Abstract

This study reviews and compares the definitions and measurements of ‘corporate reputation’ used in 173 studies published in seven top-tier accounting and management journals between 1980 and 2020. Accounting scholars frequently fail to define ‘reputation,’ and if they do, definitions vary considerably between the accounting and management fields. We further find that measures of reputation do not fit well with its definition. The accounting literature often employs secondary financial measures, which poorly reflect stakeholders’ reputation assessments. We develop a conceptual framework to better classify prior research and identify appropriate measures of reputation that match the chosen definition. We also suggest a number of further research opportunities: Accounting scholars may focus more on (a) stakeholders’ subjective nonfinancial assessments; (b) the emotional appeal of companies and its relationship with competence and integrity assessments; (c) the role of stakeholders’ normative expectations and (d) explicitly consider a multi-stakeholder perspective, where corporations have multiple reputations rather than one.

We can afford to lose money – even a lot of money. But we can’t afford to lose reputation – even a shred of reputation. – Warren Buffett

1. Introduction

The quality of financial reporting and auditing cannot be easily observed. The reputation of reporting entities and/or audit firms therefore plays an important role in the evaluation of financial reporting quality. Reputation is a source of unique and nearly inimitable competitive advantage (e.g. Hall Citation1992, Lange et al. Citation2011, Shapiro Citation1983), and significantly contributes to a company’s value. Accordingly, publicly listed companies suffer significant market value losses and their audit firms lose many clients when legal rules regarding financial presentation are assumed to be violated (Chaney and Philipich Citation2002, Karpoff et al. Citation2008, Weber et al. Citation2008, Skinner and Srinivasan Citation2012).

Because reputation is important for any company, corporate reputation (hereafter reputation) has received considerable attention from accounting scholars and practitioners since the 1980s, and this interest has grown rapidly since 2000 (e.g. Balvers et al. Citation1988, Bushman and Wittenberg-Moerman Citation2012; Cao et al. Citation2015, Chakravarthy et al. Citation2014). However, despite the rich body of accounting research examining reputation, our ability to draw conclusions about what is known about reputation, to generalise empirical findings, and to develop related substantive theory may be built on sand.

The advancement of knowledge in any research field very much depends on a common understanding of the key concepts, conceptual clarity, and congruence of what is measured and what is supposed to be measured (MacKenzie Citation2003; Suddaby Citation2010, Wacker Citation2004). These issues are especially important when the phenomenon of interest is difficult to comprehend conceptually as well as empirically because of its physically invisible and complex nature, and when it depends only on subjective judgements by stakeholders. Reputation is in this respect quite a Gordian concept. There is further reason to be concerned about the above-mentioned issues because a review of the reputation research in the field of management, which has a rich tradition in the reputation domain, concludes that this discipline has been plagued by ‘problems of definitional confusion and poor construct measurement’ (Dowling Citation2016, p. 207).

Is reputation research in accounting in such distress as well? This paper addresses this issue and asks the following three basic but fundamental questions:

How has the accounting literature defined and conceptualised corporate reputation?

How has the accounting literature measured corporate reputation, and do these measures match its definition?

What are the implications for future accounting research on corporate reputation?

To answer these questions, this paper comprises a comprehensive review of all articles published between 1980 and 2020 in top-tier accounting journals (Accounting, Organizations and Society, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Journal of Accounting Research, and The Accounting Review). We also consider Accounting, Organizations and Society because it is a top-tier publication outlet at the interface of accounting and management, broadening the methodological and conceptual perspectives in the accounting domain. To better evaluate the findings and provide guidance for accounting scholars in terms of future research, articles published between 1980 and 2020 in top-tier management journals (Academy of Management Journal, Administrative Science Quarterly, and Strategic Management Journal) have been reviewed as well; this stream of the literature has a long tradition of reputation research (George et al. Citation2016) and discusses in depth the well-established definitions and measurements of reputation. This paper includes the management literature because the foremost goal is not to deconstruct and denigrate prior accounting research, but rather to increase accounting scholars’ awareness of alternative definitions and measurements of reputation, thereby offering suggestions for improving future research in this field. We focus on top-tier journals since they are considered to have the highest impact (Lange et al. Citation2011).

The most surprising finding is that there is a lack of a common understanding of what reputation actually means and how to properly measure it. This review documents the fact that (1) the vast majority of accounting papers do not define reputation, (2) the few existing definitions vary greatly, and (3) a mismatch between definition and measurement frequently exists. However, there are also a variety of definitions and mismatching measurements in the management literature. The problem is that the lack of a common understanding of reputation and the mismatch between definitions and measurements of reputation makes it difficult to evaluate the scientific merit of empirical findings. Instead, a common overarching understanding of reputation would both clarify the contributions of new studies and make it easier to test new results more precisely in replication studies. A common understanding of reputation is desirable, especially because stakeholders are often unable to observe the true quality and/or integrity of several company’s agents such as auditors, financial accountants, CFOs, and CEOs. Reputation tends to mitigate information asymmetries and opportunistic behaviour, which in turn may affect shareholders’, creditors’, and other stakeholders’ demand for precise, timely, and transparent financial and nonfinancial information.

Consequently, having a favourable reputation regarding (financial) attributes tends to reduce agency costs, implying lower cost of equity (Cao et al. Citation2015) and less need to reduce information asymmetries otherwise, e.g. by increasing financial reporting quality. Still, companies with a higher reputation are less likely to violate accounting standards, because this would impair their reputational capital (Cao et al. Citation2012). Having a favourable company reputation may also reduce the demand for debt covenants (John and Nachman Citation1985, Tirole Citation2006: 121f.) and for high financial reporting quality, e.g. timely loss recognition (Christensen and Nikolaev Citation2012). Reputation may therefore be especially valuable for companies with high direct or high proprietary costs of disclosure. It is also valuable for companies bearing the names of their founders, since founder-owners benefit especially from reputation (Minichilli et al. Citation2022). Likewise, having a favourable reputation enables the company to employ subjective performance measures in management compensation contracting (Christensen and Demski Citation2003). Objective performance measures have the advantage of being contractible and of reducing the risk of cheating. However, they are often also less informative than subjective measures. Finally, having a favourable reputation regarding product, social, or environmental attributes will compel the company to act responsibly from the staff, consumer, or general public perspective. Again, having a favourable reputation is likely to reduce information uncertainty on the company’s willingness and/or ability to pursue nonfinancial goals. As a result, employees may work for lower wages, consumers may buy at higher prices, and investors may ask for lower returns on capital (Reber et al. Citation2021). From an accounting perspective, having a favourable reputation regarding nonfinancial attributes may be associated with a higher reliability of ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) or sustainability reports, and a lower propensity for green washing. Reputation might be even more important in this field than in financial reporting, as it is still unclear how to determine high reporting quality with regard to ESG issues. Overall, many accounting-related research topics are associated with information asymmetries, and therefore with corporate reputation. A mismatch between the definition and measurement of corporate reputation may bias statistical inferences. Ignoring corporate reputation results in incomplete empirical modelling.

This paper builds on the state of the art in accounting and management research. First, it develops a synthesised conceptualisation of reputation, and second, matches this conceptualisation with the existing measures of reputation. This conceptual framework contributes to the extant literature in three ways.

First, the conceptual framework helps researchers to uncover the various objects and types of assessment that constitute ‘reputation.’ The object or attribute of assessment is any (un)observable company characteristic, such as product and/or service quality, or financial and nonfinancial performance, as well as any related corporate action. The type of assessment refers to how a subject (evaluator) perceives these objects and thereby forms his or her assessment of corporate reputation. This assessment can include the extent to which the company is (1) capable (competence), (2) kind (emotion), or (3) upright (integrity). And, any type of assessment requires that the company is known (prominence). Thus far, the accounting literature has had a blind spot in terms of stakeholders’ emotions towards the company despite their importance for human decision-making and behaviour (Dolan Citation2002). Moreover, the accounting literature has largely ignored nonfinancial attributes of reputation, even though stakeholders become more interested in a company’s social or environmental performance than ever before (e.g. Bucaro et al. Citation2020, Guiral et al. Citation2020, Maniora and Pott Citation2020).

Second, the conceptual framework assumes that a corporation may not have one, but many reputations; this rules out the existence of a single ‘best’ definition of reputation. Some stakeholders may be interested in an emotional assessment, while others prefer to evaluate the company’s integrity or competence. Likewise, the objects of assessment might differ between different stakeholders. Supposedly, investors are mostly interested in the company’s financial reputation, while employees may also consider its kindness and integrity as relatively important. Even the same individual may draw an ambiguous conclusion, as she may evaluate a company favourably with regard to its financial reputation, but less favourably concerning its integrity. The idea of measuring multiple reputations, and the possible interactions between them, has not yet been addressed in the accounting literature.

Third, the conceptual framework proposed here reveals that the existing measures of reputation often do not fit well with (parts of) the synthesised definition or its implicit understandings. Unlike what is suggested by its definition, reputation is frequently not measured as the subjective perception of a company. For example, many studies employ crude financial performance measures, such as market share or company size, to measure reputation. The conceptual framework offers alternative measures that reflect stakeholders’ subjective perceptions directly, and thus measure reputation more accurately.

Previous reviews on corporate reputation provide valuable, but often different insights. For instance, Barnett et al. (Citation2006) find a diversity of definitions, considering reputation as an asset, an assessment or mere awareness. Wartick (Citation2002), Chun (Citation2005) and Walker (Citation2010) distinguish between corporate identity, corporate image, and corporate reputation as well as respective measures. Similar to our approach, Lange et al. (Citation2011) structure the management literature on three different types of reputation (competence, emotion and prominence), which they call dimensions. A more recent review by Ravasi et al. (Citation2018) reveals six perspectives of how company reputation develops over time, stressing its dynamic character (game-theoretic, strategic, macro-cognitive, micro-cognitive, cultural-sociological, and communicative perspective). Based on bibliographic coupling, Veh et al. (Citation2019) identify eight clusters of reputation research in the management literature (corporate reputation, auditing, IPOs, trust, service industries, tourism & hospitality, electronic commerce, entrepreneurial networks). The review by Money et al. (Citation2017) suggests a novel reputation framework that includes the functional, relational, motivational, and third-party causes of corporate reputation, as well as its consequences for stakeholder behaviour. In a similar vein, Ali et al. (Citation2015) conduct a meta-study on the empirical literature on the antecedents and consequences of corporate reputation, and how the results depend on which country and which stakeholder groups have been investigated and which reputation measures have been employed. Other reviews focus on specific aspects of organisational reputation, e.g. in public administration (Bustos Citation2021) and in family businesses (Chaudhary et al. Citation2021).

What the previous reviews have in common is that they mainly target research in management and organisation journals, but (largely) ignore accounting research. For instance, Barnett et al. (Citation2006), Lange et al. (Citation2011), and Ravasi et al. (Citation2018) do not consider any accounting publications; as an exception, Walker (Citation2010) includes two accounting papers, out of 54 papers in total. In other words, corporate reputation has been reviewed inadequately in the accounting literature.

Moreover, most reviews, with the exception of Walker (Citation2010) and Dowling (Citation2016), do not address potential mismatches in the definition and measurement of corporate reputation, but deal with definitional aspects alone and/or other issues. While we acknowledge that some reviews identify different types of assessments (Barnett et al. Citation2006, Lange et al. Citation2011) or state that different stakeholders might come up with different assessments of the company (Wartick Citation2002, Chun Citation2005), our conceptual framework is novel in that it jointly comprises the subjects (who?), attributes (what?), and types (how?) of company assessments, suggesting various conceptual dimensions of corporate reputation in the accounting and management bodies of literature.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 briefly reviews the origins of the term reputation. Section 3 presents the research design and basis for the literature analysis. Section 4 presents a synthesised definition of corporate reputation that integrates the insights of the accounting and management literature reviewed. Section 5 then classifies the corporate measures of reputation used in the accounting and management literature and examines how these measures fit with the synthesised definition of reputation. Section 6 summarises the major findings and identifies future research opportunities for accounting scholars. Section 7 provides concluding remarks.

2. Origins of reputation

The word reputation is of Latin origin (reputationem) and means ‘consideration or thinking over’ (Online Etymology Dictionary Citation2022). The verb reputare (‘to reflect upon, reckon, or count over’) is the composite of re (‘again or repeatedly’) and putare (‘to judge, suppose, believe, or suspect’). The Middle English derivative reputāciǒun eventually became reputation, which is defined as ‘the beliefs or opinions that are generally held about someone or something; a widespread belief that someone or something has a particular characteristic’ (Oxford University Press Citation2022).

A common theme in the extant research in various disciplines is the idea that the reputation of an entity, such as a person or organisation, serves as an information surrogate about the unknown or uncertain capabilities or other characteristics of this entity (Raithel and Schwaiger Citation2015). Reputation refers to social cognitions (knowledge, impression, perceptions, beliefs) of the evaluator (Rindova et al. Citation2010). These cognitions enable evaluators to make inferences about the future intentions and actions of the evaluated entity, thereby affecting evaluators’ intentions and actions towards the evaluated entity such as a company (Shapiro Citation1983). Relatedly, the company’s reputation also allows evaluators to manage cognitive dissonances, e.g. when there is contradicting news about the quality of a new product (Park and Rogan Citation2019).

Reputation operates in various markets, including markets for customers, employees, investors, journalists, or the general public (Basdeo et al. Citation2006, Dowling Citation2016). If a reputation is ‘good’ (‘bad’), then any stakeholder should have a positive (negative) attitude towards and higher (lower) willingness to form a relationship and interact with the evaluated entity, such as a company. Companies with better reputations are also considered to be more trustworthy (Walsh et al. Citation2009). A good reputation is therefore thought to be a valuable resource for a company because it facilitates the favourable actions of stakeholders towards the company. This basic idea marks the inception of a rich body of reputation research in various disciplines.

However, what is actually known about how reputation operates in different markets depends on how researchers define and measure it (e.g. Dowling Citation2016, Lange et al. Citation2011). The main assumption of this study is that the existing knowledge stands on shaky ground because the definitions and measures of reputation are too diverse and fragmented. To examine this assumption, the literature review provides an overview of the existing definitions and matches these definitions with the measures of reputation.

3. Literature analysis

3.1. Literature screening

The literature search used the EBSCO All Database to screen four high-impact and peer-reviewed journals in accounting (Accounting, Organizations & Society, Journal of Accounting & Economics, Journal of Accounting Research, and The Accounting Review).Footnote1 Moreover, the management literature reviewed included articles published in three high-impact and peer-reviewed journals (Academy of Management Journal, Administrative Science Quarterly, and Strategic Management Journal).Footnote2

The literature database includes articles published between 1980 and 2020 because the research on corporate reputation started flourishing from 1980s onward (Barnett et al. Citation2006). The keyword reputation was the only search term. The search covered journals based on their ISSNs, but did not involve any other option or filter. The research team then reviewed each paper where the term reputation appeared anywhere in the title, abstract, or main text (324 papers). Thirty-eight papers were excluded because they did not discuss reputation in terms of corporate, company, or organizational reputation, but rather in terms of an individual’s reputation (e.g. the reputation of an employee or manager). In addition, another 113 papers were excluded because they did not include reputation at least as a minor variable in the conceptual framework or model, but rather mentioned reputation merely as a supportive argument for their main research ideas. The final database included 173 articles (68 accounting articles and 105 management articles). Within the field of accounting, almost all papers in our database related to subjects of auditing or financial reporting, while reputation papers in the fields of managerial accounting and tax accounting were rare. breaks down the articles by journal and by period.Footnote3

Table 1. Overview of articles reviewed in the accounting and management literature.

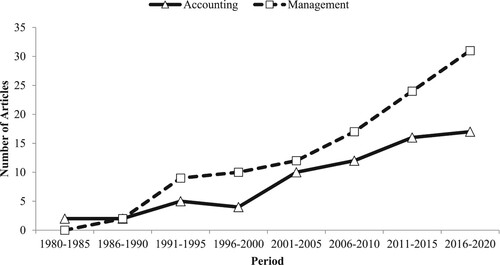

The first study on reputation dates back to 1983 and was published in The Accounting Review (Wilson Citation1983). Since then, the number of articles focusing on reputation has increased (). While there was a significant increase in accounting publications after 2000, the management domain experienced a spike in related publications from 1991 onward, and especially after 2005. On average, there has been a steadily growing interest in this subject in management journals over the last decade.

Figure 1. ‘Reputation’ articles of seven top-tier journals in accounting and management in 5-year periods.

Note: displays the number of articles on corporate reputation published in four top-tier accounting journals (Accounting, Organizations and Society, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Journal of Accounting Research, and The Accounting Review) and three top-tier management journals (Academy of Management Journal, Administrative Science Quarterly, and Strategic Management Journal) from 1980 to 2020.

3.2. Overview of the definitions and measurements of reputation

During the second phase, the research team summarised each article’s definition of reputation (if available) and measurement of reputation (if the research was empirical). The Web Appendix lists all definitions of reputation and its measurements. Most of the studies were empirical, and investigated reputation as a predictor (98 of 173 articles). Another large group of empirical studies focused on reputation as an outcome variable (57 articles). Reputation was used as a mediator (9 articles), moderator (9 articles), or control variable (7 articles) in only a few empirical studies.

Surprisingly, only 69 of the 173 articles defined reputation, and strikingly, the percentage of papers that defined reputation was much lower in accounting (22%, or 15 out of 68 papers) than in the management domain (51%, or 54 out of 105 papers). It is possible that accounting scholars do not define reputation because they assume that a common definition exists. A common definition and measurement of reputation would be useful to distil the undisputed insights and to easily interpret contradictory findings. However, among the studies that defined reputation, a variety of definitions existed: there were 15 different definitions of reputation in accounting and 30 different definitions in management journals (see Tables A1 and A2 in the Web Appendix). This finding refutes the implicit assumption that a common definition exists.

Concerning reputation measurement, many studies have used either an available reputation scale from secondary data resources (58 papers) or hand-collected data by using a modified measurement scale from previous studies (20 papers). Many authors have even designed their own measurements (40 papers) (see Tables A3 and A4 in the Web Appendix).

Why do so many different definitions and measurements exist? One answer may be that individuals and stakeholder groups differ in the type of company information (attribute) they are looking for, and differ in their capabilities to obtain access to this information. Moreover, individuals and stakeholders may differ in how they assess this information. For example, many customers are more concerned with product quality and are more likely to assess companies emotionally, whereas many investors are more concerned with a rational assessment of profitability. However, even investors’ decisions may depend on emotions (Frydman and Camerer Citation2016, Hirshleifer Citation2015), which can also be directed towards certain companies, as the research on ‘glamour stocks’ has indicated (Campbell et al. Citation2010). In sum, even within a group of investors, demand depends on multiple factors. Reputation is therefore defined and measured very differently, depending on the researcher’s focus.

Second, some actors (e.g. researchers, consulting companies, and market researchers) may have incentives to define and measure reputation differently. They can gain benefits from convincing others to believe in and act according to ‘their grasp of reputation.’

Third, the existence of company-level data on reputation, such as Fortune’s Most Admired Companies ranking or other easily available proxies for reputation (e.g. company size), may entice researchers to adopt a definition of reputation that matches their measure, even though previous work defines reputation differently.

The intermediate results of the literature review confirm the initial assumption that the definitions and measures of reputation are diverse. The following sections therefore aim to extract the common basis of the definitions and measurements of reputation in the accounting and management literature, which will help scholars understand each field’s view of reputation and identify the commonalities and discrepancies between the two fields.

4. Conceptualizations of reputation: integrating accounting and management literatures

4.1. Reputation in the accounting literature

Only 22% (15 out of 68) of accounting papers that deal with corporate reputation provided a definition of reputation, while 50% (34 out of 68) of empirical accounting papers did not define reputation, but only measured it.Footnote4 There were some empirical papers that dealt with reputational issues, without explicitly defining or outlining the measurement of reputation.Footnote5 The literature database also includes a few microeconomic studies that provided definitions of reputation (but no measurements). Table A1 in the Web Appendix provides a more detailed overview. The review of the various definitions of reputation indicates considerable differences in the accounting literature.

Microeconomic papers by Wilson (Citation1983), Meng (Citation2015), Corona and Randhawa (Citation2018), and Rothenberg (Citation2020) defined reputation relatively narrowly as an updated assessment of an unobservable company characteristic conditional on a past outcome.Footnote6 For instance, according to Wilson (Citation1983) as well as to Corona and Randhawa (Citation2018), reputation is the investors’ probability assessment of a company assets’ true value (of company quality, respectively), conditional on the audit firm’s report (on admitting bad financial reporting decisions). Rothenberg (Citation2020) related an audit firm’s reputation to investors’ beliefs about the audit firm’s ability to detect a company in bad financial condition. These beliefs are updated after the audit report has been released. Similarly, Meng (Citation2015) defined a financial analyst’s expert reputation as an updated belief about an analyst expert type, conditional on the validity of analyst forecasts. The empirical study by Chaney and Philipich (Citation2002, p. 1221) more loosely stated that an ‘auditor’s reputation is directly related to the perceived and actual levels of quality reflected by the auditor’s report.’ It is also noteworthy that these definitions only deal with the assessment of financial attributes or objects.

A second group of definitions is more general both in terms of the assessment objects (i.e. company characteristics) and the subjects of the company assessment (i.e. evaluators). Unlike the above group of definitions, this group of definitions is not explicitly based on past corporate actions or outcomes. Very generally, DeJong et al. (Citation1985, p. 89) defined reputation as follows: ‘An agent’s reputation is simply a principal’s expectation regarding an agent’s future performance.’ The definitions by Fombrun (Citation1996, p. 37)Footnote7 and Kim et al. (Citation2018) referred to stakeholders’ or the public’s perception of the company in general and of its capability to deliver high-quality products and services, respectively. In addition, deHaan (Citation2017) related reputation more narrowly to ‘perceptions of quality.’

There is one definition employed by Chalmers and Godfrey (Citation2004) and based on Freeman (Citation1984) that is not associated with assessments of corporate characteristics, actions, or outcomes. These authors defined reputation as ‘the firm’s relative success in fulfilling the expectations of multiple stakeholders’ (Chalmers and Godfrey Citation2004, p. 101), interpreting corporate actions as a response to stakeholder beliefs.

Most definitions of reputation in accounting refer to the competence of a company with regard to financial or product attributes. Some definitions refer to the integrity of a company. For instance, Chakravarthy et al. (Citation2014, p. 1330) defined corporate reputation as ‘stakeholders’ collective expectation about management’s intent and ability to fulfill its commitments.’ In a similar vein, according to the microeconomic study of Corona and Randhawa (Citation2018), investors’ valuation is determined by whether an audit firm admits to bad financial reporting decisions or not. Studies measuring audit firm reputation by ‘Big N’ status or audit firm size indirectly assume that larger audit companies are less likely than smaller audit companies to collude with the client company at the expense of shareholders because larger audit companies have more clients, and thus they have more clients to lose if they are involved in an accounting scandal.

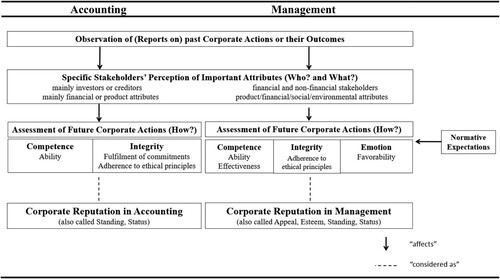

summarises the various definitions in the accounting literature and offers a synthesised view. This figure also provides a similar synthesis of the management literature’s view on reputation explained in the next section. This section compares the management literature’s view on reputation with that provided in the accounting literature.

4.2. Reputation in the management literature

In management, reputation represents an organisation’s overall appeal (Fombrun Citation1996, Lange et al. Citation2011) or attractiveness (Fombrun Citation2012) relative to that of its rivals. A ‘good reputation’ indicates that a company is highly esteemed and receives high regard (Dollinger et al. Citation1997, Merriam Citation1961). Reputation represents the audience’s perception of a company’s key characteristics (Saxton Citation1997) and signals the company’s status to constituents (Fombrun and Shanley Citation1990). Beyond these general descriptions of reputation, this review reveals a nuanced view on reputation. Based on 30 original definitions in the management articles reviewed (see Table A2 in the Web Appendix), the right chart in above represents the synthesised conceptualisation (or model) of reputation. The following paragraphs elaborate on each element of this model, starting from the top.

The first part of the model – ‘Observation of (reports on) past corporate actions or their outcomes’ – reflects how past actions or outcomes and the communication about it meet prior expectations of a company’s key constituents and form perceptions about certain attributes ascribed to the company over time (Fombrun Citation1996, Jensen et al. Citation2012, Weigelt and Camerer Citation1988).Footnote8 A widely cited paper by Weigelt and Camerer (Citation1988) includes a definition that emphasises the role of ‘past action’ from which stakeholders infer a ‘set of attributes’ ascribed to a company. The authors’ key argument is that the accumulation of the historical behaviours of an actor forms his or her reputation, which means that a stakeholder repeatedly observes and assesses the behaviour of the company. If the company’s past behaviour is stable or reveals a pattern (e.g. the company always keeps its promises), then the stakeholder infers or believes that the company has a specific attribute (e.g. reliability). This conceptualisation of reputation is inherently dynamic and based on repeated interactions between the company and its stakeholders.

A second element of the model concerns the attributes of reputation. The management literature explicitly states that reputation can be assessed on basically any attribute that is a source of status (Deephouse and Carter Citation2005). The observed past actions and characteristics of the company, however, fall into specific domains that build a categorisation of these attributes. The management literature frequently discusses four general pillars of attributes: products (Hall Citation1992, Citation1993), financial assets, social responsibility, and environmental issues (Barnett et al. Citation2006, Fombrun and Shanley Citation1990).

In the third step, stakeholders make predictions about the company’s likely future behaviour (Fombrun Citation1996, Lange et al. Citation2011, Wilson Citation1985) based on their knowledge about and perceptions of the various attributes of the company and guided by subjective normative expectations. Stakeholders have specific expectations about how a company should behave. Although normative expectations are more closely related to legitimacy, management scholars also consider them an element of reputation formation, since comparisons among corporations cannot be fully separated from normative expectations (Deephouse and Carter Citation2005). Similar to value expectations (e.g. a company is expected to outperform financially in the future because it has consistently done so in the past), normative expectations also serve as reference points for assessments. For example, during a corporate crisis, stakeholders expect a company to accept responsibility for its failure (Bundy and Pfarrer Citation2015). If the company’s behaviour matches (vs. misses) this norm, then the resulting assessment is usually more positive (vs. negative). For example, if the company shows an accommodative response to a severe product failure, then it satisfies social expectations about justice, sincerity, and fairness (Pfarrer et al. Citation2008). Accordingly, the reputation assessment of this company is positive (Raithel and Hock Citation2021), and allows the stakeholder to assume that the company will meet his or her expectations in the future and in case a similar event occurs.

Reputation assessments consider different characteristics, which include the extent to which a company is capable (competence), kind (emotion), and upright (integrity). Those characteristics are consistent with the three aspects of social evaluations suggested by the social-psychological literature (Tost Citation2011, Pollock et al. Citation2019): namely, rationality, emotion, and morality. It is conceivable that a company’s reputation may differ across the different types of assessments.

Similar to the accounting literature, the management literature addresses stakeholders’ assessments of a company’s competence (Raithel and Schwaiger Citation2015), i.e. perceptions of companies regarding financial aspects such as corporate asset use, financial soundness, or long-term investment value are important (Petkova et al. Citation2014, Teece et al. Citation1997). Other authors have emphasised signals of excellence, such as product and service quality (similar to the accounting literature), vision and leadership, and the workplace environment. Furthermore, Rindova et al. (Citation2005, p. 1033) stated that reputation is based on ‘stakeholders’ perceptions about an organisation’s ability to create value relative to competitors.’ Philippe and Durand (Citation2011) referred to reputation as the perception of a company’s audience about the company’s ability to provide value. This view might include a company’s ability to withstand shocks (Gao et al. Citation2017) and might also reflect the organisational effectiveness perceived by different stakeholders (Tsui Citation1984). These signals of excellence share a common theme of determining whether stakeholders are confident about a company’s capabilities.

The extant research shows that evaluators tend to anthropomorphize objects and form attitudes towards these objects based on evoked emotions. Some management scholars acknowledge this view and propose that stakeholders assess a ‘company’s character’ based on the ‘feeling-right’ experiences they attribute to a company (Love and Kraatz Citation2009). Such emotions held by stakeholders (i.e. affective evaluations or ‘likeability’) can also help the company achieve competitive advantage (Hall Citation1992). Alternative conceptualizations and measures of reputation therefore place weight on the emotional aspects of reputation (Pfarrer et al. Citation2010, Raithel and Schwaiger Citation2015).

As a third type of reputation assessment, two studies have emphasised the role of business integrity (Jensen and Roy Citation2008, Park and Rogan Citation2019). These studies defined integrity as adherence to ethical and moral principles. A positive reputation in terms of business integrity bolsters trust in an organisation and therefore exchanges partners’ willingness to form a relationship. Interestingly, these studies refer to the audit industry as a prime example of the importance of business integrity.

Management literature frequently discusses prominence in conjunction with reputation. Prominence is a necessary condition for evaluators to assess a company’s reputation. Any assessment requires the evaluator to have a baseline of knowledge about the company. Prominence relates to how much awareness and recognition a company has (Delbridge Citation1982, Gao et al. Citation2017, Rindova et al. Citation2005) and to the level of familiarity stakeholders have with the organisation (Lange et al. Citation2011, ‘being known’). Thus, different to Lange et al. (Citation2011), we consider prominence not to be a type of reputation, but rather a determinant of the impact of reputation. The more stakeholders are aware of a company, the stronger we assume the impact to be. In that sense, we can think of prominence as a continuous rather than a binary concept.

Reputation is in the eye of the beholder; it is a genuinely subjective concept for at least three reasons. First, stakeholders usually have different information on corporate actions or outcomes. Second, there is very limited research in accounting on whether financial and nonfinancial stakeholders assess the company’s kindness rather than its competence or integrity and how these assessments interact and evolve over time. Different stakeholders assess different attributes: Some may assess the company’s financial performance, while others are interested in its environmental achievements. Thus, the conceptualisation of reputation suggested in this paper implies that a company has many reputations, rather than one. Some literature acknowledges that corporate reputation might be assessed differently by different stakeholders (e.g. Wartick Citation2002, Chun Citation2005, Walker Citation2010). Third, even the same stakeholder may come up with diverging assessments, e.g. they may consider a company to be competent, but not kind or ethical.

Management papers rarely refer to definitions outside their own literature, e.g. Rindova et al. (Citation2006) and Petkova et al. (Citation2014) refer to Shapiro (Citation1983), and Ertug and Castellucci (Citation2013) refer to Wilson (Citation1985). However, none of them quotes a definition originating from a top-tier accounting journal. The accounting literature cites definitions from management slightly more often, e.g. Chalmers and Godfrey (Citation2004) refer to Freeman (Citation1984), Cho et al. (Citation2012) to Fombrun (Citation1996), and Hodge et al. (Citation2006) to Weigelt and Camerer (Citation1988). Overall, the bodies of literature seem to be distinct, and spillovers appear to be rather limited. The question arises as to whether this also holds for the measurements of reputation.

5. Measurements of reputation

5.1. Overview of measurements

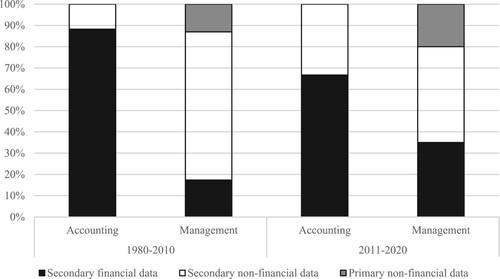

We first provide basic descriptive evidence on how frequently different reputation measures are used in the top-tier accounting and management journals, and how this use develops over time (see and ).Footnote9

Figure 3. Frequency of certain reputation measures in top-tier accounting and management journals in the periods 1980–2010 and 2011–2020.

Note: shows the relative frequency of reputation measures based on (a) secondary financial data, (b) secondary non-financial data and (c) primary non-financial data, sorted by accounting and management papers and sorted by the 1980–2010 and 2011–2020 periods.

Table 2. Number of accounting (A) and management (M) papers applying different types of measurements presented.

reveals that about 76% of the accounting papers employing corporate reputation measures focus on secondary financial measures, while 58% of the management articles use secondary nonfinancial measures. Primary nonfinancial measures are barely considered, and if they are, it is only by management journals. While the Fortune ranking is very popular within the management domain, size proxies (market share, Big N auditor) are preferred measures in the accounting literature, even after the major accounting scandals in 2001 and 2002. However, the proportion of accounting papers employing size measures shrinks after 2010, also because secondary nonfinancial measures are used more frequently.

Over time, we observe a slight convergence between the bodies of literature (). Secondary financial measures remain dominant in accounting, but the share of papers employing them decreases from 88% in the 1980–2010 period to 67% in 2011–2020. In the recent decade, accounting papers use secondary nonfinancial measures more often, while they become less important in the management literature (70% share in 1980–2010 and 45% share in 2011–2020). In contrast, secondary financial measures are employed more frequently, with a focus on market share and venture capital reputation. Surprisingly, the latter is ignored by top-tier accounting papers.

Despite noticing some convergence over time, spillovers between the bodies of literature seem to be rather limited. We rarely find papers that use measures developed ‘by the other side’. The measure on underwriter reputation by Carter and Manaster (Citation1990), published in a finance journal, has been employed by Pollock and Rindova (Citation2003) and Ragozzino and Reuer (Citation2011). Sometimes, both bodies of literature use measures developed outside academia, such as credit ratings (Ferguson et al. Citation2000, Martin and Roychowdhury Citation2015) or the Fortune ranking (Fombrun and Shanley Citation1990, Kim et al. Citation2018).

(see the following sections 5.2–5.4) integrate the measurements of reputation with its existing definitions (cf. ), differentiating between the three categories of measures. For two reasons, the scope of these tables comprises both reviewed literatures. First, accounting scholars obtain an overview of ways reputation has been operationalised in management, some of which may offer advantages over those applied in accounting. Second, accounting researchers wishing to adopt alternative or broader views of reputation (cf. ) can use to identify the most appropriate indicators for their research projects.

Table 3. Match between the secondary financial measures and definitions of reputation.

Table 4. Match between secondary nonfinancial measures and definitions of reputation

Table 5. Match between the primary nonfinancial measures and definitions of reputation

The columns on the left in break down the most important and frequently used indicators into these categories and types; offer a short description of the measurement as well as counts; and cites empirical studies from the accounting and management bodies of literature.Footnote10 The following sections discuss the three major measurement categories, and how each specific measurement type covers the definition of reputation. For this purpose, the rightmost columns of display how well each indicator matched the synthesised definition of reputation (cf. ). Each indicator is therefore linked to the attributes (financial, product, social, and environmental) of reputation and the types (competence, emotion, and integrity) of reputation. indicate whether, from our perspective, an indicator fully (✓) or partially covers (o) attributes and types of reputation.

5.2. Secondary financial data

Three general types of secondary financial data have been used as proxies for reputation – company size, financial scores, and other measures which are mostly based on financial events ().

Company size. The indicators in this group usually rely on the financial position of a company within its market. Ball et al. (Citation2008) and Bushman and Wittenberg-Moerman (Citation2012) assigned a high reputation ‘score’ to a lead bank in terms of its market share in the syndicated loan market. In a similar sense, the reputation of venture capitalists is measured by the market capitalisation or market share of the IPOs they back (e.g. Krishnan et al. Citation2011, Nahata Citation2008, Tian et al. Citation2016). Audit firm reputation has sometimes also been linked to an audit firm’s market share (Chen et al. Citation2013, Francis et al. Citation2005, Weber et al. Citation2008). Many auditing papers have related audit firm size to reputation, generally assigning a more positive reputation to Big 4 (Big N) audit companies, such as Deloitte, EY, KPMG, and PwC (e.g. Craswell et al. Citation1995, Hope and Langli Citation2010, Khurana and Raman Citation2004, Kim et al. Citation2012). Company size has also been used to measure lender reputation (Martin and Roychowdhury Citation2015).

The underlying assumption is that reputation is increasing with company size. Although reputation is an important driver of future financial performance and ultimately company size (e.g. Raithel and Schwaiger Citation2015), the two variables are not the same. Applying the ‘size logic,’ a highly profitable company that follows a niche market strategy (e.g. a sports car manufacturer) has a bad reputation since the market share of this company is lower than that of a competitor producing for the mass market, even if the profitability of the mass market manufacturer is low. Conversely, it is impossible for a market-leading company to have a bad reputation, e.g. if this market dominance is the result of unfair business practices or (quasi-)monopolistic market conditions. Both views are obviously false. Hence, company size is only a very imprecise proxy for reputation in general, and can only partially cover (financial) reputation.

Financial scores. Other authors developed more sophisticated financial scores designed to assess a company’s financial condition, operating performance, and policies, and form opinions about its risk management strategies based on information from published reports. Such financial scores include, e.g. long-term S&P credit ratings (Martin and Roychowdhury Citation2015). The underlying rationale is that a financial score is correlated with reputation. This relationship is plausible and well documented in the literature: stakeholders’ awareness of past financial performance affects their reputation perceptions (e.g. Raithel and Schwaiger Citation2015, Roberts and Dowling Citation2002). However, the use of financial scores limits the research scope to financial attributes and the ‘competence’ type of reputation. Still, financial scores are better able than size measures to capture the subjective assessments of stakeholders.

Financial events. Some specialised indicators of reputation based on ‘financial events’ also exist. A few scholars have investigated reputation as a dynamic concept, where ‘reputation stock’ accumulates in light of the number of previous business transactions (Ball et al. Citation2008).Footnote11 Other authors assign a bad reputation to a company or an audit firm in the event of a financial restatement or financial misrepresentation, partly resulting in decreasing market shares or stock pricesFootnote12 (Desai et al. Citation2006, Marquardt and Wiedman Citation2005, Swanquist and Whited Citation2015, Files et al. Citation2019).Footnote13 Chaney and Philipich (Citation2002) captured a loss of audit firm reputation by a reduction in the client company’s stock price. These indicators share many of the characteristics of the other indicators based on secondary financial data, most notably their focus on financial attributes and ‘competence’ type of reputation.

Critical appraisal. In the accounting literature, scholars most frequently use secondary financial measures of reputation such as market share and company size. One reason might be related to the fact that such measures are objective. Another reason might be that these measures are easily available, enabling scholars to analyze large samples across multiple industries over long time horizons. Thus, empirical evidence is more robust, and possesses higher external validity. But this advantage comes at the cost of higher measurement error, lower internal validity, and limited conceptual broadness. As argued above, financial performance is related to the competence dimension of reputation. But reputation measures based on financial data are not perfectly correlated with the competence dimension of reputation as perceived by stakeholders (e.g. Raithel and Schwaiger Citation2015, Roberts and Dowling Citation2002). Measures of reputation based on secondary financial data are likely to be biased accordingly. This bias affects model estimates (Meijer et al. Citation2021). For example, assuming reputation is used as a predictor of some outcome in a regression model, the reputation measurement bias creates endogeneity because the residual of the regression model is then correlated with the regression model outcome. Consequently, the model inflates type II error by underestimating the true relationship between reputation and the outcome. It goes without saying that this problem, as well as other endogeneity issues, can be fixed by using instrumental variables.Footnote14 However, such variables are often unavailable or they introduce severe estimation bias if chosen improperly (Larcker and Rusticus Citation2010).

Aside from endogeneity issues, secondary financial data is not suitable to proxy nonfinancial reputation, due to weak correlation. Some researchers in management even use information that is orthogonal to financial measurements as a measurement for nonfinancial reputation dimensions (e.g. Raithel and Schwaiger Citation2015, Roberts and Dowling Citation2002).

5.3. Secondary nonfinancial data

The measurement of reputation in the accounting literature is sometimes predicated on secondary nonfinancial data (). Such indicators are well established in the management literature. In particular, survey-based measures of reputation have found broad applications in management. Two other categories of measurement based on secondary nonfinancial data are also notable. Some reputation rankings are highly specialised, focusing on a narrow aspect of reputation. Other measures focus on (negative) events that should have an effect on a company’s reputation.

Broad, survey-based rankings. Herremans et al. (Citation1993) and Kim et al. (Citation2012) employed the Fortune ranking or Most Admired Company survey, conducted each year among high-ranking executives, directors, and financial analysts in the US, addressing quality (management; products or services), innovativeness, investment value, financial soundness, employer-related aspects, community and environmental responsibility, and corporate assets. Hence, this measure adopts a broader view of reputation, but still emphasises the competence type of reputation. By surveying external observers who are familiar with the company they rate, this indicator reflects these observers’ perceptions of attributes and expectations regarding future corporate action that constitutes reputation. Although this measure captures both the financial and nonfinancial attributes of reputation, it still emphasises and is biased towards the former ones. However, papers in the management literature have discussed empirical approaches that can separate financial and nonfinancial reputations (e.g. Raithel and Schwaiger Citation2015, Roberts and Dowling Citation2002). Another problem of the Fortune ranking is that ranks are subject to the selected ranking criteria and the assumed weights of the criteria. Furthermore, since the Fortune ranking is an aggregated measure with pre-defined weights of the underlying measurement items, it does not fit our view that different stakeholders may assess the companies’ attributes differently. Finally, even though the Fortune ranking is quite broad, it ignores the assessments of many other stakeholders such as lenders and customers.

A similarly broad measure, the Reputation Quotient, provided by the Reputation Institute/Harris Interactive, also uses external stakeholders to rank companies based on emotional appeal, products and services, workplace environment, vision and leadership, financial performance, and social responsibility (e.g. Boivie et al. Citation2016, Haleblian et al. Citation2017, Pfarrer et al. Citation2010). The advantage of the latter is that it places slightly more emphasis on the emotional type of reputation (3 out of 20 measurement items).

Specialized rankings. Beyond these broad survey-based rankings, specialised reputation rankings, such as KLD’s ranking (e.g. Muller and Kräussl Citation2011) or Newsweek’s Greenest Companies ranking (e.g. Cho et al. Citation2012), allow researchers to capture specific reputation attributes such as environmental or social performance. Although the KLD measure is also survey-based, it follows a different approach because the survey is not sent out to external stakeholders, but rather to the companies themselves, which have to self-report on a variety of performance indicators.Footnote15 Thus, the KLD measure is not a stakeholder’s assessment. Other researchers have used binary variables, which measure whether a publicly listed company is included in specialised stock indices such as the Dow Jones Sustainability Index (e.g. Cho et al. Citation2012), as proxies for reputation. Such proxies can only distinguish between a ‘good’ and a ‘bad’ reputation, and therefore lack the many advantages of scalar indicators. Furthermore, without detailed information about the underlying stock selection mechanism, it is unclear what attributes or types of reputation are being covered. Finally, such specialised stock indices frequently employ general sustainability or moral principles, and therefore exclude whole industries (e.g. gambling, tobacco, oil and gas). In these cases, the reputation measure based on stock index membership is not a company-specific measure, but merely an industry-specific measure. Such measures only allow for inferences about the effects of reputation in cross-industry settings, rather than for intra-industry settings.

Nonfinancial events. Two accounting studies exist that measured reputation in atypical ways. Cook et al. (Citation2020) measured audit firm reputation by the misconduct of an audit firm’s client company that is not related to financial reporting, such as complaints about unsuitable investments or excessive trading. Misconduct can be related to violations of civil law, criminal law, or public law. The second study (Cen et al. Citation2018) measured the loss of a supplier’s reputation as perceived by its customers by whether the supplier was involved in litigation. This involved three types of litigation: (a) accounting malpractice and other violations of securities laws; (b) breach of contract, product and service liability, operational malpractice, and social responsibility; and (c) matters related to patents and copyright, and antitrust violation. Using such events as a proxy for reputation only allows researchers to obtain limited information on the effects of reputation. It is unclear whether and how these events eventually shape reputation, because contextual factors or the company’s response to the negative event also play an important role (e.g. Bundy and Pfarrer Citation2015, Raithel and Hock Citation2021).

Critical appraisal. Management scholars most frequently use broad survey-based rankings such as the Fortune ranking (see ). One reason for this is that, in management, definitions of reputation are broader and include nonfinancial attributes (see ). Another reason is that management scholars often emphasise subjectivity regarding company reputation, which requires a direct measure of the perception of stakeholders (e.g. Lange et al. Citation2011). The survey-based measures usually have higher internal validity, because the development of the underlying questionnaire and measurement items is based on a reputation definition and (should have) followed a rigorous measurement validation procedure (e.g. Fombrun et al. Citation2000). The measures have multiple items, and reputation is modelled as a latent variable, which results in smaller random measurement error. Furthermore, the broad survey-based measures (unlike the specialised nonfinancial and financial measures) exhibit higher conceptual overlap with the broad reputation definition, improving content validity. These advantages could reduce type II error (if reputation is the predictor in the model) and type I error (if reputation is the outcome in the model). However, company coverage is limited, and sample sizes are usually smaller compared to studies that apply reputation measures based on secondary company data. Smaller samples reduce the ability to detect effects. Furthermore, these smaller samples usually suffer from selection bias, because survey-based measures generally cover only a sub-set of companies which qualify according to some pre-selection criteria such as revenue (e.g. Fortune rankingFootnote16). As a result, survey-based reputation rankings are more likely to include larger, well-known, and more established companies. This limited representativeness for the company universe not only reduces external validity, but, above all, introduces selection bias, which can distort regression estimates. It is advisable for researchers to adjust for such selection bias accordingly by using, e.g. Heckman-type corrections (Lennox et al. Citation2012).

5.4. Primary nonfinancial data

Only a few studies collected primary nonfinancial data, and these studies were divided into two categories (): they focused either on designing surveys or coding media data.

Survey-based ranking. Raithel and Schwaiger (Citation2015) surveyed the general public (i.e. a representative sample of the German population) on their perceptions of the 30 largest publicly listed companies in Germany. This survey applied a measure of reputation that covered the ‘emotion’ and ‘competence’ types of reputation, using six items in a questionnaire. In another study, Saxton (Citation1997) let managers rank partner companies according to an expanded version of Fortune’s measurement of reputation.

Media-based ranking. Studies that collect media data to measure the attention and/or tonality of a company’s coverage in the media are easier to replicate. For example, Wei et al. (Citation2017) coded media data and calculated a tonality score for a company’s actions that past research indicated should increase/decrease a company’s reputation. Similar to survey-based measures, media-based measures allow researchers to adapt their coding scheme to their own definitions of reputation. However, these indicators only quantify reputation indirectly. Although the media can have an impact on or reflect the reputation perceptions of stakeholders, such media-based measures do not equate to actual perceptions of reputation. Moreover, the media tends to focus on well-known companies, resulting in a self-selection bias.

Critical appraisal. The proprietary survey-based and media-based reputation rankings have as yet only been used by management scholars. The proprietary survey-based measures have the advantage that researchers can design and apply a measure of reputation that fits the desired definition of reputation. However, these measures are extremely demanding. The costs of collecting data for a sufficient sample of companies over a sufficiently long period are very high. This limitation also makes it difficult for other researchers to replicate the findings. The media-based reputation rankings are less demanding, and have a number of benefits compared to any of the secondary reputation measures. Researchers can build a context-capturing topic and sentiment classification model that is aligned with the definition of reputation. Fully automated, natural language processing methods make this approach less time-consuming, less costly, and widely available compared to other methods (Siano and Wysocki Citation2021). Methodological advancements in text processing and deep learning may allow for text-based measures of reputation that are reliable, valid, and representative for the company universe if the data collection process includes a broad range of data sources; these may include social media chatter about the company that reflects stakeholders’ perceptions of that company. Moreover, this data can track company reputation in real time, giving researchers more opportunities compared to measures that are only available on a periodical basis, such as most survey-based reputation measures (Rust et al. Citation2021).Footnote17

6. Implications for accounting scholars

This analysis of the literature reveals that many accounting papers do not define corporate reputation and if they do, they emphasise financial attributes and the ‘competence’ and ‘integrity’ types of reputation. Furthermore, measures of reputation frequently do not match the conceptualisation of reputation very well. Based on the insights of a relatively broad body of literature in the management domain concerning reputation, this study has developed a synthesised definition of reputation and matched it with measures of reputation. The next sections translate these findings into four important implications for accounting scholars, and discuss the limitations of our study.

6.1. Defining reputation

Good research requires a clear definition of the terms that are crucial to the research project. However, the empirical accounting literature very often fails to define the term ‘corporate reputation,’ even when it plays a significant role in the related analysis. However, in the absence of a definition, different readers are likely to attach different notions to the term, which could impair the correct interpretation of the subsequent arguments and research findings. Consequently, studies on corporate reputation should provide a precise definition, especially as there is obviously no single, universally accepted definition available. The reputation model synthesised in this paper provides an overview of which types and attributes of assessment the term ‘reputation’ might refer to, and clarifies the position of the own study in reputation research.

6.2. Applying a measurement of reputation that matches its definition

There is frequently a mismatch between the theoretical concept of reputation and the measurements employed, which often disregards stakeholders’ perceptions of reputation. The conceptual framework developed in this study (see above) shows a variety of alternative, possibly more suitable, reputation indicators. This framework offers two implications. First, if the indicator employed is highly specific, then the definition and the theoretical arguments about the effects of reputation must also correspond to that high specificity. Second, researchers can and should employ alternative measures of reputation addressing different attributes or types of corporate reputation.

Only a few accounting papers employ a (subjective) assessment of a company or its capabilities (e.g. Herremans et al. Citation1993, Kim et al. Citation2012, Kim et al. Citation2018). Instead, corporate reputation is often quantified using secondary financial measures, such as company size, which are often weakly related to reputation, but might be useful to increase sample size and to meet requirements on the study’s external validity. If such measures are only imperfectly correlated with (financial) reputation, researchers could improve internal validity by combining several financial proxies, which are highly correlated with (financial) reputation, into a so-called latent variable. Such latent variables can reduce random measurement error, and thus, depending on the role of reputation in the model, reduce type I and II errors (Meijer et al. Citation2021). Another remedy that can safeguard internal validity is to also collect data for subjective assessments of reputation (e.g. Fortune ranking). Although the company sample will be smaller and suffer from selection bias, the researcher could add more credibility to empirical findings by showing that the effects are robust to a different reputation measure or by restricting the explorative power of the study to specific attributes or types of corporate reputation rather than reputation per se (see above). Finally, depending on the research question, another way to secure internal validity is to augment the secondary data study with experimental studies (e.g. Raithel and Hock Citation2021).

6.3. Replicating prior reputation research to validate existing knowledge

Prior empirical research has employed measurements that covered only a specific aspect of a company’s reputation or vaguely addressed it. In other words, there is a lack of studies that measure reputation as stakeholders’ subjective assessments of a company’s attributes. Survey-based measures are more likely to capture the nuances of stakeholders’ perceptions about reputation than secondary financial measures are. Thus, a basic question arises as to whether the results in these papers would still hold if different and potentially more appropriate measurements of reputation were employed, e.g. survey-based audit-company (branch) reputation or survey-based bank reputation, as opposed to audit-company size or the market share of a given bank, respectively. In addition, prior studies may be replicated, as reputation is a dynamic concept. Assessments of a company’s actions or outcomes change with new pieces of information. There is also a lack of longitudinal studies in accounting that consider how a change in reputation affects a company’s performance in financial, labour, and product markets in the long run.

6.4. Expanding academic knowledge about reputation effects

This literature review has revealed that the basic structure of the reputation model in accounting is similar to that discussed in management: The stakeholder’s (1) observation of past corporate actions or their outcomes affects his or her (2) knowledge about and perceptions of company characteristics (attributes), thereby influencing his or her (3) expectations about (assessment of) the future actions of the company. Along this similar basic structure, the literature review also revealed four important differences between the accounting and management literature, which offer research opportunities for accounting scholars.

1. Adding nonfinancial attributes to financial and product attributes. The management literature distinguishes, beyond product and financial attributes, among nonfinancial, social, environmental, and performance attributes. This finding does not mean that the accounting research, in general, ignores the other domains, but the discussion of reputation in the accounting literature does not explicitly consider the importance of the other attribute categories, and it is therefore narrower compared to the management literature. There is growing but still sparse accounting research on the social and environmental attributes of a company’s reputation, which is surprising because nonfinancial stakeholders are not the only individuals interested in a company’s social or environmental ‘performance.’ Although there is a growing body of studies in the accounting domain on corporate social and environmental performance, the link to reputation research in accounting is not yet well established. Interestingly, several accounting studies have employed indicators of reputation that have indeed covered these neglected attributes (Herremans et al. Citation1993, Kim et al. Citation2012, Cen et al. Citation2018). Expanding the scope of reputation research to include nonfinancial matters is certainly an interesting research avenue, especially because financial investors and analysts increasingly care about these issues (e.g. Luo et al. Citation2015). There are many research questions that come to mind. How do social and environmental reputations affect the cost of equity and the cost of debt? Are financial and nonfinancial reputations substitutive or complementary? For companies committing financial fraud, are fines, damage compensation, and capital market reactions less severe if they have good social and/or environmental reputations?

2. Adding ‘emotion’ to the ‘competence’ and ‘integrity’ domains. In the accounting literature, reputation assessments are centred around a company’s competence, e.g. its ability to deliver high-quality products or services (e.g. audit quality) and the company’s integrity, that is, its ability to fulfil its commitments and, more generally, to adhere to ethical principles. The management literature has emphasised a company’s capability (competence), which is primarily driven by past financial and product performance. A few studies have also addressed company integrity (Jensen and Roy Citation2008, Park and Rogan Citation2019, Saxton Citation1997).

The management literature, however, takes a more expansive view on the extent to which a company is kind (emotion) – an additional type of reputation assessment that has not yet been addressed in the accounting literature. Many individuals, including employees, customers, investors, and other groups, link the reputation of a company to its emotional appeal, and companies’ public relations and marketing departments indeed work to increase their company’s emotional appeal. In addition to cognition and analytical processing, emotions are very powerful drivers of reputation assessments and subsequent stakeholder behaviour (Raithel and Schwaiger Citation2015); however, they are more difficult to measure than competence assessments are, which are primarily based on objectively measurable product and financial performance. By addressing the emotional domain of reputation, the set of research questions can be broadened. Do stock prices react more strongly to positive earnings announcements or management forecasts when investors have stronger emotions about a company? With negative information, are the effects weaker? Are the high price-to-earnings ratios of so-called ‘glamour’ stocks related to the emotional type of reputation? Finally, accounting research has not yet investigated the interdependencies between the competence, emotion, and integrity assessments. Do companies with higher competence assessments generally exhibit ‘better’ emotional assessments as well, and how do these assessments interact with regard to financial and nonfinancial performance?

3. Exploring normative expectations. Stakeholders’ normative expectations play an important role in management. This stream of the literature argues that social norms define reference points that also guide stakeholders’ reputation assessments in addition to benchmarking the company against competitors (Deephouse and Carter Citation2005). Despite financially outperforming competitors in its market, a company could still have a bad reputation if it fails to meet important normative expectations about how it should behave. These normative expectations can, for instance, explain the phenomenon in which market leaders have the stigma of being ‘vices’ because stakeholders regard this company as a prominent spearhead of a ‘sin industry’ such as the alcohol, tobacco, gambling, or weapons industries (Hong and Kacperczyk Citation2009). Accounting research may elaborate on the normative expectations of different stakeholder groups at the company level and how normative expectations moderate the effects of earnings management, financial restatements, or errors in auditing, e.g. concerning the cost of capital or concerning management turnover. Further, companies that fail to meet normative expectations may respond with changes to their corporate governance, including the quality of their financial and ESG disclosure.

4. Applying a multi-stakeholder lens. A fourth remark refers to a research gap which applies to both accounting and management literature. It is important to note that there is no single corporate reputation, but many. There are different stakeholders (Chun Citation2005, Walker Citation2010, Chakravarthy et al. Citation2014) with different information levels on corporate actions and outcomes, employing different types of assessments (emotion, competence, integrity) to different attributes of assessments (financial, nonfinancial). Even the same stakeholder may attach different reputations to a company (Chun Citation2005). Future research, in both accounting and management, could explore the question of how stakeholders trade off good and bad assessments to form an overall evaluation of a company, and how companies effectively try to ‘repair’ an unfavourable type and/or attribute of assessment.

7. Concluding remarks

The reader should be aware that we derived our suggestions from a literature review of specific journals, namely top-tier accounting and management journals, since we consider them to have large impact. Nonetheless, mainstream journals might be subject to biases towards specific methodological or conceptual paradigms (Walker Citation2010). We tried in part to address potential biases by including papers from Accounting, Organizations and Society, since this journal is known to allow for methodological and conceptual approaches that differ to those usually found in the other three top-tier accounting journals. Still, we ignored articles in less well-known journals. We also largely excluded papers outside the fields of accounting or management and organisation, since our focus was on the comparison of these two domains.

It could also be objected that a review of 173 papers is insufficient. However, we believe that the focus on well-cited articles published in top-tier journals over a span of 40 years could represent the research field relatively well (Walker Citation2010). In addition, to the best of our knowledge, we are the first authors to review the accounting literature and compare it with the management literature. Note also that many reviews base their study on an even smaller set of papers (Barnett et al. Citation2006: n = 49, Walker Citation2010: n = 54, Lange et al. Citation2011: n = 43, Ravasi et al. Citation2018: n = 77). An apparent way to address these two shortcomings is to extend the review to a larger list of publication outlets. Future research may also further develop the conceptual framework and better incorporate the dynamic nature of reputation and/or psychological or cultural biases (Ravasi et al. Citation2018).

We hope that our review stimulates further exploration of the domain of reputation research and encourages scholars to further improve their conceptual and methodological approaches.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (827.2 KB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Jonathan Bundy, Grahame Dowling, Maik Lachmann, two anonymous reviewers and the editors for providing valuable comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2022.2149458.

Notes

1 The journal selection is based on harzing.com which collates nine different journal rankings. The four accounting journals have the highest number of top positions in the rankings surveyed by harzing.com (TAR: 7, JAE: 7, JAR: 6, AOS: 5).

2 ASQ, AMJ, and SMJ have each nine top positions in the nine journal rankings collated by harzing.com. Academy of Management Review (also nine top positions) has been excluded because this outlet does not publish empirical research.

3 There is also a body of reputation literature in economics which the accounting literature (implicitly) refers to. This paper examines the management literature, because first, there is a long tradition of reputation research in this field, and second, there is a variety of reputation definitions and measurements in the management domain, which facilitates the development of a synthesized conceptualization of reputation.

4 Bushman and Wittenberg-Moerman (Citation2012) define the reputation of a lead bank by its average market share of the syndicated loan market, but this is a measurement of reputation rather than a definition.

5 See, for instance, King (Citation1996), Chen et al. (Citation2008), Williams (Citation1996), Graham et al. (Citation2014), Simnett et al. (Citation2009), and Lim and Tan (Citation2008).

6 Demski and Sappington (Citation1993) do not define reputation explicitly, but model it as a supplier’s updated assessment of a buyer’s honesty based on the buyer’s report.

7 To give credit to the original authors of the definition/measurement employed and to show the links between different studies, the references mention the original sources, even if they are not published in one of the reviewed accounting or management journals. Tables A1 to A4 in the Web Appendix link the original source with the papers reviewed.

8 For readability, the references include only selected papers.