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52021PC0189) to be complemented with standards developed by EFRAG, the SEC’s plans to develop a mandatory climate risk disclosure rule proposal by the end of 2021 (see speech by SEC Chair Gary Gensler: https://www.sec.gov/news/speech/gensler-pri-2021-07-28), and the UK Chancellor’s announcement to implement economy-wide Sustainability Disclosure Requirements (see report ‘Greening Finance’: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1031805/CCS0821102722-006_Green_Finance_Paper_2021_v6_Web_Accessible.pdf).

29 Analyzing these costs provides a first step towards a more comprehensive social welfare analysis featuring costs and benefits arising for multiple constituents in the aggregate.

30 Standard setters’ outreach activities can be interpreted as their attempt to reduce this uncertainty.

31 For example, Kaustia and Rantala (Citation2015) find that firms are more likely to initiate stock splits after competitors have done so, and are more likely to do so after stock splits with favorable market reactions. Similarly, Leary and Roberts (Citation2014) find evidence of peer effects in firms’ capital structure decisions consistent with a learning motive. Foucault and Fresard (Citation2014) analyse how firms’ investment decisions depend on their peers’ valuation. They conjecture that firms learn about their own growth opportunities from peer firms’ stock prices.

32 For instance, Mauritz et al. (Citation2021) quote one auditor as follows: ‘Smaller firms need more help. […] The accounting department in these small firms often lacks expertise and there are topics for which they [small firms] depend on us’ (p. 27). As the authors discuss in the paper, the statutory auditor’s role in these settings risks transgressing the line between (legal) auditing and (illegal) consulting by the auditor on the same set of financial statements that they themselves will subsequently have to opine on.

33 For complementary evidence on the role of expertise in the audit process, refer to, e.g., Glover et al. (Citation2019).

34 Drake et al. (Citation2019, p. 395) argue that the presence of such guidance reflects increased financial reporting uncertainty because complex, technical guidance is an endogenous outcome in industries with more complex underlying transactions and events.

35 In Germany, for example, the Schmalenbach-Gesellschaft für Betriebswirtschaft e.V., whose activities date back to the early 1900s, initiates and coordinates dialogue between business research, teaching and practice. As the oldest such association in the German-speaking area, it offers an important meeting place for business administration science and practice and provides a unique network. Among its Working Groups, the ‘Arbeitskreis Externe Unternehmensrechnung’ (Working Group for Corporate Reporting) was established in 1975 and seeks to actively shape the development of accounting by influencing the process of developing national and international accounting rules and standards in an advisory capacity.

36 For example, if chief accountants and CFOs need to spend less time on devising solutions that comply with complex, arcane accounting rules, they can spend more time on strategic issues.

37 In other areas, consulting with dedicated experts is commonplace. For example, it would be odd for a tax legislator to rely indiscriminately on tax payers for all aspects of a given tax reform, or for a medical regulator to listen primarily to the pharmaceutical industry.

References

- Adams, C., 2020. Comment letter on the exposure draft proposing amendments to the FIRS foundation constitution. Available online: http://eifrs.ifrs.org/eifrs/comment_letters//570/570_27003_CarolAdamsIndividual_0_ProfessorCarolAdams.pdf (accessed 1 December 2021)

- Ahn, J., Hoitash, R., and Hoitash, U., 2020. Auditor task-specific expertise: the case of fair value accounting. The Accounting Review, 95 (3), 1–32.

- Amel-Zadeh, A., Glaum, M., and Sellhorn, T, 2021. Empirical goodwill research: Insights, issues, and implications for standard setting and future research. European Accounting Review, forthcoming. doi:10.1080/09638180.2021.1983854.

- Andreicovici, I., van Lent, L., Nikolaev, V. V., and Zhang, R., 2020. Accounting measurement intensity. Chicago Booth Research Paper.

- Bebbington, J., and Larrinaga-Gonzalez, C, 2008. Carbon trading: accounting and reporting issues. European Accounting Review, 17 (4), 697–717.

- Bernard, D., Ge, W., Matsumoto, D. A., and Toynbee, S., 2020. Implied tradeoffs of CFO accounting expertise: evidence from firm-manager matching. Available at SSRN 2858681.

- Binz, O., Hills, R., and Kubic, M., 2021. Did the FASB codification reduce the complexity of applying US GAAP?. Available at SSRN 3960950.

- Black, C. M, 2013. Accounting for carbon emission allowances in the European union: in search of consistency. Accounting in Europe, 10 (2), 223–239.

- Bourveau, T., Breuer, M., and Stoumbos, R. C., 2021. Learning to disclose: disclosure dynamics in the 1890s streetcar industry. Working Paper. Available at SSRN 3757679.

- Brenner, T, 2006. Handbook of computational economics. Handbook of Computational Economics, 2, 895–947.

- Chen, Y., Du, K., Wang, S., and Wang, Z., 2020. Misreporting as strategic experimentation: theory and evidence.

- Christensen, H. B., and Nikolaev, V. V., 2013. Does fair value accounting for non-financial assets pass the market test? Review of Accounting Studies, 18 (3), 734–775.

- Chychyla, R., Leone, A. J., and Minutti-Meza, M., 2019. Complexity of financial reporting standards and accounting expertise. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 67 (1), 226–253.

- Collins, D. L., Pasewark, W. R., and Riley, M. E, 2012. Financial reporting outcomes under rules-based and principles-based accounting standards. Accounting Horizons, 26 (4), 681–705.

- Conaway, J. K., Liang, L., and Riedl, E. J., 2021. Market perceptions of fair value reporting for tangible assets. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, forthcoming. doi:10.1177/0148558X211021217.

- Demski, J. S, 1973. The general impossibility of normative accounting standards. The Accounting Review, 48 (4), 718–723.

- Ding, K., Lev, B., Peng, X., Sun, T., and Vasarhelyi, M. A., 2020. Machine learning improves accounting estimates: evidence from insurance payments. Review of Accounting Studies, 25 (3), 1098–1134.

- Donelson, D. C., McInnis, J., and Mergenthaler, R.D., 2016. Explaining rules-based characteristics in U.S. GAAP: Theories and evidence. Journal of Accounting Research, 54 (3), 827–861.

- Drake, M. S., Lamoreaux, P. T., Quinn, P. J., and Thornock, J. R., 2019. Auditor benchmarking of client disclosures. Review of Accounting Studies, 24 (2), 393–425.

- Duffy, J, 2006. Agent-based models and human subject experiments. In: L. Tesfatsion and K. L. Judd, eds. Handbook of Computational Economics. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 949–1011.

- Dye, R. A, 2002. Classifications manipulation and nash accounting standards. Journal of Accounting Research, 40 (4), 1125–1162.

- Elfrink, J., and Ellison, M, 2009. Accounting for emission allowances: an issue in need of standards. The CPA Journal, 79 (2), 30.

- EPRA, 2022. Best practices recommendation guidelines. Available from https://www.epra.com/finance/financial-reporting/guidelines.

- Ertimur, Y., Francis, J., Gonzales, A., and Schipper, K, 2020. Financial reporting for pollution reduction programs. Management Science, 66 (12), 6015–6041.

- Evans, L, 2003. The true and fair view and the ‘fair presentation’ override of IAS 1. Accounting and Business Research, 33 (4), 311–325.

- Farrell, J., and Saloner, G., 1985. Standardization, compatibility, and innovation. The RAND Journal of Economics, 16 (1), 70.

- Fields, T. D., Lys, T. Z., and Vincent, L., 2001. Empirical research on accounting choice. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 31 (1-3), 255–307.

- Foucault, T., and Fresard, L, 2014. Learning from peers’ stock prices and corporate investment. Journal of Financial Economics, 111 (3), 554–577.

- Gassen, J., and Muhn, M., 2018. Financial transparency of private firms: evidence from a randomized field experiment. Working Paper on SSRN. Available at SSRN 3290710.

- Gassen, J., Sellhorn, T., and Weiß, K., 2022. The role of real effects in accounting standard setting. Unpublished working paper.

- Giner, B, 2014. Accounting for emission trading schemes: a still open debate. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal, 34 (1), 45–51.